INTRODUCTION

In 1872, Russian authorities in the Caucasus received a petition from a Muslim Kurdish family in Novobayazetsky Uezd, a district around Lake Sevan in modern-day Armenia. Four brothers, Mgo, Avdo, Alo, and Fero, and their mother Gapeh requested the government to allow them to leave Islam and convert to the Armenian Apostolic faith.Footnote 1 They added testimonies of their fellow Armenian neighbors, who confirmed that these Kurdish residents of the snowy highlands in the south of the Russian Empire were genuine in their desire to accept Christianity. Russian officials in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, Georgia), the capital of the Caucasus Viceroyalty, were perplexed but not surprised by such a request. In the late tsarist era, hundreds of individuals and families living in the South Caucasus asked to change their faith. Many of them were Muslims, most of whom opted to become Armenian.

Religious conversions in the greater Caucasus region and the Middle East, particularly those involving Armenians, evoke images of violence. In the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire, thousands of Armenian Christians became Muslims, primarily in order to escape death, during the Hamidian massacres in the 1890s and the Armenian Genocide in the 1910s.Footnote 2 In contrast, this article examines the phenomenon of voluntary conversions to Armenian Christianity that had been occurring in the same time period in Russia's South Caucasus provinces, which bordered the Ottoman Empire and Iran. These conversions stand out for a couple of reasons. Although conversions of Muslims to other faiths were hardly uncommon in Russian, Middle Eastern, and Eurasian histories, the increasing incidents of sectarian violence and rigid interfaith boundaries make conversions out of Islam unusual in the age of European imperial expansion and colonialism. Likewise, conversions to the Armenian faith had been rare. The Armenian Church was not known for proselytism among non-Armenians, nor could Armenian priests, or any non-Orthodox clergy, legally proselytize in the Russian Empire.

This article explores conversions to Armenian Christianity, primarily to the Armenian Apostolic Church but also to the Armenian Catholic Church, in the Russian provinces (guberniia) of Tiflis, Erivan, Elisabethpol, and Baku, or territories of modern-day eastern Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, between the mid-nineteenth century and the outbreak of World War I. By investigating what motivated many South Caucasian residents to become Armenian, it probes political and economic developments that fostered a favorable climate for religious conversion. I argue that for rural and nomadic populations in the South Caucasus, a government-sanctioned act of conversion was often a means to acquire a new legal identity that could result in social and economic benefits in the aftermath of tsarist reforms in the region. Similarly, in the early twentieth century, Russia's Jews turned to the Armenian Apostolic Church to secure a new legal identity that would shield them from discrimination and bestow equal rights. Moreover, the South Caucasus, under Russian rule, emerged as a regional destination for conversion to Armenian Christianity by Ottoman and Iranian subjects. I reconstruct this history of such conversions by examining potential converts’ petitions, as well as accompanying reports of Russian civil and Armenian ecclesiastical authorities, preserved in archives in Tbilisi, Yerevan, Baku, Moscow, and Saint Petersburg.

Religious conversions in the South Caucasus draw on a long history of conversions in the early modern Russian and Ottoman states. Prior to the eighteenth century, the Russian government either forcibly baptized, or offered strong incentives to convert for, non-Orthodox communities in its newly gained territories: from the former Muslim khanates on the Volga, to the Buddhist-Muslim nomadic steppe, to the animist expanse of Siberia. Becoming Orthodox was intricately tied to being a Russian subject, and Christian proselytism and settler colonialism drove the expansion of the Russian Empire.Footnote 3 In Ottoman history, the drive into the Balkans and Anatolia was also accompanied by mass conversions of Christian communities into Islam, yet Islamization was never an official Ottoman policy.Footnote 4 Ottoman historians have demonstrated that conversions to Islam were motivated by many factors, including proselytizing zeal of early conquests, opportunities for social advancement, policies of individual sultans and courtiers, and the transformation of sacred space.Footnote 5 This article differs by examining rare conversions that were not a “medium of dominance,” since converts did not choose a favored imperial religion like Russia's Orthodoxy or Ottoman Islam, but rather a regional faith.Footnote 6 Nor did most of those converts revert to their old beliefs, like Russia's Krashen Tatars or Ottoman “crypto-Christians”; they embraced an entirely new faith.Footnote 7 Yet conversions to Armenian Christianity in the South Caucasus were also a byproduct of imperial expansion. I suggest that Russia's transformation of the region's political economy and legal codes prompted some new Russian subjects to become Armenian.

Religious conversions into Armenian Christianity bring into focus the imperial regulation of faith in the nineteenth century. The Russian government served as a final arbiter of conversions by affirming or denying every individual request to convert. I argue that this tight regulation of conversions allowed the state to reinforce legal inequality between Orthodox Christians and other Russian subjects and, later, between Jews and others.

The Russian approach to conversions into the Armenian faith in the South Caucasus bears similarities to the Ottoman stance on the conversions of Armenians into Islam in late nineteenth-century Anatolia. Both the Russian and Ottoman governments employed the notion of sincerity of one's religious transformation to question the legitimacy of conversions. The Ottomans, recognizing that the impetus for mass conversions into Islam was violence waged against Armenians, refused to accept conversions of entire communities lest those be seen as forced rather than voluntary, and trigger intervention by Britain, France, and Russia in the name of religious freedom.Footnote 8 The Russians acknowledged that many petitioners were motivated by material benefits and a desire to escape discrimination and denied conversion requests in order to preserve old religious and social hierarchies. In both cases, by favoring individual over mass conversions and by stressing bona fide religious transformation, the late imperial government bolstered individual belief over communal religious affiliation as a basis of one's religious identity, a hallmark of a modern state.Footnote 9

Individual petitions to convert, numbering in the hundreds and arriving from various corners of the South Caucasus, hardly threatened the religious status quo and may seem of limited demographic significance. Yet, when viewed collectively, they challenged, first, the dominance of the Orthodox Church, which was the state's favored destination for new souls and tithe-payers; second, the emerging Russo-Ottoman sectarian order, which held religious identity as immutable and correlative with political loyalty; and third, burgeoning national ideologies in the South Caucasus, wherein one's faith, language, and ethnicity largely coalesced.

CONVERSIONS INTO ARMENIAN CHRISTIANITY

In 1872, a Muslim man named Makhmat Gasan Akhmadov Shakhnaz oğlu asked the Russian authorities for official permission to convert to the Armenian Apostolic faith. He wrote: “Three years ago, by divine grace, I had a heartfelt desire to accept the saving faith of Christ in the rite of the Armenian Gregorian Church. I then left my wife, son, and daughter in Shemakha [now Şamaxı, Azerbaijan] and moved to the village of Giulatan, where I learned Armenian, kept all Christian fasts, went to church daily, and then entered the monastery of St. Jacob … where I wish to spend the rest of my life among monks because I no longer need the world and its earthly troubles.”Footnote 10 Makhmat Gasan was illiterate, and a fellow Armenian resident signed the petition in his place. In a separate communal statement, Armenian residents of the village of Giulatan, in Karabakh, confirmed that Makhmat Gasan was Muslim by birth, had recently moved into their village, lived among them for two years, and followed all tenets of their faith zealously.Footnote 11 Makhmat Gasan's petition attributes his desire to become a Christian to a sudden spiritual awakening, a narrative known in the history of Christianity as the Pauline model of conversion. This sentiment, however, had been rare in petitions from the South Caucasus.

Most South Caucasian converts had a long history of interaction with Armenians and claimed to have arrived at their decision to convert after living among Armenians for years. A more typical conversion request would be that by Güllizar Gado kızı, a Muslim woman residing in the village of Kulidzhan near Aleksandropol (now Gyumri, Armenia). In 1904, she wrote, “Growing up among Armenian people, I gradually realized that the Armenian Apostolic Church is the one true and faithful church.” As she wished to marry a young Armenian man from her village, she made the decision to formally convert to Christianity. Güllizar's petition had the support of forty-nine neighbors and a local Armenian priest, who had testified that she was born in a nearby, predominantly Armenian village and had been living in their village for the past eight years.Footnote 12

The petitioners typically demonstrated long-standing ties to the community that they sought to join. In 1868, a Kurdish Muslim man, Guso Kelesh oğlu, petitioned to convert to the Armenian Catholic faith. The authorities noted in his file that, since his early days, Guso had served as a shepherd in different Armenian Catholic villages.Footnote 13 Guso's acculturation into an Armenian environment was all but complete. For him to be socially accepted as an Armenian, he needed to go through the final step, that of baptism. A young Yazidi woman, Amal Safo kızı, who lived near Echmiadzin, wrote that she “was around Armenian people from the day of her birth and was familiar with their life and their church dogmas,” which eased her decision to join the Armenian Apostolic Church.Footnote 14 Likewise, two Assyrian men, Fagrat Saiatov and Saiad Azizian, had been living and working in Armenian villages in the Erivan district for thirteen and twenty years, respectively, before they petitioned the Russian government to allow them to join their neighbors in their faith.Footnote 15

Most converts into Armenian Christianity were Muslims from the South Caucasus who spoke Kurdish, Tatar (Azerbaijani), or Turkish. The landscape of conversions also encompassed local Jews, Assyrians, and Yazidi Kurds, as well as occasional Muslim immigrants from the North Caucasus and Crimea. Requests to join the Armenian Apostolic or Catholic churches typically came from young single men and women, but entire families converted as well. Conversions to Armenian Christianity were second only to those into Orthodox Christianity, the empire's dominant faith that was heavily promoted by the state and the Russian Orthodox Church.

The number of conversions to Christianity increased as a result of the Russian conquest of this region, long contested between the Ottoman Empire and Iran, in the early nineteenth century. In 1801, Russia annexed the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartli and Kakheti and, later in the same decade, the western Georgian kingdom of Imereti and the principalities of Guria and Megrelia, and the Muslim khanates of Ganja, Karabakh, Shaki, and Shirvan farther east. Qajar Iran recognized Russian suzerainty over these territories in the Treaty of Gulistan of 1813. Fifteen years later, the Treaty of Turkmenchay ended another Russo-Iranian war, awarding the khanates of Erivan, Nakhichevan, and Talysh to Russia. After that, Russia reimagined all of its territories south of the Caucasus Mountains as one region, Transcaucasia, better known today as the South Caucasus, and ruled them as the Caucasus Viceroyalty with its capital in Tiflis.Footnote 16

The Russian Empire's newest region was also its most religiously heterogeneous (see table 1). Armenians were the largest Christian community, scattered throughout the South Caucasus and forming a majority in the Erivan province. Turkic-speaking Tatars, or Azerbaijanis, most of whom were Shi‘a Muslims, constituted the largest ethno-linguistic and religious group in the region, dominating the Baku and Elisabethpol provinces. The Kurdish population was split into Sunni and Shi‘a Muslims and Yazidis, and lived in the mountains of the Erivan province. Georgians, an Orthodox Christian people, resided in the plateaus between the Greater and Lesser Caucasus Mountains, in the Tiflis and Kutaisi provinces. Smaller native communities included Christian Greeks, Ossetians, and Assyrians; Shi‘a Muslim Persians, Talysh, and Tat; Sunni Muslim Turks, Lezgins, and Avars; and Georgian Jews and Mountain Jews. Following the Russian conquest, the South Caucasus also became home to Russian Orthodox, Old Believer, and Protestant settler communities from Russia's southern and central provinces.

Table 1 Population in the South Caucasus by faith, 1886–1890

I omit data for the Kutaisi province, the Kars region, and the Batum, Zakatala, and Sukhum districts. Adapted from Artur Tsutsiev, Atlas etnopoliticheskoi istorii Kavkaza, 1774–2004 (Moscow: Evropa, 2007), 42.

Conversions into Armenian Christianity constituted a small-scale but sizeable phenomenon throughout the region. I located about a hundred and twenty petitions to convert to Armenian Christianity from individuals and families throughout the South Caucasus in 1857, 1859–1860, 1862–1863, 1868, and 1872–1873; about seventy-five from the Erivan province between 1890 and 1907; and over thirty from the Baku province between 1905 and 1915. Complete documentation for all years and all provinces is missing, but the available archival evidence suggests the breadth of this phenomenon.Footnote 17

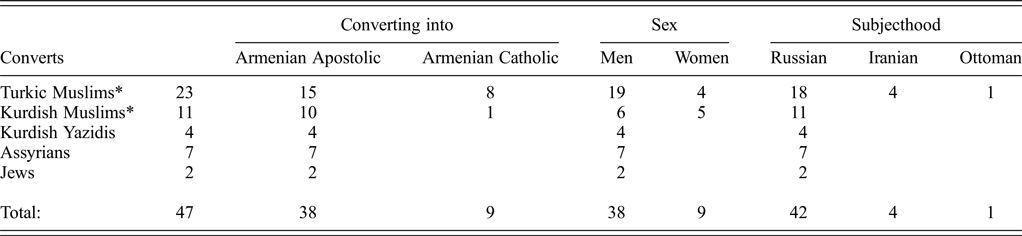

The interest in converting to Armenian Christianity, in addition to being consistent over time, came from different ethnic and religious communities. In 1863, for example, forty-seven individuals requested a conversion to the Armenian Apostolic and Armenian Catholic creeds in the South Caucasus. Of them, at least 70 percent lived in the Erivan province and the rest in the Tiflis and Elisabethpol provinces (see table 2). Almost three quarters of converts were Muslims, about half spoke a Turkic language (Turkish or Tatar/Azerbaijani), and a third spoke Kurdish.

Table 2 Converts to Armenian Christianity in the South Caucasus, 1863

* Tsarist officials recorded Muslim petitioners under two categories: “Muslims,” who could have been speakers of Tatar/Azerbaijani or Turkish, Sunni or Shi‘a, and “Kurdish Muslims,” who could have been Sunni or Shi‘a. Based on data in SSSA f. 8, op. 1, d. 3666 (1863).

Conversion to Armenian Christianity was primarily a rural phenomenon, and many petitioners had originally moved to Armenian villages for work. In 1900, a Muslim couple, Ali Kalandar oğlu and Khana Unus kızı, petitioned to convert to the Armenian Apostolic faith. Having arrived from the Ottoman subprovince of Bayazıt twenty years prior, Ali worked as a communal shepherd in the Armenian village of Vagarshapat, only several miles north of the Ottoman-Russian border.Footnote 18 Vagarshapat was a common destination for future converts. Home to the Echmiadzin Cathedral, the mother church of the Armenian Apostolic Church, it offered economic opportunities in this region and attracted people from all over the Armenian highlands. Simon Akopian, an Ottoman Assyrian man; Dzhabo Msto kızı, a Kurdish Muslim woman; and Hanlar-bek Sultan-bek oğlu and Ahmed Abbas oğlu, two Tatar men, all moved to Vagarshapat, where they chose to become Armenian in the 1890s.Footnote 19

The migration of shepherds, sharecroppers, and artisans reveals that geography and the labor market were fundamental to the conversion drive in the Caucasus. For many, a conversion was an outcome of their relocation for work and eventual social integration into the Armenian community. In 1873, for example, a Muslim Lezgin man named Shaban petitioned the authorities to allow him to join the Armenian Apostolic Church. Single and twenty-three years of age, he was born in southern Daghestan and moved to an Armenian village “in order to find a means of livelihood.” Having worked among Armenians and having observed their devotion to their Christian god, he started attending their church and following their rites, and eventually made a decision to convert.Footnote 20 It may have been a coincidence that these labor migrants found work in an Armenian village and not a Kurdish or Tatar one. However, it was also telling of the economic and cultural environment at the time that many Armenian localities, especially those near big monasteries, could provide livelihood to outsiders and that non-Armenians felt sufficiently accepted by locals to contemplate a conversion.

BECOMING ARMENIAN

Most conversions to Armenian Christianity took place on the slopes of the Lesser Caucasus Mountains, stretching from the Russo-Ottoman border in western Georgia across the Armenian highlands toward the Russo-Iranian border. In that mountainous region, religion, language, and sedentary or nomadic status were primary markers of identity and, as such, often overlapped. Local Armenians spoke the eastern dialect of Armenian and adhered primarily to the Armenian Apostolic faith, which tsarist authorities referred to as Gregorian. The head of the Church, the Catholicos, resided in the Echmiadzin Cathedral, near Erivan, and his ecclesiastical authority was recognized by most Apostolic Armenians in Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and Iran. A minority of Russia's Armenians were Catholic. The centers of Armenian political and intellectual life were Tiflis and Baku, with important diasporic economic outposts farther north in Crimea, New Nakhichevan (now Rostov-on-Don), and Astrakhan. Most Armenians, though, were poor peasants living on high plateaus along the southern rim of the Caucasus region.Footnote 21

What did it mean to become Armenian in the late imperial South Caucasus then? To an unsuspecting observer, many petitioners would seem to already be Armenian. They spoke the language, wore Armenian dress, and lived among Armenians. Intent on staying in their new surroundings, their baptism seemed a formality. For their neighbors, the answer must have been more complicated. Without their acceptance into the Armenian church and their participation in communal ceremonies that were often centered around the church, the petitioners, no matter how loyal and acculturated, could not be their full brethren. For the state, the answer was simple: they were not Armenians. The Russian subject's religious identity was affixed to a community into which they were born. Only the government could create a new legal identity and affirm one's membership in a religious community and, through it, one's place within the society.

From the late eighteenth century, the Russian government upheld religious toleration of non-Orthodox faiths and extended its protection to certain religions.Footnote 22 Amidst legislation on religious governance, tsarist authorities issued a set of rules on conversions, which betrayed the state's preferential treatment of some religions over others. In the hierarchy of faiths, Russian Orthodoxy occupied the top position; other major Christian confessions followed suit; Islam and Judaism, the empire's second and fourth largest confessions, came next; and all other beliefs were at the bottom. This hierarchy determined one's legal conversion options. Jews and Muslims were free to convert to each other's faith and to any form of Christianity. Non-Orthodox Christians, such as Roman Catholics and Apostolic Armenians, could convert to any Christian denomination, but not to Islam or Judaism.Footnote 23 The Russian Orthodox, adherents of Russia's main and largest church, were not allowed to leave Orthodoxy. The privileged position of the Russian Orthodox Church extended to proselytism. Only Orthodox clergy could proselytize openly in the empire.Footnote 24

The Russian imperial legislation singled out the Caucasus, with its heterodox populations and a penchant for religious fluidity, as a region where more liberal rules on conversion, particularly into Christianity, applied. Throughout the empire, non-Orthodox Christian churches could accept others into their fold only with the approval of the Minister of the Interior, who resided in Saint Petersburg. In the Caucasus, where conversion requests were more numerous, applications were reviewed locally and could be approved by the Viceroy in Tiflis.Footnote 25

In his study of conversions in early modern Russia, Michael Khodarkovsky notes, “Conversion in Russia was spiritual least of all; it generally involved only a nominal transfer of religious identity.”Footnote 26 By contrast, in the late tsarist Caucasus conversions of local farmers and pastoralists seem to have entailed some spiritual transformation and Armenian acculturation. An even greater change was the insistence of the Russian government, which had the right to deny or approve every petition, on a bona fide religious conversion. The late nineteenth-century tsarist authorities were preoccupied with the legitimacy of conversions, particularly of those not into Russian Orthodoxy. Importantly, the authorities determined an applicant's eligibility for conversion based on the ill-defined notion of sincerity of their faith.

By evaluating the sincerity of one's religious beliefs, the Russian government was making a moral judgment, further encroaching on the turf of religious authorities whose recommendations for baptism the government had the authority to reject. The Ottoman government, too, turned to the idea of sincerity as a criterion in approving conversions. In the 1890s, the Ottoman authorities rejected mass conversions of Armenians into Islam on the pretext that they were insincere, despite reassurances by Armenian converts.Footnote 27 Notably, both the Ottoman and Russian governments construed the sincerity of faith emanating solely from religious and intellectual reasons to convert and placed the burden of proof on petitioners, thus providing themselves a leeway to deny conversions that deemed inconvenient. The late imperial state excluded external factors, such as a fear of massacres or pogroms, from legitimate reasons to seek a bona fide conversion. Yet the notion of sincerity served different purposes for the Ottomans and the Russians. Istanbul utilized it to establish beyond doubt, for the benefit of observing European consuls, that conversions to Islam were voluntary and involved no duress. Saint Petersburg insisted on converts’ sincerity in order to preserve the existing religious hierarchy, namely to ensure that Armenian clergy did not proselytize and to prevent the “seduction” of the Orthodox faithful.

To evaluate one's sincerity, the government solicited recommendations from three sources: the Armenian church, host village communities, and provincial civil authorities and law enforcement. Those who wished to convert to Armenian Apostolic Christianity would first approach their local Armenian clergy, who, although banned from proselytizing, could help applicants, most of whom were illiterate, to write a formal petition that declared their intent to convert. Most petitions were template statements that expressed devotion to the one true Armenian faith but revealed little about what kind of life a petitioner led or what brought them to the Armenian church. In addition to support from a local priest, petitioners needed to secure a testimony from their local community that verified their identity, that they did not belong to the Russian Orthodox Church, and their sincerity of faith. Petitioners typically submitted communal testimonies signed by dozens of their Armenian neighbors. A local Armenian diocese would then forward the application to the Armenian Synod in Echmiadzin. Armenian church authorities, wanting to increase their flock, likely approved most cases that they received and then forwarded the documentation to Russian civil authorities in Tiflis asking whether the government objected to the conversion.

Upon receiving the application via the Synod, the Viceroy's Chancellery in Tiflis would instruct governors of the province and the district where the applicant lived to verify that all submitted information was correct. The civil authorities would then ask a district police chief to authenticate an applicant's clean criminal record. In practice, Tiflis approved the vast majority of petitions to convert to Armenian Christianity, which are preserved in the archive. That said, the applications that did not pass the initial stages of review, having failed to secure endorsements by the church and the local Armenian community, likely never reached the Viceroy's desk (or the archive). The rare denials occurred when the government suspected that a petitioner had been baptized into Russian Orthodoxy.Footnote 28 Tiflis would also not let the Armenian church collect “dead souls” and denied conversions to anyone who could not be found at their declared address. When the Viceroy assented to the petition, the Chancellery would inform Echmiadzin, which then scheduled a baptismal ceremony for the applicant. The Armenian clergy was forbidden from performing conversions without the Viceroy's formal approval, although Armenian priests routinely made exceptions for those applicants who were on their deathbed and could not wait.Footnote 29

From the state's perspective, Muslim, Yazidi, and Assyrian applicants legally became Armenian Christians upon the final approval of the Viceroy and the subsequent baptismal ceremony performed by the Armenian clergy. The purpose of this lengthy bureaucratic process was for tsarist officials to evaluate how culturally Armenian the petitioners had already become: whether they were familiar with Armenian rites, knew enough Armenians, and would continue living their lives among Armenians. Applicants’ personal journeys and perspectives on what it meant to be an Armenian Christian are mostly hidden from us, but the starting point of their personal process of conversion long preceded the date of their formal petition. The archival evidence ends with the Viceroy's seal, assenting to the legal, social, and spiritual transformation of the petitioner's identity. New converts then fade from the historical record; tsarist administrators did not follow up on their progress, and foreign travelers rarely reached their mountainous villages, let alone asked about conversions. For all we know, new converts had become Armenians.

CLIMATE FOR CONVERSION

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Russia's expansion and centralizing reforms created conditions that prompted many Muslim families to convert to Christianity and, in particular, to join the largest Christian church in the South Caucasus. The favorable climate for conversion emerged as a result of Russia's conquest of the North Caucasus by 1864, land reforms in the 1860s and 1870s, and accelerated sedentarization of nomadic populations since the 1880s.

The conquest of the North Caucasus guaranteed Russia's domination over Europe's highest mountains and afforded the empire easy access to its South Caucasus provinces. It also unequivocally signaled to the region's Muslim inhabitants that the empire favored Christian subjects. In the final stages of the Caucasus War of 1817–1864, around half a million Muslim Circassians were expelled, or prompted to emigrate, from the Kuban region into the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 30 Shortly after the end of the war, the government authorized a semi-forced migration of Muslims, mostly Chechens, out of the Terek region into the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 31 Simultaneously, the authorities opened up the Kuban and Terek regions to agricultural colonization by Russian, Ukrainian, German, Greek, and other Christian peasants.

By the 1860s, tsarist policies nurtured a political culture wherein one's faith supposedly correlated with one's loyalty to their empire. The authorities in the Caucasus regarded Christians, especially Orthodox settlers, as a trustworthy population that was expected to be loyal to the tsar and deemed Muslims as suspect for their purported allegiance to the Ottoman sultan. Consequently, Muslim populations expected the state to dole out punishments and favors based on one's faith.Footnote 32 In 1865, for example, 2,680 Chechens who had previously emigrated to the Ottoman Empire attempted to return to Russia. The Chechens arrived at the Ottoman-Russian border, and, upon the Russian government's refusal to readmit them, Chechen chiefs announced that they all were willing to convert to Orthodox Christianity on the spot if that guaranteed their readmission into Russian subjecthood and return to their homeland. Neither conversion, nor readmission, of the Chechens happened, but it is telling that the Chechen leaders, like many Muslims in the Caucasus, believed that the government was more likely to accept new Christian subjects than old Muslim ones.Footnote 33 Religious conversions of Muslims into Armenian Christianity in the South Caucasus occurred in an environment where many expected the government to favor Christian converts.

Why convert to Armenian Christianity, then, and not to Russian Orthodoxy, which, as a state-favored religion, offered more social prestige throughout the empire? In the mountainous southern rim of the South Caucasus, the Russian Orthodox Church had a negligible presence because few Slavic settlers wished to move to a rugged terrain on the doorstep to the Ottoman and Qajar empires. The Armenians’ religion epitomized Christianity for local Muslim and Yazidi populations. Moreover, the Armenian Apostolic Church was seen as an ascendant institution in the region. The Armenian Apostolic Church grew in prominence as the Armenian population in the region increased substantially since the Russian conquest. Thus, many Armenians moved to the South Caucasus in the aftermath of the Russo-Ottoman and Russo-Iranian wars between 1826 and 1829.Footnote 34

Conversions to Armenian Christianity were driven not only by familiarity and prestige, but also for economic reasons. In the 1860s, the tsarist government initiated a series of reforms meant to tie the Caucasus Viceroyalty, composed of formerly Qajar, Ottoman, and independent territories, closer to Russia. The most ambitious one was the so-called peasant reform, which reorganized land ownership and taxation in the region. The peasant reform was implemented in the North Caucasus and in Georgia throughout the 1860s and in the provinces of Erivan, Baku, and Elisabethpol in 1870. These South Caucasus territories featured a fragmented land tenure system, wherein some land belonged to local notables, Muslim beks and Armenian meliks, and some to the state, whereas local sedentary and nomadic populations used the land in exchange for corvée labor.Footnote 35 The peasant reform extended only to the land owned by notables. Because the Russian government solicited the support of landholding elites in its strategic southern borderlands, its land reform, instead of empowering peasants, further entrenched the notables’ rule. Large landowners preserved most of their land and the right to collect rent from peasants. Peasants obtained the right to buy out land owned by notables, but few could afford to do so and now also had to pay increased taxes to the state. By 1912, not a single peasant household in the Erivan, Baku, and Elisabethpol provinces succeeded in buying out land in full ownership.Footnote 36 Peasants living on the state-owned land were not better off either. By the late nineteenth century, about half of state peasants lacked sufficient agricultural land and had to resort to renting land owned by notables in exchange for their labor.Footnote 37 The state's confiscation and redistribution of fertile agricultural land to Russian settlers further aggravated land pressure in the region.Footnote 38

The mountainous regions of the South Caucasus, such as western and southern parts of the Erivan province, had the least amount of available fertile land and the largest number of landless peasants.Footnote 39 Most conversions occurred precisely in those areas. Many impoverished peasants relocated to nearby towns or moved around for seasonal work, which brought them into contact with Armenians and their church. Later, some of them petitioned to convert to Armenian Christianity.

A religious conversion generated a new legal status that accorded converts new social and economic rights. The Russian state categorized its non-elite subjects by their religious affiliation, which determined their duties and privileges. For example, Muslims and Yazidis in the Caucasus were exempt from military service and instead paid a special tax, similar to cizye and later bedel-i askeri payments that non-Muslims made in lieu of military service in the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 40 Notably, one's religious affiliation was tied to one's registration of legal residence, which was compulsory for every Russian subject and notoriously difficult to change. A Tatar or an Armenian could not easily move to another village or town and register there. Converts to another faith, however, had legal ground to change their residence to a community of their new coreligionists.Footnote 41

For many landless converts, their baptism in a village church was intimately linked to gaining residence in that village and an ability to make a living off their own plot of land. Those whose petitions to join Armenian Christianity were approved became legal residents in Armenian villages living on the state- or church-owned land, which remained untouched by the peasant reform of 1870 and was used communally. The new residents then received a land allotment in a regularly scheduled land revision, when all agricultural and pasture land was reassigned within the community depending on its number of households.Footnote 42 In fact, the government required communal testimonies by Armenian neighbors in support of petitioners’ conversion precisely because the new converts were expected to remain in that village, be legally recognized as a permanent resident there, and share its resources.

Some petitioners may have hoped that, by becoming Armenian, they would gain access to the land owned by the Armenian Apostolic Church or that the Church would intercede on their behalf in their requests to be issued the state-owned land. For example, in 1897, Russian authorities investigated an incident in the village of Halfalu in the Erivan province, where Armenian clergy promised free agricultural land to Armenian converts into Orthodoxy should they return to the Armenian Apostolic Church. The Armenian priests were prosecuted for encouraging apostasy from Orthodoxy.Footnote 43 Cases of conversion in return for land were ubiquitous throughout the South Caucasus and often implicated the Orthodox Church. Thus, in 1889, 116 Apostolic Armenians in the village of Kul'py of the same province converted to Russian Orthodoxy. Two years later, they sent the Catholicos a petition with a request to return to the Armenian Apostolic faith. Because leaving Russian Orthodoxy was illegal, the government opened an investigation and discovered that these converts to Orthodoxy were landless salt mine laborers from a mixed Armenian-Muslim village. They had converted to Orthodoxy because an Orthodox priest had promised to secure free land for them. After he failed to deliver, the disappointed Armenians stopped attending Orthodox services and petitioned Echmiadzin to take them back.Footnote 44 Two decades later, Russian authorities investigated a similar incident in the village of Malyi Karakilis, also in the Erivan province. An Armenian Catholic community had converted to Orthodoxy and was given land allotments through the intercession of the Russian Orthodox Church. Upon receiving the land, the community reverted back to practicing Armenian Catholicism.Footnote 45

The disruption of nomadic life in the South Caucasus also contributed to conversions to Armenian Christianity, especially among Kurds. Russia's Kurdish communities could be found in the districts of Erivan, Echmiadzin, and Surmali, all near the Ottoman border and in areas with large Armenian populations. Kurdish nomads migrated between their summer and winter pastures across the highlands that stretched from northern Syria to western Iran, with the Russian-held territories forming the northernmost tip of the Kurdish world. The tsarist overhaul of land tenure and taxation in the South Caucasus was designed for sedentary populations who would till the land year-round, and it put the nomads at a disadvantage.Footnote 46 In 1870, Kurdish nomads lost the right to many of their historical pastures, and in 1884–1885 the government further imposed a tax on nomadic populations for the right to use summer and winter pastures. As a result, many Kurds could no longer sustain a pastoral lifestyle and turned to sedentary farming. The newly settled Kurdish villages were destitute; in some districts up to a half of Kurdish villages did not have sufficient land for agricultural pursuits or even crop seeds to start farming. Migrating west into Ottoman Kurdistan would not solve the Kurds’ problem, because Ottoman Kurdish communities were also devastated, having lost many of their pastures to the Ottoman government and being in the throes of a power struggle among Ottoman Kurdish tribal leaders.Footnote 47 Moreover, severe droughts and cold winters plagued the Kurdish highlands in 1844–1846, 1879–1880, 1887–1889, and 1891–1893, which severely affected Kurdish pastoral economies and prompted mass displacements of nomads.Footnote 48 Many South Caucasian Kurds, therefore, moved into towns to the north and east of Mount Ararat to find work. By 1903, 87 percent of able-bodied Kurdish men in the Erivan province sought income as seasonal laborers. They worked as water carriers, salt miners, shepherds, and porters, and often lived among local Armenian populations.Footnote 49 Many men brought their families to these Armenian localities and over time some converted to Armenian Christianity and adjusted their legal residence.

Conversion also constituted a legal tool to attain freedom from slavery. In 1873, a Muslim household slave (Rus. unautka) named Fatima, from Armavir in the Northwest Caucasus, petitioned the Armenian diocese of Astrakhan and the Synod in Echmiadzin to allow her to become an Armenian. Eighteen years of age, she had grown up in the home of an Armenian master and was then sold into or passed on to the household of another Armenian in Nakhichevan (now Naxçıvan, Azerbaijan). With her new master's permission, she wished to become a Christian.Footnote 50 Fatima's conversion drew on the contestation of slave ownership in the Caucasus at the time. By the mid-nineteenth century, many communities living between Abkhazia and Daghestan practiced indigenous forms of slavery. The terms of enslavement could vary, even within the same village, from fixed-term household servitude, akin to Russian serfdom, to hereditary agricultural bondage, similar to Atlantic plantation slavery. Shortly after the abolition of serfdom in Russia's central provinces in 1861, the Russian government started to phase out slavery in the Caucasus. Serfdom and slavery were outlawed in the Terek region in 1866, the Daghestan region in 1867, the Kuban region in 1868, and the Sukhum district in 1870.Footnote 51 The emancipation was gradual, with the ownership of existing slaves remaining legal for some time, which explains why Fatima, who had been owned by two Armenian households, remained unfree into the 1870s. A Muslim slave's conversion to Christianity typically hastened their emancipation.Footnote 52 Fatima's conversion from Islam to Armenian Christianity marked her transition from an enslaved to a free woman.

ANXIETIES AND STAKES OF CONVERSION

Conversions of South Caucasians into Armenian Christianity were rarely challenged by the tsarist government and provoked no unrest. Nevertheless, the idea of religious conversions generated much anxiety in these heterogeneous imperial borderlands. Conversions in the nineteenth-century South Caucasus were inevitably bound up with imperialism and colonialism, as well as transnational Armenian politics.

Russia had a long history of baptizing non-Christian populations, although its evangelizing zeal subsided by the late nineteenth century. As Russia expanded southward and eastward, the government actively abetted mass conversions to the Orthodox faith, especially those of pagans and of Muslims. In the Middle Volga region, thousands of Muslim Tatars were baptized, often forcibly, into Orthodoxy in the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Many Bashkirs, Ossetians, Kabardins, and other Muslims in Russia's southern provinces also joined the Russian Orthodox Church.Footnote 53 In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the tsarist government compelled about 3,350,000 Greek Catholics in the empire's western provinces and 110,000 Roman Catholics and Lutherans in the Baltic provinces to convert to Orthodoxy.Footnote 54 By the second half of the nineteenth century, the Russian authorities no longer favored forced mass conversions, let alone in the Caucasus with its large Muslim population and fresh memories of anti-colonial resistance. Independent Orthodox missions, however, continued proselytizing, including among Muslim communities.Footnote 55

The tsarist government monitored closely the course of religious conversions in its newly acquired territories. The South Caucasus was the only region in the empire where Russian Orthodox subjects were outnumbered by non-Christians (Muslims), other Orthodox Christians (Georgians), and other Christians (Armenians). The authorities expressed occasional concern that the historically rooted Armenian Apostolic Church could “seduce” Russian Orthodox Christians in the region. The government investigated and punished those Orthodox faithful who had converted to the Armenian faith. In most cases, those were Armenian converts who tried to rejoin their former church.Footnote 56 The government, however, did not object to the conversion of non-Orthodox subjects into Armenian Christianity, especially when converts were not Christians.

For the Armenian Apostolic Church, conversions correlated with an increase in its tithe-paying flock and prestige in the South Caucasus. Echmiadzin's primary concern was to solidify its religious authority over most Armenians. The Armenian Apostolic Church long wished to bring Armenian Catholics into its fold. The Russian government, which hoped to gain political influence among Ottoman and Iranian Armenians via the Russian-based Catholicos, supported Echmiadzin's efforts, with the Minister of the Interior describing Armenian Catholics as “the lost progeny of that ancient church.”Footnote 57 On the other hand, both the Apostolic and Catholic Armenian churches opposed the growing influence of Protestant movements, which offered many Armenians emancipation from rigid boundaries of the old churches. One did not have to search far to see how successful the well-funded western Protestant missions could be. In the neighboring Ottoman Empire, particularly in its Armenian provinces near the Russian border, Protestant missionary boards established dozens of churches, schools, and hospitals serving local populations, and converted thousands of Armenians.Footnote 58 In the South Caucasus, Echmiadzin's anti-Protestant sentiments largely aligned with Russia's opposition to the spread of Baptism and other Protestant creeds among Russian settlers.Footnote 59

For converts, whatever social and economic incentives they might have had, a conversion was always a personal act touching on their communal identity and individual safety. Changing one's faith was never simple. For many, it was the hardest decision they had to make because, in practice, becoming an Armenian meant severing ties to their old community and its protections. Many converts, especially those who had not yet lived in Armenian villages, expected to be branded as traitors to their kin and to their faith, and risked their lives. In their petitions, many converts spoke of social ostracism and persecution. Thus, a Kurdish woman, Zeino Mgoian, lived through “relentless harassment by her relatives” for her desire to convert to Armenian Christianity.Footnote 60 Even those who lived separately from their extended families feared retribution for transgressing boundaries held sacred by many. An Iranian Shi‘a man, Said Aga Buzurk, asked the authorities to allow him to convert in the nearby Tatev Monastery because he feared the “fanaticism of local Muslims” should he be required to travel across Armenia for a baptismal ceremony in Echmiadzin.Footnote 61

For Russia's Muslims, the notion of a Christian baptism was fraught with trauma from their earlier encounters with the Russian state. After a devastating war in the North Caucasus, many Muslims feared that the government might force them to become Christians. The rumors of imminent forced conversions helped to drive mass emigration of Muslims from the North Caucasus to the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 62 Indeed, the violent conquest of the North Caucasus emboldened hardliners within the government to openly endorse “re-converting” Russia's Muslim populations, who may have once been Christian. The Society for the Restoration of Orthodox Christianity in the Caucasus, founded in 1860, sponsored the construction of new churches and schools and translated the Bible into several North Caucasian languages.Footnote 63 Its Orthodox missionaries freely proselytized among Abkhazians, Ossetians, Circassians, and others. The Society counted among its patrons the Russian empress and the Viceroy of the Caucasus, and its leaders outlined their vision for the region in unambiguous terms, “With time, Christianity would embrace all [Caucasus] mountains and, upon the ruins of Islam, would even settle where it had not been before.”Footnote 64

OTTOMAN AND IRANIAN CONVERTS

Russian Tatars, Kurds, and Assyrians were not the only ones converting to Armenian Christianity. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the South Caucasus emerged as a destination for Ottoman and Iranian subjects who wished to become Armenian. Similar to apostasy from Russian Orthodoxy in Russia, apostasy from Islam, or irtidād, remained illegal in the Ottoman Empire and Iran. Many Sunni and Shi‘a jurists interpreted shari‘a law to prescribe the death penalty to adult men in cases of irtidād, which had served as a powerful deterrent against converting out of Islam publicly.Footnote 65 As late as 1843, an Armenian who had converted to, and then left Islam was publicly executed in Istanbul. Shortly thereafter, the European Powers pressured the Ottoman government to suspend capital punishment for Muslim apostates, yet they still risked mob justice or imprisonment.Footnote 66 American missionaries mentioned as many as fifty conversions out of Islam in the Ottoman Empire in the 1860s and 1870s and several dozen in Iran by the 1910s, yet these remained clandestine and required converts to “disappear” into Christian neighborhoods and rely on protection by foreign consuls.Footnote 67

Foreigners who petitioned to convert, similar to Russian subjects, came from areas with sizeable Armenian populations and were somewhat familiar with Armenian rites and customs. Most foreign converts were Turkic- and Kurdish-speaking Muslims living within the Greater Caucasus. Ottoman subjects came from around Muş and Bayazıt, whereas Iranian subjects arrived from Khoy, Tabriz, and smaller villages in Iran's northwestern provinces.Footnote 68

Foreign converts typically moved to the Russian domains to find seasonal or permanent employment. For example, in 1891, Gasan Gusein oğlu petitioned the Russian authorities to convert to the Armenian Apostolic faith. When he was fifteen years old, he left his native Iran in search of agricultural work. He found a job in the Armenian village of Shikhmakhmud in Nakhichevan, where he stayed for twenty-one years. Gasan claimed that he had long abandoned practicing Islam, had mastered the Armenian language, and now wished to formally become an Armenian Christian.Footnote 69

In their petitions, many applicants claimed a long fascination with the Armenian faith yet an inability, because of local laws or attitudes, to convert at home. An Ottoman Kurdish man, Razgo Ismail oğlu, listed as pagan (likely, Yazidi) in his documents, moved to an Armenian Catholic village in the Aleksandropol district on the Russian side of the border. His petition stated that he was born of “crooked-faith parents” (Rus. krivovernye roditeli) and remained “in darkness” until he discovered Armenian Catholicism.Footnote 70 An Iranian Azerbaijani man named Muslim Ali Mirza claimed that he had lived in an Armenian village in Iran and wished to convert there but was legally unable to do so. Upon crossing the Russian border, he moved into another Armenian village and started visiting a local Armenian monastery, which further strengthened his desire to convert.Footnote 71

The Ottoman government knew that some Ottoman Muslims were converting to Armenian Christianity. In 1893, the Ottoman military authorities were investigating one Osman Yakup, who had joined the Armenian Apostolic Church, likely in order to marry an Armenian woman. Since he was an army deserter who fraternized with Armenians amidst the Ottoman war on Armenian revolutionary organizations, he was arrested and interrogated. The authorities built a case against him, and blamed his conversion on an Armenian conspiracy, allegedly active on both sides of the Ottoman-Russian border, to secretly convert Muslims and then place those converts in Ottoman military units.Footnote 72 In the late nineteenth century, irtidād became not only a religious transgression but a betrayal of the Ottoman state, whereas a conversion to Armenian Christianity could be construed as sympathy for Armenian revolutionaries and Russia.Footnote 73

Some Muslims reclaimed their Armenian roots by converting to the Armenian faith of their ancestors. In 1873, a forty-year-old Muslim man, Said Aga Buzurk, originally from Khoy in northern Iran, sent the following petition to Tiflis:

My mother was born an Armenian Christian. When I was nine and started distinguishing between good and evil, she made me swear an oath. “My son, I am a Christian,” she confessed, “and was forcibly converted to Islam, when I married your father. Now I realize that this faith is false and, therefore, implore you to accept the Armenian Gregorian faith, into which I was born.” Following the oath that I gave my mother, I left my homeland with a valid passport and have been living in the Zangezur district … where I watch closely the holy rites of the Armenian Church and fervently wish to be a Christian of the Armenian Gregorian faith.Footnote 74

In support of his petition, twelve residents of the Armenian village of Tatev, in southern Armenia, affirmed that he had been living among them for a year and genuinely wished to become an Armenian. The sentiments of Said Aga, born to an Armenian mother, closely resemble those of hundreds of Turkish citizens, descendants of forcibly converted Armenians, who have been rediscovering and reconverting into Armenian Christianity in recent years.Footnote 75

For Ottoman and Iranian petitioners, a conversion also ultimately led to a change in their legal status. Foreign applicants went through the same bureaucratic process as Russian subjects. By the time of their conversion, most foreign converts had lived and worked in the Russian Caucasus for years and tried to stay put by naturalizing as Russian subjects and gaining residence rights in their Armenian villages.

The cross-border travel for conversion flowed both ways. Christian residents of the South Caucasus, who wished to convert from Christianity into Islam, an act that was illegal in Russia, could choose to escape to the Ottoman Empire and Iran. In 1852, for example, several Georgian teenagers crossed the border into Ottoman Lazistan “with the desire to become Muslims.” They were not pursued by tsarist authorities and likely converted to Islam and became Ottoman subjects.Footnote 76 In another case, in 1867, sixteen-year-old Georgii ran away from Baku to Iran. His father, a civil servant in the Viceroy's employment, refused to believe that his son acted of his own accord and claimed that Georgii was “seduced by the flattering promises of the Persians.” He enlisted the services of Russia's Foreign Office to escort his adventurous son back to Russia. Georgii then ran away to Iran for a second time, where he became a Shi‘a Muslim and, within three years, married an Iranian woman and had children.Footnote 77 Rebellious teenagers aside, the porous Russo-Ottoman-Iranian frontier long benefited draft evaders and other law-breakers, who could escape to freedom in another empire. They commonly found a new home, a new faith, and, with it, a new legal identity in the neighboring realm.Footnote 78

FREEDOM OF CONVERSION AFTER 1905

In April 1905, amidst workers’ strikes and peasant unrest across Russia, the Governing Senate issued a decree that legalized conversions out of Russian Orthodoxy. The decree undermined the old hierarchy of imperial confessions. This reform prompted much celebration throughout the empire, particularly among non-Orthodox subjects in tsarist borderlands, who viewed it as an overdue admission of their equality with Orthodox Christians.Footnote 79 Between 1905 and 1915, 425,594 people left the Russian Orthodox Church. Most were Greek Catholics in western Ukraine, Lutherans and Roman Catholics in the Baltic provinces, and Muslims in Siberia and the Volga region who had previously converted to Orthodoxy and could now legally revert to their old faith.Footnote 80 The decree of 1905 also transformed the landscape of conversions in the South Caucasus. Previously, most petitioners in the region had converted into Russian Orthodoxy and Armenian Christianity, with the latter faith attracting primarily rural and nomadic residents. Now, most petitioners were urban residents who requested permission to leave Orthodoxy.Footnote 81

While the decree of 1905 normalized conversions throughout the empire, it made clear that full legal equality was still out of reach of many Russian subjects. In the early twentieth century, the Armenian Apostolic Church received petitions from a new and unexpected group of applicants: Russian Jews. Since the late eighteenth century, the Russian government had passed a series of restrictions on its Jewish subjects. Notably, it prohibited most Jews from residing outside of the Pale of Settlement, implemented Jewish quotas in higher education, and severely restricted Jewish rights to own or acquire agricultural land. In the 1880s, following brutal pogroms against Jews, the Russian government further diminished Jewish rights in the empire. For instance, in 1883 the authorities prohibited Jews who were not native to the Caucasus from residing in the region, essentially expelling all Ashkenazi Jews who had moved to the booming oil town of Baku and other urban areas.Footnote 82

In an age where all conversions were legalized yet discrimination against Jews persisted, for many Jews a conversion constituted a practical choice, both forced on them and legitimized by the state. Throughout the nineteenth century, many Jews converted to Russian Orthodoxy, if only to escape restrictions that were specific to followers of Judaism.Footnote 83 In the post-1905 era, although many Jewish converts petitioned to return from Orthodoxy to Judaism, Jewish conversions to Christianity persisted and even increased in number, reflecting a rising tide of anti-Semitism. Yet joining Orthodoxy no longer provided the same social benefits to Jews as before. Russian officialdom invented legal categories that marked Jewish converts to the Russian Orthodox faith as separate, such as “baptized Jew,” “of Jewish origin,” or “apostate from the Jews.”Footnote 84 On the other hand, joining another Christian denomination provided a new and wholesome legal identity to Jewish converts, and those conversion processes were often faster and less administratively burdensome.Footnote 85

In the eyes of Russian law, all converts to Armenian Christianity became Armenians and, as such, they encountered no restrictions on residence within the Caucasus or elsewhere. Consequently, between 1910 and 1915 the Armenian Apostolic Church received petitions to convert from many Jewish families. People from various Jewish communities sought to change their faith and, with it, their legal status. The Armenian clergy reported conversion requests from Jews in Odessa, Kishinev, Kiev, Kharkov, Crimea, Baku, Astrakhan, Samarkand, and Kokand.Footnote 86

Russian officials, well aware of the legal obstacles faced by the empire's Jews, questioned the sincerity of Jewish applicants. In an age when others enjoyed a greater freedom to convert, even out of Russian Orthodoxy, Jewish petitioners were compelled to prove beyond all doubt that they wished to convert to Christianity purely for spiritual and intellectual reasons. For example, three men and a woman, of the Brodsky and Halevsky families, submitted requests to join the Armenian Apostolic Church in Kharkov in 1911. In their petitions, they expressed admiration for the Christian spirit of “love thy neighbor as thyself” and lamented that Judaism focused too much on revenge.Footnote 87 Not all were convinced by applicants’ statements. In 1910, Minister of the Interior Pyotr Stolypin warned Echmiadzin that conversions by Jews were often motivated not by “a genuine attraction to the high teaching of Christ” but by a quest for the “substantive rights” that Jewish converts to Christianity could claim.Footnote 88

In the 1910s, the Russian government, while having approved most requests by Muslims, Yazidis, and Assyrians to join the Armenian church in the decades prior, increased the burden of proof on Jewish applicants. Russia's Department of Religious Affairs of Foreign Confessions instructed the Armenian Synod to scrutinize all applications from Jews in order to ensure the sincerity of their intentions.Footnote 89 Every Jewish applicant was now required to take lessons in Armenian church history and theology from an Armenian clergyman, who would sign a certification of their private tutoring. Jewish applicants had to take an examination in their local Armenian consistory (diocese). Only then were they allowed to submit their petitions to Echmiadzin, which would review and refer their applications to Russian civil authorities for their final approval.Footnote 90

The Russian government justified the additional scrutiny of Jewish petitions by an assumption that Jewish applicants never intended to become Armenian in a religious sense and sought only a new legal status, whereas Muslim and other converts into Armenian Christianity earnestly wished to become Armenian. This thinking, while it acknowledged the state's burdensome restrictions on Jews, reinforced Russia's pre-1905 policies governing religious conversions. By the end of tsarist rule, the government still favored the conversion of non-Christians into Christianity in the Caucasus, whereas a Jew in the Russian Empire was to remain a Jew.

CONVERSIONS IN THE LATE IMPERIAL SOUTH CAUCASUS

In the second half of the nineteenth century, religious conversions in the South Caucasus constituted a social and gradual process and revolved around the change in one's legal status. Conversions depended on social interactions with other communities and personal relations with mediators, as Marc David Baer and Ellie R. Schainker demonstrated for, respectively, early modern Ottoman converts to Islam and nineteenth-century converts out of Judaism.Footnote 91 In the late imperial South Caucasus, too, interactions with local Armenians proved critical for conversions of labor migrants. Tsarist land reforms disrupted the livelihood of many farmers and pastoralists, prompting many to move around for work, which brought different communities into closer contact. Nomads, in particular, had to adapt to a sedentary agricultural lifestyle or serve as day laborers and seasonal workers in nearby towns. Some converts to Armenian Christianity came from Ottoman and Iranian frontier regions in search of sharecropping work in the Russian domains. Correspondingly, conversions in the late imperial South Caucasus were typically gradual, not abrupt, experiences. Most applicants spent years living among Armenians and assimilating into the Armenian environment before submitting their petitions to convert. Furthermore, many religious conversions entailed a spiritual and cultural transformation while leading to tangible benefits. In Russian and Ottoman history, many conversions, typically into the state's preferred faith, allowed converts to maintain or advance their social status.Footnote 92 In late imperial Russia, a religious conversion generated a new legal identity. Tsarist legislation created conditions in Russia's newly acquired territories, such as the South Caucasus, wherein one's conversion, even into a regional faith like Armenian Christianity, could mean getting access to agricultural land, changing one's legal residence, or escaping slavery. In the final decades of tsarist rule many Russian Jews used conversion to the Armenian Apostolic Church as a legal tool to circumvent many restrictions on their freedoms.

The Russian government used its power of final review of religious conversions to preserve the existing hierarchies, namely the legal superiority of Russian Orthodoxy over other confessions and restrictions on Jewish freedoms. The Russian authorities rarely objected to conversions of Sunni and Shi‘a Muslims, Yazidis, and Assyrians to Armenian Christianity because they did not upset the social order or threaten tsarist rule in the Caucasus. Paul W. Werth argued that, in the case of mass conversions, particularly out of Russian Orthodoxy, the late imperial state “construed religious status as a matter of communal affiliation rather than individual belief.”Footnote 93 Yet, in the case of individual conversions of non-Orthodox subjects the Russian government endorsed individual belief as the basis of one's religious identity, theoretically inching closer to the elusive freedom of conscience for the tsar's subjects. At the same time, by evaluating the sincerity of petitioners’ spiritual transformations, the state redefined its relationship with the church, mosque, and synagogue. The government wielded the power to determine which conversions were voluntary, in good faith, and legitimate and ultimately held the keys to the gates into every confession.

In the late imperial era, a Muslim's or a Jew's conversion to Armenian Christianity remained a possibility in Russia's heterogeneous South Caucasus provinces. These conversions, especially of Muslims, challenged the emerging sectarian order in the Russian and Ottoman empires, wherein religious identity became linked to notions of loyalty and citizenship in a Christian or a Muslim state. In the same way, conversions of Turkic speakers to Armenian Christianity countered the ethno-national lines that were slowly being drawn on the ground. The Armenian-Azerbaijani clashes, which started in Baku in 1905 and spread across the South Caucasus, were among the worst massacres in late tsarist history. In the Ottoman east, Armenians were locked in an escalating conflict with local Kurds and Turks. Voluntary conversions hardly seem to fit into this history of intercommunal violence, which reared the nation-states of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey.Footnote 94

Religious conversions, nevertheless, aided the transition from an imperial to a national order. They reinforced the ethno-religious sorting, or “unmixing of people,” in the Eurasian borderlands. Conversions, massacres, and expulsions were part of the same drive for homogeneity at the twilight of the empire. Notably, conversions in this story were not a state-driven endeavor, but a grassroots process, wherein Muslim and Yazidi shepherds made their bet to join the largest Christian church in the South Caucasus. Their journey to becoming Armenian was not easy, and we know precious little about the emotional and social toll it took. In the twentieth century, their conversions fell by the wayside of national drives for ethnic purity. Armenians who had once been Kurds and Tatars hardly belonged in the post-genocide Armenian national narrative, nor could they be part of proud histories of the newly articulated Azerbaijani, Turkish, and Kurdish nations. Their conversions became impossible to fathom in a more rigid and less forgiving age.