The revolutions of 1848 set Europe ablaze. The flames erupted in Paris on February 22 and soon spread north, south, east, and west. In short order, the fiery revolutions leapt from France into the Caribbean Sea and onto the American mainland.Footnote 1

The 1848 revolutions impacted American domestic and foreign policy as they increased the need for agricultural labor in the West Indies, elevated fear of abolition among southern slaveholders, and brought disappointed European revolutionaries to seek new opportunities across the Atlantic.Footnote 2 Importantly, the European revolutions of 1848 resulted in slavery’s abolition in both the French and Danish West Indies and served as a striking example of the transnational ties between Europe and the New World.

On February 25, 1848, the French provisional government “declared a republic and also emancipation with indemnity” on the slaveholding islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, in part due to fears of slave revolts such as the one that led to Haitian independence in 1804.Footnote 3 As Rebecca Schloss has shown, events in the West Indies soon overtook political decisions on the mainland about the practical transition to free labor.

[O]n May 22 more than twenty thousand enslaved workers crowded the streets of Saint Pierre, Martinique demanding their freedom. Shortly afterward, the island’s governor proclaimed emancipation and initiated a new chapter in the complex interplay of race, class, and gender in the French Atlantic.Footnote 4

By July 1848 the French West Indian unrest, and ensuing emancipation, served as partial inspiration for an uprising on the neighboring island of St. Croix in the Danish West Indies (see Figure 1.1).Footnote 5 Thus, Governor Peter von Scholten concluded that the islands’ enslaved population would wait no longer for freedom. A widespread but generally peaceful uprising on St. Croix in July settled the matter.Footnote 6

Figure 1.1 French depictions of abolition in the West Indies, such as this one by artist François-Auguste Biard, mirrored those in Denmark and underscored the pervasive Old World colonial mindset.

Von Scholten’s emancipation had not been authorized by King Frederik VII, however, and the governor was promptly replaced by councillor of state Peter Hansen, who was tasked with reorganizing labor relations between a planter class who felt betrayed by the Danish government’s failure to ensure the twelve-year transition period promised them in 1847 and the newly freed laborers who demanded better work conditions.Footnote 7 From Governor Hansen’s perspective, retaining control of the labor force was the main objective, and, following the lead of larger European powers, not least Great Britain and France, Danish officials by the late 1850s looked to amend American colonization policy to augment the islands’ labor force.Footnote 8

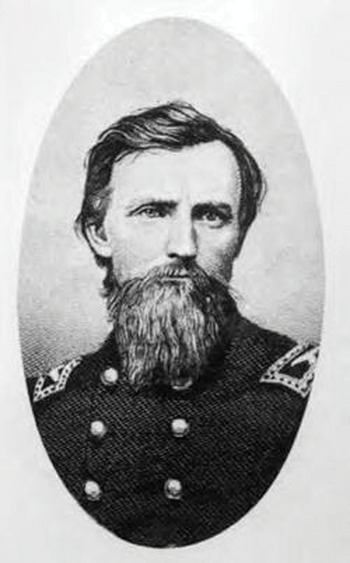

During the early 1860s, colonization in the United States was legally directed toward Liberia, but – in no small part due to Danish diplomats – the policy was reoriented to also include the Caribbean.Footnote 9 Moreover, slavery’s abolition in the Danish and French West Indies sparked fear, as well as jubilation, in the United States.Footnote 10 In the immediate aftermath of emancipation in the West Indies, southern slaveholders peered somewhat fearfully toward the Caribbean emancipation initiatives.Footnote 11 In New York, Frederick Douglass, abolitionist and editor of the North Star after his escape from slavery, remarked optimistically in 1848 that the revolution initiated in Europe flashed “with lightning speed from heart to heart, from land to land,” until it would eventually traverse the entire globe (see Figure 1.2).Footnote 12

Yet by 1851 it was clear that American abolitionists would have to bide their time, as most nations on the European mainland had reverted back to their prerevolution roles in an uneasy equilibrium of monarchical and imperial power balanced mainly between Russia, France, Great Britain, Austria, and the German states.Footnote 13

On the European mainland, underlying social issues and overarching political structures tied population groups together across borders. Uprisings in Frankfurt in 1833, Paris in 1839, and Kraków in 1846 attested to the widespread political, social, and economic discontent across Europe.Footnote 14 In Wolfram Siemann’s words, lack of political participation, the urge for national self-determination, a crisis of “pre-industrial craft trades,” and failed harvests resulting in famine were key driving forces behind uprisings in the spring of 1848.Footnote 15 As a result, revolutionary sentiment among nationalist and politically marginalized groups within Scandinavia, France, Italy, Poland, and Germany sparked uprisings across the continent that simultaneously strengthened and challenged nationalistic ideas within existing borders. In Northern Europe, along Denmark’s southern regions, embers that had smoldered for years suddenly burst into flames and led to a civil war within the kingdom that revealed tangible divisions along political, ideological, social, ethnic, national, separatist, and dynastic lines.Footnote 16

Despite his personal resistance to democratic reform, King Christian VIII had prepared an eventual transition from absolutism to constitutional monarchy before his death on January 20, 1848. This political move toward at least nominal democracy based on a moderately liberal constitution was accepted by the new king, Frederik VII, in the so-called January rescript of January 28, 1848, the commitment to which was strengthened and reiterated after a sizable but peaceful demonstration by an estimated 20,000 people in Copenhagen on March 21, 1848.Footnote 17

In Sweden and Norway, the European revolutions fueled protests in Stockholm and a popular Norwegian movement led by revolutionary Marcus Thrane, but the relatively well-functioning political system in Norway (based on the Eidsvoll Constitution of 1814), coupled with an eventual crackdown by the authorities on Thrane “for conspiracy against the state” in July 1851, prevented the movement, which at its height attracted close to 30,000 followers, from gaining even wider traction during these years.Footnote 18

Despite the largely peaceful political responses to grassroots dissent, King Frederik VII’s decision to move toward constitutional monarchy left a power vacuum within the Danish kingdom. Danish- and German-speaking nationalists both seized this European revolutionary moment, hoping to shape the Danish kingdom’s future according to their own interests.Footnote 19

On Denmark’s southern border, the key point of contention was the status of Schleswig and Holstein.Footnote 20 Since the so-called Ribe Treaty of 1460, the duchies Schleswig and Holstein had been united, based on an understanding that they would remain forever undivided (“up ewig Ungedeelt”).Footnote 21 Hereafter, the Danish monarch became the Count of Holstein and also incorporated the duchy of Schleswig under Danish rule.

The rise of nationalist sentiment among Danish speakers throughout the 1840s, concretized in a political faction called “nationalliberale” (national liberals), led to calls for the consolidation of the Danish kingdom more clearly along cultural and linguistic lines, by dividing Schleswig from German-speaking Holstein along Ejderen, a river running east–west toward the important seaport of Kiel.Footnote 22 Conversely, the population within the Danish kingdom’s borders who identified as German took the revolution in France as a touchstone for their own nationalist claims. On March 18, 1848, less than a month after the revolution’s outbreak in Paris, German-speaking residents of Schleswig-Holstein demanded that the duchies remain undivided with the aim to break away from Denmark. The Danish king dismissed the German-speaking Schleswig-Holsteiners’ petition and instead made statements about incorporating Schleswig without Holstein directly under Danish rule. The irreconcilable positions led to German separatists seizing a Danish fortress in Schleswig-Holstein on March 24, 1848, and forming a “provisional state government.”Footnote 23

This civil war, now known as the First Schleswig War, lasted from 1848 to 1850.Footnote 24 In accordance with the threshold principle, the national liberals feared that Denmark would become a mini-state, if it lost part of Schleswig and all of Holstein, and therefore started to explore Scandinavian alliances.Footnote 25 Pan-Scandinavian sentiment was especially strong among the younger Scandinavian intelligentsia, in spite of the relatively modest 387 Swedes and Norwegians (several of whom would eventually end up in the American Civil War) who volunteered to fight against German separatists.Footnote 26 The spirit of pan-Scandinavianism, however, was concretized at the political level when Sweden, prompted by King Oscar, sent 4,500 troops to defend Denmark’s monarchical rule against the German-speaking rebels, with the promise of up to 15,000 troops in all if the Danish mainland were to be invaded (safeguarded by the provision that Sweden would then have to be part of a broader international coalition led by Great Britain and Russia).Footnote 27

Yet the pan-Scandinavian enthusiasm proved to have notable diplomatic (and nationalist) limitations when confronted with the complexity of high-level European politics. In just one of numerous factors complicating the First Schleswig War, Denmark and Sweden had been on opposite sides for parts of the Napoleonic Wars, and the peace conference of 1814 in Kiel forced Denmark to cede Norway (which had been part of the Danish Kingdom since 1380) to Sweden.Footnote 28

Thus, despite several ambitious attempts, a pan-Scandinavian state incorporating northern Schleswig but excising the German-speaking regions found little concrete backing among more experienced Scandinavian power brokers, not least Danish conservative leaders who insisted on keeping the entire state together to maintain the territory and population already under Danish rule.Footnote 29

Additionally, there was a strong sense among Europe’s great powers, especially Great Britain and Russia, that German control of the important Schleswig harbor of Kiel was undesirable as it would help German Grossstaatenbildung.Footnote 30 Consequently, Russia and Great Britain worked actively to curtail the armed conflict and protect Danish territorial sovereignty in the name of stability (as opposed to revolution or disruption of the international trade). Thus, through the great powers’ intervention, the pre-1848 borders were eventually reestablished.Footnote 31

Across Europe, the lack of revolutionary result caused thousands of disappointed “Forty-Eighters” to seek freedom and liberty elsewhere – and many in the United States.Footnote 32 Even in Scandinavia, where the 1848 revolutions had prompted King Frederik VII to sign grundloven (the Constitution), the effect for people with little economic or political power was negligible. Consequently, a steady emigration from Scandinavia started picking up speed, especially from rural areas.

Additionally, decisions to emigrate were likely accelerated among the German-speaking population in Schleswig and Holstein by the Danish government’s determination to impose strict language requirements and banish revolutionary leaders such as Hans Reimer Claussen and Theodore Olshausen, both of whom eventually ended up in America.Footnote 33 When Claussen arrived in Davenport, Iowa, he apparently found a welcoming community of a “large number of his closest countrymen, the Schleswig-Holsteiners.”Footnote 34

Other German-speaking subjects living within Danish borders struck out for Wisconsin, as was the case for August Hauer, who arrived with his family in what became New Denmark (and who, according to one account, “was a mortal enemy” of everything associated with the Danish state for decades afterward).Footnote 35

The exact number of German-speaking Forty-Eighters who emigrated for political reasons after the First Schleswig War is difficult to ascertain, but the legacy of the 1848 revolutions in terms of political rights, economic opportunity, and abolition of slavery continued to impact American and Scandinavian society in the years afterward.Footnote 36

Whether settling in Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, or Minnesota – or, for a few, even Missouri, Louisiana, or Texas – the German, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian Forty-Eighters who emigrated in the wake of the revolutions generally found some common ground in their interpretation of equality and liberty. Despite Old World divisions, these Northern European immigrants’ experience with class divisions would continue to shape their engagement with issues of social mobility and equality in America. At the very center of such discussions was the importance of owning land.Footnote 37

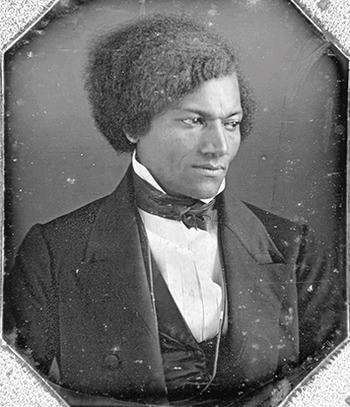

It was still dark when Claus Clausen shook his mother’s hand for the last time. Prompted by Norwegian settlers in Wisconsin, the twenty-two-year-old aspiring pastor was leaving Denmark for the relative unknown of America along with his twenty-seven-year-old wife Martha.Footnote 1 In time, Claus Clausen would become one of the most prominent Scandinavian anti-slavery pastors in America and chaplain of a celebrated Scandinavian Civil War unit (see Figure 2.1). Yet, this early spring morning, April 10, 1843, Claus and Martha Clausen were part of a mass-migration vanguard that in less than a century would lead more than two million fellow Scandinavians to the United States.Footnote 2

Figure 2.1 Claus L. Clausen photographed on the island of Langeland during a visit to Denmark after the Civil War.

Since the 1830s, Amerikafeber (America fever) had spread slowly across Scandinavia and was now beginning to reach even remote villages. Like an invisible hand, the “contagion” crept from Norway through Sweden and into Denmark.Footnote 3 Poets and cultural icons such as Denmark’s Hans Christian Andersen, Sweden’s Fredrika Bremer, and Norway’s Henrik Wergeland (at least initially) helped spread this fervor for America and tied it closely to a mental image of an economic dreamland across the Atlantic.Footnote 4 In America, according to Andersen, horses’ hoofs were covered in silver and fields bloomed with money.

Together, Andersen and Bremer, who knew each other well, helped disseminate a New World image closely associated with upward social mobility, and Scandinavian literature regularly portrayed the United States as an El Dorado. Yet, perhaps not surprisingly, prospective Scandinavian emigrants needed more tangible advice before making life-changing decisions associated with emigration. Thus, when seemingly reliable pamphlets appeared just a few years after Andersen’s song lyrics, so did Scandinavian communities start to appear across the Atlantic.

The first published pamphlet based on concrete experience in the United States was Ole Rynning’s True Account of America from 1838, which sparked the migration imagination in several Norwegian villages. Rynning described abundant land, wildlife, and relatively cheap agricultural opportunities. Especially the idea of ample American government land was attractive for many Scandinavian smallholders who often found it impossible to amass more than a few acres in their Old World villages due to the nobility’s vast landholdings.Footnote 6

Rynning’s account, written in the winter of 1837–8, “had a considerable effect upon the emigration,” noted the late Norwegian-American historian Theodore C. Blegen.Footnote 7 Unfortunately, Rynning’s pioneer group of Norwegians settled in a swampy region of Iroquois County, Illinois, and by 1838 many had succumbed to malarial fever and other illnesses – Rynning among them.Footnote 8 Yet Ansten Nattestad, one of Rynning’s fellow community members, carried his manuscript back in the spring of 1838 along with several “America letters.” Upon Nattestad’s return to family and friends in Norway, he was besieged by prospective emigrants, one of whom noted:

Hardly any other Norwegian publication has been purchased and read with such avidity as this Rynning’s Account of America. People traveled long distances to hear “news” from the land of wonders, and many who before were scarcely able to read began in earnest to practice in the “America-book,” making such progress that they were soon able to spell their way forward and acquire most of the contents.Footnote 9

Another writer noted, “It is said that wherever Ole Rynning’s book was read anywhere in Norway, people listened as attentively as if they were in church.”Footnote 10 One of the emigration parties that left Norway shortly after the publication of Rynning’s book, and Nattestad’s visit, was a group from Telemarken who established their colony in eastern Wisconsin and by 1841 needed a spiritual guide. The settlement leaders, a young emigrant named Sören Bache among them, wrote family and friends back in Norway to find the right person. Bache’s father, Tollef, helped convince Claus Clausen, who had traveled through Norway in the summer of 1841, that Muskego, Wisconsin, would be the best locality to do religious work. Letters from Sören Bache helped cement the agreement.Footnote 11

On October 6, 1842, Sören Bache wrote Clausen from Muskego, a Norwegian settlement about 20 miles south of Milwaukee, to ease any concern about “his material well-being”; he assured Clausen that the land “is very good and rich and bears all sorts of grains without being fertilized. There is still plenty of government land to be had at $1.25 per acre. … I believe that anyone who is not too emotionally bound to his native place will be happy in America.”Footnote 12

Bache’s letter to Clausen underscored the importance of landownership as a means to social uplift among Scandinavian immigrants, and Rynning’s original account reflected these concerns by treating the “quality of the land” in one of his first and most thorough chapters.Footnote 13

While the decision to emigrate from Scandinavia could have multiple individual causes, economic opportunity, political rights, and religious freedom were the most significant factors pulling Scandinavian immigrants toward the United States in the Civil War era. The lack of land in the Old World was the most important circumstance pushing poorer immigrants out of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark in the years leading up to the Civil War, and the letters and emigration pamphlets that appeared in Scandinavia in the 1840s sparked ideas about American institutions that powerfully informed Scandinavian immigrants’ imaginations about the meaning of American citizenship.Footnote 14

To afford the dream of emigration to, and landownership in, America, a number of prospective Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish farmers started selling off their possessions during the 1840s.Footnote 15 For Claus Clausen, the allure of “a safe income for the future” played an important part in his decision to emigrate, but there was also a strong religious component to his choice.Footnote 16 In this, Clausen was far from alone. As Theodore Blegen argued in 1921, “religious motives” played a larger part “than has usually been recognized in connection with the emigration after 1825,” and, for several Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes in the earliest settlements, the Scandinavian state churches’ conservatism was a contributing factor to emigration.Footnote 17

Clausen was deeply influenced by Nikolai F. S. Grundtvig, who spearheaded the revivalist movement known as Grundtvigianism and was censored by the Danish state church between 1826 and 1837 for his writings.Footnote 18 By 1843, however, Grundtvig had been accepted back into the state church, resumed preaching, and become an increasingly influential pastor of international renown.Footnote 19 Additionally, Clausen had been introduced to the teachings of Hans Nielsen Hauge, a layman preacher who led a religious protest against the Norwegian state church and was jailed for his views between 1804 and 1814.Footnote 20 It was followers of Hans Hauge in Muskego who enticed Claus Clausen to emigrate with the promise of a denomination – as well as official ordination – in Wisconsin.Footnote 21

Thus, the Clausen family members said their final goodbyes at 4 a.m. in a little Danish hamlet.Footnote 22 “We wished them [to] live well in peace of the lord until we all are reunited at the lamb’s throne and they wished us the same under many tears,” wrote Clausen in his diary.Footnote 23

A friend drove the couple to the town of Slagelse, 63 miles (and a twelve-hour carriage ride) outside of Copenhagen, where they arrived half an hour before the horse-drawn stagecoach left for the Danish capital. Claus and Martha Clausen decided to remain in Copenhagen for a week over Easter, where the couple, according to Clausen’s diary entries, had the pleasure of attending several sermons by Grundtvig at an important political moment in the Danish anti-slavery cause.Footnote 24

Since 1839, Grundtvig had been one of three founding members of the Danish anti-slavery committee (the other two being Professor Christian N. David and Jean-Antoine Raffard of the French Reformed Church of Copenhagen), a society formed in the immediate aftermath of a visit from the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.Footnote 25 The society’s secretary, George W. Alexander, met with several dignitaries when he visited Scandinavia in September 1839 to advocate abolition of slavery on the islands of the Danish West Indies and Swedish St. Barthelémy, and he subsequently reported back that he deemed Grundtvig, along with David and Raffard, “among the best friends of the Cause of negro freedom.”Footnote 26

Notably, none of the three founding members of the Danish anti-slavery committee were uncritical members of the Danish political and religious “establishment.” Both Grundtvig and David (the latter an economics professor of Jewish descent) had experienced censorship of their writings, and Raffard’s role in the French Reformed Church by definition set him apart from the Danish establishment clergy. The three founding anti-slavery committee members were therefore somewhat removed from more conservative societal institutions. The members of the committee advocated the importance of belief in a common humanity and the immediate abolition of slavery, but they also regularly expressed a sense of moral superiority in relation to people of African descent.Footnote 27

After the three members’ first meeting, Grundtvig was asked to write a statement about the views and aims of the committee. Grundtvig denounced slavery and expressed empathy with “our unhappy fellow human beings, who are sold as commodities and are treated – be it harshly or in a lenient way – as domestic animals,” but he also claimed that “the slaves on our west-indian islands usually are treated in a milder way than are the majority of others.”Footnote 28 Grundtvig’s statement was never published, but the document’s ideological underpinnings – slavery’s immorality, infused with supposed superior Scandinavian morality in dealing with slavery – were not uncommon among educated Scandinavians and found their way to the public through C. N. David’s writings in late 1839.Footnote 29

After praising the Danish monarch for being the first European regent to abolish the slave trade in 1792, David informed Danish readers that the native inhabitants of the African Gold Coast, despite the supposed civilizing influence from Europeans, had over time only become more unenlightened, more sinful, and more bestial because of the slave trade.Footnote 30 Though the Danish slave trade ban did not take effect until 1803, the decree served as the source of countless claims of moral superiority by Scandinavian authors in subsequent debates over slavery.Footnote 31 As Pernille Ipsen has succinctly pointed out, “the discourse that helped abolish the slave trade also helped produce racial difference” as the better-educated Scandinavians in the Civil War era came of age in a slaveholding nation where subjugation of Africans, justified in part through science and culture, was an extension of the power and labor dynamics within the Danish and Swedish kingdoms.Footnote 32

In Denmark, “the period of Atlantic slavery,” as Ipsen has demonstrated, was marked “by an ever-deepening linkage of slavery and blackness,” a process that “happened not only on European slave ships, but in European art, literature, and travel accounts and in every corner of the Atlantic touched or affected by the Atlantic slave trade and plantation system.”Footnote 33

These texts about Africa and Africans became part of a transnational flow of ideas that framed Black people as undesirable and inferior in an attempt to rationalize Danish slavery. As an example of perceived African inferiority, a Danish governor of the slavetrading post Christiansborg on Africa’s west coast in 1726 dismissed the idea of his men bringing their local African wives back to Copenhagen, “as the general opinion in Denmark was [not] in favor of Africans.”Footnote 34

The same was true in the Swedish kingdom, where cultural images and scientific texts legitimizing African inferiority circulated with increased frequency in the eighteenth century. While Benjamin Franklin, in his by now well-known classification from 1751, lumped Swedes together with “the Spanish, the Italians, the French, and the Russians” as people with a “swarthy complexion,” lower than white English people and slightly above “black or tawny” people, Scandinavian researchers more clearly demarcated themselves from Africans in culture and so-called science.Footnote 35

Swedish scientist Carl von Linné (Linneaus), for example, in 1735 created a typology where he distinguished Europeans from Indians, Asians, and Africans. In his Systema Naturae, Linneaus situated human beings at top of the animal kingdom, and at the “pinnacle of his human kingdom reigned H. sapiens europaeus: ‘Very smart, inventive. Covered by tight clothing. Ruled by law.’”Footnote 36 At the other end of Linneaus’ typology were Africans, a group the Swedish scientist described as “sluggish, lazy … crafty, slow, careless. Covered by grease. Ruled by caprice.”Footnote 37 Linneaus’ student, Peter Kalm, while expressing regret at enslaved Americans’ subordinate position, also wrote about the enslaved kept in “their heathen darkness” in 1756.Footnote 38

Building on Linneaus’ and Kalm’s work, German anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in 1776 differentiated between races on account of the shape of the skull while Olof Erik Bergius, who had been an official in the Swedish West Indian colony St. Barthélemy, in 1819 published a book where he clearly demarcated Black and white people. The former was destined for servitude and would gain “bildung” (edification or enlightenment) through interaction with the white people who were destined to rule.Footnote 39 Additionally, Anders Retzius, a prominent Swedish scientist who was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy and in 1842 “introduced the cephalic index” linking race to skull size, knew and corresponded with German-born scientist Lorenz Oken, who in 1807 created a racial hierarchy based on senses (Black people who were associated with “touch” at the bottom and white people associated with “vision” at the top of Oken’s five races) and was inducted into the prestigious Swedish society in 1832.Footnote 40

Retzius also corresponded often with Samuel George Morton, the founder of American physical anthropology, “about their mutual interest in craniometry.”Footnote 41 Morton’s views were influential and his “measures of cranial capacity placed Europeans on top with the largest capacities, Africans at the bottom and Asians in between.”Footnote 42 While Retzius early in his career criticized phrenology – later recognized as a pseudo-science based on skull measurements – Morton in his book Crania Americana included a section on phrenology’s relationship to anthropology and helped legitimize perceptions of Black inferiority.Footnote 43

While it is difficult to ascertain the extent to which culturally infused ideas of race and scientific racism impacted the general Scandinavian population, there are important examples of the cultural, social, and political elite being familiar with scientific explanations and the storytelling used, directly and indirectly, to undergird slavery in both the Old and the New World.

Among the prominent Scandinavians to demonstrate interest in, and knowledge of, the scientific currents of the day – and their ramifications in terms of race relations – was renowned Swedish writer Fredrika Bremer. During her travels around the United States between 1849 and 1851, Bremer, who was greatly interested in educational matters and regularly commented on issues of race, described Linneaus and Benjamin Franklin (along with Isaac Newton), as “heroes of natural sciences.”Footnote 44 Bremer also expressed interest in phrenology and wrote favorably about the relocation of the formerly enslaved from America to Africa. While the connection between Bremer’s admiration of Linneaus, belief in phrenology, and support for colonization are not in themselves a direct link between Old World racial ideology and its expression in the New World, they do help explain Bremer’s admission that “I can not divest my mind of the idea that they [negro slaves] are, and must remain, inferior as regards intellectual capacity.”Footnote 45

Bremer published her thoughts on race relations in the United States in 1853, but, as we have seen, expressions of racial hierarchies were prevalent among the Europeans engaged with Atlantic World slavery decades earlier. Moreover, despite the physical distance between Denmark, Western Africa, and the Caribbean, there was no denying slavery’s larger societal impact in Scandinavia and its positive economic impact on Nordic maritime cities in the years leading up to 1849. Both in terms of the material wealth that slavery created and in terms of its cultural imprint, slavery directly and indirectly impacted life in major Scandinavian cities and, as Pernille Ipsen has argued, infused life in a city like Copenhagen with a sense of “colonial haunting.”Footnote 46

In Denmark, Hans Christian Andersen’s play Mulatten (The Mulatto), which was set in the French West Indies, debuted on the Royal Danish Theater’s stage in Copenhagen in 1840. At this time, the Danish abolitionist movement was still in its infancy, but the play – and the success it enjoyed – indicated Andersen’s awareness of slavery’s impact on Europe’s slaveholding nations while simultaneously revealing some of the racial stereotypes that helped legitimize slavery from a white European perspective.Footnote 47

By consciously situating his play on Martinique, Andersen likely helped his elite Copenhagen audience maintain the perception that Danish colonial slavery was qualitatively different from French colonial slavery, an argument that fit into Grundtvig’s view of “benign” Danish slave rule, while avoiding having his play comment explicitly on contemporary monarchical politics, in which the royal court along with Danish merchants for years had been intimately tied to the colonial goods flowing from the West Indies.Footnote 48

Moreover, Andersen understood the racial stereotypes that would make his play legible and perhaps even credible to an elite Scandinavian audience. Playing on fears of slave uprisings, Andersen made the half-naked former slave Paléme a central part of his play. Describing plans for a future slave rebellion, Paléme appeared in the first scene of Andersen’s second act, sipping rum from a coconut (which he in Andersen’s imagination had been nursed on), before proclaiming “in blood and fire everything shall perish.”Footnote 49

Slaves, or former slaves, of African descent – half-naked, and perhaps by implication closer to nature, hard-drinking, and vengeful – were part of the stereotypes that helped maintain legal measures to keep the enslaved population and freedpeople under control and part of the stereotypes that shaped attitudes toward Africans in Europe in the decades leading up to the Civil War.Footnote 50

By being somewhat removed from the influence of the Danish state church and the political establishment, Grundtvig, David, and Raffard were able to set themselves apart from more “establishment” ideas of slavery and race relations in their concrete and active efforts to abolish slavery. In this small abolitionist circle, Grundtvig played an important part, and Claus Clausen on his way to America in April 1843 received concrete anti-slavery inspiration from the pastor that he considered “the North’s spiritual high priest” as he attended several of Grundtvig’s Easter sermons together with his wife Martha.Footnote 51

On Maundy Thursday, April 13, 1843, at a time when he had been working actively for slavery’s abolition for four years, Grundtvig preached on his belief in a common humanity.

[Humankind, originating from the same set of parents, was considered] as children of one blood as Christianity otherwise could not be extended to all people under the heavens, for wherever it comes to black or white … it follows that all of mankind both can and shall be of one blood.Footnote 52

Grundtvig’s Protestant Christian ideas, and his earlier expressed view of slavery’s sinfulness, were part of the ideological inspiration that Clausen carried with him to America – ideas with important implications for discussions of citizenship. If one followed Grundtvig’s conviction that slavery was sinful and “all of mankind of one blood,” then people “black or white” would deserve equal rights. Grundtvig’s ideas about Christianity and slavery – and his history of state-church criticism – would therefore continue to play a part in Claus Clausen’s own anti-slavery struggle in the New World well into the 1860s. While Claus Clausen initially devoted himself to religious matters in America, it became increasingly clear, as more Scandinavian immigrants arrived in the region, that this Danish “disciple” of Grundtvig was more forceful in his denunciation of slavery’s sinfulness than his state church–affiliated colleagues but also served as one of many individual examples connecting ideas of landownership, liberty, and colonialism.

A “very severe epidemic” raged through Muskego during the winter months of 1844.Footnote 1 According to Sören Bache, somewhere between seventy and eighty men, women, and children were carried “to their graves,” and Claus Clausen’s role in the community was thus highlighted in tragic fashion as he conducted more than fifty funerals in a community of 600 people within his first five months in the United States.Footnote 2

The heartbreak led several immigrants to send what Bache described as “ill-considered letters” to family and friends back in Norway portraying life in the United States unfavorably and complicating the early settlers’ hopes of creating a steadily growing and thriving community in Wisconsin. To counteract the negative stories, the Muskego settlement leaders jointly wrote an open letter which appeared in the Norwegian Morgenbladet (Morning Paper) on April 1, 1845. According to the settlers’ religiously infused worldview, the current hardship was God’s will, but the Lord also gave reason for optimism:Footnote 3 “God has made it more convenient to produce human food in America than perhaps in any other nation in the world,” the authors noted.Footnote 4 Moreover, foundational American ideas set the New World apart from Scandinavia. “We make no pretense about acquiring riches, but we are subjects under a liberal government in a bountiful country where freedom and equality rules in religious and civic matters.”Footnote 5

Liberal government, freedom of religion, equality in societal matters: such ideas had resonated in Scandinavian communities for years and would continue to do so for decades. To Scandinavian immigrants, the concepts of liberty and equality, closely tied to ideas of American citizenship and prospect of landownership, were simple and alluring at a time when Old World opportunities seemed increasingly precarious due to population growth (which kept wages down), large landholding estates, emerging industrialization, and few opportunities for political influence to alter socio-economic conditions.Footnote 6

Thus, America’s relatively cheap and seemingly abundant land, secular ethnic newspapers free of censorship, freedom to support non–state-church pastors, and concrete civic participation through voting or eventually running for office, were significant factors for Scandinavians contemplating emigration in the antebellum era.Footnote 7

“Everything is designed to maintain the natural liberty and equality of men,” Ole Rynning had written in his True Account of America from 1838.Footnote 8 In Rynning’s text, the allure of “liberty and equality” and the accompanying opportunities were central, but the author also made clear that important regional differences guided economic prospects. American democratic ideals were undermined by “the disgraceful slave traffic.”Footnote 9 Slavery, according to Rynning, constituted a “vile contrast” in a country which could otherwise rightfully be proud of its foundational values.Footnote 10 Rynning’s subtitle specifically indicated that he wrote for “peasants and commoners,” and the Norwegian author thus described conditions in the South in terms legible to readers who had likely never seen nonwhite people outside of Norway.Footnote 11 In the South, Rynning wrote, “a race of black people with wooly hair on the head called negroes” suffered from their masters’ violence, and slavery was driving a wedge between the North and the South, which could likely soon lead to “a separation between the northern and southern states, or else bloody civil disputes.”Footnote 12

Rynning’s argument for settling in the Midwest rested partly on morality, but there was an implicit economic argument about immigrant prospects in the North as opposed to the South as well. As Ole Rasmussen Dahl later noted in a letter to his brother in Norway, the American experience had shown that “a free laborer” could never sustain himself “among slaves.”Footnote 13 Dahl’s description was somewhat hyperbolic, but opportunities for economic uplift, as Keri Leigh Merritt has demonstrated, were indeed scarcer in the South, as “wage rates were lower in areas where slavery thrived.”Footnote 14 Where New England farm laborers in 1850 “could expect to earn $12.98 per month,” similar work in Georgia would yield $9.03 and even less in South and North Carolina.Footnote 15

Other Scandinavian travel writers, whether recommending Wisconsin, Missouri, Louisiana, or even Texas, also grappled with the difference between North and South, but all connected landownership to a sense of liberty uniquely attainable in America.Footnote 16 In a lengthy guidebook and letters to Norwegian newspapers, Johan Reymert Reiersen, for example, explicitly argued for landownership as a natural and religious right for civilized, white people such as Scandinavians.Footnote 17 In Reiersen’s view, “the red man” was monopolizing more land than consistent with humankind’s general welfare, and he therefore supported “civilized” settlers taking land from “barbarians” until the nation was linked from coast to coast.Footnote 18

The paradox between landownership as a natural right for humankind, in Reiersen’s view equated with civilized, white people, and American Indians’ lack of right to the land they inhabited was maintained by most Scandinavian writers through a belief in white superiority. While Reiersen admitted that “negro slavery exists in Texas,” he did not reflect on its economic implications for immigrants but mainly presented slavery as a source of regional conflict over expansion and political power: “Liberty seems absorbed with the mother’s milk and appears as indispensible for every citizen of the United States as the air he breathes,” Reiersen claimed.Footnote 19 In this manner, Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish settlers, along with other European immigrants, were able to take advantage of American citizenship, enter into politics, and in the process, according to Jon Gjerde, “became among the most vociferous advocates of a herrenvolk republic.”Footnote 20 Racial ideology and economic opportunity were closely linked to land claims.

In his guidebook, Reierson – articulating central elements of the threshold principle – expressed admiration for the United States’ ability to grow both population and territory without succumbing to the small-state rivalries that had often characterized the European continent. “[The country] has maintained its political unity, multiplied its population, expanded its trade to all corners of the world, continued its system of domestic improvements and opened a wide, almost limitless field for individual enterprise,” Reiersen marveled.Footnote 21 Hence, prospective Scandinavian immigrants in the 1840s had a choice between the newly admitted nonslaveholding states in the Midwest, the slaveholding state of Missouri, which was popular among German immigrants, and the deep South.Footnote 22

For Claus and Matha Clausen, the choice rested on personal relationships, religion, and economic prospects. The couple arrived in Muskego, an important Scandinavian social hub and stepping stone, on August 8, 1843.Footnote 23 After receiving his ordination, Clausen preached first on colony leader Even Heg’s farm, known as “Heg hotel,” and later in a log church before relocating in 1846 to accommodate Johannes W. C. Dietrichson, an “official representative of the Church of Norway.”Footnote 24

Claus and Martha Clausen moved to Rock Prairie in the southern part of Wisconsin in 1845. The couple, who had lost a newborn son in the spring of 1844, welcomed another son into the world in the spring of 1846, but shortly thereafter tragedy struck again.Footnote 25 Martha Clausen, “well and cheerful” when Claus Clausen left to visit a neighboring congregation on November 7, became critically ill with pneumonia, and her husband only barely made it back for a final goodbye early on Sunday, November 15.Footnote 26 In a letter dated December 7, 1846, demonstrating the close transnational ties maintained even three years into their migration, Claus Clausen described the heartbreak to Martha’s brother in Denmark, and the relatives stayed in touch subsequently.Footnote 27 Less than a year after Martha’s death, her brother and other community members from the island of Langeland wrote to Claus Clausen asking him to elaborate on conditions in America and perhaps nuance some of the ideas about liberty and equality appearing in Old World emigration pamphlets.Footnote 28

The prospective emigrants’ inspiration came from at least two sources published in 1847. Laurits J. Fribert’s ninety-six-page Haandbog for Emigranter til Amerikas Vest (Handbook for Emigrants to America’s West) served as a source for a shorter, widely circulated, second pamphlet, published by Rasmus Sörensen in Denmark later that same year.Footnote 29

During his time in the United States, Fribert, who settled among Swedish immigrants in Wisconsin in 1843, researched American citizenship requirements that he, based on the 1802 naturalization act, explained as the ability to demonstrate “good moral character” and adhere to the “principles of the Constitution.”Footnote 30 Fribert clearly did not have to worry about his skin color and instead emphasized the importance of immigrants renouncing any “hereditary title” and concluded by detailing the differences between state citizenship and national citizenship:

Only according to the above-mentioned conditions can complete American citizenship be attained according to the laws of Congress, but this does not prevent individual states from conferring citizenship in said state on less strict conditions … In Wisconsin, which is a territory and not yet a state, and therefore cannot make its own provisions in this regard, the above-mentioned general laws of the United States apply.Footnote 31

Fribert’s notes on emigration and citizenship sparked Sörensen’s pamphlet which also offered its own ideas of citizenship’s rights and duties.Footnote 32 Sörensen recognized the discontent among landless laborers and tied these to much larger European discussions in the years leading up to the 1848 revolutions.Footnote 33 According to Sörensen, Scandinavian farm workers faced many of the same issues that had led to “the large English, German, and France emigrations to America.”Footnote 34

In a three-page introduction, Sörensen argued that “the fatherland” had to provide material goods necessary for sustenance for all or risk seeing its younger generations emigrate. If all that was left for landless children, after their parents’ estate had been settled, were the duties associated with subjecthood of a Scandinavian monarch and none of the basic economic rights, a house and land to obtain sustenance from, then everyone – king, country, and prospective emigrant – were better off by letting young people explore opportunities across the Atlantic. The highest expression of one’s affection for the fatherland, even higher than nationality, language, faith, and self-sacrifice in wartime, was the love of fellow man, Sörensen proclaimed.Footnote 35 This love had to be expressed by “allowing and affording one’s neighbor the same worldly goods as one, under similar circumstances, would want allowed and afforded by him.”Footnote 36

Fribert and Sörensen both had concrete experience with the small Danish islands where Clausen and his wife had lived before emigrating and therefore knew firsthand about the recurring issues regarding lack of land availability. Their writings therefore resonated with a wide swath of smallholders.Footnote 37

Rasmus Sörensen’s publication “inspired several” members from Martha Clausen’s childhood community to travel to “this Canaan’s land,” and as a consequence her brother wrote to Claus Clausen asking about conditions in America.Footnote 38 Perhaps still grieving, Clausen’s response was gloomy. “Seldom have I seen more misleading nonsense,” the widowed husband replied in response to the emigration pamphlets.Footnote 39 Clausen was upset that Fribert and Sörensen, in his view, had provided too rosy a picture with their information on travel costs, harvest yields, and disease.Footnote 40 The Danish-born pastor worried that these descriptions now roused the America fever in Scandinavia and might “entice people to injudiciously initiate such an important step as emigration.”Footnote 41 Not all which “glistens in America” is gold, warned Clausen.Footnote 42

Clausen went on to offer advice on climate, land, and emigration practicalities in such detail that his response took up the majority of two newspaper issues. Toward the end of his letter, Clausen did concede, however, that there was no shortage of “good laws or sufficient civic order and safety for the quiet, honest, and diligent citizen in all things regarding his worldly welfare.”Footnote 43

Clausen’s letter was revealing as it demonstrated Scandinavian emigrants’ concern with landownership and the Danish-born pastor’s concrete knowledge of these concerns.Footnote 44 Additionally, Clausen, albeit without reflecting on whiteness’s importance, equated productive citizenship in the United States with honesty and hard work that in turn could lead to socioeconomic progress for younger Scandinavian men and women.Footnote 45 The latter point was also made by Danish-born Peter C. Lütken of Racine, Wisconsin, when he in March 1847 wrote a piece on the connection between landownership and freedom that was published in a trade journal in Denmark the following year.

The truth remains that the soil here rewards its faithful cultivator and that one in all essentials enjoys the full fruit of one’s labor; for taxes do not oppress, and if a man is here in possession of his property free of debt, then no one on earth can be more independent and more free than him.Footnote 46

Liberty and equality were recurrent themes, both implicitly and explicitly, in the emigration literature. Fribert, for example, in a section titled “Everyone should go to Wisconsin” pointed out that because of slavery, with its important implications for labor relations and pay, it was “not as honorable to work for the white man, whom many wealthy men will not regard higher than a black man.”Footnote 47 In short, economic concerns, landownership, and the institution of slavery remained the most important reasons for settling north of the Mason–Dixon line. Settlement patterns reflected the emigration pamphlets’ advice. When the 1850 census was taken, only 202 Scandinavian-born immigrants were counted in Texas and just 247 in Missouri, while 12,516 Scandinavian-born immigrants lived in Wisconsin and Illinois.Footnote 48

In the Midwest, emigrants found the added security of living among fellow Scandinavians, and, starting in the late 1840s, thousands of young, white, Protestant Scandinavians (their average age was around thirty) pursued the promise of equality through landownership close to the Great Lakes.Footnote 49 Yet, Midwestern landownership, as most Scandinavian-born immigrants at least tacitly admitted, was predicated on the fact that the “Indian hordes” through “deceit and force” had been removed.Footnote 50

***

The first newspaper published in Wisconsin by Scandinavian immigrants was Nordlyset (The Northern Light).Footnote 51 In the inaugural issue on July 29, 1847, Nordlyset’s editors emphasized their attempted neutrality in political and religious matters and stated the newspaper’s aim as elevating “ourselves, in regards to our nationality, among our surroundings,” by enlightening and guiding its readership in order to achieve equality at the level of fellow citizens. The first step to achieving political enlightenment among the Scandinavian readers was a translation of the Declaration of Independence.Footnote 52 From a Scandinavian immigrant perspective, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights provided the vision and legal foundation to ensure economic opportunities in the New World. Thus, in addition to the implicit and explicit recognition of citizenship’s importance, it was pointed out, again and again, in the pamphlets and letters flowing back to Scandinavia that “the United States has no king.”Footnote 53

When adopted on February 1, 1848, the first two sections of Wisconsin’s State Constitution echoed the Declaration of Independence and specifically outlawed slavery as well as “involuntary servitude.” Moreover, in section 14, feudal tenures were prohibited, and section 15 specifically ensured that “no distinction shall ever be made by law between resident aliens and citizens, in reference to the possession, enjoyment or descent of property.”Footnote 54

Thus, with the Wisconsin Constitution in hand, immigrants in the early Scandinavian enclaves could distance themselves from Old World feudalism and pursue their dream of landownership, confident in its legality and ties to ideals of liberty and equality.Footnote 55 As such, Scandinavian immigrants were quickly able to enjoy the fruits of American citizenship, and in the process they generally supported an expansion of American territory, especially if the population therein was mainly white.Footnote 56

In the midst of the American war against Mexico between 1846 and 1848, Nordlyset, under Norwegian-born editor James D. Reymert, initially expressed support for manifest destiny by declaring that “a strong United States was probably destined to annex the enemy’s territory.”Footnote 57 Under its second editor, Even Heg, however, Nordlyset nuanced its position on territorial expansion based on ethnic considerations and on March 10, 1848, deemed it inadvisable to annex any further territory from Mexico as this would mean incorporating additional “half-civilized inhabitants” into the United States.Footnote 58 The same hesitation to annex Cuba, based on a sense “that a people of mixed blood, mainly Negro and Spanish, could not readily be assimilated,” was expressed by American politicians and the Norwegian immigrant papers in the 1850s and appeared again in the following decade.Footnote 59

Heg’s quote, and the sentiments expressed in subsequent ethnic newspapers, underscored the importance of whiteness among Scandinavian immigrants. Importantly, both Reymert and Heg – by settling in Wisconsin, on land formerly occupied by Native people – were actively partaking in the expansion of American boundaries.

In the Midwest, as Stephen Kantrowitz has shown, “Wisconsin’s 1848 constitution” and those of other Midwestern states encouraged the dissolution of American Indians’ collective affiliation, and white settlers, whether in Wisconsin, Kansas, Michigan, or elsewhere, “quickly abetted outright dispossession, aided by unequal tax policies and official tolerance of white squatting.”Footnote 60

As Scandinavian editors started to voice their opinion on American public matters for their fellow countrymen in the ethnic press, it became increasingly clear that they, along with other European immigrants, were solid supporters of a “white man’s republic.”Footnote 61

Andreas Frederiksen Herslev, who arrived in the United States in 1847 and adopted the name Andrew Frederickson, wrote home in 1849 and assessed the Mexican War’s consequences. According to Frederickson, the American military, based on volunteerism, tied into broader societal ideals where “the poor” had greater opportunity for equality and could “attain justice more or less as well as the rich.”Footnote 62 Still, some were more equal than others based on skin color, as exemplified by Frederickson’s ideas about land and the opportunities war service could provide.

Around the time Casper and I arrived, the government issued posters that able-bodied soldiers could receive 7 dollars a month and 160 acres of land which could be surveyed anywhere in the United States where there were unsold sections.Footnote 63

After the war, Frederickson bought two land warrants from Mexican War veterans and used the certificates to claim what he termed “free land” in Brown County, Wisconsin.Footnote 64 As was the case with Frederickson, Scandinavian immigrants often did not reflect explicitly on their role in the American expansion through land acquisition. Scandinavian immigrants did, however, often arrive in the United States with preconceived notions of American Indians partly due to literary texts. As Gunlög Fur has noted, James Fenimore Cooper’s “books were translated into Swedish and, already published in the 1820s, they became readily available for a reading audience to such an extent that Fredrika Bremer regarded him as one of ‘the first to make us in Sweden somewhat at home in America.’”Footnote 65

In 1847, Norwegian-born lawyer Ole Munch Räder, observing a forest fire in the Mississippi Valley, wondered if the local indigenous warriors would interpret the smoke as a “huge peace pipe of their great father in Washington or as war signals and spirits of revenge from the land of their fathers which they had to leave in disgrace to give place to the ‘pale faces.’”Footnote 66 Räder quickly added, “This expression by the way, I use only out of respect for Cooper’s novels; it is claimed that no Indian has ever called the whites by such a name,” but in the darkness the Norwegian traveller could not help his mind from wandering and imagining an encounter with an Indian “fully equipped with tomahawk and other paraphernalia, and of course on the watch for someone to scalp.”Footnote 67

Back in Wisconsin, Räder encountered bands of Pottawatomie returning from Green Bay, “where they had received the annual payment provided for in their treaty with the United States government,” and described their “features and their clothing” as somewhat akin to “our Lapps, although they were taller, more dignified, and also more cleanly” than the indigenous people living in northern Sweden, Norway, and Finland to which he compared them.Footnote 68

Still, the problem with the American Indians, according to Räder, was that they had “lost their old reputation for honesty,” which was part of the reason that people “generally despise and hate the Indians.” People in the western part of the United States, which Räder considered Wisconsin part of, “find it a great nuisance that the Indians never seem to accustom themselves to the fact that the country no longer belongs to them.”Footnote 69

Such tropes of American Indian presence and practice echoed regularly among Scandinavian-American writers. In 1845, the residents of Muskego praised the pioneers who “fought wild animals and Indians,” and Räder, while acknowledging that American Indians were subjected to “injustice” and that the laws passed for their protection were “never enforced,” nevertheless took it for granted that their Midwestern removal was just a matter of time.Footnote 70

Describing a treaty between the Chippewa and local Indian commissioners in August 1847, Räder wrote: “It is specified in the treaty that certain lands west of Wisconsin are to be abandoned in favor of a new territory, Minnesota, which is to be established there. To begin with, the Winnebago are to be placed there.”Footnote 71

In a different example, Hans Mattson depicted his first encounters with “Sioux Indians” positively but also wrote about a “war dance” that “in lurid savageness” exceeded anything he ever saw.Footnote 72 Moreover, Mattson’s countryman, Pastor Gustaf Unonius, who had founded the Swedish Pine Lake settlement in Wisconsin, described the Winnebago tribe as “the wildest and most hostile tribe of all the tribes that are still in this area.”Footnote 73 Unonius’ description was one of several that pointed to American Indians as uncivilized and thereby unfit for a place in American society. Within a decade, however, Scandinavian immigrants also settled in Minnesota and shortly thereafter on American Indian land in the Dakota territory. Thereby, Scandinavian immigrants often embraced the notion of independence, through fruitful contributions as land cultivators not wholly unlike Jefferson’s ideal of an economically and morally independent yeoman farmer, while maintaining support for a sizeable nation-state predicated on territorial expansion and Indian removal.Footnote 74

The Scandinavian definition of citizenship, closely tied to the dream of landownership, was fueled throughout Scandinavia by Räder, Rynning, Fribert, and Rasmus Sörensen’s descriptions of American liberty in the antebellum era.

While emigration pamphlets and America letters were secondary to political and economic conditions on the ground, they did, however, effectively juxtapose Old and New World conditions and opened new opportunities and concrete roadmaps to families seeking a new life across the Atlantic.Footnote 75 The “America fever” brought on by the emigration pamphlets and social conditions set off a chain migration to Wisconsin, where ideas of free soil and free labor soon became powerful political rallying cries among Scandinavian immigrants.Footnote 76 After 1847, first hundreds then thousands of Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes poured into the Midwest. By 1860, a total of 72,576 Scandinavians lived in the United States, with almost a third claiming Wisconsin as their home.Footnote 77

It was late August 1847 when Fritz Rasmussen’s parents left the island of Lolland along with their six children. Fritz’s father, Edward, decided to emigrate to America in pursuit of “liberty and equality,” which he found sorely lacking in Denmark.Footnote 1 The year before, one of the Lolland’s social reform leaders, C. L. Christensen, had also emigrated to America, and the reason was believed to be the Danish authorities’ harsh treatment of dissidents who advocated on behalf of smallholders and peasants.Footnote 2

By 1847, Fritz Rasmussen’s father was also engaged in political activity in opposition to the Danish authorities to such a degree that both political necessity and economic opportunity prompted his decision.Footnote 3 On Lolland, where the Rasmussen family resided, land shortage was acute. In one county, Maribo Amt, 87 percent of all land belonged to properties larger than 4.4 acres.Footnote 4 It was therefore no coincidence that Fritz Rasmussen, looking back from the vantage point of 1883, used the language of the oppressed and stressed the importance of emancipation:

He [Father], I afterwards came to understand, had to leave the Country, like many others, as a political refugee – : on account of his writings & doings, for and among the communalities, in regard to a more & thorough emancipation of the people generally, from the oppressive Sovereignty of the nobility.Footnote 5

Edward Rasmussen’s family emigrated on August 27, 1847, two months after Martha Clausen’s brother had written to Claus Clausen to ask about emigrant prospects in Wisconsin, but the family did not see Clausen’s cautionary letter.Footnote 6 Where Claus Clausen had been guaranteed employment at arrival, the Rasmussen family’s future was from the outset more precarious.

In Fritz Rasmussen’s account, the family stopped briefly in Hamburg (then a sovereign state in the German confederation), boarded the ship Washington, and arrived in New York City on October 26. From New York the family travelled to Albany where the recently constructed Erie Canal originated. A few weeks later they boarded the Atlantic in Buffalo to be transported over the Great Lakes to Wisconsin (see Figure 4.1). Only later did they realize their good fortune. One of the next ships that went west over Lake Erie and Lake Huron was Phoenix, a modern steamer named after the bird in Egyptian mythology. But in contrast to the legend, Phoenix never rose from the ashes in November 1847. Instead, hundreds of Dutch emigrants lost their lives in the flames or icy water on their way to a new Midwestern home.Footnote 7 “We were spared the suffering and catastrophe,” remembered Fritz Rasmussen.Footnote 8

Figure 4.1 Fritz Rasmussen, born on the island of Langeland, emigrated with his family to Wisconsin in 1847 and eventually settled in New Denmark.

While the Rasmussen family’s ship made it unscathed over the lakes, the family did not. Nine-month-old Henry died of disease shortly before they reached Milwaukee on a “cold, bleak” November day, and disease was ever-present. On the snow-covered wharf in eastern Wisconsin, survival more than enjoyment of liberty, equality, and champagne-filled springs was the main concern.Footnote 9 “No money and could not speak [the language] and no countrymen: Father sick unto death – and so my youngest sister and youngest Brother. This was a landing, opposite the gloriously golden and happy anticipation when leaving,” remembered Rasmussen.Footnote 10 But an older Danish sailor, in the United States known as Johnson, “solicited help and finally by evening got us carted off into town and sheltered in a small, poorly furnished tavern or restaurant, kept by a young German and his wife,” recounted Rasmussen.Footnote 11

At the German couple’s place, the family regained their strength somewhat. With the help of fellow Scandinavian immigrants, they – after a brief stay at the local poor house – slowly regained their collective footing. Their fourteen-year-old son Fritz was sent away to work for a newly arrived Norwegian shoemaker, and shortly thereafter a sizable group of approximately fifty Danish immigrants, inspired by Rasmus Sörensen’s emigration pamphlets and Claus Clausen’s letters, arrived.Footnote 12 By June 1848, the newcomers had established a settlement, which was later named New Denmark.Footnote 13

For six years, Fritz Rasmussen worked odd jobs in Wisconsin away from the small immigrant town, but in 1854 he returned, bought land, and soon started to keep meticulous records of major and minor events in New Denmark – not least land transactions.Footnote 14 In his thousands of surviving diary pages, Rasmussen on several occasions mentioned his acquisition of Section 24, N.E. ¼, S.E. ¼ in New Denmark, and the pride thus exhibited in landownership was in no small part tied to his family’s Old World experience.Footnote 15

Looking back later in life, Fritz Rasmussen reflected on his experiences in New Denmark in contrast to the Old World despite the hardship also encountered in Wisconsin: “We have come to this Country, where we are as free, previledged [sic] and no distinction – as to ‘Liberty and Equality’ of person – as the Nobles – so called – are in the lands where we came from.”Footnote 16

This idea – Old World nobility whose disproportional political power and landownership “restrained” the hard-working, honest, common man from achieving liberty and establishing his “pedigree” – defined Fritz Rasmussen’s worldview and, as we have seen, recurred regularly among early Northern European laborers.Footnote 17 While Rasmussen, consciously or unconsciously, benefited from his skin color and religion in terms of landownership and employment opportunities, his views on New World citizenship were not unlike those of the German forty-eighters, who, as Allison Efford Clark has shown, proposed “a nationalism based on residence, not race or even culture, and a form of citizenship grounded in universal manhood suffrage.”Footnote 18

Still, this ability to enjoy the fruits of one’s own labor, earning one’s own bread through one’s own sweat, was a key pull factor to Scandinavian immigrants and one made possible, in part, by whiteness.Footnote 19 When Catharina Jonsdatter Rüd, a Swedish immigrant maid making $2 a week and living in Moline, Illinois, wrote home in March 1856, she celebrated America and the individual liberty she experienced as a white woman:

Here the servant can come and go as it pleases her, because every white person is free and if a servant gets a hard employer then she can quit whenever she likes and even keep her salary for the period she has worked … A woman’s situation is as you can imagine much easier here than in Sweden and I Catherine feel much calmer, happier and more satisfied here than I used to do when I attended school in Nässjö. Everything in this country [seems praiseworthy] – to describe all benefits would take a lifetime!Footnote 20

Rüd underlined the word “white” and thereby proved herself aware, as Jon Gjerde has pointed out, that she enjoyed “freedoms that did not exist in Sweden or for nonwhite people in the United States.”Footnote 21 Since enslaved people in the United States were denied the fruits of their labor, Scandinavian-born laborers generally opposed slavery, with its parallels to the forced labor and serfdom which had been common in Denmark and Norway up until 1788. Unequal power and labor dynamics continued to exist in various guises in Scandinavia subsequently, and the Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish immigrants therefore arrived in the United States with suspicion of slavery’s extension or its beneficiaries’ political powers in the New World.

Thus, by the mid-1850s, the Republican Party’s ideology, what Eric Foner has termed free soil, free labor, and free men, meaning wage earners’ opportunity to become “free men” through landownership, aptly described a large swath of Scandinavian immigrants’ economic and social priorities and, by extension, their attraction to the Republican Party in the years surrounding the Civil War.Footnote 22

The issue of free soil was of central concern to Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes in the Midwest. With its importance for economic uplift and perceptions of liberty, land availability, in areas where slavery did not impact labor relations, played a significant part in shaping economic, legal, and moral positions in the Scandinavian-American immigrant community.

Yet, well-read Scandinavian immigrants such as Even Heg and his fellow early editors of Nordlyset, who had advocated legislation to prevent slavery from spreading into the territories between 1848 and 1850, in line with the Free Soil party’s platform, rarely extended their argument to advocate for nonwhite people.Footnote 23 In this regard, Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes were far from alone. As Henry Nash Smith observed more than sixty years ago, “the farmers of the Northwest were not as a group pro-Negro. Free-soil for them meant keeping Negroes, whether slave or free, out of the territories altogether. It did not imply a humanitarian regard for the oppressed black man.”Footnote 24

Smith might as well have added lack of humanitarian regard for American Indians. In their dismissal of Native peoples’ rights, Scandinavian immigrants, not least the better educated ethnic elite, differed from the central actors of the abolitionist movement who explicitly connected Indian dispossession to slavery’s extension.Footnote 25 In short, Scandinavian immigrants, over time, showed themselves to be passionate Republicans but not abolitionists.

During the late 1840s and early 1850s, with the Democratic Party, the Free Soil Party, and the Whigs all vying for the Scandinavian vote, it was not evident that these newly arrived immigrants would eventually side with what became the Republican Party’s platform, but it was clear that the majority of Scandinavians were primarily interested in free land and less in nonwhite free men despite their professed love of liberty and equality.Footnote 26

Despite his Old World abolitionist inspiration, Claus Clausen in 1852 attempted to find a golden mean politically as the first editor of Emigranten.Footnote 27 Clausen saw Emigranten’s mission in the New World as mobilizing its Scandinavian readership politically, not least in support of liberty and economic opportunity, and in the process he loosely aligned the newspaper with the Democratic Party while relegating discussions of nonwhite people in America to the margins.Footnote 28

In an opening editorial, written both in English and Danish, Clausen stressed the importance of embracing assimilation, which underlined the advantages enjoyed by the paper’s mainly Protestant, literate, and white readership who were generally shielded from nativist critique.

We sincerely believe that the truest interest of our people in this Country is, to become AMERICANIZED – if we may use that word – in language and customs, as soon as possible and be one people with the Americans. In this way alone can they fulfill their destination, and contribute their part to the final development of the character of this great nation.Footnote 29

This openness (and ability) to Americanize, based on both individual and broader public interest, made Scandinavian immigrants more politically acceptable to Yankee Americans otherwise attracted to nativist ideas well into the 1850s and slowly provided political prospects for Scandinavian candidates as well.Footnote 30 Emphasizing the political rights and opportunities associated with American citizenship, Clausen, in an editorial dated February 13, 1852, underlined the importance of “schools, churches, and other civilizing influences” necessary for achieving political influence in America and warned his readership against wandering “out into the wilderness as soon as the land is acquired from the Indians.”Footnote 31 Focusing solely on land development might lead to missed political opportunities, Clausen warned.Footnote 32

During the presidential election campaign of 1852, Emigranten, under the editorship of Clausen’s successor, Charles M. Reese, explicitly supported the Democratic candidate Franklin Pierce at the national level but encouraged the paper’s readership to support Scandinavian candidates in local elections for the state legislature regardless of political party.Footnote 33

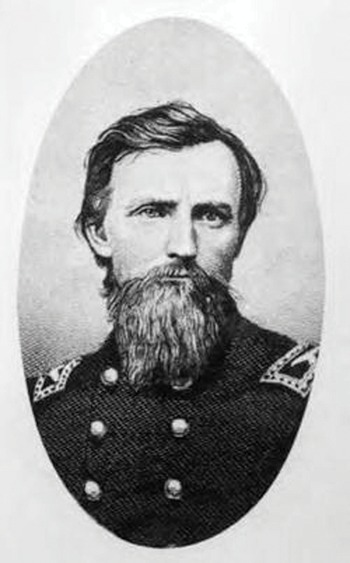

One such candidate was Hans Heg, the twenty-two-year-old son of Even Heg. Hans Heg ran for the Wisconsin State legislature on a Free Soil platform out of Racine in 1852 but – partly due to the fact that Scandinavian immigrants still made up less than 10 percent of Wisconsin’s foreign-born population in 1850 – lost narrowly to a Democratic candidate.Footnote 34

Yet, as the Whig and Free Soil Party morphed into the new Republican Party in the wake of the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act, the new political alliance, based on a strong commitment to free labor ideology, free soil, and, in time, a strong anti-slavery platform, increasingly appealed to Scandinavian immigrants.Footnote 35 By November 3, 1854, Emigranten, now edited by Norwegian-born Knud J. Fleischer, stated the paper’s position as being firmly in support of the Republican Party:Footnote 36

The November 7 election day is upon us!

Then it will become apparent if wrong shall conquer right, good conquer evil, if slavery shall be expanded and supported, liberty suppressed and curtailed! The Republican Party fighting for liberty and right has risen up to fight the “Democratic” Party’s friends, the defenders of slavery. Norsemen, you would not [want] the advance of slavery!Footnote 37

Emigranten conveniently ignored any lingering Republican nativist sentiment left over from the locally successful Know-Nothing party in the 1854 elections and tried to shift readers’ focus.Footnote 38 By the summer of 1855, Fleischer was urging “Norwegians to work for the Republican platform,” as in his opinion there “prevailed a vicious alliance of antiforeign Know-Nothing enthusiasts and unrighteous ‘slavocrats’” in the Democratic Party’s ranks.Footnote 39

Thus, Emigranten, which had for its first two years maintained an affiliation with the Democratic Party, as evidenced by Reese’s endorsement of Pierce in the 1852 election, adjusted its position based on the debate over free soil and, by extension, nonwhite free men, in part due to the impact slavery had on labor relations. From 1855, with the Republican Party gaining strength on the ground in Wisconsin, Emigranten aligned itself clearly with the anti-slavery party and urged Scandinavian immigrants to do the same.Footnote 40

By 1855, even openly Democratic newspapers such as Den Norske Amerikaner (The Norwegian American) made anti-slavery arguments. Den Norske Amerikaner pointed out that slavery had been “the main theme” in American politics since 1850, and in a front-page piece titled “Negerslaveriet og fremtiden” (“Negro Slavery and the Future”) the editor argued that the conflict between slavery and freedom had the potential to break the United States into pieces.Footnote 41 Expansion of slavery into the territories, it was argued, “would paralyze all political power in the northern states and make them a sort of commercial appendix to the all-commanding slave oligarchy” where free labor was subjugated in relation to “a profitable and advantegous monopoly.”Footnote 42 Perhaps worst of all, slavery’s sinfulness was being ignored in the South, and when Northerners pointed this out, “they point to their slaveholding clergy and slaveholding churches, with their prayers, awakenings, and the entire mechanism of a hypocritical religion.”Footnote 43

Starting with the Republican Party’s grassroots organizational activity in 1854 and supported by amplified anti-slavery advocacy in the Scandinavian press in 1855, the Scandinavian immigrant community became increasingly aware of slavery’s economic and moral implications on life in America. If the future United States could only be built on free soil, free labor, and free (but not necessarily equal) men, then Scandinavian-born agricultural laborers were willing to support the Republican Party’s political project in ever-increasing numbers.

When the Republican Party’s foot soldiers started to fan out over the Midwest to influence local, state, and national elections, they also helped shape opinions in Scandinavian immigrant enclaves. Andrew Fredrickson in 1861 remembered the middle of the 1850s as a politically formative period, where “the Republican Party, of which I am part,” was created.Footnote 44 Also, Celius Christiansen in his memoirs specifically remembered an 1854 visit to New Denmark by a representative of the Republican Party which he – along with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s bestselling novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin and a bribe of two dollars to vote for De Pere as Brown County’s county seat – credited with cementing his anti-slavery views in support of the Republican Party.Footnote 45

With the help of Norwegian leaders such as Hans Heg (see Figure 4.2), Emigranten’s agenda-setting ability on behalf of the Republican Party, and the canvassing and bribery experienced by immigrants such as Celius Christiansen, Scandinavian immigrants were slowly but surely primed through political campaigns and editorials to support the Republican Party.Footnote 46 On July 11, 1856, Scandinavian anti-slavery sentiment was concretely tied to support for the Republican Party when a broadside from the Republican state central committee was distributed by Emigranten in Norwegian. “The Union’s current political battle is the conflict between liberty and serfdom,” read the proclamation’s first paragraph, in language that closely mirrored the phrases used by Scandinavian immigrants themselves.Footnote 47

The Central Committee’s plea for Republican presidential candidate John C. Fremont went on to emphasize the fact that it was not trying to influence “the Scandinavians or other adopted citizens to do anything other than what any good and informed Christian would recognize as right” and additionally distanced the party from the “despised Know-Nothingers.” In conclusion, the Republican committee added, “everyone who in his heart hates slavery will vote for Fremont.”Footnote 48 In other words, any anti-slavery, pro-free labor, enlightened Christian immigrant could safely support the Republican Party going into the 1856 election.

The link between religion and anti-slavery sentiment was an important one. The abolitionist movement had long and deep ties to religious factions, such as the Quakers and Puritans, arguing, as did Grundtvig and Claus Clausen among others, for a common humanity.Footnote 49 On June 10, 1857, Nordstjernen (The North Star), a newly established “National Democratic Paper” within the Scandinavian-American public sphere explicitly linked free soil, popular sovereignty, and religion in its opening editorial but implicitly admitted the difficulty of defending “popular sovereignty” and the resulting violence in western territories to a Scandinavian audience.Footnote 50 While admitting that bands of bandits, who “happened to vote the Democratic ticket,” had crossed into Kansas and committed violent acts against settlers, Nordstjernen’s editor attempted to shift the responsibility to abolitionist agitators.