17.1 Introduction

This chapter examines campaigning: what it is, when it is needed and who conducts campaigns. Drawing upon examples from the NGO conservation sector, we discuss how to plan and execute a campaign, and explore the different types of campaign: behaviour change, policy change and fundraising. Finally, we consider some of the potential pitfalls, including a lack of a strong evidence base, overstating claims of success, the introduction of bias, conflicting views of co-organising partners, the inappropriate use of emotion and the risk of unintended consequences.

17.2 What is campaigning?

Campaigning, also described as influencing or advocacy, is about creating a change. Whether the aim is to reduce trade in the horn of a threatened species of rhino, protect the habitat of a rare population of wild orchids, raise funds for a workshop or the ongoing costs of species monitoring, or change the law on the import of hunting trophies into a country, conservation NGOs campaign to create change. The desired change may be to address the root cause of a conservation problem, such as demand-reduction or behaviour-change campaigns, or the campaign may be focused only on mitigating the effects of a problem, as in the case of grants to improve law enforcement activities that prosecute wildlife traffickers. Some organisations may decide to focus on campaigning to tackle both the cause and the effect.

17.3 When is campaigning appropriate?

Campaigning can be appropriate in a diverse range of situations: from local to global issues, from high-profile to emerging conservation problems, from long-term to opportunist responses. While campaigning is often on high-profile and well-known conservation problems, it may also be used to mobilise or harness existing public support for less well-known or emerging issues, or to tackle issues with impacts at a global scale.

In a recent opportunistic, but highly effective example, several NGOs launched campaigns to urge the public and policy-makers to phase out single-use plastics after the high-profile BBC documentary Blue Planet II, screened in the UK in December 2017, highlighted the problem of plastic pollution in the world’s oceans. The programme showed footage of a pilot whale cow carrying her dead calf for days, with the calf’s death linked to the possibility of its mother’s milk being poisoned with toxins accumulated through the food she had been eating. The combined messaging gained considerable public attention, and in April 2018 the UK Government launched a consultation to explore the possibilities of banning plastic straws and other single-use plastics. While this consultation follows on from other action to reduce plastic usage that took place before these campaigns, such as the introduction of charges for plastic bags in 2015, increased public pressure likely highlighted the issue as a priority at this time. Indeed, the then Environment Secretary Michael Gove reportedly stated that he had been moved by the BBC programme (Rawlinson, Reference Rawlinson2017). In addition, several large companies responded to pressure from consumers by pledging to reduce or phase out single-use plastics.

Campaigning can also be used to give a voice to those without one. NGOs focusing on humanitarian relief or disadvantaged groups of people will often tell the story of a single person as a microcosm of the wider issue. Conservation causes, whether endangered species or ecosystems, are not able to speak for themselves, and NGOs often use ‘ambassador’ animals, such as Sudan, the last male Northern white rhino (euthanised in March 2018 after experiencing an increasing number of age-related problems), which came to embody the long, sorry history of the doomed attempts to conserve the species. Sudan became the focus of numerous fundraising campaigns to generate income for assisted reproduction technologies to try to ‘recreate’ the subspecies.

Finally, campaigning is sometimes the only action possible, especially when the scale of the problem is large or cannot be addressed without state or international intervention (such as plastics in the ocean). One successful example took place in 2002, when campaigning by Project Seahorse played a central role in the listing of all seahorse species on Appendix II of the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), meaning that international seahorse trade was regulated and monitored for the first time (Project Seahorse, 2018). Through policy recommendations informed by scientific research, Project Seahorse highlighted the huge scale of trade in seahorses and the threat to wild species that unregulated and unsustainable trade was posing. With up to 20 million seahorses traded annually, this listing represented an important step towards sustainability of this trade.

17.4 Who campaigns?

Campaigns can be created and delivered by individuals, groups or organisations, whether commercial or charitable. NGOs are particularly associated with campaigning; their fundamental objective is to make the world a better place, and they have members who feel strongly about the issue in hand. NGOs are often very close to their service users and beneficiaries, and can therefore use evidence from their direct experience to highlight changes needed, whether to attitudes, legislation or budgets. The examples in this chapter are drawn from the conservation NGO sector.

A common cause can bring together disparate voices to create a collective campaign that is louder, more wide-reaching and more effective than could be achieved by any single organisation. The campaign to create a marine reserve around the Pitcairn Islands began in 2011, when the Pew Environment Group’s Global Ocean Legacy project first discussed with Pitcairn islanders the idea of establishing a large-scale marine reserve within their waters. A number of organisations and celebrities then became involved in the campaign, including the Great British Oceans Coalition, National Geographic, the Zoological Society of London, Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, Gillian Anderson, Julie Christie and Helena Bonham-Carter; the Pitcairn Island Marine Reserve was eventually legally designated in September 2016.

17.5 Planning a campaign

A well-designed campaign cycle will begin by analysing and selecting the issue, followed by developing the strategy, planning the campaign, delivering it, monitoring progress, evaluating impact and drawing out learning. More complex campaigns may research and develop different strategies and pilot them before conducting monitoring and evaluation on the different groups to determine the most effective strategy. They may begin by establishing an evidence base, developing a theory of change, and embedding within that the system of monitoring and evaluation, to include targets, indicators and means of verification.

Campaigns usually employ a call to action, which will differ depending on the target audience and the chosen goal. Such calls to action need to consider their target audiences. For example, a campaign to conserve water in Europe and the USA may ask people to turn off the tap while brushing their teeth, whereas a water conservation campaign in sub-Saharan Africa may ask farmers to introduce night-time drip irrigation for their crops to minimise evaporation.

If there is no budget previously set aside for the campaign, then funds need to be raised. Communications staff need to work on how to articulate the campaign’s concepts and frame the debate. Finally, the organisation needs to be ready to implement the change, perhaps in partnership with others, with all the resources required, and to be able to manage that implementation without detracting from its ongoing work.

17.6 Types of campaigns

Campaigns generally fall into three categories: bringing about behaviour change, bringing about policy change, or raising funds. We consider each of these in turn and, for each category, we give an example of a successful campaign, seeking to highlight the aspects that, in our view, contributed to that success.

17.6.1 Campaigning to change behaviour

Many campaigns aim to change human behaviour, to reduce the incidence of behaviour that is in some way harmful to wildlife or ecosystems, or promote positive behaviour. Changing behaviour is different to raising awareness of an issue, which involves simply communicating the nature of a threat or conservation problem in the hope that the public or policy-makers will take action. Increasingly, the effectiveness of raising awareness in changing a person’s behaviour is being questioned (Christiano & Neimand, Reference Christiano and Neimand2017).

Greenpeace’s palm oil campaign of 2010 (Greenpeace, 2010) targeted both the people buying Kit Kats and Nestlé, the manufacturer. A one-minute video shows a bored office worker shredding documents while watching the clock until 11:00 and his break. He tears open the wrapper of a Kit Kat. We, the viewer, see that the wafer finger is actually an orangutan’s finger, complete with furry knuckle and nail. The chocolate bar drips into his keyboard; oblivious, he wipes his mouth and spreads a smear of blood. The video ends with a call to ‘Stop Nestlé buying palm oil from companies that destroy the rainforests’. A link to Greenpeace’s website, with suggestions for how concerned viewers could take action, was provided. Greenpeace reported 1.5 million views of the advert, more than 200,000 emails and phone calls to Nestlé HQ and countless comments posted on Facebook. This, combined with protests at Nestlé AGM and its headquarters all over the world, and meetings between Greenpeace campaigners and Nestlé executives, resulted in swift action. Nestlé developed a plan to identify and remove any companies in their supply chain with links to deforestation so their products would have ‘no deforestation footprint’, although it has been reported that they have since backtracked on these commitments (Neslen, Reference Neslen2017).

In a contrasting example, campaigns to increase consumer awareness of the impact of their purchases on overfishing, including labels for certified sustainable products, have been found to have little effect on purchasing choice or consumer demand (Jacquet & Pauly, Reference Jacquet and Pauly2007). Therefore, it is essential that behaviour-change campaigns go beyond simple awareness-raising and base their messages on sound research into when, where, how, why and by whom the behaviour is occurring.

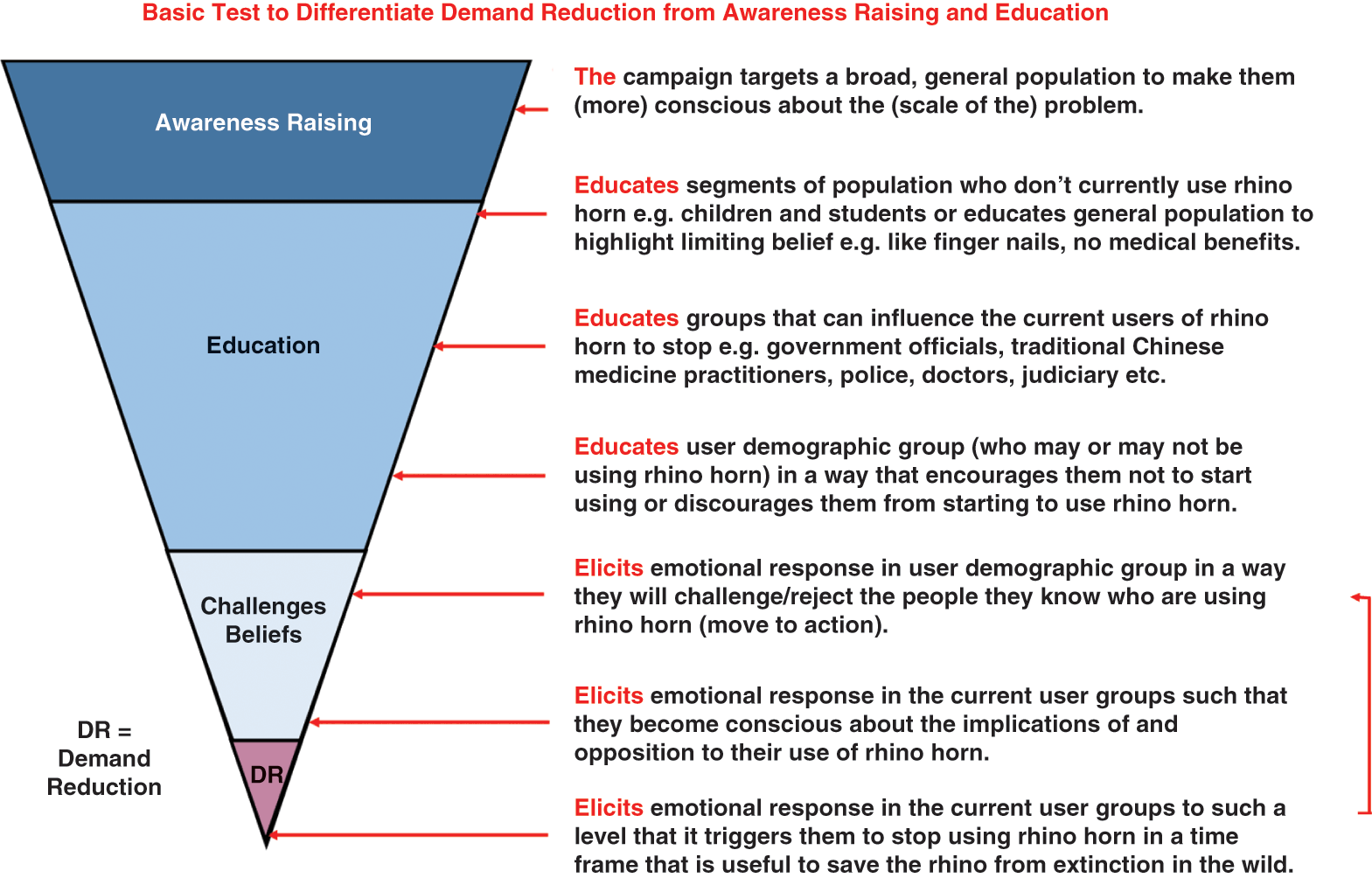

Lynn Johnson has developed a useful pyramid (Figure 17.1) to show the difference between behaviour-change and awareness-raising campaigns. However, the majority of so-called behaviour-change campaigns actually operate at the awareness-raising level, rather than that at the demand-reduction level. Programme managers dealing with the direct consequences of poaching understandably must feel frustrated when they see substantial funds being invested in ineffective efforts to change consumer behaviour in the main consumer countries for illegal wildlife products.

Figure 17.1 Model showing differences between behaviour-change and awareness-raising campaigns developed by Nature Needs More Ltd for its Breaking The Brand RhiNo Campaign.

Doug Mackenzie-Mohr (Reference Mackenzie-Mohr2011) has written extensively about fostering sustainable behaviours and has broken down the steps involved. The process starts by identifying which behaviour you want to change and in whom, while also considering when and where they exhibit this behaviour. The next step involves identifying what might be stopping people from changing behaviour, and what the incentives might be for doing so. This allows informed strategies to be developed that consider the design of the messaging but also other factors, such as how social norms can be used to reinforce the desired behaviour. These strategies should then be fully tested in a pilot phase before full-scale implementation, with monitoring and evaluation throughout.

Although behaviour-change campaigns focused on illegal products often suffer from a lack of available data on consumers, there are examples of targeted campaigns that have carefully planned their messages based on evidence. In 2014, TRAFFIC in Vietnam launched the Chi campaign, a behaviour-change campaign based on consumer research into the groups most likely to buy illegal rhino horn. This research established that the key driver for the consumption of rhino horn was its ‘emotional’ value rather than its ‘functional’ (i.e. medicinal) value and that the main users were wealthy businessmen aged between 35 and 50 living in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City (TRAFFIC, 2013). They valued the strength and power of the animal that had been killed to obtain it, but also the scarcity and high cost of rhino horn and the difficulty of obtaining it; being able to do so demonstrated the extent of the buyer’s networks. Having segmented the consumer market, and with the information on the motivations of the prime target audience and the drivers of consumption, there was little point in launching a campaign that relied on photographs of traumatically dehorned rhinos, or on debunking beliefs that rhino horn could cleanse the body of toxins following chemotherapy. Instead, the campaign focused solely on the importance of ‘Chi’, an inner power and strength that negated the need for rhino horn. While it is too early to evaluate the success of this campaign, it is a good example of the careful designing and tailoring of messages to a specific situation that should be employed in campaigns of this type. Audience segmentation is a commonly used approach of subdividing populations into groups with shared characteristics, such as socio-demographic, behavioural or psychographic profiles (Wedel & Kamakura, 2000).

17.6.2 Campaigning to bring about policy change

When it comes to bringing about a change in policy, NGOs usually try to both influence and inform the target audience, who may be legislators or Members of Parliament. They may employ methods that include media campaigns, public speaking, commissioning and publishing research, online petitions (change.org and avaaz.org are two of the most popular English-language online petition websites), organising protest marches or demonstrations, recruiting advice from experts, or making direct approaches to legislators or Members of Parliament on the issue concerned.

In 2017, a group called Two Million Tusks was concerned about the plight of African elephants and the UK’s role in the global ivory trade. They researched the quantity of ivory being sold through UK auction houses and whether those auctioneers were compliant with the UK’s rules on ivory trade. The resulting report, published in October 2017, exposed weaknesses in auction houses’ compliance and called upon the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs to ban all trade in ivory within the UK (Two Million Tusks, 2017). While the debate about ivory sales has been long-fought, a linked television programme, presented by Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, revealed new concerns. He arranged for eight ivory items on sale in UK antiques shops to be radiocarbon-dated, and found that three of the pieces were from modern, i.e. post-1947, ivory, and as such could not be legally sold in the UK. During a televised press briefing on this finding, the then Environment Minister, Andrea Leadsom, came under sustained pressure to address the UK’s role in laundering ivory from poached African elephants; the eventual result was a Bill to restrict severely the conditions under which ivory can be sold in the UK.

17.6.3 Campaigning to raise funds

Fundraising wisdom says that the most effective calls for donations are ones that engage the audience(s) on an emotional level (Hill, Reference Hill2010). Handling such messaging can be challenging: whether to use images that provoke negative (horror, disgust) or positive (empathy, inspired) emotions; whether to hold donors to ransom (‘Unless we act now, this species will go extinct’) or focus on success stories; whether to focus on a single, named animal as an ambassador for its species, while being clear that donations will be spent on a wide range of activities, or on a species or habitat as a whole.

In the UK, the Fundraising Regulator, formerly known as the Fundraising Standards Board, sets and maintains the standards for charitable fundraising in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and aims to ensure that fundraising is respectful, open, honest and accountable to the public, and regulates fundraising practice via The Code of Fundraising Practice (Fundraising Regulator, 2016). Its guidance on ‘Content of Fundraising Communications’ says that organisations: must not imply that donations will be used for a specific purpose if they will be allocated to general funds; must be legal, decent, honest and truthful; must make it clear if they alter any elements of real-life case studies; and must give warnings about and be able to justify the use of any shocking images.

In October 2014, Save the Rhino International (SRI) began planning its annual fundraising appeal for 2015. The decision was made to focus on Kenya, which had not benefited from previous appeals and which had suffered a spike in rhino poaching in 2013, when 59 rhinos were killed, as compared to 29 the previous year. SRI had a long history of supporting rhino conservation efforts with its in-country partners. It was suggested that a focus on the canine units employed by Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, Borana Conservancy, Ol Jogi Conservancy and Ol Pejeta Conservancy, as part of their anti-poaching and community engagement strategies, would provide an interesting and engaging angle for a public fundraising appeal. These units use Belgian Malinois and bloodhounds for tracking (i.e. following poachers’ scent trails) and/or detection (i.e. dogs are trained on specific scents to be able to carry out, for example, vehicle searches at road blocks). A name for the appeal, ‘Rhino Dog Squad’, was chosen as being descriptive, punchy and memorable.

Based on results from previous appeals, SRI’s primary objective for the appeal was to raise a total £40,000 for the three canine units in Kenya by February 2016, of which £30,000 would come from a campaign marketed to the general public and £10,000 from zoos via spin-off campaigns.

Three distinct target audiences were identified: the general public/animal lovers, particularly those with pet dogs, living in the UK, continental Europe or the USA, across a broad age range, with some but not detailed knowledge of the rhino poaching crisis; high–net-worth individuals who have visited or have links with Kenya; and zoo visitors. Save the Rhino applied successfully to BBC Radio 4 to have the Rhino Dog Squad featured as one of the station’s charity appeals: this greatly increased the charity’s ‘reach’ to the first audience.

SRI’s appeal planning team realised early on that the choice of presenter would influence the script, and considered the merits of having a celebrity record the appeal versus one of the Kenyan field programme staff. In the event, SRI recruited Sam Taylor, Chief Conservation Officer at Borana, to read the script, giving SRI an opportunity to personalise the script. Furthermore, knowing that the appeal would be broadcast just before Christmas 2015 (twice on the last Sunday before Christmas and once on Christmas Eve) meant that the SRI team had to consider where radio listeners would be, and how to engage their emotions at such a time.

The BBC Radio 4 appeal alone raised more than £22,000, with the Rhino Dog Squad in total realising about £60,000 by 31 March 2016; some donors set up standing orders and funds are still being received for the canine units at the time of writing (June 2018). The BBC said that the appeal was one of the most successful of its type, and attributed this to:

a knowledgeable presenter: having someone who worked at one of the beneficiary conservancies read the appeal meant that it could be written in a way that was highly personal and credible;

an unusual script: the first words of the appeal were ‘Sausage bonus! Now there’s an image to conjure with. I’m guessing you don’t often see the words “Sausage bonus” in a budget. I do, in my work as Conservation Officer in a wildlife sanctuary in northern Kenya’. The first two words caught and held the attention, as Sam went on to explain how the canine units help the rangers with their work;

making the most of the timing: SRI knew that listeners would likely be at home with their families, wrapping presents, decorating the tree or beginning to cook Christmas meals. Contrasting listeners’ lives at Christmas with that of the rangers in Africa would be powerful. ‘This Christmas, as you enjoy time with your families, friends and your pets, please remember our dogs and rangers. They’ll be at work, protecting Africa’s wildlife. Please help the Rhino Dog Squad’;

the famous British love of dogs: ‘We use bloodhounds and Belgian Malinois, and they’re awesome. They can track scent for up to three days. They’re better than a bullet – they can go around trees and hold poachers until our rangers can safely make an arrest. The dogs work at roadblocks, detecting rhino horn, ivory, and weapons. We also use them to help find lost children or recover stolen property. Our dogs are part of our team’;

the wider appeal held by SRI: in addition to the BBC 4 appeal, SRI had planned a strong social media campaign with many assets: ezines, blogs written in advance ready to be posted, lots of high-quality images (including photographs taken during a visit in March of dogs tearing into parcels wrapped in Christmas paper containing bones and toys), and a main 4-minute film supported by four supplementary 2-minute films.

17.7 Potential pitfalls for campaigns

17.7.1 Lack of a strong evidence base

While reports of incredible successes offer good news stories for conservation and boost the reputation of the organisations that carry out the campaign, there is the risk that once the evidence base (where it exists) is questioned, the outcomes turn out to be not quite the success story that they initially appeared. Although in the majority of cases this may just lead to wasted donor funds and NGO time, there are also examples of where this has created a conservation problem in itself.

A good example is the ‘Save the Bay, Eat a Ray’ campaign that followed all of the rules for a good campaign. It used clear messaging to communicate a simple evidence-based action that members of the public could take to help restore Chesapeake Bay: eating more cownose rays (Rhinoptera bonasus) (National Aquarium Baltimore, 2016). The evidence said that a huge population increase of cownose rays was decimating the Bay’s oyster populations, and some also claimed that the species was invasive. However, further analysis of the science found that the models used were flawed and, not only was the ray a native species that was not responsible for the decline, it was itself extremely vulnerable to overfishing (Grubbs et al., Reference Grubbs, Carlson and Romine2016; National Aquarium Baltimore, 2016). In this case, a lack of robust scientific evidence relating to the ecology of the system led to negative conservation consequences, even if these outcomes were intended in the first place.

Behaviour-change campaigns can become particularly complex when they are based around reducing the use of illegal wildlife trade products. Communicating messages to the consumers of an illegal product is difficult because, if admitting to using the product could result in some kind of punishment, even identifying the consumers of it will be a challenge (see Chapter 5 for a discussion of approaches to gathering information about sensitive topics, including illegal resource use). Often, in-depth research focusing on consumer preferences and behaviour is needed to understand motivations for consumption (e.g. Nuno & St John, Reference Nuno and St John2015; Hinsley et al., Reference Hinsley, Verissimo and Roberts2015). However, behaviour-change campaigns are often carried out by NGOs without the time, expertise, resources or capacity to do this kind academic research. This has resulted in several campaigns based on very little knowledge of who the target audience should be, often using high-profile celebrities or eye-catching graphics to get the message out to as many people as possible, with the hope that this will include the actual consumers of the product. Unfortunately, it is not possible to say whether this works: a recent review found that almost no behaviour-change campaigns focused on wildlife consumers report evidence of impact, and very few carry out any kind of robust evaluation at all (Veríssimo & Wan, Reference Veríssimo and Wan2018). One way to address this could be greater collaboration between NGOs that do not have in-house scientists and academics, to ensure that campaigns are based on good scientific evidence, and that results are analysed in depth to evaluate the impact.

17.7.2 Over-stated claims of success

Some NGOs have focused their behaviour-change campaigns at children, banking on the ‘pester-power’ factor (cf. Figure 17.1, activity that ‘Educates segments of the population who don’t currently use rhino horn, e.g. children’). Humane Society International, for example, launched a campaign aimed at stopping the use of illegal rhino horn in Vietnam via a book called I’m a little Rhino that was used in schools to help teach children about rhino poaching concerns and conservation efforts. No information is available on how the campaign was designed, targeted or evaluated, but claims that demand for rhino horn had fallen by 77% in Hanoi following the campaign have been heavily criticised by conservation practitioners (Roberton, Reference Roberton2014).

17.7.3 Bias in campaigns

One of the dangers of advocacy/campaigning is that it may not be sufficiently inclusive or consultative. For example, the NGO leading the campaign may have a particular stance on a controversial issue, or an NGO with a direct line to a Member of Parliament or Minister may be able to exert undue influence.

For example, IFAW, Lion Aid and the Born Free Foundation, among others, have worked closely with a group called ‘MEPs for Wildlife’ (MEPs are Members of the European Parliament). While there was an initial focus on banning the hunting of canned lions (canned hunts are trophy hunts in which an animal is kept in a confined area, such as in a fenced-in area, increasing the likelihood of the hunter obtaining a kill), MEPs for Wildlife expanded its efforts to call for an EU-wide ban on the import of lion trophies, in keeping with decisions made by the Netherlands, French and Australian governments.

However, as an IUCN Briefing Paper for European decision-makers explains (with reference to the then recent and still notorious case of ‘Cecil the Lion’, shot in July 2015):

Intense scrutiny of hunting due to these bad examples has been associated with many confusions (and sometimes misinformation) about the nature of hunting, including:

None of these statements is correct. (IUCN, 2016)

The Briefing Paper goes on to conclude that ‘legal, well-regulated trophy hunting programmes can – and do – play an important role in delivering benefits for both wildlife conservation and for the livelihoods and wellbeing of indigenous and local communities living with wildlife’ (IUCN, 2016).

Making the case for positions, particularly ‘unpopular’ ones such as advocating for well-run trophy hunting, is extremely difficult to do. The IUCN Briefing Paper includes two graphs on rhinos and trophy hunting: the first showing the change in estimated numbers of Southern white rhino in South Africa before and after limited trophy hunting was introduced in 1968; and the second showing growth in estimated total numbers of black rhino in South Africa and Namibia before and after CITES approval of limited hunting quotas (a maximum of five animals per country per year, and even then only if suitable candidate animals can be identified) in 2004. Both graphs show populations increasing exponentially until the current poaching crisis began (IUCN, 2016).

Numerically speaking, the evidence in the Briefing Paper is conclusive: trophy hunting of rhinos, while fatal for the individuals concerned, has not adversely affected the species’ meta-population growth. Simultaneously, it has generated incentives for landowners (government, private individuals or communities) to conserve or restore rhinos on their land; and generated revenue for wildlife management and conservation, including anti-poaching activities. This does not hold sway, however, with NGOs that are ideologically opposed to trophy hunting.

17.7.4 Conflicting views

It would be wrong to assume that all conservation NGOs speak with a common voice. The Global March for Elephants and Rhinos (GMFER) has become a worldwide campaign, taking place in more than 160 cities in 2016, and thus enabling people from many different countries to take part. In the beginning, the march was about ‘raising awareness, generating global media attention on the crisis, and keeping political pressure on world leaders to protect our endangered wildlife’. Such broad aims made it possible for a broad church of elephant- and rhino-focused conservation organisations to take part in the march.

However, in more recent years, the GMFER has focused on banning trade in ivory and rhino horn, including applying pressure on South Africa to maintain a ban on domestic rhino horn trade (the ban was eventually overturned in early 2017) and on Japan and Hong Kong to ban online and domestic sales of ivory. A number of NGOs that are working to tackle the rhino and elephant poaching crises are actually pro-sustainable use, and have taken the decision not to participate in GMFER’s annual event, because its aims were incompatible with their own.

17.7.5 Inappropriate use of emotion

Conservation or animal welfare/animal rights NGOs must tread a fine line when campaigning about emotive subjects. Some of the most difficult images to view are those showing animal abuse or suffering, bushmeat and the impact of poaching. A photograph that is too upsetting will result in the viewer turning the page quickly without taking in the call to action.

There are ways around this challenge. Photographs of dead elephants with their tusks hacked out certainly tell the story behind the poaching crisis, but so too does Nick Brandt’s monochrome image, Line of rangers holding tusks killed at the hands of man, Amboseli 2011. As the photographer writes (Brandt, Reference Brandt2015),

I wish that I had never had to take this photo. I wish that it had never been possible to take this photo. The photo was taken as a deliberate visual echo of Elephants Walking Through Grass, a very different world – a vision of paradise and plenty – taken only a couple of miles away three years earlier. But instead of a herd of elephants striding across the grassy plains of Africa, we see only their remains: the tusks of 22 elephants killed at the hands of man within the Amboseli/Tsavo Ecosystem.

Brandt’s post goes on to hold out hope in the form of the work being done by Big Life Foundation’s rangers; a good example of a strong image, which does not in itself provoke feelings of disgust or revolt in the viewer (Fundraising Regulator, 2016), but which explains the catastrophe that has occurred and offers a way of helping to solve the problem.

17.7.6 Risk of unintended consequences

Ensuring that communications are well-designed and that the campaign’s main messages are evidence-based can make achieving the ultimate aim more likely, but it does not always protect against unintended, often negative, consequences of the campaign.

To date in conservation there has not been enough robust evaluation of campaigns to measure the occurrence of unintended consequences, but evidence from other fields demonstrates the risk. In the field of health, the risk of unintended consequences is well-recognised. For example, multiple studies have found that campaigns aimed at reducing drug and alcohol consumption frequently create so-called ‘boomerang effects’, where the result is an increase in consumption rather than a decrease (Ringold, Reference Ringold2002). This extent to which this phenomenon may be occurring in response to demand-reduction campaigns for high-profile wildlife products is unknown, but the complexity of these markets and the use of conflicting messages by different groups may increase the risk. For example, the legal bear bile trade in China has been the focus of extensive campaigns by animal welfare organisations, with the ultimate aim of closing down all bear farms. While some campaigns use the ineffectiveness of bear bile as a medicine as the key message, others instead focus on the cruelty of the farms, or the health risks to consumers of using farmed bile, such as the 2012 Healing without Harm campaign (Watts, Reference Watts2012). While these messages may be intended to close down the market for bear bile, and with it the farms themselves, little is known about how regular consumers of bile – who believe that it is an effective treatment for a serious condition, such as liver cirrhosis – will react. For example, will these consumers switch to wild-sourced bear bile instead where it is available, or will they start using another product? Currently there is little evidence either way, making this a risky strategy for conservation. To mitigate this, campaigns should fully consider all potential consequences of their messaging and evaluate the risks of carrying out the campaign before it starts, drawing on existing evidence from other fields.

Another problem area lies in the way that illegal wildlife trade products are described by some NGOs, which is then repeated in the media. Products such as orchids, pangolin scales and rhino horns are often described as rare and hard to obtain by well-meaning organisations or researchers. However, in markets that often prize rarity, such messages can increase consumers’ desire for the forbidden item, the acquisition of which will demonstrate both their wealth and their ability to use their networks to obtain it. For example, specialist consumers of slipper orchids, all species which are on CITES Appendix I, have been found to be willing to pay more for a rare species (Hinsley et al., Reference Hinsley, Verissimo and Roberts2015). Although several of these species have already been collected to near extinction for trade (e.g. Paphiopedilum canhii: Rankou & Averyanov, Reference Rankou and Averyanov2015), highlighting their rarity is likely to be counter-productive. Similarly, mentioning high prices for wildlife products can raise awareness of their value among both consumers and traders, and organisations like TRAFFIC and Wildlife Conservation Society have drawn up clear internal guidelines for their staff, explaining why they should never discuss the black-market price of an illegal wildlife product.

17.8 Future directions for campaigns in conservation

Campaigning to bring about change is central to much of conservation action, and it is essential that the importance of a well-designed campaign is recognised and appreciated. There are numerous examples of campaigns that have brought about change, many that did not achieve their intended goals, and even more that have never been carefully evaluated. As described in this chapter, the most successful campaigns will undertake careful planning and tailor their messages to the specific aim and context to ensure that they engage the target audience effectively. Other important steps include clear goal-setting, development of indicators and means of verification; monitoring, and a comprehensive evaluation of outcomes.

Competition for donor funds or the support of the public can sometimes mean that collaboration and open dialogue between different conservation actors is not always a priority. However, partnerships between different NGOs can extend the reach of a campaign and provide new perspectives, and collaboration with academics can provide a strong scientific research base for its design. Possibly the most important action should be to share lessons learned from successes and failures, as this is an important way that campaigns can continue to improve and avoid the pitfalls described here. These steps are essential, as a good campaign cannot only prevent the waste of donor funds, but increase the likelihood of conservation delivering change for the common good.