Introduction

The ability to translate unseen passages is a skill tested in both Latin A-level and the International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma. Higher IB candidates are expected to translate a passage of 105–125 words of Latin poetry (in this case, Ovid's Metamorphoses) as the first of their externally marked papers. The International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO) uses unseen passages to ‘measure the [students’] ability to understand and translate texts in the original language’ (2014, p. 25). The passages are marked according to two criteria: (a) meaning; (b) vocabulary and grammar. In order to access the highest grades, the students must provide a ‘logical translation [in which] errors do not impair the meaning’ and ‘render vocabulary appropriately and grammar accurately and effectively’ (IBO, 2014, pp. 28–9).

At the start of my second school placement, there was a concern amongst the Classics department over the attitude of the Year 12 Higher Latinists towards this unseen translation paper. This apathy is not uncommon among school students and university undergraduates alike. Indeed, a study into redesigning unseen translations, led by the University of Cambridge, described them as a: ‘joyless, blinkered, puzzle-solving exercise’ (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Irwin, Lovatt, Low, Rogerson and Weeks2003, p.9). The study also revealed an ‘overwhelming honesty with which the difficulties in attaining linguistic competence are admitted’ (Reference Greenwood, Irwin, Lovatt, Low, Rogerson and Weeks2003, p.33). In order for the students to access the best grades, it seems important to improve this mindset and increase confidence. It is true that too often students are ‘the passive recipients of knowledge rather than being active in its creation’ (Gillies & Boyle, Reference Gillies and Boyle2010, p.933). I hoped that, through encouraging students to work co-operatively, they would be able to take ownership of their knowledge, share ideas and utilise each other's strengths. Co-operative Learning (hencefore referred to as CL) is a pedagogical practice where ‘students work together in small groups to help one another study

academic matter’ (Tan, Sharan & Lee, Reference Tan, Sharan and Lee2006, p.4). A great deal of research has already been carried out on the academic and social advantages of CL (Johnson & Johnson, Reference Johnson and Johnson1999; Slavin, Reference Slavin1996). Indeed, Gillies, Ashman and Terwel state that ‘[CL] is well recognised as a pedagogical practice that promotes learning … from pre-school to college’ (Reference Gillies, Ashman, Terwel, Gillies, Ashman and Terwel2008, p.1).

However, from my own personal experience, teachers of sixth form classes (especially) rarely use this technique. The majority of research into CL, according to Johnson and Johnson, evaluates group work in primary education and early secondary education (50.5%) or at university level (41.4%) (Reference Johnson, Johnson, Gillies, Ashman and Terwel2008, p.14). Given its success with these age groups, I wished to carry own my own small-scale study to see if such practice could be utilised effectively with sixth formers. The study aimed to provide students with techniques, acquired during a process of CL, to improve their accuracy in translating unseens, and, by means of a higher level of engagement with the text, increase their confidence.

In order to facilitate this study, I shall firstly carry out a literature review, examining studies of both unseen translation and CL, which will consequently inform my research questions. I shall then detail my plan for a sequence of nine lessons and justify my methods for data collection. Finally, I shall present my findings and propose a tentative conclusion as to the extent CL promotes a greater confidence and a more accurate rendering of syntax in unseen translations.

Context

The school in which I carried out my study is situated in North Kent. It is a selective state grammar school and a World IB school for boys aged 11–18 (girls are admitted aged 17–18). The proportion of students who have English as an Additional Language (EAL) greatly exceeds the national average, yet the proportion of students with Special Education Needs (SEN) is well below the national average.

Latin is chosen as an optional language in Year 8, in competition with French, Spanish and German. This choice is then taken for GCSE alongside either Japanese or Mandarin. The study of a language at IB Higher or Standard level is compulsory. Latin is a very popular subject at the school.

The class I have chosen as the subject of this study is the Year 12 Higher Latinists, consisting of eight boys. On the IB grading system of Levels 1–7 (with 7 being the highest grade), five of the boys are predicted a Level 6; the other three are

predicteda Level 5. All boys achieved an A* (the highest grade) in their Latin GCSE, and are described by their current teacher as ‘extremely bright and academically able’, yet their flaws as a class were highlighted: ‘they have a tendency to be thoughtless in their translation, however, sacrificing accuracy and sense for speed’ (Teacher T, interview, 2016). The eight boys have very different characters and strengths, and have divided themselves into three distinct subgroups in the classroom. One student has ASD, none are EAL or Pupil Premium. Three are part of the school's Gifted and Talented scheme. Aged 16 and 17, and with a clear desire to study Latin, this group, in my opinion, would be the most suitable for my study as they were all mature enough to participate in the study responsibly and provide honest answers to questionnaires. The small size of the class and the frequency of their lessons were also favourable for the scope of the study.

All of the lessons take place in the same classroom, a small room with 8 desks in a C shape, facing the whiteboards. The boys sit in one long row at the back of the room. Whilst suitable for teacher-led session using the whiteboard, I deduced that this set up was not particularly conducive to group work.

Initial observations

I observed four of the boys’ 50-minute language lessons over a fortnight. The boys were working through the translation practice exercises from Matthew Owen's Ovid Unseens (Reference Owen2014), completing one hexameter passage over the twice-weekly grammar lesson cycle. Both cycles followed a similar format, whereby the passage was introduced by the teacher; there was a short discussion about the myth (with which usually at least one of the boys was familiar); the teacher guided the boys through the first two lines of the passage; and then they worked independently for the rest of the lesson. At the end of the second lesson of the week, the teacher would read aloud a translation of the passage with little or no input from the boys. Although the teacher circulated during the lesson and looked at their work over their shoulders, it appeared to me that the boys were not fully engaged with their translation: when prompted by the teacher, the boys sometimes struggled to defend their vocabulary choices or rendering of grammar. When the teacher did ask questions of the boys more generally, the same two boys dominated the discussion. Having also observed the same class, albeit with another teacher, in their Literature lessons, their lack of confidence towards the Ovid unseens contrasted sharply with their enthusiasm for literary criticism on Virgil's Aeneid. In my view, there were two main problems: firstly, the students rarely communicated with each other, or indeed the teacher, and there was no sharing of ideas or modelling good answers or techniques, and, secondly, the students’ grasp of English grammar and parts of speech hindered their ability to break down and translate accurately Latin sentences. These initial observations prompted this study in CL and its potential to improve student motivation and, as a consequence, their accuracy in unseen translation.

Literature Review

Given the dearth of research into CL in Classics, this review will focus on three CL studies in different subject areas and analyse their effectiveness in improving student engagement and progress. Firstly, however, I feel it is pertinent to consider a study into the teaching of unseens, especially at secondary school level, to highlight some of the weaknesses in current unseen translation teaching methods which CL may ameliorate.

Unseen Translation

The Philoponia Project was set up in 2002 by the University of Cambridge and led by Emily Greenwood to ‘research the role of ‘unseen’ translations in teaching Greek and Latin … and to produce new materials for the teaching of unseens’ (Greenwood et al.,2003, p.7). The very existence of such a study suggests that there were felt to be failings in the current system of teaching and studying unseen translations and a desire to rectify them. The study reported that 94% of the 96 school teachers, who returned this initial questionnaire, believed that ‘unseens were an important part of language teaching in their department’, but there seemed to be ‘no clear policy on how the teaching should be done’ (Greenwood, et al. Reference Greenwood, Irwin, Lovatt, Low, Rogerson and Weeks2003, p.15). The motives for teaching unseen translations are clear: 53% of teachers ranked ‘acquisition of language skills’ and ‘practising for exams’ as the main objectives; studying unseens for a mere ‘appreciation of classical literature’ was a priority for only 18.4% of the respondent teachers (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Irwin, Lovatt, Low, Rogerson and Weeks2003, p.15). In accordance with the IBO's mark schemes, the emphasis which schools place on grammar and syntax is justifiable. Indeed, the questionnaire responses further reinforce this view, as over half the teachers revealed that they chose unseens specifically as an ‘illustration of a particular grammatical point’ (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Irwin, Lovatt, Low, Rogerson and Weeks2003, p.21). With such importance placed on unseen translations as both a teaching method for schools and an examination tool by examination boards, it seems vital that they are taught in the most accessible and engaging way possible.

Therefore, the second stage of the study involved creating a series of templates for teaching unseen translations, which allowed for more student engagement with the text, whilst building their independence and moving away from teacher-led exercises. To address the importance of unseen translations as grammar teaching tools, these templates included prompts ‘to get students to think more carefully about grammar and syntax … ranging from simple notes … on difficult grammatical or syntactical features to detailed exercises and questions’ (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Irwin, Lovatt, Low, Rogerson and Weeks2003, p.36). The majority of teachers responded positively to these templates; one is quoted as saying: ‘It wasn't a question of hand-holding so much as guiding, guidance which allowed them to tackle Latin beyond their usual capabilities and yet cope’ (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Irwin, Lovatt, Low, Rogerson and Weeks2003, p.45). However, it should be noted that the recipients of the trial materials were also those who responded to the questionnaire and therefore already had a proven enthusiasm for and commitment to the study. It can be said, therefore, that the outcomes may not wholly reflect Latin secondary teaching nationwide, but only a select minority. Nevertheless, the positive response to a focus on grammar and syntax in unseens is promising, and it would be interesting to see it further evidenced with school students’ opinions as well as teachers’. This study suggests that students became more engaged with the text, with the help of prompting questions and scaffolding. It is also encouraging, in terms of initiating a study in CL, that teachers felt the students responded well to more independence.

Co-operative Learning

Servetti, a teacher of English in an Italian liceo classico, carried out a study on two parallel fifth year classes, consisting of 42 18- 19-year-olds. The study ‘used Cooperative Learning as a technique for correcting students’ errors in order to motivate them, raise their attention, and encourage them to learn from each other’ (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p.7). Although the study was carried out in Italy, Servetti's results provide meaningful insight into not only the successes of CL at a small-scale level, but also the opinions on CL of the students themselves. As the students are of a similar age to my Year 12 class, their opinions towards CL are particularly relevant. The results of this study are especially pertinent because the experimental CL group was run alongside a control group, taught in a traditional teacher-led manner, and so a direct comparison of results can be made. The purpose of the study was to see how effective CL is in increasing the active engagement of students in correcting their test errors. It was carried out over six weeks and presents results from three tests: the pre-study test as the base-marker; the second test after one week to collect short-term data; the third and final test after six weeks to collect longer-term data. All the tests focus on the same grammar topic, and so the results can be compared fairly. The results seem to prove CL as an effective tool, especially in the longer-term. Whilst both the CL and the control class had drastically improved results in the second test, leaving the effectiveness of CL in the short-term inconclusive, the final test results are more favourable for CL. Although neither class improved on the results of their second test, the CL class seemed to have retained their knowledge much more successfully than the control teacher-led class. Whilst the CL class's marks decreased by an average of 3.67 marks, the control class’ decreased by 18.64 marks (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p. 15). Servetti remarks on the similarity of this outcome to her other studies focusing on different grammar points where ‘[CL] students reported higher accuracy levels than control students, often four weeks after the correction lessons and sometimes after nine weeks’ (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p.22). The correlation of these results seems to reveal that CL activities ‘have a longer-lasting positive effect on the students’ results than the traditional correction lesson’ (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p.21).

It is also important to consider the opinions of the students. The anonymous student questionnaire provided ‘very positive reactions’ (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p.22). In fact, all but one of the 19 students in the class ‘found the activity useful for their learning’ (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p.20). The students’ explanations were equally positive. One student stated that ‘I didn't remember all the rules but my classmates helped me, so I wasn't discouraged’ and another noted the significant impact of ‘not immediately asking the teacher for help’ (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p.20). Although a few students felt a lack of teacher involvement at some points in the lesson, it is encouraging that the majority happily and effectively worked co-operatively with their peers. It is also encouraging that students, without being prompted by a teacher, can make links to prior learning in order to justify their answers: students were able ‘to offer a grammar explanation’ for 76% of the examples in the correction activity (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p.19). However, it must be taken into consideration that students ‘were [already] familiar with and liked working cooperatively’ (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p.12). This, in my opinion, has a significant effect on the outcome of the study. Indeed, other case studies, including one by Gillies and Boyle (Reference Gillies and Boyle2010), report on the difficulties encountered by some teachers performing a CL study with students for the first time: ‘[the students had] to change their whole way of thinking and how they have done things for years. It's a whole new mindset for them’ (Gillies & Boyle, Reference Gillies and Boyle2010, p.934). A study by Harris and Firth (Reference Harris and Frith1990) faced the same insecurities about previously untested practice in their classrooms: their own inexperience as teachers combined with a lack of confidence in the students could prove disadvantageous.

Harris and Frith (Reference Harris and Frith1990) carried out a study which focused on the effects of co-operative group-work in a French class, consisting of 25 Year 8 girls at a single- sex comprehensive school in East London, and provides some very interesting insights into group composition. Through this small-scale study, the researchers (like Servetti (Reference Servetti2010)) again focused on the effect of CL in terms of improved learning outcomes and also the students’ opinions of group work. They designed the study to compare the results of a test at the end of a teacher-led unit to those of a test at the end of a CL group-work unit. The units were not, however, at the same level of difficulty and therefore the mark schemes had different expectations: to my mind, this does not allow for a fair comparison. Data were collected by means of the test scores and student questionnaires at the end of each unit. As in Servetti's study (Reference Servetti2010), CL seems to have led to an improvement in marks: ‘total average marks rose by 6.8%’ (Harris & Frith, Reference Harris and Frith1990, p.72). It is not a perfect system: ‘of the twenty pupils who were present for both tests, three pupils’ marks stayed the same, eleven pupils’ marks went up, and six pupils’ marks went down’ (Harris & Frith, Reference Harris and Frith1990, p.72). These results act as a reminder that no pedagogical practice will suit every student, given the variety of favoured learning styles. It does, however, illustrate the importance of the teacher's role during CL in ‘monitoring students’ learning and intervening to provide assistance’ when necessary (Johnson & Johnson, Reference Johnson, Johnson, Gillies, Ashman and Terwel2008, p.29). Servetti agreed, stating, that even though the students in her CL study were, on the whole, very successful, ‘revision in the plenary with the teacher was necessary’ (Servetti, Reference Servetti2010, p.19). I am unable to make a judgement on the effectiveness of teacher intervention as Harris and Frith do not elaborate on their role as teachers during the sessions other than ‘[they] tended to hover around’ (Harris & Frith, Reference Harris and Frith1990, p.73). It is unsurprising that the results recorded here were not as positive as those recorded by Servetti (Reference Servetti2010), given the increase in difficulty level between the two units. The choice of class may also be a factor: firstly, younger students could be less focused on grades since no public examination is dependent on their work, and secondly, as a compulsory subject, their enthusiasm level may not have been as high as those who had chosen to study French.

Despite some disputation over the validity of the test results, the responses of the questionnaire do provide reliable information. The majority of students (74%) said that ‘they felt they learned more in group work’ (Harris & Frith, Reference Harris and Frith1990, p.72). Although this is not fully evidenced by the test results, it is encouraging to know that the students felt more engaged with their work during the CL activities, even if enthusiasm merely derives from the ‘novelty of a new classroom organisation’ (Harris & Frith, Reference Harris and Frith1990, p.73). The comments from students regarding the groupings is also very telling. ‘64% of students preferred to be working with friends’ yet ‘72% of pupils said they though they actually learned better in mixed-friendship groups’ (Harris & Frith, Reference Harris and Frith1990, p.72). Harris and Frith recognise the social aspect as one of the advantages of CL: ‘[it] appears to be important… with the opportunity to get to know each other and to use each other rather than the teacher as learning resources’ (Harris & Frith, Reference Harris and Frith2010, p.72). There is no doubt that the social aspect of CL plays a large factor in the students’ enjoyment. As long as off-topic conversation is restricted, students can use the opportunity of interaction with peers ‘to interrogate issues, share ideas, clarify differences and construct new understandings’ (Gillies & Boyle, Reference Gillies and Boyle2010, p.933).

To explore the conversational aspect of co-operative group work further, I examined Gillies’ study (Reference Gillies2004), which focuses on the process of co-operative group work, not just the outcome but the conversational patterns of the students while they partake in CL. This Australian study was conducted on a larger scale than that of Servetti (Reference Servetti2010) and of Harris and Frith (Reference Harris and Frith1990), with 147 Grade 9 students from six high schools. The aim of this study was to assess the outcomes of parallel maths classes over a period of six weeks: three of the classes participated in ‘structured’ CL problem-solving activities, and the other three participated in ‘unstructured’ ones. According to Gillies, ‘structured’ CL includes ensuring that all group members are aware of the tasks and their specific roles in completing the task, and ‘are taught the interpersonal and small group skills needed to promote … a respectful attitude, a willingness to challenge perspectives and resolve conflicts as they arise’ (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.198). Gillies posited that students who had been taught how to work co-operatively worked better together as a group and were more likely to ‘develop an intuitive sense of each other's needs and will often provide help when they perceive it necessary’ (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.199). As in Servetti's study (2010), the school with the ‘structured’ CL activities had previously shown high levels of commitment to CL, and teachers had received extensive training before carrying out the study (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.203). The researchers recorded and transcribed the lessons and used a coding schedule (with nine interaction variables) to compile ‘information on student verbal interactions’ (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.202). The ‘structured’ CL group had a much higher frequency rate of explanations, both solicited and unsolicited, and more positive interruptions and lower negative interruptions, defined as ‘when a student yells out or butts in’ than the ‘unstructured’ CL groups (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.202). This suggests that the students in ‘structured’ groups have more respect for one another and work better as a group, as Gillies originally predicted. By videotaping the students, the researchers were able to accurately record the conversations and actions of the students. Data reliability was confirmed by ‘two observers, blind to the purposes of the study’ who checked the coding of six recordings (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.204). Gillies provides a disclaimer that coding accuracy was rated at between 83–92% (Reference Gillies2004, p. 204). This would account for unclear speech or actions not in direct view of the camera. Although the data cannot be seen to be completely accurate, it presents a useful sample of data for analysis. Gillies also thought it pertinent to collect students’ opinions on the activities, to ensure that there was a correlation in both teacher/researcher-perceived and student-perceived strengths. The student questionnaire, entitled ‘what happened in the groups?’, used the Likert scale of 1–5 for students to indicate ‘whether they perceived the behaviour [relating to 15 statements] almost never happened (1) to whether it almost always happened (5)’ (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.205). Whilst such a method for collecting data is easily collatable, it provides no opportunity for the students to explain their answers. Their responses, however, do add further strength to the argument that ‘structured’ CL ensures ‘cohesiveness and willingness to promote each other's learning’ (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.209). Students in ‘structured’ CL groups revealed that the three most frequently occurring behaviours and actions were that they ‘[were] free to talk…listen[ed] to one another… [had] opportunities to share ideas’ (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.208). A number of differences in group behaviour were highlighted between ‘structured’ and ‘unstructured’ groups. The ‘unstructured’ groups were more likely to interrupt or cut off other group members and have the conversation dominated by one or two individuals. This suggests that these groups were less able to share ideas, or indeed help each other.

In conclusion, the general success of the three CL studies has reaffirmed my intention to use CL as a pedagogical practice in my classroom. All the studies, to some extent, illustrate the academic and social advantages of group work. Servetti (2014) provided evidence to suggest that CL assists students with longer-term retention of information; Harris and Frith (Reference Harris and Frith1990), despite issues with data validity, presented a case for group work as a successful confidence-building exercise, which was enjoyed by the majority of students; Gillies (Reference Gillies2004), finally, demonstrated the importance of teaching the correct skills to carry out a ‘structured’ CL activity in order for them to fully benefit. With a greater awareness of the strengths and weaknesses in CL studies, I returned to the Greenwood et al. study (Reference Greenwood, Irwin, Lovatt, Low, Rogerson and Weeks2003) to ensure that I planned the most effective CL lessons on unseen translation, giving students a framework to work independently, and improve their grammatical accuracy as well as their overall confidence.

Research Questions

Given my findings in the above case studies I framed my research with the following three research questions:

RQ1 aims to gather the opinion of the class on unseen translations. Given the teacher's worries about the perceived disinterest of this class in these lessons, it was important for me to gather evidence, if any, of this disinterest. Identifying the aspects of unseen translation that the students find challenging is vital in planning effective subsequent lessons.

RQ2 and 3 aim to measure any improvement in unseen translations, especially focusing on the challenging areas highlighted by the students themselves in RQ1. With the aim of improving achievement and engagement, I needed to assess data relating to both factors independently.

Lesson Sequence:

I began by devising a series of nine lessons to be delivered over five weeks with the eight boys who had chosen to study Latin at Higher Level in the IB (as detailed above). I am aware that the time-scale and the number of students is small in its scope, and therefore any findings would be tentative. It is similar in scope and size to the Servetti (Reference Servetti2010) study and I hope the preliminary evidence gathered will warrant further study at a later date, if possible. Unlike the students in Servetti's study, this Year 12 class had little or no experience of CL. Therefore, it was important that I spent time explaining the structure of this series of lessons, and their roles within the group. Merely placing students in groups and expecting them to work together does ‘not promote cooperation and learning’ (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.198): structure seems to be vital to success, as demonstrated in her study.

In order not to disrupt the progress of lessons, I planned my CL activities on passages from Ovid's Metamorphoses, composed in a similar style to the unseens in Matthew Owen's book (Reference Owen2014) with which the students were familiar. As I was assessing the effectiveness of CL group work, it was important that the other aspects of the lesson remained familiar. For that reason, the students would tackle one story per week (see Supplementary Appendix 2 for the five-week scheme of work).

In order to provoke group discussion and provide written evidence of their thought-processing regarding grammar and syntax, I introduced the boys to a technique used by McFadden where students are encouraged to take ‘grammatical accountability’ (Reference McFadden2008, p. 5) by identifying and labelling grammatical structures. McFadden employed the use of iPads in the classroom to facilitate the electronic marking of subject, object and verb. The use of iPads was not available to me in my school and therefore I adapted the following technique; the text I gave the students was double-spaced, giving them enough room to make their annotations visible alongside the text. McFadden explains that, as part of psycholinguistic reading theory, the reader relies on a sentence meeting certain syntactic expectations: ‘This is the set of those essential items, variously called kernel, skeleton, or sentence structure, all of which designate variously the same essential elements of a sentence such as subject, verb, direct object, predicate noun, etc.’ (McFadden, Reference McFadden2008, p.3). This technique allows students to focus on what the students ‘see, not what they think would make the most sense’ (McFadden, Reference McFadden2008, p.7).

This method is not without criticism however, especially at a higher academic level. Hansen remarks that students who ‘persist in ‘solving’ each sentence through a ‘subject, then verb, then object, etc.’ hunt-and-gather system may never become comfortable reading quickly and confidently at sight’ (Hansen, Reference Hansen1999, p.174). I am inclined to disagree. Since there is no assessed speaking component, Latin affords students the opportunity to reflect on grammatical sense. Indeed, the mark scheme for the IB Latin Language paper rewards the skills of accurate grammar recognition and rendering. It is vital, in my opinion, that students are taught these skills and this method of annotating the text seems a perfectly viable means of doing so.

The introduction of a new translation technique at the same time as the CL group work does place the validity of the outcomes of the study in doubt. However, although the students had never visually recorded grammatical structures in this way, the idea of identifying each ‘kernel’ of the sentence was not new. It would be irresponsible to change too many variables at one time, but into ensure the boys provided written as well as oral evidence of their conversations during CL group work, I thought this was worth initiating. Given the boys’ propensity to sit, and communicate, only with their friends within the class, I chose the groupings for the activities. I wanted to remove the social boundaries of the classroom and work together for the benefit of everyone. Indeed, ‘it is preferable for students to cooperate rather than compete’ (MacQuarrie, Howe & Boyle, Reference MacQuarrie, Howe and Boyle2012, p.528).

Each student was allocated two groupings. Grouping 1 split the boys into two groups of four (Groups A and B), for the first lesson of the week. Each was given half of the passage to translate. Eight lines seemed a reasonable amount for each group to translate in one 50-minute lesson. In the second lesson of the week, the boys were again placed in two groups (Grouping 2), each consisting of two members of Group A and two members of Group B. This new combination would enable the students to write a complete translation, and allow the four students to take turns in the roles of teacher and learner as they moved through the passage. Topping and Ehly confirm that ‘especially in same-ability projects, roles need not be permanent. Reciprocal learning can have the advantage of involving greater novelty and a wider boost to self-esteem, in that all participants get to be helpers’ (Topping & Ehly, Reference Topping, Ehly, Topping and Ehly1998, p.11). Furthermore, Gillies states that ‘it is a basic tenet of Cooperative Learning that when group members are linked together in such a way so they perceive that they cannot succeed unless they all do, they will actively assist each other to ensure that the task is completed and the group's goal obtained’ (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.197). I too wanted to ensure that all the boys took responsibility for not only their own learning, but also that of their group. (See Supplementary Appendix 1 for a list of the groupings). Given the importance of communication I also decided to move the table in the room in order to meet Johnson and Johnson's recommendation that the students are ‘close enough to each other that they can share materials, maintain eye contact with all the group members, talk to each other quietly without disrupting other learning groups, and exchange ideas and materials in a comfortable atmosphere’ (Johnson & Johnson, Reference Johnson and Johnson1994, p.105). With this in mind I got each group of four to sit in pairs facing one another around two tables, rather than in their traditional long row.

Ethical Issues

According to the British Educational Research Association (BERA) ‘in all actions concerning children, the best interests of the child must be the primary consideration’ (BERA, 2011, p.5). Before commencing the study, I explained the scope of the study to the students, who all agreed to participate and granted permission for me to record and collate transcripts of lessons. I ensured them of their right to anonymity on questionnaires and all students have been anonymised in transcripts and translation exemplars to protect their identity. Written consent was also obtained from the Head of the Department before I commenced the study.

Methodology

This study draws on approaches of action research strategies, which Denscombe defines as ‘hands-on, small-scale research … on practical issues … in the real world’ (Reference Denscombe2014, p.122). The aim is not only to analyse the Year 12's attitude to unseen translation but to ‘set out to alter things’ (ibid. p.122). Nevertheless, as Denscombe indicates, such research is ‘vulnerable to the criticism that the findings relate to one instance and should not be generalised beyond [the] specific ‘case’’ (ibid. p.128). Whilst this may be true, changes at micro-level should not be dismissed as they create the opportunity for greater changes in practice later on. Indeed, the cyclical process of action research, where ‘research feeds back directly into practice’ (ibid. p.125) is advantageous to both the students, who will hopefully receive improved practice, but also myself, as a teacher focused on professional development.

Research methods

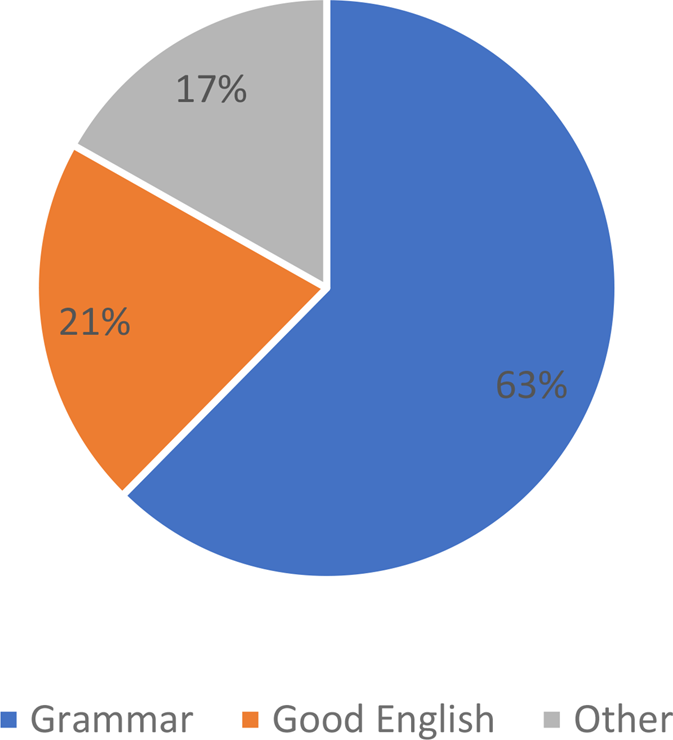

I planned to use a range of data collection methods in order to answer my three research questions as outlined in the table above (see Table 1).

Table 1. Research Questions and Data Collection Methods

Questionnaires and Interviews

A pre-study questionnaire (See Supplementary Appendix 3) was issued at the beginning of the study to ascertain the boys’ attitudes towards unseen passages and to identify what they saw as their weaknesses. I followed this up with a post-study questionnaire (See Supplementary Appendix 4) to determine whether the CL group work had improved their attitude towards unseens. Given the knowledge that questionnaire data are often disadvantaged by a ‘poor response rate’ (Denscombe, 2007, p.202), I specifically designed brief questionnaires, so that they could be completed in lesson-time, without detracting too much from students’ learning. This method allowed me to collect a large amount of data in a short period of time. Given the brevity of the questionnaire, it was important to allow students the ability to expand and clarify their answers at another time. I, therefore, organised a focus group meeting, at a break time, for four of the students. This gave me the opportunity to explore areas of interest, highlighted in the initial questionnaire, without impacting on their learning time.

Transcripts and Observation Notes

Although my own and the regular class teacher's observations into the class's behaviour and attitude can in part provide evidence for the research questions, they are reliant on ‘selective perception’ (Denscombe, Reference Denscombe2014, p.206). In order therefore to attempt to triangulate the data, I made audio recordings of the group work and transcribed the students’ spoken thought processes during the group work. This allowed me to consider their attitude towards their work, and their translation methods, throughout the group work. It would allow me to collect evidence of any improvement in confidence and accuracy of translation, in order to answer RQ2 and RQ3 respectively. I also wanted to ensure that any perceived improvement indicated by the student in their post-study questionnaire could be confirmed in their classwork.

Findings and Discussion

RQ1: Do students find unseen translation challenging and if so, what aspects of unseen translation do students find the most challenging? Why?

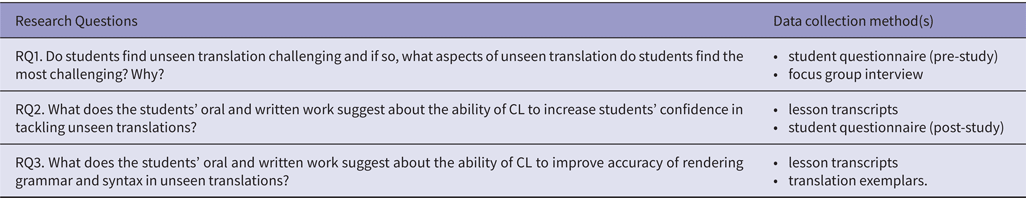

My pre-study questionnaire provided rather convincing initial evidence that the Latin department's concerns regarding the boys’ negative attitude were well-founded. In order to base their confidence against comparable data, I asked the boys to mark their confidence at tackling unseen translations and pre-prepared set text translations on a scale of 1–10.

All the boys felt less confident in unseen translations (see Figure 1): on average they rated themselves at 5.6 out of 10 for unseen translation, in comparison to an average of 7.75 out of 10 for the pre-prepared set text.

Figure 1. Student's confidence: Unseen Translation v Prepared Set Text Translation

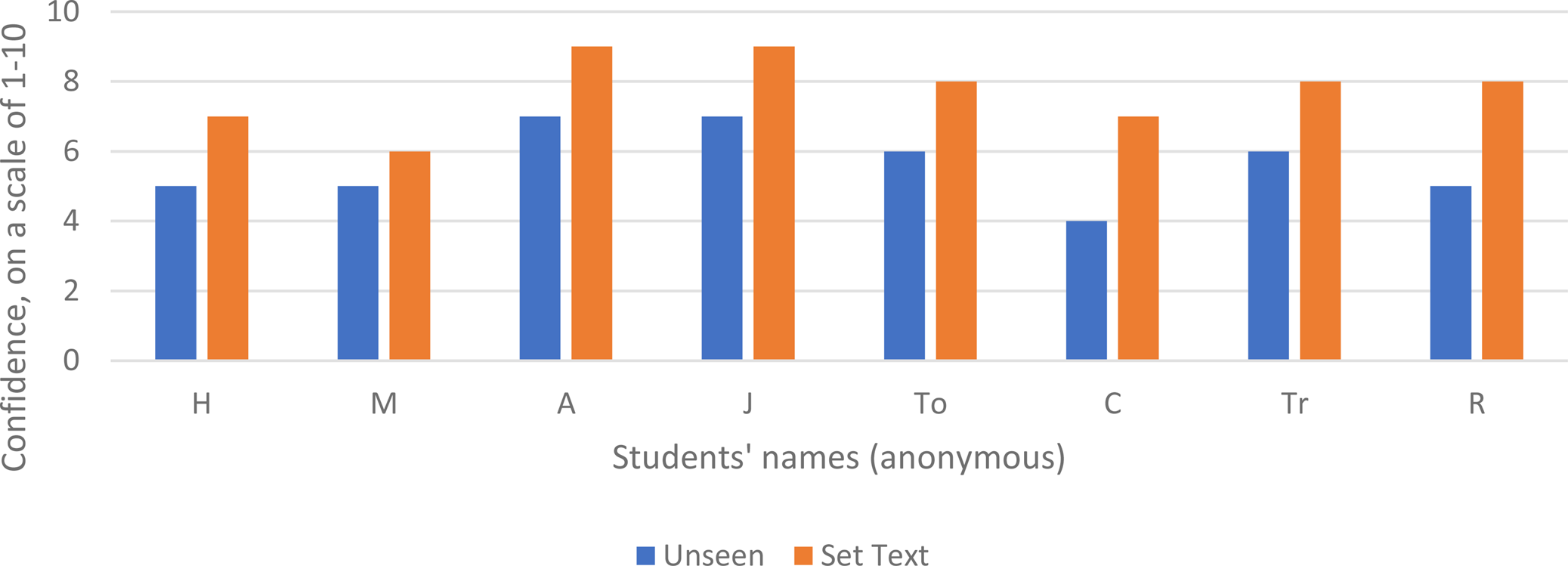

In response to question 4, where I asked the students to indicate the particular aspects of unseen translation that the students found the most challenging, I grouped their answers into three categories:

1) grammar and syntax (identifying clauses; identifying subject/ object/verb; correctly identifying verb endings; correctly identifying noun endings; adjective and participle agreement);

2) forming good English (choosing the right definition for unknown vocabulary; transforming a literal translation into better English);

3) other issues (the length of the passage; the complexity of the plot). Almost two-thirds of their responses related to grammar and syntax (see Figure 2).

Given the students’ answers to Question 1 regarding their confidence towards unseens, it surprised me that in response to Question 5 [do you enjoy translating unseen passages?] none of the boys said they disliked it: four replied that they were ‘unsure’ and four replied that they enjoyed it. Whilst five of the boys stated that the unseens presented them with a ‘challenge’, they did not suggest that this was problematic. I took this as an encouraging sign that the students’ lack of confidence in their ability was not detrimentally affecting their enthusiasm for the subject.

Figure 2. Challenging aspects of Unseen Translation

Having recorded the data from the initial questionnaires, I then took four boys aside for a recorded focus group. Since I had observed the class, I knew that all the boys had received formal grammar lessons, and so wanted to enquire further into why grammar and syntax posed such an issue in unseen translations.

I wrote on the whiteboard fluctibus erigitur and asked the boys to translate the phrase without conferring. None of the boys could translate it accurately. The four answers were a variant on Student H's answer: ‘it raised up the waves’; or Student A's: ‘the waves were raised up’. Yet when I questioned them on the grammar of the phrase, they could all identify the case of fluctibus as a dative or ablative plural and erigitur as a passive verb. When prompted, they knew that the dative is translated as ‘to/for’ and the ablative as ‘by/with/from’. I then asked the boys to explain their translation. Student H admitted: ‘I'm not really sure…I know what the words mean…so I just try to make the most English sense out of the words on the page. Grammar doesn't always come into it’. Student C continued: ‘There is so much pressure to get a translation down that we forget things like that’. The boys all nodded in consensus. This confirmed their response in the questionnaire which revealed that grammar was the most challenging feature in unseen translations. It is curious that although, it seemed that, although the boys were competent at recognising grammatical forms, they lacked the ability to translate them in context. However, I was encouraged that during group discussion, in a situation similar to the focus group, the students could recognise the grammatical features of the text and question each other's decisions. I also predicted that by following the technique used by McFadden (Reference McFadden2008, as explained above) the students would have greater scope to accurately render grammar in this activity, and that the students’ group conversations would increase their confidence in their own knowledge and encourage them to employ it in context as a tool for translation.

RQ2: How does CL increase students’ confidence in tackling unseen translations?

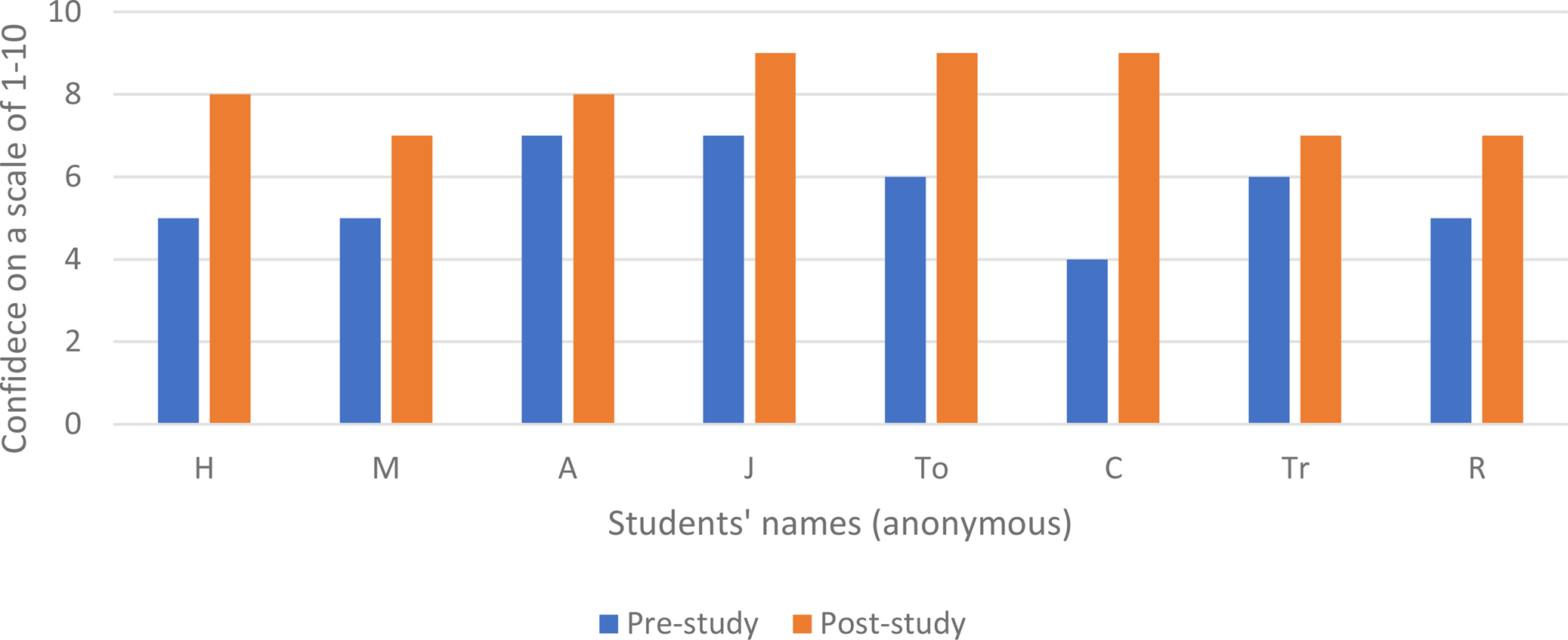

In the post-study questionnaire, I repeated Question 1 (how confident do you feel at translating unseen passages?) from the initial questionnaire. In this way I was able to compare the results from both questionnaires in order to see if the CL group activities had made any impact on the students’ confidence. Strikingly, all the students recorded an increase in confidence at translating unseen passages (see Figure 3). The average increase is 2.4 scale markings. There are however a number of factors that may have influenced these results and some of the problems regarding questionnaire reliability are outlined above. I therefore asked the students to write a comment about their experience during the study, most specifically about working in small groups as part of the CL method. Aware of the influence of leading questions, I wanted the students to have the opportunity to write freely about the experiences. Their responses correlate with their scale-rankings, indicating a positive outcome. Two students noted their apprehension of CL at the beginning of the task; one student wrote that ‘it was a little strange at first because It is a completely different way of working…but I soon settled into it’ (Student Tr). Indeed, I had predicted that, even with an introductory lesson to explain the principles of group work, an activity so far removed from their normal independent classwork, would cause some initial concerns. It must also be taken into consideration that the students’ positive reactions toward CL may have been, in some part, due to its novelty.

Figure 3. Student's confidence at Unseen Translation: Pre-study v Post-study

These positive remarks can be separated into two main categories: 1) sharing of ideas; and 2) increased learner independence:

1) Increased confidence through the sharing of ideas:

‘I felt more able to express myself in front of my group… it didn't really matter if someone got something wrong. We were all in the same boat. We could all help each other out’ (Student A).

‘It is good because we all have different strengths and weaknesses and this way we have a much better chance of working out the translation, and hopefully learning tips for the future’ (Student J).

‘I've learned techniques from my classmates. And I've been able to help them as well’ (Student C).

‘I wish we could use group work in more subjects…I find it a really useful way to share ideas and help each other decide on the best answer’ (Student H).

The responses of these Year 12 boys correspond with the known social advantages of CL learning, illustrated in the earlier case studies. Without assuming the roles of ‘tutor’ and ‘tutee’ within their groups, the boys were able to utilise their strengths and seek help for their weaknesses when necessary, fluidly changing between giving and receiving help (as Student J noted). The ability for them to recognise their own strengths played a large role in increasing their confidence, in my opinion. Using evidence from the transcripts, I noted that when a student interjected with a helpful remark to assist his peers, this was often followed by an exclamation of pride from the student himself or praise from his peers.

Student C, after correctly identifying a neuter plural accusative noun in certamina, cheered himself, and when Student A correctly pointed out that sumpsisse was a perfect infinitive, his group complimented him. What was even more encouraging is that both Student A and C, in these examples, were able to explain their thinking further. Student A referred to the table in their grammar books, and Student C double-checked the gender of certamen in the dictionary. Throughout the transcripts of the six group sessions, there were numerous examples of this. From my own observations during the lessons, the boys keenly wrote down not only the translation that they were working on but also notes of advice from their peers around the edge of their work. Student H's praise of the effects of CL pedagogy (quoted above) provides probably the best support for its future employment in the classroom.

2) Increased confidence through increased learner independence:

‘It was nice that the teacher could trust us to work by ourselves’ (Student H).

‘It was a real confidence boost when we managed to work out the translation without the teacher's help’ (Student R).

Although, as the earlier case studies revealed, there is a risk in allowing students greater independence in their learning, their comments show a more positive outcome. I was aware that students may have misused the opportunity and found a more social setting a distraction from the work, but I did not find that to be the case here. There could be a number of reasons for this: firstly, the eight boys are all very motivated and conscientious, and they understand the importance of hard work and the consequences of their effort and behaviour on future examinations; also, the classroom is small and with two members of staff circulating the room, the opportunity to be distracted was, indeed, very limited.

Although there was a small amount of non-work related conversation, both groups always reached the set target by the end of the lesson. It is encouraging that the students appreciated the level of trust required for such an activity to be successful and they acted accordingly. With the role of the teacher much reduced, the students needed to rely on group work skills to translate the text.

The students’ comments on the questionnaire are reinforced by teacher observations during the group work. Both the regular class teacher and I noted a more positive atmosphere in the classroom, implying that the students were both engaging with, and enjoying, the text. He remarked that ‘it is pleasing to see the boys helping each other out. They seem to be more willing to offer ideas and work things out. They are less conscious about making mistakes… their discussion really seems to be helping them’. The combination of team work and a greater reliance on their own knowledge rather than that of the teacher has led to an increased in confidence, noticed by both the students and teacher.

RQ3: How does CL improve accuracy of rendering grammar and syntax in unseen translations?

The students’ main grammatical concerns, highlighted in the initial questionnaire, were as follows: identifying clauses; identifying subject/object/verb; correctly identifying verb endings; correctly identifying noun endings; adjective and participle agreement. This became my focus for assessing an improvement of accuracy.

From a purely observational perspective, the regular class teacher was impressed with the improvement: ‘it is great to see the boys using their knowledge and helping each other out…they are producing far more accurate and conscientious translations by doing so’ (Teacher T, interview, 2016). It was important that I also confirmed this opinion with evidence from the students’ work. The spoken thought-processes that I recorded during the group work seemed to reveal a pattern of dialogue when interpreting a text. In the first two passages the boys were asking questions aloud, and in a very logical manner, in order to ascertain each other's expectations of the syntax. For example, the following conversation took place between Students C, H, J and To while translating the first passage:

Student H: Right, we need to start with the verb…

Student C: erat… is.

Student H: was. erat is imperfect.

Student J: It is singular though, so we need a singular subject.

Student C: regia? that looks nominative, like puella, is it?

Student To: [AFTER LOOKING IT UP IN DICTIONARY] Oh…it's an adjective, royal. What is it describing?

Student H: turris could be feminine… yep, that's right, so we have… a royal tower was…

Student To: Does additia also agree with it?

Student C: Is that a PPP? How do we translate those again?

Student H: Having been added?

Student J: Yes… The royal tower, having been added…., was. How does vocalibus muris fit in?

Student H: They are dative plural.

Student J: Or ablative [HE POINTS TO HIS TABLE OF NOUN ENDINGS].

Student C: Okay, which makes the most sense here? Dative probably… added to something.

Student To: To the vocal walls?

Student C: Yeah, but this doesn't make sense…The royal tower having been added to vocal walls, was. Was what? That's the end of the clause…

Student H: Could it be There was a royal tower?

Student To: Oh, yeah, Miss mentioned that once!

During this process, it was encouraging that students were all getting involved in the discussion and asking questions of one another and correcting each other. The boys made use of their grammar notes and dictionaries in order to double-check their assumptions and explain their answer to the group. No statement was unfounded, and, indeed, the boys were keen to explain themselves.

When I took in examples of the boys’ work, I noted that most of the boys had accurately marked S (subject), O (object), V (verb) over the text and bracketed off clauses. They were linking adjectives and paying attention to the agreement of gender, number and case. It seemed that visual reminders made all the difference: ‘It's so useful to look at every word and work out its role in the sentence, that way it all fits together better, if you write it down you can join it all up, like a puzzle. It's so much easier to see it on the page’ (Student H). Another remarked: ‘Why did we not do this earlier?’ (Student C). However, given the students’ early translation attempts in the focus group, it seems likely that without the CL exercise, granting them the opportunity to verify their knowledge, accurately determining parts of speech may not have been so easy, or useful.

By the third passage, the conversations between the students were much briefer and discussions focused on more complex structures such an indirect statements and uses of the subjunctive. Yet, the accuracy of simple clauses, did not decline: this implies that the group dialogue had been internalised, and only spoken aloud when one member of the group had doubts. This is extremely promising, as, although CL is a useful classroom exercise, the students, for their exams, do need to retain these skills for independent work.

Conclusion

As predicted from the findings of previous case studies, where CL activities are used to facilitate ‘intellectual and social development of the students’ (Hertz-Lazarowitz, Reference Hertz-Lazarowitz, Gillies, Ashman and Terwel2008, p. 39), this study provided similar initial evidence in support of both aspects. The boys seemed to appreciate the level of trust placed in them to work independently, and this was reflected in their work. They supported each other in order to come up with the best translation, utilising each other's strengths. This process increased both accuracy and confidence, and it could be that the two are inextricably linked. Gillies stated that ‘CL capitalises on adolescents’ desires to engage with their peers, exercise autonomy over their learning, and express their desires to achieve’ (Gillies, Reference Gillies2004, p.197), and this desire was certainly evident in this study: the boys responded positively to the CL translation activities.

This study demonstrates the success of CL translation activities from both this particular group of students’ perspectives and those of their teacher. Indeed, since the responses to this small-scale CL study seem to be overwhelmingly positive, they seem worthy of further study. It would be worthwhile to test the advantages of CL group work in the longer term with this same class, and also to broaden its scope, by including other classes to see if the results are consistent.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2058631021000404.