Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disorder worldwide( Reference Hashimoto, Taniai and Tokushige 1 ). The only proven treatment strategy for disease management is lifestyle modification and weight loss( Reference Ghaemi, Taleban and Hekmatdoost 2 ), which is not applicable to patients with low or normal BMI. To our knowledge, there is no clinical trial on lean patients with NAFLD( Reference Vos, Moreno and Nagy 3 ).

Probiotics are live bacteria that provide beneficial effects by modulating the gut microbiota( Reference Eckburg, Bik and Bernstein 4 , Reference Fanaro, Chierici and Guerrini 5 ), which results in reduction of pathogenic bacteria, enhancement of the gut barrier integrity, modulation of the immune system( Reference Eckburg, Bik and Bernstein 4 , Reference Mahowald, Rey and Seedorf 6 ) and finally inhibition of inflammation, especially in the liver because of its anatomical link to the intestine( Reference Eckburg, Bik and Bernstein 4 , Reference Mahowald, Rey and Seedorf 6 , Reference McCarthy, O’mahony and O’callaghan 7 ). Prebiotics are fermentable foods that can induce specific changes in the composition and/or activity of the gastrointestinal microbiota and provide the optimal environment for growth and activity of probiotics( Reference Lim, Ferguson and Tannock 8 ). Synbiotics are the combination of probiotics and prebiotics, which are more effective than probiotics or prebiotics alone in modulating the gut microbiota( Reference Saulnier, Gibson and Kolida 9 ).

Recently, we have shown that synbiotic supplementation plus lifestyle modification is significantly more effective than lifestyle modification alone in the treatment of NAFLD in overweight and obese patients( Reference Eslamparast, Poustchi and Zamani 10 ). On the other hand, Velayudham et al.( Reference Velayudham, Dolganiuc and Ellis 11 ) have reported the beneficial effects of probiotics on hepatic fibrosis in a cholin–methionin-deficient model of NAFLD, which is a non-obese model of the disease. Thus, we hypothesised that synbiotic supplementation might be effective in the management of lean patients with NAFLD. To evaluate this hypothesis, we designed this randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial, as well as to assess whether supplementation with synbiotics is effective in treatment of lean patients with NAFLD, while addressing some mechanisms of its action.

Methods

The details of the study protocol have been explained previously( Reference Mofidi, Yari, Poustchi and Merat 12 ). In brief, patients were identified and recruited from a referral centre for FibroScan examination (Echosense). The diagnosis of NAFLD was established according to the presence of steatosis with controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) score of >263, associated with elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >60 U/l for 6 months before the study and at the time of randomisation. Patients with NAFLD who were 18 years or older, with BMI≤25, lack of history of alcohol consumption and no evidence of any other acute and chronic disorders of the liver (hepatitis B, C, etc.), biliary disease, autoimmune diseases, cancer and inherited disorders affecting the liver were included. Participants who took antibiotics, probiotic supplements and/or hepatotoxic medicines within 6 months before the start of the study and during the study, pregnant and breast-feeding women and those with >10 % of body weight loss during the study period were excluded from the study.

Participants were randomly allocated to receive either the synbiotic supplementation or the identical-appearing placebo capsules (maltodexterin) twice daily for 28 weeks. Each synbiotic capsule (Protexin; Probiotics International Ltd) contained 200 million bacteria of seven strains (Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium breve, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium longum and Lactobacillus bulgaricus) and prebiotic (125 mg fructo-oligosaccharide) and probiotic cultures (magnesium stearate (source: mineral and vegetable) and a vegetable capsule (hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose)). Adherence was assessed by capsule counts, confirmed at each visit. Both groups were advised to follow an energy-balanced diet and physical activity recommendations according to the Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults from the National Institutes of Health and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity( 13 ). Follow-up assessments were carried out every 7 weeks to assess participants’ dietary intakes and compliance. Anthropometric measurements, FibroScan test, serum concentrations of liver enzymes, fasting blood sugar (FBS), insulin, lipid profiles, high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), TNF-α and the activity of NF-κB in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were assessed at baseline and at the end of the study. NF-κB p65 was assessed in PBMC nuclear extracts using ELISA kits (Cell Signaling) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Ethical issues and informed consent process

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (94-04-563). The investigators provided all related information at a level of complexity that was understandable to subjects. Before participation, a written informed consent form was signed and dated by the subject and investigator. The study protocol is registered on Clinicaltrial.gov with registration Identifier NCT02530138.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was a significant reduction in hepatic steatosis measured using CAP scores of the FibroScan test. Secondary outcome measures were hepatic fibrosis, hepatic enzymes, glycaemic indices, lipid profile concentrations of inflammatory factors in serum and PBMC, and anthropometric variables.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS software (version 16; SPSS). For all analyses, a P value of 0·05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous and categorical data are presented as mean values and standard deviations and frequencies, respectively. Demographic variables were analysed using a χ 2 or t test, as appropriate. The data were analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle. In order to eliminate the effects of confounding factors, the ANCOVA test was used.

Results

Characteristics of the patients

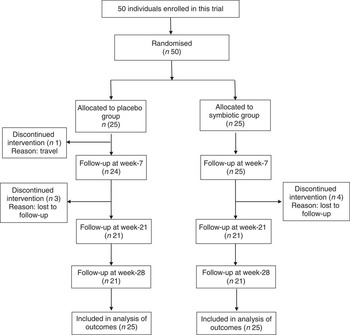

A total of fifty patients, who met our inclusion criteria, were recruited for the present study and were randomly assigned to consume either synbiotic (n 25) or placebo capsules (n 25). The consort flow chart of the study is shown in Fig. 1. The baseline clinical and demographic data of the participants were similar with respect to anthropometrics, biochemical and inflammatory characteristics as well as hepatic steatosis and fibrosis (Table 1).

Fig. 1 Consolidated standards of reporting trials flow diagram of the study participants.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics at enrolment (Mean values and standard deviations)

MET, metabolic equivalent of task; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; hs-CRP, high-sensitive C-reactive protein.

* Based on ANCOVA model regressing change from baseline on treatment group and baseline value of the outcome.

Primary outcome

In all, 84 % of patients completed 28 weeks of treatment. All enrolled patients were included in the analysis of outcomes. Hepatic steatosis reduced in both groups; however, the mean reduction in the synbiotic group was significantly greater compared with the placebo group (P<0·001) (Table 2).

Table 2 Change from baseline to end of treatment in liver histology by treatment group (Mean values with their standard errors)

* Based on ANCOVA model regressing change from baseline in the treatment group, and baseline value of the outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Hepatic fibrosis decreased in both groups, but this reduction was significantly greater in the synbiotic group (P<0·001) (Table 2). We found a significant decrease in hepatic enzymes within both groups; however, no significant differences were observed between the two groups except for aspartate aminotransferase (Table 3). At the end of the 28-week treatment period, significant improvements in lipid profile, FBS, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) were observed; however, the differences between the two groups were significant only in the case of FBS and TAG, which were improved significantly by synbiotic rather than placebo supplementation (Table 4). All the inflammatory markers decreased after treatment in both groups, although the mean decrease in the synbiotic group was greater than that in the placebo group, except for TNF-α (Table 5). None of the patients completing the study had any serious adverse events, indicating tolerance to treatment. As shown in Table 6, none of the dietary components were significantly different between and within groups during the study period.

Table 3 Change from baseline to end of treatment in hepatic enzymes by treatment group (Mean values with their standard errors)

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase.

* Based on ANCOVA model regressing change from baseline in the treatment group, baseline value of the outcome, and mean change of BMI, waist:hip ratio, WHR, metabolic equivalent of task and energy.

Table 4 Change from baseline to end of treatment in glycaemic and lipid profile by treatment group (Mean values with their standard errors)

FBS, fasting blood sugar; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; QUICKI, quantitative insulin sensitivity check index.

* Based on ANCOVA model regressing change from baseline in the treatment group, and baseline value of the outcome.

† To convert FBS in mg/dl to mmol/l, multiply by 0·0555. To convert insulin in mU/l to pmol/l, multiply by 6·945. To convert TAG in mg/dl to mmol/l, multiply by 0·0113. To convert cholesterol in mg/dl to mmol/l, multiply by 0·0259.

Table 5 Change from baseline to end of treatment in inflammatory factors by treatment group (Mean values with their standard errors)

hs-CRP, high-sensitive C-reactive protein.

* Based on ANCOVA model regressing change from baseline in the treatment group, and baseline value of the outcome.

Table 6 Changes from baseline in dietary intakes by treatment group (Mean values and 95 % confidence intervals)

* Based on ANCOVA model regressing change from baseline in the treatment group, and baseline value of the outcome.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial on lean NAFLD patients. Our results indicate that synbiotic supplementation improves hepatic features of NAFLD in patients with normal BMI.

The efficacy of synbiotic supplementation in NAFLD has been shown previously( Reference Eslamparast, Poustchi and Zamani 10 ). In our previous study, we found some evidence that synbiotic supplementation along with lifestyle modification is superior to lifestyle modification alone for the treatment of NAFLD in overweight and obese patients; however, lean patients were not included in that study. Although obesity is one of the main risk factors for fatty liver, it can also occur in lean subjects. Studies on liver donors and automobile crash victims have roughly found hepatic steatosis in 15 % of non-obese subjects( Reference Fabbrini, Sullivan and Klein 14 , Reference Vernon, Baranova and Younossi 15 ), which indicates that lean NAFLD might be a frequent cause of cryptogenic liver disorders. It seems that hepatic steatosis in lean people is a consequence of reduced β-oxidation of fatty acids, and decreased release of VLDL due to some genetic abnormalities( Reference Nakatsuka, Matsuyama and Yamaguchi 16 ). Although NAFLD is not rare in non-obese people( Reference Vos, Moreno and Nagy 3 , Reference Margariti, Deutsch and Manolakopoulos 17 ), no proven treatment for lean NAFLD/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) has been found yet.

Previous studies have shown that pathogenic bacteria products such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can move from the intestinal lumen to the lymphatic circulation. This activates the immune system, inducing regional and systemic inflammation, resulting in production of free radical species in the liver, which might contribute to development of NAFLD and NASH( Reference Strieter, Chensue and Basha 18 ). Thus, probiotics inhibit this procedure by reducing circulating LPS through modulation of intestinal microbiota, production of antibacterial substances and enhancement of gut barrier function results( Reference Iacono, Raso and Canani 19 – Reference Malaguarnera, Vacante and Antic 21 ). These beneficial effects of probiotics on NAFLD/NASH characteristics are due to reduction in oxidative stress and inflammation, whereas they are independent of metabolic disturbances involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH in obese people. Therefore, synbiotics can be an excellent therapeutic option for NAFLD patients with normal BMI.

In this study, the reduction in serum inflammatory cytokines was significantly greater in the synbiotic group except for TNF-α, which is in line with the results of some previous studies. Li et al.( Reference Li, Yang and Lin 22 ) reported that probiotics improved liver histology, reduced hepatic total fatty acid content and decreased serum ALT concentration. These effects were associated with a reduction in Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), a TNF-regulated stress kinase that promotes hepatic insulin resistance, and NF-κB activity, fatty acid β-oxidation and mitochondrial uncoupling protein-2 expression, all markers and factors characterising insulin resistance; however, they did not observe a reduction in hepatic TNF-α gene expression. They suggested that as probiotics supplementation decreased hepatic activity of JNK, a TNF-regulated stress kinase that promotes hepatic insulin resistance, it is conceivable that probiotic therapy is able to modulate hepatic insulin sensitivity independent to its ability to regulate hepatic TNF-α gene expression. Furthermore, as NF-κB was less activated in the synbiotic group than the placebo group, it seems that TNF-α gene expression was reduced by synbiotic consumption; however, its concentration in serum was not changed significantly.

The results of our previous study on overweight and obese patients with NAFLD showed a significant reduction in glycaemic indices as well as an improvement in serum lipid profile( Reference Eslamparast, Poustchi and Zamani 10 , Reference Eslamparast, Zamani and Hekmatdoost 23 ), which were consistent with other studies on these patients( Reference Malaguarnera, Vacante and Antic 21 , Reference Yadav, Jain and Sinha 24 , Reference Ma, Hua and Li 25 ). Synbiotics can improve insulin resistance through probable mechanisms such as modifying the gut flora, decreasing endotoxin concentrations, increasing faecal pH and reducing the production and absorption of intestinal toxins( Reference Iacono, Raso and Canani 19 , Reference Compare, Coccoli and Rocco 26 ). Our results showed that synbiotic consumption could reduce only FBS and TAG significantly compared with placebo, and no significant difference was observed in other glycaemic indices and lipid profiles between the two groups. This discrepancy might be explained by the normal glycaemic indices and lipid profiles at baseline, and thus the reduction in these parameters was not significantly different between the two groups.

Another mechanism that might be involved in the beneficial effects of synbiotics consumption on NAFLD is the role of probiotics in modification of SCFA production by intestinal bacteria. Butyrate and propionate at low amounts exert multiple advantageous effects on the host, including the prevention of intestinal inflammation and oxidative stress, improvement of intestinal barrier function and stimulation of satiety and lipid oxidation in hepatocytes( Reference Hosseini, Grootaert and Verstraete 27 , Reference Hamer, Jonkers and Venema 28 ). Acetate modulates insulin sensitivity and metabolic disorders( Reference van der Beek, Canfora and Lenaerta 29 ). SCFA have been identified as rich sources of energy for the host, and act as intestinotrophic agents to promote intestinal absorption of nutrients. Through their receptor G-protein-coupled receptor (GPR) 41 and GPR43, they reduce gut permeability and invasion of bacterial products via the portal vein and liver, and thus protect the liver from the ensuing damaging inflammation, which then results in down-regulation of insulin signalling in adipose tissue, thereby decreasing fat accumulation( Reference Zhu, Baker and Baker 30 ).

One of the limitations of present study was that we could not obtain liver biopsies to evaluate the pathology score of the disease; however, we used transient elastography (FibroScan®), which provides a quantitative, non-invasive evaluation of NAFLD by measuring hepatic steatosis (CAP score) and fibrosis( Reference Abenavoli and Beaugrand 31 , Reference Malekzadeh and Poustchi 32 ). It has been proven that this technique is a reliable, non-invasive method for identifying patients with significant hepatic steatosis and fibrosis. It is readily reproducible, and its score has low inter- and intra-observer variability( Reference Malekzadeh and Poustchi 32 ). Although there is another non-invasive fibrosis score system( Reference Angulo, Hui and Marchesini 33 ), we could not use it because we did not measure all the parameters of this equation.

The most important advantage of the present study is that it is the first clinical trial on lean patients with NAFLD. Other strengths of this study are the relatively long duration of the study, evaluating NF-κB activity in PBMC, the stratified blocked randomisation design and the fact that all the patients of the study were newly diagnosed with NAFLD, not having received any previous treatment( Reference Lindor, Kowdley and Heathcote 34 , Reference Loguercio, Federico and Tuccillo 35 ).

In conclusion, this randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial provides some evidence that synbiotic supplementation improves hepatic features of NAFLD in non-obese patients, at least partially through attenuation of inflammation. Whether these effects will sustain in longer treatment durations remains to be determined.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Protexin Company, UK, for their gift of synbiotic supplements.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute of the Shahid Beheshti University and the Digestive Disease Research Center of the Shariati Hospital. Protexin Company, UK, provided the synbiotics supplements, and Nikan Teb Co. provided the FibroScan machine.

F. M. and A. H. had full access to all the data of the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis. F. M., H. P., M. S., R. M. and A. H. conceived and designed the study and provided administrative support. F. M., H. P., Z. Y., B. N., S. M., R. M. and A. H. conducted the study. F. M. and A. H. wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.