1.1 Healthy Diet

Diet is one of the ‘big three’ modifiable health behaviours (together with sleep and physical activity) (Reference Wickham, Amarasekara, Bartonicek and ConnerWickham et al., 2020). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) defines a healthy diet as achieving energy balance, limiting energy intake from total fats, free sugars and salt and increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables, legumes, whole grains and nuts. Regular consumption of a wide variety of foods from key food groups in the right proportions and consuming the right amount of food and drink are conducive to achieving, improving, enhancing and maintaining a healthy body weight (National Health Service (NHS), 2022) and health by reduction of the risk of chronic illness (WHO, 2020). A healthy diet should ensure an adequate intake of macronutrients (i.e. carbohydrates, proteins and lipids) that provide a significant contribution to the caloric intake and micronutrients (i.e. vitamins and minerals) that are considered crucial for the health and vital functions of the human body. In addition, it should provide a diversity of foods of high nutritional quality, be safe to consume (High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE), 2017) and reduce the risk for non-communicable diseases (WHO, 2018, 2020) (see Table 1.1). A balanced, adequate and varied diet is essential for health and well-being (WHO, 2020).

Table 1.1 Key elements of a healthy diet and their characteristics

| Key element | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Quantity |

|

| Diversity |

|

| Quality |

|

| Safety |

|

The content of a diversified, balanced and healthy diet varies depending on individual needs and characteristics (e.g. age, sex, lifestyle and degree of physical activity), locally available foods, dietary customs, cultural context and other considerations (e.g. geographical and environmental aspects). However, the basic principles of a healthy diet remain the same for everyone (WHO, 2020). The World Health Organization’s recommendations for maintaining a healthy diet (WHO, 2018, 2020), based on WHO Nutrition Guidance Expert Advisory Group work to date and prior expert consultations or reports on diet and disease, are presented in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 The World Health Organization’s current recommendations for a healthy diet in adults

| Recommendations | Objective |

|---|---|

| Obtaining the right amounts of essential nutrients, that is, protein, vitamins and minerals, and balancing energy intake with expenditure. |

| |

| Reducing the risk of non-communicable diseases and helping to ensure an adequate daily intake of vitamins, minerals, dietary fibre, plant protein and antioxidants. |

| Preventing unhealthy weight gain. |

| |

| |

| Preventing high blood pressure and protecting against heart disease and stroke. |

|

The Eatwell Guide, produced by the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (Public Health England, 2016a, 2016b), represents food-based dietary guidelines by giving a visual representation of the different types and the appropriate proportions of foods and drinks required to achieve a balanced diet and improve dietary health. The guidelines are directed at the general population from the age of two years. The Eatwell Guide is based on five food groups, namely fruit and vegetables (weight of food: 40%), potatoes, bread, rice, pasta and other starchy carbohydrates (38%), beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins (12%), dairy and alternatives (8%) and oils and spreads (1%), and illustrates the proportion that each food group should contribute to a healthy balanced diet (Public Health England, 2016a) (see Figure 1.1). The proportions shown are representative of food consumption over a day or even a week, not necessarily at each mealtime.

Individuals decide on multiple food choices each day. Many factors, including genes, influence these choices, as do learned experiences with food and the broader physical, social and cultural environment (Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo, Drewnowski, de Pee and VandevijvereMonterrosa et al., 2020). Awareness of the importance of balanced nutrition is an essential factor that may influence dietary choices (Reference Alkerwi, Sauvageot, Malan, Shivappa and HébertAlkerwi et al., 2015). Both individual determinants of personal food choices, including one’s physiological state (e.g. innate preferences for sweet and aversion for bitter tastes), food preference, nutritional knowledge, perception of healthy eating (public understanding of and opinion – views, attitudes and beliefs – about healthy eating), psychological factors (e.g. emotions, mood, well-being), and collective determinants of eating behaviour, including interpersonal environment (e.g. family, peers), physical environment, economic environment, social environment and healthy public policy, determine healthy eating (Reference RaineRaine, 2005) (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Guiding principles for sustainable healthy diets according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and WHO.

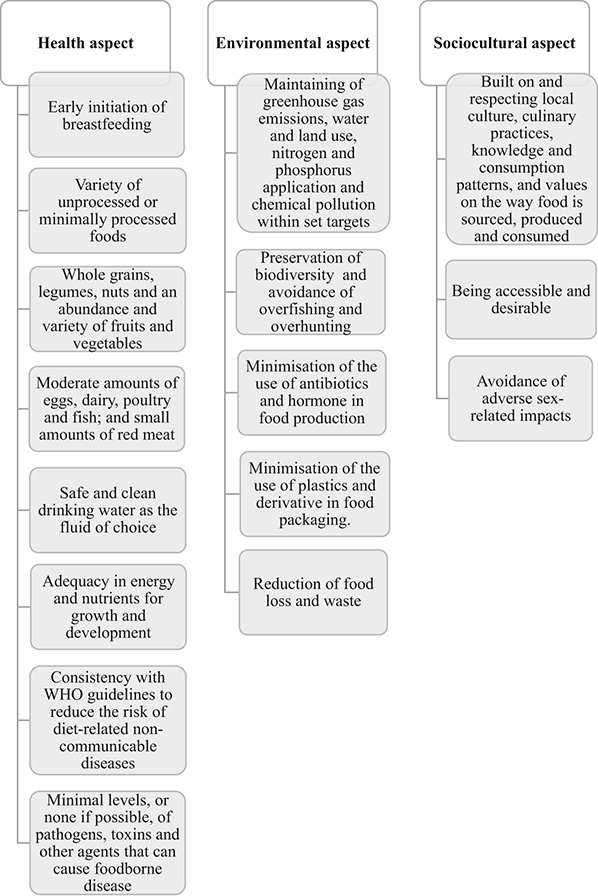

1.2 Sustainable Healthy Diets

Sustainable healthy diets are dietary patterns that promote all dimensions of individuals’ health and (physical, mental and social) well-being, have low environmental pressure and impact, are accessible, affordable, nutritionally adequate, safe and equitable, as well as being culturally acceptable, while optimising natural and human resources (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 2012; FAO & WHO, 2019). The definition produced by the FAO and the WHO placed health at the forefront of consideration while still underscoring the need to consider other aspects, whereas in the previous definition (Reference Burlingame and DerniniBurlingame & Dernini, 2012), economic and environmental goals of diets were often given pre-eminence (Reference Harrison, Palma, Buendia, Bueno-Tarodo, Quell and HachemHarrison et al., 2022). Health, environmental and socio-cultural aspects are dimensions of sustainable healthy diets that must be considered together to achieve sustainable healthy diets (FAO & WHO, 2019) (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Healthy reference diet for an intake of 2,500 kcal/day.

* Whole grains; ▪ Tubers or starchy vegetables; ▫ Vegetables; ◦ Daily foods; ~ Protein sources; ˆ Legumes; ˖ Added fats; ˹ Added sugars.

As the FAO and the WHO (FAO & WHO, 2019) clearly state, one of the actions required to make sustainable healthy diets available, accessible, affor-dable, safe and desirable is the development of national food-based dietary guidelines (that represent healthy diets in a culturally appropriate dietary pattern for the country in which they are designed) according to the principles presented in Figure 1.3 (FAO & WHO, 2019). It is also important to note that just because a diet is sustainable, it is not necessarily healthy (Reference Hemler and HuHemler & Hu, 2019). Vegan and vegetarian diets typically have less environmental impact than diets containing meat (Reference Melina, Craig and LevinMelina et al., 2016), but a vegan eating many refined carbohydrates and added sugars could be at a greater risk for weight gain and chronic diseases than an omnivore consuming meat and a variety of healthy plant-based foods. Although it is possible to achieve a healthy and sustainable diet without becoming vegan or vegetarian, these dietary patterns, if comprised of high-quality plant foods and are appropriately planned to avoid deficiencies, can be nutritionally adequate for all stages of the life cycle (inclu-ding infancy, pregnancy and older adulthood) and can reduce chronic disease risk (Reference Melina, Craig and LevinMelina et al., 2016).

1.3 Dietary Patterns

Diet evolves over time, being influenced by a variety of factors, including food-internal (e.g. sensory and perceptual features), individual (psycholo-gical, physical, neurological, cognitive; e.g. individual preferences and beliefs, knowledge and skills), social (e.g. income), economic (e.g. food prices) and environmental factors (e.g. time) that interact in a complex manner to shape individual dietary patterns (Reference Chen and AntonelliChen & Antonelli, 2020). Dietary patterns can be defined as the quantities, proportions, variety or combination of different foods, drinks and nutrients in diets in relation to the five food groups of the Eatwell Guide, United Kingdom and the MyPlate, United States of America (fruit and vegetables, carbohydrates/grains, protein, fats and sugar, dairy products) (Reference Timlin, McCormack, Kerr, Keaver and SimpsonTimlin et al., 2020), and the frequency with which they are habitually consumed (Reference Bouchey, Ard, Bazzano, Heymsfield, Mayer-Davis, Sabaté, Snetselaar, Van Horn, Schneeman, English, Bates, Callahan, Venkatramanan, Butera, Terry and ObbagyBouchey et al., 2020).

The number of diets available in the market is excessive. Therefore, it is worth knowing how to make an informed food choice. A recent report, ‘Best Diets of 2023’ by US News and World Report (2023), released 24 diets ranked by medical experts, nutritionists, dietitians, physicians and epidemiologists. The Mediterranean diet (number 1 for the sixth year in a row), the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and the flexitarian diet remain the ‘Best Overall Diets’ and the ‘Best Diets for Healthy Eating’ of 2023 (4.6 out of 5 points, 4.5 out of 5 points and 4.3 out of 5 points, respectively). The Mediterranean diet is a territorial plant-based diet with little to moderate amounts of animal-sourced foods. It is characterised by an abundance of vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, seeds and fish, with liberal use of olive oil, a moderate amount of dairy foods and a low amount of red meat (Reference Hachem, Capone, Yannakoulia, Dernini, Hwalla and KalaitzidisHachem et al., 2016). Strong scientific evidence showing the association of the Mediterranean diet with a significant reduction in total mortality, mortality from cardiovascular disease and cancer, and a lowered cancer risk has led to this dietary pattern being promoted in regions and dietary guidelines of countries far from its geographic origins (Reference Hachem, Capone, Yannakoulia, Dernini, Hwalla and KalaitzidisHachem et al., 2016). It is worth noting that 10 years ago the Mediterranean diet was included on the Intangible Cultural Heritage List of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) by the Intergovernmental Committee of the Convention concerning the Intangible Heritage of Humanity (United Nations Educational Social and Cultural Organization, 2013, as cited in Reference Subhan and ChanSubhan & Chan, 2016). Similar to the Mediterranean diet, the DASH diet incorporates fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fat-free/low-fat dairy, nuts and legumes, lean meat choices, limiting total and saturated fat, cholesterol, red and processed meats, sugar-sweetened be-verages, sweets and added sugars and consuming reduced amounts of sodium (Reference Chiavaroli, Viguiliouk, Nishi, Blanco Mejia, Rahelić, Kahleová, Salas-Salvadó, Kendall and SievenpiperChiavaroli et al., 2019). A flexitarian diet (also known as a semi-vegetarian diet) primarily (but not strictly) includes a vegetarian diet with the occasional inclusion of meat or fish (Reference DerbyshireDerbyshire, 2017).

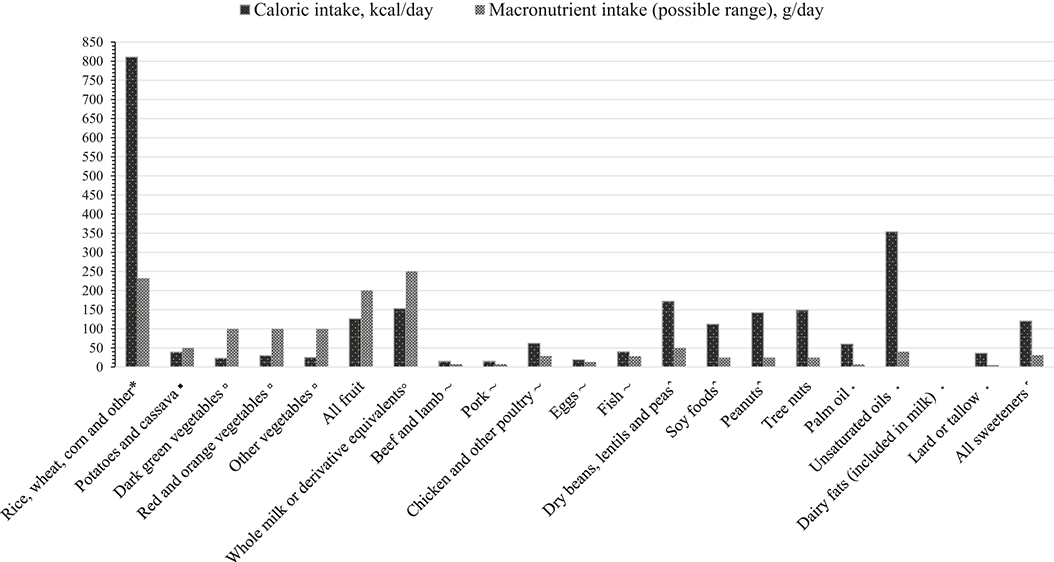

The EAT–Lancet reference diet (Reference Willett, Rockström, Loken, Springmann, Lang, Vermeulen, Garnett, Tilman, DeClerck, Wood, Jonell, Clark, Gordon, Fanzo, Hawkes, Zurayk, Rivera, De Vries, Majele Sibanda, Afshin and MurrayWillett et al., 2019) is the first global benchmark diet capable of sustaining health and protecting the planet at the same time, minimising chronic disease risks and maximising human well-being. It is rich in fruits and vegetables, with protein and fats sourced mainly from plant-based foods, unsaturated fish oils and carbohydrates from whole grains (see Figure 1.3). The healthy dietary pattern consists of ranges of intakes for each food group. For an individual, an optimal energy intake to maintain a healthy weight depends on body size and level of physical activity. The global average per capita energy intake has been estimated as 2,370 kcal per day (Reference Hiç, Pradhan, Rybski and KroppHiç et al., 2016), ranging from 2,000 to 2,200 kcal per day for women to 2,800 kcal per day for men (Reference Freedman, Commins, Moler, Arab, Baer, Kipnis, Midthune, Moshfegh, Neuhouser, Prentice, Schatzkin, Spiegelman, Subar, Tinker and WillettFreedman et al., 2014). Therefore, 2,500 kcal per day has been used as a basis for different isocaloric dietary scenarios (i.e. having similar caloric values) (see Figure 1.4).

The idea of classifying foods as ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’Footnote 1 based on their nutrient composition (Reference Lobstein and DaviesLobstein & Davies, 2008) is still discussed, with a ge-neral lack of consensus. Some argue that no foods are inherently ‘healthy’ or ‘unhealthy’ and that all foods can be part of a healthy diet if consumed in moderation. More and more, there is a push to move from nutrient-specific or food-specific approaches to more holistic ones examining overall dietary patterns (Reference Mozaffarian and LudwigMozaffarian & Ludwig, 2010). According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (Reference Freeland-Graves and NitzkeFreeland-Graves et al., 2013), the total diet or overall pattern of food eaten is more important to a healthy diet than focusing on single foods or individual nutrients and labelling specific foods as ‘good food’ or ‘bad food’ that may foster unhealthy eating behaviours. Messages emphasising the total diet approach promote positive lifestyle changes (Reference Freeland-Graves and NitzkeFreeland-Graves et al., 2013). In addition, focus on variety, moderation and proportionality in a healthy lifestyle are the key concepts for balancing food and beverage intake (Reference Freeland-Graves and NitzkeFreeland-Graves et al., 2013). When making dietary recommendations, it is essential to emphasise overall dietary patterns rather than specific foods and nutrients to account for the synergistic effects of the total diet on health (Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, 2015).