Introduction

More than a decade ago, Felin and Foss (Reference Felin and Foss2005) proclaimed their frustration with capabilities research for failing to attribute the individuals supporting such capabilities. This lack of focus on the individual represents a broader problem encompassing strategy research (Powell, Reference Powell2014). The antidote, they argued, is microfoundations research that seeks to understand individual-level factors underpinning organisational capabilities.

Although important advances are being made to understand microfoundations, the role of individuals' emotions received little attention in either capabilities research or strategy research more generally (Hodgkinson & Healey, Reference Hodgkinson and Healey2011; Huy, Reference Huy2012). This lack of attention is surprising, since organisational life gives rise to a range of emotions. Furthermore, wider organisation studies and psychology literatures have long recognised the impact of emotions on individuals' decisions and actions. Addressing this gap promises new insights into understanding the role emotions play in organisational adaptation through capability development.

This paper therefore responds to calls for more emotions research within strategy (Huy, Reference Huy2012) and capabilities studies (MacLean, MacIntosh, & Seidl, Reference MacLean, MacIntosh and Seidl2015), by utilising in-depth empirical research into how emotions of key strategists enable or hinder capability development. We begin by drawing on extant literature to theorise the impact of emotions on capability development. The research approach is then described before moving onto the findings which demonstrate that key strategists' emotions can have multi-faceted and crucial effects on capability development. The paper concludes with a discussion on theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical background

Microfoundations of capability development

Heterogeneity in firm performance has been recognised since the seminal paper of Nelson (Reference Nelson1991). Contemporary research on this issue underscores the importance of dynamic capabilities, which enable organisational adaptation through renewal, redeployment, recombination or reconfiguration of firms' resources and capabilities (Helfat et al., Reference Helfat, Finkelstein, Mitchell, Peteraf, Singh, Teece and Winter2007; Teece, Reference Teece2007). Such capabilities have a change-oriented purpose, leading to repeatable change that is strategically and economically important for the organisation (Helfat et al., Reference Helfat, Finkelstein, Mitchell, Peteraf, Singh, Teece and Winter2007; Helfat & Winter, Reference Helfat and Winter2011; Teece, Reference Teece2007). They allow firms to sense and seize opportunities quickly and proficiently (Teece, Reference Teece2007) when enacted to achieve congruence with the changing environmental conditions internally and externally (Kor & Mesko, Reference Kor and Mesko2013). The degree to which these dynamic capabilities are routine in nature has engendered debate among scholars, with Winter (Reference Winter2003) advocating a highly routine conceptualisation and Teece (Reference Teece2012) arguing that such capabilities have both routine and non-routine elements. In this paper, our focus is the key strategists and their agency in developing and enacting capabilities. By prioritising the enactment of capabilities (over their mere possession) we align with Teece (Reference Teece2012) in this debate, since enacted routines invariably involve some non-routine behaviours (Feldman & Pentland, Reference Feldman and Pentland2003). Such a focus helps understand the idiosyncrasy of capabilities as argued by scholars such as Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997) and Helfat et al., (Reference Helfat, Finkelstein, Mitchell, Peteraf, Singh, Teece and Winter2007), rather than focusing on dynamic capabilities as best practices as proposed by Eisenhardt and Martin (Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000).

Dynamic capabilities were originally conceptualised as an aggregate and collective phenomenon operating at the organisational level (e.g., Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000; Helfat et al., Reference Helfat, Finkelstein, Mitchell, Peteraf, Singh, Teece and Winter2007; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997). However, this conceptualisation left it unclear how the knowledge, competencies, actions, and decisions of individuals underpinning a capability were aggregated up to the organisational level (Barney & Felin, Reference Barney and Felin2013). In response to this, over the last decade, dynamic capabilities research has shifted towards disaggregating these organisational level phenomena to understand their lower-level (micro)foundations (Felin, Foss, Heimeriks, & Madsen, Reference Felin, Foss, Heimeriks and Madsen2012). Felin et al. (Reference Felin, Foss, Heimeriks and Madsen2012: 1352) summarise the focus of microfoundations research as considering how ‘lower-level entities, such as individuals or processes in organisations, and their interactions’ explain collective phenomena, such as dynamic capabilities. This change in focus is crucial to understand how specific actors and their agency (Barney & Felin, Reference Barney and Felin2013) influence dynamic capabilities and which individual characteristics and behaviours make the development and enactment of these capabilities possible (Foss, Reference Foss2011).

Microfoundations research has so far revealed that management cognition can be an important source of capability development (Eggers & Kaplan, Reference Eggers and Kaplan2009; Gavetti, Reference Gavetti2005). The implication is that firms may respond to the same exogenous change differently due to subjectivism in managerial perceptions, expectations, preferences (Kor, Mahoney, & Michael, Reference Kor, Mahoney and Michael2007) or due to differences in managerial alertness, responsiveness and learning (Cohen & Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990).

Eggers and Kaplan (Reference Eggers and Kaplan2013), in their model of capability development, integrate key strategists' understanding and interpretations of firm's capabilities, of the environment that necessitates the development of these capabilities, and of the potential value of resulting capabilities after this process of development. This then shapes how they will deploy firm's resources for the development and maintenance of capabilities. Martin and Bachrach (Reference Martin and Bachrach2018) show how key strategists' cognition interacts with social and relational factors. In an attempt to aggregate microfoundational managerial dynamic capabilities with macro-level dynamic capabilities, they show how managers combine their knowledge structures, mental processes and cognitive capacities (i.e., managerial cognition) with the perceptions of others in their networks of formal and informal relationships (i.e., social capital) to generate a set of activities and routines to collectively sense and seize opportunities (i.e., networking capability) to reconfigure their individual responses.

Even though such research on cognitive underpinnings of capability development is advancing, its emotional foundations remain largely unexplored (Hodgkinson & Healey, Reference Hodgkinson and Healey2011). This is perhaps due to the economic foundations of the concept of capabilities in the resource-based view, which has marginalised psychological and sociological explanations (Foss & Hallberg, Reference Foss and Hallberg2017). Given the well-established link between cognition and emotion (e.g., Elfenbein, Reference Elfenbein2007; Russell, Reference Russell2003), this is an important gap limiting scholarly understanding of heterogeneity in organisations' strategic responses to environmental conditions. To address this gap, our research focuses on how key strategists' emotionsFootnote 1 impact development of capabilities to support organisational adaptation and change.

Emotions and capability development

We know that cognition is a well-established microfoundation of capability development and that emotions influence cognition. As such, we now consider extant research into the effect that emotions have on cognition, by reviewing the literature on emotions-driven cognition, to start developing an understanding of the potential links between emotions and capability development.

Elfenbein (Reference Elfenbein2007) argued that strong emotions occupy cognitive capacity, and consequently distort individuals' evaluations of consequences of decisions. Even strong positive emotions can cause distortion because these individuals become less critical and dismiss certain signals to protect their positive moods and avoid unpleasant thoughts (George & Zhou, Reference George and Zhou2002). The affect-as-information perspective (Schwarz, Reference Schwarz, Van Lange, Kruglanski and Higgins2011) would support these views, arguing that emotions underlie the meaning structures of individuals, thus shaping how real-life events are perceived and evaluated. For example, individuals experiencing anxiety are likely to interpret events as signalling uncertainty and lack of control (Raghunathan & Pham, Reference Raghunathan and Pham1999), whereas positive emotions lead people to more positive evaluative judgements (Zelenski & Larsen, Reference Zelenski and Larsen2002) shaping decision-making on which opportunities will be exploited (Welpe, Spörrle, Grichnik, Michl, & Audretsch, Reference Welpe, Spörrle, Grichnik, Michl and Audretsch2012). Negative emotions experienced by top managers might also limit the scope of options and information being considered (Hutzschenreuter & Kleindienst, Reference Hutzschenreuter and Kleindienst2013). By distorting cognitive processing, emotions may affect strategists' consideration of signals in the external environment, consideration of opportunities and their decision-making on which opportunities to exploit. These factors are all components of the sensing and seizing of opportunities that are central to capability development (Teece, Reference Teece2007).

The influence of emotions is not necessarily a distortive process interrupting cognition, though. Other scholars suggested that emotions can serve cognition by benefitting cognitive processing of the relevance of an affective event to one's goal as well as its antecedents and future prospects (Russell, Reference Russell2003). Emotion directs attention to solving problems and to information relevant to that end and provides the motivation to pursue those solutions (Loewenstein & Lerner, Reference Loewenstein, Lerner, Davidson, Scherer and Goldsmith2003). These findings can be explained through discrepancy theory. Discrepancy theory suggests that, for example, when a person compares the perceived reality with their prior expectations and finds a negative mismatch, this arouses dissatisfaction with the current state (Higgins, Reference Higgins1987). This negative emotion, in turn, stimulates learning and change (Hochschild, Reference Hochschild1983). In an organisational setting this may trigger and influence capability development by encouraging opportunity recognition (Baron, Reference Baron2008), issue recognition (Hutzschenreuter & Kleindienst, Reference Hutzschenreuter and Kleindienst2013), idea generation (Hayton & Cholakova, Reference Hayton and Cholakova2012) and opportunity exploitation (Welpe et al., Reference Welpe, Spörrle, Grichnik, Michl and Audretsch2012).

These shed light on the possible links between emotions and capability development, however, only through inferences on how emotions affect cognition. As such, these studies give little direct insight into the ways in which emotions influence capability development (i.e., as a barrier or an enabler). Furthermore, the evidence above is inconclusive, with emotions being found to both interrupt and distort (e.g., Forgas, Reference Forgas, Davidson, Scherer and Goldsmith2003; George & Zhou, Reference George and Zhou2002) or stimulate and benefit (e.g., Higgins, Reference Higgins1987; Russell, Reference Russell2003) cognition. This highlights the complexities associated with emotions, suggesting that the impact emotions have are neither linear nor straightforward. Instead of extrapolating conclusions from another stream of research, studies into the link between emotions and capability development to further understand the associated nuances and complexities are needed. Illuminating this complexity calls for in-depth qualitative research.

Extant research that more specifically focuses on the links between emotions and capabilities tends to focus on the role of emotional intelligence and how managers can manage their own and others' emotions to facilitate organisational development. For example, studies show how emotionally intelligent managers show an ability to adapt to changing demands and an increased willingness to consider strategic change and organisational development to address these (George, Reference George2000; Sinclair, Ashkanasy, & Chattopadhyay, Reference Sinclair, Ashkanasy and Chattopadhyay2010). These managers are found to be better at initiating capability development by using more expansive modes of thinking (Sinclair, Ashkanasy, & Chattopadhyay, Reference Sinclair, Ashkanasy and Chattopadhyay2010) and better at driving employee adaptation once capability development initiatives are introduced. They can perceive and manage emotions of others and assist others to respond positively to new initiatives (Scott-Ladd & Chan, Reference Scott-Ladd and Chan2004), induce others to re-evaluate their current negative feelings, regulate cynicism (Ferres & Connell, Reference Ferres and Connell2004), generate excitement, enthusiasm and optimism (George, Reference George2000). They can mobilise concrete actions and resources to support new routines underpinning new capabilities (Huy, Reference Huy1999).

Although these studies are insightful, the focus on emotional intelligence and emotion management largely ignores the effect of key strategists' naturally occurring emotions on capability development – instead looking into how those emotions are managed once they emerge. Furthermore, these studies generally do not consider the full range of emotions or the level of intensity at which these emotions are experienced, which leads to only partial insights. Since organisations are hotbeds of emotions experienced at different intensities, it is crucial to understand how the full spectrum of emotions can impact capability development which is important to organisational performance. As such, we answer Sinclair, Ashkanasy, and Chattopadhyay's (Reference Sinclair, Ashkanasy and Chattopadhyay2010) call for more research acknowledging the independent effects of positive and negative emotions and the intensity at which they are experienced on decision-making. We do so by focusing on decision-making related to capability development.

Specifically, we investigate how key strategists' emotions enable and/or hinder capability development. This focus is important given the critical role these individuals play in capability development initiatives (Adner & Helfat, Reference Adner and Helfat2003) and in actions triggering variation, selection and retention of capabilities (O'Shannassy, Reference O'Shannassy2014). We address this question in the context of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) since the cognitive and behavioural outcomes of key strategists' emotions have especially pronounced effects on organisational development of SMEs. The SME context is important for two reasons. First, as noted by Galvin, Rice, and Liao (Reference Galvin, Rice and Liao2014), SMEs are unlikely to have any significant resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable to set them apart from other competitors, hence they are more likely to engage in a continual re-evaluation of capabilities in both their internal operations and market offerings. This makes SMEs an appropriate context to capture as many capability development initiatives as possible in the duration of the research. Second, the capability development initiatives in SMEs are likely to be influenced and controlled by the owner-managers and the management team (Kelliher & Reinl, Reference Kelliher and Reinl2009) making them an appropriate context to study the role of key strategists' emotions.

Methodology

This paper draws on data collected from broader studies of capability development in the United Kingdom and Turkey. As the two authors shared observations and insights, the data revealed that the emotions of the key strategists interviewed had a noticeable impact on their organisations' capability configuration and the journey leading to that. It was this grounded approach to theorising (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006) that set the focus for further data analysis and theory development to capabilities from the lens of emotions.

For this paper, we isolated five organisations from the broader studies. The reason for using a sub-set of data collected is to extract and elaborate on intense, data-rich descriptions while maintaining enough diversity to allow for theoretical elaborations (De Vaus, Reference De Vaus2001) and a replication logic (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007). Information about the organisations covered in this paper is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Company information

a At the time of data collection.

The organisations operate in a variety of industries and range from micro- to medium-sized enterprises. The diverse sample used enabled findings to be relevant to a broader range of organisations (Hendry, Kiel, & Nicholson, Reference Hendry, Kiel and Nicholson2010) increasing the transferability of findings – a key criterion for quality research (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). Furthermore, since we took an exploratory and inductive approach, it was important to avoid restricting the range of insights that could emerge by narrowing the sample. A varied sample could enable broadly informed insights that could form the basis for future deductive research in more specific settings (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007), again increasing the scope for transferability (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985).

Data collection

Data were collected using a range of qualitative methods, with interviews being the main source. In total, 21 interviews were conducted with nine owner-managers, and other family and non-family members in the management teams. All were key strategists in their organisations.

Interviews focused, among other things, on the development and renewal of the organisations and the opportunities and challenges faced. Insights into emotions emerged naturally and subtly during the interviews and were driven by the interviewee in the first instance. This inductive approach meant that salient emotions surfaced from the data. This was important as it meant we did not limit the study to a set of pre-identified emotions to be researched and it helped to gain a fuller and richer picture of the complex interactions between a range of different emotions and capability development.

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed and, where required, personal notes were made by the interviewer, including informal observations and discussions not recorded as part of the interviews. In addition, some informal interviews with employees and other managers were also conducted, often taking place between formal interviews. Observations of daily interactions were also undertaken through qualitative shadowing. Additional data were also collected via follow-up emails and short telephone conversations. In total, over 24 interview hours and 34 hours of observation data were collected. An overview of the data collection undertaken is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of data collected through interviews

Data analysis

Data analysis combined established methodologies for analysing qualitative data (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1984) consisting of two opposing strands of activity – fragmenting and connecting. The process of fragmenting involved coding pieces out of the interview data, as explained in Phase 1 below. The process of connecting involved capturing commonalities and differences to identify and relate variation in emotions and its implications through the constant comparative method (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss1990) and associative analysis (Ritchie, Spencer, & O'Connor, Reference Ritchie, Spencer, O'Connor, Ritchie and Lewis2003). This is detailed in Phase 2 below.

Phase 1. Extracting capability development initiatives and coding emotions

Data analysis began by extracting capability development initiatives from the interviews. These were interviewees' accounts, or rather discursive descriptions, which explain and interpret capability development in areas such as product and service offerings, technology, marketing and human resources.

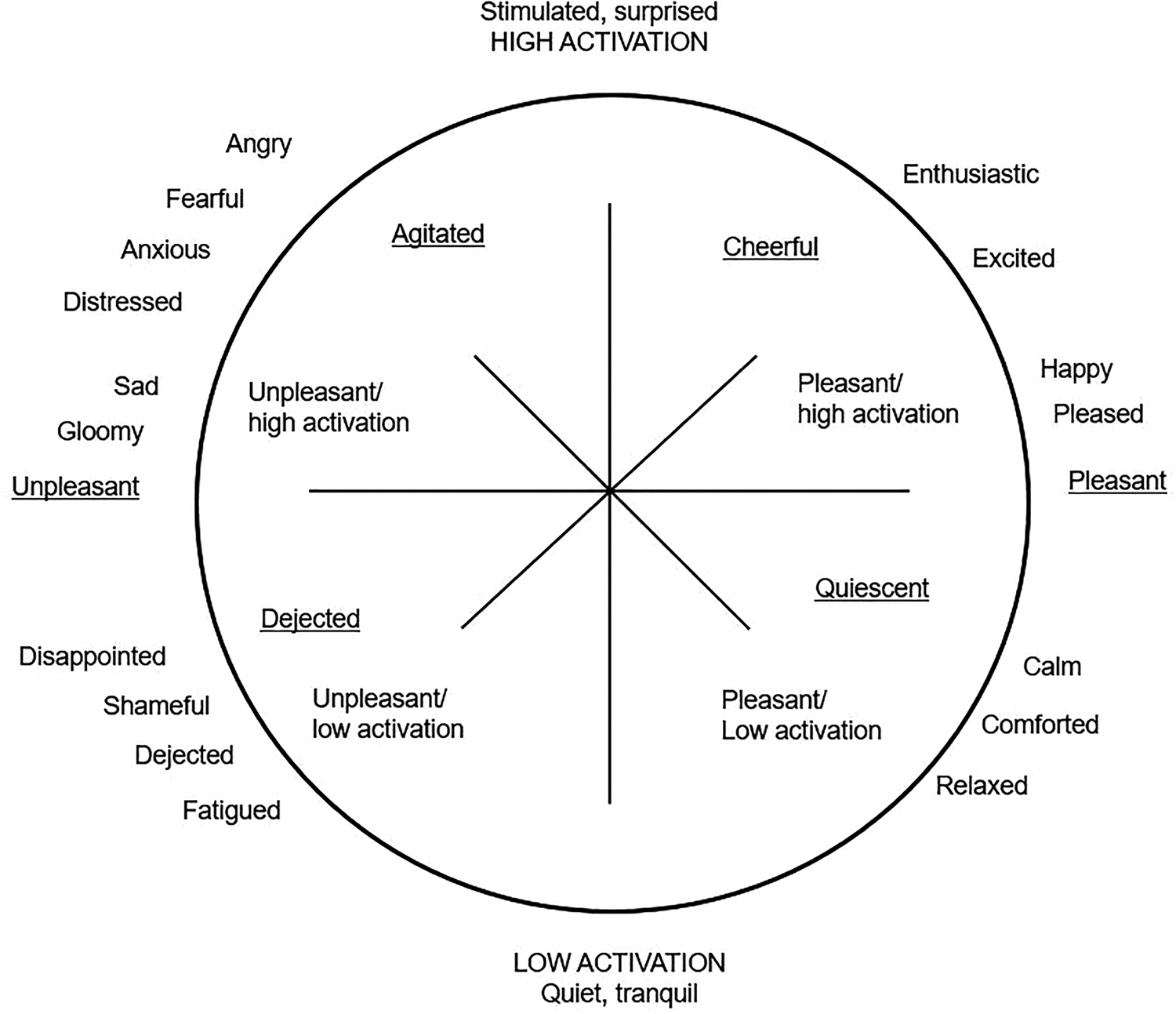

Emotions were coded using the circumplex model (Russell & Feldman-Barrett, Reference Russell and Feldman-Barrett1999; Russell, Reference Russell2003), which has been highly influential in studying organisational settings (e.g., Huy, Reference Huy2002; Liu & Maitlis, Reference Liu and Maitlis2014). The model (Figure 1) arranges emotions in a circumplex sharing two independent dimensions (Russell & Feldman-Barrett, Reference Russell and Feldman-Barrett1999). The first dimension reflects the hedonic valence (pleasantness–unpleasantness), ranging from positive emotions, such as happy and pleased, to negative emotions, such as sad and depressed. The second dimension refers to the intensity of arousal caused (high activation–low activation), which suggests the extent of mobilisation and action readiness.

Fig. 1. Circumplex model (Larsen and Diner, 1992 in Huy, Reference Huy2002).

The two authors coded the transcribed interview data according to the four categories in the circumplex model. To ensure consistency, the emotion words provided by Scherer (Reference Scherer2005) were used to label specific emotions within each of the four categories. Following similar studies using interview data (e.g., Heaphy, Reference Heaphy2017; Maitlis & Ozcelik, Reference Maitlis and Ozcelik2004; O'Neill & Rothbard, Reference O'Neill and Rothbard2017), emotions were identified in keywords and expressions that were highly emotive. Inspiration was taken from Baldwin and Bengtsson (Reference Baldwin and Bengtsson2004) who highlight the importance of language in personal self-reports and associated discursive representations as the bearer of emotive evaluations about a particular phenomenon.

Some researchers urge caution in using emotion words to study emotion, acknowledging that emotional tone can also be expressed through metaphors and intonations and other means not directly related to emotion words (Pennebaker, Fracis, & Booth, Reference Pennebaker, Fracis and Booth2001). The coding for this study, therefore, was not only limited to identifying keywords that would communicate explicitly the interviewee's emotions – for example, identifying irritation, through words such as, ‘upset’, ‘dislike’, ‘frustrated’, ‘dismayed’ and ‘overwhelmed’. Instead, a more nuanced approach was taken by looking at how words were used in context, even if keywords were not present. Therefore, emotion was coded through paying attention to the linguistic environment holistically (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2004) through the tone of expression and what the interviewee was saying in the entirety. For example, although no word in the following sentence communicates irritation, a review of the tone and content of the comment led to it being coded as irritation:

‘…but no one asks, “Why are we using 25,000, can we decrease our tip consumption to 12,000 units?” There is no questioning because there is no knowledge. This requires good, advanced technical knowledge. I mean, if you don't know these, you CAN'T ask these questions; if you can't ask such questions, you CAN'T improve your production capability’.

To establish a trustworthy and credible account we paid particular attention to achieving intra- and inter-coder reliability (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2004). Intra-coder reliability was achieved through prolonged engagement with and persistent observation of the data (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) which yielded stable results when segments of data were coded and recoded (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2004). To achieve inter-coder reliability, we began with both authors coding the same two interviews with codes being compared and differences being discussed and resolved (Ahn, Dik, & Hornback, Reference Ahn, Dik and Hornback2017). During these discussions, it was found that the author who had conducted the interview would have a deeper understanding of the interviewee, the organisation and the matter discussed in that segment of the interview, which would help to resolve the discrepancies in coding. After some practice and calibration, the two authors proceeded to code the interviews they had conducted originally.

Phase 2. Analysing the interplay between emotion and capability development initiatives

Following the multiple case study method, case narratives for each organisation were written (totalling 56 pages across the five cases). The case narratives provided rich and detailed descriptions of the contexts – the prime criterion for ensuring transferability and dependability of emerging results as they, when engaged seriously and deeply, sensitised us to the circumstances that affect the validity of emerging theorising (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985).

The interaction between the emotion and capability development initiatives were analysed using these case narratives, in-depth, noting the links between the two. The analysis process then moved onto iteratively reviewing the data, looking for patterns and differences through a process of constant comparison (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1984) across the five cases. We paid particular attention to the rival cases to scrutinise the dependability of emerging theorising of the interplay between emotions and capability development. By the end of this stage, a prototypical pattern was identified that captured different emotions and associated outcomes with regards to capability development. At this stage, these relationships were captured in a conceptual model.

To finalise the data analysis, the two authors next met in person and reviewed the case narratives again, over the course of three days, to check and make final refinements to the conceptual model. This allowed us to further improve the credibility, dependability and confirmability by creating a space to engage in a reflexive dialogue, audit decisions made, and bracket out the predispositions and interpretations of each author explicitly. The measures we put in place to ensure quality, inspired by Lincoln and Guba's (Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) study on quality assessment criteria, is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Criteria for assessing research quality and techniques to ensure quality

Findings

The data analysis established two themes, each discussed in turn below. As the data analysis progressed, more depth and complexity was uncovered. This complexity is captured in the following sub-sections.

The impact of emotions on capability development

The data illuminate a complex and nuanced relationship between key strategists' emotions and capability development. These relationships are mapped onto the circumplex model in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Impact of individual level emotions on organisational capabilities using the circumplex model.

It was found pleasant emotions, depending on the level of activation, can support or hinder capability development. High activation pleasant emotions (top right quadrant of Figure 2) enable capability development, but low activation pleasant emotions, for example contentment, are a barrier to capability development (bottom right quadrant).

High activation pleasant emotions triggered a more proactive stance to capability development in all five organisations. For example, interest and enthusiasm enabled sales channel development capability in Oil Co. Oil Co is not only alert towards competitor activities, rival products and customer trends but also demonstrates zeal in developing new channels to open up its products to wider markets and alters the packaging and pricing strategies to tap into those markets:

‘…if I have three merch teams in Bodrum [a holiday town in Western Turkey] during summer and if I need only one during winter, I open up new markets for those two merch teams. I ask them to go and show their face in new towns. This forces me to grow – because next summer I will then need two new merch teams in Bodrum and so it goes… And I know that this will sound very unsystematic, but it is something we do routinely for channel development: when me, my brothers, my team visit new places we note down prospective sales points. We are continuously scanning, can we put our oil in a ceramic bottle in this restaurant, shall I send a merch team to this deli shop’. (Oil Co Marketing and Communications Director)

In IT Co, the interest and enthusiasm of the technical director in new technologies enabled service development:

‘he's [the technical director] got this passion like I used to have at that age for new stuff and for keeping up with technology…he's very very focused, you know, in this field, so I'm letting him run with that and all I'm doing I'm just saying “right well OK that looks like a good area”…he's the one who's investigating and coming up with the ideas'. (IT Co Owner-Manager)

‘I've always been interested; the good thing is technology changes all the time there's enough there to keep you interested forever’. (IT Co Technical Director)

However, the relation between pleasant emotions and capability development is observed to be complex as these emotions only catalyse capability development if accompanied by high activation. Evidence from both IT Co and Merchandising Co shows that when organisational actors experience low activation pleasant emotions this constrains capability development (bottom right quadrant). For example, Merchandising Co's owner-managers' contentment at remaining a small business impeded capability development in the past:

‘We certainly could have been more dynamic if we hadn't sort of to a degree been happy to remain a small business'. (Merchandising Co Owner-Manager)

The influence of unpleasant emotions on capability development is also complex, not affording linear explanations. Although in Rubber Co unpleasant emotions only hindered capability development, their influence was more complex in Merchandising Co, Brakes Co and IT Co, where they were both a hindrance and an enabler. Low activation unpleasant emotions (bottom left quadrant) always hindered capability development. High activation unpleasant emotions (top left quadrant), however, could hinder or enable capability development. In IT Co, for example, the owner-manager's apprehension at times constrained him taking risks associated with implementing strategy to develop capabilities. This was fuelled by worry (top left quadrant) about being able to sustain his employees' livelihoods:

‘you've got to have the bottle to do it and right at this moment in time I could do with a kick up the arse and somebody helping me do that, you know, easy to know it very very very difficult to do it because it's not just my business and my livelihood, it's everybody who I've got here as well’. (IT Co Owner-Manager)

Yet, this same emotion, on another occasion, triggered strategic change at IT Co when the firm developed process capabilities to become a managed service provider which improved the organisation's cash flow:

‘I worry sometimes, I mean, I've been in the situation where I've no money in the company, people aren't paying me, you know, I might be owed thirty thousand pounds but I've got, you know, negative in the bank because the companies just aren't paying me and I've been in that situation more than once and I've paid the employees and not paid myself…we turned it round and we try and get the work where they're paying on a monthly basis so we get MRR, monthly recurring revenue, so that's what I'm more into and that's why we've turned the way the business works and what we do and, you know, go in as an MSP [managed service provider]’. (IT Co Owner-Manager)

In Brakes Co, high activation negative emotions (top left quadrant) only enabled capability development. In the following interview extract, for example, it is seen how the dissatisfaction and irritation of the production director with the knowledge base of the organisation drives human resources capability development and process capability development. Here, the production director is responding to the interviewer's question about who determines opportunities for process capability development:

‘Of course, they are all things that I do. I mean, data are collected but not analysed. For example, they know that they use 25,000 tips a year to process brake drums, but no one asks, “Why are we using 25,000, can we decrease our tip consumption to 12,000 units?” There is no questioning because there is no knowledge … Here we're working with inexperienced colleagues. In firms applying Six Sigma, for example, operators initiate projects and engineers work as supervisors. Here, operators don't have such technical backgrounds; they cannot think, let alone do something about it … I am seeing a severe technical inadequacy in terms of the knowledge base, the skills base here’. (Brakes Co Production Director)

This dissatisfaction with the current technical knowledge base is driving Brakes Co's human resources capability development to remove the source of unpleasant emotions:

‘We are slowly building up our technical knowledge infrastructure. Our engineering team has built significant expertise in recent years. And slowly we have started to bring them to the fore. They aren't really in a position to solve process problems fully yet, but they're slowly getting there’. (Brakes Co Production Director)

In IT Co and Rubber Co low activation unpleasant emotions (bottom left quadrant in Figure 2) have stalled strategic growth and associated capability development. For example, in Rubber Co, the marketing and sales director's hopelessness about the prospects of the national market limited the development of marketing capabilities:

‘National market is really, you know, impossible… We are trying to hang on to our existing customers…. What I want to say is, for example, we have no prior relationship with [NAMES THE ORGANISATION DIRECTLY], starting to work for them is very difficult … Because everybody has their suppliers sorted and they even have a list of alternative suppliers. They aren't very sympathetic towards taking new suppliers on board. And even if they were, there are many others in the same position ready to jump on’. (Rubber Co Marketing and Sales Director)

Overall, low activation emotions constrain capability development regardless of the pleasantness of emotions experienced. Here, actors will not experience the sense of mobilisation and action readiness to undertake necessary capability development. High activation emotions have a more complex, less linear influence. When accompanied by pleasant emotions (e.g., enthusiasm, excitement and zeal) high activation is always an enabler of capability development. However, when accompanied by unpleasant emotions (e.g., frustration, anxiety and worry), high activation has a less linear influence. Evidence from three case organisations suggests that dissatisfaction with the current situation catalyses capability development. However, anxiety and worry, which are again high activation unpleasant emotions, do not afford a definitive pattern; and can act both as an enabler and barrier even within the same organisation. This yields paradoxes, underscoring complexities of organisations. The complex relationship between key strategists' emotions and capability development, we unravelled, outlies a definitive pattern between the two constructs, and challenges simplistic rendering of capability development process.

Emotional tensions: inside the organisation and inside the individual

The interplay between emotion and capability development takes an additional layer of complexity when considering emotional tensions. Emotional tensions between different organisational actors were identified within two case organisations (IT Co and Merchandising Co). In IT Co, there was also tension in the form of emotional ambivalence within the owner-manager himself. Both types of tensions influenced capability development.

In IT Co, the interest and enthusiasm (top right quadrant of Figure 2) of the technical director, which drives capability development, met the owner-manager's apprehension (top left quadrant), which can constrain capability development. In Merchandising Co, a somewhat similar tension can be observed in that the owner-manager displays predominantly high activation pleasant emotions such as hope and confidence, which contrasts with his partner's (who is also his wife) high activation unpleasant emotion, in the form of discomfort. This tension can influence capability development:

‘I think we're almost at the stage where I could write a business plan for major growth and either take on a loan, a re-mortgage, or something like that and go for premises and do a major period of growth. I'm confident I could do the marketing and the sales… And I'm not sure how comfortable that, being sort of only maybe like ten years away from retirement anyway, that my wife would be with taking on a major change at this stage’. (Merchandising Co Owner-Manager)

Evidence from IT Co showed that emotional ambivalence within the owner-manager also influences capability development. For example, the owner-manager recognises that stepping away from the day-to-day work of the organisation is important for identifying and moving in new strategic directions, and therefore for capability development. Nevertheless, he has been struggling to step away which creates frustration with himself:

‘You need to be able to step back to think. You can't think while you're in it [the organisation]. I don't have the time. I haven't got the energy. I need to pull, and the trouble is I know this, I've done it, I know it works, but for some reason I just can't seem to be able to do it again and it's because I'm sucked back into the job and I'm finding it so difficult to leave the desk and working on the job to leave it and work on the business itself’. (IT Co Owner-Manager)

This frustration (high activation unpleasant emotion) is at odds with the contentment and comfort (low activation pleasant emotion) he experiences with his day-to-day involvement in the organisation. This, he believes, impacts his ability to step out, which in turn hinders capability development:

‘The pressures of staffing levels and business it's meant I've had to jump back into the business. Now that's OK, I find it easy to jump back in, but I find it so so difficult to come back out of it again because it's what I know, it's what I understand, I'm comfortable with it’. (IT Co Owner-Manager)

Emotional ambivalence is further reflected in his interest and enthusiasm towards developing and growing IT Co and his simultaneous apprehension and weariness in committing to capability development to implement this:

‘I'd love nothing more now than to have sort of like that one-to-one mentoring again, where I could sit with somebody who can just talk around the issues and the problems and where we need to fit and go so I can develop this business, you know, and get more staffing levels, put more employment out there, you know, that's what I want to do. But it's so difficult, it's such a risk…it's getting that gut feeling and, I don't know, balls to do it. You've got to be able to do it and I'm at that stage now I need this, but I'm tired, and basically, I need help to be able to get that energy back, that spark back, to do it again. I know all this but doing it is different’. (IT Co Owner-Manager)

The inter- and intra-individual emotional tensions highlighted above represent an emotional battle – either between individuals or within a single individual – in which the fate of particular capability development initiatives hang in the balance. This suggests that how actors respond to these tensions will determine capability development outcomes, or the lack thereof.

Discussion

Empirical and conceptual research is beginning to show the importance of emotions for strategic choice (Vuori & Huy, Reference Vuori and Huy2015), organisational change (Huy, Reference Huy2002; Maitlis & Sonenshein, Reference Maitlis and Sonenshein2010), innovation (Akgün, Keskin, & Byrne, Reference Akgün, Keskin and Byrne2009), entrepreneurial action (Baron, Tang, & Hmieleski, Reference Baron, Tang and Hmieleski2011; Cardon, Wincent, Singh, & Drnovsek, Reference Cardon, Wincent, Singh and Drnovsek2009) and organisational learning (Scherer & Tran, Reference Scherer, Tran, Dierkes, Berthoin Antal, Child and Nonaka2003). This paper extends this research by exploring the role emotion plays in capabilities and how they are developed to effect strategic change. It does so by explicitly focusing on a range of emotional states, in contrast to some of the leading papers in the field (e.g., Huy, Reference Huy2002; Vuori & Huy, Reference Vuori and Huy2015). The findings suggest key strategists' emotions influence capability development in too complex a way to afford straightforward solutions, with no single emotion category being uniformly beneficial or detrimental.

A large body of psychology, human resource management and strategic management research has associated pleasant emotions with benefits including energy, enhanced cognitive flexibility, increased innovation and adoption of more challenging goals (e.g., Cardon et al., Reference Cardon, Wincent, Singh and Drnovsek2009; Huy, Reference Huy2002; Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, Reference Lyubomirsky, King and Diener2005). In line with these studies it is found that in all five organisations pleasant emotions can act as an enabler of capability development. However, the link is not as straightforward as suggested in the extant literature. Our findings suggest that this is only so when pleasant emotions are accompanied by high activation, which drives a pursuit of accomplishment in organisational actors (Faria, Reference Faria2011).

The study also finds that pleasant emotions are not always beneficial, which further highlights the complexity of the relationship between emotions and capability development. Some scholars have found that positive emotions, such as feeling content, can signal objectives are already achieved and this signal can make people less perceptive and less critical acting as a barrier to organisational development (George & Zhou, Reference George and Zhou2002). These findings were conflicting with most empirical research arguing for the inherent goodness of positive emotions. In this paper, having distinguished emotional states on two separate dimensions (i.e., pleasant vs. unpleasant, high vs. low activation), we are able to achieve a more nuanced analysis of different types of pleasant emotions and their distinct influences on capability development. The paper shows that in order to understand the implications on capability development we should not only consider the pleasantness of the emotions, but also the level of activation at which they are experienced. Accounting for pleasantness and activation we unearth a more complex, yet much richer, relationship between emotions and capability development.

The influence of unpleasant emotions is also a contested issue in extant research. Although some authors argue unpleasant emotions motivate behaviour by driving individuals to address a discrepancy between current and desired states (e.g., Hochschild, Reference Hochschild1983), insights from the management literature suggest people experiencing unpleasant emotions will seek continuity and security which can cause myopic decision-making (e.g., Dane & George, Reference Dane and George2014; Vuori & Huy, Reference Vuori and Huy2015). The current study's use of the circumplex model allows us to draw differences between different types of unpleasant emotions and nuanced implications for capability development.

Aligning with insights from psychology literature, Merchandising Co, Brakes Co and IT Co suggest high activation unpleasant emotions, in the form of frustration and irritation with the current state, can trigger problem-solving to drive capability development aimed at improving the current strategic position. This led to a range of productivity improvement projects at Brakes Co and a commitment to improve service desking at IT Co to resolve the problems causing unpleasant emotions. Models of aspiration performance help explain this; performance below aspiration levels influences managerial decision-making and actions (Greve, Reference Greve2003) to undo unsatisfactory performance (Zhou & George, Reference Zhou and George2001).

However, evidence from the study suggests unpleasant emotions can also hinder capability development when actors experience low activation unpleasant emotions. This is observed in the form of hopelessness at Rubber Co and weariness at IT Co, characterised by lacking motivation to act. Unpleasant emotions, even when they are accompanied by high activation, can also be a barrier to capability development, as observed in IT Co and Merchandising Co where strategists' anxiety, tension and discomfort with certain investments stalled capability development. This observation aligns with studies which identified anxiety as a potential barrier reducing the array of thoughts and actions of organisational members (Fredrickson & Branigan, Reference Fredrickson and Branigan2005; McCracken, Reference McCracken2005). The fact that high activation unpleasant emotions can both enable and hinder capability development further supports our argument that emotions' influence on capability development is too complex to afford straightforward explanations.

When unpleasant emotions hinder capability development this is not always necessarily bad. Indeed, dual-tuning theory (George & Zhou, Reference George and Zhou2007) predicts that such emotions are beneficial to offset impulsiveness (De Young, Reference De Young2010) and escalation of commitment (Forgas & George, Reference Forgas and George2001). In Merchandising Co and IT Co, there are emotional tensions within the management team, with one strategist displaying predominantly high activation pleasant emotions about certain capability development initiatives and the other displaying predominantly high activation unpleasant emotions. Within this dynamic the apprehensiveness and tension experienced by one strategist constrain overenthusiasm and overconfidence of the other, thus resulting in careful consideration of ideas, underlying assumptions, and supporting and conflicting information related to the capability development initiatives.

The interpersonal emotional tensions identified in Merchandising Co and IT Co indicate another contribution of the study – that conflicting emotional states within an organisation can impact capability development. Studies exploring the relationship between emotion and capabilities have tended to research emotion as an organisationally observed phenomena, such as fear experienced by Nokia managers in Vuori and Huy (Reference Vuori and Huy2015). However, we found that even in very small organisations opposing emotional states can impact capability development. A particularly interesting finding is the role of emotional ambivalence within one individual in capability development in IT Co.

Emotional ambivalence refers to individuals having mixed feelings about a target (Pratt & Doucet, Reference Pratt, Doucet and Fineman2000). In the case of IT Co's owner-manager, there are two primary targets that elicit emotional ambivalence – stepping back from the organisation, and capability development. First, the owner-manager's failure to step back from the day-to-day work of IT Co to focus more on capability development elicits contentment, but at the same time frustration. Second, capability development itself elicits interest and enthusiasm in concert with apprehension and weariness.

The findings that emotional ambivalence can be involved in capability development are important since ‘incidences of unidimensional states, such as pure happiness or pure sadness, are actually quite rare’ (Fong, Reference Fong2006: 1016). Emotional states are not experienced in a straightforward manner; positive and negative states co-occur at varying levels of intensity (Diener & Iran-Nejad, Reference Diener and Iran-Nejad1986). And as such, emotional ambivalence is likely to be common in organisations (Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt, & Pradies, Reference Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt and Pradies2014); particularly in SMEs since their strategists tend to operate under conditions of ambiguity and unpredictability (Podoynitsyna, Van der Bij, & Song, Reference Podoynitsyna, Van der Bij and Song2012).

There has been an appreciation that emotional ambivalence can be observed when organisational actors respond to strategic change decisions (Piderit, Reference Piderit2000; Sillince & Shipton, Reference Sillince and Shipton2013). However, little attention is given to emotional ambivalence experienced by key strategists when deciding for strategic change. A rare exception is Podoynitsyna, Van der Bij, and Song (Reference Podoynitsyna, Van der Bij and Song2012) who found that ambivalence can lead to higher risk perceptions by entrepreneurs. The current paper contributes to this literature by highlighting that emotional ambivalence among key strategists can influence capability development to effect strategic change. This theoretical contribution is important since individuals' responses to emotional ambivalence will have implications for capability development. Indeed, Ashforth et al. (Reference Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt and Pradies2014) developed a typology of potential responses to ambivalence within organisational contexts. Considering three of the responses in their typology – avoidance, compromise and domination – can illustrate how different responses by IT Co's owner-manager to his emotional ambivalence could have varying influences on capability development. To illustrate this, let us consider the owner-manager's ambivalence towards capability development.

If IT Co's owner-manager responded to his ambivalence by ignoring and not dealing with it (Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt and Pradies2014) this would likely lead to non-response (Pratt & Doucet, Reference Pratt, Doucet and Fineman2000). Alternatively, compromise could be his response, which would involve him making concessions to accommodate both the pleasant and unpleasant emotions (Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt and Pradies2014). This could result in cautious (or limited) capability development, thus accommodating his interest and enthusiasm, at the same time as his anxiety, apprehension and weariness. Finally, domination could be his response, meaning that he could either let his positive emotions overwhelm his negative emotions or vice versa (Ashforth et al., Reference Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt and Pradies2014). If he pays more attention to his interest and enthusiasm for developing IT Co, this would result in capability development going ahead in a strong form. If he focused more on his apprehension and weariness though, this would overpower his interest and enthusiasm, likely meaning that capability development would not go ahead. As such, three different types of responses to his ambivalence could have markedly different impacts on capability development in IT Co, with avoidance stalling capability development, compromise leading to cautious capability development and domination leading to either strong capability development or no capability development. Such implications showing how emotional ambivalence can impact capability development in varied ways provides an insightful theoretical contribution of the study that is worthy of further research.

Conclusion

Although capabilities are of fundamental importance to organisations, relatively little is known about their emotional foundations. Even though recent conceptualisations of dynamic capabilities have signalled the importance of emotion (e.g., Vuori & Huy, Reference Vuori and Huy2015), because it is subsumed under cognition-based models it has not benefited from adequate empirical treatment. This paper responds to the calls of Huy (Reference Huy2012), Hodgkinson and Healey (Reference Hodgkinson and Healey2011) and MacLean, MacIntosh, and Seidl (Reference MacLean, MacIntosh and Seidl2015) by providing in-depth empirical insights into the role of strategists' emotions in capability development while distinguishing between positive and negative emotions and accounting for the intensity at which they are experienced (Sinclair, Ashkanasy, & Chattopadhyay, Reference Sinclair, Ashkanasy and Chattopadhyay2010).

Through inductive, in-depth research in five organisations we explored emotional foundations of capability development and contributed insights into the multifaceted ways in which a range of emotions, including emotional ambivalence, can enable and hinder capability development. This adds to extant understanding of the psychological foundations of capability development (Hodgkinson & Healey, Reference Hodgkinson and Healey2011) and simultaneously extends scholarly conversations regarding microfoundations of capabilities (Barney & Felin, Reference Barney and Felin2013). Capability development can be a source of competitive advantage, and therefore, by furthering understanding of its emotional foundations the paper adds valuable knowledge towards a fuller and deeper conceptualisation of dynamic capabilities and their development.

We suggest that emotions influence capability development in too complex a way to afford straightforward solutions, with no single emotion category being uniformly beneficial or detrimental. However, the multi-faceted impact emotions have on capability development shows the need for practicing managers to pay attention to their emotions and recognise how their emotions can act as an enabler or barrier to capability development.

The rich descriptions of the emotional microfoundations of capabilities in five organisations facing varying levels of environmental turbulence can help managers, beyond key strategists who have a role in capability development (Taylor & Helfat, Reference Taylor and Helfat2009), in other industries and contexts. They can glean insights into the range of emotions that may help secure the success of their capability development initiatives. With an improved awareness of the relationship between emotions and capabilities, managers can start recognising how their emotions interact with their decisions and actions regarding capability development. Such self-reflection and emotional self-awareness will allow practicing managers to equip themselves with approaches to generate emotions conducive to capability development. Neither emotions nor dynamic capabilities are fixed, but rather they evolve and interact, and therefore, this reflective process needs to be constantly revisited, to ensure that emotions, whether positive or negative, are utilised for productive purposes.

This paper can also inform initiatives of institutions concerned with management learning and leadership development, to tailor their training offerings to equip managers with competencies and mindsets to utilise emotions for productive purposes. Many governmental agencies and not-for-profit institutions (such as federations of small businesses) are increasing the supply of mentors to train members of the SME business community. The insights from our research can feed into such initiatives by training mentors to help their mentees (managers) to reflect on their own emotions and recognise how this may impact upon their organisations' capability configurations.

For such benefits to be fully realised, further research is needed into organisations of different sizes operating in different industries. Case-based research can be difficult to generalise to other populations (Grant & Verona, Reference Grant and Verona2015) and, as such, a more voluminous dataset would be useful to increase the transferability of our insights to differing organisational contexts. The influence of emotion on capability development also merits further exploration through a longitudinal study adapting a practice-/process-based perspective. This would provide opportunities to observe emotion ‘in action’ and capture more of the relational aspect of emotion at the inter-individual level. A practice-/process-based perspective might allow researchers to capture multi-directional emotional dynamics at play in organisations. Some questions to guide further research include: How can key strategists' emotions and actions be scaled up to generate an organisational emotional climate conducive to capability development? Recognising emotional contagion and emotional mimicry is also important to explore how the dominant organisational emotional climate or the emotions of others in the management team shape the key strategists' emotions and their decisions about capability development. When organisational emotional ambivalence occurs within the management team how is this resolved, and which emotions win? Future research can also investigate whether diversity of emotions within a management team helps or hinders capability development.

This paper is a further step away from the normative, predictive explanations of the concept of dynamic capabilities in the literature, acknowledging its open-ended nature emerging from the interaction of a multitude of organisational microfoundations. Engaging with the above listed questions will move the field towards a more context-based and variable understanding of dynamic capabilities.