A. Introduction

Do states take court decisions into account when formulating policies? If so, how and through what mechanisms do they process new judicial input and make policies in response to them? It is not always clear what drives states to adopt a particular policy instead of an alternative. It is especially not clear how states get influenced by new judicial inputs when doing so. To what extent are the pronouncements on the state of the law—issued by international courts—a factor in states’ decision making? We approach this question in the field of maritime delimitation—a process of delineating neighboring states’ respective zones of maritime jurisdiction. In particular, we assess how states formulate and modify their policies on continental shelf delimitation—a maritime area whose delimitation rule was shaped by the international courts’ involvement in the early, critical stages of its development.Footnote 1

The domain of maritime boundary-making provides a fertile ground for studying how court decisions are registered by states for three reasons. First, it is a novel field of state action with a tractable history. It is only in the past seventy years that we have seen a considerable increase in the extent of state jurisdiction in the sea, beginning with the Truman Proclamation of 1945. Second, international law has been important in the inception and subsequent development of extended state jurisdiction in the sea. Most notably, the 1982 United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), considered to be “a constitution for the oceans,”Footnote 2 emerged as the product of a long multilateral treatymaking process aimed at formulating comprehensive rules for state rights and obligations in the sea. Third, there have been frequent interventions by courts and tribunals that were asked to resolve disputes and interpret the state of the law. As such, the law was developed as much by courts as it was through multilateral efforts. This development by the courts also meant that the law of the sea took shape in an incremental fashion through occasional but significant interventions of judicial bodies. For these reasons, the field of maritime boundary-making presents a unique testing ground for studying states’ uptake of new judicial inputs.

This article pursues two goals. First, we intend to establish the extent to which states are influenced by court decisions in formulating their policies on continental shelf delimitation. To do so, we look at how states process new legal inputs provided by international courts to formulate and update their delimitation policies. The three possible policies are based on three distinct methods: Equidistance, modified equidistance, and non-equidistance. Equidistance amounts to dividing a maritime zone by a line that is equally distant from the coasts of the concerned states. Modified equidistance involves taking equidistance as a basis and adjusting it in a way that remarkably departs from strict equidistance. Non-equidistance, for its part, is not based on equidistance and instead uses one or more of different methods available—often in following what is called equitable principles.Footnote 3

Second, we attempt to distill different mechanisms through which states take court decisions into account. Existing research traditions provide varying explanations of the processes by which states make and update policies. On the one hand, rationalist explanations suggest that states adopt and change policies in a self-interested way to maximize their expected utility.Footnote 4 On the other hand, many have suggested that such classical approaches fall short of capturing the motivations and considerations of states and individuals involved. Behavioral approaches, in particular, emphasize that individual and group decision making may be subject to cognitive limitations and biases.Footnote 5 They would thus take issue with the expectation that states are able to identify and pursue strategies to maximize their expected utility free from heuristics and other cognitive biases.

Based on these two families of explanations, we lay out hypotheses and observable implications regarding how states register rules and principles provided by new court rulings. We test some of these expectations derived from these approaches in the field of states’ maritime delimitation preferences. To do so, we use a data set of state positions on continental shelf delimitation. To examine how state practice evolves in parallel to court rulings, we use change point detection techniques, causal impact analysis, and semi-structured expert interviews.Footnote 6 We asked our interviewees about state motivations for settling on certain delimitation methods and the relative weight of various considerations that surround policymaking in this regard. When relevant, we also asked them about the internal decision-making process of policy uptake and update. This mixed-method approach intends to show how the court interventions at various points in time have influenced the state positions.

Our findings suggests that—at least some—states do take court judgments into consideration when formulating their positions. We do not, however, know how rational they are in doing so. While our quantitative and qualitative analyses have shown evidence of states changing or keeping policies in response to court judgments, we are unable to distinguish the influence of rational and behavioral drivers. The major issue is our level of analysis and our large-N approach. The most straightforward and reliable way of tracing state policies is by looking at declared positions that are often observed at the state level. Yet, this does not allow us to ascertain the internal workings of the decision-making process in each state. While our interviews provide additional insights in this regard, they tend to “rationalize” observed state behavior retrospectively—our interlocutors on the whole portrayed state behavior as being in that state’s interest. A behavioral approach requires finer-grained data that traces individual biases and how they aggregate at the group level. This is best done through experiments, rather than large-N analysis or expert interviews. Such data is difficult to collect due to access restrictions and the opacity of policymaking processes.

Moreover, we have reasons to believe that, in the context of maritime delimitation, behavioral insights are not as illuminating as they could be in other contexts. First, conclusions from existing empirical studies on bias may not extend to groups that are actually involved in high-level policy formulation. Policymaking groups are likely to be different than the subjects of experiments that were involved in behavioral studies.Footnote 7 Thus, it would be hard to extrapolate from such experiments to settings where many actors with expertise are found. Higher stakes may also work to erode the influence of bias by increasing the number of individuals involved as well as the varied expertise they may bring to the table. Second, the nature of some policy formulation processes, such as policies about maritime delimitation, requires tailor-made calculations based on geographic considerations, following procedures that hold quick decision making in check. Such situations are more suitable for thinking slow Footnote 8 with routine input from various technical bodies.

B. Determinants of State Policies and the Role of Law

Maritime delimitation is the process by which neighboring states draw their common boundaries. States formulate policies on how their boundaries should be delimited in a unilateral manner, but the delimitation itself is a bilateral exercise. The bilateral nature of maritime delimitation poses certain constraints on the boundaries that states can realistically hope to draw. One of the constraints is the necessity of finding convincing justifications for the boundaries and delimitation methods that states propose.Footnote 9 International law plays an important role in this regard. As extended maritime jurisdiction is a new legal creation, state policies declaring sovereignty and sovereign rights in the sea must often be motivated with appeals to law.Footnote 10 States can justify their claims using treaty provisions, state practice and custom, and decisions by international courts and tribunals. New policies may be made as the law evolves. Studying how states formulate their policies in the field of maritime delimitation is essential to understanding how state officials recognize, process, and argue available rules and interpretations in this domain.

A unique ground to test how states take new law into account when formulating their policies is states’ reaction to new judicial inputs. It is generally agreed that international courts and tribunals make and clarify the law “[b]y authoritatively stating what the law is.”Footnote 11 It is also suggested that their influence goes beyond the specific parties to a dispute and extends to the rest of the actors in a legal system. Adjudication helps states come to similar views about what the law is by making their solutions stand out as focal for all parties and “sharpening common understandings as to what formal and informal rules require.”Footnote 12 Scholars have demonstrated that institutions such as the International Court of Justice, the European Court of Justice, or the European Court of Human Rights play a fundamental role in shaping the law and coordinating state policies.Footnote 13

In what follows, we discuss how states process and act on judicial input from the perspectives of rational choice and behavioral explanations. We consider how these approaches differ in their answers to the questions of whether states adopt and update policies in light of court rulings, and through what mechanisms states do so.

C. How States Take Legal Change into Account: Rationalist and Behavioral Expectations

A traditional rational choice approach comes with a certain number of assumptions that can be broadly expressed as follows: States pursue their self-interest and, given a set of fixed preferences, they respond to incentives to maximize their expected utility.Footnote 14 The adoption and update of policies in keeping with rational choice assumptions could thus involve states weighing each alternative policy and pursuing the one that promises the greatest gain. Judicial input is one of the ways in which new alternatives become available to states. Court decisions that deviate from established law and practice provide states new rules and interpretations which may enable them to adopt a policy more favorable to them compared to the status quo.Footnote 15

Regarding the question of whether states adopt and update their policies in light of court rulings, rational choice scholars are likely to respond yes. As court decisions may alter the set of available rules and interpretations, states would reconsider their policies taking note of newly available rules and interpretations.Footnote 16 Over time, we can see a move towards a newly promoted rule as it is adopted by more and more states that benefit from it. As for the mechanism by which states update their policies, rational choice explanations would suggest that officials responsible for setting the course of a state’s maritime boundary policy would assess new court decisions to determine if they provide favorable alternatives which can make them better off. A good strategy for states would be to evaluate available legal rules and interpretations, and identify the one that provides the greatest benefit to the state.Footnote 17 Building upon such favorable rules and interpretations, they may make a policy and try to get as close to that policy as possible when negotiating with the neighboring state.Footnote 18 In short, if a state can hope to get a better maritime boundary using a new interpretation proposed by a court or a tribunal, it will align itself with that interpretation and change its policy using the judicial decision as the justification. We call this rational updating.

Behavioralist explanations do not give a straightforward answer to either question. On the one hand, behavioral insights about how actors tend to put more value on what they already have can lead us to expect that states will be reluctant to adopt new policies, be they potentially more beneficial to them than their existing policies.Footnote 19 This form of status quo bias may make states both reluctant to express a preference for a rule or interpretation in the first place and insensitive to new judicial input. On the other hand, behavioral findings highlighting actors’ susceptibility to be influenced by events that more readily come to mind can also lead us to expect that states would adopt policies and change them in line with the latest court ruling. This could be the product of some form of availability bias according to which the most recent expression on the state of the law is more readily available to be adopted.Footnote 20

It should be clear that rational updating, on the one hand, and the status quo and availability biases, on the other hand, operate through distinct mechanisms. From the point of view of empirical enquiry, the problem is that these three mechanisms may well be responsible for similar empirical patterns at the state level—that is, looking at expressed state policies. All three mechanisms have observable implications as to the sensitivity of states to court rulings and about what a state would do in response to a court ruling presenting them with a potentially more favorable rule or interpretation as basis for their policies. These expectations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Expectations of state sensitivity and behavior in reaction to favorable new judicial input

As Table 1 shows, the same expected policy may be arrived at through different mechanisms. For instance, if a state changes its policy after a court ruling aligning itself with the new rules and interpretations endorsed in that ruling, it would not be easy to tell if they are doing so because of the availability bias—being affected by closeness in time—or rather after a process of rational updating—seeing that the new policy supports a better outcome. Similarly, if a state does not change its policy after a court ruling, we cannot tell if this is due to the status quo bias or the fact that the new principle does not make the state better off than earlier principles. The task then becomes that of distinguishing between them empirically, which we take up in the analysis section.

D. Jurisprudential Trends and Cut-off Points in the Field of Maritime Delimitation

In this section, our goal is to identify a number of influential judgments that have arguably shaped the rules around maritime delimitation by providing novel judicial input. In doing so, we mainly rely on the existing literature supported by additional quantitative and qualitative evidence.Footnote 21 We have coded the delimitation rule promoted by each judicial decision to look for regularities.Footnote 22 Moreover, we have asked our interviewees whether they saw any important case that could serve as a jurisprudential cut-off point.Footnote 23 Taken together, this analysis allows us to show the potential of some influential rulings to “create trends” and to shape state policies.Footnote 24

When it comes to methods of delimitation, equidistance method was the earliest one to be codified. Article 6 of the 1958 Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf (CSC) established that “in the absence of agreement, and unless another boundary line is justified by special circumstances, the boundary is the median line, every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured.” Subsequently, the equidistance principle began to spread in state practice as one of the most preferred methods for continental shelf delimitation. As Leonard Legault and Blair Hankey note, “until the 1969 judgment in the North Sea Continental Shelf cases, most policy-makers assumed the existence of a binding legal presumption in favor of the equidistance method, whether under treaty law or customary law.”Footnote 25

In the 1969 North Sea Continental Shelf judgment, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) pronounced that the principle of equidistance is not customFootnote 26 and instead ruled that “delimitation is to be effected by agreement in accordance with equitable principles, and taking account of all the relevant circumstances.”Footnote 27 In so doing, the Court opened the possibility of two different approaches to delimitation: “[E]quidistance/special circumstances” or “equitable principles/relevant circumstances.” More importantly, this ruling created an important rift between two groups of states on the question of the delimitation method. During the Third United Nations Conference for the Law of the Sea (1973–1982), these camps pushed for the method that suited their interests the best. As a result, the drafters introduced a vague formula under Article 74(1) and 83(1) of the UNCLOS,Footnote 28 providing that delimitation is to be “effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution.”Footnote 29 The drafters carefully avoided the controversial terms such as equidistance, equitable principles, special circumstances, or relevant circumstances. Yet, at the same time, they provided little guidance as to how to delimit the boundaries of continental shelves. As the UNCLOS was being adopted in 1982, the ICJ delivered its Tunisia/Libya, Gulf of Maine, and Libya/Malta decisions.Footnote 30 These three judgments continued to emphasize equitable principles while portraying equidistance as non-customary and as merely one of many options.

This changed with the 1993 Jan Mayen judgment. In this case, the ICJ pronounced that “[p]rima facie, a median line delimitation between opposite coasts results in general in an equitable solution.”Footnote 31 This judgment signaled the ICJ’s change of heart concerning the equidistance principle. The origins of what we describe as the modified equidistance method—namely, starting with equidistance line and adjusting as necessary to reach an equitable outcome—go back to the Jan Mayen ruling. The ICJ reiterated this position in the 2001 Qatar v. Bahrain judgment.Footnote 32 It described drawing a provisional line based on the equidistance principle and then adjusting it if special circumstances so require as “the most logical and widely practiced approach.”Footnote 33 This reasoning presented here was subsequently confirmed in Nicaragua v. Honduras, Footnote 34 and further systematized as the “three-stage method” in the 2009 Black Sea case.Footnote 35 The International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) endorsed this three-stage method in Bay of Bengal in 2012,Footnote 36 and the ICJ reiterated it in Peru v. Chile in 2014.Footnote 37

As seen in this brief historical narrative, the ICJ, joined by other courts and tribunals, devised and advocated a single method—that is, modified equidistance—starting from 1993.Footnote 38 Table 2 below presents the number of times each delimitation method was endorsed by the courts and tribunals in the period under study.Footnote 39

Table 2. The delimitation methods used by the international tribunals

In the pre-1993 period, the courts and tribunals tended to predominantly favor non-equidistance and relied on modified equidistance only twice. While none of the rulings depended on the equidistance principle, non-equidistance-based delimitation methods seemed to fall from the tribunals’ favor after 1993. Indeed, in this period, nearly all tribunal decisions used modified equidistance while only one relied on non-equidistance. What this picture tells us is that, after 1993, the international courts and tribunals favored modified equidistance and attempted to rally states around this method, which promised to infuse predictability (equidistance) and flexibility (equity).Footnote 40 Our interviews revealed that there appears to be agreement within academic circles that the case law now is quite settled on the delimitation method.Footnote 41

If court pronouncements were registered through processes involving cognitive biases and heuristics, we would either expect stability—due to the status quo bias—or moves towards non-equidistance after 1969 and modified equidistance after 1993—due to the availability bias. Rationalists, on the other hand, would expect that switches to non-equidistance after 1969 and modified equidistance after 1993 would only occur for states that are made better off by those methods. For instance, if equidistance is the method that is the most advantageous for a state, it is rational for that state to stick to it, regardless of new court decisions.

E. Data and Method

To assess our expectations, we examine how state preferences around continental shelf delimitation changed over time. We identify state preferences by looking at domestic legislation, unilateral declarations, bilateral delimitation treaties, as well as any other sources that may reflect a preference for a particular delimitation method. We then carry out a series of analyses to determine whether the degree of popularity of particular methods was sensitive to new judicial input. As a first step, we use change-point detection techniques to identify potential cut-off points that marked a significant change in the popularity of these methods. We then complement our analysis with evidence from causal impact analysis, interviews, and illustrative cases.

To test our expectations about state policymaking in response to judicial rulings, we use a data set recording state positions on the appropriate continental shelf delimitation method. For classification of state positions, our data set relies on Leonard Legault and Blair Hankey, who distinguish between the following three categories: (1) “Equidistance Strict or Simplified,” (2) “Modified Equidistance,” and (3) “Non-Equidistance.”Footnote 42 The data set is created through manual labeling of a corpus consisting of documents expressing maritime boundary delimitation preferences, including acts like treaties and unilateral declarations. When the text was not clear, coders used external sources such as maps available on the Sovereign Limits database as well as the analysis found in the International Maritime Boundaries volumes. Last, but not least, for the period up until 1993, the coders also verified some of the codes by using Legault and Hankey’s coding scheme as a reference.

The data set resorts to two additional sources to determine policy changes. First, it uses memorials states submitted in the course of international adjudication, especially when they contain information on states’ general continental shelf delimitation policies, rather than their opinion of the disputed boundaries segments at issue. Second, the data set also incorporates multilateral treaty ratification information when the treaty concerned endorses a specific method of delimitation. In the context of continental shelf delimitation, only the 1958 CSC meets this criterion as it is the only multilateral treaty that includes a default method for maritime delimitation: equidistance.Footnote 43 Therefore, states ratifying the 1958 CSC are coded as preferring equidistance beginning from the year of ratification until they adopt a new policy.

F. Analysis

We begin by first presenting the distribution of state policies over time, focusing on states that have expressed a preference for one of the three policies defined above (equidistance, modified equidistance, non-equidistance). Figure 1 below shows the proportion of expressed preferences belonging to each of the three categories for every year between 1958 and 2019. In years without a policy document, the state's policy is its most recently adopted policy.Footnote 44

Figure 1. Evolution of state policies regarding the continental shelf delimitation rule among States having expressed a preference for equidistance, modified equidistance, and non-equidistance (1958–2019).

As we can see, an initial move towards a consensus around strict or simplified equidistance in the early 1960s unraveled from the early 1970s onwards. At this point, the proportion of states preferring strict or simplified equidistance stayed at slightly greater than fifty percent. Non-equidistance began increasing in the late 1960s and early 1970s, whereas the popularity of modified equidistance rose from the mid 1990s onwards. Moreover, we observe that since 1998 the relative popularity of each method seems to have stabilized and there has been no tendency toward a convergence around one single method.

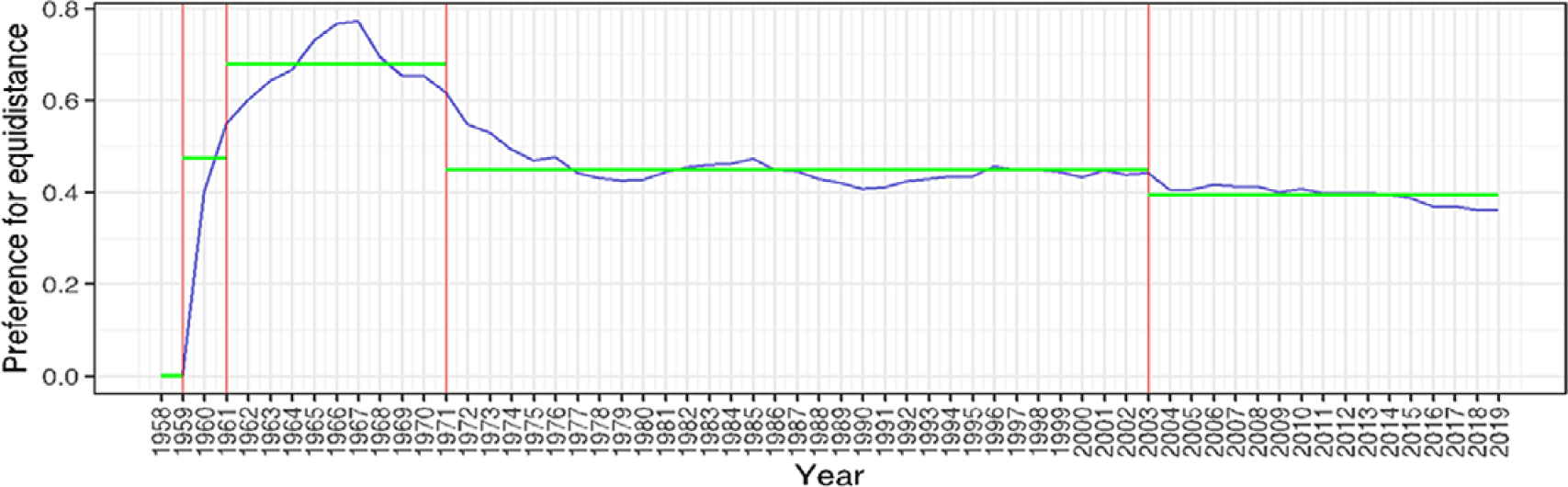

Is this picture consistent with the expectation that states are influenced by court decisions? If this is the case, we would expect a move away from equidistance after 1969—at least for states operating with rational updating or the availability bias. A simple way of testing this would be to examine the evolution of the popularity of strict and simplified equidistance. We use a change point analysis algorithm to identify points around which there was a significant change in its popularity.Footnote 45 This algorithm identifies significant changes in the proportion of preferences expressed in favor of strict or simplified equidistance. We choose the optimal number of change points based on the jumps in the reduction of sum of squared residuals.Footnote 46 For strict or simplified equidistance, this gives us four change points at the following years: 1959, 1961, 1971, and 2003, dividing the time between 1958 and 2019 into five periods. These results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Change points in the evolution of the proportion of states opting for strict or simplified equidistance in continental shelf delimitation.

Around each of these years there is a clear change in the proportion of preferences for strict or simplified equidistance. What can be seen is that this method reached its peak popularity a few years before the third change point, 1971. The upward trend seems to have been broken some years before that. It could be that the ICJ’s North Sea ruling, which preceded the change point in 1971 by two years, was a driver of the decrease in the popularity of strict and simplified equidistance. This would be consistent with both rational choice explanations, whereby states expected greater returns from non-equidistance and adopted it after 1969, as well as behavioral explanations based on the availability bias—with the most recent endorsement influences states making policies post-1969.

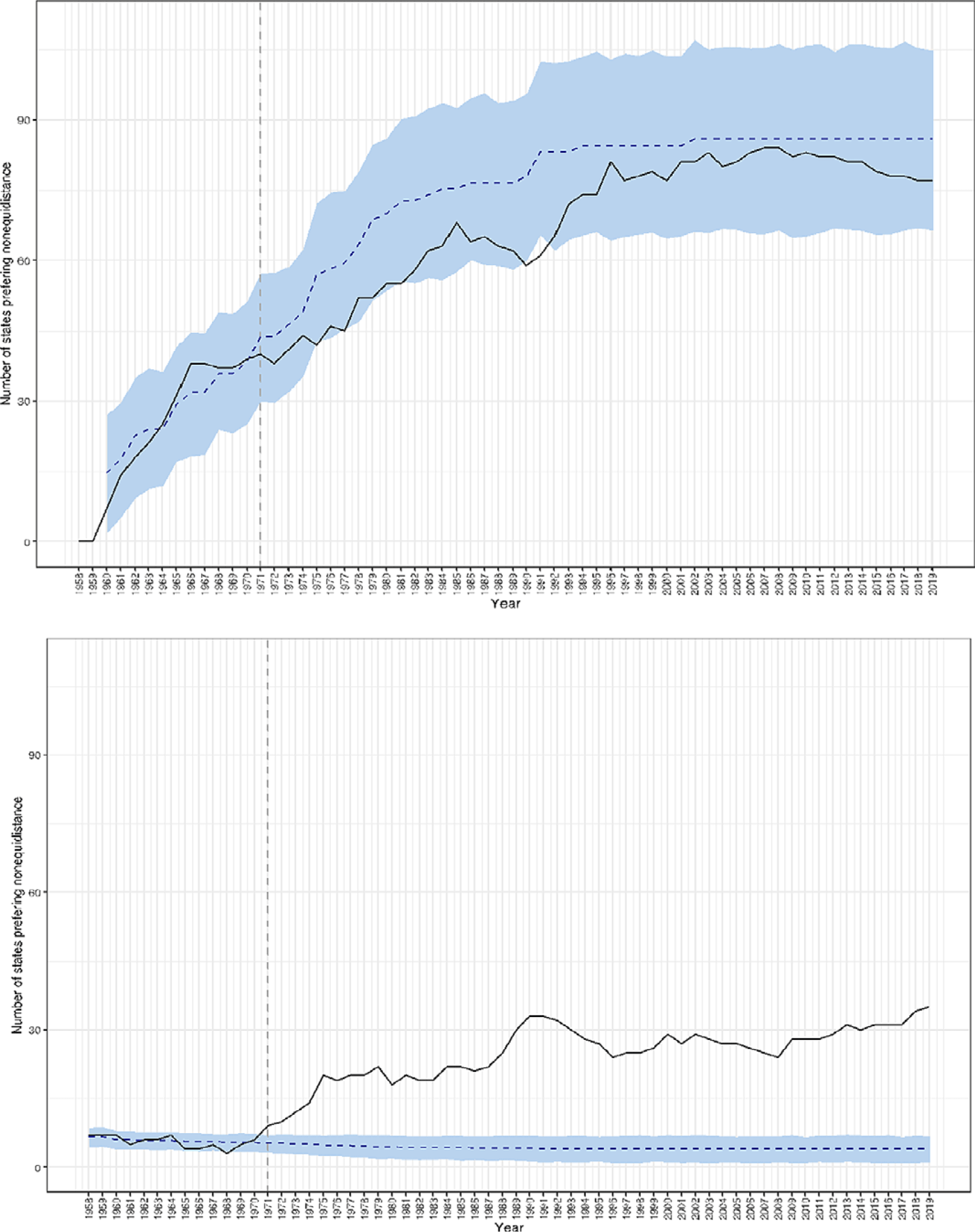

The seemingly big jumps and identified change points near the very beginning of the observation period are because the number of cases were low and our analysis uses proportions. Due to the sensitivity of proportions, and as an additional piece of evidence, it will be illustrative to show the evolution of the number of countries over time with equidistance as a preference. We do this in Figure 3. For comparison, we include the evolution of non-equidistance as well. In both cases, 1971 was proposed as a year in which an intervention took place. We simulated the evolution of the number of countries adhering to a certain policy by indexing it to the number of states in existence each year. The dotted lines, then, were created based on the assumption that there were no differences between the pre-1971 and post-1971 periods; that the relation between number of states in total and number of states preferring equidistance or non-equidistance were identical in both periods. This test allows us to ask the counterfactual question: If the trends before 1971 were to continue, how would the distribution of state preferences look like?

Figure 3. Causal impact analysis of the year 1971 on the number of states with equidistance (left) or non-equidistance (right) as their preferred policies.

The counterfactual evolution is shown as dotted lines, whereas the actual state practice is portrayed as the continuous line. These results show us that the divergence does not result from the ICJ making equidistance less popular in absolute terms; rather, it is due to the ICJ’s raising non-equidistance as a justifiable alternative to equidistance. For equidistance, if there was no intervention in 1971, we would have expected to see only a few more states favoring it than what we actually observed. Although the intervention does not create a statistically significant change in the number of states adopting equidistance in absolute terms, the actual number is lower than what could have been. The effect is clear in the case of non-equidistance. Without the intervention around the years 1969–71, we would have expected only about four states to have non-equidistance as the policy as of 2019, as opposed to the twenty-five states that actually have it as their preferred policy in that year.

What explanations can be responsible for these patterns and how much can be attributed to court decisions? In Figure 4 we present the evolution of policy preferences in four snapshots as the distribution of policies stood in 1958—beginning of the data set—1969—North Sea Continental Shelf—1993—Jan Mayen—and 2019—end year of the observation period.

Figure 4. Transfers across policy preferences from 1958 to 2019, with snapshots of the distribution of policies in selected years marked by landmark ICJ decisions of 1969 and 1993.

Two observations can be drawn from the stickiness of the policies and the relative attractiveness of each policy for the adherents of others as well as for undecided states. First, most states having adopted equidistance seem to remain in favor of that policy. The status quo bias may be at play for some of them, although it may also be that equidistance promises them the greatest expected utility. Non-equidistance also appears sticky from 1969 onwards. Modified equidistance appears to be more volatile until 1993 but manages to keep its adherents thereafter. In terms of attractiveness, we note that policies promoted by the Court in 1969 and 1993 attract many states which had different policies prior to those years. For instance, as of 1993, non-equidistance had attracted sixteen states which formerly favored equidistance or modified equidistance; and between 1993 and 2019, modified equidistance attracted seventeen states that had favored one of the other two methods in the prior period.

We note that most of the flows do not result from policy switches between the three methods. Instead, undecided states (“Unknown”) and those which were not yet part of the state system but joined it later (the “Unobserved” category) contribute most of the transfers to the three policies. It is interesting to observe that most of the flows from these two categories go towards equidistance in all the time periods. This is some evidence against status quo bias, as states without policies appear eager to adopt policies, and those with established policies do not hesitate to change them, often going against judicial input.

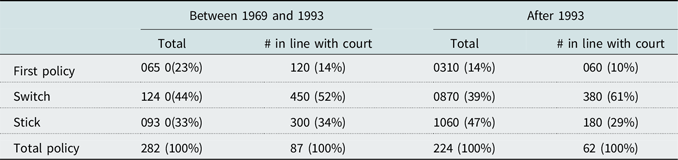

Table 3 gives a breakdown of state policies in the two time periods. For each period, we show the number of policies that favor the delimitation rule promoted by the Court: non-equidistance for the period between 1969 and 1993 and modified equidistance for the period between 1993 and 2019. To illustrate, if a state with no prior expressed policy preference, employed non-equidistance-based methods in 1975, this is counted as “first policy in line with [what the] court [promotes].” We count a state as “switch in line with court” if that state had previously expressed preference for another policy—equidistance or modified equidistance—and then switched to non-equidistance in 1975. We identify the state as “stick in line with court” if the state already favored non-equidistance in that year.

Table 3. State policies in different time periods according to whether they are in line with rules and interpretations provided by new judicial input

As it can be seen, there is a variety of policy choices in response to court rulings. The most striking finding is that behavior in line with the ICJ’s endorsements is limited. Only thirty-one percent of policies are in line with the method endorsed by the Court before 1993, and the number is slightly lower for the period after (twenty-seven percent). This casts doubt on the idea that courts may have a generalized effect on harmonizing state policies. Moreover, policy choices show a lot of variability throughout the two periods, while they appear to become stickier in the second period. The high popularity of switch also suggests that the status quo bias is not a restraining factor for state behavior to a noticeable extent, as Figure 4 has already indicated.

Focusing on behavior in line with court rulings, it appears that switching to the method endorsed by the ICJ has the biggest share (fifty-two percent in the first period and sixty-one percent in the second). It is surprising that states without prior policies do not necessarily adopt policies that are promoted by the Court. This suggests that undecided states do not suffer at large from the availability bias. Despite these suggestive results, we cannot say much about the conditions under which cognitive biases operate as opposed to picking the policy that is the most beneficial for them. We turn to this problem next.

G. Can We Disentangle the Motivations Behind State Policies?

When it comes to the issue of distinguishing between policy processes effectuated in line with rationality and those subject to cognitive biases on the state level, we note that there are serious overlaps between the observable implications. As a result, it is not clear what motivates states to change policies or stick to them. For example, a state that switches from equidistance to non-equidistance after 1969 may be doing so out of the belief that it is the most appropriate rule for being the one most recently promoted—availability bias. But it is equally likely that that state is made better off by non-equidistance, and rationally seizes the opportunity to switch to it when the Court makes it available—rational updating.

Indeed, state policies may be influenced by a number of factors whose relative importance is not always easy to gauge and disentangle quantitatively. The legal scholars and experts that we have interviewed provided some insights into this matter. Several of them confirmed that switching positions is not necessarily a quick decision—instead, it often comes as a result of a long process in the course of which states weigh different options.Footnote 47 Some also emphasized that switching positions may carry reputational costs.Footnote 48 Court rulings play an important role, here, pointing out to states the range of legally valid arguments and reducing the reputational costs of switching positions.Footnote 49 However, our interviewees also cautioned that national interest is certainly more influential than states’ willingness to adopt their position in accordance with judicial decisions and that court rulings may simply be used to justify the policies states formulated primarily based on their self-interest.Footnote 50

In some cases, we find that states often switch policies, at times going against jurisprudential trends. For example, Honduras showed great flexibility when it comes to formulating its policies on continental shelf delimitation methods. Honduras relied on a non-equidistance-based method for its 1986 bilateral treaty with Colombia,Footnote 51 modified equidistance for its treaty with the United Kingdom concluded in 2001,Footnote 52 equidistance for the 2005 treaty with Mexico,Footnote 53 and then modified equidistance again in the 2012 treaty with Cuba.Footnote 54 In a similar vein, Australia is a country that has adopted various different policies throughout the course of its boundary-making history. Australia relied on strict or slightly modified equidistance in its 1971 and 1973 treaties with Indonesia,Footnote 55 its 1982 treaty with France,Footnote 56 its 1988 treaty with the Solomon Islands,Footnote 57 and its 2004 treaty with New Zealand.Footnote 58 Nonetheless, Australia favored a non-equidistance-based method for its 1972 agreement with Indonesia, and its 2018 agreement with Timor-Leste.Footnote 59 It is important to note that this changed policy brought Australia to an advantageous position and allowed it to increase its control over the natural resources in the disputed areas.Footnote 60 At least for the case of Australia, we may be dealing with a state that goes from method to method depending on the neighboring state as well as the specific boundary segment in question.

In other cases, there may well be a status quo bias, but it is very difficult to rule out the possibility that the state sticks to a policy out of rational interest instead of attachment to the status quo. Kenya has had a consistent preference for non-equidistance-based methods, as it is evident in its 2009 treaty with Tanzania,Footnote 61 and its arguments in its case against Somalia before the ICJ.Footnote 62 In supporting its position, Kenya relies on mostly early judicial rulings which endorsed non-equidistance, such as North Sea Continental Shelf and Nicaragua v. Honduras, despite the fact that the most recent jurisprudential trends pointed towards modified equidistance. For Kenya, equidistance clearly leads to a suboptimal outcome due to its coastal geography, which makes it likely that there is more than simple status quo bias in play in Kenya’s insistence on non-equidistance.

As a final discussion, we consider two questions. First, why are we not able to confidently detect cognitive biases in the adoption and update of boundary policies? Second, to what extent can behavioral approaches be suited to the study of particular processes involved in the determination of maritime boundary delimitation policies?

Regarding the first question, our level of analysis is the main factor complicating any careful study that would be able to detect cognitive biases. A study focusing on a smaller set of cases but carefully mapping out the actors involved in decision-making as well as tracing the process by which policies are formulated would be more appropriate for this purpose. However, these individuals are sometimes hard to get access to and their biases hard to study. This is partly because many of them are high-level experts. While we may have reasons to believe that experts decide more rationally than people that are often subject to experiments, this does not need to be the case. Experimental evidence on how groups of experts make decisions would be hard to collect, yet other ways of getting at it indirectly can be explored.Footnote 63 Until such evidence is collected, however, it would be hard to extrapolate and test behavioral insights to make sense of state positions when too many actors with varying expertise are potentially involved in these processes.

Interviewing some of these experts involved in decision-making has proven to be insightful without giving us the tools of distinguishing between rationalist and behavioral modes of policy making. This is partly because our interviewees tended to have rational, or rationalizing, explanations of state choices. To be sure, our interlocutors may, themselves, have biases and rationalize the process which they were part of. This is a risk to be considered. However, this also calls for reconsidering the appropriateness of interviews, as well as large-N studies, in carrying out behavioral analyses. Such analyses might be best suited for experimental settings, where the cognitive biases of individuals can be detected using specific treatments.

Regarding the second question, there are various issue area characteristics that further complicate a behavioral approach to studying maritime boundary policies. Our interlocutors all emphasized that state interests are the primary drivers of state policies in the field of maritime delimitation.Footnote 64 Some described maritime delimitation as “not legal or technical, but a political exercise,” and that “law is used selectively to provide arguments for solutions in line with national interest.”Footnote 65 The high-stakes nature of this exercise and the involvement of experts could explain why rational calculations may prevail over cognitive biases.

Moreover, the policies around continental shelf boundary making may require tailored calculations.Footnote 66 This is because, in addition to the technical nature of the exercise, geographical features and coastal configuration necessitate customized solutions rather than ready-made ones. Such situations are more suitable for thinking slow and in groups of experts.Footnote 67 It is for these reasons that behavioral concepts might have a limited explanatory power in the context of this field and others that carry similar characteristics.

H. Conclusion

In this article we have asked two related questions: Do states take court decisions into consideration when formulating or updating their policies regarding continental shelf delimitation, and how and through what mechanisms do court decisions influence state behavior? To treat these questions, we have drawn on rational choice and behavioral insights. While rational choice explanations would suggest that states adopt and change policies in line with their self-interest and maximizing their expected utility; behavioral approaches would question whether states are able to identify and pursue their self-interest free from shortcuts, heuristics, and other cognitive biases. We engage with these two alternative approaches by looking at how states process new legal inputs provided by international courts to formulate and update their policies regarding continental shelf delimitation.

Our large-N analysis and the insights we gathered from interviews show that states are influenced by court rulings to a limited extent. However, we are unable to arrive to any conclusive findings about the mechanisms through which court rulings may influence state policies. We find that it is difficult to distinguish the influence of our alternative explanations and explain why this may be the case in this, and related, contexts. The major issue is that policymaking is studied at the state level, while a behavioral approach would require finer-grained data tracing individual biases and how they aggregate at the group level. Such data is difficult to collect, and conclusions from existing empirical studies may not extend to groups that are actually involved in policy formulation.

We also discussed why behavioralism might not necessarily be an important part of the explanation in some policy areas, such as maritime boundary making. First, high stakes may work to erode the influence of bias by increasing the number of individuals involved as well as the varied expertise they may bring to the table. Second, the nature of some policy formulation processes, such as maritime delimitation, requires tailor-made calculations following established methods and procedures that hold quick decision-making in check.

While our mixed-method analysis may not allow us to pinpoint what motivates states to take judicial input into consideration and to disentangle the rationalist or behavioral reasons in this regard, they point us to useful directions for future research. For example, our interviews revealed that legal scholars are often involved in the process of policy making. To be sure, the involvement of legal scholars in public policy may vary from state to state. Given a new court ruling or a treaty, scholars may persuade others that the law has changed in a way that is more favorable to the state than the status quo.Footnote 68 A study of the mechanisms by which decisions are made on questions of international law should thus include legal experts. Such studies should also be carried out in an experimental setting in order to check the potential biases that legal scholars may bring to the table when they are involved in policy processes. Future research could also compare the explanatory power of behavioral insights to explain policy processes in high-stake and low-stake policy environments to test our preliminary finding about the potentially smaller role for cognitive bias in the former.

Annex I

Table 4. Judgments and awards on continental shelf delimitation

Annex II

Table 5. List of Interviewees