The Insurrectionists

America’s founders were insurrectionists, rebels against the greatest imperial overlord of their age. The Americans, like most rebels, were weak and initially bereft of diplomatic, military, or economic power. But in the informational realm, the Americans had something of immense value – a powerful, infectious idea.

The Origins of the War for American Independence, 1776–83

The most important Colonial idea was that the Americans should have a say in ruling themselves. Britain had long practiced “salutary neglect” toward the colonies, but 1763’s conclusion of the French and Indian War (or Seven Years’ War) left a victorious but indebted Britain eager to right its fiscal ship via a once traditional means: taxation. London expected its subjects to do their duty, including those in America, a demand made after Britain took France’s Canadian lands, removing the primary threat to American security. The drive for a common response knit together thirteen colonies.

Britain’s Parliament passed the Sugar Act in April 1764, reducing the molasses tax by half, but this half London intended to collect. The Americans’ reply was novel: Parliament had no right to tax them because the colonists hadn’t elected any of its members. March 1765’s Stamp Act imposed a levy on anything the Colonials printed. Opposition groups known as the Sons of Liberty formed; a protest petition followed. Parliament dropped the Stamp Act but insisted upon its authority over the colonies. The 1767 Townshend Acts followed, taxing imports such as tea, paint, and glass, and feeding the Colonial political awakening. Riots and protests produced tragedies like the 1770 Boston “Massacre,” while Pennsylvanian John Dickinson argued the colonists could only be taxed by assemblies they elected. Parliament eventually repealed the taxes – except that on tea.2

On December 16, 1773, Americans dressed as Indians famously staged the Boston Tea Party by dumping tea into the harbor. Parliament acted against growing Colonial lawlessness by closing Boston harbor pending restitution, occupying the city, and suspending Massachusetts’ government. The colonists replied with Philadelphia’s September 1774 Continental Congress. It branded British actions the “Intolerable Acts,” dispatched a petition listing thirteen grievances, and used trade as a weapon for the first time by halting British imports and restricting American exports. Colonial committees formed to enforce Congress’ rulings began seizing local reins of power, including over the militia. The British attempted conciliation. The colonists prepared for war by stealing British gunpowder and stockpiling military supplies.3

Under the direction of Lord Frederick North, first minister to the king and head of government, Parliament declared Massachusetts in rebellion on February 9, 1775, ordered its leaders arrested and Colonial arsenals seized, and authorized Lieutenant General Thomas Gage, Massachusetts’ military governor, to use force to reassert control. On April 18, 1775, Gage dispatched 800 soldiers from Boston to seize powder and weapons stored at a village named Concord. American militia assembled on the green at Lexington blocked their advance. A firefight ensued from which the Americans fled. Another skirmish at Concord followed. On their return march to Boston, the British endured numerous, uncoordinated attacks from Colonial militia (who proved exceptionally poor marksmen) and retaliated by looting the homes of suspected attackers and killing the occupants. The Americans put their version of events on a fast ship and had it to the London newspapers two weeks before the British government received Gage’s report.4

The violence enflamed the Americans, who overthrew the Royal governors in the lower thirteen colonies. Even in areas where they were a minority, the insurrectionists seized control.5

An Insurrection Like No Other

America first learned to use its power – slight though it was – in war’s crucible. That the War for American Independence began as an insurrection shaped its nature. It also became a revolutionary struggle as the Americans sought to rule themselves in a manner and on a scale not attempted since ancient Rome. But doing this required the revolt succeed. Insurrections generally hinge upon three factors: the support of the people; the control of internal or external insurgent sanctuary; and whether the rebels have outside aid.

The Political Aims

At the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775, its members disagreed upon the fundamental issue: for what purpose were the Americans fighting? The core dispute: should they pursue reconciliation or independence? Moderates wanted “redress of grievances.” Radicals wanted independence but balked at open advocation; public opinion sat not in their camp. Congress adopted Jefferson’s Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms. It listed American grievances, expressed loyalty to the Crown, and insisted upon self-government but not independence. The key complaint: Parliament’s insistence it could “of right make Laws to bind us in all Cases whatsoever.” The colonists fought not for independence, but “in defence of the Freedom that is our Birthright.”6

Congress declared a trade embargo, created a Continental Army in June 1775 and navy in October, improved the militia, raised defense funds, and, in November, a committee to communicate with European states. Congress believed Canada should be part of “the American union” and wanted control over the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and Mississippi River. Its actions and expansionist territorial aims didn’t align with seeking “redress of grievances.”7

To Britain, the value of the object was high. London insisted the rebels recognize Parliament’s supremacy and right to rule; the shape of British constitutionalism was at stake. King George III and others saw the American lands as the Empire’s jewel and believed losing them threatened national survival. On August 23, 1775, London issued a Proclamation of Rebellion. It forbade all trade with the rebellious colonies and allowed the capture of American ships, but London never abandoned efforts to craft a political solution.8

The conflict established one of the great traditions of American grand strategy: entering a war unprepared. Here, the Americans had little choice, but it took the nation’s leaders generations to correct this. When the war began, America possessed neither army nor navy. Each state had a regulated militia, but preparation varied, and their appearance when summoned was as unpredictable as their performance in battle. The presence of Continental Army troops usually helped both, but, if not used quickly, militia often went home.9 The seafaring Americans also had an enormous merchant fleet.

Assessment and Preparation

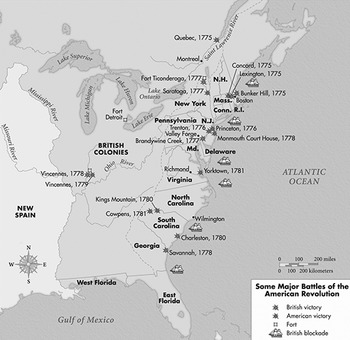

When fighting began, 2.5 million people lived in the thirteen colonies. (See Map 1.1.) Perhaps 15 to 20 percent were Loyalists. Others were pacifists, another 600,000 were African-American, generally slaves. Legions preferred neutrality. On June 14, 1775, Congress approved an army of 30,000. Theoretically, the Colonials could raise several hundred thousand soldiers, but this assumes widespread support for rebellion and a willingness to serve. Congress named as the army’s head Virginian George Washington, a militia veteran of the French and Indian War, respected political figure, and the only representative to wear a uniform to the Continental Congress. It established a board of war to run the conflict, one replaced by a secretary of war in 1781, and three military departments with their own armies, essentially the northern, middle, and southern, all under Washington’s overall command.10

Map 1.1 Principal battles of the American Revolutionary War, 1775–83. Universal Images Group North America LLC / Alamy.

London was unprepared, which gave the Americans a year to build their force. The British army in April 1775 numbered 27,000; 7,000 in North America. The population of England, Scotland, and Wales was 8 million, Ireland around 4 million. Britain possessed an enormous colonial empire and hired some 30,000 soldiers from six German states, a common practice. London’s task became subduing a vast area stretching from Maine to Georgia, and from the Atlantic Ocean to the Appalachians. The British estimated that with 50,000 men, and three to four years, they could defeat the rebels.11

In May 1775, Gage received 6,500 reinforcements and three Major Generals, Sir William Howe, Sir Henry Clinton, and Sir John Burgoyne. The Americans discovered the enemy’s plan to fortify the Dorchester Heights dominating Boston, and replied by entrenching on Breed’s and Bunker Hills on the Charlestown peninsula on the night of June 16. The British took the position on June 18 on the third assault but suffered 40 percent casualties.12 The British nearly always captured any Colonial position they wanted, whether field, fort, or city, but always paid a price in casualties their small army could hardly bear. Britain’s manpower limits made it susceptible to an attritional strategy.

Colonial Grand Strategy: The First Phase

Ideally, a government uses its elements of national power to achieve its political aims. But with their political aim being “redress of grievances,” meaning Britain addressing differences over taxation and political rights, some Colonials’ actions made questionable strategic sense.

Canada refused to rise despite Congressional appeals, and in June 1775 Congress prohibited its invasion. But Congress grew fearful that Britain controlling Canada would mean London raising the Indians, invading, and potentially isolating New England, and threatening the American army besieging Boston. Word that Canada’s governor general, Sir Guy Carleton, intended to recapture Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York (which the Americans had seized in May 1775), and the same region’s Caughnawaga Indians deciding to fight for King George galvanized Congress to act. It approved an invasion on June 27, 1775, aiming to convince Canada to join the rebellion. Driving Britain from Canada also meant Indian neutrality, while taking Montreal and Quebec would force London to abandon its forts in the American interior. American intelligence reported a light British hold on Canada and that its people would welcome the rebels as liberators. There were also fewer than 700 British troops.13

On August 20, 1775, Washington proposed supplementing Congress’ invasion with what became Benedict Arnold’s expedition up Maine’s Kennebec River to Quebec. To Washington, this would divert Carleton from Congress’s primary offensive under the capable Brigadier General Richard Montgomery. Montgomery departed Ticonderoga for Montreal in September with 1,000 men, took the city’s surrender on November 13, 1775, and, on New Year’s Eve, after uniting with Arnold, attacked the fortified city of Quebec in a blinding snowstorm. It was a debacle. Montgomery was killed and Arnold wounded.14

Meanwhile, Washington fought the war in Massachusetts. He had been promised an army of 20,000 but found on July 2 an unkept rabble of 14,000. Congress instructed him “to destroy or make prisoners of all persons, who now are, or who hereafter shall appear in arms against the good people of the United Colonies.” He was told to use his best judgment and given a directive that governed much of how he formulated strategy over the next eight years: to hold a council of war with his generals before conducting operations. Washington, who respected British skill and professionalism, and thought Colonial success required the same, began melding the militia and volunteers into a British-style army. Others believed the militia sufficient and a standing army a threat to Colonial freedoms, hurdles Washington had to overcome. He relied on militia in innumerable ways, including for internal security and local defense, but quickly realized their limits.15

Washington’s weakness in comparison to the enemy meant he could do little beyond prepare. But at the end of summer 1775, he launched naval forces by recruiting privateers (government-licensed raiders) to attack British merchant shipping, which Congress encouraged. Their primary task: seize vessels bringing provisions to the British in Boston. American privateers eventually took about 2,000 British ships. State navies and the establishment of the Continental Navy followed, as did the conversion of merchant ships to vessels of war and construction of new ones. The Colonials used sea power primarily to attack British commerce, as defensive military action on inland waterways, and in a few spectacular raids by John Paul Jones on the British Isles. After 1778, America’s French ally brought desperately needed naval power.16

Washington’s immediate concern remained Boston, where the guns of Britain’s fleet protected its entrenched force. In July 1775, Congress told Washington to expel the British from Boston; he searched for a way to win the war “by some decisive Stroke.” After nearly a year, and consideration of several risky schemes, the Americans placed cannon on Dorchester Heights, threatening the garrison and its ships. The British abandoned the city on March 17, 1776, sailing for Nova Scotia.17

The Colonials failed in Canada, but demonstrated creativity in contesting British power, particularly at sea. Something generally overlooked is that early in the war the Americans constructed a military strategy with related arms: the siege of Boston, commerce raiding at sea, and a two-pronged invasion of Canada.

Britain’s War: Reassessment and Strategy

After being driven from the thirteen colonies, Britain faced the challenge of conquering a territory of 360,000 square miles. The nearly 1,000 miles from Boston to Charleston is the distance between Antwerp and Madrid. Britain’s ocean supply line stretched 3,500 miles. Lord George Germain, the colonial secretary, dominated Britain’s war effort. He believed a rebel minority controlled America and that a quick, heavy blow would force the Americans into line and break Congress. This, combined with a blockade, would encourage people to turn to the Loyalists, who would secure British control.18

In October 1775, William Howe took command of the British forces stretched from Nova Scotia to Florida; Carleton held a separate Canada command. In February 1776, Lord Richard Howe, the general’s brother, was appointed to head the North American fleet. King George III failed to appoint a commander-in-chief of the army in America until 1778, producing a divided command. New England was considered the rebellion’s heart, and its recapture the quickest path to victory. In an offensive approved in January 1776, Howe planned to seize New York City, advance up the Hudson River, America’s most important water route, and link with Carleton’s forces pushing from Canada while securing the river crossings, a plan fed by French and Indian War experience. A two-pronged attack against Massachusetts would follow. Howe hoped to force a battle in New York, where Washington had moved his force, to crush the American army. This, he believed, was the quickest way to end the war.19

A New Aim: Sovereignty

As Howe and Washington prepared, the Continental Congress changed America’s political aim. On July 4, 1776, it became independence. Congress was now convinced both of its possibility and necessity. The failed Canada invasion furnished one catalyst. Britain’s determination to fight provided another. The king refused Congress’ Olive Branch Petition calling for an Anglo-American Union and virtual American autonomy and declared Congress illegal. Public opinion had also shifted, fed by Virginia governor Lord Dunmore offering freedom to slaves willing to fight the rebels, Britain hiring German mercenaries, and Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which argued vehemently for independence. Foreign assistance – meaning French – now proved indispensable. Only by declaring independence could America hope to secure this. France gained nothing helping an America that planned to reconcile with its mercantilist master; an independent America could at least offer its trade.20

The Declaration of Independence spelled out the Colonial political aims:

the Representatives of the united [sic] States of America, in General Congress … do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do.21

The changing of the political aim alters the war’s nature, which means reassessment should occur, with particular attention paid to the internal and external effects. This isn’t escalation. Aims change. Means escalate.

Diplomatic and Economic Strategy

In July 1776, Congress sought recognition from abroad using the lure of American trade. The US sought “free trade,” which meant trading “on equal terms with other nations.” Benjamin Franklin and John Adams drafted a treaty with two options to guide US representatives: reciprocal national treatment, which meant US trade would be treated as if conducted by citizens of that nation, and unconditional most-favored-nation status, meaning Americans paid the same tariff rates as others with this standing.22

Colonial Military Strategy: The Second Phase

In late May 1776, Washington and the Continental Congress decided General Washington “would make a maximum effort to defend New York.” Washington believed Britain’s major blows would fall in Canada and New York, with the enemy trying to seize the lakes in upstate New York and the Hudson, both critical for movement, communication, and supply, and unite their prongs. Worse, he thought America unprepared to meet them in manpower and armaments.23

But Washington believed surviving the 1776 campaign season would place the Americans “on such a footing as to bid defiance to the utmost malice of the British Nation and those in alliance with her.” The question was how. Washington hoped that if not victorious in the field he could at least force the British “to wade through much blood & Slaughter before they can carry any part of our Works, If they carry’em at all.” He planned to fight what he later called a “War of Posts.” He would sap British strength via attrition by fighting from fixed positions in New York City as the Americans had at Bunker Hill. American forces lacked the training and discipline to stand against the enemy in the open, but American leaders believed they had a chance behind fortifications. But as summer wore on, Washington grew pessimistic about defending New York City and its environs with forces dispersed sometimes 15 miles apart. Major General Henry Knox, Washington’s artillery chief, later described the flaw in the American decision to fight here: “Islands separated from the main by navigable waters are not to be defended by a people without a navy against a nation who can send a powerful fleet to interrupt the communications.”24

Howe’s troops began landing on Staten Island on June 3, 1776. They sat until August 22 – seven weeks – as the summer unwound. Instead of quickly forcing a battle, Howe waited for additional troops and equipment. He also faced a critical constraint: he had the bulk of Britain’s army and would receive only a few reinforcements, which fed his caution. He had intended to land on Manhattan and compel a battle but changed his operational plan after learning Washington divided his army between Long Island and Manhattan. As Britain controlled the waterways, Howe could choose where to fight. He also remembered Bunker Hill and knew the Americans had had nearly a year to fortify. He decided to first strike Long Island, methodically grind away the American forces (lowering his casualties by bringing superior numbers to bear), destroy the American army, seize territory, and erode Colonial morale. Combined with a blockade, his campaign would bring the Americans to the negotiating table, which aligned with his own desire for reconciliation, another factor underlying the shift. But this would take longer than his original plan, and time benefits the defender.25

On August 21, 1776, Washington reported intelligence that the British were finally “upon the point of striking the long-expected Stroke.” Washington had 19,000 troops, the British 31,000, who began landing on Long Island the next day. Howe then attacked Washington’s strategy. Instead of assaulting the American fortifications on Brooklyn Heights, he waged a cautious campaign that preserved his forces while decimating the Colonials. By the end of August, he had taken their Long Island posts and broken their morale. The militia proved particularly despondent and left in large numbers. On the night of August 29, 1776, Washington’s Long Island force escaped across the East River to Manhattan, protected by what many saw as a providential fog.26

Washington’s “War of Posts” was an example of scriptwriting in that success depended upon the enemy doing exactly as the Americans wanted as well as “the tacticization of strategy,” meaning substituting tactical, battlefield action for military strategy, meaning a larger idea for the use of military force.27 It is nearly impossible to achieve a political aim by depending upon tactical results.

While Washington fought Howe, the Northern Army, now led by Benedict Arnold, a former merchant and pharmacist from Connecticut, countered the British offensive from Canada. Arnold didn’t believe Carleton could advance up Lake Champlain before September because of the quantity of supplies needed for the fleet being built. Arnold advised fighting a delaying action to thwart the British until the following year by reinforcing Fort Ticonderoga and building a fleet on Lake Champlain. Arnold was ordered to delay the enemy until winter. On October 4, 1776, he fought the British to a standstill off Lake Champlain’s Valcour Island, slipping the noose under a night fog. He escaped southward to Crown Point, New York, burned his ships, and led his men to Ticonderoga. On October 20, the first snow fell. Carleton reached Ticonderoga, refused to attack, and withdrew north in early November. British and American commentators have credited Arnold with saving the Colonial cause.28 One wonders about the result if Carleton’s army had joined Howe’s.

A Strategic Shift: Protracting the War with a Fabian Strategy

On September 7, 1776, Major General Nathanael Greene launched the line of thought underpinning a new American strategy:

The City and Island of New York are no objects for us; we are not to bring them in Competition with the General Interest of America. Part of the army already has met with a defeat; the Coungry [sic] is struck with a pannick; any Cappital loss at this time may ruin the cause. Tis our business to study to avoid any considerable misfortune, and to take post where the Enemy will be obliged to fight us and not we them.29

In this last sentence of the lapsed Quaker merchant from Rhode Island we find the beginnings of the American Fabian strategy: fight where advantageous and avoid a decisive defeat that would fatally wound the cause. The idea, a form of a strategy of protraction, came from Roman history. Fabius Maximus Cunctator, or Fabius Maximus “the Delayer,” was a Roman general during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC). During Hannibal’s invasion of Italy, unable to defeat the Carthaginians in the field, Fabius simply refused to fight a major battle. He kept his army in hilly terrain to thwart Hannibal’s cavalry superiority, while bleeding the enemy with small detachments and raids to erode their strength and prevent their recruiting.30

Washington valued Greene’s advice. This – and not a little desperation – produced a new strategy. Washington informed Congress of its risks and rewards:

I am sensible a retreating Army is incircled with difficulties, that the declining an Engagement subjects a General to reproach and that the Common cause may be in some measure affected by the discouragements which it throws over the minds of many; nor am I insensible of the contrary effects, if a brilliant stroke could be made with any Probability of success, especially after our loss upon Long Island: but when the fate of America may be at stake on the Issue; when the Wisdom of cooler moments and experienced Men have decided that we should protract the War if Possible; I cannot think it safe or wise to adopt a different System, when the season for Action draws so near a close.31

Washington’s shift was perhaps the war’s critical strategic move. In summer 1777 his aide, Alexander Hamilton, penned a cogent assessment of American strategy and its effects on the British, one worth quoting:

I know the comments that some people will make on our Fabian conduct. It will be imputed either to cowardice or weakness: But the more discerning, I trust, will not find it difficult to conceive that it proceeds from the truest policy…. The liberties of America are an infinite stake. We should not play a desperate game for it or put it upon the issue of a single cast of the die. The loss of one general engagement may effectually ruin us, and it would certainly be folly to hazard it, unless our resources for keeping an army were to end, and some decisive blow was absolutely necessary; or unless our strength was so great as to give certainty of success. Neither is the case. America can in all probability maintain its army for years…. It is therefore Howe’s business to make the most of his present strength, and as he is not numerous enough to conquer and garrison as he goes, his only hope lies in fighting us and giving a general defeat in one blow…. Their affairs will be growing worse – our’s [sic] better; – so that delay will ruin them. It will serve to perplex and fret them, and precipitate them into measures, that we can turn to good account. Our business then is to avoid a General engagement and waste the enemy away by constantly goading their sides, in a desultory teazing way.32

Washington chose a tough path, one for a weaker force. Success required cooperation from other commanders and support from political leaders and the people. A Fabian strategy strains the state’s fibers by demanding an irreplaceable commodity: time. Success requires resisting the temptation to fight a major battle too early or under disadvantageous circumstances. This was difficult for the aggressive Washington. It also demands incremental successes. Protracting a war means betting your people will support the war longer than the enemy’s. The clock is ticking. Successes slow your clock and accelerate the enemy’s. It also requires keeping an army in the field to threaten the opponent and limit his or her options. Victories help here as no one joins an army that only loses and runs away. It also requires sanctuary, someplace to run to, which the colonial vastness provided. Timely flight requires good intelligence. Washington did his utmost to secure agents and information, and unknowingly echoed Sun Tzu’s Art of War: “I beg you to take every possible means in your power, to find out the designs of the Enemy and What their plan of Operation is – do not hesitate at Expence.” This observation on Fabius’ war fits Washington’s: “Nothing makes greater demands on loyalty and morale than a plea for patience, a promise of a long war, and a failure to strike back while a foreign army occupies territory of your friends and threatens your own.”33

Though the Americans decided in September 1776 to adopt a Fabian strategy, both Washington and Greene initially failed to restrain their natural aggressiveness or abandon the War of Posts. During September’s second week they dithered over defending New York City and Manhattan Island’s Fort Washington. Greene’s insistence helped assure the latter and the Americans fought for a fixed position, suffering one of their worst defeats of the war when it fell on November 16. Brigadier General Thomas Mifflin complained bitterly that the Colonials should have “adhered to the Fabian plan.”34

Howe, meanwhile, mounted a cautious campaign on Manhattan. His forces landed at Kip’s Bay on September 15, between the divided Americans. But Howe’s pauses and dilatoriness squandered several opportunities to destroy the fractured American forces. Washington began abandoning Manhattan on October 18. After 125 days, Howe achieved the operational aim of his campaign – the capture of New York City – but he failed in his most important task: to destroy Washington’s army. Tench Tilghman, Washington’s secretary, wrote: “we have done greatly in stopping the career of Monsr Howe with the finest army that ever appeared in America, opposed to as bad a one as ever appeared in any part of the Globe.”35

In autumn 1776, Washington’s army fled Howe’s pursuit by retreating across New Jersey, which passed into British hands. Washington, beaten but not defeated, looked for opportunities to strike back. He pushed his commanders to gather troops and information in the hope of recovering their fortunes. He looked for chances to hurt the enemy with militia, issuing mid December orders to various commanders to use detachments to harass the British whenever possible. The partisan war was about to heat up.36

Washington and his generals possessed great familiarity with the military manuals addressing “Partizan Warfare” or Petite Guerre (Little War). Washington first suggested this mode of fighting in July 1776, proposing a “Partizan Party” for operations against the British on Staten Island.37 It fed his Fabian strategy. The Americans used militia and detachments of regular troops to harass the British, ambush their messengers and foraging parties, attack their supply lines, and so on, stretching, tying down, and depleting the enemy’s resources and, more importantly – manpower. “Partisan War” should not be confused with modern-day theory on guerrilla warfare, a common mistake because the tactical implementation is similar.

In December 1776, the American effort reached its lowest ebb. On December 12, a desperate Congress entrusted Washington with near-dictatorial powers on defense issues for the next six months. Thomas Paine’s The American Crisis appeared on December 19. His words again decisively strengthened public opinion favoring the American cause. On December 20, Washington told Congress: “We find Sir, that the Enemy are daily gathering strength from the disaffected; This strength, like a Snowball by rolling, will increase, unless some means can be devised to check effectually, the progress of the Enemy’s Arms.”38

Facing the dissolution of his army because of expiring enlistments, Washington famously crossed the Delaware River from his Pennsylvania base and attacked Trenton and Princeton in late December, scoring two victories that proved enormous boons to Colonial morale and the American cause. Supplementing Washington’s offensive was militia with orders to prosecute a partisan war against the British occupation of New Jersey. In the winter campaign that followed, Washington excelled. He maintained his regular army, which forced Howe to concentrate his, and used intense partisan activity to recover most of New Jersey. By winter’s end, Howe retained only Brunswick and Amboy on New Jersey’s shore, and had only 14,000 troops fit for duty.39

The 1777–78 Campaign

By mid January 1777, Howe planned to take Philadelphia, the erstwhile Colonial capital, and defeat Washington’s army, seeing here the keys to victory. Meanwhile, Major General Burgoyne proposed a plan for an advance from Canada supported by a light push down the Mohawk Valley. He intended to take the lakes in upstate New York and Fort Ticonderoga, and then, depending upon circumstances, move down the Hudson to link with Howe, thus reducing New England. Germain approved both plans. Accompanying his failure to coordinate between the commanders was an understanding that Howe would not support Burgoyne’s march on Albany. Britain also lacked a plan for after reaching the city.40

Washington’s preservation of his army and ability to hang on Britain’s heels and strike detachments made it impossible for Howe to safely move the roughly 100 miles overland against Philadelphia. To hedge against Washington attacking Burgoyne and enable him to operate on the Hudson if Washington moved north, Howe took his army to Philadelphia by sea via the Delaware River. Howe hoped to destroy Washington’s army by forcing a fight for Philadelphia. In concentrating his force, he abandoned New Jersey and its Loyalists to insurgent retribution.41

Washington, unsure of British plans, feared the Canada drive was a feint to draw off his army. Taking the bait would leave Philadelphia to Howe, which he suspected was the general’s operational objective. He dispatched some regulars northward and ordered them supplemented with militia. Howe, meanwhile, spent the spring and summer preparing, and landed south of Philadelphia on August 25. Washington wanted to avoid battle and not risk his army for any geographical position, even Philadelphia. But public opinion and political pressure dictated otherwise. He met Howe’s 16,000 men with 14,000 of his own at Brandywine on September 11, 1777. Washington lost, but Howe failed to destroy the American army. Howe dispatched Lord Charles Cornwallis to seize Philadelphia. Howe’s slowness and decision to move by sea meant he ended the campaigning season in Philadelphia instead of helping Burgoyne.42

Burgoyne certainly needed it. His campaign began in late June. Determined American resistance and a relief column stopped the Mohawk Valley arm. Meanwhile Burgoyne, commanding 8,000 men, took Forts George and Ticonderoga, then Fort Edwards on the Hudson River, 30 miles north of Albany. He could have advanced immediately and seized the city, but paused to gather thirty days of supplies, then pushed southward on September 13. The rough terrain and an unnecessarily large baggage and artillery train slowed his movements. The American response from the beginning was to dispatch militia to hang on his haunches and tail. They soon numbered in the thousands, driven by Burgoyne’s threats to unleash the Indians and the murder of Jane McCrea by Burgoyne’s Indian allies, something American leaders heavily publicized. They cut Burgoyne’s communications and destroyed foraging parties as the Americans massed 11,000 regular troops and militia. Burgoyne launched the Battle of Bemis Heights on September 19 and attacked the Americans again at Freeman’s Farm on October 7. The Americans under Major General Horatio Gates delivered key Colonial victories and Burgoyne surrendered at Saratoga on October 17, 1777.43

If what came to be called Britain’s Hudson Valley plan had resulted in control of the Hudson line and the highlands as hoped, Benedict Arnold insisted it would have allowed the British to strangle Washington’s army by depriving it of supplies and reinforcements. Even if true, Britain would have lacked sufficient troops to subdue New England and exploit their success. Moreover, Washington’s army proved quite capable of starving on its own. It went into winter quarters at Valley Forge shortly before Christmas 1777 and was soon reduced to famine and rags. Congress lacked the authority to tax to fund the army, and most of the states refused to levy their people to support it or fill their enlistment quotas. Despite the obstacles, a drilled American army of 12,000 emerged in the spring.44

Global War, 1778–83

It is a common misconception that Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga produced the French decision to enter the war. Paris had already concluded that March 1778 was its optimal entry time as its naval rearmament plan would be complete. France also needed Spain by its side, and Spain proved a tough sell. Madrid feared the American revolt set a bad example for its extensive empire and saw no reason to join. Word of the British surrender at Saratoga helped France’s argument.45

Diplomatic and Economic Strategy

In January 1778, in response to French inquiries, the Americans replied that a treaty of commerce and friendship with Paris would stop any Colonial accord with London granting less than independence. The French proposed this treaty and a military alliance allowing France to decide when it entered the war. The Americans preferred immediately but grasped the offer, signing two treaties on February 4, 1778. France recognized US independence, and both agreed to not make peace until America secured this aim. Later, France sealed its recruitment of Spain with a covert April 1779 pact. The coalition’s members had different political aims, some disliked by their allies, a reality of coalition warfighting. For example, Spain sought Gibraltar (among other things) but viewed American independence as a threat to its imperial possessions. France sought chiefly to weaken Britain and strengthen its position in Europe. Upon learning of America’s secret treaties with France, Lord North tried to end the war by repealing the “Intolerable Acts,” granting the colonies freedom from Parliament’s taxes, and dispatching what became known as the Carlisle Commission to negotiate. The Americans rebuffed it all. France broke relations with Britain in May; its war began on June 16, 1778.46

With the entry of France, Spain, and later the Netherlands, which Britain attacked in 1780, partially because of its support for the colonists, a localized colonial rebellion became a global war. Clandestine French economic and military assistance had already helped secure the victories that led to Burgoyne’s Saratoga surrender. But now Paris and Madrid provided the outside support key to an insurrection’s success and everything the Colonials lacked: money, skilled troops, and naval power. After 1778, America’s finances were so shattered it’s doubtful it could have maintained anything other than guerrilla forces without French funds. The Colonial cause might have perished without foreign assistance.47

Financing the war proved difficult. Congress had no authority to tax, yet financial responsibility, and Americans weren’t ready to give them power to do what they were rebelling against. Congress resorted to printing money – $241,550,000 – before stopping in 1780. Abundance destroyed the currency’s value and fueled inflation, something Franklin justified as a fair form of taxation because it hit everyone’s purchasing power. Subsidies came from France and Spain, and later loans, including from Holland and private sources. Congress eventually began issuing certificates – essentially IOUs – for goods needed by the army. Meanwhile, the war’s pressures encouraged the expansion of the American industrial base, particularly in iron and steel.48

Efforts to place the new nation on a sound economic footing presaged future arguments about government’s economic role. In 1780, Hamilton proposed a national bank with no hope of approval. Financier Robert Morris suggested Congress assume the public debt and gain the power to levy taxes. He also called for a national bank, which Congress established. It opened in January 1782, though undercapitalized and thus incapable of fulfilling Morris’ hope that its notes become a national currency. The 1778 Franco-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce granted France most-favored-nation trading rights, but the US only received this in French national ports and not its colonial ones. From the US side, the problem was that each of the thirteen states regulated its own trade.49

The War in the North

In the wake of Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga, certain of France’s entry and fearing Spain’s as well, the British reassessed and concluded America could not be reconquered, partially because this would require 80,000 men, a number impossible to raise. They believed the navy had spent too much time cooperating with the army instead of halting shipping going to and from America. Both needed expanding. Britain concluded, correctly, that France had no interest in regaining its colonies in America and would instead strike the West Indies. This led to the decision to take 10,000 soldiers from America, which forced Howe’s evacuation of Philadelphia, and redeployment of most of Britain’s heavy ships from America.50 Outside support quickly paid dividends for the rebels.

Washington believed London needed another blow on the scale of Saratoga before it would quit. By 1779, he had chosen New York City, London’s primary stronghold and base in North America. Washington wanted a French fleet to blockade the harbor while an American army reduced the city. This remained his focus for the next three years, but his French ally prioritized Europe and the Caribbean. Poverty limited Washington’s ability to mount offensive operations.51

Circumstances, though, pushed Washington to act against the Iroquois Confederation. Throughout 1778, fighting between Loyalists, Colonials, and their respective Indian allies engulfed the frontiers of New York and Pennsylvania. Atrocities by both sides were common. Washington hoped to drive the Iroquois into neutrality, eliminate their lands as British supply sources, and force London to deploy more men to defend Canada. Washington successfully feinted an invasion of Canada and sent an army of 4,000 into Iroquois territory. Its orders were to “lay waste all the settlements around … that the country may not be merely overrun but destroyed,” and to take as many prisoners as possible, regardless of age or sex. The August–September campaign didn’t achieve Washington’s objective but maimed the Iroquois ability to make war. The 1779 campaign broke the Iroquois Confederation and helped ensure America dominated the Trans-Allegheny. Similarly, in 1776–77, the four southern states – Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia – crushed a Cherokee rising.52

Britain’s Southern Campaign

Britain’s Southern Strategy emerged from its post-Saratoga reassessment. London judged the southern colonies more valuable than their northern brethren because they supplied naval stores and food. The northern states were a market for British goods, one London believed would return after the war. Britain’s leaders decided to seize America south of the Potomac River. They believed it harbored numerous Loyalists who would turn out for the king – if enough British troops appeared to protect them – and saw the region’s Indians and slaves as potential allies. Controlling the south would cut the primary transit routes for overseas trade supporting the rebellion, rob the north of desperately needed resources, demoralize it, and make it easier to reduce. Under Germain’s plan, a small British force would liberate an area, train Loyalist troops to hold it, then push north and repeat. This was a version of what later eras called “Clear, Hold, and Build.” Germain also ordered raids on the New England coast to destroy rebel supplies and impress upon Americans the war’s reality.53

The British offensive began in South Carolina (they seized sparsely populated Georgia in 1778). Major General Benjamin Lincoln commanded the Americans. He had served under Washington and understood Fabian War but disliked this and decided to hold Charleston rather than preserve the army by withdrawing into the interior. Sir Henry Clinton, who now commanded in America, began landing troops near Charleston on February 11, 1780. He wanted Charleston intact as a point for gathering Loyalists, and exploited Britain’s technical superiority by besieging the city. It began on April 1, 1780. The 5,500 defenders surrendered on May 12. Banastre Tarleton’s British force then defeated the Americans at Waxhaws on May 29, killing prisoners to terrorize the Americans. The twin victories secured a base for Britain’s campaign and destroyed America’s army in the south, enabling Britain to disperse its troops to hold down the cleared area. Clinton began pacifying South Carolina and implementing Germain’s plan.54

Clinton believed Loyalist vengefulness would undermine the reestablishment of Royal rule and issued two proclamations to thwart this. On June 1, 1780, he offered pardons to anyone taking an oath of allegiance. This angered Loyalists, who wanted rebels punished. On June 3, Clinton released prisoners of war from their paroles and restored their rights while requiring an oath of loyalty and their support. Clinton’s proclamation forced them to choose between serving the king or fighting him. After setting the house on fire, Clinton gave the keys to Cornwallis and his 4,000 men and sailed for New York. South Carolina erupted in a Colonial–Loyalist civil war. The British fed the conflagration by attacking the plantations of Thomas Sumter and Andrew Pickens, bringing back into the field two former partisan leaders. Congress, meanwhile, dispatched Gates south with an army. Gates, like Lincoln, also abandoned Washington’s Fabian strategy. Cornwallis crushed Gates’ force of 4,000 with one half the size on August 16 at Camden, South Carolina.55

The British had again destroyed formal Colonial resistance in the most southern colonies. But Gates’ presence had inspired insurrection and Britain’s pacification effort began coming apart. Cornwallis became skeptical about the Loyalists gaining the ability protect themselves without regular troops and concluded that securing South Carolina required controlling North Carolina. He led his main force toward Hillsborough, North Carolina, crossing the state line on September 26. A second prong of 1,000 Tory militia marched north from the post of Ninety-Six on the South Carolina frontier under the command of Major Patrick Ferguson. Ferguson’s force was a diversion that also cleared the rebels from eastern South Carolina, many of whom fled over the Appalachian Mountains. On September 12, 1780, Ferguson threatened them with hangings and fire unless they submitted. This provoked one of the strangest incidents of the war. The inhabitants decided to save Ferguson the trip and formed an army in the Appalachian wilderness. Ferguson began withdrawing toward Cornwallis but decided to make a stand at King’s Mountain, South Carolina. On October 6, the Over the Mountain Men killed Ferguson and scattered his army. Cornwallis retreated into South Carolina to hold it.56

Washington, meanwhile, worried that if Britain conquered North Carolina, Virginia would soon fall. On October 14, 1780, Washington offered command of the Southern Department to Nathanael Greene. Greene had served with Washington since the siege of Boston and for the two years prior was his quartermaster general. In this era, this meant not only managing logistics but also everything pertaining to moving and deploying the army. Before going south, Greene arranged the supplies and weapons he would need, a difficult task. The war in the south was different from that in the north, which Greene understood. There were fewer men to recruit, fewer artisans to help keep the army going, and large numbers of Loyalists. Most supplies had to come from the north, organized American resistance was all but gone, and the region suffered from war weariness. Georgia and South Carolina lacked Colonial governments, which were critical for furnishing troops and supplies; North Carolina had a weak one. Cornwallis now had 8,000 men, reinforcements coming, and plans to recruit more Loyalists and extend his conquest to North Carolina and Virginia while holding South Carolina and Georgia with a string of fortified positions.57

In Hillsborough Greene found a small detachment of Continental troops and 1,200 more at Charlotte with about 1,000 militia. Greene began rebuilding. An asset he did possess were partisan bands.58 The question for Greene was how to use his scant forces to overcome the enemy. As one architect and a chief implementer of America’s Fabian strategy, Greene knew very well what to do. He was accustomed to acting from a position of weakness and making – he said in a biblical allusion – “bricks without straw.” In January 1780, he wrote:

The Salvation of this country don’t depend upon little strokes, nor should the great business of establishing a permanent army be neglected to pursue them. Partizan strokes in war are like the garnish of a table …They are most necessary and should not be neglected, and yet, they should not be pursued to the prejudice of more important concerns. You may strike a hundred strokes and reap little benefit from them, unless you have a good Army to take advantage of your success…. It is not a war of posts but a contest for states.59

He also understood how to use his regular and irregular forces, and what he risked:

if both are employed in the partizan way until we have a more permanent force to appear before the enemy with confidence, happily we may regain all our losses. But if we put things to the hazard in our infant state before we have gathered sufficient strength to act with spirit and activity and meet a second misfortune all may be lost and the tide of sentiment among the people turn against you.60

Greene realized the tough constraints under which he operated. He faced dire logistical challenges which he made herculean efforts to overcome, and his enemy was superior both in numbers and skill. Greene did what few would advise: he divided his army, placing a significant element under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan. He explained why:

It makes the most of my inferior force, for it compels my adversary to divide his, and holds him in doubt as to his own line of conduct. He cannot leave Morgan behind him to come at me, or his posts of Ninety-Six and Augusta would be exposed. And he cannot chase Morgan far, or prosecute his views upon Virginia, while I am here with the whole country open before me.61

Cornwallis replied by sending 1,150 men under Tarleton to eliminate Morgan while marching to block the retreat of any survivors. He would then move against Greene. Morgan destroyed Tarleton’s force at the Cowpens on January 17, 1781. Greene united his forces and retreated north. Cornwallis pursued. Greene began massing troops and supplies with the intention of fighting at Guilford Courthouse. He dispatched his partisan leaders to lead militia against Cornwallis’ rear areas and prevent the Loyalists in South Carolina from gathering. Cornwallis suffered the same problem as other British generals: the strength of the Continental Army was not a mortal threat, but wherever it appeared clouds of militia often turned out in support. And when Cornwallis concentrated against the Continentals, he left the countryside to American militia and irregulars.62

Greene resolved to retreat to Virginia, if needed. Cornwallis’ aggressive pursuit combined with Greene’s rapid withdrawal to rupture Cornwallis’ supply lines, a devastation Greene furthered by sweeping the countryside of food. Bolstered by reinforcements, on March 15, 1781, Greene’s 4,200 men met Cornwallis’ 2,000 at Guilford Courthouse. Cornwallis’ victory proved pyrrhic; he suffered 25 percent casualties, losses almost impossible to replace. Tarleton considered Greene’s decision to give battle wise: an American victory would see Cornwallis’ destruction while defeat meant little.63

Cornwallis withdrew to Wilmington, North Carolina, to resupply. Greene plunged into South Carolina as Cornwallis marched to Virginia to join the British forces there. Greene fought the British on several occasions, losing every time. But he forced British abandonment of many South Carolina posts. Greene implemented an aggressive form of Washington’s Fabian War. He preserved his army and maintained the initiative despite being on the defense. He took much greater risks than Washington and could do so because neither he nor his army weighed on American public opinion as much as Washington and his.64

Military Victory: Yorktown

Cornwallis’ arrival in Virginia helped set the stage for the war’s dénouement. He received orders to choose a safe post and send all the troops he could to New York City because Clinton feared a descent by Washington and French General Jean-Baptiste Rochambeau. Washington certainly wanted to take the city and kept his attention on it into the summer of 1781 despite pleas from the governors of South Carolina and Virginia to march south. Rochambeau received word on May 6 that a French fleet was heading to North America. Rochambeau convinced Washington to abandon their plans for attacking New York City and instead strike the British in Virginia. Washington agreed. On September 5, 1781, the French fleet wrested control of the Chesapeake from the British while the Franco-American forces moved to besiege Cornwallis at Yorktown. Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781.65

Political Victory: The Peace

Lord North told the king it was impossible to continue the war because there was no political support. King George remained convinced losing America would destroy Britain as a great power and resisted making peace. Germain believed they could fight on and secure a settlement based upon what Britain held. By March 1782, North had lost the backing of the House of Commons and resigned. The replacement government ended with the death of its leader in four months, but July saw William Petty, Lord Shelburne, become first minister. He and his predecessor were both determined to make peace.66

The problem for all the powers was how. The complexities of peacemaking demand consideration of three key, intertwined factors: the political aims of the combatants, how military force should be used, and how the peace will be secured. The number of nations involved, and that each prioritized its own political aims, complicated the process. For example, the Americans wanted independence, but Spain preferred a colonial dependency that kept Britain and America bickering and was exploitable by Paris and Madrid.67

The Americans insisted they had achieved their aim of independence and wanted this enshrined in the final accord. Congress instructed America’s delegates to consider France’s views but to secure recognition of independence before negotiating with Britain to end the war. John Adams advised his fellow delegate, John Jay, to demand “a sovereignty universally acknowledged by all the world.” In the end, the US representatives seized the chance London offered and made peace with Britain without France – a contravention of the 1778 accord. Franklin at least notified France’s foreign minister the evening before the signing. The September 20, 1783 treaty awarded America substantial territory, and Britain acknowledged the “United States” as “free, sovereign & Independent States.”68

Some Conclusions

The American triumvirate of sovereignty, security, and expansion all mattered. But sovereignty – especially after July 1776 – mattered most of all. American strategy became largely reactive, something not unusual for a weaker power. Washington and others eventually developed a military strategy that helped deliver independence – protraction via a Fabian approach. Sticking to it produced incremental successes and tactical defeats, diverging produced tactical, operational, and strategic disasters in New York and South Carolina. But this strategy alone may not have brought the US success without France, something secured by American diplomacy. The insurgent almost always needs outside support. French economic, military, and diplomatic assistance proved pivotal and arguably indispensable.

Towards Constitutional Government, 1783–89

The United Colonies achieved independence, but the footings were shaky. It was governed via the 1781 Articles of Confederation, which restrained Federal control and vested power in a state-appointed Congress that could impose neither tax nor tariff. But imbuing the independence generation was “a certainty of their future greatness and destiny.” It believed their new government would be an example to the world and agreed with Thomas Paine that “We have it in our power to begin the world over again.” Idealism. Religious faith. Pragmatism. Ambition. A refusal to play by a corrupt Old World’s rules. These underpinned much of what the fledgling US would do and shaped what it would become.69

This new nation was weak but fortunate that among its adversaries – Britain, Spain, and the Indians – only Britain could mount an existential threat. The US also enjoyed enormous geographical advantages. An assessment better fitted for later days makes this point: “On the north she had a weak neighbor; on the south, another weak neighbor; on the east, fish, and on the west, fish.” Historian C. Vann Woodward argued America often enjoyed “free security” because of its geographic position and the British navy, which someone else paid for.70 There is some truth to this, but the British fleet didn’t protect US commerce from predation – particularly British.

Even before the peace terms were implemented, the US embarked upon what became a traditional element of American grand strategy: disarming at the end of a war. Four days after the September 20, 1783 signing of the Treaty of Paris, Congress ordered Washington to begin demobilization. After the British withdrew from New York, the army shrank to 600. By June 1784, it numbered only eighty-three privates and a handful of officers above captain’s rank. Maintaining even a small postwar army provoked bitter Congressional debates related to costs and traditional Colonial fears of a standing military. The navy was disbanded, Congress selling the last ship in 1785.71

Britain attempted to beggar the US via trade. A weak Confederation government proved to London it had no reason to grant America’s demand for trade reciprocity. London prohibited direct US imports into the West Indies from July 1783, mauling New England’s fishing and shipping industries. British merchants buried the US with cheaper manufactured goods while London prevented export of anything that would help the US develop native industry. British dumping contributed to “an economic depression worsened by the massive debt accumulated during the war.” One reason John Adams pressed for a stronger central government was the desperate need to regulate trade.72

Adams was far from alone. American weakness underpinned a litany of troubles – fear of the Indians; an inability to enforce treaties and field military forces; an incapacity to address economic and trade issues; fears of secession and disintegration; and Daniel Shay’s Rebellion in 1786–87, a revolt by destitute farmers unable to pay their debts – all of which helped bring about the Constitutional Convention (1787–89).73

The new nation’s ideological foundation rested upon an emphasis on God-given natural rights detailed in the Declaration of Independence: “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” But “Liberty,” which free peoples particularly valued, always faced threats from a lack of individual restraint and government temptation toward oppressive control. Only the “rule of law” protected free people from both dictatorship and chaos. The Constitution addressed these fears via the separation of powers between Congress and the president, particularly by dividing control of the military between the two. Forestalling fear of Congress having too much power over the states was an amendment to the new Articles of Confederation granting the states sovereignty in everything not expressly allotted to Congress, which was composed of a proportionally elected House of Representatives and a Senate of two appointed (until 1913) representatives from each state. The Constitution granted Congress many powers, including the “power of the purse,” the right to tax, and pass customs duties. Treaty-making lay with the president, but the Senate held ratification rights. An independent judiciary formed the third branch. Up to the time of the Civil War, the US possessed no institution dedicated to war planning or the crafting of anything today considered military strategy.74

The George Washington Administration, 1789–97

George Washington assumed office as the first president on April 30, 1789. What his administration wanted most was peace. This was necessary to consolidate American sovereignty over its possessions, particularly in the Northwest, and to firmly establish the new government. The nation was also too broke to fight.75 The first cabinet was small: Thomas Jefferson as secretary of state, Henry Knox as secretary of war, and Alexander Hamilton as secretary of the treasury. Hamilton’s brilliance, energy, and intimate relations with Washington developed through service with the general during the war, made him the dominant figure of the administration. He was also arguably America’s first grand strategist.

The Assessment

In his first annual message, delivered on January 8, 1790, Washington said the security of the US meant the nation needed to be armed but also “promote such manufactories as tend to render them independent of others for essential, particularly military supplies.” For this, it needed its own industrial base. What ensued was a struggle over government support for industrial development between commercial and industrial interests in New England and the mid Atlantic states against Southern agriculturalists. Washington believed it a governmental and personal duty to support US industry and encouraged Americans to do the same.76

Overall, Hamilton’s ideas on government and commerce had more effect than those of anyone else of his time other than Thomas Jefferson. Hamilton saw near limitless potential in America’s future and believed America would become a great naval and merchant marine power, giving it leverage economically and in foreign relations and, eventually, “by a steady adherence to the Union, we may hope, ere long, to become the arbiter of Europe in America, and to be able to incline the balance of power in this part of the world as our interest may dictate.” Historian Edward Meade Earle wrote of Hamilton’s approach: “Surely, this is Realpolitik of a high order and shows that a strategy for America in world politics was evolved by the fathers of the Republic.”77

Economic Strategy

The economic challenges were enormous and can be divided into intertwined internal and external threats. Hamilton brought to the task a driving intellect and deep knowledge of economic thought, including the ideas of Adam Smith. His greatest test was the national debt crisis, but America also lacked a liquid money supply. Hamilton saw that he could use the debt to create and back money by allowing banks holding government bond debt to issue currency. These same bonds also collateralized loans, increasing available capital. Hamilton successfully fought for the Federal government to assume state debts from the war as a means of binding the new union.78

The Founders preferred a version of commerce they called free trade, one perhaps better branded reciprocity or open trade. America’s leaders did not expect tariff-free trade as tariffs were a standard source of government revenue, but they wanted the ability to trade anywhere without having to pay higher duties than anyone else. This desire bumped against the closed, mercantilist system of the British Empire in which Britain preferred to import raw materials from its colonies and export to them finished goods. Simultaneously, American leaders worried about national defense and its provision, a lesson derived from the war.79

Tariffs can raise revenue as well as protect key industries; the first tariff, signed into law on July 4, 1789, did both. But Hamilton wanted a diverse tax structure because in wartime import revenue would disappear. Tariffs became the primary source of government income for more than 100 years – and among the most contentious. Every region had its own interests and thus varying ideas regarding what should or shouldn’t suffer a tariff. Only slavery proved more politically divisive.80

Hamilton secured the chartering of a national bank – the Bank of the United States. He stressed the necessity of firm finances that gave the country sound credit, factors critical for national security and development. Banking was unfamiliar to most Americans, which made Hamilton’s national bank revolutionary. The Bank’s most important function was issuing paper money. Its notes were essentially loans to private citizens and provided a circulating currency for a people lacking silver and gold specie. Government backing, based upon tax revenue, kept currency from depreciating or being exchanged for hard money. The Bank regulated the money supply by overseeing state banks.81

Building domestic industry was to Hamilton not only a source of national wealth, but a key element of national security. The nation’s defense ability hinged upon its capacity to arm and supply itself against foreign threats. Hamilton thought that as long as America lacked a navy to protect its commerce, it relied on overseas trade it could not protect. Hamilton’s 1791 Report on Manufactures proposed an economic program to make America “independent of foreign nations for military and other essential supplies.” Washington supported it and urged Congress to do the same. The report “imaginatively contested much conventional wisdom by suggesting that domestic commerce, that is, Americans trading with one another, might be as valuable to the prosperity of the country as international commerce.” This would help create a larger internal market for goods and agricultural products as agricultural workers became industrial laborers. Hamilton wanted an America strong enough to face the Europeans as an equal but knew this would take at least three or four decades. He disagreed with the physiocrats – economists who believed commerce brought peace – thinking trade more likely to cause than prevent wars. Hamilton believed that since fledgling US industry stood no hope of competing with developed British counterparts, American business should be protected and encouraged through tariffs and other restrictions. Annual purchasing contracts could support American arms manufacturers. Hamilton preferred targeted subsidies to tariffs, but tariffs were politically palatable.82

The new system – a national bank and government funded by tariffs that were sometimes protective – made possible administration borrowing during emergencies such as wars. Tariff revenue enabled payment of US debts, and between 1789 and 1794 America transformed from financial pariah to having a higher credit rating than any European nation, but it took until 1796 before revenue covered government expenses and debt service.83

Diplomatic Strategy

The French Revolution began in 1789. When Britain declared war on France in February 1793, Washington put to his cabinet the question of how the US should respond under the terms of the 1778 alliance with France as it required America to help defend France’s colonies in the West Indies. Hamilton insisted that it only committed the US to a defensive war, and that the alliance and the other treaties were as dead as the French government and monarchy with which they had been made. Secretary of State Jefferson argued the agreements were between France and the US, regardless of government. Paris rescued Washington from having to act. A weak US ally with no substantive navy was no help to Paris against London, but a US at peace meant American ships supplying the West Indies and France. Washington declared US neutrality on April 22, a decision most Americans supported, including Hamilton and Jefferson.84

The Anglo-French war produced internal political division that birthed America’s first political parties. The Democratic-Republicans, agrarians led by Jefferson and James Madison, hated Britain and favored France. The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, and supported by the merchant class, particularly from New England, leaned British. They despised the French Revolutionaries, especially their violence, and feared Britain’s power to destroy American trade and deny capital for economic development. Their battles were bitter, giving immediate lie to American political disputes having ever stopped at the water’s edge.85

The Anglo-French War created dangers for America. Early 1794 saw Britain begin seizing US ships and forbidding American trade with French possessions in the Caribbean. Congress responded with a thirty-day embargo on all US shipping to foreign ports. Paris retaliated against American vessels destined for Britain by taking their cargos. Anti-British sentiment grew, and war clouds loomed, but Hamilton encouraged Washington to negotiate as war would be disastrous economically. In the 1794 Jay Treaty, London agreed to evacuate the frontier forts it had earlier refused to abandon, open some of its West Indian ports to US trade, and grant America most-favored-nation trade status with the British Isles. But American concessions included recognizing Britain’s right to confiscate material transported by an enemy nation on a neutral ship. The deal also failed to protect US sailors from being forced into the Royal Navy via impressment. The concessions made the deal politically dicey, and Washington kept it secret as long as possible. Washington’s Democratic-Republican political opponents accused the administration of subordinating US sovereignty to Britain, but in the treaty’s wake US overseas trade boomed, feeding an economic revival.86

Military Strategy

Militarily, Hamilton and other Federalists argued for a small, peacetime professional army as a nucleus for wartime expansion, an example for the militia, and indispensable for preserving the republic. If America possessed effective government, remained united, and developed its strength, it could “choose peace or war as our interest guided by justice shall dictate.” Waiting until a war’s outbreak to raise troops was not the answer. Lacking military strength left one susceptible to attack and at the invader’s mercy. Neutrality meant having enough military strength to prevent another state from forcing your hand.87

In 1793, Algerian corsairs began seizing American merchant ships. The Naval Act of 1794 marked a reborn US navy but included a provision funding the ships only if the Algerian problem persisted. In 1795, word that peace had been made with Algiers, one that included the payment of tribute, was followed by Congress establishing a peacetime navy.88

Frontier Expansion, 1783–1801

The Peace of Paris gave the Americans vast tracts of land they didn’t control and over which they were too weak to exert sovereignty. The British refused to give up their border forts because the US hadn’t fulfilled its treaty obligation to ensure Britons recovered wartime claims against Americans. Britain used its Canadian border forts and those in the Northwest as bases for encouraging Indian resistance to American land hunger while helping create Indian coalitions. In the south, the border with Spain was unclear. Spain controlled the vast Louisiana territory, which it had received from France in 1762 for joining the Seven Years’ War. Spain disliked American encroachment west of the Appalachians and closed the Mississippi River to American navigation in 1784 to discourage this by preventing settlers from moving their goods down the river. Some Americans in the region connived with Madrid about leaving the Union, impulses Spain fed with bribes and trading licenses.89

The British didn’t consult their Indian allies when they made peace. Many Indian leaders had feared abandonment and were shocked by a betrayal in which London gave Indian lands to the American and Spanish victors. The 1783 treaty brought only a lull in hostilities. Many Indians and Whites were not ready for peace, and the traditional, vendetta-like frontier violence continued. The Americans imposed treaties on the region’s Indians at the end of the war that essentially drew an east–west line through the middle of Ohio, allocating the Indians its north. At the end of 1786, the United Indian Nations, a coalition of fourteen tribes, nullified any agreement not made with all its members. The next year saw Indians repudiating treaties some members had been forced to sign and raiding White settlements. They insisted the Ohio River was the boundary. The January 1789 Fort Harmar Treaty was supposed to resolve issues but did little more than pay the Indians for land the Americans had claimed by right of conquest and establish the same territorial division.90

There were perhaps 100,000 Indians between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. American leaders wanted orderly settlement of western lands, but Americans poured in. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 assured settlers retained their political and legal rights as Americans and could establish new states in these territories that were equal to the old. Until they were ready for statehood, a Federally named governor ruled. A population of 60,000 made it eligible for statehood.91

Americans generally saw Indian lands as fruit for plucking. A postwar land rush ensued, particularly in the Northwest, one fed by the poverty and indebtedness of the Confederation government (its best source of revenue was the sale of Indian lands), and land grants to veterans. US leaders realized the Indians weren’t ready to abandon these areas, but they considered them enemies who had aided the hated British. Taking their land was a way to extract compensation for wartime Indian destruction. Even Indian nations that had fought beside the Americans would be pushed off their lands. Many Americans believed their actions toward Indians could combine “expansion with honor” and thought having too much land caused Indian idleness and kept them from becoming “civilized.” Taking their territory did the Indians a favor by forcing them to change. A pattern soon underpinned US expansion against the Indians. New settlers or prospectors, often illegal, provoked Indian reprisals, sometimes because Indian leaders had no more success controlling their people than the US government. Americans then demanded Federal protection from the Indians, sometimes threatening to turn to Britain or Spain if they didn’t get it. Federal troops, and sometimes wars, then followed.92

The Washington administration temporarily defused problems along its southern frontiers via a treaty with the Creek Indians in 1790, one the Spanish supported as it meant their Indian trade continued. Resolving the situation in the Northwest proved more difficult. In 1789, Washington and Secretary of War Knox tried to gain control of the escalating crisis. Washington preferred to purchase Indian lands, and Knox dealt with the Indians as sovereign nations. Both wanted to prevent the Indians from being exterminated as they had in the east, and Knox hoped to convince them to become farmers like White Americans. This offends the modern conscience but was then the cutting-edge of enlightened thinking. Alternatives included dispossession and death. The continuing military threat led to placing Indian affairs in War Department hands. State legislatures and free-spirited settlers disagreed with the administration, and it lacked the power to do anything about it.93

The War against the Western Confederacy

In January 1790, in his first annual address to Congress, Washington called for defense of the frontiers against Indians. Washington preferred peace, but since this hadn’t happened, he urged Congress to better prepare militarily to protect the frontiers and “punish aggression” if needed. Congress increased the army to 1,283 men. As the undeclared frontier war intensified, the pressure upon the administration to act became unbearable. In June 1790, Knox ordered a “rapid and decisive” punitive campaign against the Miami Indians of the Ohio region. Its two prongs were supposed to utilize the effects of surprise to crush Indian forces and destroy their food supplies. The slow, bumbling campaign accomplished little more than burning a few villages and destroying the reputation of one of the commanders. The Indians replied by escalating their attacks. Knox ordered another campaign that culminated in September 1791 with approximately 1,000 Indians ambushing and decimating a US force of 1,400, killing over 600 of them.94

In the aftermath, US negotiators offered to make peace based on the Fort Harmar Treaty line, the de facto border when the war began. The Indians refused. The Americans now took seriously the prosecution of the war. Overconfidence, underestimation of the opponent, debacle, reassessment: this became a too often repeated pattern of American war-making. Washington named as commander “Mad” Anthony Wayne, an experienced Revolutionary War veteran. Wayne’s campaign was well planned and well led, and better prepared as the army was expanded and the troops properly trained. It didn’t begin until September 1793 as the administration wanted to first exhaust all efforts at negotiations. After these failed, Wayne broke the Indian forces at the Battle of Fallen Timbers on August 20, 1794. His victory allowed the Americans to attack an Indian critical vulnerability – food – by burning their cornfields. The signing of Jay’s Treaty compounded the Indians’ disasters as their British ally abandoned its forts in the region. The August 1795 Treaty of Greenville ended the war and established a boundary little changed. Wayne’s campaign ended British influence over the Indians of the Northwest until the War of 1812 and increased the credibility of the Federal government.95

As Wayne consolidated the nation’s northwestern periphery, American representative Thomas Pinckney negotiated a treaty with Spain in 1794 that fixed Florida’s boundary at the 31st parallel and granted America navigation rights on the Mississippi. It also robbed the southern Indian tribes of their Spanish support against American expansion. Congress reorganized and reduced the army in 1796, but a standing force survived.96

Washington’s Farewell Address

George Washington’s September 17, 1796 “Farewell Address” is famously known as a foundation for elements of American foreign relations. It can also be viewed as a grand strategy document (one heavily crafted by Hamilton), a shot at their pro-French Democratic-Republican political opponents, and an effort to dampen political division.97