1. INTRODUCTION

Abundant evidence of different types suggests that New Spain experienced a change in consumption patterns following the arrival of Asian goods to its Pacific shores from 1565 onwards. Those new goods (silk in varied forms, porcelain, furniture, ivory religious sculptures, cotton textiles, garment, screen folds, lacquer objects, fans, spices and others) significantly expanded the possibilities of consumption by the Viceroyalty's population. The Manila Galleons' cargo contained many of the very same merchandise that would fascinate European consumers all along the 17th and 18th centuries. Those merchandises came mainly from China—the Galleon was known as the Nao de China but also from the Philippines, Japan, India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Southeast Asia.

Other goods that also characterise the consumer revolution, such as the «American triad», were domestically produced and widely consumed (see Von Humboldt Reference Von Humboldt1822:1991, pp. 288 and 292-298; Céspedes Reference Céspedes1992; Miño Reference Miño2013; Dobado-González Reference Dobado-González2015). Cocoa and tobacco were already known in Pre-Hispanic México although their consumption was «democratised» and increased after 1521. Sugar was introduced soon after the conquest. Thus, by 1600, consumption in New Spain presented a significant degree of «Americanisation» and «Orientalisation». These two features may be associated with the consumer revolution. As «Americanisation» is almost tautological in our case, this article focuses on the early «Orientalisation» of consumption patterns in pre-independent Mexico.

Most of the literature on the consumer revolution has focused on Europe and therefore has missed that similar developments have taken place elsewhere. North-Western European countries continue dominating the field while quantitative evidence is not always explicitly provided (Pérez-García Reference Pérez-García2017). Consequently, our work on Early Modern Mexico is unprecedented in some important respects. On the one hand, contrary to previous research, we approach the numerous instances revealing the presence of Asian goods in New Spain from the broader perspective of the consumer revolution. Thus, the existing pieces of evidence are integrated into an overall picture of our case study. On the other hand, we use the quantitative evidence offered by the avalúos of the Manila Galleons cargo.Footnote 1 That is why we can make a numerical exercise to check whether or not Asian goods within the low or, even sometimes, middle ranges of price could be accessed by the commoners of Mexico City. This methodology is a novelty.

The concept of consumer revolution was originally introduced as «a consumer boom in England in the eighteenth century» that «was the necessary analogue to the industrial revolution» (McKendrick et al. Reference Mckendrick, Brewer and Plumb1982, p. 9). McKendrick et al. proposition about this complex and influential period of England's history gained popularity—and received criticism—in subsequent years. In this regard, Berg (Reference Berg2004, p. 86) highlights the role played by imports of luxury goods from India and China in the transformation of Europe's economy. McCants (Reference McCants2008) shows that Dutch «poor consumers» might also be «global consumers», while Ogilvie (Reference Ogilvie2010) focused on the opposition of elites to new work and consumption practices in Württemberg. On the other hand, the consumer revolution has been considered a «statistical artefact» by Clark (Reference Clark2010). However, Rönnbäck (Reference Rönnbäck2010) finds a consumer revolution in the Baltic during the Early Modern Era. More recently, Sear and Sneath (Reference Sear and Sneath2020) have joined the ranks of the defenders of the existence of a consumer revolution in England.

Our approach to the study of the consumer revolution in New Spain shares with De Vries (Reference De Vries2008, p. 122) that we do not look either for: «an exploding volume of purchased good that jump-started the growth of production in the ‘leading sectors’ of the Industrial Revolution». Nothing comparable to any form of industrial revolution took place in pre-independent Mexico. Notwithstanding, changes in the consumption of goods' supply and demand occurred. Innovations, although limited, in the production of consumption goods also took place within the domestic artisanal sector. Some of them were influenced by East Asian crafts not long after the arrival of the first Manila Galleons—see Figures 1A and 1B.

FIGURE 1 (A) Unknown author. Barrel, 1650-1700, Tin-glazed earthenware with cobalt overglaze, Puebla de los Ángeles.

Source: Collection of Decorative Arts, Latin America & the Philippines, Hispanic Society, New York, USA. Accession number E990.

FIGURE 1 (B) Unknown author. Biombo de los Virreyes en Ciudad de México, 1676-1700. Oil on canvas..

Source: Museo de América, Madrid, Spain. Inventory N° 00207.

New Spain is not an outlier concerning the relationship, or its absence, between consumer revolution and modern economic growth. That changes in consumption patterns did not trigger industrialisation is rather the rule than the exception, as several examples, the Netherlands included, show (e.g. among others, Denmark, France, Germany and Sweden).

Thus, we use the term consumer revolution in a straightforward instrumental sense: a significant increase in the consumption of «exotic» goods that may be observed over the Early Modern Era in parts of Europe and the Americas. We contend that New Spain was only second to Portugal in experiencing those changes.

The deep influence of Asia on the Iberian empires was already noticed by art historians: «Colonial Latin America was more directly and profoundly affected by Asian culture than Europe ever was» (Bailey Reference Bailey and Rishel2006, p. 57).

From an intercontinental perspective, the Manilla Galleons that made possible the consumption of Asian goods in New Spain represent one of the first constitutive elements of globalisation in the Early Modern Era. They played an important role in the surging of the historical landmark constituted by «the first planetary economy» (Giráldez Reference Giráldez2015, p. 191). As stated by Findlay and O'Rourke (Reference Findlay and O'rourke2007, pp. 173-175) a «unique episode in the history of global commerce» took place: the Manila Galleons trade route lasted two and a half-century and consisted of the exchange of Hispanic-American silver for Asian goods. Therefore, Flynn and Giráldez (Reference Flynn and Giráldez2004, p. 82) «propose that globalization began when the Old World became directly connected with the Americas in 1571 via Manila». In that year the Manila Galleons started to regularly sail across the Pacific with their cargo of silver and Asian goods.Footnote 2

Therefore, the route between Manila and Acapulco was far from being of minor importance to the global economy that emerged from the worldwide circulation of Hispanic-American silver. According to Seijas (Reference Seijas2016, p. 56), the Galleon economic effects on New Spain's economy were significant: «[it] fostered manufacturing, promoted regional trade networks, and enabled Indians and people of mixed origins to participate in a monetized economy along with Spanish colonists». Despite the interest in this rather unexplored field of research, we will not go deeper into it.

As claimed by Gruzinski (Reference Gruzinski2010, pp. 124-153), by the early 17th century Mexico City had taken advantage of its location between Asia and Europe. Bernardo de Balbuena (1562-1627), placed it in his Grandeza mexicana (1604) at the very centre of the commercial networks linking all densely inhabited parts of the world; in turn, the English Dominican Thomas Cage, who visited the capital of the viceroyalty in 1625, considered it as one of the richest towns of the world. With nearly 60 per cent of the world's total in the 18th century, New Spain became the main producer of silver while Acapulco, its main Pacific port, was the only authorised destination for the Galleons. This coastal town was connected to Mexico City through the China Road (slightly less than 400 km).

New Spain exceeded in wealth and population the rest of the American territories of the Hispanic Monarchy. Circa 1800, the population of Madrid had the same order of magnitude as Mexico City and a similar living standard. Interestingly enough, the diffusion of «exotic» goods was comparatively limited and late in the capital of the Spanish Empire. For 1580-1630, Gash Tomás (Reference Gasch-Tomás2014, p. 202) states that «Asian goods circulated more widely in American than in Castilian territories». Fernández de Pinedo (Reference Fernández-De-Pinedo, Garcia and De Sousa2018) finds that, by mid-18th-century Madrid, the consumption of Asian goods (mainly porcelain) was limited to the elite and the upper classes. Furthermore, Krahe (Reference Krahe, Grasskamp and Juneja2018, p. 229) states that «Spanish did not develop a pronounced taste for East Asian porcelain. Thus, Chinese porcelain appears only in a limited number of the inventories of household goods of the Spanish elite in main cities like Madrid, Seville, or Valladolid». For Díaz (Reference Díaz2010, p. 48): «the taste for porcelain became generalized much before in New Spain than in the metropolis».

To the best of our knowledge, it is not until the 18th century that a quantitative approach to the consumption of Asian goods in New Spain may be conducted safely. Therefore, we focus on that century. On the one hand, original documents abound in the Archivo General de Indias de Sevilla. On the other hand, even if mainstream literature has not paid enough attention to Hispanic America, increasing research is starting to widen our knowledge of the economic history of 18th-century Mexico. In the third section, we show some demand and supply factors that explain why the commoners could participate in the consumer revolution. A numerical exercise confirms that a non-negligible set of Asian goods were accessible to the commoners. By implication, this article points to the need of revising some widespread perceptions of living conditions in New Spain.

2. EVIDENCE ON THE EARLY CONSUMER REVOLUTION IN NEW SPAIN

The taste for Asian goods in the Spanish Empire has already attracted some interesting research. A body of, especially, qualitative and, infrequently, quantitative research has somewhat nuanced the Eurocentric scholarly perspective that Asian trade was only oriented to an elite consumption in the West. Abundant evidence reveals that Chinese porcelain and textiles, as well as screens and lacquerware circulated across the Hispanic world before the first Asian goods were accessible to the North-Western European public.

According to Kuwayama (Reference Kuwayama1997, p. 11), in 1573, two Manila galleons arrived in Acapulco with a cargo that included 712 pieces of silk and 22,000 porcelains. By then «a market for this product [porcelain] was firmly established» in New Spain (Slack Reference Slack, Lai and Chee-Beng2010, p. 42). In turn, Curiel (Reference Curiel Méndez2012) has documented the presence of Chinese screen folds in Mexico City residences since the late 16th century.

Gasch-Tomás (Reference Gasch-Tomás2014, p. 210) has made a significant contribution by estimating, for 1580-1630, an econometric model in which the value of Asian goods in probate inventories of elites from Mexico City and Seville significantly responded, especially in the latter town, to non-commercial networks (e.g. seamen aboard the «Carrera de Indias» and relatives of the recipients residing in the Americas and the Philippines). This author also argues that contrary to «18th-century European societies», in the Spanish Empire «‹middle-elites› such as shopkeepers, craftsmen and above all the clerics, instead of nobles and wholesale merchants» turned out to be active agents in the diffusion of Asian silk and furniture.

In this regard, Bonialian (Reference Bonialian2017) analyses the effects on the 16th and 17th-century New Spain textile sector resulting from the imports and consumption of Chinese raw material known as «madeja silk» and concludes that Asian trade satisfied mass consumption demand. For Baena (Reference Baena2012), in the 17th century, New Spain screens were already being produced and exported to other American territories, as well as to Europe. As Lemire (Reference Lemire2018, p. 71) pointed out, «the Manila-Acapulco connection produced a distinctive material ecosystem in the Americas, with New Spain and the Viceroyalty of Peru exceptionally supplied, and the influence of Asian materials apparent across social and racial hierarchies». Earle (Reference Earle, Berg and Eger2003, p. 220) claims that in Thomas Gage's testimony after having visited New Spain in the 1620s, the «poor, mixed-race population is also described as dressing with extraordinary elegance and expense».

No doubt, the influence exerted by the opening of the Manila Galleon trade unleashed some changes in the daily and material life of the inhabitants of New Spain as scholars have shown—without not paying too much attention to its quantitative aspects.Footnote 3 A century later, in the 18th century, the influence of this trans-Pacific trade was the primary force behind the emergence of a new hybrid pattern of consumption among all social classes, not only the wealthiest, in New Spain.

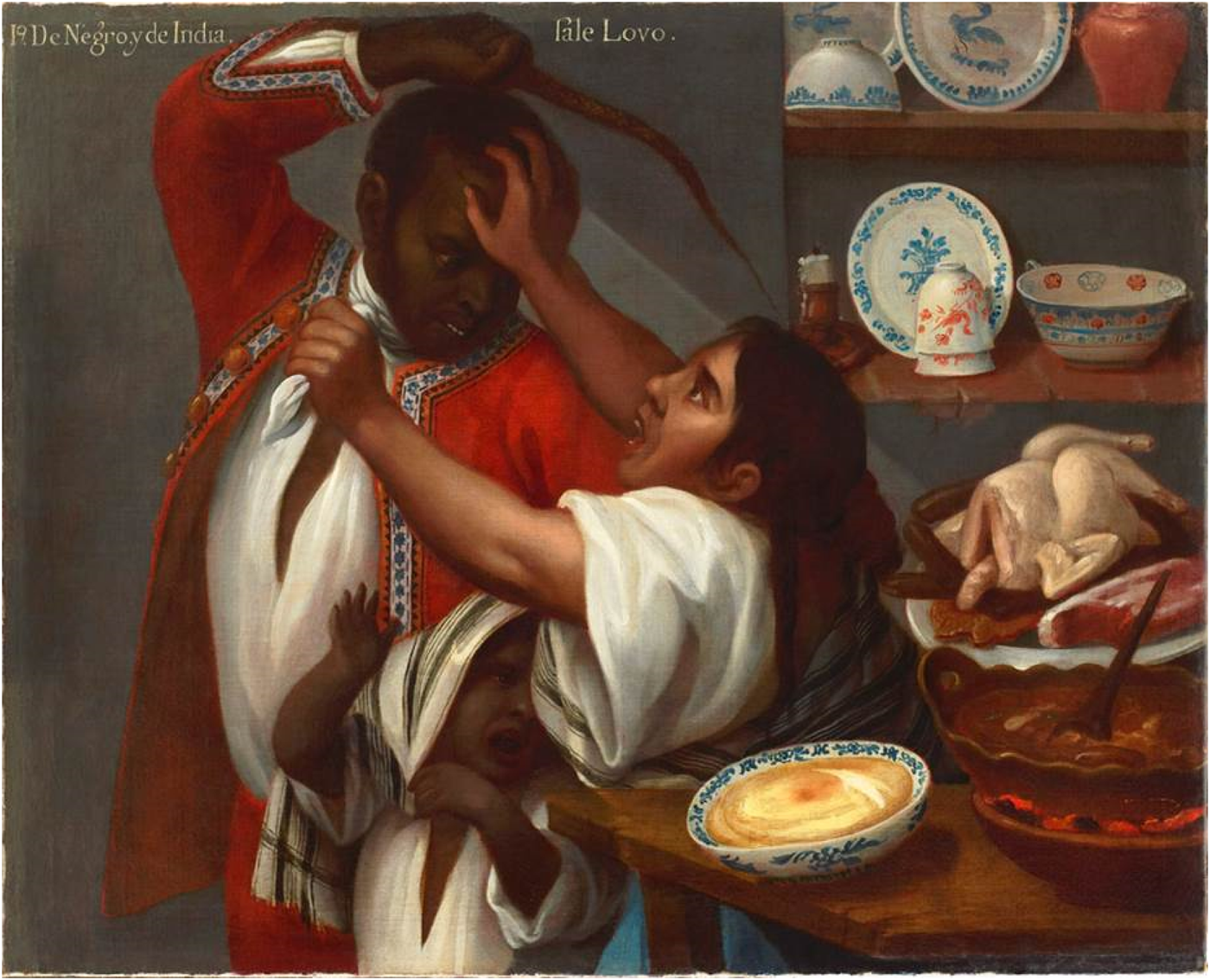

These claims also find some support in the «pinturas de castas», a genre of painting that became popular in the 18th century, depicting members of different ethnic groups along with objects and activities of their everyday lives (see Figure 2). Therefore Casta paintings frequently represent the poorest strata of society. These paintings were an attempt to highlight how large the diversity of ethnic groups and hybridised styles are in everyday life. What is especially interesting in some of the illustrations (see Figure 2) is that we can see a series of cups and dishes that are either of Chinese origin or their local majolica imitations. Moreover, some clothes of presumably unprivileged men are elegant and seem to somehow reflect certain Asian influence.

FIGURE 2 “De negro y de india, sale lovo” (From Black and Indian “wolf” comes out).

Source: José de Alcíbar, De negro y de india sale lovo, Museo Nacional de Historia (INAH), ca. 1765.

We cannot assure whether these representations are precise and accurate depictions of everyday life in those times, but what we can certainly assert is that such items were part of the material culture of the country—and seemingly to a considerable degree, since a significant shares of the Casta paintings contain Asian goods (textiles, pottery, furniture and decorative objects). Thus, iconography reinforces what our estimates show: that the commoners could access to some of the merchandise transported by the Manila Galleon—see next section.

This is also consistent with de Monségur's (Reference De Monségur and Duviols2002) report of 1707 when of the 4 million pesos traded between Acapulco and Manila, 3 million corresponded to all kinds of clothes and fabrics. We do know that this year was certainly exceptional and that de Monségur's figures largely exceed the official ones. However, this points out a very interesting issue: since the late-16th century and until the first half of the 18th, New Spain could draw upon the Asian markets as a reliable source of imports when war among European powers made commerce in the Atlantic difficult or nearly impossible (Fernandez de Pinedo and Thépaut-Cabasset Reference Fernandez De Pinedo, Thépaut-Cabasset, Dobado-González and García-Hiernaux2021).

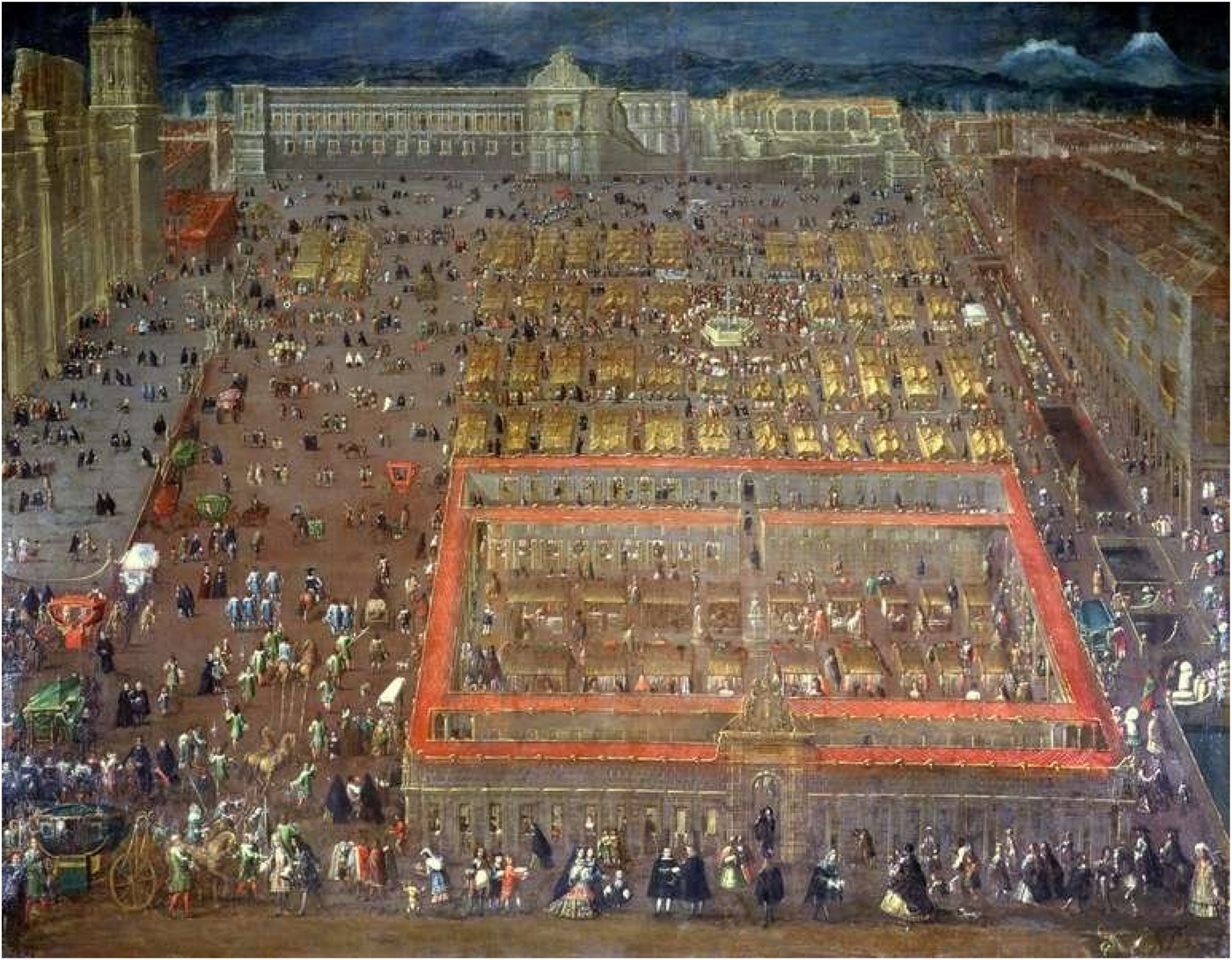

Thus, as opposed to Madrid, traders and consumers of Asian goods counted with a privileged space in Mexico City: the Parián market. It was named after Manila's Chinatown, the first one of the modern age (Slack Reference Slack, Lai and Chee-Beng2010, p. 8).Footnote 4 Since 1688, both physically and symbolically it played a leading role in the gigantic main square of Mexico City. Traders and consumers of Asian goods were given this privileged place with eighty-two-story stores and several dozens of smaller movable «boxes» that displayed a variety of Asian goods transported from Manila via Acapulco (Olvera Ramos Reference Olvera Ramos2013, pp. 101-126). The painting by the local artist Cristóbal de Villalpando (1649-1714) reflects the importance acquired by the Parián, the building at the bottom right of it—see Figure 3.

FIGURE 3 View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico City

Source: Cristóbal de Villalpando, ca. 1695. Vista de la Plaza Mayor de la Ciudad de México https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archivo:Vista_de_la_Plaza_Mayor_de_la_Ciudad_de_M%C3%A9xico_-_Cristobal_de_Villalpando.jpg (Visited on 8 August 2019).

The Parián «satisfied the exotic demands of elites and commoners alike» (Slack Reference Slack2009, p.42). Besides serving the domestic market, New Spain acted, frequently skipping the regulations, as a redistribution centre of Asian goods for the rest of Hispanic America (Bonialian Reference Bonialian2014).

An early consumer revolution favoured a consumption pattern based on appearances and not just on needs. In other words, we would be facing, at least in New Spain, an early conspicuous consumption as the purchase of Asian goods was not limited to Mexico City or the vicinity of Acapulco. Machuca (Reference Machuca2012, p. 99) has detected the presence of a wide variety of Asian goods (textiles, ceramics, furniture, folding screens and others), mainly from China, among the inventories of the upper class in the small town of Colima throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. It remains difficult, due to the lack of sources or their inaccessibility, to ascertain whether other segments of the population consumed Asian goods as well. However, the author mentions the case of a coalman in the minor and remote mining centre of Sierra de Pinos (San Luis Potosí) that possessed lacquers from China and oriental textiles as an instance of the access to Asian goods at the beginning of the 17th century by consumers outside the «governing elite». Nevertheless, her text also informs of the high demand for Asian secondhand clothes, even if «warned and worn-out» since the late 16th century.Footnote 5 This consumer attitude is consistent with Romero de Terreros' idea that the servants used the clothes discarded by their masters and these were later worn by beggars.Footnote 6

Based on archaeological and documentary evidence, Pierce (Reference Pierce2016) claims that Asian goods (mainly porcelain and silk) reached as far as New Mexico—«eighteen hundred difficult miles» from Mexico City—and San José del Parral (Chihuahua) from the very beginning of their foundation in the late 16th or early 17th centuries. According to her, in the 18th century, Asian goods were more accessible to «people of modest means».

Ibarra (Reference Ibarra2016, p. 156) finds also high levels of consumption of Asian goods across the whole Intendancy of Guadalajara in the 18th century. The demand was exerted by the rich minority in the form of luxury merchandise (porcelain, folding screens and so on) as well as by the «indigenous and peasant population that included in their clothing the silks and stamped cottons coming from the East».Footnote 7

We have also analysed another primary quantitative source. Before the departure of the Galleon from Manila, the authorities issued an appraisal (avalúo) certificating the price of the goods that the cargo comprised. Thus, it is possible to know the prices of a long list of Asian goods in Manila. However, the avalúo might intentionally undervalue those prices—or some of them—to illegally surpass the official limits established for the value of the cargo (Díaz Reference Díaz1984). Those limits changed over time: from Manila to Acapulco, an export of 250,000 pesos was allowed from 1593 to 1702 which was increased to 300,000 pesos (1702-1734), then to 500,000 (1734-1776) and finally to 750,000 (from 1776 on) (Yuste Reference Yuste López1984, p. 16). Smuggling aside, the stagnation of the tradable amount during the Habsburg dynasty contrasts with the several increases adopted after the access of the Bourbons to the Spanish throne in 1700.

Evidence abounds proving that those legal limits were permanently exceeded by the merchants involved in this trade. To start with, Bonialian (Reference Bonialian2017, p. 9) claims that the very existence of the Galleons was based on contraband. Gíráldez (Reference Giráldez2015, p. 156) shares a similar opinion.Footnote 8 Despite the persistence of a set of formally strict regulations, the authorities never knew the real value of the cargo (Yuste Reference Yuste López1984, pp. 46 and 48).

Arteaga et al. (Reference Arteaga, Desierto and Koyama2020), on top of claiming that «corruption was widespread», have estimated the value of silks, spices, and Chinese and Japanese pieces of porcelain (nearly 200,000) transported in 1694 by the sunk galleon San José was worth 7.7 million pesos or «2% of the GDP of the entire Spanish empire».Footnote 9 The accuracy of the estimate is arguable but gives an idea of the importance of contraband in this trade route.

Therefore, the legal limits to the imports of Asian goods and their consumption in New Spain should be considered as a minimum. A report from 1748 estimates the fob value of a significant—although incomplete—part of the Asian goods carried across the Pacific by the Galeón in almost 1.3 million pesos.Footnote 10 Moreover, the figures offered by Yuste (Reference Yuste López1984) show that even the value of the trade controlled by the authorities was frequently above the legal limits.

The uncertainty about the true value of the Galleons' cargo and the volume of re-exports makes it impossible to accurately estimate the per capita consumption of Asian goods in New Spain. Therefore, we have chosen an indirect numerical exercise—see next section—that supports our hypothesis regarding the access of the commoners to them.

From Acapulco to Manila, the silver returned in exchange for Asian goods might double the legal values for imports as it included a supposed profit of 100 per cent (Giráldez Reference Giráldez2015, p. 156). Estimates of the Hispanic-American silver that crossed the Pacific widely differ from each other. De Vries (Reference De Vries, Flynn, Giráldez and Von Glahn2003, pp. 80-81) proposes a yearly average between 17 and 51.2 tons for 1600-1650. Interestingly, even the lower bound is higher than the flow of silver from Europe to Asia via the Cape route. However, in 1725-1750, the unchanged higher bound of the Hispanic-American silver remittances to Asia was about one-third of those from Europe. The increase in the operations of the European chartered companies and the creation of new ones (e.g. the Swedish East India Company) explains the relative decline of the Pacific route.

Although all authors are very sceptical about the fulfilment of the Manilla Galleon regulations, none of them questions the composition of the cargo depicted in the above-mentioned avalúos. This rich source allows having a detailed knowledge of the multiple items included in the Galleons’ cargo—e.g. 211 items in 1711 and 510 in 1789.Footnote 11 Therefore, we used them to determine what types of Asian goods were consumed in New Spain. According to 18th-century avalúos, textiles accounted for around three-quarters of the items enlisted in the avalúos. Spices and porcelain also were a significant part of the cargo, but they did not play the dominant role of textiles (Grasskamp and Juneja Reference Grasskamp and Juneja2018).

Again, this is consistent with de Monségur's (Reference De Monségur and Duviols2002) observations and Canepa's (Reference Canepa2016, p. 409) claim for the 16th century that «silks were available for purchase to a multi-ethnic clientele from almost all colonial classes, to be used in both secular and religious context». This flow of Asian textiles, mainly silks, was in fact competing with European textiles manufacturers and creating a particular consumption ecosystem (Fernandez de Pinedo and Thépaut-Cabasset Reference Fernandez De Pinedo, Thépaut-Cabasset, Dobado-González and García-Hiernaux2021, p. 294).

We can thus conclude that New Spain was an active consumer of Asian goods—not to mention the «American triad»—from the last third of the 16th century, which makes this Viceroyalty one of the earliest participants in the consumer revolution and second, that the participation in that revolution was both socially and geographically widespread.

3. WHY COMMONERS COULD PARTICIPATE IN THE 18TH-CENTURY CONSUMER REVOLUTION IN MEXICO CITY

In this section, we show a series of factors that permit us to propose for the first time an answer to the question of why a consumer revolution in New Spain was possible. However, it is only for the 18th century that we can argue upon the basis of numerical exercises that are so far infrequent—or non-existent—even in countries with a much longer tradition of studies on the trade between Europe and Asia. Some results might be unexpected by mainstream scholarship.

We start by distinguishing between demand and supply factors. The section is closed by presenting some estimates of the purchasing capacity of the commoners of Mexico City in terms of Asian goods.

Among the demand factors, we highlight three that have probably not received enough attention in the historiography: pre-industrial economic growth; relatively high real wages; and lower inequality than usually assumed for Hispanic America.

Dobado and Marrero (Reference Dobado and Marreno2001) proposed the concept of «mining-led growth» to describe the fundamentals of the economic expansion experienced by New Spain from the beginning of the 18th century.Footnote 12 «Mining-led growth» is a variety of Smithian growth fuelled by: (a) the abundance of silver deposits scattered across a significant part of the Viceroyalty; (b) the backward linkages of mining with other economic activities (transportation, agriculture and manufacturing). It was also based on the government's enlightened self-interest since silver production was the main determinant of total tax collection and fiscal surplus transferred to Spain. Thus, the Bourbon reformist governments provided tax reductions, subsidies and institutional support in favour of silver producers (Dobado González Reference Dobado González2002).

The validity of the concept of «mining-led-growth» is confirmed by qualified contemporary observers, such as Alexander von Humbdolt (Reference Von Humboldt1822) and Fausto Elhúyar (1825). It is also supported by the cointegration analysis (1714-1805) performed by Dobado and Marrero with a number of decisive variables both for New Spain's economy (silver production with its forward and backward linkages with other sectors) and for the Crown finances (royal treasury income and fiscal surplus remittances to Spain and other territories) (Dobado and Marrero Reference Dobado and Marrero2011).Footnote 13 Simplifying, the basic political and economic relationship in New Spain was:

ΔMercury consumption by the mining sector = > ΔAbsolute and relative silver production by amalgamation = > ΔOrdinary fiscal revenue from mining and other economic sectors = > ΔRemittances of fiscal surplus to the rest of the Empire

Arroyo Abad and Van Zanden (Reference Arroyo Abad and Van Zanden2016, pp. 1182-1215) also offered a relatively optimistic view of the economic growth of New Spain and Peru during Early Modern times. Despite the assumed «extractiveness» of its institutions, the GDP per capita in New Spain, between the mid-16th century and 1700 grew—in 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars—from less than 400 to more than 900 (Arroyo and Van Zanden Reference Arroyo Abad and Van Zanden2016, p. 1192). In 1575-1675 and 1725-1775, GDP per capita growth was higher in Mexico City than in London and Madrid (Arroyo and Van Zanden Reference Arroyo Abad and Van Zanden2016, p. 1200). The drivers of this economic dynamism were high real wages, intense urbanisation and silver mining growth.

As to real wages or welfare ratios, they were in Mexico City clearly above those in Madrid from 1650-1699 to 1750-1799 (Arroyo and Van Zanden Reference Arroyo Abad and Van Zanden2016, p. 1201). Welfare ratios are estimated with nominal wages of unskilled workers and «bare bones» baskets of consumption.Footnote 14 This result is consistent with Dobado and García Montero (Reference Dobado-González and García Montero2010), as they find that wages in terms of superior goods (i.e. meat and sugar) were in New Spain among the highest in the world.Footnote 15 This is also the case for a significant number of Hispanic-American towns.

Challú and Gómez-Galvarriato (Reference Challú and Gómez-Galvarriato2015, p. 105) do not contradict the picture we are showing: «Mexico City's real wages were high in an international perspective by the mid-18th century, only moderately below those of northwestern European cities. Yet, real wages hit a low point by the end of the colonial period and the decade of insurrection». Despite the decline in welfare ratios—estimated by using a somewhat modified «respectable» consumption basket—some brief comments may be appropriate. Firstly, the average welfare ratios in terms of the «bare bones» basket were higher in 1730-1780 than afterwards, the first third of the 20th century included. Using the «respectable» basket, the difference is not as obvious. Secondly, even in 1800, Mexico City's respectable welfare ratio was still higher than in many European cities. They continue to be clearly above those in Beijing and Kyoto/Tokyo. Thirdly, it should be noticed that welfare ratios of unskilled building labourers in most European towns decreased between 1700-1749 and 1750-1799 and fell further in many cases in 1800-1849 (Allen Reference Allen2001, p. 428).

The study of biological living standards reinforces our argument. Dobado and García-Hiernaux (Reference Dobado-González and Garcia-Hiernaux2017) examine the biological welfare of an unprecedented large sample (nearly 20,000 non-Indian males, aged between 16 and 39 years) from 24 localities of Central New Spain in the early 1790s. One of the main outcomes of this research is that the heights of these potential militiamen were comparable to those of Southern Europeans. This similarity probably proves counterintuitive for many anthropometrics practitioners. Finding that unprivileged mulatos could be as tall, or even taller, than españoles and always reached heights above other socioeconomically intermediate ethnicities or castas (castizos and mestizos) is also unexpected.

Summing up, Arroyo and Van Zanden (Reference Arroyo Abad and Van Zanden2016, pp. 1202-1203) claim that Hispanic America «was probably much more dynamic than previously assumed –the main point of this article. Yet this growth was intimately connected to booms and busts in the mining industry…». Notwithstanding, they detect a downward turning point in the 1780s.

Once again, we are just interested in showing that whether or not New Spain declined from the 1780s, economic dynamism and relatively high living standards prevailed during most of the 18th century and probably also during the first decade of the 19th century.Footnote 16 Thus, available quantitative evidence supports the notion that a significant part of the population in New Spain, perhaps especially in Mexico City, lived above the level of subsistence. This finding is consistent with Yuste's impression (1995, p. 240) that, regarding at least the second half of the 18th century: «the goods transported by the galleon were accessible for the middle and even the poor segments of the population».Footnote 17

Looking at the third demand factor, inequality matters indeed. The dominant notion is that New Spain, and the whole of Hispanic America for that matter, reached extreme levels of inequality. Surprisingly enough, this widespread and influential claim lacks empirical evidence. One exception is Milanovic et al. (Reference Milanovic, Lindert and Williamson2011), whose estimates of inequality for late 18th-century Mexico place it—along with Chile in 1861—at the very top of their sample of 28 historical cases, from the Roman Empire in 14 A.D. to British India in 1947. However, several remarks are necessary.

New Spain lies beyond the interesting concept of the Inequality Possibility Frontier (IPF) which indicates that something affects this case.Footnote 18 In contrast, using a more accurate translation of the old-fashioned Spanish in which the text of bishop Manuel Abad y Queipo—the source of Milanovic et al. (Reference Milanovic, Lindert and Williamson2011, pp. 255-272)—was written, reduces the Gini Index by several points. Moreover, the income distribution between classes estimated by Manuel Abad y Queipo still needs to be proved. Finally, we must point out that the consumer revolution was possible in societies such as Holland (1732), England (1801) and the Netherlands (1808), whose Gini indices are close to that of New Spain (c. 1790), although with a higher level of income.

Alternatively, Dobado and García-Montero (Reference Dobado-González and García Montero2010) present an ad hoc Williamson inequality index for some towns and countries (20), including modern Bolivia, Colombia and Mexico City, as well as others in North America, Europe and Asia.Footnote 19 The outcome of this exercise is that inequality among Hispanic American «should not be considered high by Western standards at the end of the Bourbon period».Footnote 20 The three Hispanic-American cases are among the least unequal ones, only behind the United States and Turkey.

This much less pessimistic view of inequality in Hispanic America is uncommon in mainstream literature. However, it is also shared by prestigious economic historians. Coatsworth (Reference Coatsworth2008) denies the existence of a level of inequality higher than in the thirteen colonies or the USA. Williamson (Reference Williamson2009, p. 1) does not find any «inequality curse» in this part of the world: «compared with the rest of the world, inequality was not high in pre-conquest 1491, nor was it high in the post-conquest decades following 1492».

Thus, we conclude that inequality in New Spain was lower than usually assumed and not a stronger impediment than in Europe to the consumption of Asian goods.

Passing on to the supply side factors, we will consider first, low prices and second, the diversification of products and prices.

After the first impression caused by the attractive novelties coming from the East, the success of Asian goods was, for the largest part, due to their low prices rather than too high quality. Bonialian (Reference Bonialian2012, p. 202) points out the «mediocre quality» of the Asian silk textiles imported to New Spain as the key factor for explaining why their prices were lower than those of the European manufactures. Fernández-de-Pinedo and Thépaut-Cabasset (Reference Fernandez De Pinedo, Thépaut-Cabasset, Dobado-González and García-Hiernaux2021, pp. 282-285) state that «silk consumption by lower-class groups with little purchasing power was possible through this wide variety of quality and thus prices». Jean de Monségur (1709, p. 315) also claimed that low prices—not high quality—of Chinese silk and Indian cotton was an important factor to explain why «their consumption [in New Spain] is large».Footnote 21

By the mid-18th century, in its demand to the King for protection from the Chinese competitors, the Spanish lobby of textile exporters argued about the «inferior different quality» of the Chinese textiles when compared with their European counterparts.Footnote 22 Berg quotes Abbé Raynal's text from 1777: «Valencia [Spain] manufactures pekins superior to those of China».Footnote 23

Commonly associated with luxury and wealth, which is true in several cases, porcelain could have prices lower than usually assumed. Besides other circumstances shared with many Asian goods, transportation costs of porcelain were below the average since it was used as ballast, which was impossible for other merchandise.Footnote 24 Thus, more than 30,000 pieces of porcelain (cups of different types and small dishes), out of a total of 64,357 that were carried from Canton to Manila in 1769 by the vessel Nuestra Señora del Carmen may be considered inexpensive, as opposed to the rest (mainly whole and half crockeries) in spite of being of medium quality—«entrefina» (Díaz Reference Díaz2010). The weighted average price per piece of the former was 0.36 reales or 1.24 grams of silver.Footnote 25

Aside from quality, part of the explanation for the competitiveness of Chinese manufacturers lies in the low level of wages prevailing in Asia. Allen et al. have shown that Smith (1776) was only partially right in his view on prices and wages in China (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Murphy and Schneider2012). Money wages were below those in the most advanced parts of Europe while the cost of living was not significantly different. Therefore, real wages in Suzhou, Beijing and Canton were low if compared with London and Amsterdam. It may be added that it is unlikely that the spectacular growth of the Chinese population over the 18th century, despite the expansion of the agrarian frontier across the interior regions, did not have a negative impact on wages. Both money and real wages were lower in China than in Mexico City. As to India, the wage differential with respect to Europe and Mexico City was even wider (Broadberry and Gupta Reference Broadberry and Gupta2006). Probably, at least in some industries, such as porcelain manufacture, Chinese competitiveness was also favoured by the availability of «fine raw materials and a large, well-organised labour force» (Vainker Reference Vainker2004).

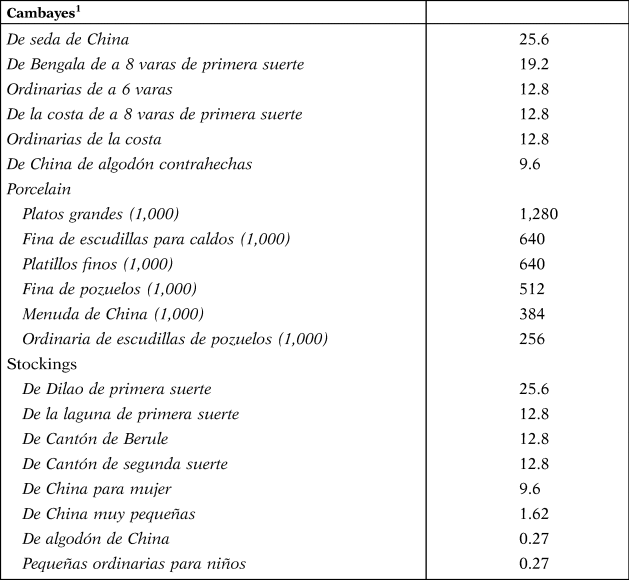

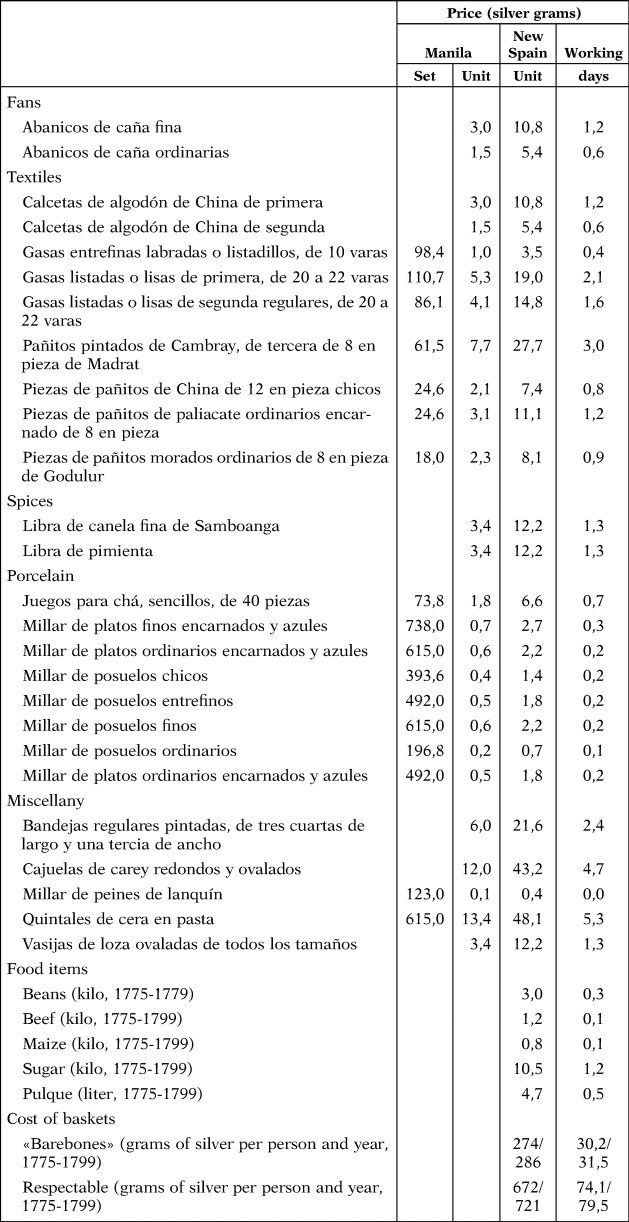

The second supply factor that helps to explain the consumption of Asian goods across a wide spectrum of socioeconomic segments of New Spain's population consists of the diversification of products and prices. This strategy was already practiced by merchants and producers involved in the Manila-Acapulco trade by the early 18th century, although it most probably appeared earlier—see Table 1.

TABLE 1 Stratification of prices (in grams of silver) in selected groups of goods, 1711

Source: Our estimates from data in Archivo General de Indias, Contaduría, Leg. 908, N.1.

1 «A coarse cotton cloth made in India», Merriam-Webster online dictionary.

The relatively small number of items—the total in the appraisal is 213—shown in Table 1 suffices to perceive the essence of price stratification: goods with a large variance of prices and qualities were shipped in the Nao de la China cargoes. They combined expensive goods (silk cambayes or first-rate stockings) with others more accessible (cambayes from Bengal or second-rate stockings from Dilao) or even cheap (cotton cambayes or Chinese female stockings). Somehow surprisingly, porcelain pieces like dishes or cups are more often than not relatively inexpensive (from dishes of 1.35 grams of silver to cups of 0.27 g). Porcelain prices might also vary significantly.

Some authors claim that the price appearing in the avalúos was consciously underestimated by merchants and/or authorities to surpass the limits to the cargo value established in the regulations of the Galleon. That might well be the case, although to an unknown extent. Despite this possible bias, we continue thinking that the source is reliable for our purposes: incentives for underestimating the most expensive items would be stronger than for cheaper goods. Thus, if this assumption is correct, the variance of real prices would be even larger. Besides, assuming that the underestimation was evenly distributed across the whole cargo, the variance of price can still be used as an indicator for the diversification of prices. Moreover, Monségur provides figures for the decade of 1700 that do not stand far away from the ones available through the avalúos.

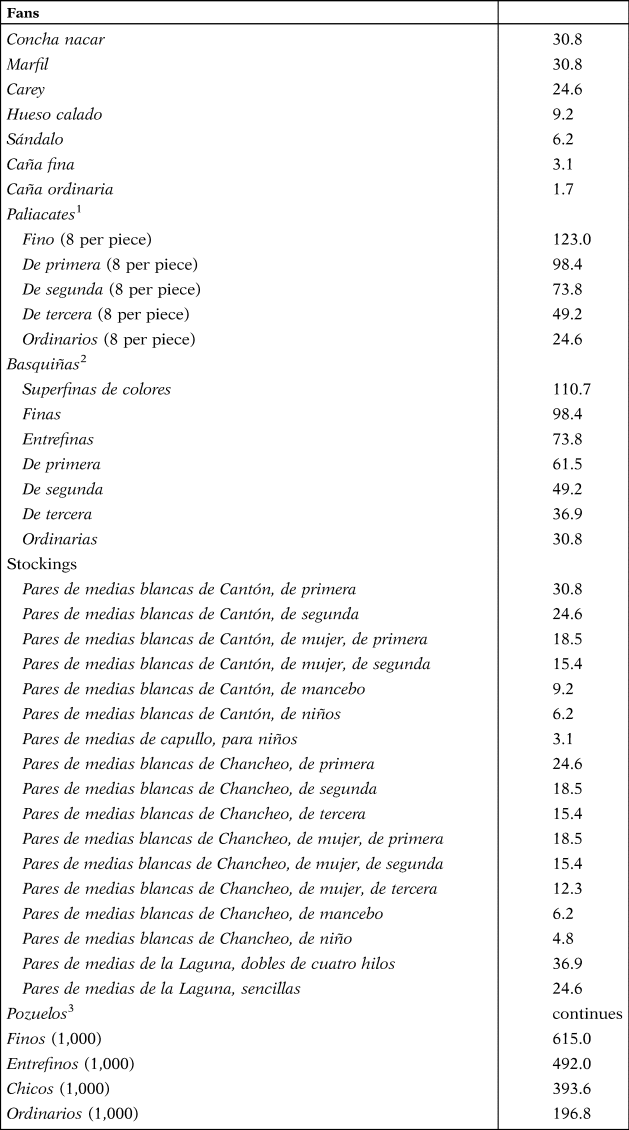

This flexible strategy seems to be part of the explanation of the consumer revolution in Early Modern New Spain since it permitted the acquisition of Asian goods by populations with many different income levels: from the impressive porcelain services decorated with the coats of arms of the elite families and lavish lacquer screens to the much humbler cotton handkerchiefs (paliacates, after Pulicat, India) that are still used in many male-typical dresses throughout contemporary Mexico. Product and price diversification are still even more observable by the end of the 18th century—see Table 2.

TABLE 2 Stratification of prices (grams of silver) in selected groups of goods, 1789

Source: Our estimates from data in Archivo General de Indias, Filipinas, Leg. 954.

1 Indian cloth from Pulicat.

2 Particular type of long skirt with folds, Diccionario de Autoridades, Volume VI, 1736, Real Academia Española.

3 Porcelain bowls.

In 1789, the avalúo registered 510 items. Between 1711 and 1789 price diversification increased: the number of stocking types doubled while that of cambayes more than tripled. Some goods were incredibly cheap (for example, abanicos de calidad ordinaria or pozuelos ordinarios). Thus, in 1789, even more clearly than in 1711, the cargo of the galleons could presumably match the desires and possibilities of a significant part of a population that economically was more prosperous and heterogeneous than many would expect. In fact, some documents clearly distinguish between goods that were sold to «people of taste»—fragrances, curiosities of gold, pearls and diamonds—and others (the cheapest textiles) consumed by «the poor people».Footnote 26

We finish with a numerical exercise intended to check whether or not a significant part of Asian goods was accessible to the lower segments of the working class in New Spain. We have thus estimated its purchasing power in terms of Asian goods. Nonetheless, some problems need to be solved before making the estimates. Information about prices in Manila is abundant. On the contrary, prices paid in Acapulco and, particularly, in Mexico City and other locations in New Spain are very difficult to find—a specialist wonders about the lack of data on prices from the Acapulco fair (Yuste Reference Yuste López1995, p. 237).

The above-mentioned document from 1748 is especially useful for our purposes because it includes an estimate of the increase in prices of the cargo between Manila and Acapulco.Footnote 27 Depending on the good, prices roughly doubled or even tripled. Curiously, this differential is similar to the gross margins of the Asian trade conducted through the Cape route by the European East India Companies (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, East India Company and Compagnie des Indes [hereafter VOC, EIC and C de I, respectively]) in the period comprised between 1641 and 1828, as shown in De Vries (Reference De Vries2010, p. 728, Table 2). The similarity is reinforced by the gross margins of the Dutch Asiatic trade estimated by De Zwart (Reference De Zwart2016b, p. 50).Footnote 28 Based on data offered by Yuste (Reference Yuste López1995) for 61 textile items in 1778, our estimate of the factor of price increase (unweighted average) from Manila to Acapulco is 2.7. This figure is not especially high: «prices in Europe for many of these [Asian] products still over double those in Asia even in the late eighteenth century» (De Zwart Reference De Zwart2016a, p. 50).

One more step is needed for calculating real wages in terms of Asian goods: prices increased again after arriving in Acapulco. Thus, we have transformed prices from avalúos into silver grams and multiplied them by the factor resulting from extrapolating the increase in prices between Manila and those charged in 1778 by Francisco Ignacio de Yraeta, one of the major merchants (almaceneros) established in Mexico City, to his commercial correspondents in towns across New Spain.

We have information for ten textile items taken from Yuste (Reference Yuste López1995, p. 240). The arithmetic means—no weighted average can be calculated—of the difference in prices between Manila and New Spain towns other than Acapulco equals a factor of 3.6. We apply this factor to the prices of the avalúo of 1789 under the assumption that the factor of price increase remained nearly constant. As representative wages in grams of silver, we use those of the unqualified construction workers for 1789 taken from Challú and Gómez-Galvarriato (Reference Challú and Gómez-Galvarriato2015). Once we have a proxy for the prices of Asian goods, and a representative wage, we can estimate the number of working days needed for its acquisition by ordinary people. Certainly, our exercise yields a very crude estimate of the purchasing power of New Spain labourers in terms of Asian goods. However, to the best of our knowledge, nothing similar has been done so far, despite its intrinsic interest in deepening our knowledge of the consumer revolution. In this respect, the comparison with European countries appears to be a promising extension of this research.

In our exercise, we only consider those goods for which it is possible to estimate the price per unit and that are in the low or medium price ranges per unit. Then, many goods have been excluded. In other cases, the available information makes it impossible to ascertain what the goods registered were. However, those that appear in Table 3 may be taken as evidence of the participation of wage earners of Mexico City in the consumer revolution. To make sense of the results shown in the column «Working days», Table 3 also includes the prices of some food items and the cost of living.

TABLE 3 Working days needed by unqualified construction workers to buy selected Asian goods and food items and the cost of consumption baskets, 1789 and 1775-1799

Sources: Our estimates with data from AGI, Filipinas, Leg. 954 and Challú and Gómez Galvarriato (Reference Challú and Gómez-Galvarriato2015).

Therefore, the main conclusions that can be derived from Table 3 are that even some Asian goods of medium quality—fans, hair combs, textiles and porcelain—could be acquired with only a fraction of the daily wage of unqualified construction workers; that many of those goods were in the same range of prices as basic food items; and that, assuming the conventional 250 working days per year and the equivalence to three adults for estimating family calories intake as Challú and Gómez-Galvarriato, the yearly income of this segment of the population—let alone others above it—sufficed to enjoy relatively high living standards and therefore to purchase Asian goods. These authors estimate that the yearly income of the representative wage earner was 2,267.5 silver grams. Irrespective of consuming the «barebones» or the «respectable» basket, there is a positive difference between earnings and expenses: almost 1,500 silver grams in the first case and more than a hundred in the second one. If, as it was the most common situation for families, spouses and children from a certain age also obtained earnings for the domestic economy, this domestic budget surplus increases (Calderón-Fernández et al. Reference Calderón-Fernández, García Montero, Llopis Agelán, Pieper, de Lozanne Jefferies and Denzel2017).

If these conclusions seem solid enough regarding the last decades of the 18th century, they might be valid for the 17th century as well. As to prices, it is most likely that the market power of the big merchants engaged in the Manila-Acapulco trade and the volume of it decreased at least, if not before, from the mid-1780s and on, when the competing Real Compañía de Filipinas started its operations and Manila was declared a port open to international trade (Martínez Shaw Reference Martínez Shaw2007). More competition implies lower prices. However, from 1680 to 1730, New Spain experienced an excess of supply over demand with the associated similar consequence of low prices (Bonialian Reference Bonialian2012). Therefore, we can safely assume that prices of Asian goods c. 1700 or before were not necessarily very different from those recorded in 1789. The study on Spanish American real wages between the 1520s and the 1810s by Arroyo et al. finds that they were at their highest, albeit with some fluctuations, from the 1670s to the 1770s (Arroyo et al. Reference Arroyo Abad, Davies and Van Zanden2012).

Although we still have to deepen our research of this period, the inference that common people might have been consuming some Asian products from the very beginning—or not much later—of the operation of the Galleon does not seem implausible. It would be interesting to compare our results with similar estimates for European countries.

What are the factors that might explain the difference between Old and New Spain in terms of the consumption of Asian goods? Since demand factors did not differ significantly from each other, we may assume that supply factors were more important. As claimed by Gasch-Tomás (Reference Gasch-Tomás2014), transportation costs were higher in Spain because Asian goods arrived mostly—smuggling apart—through intra-imperial trade via Manila-Acapulco-Veracruz-Seville or Cádiz. This was so from the late 16th century until the second half of the 18th century. Transportation costs continued to be considerably high at least until 1765. That year direct, even if irregular, contact between Spain and the Philippines was established, with available information pointing out an increase in imports of porcelain. In 1785, the Real Compañía de Filipinas was created under a royal charter (Martínez Shaw Reference Martínez Shaw2007). It opened a trade factory in Canton soon afterward. However, Asian goods still faced the problems of moving merchandise throughout Spain, where geography conspires against inland trade.

Additionally, the existence of substitute products and the metropolitan economic policy ought to be considered. The century-long ceramic tradition in Spain could detract from the acquisition of Asian porcelain, except among the wealthiest classes. In the Iberian Peninsula, including Portugal, the population had access to a broad variety of ceramics in terms of quality and price. Moreover, following other European examples, a royal factory of porcelain—the Real Fábrica de Porcelana del Buen Retiro—was opened in Madrid in 1760. During the 18th century, an increasingly protectionist policy towards Spanish textiles was implemented (Fernández de Pinedo Reference Fernández De Pinedo Fernández1986). Thus, Asian fabrics entered more easily in the unprotected Spanish American market than in the metropolis.

4. FINAL REMARKS

In this article, we have contributed to a more complete understanding of the global circulation and consumption processes of Asian goods in early modern times by including New Spain in the picture. New Spain played a critical role as the main consumer of those initially exotic merchandise within the Spanish Empire but also as the channel of their distribution across other Hispanic American territories and the metropolis. The direct connection between New Spain and the Philippines since 1565, along with improved living standards and new lifestyles of the population in the Americas, caused an early consumer revolution, at least in the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The assimilation of Asian goods into everyday life and culture in New Spain has not received enough attention. Therefore, this extra-European part of the world barely appears in the mainstream literature on the consumer revolution of the Early Modern Era.

In this research, we have brought to light how supply and demand matched, especially in Mexico City, and built a new consumer market for Asian goods as economic, social and cultural evidence (hybrid fashion, salaries, caste paintings, porcelain, portraits, etc.) suggests. The evolution of preferences and the rise in living standards played a significant role in the modes and motivation of consumption. Contrary to what occurred in Britain, these early and deep changes in consumption patterns did not turn into an industrial revolution. However, the deployment of Asian goods in New Spain goes beyond their eventual consumption as luxury products by the elites and contributed to a genuine consumer revolution by reaching all social groups, although not with the same intensity across the whole society, which is common to all known cases. This fact suggests that New Spain was one of the pioneers of the early globalisation that made possible the consumer revolution in the West as a wide majority of Manila Galleons with their cargo of Asian goods finished their incredibly hard Pacific crossing in the New Spanish harbour of Acapulco. In exchange, New Spain sent to Asia via Manila huge amounts of silver in the form of pesos (Spanish dollars), the global currency of the Early Modern Era.

Conventional quantitative and qualitative sources have been used to identify the demand and supply factors that help to explain why a consumer revolution took place in a territory generally assumed to be poor and unequal. To the best of our knowledge, some original data and estimates are unprecedented, at least in the literature in English, French and Spanish. Our numerical exercise intended to check whether the commoners (i.e. unqualified construction workers of Mexico City) could access a variety of cheap and medium-priced Asian goods with little labour effort constitutes a novel approach to the study of living standards. In some cases, that effort was lower than the one required for buying subsistence goods. Therefore, this article also adds to the knowledge of the economic history of pre-independent Mexico from an original perspective.

Among the demand factors, three of them deserve careful consideration: (a) the pre-industrial economic growth experienced by New Spain until the 1780s or the early 19th century; (b) high or very high real wages by international standards; and (c) lower inequality than usually attributed to this Viceroyalty. However, GDP per capita was lower than in England or the Netherlands, although not as much as generally assumed. As to the English market for Asian goods, the difference in income was amplified by that in the population (8.6 compared to 6 million) and by the re-exports of the East India Company to other European countries. Regarding the Netherlands, re-exports by the VOC to markets across Europe complemented the small size of their relatively rich population (1.9 million).Footnote 29 Thus, the market in New Spain was probably smaller in absolute and relative terms but far from insignificant.

Some of the most relevant supply factors were the following: (a) although, with a significant number of exceptions, many Asian goods were very cheap (e.g. silk and porcelain included, not to mention fans and others); (b) the stratification of products and prices (e.g. fans, stockings, cambayas, porcelain, etc.) that made accessible the purchase of Asian goods for almost every segment of the socioeconomic layer. In 1789, diversification was larger than in 1711 (e.g. 17 types of stocking vs. 8). The goods placed at the bottom level of the scale of quality and price were cheap (e.g. ordinary pieces of porcelain cost 0.2 grams of silver per unit) because of the availability of raw materials, the abundance of poorly paid workers and the efficient organisation of labour in some productive sectors could explain the competitiveness of Chinese manufactures, etc.

We have also taken advantage of other less conventional sources, such as artistic illustrations (i.e. casta paintings) and research by other scholars (e.g. Asian aesthetics and techniques were soon adapted and influenced New Spain's artisans’ crafts production; the Parián market where Asian goods were traded occupied a privileged place in Mexico City's main square in which commoners, even those belonging to the lower ethnic groups might access the consumption of some Asian goods). Cargo of shipwrecks and probate inventories demonstrate the diffusion of Asian goods since the late 16th century.

What is certain is that the increasingly widespread consumption of Asian silks—textiles constituted by far the bulk of the Manila Galleon's cargo—was due to a sharp increase in the supply of high-end and low-end fabrics. This facilitates access to fashionable textiles that were at the same time differentiated by their quality and price. Asia was probably the largest mass fashion producer in the Early Modern Era and the Manila Galleons acted as its vehicle to Hispanic America in exchange for silver.

As opposed to New Spain, nothing similar occurred in Spain. By the mid-18th century, only the affluent and powerful elites were able to buy Asian goods. Higher transportation costs, substitutive products (i.e. ceramics) and protectionism in Spain (not in Hispanic America) ought to be considered for explaining the somewhat surprising difference observed between metropolis and «colonies» concerning the consumption of Asian goods. All in all, an inference from our work is that some assumptions about the—negative—economic effects of the Spanish rule in America should be reconsidered.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Comments and criticism by Aurora Gómez-Galvarriato, Herbert Klein, Carlos Marichal and Víctor Muñoz have contributed to improve the first versions of this paper. Reviewers and editors have made the text much more appropriate for being published in RHE/JILAEH. Rafael Dobado is grateful to the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2019-109435GB-I00). Nadia Fernández de Pinedo has also received financial support from the same Ministry (PID2021-124378NB-I00).