1. Epistemic relativism: the ghost from feminism’s past?

Feminist epistemology and epistemic relativism have a long history. Ever since the situated knowledge thesis gained intellectual traction in the 1970s and 1980s, feminist scholars have been accused that their philosophies entail “relativism.” Usually, relativism remains underdefined in both criticisms of the situated knowledge thesis, as well as attempts by feminist scholars to demonstrate that their position does not entail epistemic relativism (e.g., Crasnow Reference Crasnow2014). In these scenarios, epistemic relativism is often equated with the “equal validity thesis,” described as the position that “there are many radically different, yet ‘equally valid’ ways of knowing the world, with science being just one of them” (Boghossian Reference Boghossian2007, 2). In his influential Fear of knowledge, Paul Boghossian names feminist epistemologies prime examples of schools of thought that accept the equal validity thesis (Reference Boghossian2007, 6). In addition to “equal validity,” epistemic relativism is also equated with the “renunciation of judgment,” the stance that it is impossible to judge between different knowledge systems.Footnote 1

Whereas most feminist epistemologists aim to demarcate their position from epistemic relativism, attempts have also been made to reconcile them both (Code Reference Code1995; Ashton Reference Ashton2020). Such defenses rest on careful examinations of whether certain characteristics of each position are mirrored in the other (Ashton Reference Ashton2020). While I believe some commonalities have been successfully shown, emphases or policies are certainly different to a degree, so it might not make sense to talk about one position entailing the other after all.

Both positions nevertheless share certain value judgments. For instance, both oppose the (hegemonial) “absoluteness” of knowledge claims. Also, while within both thought traditions there is no unanimity regarding the issue, many proponents of epistemic relativism and feminist epistemology problematize the idea of notions such as “objectivity,” “reason,” or “rationality” construed independently of knowers. Thus, while not identical, both positions could draw important inspiration from each other.

Besides these more general observations, recent works by Kristie Dotson on the modes of epistemic oppression bring forward another potential commonality between card-carrying epistemic relativists and some representatives of feminist epistemology—the notion of the “epistemic system.” This notion is usually understood as a key concept within the epistemic relativism literature, where most ideas are articulated around the postulation of multiple, mutually exclusive epistemic systems over which only system-dependent judgment is possible (e.g., Kusch Reference Kusch2019). The epistemic relativism literature however, even though heavily relying on the concept, is astonishingly thin when explicitly defining what epistemic systems are, the most common notion being that epistemic systems are sets of epistemic principles that sanction belief (e.g., Seidel Reference Seidel2014). Dotson’s account, situated within the feminist epistemology literature, provides thus important new insight into what epistemic systems are as well as characterizing the oppressive processes within an epistemic system (Reference Dotson2014).Footnote 2

This paper aims to bring Dotson’s account of epistemic oppression and the sociology of scientific knowledge (SSK) as a representative of the epistemic relativism literatureFootnote 3 into dialogue through the notion of the epistemic system. I will not do that on an “abstract” level, examining similarities and differences, but concretely explore how both approaches can contribute to each other regarding the concept of epistemic system. The article is structured in a somewhat back-and-forth way, trying to simulate a dialogue between both bodies of literature and examining step-by-step how they could fruitfully contribute to specific debates situated in one or the other field, respectively.

First, I will criticize the current state of the epistemic relativism debate, arguing that the notion of epistemic systems is highly idealized and misses important social and political aspects that (necessarily) constitute epistemic systems. Having argued that epistemic systems might generate knowledge imbalances, I will explore how knowledge imbalance, epistemic power, and epistemic oppression are related. I shall then use Dotson’s account of epistemic resilience and third-order epistemic oppression to illuminate further processes within epistemic systems that have so far been missed in the epistemic relativism debate. Following this, I confront Dotson’s claim that certain aspects of epistemic oppression are “irreducibly epistemic,” drawing from the theory of social controls by Mary Douglas and arguing for an SSK-inspired finitist account of principle-following.Footnote 4 I will conclude by offering some thoughts on how this work contributes to the relationship of epistemic relativism and feminist epistemology in general and what could be future points of fruitful encounters.

2. Idealizations of epistemic systems

The notion of an epistemic system is central in debates on epistemic relativism since, to formulate epistemic relativism, it is necessary to propose a plurality of different, mutually exclusive epistemic systems. Consequently, it is impossible to pass neutral judgment regarding which epistemic system is “better” or “worse.” Even though there are many definitions of epistemic relativism, and many are more extensive than the one provided below (see, e.g., Kusch Reference Kusch2019), I shall take Ashton’s (Reference Ashton2020) choice of three elements from Kusch’s (Reference Kusch2019) account as a characterization of epistemic relativism that will suffice my purposes in this article. While these elements might not be necessary and/or sufficient, they are the most important characteristics in play when philosophers discuss epistemic relativism:

-

(DEPENDENCE) A belief has an epistemic status (e.g., justified/unjustified) only relative to a system of epistemic principles.

-

(PLURALITY) There is (has been or could be) more than one such system.

-

(SYMMETRY) Different systems or bundles are symmetrical in that they all are:

(a) based on nothing but local causes of knowledge ascriptions (LOCALITY); and/or

(b) impossible to rank except on the basis of a specific system or bundle (NONNEUTRALITY).

Epistemic systems are thus usually understood as sets of epistemic principles (Boghossian Reference Boghossian2007; Seidel Reference Seidel2014; Carter Reference Carter2016) that sanction beliefs as justified.Footnote 5 Many critics of epistemic relativism level their criticism based on the fact that it might always be possible to find more “universal” principles, seemingly disparate principles of allegedly different epistemic systems are derived from, or instances of (Boghossian Reference Boghossian2007; Seidel Reference Seidel2014). However, these highly influential discussions of epistemic relativism leave out an important aspect of epistemic systems when discussing whether different epistemic systems exist or how encounters between epistemic systems work. It’s not abstract philosophical concepts—such as epistemic systems—that encounter each other, but rather epistemic agents. Thus it is only possible to identify epistemic principles by studying how epistemic agents apply these principles in concrete situations, since there is no accessible “codex” of “definite meanings” of epistemic principles inhabitants of an epistemic systems have access to.Footnote 6

Following an SSK-inspired reading of the relation of use and meaning, I posit that what an epistemic principle means depends on how it is used (Bloor Reference Bloor1997). A coin is not a coin by being a stamped metal disc, but “the important thing is how people regard it and employ it as a medium when interacting with one another. We must attend, not to the thing itself, … but the people who call that thing a ‘coin’” (Bloor Reference Bloor1997, 29). In a similar way, we must attend to the epistemic agents: what makes a principle a principle is explaining it and applying it, the principle itself sanctioning and enforcing such talk and use (Kusch Reference Kusch2004, 70; Barnes Reference Barnes1995; Bloor Reference Bloor1997). And, since there is no “codex” of “definite meaning,” knowing principles means knowing a finite number of instances of their correct application. Applying a principle in a new context thus requires judging the similarity between the current and past applications. But there is also no “codex” about how to make these judgments: they are inherently influenced by local contingencies (Kusch Reference Kusch2010).

The previous paragraph constitutes my first and rough attempt to spell out the finitist position I will take in this paper. In later sections, I will deal with this position more carefully. This section aims to highlight the shortcomings of current formulations of epistemic systems in the epistemic relativism debate. The first point is thus that the inherently social character of epistemic systems is rarely recognized. Since principle-following is a process that requires epistemic agents, it also follows that principle-following might not be stable across space and time but that there will be variations across epistemic agentsFootnote 7 that need to be accounted for to characterize an epistemic system. Therefore, an epistemic system is unsatisfyingly characterized by epistemic principles alone.

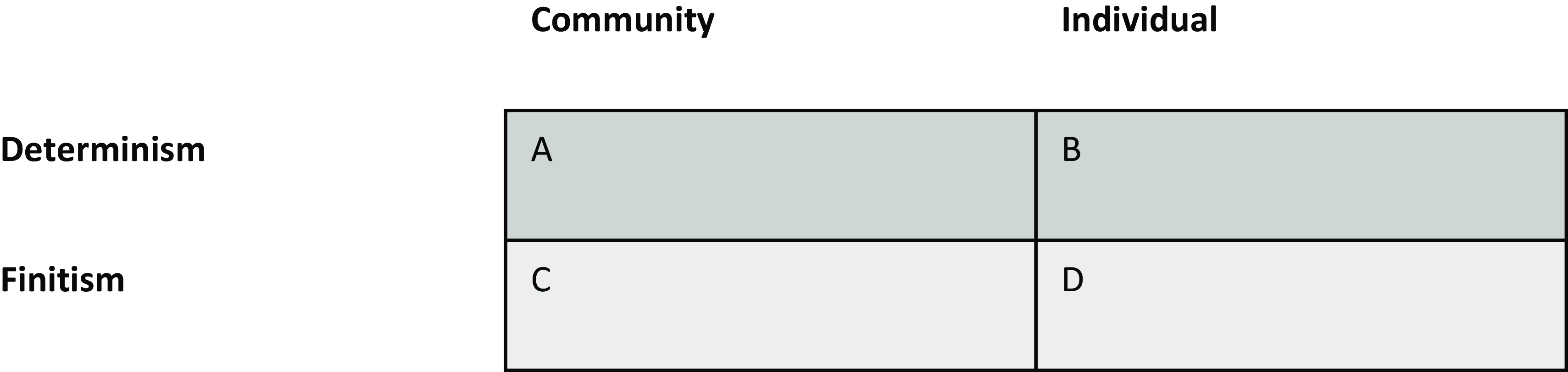

I, therefore, advocate for a new account of epistemic systems (see Figure 1). Whereas previous attempts to characterize epistemic systems can be characterized as epistemic principle-based accounts, I suggest an epistemic agent-based account. If one shifts the focus to epistemic agents emphasis lies on how epistemic agents act in certain situations. In these situations, epistemic agents have intuitions about the correct application of these principles. Whereas the epistemic principle-based account predicts stability—epistemic agents are members of an epistemic system by applying a particular principle in a particular way—the epistemic agent-based account predicts variation regarding applying principles within an epistemic system. As a result, it is impossible to distill epistemic principles that govern all epistemic agents—every distilled epistemic principle will be an idealization based on a limited number of instances of principle-following behavior.

Figure 1. Differences between the epistemic principle-based account and the epistemic agent-based account.

Influential accounts of epistemic systems hold that (socially isolated) individuals have uniform mental states about the correct application of an epistemic principle (quadrant B). The epistemic-agent based account holds that communities continuously make judgments about correct epistemic conduct through their heterogeneous intuitions about epistemic principles. There is no fixed epistemic principle “outside” or prior to social consensus (quadrant C). It might be possible for a defender of the epistemic principle-based account to grant that, if one looks at a community, there might be differences in intuitions about a (fixed) epistemic principle (quadrant A), but this concession would only be able to explain variation, but not change over time. Finally, an account of epistemic systems emphasizing individuals with no access to fixed episemic principles (quadrant D) has not yet been advanced.

There is, however, a second aspect of variation with regard to intuitions about epistemic principles that has so far not been addressed in the epistemic relativism literature. Some epistemic agents might apply epistemic principles less idiosyncratically than others. Some might be less flexible in interpreting and representing these principles. Some will guard certain principles more, and others might resist these principles more. David Bloor argues that institutions are never trusted completely, leaving room for different degrees of resistance concerning a certain principle. However, applying an epistemic principle in a way that might be regarded “deviant” by a majority of epistemic agents might put one in an epistemically disadvantaged position, and one’s standing as a good epistemic agent, someone with proficiency in applying epistemic principles, might be questioned. From such a situation, differences in epistemic power might emerge. Kristie Dotson characterizes epistemic power as the differential privileges concerning knowledge possession, attribution, and creation (Dotson Reference Dotson2018). Given the heterogeneity of intuitions about epistemic principles, certain individuals might be able to accumulate epistemic power, whereas others cannot and thus cannot participate in negotiating the principles of good epistemic conduct as well as what it means to be an epistemic matter (Dotson Reference Dotson2018).

These differences in epistemic power might thus lead to infringements of the credibility of certain epistemic agents, processes understood as discriminatory epistemic injustice (Fricker Reference Fricker2007, Reference Fricker, Kidd, Medina and Pohlhaus2017), a particular class of wrongs, that are fundamentally a form of discrimination (Fricker Reference Fricker, Kidd, Medina and Pohlhaus2017). Discriminatory epistemic injustice takes place when a particular speaker, for instance, is judged epistemically lesser because of prejudice. Discriminatory injustice involves the downgrading and disadvantaging of someone’s status as an epistemic subject.

But the stratified nature of epistemic systems might also lead to problems of access to and distribution of certain epistemic resources. Within an epistemic system there might be unjust obstacles to certain epistemic goods such as education or information. Such issues have been named distributive epistemic injustices (Coady Reference Coady2017). Fricker notes that she does not intend the distinction between “discriminatory” and “distributive” injustice to be a “deep” one, “since most cases of one will have aspects of the other. Not getting your fair share of a good will often be the cause and/or the result of discrimination of some kind.” (Fricker Reference Fricker, Kidd, Medina and Pohlhaus2017, 59, n. 1). She highlights, however, the distinct status of discriminatory epistemic injustice. While distributive injustice is an epistemic injustice too since epistemic agents are wronged in their capacity as epistemic subjects, discriminatory injustice is not about systemic riggings of the overall epistemic economy but a harm done to an epistemic agent (but see Anderson Reference Anderson2012).Footnote 8 In addition, injustice targeting epistemic personhood and injustice targeting the distribution of epistemic goods does not always have to go hand in hand (Symons and Alvarado Reference Symons and Alvarado2022). For instance, epistemic injustices can also be identified if there is no identifiable change with regards to material ressources. Sometimes, discriminatory epistemic injustices might even cause the alleviation of distributive epistemic injustices, if, for instance, unwarrantedly judging someone as a lesser knower (e.g., because of a certain stereotype) leads to sharing with them more resources (Symons and Alvarado Reference Symons and Alvarado2022).

In conclusion, power dynamics, discrimination, and the distribution of resources in an epistemic system are multifaceted processes. Given these processes and the consequential differences regarding epistemic power, epistemic systems are not only necessarily social but also political. These aspects have, however, been missing in many influential accounts accounts of epistemic systems in the epistemic relativism literature. Before I delve into how to politicize epistemic systems, I shall thus first conceptually relate knowledge imbalances, epistemic power imbalances, and epistemic oppression in the next section.

3. Knowledge, epistemic power, epistemic oppression

To understand how epistemic systems are oppressive, two concepts from the epistemic oppression literature will be helpful: epistemic status and epistemic high ground. Epistemic status means a positive assessment of one’s claims or ability to know something (Dotson Reference Dotson2018, 130–1). Epistemic status creates epistemic high ground for certain knowers: the ability to defend one’s claim and criticize others (Reference Dotson2018, 139). Importantly, epistemic status is a social status. One does not inherently possess knowledgeability, but knowledgeability is achieved through being recognized as knowledgeable (Bloor Reference Bloor1978). This status determines whether one has the ability to defend one’s claims or criticize those of others: social and political forces within an epistemic system can deprive certain members of their epistemic agency, “the ability to utilize persuasively shared epistemic resources” (Dotson Reference Dotson2014, 115) within a community of knowers to partake in knowledge production. Epistemic oppression is the process that deprives knowers of epistemic status and epistemic high ground; it is a persistent and unwarranted exclusion of certain epistemic agents from knowledge production (Dotson Reference Dotson2014). Applying the principles of an epistemic system to a particular knower is relational: If someone is judged credible, they are judged more credible than others (Medina Reference Medina2011). Similarily, if applying a principle a particular way determines knowledgeable groups, it also creates groups (relationally) not considered knowledgeable. Thus, epistemic principles of an epistemic system create stratification through their application.

When considering instances of knowledge imbalances in depth, it becomes clear that having more knowledge on a certain matter does not automatically correlate with accumulating epistemic power. Take the attainment of a standpoint as an example (e.g., Harding Reference Harding2009): the fact that certain individuals are continuously confronted with certain types of discrimination and thus might acquire a privileged position regarding access to knowledge concerning this process does not lead to epistemic power within the society that causes these types of discrimination. Of course, reaching a standpoint is empowering, but having more knowledge about a particular situation does not automatically lead to accumulating (epistemic) power regards that situation.Footnote 9 Thus it seems that a particular type of knowledge needs to be recognized as (important/desirable) knowledge so a power imbalance can emerge between those that possess it and those that do not. Being recognized as “important/desirable” knowledge is, again, a social achievement since it is conferred through the consensus of epistemic agents.

Note that not only the status of a particular type of knowledge but also the particular context matters. Take the example of a restaurant specializing in a particular type of cuisine. Usually, the customers will be regarded as less knowledgeable than the hosts, servers, or cooks about issues surrounding food, authenticity, preparation, etc. It would seem unintuitive, however, to argue that there is an imbalance in epistemic power guaranteeing restaurant personnel a superior epistemic position. The guest will not have as much epistemic agency within the restaurant-as-knowledge-system regarding particular issues concerning restaurant-related knowledge. But is this situation oppressive? No, not every power imbalance is oppressive. Recall that Dotson characterizes epistemic oppression as persistent and unwarranted. In the context of the restaurant, having less epistemic agency seems quite warranted. In addition, for this exclusion to become persistent, a substantial part of my epistemic life would have to revolve around this restaurant, which it highly likely does not.

Think of another example: the disagreement between a modern-day creationist and a modern-day evolutionary scientist—they disagree on whether the Bible is a good source for knowledge about the age of the earth (e.g., Pritchard, Reference Pritchard2011). I contend that dismissing the Bible as a good source of knowledge about the age of the earth is not epistemically oppressive. Most epistemic agents mobilizing such sources of evidence are from highly privileged backgrounds; they are often white, male, and wealthy … they have scores of epistemic privileges in other matters. And the Bible is not dismissed because these epistemic agents are white, male, or wealthy. Being dogmatic about the quality criteria of sources does not equal being epistemically oppressive. Structural background conditions are important in identifying instances of epistemic oppression.Footnote 10

But structural background conditions are not the only issue that needs to be considered when querying which power imbalances are oppressive. Take another example—the context of teaching. Teaching is a situation in which, most of the time, a particular individual possesses more knowledge and also a certain type of hierarchical relationship with those who would like to learn. This goes back to my first point: knowledge needs to acquire a certain status for an epistemic power imbalance to arise. But while there is both a knowledge and an epistemic power imbalance, teaching is usually not oppressive. One reason for this is that teaching situations are aimed at diluting knowledge imbalance and not maintaining it. Teaching can confer epistemic power, award the student the privileges of knowledge attribution, possession, and creation. Teaching confers knowledgeability. Thus, for an epistemic power imbalance to be oppressive, the context needs to be characterized by processes that aim to maintain or further deepen the imbalance.

In conclusion, the relationship between knowledge imbalances, epistemic power, and epistemic oppression is complex. It requires acknowledging the particular status of certain types of knowledge as well as the knowers, the (social, political, structural, etc.) context of the knowledge imbalance, and the presence or absence of measures to counter such imbalances. In short, while not every knowledge imbalance is a power imbalance and not every power imbalance is a case of epistemic oppression, every knowledge imbalance is potentially a power imbalance, and every power imbalance is potentially epistemically oppressive. Bringing these elements back together with my elaboration on intuitions about epistemic principles, one could propose the following model. Within an epistemic system, there will be variations concerning intuitions about certain epistemic principles. If the intuitions of an epistemic agent are different from “majority” intuitions, they might be regarded as “deviant,” and epistemic agents might be conferred a lower epistemic status. This will create a difference in epistemic power because the status of the knower and the status of certain types of knowledge she acquired through applying epistemic principles considered “deviant” will be infringed. They will have relatively little epistemic power. Situations where these differences in epistemic status are actively maintained and causally related to disadvantaged identities and certain intuitions about epistemic principles have a different status as others are epistemically oppressive.

4. Politicizing epistemic systems

Having tried to disentangle knowledge imbalances, epistemic power, and epistemic oppression, I shall now discuss Dotson’s account of epistemic oppression in relation to epistemic systems. Note, however, that Dotson primarily focuses on epistemic resources when discussing the different modes of epistemic oppression, while I have focused on epistemic principles. While the notion of epistemic resources is more frequently used in feminist epistemology, epistemic principles are important concepts within the debate surrounding epistemic relativism. It should thus prove useful to differentiate both concepts. Epistemic principles are principles for acquiring belief and knowledge. Epistemic principles say how to properly form a belief, for example:

(Observation) For any observational proposition p, if it visually seems to S that p and circumstantial conditions D obtain, S is prima facie justified in believing p. (Boghossian Reference Boghossian2007, 64)

Epistemic resources are rarely defined. A fair, inclusive characterization of epistemic resources would be: “anything that helps align belief with evidence.” Many things have been characterized epistemic resources:

Knowing requires resources of the mind, such as language to formulate propositions, concepts to make sense of experience, procedures to approach the world, and standards to judge particular accounts of experience … we need epistemic resources for making sense of and evaluating our experiences. (Pohlhaus Reference Pohlhaus2011, 4)

There is, thus, a relationship between resources and principles. Epistemic resources create the space for potential epistemic actions. Epistemic principles, on the other hand, license what is allowed, obligatory, and potentially forbidden in this space of possibilities. Epistemic principles, then, are also more straightforwardly oppressive since a particular principle about how to form beliefs might disadvantage marginal knowledge practices. An epistemic resource, on the other hand, might not be oppressive in itself since a resource would be available and not prohibit the use of any other resources. Of course, epistemic oppression might come in with regard to the distribution of epistemic resources, the lack of plurality of them within an epistemic system, and their inadequacy in dealing with certain problems. But a resource does not exclude other resources, while a principle excludes other (e.g., contradictory) principles. With this differentiation at hand, I shall discuss Dotson’s account of epistemic oppression.

Dotson names three important characteristics of epistemic systems that I believe need to be recognized in the epistemic relativism literature: 1) knowers are situated; 2) epistemic resources are interdependent; 3) epistemological systems are resilient (Dotson Reference Dotson2014, 120).Footnote 11 These features continuously infringe upon the epistemic agency of epistemic agents by continuously reinforcing certain notions of what it means to be a knower, what are good sources for knowing, and what are good methods of inquiry and fact-finding.Footnote 12 In what follows, I shall discuss how these three features also bear important consequences for the concept of epistemic systems in the epistemic relativism literature.

First, the fact that one’s embodied social position has a bearing on what parts of the world are prominent to the knower (e.g., Pohlhaus Reference Pohlhaus2011; Haraway Reference Haraway1988) has yet to be incorporated into thinking about epistemic systems in mainstream epistemology. As argued in the previous section, epistemic agents are not homogeneous. There are knowers who, on the one hand, will reinforce what they consider the correct application of principles more strictly. On the other hand, reinforcing what a majority considers the correct application of a certain principle also accumulates epistemic power, that is, high epistemic status and epistemic high ground. The situatedness of a knower matters. Think of one famous example in the epistemic relativism literature: the confrontation between Galileo and Cardinal Bellarmine (e.g., Feyerabend Reference Feyerabend1975; Boghossian Reference Boghossian2007). Both are considered representatives of different epistemic systems because they have a fundamental disagreement about epistemic principles. Is the Bible an acceptable epistemic source about the structure of the universe? Is revelation an acceptable epistemic principle? But influential discussions of relativism focusing on this historical encounter seldomly consider how particular this encounter is (an exception is Kinzel and Kusch Reference Kinzel and Kusch2018).Footnote 13 Would it be the same encounter if Galileo had his dispute not with Bellarmine but with a clergyman from rural Italy? Surely, the clergyman would also be a representative of the epistemic system which regards revelation as an adequate epistemic principle. But the characteristics of their disagreement are local, and their encounter might have produced a disagreement with different specifications and emphases, respective to the situatedness of those partaking in the encounter.

Second, the requirement that all knowers within an epistemic system rely on collective and interdependent epistemic resources, that is, strategies to transform experience into knowledge (Pohlhaus Reference Pohlhaus2011, 4), is also seldomly made explicit in the epistemic relativism literature. This point furthers the critique on idealization. On the structural level, epistemic systems are not only made up of principles.Footnote 14 Knowers share other collective tools that help them align belief with evidence. Such tools need not all be propositional but could include other knowledge-conductive practices.Footnote 15 Furthermore, the interdependence of epistemic resources also highlights other components of epistemic systems that are not captured by focusing on epistemic principles alone: interdependence requires relationships. Epistemic relationships, in turn, highlight components such as trust or empathy required to relate to knowledge claims.

Lastly, I shall consider the claim that epistemic systems “refer to all the conditions for the possibility of knowledge production and possession” (Dotson Reference Dotson2014, 121) and are, as such, highly resilient. They can absorb extraordinarily large disturbances without redefining their structure. This point is also highly illuminating for the epistemic relativism literature. Many critics of epistemic relativism argue that it is unclear how to individuate an epistemic system. What are cases of genuinely distinct epistemic systems? The idea about the resilience of epistemic systems demonstrates how it is possible to admit variation within an epistemic system—epistemic agents will apply and follow certain principles heterogeneously—while still insisting that epistemic agents with varying intuitions about the correct application of principles still live in the same epistemic system. There are always disturbances through new applications of a principle that do not seem similar enough to past applications. But this does not mean that the system will crumble. Every institution is constantly constituted and reconstituted:

The system is held to persist as a pattern that resists disturbance and endures over long periods of time compared with the duration of specific social encounters or interactions. Indeed, to recognize the pattern one has to look at “society” over a comparatively long period of time, for the pattern is in the social processes themselves, as it were, constituted out of cycles of movement and change. (Barnes Reference Barnes1995, 36)Footnote 16

After discussing Dotson’s three features of epistemic systems and their bearing on the epistemic relativism literature, I will make a final point, namely that the most important contribution is the concept of epistemic oppression and how epistemic systems are oppressive. Epistemic systems oppress because they compromise one’s epistemic agency in different ways. They compromise it through inefficiencies or incompetencies when applying epistemic principles, a process Dotson coins first-order epistemic oppression (Dotson Reference Dotson2014, 123ff.).Footnote 17 For instance, while a certain epistemic principle might hold that “If X testifies p, S is prima facie justified in believing p,” it might not be applied equally to testimonies of all epistemic agents. Intuitions of epistemic agents, when it comes to certain testifiers, might lead to variations in applying this principle. Testimonial injustice, infringements of credibility, is such a form of oppression (Fricker Reference Fricker2007).

Epistemic systems can also oppress through insufficiencies within the language game regarding the experiences of epistemic agents within the system (Dotson Reference Dotson2014, 126ff.): dominant, majority language games might not contain certain concepts to account for experiences of certain minorities within the epistemic system. Dotson coins such cases second-order epistemic oppression. For instance, if the concept of “standpoint” is not part of the language game of the majority of epistemic agents, intuitions about epistemic principles that incorporate attaining standpoint as a good epistemic source will be considered deviant or, worse, incomprehensible. Hermeneutical injustice could result from such forms of oppression (Fricker Reference Fricker2007). Finally, epistemic systems can be oppressive because intuitions about epistemic principles in all their variance are not adequate tools to question the validity of these very principles. Dotson calls this form of oppression third-order epistemic oppression. While this means that certain types of knowledge cannot be produced within an epistemic system, the oppressive part lies in how processes within epistemic systems obscure that this is the case: resistance against certain epistemic principles, calling their adequacy into question, can be met with high amounts of resilience so that no substantial renegotiation of epistemic principles can be achieved. Through this resilience, the limits of these principles as well as their system-boundness will not be exposed (Dotson Reference Dotson2014).

That epistemic systems oppress certain knowers is an aspect that has so far not been addressed in the epistemic relativism debate. Dotson argues that some forms of epistemic oppression, particularly the ones caused by inadequate epistemic resources, are directly caused by the epistemic system. Questioning such fundamental aspects of an epistemic system throws our overall epistemic lifeways into question. Also, it makes it clear that we are inadequately equipped to address this situation since all our tools to address the situation are system-bound and ultimately coextensive with those tools we realized to be inadequate in the first place. Such criticisms are thus rejected as nonsensical, dangerous, or ridiculous (Dotson Reference Dotson2014, 130)—the epistemic system accomodates criticism through its resilience—its capacity to absorb large quantities of disturbance. In that spirit, Dotson claims that some forms of oppression are, thus, irreducibly epistemic (and not social or political) because they are directly caused by features of epistemic systems (such as resilience). It follows that epistemic principles that characterize an epistemic system are not “neutral” but always privilege certain knowers and certain forms of knowledge compared to others. Thus, not only are epistemic systems essentially social and political because they only exist in and through epistemic agents, but also, on the abstract, idealized level, the mere existence of epistemic principles might create social and political stratification within the epistemic system. I thus hope to have shown that Dotson’s account of epistemic oppression can be highly illuminating for the epistemic relativism debate. In the next section, I shall analyze Dotson’s claim about the irreducibly epistemic character of certain forms of epistemic oppression and contrast it with my account of epistemic systems being essentially social and political.

5. On the irreducibility of the epistemic

Irreducible forms of epistemic oppression are directly caused by the features of epistemic systems. Resilience and inertia characterize this form of oppression as irreducibly epistemic. To a degree, what “irreducibly epistemic” means is open to interpretation. Does “reducibility” suggest a form of theory reduction (that epistemology is or is not reducible to social or political theory?)? Does the relation admit for multiple realizations? These rather metaphysical questions have so far not been addressed. It might also be that the aim of declaring forms of oppression irreducibly epistemic is partly caused by mainstream, individualist epistemologies, disqualifying those schools of thought that consider the social and political as “impure” (Dotson Reference Dotson2018). But one does not have to give in as much. For sure, it is important to emphasize that there are genuinely epistemic aspects of oppression. I do not think, however, that it is possible to harm someone as a knower without harming their social relations and their political power as well. Thus, it is not a question of the “irreducibility” of either social or epistemic components, but rather about affirming these harms as socio-epistemically co-produced.

In what follows, I shall not presuppose this argument but address the necessarily social and political character of epistemic oppression in two ways. First, I will draw from the theory of social controls, first brought forward by Mary Douglas (Reference Douglas1970), to argue that every knowledge system is a social system and that knowledge ascription is in itself a social status. Second, I shall draw on finitism, a position associated with Wittgenstein’s position on rule-following and SSK, to argue that every application of a principle is a negotiation, and thus the features of an epistemic system that are oppressive are as well. My aim is to bring home the following point: according to Dotson, some forms of epistemic oppression are irreducibly epistemic because they follow from features of the epistemic system (Reference Dotson2014, 116). But—as I will show—epistemic systems are as social as they are epistemic and thus rather than “epistemic irreducibility,” socio-epistemic co-production is a more adequate perspective.

5.1 A grid/group account of epistemic systems

My first argument is rather structural or organizational, focusing on the social structure of an epistemic system. Anthropologist Mary Douglas has become famous for her analysis that social organization is always subjected to internal control by the group and a wide variety of anonymous controls and constraining external rules. Thus Douglas developed a classification of social gatherings based on two measures. (1) The “grid” aspect measures how hierarchical a certain system is by asking questions such as how autonomous individuals are, what degree of insulation is present, or how reciprocal interactions are. (2) The “group” aspect measures the frequency and kinds of interactions between group members, how well each individual is embedded in the group, and how strong the boundary is between the group and outside (Douglas Reference Douglas1970).

For instance, within an epistemic system, epistemic agents are all bound by certain epistemic principles, and deviance in following these principles will be punished (e.g., through loss of epistemic status). But there are also many group interactions, given the collective nature of agreeing upon a principle. Mary Douglas calls such gatherings high grid/high group structures. In this configuration, “loyalty is rewarded and hierarchy is respected, an individual knows her place in a world that is securely bounded and stratified” (Douglas 1982/Reference Douglas2013, 4). High grid/high group structures are bureaucratic, hierarchic, and collectivist. Individuals behave in sanctioned ways and use the framework of the respective configuration they inhabit to judge others and justify their actions. A critical point about grid/group analysis is that the presence of only one of these categorized groups is impossible. No mode of justification and judgment is viable independently, as other modes are needed to perform demarcation. Also, membership is not eternally fixed, and movement up and down the axes is possible.

A second configuration that needs to be considered is where there is much hierarchical control but fewer ties with other individuals. Inhabitants of high grid/low group structures miss out on “the protection and privileges of group membership” (Douglas 1982/Reference Douglas2013, 4). Such configurations are isolated, subordinated, and fatalist. Individuals are strongly regulated in terms of their socially assigned classifications. They are often not there by choice but instead forced into this quadrant by pressures emanating from other quadrants (Bloor and Bloor Reference Bloor and Bloor1982, 95).

If epistemic agents are not homogeneous within an epistemic system, some will have more access to shaping the principles of what counts as knowledge and who is a knower than others. These others would, however, not be free to think whatever. Instead, they would be bound by the same norms but have less power in shaping them, less standing in deciding which types of flexibility towards principles are sanctioned, and less say in co-negotiating slight changes. For instance, their epistemic lifeways are determined by applications of principles such as rendering the testimony of a black woman less credible than the testimony of a white man, even though this norm works to their detriment.Footnote 18

One important aspect of the high grid/high group structure, is how they can deal with dissenters. Bureaucratical hierarchies can deal well with dissent. The structures are compelling enough. It is possible to compartmentalize. Compartmentalization also contributes to the resilience of epistemic systems. That is, epistemic systems can accommodate ways that do not match shared intuitions about norms by giving them a confined space. Such practices include “monster-adjustment”—rephrasing the anomaly so it becomes less abnormal—or “exception-barring”—declaring the anomaly a rare and special case that need not be consideredFootnote 19 (Lakatos Reference Lakatos1976; Bloor Reference Bloor1978).

Besides such compartmentalization processes controlled by those in (epistemic) power, forming enclaves to resist the epistemic pressure of the mainstream is also possible. Douglas calls this the low grid/high group configuration. In low grid/high group structures, only the external group boundary is clear. All other statuses are “ambiguous and open to negotiation” (Douglas 1982/Reference Douglas2013, 4). This quadrant is often described as sectarian or as an egalitarian enclave. “Organizations in this quadrant regard themselves as unique, as mavericks that are categorically different from other organizations with which they might be compared” (Caulkins Reference Caulkins2009, 65). Outsiders might perceive the system as deviant, while members feel it “is a matter of pride and indictment of the dominant organizations” (Reference Caulkins2009, 66). Inhabitants of such groups are mutually dependent (Bloor and Bloor Reference Bloor and Bloor1982, 93).

Thus, it is possible for those who do not abide by and/or question epistemic principles to organize in a particular way that alleviates the pressure of the overall epistemic system. While such epistemic agents are still bound by the epistemic principles of the epistemic system in large parts of their lives, they have founded structures that give them flexibility and creativity with these norms. These structures can also be considered enclaves within an overall high grid/high group framework. Acquiring a particular standpoint could be one such example. Social movements have historically also had the role of such enclaves.

The low grid/high group configuration also helps to illustrate how change might be implemented within an epistemic system, for instance, to make the system more just, the knowing field less “unlevel” (Bailey Reference Bailey2014). If an enclave becomes strong enough, it might effect the modification of an epistemic principle, a conceptual clarification, etc. But while creating more just epistemic systems is possible, I do not believe it is possible to attain epistemic systems with no hierarchies. After all, it is one core characteristic of epistemic systems that epistemic agents living within it are bound by their intuitions about certain epistemic principles. If there were no grid control, there would be no shared epistemic principles, and it might thus follow that “everyone lives in their own epistemic system.” Douglas reserves for such configurations the low grid/low group quadrant, which is individualist, competitive, and entrepreneurial. Individuals are only responsible for themselves, and there is much “individual mobility up and down whatever current scale of prestige and influence” (Douglas 1982/Reference Douglas2013, 4).

The main point is this: even if it is possible to make an epistemic system more just (which I think is the case), these changes would have to be compulsory for all epistemic agents, so that those not following the implemented change would risk losing in epistemic status. But it is important to emphasize that, within a particular quadrant, there is also variability. While, for example, a high grid/high group system is one where both the ordinate values for “grid” and “group” are higher than zero, individuals, on the one hand, might clash with certain principles and obey them less (as long as the grid values do not reach zero). On the other hand, by implementing certain corrective changes, the grid control value for the whole system might decrease, making the organization less hierarchical.Footnote 20

In conclusion, if we extend our organizational perspective to epistemic systems, it becomes clear that social organization and the organization of knowledge are necessarily linked. Oppressive properties of epistemic systems, like resilience, correspond with social processes within certain hierarchical systems. Monster-adjustment or exception-barring, for instance, are ways of dealing with anomalies that endanger social and natural order, which constitute the resilience of an epistemic system. This idea is based on the notion that social and epistemic order are co-produced. Sheila Jasanoff argues: “We gain explanatory power by thinking of natural and social orders as being produced together” and:

The ways how we know and represent the world (both nature and society) are inseparable from the ways in which we choose to live in it. Knowledge and its material embodiments are at once products of social work and constitutive of forms of social life; society cannot function without knowledge, no more than knowledge can exist without appropriate social supports. (Reference Jasanoff2004, 2)Footnote 21

That the features of epistemic systems are oppressive in themselves is thus not an argument in favor of this form of oppression being irreducibly epistemic. Rather, they are socio-epistemically co-produced since these very features are not separable from the social sphere.

5.2 A finitist interpretation of epistemic principle-following

I shall now provide a second argument against the “irreducibility” of certain forms of epistemic oppression. My first argument was “structural.” This second argument will be more agential in that I will base my argument on behaviors of epistemic agents within an epistemic system. I will consider how applying epistemic principles in an epistemic system disfavors “epistemic irreducibility” as a perspective on different types of oppression.

Different social theories analyze principle-following differently. Two opposed positions are determinism and finitism, respectively. Finitism denies that what counts as a successful application of a principle is predetermined. Meaning does not determine use, but use determines meaning (see Figure 2). The central point of finitism is that an epistemic agent’s competence in following a principle is based on a finite number of previous examples where the principle has been applied. Every new instance of determining whether a principle has been applied successfully is based on its similarity against the backdrop of prior instantiations of successful applications. But (1) the decision whether x is similar to y is something a collective has to agree upon; and (2) such judgments are highly contingent and only local and temporary. “To know a principle is to know a finite number of socially sanctioned exemplary previous applications” (Kusch Reference Kusch2010). A principle is a social institution—a self-referring system of talk, beliefs, and actions (Barnes Reference Barnes1995; Bloor Reference Bloor1997).

Figure 2. Differentiation of finitism and determinism.

Individualist determinism (Quadrant B) holds that it is possible to make sense of rule-following on the level of a (socially isolated) individual and “her dispositions to act in appropriate ways” (Kusch Reference Kusch2020, 45). Communitarian determinism (Quadrant A) exchanges the individual with a social group, but maintains that rule-following has to do with the communities’ mental dispositions to act (Kusch Reference Kusch2020, 45). Individualist finitism holds that to make sense of rule-following we need to understand how individuals learn rules by being taught a finite number of examples (Quadrant D). Communitarian finitism, finally, holds that the relevant community will decide the similarities between examples and new applications (Quadrant C).

In our case, an array of exemplars of successful applications of an epistemic principle are social institutions. Being an exemplar is a social status. A principle and interpretations of its meaning have no existence outside the practices it is involved in (Kusch Reference Kusch2004, 70–71). No epistemic agents can ever “know” the “collective consensus” on all epistemic principles. From this, it also follows that every epistemic agent can only “represent” her epistemic system incompletely since there will be variations in how a current application of a principle will be negotiated as similar or dissimilar to prior applications. Also, there will be variations regarding how different precedents will be weighted.

Thus, adopting an epistemic agent-based perspective on epistemic systems characterizes them primarily as a sum of principle-following behaviors based on intuitions of epistemic agents regarding correct applications of such principles. Any distilling of these instances into a definite set of epistemic principles characterizing the epistemic system would be an idealization that is not able to capture epistemic activities in practice. While this argument is, on the one hand, a more detailed account of my argument that epistemic systems are heterogeneous and essentially social, put forward in the second section, the finitist perspective also helps address the idea of certain forms of epistemic oppression being irreducibly epistemic.

Dotson argues that those forms of oppression caused by features of the epistemic system (i.e., third order oppression), such as its resilience, are irreducibly epistemic. Given the finitist perspective, what makes epistemic systems resilient—that they can absorb large quantities of disturbance without needing to change their structure—is caused by the epistemic activities of epistemic agents, for instance, their intuitions about certain instances of applications of epistemic principles. It is not the system that is resilient but the epistemic agents.Footnote 22 Locating the resilience with epistemic agents and not the epistemic system is preferable since it highlights the actions that create the resilience.

As a consequence, an instance of “irreducibly” epistemic oppression, where the oppression is produced by the features of the epistemic system, would be one where the status of an assertion would not be “justified,” “true,” or “knowledge” because it would not conform to a particular epistemic principle. This judgment would be made by referencing intuitions about its similarity with a bundle of precedents of successful principle application. If the assertion receives the status “unjustified,” the assertion will be ridiculed, rejected as nonsensical or deceptive (Dotson Reference Dotson2014, 130)—it is met by the resilience of epistemic agents not to let the assertion question their epistemic lifeways. These judgments are, however, collective and not individualist. For an assertion to have any “status” at all, this status must be conferred by a collective of epistemic agents. Thus, the oppressive judgment that an assertion does not receive a certain status because it is too dissimilar from intuitions about previous instances is a social and collective one (as well as local and contingent). Therefore, if we accept that epistemic systems and epistemic principles are institutions, the oppression they cause is better described as socio-epistemically co-produced rather than “irreducibily epistemic.”

Before concluding this section, let me, however, consider one objection. Let me consider what Dotson might mean by third-order oppression being “irreducibly epistemic.” While reduction is a broad topic, one option would be that oppression being irreducibly epistemic simply means that it is possible to express relationship A in terms of relationship B that do not rely on the proprietary vocabulary of relationship A. Maybe Dotson has something akin to theory reduction in the philosophy of science in mind (Sarkar Reference Sarkar1992).Footnote 23 I think that this interpretation can be rejected for two reasons. First, it would not serve as a good distinction between first-, second-, and third-order oppression. It might also be possible to describe first- or second-order oppression in the proprietary language of epistemology only. But the fact that it is possible in principle to describe a phenomenon in the terms of a highly specialized discipline does not imply much about the nature of the phenomenon.

My second objection concerns the fact that, while probably doable, giving an account of third-order epistemic oppression by relying on strictly epistemological vocabulary would be an idealization. Let me give an example to illustrate my worry. Imagine that my landlady, a grand master in chess, says that, to keep my flat, I have to win a game of chess against them. So we play, and I lose. I could describe what happens (and why I have to look for another flat) merely in terms of the game we are playing—by providing a protocol of all moves made on the chessboard. But would that be a good account of the situation? No, it is a highly idealized way of representing what happened. Similarly, it is possible to account for all epistemic interactions by protocolling individual moves within the language game, that is, the assertions of epistemic agents involved. I would have thus expressed a situation of epistemic oppression in terms of epistemology only—by protocolling the judgments actors pass regarding a certain application of an epistemic principle. But I am not sure that a good account of the situation would have been provided. In conclusion, accounting for epistemic oppression in exclusively epistemic terms is a playful engagement with what one’s disciplinary language can, in principle, do, at best, and an idealization that masks vital aspects of the interactions, at worst.

6. In search of common ground … continued

This article aimed to bring two bodies of scholarship into contact through the notion of the epistemic system. I hope to have shown that it is worthwhile to examine how epistemic relativism scholarship and scholarship on epistemic oppression can contribute to each other. I hope to have particularly shown, that (1) epistemic systems in the epistemic relativism literature necessarily need to be looked at as oppressive, and the consequences of the oppressiveness of epistemic systems need to be considered when examining epistemic systems; and that (2) the oppressive character of epistemic systems is socio-epistemically co-produced. While it is important to highlight and further characterize the epistemic aspects of epistemic oppression, I hope to have shown that they are not dissociable from social and political aspects.

While these two lines of scholarship have seldomly been engaged together, I hope to have forged a new perspective on how (SSK-inspired) epistemic relativism and feminist epistemology might inspire and draw from each other. Of course, much has yet to be explored, for instance, how other concepts prominent within feminist epistemology might enrich the epistemic relativism literature (e.g., Veigl Reference Veigl2023). I believe there is much to gain if these two types of epistemologies, often dismissed by mainstream, subject-centered epistemology as “impure” forms, would (at least strategically) join forces on certain socially and politically highly relevant issues. It is not the case that only those epistemologies that readily acknowledge the importance of the social and the political are the ones where the social or political are inextricable from the epistemic. No epistemology can rid itself of the social. Any account of what it means to know that relies somehow on shared principles is intrinsically epistemic and social—as it is impossible to separate the epistemic from the social, it is also impossible to claim to have any knowledge in the absence of social structure.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Martin Kusch and Sonja Riegler for their advise on a draft version of this manuscript. The author also thanks all participants at the “Wie weiter mit der politischen Epistemologie?” workshop at the University of Freiburg for their input.

Sophie Juliane Veigl is a philosopher of science with a special interest in knowledge systems, expertise, and epistemic relativism. Her approaches are inspired by feminist epistemology as well as the sociology of scientific knowledge. Prior to undertaking a PhD in philosophy, she studied biology, comparative literature, and history and philosophy of science at the University of Vienna. Before her current post-doctoral appointment at the university of Vienna, she undertook research stays in Tel Aviv, Munich, Exeter, and Cambridge. Sophie is a board member of AIDS Help Vienna and wrestles in her free time as the philosopher Diotima.