Iodine deficiency has been demonstrated in the UK in recent years in women of childbearing age( Reference Vanderpump, Lazarus and Smyth 1 – Reference Rayman, Sleeth and Walter 3 ) and pregnant women( Reference Bath, Wright and Taylor 4 – Reference Kibirige, Hutchison and Owen 7 ). The UK is now among the top ten iodine-deficient countries worldwide( Reference Andersson, Karumbunathan and Zimmermann 8 ), based on data from the 2011 national survey of teenage schoolgirls that revealed mild iodine deficiency in the cohort( Reference Vanderpump, Lazarus and Smyth 1 ). This situation is of concern owing to the fact that iodine, required for thyroid hormone production, is essential for brain development during gestation and early life( Reference Zimmermann 9 ).

Salt is recommended by the WHO as the food vehicle for iodine fortification in a population to prevent and correct iodine deficiency( 10 ). Europe is reported to have a lower coverage of iodised salt than other regions of the world( Reference Andersson, de Benoist and Darton-Hill 11 ). Unlike many countries, the UK has never had a policy of voluntary or mandatory iodisation of salt, even in the past when goitre was endemic in the country( Reference Phillips 12 ); instead it has relied on the adventitious supply of iodine through milk and dairy produce consumption( Reference Phillips 12 ). The iodine status of the UK has not been regularly monitored( Reference Andersson, de Benoist and Darton-Hill 11 ) and indeed the survey of teenage schoolgirls was the first national survey of iodine status for over 60 years( Reference Vanderpump, Lazarus and Smyth 1 ). UK iodine intake had been assumed to be adequate for many years which may explain the absence of an iodised-salt policy.

The household use of iodised salt in the UK is presumed to be low( Reference Lazarus and Smyth 6 , Reference Andersson, de Benoist and Darton-Hill 11 ) but it is also assumed that over 90 % of households have access to iodised salt( 13 ). There is just one small survey at a single location in the UK that has provided data on iodised-salt availability in the country. Additional data on availability of iodised salt for household use, and its cost, are therefore required to inform UK public-health policy. The current study aimed to survey the availability of iodised salt in major supermarket chains located in Southern England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Experimental methods

Iodised-salt availability was determined through a supermarket shelf survey that was conducted in June, July and August 2009 in sixteen areas (largely counties) of the UK: fourteen areas were in Southern England, one area was in Wales (Cardiff) and one was in Northern Ireland (County Antrim)( Reference Bath, Button and Rayman 14 ). These areas were selected for logistical reasons but also to include densely populated regions (e.g. London) as well as rural counties (e.g. Cornwall). In each area, the shelves of the five leading supermarket chains (total market share 79·4 %( 15 )) were inspected, although sampling was restricted in Northern Ireland as only two major supermarket chains operated there. Thus, a total of seventy-seven supermarket stores were included in the survey. The cost of iodised salt sold in these stores was compared with that of standard table salt.

Availability of iodised salt was calculated in two ways: (i) stores selling iodised salt as a percentage of the total number of stores investigated; and (ii) a weighted figure for iodised-salt availability, calculated by multiplying the percentage availability in each supermarket chain by the percentage of market share for the chain( 15 ) and summing the values to give a total.

After data collection in 2009, the authors discovered that all salt sold in another small supermarket chain (Lidl; market share 2·3 %( 15 )) was iodised and this was confirmed by the buying department of Lidl. The availability of iodised salt in Lidl was therefore considered to be 100 % and this figure, along with market-share data, was used to calculate the overall weighted iodised-salt availability in the UK.

Results

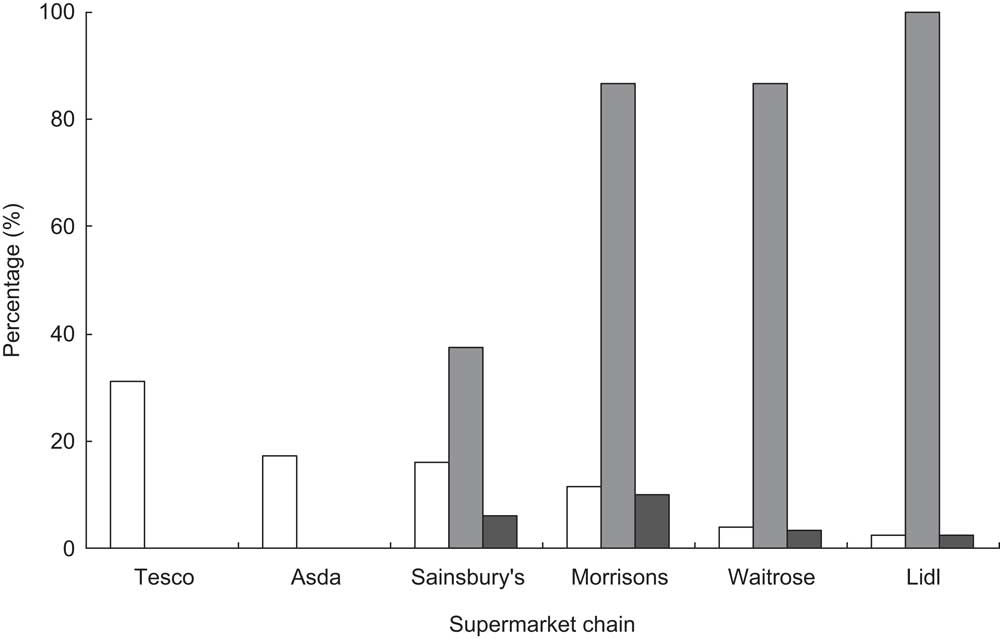

Iodised salt was available in thirty-two of the seventy-seven supermarkets (41·6 %) investigated in the shelf survey. It was not available in all supermarket chains (Table 1) and, with the exception of Lidl, in those chains that did sell iodised salt, it was not consistently available in all of the stores surveyed. Using market-share values to calculate a weighted availability figure, only 21·5 % of the supermarket share of the total grocery market is exposed to iodised salt (Table 1). Figure 1 shows that there is an inverse relationship between the market share of the supermarket chain and iodised-salt availability.

Table 1 Availability of iodised salt, according to supermarket chain, in a survey of supermarket stores in Southern England, Wales and Northern Ireland between June and August 2009. Market-share data from the time of the survey were used to calculate weighted availability

N/A, not applicable.

*The only supermarket chains that operated in Northern Ireland.

†Data collected from customer services information, not shelf-survey data.

‡Calculation based on data collected during the shelf survey.

§Calculation based on shelf-survey data and includes data from the Lidl supermarket chain.

Fig. 1 Iodised-salt availability (![]() ) according to UK supermarket chain, based on a survey of seventy-seven supermarket stores (fifteen or sixteen stores from each chain in Southern England, Wales and Northern Ireland) between June and August 2009 or based on information from the buying department for Lidl. Weighted iodised-salt availability (

) according to UK supermarket chain, based on a survey of seventy-seven supermarket stores (fifteen or sixteen stores from each chain in Southern England, Wales and Northern Ireland) between June and August 2009 or based on information from the buying department for Lidl. Weighted iodised-salt availability (![]() ) is shown for each chain, taking into account the market share (

) is shown for each chain, taking into account the market share (![]() ) of the supermarket chain(

15

)

) of the supermarket chain(

15

)

Lidl sells its own brand of iodised salt but in the other supermarket chains surveyed, the only brand of iodised salt available was Cerebos (Premier Foods Group Ltd, Spalding, Lincs), which has a 0·6 % volume share( 16 ) of the UK table-salt market. Cerebos iodised salt contains iodine at a concentration of 11·5 mg/kg, whereas the salt sold in Lidl has an iodine concentration of 20 mg/kg.

The cost of iodised salt in the supermarkets studied in the shelf survey was between 122·5 and 147·5 pence per kilogram; in comparison, standard table salt cost just 23 pence per kilogram. Iodised salt was therefore between 5·3 and 6·4 times more expensive than standard table salt. By contrast, the price of iodised salt sold in Lidl was similar to that of standard table salt elsewhere.

Discussion

This is the first sizeable survey of iodised-salt availability in the UK; we have collected data from over seventy-five retail outlets in various regions of the country. Our results suggest that the availability of iodised salt for UK household use is low and, after taking into account the market share of the outlets that stock iodised salt, it is available to fewer than a quarter of supermarket shoppers. It is of interest, and of concern, that the two supermarkets with the largest market share did not sell iodised salt in any of their stores, highlighting the fact that the majority of shoppers are not exposed to an iodised-salt alternative to standard table salt. The current study supports the findings of the previous survey of UK salt that showed that a only a low percentage (5 %) of salt samples purchased in Cardiff (two out of thirty-six) had iodine concentrations suitable for the prevention of iodine deficiency( Reference Lazarus and Smyth 6 ). The fact that the Cerebos iodised salt has a volume share that is less than 1 % of the UK table-salt market reflects in part the poor availability of the product, but also suggests that even in outlets that sell the salt, consumers are not choosing to purchase it. By contrast, sea salt is a more popular table salt choice and is considered by some consumers as a ‘healthier’ alternative to standard table salt( 17 ). Indeed, it is a common myth that sea salt is a good source of iodine but this is not the case as iodine is lost in the manufacturing process( Reference Mannar and Dunn 18 ).

Historic reports of goitre in the UK prompted recommendations in the 1940s by the Medical Research Council that salt should be iodised( Reference Phillips 12 , Reference Kelly and Snedden 19 ). However, this recommendation was not followed and it was the adventitious increase in the iodine content of milk that led to the eradication of goitre in the UK( Reference Phillips 12 ), rather than a public-health policy that included iodisation of salt. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that iodised salt has a current low profile, there being an absence of an iodised-salt programme (voluntary or mandatory) in the UK. There is a degree of ignorance about this fact among health professionals in the UK, with some (including dietitians and midwives) assuming that salt is iodised. There is also false information on the National Health Service (NHS) website that goitre was eradicated in the UK by an iodised-salt policy( 20 ). Without an iodised-salt programme, UK iodine intake is dependent entirely on food choices and in view of the low popularity of iodine-rich food sources (e.g. fish and milk) in some population groups, individuals are vulnerable to iodine deficiency( Reference Smyth 21 ).

Contribution of iodised salt to iodine intake in the UK

Since 2004, public-health recommendations in the UK are to restrict total salt intake to less than 6 g/d, owing to links between a high sodium intake (of which salt is the main dietary source), high blood pressure and consequent health problems such as stroke and heart disease( 22 , 23 ). As part of this campaign, UK authorities and organisations have discouraged the use of table salt( 24 , Reference Daniels 25 ) resulting in increased efforts by individuals to reduce their total salt intake( Reference Wyness, Butriss and Stanner 26 ). In fact, the majority of UK sodium intake is from salt in processed foods, which is unlikely to be iodised; consequently discretionary salt use (i.e. in cooking and at the table) contributes only a small percentage (approximately 15 %) to total sodium intake( 22 ). The main brand of iodised salt in the UK supermarkets has an iodine concentration (11·5 mg/kg) that would provide only approximately 8 % of the adult iodine requirement (150 μg/d( Reference Zimmermann 9 )) if one gram of iodised table salt were used in the home. Thus, even if the availability of iodised table salt were higher, given the declining use of table salt and the low iodine concentration in the major brand of iodised salt available, iodised-salt use by the general public would be unlikely to contribute meaningful quantities of iodine to the UK diet.

In addition, the iodised salt available in the major supermarket chains was up to six times more expensive than standard table salt. The premium price attached to this product may dissuade people from purchasing it unless the benefits of iodine are clear to them. By contrast, the only salt available in Lidl is iodised and is not more expensive than standard table salt, with a higher iodine concentration (20 mg/kg). This may be because the supermarket is a German company and the salt available in its UK stores may be that sold in its European outlets, where salt is iodised by mandatory or voluntary iodised-salt programmes. As this chain has a low market share in the UK( 15 ), the higher availability of iodised salt is unlikely substantially to influence iodine intake in the population.

Iodised salt and the salt-reduction campaign in the UK – a conflict?

There are obvious potential conflicts between an iodised-salt programme and a salt-reduction campaign and the public may feel that the messages are confusing; on the one hand the advice is to restrict salt intake for health protection, while on the other hand, iodised salt contains an important mineral for health. This was the subject of the comment by the UK charity CASH (Consensus Action on Salt and Health)( 27 ) following the publication of the study showing mild iodine deficiency in UK schoolgirls( Reference Vanderpump, Lazarus and Smyth 1 ). Both CASH and the WHO are in agreement that iodised salt should not be used as an excuse for recommending increased salt intake and public-health messages must be clear( 27 , 28 ). The WHO stresses that iodised-salt programmes can run concurrently with salt-reduction campaigns, as individual countries can set the concentration of iodine in salt to provide adequate iodine intake from a lower total salt intake( 28 ). The UK has an average salt intake of 8·6 g/d, with only 26 % achieving the recommended 6 g or less daily( 29 ). There are also variations in salt intake between sex and age groups, with young men (19–24 years) consuming an estimated 10·7 g/d whereas older women (50–64 years) consume only 7·0 g/d; the top 2·5th percentile ranges from 13·9 to 18·0 g/d( 29 ). If the UK were to introduce an iodised-salt programme, such a variation in salt intake would make setting the iodine concentration in salt challenging; appropriate levels of iodine would need to be provided for the majority without overdosing those with the highest intake of salt. Additionally, salt iodisation would need to be in harmony with the existing UK policy of salt reduction in order to achieve both improved iodine intake and targets for reduced salt intake. It may be preferable to encourage manufacturers to use iodised salt in certain staple foods that are eaten in the context of a healthy diet, such as bread. This has been implemented in Australia and New Zealand, where, since 2009, it has been mandatory for bread to be fortified with iodine (through iodised-salt use)( 30 ) and this fortification programme has been associated with improved iodine status in New Zealand schoolchildren( Reference Skeaff and Lonsdale-Cooper 31 ).

It is worth remembering that UK milk is currently an alternative vehicle for iodine fortification of the UK population, although this has been termed an ‘accidental public health triumph’( Reference Phillips 12 ). Milk and dairy products are a haphazard source of iodine and the iodine content varies according to farming practice( Reference Bath, Button and Rayman 14 ) and season( Reference Phillips 12 ). If the UK Government pursues an iodine fortification strategy in the future, careful consideration will need to be given to: (i) take account of the level of iodine that is currently provided by milk and dairy produce consumption; (ii) ensure that the strategy is sensitive to salt-reduction campaigns; and (iii) put in place a robust programme of monitoring to ensure that any potential risks are minimised and that the population iodine intake is neither deficient nor excessive( 10 ).

Limitations of the present study

The present study is not exhaustive or extensive as it sampled only retail outlets in sixteen areas of the UK. However, we included supermarkets in neighbourhoods with indices of deprivation that ranged from high (e.g. Yateley in Hampshire, ranked 32 219/32 482) to low (e.g. Weston-super-Mare in Somerset, ranked 1425/32 482)( 32 ), so it is likely that the results are reasonably representative of the UK as a whole. The results are also limited to the time period in which the study was conducted. Purchasing decisions and stock may change in retail outlets and consequently iodised salt may become more or less available in the future. The study has not assessed iodised-salt consumption by UK shoppers which would be a worthwhile research question in a future study.

Conclusion

In view of the fact that iodised-salt availability is low in the UK, the country does not have a regulated programme of iodine fortification of staple foods with iodised salt and that table salt contributes a relatively small percentage to total salt intake( 22 , 24 ), current use of household iodised salt is unlikely to protect individuals living in the UK from iodine deficiency or contribute meaningful amounts of iodine to the diet.

UK iodine intakes are dependent entirely on food choice and good sources, such as milk and fish, may not be consumed sufficiently by all. Consequently, there is a need for routine monitoring of the iodine status of the population.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: Studentship funding for S.C.B. by The Waterloo Foundation and Wassen International supported this work. The funding bodies did not have influence over any part of the study. Conflicts of interest: None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest. Ethics: Ethical approval was not required. Authors’ contributions: S.C.B. and M.P.R. designed the study, S.C.B. and S.B. collected the data, S.C.B. analysed the data, M.P.R. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors prepared, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.