Sulemaana Kantè is best known for his 1949 invention of a non-Latin-, non-Arabic-based script called N’ko.Footnote 1 A prolific author until his death from diabetes in 1987, he used his unique script to write over one hundred books—spanning across such diverse topics as linguistics, history, traditional medicine, and Islam—which continue to be typeset and published today. Kantè’s most enduring legacy, however, is neither his script nor any one of the many books that he authored using it. Instead, it is the thousands of West Africans who dedicate themselves to the study and promotion of his creation as either a pan-African script or a Manding orthography. Understanding what animates the N’koïsants of today, though, is near impossible without a proper understanding of Kantè as the first N’ko kàramɔ́ɔ (ߒߞߏ ߞߊ߬ߙߊ߲߬ߡߐ߮) or ‘teacher.’Footnote 2

Scholarly accounts thus far (Amselle 2001; Oyler Reference Osborn2005; Wyrod Reference Wilks, Levtzion and Pouwels2003) have underemphasized connections between the inventor of the N’ko alphabet and his historical and contemporaneous Muslim counterparts in what post-colonially became “the Islamic sphere” (Launay & Soares Reference Launay1999). Kantè was a particular iteration of what I call “the Afro-Muslim vernacular tradition.” He emerged from the regional West African Quranic schooling network and expressed similar sentiments to earlier Ajami intellectuals who had sought to strengthen Islam through literacy in local African languages. Like his predecessors, he faced skepticism—though colored by his particular historical moment following World War II. Put broadly, traditional scholars saw a new writing system and mother-tongue education as a threat to their livelihoods, while rival reformers, the so-called Wahhabis, favored a pan-Islamic identity over the Afro-centric one favored by Kantè that melded pan-Africanism and ethno-nationalism.

In the following three sections, I focus on Kantè, the kàramɔ́ɔ, in the full Muslim clerisy sense of the term. First, I introduce his upbringing in the Quranic schooling tradition of West Africa. Second, I lay out parallels between him and his predecessors in an Afro-Muslim tradition which viewed vernacular writing in Arabic script (that is, Ajami) as a tool for both strengthening Islam and responding to particular socio-political circumstances. Finally, I explore the specifics of Kantè’s N’ko as an iteration of the above traditions influenced by the social forces that were active following World War II and into the earlier years of African independence.

Kantè as a Product of the Afro-Muslim Vernacular Tradition

Born in 1922, in the Baté (ߓߊߕߍ߫ bátɛ, literally “between rivers”) region of what is now Guinea, Kantè was early on integrated into Islam, which had been present in parts of sub-Saharan West Africa since approximately the ninth century (Austen Reference Asad2010:85–86; Tamari & Bondarev Reference Tamari, Brigaglia and Nobili2013:4; Ware III Reference Vydrin, Mumin and Versteegh2014:85).Footnote 3 Like many West African Muslims before him, Kantè was familiar with the Arabic language (Hunwick Reference Hornberger and Johnson1964)—though his knowledge went much further than many—thanks to both the centrality of Quranic verses to prayer and other religious acts. Kantè’s interest in the written word was instilled in him and his eleven siblings from an early age. While none of them would follow their father’s career path as a móri (ߡߏߙߌ “Quranic school teacher” often used interchangeably with ߞߊ߬ߙߊ߲߬ߡߐ߮ kàramɔ́ɔ), they all, at one point or another, attended the school that was their family’s livelihood.Footnote 4

The vast majority of the elder Kantè’s students would have only attended Quranic school at the first of two levels: the so-called basic level during which a student, for a span of time ranging from a few months to a few years, focuses on learning the “fundamental elements of Islamic religious obligation,” such as the proper techniques for ritual ablution, prayer, and the recitation of at least some verses of the Quran (Brenner Reference Brenner2008:220).Footnote 5 Given that Arabic is rarely the mother tongue of West Africans, this early focus on the Quran inevitably entails some rote memorization, but it is far from mindless as suggested in colonial documents (e.g., Mairot 1905 in Turcotte Reference Tamari and Bondarev1983); the elementary cycle itself is divided into numerous discrete stages before students with sufficient mastery of Arabic move onto the second level with its focus on advanced subjects of the Islamic Sciences.Footnote 6

Through this tradition and his father’s teaching, Kantè came to master literary Arabic, a language with a historical status akin to the Latin of West Africa (see Hunwick Reference Hunwick2004). This written lingua franca had spread not because of Arabic-speaking conquerors, but rather, thanks to the clerical efforts and unique status of Quranic teachers, or “walking Qurans” (Ware III Reference Vydrin, Mumin and Versteegh2014), who were free in many cases to travel and settle across West Africa for centuries prior to colonial rule.Footnote 7 These same scholars’ skills in Arabic literacy were also applied to the administrative and communication needs of various West African polities and courts such as that of Mali’s Mansa Musa in the fourteenth century.Footnote 8 Linguistic analysis has also long provided evidence of this history of Arabic as a regional language of learning and correspondence (see Green & Boutz Reference Fófana2016; Zappa Reference Wyrod2011). Kantè likely noted this early on in his education; later he (2007/1958) would write:

While his education took place primarily in Arabic, Kantè reports having been introduced formally to the practice of writing a sub-Saharan African language in Arabic script in 1941.Footnote 9 In this way, he was likely connected to an older tradition; residents of the Batè region probably began flirting with writing their own language sometime in the nineteenth century.Footnote 10 At the time however, Kantè was not impressed. Presented with a history—written in Manding by his grandfather and maternal uncle using the Arabic script—of the ethnic Fulani of the pre-colonial polities of Batè and neighboring Wasolon, he found that he could not read the text. His uncle’s remark that the document served primarily as memory-jogging device for the author did little to convince Kantè, who recalled thinking:

Blinded, as he would later put it, to facts demonstrating that writing did not in fact stem from God, Kantè thought little more of writing African languages for the next few years (Sangaré 2011).

A number of other West Africans in the centuries before him had not reached the same hasty conclusion. And while they did not arrive at his ultimate solution of inventing a script, these Muslim scholars often had trajectories and ideas similar to those that Kantè would later develop regarding mother-tongue education.

Kantè’s Desire to Strengthen Islam as Stemming from the Vernacular Ajami Tradition

Important initial academic scholarship on N’ko analyzes it as a primarily anti-colonial intellectual movement.Footnote 11 Refining this work, Jean-Loup Amselle (2001; Reference Amselle2003) rightfully highlights N’ko’s connection with Islam and the wider Muslim world. On his account, however, N’ko is an ethno-religious fundamentalist movement that utilizes the “invented tradition” (Ranger Reference Peterson, Hoyt and Oslund2010) of French colonial Islam noir (“Black Islam”) to combat the efforts of West African Muslim Wahhabi reformists (Kaba Reference Kaba1974; Brenner Reference Brenner, Brenner and Sanankoua2001) and thereby preserve “a ‘Negro-african’ specificity within the Muslim community” (Amselle Reference Amselle2003:257).Footnote 12 His overly harsh positioning of N’ko activists as fundamentalists aside, Amselle’s analysis does not properly situate Kantè’s thoughts and actions within the West African Quranic tradition. Islam figures prominently in Kantè’s (2008a:7) characterization of his intellectual oeuvre and must be taken seriously:Footnote 13

Just as the script of Rome was eventually co-opted for penning a number of other languages besides Latin, the Quranic tradition of Arabic literacy also lent itself to the development of a written tradition for a large number of sub-Saharan African languages.Footnote 14 Today, this tradition of writing local vernaculars in the Arabic script is commonly referred to in West Africanist research as Ajami (from the Arabic ʿajam, عجم ‘non-Arab, Persian’).Footnote 15 The earliest evidence that we have of such literacy in the region dates back to the seventeenth century, when a scholar residing in the Kanem state north of Lake Chad inserted interlinear glosses of Kanuri inside a copy of the Quran (Bondarev Reference Brenner and Last2013; Tamari & Bondarev Reference Tamari, Brigaglia and Nobili2013). Existing documents and research thus far suggest that it was during the eighteenth century that robust traditions of Ajami began to emerge for a number of West African languages. In many cases, Ajami was a “grassroots literacy” (Blommaert Reference Baldi2008) that existed in the Quranic schooling system’s margins. In other cases, however, Ajami literacy was “undertaken by individual scholars to solve language problems and modify the linguistic behaviours in West African communities” (Diallo Reference Derive2012:97). Such efforts to modify linguistic and literacy practices—as all instances of language planning—were part and parcel of quests for social change.Footnote 16 Analyzing the voices of the Ajami tradition therefore allows us to better understand how Kantè did not simply co-opt French colonial Islam noir but rather innovated within a much longer tradition expressed in, though not exclusive to, vernacular thought.

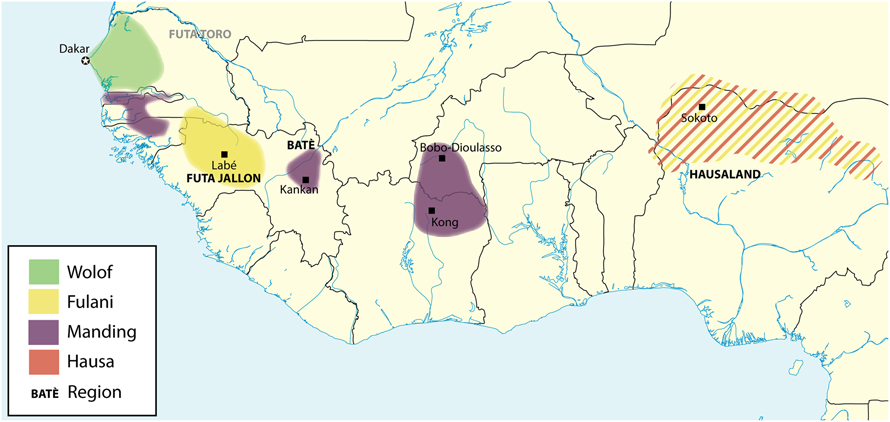

In what follows, I briefly sketch the intertwined emergence of Ajami literacy traditions in four major West African languages of the Muslim Sahel.Footnote 17 See Figure 1 for a non-exhaustive map of these language’s Ajami traditions and their relevant locales.

Figure 1. Map of select traditions of Manding, Wolof, Fulani, and Hausa Ajami literacy

Fulani and Hausa

The eighteenth century gave rise to two regional traditions of Fulani Ajami in Fuuta Jaloo (spelled Fouta-Djallon in French) and Hausaland, in modern-day Guinea and Nigeria respectively (see Hunwick Reference Hunwick2004; Zito Reference Zappa, Lancioni and Bettini2012). In both cases, the emergence of Ajami was tightly connected to Fulani Jihads which aimed to spread Islam and which gave rise to the aforementioned polities.

In Fuuta Jaloo, the first known Ajami practitioner was Cerno Samba Mambeyaa, (1755–1852), who explicitly justifies his decision to write in Fulani as follows:

I shall use the Fulfulde [Fulani] tongue to explain the dogma.

In order to make their understanding easier: when you hear them, accept them!

For only your own tongue will allow you to understand what the Original texts say. Among the Fulani, many people doubt what they read in Arabic and so remain in a state of uncertainty.

(Salvaing Reference Robinson2004:111–12)

To this end, Mambeyaa’s works were primarily religious texts written in verse form that may have emulated the oral commentaries traditionally performed to the public by Fulani clerics. His innovation therefore was to believe that regular Fulani should have access to these commentaries in written form. Such a shift, in his mind, would strengthen Islam and spread religious fervor among the Fulani people. This goal remained central; at the end of the nineteenth century, all Fuuta Jaloo Ajami writings continued to focus on religious matters (Salvaing Reference Robinson2004:111–12).

Similarly, Fulani Ajami emerged with Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio’s (1754–1817) rise to power in establishing the nineteenth-century Sokoto caliphate in what is now largely northern Nigeria.Footnote 18 Dan Fodio’s zeal to spread Islam among the general populace led to the flourishing of both Fulani and eventually Hausa Ajami. While Dan Fodio himself wrote primarily in Arabic, he did pen a number of original texts as well as translations of his Arabic works into Fulani, his mother tongue, and Hausa, the dominant language of the conquered masses. Echoing Mambeyaa’s concern with propagating Islam, Dan Fodio began one of his poems as follows:

My intention is to compose a poem on the [prostration] of forgetfulness.

I intend to compose it in Fulfulde [viz. Fulani] so that Fulbe [viz. Fulani] could be enlightened.

When we compose [a poem] in Arabic only the learned benefit.

When we compose it in Fulfulde the unlettered also gain. (Diallo Reference Derive2012:1)

Thus, while learned discourse took place in written Arabic, Dan Fodio believed that disseminating Islamic knowledge more broadly could be assisted by composing the kinds of verses that had served to spread Islam orally in years prior.Footnote 19 This trend and encouragement from Dan Fodio would give rise to a robust tradition of Fulani and increasingly Hausa Ajami that was carried out by his disciples and those in his entourage such as his brother as well as his daughter, Nana Asmā’u (see Mack & Boyd Reference Levtzion2000).

As evidenced by the declarations of both Dan Fodio and Mambeyaa, this evolution was not an unquestioned natural progression. Indeed, local tradition suggests that Mambeyaa’s efforts were opposed by Umar Tal (1794–1864), the leader of the first major Fulani jihad that took place around the Senegal River’s region of Fuuta Tooro (Salvaing Reference Robinson2004). Tal’s position along with Fuuta Tooro’s proximity to the Moors of West Africa have also been advanced as reasons for the lack of a robust Ajami tradition in this other major Fulani area (see Ngom Reference Mumin and Versteegh2009:101; Robinson Reference Ranger, Grinker, Lubkemann and Steiner1982).Footnote 20 This tension and its connection to race debates within Islam in West Africa emerge even more strongly in the case of Wolof.

Wolof

The Ajami tradition of Wolof, commonly referred to as Wolofal, emerged primarily out of the Sufi Muslim brotherhood, the Muridiyya (المريدية al-murı¯dı¯yya), established by Shaykh Amadu Bamba (1850–1927). Wolofal is still extensively practiced in Senegal today in both formal publications and more mundane record-keeping, signs, and correspondence (Ngom Reference Ngom2010). Fallou Ngom (Reference Mumin and Versteegh2009; Reference Ngom2016) suggests that the nineteenth century flourishing of Wolof Ajami can be traced to the personality and teachings of Amadu Bamba. The Muriddiya’s leader asserted a strong African identity as part of his broader Islamic message; he addressed French colonialism and its supposed superiority but he also “differentiated the essence of Islamic teaching from Arab and Moorish cultural practices with no spiritual significance” (Ngom Reference Mumin and Versteegh2009:104). Bamba, for instance, did not claim Sharifan or Arab descent for prestige or to legitimize his message.Footnote 21 While he did not write in Wolofal himself, he supported its development and use by his senior disciples such as Muusaa Ka (Camara Reference Bondarev1997) who used it to spread Islam and Bamba’s message to the masses. In this sense, Wolof Ajami emerged for the same reason as that of Fulani and Hausa—to more effectively promote Islam and religious teachings. As Muusaa Ka explains in the introduction to one of his poems:

The reason this poem—which should have been sacred—is written in Wolof

Is that I hope to illuminate the unknowing about his Lord. (Camara Reference Bondarev1997:170)

According to Fallou Ngom (Reference Mumin and Versteegh2009), this aim is also connected to Bamba’s own desire for African cultural autonomy. At least once in writing, Bamba explicitly engaged with the issue of race and hierarchy within Islam; in his work Masa¯lik al-Jina¯n (مسالك الجنان “Itineraries of Heaven”) he writes:

Do not let my condition of a black man mislead you about the virtue of this work, because the best of man before God, without discrimination, is the one who fears him the most, and skin color cannot be the cause of stupidity or ignorance. (cited in Babou Reference Austen2007:62)

From this position, Bamba (similarly to Kantè in the twentieth century) had no qualms calling upon traditions such as Wolof proverbs as a means to translate his Islamic message to the Wolof masses (Ngom Reference Mumin and Versteegh2009:107). While he himself wrote in Arabic, perhaps because of a spiritual desire to “commune with God and the prophet Muhammed” (Camara Reference Bondarev1997:170), Bamba articulated an explicit Afro-Muslim identity that gave “ideological and implementational space” (Hornberger & Johnson Reference Green and Boutz2007) for local language Ajami literacy to flourish. This overt engagement with issues of race and cultural autonomy within Islam makes the Wolofal tradition seemingly unique, but ethnic relationships—mediated, today at least, in part by notions of race—are alluded to in other accounts of Ajami literature’s emergence (see Ngom Reference Mumin and Versteegh2009 for Fulani/Moor and Robinson Reference Ranger, Grinker, Lubkemann and Steiner1982 for Fulani/Manding).

Manding

Sulemaana Kantè did not emerge directly from the Wolof, Hausa, or Fulani traditions. He grew up, however, in a place with close ties to the historical region Màndén, which gave rise to what historians refer to as the Mali empire.Footnote 22 While it is unclear what role Islam played among this polity’s masses, we have evidence that Arabic was used in Mali’s court and was even spoken by the empire’s sovereign, Mansa Musa, when he performed his pilgrimage to Mecca in the fourteenth century (Hunwick Reference Hornberger and Johnson1964). Nonetheless, a Friday prayer in Arabic was translated spontaneously into Manding in the fourteenth century and therefore it seems likely that the language was a developed medium of oral scholarly discussion and religious propagation by the fifteenth century.Footnote 23 The oldest tradition of Islam among Manding speakers seems to be traceable to the jùlá network that originated first with Muslim Soninke traders that spread out across West Africa during the Ghana empire that preceded that of Màndén (see Wilks Reference Ware1968, Reference Wilks and Goody2000) (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Map of Màndén, the Ghana and Mali empires, and Jùlá trade network (Sources: Dalby Reference Cooper1971; Launay Reference Last1983; Simonis Reference Sanneh2010)

During the Mali empire, which reached its apogee in the fourteenth century, the Muslim Jula network of traders became increasingly Manding; that is, older Soninke members adopted the language of Mali and were additionally joined by other Manding-speaking Muslims along their trading routes and outposts (Massing Reference Mack and Boyd2000). Thus, while the decline of the Mali empire led to many non-Muslim polities (e.g., Kaabu and Segu) where Ajami would have been less likely to emerge, we nonetheless find evidence of Manding Ajami traditions in a number of areas (Vydrin Reference Turcotte1998; Vydrin Reference Vydrin2014).Footnote 24

Specifically, the Islamic tradition of the Jakhanke Muslim clerics (a western iteration of the Jula network) in southern Senegambia gave rise to Ajami that was attested to as early as the late seventeenth century.Footnote 25 It is also in and around this Mandinka-speaking region that Manding Ajami practices appear the strongest today. The earliest Western documentation of Manding Ajami elsewhere stems primarily from areas in Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire.Footnote 26 Valentin Vydrin (Reference Vydrin2014) suggests that this was surely an area with an older Manding Ajami tradition. Indeed, this part of the Jula network gave rise to the Kong Empire and its vaunted scholarly tradition.Footnote 27 Any Ajami documents that may have existed in Kong were destroyed when the town and its libraries were sacked and burned by Saˇmòri Tùre in the late nineteenth century (see Fofana Reference Dumestre, Vydrin, Mumin and Versteegh1998; Person Reference Oyler1968; Peterson Reference Person2008).Footnote 28 While we know of no major Ajami collections in the zone today, Ajami is still practiced in the margins of the Quranic schooling tradition (Donaldson Reference Diallo2013).

Outside of the western Jakhanke- and Mandinka-speaking areas, it is only in the case of Kantè’s native region around Kankan that we currently have any specific information on a potential pre-twentieth-century Manding Ajami tradition. Kantè considered himself the heir to the work of Alfa Mahmud Kàbá (I. Condé 2008b:135; N. S. Condé Reference Condé2017:117).Footnote 29 Popularly understood as a skilled leader who unified the Batè region in the mid-nineteenth century, Kàbá was also a man of letters. He is known for his works in Arabic as well as his (presumably oral) translation of Islamic poems into Manding.Footnote 30 Ibrahima Condé (2008b) suggests he may have been the first to attempt to pen Manding in the Arabic script. In the early twentieth century, a contemporary and friend of Kantè’s father, Jakagbɛ Talibi Kàbá was also concerned with translating Islamic rites and poems into Manding and is purported to also have attempted to create a unique writing system for Manding (Condé Reference Condé2008b:135).Footnote 31 Despite not having access to any texts, with both of these authors, we see that Manding Ajami arose alongside the Arabic-language tradition, in part, for the purpose of spreading the gospel of Islam.Footnote 32

In sum then, just as West African speakers of Fulani, Hausa, and Wolof pondered the place of their mother tongues in promoting Islam, so did Manding Muslims, despite a relative dearth of identified Ajami textual artifacts in the major Eastern Manding varieties of Bamanan, Jula, and Maninka. Kantè was a direct intellectual heir to Alfa Mahmud Kàbá and Talibi Kàbá of Kankan. However, given the transnational character of Quranic schooling and clerical communities in West Africa, it is important to see that Kantè was also connected indirectly with thinkers among Fulani, Hausa, and Wolof Muslims. In this sense, we have severely underestimated the role of Kantè’s Quranic education in his life and work:

In his reflection on the Manding language and his interest for its different regional varieties, in his quest for a perfectly adequate vocabulary to express theological, philosophical, logic or linguistic concepts, by strongly distinguishing between Islam and Arabness, [Kantè] was pursuing preoccupations and manifesting points of view well anchored amongst clerics [Fr. les lettrés] (Tamari Reference Tamari2006:51–52)

Kantè’s Desire to Reform Islamic Education

N’ko’s founder represents a particular iteration of the Afro-Muslim vernacular tradition. While rooted in the ideas laid out above, Kantè also sought to respond as a Muslim educator and intellectual to his own historical moment of post-World War II and the independence era.

The aftermath of World War II “presented opportunities to political and social movements to take on imperial administrations uncertain of their continued authority and aware of their need of Africans’ contributions to rebuilding imperial economies” (Cooper Reference Conrad2002:26). The post-war moment also revealed tensions in what Robert Launay and Benjamin F. Soares (1999:498) describe as the newly-formed Islamic sphere, “separate […] from ‘particular’ affiliations—ethnicity, kin group membership, ‘caste’ or slave origins, etc.— but also from the colonial (and later the post-colonial) state.” While West African Muslims had undoubtedly always discussed proper membership in the Islamic community, the debate tended to be restricted to internal discussions among the largely hereditary clerical class. The colonial period’s major shifts in political economy disrupted such traditional religious authority and carved out space for larger societal debates about Islam and Muslim identity (Launay & Soares Reference Launay1999:501). As such, as elsewhere on the Continent (Brenner & Last Reference Brenner, Middleton and Miller1985; Peterson Reference Peterson2006), the postwar moment in French West Africa gave rise to unique and competing Muslim experimentations with language-in-education that were designed to address both the French colonial system as well as concerns in the Islamic sphere.

Kantè’s father, Amara, was likely at the origin of the N’ko inventor’s interest in pedagogical reform; the elder Kantè was himself an innovator. His instructional methods facilitated an accelerated program which attracted a large body of Manding-speaking students with origins spread out across West Africa (Sangaré 2011; Oyler Reference Osborn2005).

Sulemaana took responsibility for teaching his father’s students following his father’s death in 1941 (Sangaré Reference Salvaing2011:10–11). By 1942, though, he had decided to seek his fortune away from home and left with the intention to settle either with “people looking for a Quranic teacher” or in “one of the White man’s cities” (Sangaré Reference Salvaing2011:12–13; see also Amselle 2001:150). (See Figure 3 for a map of Kantè’s travels within his broader life.)

Figure 3. Approximate map of Kantè’s post-1941 travels and history of residence in West Africa (as per Amselle Reference Amselle2003; Kántɛ 2013:200; Oyler Reference Osborn2005; Sangaré Reference Salvaing2011)

Kantè’s decision was typical; many young male Sahelian Muslims (oftentimes Manding-speakers) at the time were drawn to the economic opportunities of southern Côte d’Ivoire. For Kantè, it was in the city of Bouaké that the invention of N’ko was set in motion:

It was true, Kantè said, Africans didn’t have a writing system, but it was insult to injury to spread the lie that their languages were deprived of grammar.Footnote 33 His rancor drove him to attempt to write Manding (Sangaré 2011:17–18).

Likely equally important and not sufficiently taken into account in previous analyses, however, are the voices of his fellow Manding-speaking Muslims that he encountered during the same period. The town in which he encountered Marwa’s book was central to the post-War madrasa movement, which established a string of modernist Muslim schools that used Arabic as the medium of instruction but followed the curriculum and practices of Western-style francophone schools.Footnote 34 Bouaké opened its first madrasa school as early as 1948 (Leblanc 1999:492). Such schools were the product, on one hand, of so-called Wahhabi doctrinal reformists that connected during or upon return from sojourns in the Middle East (Kaba Reference Kaba1974) and, on the other, of educational reformists simultaneously questioning the traditional Quranic schooling elite and seeking to prepare students in a Muslim manner for integration into the emerging modern economy (Brenner Reference Blommaert1991:65). Their Arabic language policy stemmed in part from a prevalent rationalist tenant in modernist Islamic circles “that texts are transparent and that grasping their manifest meaning makes their prescriptions clear” (Ware Reference Vydrin, Mumin and Versteegh2014:70).

While any specific encounters with educational reformists or preachers such as Al-Hajj Tiekodo Kamagaté (to whom Kaba [Reference Kaba1974] traces the origin of so-called West African Wahhabi reformism) remain undocumented, Kantè was unquestionably a part of the rising younger generation of so-called jùlá traders in Côte d’Ivoire who were hearing and debating new ideas about Islam and society. For reformists such as Kamagaté, madrasas offered both popular access to Islam through Arabic acquisition in schooling and a means to short-circuit the elite role traditionally played by Quranic teachers as religious intermediaries. Unsurprisingly, those behind this shift to Arabic were also frequently engaged in larger doctrinal critiques of traditional Sufi clerics at the top of the Quranic schooling system (Kaba Reference Kaba1974).

Shortly after encountering Kamal Marwa’s tract, Kantè headed south, eventually settling in Bingerville, where he set up shop as a Quranic teacher before entering the Kola nut trade. His free time was dedicated to devising a way to write Manding (Sangaré 2011:19). N’ko students today largely attribute this quest to the blind, if not racist, ignorance of Marwa. However, analyzing Kantè’s own writings regarding the reactions of fellow Quranic scholars reveals the extent to which his activities were also an attempt to intervene in the Islamic context of both Quranic schools and the newly-formed madrasas.

For three years, he initially experimented with writing Manding with the Arabic script. His efforts were discouraged by those affiliated with Quranic schooling [ߡߏߙߌߟߊߡߐ߯ mórilamɔɔ] (Kántɛ Reference Kántɛ2004:2):

Ultimately, Kantè, however, saw vernacular literacy as having major implications for his religion and its education system. (Kántɛ Reference Kántɛ2004:6):

He subsequently spent two years experimenting with the Latin script, before ultimately concluding that to forge this shortcut, he must create a unique writing system with conventions adapted to the tonal and vowel lengthening systems of West African languages such as Manding.Footnote 35

On April 14, 1949, while residing in Bingerville, Côte d’Ivoire, Sulemaana Kantè, after five years of experimentation, unveiled the non-Arabic, non-Latin-based script of twenty-eight characters written right-to-left that he called N’ko.Footnote 36 He would subsequently dedicate the rest of his life to research, writing, and teaching using his so-called African Phonetic Alphabet. Similarly to the madrasa movement, Kantè’s effort was part of a rationalist project, as revealed in his many writings as “an Enlightenment-style encyclopediast” (Vydrin Reference Vydrin2001:100; Conrad Reference Condé2001). This is most evident in his translation of the Quran (Kántɛ n.d.; Davydov Reference d’Avignon2012) which, if taken as legitimate, removes the need for an Arabic-proficient Quranic teacher to school oneself in Islam. In this respect, N’ko and the madrasa movement therefore were sister reform projects of democratizing access to much of the Islamic knowledge of the traditional Quranic schooling system.

To Kantè’s mind, his attempts to develop an appropriate way of writing his mother-tongue would help spread Islam and its proper practice. As such, he did not shy away from presenting it to the Quranic elite. Unfortunately, their reaction was the same as when they had reviewed his Ajami orthographies. Kantè (2004:5–6), in response, invoked the life and acts of the Prophet Muhammad:

For Kantè, this act of Muhammad was important evidence of the Islamic responsibility to spread literacy. To his mind, however, literacy should not be sought out in just any language. Working toward an Islamic conclusion about translation and mother-tongue education, Kantè (2004:6) called upon the holy book itself:

Of course, Islam for centuries has been relayed to West Africans through the Quranic schooling tradition as outlined above. To Kantè’s mind though, oral explanation to the masses was simply not sufficient. It would not necessarily generate that which was central to embracing Islam—understanding (Kántɛ Reference Kántɛ2004:6):

Kantè held that being a good Muslim requires understanding—something that he believed is most easily achieved through mother-tongue education—but true understanding requires text-mediated learning. Indeed, writing occupies much the same role in Kantè’s theory of communication which he lays out in Ń’ko Kángbɛ’ Kùnbába’ (Big Book of N’ko Grammar, Kántɛ Reference Kántɛ and Màmádi Jàanɛ2008c:3–4):

Combining this pedagogical perspective regarding mother-tongue education, his theory of the written word’s power and his conceptualization of the role of understanding in spreading Islam, Kantè (2004:6) came to the following conclusion

N’ko’s founder did not call for an end to Arabic literacy and proficiency (or that of French for that matter); for him, Arabic was undoubtedly the preferred language of Islam (Kántɛ Reference Kántɛ and Màmádi Jàanɛ2008b:4). Nonetheless, given that few African Muslims understand it, Kantè (2004:6) questioned how realistic it was to focus on Arabic acquisition instead of mother-tongue education:

This commentary about Arabic proficiency presupposes the voices of his interlocutors of the day: Madrasa reformers who were actively working to promote Arabic-language instruction as the best way forward for West African Muslims. By the 1950s, Manding Muslim society was polarized, and people had to take a stance vis-à-vis the reform movement (Kaba Reference Kaba1974:50). Kantè, like his fellow Muslims and Quranic teachers, hoped to strengthen and spread Islam; N’ko would contribute to that (Kántɛ Reference Kántɛ2004:1). That said, he explicitly distanced himself from certain voices within West African Islam:

Such remarks, placed alongside his own extensive writings on Manding history, customs, and Islam suggest Kantè’s N’ko was a direct intervention in the emergent “Islamic sphere” of West Africa and not simply a reaction to Marwa’s racism or colonial injustice. Kantè’s N’ko writings suggest goals similar to those undergirding the madrasa movement: unmediated access to God (Kántɛ 2007/1958:1) and Islam without the distortions introduced by man (Kántɛ Reference Kántɛ and Màmádi Jàanɛ2008b:4). Nonetheless, as the above and his many non-Islamic writings make clear, he also acted in response to the numerous reformist or “Wahhabi” voices that he undoubtedly encountered and likely viewed as committed to the further Arabization of West Africa (see allusions to this in Oyler Reference Osborn2005:40,73).

Clearly, Kantè’s intervention cannot be limited to the Islamic sphere. N’ko and the madrasa movement both used this medium of instruction as a means to simultaneously reform Quranic schooling and undermine French colonialism. If, among other things, the madrasa movement sought to use Arabic to re-insert West Africa into a global Islamic community, what did Kantè seek in promoting mother-tongue education for Manding speakers?

While clearly Islamic on one hand, his focus on mother-tongue orthography and standardization along with his writings on Manding history and culture link his concerns to other ethno-nationalist rumblings of the late colonial era on the other. In Guinea of the 1940s, prior to the rise of the pan-French West Africa party, the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain, “[t]he political arena was dominated by regional and ethnic associations promoting the interests of their particular constituencies: Peul, Malinke [viz. Manding], Susu, and the people of the forest region” (Schmidt Reference Sangaré2005:33). N’ko can be understood as an intellectual counterpart to the relevant ethnic association of Kantè’s home region of Upper Guinea, the Union du Mandé (d’Avignon Reference Dalby and Hodge2012:10). This is not to say that Kantè was commissioned by or working directly for that group; this sort of connection would have been difficult given that Kantè spent most of the 1940s in Côte d’Ivoire. Even following independence, Kantè never seems to have been directly involved with politics, whether in Guinea, Mali (1977–1982), or Côte d’Ivoire (1982–1984). Regardless of this lack of connections with political parties pre- or post-independence, his writings on Manding language, history, and traditions were certainly works that could “foster coherence and self-consciousness” (Cooper Reference Conrad2002:59) among Manding people as Dianne Oyler (Reference Osborn2005) and Christopher Wyrod (Reference Wilks, Levtzion and Pouwels2003) argue.

In sum, Kantè’s N’ko was an intellectual project that straddled two seemingly disparate worlds: that of Islam, and that of worldly political concerns pursued through ethno-nationalism or pan-Africanism. Kantè was not simply a cultural nationalist who happened to be a Quranic teacher, though. His actions and accomplishments were unique, but his goal of valorizing African and specifically Manding ways of being while also affirming equal status within the global Muslim community was not. This approach was long present in West African intellectual circles, as evident in the Ajami tradition reviewed in the previous section.

Conclusion

Kantè’s legacy lives on today through the grassroots publishing, broadcasting, and education efforts of thousands of his West African students. Together, they undoubtedly produce more printed text in a year than in all of the official State-backed Latin-based orthographies for Manding combined. From where does such support stem? We can usefully begin to respond to this question through the life and work of N’ko’s intellectual founding father as analyzed above.

First, the inventor of the N’ko script was firmly rooted within the “discursive tradition” of Islam (Asad Reference Amselle, Piga and Ventura1986). His writing system was unique, but his concern with using a local African language to better spread the religion was not. Following in the footsteps of Fulani, Hausa, Wolof, and Manding West African Muslims that arose starting at least two centuries before him, he believed that African languages had an integral role to play in disseminating Islam. While these languages and Manding had long been used orally to this end, Kantè, like Samba Mambeyaa, Usman Dan Fodio, Muusaa Ka, and Alfa Mahmud Kàbá saw the benefit of reading and writing in them. Indeed, for Kantè, literacy was not just essential to learning and logical thought but also an Islamic responsibility that could be traced back to God’s Messenger, Muhammad. Despite this sentiment and his Islamic scholarship, Kantè never claimed the mantle of a religious leader. From Kantè’s perspective as the inventor of N’ko, his contribution in the Islamic domain was primarily a pedagogical one.

Second, Kantè’s intervention spoke to his historical moment and the future he envisioned for society. Traveling and living directly amidst the reformist circles that were gaining steam in the Manding-speaking areas of Mali, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire, Kantè’s orthographic experimentations that culminated in the invention of N’ko in 1949 were his mother-tongue response to the madrasa movement’s championing of Arabic-medium education. In this sense, Kantè’s actions and his subsequent thirty-eight years of writing, research, and teaching were not only responses to Kamal Marwa and French colonialism, but to his Islamic sphere contemporaries. N’ko as his oeuvre, then, is also an important example of an Islamically-educated African doing the same intellectual work around ethnic solidarity that is often seen as emanating from “the first or second generation of western-educated people” (Cooper Reference Conrad2002:59), the implication being that such sympathies were in large part fanned by the Western institutions behind them: churches, colonial officers, and schools.

Kantè—and therefore the N’ko movement of today—must be understood as Islamic in addition to any readings of it as anti-colonial, pan-Africanist, or ethno-nationalist.

Acknowledgments

The writing and editing phase for this article were supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation (DFG) for the project “African voices in the Islamic manuscripts from Mali: documenting and exploring African languages written in Arabic script (Ajami)” (Project Number 344888349). In this regard, I thank my colleagues Dmitry Bondarev and Djibril Dramé.

ߒ ߠߊ߫ ߝߏ߬ߟߌ ߓߍ߫ ߒߞߏ߫ ߞߊߙߊ߲ߘߋ߲ ߓߍ߫ ߟߊߘߍ߬ߣߍ߲߫ ߦߋ߫، ߊߟߊ ߦߋ߫ ߒ ߠߊ߫ ߞߊ߲߬ߙߊ߲߬ߡߐ߮ ߟߎ߬ ߓߍ߫ ߛߘߊ߬، ߊߟߊ ߦߋ߫ ߒ ߠߊ߫ ߓߊ߯ߙߊ ߣߌ߲߬ ߞߍ߫ ߝߋ߲߫ ߣߝߊ߬ߡߊ߲ ߘߌ߫ ߊ߬ߟߎ߬ ߓߟߏ߫،