1. INTRODUCTION

The case of Carvalho before the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), also known as People's Climate Case,Footnote 1 is an example of private-public litigation, which denotes private claimants challenging public authorities and, more specifically, constitutes private-public litigation of a constitutional nature: the claimants strive for better legislation regarding climate change, invoking higher-ranking law which includes fundamental rights and international law.Footnote 2 The case is further characterized by being directed not against a state but against a community of states: the European Union (EU). Its subject, the effects of climate change, challenges settled case law in terms of both procedure and substance. It puts to test whether the standing requirements for direct access to the CJEU should be reinterpreted in view of the ubiquity of serious harm; discusses fundamental rights doctrine on questions such as causality, geographical reach, and justifiability of interferences; and examines the calculation and allocation of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions budgets derived from the limits for temperature increase set by the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.Footnote 3 Being a case report, the character of the following contribution is doctrinal rather than theoretical; in other words, it argues ‘within’ and not ‘about’ climate protection law and litigation. Some more theoretical observations nevertheless feature in footnotes.

2. APPLICANTS, DEFENDANTS, AND STAGE OF PROCEEDINGS

The Carvalho case was brought by ten families and an association representing other families, all of whom were engaged in medium-sized agriculture and tourism – that is, in occupational fields with a relatively direct exposure to the consequences of climate change. The families reside in northern Sweden, the German North Sea coast, southern Portugal, southern France, the Italian Alps, and the Romanian Carpathians, as well as in northern Kenya and on the island of Vanua Levu (Fiji). Their concerns, when cast in the terms of water availability, relate to risks and damage from insufficient water (with consequences ranging from drought to desertification), over-abundant water (sea-level rise, flooding and storms), or warm water (melting of glaciers, increased rain on snow). They also relate to the frequency and intensity of heatwaves.

The economic and health damage allegedly suffered by the applicants is evidenced in the application. The fact of actual damage to small-scale agricultural and tourism business distinguishes the case from others such as Urgenda v. The Netherlands Footnote 4 in which the claimants are non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and concerned citizens who defend a general interest but are not (yet) necessarily experiencing damage themselves.Footnote 5

The action is directed against the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers as legislative bodies of the EU. It was filed in May 2018 before the EU General Court,Footnote 6 within the prescribed two-month period following publication of the impugned legislative acts.Footnote 7 The defendants responded to the complaint, limiting themselves to the question of admissibility, to which the applicants replied.Footnote 8 In May 2019 the General Court dismissed the action on the ground that the applicants lack standing as they do not meet the requirement of individual concern as interpreted by settled case law.Footnote 9

Climate Action Network Europe (CAN-E) and Arbeitsgemeinschaft bäuerliche Landwirtschaft (AbL), an association of small and medium-sized farmers, have applied for leave to intervene in favour of the applicants, as has the European Commission in favour of the defence. The General Court postponed a decision on the intervention until a final decision on the admissibility of the action.Footnote 10

The applicants appealed against the order of the General Court. The defendants filed their responses in December 2019 to which the applicants replied in January 2020. The Commission was admitted as intervener on the side of the defence.

3. DISPUTED MATTERS

The subject matter of the dispute is the compatibility of three EU legal acts with fundamental human rights and international law. The challenged EU acts regulate GHG emissions from various sources for the years 2021 to 2030 and set an overall target that annual emissions in this period must be reduced by 40% relative to 1990 emissions levels. The overall target represents the reduction from three main emissions sources, each of which is subject to a separate act. The three acts, referred to here as the GHG acts, are:

1. Directive (EU) 2018/410 on the Emissions Trading System (ETS Directive).Footnote 11 The reduction required in this sector is 43% compared with 2005 levels by 2030, which derives from Article 9(2) of the Directive, according to which emissions shall decrease annually by 2.2% from 2021 onwards.

2. Regulation (EU) 2018/842 on Effort Sharing (Climate Action Regulation).Footnote 12 This applies to medium and small emitters in industry, transport, buildings, agriculture, and waste management. The required reduction by 2030 is 30% compared with 2005. This follows from Article 4 of Annex 1 to the Regulation, which sets a target quota for 2030 (which varies according to economic strength) for each Member State. It is to be achieved by annually available emissions quantities, which are reduced linearly for each Member State from the average of its emissions for the period 2016–18.

3. Regulation (EU) 2018/841 on Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF Regulation).Footnote 13 This applies to land-use changes that lead to emissions (such as deforestation and burning of wood) or to the loss of GHG sinks (as in the conversion of grassland to farmland). According to Article 4 of the Regulation, the target quota is net zero emissions (that is, a balance between emissions and removals by sinks). If more GHGs are removed from the atmosphere by sinks than are newly emitted by land-use change in a Member State, the surplus may be transferred to the effort sharing sector of the Member State and used to offset other emissions, although there is a cap for each Member State and an EU-wide cap of 280 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2 eq).Footnote 14

It is important to note for the legal assessment of the Carvalho case that the three acts, by setting an overall reduction target of 40% under 1990 levels in 2030, still implicitly permit the release of 60% of 1990 emissions in 2030. In 1990, EU emissions amounted to 5,654 Mt CO2 eq. Therefore, on this basis 3,392 Mt CO2 eq. will still be permitted in 2030. As discussed below, the applicants submit that this quantity is far too high and negatively impacts upon their livelihoods.

4. RELIEF SOUGHT

The purpose of the Carvalho case is to annul, pursuant to Article 263(1) and (4) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU),Footnote 15 the relevant provisions of the three GHG acts, as they allegedly enable emissions that go beyond what is permitted by higher-ranking law, which includes human rights and international law. However, since such annulment of the reduction targets would produce a legislative vacuum, while under Article 265(3) TFEU an injunction ordering the legislature to adopt more ambitious targets would be inadmissible,Footnote 16 the application makes use of Article 264(2) TFEU, which provides that the allegedly invalid provisions can be ordered to continue to apply until they have been revised in conformity with the higher-ranking law.

In addition to the request for annulment, the applicants seek a declaration, under Article 340(2) TFEU, for unlawful damage inflicted by the EU. As the applicants state they are not interested in receiving financial compensation but in preventing further damage, they request stricter emissions reduction measures to be ordered.

The following is a sketch of the applicants’ arguments: firstly, with regard to the action for annulment – beginning with its merits and followed by its admissibility – followed by the aspect of non-contractual liability.

5. MERITS OF THE ACTION FOR ANNULMENT

The application for partial annulment of the three legal acts would be justified if higher-ranking law demands greater reduction than the EU's planned 40% below 1990 levels in 2030, or, in other words, lower emissions than the 60% of that baseline still allowed by the three acts.

5.1. Higher-Ranking Law

The legal yardsticks against which the applicants argue that the EU acts should be judged comprise fundamental rights and international legal principles.

5.1.1. Fundamental Rights

The rights in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU (EU Charter)Footnote 17 invoked by the applicants include the rights to life and physical integrity (Articles 2(1) and 3(1)), to pursue an occupation (Article 15(1)), to property (Article 17(1)), to equal treatment of young people and people living in developing countries (Article 20), and to the welfare of children (Article 24(1)). The case raises a number of doctrinal and interpretative questions cross-cutting the various rights.

Firstly, it must be clarified whether the fundamental rights are to be applied as ‘rights of defence’ against sovereign intervention or as ‘rights to protection’ against damage caused by private persons. The fact that GHG emissions ultimately originate from private actors speaks in favour of the right to protection. In contrast, the fact that the GHG acts provide for the allocation of emissions allowances by EU institutions can be construed as sovereign intervention in the fundamental rights of those affected.

The application primarily follows the latter construction, pointing to the wording of the relevant laws. According to the ETS Directive, the Commission allocates annual emissions allowances to Member States, and the latter proceed to distribute them to the actors by auction or free of charge. Similarly, under the Climate Action Regulation the Commission annually allocates certain emissions quantities to Member States, which the latter manage through sectoral measures. Somewhat differently, the LULUCF Regulation does not provide for annual allocations, but sets a target value to be achieved annually, namely, net zero emissions. This means that Member States may emit as much by land-use change as is removed by sinks. The application argues that the quantity emitted should be understood as being permitted by the LULUCF Regulation. In the alternative, the application puts forward fundamental rights as constituting a right to protection against emissions from private actors. This is a difficult argument to maintain, as the CJEU so far has not developed a doctrine of fundamental rights to protective measures to any significant extent.Footnote 18

A second question is whether the fundamental rights protection extends to the applicants living in Kenya and Fiji, located outside the EU. The application makes several arguments in support. These include that the EU Charter phrases the relevant rights neutrally in terms of personal or geographical scope;Footnote 19 that this is common practice in national environmental law, and may be based on the constitutional principle of open statehood.Footnote 20 International human rights have also been interpreted in the transnational sense of territory and jurisdiction being distinguished, so that citizens living outside a territory may still come within the jurisdiction of states of origin of environmental harm.Footnote 21 In the EU, large companies situated in third countries have been accepted to rely on freedom of trade and fundamental rights to occupation, property, and protection of legitimate expectations.Footnote 22 The action argues that foreign small and medium-sized farmers and tourism providers should also come within the reach of fundamental rights if they are adversely affected by emissions that originate in the EU and are authorized by EU acts.

A third question concerns the kind of causality required to prove an interference with fundamental rights.Footnote 23 The chain from the allocation of emissions allowances to the damage suffered by the applicants is long. As explained by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), it runs through complex systemic processes of wind and sea currents. Nevertheless, a chain of causation in a factual sense from emissions to damage is considered ‘extremely likely’.Footnote 24 The application treats the length of the chain as irrelevant as long as causality is provable.Footnote 25 It also interprets fundamental rights in the light of the objective obligation to ensure a high level of environmental protection, pursuant to Article 37 of the EU Charter and Article 191(2) TFEU.

The existence of a general fundamental right to a healthy environment, as already established by 100 or so states,Footnote 26 might have helped the applicants in this respect, but EU primary law does not contain such right. The applicants maintain that it is in any event not indispensable to their case, because the specific fundamental rights they invoke can be interpreted to extend their protective scope to those climatic conditions that are necessary for the exercise of a right.

Finally, and most importantly, if an interference with fundamental rights is to be affirmed, the applicants concede that it may still be justified in view of overriding conflicting interests.Footnote 27 These can be public or private interests,Footnote 28 such as an interest in energy security or employment. The conflicting interests must be weighed against the interests in climate protection. If the former are considered substantial, the proportionality principle applies (Article 52(1) of the EU Charter), meaning that their interference with the fundamental rights must be limited to the minimum necessary to safeguard the overriding interests. The applicants understand this to mean that GHG emissions must be reduced as far as is technically and economically feasible.

5.1.2. International Law

The Paris Agreement is particularly relevant to the application. It aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by ‘[h]olding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C’ (Article 2(1)). Because of its instrumental role (‘aims to strengthen’) and the indicative formulation (‘by holding’), the target expressed as ‘well below 2°C’ can be regarded as binding on the contracting parties, not only because of its form as an international treaty, but also because of the meaning of the relevant wording.Footnote 29 Well below 2°C has been proposed by scientists to mean 1.8°C.Footnote 30

The application claims that 2°C represents the unconditional upper limit that must be met with high likelihood.Footnote 31 This may be contested by the defendants in view of Article 4(1) of the Paris Agreement, which states that the emissions reductions should achieve a balance between emissions by sources and removals by sinks only in the second half of the century. They might read this to mean that emissions overshooting 2°C on the way to 2050 will be allowable if they finally reach a net zero balance after 2050. However, Article 4(1) of the Paris Agreement can be understood alternatively to allow that parts of the emissions budget continue to be expended for some time even after 2050 without overshooting 2°C.

A further challenge to the argument of the binding force of the upper limit are a number of provisions of the Paris Agreement on the ways in which this goal is to be achieved. These include the following:

• the global peak in emissions should be reached as soon as possible (Article 4(1));

• the state parties thereafter are to bring about rapid reductions (Article 4(1));

• the parties are to declare and implement nationally determined contributions (NDCs) (Article 4(2)) that reach the ‘highest possible ambition’, taking into account common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities in the light of different national circumstances (Article 4(3));

• developed countries should continue to lead and commit to emissions reduction targets, but developing countries should also move towards such targets; and

• the principle of equity is to be the basis both for holding the temperature limit to 2°C (Article 2(2)) and for taking reduction measures (Article 4(1)).

Although these conditions are intended to ensure compliance with the global warming limit, they appear not to be designed in such a way that the objective is imperatively achieved. This is because they contain elements of voluntariness (ambition in the first round of NDCs) and exhortation (‘should’) rather than obligation (‘shall’). There is thus a seeming lack of fit between the arguably binding temperature limit and the more flexible prescriptions for how to stay below it. Climate law doctrine has hardly addressed this question.Footnote 32 The application suggests that the inconsistency could be resolved in two ways:Footnote 33

1. The conditions are construed as being distributive and the objective as being compulsory. This means that the conditions are addressed to all participants as a collective. Their application may not result in an amount exceeding the limit (strictly capped distribution).

2. The conditions are construed as being relational and the objective as being non-binding. This means that the conditions are addressed to the individual contracting parties in relation to each other; their application results in a sum (emissions budget) that is not strictly capped by the temperature limit, so that the limit serves only as an orientation (flexibly capped distribution).

To illustrate, assume one loaf of bread which must be shared among a number of people experiencing various degrees of hunger. In the first model the individual eater must calculate her share with reference both to the size of the loaf and the needs of the others, which means that all involved must cooperate in order to develop a common strategy. In the second model the pressure to cooperate is less because more loaves can be added. Game theory suggests that only the first model will adhere to the budget, while in the second model participants will act selfishly and neglect later collective damage.Footnote 34

The application combines both models by proposing a two-stage examination which mirrors that of the two-step test involving certain fundamental rights. The first stage serves to specify and apply the level of protection resulting from the 2°C limit; it determines which emissions budget is still available and how it is to be distributed among states (including the EU) in accordance with international distribution criteria. As will be explained below, the core criterion here is the principle of equal treatment. At the second stage, the conditions reappear as discrete requirements directed at individual states. This involves taking into account national interests that are jeopardized by drastic emissions reductions. At the second stage, failure to comply with the 2°C upper limit is accepted. The core condition is the technical and economical capability to reduce GHG emissions.

The first stage corresponds to the test of encroachment on fundamental rights. It must, however, be noted that the levels of protection provided by fundamental rights and international law may be different. Fundamental rights are commonly construed to provide a high level of protection, because any burden that is not insignificant can be regarded as constituting an encroachment. The level of protection under the Paris Agreement is then lower because it accepts (as a last resort) damage caused by warming up to the limit of 2°C.Footnote 35

Climate law doctrine has failed to clarify how this conflict of two levels of protection can be resolved. There are two possible constructions:

1. Fundamental rights are not relativized by international law. They protect right-holders against any significant damage.Footnote 36

2. Fundamental rights are to be accommodated to international law. Damage caused by warming up to 2°C is not deemed as encroachment.

The application primarily adopts the first construction. The second is proposed as an auxiliary alternative.

The second stage of applying the Paris Agreement, with its reference to respective capabilities, coincides with the second stage of applying fundamental rights where examination is made of whether legitimate encroachments on rights are minimized according to the technically and economically feasible.

5.2. Application of the Higher-Ranking Law to the Three GHG Acts

5.2.1. Interference with Fundamental Rights and Exceeding the Paris Budget

The application claims that, by allowing damaging emissions, the three GHG acts interfere with the fundamental rights of each of the applicant families. The affected rights are those to health, occupation, property, and the welfare of children. The fact that the damage to the applicants and risks of damage were caused by anthropogenic climate change has been demonstrated by experts in climate science and was acknowledged by the EU General Court, at least insofar as interference at the admissibility stage was concerned.Footnote 37 It is also claimed that the children are discriminated against because the present adult generation emits more than they will be able to emit, and that people in developing countries are treated differently from those in the EU because they suffer from climate change effects that were caused primarily by industrialized states.

The application concedes, in the alternative, that the Paris Agreement legally adjusts the level of protection of fundamental rights, so that an encroachment can only be assumed from global warming above the 2°C limit. It considers this to be a significant concession because significant damage can be expected from temperature rises below that limit.Footnote 38 It asserts, however, that even the 2°C limit will be exceeded by the emissions still allowed by the three GHG acts. The argument is based on a calculation consisting of three steps: (i) determination of the global budget of allowable emissions; (ii) its distribution among the states, including the EU; and (iii) the ways in which the budget may be spent.

The defendants have not responded to this reasoning so far, confining themselves to challenging the admissibility of the application. It is likely, however, that they will point to uncertainties that arise in deducing emissions budgets as well as propose their choice of principles of distribution and ways of spending any assigned budget.

Determination of the available global budget

The application bases its calculation on the IPCC Report of 2014. Assessing a broad range of climate models, the Report estimated the global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions budgetFootnote 39 available from 2011 if the global warming limits were to be met. It found that 1,075 gigatonnes of equivalent carbon dioxide (Gt CO2) could still be emitted while remaining within the 2°C limit.Footnote 40 If a limit of 1.5°C was assumed, the budget amounted only to about 575 Gt CO2. These are mean values resulting from a wide dispersion caused by the different design of models, spanning from 750 to 1,400 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 550 to 600 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C.Footnote 41

The 2018 IPCC Report on global warming of 1.5°C calculates the global budgets of CO2 emissions to be larger by about one third.Footnote 42 However, it states that the 2014 and 2018 estimates are not directly equivalent because they deploy different parameters. The 2018 Report also notes that its calculated budgets must be reduced considering earth system feedbacks such as permafrost thawing as well as radiative forcing by non-CO2 emissions.Footnote 43 The application, which was submitted in May 2018, could not refer to the new calculations released in October 2018. Which figures – those of the 2014 or 2018 Reports – are considered decisive by the CJEU will depend on whether the case proceeds to the merits. It could be that the Court hears experts on the issue. When assessing expert opinions, it will need to develop law-based criteria for judicial review of the science-based models representing causal nexus between GHG emissions and harmful effects as well as between abatement measures taken and emissions reductions.Footnote 44 This is a particularly demanding task in a situation where differences in budget estimations have far-reaching implications for damage predictions and normative conclusions.

The calculation of emissions budgets unavoidably includes uncertainties which are disclosed and expressed as degrees of confidence or probabilities of error. With regard to the budgets of IPCC 2014, their compliance with the 2° and 1.5°C limits is estimated as having a 66% probability for 2°C and 50% for 1.5°C. It is an open field of legal enquiry what probability should be demanded for predictions of safety and risks. The applicants submit that 66% and 50% present a very low probability of staying within the temperature limits (or rather, a high probability of failing to do so). Were a higher probability of staying within the limits demanded, the available budgets would be much smaller.

In that vein, the application claims that the lower values of the range of models should be taken as the global budgets that are available for further distribution. This may raise opposition from the defendants. The application bases its contention on the precautionary principle enshrined in Article 191 TFEU. Indeed, precaution has been interpreted to require a ‘conservative’ assessment, meaning that between different assumptions about risks the safer one will be chosen, as long as the conservative choices do not compound.Footnote 45 In effect, therefore, the application claims that the global budget available in 2011 should be estimated to have been 750 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 550 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C.

While, as indicated, the IPCC-based budget is calculated for 2011 onwards, the quantities that have since been emitted and will still be emitted up to 2020 are to be deducted in order to achieve the budget that will be available in 2021, the year at the start of the decade covered by the three EU GHG acts. The application does this by referring to data that is available for emissions from 2011 to 2016, and extrapolating to 2020 based on recent trends. This results in a global budget available in 2021 of average quantities of 667 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 167 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C within a range of 342 to 992 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 142 to 192 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C. The lower budgets of 342 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 142 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C are the precautionary values postulated in the application.

Allocation of the overall budget

The principles of the Paris Agreement can be used as distributive criteria for the allocation of the allowable global budget to participating states.Footnote 46 As indicated above, the approach starts with the strictly capped model, which means that the sum of quantities allocated may not exceed the global budgets.

The principles are summarized in Article 2(2) as follows: ‘This Agreement will be implemented to reflect equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances’. These principles suggestFootnote 47 five criteria of budget allocation which have also dominated the related international policy discourse.Footnote 48 They comprise: (i) grandfathering; (ii) the right to development; (iii) respective capabilities; (iv) historical equal per capita; and (v) actual equal per capita.

• Grandfathering: This approach would allow states to continue to emit the same quantities as they did before. With an annually shrinking global budget, the percentage of large emitter states would then increase. That would neither be politically defensible nor legally compatible with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR).Footnote 49 Alternatively, the approach could be understood as allowing states to maintain their percentage of the global budget. If applied to industrialized states, this approach would at least lead to a reduction in absolute emissions along with the shrinking global budget. If 1992 is taken as the reference year, with the EU causing at least 10% of the global emissions in that year,Footnote 50 the EU could claim the same percentage of the remaining budget. Calculated as 167 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 112 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C, this budget will have been spent within 33 years from 1992, namely by 2025, for the 2°C target. Maintaining the 1.5°C target, the budget would have been spent within 22 years, namely by 2014.

• Right to development: This principle, which is implicated in CBDR, would allow developing states to increase their percentage according to their development needs. If taken to mean that all states will be able to reach the level of industrialized states, the entire global budget would have to be reserved for the developing and emerging states. No share would be available for the EU.

• Respective capabilities: This principle, which is explicitly mentioned in Article 2(2) of the Paris Agreement, refers to the technical and economic potential of states. Capability has often been represented by the relative gross domestic product (GDP) of a country.Footnote 51 By contrast, the application claims that in legal terms capability means that more complex parameters must be considered.Footnote 52

• Historical equal per capita: According to this principle, which is closely related to the equity principle, every single person is owed the same share in the budget. The budget of a state would then correspond to the size of its population. Historical (or cumulative) per capita means that the starting year for allocation is dated back to a significant moment in history. The year of reference could be 1992, the year of adoption of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),Footnote 53 when the world community officially and unanimously acknowledged the climate effects of anthropogenic GHG emissions and agreed to an obligation to reduce emissions. The global budgets available in 1992, still based on the temperature limits of 2°C and 1.5°C, can be calculated by starting from the budgets available in 2011, as proposed by the IPCC,Footnote 54 and adding to these the historical emissions from 1992 to 2010. The latter emissions amount to 595 Gt CO2, which means that the global historical precautionary budgets in 1992 amount to 1,670 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 1,120 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C respectively.Footnote 55 If these budgets are taken as reference and a share is hypothetically allocated to the EU according to the per capita criterion, which was 6.5% in 1992, the EU share would be 107 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 73 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C. Given the EU's annual emissions of approximately 5 Gt CO2 these shares would have been spent by 2013 or 2007 respectively. No further emissions would be allowed if this criterion was applied.

• Present equal per capita: According to this principle the per capita share is related to the present time or, in terms of the time span addressed by the three GHG acts, to the year 2021.

The application claims that the present equal per capita principle should be preferred, because it corresponds well to the equity principleFootnote 56 and even more so to the equal treatment rule in Article 20 of the EU Charter.Footnote 57 This means that the EU can claim a share of the global budget which corresponds to its share of the world population, which is forecast to be about 6.5% in 2021.Footnote 58 When multiplied with the average available global budget, the EU share as of 2021 amounts to 43.4 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 10.9 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C. When multiplied with the precautionary lower global budget, 342 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 142 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C, the EU share amounts to 22.2 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 9.2 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C.

Use of the EU budget

The budgets must be divided into annual portions. In 2020 the actual emissions level will be 80% of 1990 emissions, which is 3.38 Gt CO2. The annual emissions volume must be reduced year by year and reach net zero at some later point in time. Hence, the use of the entire EU budget must be regressive. The application suggests three alternative trajectories for such regression: convex, concave, and linear:

• Convex: During the first years much of the budget is used (low mitigation effort), so that a steep drop must take place later. Such a curve shifts the mitigation problem to later years. It accepts that heavy damage is caused in the interim, and puts future society under enormous pressure to make immediate reductions and efforts towards adaptation. This approach is also a risky bet on the ability of future technologies to mitigate emissions rapidly.

• Concave: Drastic emissions reductions are made immediately, so that a small margin remains for later years. The pressure to act is immediate. This approach mitigates future risks but is politically more difficult to implement.

• Linear: Every year the emissions quantity is reduced by the same percentage.

Reviewing the three trajectories in the light of the legal principle of prevention in Article 191 TFEU, the application argues that emissions reduction measures should be taken as early as possible. It also understands the fundamental rights in the EU Charter to equal treatment (Article 20) and children's welfare (Article 24) to prohibit older generations from consuming resources to the cost of younger generations. It claims that the first trajectory does not meet these standards. The second option would be politically preferable but will cause tension with conflicting fundamental rights of those who will have to be forced drastically and immediately to reduce their emissions. The application therefore suggests that the third trajectory represents the minimum required. Moreover, linear regression is also the concept adopted in the ETS DirectiveFootnote 59 and the Climate Action Regulation.Footnote 60

It can be expected that the defendants will not dispute this. Opinions, however, will differ as to the steepness of the regression, which affects in how many years the budget will be consumed. This much depends on whether (as the applicants argue) the precautionary budget or (as the defendants are likely to argue) the average budget will be assumed.

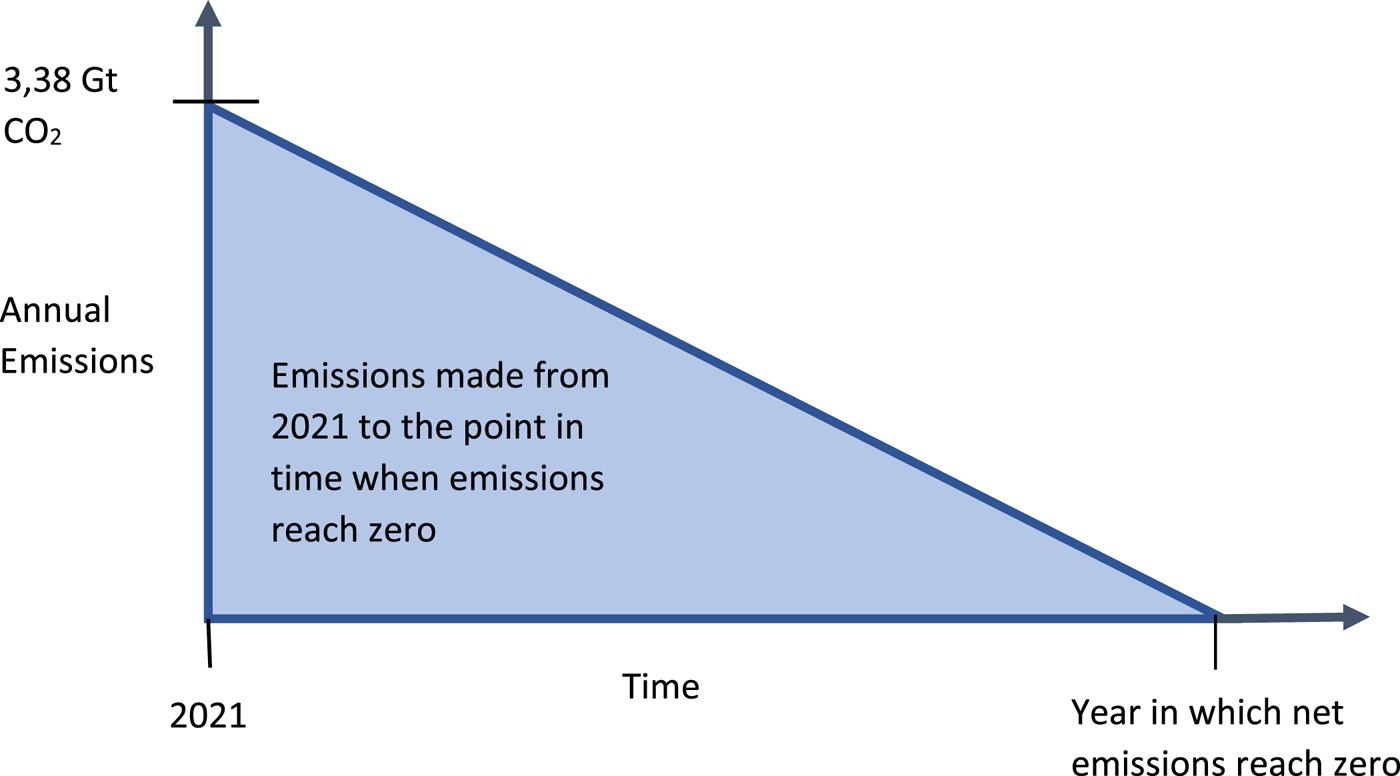

Assuming either the precautionary or average EU budget, the steepness of regression derives from a simple calculation based on the formula for a right-angled triangle. Such triangle consists of an area (A), the vertical axis (y), and the horizontal axis (x), all together represented by the formula A = x*y/2. In the present context A (= the budget) and y (= the emissions quantity in the starting year 2021) are given, with A amounting to 43.4 or 10.9 Gt CO2 (average values) and y to 3.38 Gt CO2 in 2021. The value of x can be determined with the formula x = A/y*2 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Calculation of Linear Regression of Emissions by Triangulation

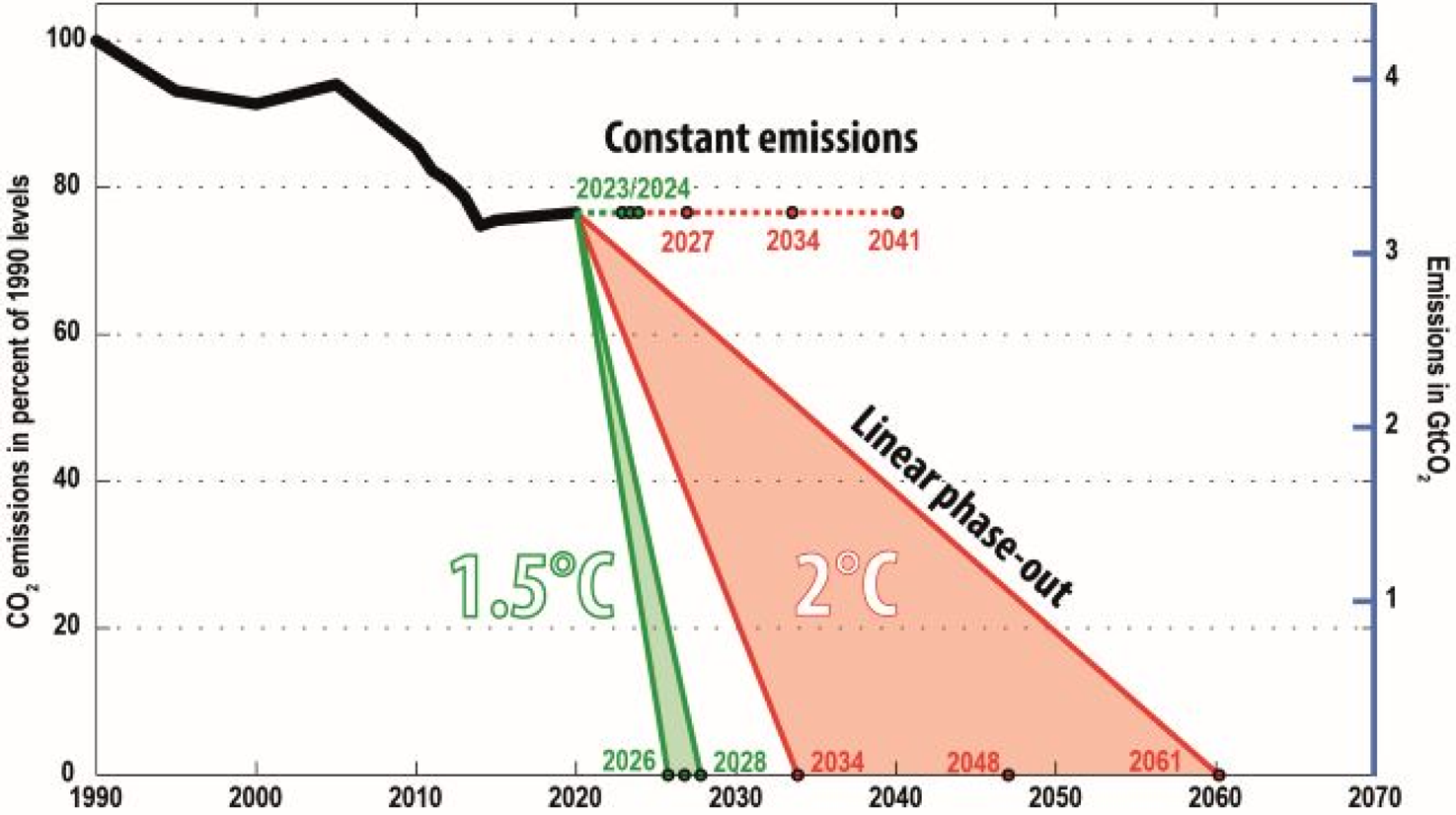

On the basis of this calculation, EU budgets for 2°C will be exhausted in 2048 and for 1.5°C in 2028, which implies that emissions must be net zero by these years. Based on the precautionary budgets – namely 22.2 Gt CO2 for 2°C and 9.2 Gt CO2 for 1.5°C – net zero must already be reached in 2034 for 2°C and 2027 for 1.5°C respectively.

Following the precautionary approach, the application claims that in 2030 only 20% of 1990 emissions will be permitted under the 2°C limit and no net emissions at all under the 1.5°C limit. Emissions therefore would have to be reduced by 80% or 100% by 2030. These trajectories are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Scenarios of CO2 Emissions, including Land Use, for the EU Allocated from 2021 Using the Equal Per Capita Approach, based on the EU Population Share in 2020

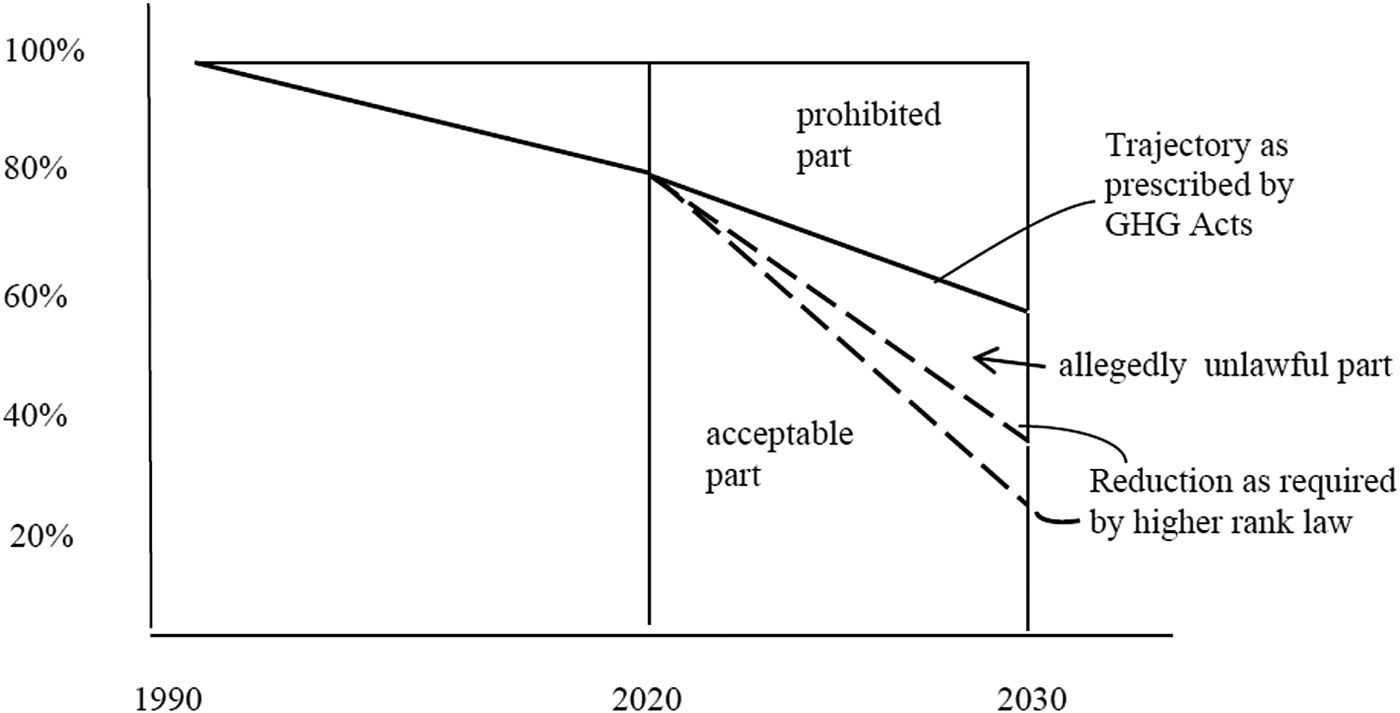

Applying this result to the three GHG acts, the application stipulates that the GHG acts with their reduction target of 40% stay far below the target of 80%. In other words, with the 60% they permit, they significantly overshoot the 20% which would be permitted in compliance with the Paris Agreement and EU fundamental rights (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Trajectories of GHG Emissions from 1990 via 2020 to 2030, as Prescribed by the Three GHG Acts and Allegedly Required by Higher-Ranking Law

5.2.2. Justification for Interference with Fundamental Rights and for Exceeding the International Budget

The application concedes that both the alleged interference with fundamental rights and exceeding the internationally allowed budget may be justified by public and legitimate private interests provided that the interference/excess is reduced in accordance with technical and economic capabilities. At this second step, a relational understanding applies, as explained in Section 5.1.2. This means that the feasibility criterion may be applied with individual reference to the EU without having to comply with the 2°C or 1.5°C limits.

The application does not propose its own analysis of the EU's technical and economic capability, anticipating that this would be regarded by the CJEU as being within the political discretion of the defendants. Instead, it claims that the EU legislature did not develop or apply a comprehensive and consistent methodology of capability analysis. The application does not qualify this shortcoming as a failure to give reasons in the sense of due administrative procedure, considering that the CJEU does not impose strict requirements on the obligation of EU institutions in that respect,Footnote 61 and especially not in the case of legislative acts.Footnote 62 Rather, the failure to develop and apply a sound method of analysis is alleged as a procedural dimension of the substantive requirement of doing what is feasible.

The application argues that a sound methodology would be required to examine – from the bottom up – all source sectors of GHG emissions in depth. It alleges, instead, that the 40% reduction target to 1990 levels was introduced haphazardly, following political numbers games rather than empirical study. It was established as an interim target in an entire reduction trajectory of 8% by average between 2008 and 2012 (EU-15), 20% by 2020, 40% by 2030, 60% by 2040, and 80 to 95% by 2050. This overall trajectory was adopted by the Environment Council in 2009,Footnote 63 substantiated by the Commission in 2011Footnote 64 and in later communications,Footnote 65 and supported by the European Council in 2014.Footnote 66 In a comprehensive impact assessment, the Commission found that the objective could be achieved without major costs.Footnote 67 This led to proposals for the three GHG acts, each of which were the subject of separate impact assessments.

The application submits that these impact assessments ask whether a politically assumed quota is feasible instead of asking which quota is feasible. They therefore ignore more ambitious targets than the assumed 40%. Their focus is on whether the costs of emissions reduction were substantial, but not what costs are bearable and how they can be made good by economic opportunities from new energy economics and by the avoidance of costs from climate change effects. The reduction potential of some sectors was highly underestimated, including, in particular, intensive agriculture, land use, transportation, and product design. Completely neglected was the sufficiency factor, which relates to changes in and reduction of consumption.Footnote 68

The application further argues that the feasibility of stronger emissions reductions has been demonstrated by a whole series of expert reports that were not taken into account by the impact assessments. Generally, the expert reports only vary individual parameters (for example, the speed of transition to renewable energy sources) which already leads to reduction rates of 45 to 60% in 2030 compared with 1990 levels. If all parameters were combined, the quota would be even higher.Footnote 69

The application alleges that an overall reduction by 2030 of 50 to 60% of 1990 levels, or a remaining quota of 40 to 50%, would be technically and economically feasible. It argues that, in consequence, the target of the three GHG legal acts – 40% reduction with 60% remaining emissions – is not as ambitious as higher-ranking law requires. Therefore, the three GHG acts must be declared null insofar as they prescribe how the reduction targets are to be calculated.

6. ADMISSIBILITY OF THE ACTION FOR ANNULMENT

The action is directed against legislative acts. Pursuant to Article 263(4) TFEU, in such cases the applicants must be directly and individually concerned by those acts.Footnote 70

The General Court denied that the applicants are ‘individually concerned’ in the settled interpretation of the term, following the defence on the issue. It left open whether the applicants are ‘directly concerned’, which was also disputed by the defence. The applicants have appealed against the Court order. The case is now pending before the European Court of Justice (ECJ).Footnote 71

6.1. Direct Concern

CJEU jurisprudence has defined ‘directly concerned’ as follows:

According to settled case law, for an individual to be directly concerned by a European Union measure, first, that measure must directly affect the legal situation of that individual and, secondly, there must be no discretion left to the addressees of that measure who are responsible for its implementation, that implementation being purely automatic and resulting from European Union rules alone without the application of other intermediate rules.Footnote 72

These two requirements will be addressed in turn.

6.1.1. Direct Effect on the Legal Position of the Applicants

The three GHG acts allocate emissions allowances to EU Member States, thereby allowing annual emissions from up to 80% of 1990 levels in 2020 to up to 60% in the target year 2030. The applicants claim that the allocation and allowance of a part of this quantity breaches higher-ranking law, namely, the part which consists of the difference between the allocated 60% and the feasible 40–50%. The allowances therefore breach higher-ranking law by between 10 and 20% of 1990 values.

The defendants may reason that the emissions ultimately emanate from private actors, not directly from the three GHG acts or any implementing decisions. The applicants object that allocating and allowing emissions of this quantity has direct effect on the applicants’ basic rights, because the assignment of emission rights to emitters at the same time imposes an obligation on them to tolerate the emissions. They argue that the fact that the Commission and the Member States decide on the allocation in detail is irrelevant to the existence of such imposition. In support, the application refers to similar legal scenarios. One is subsidy law. If company A contests the Commission's approval of financial aid to company B, A is accepted to be directly concerned in its legal position by this very approval (individual concern being presumed), although it is not yet completely certain that the Member State concerned will actually pay the aid and whether said aid will actually change the competitive situation. The application concedes, however, that realization of the approval must be likely. In the given scenario of allocation of emission rights it asserts this to be the case, because experience to date has shown that EU Member States do fully exploit or even overshoot their assigned budgets.

6.1.2. No Discretion in Implementation

Implementation of the three GHG acts is the responsibility of the Commission and the Member States. The application claims, not disputed by the defendants, that the Commission has no discretion to allow or reduce more emissions than that provided by the reduction quotas of the three GHG legal acts. Similarly, Member States are not entitled to allow more emissions than those assigned by the GHG acts. In contrast, they have the right, on the basis of Article 193 TFEU and based on the conception of the GHG legal acts as a minimum harmonization, to allow fewer emissions than are allocated to them. However, in opposition to the defendants’ submission, the application understands this to be irrelevant for the present case because the same challenges the ‘European Union measure’,Footnote 73 not the right to go further or any pertinent national regulation. The application is not aimed at exploiting such national discretionary margins, but at achieving stricter reductions by a prescription in the EU GHG acts themselves. It argues that this is all the more warranted because the applicants are not only affected by the emissions of their respective Member States, but by all EU emissions. These, it claims, can effectively only be controlled by EU law.

6.2. Individual Concern

According to settled case law of the CJEU, persons to whom the contested act is not addressed are considered to be ‘individually concerned’ if the act concerns them ‘by reason of certain attributes which are peculiar to them or by reason of circumstances in which they are differentiated from all other persons or [if the act] by virtue of these factors distinguishes them individually just as in the case of the person addressed’.Footnote 74 This definition is known as the Plaumann formula.

The application argues that, from a comparative perspective, the requirement of distinctiveness displays a rather narrow conceptualization of standing. Most states provide more liberal avenues to court review of governmental action, no matter whether they adopt a de facto or a de jure concept.Footnote 75 The Plaumann formula has traditionally been understood to refer to de facto concerns. More recently it has been applied in acknowledging that subjective rights may also count as those affected.Footnote 76 There is still lack of clarity about whether both approaches apply alternatively or cumulatively. The present case may be an opportunity to further develop the EU concept.

The application and appeal take a two-step approach. They first insist that the Plaumann formula is indeed met, and, in the alternative if the ECJ does not accept this, that the formula should be revised. In first order the application and appeal submit that the three GHG acts do concern the applicants, de facto, in distinctive ways. For example, one applicant family has lost its forest from heat-caused wildfires; another experiences soil degradation on his farm as a result of droughts and sudden torrential rain; the property of a third family is exposed to sea-level rise and tornados; a fourth sees her reindeer herds starving as a result of scarified snow conditions. In addition, the application and appeal plead individual concern also in the de jure sense. They claim that the encroachment on the claimants’ fundamental rights is distinctive per se because any fundamental right must be protected no matter how many persons are affected.

In contrast, the defendants objected and the General Court agreed that neither the de facto effects nor the interference with fundamental rights distinguish the claimants from any other person.

In the alternative, if the General Court and eventually the ECJ deny individual concern in the Plaumann understanding, the application and appeal request a revision of the formula itself. The General Court rejected this claim, reasoning that any other interpretation of ‘individual concern’ would render the requirements of Article 263(4) TFEU meaningless and entail the risk that locus standi would be created for all.Footnote 77 The Court also reacted to the applicants’ objection that such denial of standing would hamper their right to seek review of the legality of EU legal acts (Article 47 of the EU Charter). Repeating established CJEU jurisprudence, the General Court held that while the Plaumann concept of standing may hinder direct access to the EU courts, indirect access would still be available, with the combination of direct and indirect access forming a differentiated but complete system of legal protection. Indirect access would be available either through appeal against implementing acts of the Commission, which entails incidental testing of the legality of the underlying legislative acts (Article 277 TFEU), or through appeal against Member State implementing acts that might lead to submissions for a preliminary ruling on that same question (Article 267 TFEU).

The application and appeal object to this reasoning on the basis of six grounds:

1. Common sense suggests that an indeterminate term like ‘individual concern’ can be interpreted in various ways so that interpretations other than the Plaumann formula do not render it meaningless.

2. The CJEU is bound to interpret the treaties in accordance with the constitutional traditions of the Member States (Article 6(3) of the Treaty on the European Union (TEU)).Footnote 78 While all Member States impose an individual standing requirement for access to judicial protection against emanations of public power, none requires an applicant to show individual distinctiveness in the narrow sense of the Plaumann test.

3. The standing requirement must be interpreted teleologically to exclude the perverse effect that the more serious the damage, and hence the more persons are affected, the less access to courts is provided.

4. It is the very rationale of legislative acts to treat all addressees in general rather than in individually distinctive ways. The Plaumann test therefore excludes any direct access to the CJEU aimed at reviewing the legality of EU legislative acts although Article 263(4) TFEU does provide this.

5. Indirect access through action against implementing acts of the Commission (with a view to obtaining an incidental check of the underlying GHG acts via Article 277 TFEU) is not available because (as they themselves will entail Member State implementation) they will be confronted with the same Plaumann test, and fail.

6. Indirect access through action against Member State implementing acts (with a view to obtaining a preliminary ruling on the validity of the GHG acts via Article 267 TFEU) is also not available. A submission to the CJEU would be inadmissible because, based on Article 193 TFEU, the Member States are entitled to further reduce the EU emissions reduction targets. The national courts would have to answer requests to order this by applying national fundamental rights.Footnote 79 If the applicants nevertheless want to demand a reduction of the entire EU GHG emissions budget, they would need to file complaints before the courts of all 27 Member States. This would be an unbearable burden in terms of the guarantee of legal protection.

The appeal instead proposes that where indirect access to judicial review of the legality of EU legislative acts is not available and fundamental rights are allegedly infringed, ‘individual concern’ should mean serious personal concern or, in the alternative, interference with the essence of the right. It opines that such a reading, while ensuring legal protection, would at the same time prevent locus standi for all.

The defendants responded to this reasoning by simply referring to the opinion of the General Court, as they did in their defence at first instance.

6.3. A Constitutional Parenthesis

As a more general reflection on the relationship between the EU and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR),Footnote 80 fundamental rights may further ground the need to reorientate the restrictive attitude of the CJEU concerning direct access to the General Court. If the applicants were referred to national legal protection they would, if invoking fundamental rights, rather refer to those of the ECHR than to those of the EU Charter. Such recourse before national courts to the ECHR would challenge the role of the CJEU as the main warden and sole arbiter of EU fundamental rights, a role which the ECJ forcefully defended in its Opinion on the accession of the EU to the ECHR.Footnote 81 If the CJEU denies the direct access needed to conduct its own review of the EU targets, two competing systems of fundamental rights norms might emerge: one defined by EU institutions, guided by EU fundamental rights and reviewed by the CJEU; the other defined by individual Member States, guided by ECHR fundamental rights and reviewed by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). This would be precisely the situation of competing and possibly conflicting fundamental rights systems deplored by the Court in its Opinion on EU accession to the ECHR.

6.4. Aspects of an Association Action

CJEU case law is comparatively reluctant to accept standing of associations. It is granted under one of two conditions: (i) where the association's own interests have been distinctively affected, such as concerning its property or when a specifically granted right to be heard was disrespected; (ii) where the association represents the interests of its members who would themselves have standing.Footnote 82 The application submits primarily that the members of the Saminuorra, an association of Sami youths, are all members of families who herd reindeer and are therefore individually concerned. In the alternative, and theoretically more interestingly, the appeal stresses that the association itself is concerned because it represents a collective good of its members, namely, the traditional right of the collectives of reindeer herders to use grazing land in public or private ownership. Such an association action would be different from the more familiar type of trade association which represents the sum of individual member interests rather than, as in the case of indigenous communities, the collective good of its members. The appeal suggests that the ECJ should consider this to be a new type of association action.

7. ACTION FOR NON-CONTRACTUAL LIABILITY

As an alternative to demanding annulment of the three GHG acts pursuant to Article 263 TFEU, the action seeks a judgment obliging the defendants to reduce annual GHG emissions to at most 40 to 50% annually in 2030 compared with 1990 levels. The application is based on the non-contractual liability principle under Article 340(2) TFEU. This type of action is normally undertaken with an eye to the payment of damages but, in the light of the general legal principles of the Member States, the ECJ has extended it to an injunction to take action or to refrain from action.Footnote 83

7.1. Admissibility

In dismissing the application as inadmissible the General Court stated:

An applicant may not, by means of an action for damages, attempt to obtain a result similar to the result of annulling the act, where an action for annulment concerning that act would be inadmissible.Footnote 84

The appeal contends that this is a new concept that deviates from settled case law. The claim was based on the understanding that applications for annulment and non-contractual liability are autonomous. Recourse to Article 340 TFEU was hitherto excluded only if this constituted an abuse of rights circumventing the inadmissibility of an application which concerns the same illegality and has the same financial aim in view.Footnote 85 An example was a case in which the applicant had failed to bring the application for annulment within the terms required by Article 263(6) TFEU and now tried to reach the same result by way of Article 340 TFEU.Footnote 86 Undisputedly, no such defect exists in the present case.

The appeal further contends that the two applications differ as to the nature of the alleged illegality and aim. The illegality is different because non-contractual liability relies on a breach of much broader obligations of higher-ranking law, going back to 1992, the year of adoption of the UNFCCC. The aim is different because the applicants do not seek annulment but the prevention of further damage.Footnote 87 If this entails a statement of illegality of the underlying GHG acts, such statement is incidental and has force only inter partes, not erga omnes.Footnote 88

7.2. Substance

Non-contractual liability has three preconditions: (i) the law infringed must confer rights on the applicant; (ii) the breach of it must be sufficiently serious; and (iii) there must be a direct causal link between the breach and the damage.Footnote 89

Neither the defendant nor the General Court in its order on the admissibility of the application took a position on the substance.

According to the applicants, the legal norms that were violated and continue to be violated are, among others, the fundamental rights to occupation and property. They have existed for a long time as binding standards for EU institutions and as a codified binding catalogue since 2009. This was also the year in which Directive 2009/29/ECFootnote 90 transferred Directive 2003/87/ECFootnote 91 into the post-experimental phase and the burden-sharing mechanism was introduced by Decision 406/2009/EC.Footnote 92 At the same time, the concept of EU allocation of emissions quantities permeated the pertinent legal acts.Footnote 93 Since 2009, at the latest, the EU legislature therefore has had to follow the stricter requirements of higher-ranking law. The applicants further contend that fundamental rights evidently confer rights on the claimants. Insofar as the ‘objective’ protection provisions of the Paris Agreement are concerned, it is sufficient that they in any event also serve the individual interests of the applicants.Footnote 94 This is shown, among other things, by the fact that the Paris Agreement mentions human rights in its tenth recital.

According to settled case law, the encroachment is sufficiently serious if the acting institution has manifestly and substantially exceeded the limits of its discretionary powers, or breached the law if the same did not provide for any discretionary power.Footnote 95 The application submits that, although there is a wide margin of discretion with regard to measures to reduce emissions, the margin of discretion is smaller if the entirety of necessary and feasible measures is envisaged and measured against the temperature limits of the Paris Agreement, and the standard of technical and economic feasibility derived from both the Paris Agreement and fundamental rights.

The applicants claim to have suffered serious damage to their economic activities and property. They concede that the damage is not a physically direct effect of emissions as in, for example, the more familiar scenario of exposure to air-polluting gases. However, they submit that the criterion of immediacy should not refer to the length and complexity of the causal chain between emissions and damage, as long as the causal connection, mediated as it may be, does exist and can be proven. They contend that the EU has a relevant part in that causation, with its share amounting to about 10% of global GHG emissions.

According to current case law on Article 340 TFEU, the cause of the claim for damages must lie in the past. The application argues that this is the case. The EU has been bound by codified fundamental rights since 2009Footnote 96 and has since exercised its competence to regulate GHG emissions. Moreover, if a claim under Article 340(2) TFEU can also be a basis for injunctive relief or action instead of damages, as argued, the causal process must, by implication, also be accepted to continue into the future, which the applicants must then also prove. They claim to have done so by showing that the three GHG acts allow unlawful emissions for the period 2021 to 2030. The application claims that this must be prevented and that correspondingly stronger emissions reductions must be imposed.

8. CONCLUSION

What is actually new and indeed provocative about the Carvalho case is that the application challenges the EU on the ground of insufficient environmental protection. The EU has been an active policymaker in many social fields since its transition 30 years ago from a Zweckverband (limited purpose association) for economic integration to the ‘Europe of the citizens’, as it has been envisaged since the 1980s. This has included environmental policy, in particular.

However, in terms of fundamental rights this policy has hitherto been directed largely by the status negativus of the fundamental freedoms and rights of economic operators who claimed that their rights were encroached upon by ambitious environmental regulation. In contrast, the present complaint aims at a status positivus for the citizens concerned, which makes it possible to allege that not too much, but too little environmental protection is carried out. It argues that if the EU legitimately takes up a policy competence, it must exercise it in accordance with the pertinent fundamental rights. In a broader sense the action can be understood as an expression of the citizens’ confidence in ‘their’ Union.

The major claims and refutations have been reported in this case note. The core issues include whether the CJEU should:

• reinterpret the locus standi requirement of ‘individual concern’ to allow standing in cases of serious interference with human rights, or with their essence;

• accept the other standing requirement, ‘direct concern’, to include regulation that entitles Member States to allow interference with rights of citizens;

• accept standing of associations that represent indigenous communities;

• construe the three challenged GHG acts as sovereign interferences with fundamental rights, or, alternatively, develop and apply obligations of the EU to protect fundamental rights from interference by private actors;

• extend the protective scope of fundamental rights to residents of third countries if they are affected by EU sovereign action;

• acknowledge the limit of the 2°C temperature increase set by the Paris Agreement as binding EU legislation;

• derive from the 2°C limit a global and EU budget for GHG emissions, calculate the EU's share according to the equal per capita criterion, and apply the prevention principle to require – at least – that the way in which the EU budget may be spent must be linearly regressive;

• construe, as a fall-back position, both the fundamental rights and the Paris Agreement as an obligation of the EU to reduce emissions according to the its technical and economical capability; and

• recognize the mutual independence of the actions for annulment and for non-contractual liability, accepting also that the latter enables rights not only to compensation but also to injunctive relief.

How those issues are resolved depends on whether the professional and juridical discourses not only repeat traditional doctrines, but ventilate new ideas in the light of the climate issue. After all, the law, and notably constitutional law, must have a say when communities are in danger of perishing.