“We who wander as Jews, and always openly confess that we are Jews through our greeting ‘Shalom’ and our songs, we must pay special attention to our outward appearance. We are not allowed to hike with long trousers, collars, etc. like the many ‘hiking clubs’ that are emerging now, but we have to show ourselves in real hiking clothes, I ask you to pay special heed to this.”Footnote 1

This statement on the significance of dress and what it should look like within the German-Jewish hiking club Blau-Weiss (Blue-White) was presented to the readership of the club's main publication, the Blau-Weiss Blätter, in 1914. Author Georg Todtmann claimed that dress was crucial in three ways. It allowed the members to improve their outward appearance “as Jews,” to distinguish themselves from non-Jewish hiking groups, and to express authenticity. Dress and interconnected notions of visibility were critical to forging and expressing feelings of belonging and identification within the German-Jewish youth movement Blau-Weiss, which operated between 1912 and 1927. With 7,000 members at the height of its existence at the end of 1918, Blau-Weiss was the first and largest Zionist youth group in Germany, with further groups founded in Austria and Czechoslovakia.Footnote 2 Stressing the importance of nature and physical activities to transform youth, it was inspired by the German nationalist Wandervogel and to a more limited degree the British Boy Scouts.Footnote 3 Yet, Blau-Weiss envisaged its transformation as a Jewish nationalist (Zionist) group that would break away from the German context in which it was operating.Footnote 4 Zionism had emerged as a Jewish political movement in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century, resulting from the experience of antisemitic exclusion and pogroms and the integration of modern ideas of nationalism.Footnote 5 Moving away from the belief that full emancipation of the Jews would be possible outside a land of their own, in the diaspora, the Zionist movement argued for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in what the German Zionists—including Blau-Weiss—called “Palestine” or less often “Eretz Israel,” the land of Israel.Footnote 6

Scholars have analyzed the emergence and development of Blau-Weiss by considering questions of Jewish belonging in Germany and its place within the broader German Zionist movement.Footnote 7 The importance of cultural practices and education to create a new German-Jewish-Zionist-identity has been highlighted.Footnote 8 Although practices such as hiking, singing, learning Hebrew, and physical exercise have received attention, dress and related practices have been largely ignored.Footnote 9 This is surprising given that guidance on how to dress and why that was important played a crucial role in the campaign to educate and transform the Jewish Blau-Weiss members. Like other Zionist youth groups, Blau-Weiss highlighted the importance of the “bodily experience” in the evolution of its members as they acquired a new German-Zionist-Jewish identity; on the individual level, this meant the bodily experience of nature—in contrast to the image of the “Jewish thinker”—and on the collective level, the experience of a new kind of Jewish community.Footnote 10 Research on Zionism and Zionist youth groups has stressed the importance of body images and practices in constructing a new counter-image of the “strong muscular Jew,” mostly male, to combat long-standing antisemitic stereotypes.Footnote 11 Sharon Gillerman has shown for Weimar Germany that this also concerned Zionist ideas of the “national Jewish body,” often mirroring German ideas of a “national community.”Footnote 12 Surprisingly, little consideration has been given to the fact that these bodies, both as ideals and in practice, were always dressed bodies. Although scholars have examined the role of dress in forging feelings of belonging for non-Jewish youth groups such as the Boy Scouts, Jewish youth groups have received less attention.Footnote 13 This article will argue that dress played an important role in forging and experimenting with a new Zionist identity; images of the Jewish body were critical, but they can only be understood by integrating the role of dress into the analysis. In this article, dress is understood, as formulated by Joanne Entwistle, as an “embodied practice” that renders the body socially meaningful by creating the link between the individual identity and social belonging.Footnote 14 As such, it is considered a crucial arena for the realization of what Gillerman has identified as attempts of “Jewish revitalisation” in Germany.Footnote 15 It will show how such an approach can deepen our understanding of processes of adaptation and shifting feelings of national and cultural belonging and identification, which are of broader relevance to historical studies of diasporas, migration, and nationalisms.

Dress ideals and practices differed within the heterogeneous Zionist movement according to geographical spaces, time, and the groups under consideration.Footnote 16 Blau-Weiss was established as the first Zionist youth movement in Germany in 1912. Focusing on this case study of Blau-Weiss allows us to consider key challenges German Jews were confronted with at the beginning of the twentieth century. After the promise of integration and the resulting acculturation and religious reform in the nineteenth century, Jewishness was increasingly restricted to religion. With the declining significance of religion and limited integration into German society, Jews searched for other forms of Jewish community and identity.Footnote 17 As one response, Jewish organizations such as Blau-Weiss emerged and called for the inner and outer transformation into the “new Jew.”Footnote 18 Linked to the bodily transformation was the requirement to know how to dress appropriately and to look after one's clothes. What this dress should look like was not clear in the beginning, and Blau-Weiss leaders and members defined and reformulated their notions of the ideal way of dressing throughout the organization's existence.

The German Zionist movement, represented by the Zionistische Vereinigung für Deutschland (ZfVD), was very small prior to 1933. While the Jewish population in Germany counted 500,000 Jews before the First World War, only 9,000 were Zionist members with numbers going up to 33,000 between the end of the war and 1933; the number of active members was even smaller.Footnote 19 In contrast, the majority of the assimilated liberal Jewish population, represented by the Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens, deemed the call for a Jewish nation counterproductive to the progress of integration into the larger Germany society. For German Zionists, the core question was to which extent their identification as nationalist Jews and their rootedness in Germany could be integrated.Footnote 20 The answers to this question changed. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the dream of a Jewish homeland, sought through diplomatic means, served as a complementary identification concept that only gained in importance as a concrete place for resettlement after the First World War. In 1922, Blau-Weiss criticized the ZfVD for not advocating strongly enough for concrete settlement in Palestine and distanced itself from the ZfVD. The changes within the broader German Zionist movement and within Blau-Weiss also influenced the significance Blau-Weiss attributed to dress.

The importance of dress within Blau-Weiss was discussed in its main publication, the Blau-Weiss Blätter, after 1923 called Neue Folge, the internally published Führerblätter, as well as single publications and guidelines published after its dissolution.Footnote 21 Since the movement's inception, its leaders, older adolescents and young adults, were expected to pass on their knowledge in their roles as “Führer,” leader, to the younger Blau-Weiss members.Footnote 22 The publications played a crucial role in communicating the agendas and values of the movement, including guidance on how to dress. Modes of dress were also communicated through visual means. Photography played an important role in documenting activities and creating visual representations of the movement.Footnote 23 Dress helped to forge a visual group identity. In publications, guidance was given on how photographs should be taken and of what, highlighting the experience of being in nature and as a group. The leaders wanted the pictures to look different from other youth groups’ pictures.Footnote 24 We cannot know how far the outfits depicted in the photographs were representative of the way Blau-Weiss members dressed on hikes. Yet, integrating such photographs allows us to reflect on the extent to which visual representations of Blau-Weiss members' dress differed from those of the non-Jewish German hiking clubs, and how far they mirrored the ideals of the written publications.Footnote 25 Blau-Weiss photographs have been retrieved from key collections of the Leo Baeck Institute (LBI) archives, namely the Rudolf and Rudolphina Menzel Collection (AR 25014), as well as the Gidal Bild Archiv at the Steinheim Institute and, for the Wandervogel, from the Archiv der deutschen Jugendbewegung (AdJb), all of which provided images for this article. In addition, the photographic collection of Blau-Weiss, A 66, from the Central Zionist Archives (CZA) has been researched. In total, approximately 500 photographs have been examined. To shed light on the role of dress and memory beyond Blau-Weiss's existence, the sources used in this article are complemented by an anniversary booklet, memoirs, and a published oral history interview with a former Blau-Weiss member.

Jewish Bodies, Dress, and Visibility between Emancipation and Zionism

Scholarship has analyzed the “Jewish body” as a social construction, an imagined body formed by both outside observers and Jews themselves.Footnote 26 Since the medieval period, non-Jews have believed that the allegedly corrupted character of Jews found its expression in specific body features, representing the Jewish man as weak and feminized and the Jewish woman as beautiful but dangerous: “As long as these stereotypes existed, Jewish men and women noted them, related and reacted to them.” Footnote 27 Equally, Jews cared about the positive connotations of their bodily features, which marked their distinctiveness from their non-Jewish cohabitants. In modern times, believing that identities could be modified, Jews also attempted to make their Jewishness visible or invisible, depending on the context.Footnote 28 As Gillerman has shown, ideas of a national Jewish community resulted in various measures to “improve” the Jewish body on the individual and the collective level.Footnote 29 Entwistle has argued more broadly for the integration of body and dress as “a crucial arena for the performance and articulation of identities.” Understanding dress as an “embodied practice,” specific attention needs to be paid to the social context with its cultural codes and notions of appropriateness.Footnote 30 Dressed Jewish bodies operated not only at the intersection of Jewish and non-Jewish contexts, but also within various inner Jewish contexts. Cultural codes and notions of appropriateness fluctuate and are not always understood by others as the wearer intends. Historically, this was particularly true for questions of Jewish identity. In premodern times “Jewish dress” meant religious dress. On the one hand, ways of dressing were influenced by Jewish laws and traditions. Regulations were designed to prevent Jews from following the sartorial customs of non-Jews. In addition, dress was required to express modesty and humility; expensive clothes should be foregone. Wearing a combination of wool and linen was forbidden (shaatnez), and Jewish men were required to wear the tzitzit, the fringes, as part of their dress, a girdle, and to grow sidelocks (peoth). Jewish women were expected to show modesty by covering their knees and arms; in addition, married women needed to cover their hair.Footnote 31 Not only did dress cover the body, but it also expressed belonging, thus attributing social meaning to the body. On the other hand, non-Jewish authorities used dress to exert control. They imposed dress codes and symbols on the Jewish population to make them visible and mark their bodies as “different” to prevent relationships between Jews and Christians. Since the early thirteenth century, Catholic rulers in Europe had imposed the wearing of a badge, following the precedent set by earlier regulations in some Muslim-ruled caliphates in the eighth century. In Europe, the badge took the shape of a ring and was usually yellow, sometimes red, or parti-colored red and white; it had to be worn throughout most of the medieval and premodern periods.Footnote 32 Another feature in medieval times was the pointed Jewish hat for men, which was in its simplest form a plain cone, often accompanied by the caftan. While Jews were deliberately wearing the Jewish hat, Christian authorities wanted them to wear the badge in addition, which the Jews saw as a mark of degradation and shame.Footnote 33 Emancipation in Europe at the end of the eighteenth century led to secularization, and some Jews converted to Christianity.Footnote 34 Jews adapted dress codes and fashion trends popular among the non-Jewish population.Footnote 35 With some Jews remaining religious, elements of modern and religious dress coexisted and were sometimes integrated.Footnote 36 In Germany, Jews adjusted to contemporary fashion trends and have played a key role in the ready-to-wear textile and fashion industry since the nineteenth century.Footnote 37 At the turn of the nineteenth century, the idea of becoming visible as “Jewish” became a key element of the Zionist project; in 1899, Heinrich York Steiner wrote in the Zionist publication Die Welt:

We did not become Zionists to have a colored rag wafting from our cloak. No, we pinned the yellow badge on the outside because our non-Jewish friends always thought it was hidden under our clothes.… We don't want to wander around as lonely fools with a yellow badge on our coat; we want to create general respect for the yellow color.Footnote 38

Although this quotation needs to be understood symbolically, because by the time it was written Jews were not required to wear the medieval yellow badge, it shows that notions of visibility, often expressed through dress, played a role in expressing identification with the Zionist project. It also shows the strong link between the Jewish body—here as a symbol for the allegedly hidden Jewishness—and dress as an “embodied practice” to become visible. Not only Zionists but also liberal Jewish groups used symbols such as badges and pins and the color yellow to express their Jewishness.Footnote 39 The colors blue and white, however, became specific symbols of the Zionist movement. Anchored in the Torah, the blue-colored dye tekhelet was of crucial significance in Jewish culture, corresponding to the color of divine revelation, whereas white symbolized physical and intellectual purity.Footnote 40 Michael Berkowitz has shown that to achieve respectability and represent strength, the first generation of Zionists at the turn of the nineteenth century chose very festive outfits for their congresses.Footnote 41 These were often complemented by subtle symbols, often in blue and white, which required inside knowledge.

Blau-Weiss between Germanness and Jewishness: Transformation and Visibility

We were children from small and middle-class households…. From the outside, everything was very tidy. Every child knew exactly what to wear and how to behave. And then suddenly someone came and tore these children out of their parents’ homes and told them exactly the opposite of what they had heard at home, whatever this so-called Jewish attitude of these parents may have been. That being a Jew meant something that you don't have to say carefully and hide from the environment, but something that you naturally and freely confess.Footnote 42

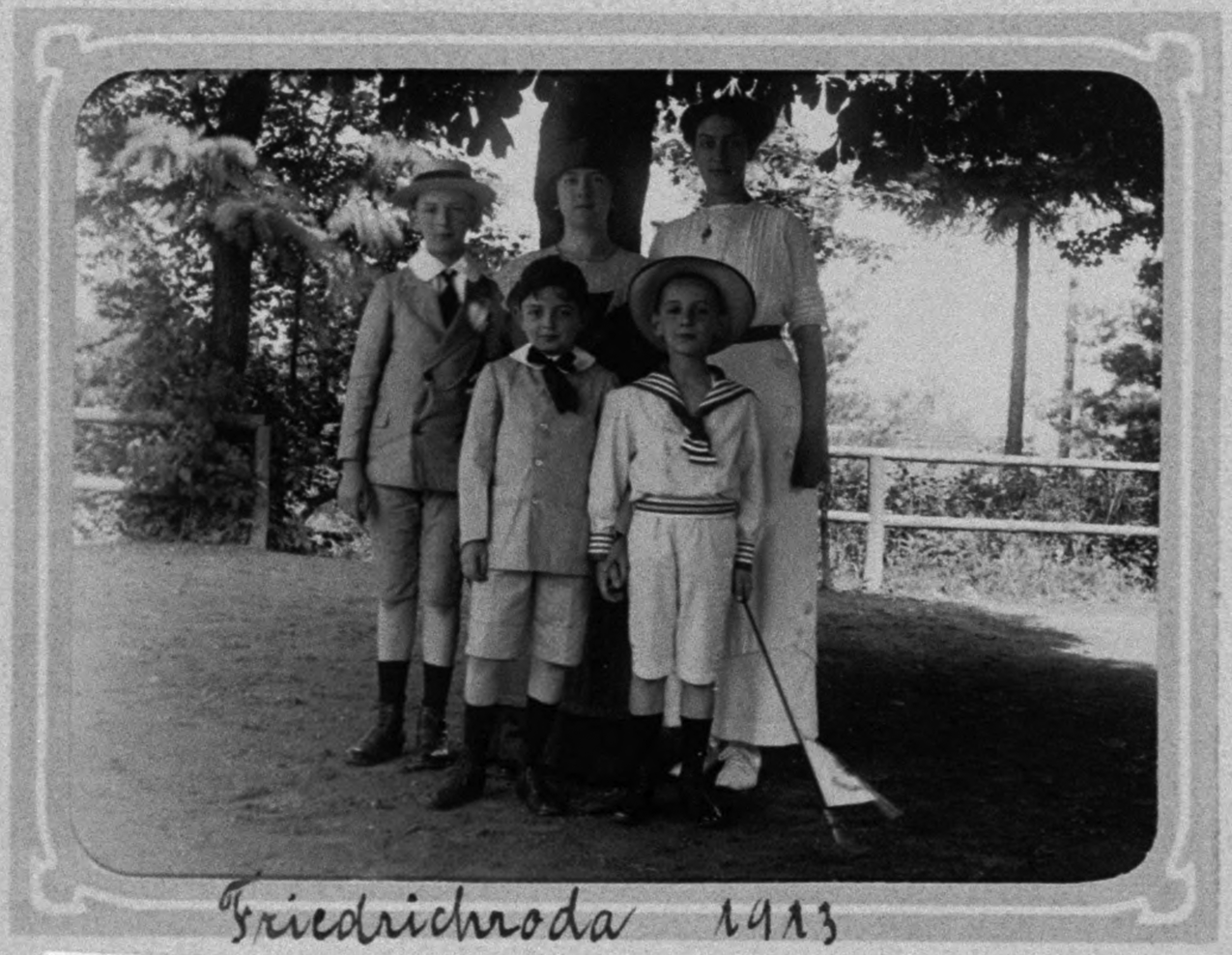

In this reminiscence, Franz Meyer, a former member of Blau-Weiss, pointed to two crucial characteristics of the youth movement, the idea of transformation and the visibility of this transformation. The process encompassed not only the differentiation from German society, but also from the members’ parents’ generation, often part of the middle class, and their sense of being a Jew in Germany. When they entered the German middle class, they also adopted its social norms with regard to dress and appearance.Footnote 43 The image (Figure 1) from the family photo album of the Jewish middle-class family Schild-Scheier on vacation in Friedrichsroda, Germany, in 1913, illustrates aspects of this assimilation. Jewish middle-class women, around the time Blau-Weiss emerged, had given up on the corset, but were wearing modest, long dresses or a combination of a blouse and a long skirt that emphasized the figure, sometimes in combination with hats (Figure 1). Middle-class men were often dressed in suits, sometimes three-piece, with trousers, vest, and jacket, with a cravat or bow tie, or simpler suits in brighter colors with button-down shirts with collar and tie. Parents dressed their children in gendered apparel. Although often shorter, girls’ dresses were similar to women's dresses. The boys’ outfits mirrored the male fashion, including a collared shirt, a cravat, a jacket, and a hat, often with short instead of long trousers. The sailor suit that had become popular in Imperial Germany for boys, and with a skirt for girls, in the first half of the twentieth century was equally adopted by Jewish middle-class families.Footnote 44 Many Jews dressed up on Sundays, when they had previously worn their weekday clothes.Footnote 45

Figure 1. Leo Baeck Institute (LBI), Schild-Scheier family collection, AR 6263, album “Traveling in Europe and via Iceland to New York, 1907–1914,” 42, F15737, Schild-Scheier family in Friedrichsroda, 1913.

Founded in 1912, Blau-Weiss opposed the liberal and utilitarian middle class in Germany, an aspiration shared by the broader youth movement in Germany and in Europe at the time. The youth revolted against their parents’ generation and propagated romantic ideals of nature and the withdrawal from a “materialistic civilization.”Footnote 46 Blau-Weiss wanted to become visible as “Jewish,” while at the same time being loyal to Germany: “Critical of their parents both for abandoning Judaism in the haste to acclimate to German culture, and for personifying materialist bourgeois lifestyles, Blau-Weiss members sought to be better Germans by being better Jews.”Footnote 47 In this early phase, Blau-Weiss deemed two elements crucial in the envisaged “inner” (mental) and “outer” (bodily) transformation. First was the experience of hiking in nature as a community, which was complemented by a wide range of physical and communal activities. Blau-Weiss was inspired by the nationalist German youth movement Wandervogel, which propagated the idea of developing a new way of living for the bourgeois youth through hiking in nature.Footnote 48 Choosing functional hiking outfits for the Wandervogel, dress also played an important role in expressing their aims.Footnote 49 The boys wore hiking boots, short loden trousers and loden jackets, often with a hat. Dating back to the sixteenth century and gaining in popularity since the nineteenth century, loden was a waterproof material, first made of sheep wool dyed in different colors, that originated from the Tyrol region of Austria. Evolving into an alpaca, camel hair, and mohair mixture in the twentieth century, loden became more widely used across Europe.Footnote 50 Although the Wandervogel officially rejected the dress codes of the urban middle class, it seems as if some male members continued to wear cravats, even on hikes (Figure 2); in photographs taken on occasions such as the “Gautag,” an official gathering, members even combined bow ties with their hiking gear, and sailor suits were integrated into the outfits (Figure 3). Members expressed romantic ideals through elements of traditional German folk costumes. Both in Germany and wider central Europe, folk costumes (Trachten) played an important role in constructing and performing national identities.Footnote 51 They allowed the wearer to express belonging to a specific national or “ethnic” group and were also widely used as a form of leisure dress.Footnote 52 For boys in the Wandervogel, this sometimes meant the integration of regional costumes such as Bavarian hats with feathers. Girls were often portrayed in long dresses, even when on hikes, their hair in braids and often with wreaths of flowers on their heads (Figure 4).Footnote 53

Figure 2. Archiv der deutschen Jugendbewegung (AdJb), Sign. F1/17/01, Julius Groß, “Aufnahmen des Alt-Wandervogels (AWV) in Berlin” (photographs of the Alt-Wandervogel in Berlin), 1911.

Figure 3. AdJb, Sign. FA/08/01, Julius Groß, “Gautag des Wandervogel e.V. in Berlin” (Gautag of the Wandervogel in Berlin), Große Heide, 1913.

Figure 4. AdJb, Sign. F1/04/03, Julius Groß, “Frühlingsfahrt des Alt-Wandervogels (AWV) zum Landheim Hanschenland in Brandenburg” (Spring trip of the Alt-Wandervogel (AWV) to the Landheim Hanschenland in Brandenburg), 1915, no. 3.

While the Wandervogel envisaged a German nationalist transformation, Blau-Weiss wanted to develop a new Jewish, Zionist counter-image to antisemitic (body) images through hiking in nature.Footnote 54 Education was important in this metamorphosis, specifically the ideals of philosopher Martin Buber, for whom questions of personal identity and spirituality lay at the core of Zionism, rather than political solutions.Footnote 55 Blau-Weiss saw the transformation as an emotional and sensual development: “The Jewish goal is the anchoring of Jewish emotional values: Jewish self-confidence, Jewish sense of responsibility and Jewish sense of belonging.”Footnote 56 In this early stage, a strong bond with German culture and nature, perceived as “Heimat,” was not seen as contradicting a desired Jewish homeland in Palestine.Footnote 57 As Jan Rybak has shown for east central Europe, Zionists were primarily engaged in a “nation building project in their own spaces,” which was not merely seen as a preparatory step for the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.Footnote 58 In their desire to create a German-Jewish identity, the Blau-Weiss leaders intended to come to Palestine only for occasional visits. In their view, eastern European Jews should be the ones settling the land.Footnote 59

Blau-Weiss wanted the transformation and the new “Jewishness” to be noticeable. “The Blau-Weiss member shall be proud and happy when he thinks of being a Jew. He shall know why he is hiking in a Jewish hiking club and should confess himself of being a Jew on hikes and return greetings of “Heil” by the Wandervogel by “Shalom,”Footnote 60 stated the Blau-Weiss leadership in 1917. It was not only greetings and Jewish songs that would signify “Jewishness,” but the exposure of the dressed body. The body was seen as the visible form of the desired transformation of the Jewish members. On the one hand, it was meant to express the new relationship of the Jew with nature, far away from the urban middle class; on the other hand, the transformed body should manifest discipline and the ability to look after oneself.Footnote 61 The First World War was a turning point for Blau-Weiss and the broader German Zionist movement. The favorable political circumstances in the British Mandate and the Balfour declaration led to a new call for migration to Palestine. From 1918 onward, Blau-Weiss called for the practical realization of Zionism, leading to conflicts with the ZVfD, whose members doubted the feasibility of the intended settlement. During that time, Blau Weiss developed into a more “tightly knit Bund” and emphasized the need for discipline and militancy. Not individual transformation, but strengthening the identification with the group and community, was now the priority. Settlement in Palestine became the major task now.Footnote 62 In Prunn, in 1922, Blau-Weiss officially separated from the German Zionists over the question of emigration; its leader Walter Moses claimed that the movement would now become an independent and militant “Bund of action.”Footnote 63 These changes marked a generational shift within Blau-Weiss. Although the earlier generation had wanted to move away from the political Zionism of Theodor Herzl, which had aimed to realize a Jewish homeland through diplomatic means, through a more practical approach, the new generation went further by wanting to transform Zionism into an “emigration movement.”Footnote 64 Blau-Weiss now became more exclusive, forbidding membership of any other Zionist groups and adhering to authoritarian rules.Footnote 65 During this time, a separate Blau-Weiss hiking club for girls was also established.Footnote 66 Blau-Weiss members started settling in Palestine in 1923; from 1924 onward a willingness to migrate became a requirement. The settlement led to new conflicts in the British Mandate for Palestine. The Zionist organizations led by socialist eastern European settlers did not fit with the agenda of the Blau-Weiss members, who envisaged a leadership role while preserving their German heritage. Their unwillingness to learn Hebrew, their dislike of the socialist Zionists and resultant conflicts led to the failure of the settlement project, with many Blau-Weiss members returning to Germany in 1925. Blau-Weiss was dissolved in February 1927, with many members having already joined the new Jewish Youth movement “Kadima” in 1926.Footnote 67

How to Dress as a Blau-Weiss Member: Forging a New Visual Identity

It may be that we looked very weird at first. I sent in a picture myself for the exhibition of one of the first hiking groups, where dear friends appeared in straw hats and others with mandarin collars and ties. Soon, however, the shimmer collar became modern and gradually we got a more uniform look.Footnote 68

With these words, in 1962, Franz Meyer looked back at dress in the early days of the Blau-Weiss movement. First, we learn that in the beginning, there was no consensus among the group members as to what the “appropriate” way of dressing was. The members had chosen different outfits for the hike and the photograph taken. As Entwistle has shown, notions of appropriateness are related to a specific social context. The uncertainty regarding the outfits can also be understood as an uncertainty about the social context. Was the relevant social context the German middle class with its prevailing dress codes, other German hiking clubs such as the Wandervogel, or an imagined new Jewish context that was yet to be created?

In 1913, one year after the foundation of the movement, Karl Glaser described in the Blau-Weiss Blätter the appropriate dress for hiking as a Blau-Weiss member.Footnote 69 His article shows that this matter was considered important, but at the same time needed to be defined. Glaser highlighted two requirements: first, the dress should be functional when going on hikes and, second, one should come across as well dressed. This was particularly important for Jews: “We are used to dressing in a respectable and functional manner everywhere—so why not so on the hiking trip?… We need to look respectable—and we need to fit into the landscape. Everyone will approach you in a much friendlier way, and you will have double the pleasure.”Footnote 70

He made clear that Jews should dress according to the dress codes of the Germans—or ideally better than them. Only this would be seen as “appropriate.” He then gave advice on what would be considered functional and appropriate—and thus the best—clothing. This way of dressing was also linked to “authenticity,” as if this was proof of the successful (bodily) transformation of the wearer who had distanced himself from the image of the “Jewish thinker.” The “real hiker” wears “a soft wool shirt with a soft turn-down collar, cotton lower leg dresses, rough woolen stockings and lace-up shoes with double soles and a straw insert. There are also short loden trousers with stockings or long trousers with wrap canvas or leather gaiters, a loden jacket, a wide-brimmed loden hat and a loden cape.”Footnote 71 This shows that it was through such publications that already commonly known dress items were labeled as “authentic,” “functional,” and “appropriate” for the Blau-Weiss members. Glaser paid tribute to the German Wandervogel for having introduced a specific hiking outfit and encouraged the Blau-Weiss members to go to designated shops that had recently opened.Footnote 72 He thus made clear that Blau-Weiss, in 1913, tried to copy the outfits of the German hiking club. With this, he opted for the adaptation of the nationally connoted German hiking costume, expressing loyalty to German culture. During this phase, photographs taken on hikes and gatherings indicate that the ideals communicated may have differed from the styles adopted when photographed, during this early phase. Members probably combined clothes they had at home with items of the hiking outfit described by Glaser and, as indicated by Franz Meyer, they also experimented with outfits. The Blau-Weiss boys (Figure 5), for example, are wearing short loden trousers and stockings, combined with regular white buttoned shirts, with open collars. Hats were recommended, but not worn by all Blau-Weiss members. Although their clothes slightly differed from the described ideal, the boys are dressed in a similar way, creating a uniform appearance that made them recognizable as a group. Inspiration was also drawn from the Wandervogel in the introduction of a pin, the Blau-Weiss Nadel, in 1913.Footnote 73 It was awarded to Blau-Weiss members who had taken part in ten hikes. It was a small symbol made up of two diagonally separated colored areas in blue and white (Figure 6). As a pin, it was attached to the jacket and as a symbol inserted on the cover pages of the first issues of the Blau-Weiss Blätter.Footnote 74 On the one hand, the pin was meant to serve as an identification mark to allow others to recognize the Blau-Weiss members. Yet, because it was small, one had to be very close to the wearer to be able to recognize it. Furthermore, some knowledge of the Blau-Weiss movement was needed to understand its meaning. On the other hand, the pin was directed toward the movement's members, to strengthen their “Korpsgeist,” the esprit de corps, as the movement's guidelines formulated in 1913.Footnote 75 It was seen as a symbol to represent the—inner and outer—transformation of the Blau-Weiss members. From 1914, the Blau-Weiss leaders increasingly emphasized that the recipients of the pin were expected to exhibit “appropriate behavior and appearance”: it is “an award that is only given to those who we trust will always behave in a blue and white manner.”Footnote 76

Figure 5. LBI, Rudolf and Rudolphina Menzel Collection, AR 25014/F 32753, Blau-Weiss youth group marching.

Figure 6. LBI, Blau-Weiss Collection, 1924–1925, AR 2892, pin with the Blau-Weiss symbol, probably of Blau-Weiss leader Eli Schachtel.

Blau-Weiss explicitly explained to the female Blau-Weiss members how to dress. A separate Blau-Weiss Mädchenbund (girls’ group) was only established in 1922. Before that, even though hiking groups for girls existed, boys and girls would meet during their breaks or hike together if not enough leaders were available.Footnote 77 Entwistle emphasized that notions of appropriateness not only depended on the social context, but also largely differed according to gender. This concerns both the question of what is seen as appropriate apparel and the fact that gender is actively reproduced through dress.Footnote 78 In 1913, Edith Henschel, a female leader in the movement, addressed the girls, emphasizing the need to dress appropriately for outdoor activities. In so doing, she communicated the ideals that had also been formulated internally in the “guidelines for the foundation” of Blau-Weiss.Footnote 79 We cannot know to what extent the instructions resulted from previous experiences. They reveal the importance of aesthetic, “fashionable” dress for women, while at the same time establishing new notions of appropriateness within Blau-Weiss.Footnote 80 In 1913, Henschel formulated expectations by giving examples of inappropriate items such as jewelry, handbags, and fur collars; she stated that only a “functional dress” would be considered beautiful in this context: sturdy shoes, a skirt made of loden that could be opened on the side, and a loden coat, which was seen as the most important element, combined with a simple blouse or sweater. If needed, short and slim sport shorts could be worn.Footnote 81 Henschel called for a swift change in dress: “We as female leaders would appreciate if you would come to our hikes dressed like this very soon.”Footnote 82 In addition to recommendations for shops where one could buy these items, the girls were advised to put these on the wish list as a birthday present or for Hanukkah, when, as in the Christian tradition of Christmas, presents are given to children.Footnote 83 Most urgent, according to Henschel, was the acquirement of a loden hat, which would make the members recognizable as a group: “Now we talk about hats, that due to their colors and different shapes are the items that most clearly lead a uniform appearance, even of the smallest group of female hikers.”Footnote 84 The hat that she recommended would be sold at the next group's gathering and the girls were urged to buy one.Footnote 85 In the photograph (Figure 7), likely taken before 1915, the girls are wearing elements of the loden dress, solid hiking boots, long skirts made of loden, and a loden jacket.

Figure 7. LBI, Rudolf and Rudolphina Menzel Collection, AR 25014, F 32765, Blau-Weiss youth group.

Some of the girls complemented these with hats. Elegant accessories are limited to flowers on the hat; one girl is wearing a bow in her hair. Four of the girls are holding hiking sticks in their hands. One of the girls is wearing an open collared white shirt with a neckerchief, popular in other hiking groups such as the Boy Scouts; two other girls are wearing woolen sweaters with collared shirts underneath or closed jackets. The picture indicates that girls were adapting the functional dress that was considered appropriate for hiking. Yet, the accessories show that some leeway was taken to integrate elegant elements into the outfit. Despite some differences, the girls adopted a similar way of dressing and are recognizable as a group. For the girls, who were expected to dress in a feminine and elegant way, the change from bourgeois dress to the required functional hiking outfit may have been more drastic than for boys whose everyday outfits were already more functional. It is therefore likely that the girls’ regular outfits could not easily be integrated into the new hiking outfits and that some more flexibility was given with regard to the level of uniformity. Blau-Weiss, in contrast to the Wandervogel, wanted to establish a functional loden outfit for girls. Yet, photographs exhibit Blau-Weiss girls in elegant long dresses with embroideries, their hair in braids, often decorated with wreaths of flowers that were very similar to the traditional German way the girls in the Wandervogel dressed (Figure 8).Footnote 86 As a Blau-Weiss girl reported in the movement's publication in 1916: “We spent our time weaving wreaths, which we decorated with red chains of red rowan berries and, when the boys finally arrived, we girls we sprang toward them adorned with wreaths of heather.”Footnote 87

Figure 8. Salomon Ludwig Steinheim Institut für deutsch-jüdische Geschichte, Gidal-Bildarchiv, Sign. 2641 “Breslauer Gruppe des Jugendbundes Blau-Weiss” (Breslau group of the youth association Blau-Weiss. Without year (likely 1918, see CZA).

In both articles from 1913, when the movement had already been hiking or a while, the leaders tried to articulate new and clear definitions of the appropriate way of dressing. During this early period, the leaders justified the need to establish a distinct outfit in three ways: first, to differentiate the Blau-Weiss members from their parents. Adopting the outfits of the nationalist German Wandervogel signified a break with the Jewish middle-class values at home. Second, to make sure that the Blau-Weiss members were well and appropriately dressed—specifically as Jews. There was a strong desire to fit into German society by dressing accordingly in order to avoid any negative attention and thus to counter antisemitic stereotypes. And third, to create a sense of group belonging through dress and items such as the pin, both directed inward toward the members and outward. The guidance led the members to dress in a similar way, resulting in a more uniform group appearance that represented strength. The new way of dressing, even if not made explicit in this early phase, also seemed to fulfill a disciplinary and unifying character.

Choosing a specific way of dressing to become visible as “Jewish” and “Zionist” gained in importance in the following years for Blau-Weiss. The so called Blau-Weiss-Führer published guidelines in 1917 to train the leaders of the movement for their work with the young Blau-Weiss members. Expectations regarding appropriate dress for both boys and girls were formulated.Footnote 88 Although these were similar to the ideals devised in 1913, the “appropriate dress” was now a requirement for taking part in the activities of the movement. Among the reasons given was that Blau-Weiss should be able to compete with and be taken seriously by other non-Jewish hiking clubs.Footnote 89 The importance of the pin to express loyalty with the movement and testify to “impeccable behavior” was further strengthened.Footnote 90

The Wandervogel served as an orientation, but Blau-Weiss now made explicit how it wanted to differ from it. Both in 1913 and 1917, the Blau-Weiss claimed that it would only take the pin as an inspiration from the Wandervogel to strengthen feelings of group belonging, while it would reject their uniformity.Footnote 91 Blau-Weiss justified the latter position by stating that any military notions should be avoided out of pedagogical considerations and “especially for Jews.”Footnote 92 It was specifically in the German army during the First World War that Jews were experiencing exclusion and antisemitic attacks, with German nationalism on the rise.Footnote 93

Forging these new ideals and dissociating from the German nationalist hiking groups was a complex process; items and modes of dress had no meaning in themselves, it needed to be attributed and perpetuated. What was to be rejected as “German nationalist dress,” and which elements could be adapted and charged with new Jewish, Zionist meaning? Uniformity was a particularly charged issue. Blau-Weiss officially rejected uniformity, but wanted dress to serve a unifying function directed both inward and outward. Dating back to the early years of the movement, it became even more apparent after the First World War.

What Blau-Weiss perceived as the ideal dress changed after the First World War to the extent that the movement developed into a more disciplined authoritarian “Bund.” The urge to advocate for migration to Palestine was accompanied by the desire to distinguish the group more explicitly from the German youth movements such as the Wandervogel. Militaristic elements that had been officially rejected were now introduced under the banner of a Jewish nationalist goal. Blau-Weiss saw settlement in Palestine as a break with the bourgeois lifestyle and emphasized the rupture both with previous religious traditions and the eastern European Jews who many German Jews saw as “backward.”Footnote 94

Following the First World War, Blau-Weiss established the outfit that its members would later refer to as the Kluft, German for what could be translated as “uniform.” In 1925, a publication by the national leadership for the 10- to 15-year-old members, who were called Hamischmar, outlined the characteristics of the new official outfit that was expected to be worn by every male member.Footnote 95 Now the term Tracht was used. Originally referring to attire worn on a regular basis, the additional connotation of Tracht as folk costume, expressing regional or national belonging to a group, seems crucial in this context.Footnote 96 By using this term, the leaders conveyed that they now saw themselves as a specific community, differing clearly from German society and other hiking groups. Now the items were not supposed to be made of loden anymore, but of gray corduroy, called Manchester due to its English origin, a durable fabric woven with three sets of yarns and vertical ribs.Footnote 97 With corduroy gaining in popularity in central Europe around this time, Blau-Weiss may have adhered to these new dress modes. Yet, it is noticeable that, even in the winter, the wearing of loden was now explicitly forbidden, which may point to a conscious demarcation from the nationally connotated German fabric.Footnote 98 Every single item of the outfit—from the gray jacket to the navy shirt and black or gray socks—was described and outlined in detail, even the required number of pockets; the authors gave guidance for both the summer and the winter season.Footnote 99 In choosing terms such as Kluftjacke (meaning the jacket that was part of the Blau-Weiss uniform), specific terms were introduced for the items now mandatory for every member.Footnote 100 In addition to the required items, it was specified that a corduroy belt should complement the outfit, and the kind of equipment the young Blau-Weiss members should have in their pockets was detailed.Footnote 101 The publication gave the following reasons for the requirement to wear the outfit, now seen as the symbol of the movement: “The uniformity (of the outfit) is the external expression of the movement. The outfit is also the external characteristic through which Blau-Weiss differentiates itself from the society in which middle it lives.”Footnote 102 Uniformity in dress was now the explicit goal. A new nationalist, Zionist, meaning was attributed to dress now that the establishment of a separate Jewish nationalist context and geographical space seemed within reach. In a speech, printed in an advertising booklet for Blau-Weiss in 1925, Ferdinand Ostertag added another purpose of the Kluft: “We want to differentiate ourselves from the others, not only out of functional reasons…, but also out of the pleasure to offend the others.”Footnote 103 Although this was likely a rhetorical provocation, it testifies to Blau-Weiss's determination to distance itself not only from the German surroundings but probably also from Jews outside of Blau-Weiss.

The desired uniformity in dress can only be identified to a certain degree in photographs taken of Blau-Weiss members in the 1920s. A photograph from Munich shows a group of male Blau-Weiss members in 1923 (Figure 9). The man sitting on the carriage is wearing a combination of clothes that match the requirements of the Kluft; a hat, likely made of fabric, and what looks like a loden jacket are combined with short trousers, stockings, and robust hiking boots. In the picture of six Blau-Weiss members from Frankfurt, sitting around a bonfire in 1924, only one member is dressed according to the ideals outlined previously (Figure 10). The boy on the right is wearing short trousers, with stockings and hiking boots. He is wearing a jacket and a hat, both not made of loden but a lighter fabric that cannot clearly be identified as corduroy. As Ulrike Pilarczyk has highlighted, many members of youth groups took pride in wearing short trousers, even in colder weather.Footnote 104 This further supports the close interconnection between body and dress. It also shows that the members likely adapted the meaning and the symbolic function of the idealized outfit that went beyond the function “to keep oneself warm.” However, other members were choosing clothes that did not match the ideal Kluft. Woolen sweaters and simple jackets, in addition to long or sometimes short trousers and stockings with hiking shoes, can be identified in other pictures. The girls are also depicted in functional hiking dress, sometimes in trousers, sometimes with skirts. Although the outfits did not always fulfill all criteria of the Kluft, items seen as “bourgeois dress items” such as cravats, bow ties, and starched collars were usually not worn and elegant items and accessories seemed to have declined in popularity.Footnote 105

Figure 9. Gidal-Bildarchiv, Sign. 2400, “Eine Münchner Blau Weiss-Gruppe auf großer Fahrt nach Franken, 1923” (Blau-Weiss group from Munich on a trip to Franconia, 1923).

Figure 10. Gidal-Bildarchiv, Sign. 1061, “Frankfurter Gruppe des Jugendbundes Blau Weiss am Lagerfeuer, 1924” (Frankfurt group of the youth association Blau Weiss around the campfire, 1924).

While in 1914 the orientation toward the German Wandervogel and dressing appropriately within German society had been emphasized, along with wanting to be different from the parents’ generation, the outfit now aimed at expressing membership of the Zionist movement and differentiation from German society. This reflected the renewed goal to settle in Palestine and thus to separate from German society. The more uniform look and the new meaning that was attributed to the outfit can be understood as an expression of a newly imagined and created social context—now seen as a specific Jewish context—with its own notions of appropriateness.

It is likely that the imagination of this new context and the Zionist uniform was more important than the actual differences in dress in comparison with non-Jewish hiking groups. Ultimately, the uniform consisted of items that had been introduced and used by German hiking groups. Although the choice of dress was supposed to make the group recognizable as Jewish, it was still situated in the context of a “German fashion system,” including the availability of clothing, but also notions of what was perceived as appropriate. This became clear once Blau-Weiss members started settling in Palestine, where they were aiming to live as a distinct German-Jewish group; many of them refused to learn Hebrew or adapt to the very different living conditions among the mostly eastern European settlers and the local Arab population.

Dress as an Embodied Practice: Anchoring and Perpetuating the New Ideals

In his memoirs, published in 1971, former Blau-Weiss member Joseph Dunner writes: “Here (in the Blau-Weiss movement) I learned that only the petty bourgeois are wearing hats and that an open collar is more sensible than a starched shirt with a tie.”Footnote 106 Among several things he recalls having learned, the establishment of new dress ideals is the first point that he raises. It is difficult to tell if this points to a specific connection between personal memories and the dress that was worn at the time or the importance the movement attributed to this theme. Blau-Weiss leaders took a variety of measures to establish the changing sartorial ideals throughout the movement's existence. The Blau-Weiss publications played a key role in perpetuating and enforcing the ideals and related expectations; former Blau-Weiss members Dan Frankel and Dolf Michaelis both emphasized the importance of the Blätter, especially for older members.Footnote 107 In these publications, the tone changed according to the importance that was attributed to dress. In Glaser's and Henschel's articles from 1913, the first guidelines on dress were formulated as recommendations, although the tone, in a humorous way, made clear that social consequences in the groups may follow if the members did not dress accordingly. Glaser and Henschel encouraged the children to ask their parents to buy the right clothes for them and labeled only functional outfits as appropriate and beautiful. The authors tried to provoke the fear of looking “ridiculous” and different within the group. In addition, the authors emphasized the risk of peer pressure.Footnote 108 Glaser wrote: “You now have heard what such great leaders think about hiking outfits. From now on no one will dare to approach us with his red student cap, otherwise it may happen that it will be buried somewhere in the forest.… He will then be able to buy a hat at our next gathering.”Footnote 109

The student cap, Schülermütze, was worn by pupils in Germany with colors according to school and grade.Footnote 110 By emphasizing that this would be “inappropriate” headwear within the Blau-Weiss movement, he made clear that the hiking club should be seen as a distinct social context, different from the German school, with specific dress codes. In publications, readers were also made aware of the existence of an equipment list, Ausrüstungszettel, that would be handed out to help members to know what the appropriate dress was and to prepare for the hikes accordingly.Footnote 111

The tone changed in 1917. Where previously options were given to choose from the wardrobe one had at home, it was now mandatory to own and wear specific items. However, the loden hat that had been a requirement in 1913 seemed to be optional in 1917. The guidance made clear that it was now explicitly forbidden to bring items on hikes that had previously been considered “unpractical,” such as umbrellas, school caps, straw hats, jewelry, or handbags. It was made clear that “hikers who were not appropriately dressed would be rejected.”Footnote 112 These instructions also implied that the Blau-Weiss movement was now seen as a “distinct social context” with its own notions of appropriate dress. In 1925, the guidance published in Hamischmar read like a commandment, emphasizing the importance of body care, and especially the boys’ appearance: “Every boy shall learn how to look after himself. He takes care of his body and health. He looks after his clothing and hates uncleanliness.”Footnote 113

In addition to the publications, leaders and external experts gave talks on the themes of body care and dressing. In 1914, leaders were educated on themes such as “foot care,” “dental care,” “body care and clothing” and were expected to pass this knowledge on to the Blau-Weiss members.Footnote 114 Although the writer admitted that these themes could be seen as trivial by some readers, he implied that the importance of these themes for the core values of Blau-Weiss should be clear to every leader.Footnote 115 We see here, as highlighted by Gillerman, the importance of both body and dress as an arena for the improvement of the individual and the collective Jewish body—and the expectation that the members would be aware of this.

Like the Boy Scout movement, Blau-Weiss introduced a system of entrance rituals, tests, and criteria for advancement, acknowledging specific skills and loyalty to the movement. Especially after 1918 with the strengthening of rigid structures, a strict system of criteria and tests to join and move up in the hierarchy was introduced. The examination system had different levels that the young Blau-Weiss members could achieve gradually. Knowledge of the appropriate outfit for different seasons and weather conditions as well as skills to alter and fix clothing were tested. It was specifically the first exam that required comprehensive knowledge of the Blau-Weiss outfit, how to wear it, and how to take care of it: “The examined hiker must exhibit a well-founded knowledge of costume and equipment.”Footnote 116 According to the booklet, this included not only a justification of why certain items were part of the Tracht, but also profound knowledge on the proper care for and maintenance of the clothes.Footnote 117 Expectations around fixing clothes were gendered. Although boys were expected to acquire these skills themselves, to do so, they were encouraged to ask their mother or “any girl” to show them how to do it.Footnote 118 Yet, it seems as if “appropriate outward appearance” and looking after oneself were seen as crucial now, leading to the expectation that boys would acquire the necessary skills. Blau-Weiss also incorporated similar skills such as “knitting, sewing, crocheting, knitting, darning” into the activities and educational program for female Blau-Weiss members.Footnote 119

The question remains as to what extent the dress ideals and the leaders’ attempts to enforce them resulted in a specific and uniform way of dressing within the Blau-Weiss movement. The Blau-Weiss Blätter presented different views about this. In 1913, it was reported that the audience at a Jewish youth groups’ gymnastics competition had noticed the Blau-Weiss members because of their outward appearance. It was their hiking outfits, hiking sticks, their bags with bottles and cooking pots, as well as their marching as a uniform group, culminating in the presentation of their new blue and white flag.Footnote 120 Yet, a year later the Blau-Weiss Blätter reported that non-Jewish passersby often mistook Blau-Weiss groups for members of the Wandervogel.Footnote 121 A similar observation was made in Austria, where the Blau-Weiss members were sometimes mistaken for Pfadfinder (Boy Scouts).Footnote 122 We must take into consideration that the outfits during this time were strongly oriented toward the Wandervogel and that dress regulations were not strictly enforced. Furthermore, the Wandervogel had existed for a longer period, and it is thus unsurprising that passersby would recognize the groups that they knew without paying attention to details such as the different colors of the pins or the songs they sang. Even during the later period, when the Kluft was introduced, the outfits still partially resembled the outfits of the Wandervogel as similar items of clothing were incorporated. To be able to recognize the Blau-Weiss groups, those who saw them had to understand the meaning of their dress. It seems as if Jews were more likely to recognize the symbols and ways of dressing, maybe drawing on publications and knowledge of the movement's context, whereas non-Jews associated the appearance more often with other non-Jewish hiking groups they were familiar with. It is, however, likely that it was not the actual clothes worn and the perception by others that was most crucial but the significance the clothes had for Blau-Weiss. In forging new sartorial ideals and perpetuating them through publications and photographs, the members attributed meaning to the clothes and associated feelings of belonging and identification with them. This also became apparent in complaints by Blau-Weiss leaders. As the Blau-Weiss Tracht was increasingly seen as an expression of the core values of the movement after 1918, the extent to which the Blau-Weiss members conformed to the dress ideals was thus seen as an expression of the moral state of the movement. In 1924, in a talk about the preparation of youth for the migration to Palestine, leader Werner Bloch mourned the disappearance of the Kluft, the Blau-Weiss outfit, as a reflection of the morally weak state of the movement: “The hiking club must be re-created. Forms are rotten, the bourgeois clothing that displaces the Kluft (the official outfit), and the prevalence of smoking are examples of this.”Footnote 123

The re-creation that Werner Bloch had hoped for did not occur; Blau-Weiss was officially dissolved in 1927. Yet, dress continued to matter even after the movement's dissolution. Blau-Weiss influenced the emergence of new dress ideals in the successor organizations such as Kadima and Kameraden and, as we have seen in the quotation by Joseph Dunner, in the memory of its former members. The anniversary booklet from 1962 did not only contain individual contributions by former members that mentioned the importance of dress, but also devoted a large section to the evolution of the Blau-Weiss outfit, as shown in an exhibition organized for the occasion.Footnote 124 Former members also highlighted the importance and uniqueness of the Blau-Weiss outfit by contrasting it with the allegedly different Wandervogel outfits. Dolf Michaelis emphasized the “ridiculous” tendency of the girls to dress in traditional German costumes in the Wandervogel, implying that Blau-Weiss differed in this regard.Footnote 125 Given that Blau-Weiss girls sometimes wore similar outfits, it is likely that Michaelis constructed this difference in retrospect to emphasize the uniqueness of Blau-Weiss. It was thus probably not a coincidence that Joseph Dunner had highlighted the specific sartorial ideals in his memoir, pointing to a close interconnection of dress, feelings of belonging, and memory.

Conclusion

Taking the case study of the German-Jewish youth movement Blau-Weiss, this article has shown how a focus on dress as an “embodied practice” allows us to gain a deeper understanding of hybrid feelings of belonging between Jewishness and Germanness and the forging of a Zionist vision in Germany at the beginning of the twentieth century. From the beginning of the movement's existence, dress was intended to express belonging to the Jewish hiking group and the aims it represented. Dress was seen to play a role in making the desired internal and external evolution into a new national Jewish identity visible. To the extent that concepts of this new national identity between Jewishness and Germanness changed, ideals and practices with regard to dress were altered. In the beginning, when the Blau-Weiss members favored the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine while intending to stay in Germany, they copied the way of dressing adopted by the German nationalist hiking group Wandervogel. Functional clothes designated for hiking in loden material, for both boys and girls, allowed them to differentiate themselves from their Jewish parents’ generation, who had adapted to the fashions of the German middle classes. While wanting to be recognized as Jewish, German notions of appropriateness exerted a strong influence. The aspiration to come across as “well dressed,” specifically “as Jews,” was intended to counter antisemitic prejudices. In comparison with the Wandervogel, Blau-Weiss seemed to be stricter in rejecting “bourgeois” dress items such as cravats and bow ties and, at least in theory, avoided the integration of elements from traditional German costumes and argued against the introduction of militaristic uniforms. Toward the end of the First World War, the concrete vision of migration to Palestine led to the reformulation of these ideals, with a more uniform outfit now introduced as an expression of the imagined distinct nationalist Jewish context. Although the items belonging to the outfit had not changed significantly, it was now presented, in publications and guidelines as the Tracht or Kluft, as the costume representing the movement. Publications, talks, tests, entrance procedures, and photographs were designed to communicate and shore up these ideals.

Articulated ideals and actual dress practices differed. Despite the official rejection of them, unifying elements played a role from the outset, and alongside the loden outfits, girls were also wearing the dresses with embroideries and flowers in their hair that were officially condemned as the nationalist German way of dressing that the Wandervogel was known for. Although Blau-Weiss made their Jewishness and group membership visible to others, differences in dress between the Wandervogel and Blau-Weiss were subtle. Items that indicated belonging to the group, such as the Blau Weiss pin, were small. For passersby recognizing the group was probably only possible with some knowledge of their dress and symbols and in combination with other activities, such as the singing of Jewish songs. However, the creation of new sartorial ideals likely fulfilled a more important function for the group. By charging an outfit with political meaning and dressing up in similar ways, the Blau-Weiss members could express feelings of identification and group belonging. In this sense, for the Blau-Weiss members to feel different and “Zionist” when wearing the Kluft was probably more important than to look different to the outside viewer. This close interconnection was also expressed in the importance of dress in the memory of Blau-Weiss members and conflicts about the moral state of the movement. Overall, dress was not an abstract category but an embodied practice that was interconnected with feelings, as well as ideals—feelings of belonging and feelings of being appropriately, or inappropriately, dressed as a Jew within changing social contexts in modern Germany. What has been shown here for the case study of the German-Jewish youth movement Blau-Weiss suggests possibilities for historical studies on diasporas, mobility, and migration, in which an investigation of dress can reveal intimate and changing feelings of national, social, and cultural belonging and identification across generations and (imagined) social and geographical spaces.

Acknowledgments

The research for this article was generously funded by the European Commission through a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship, IDCLOTHING 795309, held at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem from 2019 to 2021. Costs for image permissions were supported by the School for History, Politics and International Relations (HyPIR) at the University of Leicester with a Research Development Fund in 2021. For their feedback on earlier drafts of this article, I thank Anat Helman and Zoe Groves. I am very grateful to Susanna Kunze, Ulrike Pilarczyk, and Knut Bergbauer for their generous advice, Rebekka Grossman for helping me to get additional sources, Marc Volovici and Carly Silver for reading recommendations, and Beate Kuhnle for giving me access to the books I needed. I thank the archivists and their respective institutions for providing me with the images incorporated in this article. I am very grateful to the anoymous peer reviewers and their valuable feedback that helped to improve this article.