Introduction

This study examines why Japan was slow compared to other countries to implement a value-added tax (VAT). A VAT is a tax system that supports a welfare state. Comparative studies have focused on the relationship between tax policy and social spending, and have revealed that the most solidaristic welfare states, which have succeeded in reducing poverty, rely most heavily on regressive taxation (Beramendi and Rueda Reference Beramendi and Rueda2007; Kato Reference Kato2003; Martin and Prasad Reference Martin and Prasad2014; Prasad and Deng Reference Prasad and Deng2009; Sekiguchi Reference Sekiguchi2017; Steinmo Reference Steinmo1993). Based on this, research on the relationship between the size of welfare state expenditures and VATs has highlighted the significance of timing the VAT introduction (Kato Reference Kato2003; Martin and Prasad Reference Martin and Prasad2014; Sekiguchi Reference Sekiguchi2017; Steinmo Reference Steinmo1993). Studies indicate that there are two sides to this relationship between VAT and the welfare state. A VAT with stable tax revenues can expand social security; increasing the size of a VAT, which imposes a regressive burden, requires expanding social security. In simpler terms, countries that introduced VATs in the early stages of developing a welfare state were able to maintain large social security systems in the twenty-first century (Kato Reference Kato2003; Sekiguchi Reference Sekiguchi2017). Japan, which introduced a VAT later than the European Union countries did, had a smaller government (Takahashi Reference Takahashi2021, Reference Takahashi2022; Kato Reference Kato2003; Sekiguchi Reference Sekiguchi2017).Footnote 1

However, until the 1990s, unlike member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Japan was able to achieve income equality while maintaining a small government (Takahashi Reference Takahashi2021, Reference Takahashi2022; Estevez-Abe Reference Estevez-Abe2008; Ide and Steinmo Reference Ide, Steinmo, William Martin, Mehotra and Prasad2009). This achievement was related to the concept of a tax-welfare mix (Park and Ide Reference Park and Ide2014). First, Japan established a formal welfare state. Although the universal health insurance and pension systems were established in 1960, their expenditures were deliberately kept low, and the government promoted private welfare provision through firms and families. Second, the Japanese government maintained low tax rates and implemented a redistributive tax policy that focused on direct taxes while cutting taxes to distribute profit. The government considered lowering the tax rates as part of the social security system and continually reduced its income tax rates throughout the 1960s. It created targeted and preferential tax measures to reduce tax burdens for groups that were considered left behind by Japan’s economic development, such as farmers and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the groups that formed the core of the ruling party’s social coalition (Akaishi Reference Akaishi2005). This tax cut was agreed upon not only by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) but also by the opposition parties.Footnote 2 Third, the Japanese government engaged in redistributive public investment, redistributing resources, and creating regional employment (Dewit and Steinmo Reference Dewit and Steinmo2002; Park Reference Park2011). This public works investment reduced the fiscal burden by utilizing the Fiscal Investment and Loan Program, which was an off-budget system (Park Reference Park2011). These three factors allowed Japan to enjoy low inequality from the post-war period to the 1960s, despite its small government. Japan’s fiscal policy was path-dependent on this tax-welfare mix, which highlights why the VAT introduction was pushed back (Park and Ide Reference Park and Ide2014).

However, discussions about the need to introduce a VAT in Japan began in the 1960s and became a political agenda in the 1970s. At that time, there were several logical reasons to consider introducing the VAT. First, Japan was faced with increasing foreign influence, as Western European countries began successively introducing VATs between the 1960s and early 1970s; this increased the momentum to introduce the tax in Japan. Second, the VAT was intended for fiscal restructuring. Japan had issued construction bonds in 1966 and began to regularly issue deficit bonds in 1975. This created an urgent need to address the nation’s budget deficit, and introducing a VAT was proposed as a possible solution. Third, using the logic that a high welfare burden was necessary to pay for high welfare, the Japanese government and Ministry of Finance (MOF) established a “high benefit/high cost” policy to explore the possibility of raising taxes. This shows that Japan, as a small government, could have taken a different path at the outset than previous studies have assumed.Footnote 3

In this setting, the government internally debated introducing a VAT, and by the late 1970s, it was on the political agenda. However, the VAT was not introduced until 1989, creating a political setback for the government. Therefore, I analyze the failure to introduce VAT in Japan from the 1960s to the 1970s and examine the reasons for the delayed introduction compared to other countries.

Previous studies have focused primarily on the failed consumption tax introduction during the Ohira administration in the 1970s. Kato (Reference Kato1997) concentrated on the actors involved in the policy-making process, examining the MOF’s behavior and its limited rationality within the internal rules (system and culture). Others have scrutinized the Tax Commission and analyzed Japan’s tax policy (Ishi Reference Ishi2008) or have chosen to highlight interest groups’ resistance rather than the VAT implementation process (Ide Reference Ide, Huerlimann and Elliot2018; Iwasaki Reference Iwasaki2013; Park and Ide Reference Park and Ide2014). Therefore, a significant amount of research exists on the planning and decision-making stages of VAT policy formation.

However, these studies do not fully explain why the MOF ultimately decided to introduce the VAT. As previous research has pointed out, from the time of Shoup’s recommendations through the 1960s, the MOF’s Taxation Bureau supported a direct tax system and resisted introducing a new indirect tax, while the LDP supported both centering on a direct tax and income tax reduction (Kidera Reference Kidera2016; Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006; Sekiguchi Reference Sekiguchi2017). It is unclear why support for this direct tax system changed to support for a VAT.

To reveal the relationship between the changes in the ideology of centering on a direct tax and the introduction of VAT which have been overlooked by previous studies, this study focuses on the changes in the tax philosophy of the MOF. Both the debates it engaged in over introducing a VAT in the 1960s and 1970s and its eventual failure are analyzed focusing on the Tax Commission’s materials.Footnote 4 The drafts of the Tax Commission’s reports from the 1960s to the 1970s were written by Tax Bureau bureaucrats and are considered to reflect their thinking (Mabuchi Reference Mabuchi1989: 44).Footnote 5 The agenda for Tax Commission discussions was also set by Tax Bureau bureaucrats. Nevertheless, not all of their ideas coincided with those that emerged from the Tax Commission’s reports (Kidera Reference Kidera2016). Japan’s Tax Commission, unlike those in the West, focuses on establishing compromises among the diverse interests represented by its members and is said to be highly likely to implement policy changes (Ishi Reference Ishi1989: 13; Kato Reference Kato1997: 99). Thus, scrutinizing the Tax Commission’s materials is important when examining Japan’s tax policy. My study analyzes the Tax Bureau bureaucrats’ views on the VAT by referring to the Tax Commission’s reports and stenographic records (Table 1) and by examining the documents and oral histories produced by the Tax Bureau bureaucrats of that time.

Table 1. Reports issued and officials who held important positions during the period covered by this study

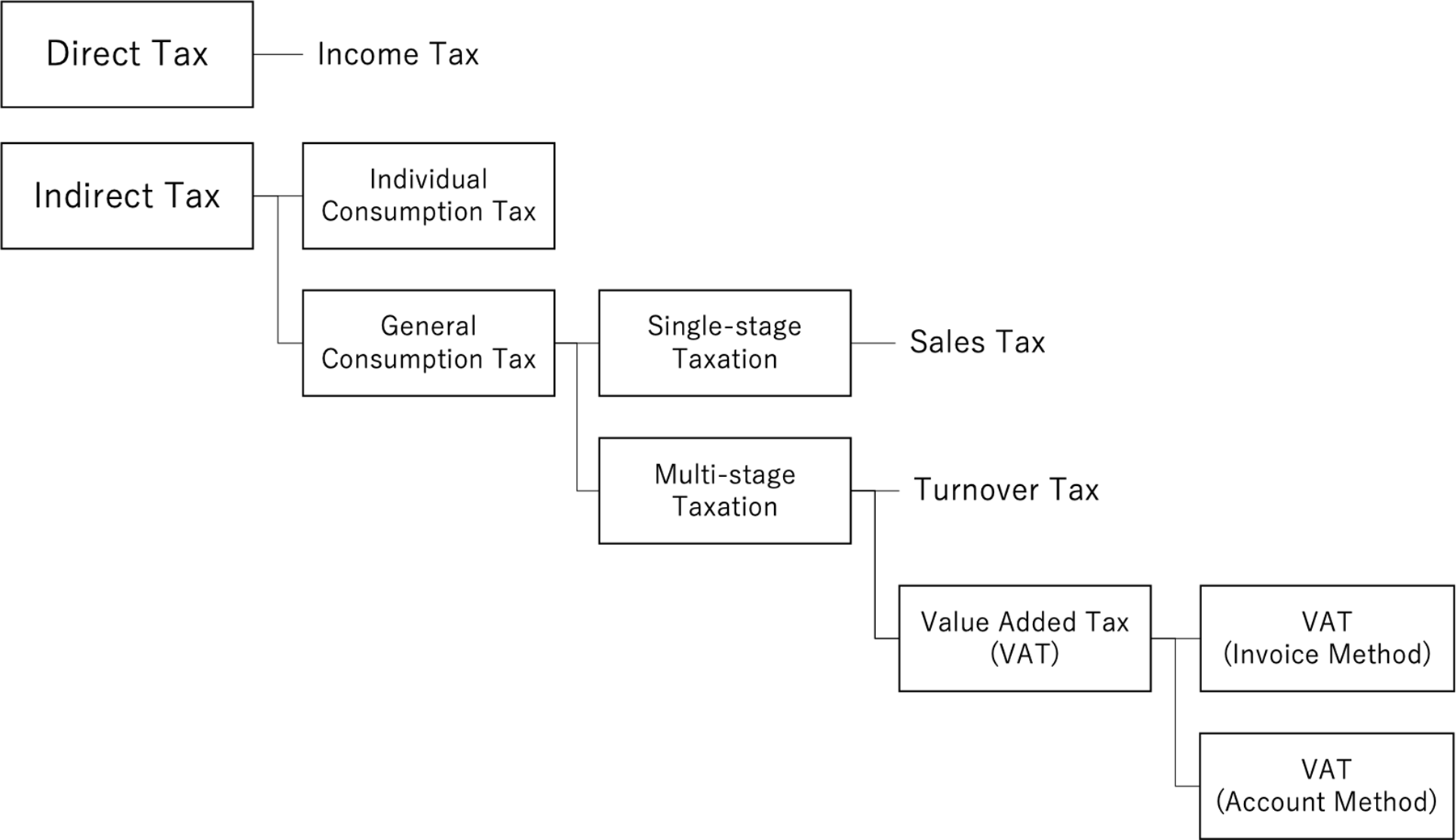

In Japan, the term VAT was sometimes discussed as a sales tax or general consumption tax, depending on the period. These terms are strictly different concepts (Figure 1), but they are treated together in this study, as they have led to the introduction of VAT.Footnote 6

Figure 1. Placement of value-added tax in the Japanese tax system.

Source: Created by the author based on Kamakura (Reference Kamakura2018: 7).

Why was a VAT not on the agenda?

Shoup’s recommendations and the ideology centering on a direct tax

It is essential to examine the reasons that the VAT was not on Japan’s agenda before the 1970s. Japan’s initial tax-revenue structure was not primarily based on direct taxes; before 1937, it had a larger proportion of indirect than direct taxes. During the war, although Japan increased the direct tax amount by raising income taxes, this did not mean that it adopted “the ideology centering on a direct tax,” as it did later. A sales tax was considered in the 1937 Baba tax reform (Sato Reference Sato1979),Footnote 7 and the turnover tax was introduced after the war, showing that Japan could tolerate increasing indirect taxes.Footnote 8 However, this situation dramatically shifted with the 1949 and 1950 recommendations of the Shoup Tax Delegation, which was headed by the American economist, Carl Shoup.Footnote 9

In the preface to his recommendations, Shoup wrote, “We could have recommended a rather primitive type of tax system, one which would depend on external signs of income and wealth and business activity, not on carefully kept records and intelligent analysis of difficult problems” (Report on Japanese Taxation by the Shoup Mission Volume I and IV 1949: 1). This suggested that size-based business taxation systems centered on indirect taxation were immature tax systems. Shoup further stated, “such a system could raise the required revenue, but it would perpetuate gross inequities among taxpayers, dull the sense of civic responsibility, keep the local governmental units in an uneasy financial dependence on the national government, and give rise to undesired economic effects on production and distribution” (ibid.: 1).

Meanwhile, income tax was described as follows:

Moreover, we soon became convinced that the current difficulties in obtaining fair and efficient administration of the tax laws and a high degree of compliance by the taxpayer in Japan need not be taken as inevitable. Our aim, therefore, has been to recommend a modern system which depends upon the willingness of businessmen and all taxpayers of substantial means to keep books and to reason carefully about some fairly complicated issues of equity (ibid.: 1).

Thus, the ideology centering on a direct tax was set forth by regarding an indirect tax system as infantile and income tax as a modern system (Kidera Reference Kidera2016: 42). In fact, this recommendation suggested abolishing the turnover tax (Okurasho Zaisei Shishitsu Reference Okurasho1977).Footnote 10 The ideology centering on a direct tax, as in Shoup’s recommendations, was largely realized in the 1950 tax reform.

Nevertheless, the ideology in Shoup’s recommendations does not define the Japanese tax system.Footnote 11 In fact, this ideology became a central idea only when the Tax Bureau internalized it.

Jun Shiozaki, a prominent Tax Bureau bureaucrat, held various influential positions, including Manager of the Income Tax and Property Tax Policy Division from 1956 to 1961; Manager of the Planning and Administration Division, the first of the newly established divisions; and finally, Director-General of the Tax Bureau for two years, from 1965 to 1967. He, along with other MOF bureaucrats, was exposed to Richard Goode’s tax theory through translations of his books, including The Corporation Income Tax and The Individual Income Tax. The Tax Bureau understood Goode’s tax theory as follows:

The report lists income, consumption, and assets as the three tax bases for personal taxation and analyzes them from the perspective of addressing ability to pay, reducing economic inequality, and enforceability. It concludes that personal income appears to be the best and only indicator of tax-bearing capacity and the best and only basis for progressive taxation.

Goode’s theoretical system praised a personal income tax as a progressive taxation system and the best taxation form (Kidera Reference Kidera2016: 20; Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006: 20–22). In addition, this system did not expect much from indirect taxation (Kidera Reference Kidera2016: 20; Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006: 20–23). Shiozaki’s understanding of the tax system was almost the same as that of Richard Goode; the Tax Bureau’s thinking between 1950 and early 1960 was in line with Shiozaki’s, and by extension, close to Goode’s ideas (Kidera Reference Kidera2016: 20; Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006: 23). Thus, Shoup’s recommendations were supported by the Tax Bureau, which oversaw taxation, and changed the Japanese tax system to center on direct taxes.

The VAT’s position in the Tax Bureau’s logic

Adopting the ideology centering on a direct tax does not imply that the VAT was not considered. There is historical evidence that the issue of a VAT was raised but was blocked from being discussed. The logic behind this blocking was as follows. Introducing a general consumption tax was discussed in the Tax Commission’s so-called long-term report every three years. However, a general consumption tax was not introduced in the Tax Commission’s final 1961 report for three reasons. First, specific consumption taxes were superior to a general consumption tax. A general consumption tax “may be alleviated to a considerable extent through technical considerations, such as the selection of taxable items and establishment of tax exemption points; however, there are natural limits to the extent to which this can be done, and it is unlikely that the essential nature of the tax can be changed” (The Tax Commission 1961: 77–79). However, specific consumption taxes were considered to have “a very limited taxable base and detailed consideration is given to tax rates, exemption points, etc. from the perspective of tax-bearing capacity” (ibid.: 82). Taxpayer consumption taxes were less regressive than a general consumption tax. In terms of tax theory, specific consumption taxes were determined to be superior to a general consumption tax in terms of burden fairness.

Second, from the perspective of fiscal demand, a significant automatic increase in revenues led the Tax Commission to conclude that “there is no need, at least for the time being, to secure financial resources through by establishing new taxes, regardless of the tax category” (ibid.: 79–82).

The third reason was the rebuttal of foreign cases. Referring to other countries’ general consumption taxes, the report postulated that once the public embraced these taxes, it would become virtually impossible to locate an alternative source of revenue, rendering it a reliable and stable source of income (ibid.: 77–79). This subjective evaluation suggested that the general consumption tax’s popularity was not derived from a systematic assessment of the tax system, but rather from its reliability as a stable source of revenue.

Therefore, the commission stated, “We have concluded that, unless a special financial need arises in the future, it is more reasonable for Japan’s tax system to have a direct tax at the centre and specific consumption taxes in addition to the sales tax” (ibid.: 79–83). In other words, the possibility of introducing a general consumption tax was rejected for three reasons: (1) the superiority of specific consumption taxes, (2) the fiscal demand perspective, and (3) refutation of foreign cases (Okurasho Zaiseishi Shitsu Reference Okurasho1990a: 444; The Tax Commission 1961: 76–93).

In the 1964 long-term report, export promotion was used as the rationale for introducing a general consumption tax. It was suggested that exports can be encouraged by reducing corporate taxes, promoting capital accumulation, and utilizing the export refund system’s sales tax. The Tax Commission took a negative position because this would have characterized the general consumption tax as a special tax. In addition, specific consumption taxes’ superiority and refutation of foreign cases were still relevant – both of which were pointed out at the time of the 1961 report (The Tax Commission 1964).

Although the Tax Bureau and Tax Commission had consistently taken negative stances toward introducing a VAT, a political movement in favor of a VAT as a new revenue source began to emerge in the late 1960s. Mikio Mizuta, who was the Minister of Finance at that time, wanted to reduce or abolish the corporate income tax and create a sales tax as a source of revenue (Okurasho Zaiseishi Shitsu Reference Okurasho1990a: 446).

The Finance Minister Mizuta’s position was distinct from that held by the Tax Commission and Tax Bureau. In response, on October 20, 1967, the Tax Commission presented a six-point proposal, titled “The Pros and Cons of Establishing a General Sales Tax,” to consider the following questions: (1) What is the purpose of establishing a sales tax? (2) What considerations should be made for companies that cannot pass the burden on to consumers? (3) What should be considered regarding the VAT system? (4) What are its advantages and disadvantages compared to a specific consumption tax system? (5) What tax exemption point should be considered? (6) How is the cost of tax collection estimated? The intent was to enumerate the difficulties that would arise in introducing a general consumption tax and to prevent its introduction (Okurasho Zaiseishi Shitsu Reference Okurasho1990a: 448). In response to these issues, the Tax Commission’s 1968 Report on the Long-Term Tax System concluded that the time was not right to introduce a general consumption tax and dismissed the issue (The Tax Commission 1968b: 448).

I reviewed the Tax Bureau’s attitude toward a VAT based on the Tax Commission’s long-term report. Until the late 1960s, the bureau opposed introducing a VAT because specific consumption taxes were superior to a VAT and because of the period’s fiscal demands. Both the 1961 and 1964 reports indicated that specific consumption taxes should be reduced, but there was never any momentum to increase the indirect taxes (The Tax Commission 1964). However, in 1968, the “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” changed the attitude toward indirect taxes.

Tax Bureau’s acceptance of increases in indirect tax

“Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” and budgeting in 1968

“Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” started in 1967 (Campbell and Scheiner Reference Campbell and Scheiner2008). The long-term trend of increasing obligatory expenses was considered to have contributed to the annual budget growth. Therefore, to break fiscal rigidification, the intent was to revert to the systematic practice of using an expenditure budget and checking its content (Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006, 45-47).Footnote 12 During the 1967 “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign”, indirect taxes were increased to compensate for cuts in income taxes. Examining the framework of the income tax cut initiated by the Tax Bureau is useful for considering this process.

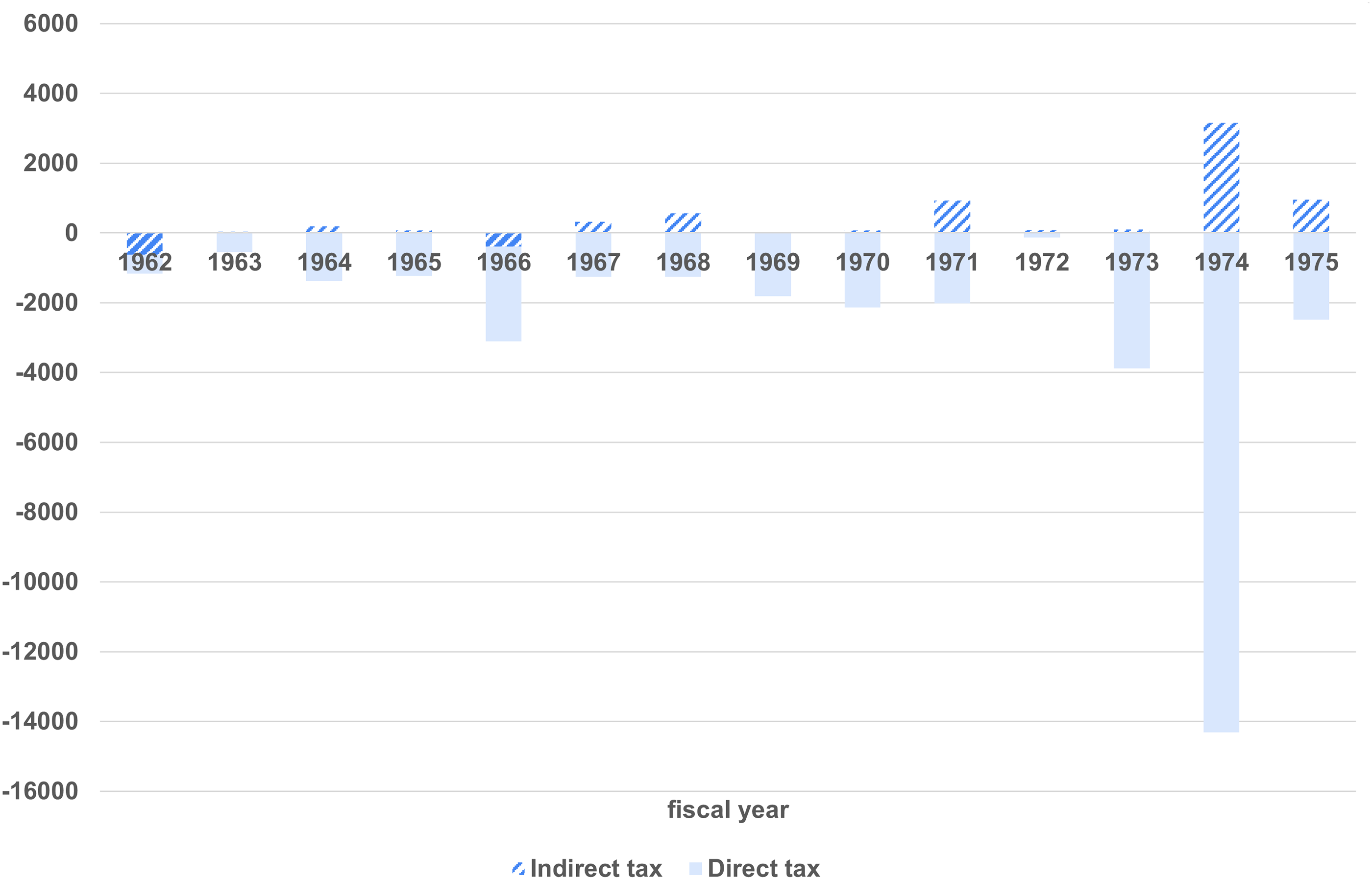

Although the Tax Bureau supported the ideology centering on a direct tax, it resisted high-income tax rates. Instead, it actively reduced income taxes between 1950 and early 1970. Consequently, personal income tax burdens rose slightly during the rapid economic growth of the 1950s and early 1970s (Figure 2) (Muramatsu Reference Muramatsu2011).

Figure 2. Changes in indirect and direct tax revenues due to tax reform (1962–1975).

Source: Okurasho Zaiseishi Shitsu (Reference Okurasho1990a: 423).

Unit: 100 million yen.

Underlying the income tax cut was the rule in The Income Doubling Plan Footnote 13 requiring that the tax burden to national income ratio equal 20 percent.Footnote 14 This rule established (1) a time frame where the tax burden rate was set at 20.5 percent in the first half of the plan year and 21.05 percent in the target year and (2) an automatic tax cut that held the tax burden rate constant, while half of the natural revenue growth above a certain rate was used to reduce taxes. The ideology centering on a direct tax and 20 percent tax burden rule, which automatically reduced income taxes, comprised institutional arrangements based on the assumption that tax revenue would automatically increase given Japan’s fiscal situation at the time, which was based on a balanced budget.

However, bond issuance in the 1965 fiscal year forced modification of these institutional arrangements. The logic that a certain percentage of the natural increase in revenues could be used to reduce taxes because a balanced budget could be maintained even with tax cuts was rejected. Consequently, the Tax Bureau had to search for a new tax reduction rationale.

Meanwhile, the MOF’s Budget Bureau wanted to reduce the level of dependence on public debt (Okurasho Zaiseishi Shitsu Reference Okurasho1997). There are two ways to accomplish this: reduce expenditures or increase revenues. Of these two methods, the Budget Bureau adopted an inflexible fiscal policy to reduce expenditures. Fiscal rigidification takes two forms: expenditure rigidification and revenue rigidification. Expenditure rigidification refers to the inability to “flexibly control expansionary pressures in response to economic conditions,” based on the assumption that a welfare state is characterized by strong fiscal expansionary pressures (Okurasho Zaiseishi Shitsu Reference Okurasho1990b: 326). Revenue rigidification refers to a situation in which “it would be desirable if defined expenditures had the elasticity to offset expansionary pressures, but rigidification in public finances usually also lack this condition” (Murakami Reference Murakami1977: 130).

The “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” also included income tax cuts. Kotaro Murakami, the Director-General of the MOF’s Budget Bureau, emphasized that Japan was fiscally too small by international standards; however, he also considered “the direction of hasty reductions in tax burdens in the future to be problematic” (Kato Reference Kato1982: 39). Thus, there was a conflict between the Tax Bureau’s income tax cut and the Budget Bureau’s maintenance of fiscal discipline.

Changes in the status of indirect taxes

The “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” and conflict between the Budget Commission and Tax Bureau over income tax cuts forced the Tax Bureau to revise the ideology centering on a direct tax. The council’s budget report for fiscal 1968 was issued before the Tax Commission’s report. This meant that the government bond issuance amount was presented first, thereby limiting tax reform (Kato Reference Kato1999: 126). Simultaneously, Prime Minister Eisaku Sato also believed that reducing government bond issuances should be prioritized over income tax cuts (Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006: 80). In response, the Tax Commission’s Report on Tax Reform in 1968, issued on December 27, 1967, cut income taxes by increasing the specific consumption taxes on alcohol and cigarettes. Given the public debt issuance, the Tax Bureau required the tax-revenue-neutral fiscal policy of reducing income taxes and increasing indirect taxes as a move to break fiscal rigidification (The Tax Commission 1967).

The Tax Bureau was aware that the “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” was aimed at such a fiscal policy. As Mizuno Masaru,Footnote 15 Deputy Director of the Planning and Administration Division, Tax Bureau, MOF, recalls, “Toward the end of October, a mood was developing in the MOF that tax cuts would not be tolerated in fiscal 1968.” He also recollects, “it was necessary to review the rigid spending, but this could not be accomplished overnight. We had no choice but to ask the government to be patient and cut taxes.” Thus, the spearhead of “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” was pointed at the Tax Bureau (Ide Reference Ide2017; Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006). This idea of tax-revenue neutrality paved the way for increasing indirect taxes following the ideology centering on a direct tax (Kidera Reference Kidera2016).

Meanwhile, the Tax Bureau remained critical of the VAT. In July 1968, during the “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign,” the Tax Commission’s Report on the Long-Term Taxation System stated that the time was not yet ripe to create a general consumption tax, although discussing its purpose was necessary. The report also stated that, based on the past failure to introduce a turnover tax, “it is necessary to keep in mind that there is still strong emotional opposition to a VAT among various segments of the population.” Regarding the form of the general consumption tax, the report said, “There is an opinion that the value-added tax in the form of a front-loaded tax credit system has comparatively fewer shortcomings, such as the lack of progressive effects, but all forms, including this one, have their advantages and disadvantages.” The report also mentioned that specific and general consumption taxes should be compared, noting that specific consumption taxes were superior to a general consumption tax, since the tax rate could reflect each item’s tax-bearing capacity. Footnote 16 Finally, the report stated, “In light of the fact that there is still considerable room for improvement in the current system, it is recognized that establishing a general sales tax, etc., should not be planned for the time being.” It concluded by stating that the specific consumption tax overhaul should come first in revising indirect taxes rather than creating a general consumption tax (Okurasho Zaiseishi Shitsu Reference Okurasho1990a: 448).

Thus, although the argument that natural revenue growth could compensate for fiscal demand through bond issuance and “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” had disappeared, the negative memory of the turnover tax, regressive nature of a VAT, and superiority of individual consumption taxes over a VAT led to the conclusion that individual consumption taxes should be increased instead of introducing a VAT.

To summarize, the Tax Bureau’s tax system was based on the ideology centering on a direct tax combined with income tax reductions based on assuming a natural increase in revenues. However, the Tax Bureau’s premise was destroyed by the 1965 issuance of government bonds. Although VAT introduction was discussed during this time, the bureau opposed this reform because of the difficult process. In addition, a VAT’s regressive nature and the superiority of specific consumption taxes also made it challenging to introduce a VAT. Later, the Tax Bureau changed its position in favor of tax–revenue neutrality to promote an increase in indirect taxes and reduce income taxes. The following section examines why and how the Tax Bureau, which originally opposed introducing a VAT, changed its stance.

How was a VAT determined to be superior?

The European-Commission (EC)-type VAT

Two issues had to be resolved before the Tax Bureau could introduce a VAT. The first was formulating the logic for increasing indirect taxes. As previously discussed, the “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” called for increasing indirect taxes in exchange for larger income tax cuts. The Tax Bureau’s acceptance of this was a step toward introducing a VAT. The second was formulating the logic of a VAT’s superiority over specific consumption taxes. The 1961 final report and the 1964 and 1968 long-term reports argued that specific consumption taxes were superior to a general consumption tax because they were more finely tuned under the criterion of “fairness of burden.” It was impossible to introduce a VAT without changing this perspective.

Throughout the 1960s, the Tax Bureau maintained that income taxes, with their progressive structure, were capable of raising revenue and redistributing income. Further, it maintained that income taxes should be the tax system’s core and that there was no need to consider improving consumption taxation (Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006:103–106).Footnote 17 How did the Tax Bureau’s reasoning change? The bureau’s position change can be traced to the Fundamental Issues Subcommittee of the Tax Commission, which met from July 24 to October 30, 1970, and to the EC-type VAT survey conducted by subcommittee members.

In the 1970s, partly due to the rise of progressive local government and opposition parties, the government’s goals gradually shifted from measures focused on economic growth to enhancing welfare and social overhead capital.Footnote 18 One of the triggers for this “high welfare” course was the “New Economic and Social Development Program” established in 1970 (Takahashi Reference Takahashi2019).Footnote 19 The Fundamental Issues Subcommittee of the Tax Commission proposed a “high benefit/high cost” policy line. Since it would be difficult to secure financial resources from income taxes alone under “high cost” conditions, the subcommittee proposed to revise or increase indirect taxes (Takagi Reference Beramendi and Rueda1980: 10–11). Furthermore, the then Minister of Finance requested that the subcommittee deliberate about introducing a VAT (The Tax Commission 1970a).

On June 19, 1970, at the 15th general meeting of the Tax Commission, Okura Masataka, the director of the Planning and Administration Division of the Tax Bureau, requested deliberation on indirect taxation. Okura gave four reasons for his request: (1) the Tax Commission had received this request from Fukuda Takeo, the Minister of Finance; (2) the LDP held a strong opinion that future fiscal demand should be met by indirect taxationFootnote 20 ; (3) some in the business community thought that a VAT should be considered from the perspective of border tax adjustments; and (4) an opinion was gradually forming that it was time to adopt the continental European-type VAT in Japan. Thus, the ruling party demanded that a VAT be re-examined. Okura then told the Tax Commission, “the most fundamental issue is how to think about the future indirect tax burden and its system.” The later discussion of indirect taxation included: (1) whether to consider the ratio of direct to indirect taxes, (2) whether to consider individual taxes, and (3) which was better in terms of income distribution effects and economic adjustment measures: individual consumption taxes, a general sales tax, or a value-added tax (The Tax Commission 1970a). These issues were discussed, and a European-Economic-Community (EEC)-type VAT was investigated by the Fundamental Issues Subcommittee of the Tax Commission (The Tax Commission 1970b).

The EEC-type VAT study was conducted from mid-September to late October 1970 by the Fundamental Issues Subcommittee members Kazuo Kinoshita, Ryuichiro Tachi, and Keimei Kaizuka,Footnote 21 all of whom favored a direct tax. Footnote 22 Since ordinary people’s bias against introducing a massive or regressive indirect tax (Kinoshita Reference Kinoshita1992: 50–51) was well known, the Tax Bureau conducted a field survey of EEC member countries (ibid.: 73–75).

Two significant conclusions were drawn from this field survey; Footnote 23 the first was regressivity. Kinoshita explained, “according to the EC Secretariat, based on surveys of the actual situations in France and the Netherlands, the regressivity of value-added taxes is not considered particularly noteworthy.” Furthermore, following an explanation by Philippe Rouvillois of the French Ministry of Finance, “if an unacceptably regressive burden is introduced, it is possible to take corresponding measures by adjusting other tax items” (ibid.: 58).

Second, there was a gap between taxation theory and reality. In France, income taxation was not necessarily fair; however, indirect taxes like consumption taxes were still considered fairer. In response to this, Kinoshita stated the following:

No matter how good taxation is in theory, it should never be recommended if it does not work in reality. Of course, the failure of an ideal taxation system to function effectively in practice may be based on some institutional defect. However, even if this flaw is eliminated, effective functioning is still hindered by tax administration restrictions. For example, the difficulty of capturing employment income is not unique to Japan but is an unavoidable problem in all countries, regardless of the degree of difficulty. Behind this situation lie various factors based on each country’s political and social background (ibid.: 74).

This rationale was reflected in the discussion of the VAT’s regressive nature included in the 1971 long-term report.

Changing logic regarding VAT valuation

A discussion of the EEC-type VAT study was included in the Fundamental Issues Subcommittee report, which argued for an increase in consumption taxation rather than income taxation. It pointed out that although income taxation “aggregates income at the individual level and can tax it by applying a progressive tax rate after taking into account various personal deductions and other individual considerations,” it is based on the assumption that there are no institutional or enforcement deficiencies. The report then highlighted that there were measures such as tax exemptions and reductions; it was difficult to ascertain income in terms of enforcement, and discrimination could occur in individual burdens, both institutionally and practically. It argued that consumption taxation was practically challenging to apply with individual considerations and progressive taxation. Consequently, nondiscriminatory taxation was implemented instead, without any significant differences in individual tax burdens. It concluded, “vertical and horizontal fairness can be ensured through a moderate combination of the income tax and consumption tax, and that substantial fairness can be achieved.” The regressive nature of consumption taxes can be adjusted not only by strengthening the income tax’s progressive structure and optimizing asset income taxation but also by strengthening the income redistribution functions of social security and other expenditures (The Tax Commission 1971: 107). This was a positive consumption tax evaluation that contrasted with a tax system with the ideology centering on a direct tax.

The remaining issue was comparing specific consumption taxes to a general consumption tax. The report pointed out that the specific consumption tax operation had become rigid due to consumption’s increasing sophistication and volume and the individual interests of each industry involved. A general consumption tax was presented as a counterpart to specific consumption taxes. However, since a general consumption tax would significantly impact Japan’s tax system, the report iterated, “careful consideration should be given to whether or not to introduce the tax and the specific form of taxation, taking into account its relationship with other taxes such as income and corporate taxes.” The conclusion was that “the taxpayer must carefully consider the possibility of introduction and the choice of the specific form of taxation, taking into account the relationship with other taxes such as income tax and corporate tax” (The Tax Commission 1971: 108). Thus, the ideology centering on a direct tax, which Shoup recommended as ideal, had undergone a major change (Okurasho Zaiseishi Shitsu Reference Okurasho1990a: 441).

The content discussed in the Fundamental Issues Subcommittee report was published almost verbatim in the 1971 long-term report. This report deepened the VAT discussion in four ways. Footnote 24 First, it clearly stated the high-benefit/high-cost path that was a prerequisite for introducing a VAT. The report noted that while Japan’s tax burden had been gradually increasing since the beginning of 1965, “such a transition in the tax burden is acceptable, given the considerable increase in income levels, the demand for increased public investment, social security, and other fiscal demands, and the fact that the tax burden rate is low compared to those of Western countries.” In addition, the high-benefit/high-cost policy line was adopted, stating that high welfare required a high tax burden, and “if the economic situation is to remain the same in the future, it is appropriate to consider the tax burden in accordance with the above direction.” Footnote 25

Second, the conventional opinion that specific consumption taxes were superior was revised. According to the report, a specific consumption tax “is not necessarily taxed in accordance with the tax-bearing capacity of consumption if the selection of taxable items is arbitrary due to the difficulty obtaining objective criteria and if the tax does not adapt to the diversification and upgrading of people’s consumption in accordance with changes in the times.” It cannot be denied that when a person’s consumption structure is rapidly changing and becoming more complex, general consumption taxes, compared with specific consumption taxes, can create a tax burden according to the consumption mode. This is because specific consumption taxes are not imposed on consumption (The Tax Commission 1971: 65). Furthermore, a specific consumption tax is not neutral to competition among industries, whereas a general consumption tax is (ibid.: 19). Thus, the idea in the 1968 Report on the Long-Term Taxation System that specific consumption taxes were superior to general consumption taxes was modified to suggest that general consumption taxes might be preferable in the context of national consumption structure changes.

Third, the report failed to acknowledge the regressive nature of consumption taxes. Notably, the report advanced the view that savings were subject to depreciation in terms of purchasing power and will, in the long term, eventually be expended on consumption. Consequently, the report posited that a general consumption tax would be proportional rather than regressive (ibid.: 65). This argument trivialized the regressive nature of general consumption taxes.

Fourth, the 1971 long-term report suggested that an EEC-type VAT was the best form of a general consumption tax. However, it pointed out the difficulties of obtaining taxpayer endorsement when introducing a VAT and the difficulties of enforcing a VAT in Japan, which is home to many SMEs (ibid.: 19). Furthermore, the VAT systems of Western European countries are based on those countries’ economic structures and business practices; if they were applied to Japan as is, they might be difficult for taxpayers to understand. They might not necessarily fit Japan’s actual economic situation and transactions (Kinoshita Reference Kinoshita1992: 91–93).

Based on this discussion, the report concluded,

In the future, it is not impossible to say that there will be a need for a considerable increase in financial resources for drastic expansion of the social security system and the epoch-making enhancement of social infrastructure to realize a more affluent life for the people. In such a case, various directions will be considered, such as reducing income tax cuts and further increasing reliance on income tax or seeking a considerable increase in the corporate tax burden. When it comes to enhancing indirect taxes, the general consumption tax will likely be taken up as an issue. Which of these various methods will be adopted will ultimately be a matter of choice for the people at that time (The Tax Commission 1971: 66).

The report laid the groundwork for introducing a general consumption tax using the high-benefit/high-cost approach and created a rationale for increasing indirect taxes. It also indicated that a general consumption tax was preferable to specific consumption taxes.

Thus, the possibility of introducing a VAT arose in the early 1970s. However, the subsequent Nixon and oil shocks prevented the high-benefit/high-cost approach from becoming a policy objective. In 1975, the fiscal situation worsened due to public bond issuance, and introducing a VAT became an agenda item again.

Fiscal consolidation and a VAT

Growing momentum for VAT introduction

In 1975, due to a revenue emergency, the Japanese government issued special public bonds, which shifted the Tax Bureau’s opinion about introducing a VAT to cover the budget deficit. According to Mizuno, who was a member of the Tax Bureau, between 1955 and 1965, the Tax Bureau’s job was to determine how much of the automatic increase in revenue could be allocated to tax cuts. However, after the bond issuance, tax reform’s basic direction was increasing revenue, particularly through large rather than small tax increases (Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006: 173–182); thus, a VAT once again became part of the fiscal agenda. Mizuno deemed the 1971 long-term report statement that suggested introducing a general consumption tax to secure financial resources for welfare enhancement or tax reduction as mere postponement of judgment. Mizuno considered a post-1975 scenario wherein a substantial tax revenue increase would be pursued to address the fiscal situation, which had become significantly reliant on government debt, rather than to address a hypothetical increase in fiscal demand, such as welfare enhancement or tax reduction. At that time, the context was not “high benefit/high cost” but rather a VAT tax increase for the fiscal deficit.

This change in the Tax Bureau’s thinking was highlighted in the “Okura Memo” by Masataka Okura, Director-General of the Tax Bureau (Zaimusho Zaimu Sogo Seisaku Kenkyujo Zaiseishishitsu 2003: 36–39). This memo, written during the 1976 tax reform period, contributed to studying the Tax Bureau’s fiscal restructuring methods. The October 1977 Report on the Future Tax System (mid-term report) was based on the “Okura Memo” and examined fiscal reconstruction from a tax system perspective. The mid-term report called for increasing the public’s general tax burden. Its premise was that the national government’s finances were about to violate the 30 percent dependence on public debt rule (Kinoshita Reference Kinoshita1992: 111–112).Footnote 26

The mid-term report proposed increasing the tax burden for two reasons. First, automatic increases in revenue would be insufficient to eliminate the deficit national debt. Based on the scale of expenditures in “Economic Planning in the Early Showa 50s” and the fiscal balance estimates, it was judged that the expected economic growth rate would not allow deficit financing to end. The report further ascertained that the hypothetical scenario of ending deficit financing solely through economic growth would produce substantial inflation and should not be considered a viable solution.

Second, there was a limit to how much spending growth could be reduced. This reasoning was also the basis for the estimates in Economic Planning in the Early Showa 50s. At that time, it was deemed infeasible to achieve a drastic reduction in overall expenditures without significantly compromising the social infrastructure’s planned development and expansion of social security programs, which were seen as necessary to meet the public’s expectations for national welfare improvement. Thus, while prioritizing the objective of upholding a “high welfare” standard, raising the tax burden was deemed necessary to attain fiscal solvency and escape the perils of deficit public debt.

The report also recognized that taxes and social insurance contributions were considerably less in Japan than in other countries and examined the possibility of raising taxes on existing tax items. Relying on the Economic Planning in the Early Showa 50s, the report considered the possible revenue increase required to end dependence on deficit public debt and explored the possibility of raising taxes on individual tax items. International comparisons indicated that income and corporate taxes could potentially accommodate a tax increase. However, increasing the income tax burden was difficult, given the growing momentum for income tax reductions. The slight increase in corporate tax revenue was insufficient to end dependency on deficit financing. This applied to abolishing special tax measures and inheritance taxes. Indirect taxes were also considered a potential source of tax revenue, but expecting a certain amount of revenue increase was not possible within the existing tax system framework (The Tax Commission 1977: 7–16). Thus, the methods for raising revenue were finalized to create a new tax.

Eight new taxes were proposed: increment value duty, wealth, manufacturer’s consumption, EC-type VAT, large-scale sales, large-scale turnover, gambling, and advertising taxes (ibid.: 16–18). The report examined in greater depth three new multi-step taxes – EC-type VAT, large-scale sales tax, and large-scale turnover tax – which were also included in the general consumption tax frameworks. In the subsequent mid-term report, these three new taxes were considered for two reasons: (1) to reduce the administrative burden on small and micro businesses and (2) to eliminate cumulative taxation. The mid-term report, however, only tried to provide a basis for discussion and did not identify which form of general consumption tax should be chosen. Nevertheless, it concluded, “In the end, we will have to face the problem of whether to seek an increase in the general burden of income tax and individual inhabitant tax or introduce a new tax that will require consumption expenditures to be borne by the public at large. The question of which of these two options should be adopted for the future tax system is an important issue for the people to choose.” However, to summarize the study results, the report stated, “there is a limit to seeking an increase in the income tax and individual inhabitant tax burden,” and “as a measure to seek a general increase in the tax burden in the future, it is judged that we must ultimately consider introducing a new tax that would place the burden on consumption expenditures in a broad and general way” (ibid.: 18–21, 26).

The 1978 Tax Reform Report was based on the mid-term report. It discussed the framework for a general consumption tax consistent with the mid-term report’s objectives and called for an early introduction of a general consumption tax by incorporating opinions from various quarters (Zaimusho Zaimu Sogo Seisaku Kenkyujo Zaiseishishitsu 2003: 40–42).

“Outline of general consumption tax” and failure to introduce a VAT

Beginning with the mid-term report, introducing a VAT became a matter of course at the Tax Bureau (Takahashi Reference Takahashi1985: 45). On December 26, 1978, the “Progress Report of the General Consumption Tax Special Subcommittee” was issued for publicity purposes, and the “Outline of General Consumption Tax” was prepared as a summary of these discussions. These reports led to the implementation of the VAT system (Zaimusho Zaimu Sogo Seisaku Kenkyujo Zaiseishishitsu 2003: 47–57).

In the process of preparing the Outline of General Consumption Tax, it was believed that a strong sense of uncertainty and distrust existed among businesses, who initially bear the tax burden, and consumers, who ultimately bear the burden through tax shifting (ibid.: 47–48). Gen Takahashi, Director-General of the Tax Bureau, stated:

Unlike Europe, Japan has many SMEs, and SME organizations, such as the Blue Return Association, are very sensitive to tax issues. To be blunt, there is a strong belief that many SMEs are hiding in terms of income tax. It can, therefore, be speculated that the main reason for their aversion to a new general consumption tax would be the belief that their tax burden will increase (Takahashi Reference Takahashi1985: 46).

Based on this, the accounting method was adopted instead of the invoice method. The accounting method taxes the remainder of sales for a given period and excludes purchases for that period. In addition, by “including the amount of purchases from small and micro businesses that are excluded from tax liability,” purchases from nontaxable taxpayers were also allowed as credits against the purchase tax; thus, preferential measures for small businesses were included. As a measure to benefit consumers, all foodstuffs were exempted from taxation to counteract regressive taxation.

Out of concern for SMEs and consumers, the tax authorities’ plan was to introduce a VAT in the 1979 revision. However, the MOF and LDP failed to reach a consensus (ibid.: 51–53). In fact, the December 27, 1978, LDP Tax Reform Proposal, “Establishment of a General Consumption Tax (tentative name),” stated that various preparations would be made so that the tax could be implemented by the end of the 1980 financial year, a year later than originally planned. Nevertheless, the tax authorities were enthusiastic about introducing a VAT, as indicated by the Cabinet decision on January 19, 1979, “Outline of Tax Reform for Fiscal 1979.” This stated that various preparations would be made so that the general consumption tax (tentative name) could be realized by the end of fiscal year 1980.

However, this plan did not work, as SMEs and various tax administration organizations, including the Blue Return Association, opposed VAT introduction. Furthermore, members of the ruling LDP, which was closely associated with SMEs, opposed the general consumption tax. Jun Shiozaki, a former finance bureaucrat who supported the ideology centering on a direct tax, became a member of the House of Representatives and spearheaded the opposition to the general consumption tax using the failed turnover tax 30 years earlier as an example (Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006: 242–247). Due to resistance from the opposition parties and other groups, like small businessmen, the general consumption tax was shelved during the fall presidential election (ibid.). On December 21, 1979, a “Resolution on Fiscal Restructuring” was adopted stating, “the so-called general consumption tax (tentative name) that has been studied so far has not been well understood by the public in terms of its mechanism, structure, etc.” Therefore, in the fiscal restructuring, the following statement was included in the resolution:

Instead of a general consumption tax (tentative name), the government should first reduce costs through administrative reforms and then increase the number of taxable persons in the age brackets. In the future, fiscal restructuring measures should be considered from a broad perspective, covering both expenditures and revenues, while paying sufficient attention to maintaining the economy and securing employment (Mizuno Reference Mizuno2006: 260).

Consequently, Japan adopted a financial reconstruction plan that involved no tax increases; however, introducing a VAT was postponed until 1989, 10 years after the resolution was adopted.

Conclusion

This study addressed the question of why Japan’s introduction of VAT was delayed compared to other countries, focusing on the relationship between welfare state and VAT (Beramendi and Rueda Reference Beramendi and Rueda2007; Kato Reference Kato2003; Martin and Prasad Reference Martin and Prasad2014; Prasad and Deng Reference Prasad and Deng2009; Sekiguchi Reference Sekiguchi2017; Steinmo Reference Steinmo1993). Japan enjoyed income equality through a tax–welfare mix, despite having a small public social expenditure until the 1990s. Therefore, previous studies have concluded that VAT introduction was relegated to the background (Park and Ide Reference Park and Ide2014).

However, there was a build-up of discussions on VAT introduction within the Japanese government from the 1960s to the 1970s. Based on this, this study clarified why the government attempted and failed to introduce VAT.

There were three barriers to VAT introduction in Japan. The first was creating a rationale for shifting from the ideology centering on a direct tax to accepting indirect taxes. The second was forming a logic that a general consumption tax was better than a specific consumption tax. The third was the logic of tax increase. This study revealed four historical facts related to these barriers.

The first was the ideology centering on a direct tax in the 1960s and the inferiority of a VAT. The Tax Bureau internalized this ideology following Shoup’s recommendations. During this period, The Income Doubling Plan, with its 20 percent tax burden to national income rule, was used to reduce income taxes. Consequently, fiscal demand and the superiority of specific consumption taxes over a VAT were used as grounds to reject a VAT.

The second was the generation of tax–revenue neutrality in 1968. The “Break Fiscal Rigidification Campaign” established a revenue-neutral path by cutting income taxes and increasing indirect taxes. This made it possible to increase indirect taxes, which was difficult in the 1960s. However, instead of introducing a VAT, specific consumption taxes were increased using the 1960s logic.

The third was the conceptualization of “high benefit/high cost” by the Fundamental Issues Subcommittee in the early 1970s, establishing the VAT’s superiority over specific consumption taxes based on a study of overseas travel to EEC countries. Thus, the logic preventing VAT introduction was no longer relevant. Although the possibility of introducing a VAT had increased, the Nixon and oil shocks in the 1970s led to abandoning the “high benefit/high cost” concept, and no VAT was introduced.

The fourth was the link between a VAT and fiscal reconstruction in the late 1970s. The Tax Bureau and Tax Council included incentives for consumers and SMEs, such as adopting an account system and tax exemptions for foodstuffs, to increase the likelihood of VAT adoption. However, it failed because of opposition from consumers, small businesses, and the ruling LDP.

This failure resulted in the adoption of the “Resolution on Fiscal Restructuring” to remove the possibility of tax increases by VAT in the 1980s. In other words, it closed the door to the “high benefit/high cost” type of Western-style welfare state.

My study has two limitations. First, it does not sufficiently analyze the interest groups directly involved in the introduction of the VAT. However, it explains the process by which the Tax Bureau shifted from direct tax centrism and allowed an increase in indirect taxation. It also highlights the discrepancy between the fiscal philosophies of the various interest groups behind the opposition to the VAT. This is proven by the fact that Jun Shiozaki, a member of the House of Representatives, who had internalized direct tax centrism, opposed the introduction of the VAT. However, it is difficult to say whether the taxation ideas held by each group have been clarified.

Second, my study could not analyze the failure of VAT implementation in the 1980s due to space limitations. The study predominately focuses on the literature that recorded the discussions of the Tax Bureau and the Tax Council between the 1960s and 1970s to depict the VAT introduction process. However, this does not mean that the introduction of the VAT was not on the agenda in the period between the “Resolution on Fiscal Reconstruction” in 1979 and its ultimate introduction in 1989. To understand why Japan was slower than other countries to introduce VAT, which was a focus of this study, the failure of the VAT introduction in the 1980s should be analyzed. These two limitations should be addressed in future research.