At first glance, Canada presents a puzzle in the context of racial inequality. The country is often seen as having a robust social model and as being an international leader in the development of multiculturalism policies and cultural tolerance. Yet these policies, which together should work to enhance equality and social solidarity, coexist with significant levels of racial economic inequality, smaller perhaps than in the United States but significant nevertheless.

In our view, the fact of racial economic inequality itself is not puzzling; there is a long history of a specifically Canadian racial order with tangible effects on the uneven distribution of wealth over time (Thobani, Reference Thobani2007). However, the continued persistence of racial economic inequality well into the twenty-first century raises important questions about the efficacy and equity of the complex policy architecture that defines the socio-economic landscape. This includes a welfare state including universal health care, a race-neutral system of immigrant selection, an official multiculturalism policy and a Charter of Rights and Freedoms with powerful anti-discrimination provisions. Combined, these initiatives built a social safety net and a model of diversity governance that many assume are more robust, redistributive and inclusive than those that exist south of the 49th parallel. Yet racial economic disparities stubbornly persist, in some cases across multiple generations. Despite this fact, racial economic inequality has not emerged as a central driver in the recent restructuring of core social programs. Understanding why seems especially important as racial minorities have borne a disproportionate burden during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement has challenged existing understandings of power and privilege.

The purpose of this article is to examine the failure of Canadian public policy to address racial economic inequality directly. Why do policies not focus on alleviating racial economic inequality? And why has racial inequality not emerged more forcefully as a central feature of policy deliberations?

In our view, answering these questions requires an understanding of Canadian political development since the middle of the twentieth century. This history can be usefully divided into two key periods: the postwar era from the 1940s to the early 1980s; and the decades from the 1980s to the first decades of the twenty-first century. The first part of our argument posits that the frameworks, problem definitions and policy tools developed in the postwar era were never intended to address racial economic inequality. The social programs, immigration regulations, multiculturalism policies and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms were all institutionalized during an era in which the Canadian population was overwhelmingly of European descent. In the period 1960 to 1980, over 96 per cent of Canadians traced their ancestry to Europe. People identifying as Aboriginal represented less than 2 per cent of the population and faced barriers to political mobilization; and, in combination, Asians, Blacks and other racial minorities also represented less than 2 per cent (Li, Reference Li2000). As a result, the policy regime put in place in the postwar era was shaped by the beliefs and concerns of a white European–descended population.

During the last decades of the twentieth and early decades of the twenty-first centuries, shifting immigration patterns rapidly transformed Canada into one of the most racially and ethnically diverse countries in the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). By the time of the 2016 census, racial minorities represented approximately 23 per cent of the population, and major cities such as Toronto and Vancouver had become minorities-majority cities. In addition, during the same decades, virtually all the core government programs inherited from the postwar generation were restructured in response to changing economic and social pressures. Nevertheless, although racial economic inequality was becoming more evident and increasingly inappropriate given the normative egalitarian discourse of the period, the retooling of the policy architecture still paid little attention to racial economic inequality. Why?

The second part of our argument contends that universalist norms were deeply embedded in the frameworks, problem definitions and policy tools inherited from the postwar generation. The postwar era represented a watershed in attitudes toward race and human rights, shaped by the rejection of Nazism and scientific racism, the spread of decolonization and the energetic civil rights movements that emerged in many countries. Racial distinctions in law and policy were increasingly “challenged by the human rights universalism of the postwar period” (Triadafilopoulos, Reference Triadafilopoulos2012: 55; see also Kymlicka, Reference Kymlicka, Banting, Courchene and Seidle2007). These norms were carried forward into the more racially diverse Canada, where they have tended to steer attention away from the use of racial categories in policy design and evaluation. As we shall see, in spite of recognizable racial economic inequality, race did not register in the politics of welfare state retrenchment of the 1990s or the more recent expansion after 2015. Nor did racial economic inequality frame the dramatic revisions to immigration policy in recent decades or the quieter evolution of multiculturalism policy. Anti-discrimination policy is a partial exception to this argument, but the policy tools developed to address directly the economic dimensions of racial inequality, such as the Employment Equity Act, are relatively weak.

In theoretical terms, our research seeks to contribute to the literature on Canadian Political Development, which asks “large-scale, long-term, big-picture questions of Canadian political science” by examining the causes and consequences of durable shifts in governing authority, as well as the ways that the entrenchment of institutional arrangements and public policies at certain historical moments can foreclose otherwise viable alternatives for political action (Lucas and Vipond, Reference Lucas and Vipond2017: 234; see also Orren and Skowronek, Reference Orren and Skowronek2004). Our contributions are two-fold. First, we attempt to take up Miriam Smith's (Reference Smith2009) call for deeper and more complicated analyses of diversity as a question of political power related to the protection of rights, the allocation of resources and access to political participation. While the state's role in the production of racial inequality has been a consistent theme in the extensive literature on race and American Political Development (Lowndes et al., Reference Lowndes, Novkov and Warren2008; King and Smith, Reference King and Smith2011; Johnson, Reference Johnson, Valelly, Mettler and Lieberman2016), the deep and constitutive connections between the development of institutional arrangements and public policies and the allocation of power and privilege are less explored in Canada.

Second, our analysis includes a sustained consideration of the intersecting roles of ideational frameworks, path dependency and policy drift. In our view, policy drift in this context largely occurred because of the pervasive influence of institutionalized norms and ideas. Entrenched understandings of core social programs define their basic purposes and the tools they make available with which to respond to changing conditions. These understandings, we argue, are fundamentally premised on the principles of universalism, which tend to render race and racism as either incidental or antithetical to the operation of Canadian liberalism. They are embedded in political institutions and policy regimes and thus contribute to the persistence of a policy architecture that is based on egalitarian principles and yet has failed to rectify circumstances of racial economic inequality.

The analysis here focuses on the experience of racial minorities that owe their presence in Canada to immigration.Footnote 1 Indigenous peoples face even greater economic problems, but the reconciliation agenda raises a distinct set of policy issues. Indigenous peoples define themselves as nations, not racial groups, and pursue a different agenda rooted in national identity, autonomy, self-governance and ownership of land. Their agenda has a greater similarity to that of the Québécois than of immigrant racial minorities.

We advance our argument in four sections. The first section provides an overview of our theoretical argument about policy drift, path dependency and the causal role of ideas in political analysis. The second section presents evidence on the persistence of racial economic inequality in Canada. The third and longest section examines major developments in four key policy areas: the welfare state, immigration policy, multiculturalism and anti-discrimination protections. The final section pulls the threads of our argument together.

1. Path Dependency, Policy Drift and the Role of Entrenched Ideas

Institutionalist interpretations provide some insight into the relative silence of the Canadian policy architecture on the economic disadvantage faced by racial minorities by analyzing both formal institutions and dominant ideas embedded in them. Students of Canadian politics have long paid heed to political institutions as powerful formations and understand that long-established government programs represent key institutions that define the terrain on which politics is played out (Smith, Reference Smith2009: 843; Lecours, Reference Lecours2005; Lucas and Vipond, Reference Lucas and Vipond2017). When first introduced, major programs reflect a particular conception of the problems to be addressed and provide a particular set of policy tools to address them. As historical institutionalists have argued, these early choices shape future choices, increasing the costs of shifting to a new policy path in later years. Such institutional dynamics contribute to path dependency and policy drift, helping to explain the persistence of policy regimes even after the social conditions that initially gave rise to them have faded (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Pierre and King2005). In some cases, policy drift emerges because political agents actively choose not to respond to environmental changes or are purposefully obstructed by social coalitions that block change (Emmenegger, Reference Emmenegger2021). For example, in Winner-Take-All Politics, Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson (Reference Hacker and Pierson2010) argue that the extraordinary nature of wealth inequality in the United States is a direct result of policy drift, in that increased ideologically driven gridlock between the two major parties in Congress has favoured the status quo by preserving older institutional rules and regulations that enable and exacerbate wealth disparities. Institutional drift is especially widespread in American politics because of the separation of powers, which makes it far easier to prevent policy change than to enable it.

However, another form of policy drift, perhaps better called policy inertia, results from institutionalization of ideas and ideologies, which frame problems in ways that better reflect the past than the present.Footnote 2 According to scholars of discursive institutionalism, ideas often become embedded in institutions, and established policy paradigms become taken for granted as simply “common sense,” creating cognitive locks that guide particular courses of action (Béland and Cox, Reference Béland, Cox, Béland and Cox2011: 3–4; see also Hall, Reference Hall, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016: 35–36; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2008). Ideas are dynamic and may exist at the level of specific policy proposals and problem definitions or, in our case, as public philosophies that “serve as a kind of meta-problem definition for political actors, providing a way of seeing the public issues that are on their docket” (Mehta, Reference Mehta, Béland and Cox2011: 42). Because ideas that are embedded in institutions can legitimize and normalize power differentials among social groups, the study of these ideas is important for understanding the nature of power, domination and inequality. Research on the development of racial orders in the American context stresses the centrality of institutions as “carriers of ideas,” a formulation that “appreciates the interconnection between institutions, understood as governing arrangements and the structures and organizations connected to them, and the ideas that animate political actors, shape their goals, and thus give content to the patterns of behavior that institutions construct” (Lieberman, Reference Lieberman, Béland and Cox2011: 215). We suggest that policy inertia can result from dominant ideologies—in this instance, the universalistic principles of Canadian liberalism—that frame policy problems in ways that are not conducive to decisive policy action on racial economic inequality.

The distinctive features of liberalism include individualism, egalitarianism, universalism and meliorism (Gray, Reference Gray1995). Several of these dimensions are critical to understanding the dynamics of the specific policy domains explored below. Nevertheless, the common thread running through the analysis is the commitment to moral universalism at the heart of liberalism, which has generated an enduring tension with the realities of racial difference. Liberal ideologies profess to treat all individuals equally and resist taking ascriptive characteristics such as race or gender into account in the formulation of public policy. In practice, however, such norms can work to create, maintain and reinforce structural and institutional racial inequalities, often by refusing to acknowledge prescient disparities. Much like the way that feminist analyses of liberalism emphasize that the assumption of a public/private divide in liberal ideology and the institutional arrangements of the welfare state obscure a fundamental source of power and inequality in gender relations (O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Orloff and Shaver1999: 49–50), the tendency to view racism as an illiberal aberration hides the ways in which racial inequality can be exacerbated or simply ignored by seemingly universal public policies.

An analysis of the nature of Canadian liberalism and the ways that the influence of both toryism and socialism has caused it to diverge from liberal ideologies in the United States is a well-trodden path in the Canadian political science literature (Hartz, Reference Hartz1955; Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1966; Forbes, Reference Forbes1987). There are also distinctions to be made among varieties of liberalism. The dominance of the classical liberalism of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which gave priority to individual rights and limited state power, was challenged in the mid-twentieth century by a social or reformist liberalism, which shared classical liberalism's concern with individual freedom but also incorporated new ideas about social citizenship and an enlarged role of the state in enhancing egalitarian values through the welfare state and other policies (O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Orloff and Shaver1999: 450; Jeffrey, Reference Jeffrey, McGrane and Hibbert2019). However, classical liberalism did not disappear entirely. It flourished again later in the century in the form of neoliberalism, which as both an ideology and set of policies, led to the transformation of government in the 1980s and 1990s. This process unfolded through an extension of and commitment to market principles combined with state downsizing, the privatization of public assets, the deregulation or elimination of state services, trade liberalization and an emphasis on technocratic, “efficient” market-based solutions to policy problems (McBride, Reference McBride1992). In recent years, the reformist side of Canadian liberalism grew ascendant again, as governments responded to concerns about the sharp rise in precarious employment and income inequality. As Rianne Mahon (Reference Mahon2008) argues, the contemporary Canadian welfare state is shaped by a shifting balance between neoliberalism and “inclusive” or “social liberalism.”

The underlying universalism of the welfare state, immigration policy, multiculturalism policy and anti-discrimination protections in Canada runs counter to the denominational nature of racial identification. This tendency is reinforced by the traditional role that social policies have played as nation-building projects in the face of persistent territorial and linguistic divisions, which at times have threatened the political integrity of the country. Universal social policies have played an integrative role, helping to reinforce a sense of national belonging; over time, many Canadians, especially in English Canada, came to see national social programs as part of the Canadian identity, part of the social glue holding their vast country together (Banting, Reference Banting, Liebfried and Pierson1995). Canadian national identity accommodates and celebrates diversity in many ways; however, it has also tended to deflect attention from race as such. As we shall see, social problems that might elsewhere be interpreted through the prism of race tend to be seen as issues of immigration status or cultural or linguistic difference, and policy tools have been deployed accordingly. This is not to say that race is completely absent from political contestation and controversy. However, there is something curiously indirect about the Canadian approach, at least in government circles. Government publications and official statistics prefer the term visible minorities, which the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has criticized for rendering invisible the plight of distinct racialized groups (United Nations, 2017). More tellingly, Canadian governments at all levels have been slower to gather and publish data based on race than has the United States (Thompson, Reference Thompson2016), which recently has undoubtedly hampered the country's ability to detect and correct the racial disparities in infection and treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Race as a formal organizing principle still has only a modest presence in Canadian policy.Footnote 3

Our analysis confirms a central finding of race and ethnic politics scholarship on the conceptual distinction between explicit racism of the past and the more implicit but still pervasive systemic racism of the present (Soss and Weaver, Reference Soss and Weaver2017; Hanchard, Reference Hanchard2018). Institutional racism manifests as the rules, norms and/or patterns of behaviour that perpetuate relative disadvantage for some racial groups and advantage for others; the institutionalization of implicit racial bias; the ways that seemingly universal rules affect populations differently and result in the reification of pre-existing racial inequalities; the way that seemingly universal rules are, in fact, designed to advantage white populations and disadvantage non-white populations; or any combination of these tendencies. This form of racism does not require the deliberate and intentional actions of policy drift; in fact, it does not necessarily depend on agents at all. Institutional racism is, by nature, self-perpetuating, and so inaction—or inertia—simply works to reinforce the status quo.

Explaining why something did not happen is always challenging. However, we argue that, in combination, formal political institutions and long-established program structures that institutionalized conceptions of liberal universalism help to explain the failure to address racial economic inequality. Of course, this situation was compounded by other forces, including the increasingly decentralized nature of the Canadian federation, the political marginalization of cities, the growth of conservative populism and the decline of equality-seeking social movements, all of which weakened the ability of the federal government to formulate decisive action on racial inequality. Our analysis complicates this picture by demonstrating the important role of policy inertia, the potentially obscuring role of dominant narratives and the extent to which inaction is a consequential form of political action.

2. Racial Diversity and Racial Economic Inequality

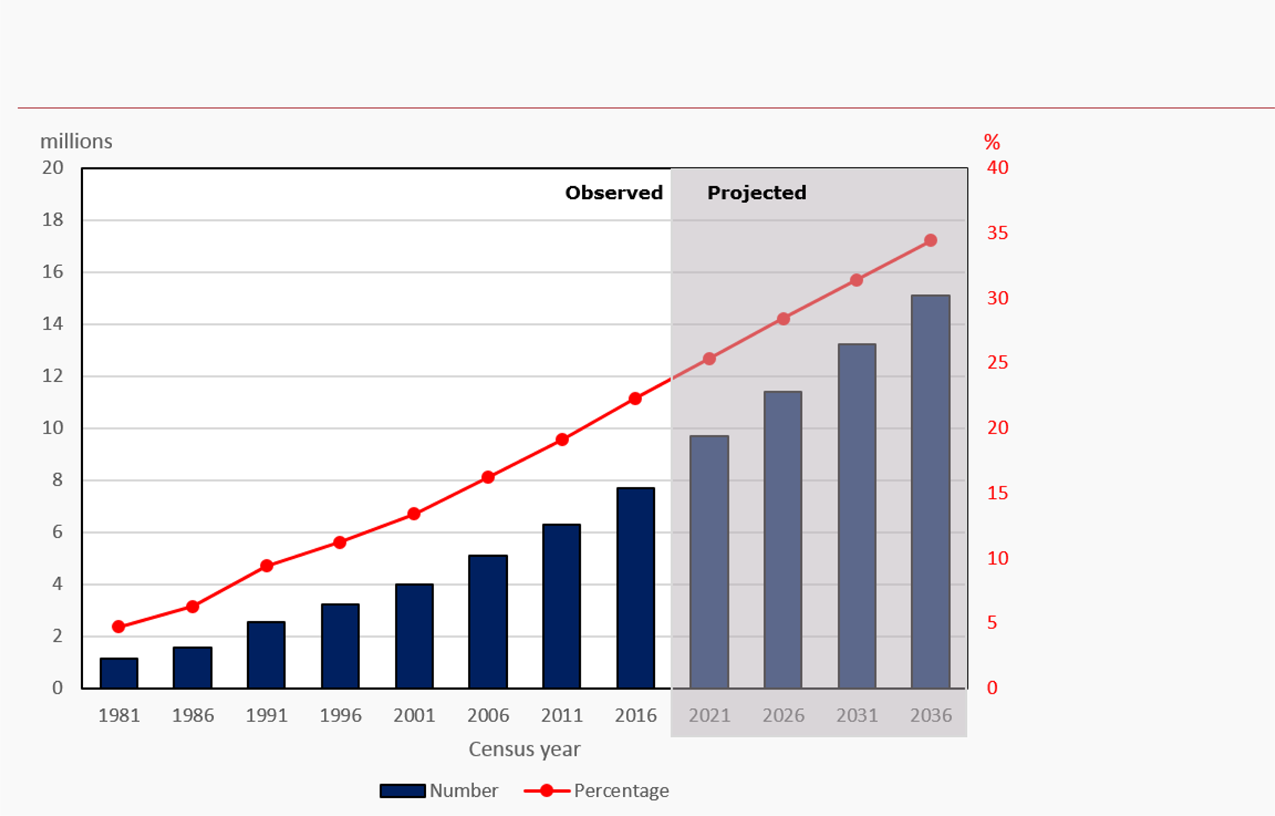

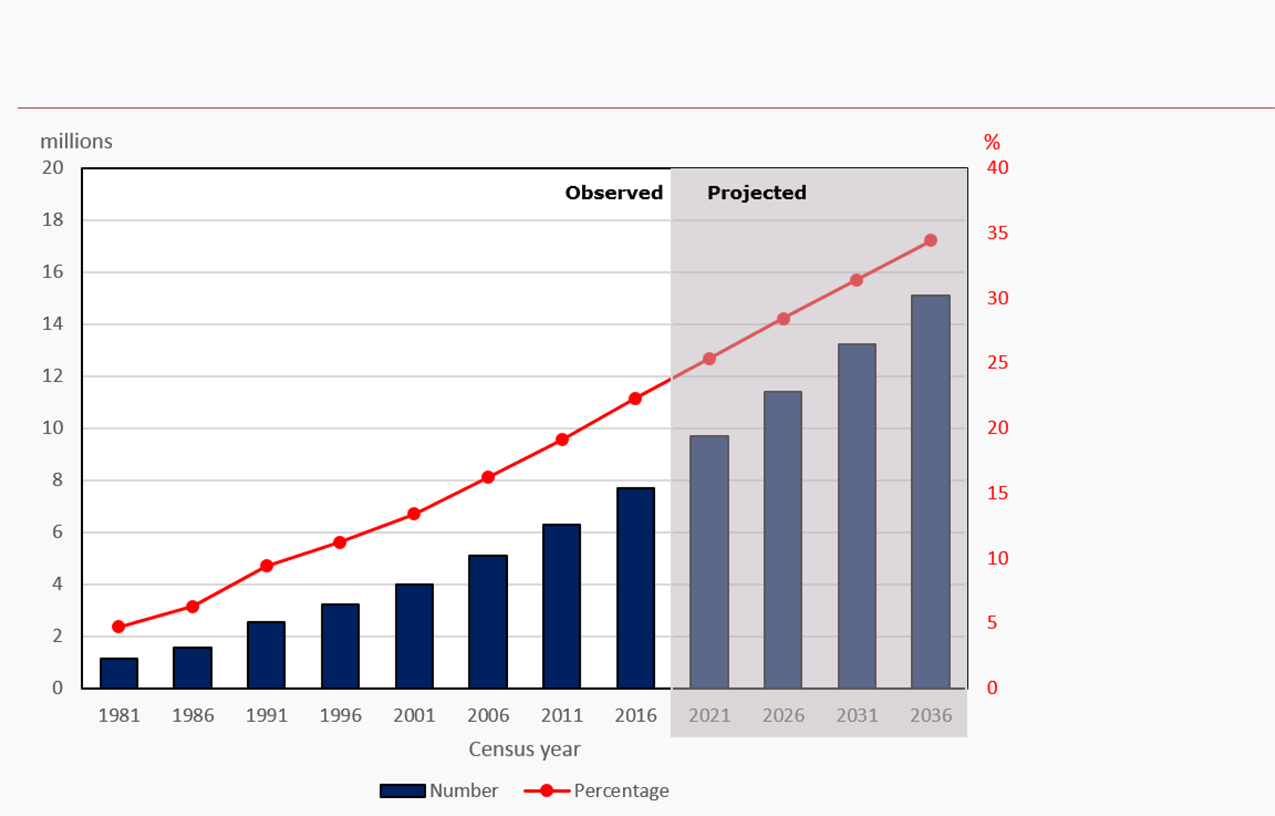

The speed of the change in the racial composition of the Canadian population is captured in Figure 1. As noted earlier, in the 1981 census, racial minorities and Aboriginal peoples represented only 4 per cent of the population; in the 2016 census, 22.3 per cent of the population self-identified as a visible minority, a number expected to grow to a third of the population within two decades. Toronto is a minorities-majority city, at 51.4 per cent, and Vancouver is close (48.9 per cent). By any standard, this is a rapid change in racial demography.

Figure 1. Number and Proportion of Visible Minority Population in Canada, 1981 to 2036

Sources: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 1981 to 2006, 2016; National Household Survey, 2011; Immigration and Diversity: Population Projections for Canada and its Regions, 2011 to 2036.

Canadians have long considered their country a mosaic of ethnic hues. However, as John Porter (Reference Porter1965) pointed out a half century ago, this was a vertical mosaic, with British-origin Canadians at the apex of an ethno-racial hierarchy. Much has changed in the intervening years. The income differences between English- and French-speaking Canada have almost disappeared, and a number of other white ethnic groups now earn more on average than British-origin workers. However, as Canada became much more racially diverse in the last quarter of the twentieth century, Canadian inequality diversified as well.

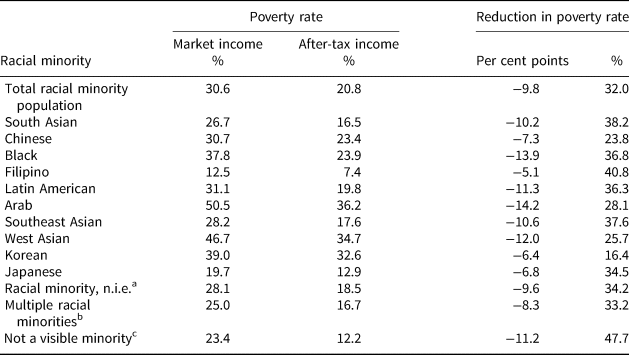

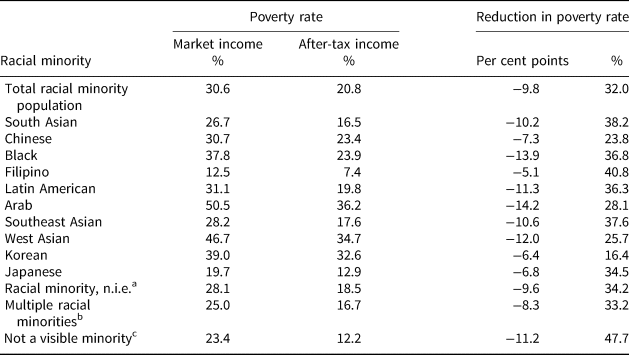

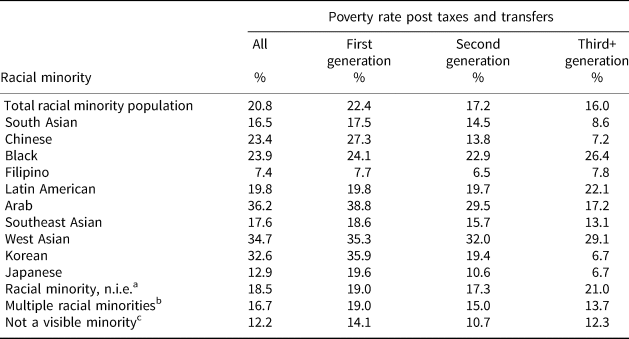

Table 1 provides one view. It compares poverty levels among racial minority groups with the poverty rate in the rest of the population in 2015. The table measures the incidence of poverty in terms of both market income, primarily wages and salaries, and after-tax income, which includes the impact of both government income transfers and direct taxes. Three patterns stand out. First, over 30 per cent of the racial minority population would live in poverty based on their market income alone, and for some minority groups the number approaches 50 per cent. Second, while the tax-transfer system is redistributive and does reduce the incidence of poverty, the poverty rate in after-tax income among racial minorities generally remains almost 21 per cent; and the reduction in poverty as a result of the tax-transfer system is considerably greater for the rest of the population (47.7 per cent) than for the racial minority population as a whole (32 per cent). Third, there are immense differences across racial minorities. Some minorities do comparatively well, but poverty rates among Blacks, Arabs, Koreans and West Asians are much higher.

Table 1 Poverty among Racial Minorities, 2015

Source: Data for low income after tax from Statistics Canada, 2016 Census. Cansim Series 98-400-X2016211. Income data refer to 2015. Data for low income on a market income basis kindly provided by Statistics Canada.

Notes:

a n.i.e: not included elsewhere.

b Persons who identified with more than one minority group in census.

c Includes persons identifying as Aboriginal.

Many Canadians like to reassure themselves that although immigrants often face a difficult journey to integrate economically, their children—the second generation—have much greater success. Table 2 tracks poverty levels (after taxes and transfers) across generations of racial minorities. Poverty rates are lower among the second generation, markedly so among some groups, such as Chinese- and Japanese-Canadians. Nevertheless, it is the persistence of high poverty levels into the second and even the third-plus generations that stands out, again especially among Blacks, Arabs and West Asians. Poverty among Blacks hardly changes in the second generation and actually nudges upward in the third-plus generations.

Table 2 Poverty among Racial Minorities, by Generation, 2015

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census. Cansim Series 98-400-X2016211. Income data refer to 2015.

Notes: See Table 1.

These broad patterns are consistent with studies of racial economic inequality that focus on earnings in the labour force. An analysis by Statistics Canada found that, controlling for personal characteristics such as age and education (but not the characteristics of the job), there were large negative gaps—especially for male workers—among some minorities, including Blacks, Chinese, South Asian and other racial minorities (Picot and Hou, Reference Picot and Hou2011; Pendakur and Pendakur, Reference Pendakur and Pendakur2011). Members of racial minorities are also more likely to be unemployed or underemployed in precarious positions with job insecurity, low wages and few employment-based benefits (Galabuzi, Reference Galabuzi2006; Block et al., Reference Block, Galabuzi and Tranjan2019; Ng and Gagnon, Reference Ng and Gagnon2020). Recent studies of the Black population from Statistics Canada also highlight the persistence of racial economic inequality; for example, unemployment rates among the Black population were consistently higher than in the rest of the population between 2001 and 2016, including at higher levels of education (Houle, Reference Houle2020; Statistics Canada, 2020). A 2008 study comparing the economic status of Black and white populations in Canada and the United States found that once the relative sizes of different generations of immigrant groups were controlled, racial income and wage gaps in the two countries are strikingly similar (Attewell et al., Reference Attewell, Kasinitz and Dunn2010).

Clearly, racial economic inequality is a significant phenomenon. Yet it does not resonate strongly in policy debates and was not a policy driver in the restructuring of the core policy structures in the 1990s and early 2000s. Why?

3. The Policy Structures

This section demonstrates the marginality of the politics of race and racial economic inequality in the establishment and later restructuring of key policy domains, focusing in turn on the welfare state, immigration, multiculturalism, and anti-discrimination programs.

The welfare state and racial inequality

The postwar welfare state clearly made Canada a fairer, less unequal place, and some Canadians liken their system to the social-democratic model found in Europe. In reality, the Canadian version of the welfare state has always been comparatively modest, reflecting the constrained nature of the commitment to egalitarianism in Canadian liberalism. Social spending as a percentage of GDP is comparatively low, and although the tax-transfer system does reduce inequality more than in the United States, it is not as powerfully redistributive as in much of Europe.Footnote 4

The universalism of Canadian liberalism ensured that racial minorities have been formally incorporated in the welfare state in a “colour-blind” way, with little of the explicit exclusion—or “welfare chauvinism”—practised in some countries (Koning, Reference Koning2019). In general, immigrants admitted as permanent residents are eligible for health care and income benefits on the same terms and conditions as the native born. Most formal restrictions that do exist are temporary; for example, immigrants admitted through the family reunification provisions are often required to rely on their sponsor rather than state assistance for an initial period in the country. The biggest formal access barriers concern pensions. Old Age Security is subject to complicated residency requirements. In addition, immigrants benefit less from the Canada Pension Plan, since its benefits depend on earnings, and many immigrants, especially those from poorer countries, do not have time to build strong contribution records. These barriers—both explicit and implicit—help explain why social programs reduce poverty among racial minorities less than among the rest of the population.Footnote 5

The social architecture inherited from the postwar generation has gone through several cycles of restructuring, including retrenchment in the 1990s and early 2000s, and a more recent cycle of social policy expansion since 2015. As elsewhere, the retrenchment cycle was driven primarily by the politics of globalization and neoliberalism (Mahon and McBride, Reference Mahon and McBride2008). Universal programs, which benefit the middle class, such as pensions and healthcare, were sustained with major injections of new resources. However, programs for unemployed working-age people, such as Employment Insurance and social assistance, were cut significantly (Battle, Reference Battle, Banting, Sharpe and St-Hilaire2001; Kneebone and White, Reference Kneebone and White2008). Tax levels and the progressivity of the tax system were also reduced (Boadway and Cuff, Reference Boadway, Cuff, Banting and Myles2013). A study by the OECD concluded that during the period 1995–2005, redistribution had weakened more in Canada than in any other member country (OECD, 2011). Recently, a new cycle of policy change has reversed direction, in response to growing concern about precarious employment and the growth of inequality symbolized by the rise of the top 1 per cent of income earners. The federal Liberal government elected in 2015 strengthened child benefits, Employment Insurance and retirement pensions, while several provincial governments raised minimum wages significantly.

What role, if any, did the politics of race play in either policy cycle? Very little. In the first cycle, racial diversity did not fuel the politics of retrenchment, as in some other countries. In the United States and Europe, many commentators argue that racial diversity erodes a sense of community, weakens feelings of trust in fellow citizens and fragments the historic coalitions that built the welfare state. They argue that members of the majority public withdraw support from social programs that give money to “outsiders” (Alesina and Glaeser, 2004). So far, such corrosive politics have been muted in Canada, at least in relation to immigrant minorities (Soroka et al., Reference Soroka, Johnston, Banting, Kay and Johnston2006). In contrast to the United States, where the rhetoric of “Black welfare queens” was central to anti-welfare backlash, the politics of race did not play a prominent part in welfare retrenchment in Canada.

Instead, discourse during the retrenchment cycle proceeded in a universalist language of generic workers and their families. The dominant paradigm, known as the social investment model, assumed that in the new global economy, governments should not try to protect their citizens through income transfer programs. In the future, individuals’ economic security would depend on their own human capital, and the primary policy goal was to ensure that individuals acquired higher levels of education and training (Banting, Reference Banting, Green and Kesselman2006). There was recognition of the particular challenges facing vulnerable groups, who were normally defined as single parents, recent immigrants, Aboriginal peoples and disabled Canadians. Critically, however, the policy goal was to nudge members of these groups into the paid labour force, and the growing inequality among paid workers was of little interest (OECD, 1994; Human Resources Development Canada, 1994, 2002). Moreover, one searches in vain through the major policy documents of the day for any discussion of the implications of retrenchment for racial minorities beyond recent immigrants or for the level of racial economic inequality in the country.

In parallel fashion, the politics of race has not been prominent in recent debates about the growth of inequality. During the 2015 federal election, the policy platforms of all major political parties included some reference to inequality, focusing especially on the middle class. The Liberal party, which won, promised to raise taxes on high-income earners, cut taxes for the middle class and significantly expand child benefits, which help low-income families most. Strikingly, there was virtually no mention of race and racial minorities during the election debates over such proposals. Indeed, there were few references even to “the poor.” Rather, in a detailed nine-page document, the Liberals presented their child benefits proposal as part of a larger package designed to help “the middle-class and those working hard to join it” (Liberal Party of Canada, 2015: 3). Many racial minority families with children, including recently admitted Syrian refugee families, were beneficiaries when the Liberal government went on to expand the Canada child benefits. However, racial inequality was not part of the larger politics that drove policy expansion. The debate was framed exclusively in universal terms, with an overwhelming concern about families as a general category.

Immigration policy and racial inequality

The transformation of immigration policy in the postwar decades reflects one of the hallmarks of Canadian liberalism. Policy changes in 1962 and 1967 “finally removed all explicit traces of racial discrimination from Canada's immigration laws” (Kelley and Trebilcock, Reference Kelley and Trebilcock2010: 357). The 1976 Immigration Act represented the “institutionalization of a universal admissions policy” and the new points system was “intimately linked to the liberalization of Canada's immigrant admission regime” (Triadafilopoulos, Reference Triadafilopoulos2012: 14–15). These changes marked a clear break from Mackenzie King's insistence in 1947 that immigration must not change Canada's demographic profile, and demographic change quickly followed. The new system opened the doors to non-European source countries and contributed to the emergence of a more racially diverse Canada.

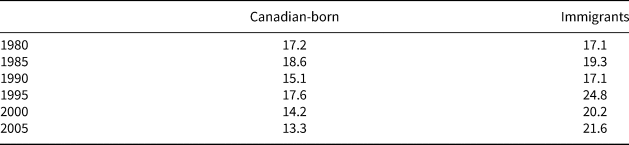

The new immigration policy was successful for several decades. Immigrants moved relatively quickly into the economic mainstream, and poverty rates among newcomers typically fell below the rate for the population as a whole within a decade or so. However, the economic integration machine began to sputter at the same time the immigration flow was becoming more racially diverse. Beginning in the 1980s, the incomes of new cohorts of immigrants started to decline relative to earlier cohorts, despite often having superior education and skills. The Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants found that only 40 per cent of skilled principal applicants who arrived in 2000–2001 were working in the occupation or profession for which they were trained, and many immigrants with university degrees were working in jobs that typically require high school diplomas or less (Banting et al., Reference Banting, Courchene, Seidle, Banting, Courchene and Seidle2007: 658). As Table 3 indicates, between 1980 and 2005, the poverty rate among immigrants was rising at the same time as it was falling among the Canadian-born population.

Table 3 Poverty Rates: Immigrants and Canadian-Born (%)

Source: Garnett Picot, Yuqian Lu and Feng Hou, “Immigrant Low-Income Rates: The Role of Market Income and Government Transfers,” Perspectives, December 2009, Table 1, Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 75-001-X. Poverty rates are after taxes and transfers.

Canadian governments focused intensely on the issue. However, they overwhelmingly framed the issue as a problem in the immigration program rather than a product of racial discrimination in the labour market. The dominant interpretation held that larger numbers of racial minorities came to the country in the 1980s and 1990s, just as economic growth in Canada began to slow and unemployment rates rose. New entrants to the labour force—including not only immigrants but also young white Canadians—bore the brunt of these pressures. In the case of immigrants, the situation was compounded by the limitations of newcomers’ language competence and difficulties in evaluating foreign credentials and experience (Alboim and Cohl, Reference Alboim and Cohl2012). Nevertheless, some part of the problem undoubtedly reflected racial discrimination in the labour market. Studies using resume experiments reveal patterns similar to those found in other countries: one study found that English-speaking employers in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver were about 40 per cent more likely to choose to interview a job-applicant with an English-sounding name than someone with a minority-coded name, even if both candidates had identical education, skills and work histories (Oreopoulos, Reference Oreopoulos2011). Yet in statistical analyses of immigrant economic outcomes, racial discrimination was, at best, referred to as an unmeasured “other” possible factor, often in a footnote. Racial discrimination was also largely absent from immigration debates, and the immigration department had few policy tools to tackle racial inequality.

Instead, policy makers responded by ramping up their existing tools. The federal and provincial governments launched programs to assist employers to assess foreign credentials, expanded language training and introduced work placements to give newcomers domestic work experience (Alboim and Cohl, Reference Alboim and Cohl2012). Even the Conservative government, which was generally committed to reducing public expenditure, dramatically increased federal spending on immigrant integration programs (Seidle, Reference Seidle2010). In time, however, it became clear that fixing the “problem” would require major state intervention in labour markets and even larger public spending on integration programming. Rather than choosing that path, federal governments fell back on traditional levers of immigration policy, shifting from integration to admissions policy, adjusting the rules governing who is admitted to the country. Language testing became much more stringent, the family reunification stream was narrowed further and regulations about who could sponsor a relative were tightened (Smith-Carrier and Mitchell, Reference Smith-Carrier, Mitchell, Béland and Daigneault2015). Most importantly, a pre-existing offer of employment became increasingly important for admission for economic immigrants, implicitly importing existing discrimination in the labour market directly into admissions criteria.

Immigration policy represents a case in which the state took serious action in response to growing inequality experienced by many members of racial minorities. However, governments never framed the problem as one of racial discrimination and economic inequality. They fell back on institutionally embedded ways of thinking about immigration policy and the tool kit available to immigration policy makers.

Multiculturalism policy and racial inequality

Canadians, especially in the anglophone parts of the country, have come to embrace multiculturalism as part of Canadian identity. Yet once again, this policy instrument was never designed to focus directly on issues of racial economic inequality.

The adoption of multiculturalism in 1971 was part of the sweeping liberalization that reshaped so many policies in Canada during the 1960s and 1970s. As in other policy sectors, the original multiculturalism policy of 1971 was introduced for a largely racially homogeneous population. The political pressure to act came from European immigrant groups, such as Ukrainian- and Italian-Canadians, who were already reasonably integrated economically but wanted greater recognition of their culture and contributions in a country dominated by British and French traditions and symbols. The policy was therefore designed to create space for state recognition and accommodation of diversity in state institutions and to give support to help individuals celebrate their cultural affiliations—what Kunz and Sykes (Reference Kunz and Sykes2007) have termed “ethnicity multiculturalism.”

Since then, multiculturalism policy has evolved in important ways. The arrival of racial minority immigrants in the late 1970s and 1980s broadened the focus. A policy that initially arose as an acknowledgment of long-settled white ethnic groups ‘‘became redefined as a tool for assisting the integration of new non-European immigrants” (Kymlicka, Reference Kymlicka2005). The Multiculturalism Act of 1988 embedded this wider approach, combining the preservation of culture and languages with a newer mandate of reducing racial discrimination. Nevertheless, the consistent thread running through the history of multiculturalism policy has been identity and the equality of cultures rather than the equality of incomes—as Charles Taylor (Reference Taylor and Gutmann1994) suggests, a politics of recognition.Footnote 6

Canadian multiculturalism policy is embedded in a wide range of government initiatives, including the constitution, school curricula, broadcast mandates, exemptions from some dress codes, dual citizenship and the funding of ethnic organizations. Despite the breadth of the policy, however, most discussion of the strategy refers to the last element: the grants to ethnic organizations, a tiny program that in the 2017–2018 fiscal year was budgeted for grants and contributions totalling $8.5 million—less than a rounding error in the federal budget. Nevertheless, the evolution of the grants program reveals much about the policy (Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban1998; Abu-Laban and Gabriel, Reference Abu-Laban and Gabriel2002). During the 1980s, some funding did go to local initiatives to counter racial discrimination. During the 1990s and 2000s, however, the orientation shifted toward a more explicit focus on integration in response to the failure of the Meech Lake Accord and the prospect of a second Quebec referendum on sovereignty. The 1991 Citizens’ Forum on Canada's Future called for a refocusing of official multiculturalism, with the key goal being “to welcome all Canadians to an evolving mainstream—and thus encourage real respect for diversity” (Canada, 1991: 129). This integrative push, triggered by the historic tension between English- and French-Canadians, easily displaced the short-lived focus on racial discrimination.

Multiculturalism policies have had important benefits, reducing the cultural costs of integration for immigrants and contributing to a more diverse sense of Canadian identity. However, multiculturalism has left critical racial issues unresolved. As we have seen, it focuses on cultural recognition rather than economic inequality. Even in its own terms, multiculturalism has had limits. Racial minorities remain underrepresented in the senior ranks of the federal public service and the judiciary, where only 30 of the 299 federal judicial appointments made between 2016 and 2020 was a person that identified as a visible minority (Griffith, Reference Griffith2020). There are racial disparities, especially for Black populations, in nearly every aspect of the criminal punishment system, including policing, the courts and incarceration (Chan and Chunn, Reference Chan and Chunn2014). Such exclusion impairs the integration of racial minorities into the Canadian mainstream. The weakness of the commitment to racial discrimination is also counterproductive. The experience of discrimination discourages the sense of attachment to Canada (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Schellenberg and Berry2016; Reitz and Banerjee, Reference Reitz, Banerjee, Banting, Courchene and Seidle2007), and racial minority immigrants participate in every aspect of political life less than do other immigrants (Gidengil and Roy, Reference Gidengil, Roy and Bilodeau2016). In Quebec, where multiculturalism has always had less traction, public debate continues to swirl around the boundaries of “reasonable accommodation” for religious minorities (Bouchard and Taylor, Reference Bouchard and Taylor2008). In 2019, the Coalition Avenir Québec government passed sweeping restrictions on religious dress, a provision that primarily impacts Muslim women. The uprisings following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, which spread to several major Canadian cities in the summer of 2020, also put a spotlight on the prevalence of anti-Black racism in Canadian society.

Multiculturalism lies at the foundation of Canadian national identity. However, the program reflects the historic centrality of ethnicity, culture and language in Canadian politics. As a result, critics worry that the celebration of a multicultural nationalism may convince Canadians that they live in a tolerant society, deflecting attention from the realities of racial economic inequality and the endurance of systemic racism (Thobani, Reference Thobani2007).

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms and anti-discrimination tools

The crowning achievement of postwar liberalism was undoubtedly the entrenchment of Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 and the emergence of human rights commissions at the federal and provincial levels. Section 15(1) of the Charter provides protection to equality rights and the right to “equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination, and in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age, or mental or physical disability.” In addition, Section 15(2) ensures that the Charter does not become a barrier to affirmative action, and Section 27 stipulates that the Charter “shall be interpreted in a manner consistent with the preservation and enhancement of the multicultural heritage of Canadians” (Canada, 1982). Armed with the Charter, the courts have provided redress against a number of discriminatory policies, especially against religious minorities (Eliadis, Reference Eliadis2014).

However, the Charter and the wider rights regime have not challenged the economic dimensions of racial inequality. The courts have consistently taken a very guarded approach to the idea of social rights and have declined to interpret the Charter as providing rights to welfare benefits. As a result, its anti-discrimination provisions offer no guarantees of racial equality in economic terms. Human rights commissions at the federal and provincial levels do extend protections against racial discrimination in the private sector in domains such as employment, housing and education. However, the reactive, complaints-based model, focused on retroactive redress for individual human rights violations, is limited in tackling systemic discrimination and racial economic inequality (Sheppard, Reference Sheppard2010).

More relevant is the Employment Equity Act of 1986, which established Canada's version of affirmative action. To avoid the controversy associated with American affirmative action programs, the legislation did not establish quotas or mandate the hiring or promotion of women, persons with disabilities, visible minorities or Aboriginal peoples. The only enforcement mechanism in the 1986 Act was a $50,000 fine that could be levied against employers that failed to submit annual reports to the federal government detailing the representation of these four designated groups in their workforce (Grundy and Smith, Reference Grundy and Smith2011). Technically, the legislation applies only to federally regulated industries, which together employ about 10 per cent of the Canadian workforce. The existence of similar legislation or programs at the provincial level is remarkably uneven, leaving substantial portions of the labour force uncovered (Bakan and Kobayashi, Reference Bakan and Kobayashi2000). The fact that most provinces do not have parallel legislation means that most employers are not covered. This weakness is partially mitigated by the Federal Contractors’ Program, also enacted in 1986, which requires larger employers wishing to bid on federal contracts or receive federal grants to develop employment equity programs designed to identify and eliminate discriminatory barriers. Revisions to the employment equity legislation in 1995 improved compliance provisions by giving the Canadian Human Rights Commission the authority to conduct audits and creating a tribunal to enforce compliance. In 1999, the commission found that many employers set goals that were lower than the labour force availability of the designated groups (Agócs, Reference Agócs2002). While the employment gap between men and women has largely dissipated over the past three decades, employment equity has failed to rectify the underrepresentation of racial minorities, Aboriginal peoples, and persons with disabilities, even within the federal public service (Weiner, Reference Weiner and Agócs2014).

The anti-discriminatory armoury of the Canadian state is impressive, but its individualist and universalist underpinnings hold limited promise for racial economic equality. The most powerful instrument, the Charter, does not directly address economic inequality, and the policy instruments designed to address systematic barriers, such as employment equity legislation, are relatively weak “soft law,” with few powerful enforcement tools. The Employment Equity Act is perhaps the clearest example of policy inertia, as a piece of legislation that was inspired by a clear call to action in the Abella Commission but has had only moderate success more than 35 years after its implementation. As Carol Agócs writes, employment equity had a solid design and rationale in Abella's recommendations, “but there were shortcuts and omissions as the house of employment equity was being built” (Reference Agócs and Agócs2014: 10). As a result, the legislation has not realized its transformative potential.

In sum, these four policy domains were initially constructed by a relatively racially homogenous Canada during the postwar era and institutionalized a liberal universalism, which continues to shape public policy in the more racially diverse Canada of today. Comparing across the fields reinforces the conclusion. Policy domains that wield the most potent policy tools, such as the welfare state and immigration policies, are shaped by the strongest universalist ethos. In comparison, policy domains that, by their very definition, confront racial inequality, such as multiculturalism policies and affirmative action policies, are constrained in one of two ways: either they are not designed to remedy the economic dimensions of inequality, as in the case of multiculturalism policies and the Charter, or when they are expressly designed to challenge economic inequality, they wield comparatively weak policy tools.

4. Conclusion

We began with the image of a puzzle. Why has the Canadian panoply of social policies not made more definitive progress in ending racial economic inequality? Undoubtedly, racial inequality would be even greater if these policies did not exist. In addition, on several dimensions, the Canadian record on the integration of immigrant racial minorities is quite impressive in comparison with other countries. However, progress relating to racial economic inequality and the persistent poverty among several large racial minorities is still embarrassingly limited. Moreover, the persistence of Canadian racial economic inequality is only truly puzzling if we were to assume the robustness of Canada's social model and completely disregard the long and peculiarly Canadian history of state-sanctioned racial discrimination.

Our answer to the puzzle is, at first glance, quite simple. The core social instruments of the Canadian state were never designed to tackle racial inequality directly. The major planks of the policy scaffolding were put in place when Canada was much less racially diverse, and social divisions defined in linguistic, cultural and regional terms loomed larger. More complicated is the question of why Canadian policy instruments have not been re-engineered to respond more directly to the racial inequalities that have now emerged. All the relevant policy fields examined here underwent serious restructuring in recent decades, but racial inequality was a marginal element in the politics of change. No frontal assault on racial economic inequality as such was debated, let alone adopted.

The second part of our answer is an institutionalist story of path dependency and policy inertia. More deeply, it is also a story rooted in the long-term political development of Canada, and the power of institutionalized modes of thinking about social programs and immigration policy. In their inspiration and design, the core postwar programs institutionalized the core assumptions of liberal universalism, and they continue to privilege universalist approaches to welfare, immigration, multicultural and human rights policy in the contemporary era. Together, these institutional and ideational factors have in some instances obscured the realities of racial economic inequality, and in others deflected attention away from problem definitions and concrete actions focusing on race toward more familiar approaches to diversity. While we do not deny that overt racism is an important and often overlooked aspect of the Canadian story, this interpretation provides a supplementary perspective that focuses on the institutional and ideational dynamics of Canadian political development. In fact, in many ways our analysis solidifies the very definition of structural or institutional racism, in that overtly racist intentions are not required in order for prevailing structures and institutional arrangements to leave racial hierarchies unchallenged, preserving the many advantages of white Canadians.

What would be the best way to enhance racial equality in the Canadian context? Given the impressive set of policy tools already in place, what is missing? In part, the best strategy would be to reinvigorate policy tools designed to reduce economic inequality among Canadians generally. Many of the policies introduced since 2015, such as the expansion of child benefits, provide the most help to low-income families—including poor racial minority families. This suggests that proposals framed in terms of helping lower-income Canadians generally will improve the socio-economic status of racial minorities.

However, a general strategy of reducing inequality among all Canadians, on its own, may not be sufficient to address the distinctive factors accentuating racial economic inequality. Policy tools specifically designed to problematize, target and alleviate racial economic inequality also seem needed. A more determined assault on racial discrimination in the labour market is important, as is a more ambitious model of human rights laws across the provinces and territories (Eliadis, Reference Eliadis2014: 259–61). Given the limitations of the current model of employment equity, a more aggressive approach toward “positive action” might be more effective. However, any explicitly race-based strategies in Canada must first traverse a political terrain full of landmines for reasons we have already discussed. Canadian liberalism values universalist principles, and in this paradigm, race is considered to be overly divisive. Canadians are not fully comfortable with either the terminology or politics of race.

The racially unequal impact of COVID-19 and the challenge of the Black Lives Matter movement have generated greater awareness of the reality of the many dimensions of racial inequality in Canada. Indeed, the federal government, along with some provinces and municipalities, responded to the uprisings of 2020 with dedicated anti-racism strategies. At this juncture, however, it remains to be seen how much this political climate and these new initiatives will change inherited ways of thinking about and responding to difference. Regardless, at some point in the future, if not now, political parties and governments will have to address issues of racial economic inequality openly and directly. The disconnect between our politics and our lived reality is growing too large to be ignored.