Currently about 18 % of the population in Europe is at least 65 years old( 1 ). Albeit that health problems and care dependency occur more frequently with increasing age, most older people live in the community( 1 ) and manage their food supply by themselves.

Nutrition is a main contributor to health, well-being and quality of life in older age. Several studies have shown beneficial effects of the intake of certain nutrients as well as of certain dietary patterns, like the Mediterranean diet, on frailty, physical and cognitive function in older adults( Reference Talegawkar, Bandinelli and Bandeen-Roche 2 – Reference Feart, Samieri and Barberger-Gateau 6 ). Conversely, an unbalanced or an inadequate diet can result in undernutrition or obesity. Both are risk factors for adverse clinical outcomes including functional decline and mortality( Reference Van Nes, Herrmann and Gold 7 – Reference Donini, Savina and Gennaro 11 ). Depending on definitions and sampling aspects, prevalence rate up to 22 % has been reported for undernutrition in community-dwelling older adults living in Europe( Reference Meijers, Halfens and van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren 12 – Reference Torres, Dorigny and Kuhn 16 ). Obesity is prevalent in about 18 %( Reference Gallus, Lugo and Murisic 17 ). As the total number and proportion of older people will increase further( 1 ), preventive and therapeutic strategies reducing the prevalence of undernutrition and obesity become important public health issues.

In older people both unbalanced dietary patterns and inadequate intakes of energy and nutrients are frequently reported( Reference Millen, Silliman and Cantey-Kiser 18 – Reference Marshall, Stumbo and Warren 20 ). As dietary intake is influenced by an interplay of multiple individual, intra-individual, environmental and political factors( Reference Stok, Hoffmann and Volkert 21 ), it is necessary to identify relevant and modifiable factors to implement adequate preventive approaches. In older adults, on the individual level, functional factors are of interest as the ageing process is accompanied by numerous functional changes on different levels( Reference Clarke, Wahlqvist and Strauss 22 – Reference Carvalho and Lussi 26 ). Factors like declining chemosensory function, chewing and swallowing difficulties, physical limitations of the upper and lower extremities and cognitive impairments impede shopping, cooking and eating, may reduce the attractiveness of meals and may consequently influence dietary intake.

However, it is currently unclear which of these factors indeed affect dietary intake, if the associations are only correlational or causal, and if knowledge gaps exist.

The present systematic literature review aimed to compile the current knowledge on individual functional (chemosensory, oral, cognitive and physical) determinants of dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults. The work is part of the DEDIPAC (DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity) knowledge hub (Thematic Area 2), focusing on determinants of diet across the life course( Reference Lakerveld, van der Ploeg and Kroeze 27 ).

Methods

The procedure of the current systematic literature review was documented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 28 ).

Literature search

In February 2015 a systematic search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library to identify relevant studies on functional determinants of dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults. In August 2017 the search was updated. Additionally, reference lists of the included studies and of one systematic literature review on mastication and dietary intake in older adults( Reference Tada and Miura 29 ) were screened for relevant papers. To define the search terms of the different fields we focused on theoretical models and frameworks, studies dealing with the respective topics, keywords and MeSH (medical subject heading) terms from the searched databases, and expertise of the working group members. The search strategy was documented in a study protocol and combines terms of the following fields: outcome (e.g. ‘dietary intake’), sample (e.g. ‘older adults’ and ‘community-dwelling’), description of the kind of association (e.g. ‘determinant’, ‘correlate’) and determinant (‘chemosensory’, ‘oral’, ‘cognitive’, or ‘physical’ function). The detailed search strategy can be found in the online supplementary material, Supplemental File 1.

Study selection

The study selection was based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Regarding the study population, only studies with participants at least 65 years of age, not being acutely ill and living in the community were included. Studies which focused solely on specific diseases or which were conducted in the hospital or the nursing home setting were excluded. These criteria were chosen to collect data representative and specific for the old age group. Therefore, studies with a mean sample age of 65 years or older but including younger individuals were not considered, as in the younger part of the sample different aspects (e.g. working conditions) determine behaviour than can be expected for the retired older population.

There were no restrictions regarding the study design and the publication year. Only publications in English language were considered and grey literature in book chapters, reports and conference abstracts were excluded.

After excluding duplicates, the study selection was performed in a three-step procedure. Titles, abstracts and full texts were screened by two independent reviewers. In cases of disagreement regarding the inclusion, a third reviewer was consulted. The titles, abstracts and full texts were distributed among the working group members according to their expertise: C.S.-R., L.M.D., E.P. and S.M. were responsible for oral and chemosensory determinants; C.F., L.M.D., E.P. and S.M. worked on cognitive determinants; and A.Sa., D.C., F.S., E.M., A.P. and E.K. conducted the screening for physical determinants. E.K. and D.V. acted as third reviewers to solve disagreements.

Data extraction

For the included papers, besides general article information (authors, title, year, citation), data regarding the studies’ characteristics (objective, study design, sample size, inclusion and exclusion criteria) and participants’ characteristics (mean age or age range, percentage female gender, country/ethnicity, health/functional status) were extracted. Moreover, information on the determinants and outcomes (name and assessment method) used in the respective studies and the main results were summarized. To describe the associations between functional determinants and dietary outcomes, correlation coefficients, β coefficients, OR with CI and P values were extracted. Data extraction was conducted in duplicate. E.K. summarized the data extraction tables, and the results were confirmed by the systematic literature review group.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of the reviewed studies was guided by the tool of Kmet et al.( Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook 30 ). The description and appropriateness of eleven criteria on research question, study design, subject selection, subject characteristics, outcome measures, sample size, analytical approach, estimate of variance, confounder control, study results and conclusions were evaluated. Each criterion was rated with ‘yes’, ‘partial’ or ‘no’. The summary score was calculated as follows: [(number of ‘yes’×2) + (number of ‘partial’×1)]/(total possible sum − number of ‘not applicable’×2). Higher scores indicate a better quality, with a score of 1 representing fulfilling all quality criteria. The quality assessment was conducted by two independent reviewers for each study. In cases of disagreement, the issues were solved by the mediation of E.K. as a third reviewer.

Results

Study selection

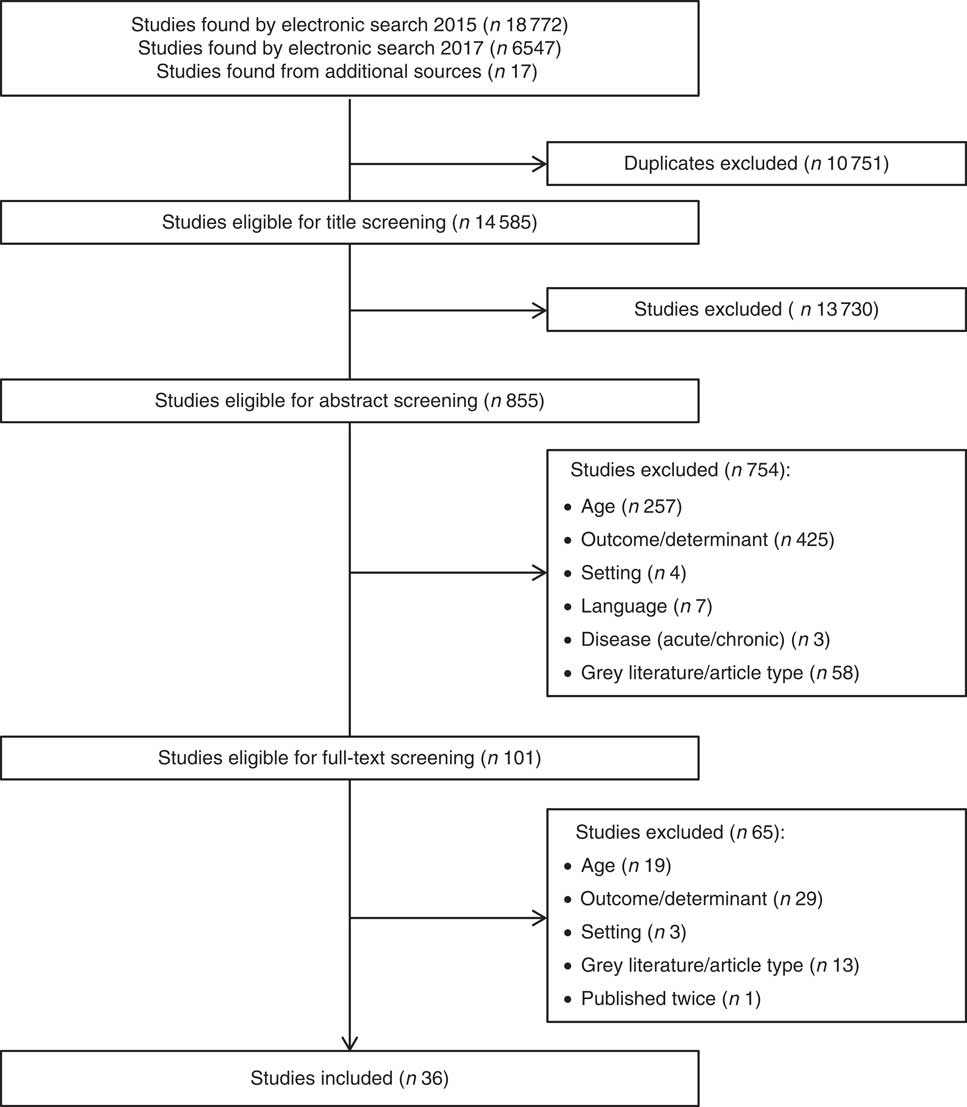

Figure 1 provides an overview of the screening and selection process. The systematic search resulted in 25 319 hits and seventeen studies were found by additional sources. After removing duplicates, 14 585 studies were eligible for the title screening. During the title screening 13 730 studies were excluded for not matching the inclusion criteria; thus 855 potentially relevant studies were included in the abstract screening. During the abstract screening a further 754 studies were excluded. Accordingly, full-text screening was performed with 101 studies. As a further sixty-four articles had to be excluded and two publications on oral determinants( Reference Sheiham and Steele 31 , Reference Sheiham, Steele and Marcenes 32 ) reporting the same results were counted as one study, the selection process resulted in thirty-six publications.

Fig. 1 Flowchart describing the process of study selection for the present systematic literature review on functional determinants of dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults

Studies’ and participants’ characteristics

Table 1 presents an overview of the main studies’ and participants’ characteristics. Of the thirty-six considered studies, nine were published before 2000 and thirteen studies were published after 2010. Thirty studies were cross-sectional and six had a longitudinal design. Most studies were conducted in Asia (n 13) followed by North America (n 11) and Europe (n 10). Only one study was conducted in Africa (n 1) and one study combined data from Europe and the USA (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of the studies and participants included in the present systematic literature review on functional determinants of dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults

CS, cross-sectional study; LS, longitudinal study; NR, not reported; ADL, activities of daily living; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

* CS or LS.

† Mean and sd, or percentage, or inclusion age.

‡ Sum score of the quality assessment according to Kmet et al. ( Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook 30 ).

Sample sizes range from fifty-seven to 5073 participants with twelve studies including at least 1000 participants and five studies with fewer than 100 participants (Table 1). The studies varied regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria, some using only few and rough criteria like age, while others used very specific criteria like the absence of cognitive or physical functional limitations or specific diseases (see online supplementary material, Supplemental File 2).

Most of the studies included both genders, two studies focused solely on women, two solely on men and three further studies did not report on gender (Table 1). The mean age was not presented in all studies. Only three studies reported a mean age of at least 80 years, while in most studies the mean age was between 70 and 79 years (Table 1).

In twenty-three studies health and functional status of the participants was not characterized. Participants of the other studies were mostly free of major functional limitations or health complaints (Table 1).

Outcome

Regarding the outcomes, sixteen studies focused on energy and/or nutrient intakes (macronutrients, micronutrients, fibre), five studies on food intakes, and eight studies on the combination of food and nutrient intakes. Further, seven studies used scores to describe dietary quality or diversity (Table 2). Methods to assess the outcome comprised 24h recalls (n 10), FFQ (n 4), simple food lists (n 4), estimated dietary records (n 1), diet history questionnaires (n 10), weighing protocols (n 3), or combinations of methods (n 4; Table 2).

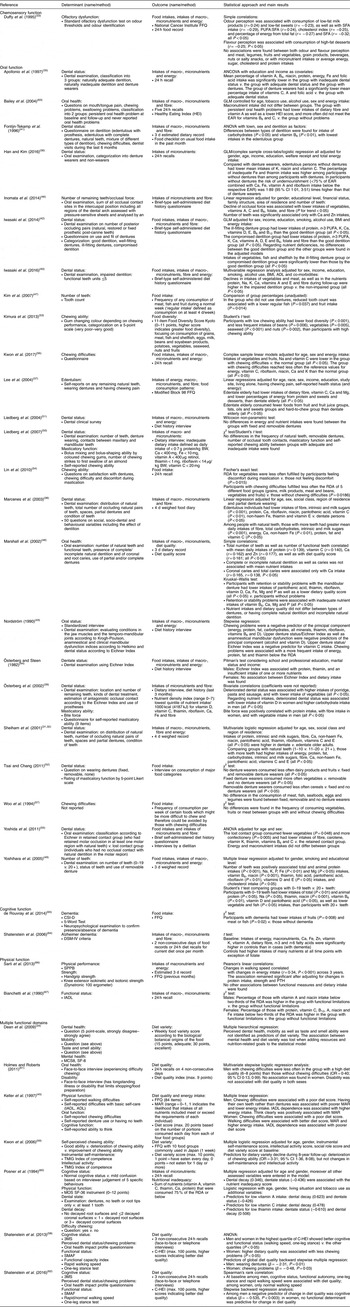

Table 2 Definition of determinants and outcomes and main results of the studies included in the present systematic literature review on functional determinants of dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults

CSI-D, Community Screening Interview for Dementia; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MCS8, Mental Component Score; SF-8, Short-Form 8-Item Health Survey; ADL, activities of daily living; TMIG, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology Index; MOS SF-36, Medical Outcome Study Short Form Health Survey; 3MS, Modified Mini-Mental State examination; SMAF, Système de mesure de l’autonomie functionnelle; BW, body weight; MAR, mean adequacy ratio; C-HEI, Canadian Healthy Eating Index; GLM, general linear model; EAR, Estimated Average Requirement; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Quality of the studies

The quality scores ranged from 0·14 to 1·00, with four studies fulfilling all criteria sufficiently. Fifteen studies had a score>0·90 indicating a low risk of bias. Eleven studies reached a score between 0·75 and 0·90 and a further five studies between 0·64 and<0·75. Only one study met less than half of the considered quality criteria. The mean quality scores of the studies were similar between the different determinant domains: chemosensory function (0·89), oral function (0·86), cognitive function (0·89) and physical function (0·90). Methodological shortcomings were mostly identified regarding confounder control (n 21), description of subjects’ characteristics (n 21) and definition of outcomes (n 11). The quality criteria on study objective (n 3), study design (n 2) and conclusion (n 0) were most often fulfilled. The sum score of the quality assessment is shown in Table 1 and details are presented in the online supplementary material, Supplemental File 3.

Chemosensory function

Regarding chemosensory function two cross-sectional studies were identified( Reference Duffy, Backstrand and Ferris 33 , Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 ). The first study evaluated olfactory function by objective tests on odour thresholds and odour identification and investigated the association with food and nutrient intakes( Reference Duffy, Backstrand and Ferris 33 ) (Table 2). Only bivariate correlations were presented. Regarding food intakes, most correlations between both odour and flavour perception and the respective food groups were not significant. Regarding nutrient intakes, some low but significant correlations between odour perception and measures of fat intake were found (all correlation coefficients<0·35; Table 2). The second study did not identify self-reported ability to taste and smell as a predictor of diet variety (Table 2)( Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 ).

Oral function

Thirty-one studies were identified examining oral factors in relation to dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults( Reference Sheiham and Steele 31 , Reference Sheiham, Steele and Marcenes 32 , Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 – Reference Bailey, Harris Ledikwe and Smiciklas-Wright 63 ). Regarding the outcome, most of the studies focused on the intakes of micro- and macronutrients (n 21) and dietary fibre (n 10). Further outcome measures were the intake of certain foods (n 11), food diversity (n 3) and dietary quality (n 4; Table 2).

As oral factors general aspects of oral health like number of teeth, dental status (inadequate v. adequate), caries or wearing dentures were investigated (n 22). Additionally, some studies focused on functional aspects by assessing chewing ability and bite force (n 17). Only one study considered also the aspect of swallowing function as a component of an oral health indicator( Reference Bailey, Harris Ledikwe and Smiciklas-Wright 63 ) (Table 2).

Thirteen studies used dental examinations or objective tests to evaluate oral factors, thirteen studies were questionnaire-based, and five studies used combinations of dental examinations and self-reports (Table 2).

Regarding dental status, thirteen out of seventeen studies reported that edentulous subjects and those with inadequate dental status had lower intakes of certain foods and nutrients compared with those with adequate dental status or dentures( Reference Sheiham and Steele 31 , Reference Sheiham, Steele and Marcenes 32 , Reference Appollonio, Carabellese and Frattola 35 – Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 , Reference Posner, Jette and Smigelski 60 ). Moreover, tooth count was associated with dietary intake in five of six studies( Reference Sheiham and Steele 31 , Reference Sheiham, Steele and Marcenes 32 , Reference Marcenes, Steele and Sheiham 38 , Reference Inomata, Ikebe and Kagawa 46 – Reference Yoshihara, Watanabe and Nishimuta 49 ). Five studies investigated differences in the intakes of foods and nutrients between groups wearing different types of dentures (e.g. fixed dentures or removable dentures)( Reference Fontijn-Tekamp, van ’t Hof and Slagter 41 , Reference Marshall, Warren and Hand 48 , Reference Liedberg, Stoltze and Norlen 50 – Reference Tsai and Chang 52 ). Only Tsai and Chang reported differences between fixed, removable and no denture wearers in some of the investigated food groups( Reference Tsai and Chang 52 ). However, no clear trend favouring a certain denture type was visible (Table 2).

Of the fourteen studies focusing on chewing ability or chewing problems( Reference Fontijn-Tekamp, van ’t Hof and Slagter 41 , Reference Nordström 43 , Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 , Reference Liedberg, Stoltze and Norlen 50 , Reference Tsai and Chang 52 – Reference Lin, Chen and Lee 54 , Reference Kwon, Park and Lee 56 – Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ), four showed no association with food/nutrient intakes or diet quality( Reference Liedberg, Stoltze and Norlen 50 , Reference Woo, Ho and Lau 57 , Reference Posner, Jette and Smigelski 60 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ) and two did not report the results( Reference Fontijn-Tekamp, van ’t Hof and Slagter 41 , Reference Tsai and Chang 52 ). All other studies observed lower intakes of at least certain foods or nutrients as well as lower dietary quality in those with chewing problems compared with those without chewing problems (Table 2). In an 8-year follow-up study, deterioration of chewing ability was identified as an important predictor of a decline in dietary variety (OR=3·31; 95 % CI 1·36, 8·08)( Reference Kwon, Suzuki and Kumagai 59 ), while a 3-year follow-up study did not identify chewing ability as a predictor of change in diet quality( Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ).

In both studies investigating bite force, this factor was consistently related to fibre and vegetable intakes( Reference Österberg, Tsuga and Rothenberg 39 , Reference Inomata, Ikebe and Kagawa 46 ). The study summarizing multiple oral health problems, including swallowing function, showed a negative modification of micronutrient and fibre intakes but not of macronutrient intakes (Table 2)( Reference Bailey, Harris Ledikwe and Smiciklas-Wright 63 ).

Cognitive function

Eight studies (five cross-sectional and three longitudinal) investigating cognitive function as a determinant of dietary intake were found( Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 , Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 58 – Reference Posner, Jette and Smigelski 60 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 , Reference Shatenstein, Kergoat and Reid 64 , Reference de Rouvray, Jesus and Guerchet 65 ) (Tables 1 and 2). The two studies focusing on dementia diagnosed by DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.) criteria and by a neuropsychological test battery showed lower intakes of certain foods in demented compared with non-demented participants( Reference Shatenstein, Kergoat and Reid 64 , Reference de Rouvray, Jesus and Guerchet 65 ). The study by Shatenstein et al. used a longitudinal case–control design( Reference Shatenstein, Kergoat and Reid 64 ) while the study of de Rouvray et al. was cross-sectional and presented only unadjusted results( Reference de Rouvray, Jesus and Guerchet 65 ). In another study based on a subjective judgement of cognitive status by the interviewer, no association between cognitive function and a nutrient inadequacy score was found( Reference Posner, Jette and Smigelski 60 ). However, in that study, only a small part of the sample (5 %) was identified to be cognitively disordered (Table 1).

The other included studies focused on diet variety and quality as outcomes. Mental health and intellectual activity, respectively, were identified as neither a predictor of diet variety in a cross-sectional study( Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 ) nor a predictor of a decline in diet variety across 8 years of follow-up( Reference Kwon, Suzuki and Kumagai 59 ). Two studies that were based on the same data set showed no cross-sectional association in the multiple regression between cognitive status assessed by the 3MS (Modified Mini-Mental State) examination and diet quality( Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 58 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ). However, analysis of the longitudinal data identified cognitive status as negative predictor for change in diet quality in men but not in women( Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ). The gender difference was confirmed by the cross-sectional study of Keller et al. that reported an association between self-reported cognitive function and mean adequacy ratio, as an indicator of diet quality, only in men( Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 ).

Physical function

Nine studies examined the association between physical function and dietary intake (Tables 1 and 2)( Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 , Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 58 – Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 , Reference Sarti, Ruggiero and Coin 66 , Reference Bianchetti, Rozzini and Carabellese 67 ). Three studies used objective measures comprising handgrip strength, Short Physical Performance Battery, gait speed or standing balance to describe physical function( Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 58 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 , Reference Sarti, Ruggiero and Coin 66 ). One of these, a small longitudinal study in older women, focused on energy and macronutrient intakes as outcomes and found an association between the change in walking speed and the change in energy intake across 3 years of follow-up( Reference Sarti, Ruggiero and Coin 66 ). No other functional measure was identified as a determinant of energy or macronutrient intake. In two other studies higher walking speed and better standing balance were not identified as predictors of diet quality at baseline (multiple regression) and of change in diet quality during 3 years of follow-up( Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 58 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ). Of the six studies using questionnaire-based measures to evaluate functional status, four showed no association between physical functional factors and the outcomes diet quality, diet variety and nutrient intakes( Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 , Reference Kwon, Suzuki and Kumagai 59 – Reference Holmes and Roberts 61 ). In a cross-sectional study comparing subjects with and without functional limitations, differences in reaching the RDA for different nutrients were observed( Reference Bianchetti, Rozzini and Carabellese 67 ). Keller et al. reported higher energy intake in men with IADL (instrumental activities of daily living) dependency and poorer diet quality in women with IADL dependency compared with the reference groups( Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 ).

Discussion

The present systematic literature review compiled the knowledge on functional determinants of dietary intake in community-dwelling adults aged 65 years or older.

One important finding is that research on determinants is scarce. By definition a factor is a determinant of a specific behaviour if a variation in this factor is systematically followed by variation in the behaviour( Reference Bauman, Sallis and Dzewaltowski 68 ). As no intervention studies were identified and most studies dealing with this topic had a cross-sectional design, it is only possible to speak about correlates, predictors or factors of dietary intake. Moreover, in some studies investigation of the relationship between functional factors and dietary intake was only a secondary aim( Reference Kim, Stewart and Prince 47 , Reference Tsai and Chang 52 , Reference de Rouvray, Jesus and Guerchet 65 ). Consequently, the results were just presented in a descriptive manner based on bivariate correlational approaches or simple comparisons of means, which negatively affected the quality assessment. Multifactorial analyses of various independent variables and sufficiently adjusted statistical models were often missing. Altogether, it is not possible to make any statement on the extent to which the single factors affect dietary intake.

The number of publications investigating the different functional domains of chemosensory, oral, cognitive and physical function varied. While oral factors were extensively studied, evidence in other fields is poor and the findings were partly inconsistent.

Dietary intake

In the current review the outcome ‘dietary intake’ covers a broad range of different aspects: intakes of certain food groups, macronutrients, micronutrients and fibre, diet quality and diet variety. Regarding the definition of the outcome as well as its assessment, heterogeneity between studies was found. Those studies looking at food and nutrient intakes mostly did not focus on specific food groups or nutrients but reported associations between the determinants and a broad range of dietary aspects, leading to the problem of significance by multiple testing. The studies varied with respect to the tools used to assess current intake (e.g. 24 h recalls, estimated dietary records, weighing protocols), habitual intake (e.g. FFQ, diet history) and the respective reference periods (e.g. few days, one week, three months, one year). Eleven studies showed shortcomings within the quality assessment regarding the outcome measures used. A validation of the tools was not always given, especially for the used food lists. Moreover, some studies used just one 24 h recall, which is presumably insufficient to display dietary intake properly and to consider differences between weekdays and weekend days. As studies from four different continents were considered, the different eating cultures may also partly explain differences in results.

Oral function

A high number of studies reported oral function as a correlate of dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults. Different surrogates of oral function (i.e. dental status, number of teeth, bite force and chewing problems) were associated with food as well as nutrient or fibre intake( Reference Sheiham and Steele 31 , Reference Sheiham, Steele and Marcenes 32 , Reference Appollonio, Carabellese and Frattola 35 – Reference Iwasaki, Yoshihara and Ogawa 40 , Reference Iwasaki, Taylor and Manz 42 – Reference Yoshihara, Watanabe and Nishimuta 49 , Reference Tsai and Chang 52 – Reference Kwon, Park and Lee 56 , Reference Kwon, Suzuki and Kumagai 59 , Reference Posner, Jette and Smigelski 60 , Reference Bailey, Harris Ledikwe and Smiciklas-Wright 63 ). Against expectations, a relationship between oral impairment and a reduced intake of meat was only infrequently described( Reference Lee, Weyant and Corby 37 , Reference Iwasaki, Yoshihara and Ogawa 40 , Reference Lin, Chen and Lee 54 ). Moreover, it should be noticed that the detected differences between groups with and without problems in oral function are not necessarily clinically meaningful, as a lower intake is not equal to insufficient intake. Nine of the included studies specifically addressed this issue( Reference Appollonio, Carabellese and Frattola 35 , Reference Iwasaki, Taylor and Manz 42 – Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 , Reference Marshall, Warren and Hand 48 , Reference Liedberg, Stoltze and Norlen 50 , Reference Posner, Jette and Smigelski 60 , Reference Bailey, Harris Ledikwe and Smiciklas-Wright 63 ), with seven studies reporting more often an intake of certain nutrients not meeting the respective recommendations in the groups with oral problems compared with the groups without oral problems( Reference Appollonio, Carabellese and Frattola 35 , Reference Nordström 43 – Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 , Reference Marshall, Warren and Hand 48 , Reference Posner, Jette and Smigelski 60 , Reference Bailey, Harris Ledikwe and Smiciklas-Wright 63 ). The nutrients for which the intake was inadequate differed between studies. Most often vitamin C and Ca intakes were identified. The insufficient vitamin C intake could be linked to a lower consumption of fruits and vegetables which was often reported in participants with oral problems( Reference Lee, Weyant and Corby 37 , Reference Iwasaki, Taylor and Manz 42 , Reference Lin, Chen and Lee 54 , Reference Yoshida, Kikutani and Yoshikawa 55 ). The association between oral problems and low protein intake( Reference Sheiham and Steele 31 , Reference Sheiham, Steele and Marcenes 32 , Reference Appollonio, Carabellese and Frattola 35 , Reference Marcenes, Steele and Sheiham 38 , Reference Österberg, Tsuga and Rothenberg 39 , Reference Nordström 43 , Reference Marshall, Warren and Hand 48 , Reference Yoshihara, Watanabe and Nishimuta 49 ) needs to be discussed independently of the respective reference values, as current recommendations on daily protein intake are considered too low for older adults to preserve the age-related loss of muscle mass( Reference Bauer, Biolo and Cederholm 69 ). As chewing ability is related to sarcopenia( Reference Murakami, Hirano and Watanabe 70 ), protein intake in older adults with oral problems should receive special attention.

Our results are in line with those of another systematic review focusing specifically on the association between mastication and food and nutrient intakes in older people( Reference Tada and Miura 29 ). The systematic review differs from our work regarding search terms and younger inclusion age (≥50 years). Tada and Miura also considered some intervention studies, not matching our inclusion criteria, which could not show an effect of a prosthetic treatment on food intake( Reference Tada and Miura 29 ), indicating that, under these conditions, oral function is only a small contributor to the complex dietary behaviour of older people.

In the studies included in our review, a huge variety of different oral factors was examined. Unfortunately results were often presented for single factors only and without adjustment, while multifactorial approaches entering several oral factors simultaneously or stepwise in the respective statistical models were scarce( Reference Lee, Weyant and Corby 37 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 58 – Reference Posner, Jette and Smigelski 60 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ). Consequently, it is difficult to conclude on the extent to which the single factors influence dietary intake and how they are interrelated. Moreover, due to the different assessment methods, comparability is limited.

When speaking about existing evidence that oral function is a factor of dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults, we have to exclude swallowing function as our search identified only one study investigating swallowing function( Reference Bailey, Harris Ledikwe and Smiciklas-Wright 63 ) and that study did not present the results on swallowing function separately but solely differentiated between persistent oral health problems and no oral health problems( Reference Bailey, Harris Ledikwe and Smiciklas-Wright 63 ). About 15 % of community-dwelling older adults are affected by dysphagia( Reference Madhavan, LaGorio and Crary 71 ). Depending on the severity, persons concerned are forced to eat soft and texture-modified foods, which increases the risk of inadequate intakes of energy and nutrients( Reference Wirth, Dziewas and Beck 24 ). Further research is needed in this field.

Chemosensory function

As only two studies were identified examining the relationship between chemosensory function and dietary intake( Reference Duffy, Backstrand and Ferris 33 , Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 ), using different methodological approaches and showing controversial results, no statement on the role of chemosensory function on older people’s dietary intake can be derived. Chemosensory impairment is described as a common problem in the older population that often remains unrecognized by the older people due to gradual changes in chemosensory function( Reference Attems, Walker and Jellinger 23 , Reference Arganini and Sinesio 72 – Reference Pinto, Wroblewski and Kern 74 ). Moreover, chemosensory function is discussed as a factor in the complex pathophysiology of anorexia of ageing( Reference Morley 75 – Reference Donini, Savina and Cannella 77 ). Consequently, the impact of chemosensory function on food choices and dietary intake needs further clarification. This should also include the testing of interactions between taste and smell perceptions, and the examination of potential compensatory mechanisms to overcome chemosensory dysfunction. In one study mentioned above, eating foods with a creamy mouth feeling was described as such a strategy( Reference Duffy, Backstrand and Ferris 33 ).

Cognitive function

The eight studies investigating cognitive function in relation to dietary intake showed inconsistent results. Those considering dementia as a disease reported lower intakes in those who were affected( Reference Shatenstein, Kergoat and Reid 64 , Reference de Rouvray, Jesus and Guerchet 65 ). Studies referring to cognitive impairment revealed no association with diet variety( Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 , Reference Kwon, Suzuki and Kumagai 59 ) or that diet quality was reduced only in men with cognitive impairment but not in women( Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ). Generally, evidence regarding this topic is low and no clear statement can be derived that cognitive function is a determinant of dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults. As dementia and cognitive impairment are well known as risk factors for malnutrition in the older population( Reference Meijers, Schols and Halfens 78 , Reference Moreira and Krausch-Hofmann 79 ), the assumption that these factors are also linked to dietary intake is obvious. Dietary intake can be seen as a mediator in the origin of malnutrition. However, a considerable number of studies were excluded from the current review as they looked at the topic the other way around, examining the preventive potential of certain nutrients or specific dietary patterns like the Mediterranean diet on cognitive function( Reference Tangney, Li and Wang 5 , Reference Feart, Samieri and Barberger-Gateau 6 , Reference Petersson and Philippou 80 – Reference Agnew-Blais, Wassertheil-Smoller and Kang 82 ).

Physical function

The studies investigating physical function as a factor of dietary intake mostly showed no or only slight associations. However, the limited evidence does not allow any conclusions. From the theoretical point of view physical limitations may lead to an unbalanced diet via impeding shopping, cooking, opening packages, cutting foods and eating. A sound foundation of this hypothesis by research is missing. As in most studies participants were in good general health, functional limitations might be not pronounced enough to affect the aforementioned tasks. Moreover, it would be useful to assess in addition to functional limitations also social support, as this aspect is important to cope with the problem. Regarding the methods to assess physical function, the questionnaires used might often be inappropriate to detect participants with beginning functional decline or to discriminate between groups with and without physical limitations. Concerning community-dwelling older people, questionnaire-based instruments focusing on instrumental activities like cooking and shopping, as addressed in the studies of Bianchetti et al. ( Reference Bianchetti, Rozzini and Carabellese 67 ) and Keller et al. ( Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 ), might be more suitable than questionnaires on basic activities of daily living. Even though the studies by Shatenstein et al. ( Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 58 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ) failed to identify physical functional factors as determinants of diet quality, such approaches considering both objective and subjective functional measures might be useful to cover diverse functional domains with different levels of complexity.

Multiple functional domains

Besides several functional factors, some of the studies also considered psychosocial determinants( Reference Dean, Raats and Grunert 34 , Reference Keller, Ostbye and Bright-See 45 , Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 58 – Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller 62 ). Although these studies are difficult to compare concerning the independent factors and the outcome variables, they have the advantage that the influence of multiple factors is displayed, reflecting the complexity of dietary behaviour and the interplay of individual factors of different determinant domains. Very recently within the DEDIPAC project an interdisciplinary framework of determinants on nutrition and eating across the lifespan was developed, displaying (besides multiple determinant levels) also modifiability and the research priority of each determinant( Reference Stok, Hoffmann and Volkert 21 ). This framework can guide future research on determinants of dietary behaviour.

Limitations

A selection bias cannot be excluded. First, it is possible that not all studies dealing with the topic are indexed in the searched databases. Second, the search was based on a list of terms describing the potential determinants of the different domains. We tried to be as complete as possible; however, it cannot be excluded that by adding some other terms additional relevant papers would have been identified. Third, restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria were used. As our work should focus on older adults, we only included studies based on our inclusion criterion of age ≥65 years. Considering also studies with a mean age of ≥65 years but a lower inclusion age for participants would have extended the results. On the other hand, this approach could obscure the intended characterization of determinants of dietary intake in the old age group, as people aged between 50 and 65 years are normally still working, which could confound the dietary behaviour. Moreover, most of the excluded studies using age cut-off between 50 and 60 years did not meet at least one inclusion criterion irrespective of the age aspect. Although we focused only on studies in English, the language bias is presumably low as only seven studies were excluded due to the language criterion and is likely that they did not meet other inclusion criteria. The same is true for the exclusion of conference abstracts. A last point which should be addressed as a limitation is publication bias, as studies with negative results are less often published.

Conclusion

The current systematic literature review presented a considerable number of studies reporting associations of the oral factors dental status and chewing ability with dietary intake in community-dwelling older adults. However, as most of the studies had a cross-sectional design and many presented non-adjusted data, no causal relationship could be derived. With regard to the other determinants, chemosensory, cognitive and physical function, data were either inconsistent or insufficient to conclude on any meaningful relationship. Future prospective studies specifically designed to measure determinants of dietary behaviour are needed. Attempts to align research by using the same standardized and validated tools should be further fostered to increase comparability of study results and to simplify the transmission of study results into effective public health strategies.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The preparation of this paper was supported by the DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity (DEDIPAC) knowledge hub. This work is supported by the Joint Programming Initiative ‘Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life’. Financial support: The funding agencies supporting this work are as follows (in alphabetical order of participating Member State). France: Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA). Germany: Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant number 01EA1382). Italy: Ministry of Education, University and Research; Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies (grant number DEDIPAC-IRILD, D.M. 14474/7303/13, n.7953). The Netherlands: The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; grant number 200600003). Poland: The National Centre for Research and Development (grant number DZP/2/JPI HDHL DEDIPAC KH/2014). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: E.K., E.P., S.M., L.M.D., C.S.-R., A.Su., K.W.-T., W.P., D.Ł., A.Sa., F.S., A.P., E.M., D.C. and J.B. report that they have no potential conflict of interest. C.F. reports receiving fees for conferences from Danone Research and Nutricia. D.V. reports grants from Karl-Düsterberg Stiftung, outside the submitted work; and is a member of the scientific advisory board of Apetito. Authorship: E.K. planned the review, conducted the search, study selection, data extraction and evaluation, and drafted the paper. E.P., S.M., L.M.D., C.S.-R., C.F., A.Sa., D.C., F.S., E.M., A.P., A.Su., K.W.-T., W.P. and D.Ł. contributed to the planning of the review, conducted the study selection, data extraction and evaluation, and revised the paper. J.B. contributed to the planning of the review and evaluation of the data and revised the paper. D.V. planned the review, contributed to the study selection, conducted the data evaluation and revised the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017004244