Introduction

Research has examined patients’ experience of primary care from childhood into adulthood and has incorporated an exploration of the healthcare needs and priorities of younger patients, revealing a range of issues identified as important. These include issues relating to the accessibility and availability of health services (Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Bate, George, Shackley and Hall2006; Cheraghi-Sohi et al., Reference Cheraghi-Sohi, Hole, Mead, McDonald, Whalley, Bower and Roland2008; Gerard et al., Reference Gerard, Salisbury, Street, Pope and Baxter2008), continuity of care (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Freeman, Boulton, Windridge, Tarrant, Low, Turner, Hutton and Bryan2006; Guthrie and Wyke, Reference Guthrie and Wyke2006; Salisbury et al., Reference Salisbury, Sampson, Ridd and Montgomery2009), interpersonal aspects of care (Wensing et al., Reference Wensing, Vedsted, Kersnik, Peersman, Klingenberg, Hearnshaw, Hjortdahl, Paulus, Kunzi, Mendive and Grol2002; Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, Cox, Britten and Dundar2004; Coulter, Reference Coulter2005), equity of access (Crawford et al., Reference Crawford, Rutter, Manley, Weaver, Bhui, Fulop and Tyrer2002; Magee et al., Reference Magee, Davis and Coulter2003), and the ability of and opportunity for young adults to be involved in treatment decisions (Coulter and Cleary, Reference Coulter and Cleary2001). Although research has explored the views of children, adolescents, and adults about access to primary care, there is little research specifically focusing on young adults (aged 18–25 years), as the views expressed by this group are usually subsumed into either the adolescent or adult literature.

Healthcare needs and experiences identified in both the adolescent and adult literature may be less relevant to young adults. Between the ages of 18 and 25 years, young adults are refining their attitudes, exploring their life roles and opportunities, and increasingly assuming personal responsibility for their health care (Dovey-Pearce et al., Reference Dovey-Pearce, Hurrell, May, Walker and Doherty2005). The level of responsibility is dependent on their health status – for example, chronic illness from childhood for which they are now expected to assume responsibility (Dovey-Pearce et al., Reference Dovey-Pearce, Hurrell, May, Walker and Doherty2005), exploration of risky health behaviours (Viner and Barker, Reference Viner and Barker2005), and experience of interacting with the healthcare system. Their level of interaction with the healthcare system can also be affected by their social transitions. Leaving the family home, going to college/university, or starting employment can have an impact on the young adults’ use of and interaction with the healthcare system. For young adults who have been under the care of the same GP since childhood, this continuity of care may not be possible if they commence university or employment elsewhere.

Despite extensive research into the healthcare needs and experiences of National Health Service (NHS) patients (Mead et al., Reference Mead, Bower and Roland2008; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Smith, Nissen, Bower, Elliott and Roland2009; Department of Health, 2009), research specifically focusing on the needs, expectations, and experiences of young adults (18–25 years) as users of primary care service in the United Kingdom is limited. The focus of this paper is on the young adults’ experiences of primary care within the United Kingdom. Although there are countries comparable with the United Kingdom in terms of having universal healthcare systems, these systems operate differently to the universally available, publicly funded system characterising the UK NHS. For example, Australia subsidises 75% of the cost of GP services through a governmental scheme called Medicare, and Canada's primary care services are mostly delivered by private providers (National Audit Office, 2003). Differences in the way health care is delivered in other countries could impact how young adults use and experience services, including what barriers they may face.

This review aimed to identify the views and priorities of young adults regarding primary healthcare provision, and to identify related topics, which would benefit from further research.

Method

Academic literature

A combination of keywords was used to search Web of Science (Ovid; 2000 to March 2011), PsycINFO (Ovid; 2000 to March 2011), and PubMed (Ovid; 2000 to March 2011). Searches were limited to papers published after publication of the NHS plan (2000). The reasons behind specifically focusing on any literature published from 2000 onwards are to reflect any changes to services following the publication of the NHS plan. Literature was also identified by citation tracking using reference lists from papers and from the PubMed database. Keywords identified within three main search headings were used (Table 1). The search headings included: (a) ‘Young adult’, (b) ‘Access, satisfaction or needs’, and (c) ‘Primary care or health care’. Papers that incorporated a combination of some of the search terms were considered for inclusion in the review. Database searches were run in May 2010, July 2010, and March 2011. Results were downloaded into Reference Manager® (v11) bibliographic software. Duplicates were deleted and papers that omitted a breakdown of participants’ ages were excluded.

Table 1 Keywords used within the search

The definition of a young adult varies across agencies, academic schools of thought, and cultural groups (Devitt et al., Reference Devitt, Knighton and Lowe2009). Many services mark 18 as the age where children's services end and adult services commence (Devitt et al., Reference Devitt, Knighton and Lowe2009), but the United Nations defines 16–24-year-olds as ‘youth’ or ‘young people’ (Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2007). The criminal justice system has recognised that the needs of 18–21-year-olds may differ from older adults, and has introduced Young Offenders Institutions (Devitt et al., Reference Devitt, Knighton and Lowe2009). For this review, we have defined young adults as 18–25-year-olds.

Titles and abstracts of papers were screened for relevance against predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria and full text articles obtained where possible. Articles reporting (i) the experience of young adults in accessing health care, (ii) matters identified as important by young adults when using the healthcare system, and (iii) the range of healthcare needs identified by young adults were included. Articles failing to provide all details, or those not published in English, were excluded.

Grey literature

Searches were conducted on the websites of relevant organisations (eg, Department of Health) using the search terms mentioned above. Searches were run from March to July 2010 and in March 2011. Publications about health services delivered to young adults and reporting patient experiences were considered for the review.

Owing to the variability in the methodologies adopted across the research reviewed, a thematic analytical approach was used to extract themes. Common themes emerging across different papers were identified by authors as signifying an important aspect of care to young adults. These themes were then organised into overarching global themes.

Results

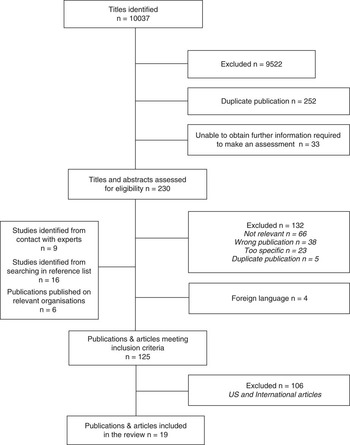

Database searches identified 10 034 potentially relevant papers (‘hits’). Preliminary screening excluded 9807 papers. The remaining 227 papers were obtained and examined. A total of 105 papers were excluded because they appeared to be irrelevant, reported findings not relevant to our target population, were disease specific, or were in a language other than English. Database searches yielded 122 papers from which research conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 17) was included. The grey literature searches identified two reports that met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Progress of search for relevant research

Important aspects of care for young adult service users

The research papers reviewed identified five key themes for young adult service users. Qualitative papers (Dixon-Woods et al., Reference Dixon-Woods, Stokes, Young, Phelps, Windridge and Shukla2001; Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Liabo, Roberts and Barker2004; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Klein, Noyce, Sesselberg and Cantrill2005; Biddle et al., Reference Biddle, Donovan, Gunnell and Sharp2006; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Churchill, Crawford, Brown, Mullany, Macfarlane and McPherson2008) focused on young people's views of healthcare provision, their experiences, and needs as service users. The cross-sectional paper (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Boulton, Windridge, Tarrant, Bankart and Freeman2007) examined the barriers to interpersonal continuity for patients across different age groups. The review papers (Jackson, Reference Jackson2004; McPherson, Reference McPherson2005; Freake et al., Reference Freake, Barley and Kent2007; Tylee et al., Reference Tylee, Haller, Graham, Churchill and Sanci2007; Gulliver et al., Reference Gulliver, Griffiths and Christensen2010) summarised the experiences of young people regarding primary care services, and suggested how healthcare services could best be tailored to those needs. Papers using a survey methodology (Wilson and Williams, Reference Wilson and Williams2000; Meltzer et al., Reference Meltzer, Bebbington, Brugha, Farrell, Jenkins and Lewis2003; Jerome et al., Reference Jerome, Hicks and Herron-Marx2009) identified the healthcare needs and barriers experienced by young adults. Three papers provided an overview of current services tailored to young adults and experience of these (Rogstad et al., Reference Rogstad, Ahmed-Jushuf and Robinson2002; Rowlands and Moser, Reference Rowlands and Moser2002; Daniel, Reference Daniel2004). The reports (Department of Health, 2001; Opinion Leader Research, 2006) outlined the use and experience of primary care services by young adults and suggested strategies for improvement.

Access and availability

Access to primary health services is seen as an important component of care, and one that may be a potential barrier for this group (Tylee et al., Reference Tylee, Haller, Graham, Churchill and Sanci2007). This may be because of inconvenience, for example, the distance of the facility to the young adult's home, study or work, opening hours (McPherson, Reference McPherson2005), or lack of visibility of the service (Tylee et al., Reference Tylee, Haller, Graham, Churchill and Sanci2007).

GP consultation rates for young adults are consistently lower than those of adolescents and adults over the age of 60 years (Rowlands and Moser, Reference Rowlands and Moser2002). Attendance rates at A&E (accident and emergency) is reportedly higher for individuals aged 10–19 years (13.3%) and 20–29 years (16.2%) than for older age groups – for example, 12.2% among individuals aged 30–39 years (NHS Information Centre, 2012). Research also shows that young adults are over-represented amongst walk-in service users as a greater proportion of walk-in centre users are between the ages of 17 and 35 years (Salisbury and Munro, Reference Salisbury and Munro2002; Salisbury et al., Reference Salisbury, Manku-Scott, Moore, Chalder and Sharp2002).

In order to understand the access for this population, their perception of the available services, the services they access, and the accessibility of those services need to be clarified.

Young adults may first experience mental health problems during adolescence (Biddle et al., Reference Biddle, Donovan, Gunnell and Sharp2006). Qualitative research carried out with a sample of 23 16–24-year-olds showed that they have negative perceptions about the value of consulting GPs about mental distress, which may explain low rates of help-seeking behaviour (Biddle et al., Reference Biddle, Donovan, Gunnell and Sharp2006). The associated stigma with mental illness has created barriers in help-seeking behaviour (Gulliver et al., Reference Gulliver, Griffiths and Christensen2010). Research examining help-seeking behaviour for a neurotic disorder revealed that younger adults (under 35 years) were two to three times more likely to be embarrassed when seeking help as compared with older adults (Meltzer et al., Reference Meltzer, Bebbington, Brugha, Farrell, Jenkins and Lewis2003). Further research is needed to identify the mental health needs of young adults, and how to make services more accessible for this population.

A range of health issues are commonly experienced during young adulthood, including sexual health and chronic illnesses (Park et al., Reference Park, Mulye, Adams, Brindis and Irwin2006). Improving access to sexual health services was highlighted as a priority in the 2001 National Strategy (Department of Health, 2001), in response to the rising number of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unwanted pregnancies, and public ignorance about sexual health. Despite this focus on improving sexual health services, and although teenage pregnancy rates in the United Kingdom have dropped by 18% since 1998, the UK rates remain much higher compared with other European countries (Department for Education, 2009), with 16–24-year-olds living in and around deprived areas identified as the most vulnerable group (Jerome et al., Reference Jerome, Hicks and Herron-Marx2009). The rise in STIs (Daniel, Reference Daniel2004) has provoked concern about how sexual health services are used by young adults, and highlighted the need to provide effective access to high-quality services delivered in a suitable way.

The use of one or more of these sexual health services depends on the relationship between the young person and their GP (Jackson, Reference Jackson2004), the sense of privacy and confidentiality (Department of Health, 2001; Dixon-Woods et al., Reference Dixon-Woods, Stokes, Young, Phelps, Windridge and Shukla2001; Rogstad et al., Reference Rogstad, Ahmed-Jushuf and Robinson2002), the accessibility of services (Wilson and Williams, Reference Wilson and Williams2000; Department of Health, 2001), and the type of service being provided (Department of Health, 2001). Dixon-Woods et al. (Reference Dixon-Woods, Stokes, Young, Phelps, Windridge and Shukla2001) explored women's accounts (12 out of 16 quotes were from women aged 15–25 years) of choosing and using specialist services for sexual health. They indicated that women found out about these specialist services in three ways: lay referrals, ‘insider knowledge’, and referral from a health professional. Previous positive experience of using a specific service appeared to result in the reuse of the same service for a new health problem (Jackson, Reference Jackson2004). Negative experiences with GPs led some to choose other specialised services, for example, genitourinary medicine clinics. Further exploration of the young adults’ knowledge, utilisation, and experience of these services is required to gain more understanding of their needs.

Confidentiality

A recent literature review exploring the views of 12–19-year-olds about their interactions with health professionals identified a range of views about the importance of confidentiality for older adolescents (Freake et al., Reference Freake, Barley and Kent2007).

Local cultural factors can influence the level of significance attached to confidentiality. Religious beliefs may underpin sexual behaviours for some individuals and within ethnic groups (Fenton et al., Reference Fenton, Mercer, McManus, Erens, WEllings, Macdowall, Byron, Copas, Nanchahal, Field and Johnson2005; Ross and Fernández-Esquer, Reference Ross and Fernández-Esquer2005). In such settings, young adults may fear that confidentiality could be compromised when consulting a health professional regarding a sexual health problem (Park et al., Reference Park, Mulye, Adams, Brindis and Irwin2006). These observations strengthen the need for carefully constructed research to investigate the causal relationships in this matter.

Research into the use of the Internet as a source of health information and advice has shown that adolescents and young adults may use this as an alternative to visit their GP (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Klein, Noyce, Sesselberg and Cantrill2005). The use of technology appears to provide young adults with a sense of empowerment, and an opportunity to control the level of anonymity. One study has suggested that positive interaction with a health professional via the Internet may encourage young adults to arrange a face-to-face visit with their own GP (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Klein, Noyce, Sesselberg and Cantrill2005; Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Churchill, Crawford, Brown, Mullany, Macfarlane and McPherson2008). Further research exploring the role of interactive media in gaining the views and behaviours of young adults around healthcare services is needed.

Continuity of care

Young adults with a chronic illness, special needs, or who are ‘hard to reach’ (asylum seekers, those previously in care, or in contact with the criminal justice system) have stressed the importance of continuity of care during the transition to adult services (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Liabo, Roberts and Barker2004). A study examining the importance of interpersonal continuity (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Boulton, Windridge, Tarrant, Bankart and Freeman2007) found that working individuals and those not in work for any reason other than retirement, had more difficulty in securing informational and interpersonal continuity in comparison with retirees (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Boulton, Windridge, Tarrant, Bankart and Freeman2007). The study did not relate their findings to specific age ranges, leaving some uncertainty about how important continuity of care is to young adults.

Research examining continuity of care has generally focused on patients with chronic illnesses and on adults in general. It has shown that this is a complex area affected by a variety of factors. Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Freeman, Boulton, Windridge, Tarrant, Low, Turner, Hutton and Bryan2006) have suggested that as patients get older, they prioritise continuity of care, as do patients in poorer health or with a chronic illness, whereas younger and healthier patients prioritise quick access to care. The authors recognised that the younger participants’ response rates were significantly lower than those of other age groups. Future research is needed to explore the importance of different aspects of continuity of care for young adults in general.

Communication and information sharing

Research has shown that communication between doctors and young patients has been problematic, creating barriers for individuals seeking face-to-face advice (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Churchill, Crawford, Brown, Mullany, Macfarlane and McPherson2008). Young people prefer communication to be a two-way process (Freake et al., Reference Freake, Barley and Kent2007), in that they want their doctors to listen to them and to respect their level of knowledge of their own bodies as well as their feelings. The consultation style adopted by the health professional is also important. Dovey-Pearce et al. (Reference Dovey-Pearce, Hurrell, May, Walker and Doherty2005) found that young adults with diabetes reported feeling rushed during consultations, and that health professionals needed to ensure that young people were fully engaged with their consultation. Health professionals should also ensure that young adults are treated with respect and autonomy. The way doctors and other health professionals communicate with young adults has the potential to affect future use of services, as ineffective communication is seen as a potential barrier for young adults (McPherson, Reference McPherson2005).

The way information on health or available services is presented to young adults is important. Feedback from a Department of Health consultation exercise revealed that young people wanted information presented in a way that addresses their age group, uses appropriate media, and relates to aspects of care they find important (Opinion Leader Research, 2006). Although access and support is important for all patients, age-appropriate media may be a positive way forward when engaging young adults in particular.

Behaviour and attitude towards young adults

Qualitative research exploring the views of young people on their health care in general reported doctors as being unfriendly, insensitive, and sceptical of their presenting problems (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Liabo, Roberts and Barker2004). Further qualitative research with young adults with diabetes reported similar concerns and experiences with doctors and nurses (Dovey-Pearce et al., Reference Dovey-Pearce, Hurrell, May, Walker and Doherty2005). In order for their needs to be met by health professionals, young people expressed the need for civility (Dovey-Pearce et al., Reference Dovey-Pearce, Hurrell, May, Walker and Doherty2005), respect (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Liabo, Roberts and Barker2004), kindness, sympathy, and understanding (Wilson and Williams, Reference Wilson and Williams2000). It is apparent from previous research that problems around the behaviour and attitude of health professionals towards young adults can act as barriers to future use. Further research is needed to explore the full impact of health professionals’ behaviours and attitudes on young adults.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The aim of this research was to identify and synthesise evidence from publications that examined the needs, access to care, and experiences of primary care by young adults (18–25 years). Our research has identified an overlap in certain aspects that are important to patients of all ages; some are of more importance to a younger population (confidentiality), whereas others are more important to older people (continuity of care).

Although some aspects of care are important to all patients, research focusing on 18–25-year-olds is underdeveloped and spans literature reporting the experience of adolescents, young people, and adults (aged 18 years and above). Aspects of care relevant to this age group were extracted from the literature. Findings from this review suggest that young adults may have distinct views from those expressed by adolescents or older adults.

The accessibility of specific services is important to young adults, especially in terms of their sexual health needs. The behaviour and attitude exhibited by GPs towards young adult patients, as well as young adults concerns in respect of the confidentiality of their consultations, has been shown to influence their use of GP surgeries (Wilson and Williams, Reference Wilson and Williams2000; Dixon-Woods et al., Reference Dixon-Woods, Stokes, Young, Phelps, Windridge and Shukla2001; Park et al., Reference Park, Mulye, Adams, Brindis and Irwin2006). On the basis of the literature reviewed here, it appears that negative experiences with GPs and related accessibility issues could explain higher rates of attendance at A&E and walk-in centres for young adults, and the lower rates of attendance at GP surgeries.

Although the term ‘young people’ is used frequently, there is no consistent definition of the precise age range it refers to. The definitions in the studies included in this review covered a range of ages, which created difficulties when making comparisons across studies, and drawing conclusions about what mattered to young adults when accessing health care.

Strengths and limitations of the study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time UK literature addressing the primary healthcare needs and priorities of young adults has been brought together. There is limited research focusing on this topic, thus our review includes studies reporting a mixture of methodologies and a range of research questions. The evidence varies in quality, and we have provided only a synthesis of the relevant literature rather than a detailed systematic review or meta-ethnography.

Although research suggests that there are differences in the use and experience of primary care across different ethnic groups (Saxena et al., Reference Saxena, Eliahoo and Majeed2002), there was limited UK research specifically focusing on ethnic minorities in our age group. Research examining patient experiences has either focused on different age groups (eg, 16–30/4; Mead and Roland, Reference Mead and Roland2009; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Murphy, Webb, Hawton, Bergen, Waters and Kapur2010b), or on a specific aspect of health care (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Bebbington, McManus, Meltzer, Stewart, Farrell, King, Jenkins and Livingston2010a; Riha et al., Reference Riha, Mercer, Soldan, French and Macintosh2011). Further research is needed to investigate whether the use, needs, and experience of primary health care differ across different socioeconomic and ethnic groups for young adults.

The inclusion criteria highlight research conducted from 2000 onwards, acknowledging any changes made to services proposed by the NHS plan (2000). The focus was on literature relating to the UK healthcare system, as differences in health systems across the world could influence the needs of young adults (eg, privatised healthcare systems).

Implications for future research

Research has tended to focus on the health needs of ‘children’, ‘adolescents’, and ‘adults’; however, little specific attention has been given to the general health needs of young adults (18–25 years) in the United Kingdom. We suggest that research is needed to examine the needs and perceptions of primary health care for this population as well as the frequency with which they access GP services. If services are responsive to their needs, then problems that may contribute to escalating healthcare costs could be avoided. These factors will determine whether or not young adults access specialised services, for example, sexual health clinics, and whether they view their GP surgery as their first choice. It is important to investigate perceptions of primary care and understanding of the services available, and to examine the causes of the young adults’ perceptions. Early experiences may have an impact on whether or not young adults choose to access their GP surgery, before seeking help from another service.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by funding from the Department of Health.