Introduction

Online recruitment by violent extremist organizations has proven to be a pernicious problem. In recent years, hundreds of US and European citizens have joined extremist organizations in the Middle East or were apprehended in the attempt (Brumfield, Reference Brumfield2014). Such organizations increasingly rely on the Internet, as it is considered to enable a safer approach with lower chances of being tracked by law enforcement agencies (Rashid, Reference Rashid2017). Extremist organizations are also active on social media platforms, such as Twitter, to spread propaganda and to recruit and radicalize new members (International Crisis Group, 2018). For example, after the outbreak of violence in Syria in 2011, radical groups became more active on Twitter, making it a hub for disseminating extremist content and directing users to a range of other digital platforms used by these groups (Stern & Berger, Reference Stern and Berger2015). An analysis of approximately 76,000 tweets, captured over a 50-day period in 2013, revealed that they contained more than 34,000 short links to various kinds of jihadist content and connected a network of more than 20,000 active Twitter accounts (Prucha & Fisher, Reference Prucha and Fisher2013).

As part of their recruitment efforts, radical groups typically share footage containing violence and music videos, as well as multilingual written content such as that found in glossy magazines (Prucha & Fisher, Reference Prucha and Fisher2013; Hall, Reference Hall2015). For example, in May 2013, Twitter was used to publicize the 11th issue of Al-Qaeda's English-language online magazine, highlighting the use of social media by such organizations (Prucha & Fisher, Reference Prucha and Fisher2013; Weimann, Reference Weimann2014). Aside from sharing propaganda content, radical groups have also used Twitter to communicate with sympathizers and to cultivate a community of supporters. The Islamic State has been particularly effective at this, reaching upwards of 100,000 people on Twitter between 2014 and 2015 (Berger & Morgan, Reference Berger and Morgan2015; Hosken, Reference Hosken2015). Another recruitment avenue that is commonly used by extremist organizations consists of direct messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Telegram, which are end-to-end encrypted and therefore difficult to monitor externally (Rowland, Reference Rowland2017; Radicalisation Awareness Network, 2019).

In response, social media companies have taken measures such as suspending accounts used by ISIS supporters, but to little avail, as duplicate accounts can be generated almost immediately (Berger & Morgan, Reference Berger and Morgan2015; Lewis, Reference Lewis2015). In addition, easy-access message encryption and other methods for “covering one's tracks” make the effective tracking and following of extremist organizations and their members extremely difficult (Graham, Reference Graham2016). Governments and international organizations have therefore also sought to prevent or counter violent extremism through skills development and education (Sklad & Park, Reference Sklad and Park2017), youth empowerment, strategic communications and promoting gender equality (United Nations, 2015).

However, questions have been raised about the effectiveness of such efforts as well. Specifically, the lack of emphasis on “what works” for the prevention of violent extremism and the sparse usage of methods and insights from behavioral science and psychology to develop and test interventions have been noted (Schmid, Reference Schmid2013; Gielen, Reference Gielen and Colaert2017; Holdaway & Simpson, Reference Holdaway and Simpson2018). Research has also highlighted some methodological issues with existing tools (Sarma, Reference Sarma2017), including validation and reliability problems, low base rates, the lack of generalizability of interventions and an inability to capture the diversity of the backgrounds of radicalized individuals (Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2018). The radicalization process is exceedingly complex, and it is related to motivational dynamics, including a quest for identity, a search for purpose and personal significance (Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014; Dzhekova et al., Reference Dzhekova, Stoynova, Kojouharov, Mancheva, Anagnostou and Tsenkov2016), the pursuit of adventure (Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Birdwell and King2010; Dzhekova et al., Reference Dzhekova, Stoynova, Kojouharov, Mancheva, Anagnostou and Tsenkov2016) or circumstantial and environmental factors such as extended unemployment or disconnection from society due to incarceration, studying abroad or isolation and marginalization (Precht, Reference Precht2007; Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Birdwell and King2010; Doosje et al., Reference Doosje, Moghaddam, Kruglanski, de Wolf, Mann and Feddes2016; Dzhekova et al., Reference Dzhekova, Stoynova, Kojouharov, Mancheva, Anagnostou and Tsenkov2016). Doosje et al. (Reference Doosje, Moghaddam, Kruglanski, de Wolf, Mann and Feddes2016) break down these factors into micro-, meso- and macro-levels that cut across different stages of radicalization. The micro-level represents individual factors (e.g., a quest for significance or the death of a relative). The meso-level involves group-related factors (e.g., fraternal relative deprivation, or “the feeling of injustice that people experience when they identify with their group and perceive that their group has been treated worse than another group”; see Crosby, Reference Crosby1976; Doosje et al., Reference Doosje, Moghaddam, Kruglanski, de Wolf, Mann and Feddes2016). Finally, the macro-level consists of factors at the societal or global level (e.g., accelerating globalization). It is important to note that those who harbor extremist sentiments might not necessarily engage in any active form of terrorism, and those who do so might only have a cursory understanding of the ideology that they claim to represent (Borum, Reference Borum2011; Doosje et al., Reference Doosje, Moghaddam, Kruglanski, de Wolf, Mann and Feddes2016; McCauley & Moskalenko, Reference McCauley and Moskalenko2017). In fact, there appears to be broad agreement that there is no single cause, theory or pathway that explains all violent radicalizations (Borum, Reference Borum2011; Schmid, Reference Schmid2013; McGilloway et al., Reference McGilloway, Ghosh and Bhui2015).

In a field of research that deals with difficult-to-access populations, oftentimes in fragile and conflict-affected contexts, mixed evidence exists as to what interventions are effective at reducing the risk of individuals joining extremist organizations (Ris & Ernstorfer, Reference Ris and Ernstorfer2017). This highlights a strong need for an empirical and scientific foundation for the study of radicalization and the tools and programs used to prevent and combat violent extremism (Ozer & Bertelsen, Reference Ozer and Bertelsen2018).

Inoculation theory

The most well-known framework for conferring resistance against (malicious) persuasion is inoculation theory (McGuire, Reference McGuire1964; Compton, Reference Compton, Dillard and Shen2013). Much like how a real vaccine is a weakened version of a particular pathogen, a cognitive inoculation is a weakened version of an argument that is subsequently refuted, conferring attitudinal resistance against future persuasion attempts (McGuire & Papageorgis, Reference McGuire and Papageorgis1961, Reference McGuire and Papageorgis1962; Eagly & Chaiken, Reference Eagly and Chaiken1993). The process of exposing individuals to weakened versions of an argument and also presenting its refutation has been shown to robustly inoculate people's attitudes against future persuasive attacks. For example, a meta-analysis of inoculation research revealed a mean effect size of d = 0.43 across 41 experiments (Banas & Rains, Reference Banas and Rains2010). In fact, McGuire's original motivation for developing the theory was to help protect people from becoming “brainwashed” (McGuire, Reference McGuire1970).

In recent years, inoculation theory has been shown to be a versatile framework for tackling resistance to unwanted persuasion in a variety of important contexts. For example, inoculation theory has been applied in order to confer resistance against misinformation about contemporary issues such as immigration (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2018), climate change (van der Linden et al., Reference van der Linden, Leiserowitz, Rosenthal and Maibach2017), biotechnology (Wood, Reference Wood2007), “sticky” 9/11 conspiracy theories (Banas & Miller, Reference Banas and Miller2013; Jolley & Douglas, Reference Jolley and Douglas2017), public health (Compton et al., Reference Compton, Jackson and Dimmock2016) and the spread of fake news and misinformation (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2019; Basol et al., Reference Basol, Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020; Roozenbeek et al., Reference Roozenbeek, van der Linden and Nygren2020b).

An important recent advance in inoculation research has been the shift in focus from “passive” to “active” inoculations (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2018, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2019). In passive inoculation, a weakened argument is provided and also refuted at the same time, in which case the individual would only passively process the exercise, such as through reading. In comparison, during active inoculation, an individual is more cognitively engaged and actively partakes in the process of refuting the weakened argument (e.g., by way of a game or a pop quiz). Research suggests that active inoculation can affect the structure of associative memory networks, increasing the nodes and linkages between them, which is thought to strengthen resistance against persuasion (Pfau et al., Reference Pfau, Ivanov, Houston, Haigh, Sims, Gilchrist, Russell, Wigley, Eckstein and Richert2005). In addition, by focusing on the underlying manipulation techniques rather than tailoring the content of the inoculation to any specific persuasion attempt (Pfau et al., Reference Pfau, Tusing, Koerner, Lee, Godbold, Penaloza, Shu-Huei and Hong1997), this advance offers a broad-spectrum “vaccine” that can be scaled across the population. This is especially important for behavioral research, which has been criticized for not tackling more complex social issues such as preventing violent extremism (van der Linden, Reference van der Linden2018).

The present research

According to the literature on the prevention of violent extremism, there are various settings in which recruitment by radical groups can take place, converting individuals with “ordinary” jobs who, in many cases, appear to be living ordinary lives, with little or no criminal history, into committed members of a radical or terrorist organization (McGilloway et al., Reference McGilloway, Ghosh and Bhui2015). The existing literature focusing on extremist recruitment highlights four key stages in this process:

(1) Identifying individuals who are vulnerable to recruitment (Precht, Reference Precht2007; Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Birdwell and King2010; Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2018).

(2) Gaining the trust of the selected target (Walters et al., Reference Walters, Monaghan and Martín Ramírez2013; Doosje et al., Reference Doosje, Moghaddam, Kruglanski, de Wolf, Mann and Feddes2016).

(3) Isolating the target from their social network and support circles (Doosje et al., Reference Doosje, Moghaddam, Kruglanski, de Wolf, Mann and Feddes2016; Ozer & Bertelsen, Reference Ozer and Bertelsen2018).

(4) Activating the target to commit to the organization's ideology (Precht, Reference Precht2007; Doosje et al., Reference Doosje, Moghaddam, Kruglanski, de Wolf, Mann and Feddes2016; Ozer & Bertelsen, Reference Ozer and Bertelsen2018).

These four stages of extremist recruitment techniques constitute the backbone of the present study. In order to address the pitfalls that at-risk individuals might be vulnerable to in each stage of recruitment, we developed and pilot-tested a novel online game, Radicalise, based on the principles of inoculation theory and grounded in the reviewed academic literature regarding online extremist recruitment techniques. The game consists of four stages, each focusing on one of the recruitment techniques defined above. Radicalise was developed to entertain as well as to educate, and to test the principles of active inoculation in an experiential learning context. The game draws inspiration from Bad News,Footnote 1 an award-winningFootnote 2 active inoculation game developed by Roozenbeek and van der Linden and the Dutch anti-misinformation platform DROG (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2019). The free online game has been shown to increase attitudinal resistance against common misinformation techniques and to improve people's confidence in spotting misleading content (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2019; Basol et al., Reference Basol, Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020; Maertens et al., Reference Maertens, Roozenbeek, Basol and van der Linden2020; Roozenbeek et al., Reference Roozenbeek, van der Linden and Nygren2020b).

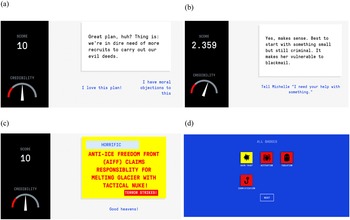

The Radicalise game, which takes about 15 minutes to complete, simulates a social media environment in which players are presented with images, text and social media posts that mimic the environment in which the early stages of extremist recruitment take place (Alarid, Reference Alarid, Hughes and Miklaucic2016). These stages are sequenced as four levels, each representing one of the above recruitment techniques: (1) identification; (2) gaining trust; (3) isolation; and (4) activation. More information on each stage and the academic literature behind them can be found in Supplementary Table S1. Players are presented with two or more response options to choose from, affecting the pathways they take in the game, as shown in Figure 1. Players are given a “score” meter, which goes up as they progress correctly and down if they make mistakes, and a “credibility” meter, which represents how credible their “target” finds the player, and goes up or down depending on their choices. If the “credibility” meter reaches 0, the game is over and the player loses.

Figure 1. User interface of the Radicalise game. Note: Panels (a), (b) and (c) show how messages during the game are presented, the answer options from which players can choose and the score and credibility meters. Panel (d) shows the four badges that players earn after successfully completing the four stages in the game.

In the game, players are required to assume being in a position of power within a fictitious and absurd extremist organization, the Anti-Ice Freedom Front (AIFF), whose evil objective is to blow up the polar ice caps using nuclear weapons. Players are tasked with identifying and recruiting an individual into the AIFF through social media. Playing as the AIFF's “Chief Recruitment Officer,” players are prompted to think proactively about how people might be misled in order to achieve this goal. The rationale behind choosing to have players take the perspective of the recruiter, following Roozenbeek and van der Linden (Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2019), is to give vulnerable individuals, for whom this game is designed, the opportunity to feel empowered and to see things from the perspective of a person of high rank and who has the power to manipulate, blackmail and coerce vulnerable people into doing ill deeds.

This form of perspective-taking allows participants to understand how they might be targeted without being labeled themselves as vulnerable. Doing so reduces the risk of antagonizing players while simultaneously giving insight into how they may be targeted by extremists. Evidence from the literature suggests that perspective-taking affects attributional thinking and evaluations of others. For example, studies have shown that perspective-takers made the same attributions for the target that they would have made if they themselves had found themselves in that situation (Regan & Totten, Reference Regan and Totten1975; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Conklin, Smith and Luce1996). In addition, this perspective-taking exercise potentially reduces the risk of reactance, or the possibility that the effectiveness of the intervention is reduced because participants feel targeted or patronized (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Ivanov, Sims, Compton, Harrison, Parker, Parker and Averbeck2013; Richards & Banas, Reference Richards and Banas2015). We therefore posit that by giving people the opportunity to experience and orchestrate a simulated recruitment mission, the process helps to inoculate them and confers attitudinal resistance against potential real attempts to target them with extremist propaganda.

Hypotheses

The above discussion leads us to the following preregistered hypotheses: (1) people who play Radicalise perform significantly better at identifying common manipulation techniques used in extremist recruitment compared to a control group; (2) players perform significantly better at identifying characteristics that make one vulnerable to extremist recruitment compared to a control group; and (3) players become significantly more confident in their assessments.

Participants and procedure

To test these hypotheses, we conducted a preregistered 2 × 2 mixed randomized controlled trial (n = 291), in which 135 participants in the treatment group played Radicalise, while 156 participants in the control group played an unrelated game, Tetris.Footnote 3 The preregistration can be found at https://aspredicted.org/dj7v7.pdf.Footnote 4 The stimuli used in this study as well as the full dataset, analysis, and visualization scripts are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/48cn5/.

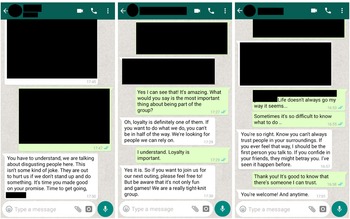

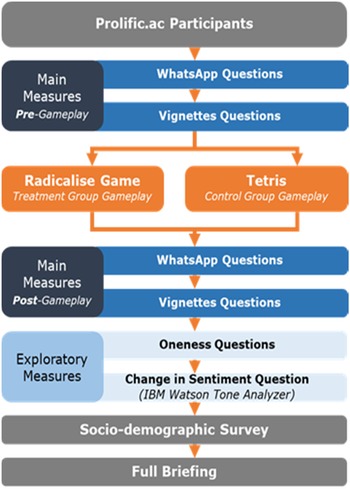

Based on prior research with similar research designs (Basol et al., Reference Basol, Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020), an a priori power analysis was conducted using G* power (α = 0.05, f = 0.26 (d = 0.52) and a power of 0.90, with two experimental conditions). The minimal sample size required for detecting the main effect was approximately 156 (78 per condition). We slightly oversampled compared to the initial preregistration (n = 291 versus n = 260). The sample was limited to the UK and was recruited via Prolific.ac (Palan & Schitter, Reference Palan and Schitter2018). The main reason why we limited the sample to the UK was that the Radicalise game was written in English, with primarily British colloquialisms and cultural references. In order to ensure that some of the details and references present in the game would be understood by all participants, we decided to limit the study to residents of the UK. In total, 57% of the sample identified as female. The sample was skewed towards younger participants, with 33% being between 25 and 34 years of age, and participants predominately identified as white (89%). A total of 69% of participants were either employed or partially employed. Political ideology skewed towards the left (43% left wing, 23% right wing, M = 2.69, SD = 1.04) and 43% were in possession of a higher education-level diploma or degree. Each participant was paid £2.09 for completing the survey. Participants started the experiment by giving informed consent, which included a high-level description of the experiment and its objectives. Before being randomized into control and treatment groups, participants underwent a pretest assessing their ability to spot manipulation techniques (in the form of simulated WhatsApp messages; see Figure 2) and the characteristics that can make individuals vulnerable to radicalization (in the form of vignettes; see Figure 3). The treatment group then played the Radicalise game, while the control group played Tetris for a period of about 15 minutes, similar to the average time it takes the treatment group to complete Radicalise (control group participants were asked to play attentively until the proceed button appeared, which occurred after 15 minutes of play time). Both Radicalise and Tetris were embedded within the Qualtrics survey software. Participants who played Radicalise were given a code at the end of the game, which they had to provide in order to show that they had fully progressed through the game. As preregistered, participants who failed to provide the correct code were excluded (n = 13), leaving a final sample of N = 291. After playing, participants answered the same outcome questions again, following the standard paradigm for testing such behavioral interventions (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2019; Basol et al., Reference Basol, Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020). Finally, participants answered a series of standard demographic questions: age group, gender, political ideology, self-identified racial background, education level, employment status, marital status (53.3% never married; 37.5% married), trust in government (M = 3.24, SD = 1.56, 1 being low and 7 being high), concern about the environmentFootnote 5 (M = 5.52, SD = 1.30, 1 being a low level of concern and 7 being high) and whether the state should provide financial benefits to the unemployed (11.7% no, 88.3% yes). See Supplementary Table S2 for a full overview of the sample and control variables. This study was approved by The London School of Economics Research Ethics Committee.

Figure 2. Simulated WhatsApp conversation examples (left: activation; middle: gaining trust; right: isolation). Note: Participants were asked to read a simulated WhatsApp conversation and answer a question on how manipulative they find the third party, as well as how confident they are in their answer.

Figure 3. Example of non-vulnerable (top left and top right) and vulnerable (bottom left and bottom right) profile vignettes. Note: Participants were asked to read an example of a profile vignette and then answer a question about the persona's vulnerability and the level of confidence in their answer.

Outcome measures

In order to test whether the game was effective at conferring resistance against manipulation strategies commonly used in extremist recruitment, we used two main outcome measures: (1) assessment of manipulation techniques; and (2) identification of vulnerable individuals.

Assessment of manipulation techniques

In order to evaluate participants’ ability to assess manipulation techniques, we used six fictitious WhatsApp messages that each made use of one of the manipulation strategies learned in the game. With this approach, we follow Basol et al. (Reference Basol, Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020) and Roozenbeek et al. (Reference Roozenbeek, Maertens, McClanahan and van der Linden2020a), whose measures included simulated Twitter posts to assess participants’ ability to spot misinformation techniques. We use simulated WhatsApp messages rather than Twitter posts for two main reasons: (1) the posts mimic interpersonal (person-to-person) communication, which makes WhatsApp a good fit, especially in the UK, where WhatsApp is used ubiquitously (Hashemi, Reference Hashemi2018); and (2) the posts simulate conversations between a recruiter and a potential recruit, for which WhatsApp and other direct messaging apps represent an important avenue of communication (Rowland, Reference Rowland2017; Radicalisation Awareness Network, 2019). A total of six WhatsApp messages, two for each of the “gaining trust,” “isolation” and “activation” stages of the Radicalise game, were used (participants’ ability to spot techniques related to the “identification” stage were measured using vignettes, detailed next). All messages were reviewed by a number of experts to evaluate the items’ clarity and accuracy, and more importantly to assess whether they were theoretically meaningful. Specifically, the posts were assessed for clarity and accuracy independently by three different individuals with knowledge of manipulation techniques used in extremist recruitment, without being told explicitly which posts fell under which manipulation technique. The posts went through numerous rounds of edits before being deemed acceptable by each expert independently. Information related to the third party in the WhatsApp conversation (name, profile picture, etc.) was blacked out to avoid factors that could bias participants’ assessments. Figure 2 shows an example of a WhatsApp item used in the survey. Supplementary Table S3 gives the descriptive statistics of all items used.

Participants were asked to rate how manipulative they found the sender's messages in each WhatsApp conversation, as well as how confident they felt in their judgment, both before and after gameplay, on a seven-point Likert scale. The order in which the messages were displayed was randomized to mitigate the influence of order effects. A reliability analysis on multiple outcome variables showed high intercorrelations between the items and thus good internal consistency for the manipulativeness measure (α = 0.76, M = 5.46, SD = 0.91), and for the confidence measure (α = 0.88, M = 5.78, SD = 0.93). Supplementary Table S4 shows the descriptive statistics for the confidence measure.

Identification of vulnerable individuals

In order to assess people's ability to identify vulnerable individuals (the “identification” stage of the game), we wrote eight vignettes (in the form of fake profiles) of people with characteristics that make them vulnerable to extremist recruitment and two vignettes containing profile descriptions of people who are not especially vulnerable. Our primary outcome variable of interest was whether people who play Radicalise improve in their ability to identify vulnerable individuals, rather than whether they would improve in their ability to distinguish between vulnerable and non-vulnerable individuals (which in the context of fake news is commonly called “truth discernment”; e.g., see Pennycook et al., Reference Pennycook, McPhetres, Zhang, Lu and Rand2020); we therefore include the two non-vulnerable vignettes as “control” items to ensure that participants are not biased towards finding everyone vulnerable, and we report these separately. We opted for a pre–post design in order to compare the change both internally and externally, as this helps to rule out the possibility of the uneven split biasing people towards finding all of the vignettes vulnerable. For a detailed discussion about the ratio of non-manipulative versus manipulative items, we refer to Roozenbeek et al. (Reference Roozenbeek, Maertens, McClanahan and van der Linden2020a) and Maertens et al. (Reference Maertens, Roozenbeek, Basol and van der Linden2020).

The vignettes did not contain pictures or information about people's age, and they used gender-neutral names and biographies to avoid any prejudice or bias. Participants were asked to rate how vulnerable to extremist recruitment they deemed each profile to be and how confident they felt in their answers, before and after playing, on a seven-point Likert scale. A reliability analysis showed high intercorrelations between the vignettes, indicating good internal consistency (α = 0.82 for the vulnerability measure and α = 0.94 for the confidence measure). Figure 3 shows an example. See Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 for the descriptive statistics for both the vulnerability and the confidence measures for all 10 vulnerable and non-vulnerable profile vignettes.

The experimental design is further illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Experimental design of the intervention. Note: Participants answered the same outcome measures before and after playing their respective games.

Results

A one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) reveals a statistically significant post-game difference between treatment group (M = 6.22, SD = 0.73) and control group (M = 5.64, SD = 0.90) for the perceived manipulativeness of the aggregated index of the WhatsApp messages, controlling for the pretest (see Huck & Mclean, Reference Huck and Mclean1975). We find a significant main effect of the inoculation condition on aggregated perceived manipulativeness (F(2,288) = 58.4, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.106). Specifically, the shift in manipulativeness score postintervention was significantly higher in the inoculation condition than in the control group (Mdiff = –0.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) = –0.77 to –0.39, d = 0.71), thus confirming Hypothesis 1. Figure 5 shows the violin and density plots for the pre–post difference scores between the control and the inoculation conditions. Note how there is little to no shift in the control group, while there is a significant increase in perceived mean manipulativeness for the inoculation condition. Supplementary Table S5 shows the ANCOVA results broken down per WhatsApp post.

Figure 5. Perceived manipulativeness of WhatsApp messages. Note. Violin and density plots are shown of pre–post difference scores for the manipulativeness of six WhatsApp messages (averaged).

As a robustness check, we ran a difference-in-differences (DiD) ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression on the perceived manipulativeness of the WhatsApp messages. Doing so shows a statistically significant increase in the manipulativeness rating of the WhatsApp messages for the treatment group by 0.56 points (R 2 = 0.11, F(3, 578) = 24.15, p < 0.001) compared to the control group on a seven-point Likert Scale; see Supplementary Table S7. We also conducted separate DiD analyses with control variables included (see Supplementary Table S2): age, gender, education, political ideology, racial background, employment status, marital status, trust in government, concern about the environment and views on whether the government should provide social services to the unemployed. We find significant effects for two covariates: marital status (meaning that married people are more likely to give higher manipulativeness scores for the WhatsApp messages than non-married people) and trust in government (meaning that people with higher trust in government are more likely to give higher manipulativeness scores for the WhatsApp messages), but not for political ideology, racial background, environmental concern and employment status. See Supplementary Tables S7 and S14 for a full overview.

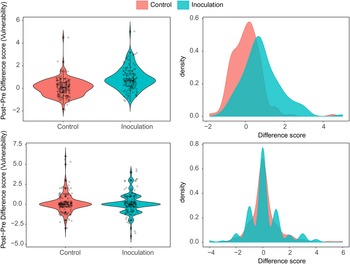

For the vignettes measure, we ran a one-way ANCOVA on the aggregated perceived vulnerability of the profile vignettes, with the aggregated pretest score as the covariate. Doing so shows a significant postintervention difference between the inoculation (M = 5.11, SD = 1.00) and control condition (M = 4.28, SD = 1.05). Here, too, we find a significant effect of the treatment condition on aggregated perceived vulnerability (F(2,288) = 73.2, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.174). Specifically, the pre–post shift in perceived vulnerability of vulnerable profile vignettes was significantly greater in the inoculation condition compared to the control group (Mdiff = –0.84, 95% CI = –1.07 to –0.60, d = 0.81), confirming Hypothesis 2. See Supplementary Table S9 for the ANCOVA results per individual vignette. Figure 6 shows the violin and density plots of the mean pre–post difference scores for the inoculation and control conditions for both the vulnerable and the non-vulnerable profile vignettes.

Figure 6. Perceived vulnerability of vulnerable and non-vulnerable profile vignettes. Note: Violin and density plots of pre–post difference scores are shown for the mean perceived vulnerability of vulnerable (top row) and non-vulnerable (bottom row) profile vignettes.

As for the vignettes containing profiles of people who were not especially vulnerable to extremist recruitment strategies, a one-way ANCOVA reveals that the difference between the inoculation (M = 2.16, SD = 1.25) and control (M = 2.34, SD =1.46) group is not statistically significant. Here, we find no significant effect for the treatment condition (F(2,288) = 0.35, p = 0.556, η 2 = 0.001); see the violin plot with the pre–post difference scores in Figure 6, which shows that the scores for both the control and inoculation conditions are distributed with a mean of approximately 0. This indicates that people who played Radicalise did not simply become more skeptical in general, but instead applied critical thinking skills in their assessment of the vulnerability to radicalization of a number of fictitious individuals; see also Supplementary Table S9. We performed several additional analyses in order to double-check these results. First, we conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the difference scores between non-vulnerable and vulnerable profile vignettes (the mean score for non-vulnerable profiles minus the mean score for vulnerable profiles per participant), which gives a significant postintervention difference between the inoculation and control group (F(2,288) = 37.80, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.086). Additionally, we ran a 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA with the type of vignette (vulnerable versus non-vulnerable) as the within-subjects factor, which gives a similar outcome for the interaction between the treatment and the type of profile vignette (F(1,579) = 32.23, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.009); see Supplementary Table S13.

As a further robustness check, we ran a DiD OLS linear regression on the perceived vulnerability of vulnerable vignettes. Doing so reveals a statistically significant increase in the vulnerability rating of the vulnerable profiles for the treatment group by 0.77 points (R 2 = 0.11, F(3,578) = 24.93, p < 0.001) compared to the control group on a seven-point Likert scale; see Supplementary Table S11. We also conducted separate DiD analyses with each control variable included. We find significant effects for employment status (meaning that partially/fully employed people are more likely to give higher vulnerability scores for vignettes than people not currently employed either full-time or part-time), but not for political ideology, racial background, environmental concern and other control variables. See Supplementary Tables S11 and S15 for a full overview.

Finally, with respect to the confidence measure, a one-way ANCOVA controlling for pre-game results shows that participants in the inoculation group became significantly more confident in their own assessment of the manipulativeness of the WhatsApp posts (M = 6.12, SD = 0.92) compared to the control group (M = 5.83, SD = 0.94; F(2,288) = 18.4, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.051), with an effect size of d = 0.41 (see Supplementary Table S8 & Supplementary Figure S1). The same effect was observed for the treatment group (M = 5.46, SD = 1.04) and control group (M = 5.32, SD = 1.18) for the vulnerable vignettes (F(2,288) = 11.5, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.033), with an effect size d = 0.45, but not for the non-vulnerable vignettes (F(2,288) = 1.42, p = 0.235, η2 = 0.003; see Supplementary Table S12 & Supplementary Figures S2 & S3). These results thus confirm Hypothesis 3.

Discussion and conclusion

For this study, we successfully developed and tested Radicalise, a game that leverages concepts from behavioral science, gamification and inoculation theory to confer psychological resistance against four key manipulation techniques that can be used by extremists in their attempts to recruit vulnerable individuals. Overall, we find that after playing the game, participants become better at assessing potentially malicious social media communications. We also find that participants’ ability to detect the factors that make people vulnerable to recruitment by extremist organizations improves significantly after gameplay. Consistent with findings in the area of online misinformation (Basol et al., Reference Basol, Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020; Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020), we also find that players’ confidence in spotting manipulation techniques as well as vulnerable individuals increased significantly compared to a control group.

The overall effect sizes reported (d = 0.71 for the WhatsApp messages and d = 0.81 for the vignettes) are medium-high to high overall (Funder & Ozer, Reference Funder and Ozer2019) and high in the context of resistance to persuasion research (Banas & Rains, Reference Banas and Rains2010; Walter & Murphy, Reference Walter and Murphy2018). We find these effects especially meaningful considering that we used a refutational-different as opposed to a refutational-same research design, in which participants were shown measures that were not present in the intervention itself (i.e., participants were trained on different items from what they were shown in the pre- and post-test; Basol et al., Reference Basol, Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020; Roozenbeek et al., Reference Roozenbeek, Maertens, McClanahan and van der Linden2020a). In addition, the intervention works approximately equally well across demographics, as we found no significant interaction effects with, for example, gender, education level, concern for the environment or political ideology (see Supplementary Tables S7, S11, S14 & S15 for the DiD OLS regression analyses with control variables included). These findings are in line with previous research on “active” inoculation interventions (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2019; Basol et al., Reference Basol, Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020; Roozenbeek et al., Reference Roozenbeek, van der Linden and Nygren2020b), and they highlight the potential of gamified interventions as “broad-spectrum” vaccines against malicious online persuasion attempts.

Having said this, we do find a significant interaction effect for two control variables: being married and having trust in government (in the sense that being married and having greater trust in government are both associated with higher manipulativeness ratings). Previous literature has shown results in line with these findings. With respect to trust in government, one study conducted in Georgia found that trust in national institutions (e.g., the parliament) was lowest among (young) individuals with a higher propensity for joining an extremist organization (such as ISIS in the case of Georgian Muslims; see Kachkachishvili & Lolashvili, Reference Kachkachishvili, Lolashvili and Zeiger2018). With respect to marital status, some literature has suggested that marriage and strong family ties could reduce the risk of radicalization among young people (Berrebi, Reference Berrebi2007; Cragin et al., Reference Cragin, Bradley, Robinson and Steinberg2015; SESRIC, 2017). For example, one study found that family ties could play a role in moderating radicalization by studying family ties among suicide bombers, who typically tend to have fewer or weaker family ties compared to other members of extremist organizations (Weinberg et al., Reference Weinberg, Pedahzur and Perliger2008). However, as we did not preregister any hypotheses about interaction effects, we caution against over-interpreting these results.

While our study did not target individuals vulnerable to radicalization specifically, future research could explore this study's findings in more detail. Although field experiments are notoriously difficult to conduct in this area, in order to further validate the effectiveness of the intervention, future work could conduct a similar experiment with participants from vulnerable populations; for example, using mobile lab units to conduct field research in hard-to-reach areas, such as refugee camps.

Furthermore, we note that, when broken down by item, two individual measures showed a nonsignificant effect that was not hypothesized (one WhatsApp message and one vignette; see Supplementary Tables S5 & S9). This can be partially attributed to the fact that although most items proved highly reliable, none of the items were psychometrically validated prior to their deployment and therefore may show some random variation. The issue may also partially be related to the difficulty of the questions presented: the two nonsignificant measures may have been worded in such a way that they were too easy to spot as manipulative, and hence displayed a ceiling effect. Further calibration and validation of the test questions may help resolve this issue.

Although this study shows positive results in how people assess the vulnerability of at-risk individuals and the manipulativeness of targeted malicious communications, we cannot ascertain whether this means that participants’ underlying beliefs have shifted, or whether the observed effects can be considered a proxy for conferring resistance against recruitment attempts by real extremist groups. We argue that the observed improvement in the post-test responses is a proxy for participants’ ability and willingness to refute manipulation attempts and identify the right vulnerability characteristics, and thus serves as a step towards developing resilience against it, in line with recent advances in boosting immunity against online misinformation (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2019; Basol et al., Reference Basol, Roozenbeek and van der Linden2020; Roozenbeek et al., Reference Roozenbeek, van der Linden and Nygren2020b). This research thus significantly advances the agenda of behavioral insights above and beyond the typical “low-hanging fruits” to tackle a complex societal issue with a scalable game-based intervention (van der Linden, Reference van der Linden2018). For example, other existing methods that have produced favorable results, such as “integrative complexity” interventions (which promote open and flexible thinking), often require over 16 contact hours using films and intense group-based activities (Liht & Savage, Reference Liht and Savage2013; Boyd-MacMillan et al., Reference Boyd-MacMillan, Campbell and Furey2016).

To highlight the policy relevance of our intervention, we recently presented our results at the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) as part of an event on preventing violent extremism, with favorable feedback from policymakers (UNITAR, 2019). The purpose of this forum was to instigate new initiatives and explore possible solutions to the prevention of violent extremism. During his keynote address, Cass Sunstein argued that, contrary to widespread understanding, violent extremism is not a product of poverty, lack of education or mental illness, but rather “a problem of social networks.” This is a testament to the importance of addressing the issue of violent extremism and radicalization via social networks, including simulated networks, as we have done in this study. Sunstein further elaborated that the use of games is an essential innovation in the field of prevention of violent extremism and, to that end, suggested adding the component of “fun” to the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT)'s renowned acronym EAST (Make it Easy, Make it Attractive, Make it Social and Make it Timely) of behavioral change techniques. An event summary report was shared internally in December 2019, detailing the proceedings of the meeting and highlighting key insights and innovations. Marco Suazo, the Head of Office of the New York United Nations Institute for Training and Research, wrote that the current research “offers the opportunity to serve difficult-to-reach audiences and operate at a large-scale, thus potentially reaching millions of people worldwide,” and that the work was “of great value to UNITAR and will help inform and develop its future policies for overcoming global challenges such as preventing violent extremism” (Suazo, 2019, personal written communication).

More generally, this research bolsters the potential for inoculation interventions as a tool to prevent online misinformation and manipulation techniques from being effective (van der Linden & Roozenbeek, Reference van der Linden, Roozenbeek, Greifenader, Jaffé, Newman and Schwarz2020). Specifically, in the context of online radicalization, inoculation interventions may be especially useful if a new extremist group rapidly gains in popularity (as was the case with ISIS in 2014–2015). We thus see much value in discussing the potential for policy implementation of inoculation interventions at both national and international levels. One important step forward is to develop a professional version of the Radicalise game, along with supplementary materials on online radicalization and inoculation interventions, to be made suitable for use in educational settings in schools, universities and the prevention of violent extremism training programs worldwide, in a variety of languages.

Future research could focus on measuring shifts in beliefs and on investigating the long-term sustainability of the inoculation effect produced by the game, which will require replicating the experiment on a larger sample and testing over multiple time intervals. Such research can also explore the decay of effects and determine whether “booster shots” are needed (Ivanov et al., Reference Ivanov, Rains, Geegan, Vos, Haarstad and Parker2017; Maertens et al., Reference Maertens, Roozenbeek, Basol and van der Linden2020) to help ensure long-term immunization against extremist radicalization. Finally, one limitation of using the Prolific platform is that we were not able to select participants based on their vulnerability to extremist recruitment. Or, in other words, the sample is not ecologically valid in terms of the intended target audience of the intervention, which may reduce the generalizability of this study's results. Future research should therefore investigate the effectiveness of gamified “active inoculation” interventions among at-risk individuals specifically, both in terms of improving people's ability to spot manipulation techniques and in terms of voluntary engagement with popular game-based interventions.

In conclusion, this work has opened up new frontiers for research on the prevention of violent extremism with a particular focus on its use of insights from behavioral sciences. It also extends the rigor that comes with using randomized controlled trials and experimental designs in the field of preventing violent extremism, which currently lacks evidence-based research and actively seeks guidance on “what works” (Fink et al., Reference Fink, Romaniuk and Barakat2013; Schmid, Reference Schmid2013; Holdaway & Simpson, Reference Holdaway and Simpson2018). As this research was to an extent exploratory (but preregistered), and as we did not target the intervention specifically at at-risk individuals, we see the results presented here as highly encouraging but preliminary. Nonetheless, given the ethical and real-world challenges that come with studying at-risk populations, we find it encouraging that both outcome variables show significant and large positive effects. Considering the fact that people who are vulnerable to radicalization may appear well-integrated and “normal” (McGilloway et al., Reference McGilloway, Ghosh and Bhui2015), and taking into account the diversity of the backgrounds of radicalized individuals (Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2018), we also see value in evidence-based interventions that are useful for the general population. With this in mind, future research can further validate this approach at scale and engender real-world impact against violent extremism.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.60.

Author contributions

Nabil Saleh and Jon Roozenbeek contributed equally to this study.

Conflicts of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.