Unlike other Shakespearean tragedies, King Richard III was never turned into a comedy through the insertion of a happy ending. It did, however, undergo a transformation of dramatic genre, as the numerous Richard III burlesques and travesties produced in the nineteenth century plainly show. Eight burlesques (or nine, including a pantomime) were written for and/or performed on the London stage alone.Footnote 1 This essay looks at three of these plays, produced at three distinct stages in the history of burlesque's rapid rise and decline: 1823, 1844, and 1868. In focusing on these productions, I demonstrate how Shakespeare burlesques, paradoxically, enhanced rather than endangered the playwright's iconic status. King Richard III is a perfect case study because of its peculiar stage history. As Richard Schoch has argued, the burlesque purported to be “an act of theatrical reform which aggressively compensated for the deficiencies of other people's productions. . . . [It] claimed to perform not Shakespeare's debasement, but the ironic restoration of his compromised authority.”Footnote 2 But this view of the burlesques’ importance is incomplete. Building on Schoch's work, I illustrate how the King Richard III burlesques not only parodied deficient theatrical productions but also called into question dramatic adaptations of Shakespeare's plays. In so doing, these burlesques paradoxically relegitimized Shakespeare.

Examining the burlesques of King Richard III is revealing in more than one respect. In 1828, The Stage; or, Theatrical Inquisitor claimed that Richard III was “a character which ha[d] ever been deemed sufficiently important to stamp the man who [could] best delineate it the Roscius of the day.”Footnote 3 Indeed, King Richard III was extremely popular on the nineteenth-century stage, and actors saw its title role as the road to stardom and “legitimacy.” However, as I have argued elsewhere, in the nineteenth century King Richard III was largely a “hybrid” play and in several ways tainted by “illegitimacy.”Footnote 4 Showing how the tragedy was rendered in burlesques, and highlighting the success it enjoyed in this form, foregrounds the play's hybrid nature and its latent illegitimacy, not to mention the permeability of cultural hierarchies in the nineteenth century. Tracing King Richard III's migration from Covent Garden and Drury Lane to less refined establishments emphasizes how major and minor theatres were “shaping one another,” and the “theatrical traffic [moved] to and from the major theatres and the ‘illegitimate’ stage.”Footnote 5

Today, we distinguish between “burlesque” (a high treatment of low subjects) and “travesty” (a low treatment of high subjects) and, consequently, most nineteenth-century Shakespeare burlesques should be considered travesties. At the time, however, the two terms were used interchangeably in playbills, on title pages of plays, and in accounts of performances, and the genre was commonly called “burlesque.” In Shakespeare burlesques, his plots and characters were typically transported into an alien (usually popular) setting, and the style of the original was debased. Mikhail Bakhtin wrote that “in parody two languages are crossed with each other, as well as two styles, two linguistic points of view, and in the final analysis two speaking subjects. . . . Parody is an intentional hybrid. . . . Every type of intentional stylistic hybrid is more or less dialogized. . . . Thus every parody is an intentional dialogized hybrid.”Footnote 6 The double-voicedness of parody is eminently manifest in Shakespeare burlesques, where not only the plots of the source texts are simplified and trivialized, but the original language and style are fiercely lowered: rhyming couplets substitute blank verse and, as regards the register, a familiar, popular, colloquial, even vulgar lexicon is used. Still more, as I demonstrate, in such burlesques comicality springs precisely from the relentless clash between high and low, formal and informal.

As hinted before, I have chosen King Richard III not only for its popularity,Footnote 7 but also for its atypical stage history. This play is unique in having been played throughout most of the nineteenth century, not in Shakespeare's version, but in Colley Cibber's 1699 adaptation. This “improved” version outlived all other Restoration adaptations and was virtually unchallenged until Henry Irving, first in 1877 and then in 1896, produced his own version of the play. Cibber's play follows Shakespeare's plot. Unlike other adapters, Cibber did not add new characters and introduced only a few new episodes: the murder of Henry VI in the Tower that opens the play (which is taken from Henry VI, Part 3), an exchange between Richard and Lady Anne where Richard cruelly communicates his detestation to his tearful wife to incite her to commit suicide, and a heart-breaking farewell between Queen Elizabeth and the Princes. Nevertheless, Cibber substantially modified the character of Richard, magnifying his iniquity (in the first three acts) and heroism (in acts 4 and 5), while presenting a simpler, less ambiguous character than Shakespeare's. His duplicity is downplayed, and he is more direct in his intent.Footnote 8

Since the stage King Richard III was already an adaptation of Shakespeare's text, burlesques of this play are peculiarly complex. On the one hand, they are second-degree adaptations; on the other hand, they often include small restorations of the original text the parodists introduced to create an interesting interplay between the different versions of the play: Shakespeare's Richard III and the “spurious” Richard III of the theatre. Such operations challenged what passed for Shakespeare on the contemporary “legitimate” stage and, in so doing, paradoxically reinstated the dramatist's “threatened” authority. In my discussion, I rely on three critical categories—localization, domestication, and topical allusion—to refer to the strategies the parodists adopted when travestying their originals.Footnote 9 Localization involved transferring of the action of Shakespeare's plays to contemporary London; domestication aimed at rendering characters, scenes, and plots familiar to the audience; whereas topical allusion consisted in referring to contemporary events and topics of conversation.

In 1920, in one of the first studies on the subject, R. Farquharson Sharp defined the hands of the Shakespearean parodist as “sacrilegious.”Footnote 10 Nineteenth-century authors of burlesques thought differently. For example, in 1888, the writer, editor, and burlesque composer Francis Cowley Burnand championed the legitimacy of the form in an essay entitled “The Spirit of Burlesque.” In it, he declared that burlesque is

“the candid friend” of the Drama, who, in as pleasant a way, and in as personally inoffensive manner as possible, by means of parody, travesty, and mimicry, publicly exposes on the stage some preposterous absurdities of stagecraft which may be a passing fashion of the day, justly ridicules some histrionic pretensions, parodies false sentiment, and shows that the shining metal put forward as real gold is only theatrical tinfoil after all.Footnote 11

Burlesque attacked what was “false, pedantic, pretentious, snobbish”;Footnote 12 it chastised the aberrations and distortions that took place when “a work of genius” was “spoilt, or injured, by the misinterpretation of self-complacent mediocre actors,” or “rendered ridiculous by extravagant realism in production.”Footnote 13 Thus, far from being the destroyer of Shakespeare's authority, burlesque would paradoxically be its restorer.

In the following analysis, I argue that Burnand's claim was accurate in more than one way. First, Shakespeare's plays addressed the issues of his times, and the authors of burlesque pieces based on Shakespeare, with their topicalities, localizations, and domestications, strove to make the Bard's plays contemporary again by “updating” them. As Schoch observes, “If the virtue of legitimate Shakespeare was durability, then the virtue of burlesque Shakespeare was novelty. . . . [T]he burlesque's injunction might be ‘always contemporize.’”Footnote 14 Second, these burlesques frequently used parody to expose cleverly the “aberrations and distortions” of contemporary “legitimate” productions, which reveled in hyperrealism and historical reconstructions. Third, since the King Richard III that passed for Shakespeare's at the time was Cibber's version (and the authors of the burlesques I examine appear to have been aware of the distinction), the parodic plays highlighted the limits of Cibber's play, meaning that they revealed to what extent “the shining metal put forward as real gold [was] only theatrical tinfoil after all.” With Burnand's argument in mind, I demonstrate how Shakespeare burlesques did not compromise the playwright's iconic status, but rather boosted his authority by offering fresh perspectives on a play that was typically produced in a “mangled,” “jumbled,” “patchwork” form.Footnote 15

King Richard III. Travestie (1823)

Like other Shakespeare burlesques composed in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the anonymous King Richard III. Travestie took John Poole's Hamlet Travestie as a model. It was published in 1823Footnote 16 and is only two acts in length, which the author justified by stating that Poole's 1810 Hamlet's Travestie, in three acts, had failed on the stage due to its length.Footnote 17 In spite of such compression, there is no evidence that the piece was ever performed. It nevertheless stands as an important marker in the development of the burlesque tradition in that it was the first to introduce two features that would become standard practice: humorous descriptions of the dramatis personae and the resurrection of characters who have died in the course of the action (they dance together as the curtain falls). This burlesque was also the first to introduce puns and jokes related to Gloucester cheese, a common feature of later nineteenth-century travesties of Richard III: Richard, while wooing Lady Anne, asks her if she would “choose a cheese cake or a tart,” and she replies, “Of all the cheese that's in the world, O give to me plain Glo'ster.”Footnote 18

Topical allusions are the distinctive feature of Shakespeare burlesques but they are peculiarly abundant in this text. What follows is the facetious description of the villainous protagonist in the “Persons Represented”:

Richard, Duke of Glo'ster, a little, crooked, fierce-looking Man, with a hoarse Voice, carrotty Whiskers, and long Spurs; fond of Cutting and Maiming; a second Sixteen-string Jack, with Nine Lives like a Cat; a bit of a Miller—always draws a crowded House at his Benefit; but in his last Engagement, receives a Muzzler from Richmond, (the Black) which does him up Brown. (6)

This short description contains numerous contemporary references. For example, John Rann, alias Sixteen String Jack, was a notorious yet charming highway robber who wore eight brightly colored ribbons tied around each knee representing the times he had been acquitted. Executed on 30 November 1774, his popularity endured into the nineteenth century, with a play by William Leman Rede entitled Sixteen String Jack produced at the Coburg Theatre in February 1823. Even more interesting is the reference to a famous pugilist who had retired almost a decade earlier: the Black American Bill Richmond.Footnote 19 We are told that Richard III too is a bit of a Miller (slang for a “prize-fighter”), and that he is eventually defeated (“in his last Engagement”) by Richmond the Black, with a Muzzler (in boxing slang, “a blow on the mouth”).Footnote 20

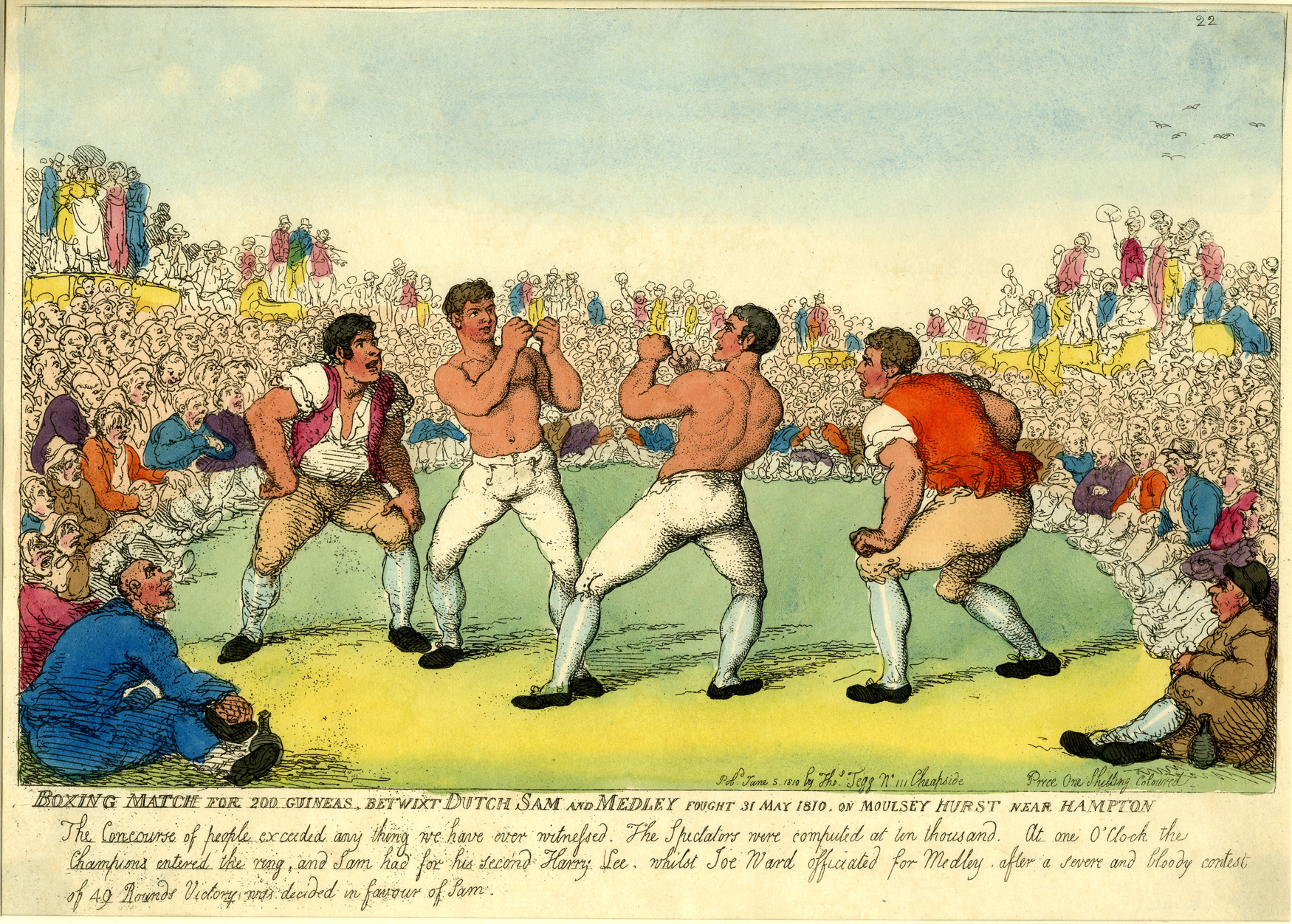

This short quotation offers some idea of the range and frequency of topical and local references in travesties and burlesques. Playwrights appealed to audiences with references from the criminal underworld, from boxing, from fashions in costume, and from life in London in general, but also from politics and, quite obviously, from the theatrical world. All this worked to return “Shakespeare” to contemporaneity. Here, the boxing metaphor is used consistently throughout the play. Buckingham is presented as Richard's “Bottle Holder” (6), but in act 2 he betrays Richard and joins the party of “the bold Dutch Sam” (38), another pugilist who had been extremely popular in the previous decade. As the facetious description quoted above announces, the climactic fight between Richard and Richmond is demoted to a boxing combat in the Prize Ring at Moulsey Hurst (a nineteenth-century sporting venue used for cricket, prizefighting, and other sports; Fig. 1). The tradition of substituting “a pugilistic trial of skill, in the last scene, for the more elegant exercise of the rapier”Footnote 21 had been inaugurated by Poole's Hamlet Travestie, and boxing matches regularly replaced duels and sword fights in Shakespeare burlesques.

Figure 1. Dutch Sam boxing on Moulsey Hurst. Hand-colored etching, 5 June 1810. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

However, the comic representation of working-class leisure activities like boxing does not mean that these entertainments were written for a laboring-class audience, nor does it mean that the author endorsed a socially progressive outlook. Rather, as Schoch has argued, the theatres that attracted working-class audiences preferably staged melodrama, whereas Shakespeare burlesques appealed to the educated middle class and, in particular, to the so-called “‘men about town’ who had professional careers, disposable income, leisure time, and no domestic responsibilities.”Footnote 22 Indeed, appreciating the burlesque's pointed satire required familiarity with legitimate Shakespeare (and with the Bard's plays in general), which was more easily within reach of middle-class audiences. Although burlesques spoofed the middle-class cult of respectability, they did not do so on behalf of the working class and, generally, they did not give voice to class-based antagonism.Footnote 23

Heavy drinking is another recurring topic in this 1823 travesty, which again corresponds with the low treatment of high subjects typical of burlesque. Richard uses alcohol to win Lady Anne, who, as the opening description explains, is fond of “a drop of Blue Ruin” (6; i.e., of low-quality, home-made gin). His plan is clear from the start, since he confidently tells the audience: “if she refuses, I'll ask her to drink” (13). His strategy is obviously successful, and later on Lady Anne, singing to the tune of “False Man, You Courted Sally,” regrets her pliability:

Lady A.: False man, you courted Anne, O,

With punch you filled her noddle;

Yes, yes, you wicked man, O,

Until she could not waddle.

And then you basely took, O,

Advantage of her weakness. (24)

This strategy, indeed, is a clever expedient to overcome the improbability of the courtship scene, which had been a serious cause of embarrassment to eighteenth-century sentimental critics.Footnote 24 Richard tries the same stratagem to convince the Queen to let him marry her daughter “Bet,” but this time he fails:

King R.: Stop—you have a daughter, called Bet.

Queen: Must she die too?

King R.: Die! Oh, no! here, take a drop of wet.

[Hands a Bottle which he takes from his Pocket]

AIR, “Cease your funning”

Queen: Cease your blarney, and your carney,

To seduce my daughter Bet,

All the Gin, Sir, that's within, Sir,

I've a mind for to upset,

T'is [sic] most certain, the bed curtain,

Never shall enclose you both;

You would woo her, and undo her,

But you'll find her very loath. (41)

These scenes are reminiscent of eighteenth-century comic pieces such as John Gay's 1728 Beggar's Opera, in which drink is employed for parodic purposes. In King Richard III. Travestie, the influence of Gay's ballad opera—itself a burlesque of the contemporary vogue for Italian operatic styles—is overtly underlined by the use of the melody from “Cease Your Funning.”Footnote 25 Drinking runs like a leitmotif throughout this travesty: King Edward is referred to as “the drunken jockey” (17); on his death, Stanley wants to comfort the Queen with “a drop of jackey” (19; a slang word for gin, the most popular drink of the period), and, at the end of the scene, the idea is reproposed by Gloucester himself through the air “Come Let Us Dance and Sing”: “All the day let's dance and play, / The blind fiddler I will pay / We will drink, ’till we blink, / To drive dull care away” (21). Then, as one would expect from her, when Lady Anne's Ghost rises at the end of the play, she declares: “I will keep a brandy shop / And drink away the profit” (52).

Burlesque's transposition from high to low involved the setting, the situations, and the language. “Bet,” which substitutes for Elizabeth in the above-quoted exchange, is not the only diminutive used in the play: King Edward at times becomes “Neddy” (12) and “Poor Ned” (19), and the crowd is urged by Buckingham to cry out “Long live King Dick!” (27). Street slang and colloquialisms abound, and sense is sacrificed to sound in what, at times, appear as endless chains of puns. Although based on Cibber's adaptation, this burlesque begins with a parody of Shakespeare's Richard's opening soliloquy rather than King Henry's murder in the tower.Footnote 26 Here, the author uses rhymed couplets to spoof Richard's arch-famous lines:

Glo'ster: Now are our mugs bound up with napkins,

Our broken heads, like broken pipkins

Patch'd with court plaister—but the sun of York

Shines so upon our cribs, it fries like pork!

Fierce phized war has smooth'd his tripey jowls,

And now, instead of mounting—by goles,

He to the lady's snoozing-ken doth hop,

And all the blessed night with her doth stop,

To listen to her thrumming on the lute,

And tip her “Off she goes” upon his flute.

But I, that am not made for larking tricks,

To play on flutes made out of walking sticks; . . .

Why then to me this bustling world's but dead,

Till this my bread basket's aspiring head,

Stop the same hole that Harry's block hath fill'd, –

To stop a hole, ’faith many a one's been kill'd.

This night before he can reach the bannister,

With my fist will I split his cannister. (7–8)

These lines, with their slang words (“mugs,” which stands for “faces, esp. unattractive ones,” OED), colloquialisms (“tripey” and “larking,” which mean, respectively, “inferior, trashy, rubbishy, worthless,” and “frolicsome, sportive,” OED), oaths (“by goles”), domestication (“court plaister” and “walking sticks”), not to mention the concluding debased reformulation of Richard's unbridled libido coronae (where “bread-basket” is the name pugilists gave to “the stomach”),Footnote 27 set the tone for the whole piece. In this travesty too, Shakespeare's tragic characters are demoted to the level of ordinary Londoners, and their use of modern-day slang can be seen as a strategy for updating the Bard.

This burlesque further addresses its contemporary audience by setting numerous monologues and dialogues to popular melodies. To be more precise, the play consists almost exclusively of songs.Footnote 28 Music was central to burlesque entertainments, a response to the 1737 Licensing Act, which limited spoken drama to the patent houses (Drury Lane and Covent Garden) and obliged other theatres to rely on music to escape prosecution. Nevertheless, the presence of as many as twenty-seven airs in this 1823 piece is surprising: by comparison, Poole's Hamlet Travestie contains only sixteen songs. In King Richard III. Travestie, the scene depicting Richard's wooing of Lady Anne incorporates four airs. The woman sings to the tune of “Go, George, I Can't Endure You” and “Oh Miss Bailey”; Richard to the tune of “Since Kathleen Has Prov'd So Untrue,” and, finally, Anne's yielding (through drinking) is presented in a duet to the tune of “Nancy Dawson”:

Glo'ster: We'll have blue ruin, if you'll go,

To All-max in the east, O.

But if blue ruin you refuse,

For yourself you must begin to choose,

Most ladies comfort drams do use,

But, don't make yourself a beast O.

Lady A.: Your choice I like—we'll have quarterns two,

I'll drink untill I'm blind –

Glo'ster: So do,

Both: We'll drink away till all is blue,

Glo'ster: And I will be your flash chap!Footnote 29 (16–17)

Following these exchanges, the couple dances off to the tune of “Off She Goes,” the jig cited in the opening soliloquy. The song references London low life, since All Max was a pub in the East End (Fig. 2). The shift from high to low is rendered more evident here by the circumstance that the name All Max itself was a parody of the exclusive Almack's Assembly Rooms, a famous West End club and one of a limited number of upper-class mixed-sex public social venues in the capital.Footnote 30

Figure 2. London low life: All Max in the East. I. R. & G. Cruikshank, hand-colored etching and aquatint, 1 May 1821. © The British Library Board 838.i.2, plate opposite p. 286.

Charles Selby's Kinge Richard ye Third (1844)

In February 1844 not one but two Richard III burlesques were produced in West End theatres. Both targeted what George Bernard Shaw named “bardolatry,” that is, the worshipful cult of Shakespeare, which originated in the mid-eighteenth century and, on the Victorian legitimate stage, gave rise to elaborate, reverential productions, obsessed with historical accuracy and packed with antiquarian reconstructions, as well as to sombre, bombastic, overweening recitation.Footnote 31 Solemnity inspired satire, and the two 1844 burlesques with their ample metatheatrical allusions were a direct response to the spectacular performances staged by Charles Kean at Drury Lane in January. Of the two, I have chosen to analyze the second, more successful, production, as it perfectly illustrates the Shakespeare burlesque at its height: Charles Selby's Kinge Richard ye Third; or, Ye Battel of Bosworth Field: Being a familiar alteration of the celebrated history . . . , called Ye True Tragedie of King Richard ye Third.Footnote 32

Whereas the other 1844 burlesque, Joseph Sterling Coyne's Richard III. A Burlesque. In One Act, ran for one month at the Adelphi Theatre and counted twenty-three performances,Footnote 33 Selby's travesty had at least sixty performances in the Strand. As the reviewer of The Times testified, Hammond, the actor who played Richard, “made a great deal of laugh in the fight at the end by an imitation of Charles Kean. Wigan, as Henry VI, was also capital, imitating Macready very effectively, and singing his parodies in a very amusing fashion.”Footnote 34 Given the notorious rivalry between Kean and Macready, the scene where Richard tries to murder Henry must have been rendered particularly amusing by Hammond and Wigan's caricatures. In fact, Selby's travesty was so popular that it was performed concurrently at the Royal Pavilion Theatre, a unique phenomenon in the nineteenth century, and also found success in several productions in the United States.Footnote 35 The play's American production makes sense when we consider that Cibber's King Richard III was itself the most popular play on the American stage.Footnote 36 As Lawrence Levine has argued, “while [Cibber's] work was done in the England of 1700, it could have been written a hundred years later in the United States, so closely did it agree with American sensibilities concerning the centrality of the individual, the dichotomy between good and evil, and the importance of personal responsibility.”Footnote 37

To facilitate the mise-en-scène, the print edition of Selby's burlesque specified the “Time of Representation”: one hour, fifteen minutes.Footnote 38 This highly spectacular travesty included a “Gigantic Equestrian Pageant” (sc. 8) that burlesqued the shows at Astley's Amphitheatre and spoofed the equestrian scenes in the Drury Lane production of the tragedy.Footnote 39 In the burlesque, the main male characters “gallop rapidly round the stage,” then:

Richard [enters] on horseback, followed by Soldiers, &c.—as Richard enters, all shout—he gallops round the stage a la Ducrow, makes his horse curvette, &c. When Richard enters, Catesby and Stanley back off. Trumpet sounds—the whole scene is kept in motion by the Knights, Squires, Pages, Heralds, &c., running off and on, bringing and carrying messages. Enter Catesby, at full gallop, bawling ‘Way, way, way!’, his horse is very restive.Footnote 40 (243–4)

In keeping with the form, the play is in rhymed couplets, and “contains so many songs, . . . that it virtually becomes a burletta.”Footnote 41 Although the ban on the production of scripted drama at the nonpatent houses had been lifted the previous year through the Theatre Regulation Act, music had become a defining feature of burlesque productions. There are fifteen songs in Selby's burlesque, and the anonymous reviewer of the Illustrated London News reported that the “absurdities” of the “many parodies of favourite songs from those of the older melodists to Balfe's last new ballads . . . kept the audience in excellent humour.”Footnote 42 There are several operatic allusions too. Dancing, which was increasingly becoming an integral part of these entertainments, is likewise present, as are choruses and what is called a “concerted piece” (238), with four voices and a chorus.

The text includes a ludicrous imitation of Charles Kean, parodying Cibber's spider simile to re-create the actor's stagy exaggerations and distinctive “snarl”: “Oh, Bucky, there are two daddy long legs / Crr-aw-ling in my path . . . / Unless some kind friend will upon them trr-ead, / They'll crr-awl, and crr-awl, till they scrr-atch me out of bed” (240).Footnote 43 Kean is also ridiculed later in the play, when, just before Lady Anne's entrance in the wooing scene, Richard “retires, and stands leaning against the wing” (222). This passage refers to a piece of stage business that Edmund Kean had introduced thirty years earlier, which William Hazlitt had much appreciated: “Mr. Kean's attitude in leaning against the side of the stage before he comes forward in this scene, was one of the most graceful and striking we remember to have seen. It would have done for Titian to paint.”Footnote 44 However, what Hazlitt had saluted as a novelty at the time of Edmund Kean's debut had evidently become a mannerism with the younger Kean, as we learn from the critic of The Era, who lamented that he “indulged in his favourite trick of hanging to the side scenes till the effect became almost ludicrous.”Footnote 45

Although Selby's play was based on Cibber's adaptation, it also restored some Shakespeare insofar as it showed both Richard's and Richmond's tents onstage on the eve of the battle, and the ghosts appeared to both contenders. In the print edition, the “Telescopic View of ye Argument & Scenery” highlighted the change, describing the scene as “grand Shaksperian restoration” (211). In this way, Shakespeare burlesques strove to reestablish Shakespeare's authority in a culture where rampant and multivalent adaptation dominated. The playbill for Selby's production makes clear how the burlesque critiqued Cibber's “improved” version:

The text is, of course, improved by copious alterations, additions and omissions. Many of the original passages by the Gentleman from Stratford, although no doubt abounding in beauties, being beyond the comprehension of the Adaptor, he naturally supposes (like Colley Cibber) that the Public must be as ignorant as himself, and will prefer the Drama of Effect to the Drama of Literature.Footnote 46

Indeed, the Shakespeare versus Cibber debate had gained momentum with Charles Kean's production, a revival of Cibber's version announced in the playbills as “Shakespeare's Historical play.” Several theatre reviewers criticized Drury Lane's choice, bearing witness to an increasing desire to see Shakespeare's plays performed in their original, unadulterated form.Footnote 47 The querelle was also satirized in an “Operatic Sketch” entitled “Cibber Detected,” which appeared in Punch. In it, a “Judicious Individual” declared:

Echoing this sentiment, Selby's burlesque spoofed Cibber's most famous interpolated line—“Off with his head. So much for Buckingham”Footnote 49—in the following parodic exchange, in which Richard is preempted from speaking his cue:

Catesby: My liege, the Duke of Buckingham is taken,

And we've cut his head off!

Richard: That saves his bacon!

Had he been ta'en alive and hither led,

It was my intention to have said,

“Off with his head—So much for Buckingham!”

I'm glad my friends have so much pluck in ’em. (246)

The play opens, like Cibber's, with King Henry in the Tower, and the protagonist's famous soliloquy becomes a part text, part song piece, recited by a Richard who enters “dancing joyfully, to the air of the ‘College Hornpipe’” (218). This time, humor prevails over nonsense:

Richard: Fol de riddle lol—fol de riddle lol!

Now is the winter of our discontent

(Like a poor author when he's paid his rent,

And at the baker's wiped a lengthy chalk)

Made glorious summer by the sun of York,

And all the clouds that on us look'd so dark,

Buried at Quillebœuf with the Telemaque. . . .

I am not such an addlepated pump

To think that I can amputate my hump,

Or straight my leg, or pass for Count d'Orsay!

No, these awkward superfluities sway

My fate—spite o’ my teeth, the world will spy them

And dogs bow wow me as I halt by them.

SONG

AIR—“Bow wow wow”

As I pass'd down Bond Street, t'other day,

The jest of all beholders –

I heard the girls in whispers say,

Lawk, what eccentric shoulders!

And as I crossed through Langham Place,

A lady's lap-dog spied me,

And at my heels in rage gave chace,

While a poodle puppy guyed me

Bow wow wow, &c.

I can't go hunting, lest the pack

Should flare up, and affront me,

For every whelp that sees my back,

Would leave the fox to hunt me.

In short, I'm so well known around,

That every cur that meets me

Of catsmeat makes me stand a pound,

Or a canine chorus greets me. (218–19)

Unsurprisingly, this passage features localization (fashionable places of London are mentioned, and we even find interjections in Cockney dialect), domestication (the dogs in the original play become “a lady's lap-dog”), and a topical allusion to the Télémaque, a French ship that, as the legend reported, was wrecked with a treasure at Quillebeuf, in Normandy, in 1790.

The play also makes effective use of simile to draw closer to the everyday experience of the audience. The following lines, taken from the wooing scene (sc. 4), illustrate the stylistic hybridity typical of these burlesques. Here, the numerous prosaic details of ordinary life blatantly clash with Richard's avowed intention of eulogizing Lady Anne's “fatal beauty”:

Richard: Thy beauty (like Battersean billows,

Which market barges smash to shivereens,

And cheat the town of sparrow grass and greens)

Thy fatal beauty, for whose dear sake,

Of all the world I'd Epping sausage make! (225)

Familiar similes and metaphors were an important formal feature of theatrical burlesques and one of their main sources of amusement. In this play, it is Richard who makes extensive use of such device, in expressions like the following: “I'll hang ’em like onions, all of a row” (244) and “[it] Made my heart like custard pudding shaky, / And my head like Etna when it's quaky!” (249). This last simile is, again, topical, referring to the violent eruption of Mount Etna on 17 November 1843, which had been preceded by a series of earthquakes.

Connected with the transformation of dramatic genre and the transposition from high to low is King Henry's ruse, which turns tragedy into comedy. He is stabbed in the Tower, but then reveals to the audience that his death was simulated (thanks to a pewter plate that he has hidden under his dressing gown) and he is planning to flee to France:

(. . . as soon as Richard is off, King Henry sits up, and looks cautiously around him.)

Henry: So, so, Duke Humpy, you think you've floored me,

Thank my coat—(Opening dressing gown, and

showing a pewter plate.)—you haven't even scored me.

Your winning ways won't frizz, you artful dodger,

Harry's a wide awake and tough old codger,

And won't pack off just yet—no, Dicky, no!

Spite of his death, he'll live to lay you low.

First I'll be buried, then my corpus bone,

And bolt to France per City of Boulogne. (221)

The usual debasement of Shakespeare's language is found in the extensive use of colloquialisms (“artful dodger,” “old codger,” “pack off”) and nicknames (“Duke Humpy” and “Dicky”), which undoubtedly conferred the piece an arresting immediacy at the time it was staged. At the end of the play, however, the still living King Henry rather incoherently returns with the ghosts for the closing tableau, snatching the crown from Richmond to put it on his own head, “over his night cap” (254).Footnote 50

In the following scene (sc. 4), we find an analogous descent into familiarity when Lady Anne's dead husband is called “Prince Ned, her hubby” and King Edward, again, “Neddy” (222). Later on, the Queen refers to herself as “The wretched Lizzy” (236). After the marriage, Lady Anne becomes the traditional shrew (Richard calls her “my vixen wife”) who “does nought but scold and fret” her husband, and complains that Richard, “Instead of coming home to sup and sleep, / All night in cellars and coal holes he'll keep, / Smoking and singing Barcarolles till day” (234). The references to Bohemian culture and its drinking establishments, common in burlesques of the Victorian period, are self-evident. Familiarities and colloquialisms proliferate in the humorous exchange between Richard and the young Princes. A few lines will suffice to show the tenor of the conversation:

Edward: How are you, Dicky? Tip us your fist, old fellow!

York: Right as a brick! (Seeing Richard—slapping him on the back.)

What? old Punchinello! . . .

Richard: (Aside.)—Oh, you dear, pretty—merry—downy—chick!

’Tis pity you'll so soon the bucket kick! (230–1)

Topical allusions are also numerous. For example, in the dialogue between King Henry and Richard that precedes the (attempted) assassination of the old King, Richard is compared to the eighteenth century's most notorious robber and thief: “Blackguard, thief, and vile presumer! / Oh, thou wert born to rob and slay, / And like Jack Shepherd, fake away” (220).Footnote 51 The historical Jack Sheppard was arrested several times and spectacularly escaped from various prisons, including Newgate, until he was hanged at Tyburn in 1724. Daniel Defoe was so fascinated by Sheppard's daring escapes that he wrote his biography, The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard. John Gay was similarly fascinated with the man, who served as the inspiration for the character of Macheath in The Beggar's Opera. Gay's ballad opera fed precisely on the contemporary avid public interest in the underworld, which was fostered by the detailed reports of criminal exploits in London newspapers and the many “biographies” and “memoirs” of the most notorious lawbreakers. By 1844, Sheppard's popularity had been revived by William Harrison Ainsworth's serialized novel, Jack Sheppard: A Romance, published in Bentley's Miscellany from January 1839 with illustrations by George Cruikshank.Footnote 52 Topicality, of which we have already seen many instances, was thus one of the chief means through which burlesque Shakespeare “embraced its own provisionality”Footnote 53 and made the Bard contemporary again.

Word games and puns abound in this travesty, with puns italicized in the text. The following extract from the wooing scene (sc. 4) plays on the homophony between “bier” and “beer”:

Richard: (Calling off)—Villains! set down that bier, and draw it mild,

Or by Barclay and Perkins, Bass and Childe,

To India ale I'll turn your mongrel blood,

And lay you sprawling in your native mud. (224)

Later, Lady Anne threatens Richard playing on the similar sounds of “far” and “fur”: “Aggravating villain! Don't go too fur, sir; / Though you're a Bengal tiger I'm your match! / My nails are long—you know that they can scratch!” (235). On another occasion the playwright took advantage of material already present in the originals. In both Shakespeare and Cibber, the Duke of Norfolk (whose Christian name is John) finds a piece of paper in his tent just before the battle, wherein the contraction of the diminutive “Johnkin” is used in the famous sentence “Jockey of Norfolk be not too bold, / For Dickon thy Master is bought and sold.”Footnote 54 In the burlesque, the character, rather predictably, becomes an actual jockey and is described in the dramatis personae as “a sporting Gentleman, well known on the Turf” (210). He wears a “Jockey's dress complete” (212), and the entire exchange between Richard and Norfolk in scene 10 is built around the horse-racing metaphor:

Richard: Well, Norfolk, think you we shall win the race?

Norfolk: Why, you see, guv'ner, if yer can go the pace,

And your jockeys don't come the cross, you will. But

I've had the office, there's a plant afoot

To put you in the hole—just read that ere,

And see if it arn't likely you'll be nowhere! (Gives paper.)

Richard: (Reading.)—“Jockey of Norfolk, be not too cheeky—

For yer chance o’ winning's very squeaky!

There is such things as jockeys being bought,

And coming dodges as they didn't ought—

Therefore, I say, don't cut it quite so fat,

For you, and yer cause, it's all round my hat,”

A weak invention of the opposition! (250–1)

The use of regional dialects is another important aspect of localization. Norfolk speaks “With a Yorkshire dialect” (250) and, as was typical of burlesques, begins with an exclamation that contains an obvious localization: “Look sharp, my lord, the foe's at Tattenham Corner!” (250). In Coyne's travesty of Richard III, the character had similarly been presented as “the oldest Jockey on record,”Footnote 55 and this was to be a long-lasting association. In the 1850s, in one of the six Shakespearean cartoons cumulatively labeled “New Readings for Unconventional Tragedians,” Norfolk was again depicted as a jockey presenting Richard with a copy of the contemporary sporting journal Bell's Life.Footnote 56

In addition to dialect, costumes served to bring a contemporary spin to Shakespeare. The costume descriptions in the print edition of Selby's play appear invariably extravagant and often symbolical. For example, a “moveable weather arrow with N.S.E.W., made of pasteboard and gold paper” (213) was fastened on the top of Lady Anne's head to spoof her mutability. Other anachronistic details point to the comic use of costumes and properties. For instance, King Edward was dressed in a “Short black velvet tunic, showing muslin trousers, flesh legs, white socks, and black shoes, large leghorn, or white beaver hat, with large rosette, and plume of white feathers, hair in ringlets to represent a child dressed in caricature of modern fashion” (212). Unsurprisingly, the reviewer of the Illustrated London News declared that “the costumes were a tissue of ludicrous anachronisms.”Footnote 57 In scene 4 the Footman was dressed in “an extravagant modern livery” and “carr[ied] an eccentric crimson umbrella” (223), whereas in the last scene, at the point when Richard dramatically asserted, “of one or both of us, the time is come,” Richmond, taking the metaphor literally, looked “at a large watch” (253). References to trains (249), cabs (241), and omnibuses (245) underscore the comic use of anachronistic details to meld Shakespeare and contemporary culture.

A similar alienating result was achieved with the introduction of “eccentric” dancing (249), “extravagant” action and attitudes (236, 240, 250, and 253), and, above all, the insertion of musical effects that stage directions frequently describe as dissonant: “discord in orchestra” (221 and 249), “discordant flourish” (229, 243, and 251), and “discord and flourish” (250). This, again, appears as a parody of the incidental musical effects that characterized the performance of the tragedy at the legitimate theatre, which critics deemed inappropriate or excessive. The critic of The Times, for instance, found that “the fiddling . . . between the acts was almost intolerable,” and declared that “with the marches and flourishes with which Richard III abound[ed], there [was] quite enough to make a bad performance in this respect a positive drawback.”Footnote 58

Selby's burlesque also ridiculed the presence of numerous extras in the Drury Lane production, which the press had likewise criticized: “the bustle and confusion of the supernumeraries was anything but conducive to the interest of the scene,”Footnote 59 stated the reviewer of Lloyd's Weekly London Newspaper. If the playbill for the Drury Lane performance advertised “Standard Bearers, Trumpeters, Cannoneers, Banner Bearers, Archers, Bellmen, French Troops, Poursuivants, Soldiers, Body Guard, Peasants, &c., &c.,” the list of the dramatis personae in the travesty included “Sheriffs and Aldermen, Standard Bearers, Trumpeters, Banner Bearers, Commoners, Archers, Bellmen, French Troops, Pursuivants, Soldiers, Body Guard, &c. &c.” (210). The “bustle and confusion of the supernumeraries” in the legitimate performance was parodied, in the burlesque, in the already mentioned “Gigantic Equestrian Pageant” (sc. 8), which was “kept in motion by the Knights, Squires, Pages, Heralds, &c., running off and on, bringing and carrying messages” (244).

Selby also took pains to mock the hyperrealism of the final battle scene. The newspapers recorded that the Drury Lane Richard and Richmond were “surrounded by the implements of war, slain horses, broken carriages, and the dead and the dying,”Footnote 60 and made reference to “the dying and the dead in heaps on the field, and bows and arrows of the slain scattered over the plain.”Footnote 61 This was echoed in the “Battle Tableau” that opened scene 13, where “Soldiers, Horses, Knights, &c., [are] discovered, lying dead, in extravagant melodramatic attitudes,” and “after a short pause they all rise, and fight off” (253). In this “very identical battel field!” (211), the burlesque Richard was killed in “an unapproachably terrific combat—after a variety of extravagant pantomime” (253) that, again, satirized the excesses of the final sword fight in its legitimate counterpart at Drury Lane. However, despite the protestations of King Henry, this burlesque Richard refused to stay dead, and, in a “Transatlantic Finale” (211) set to “Yankee Doodle,” apostrophized the audience and begged its favor. The closing scene of Selby's travesty shows how travesties, besides chastising, as Burnand claimed, the “misinterpretation of self-complacent mediocre actors” and the “extravagant realism” of legitimate theatrical productions, made fun of contemporary London culture in general. In this case, the target was the increasingly widespread influence of American culture.

Though it is tempting to decipher every burlesque pun or allusion used, doing so does not offer a key to understanding such plays. In fact, contemporary accounts demonstrate that many burlesque jokes eluded the audience when they were first put onstage. The Illustrated London News reported that in Selby's Kinge Richard ye Third “the jokes were so thick that the hearers had not time to reflect on the worth of one before the wit of another flashed forth.”Footnote 62 However, as the above analysis of costumes and properties, music, dancing, and dialect shows, the text was only one element in a highly complex theatrical entertainment that appealed to audiences in a number of different ways.

Francis Cowley Burnand's The Rise and Fall of Richard III (1868)

Whereas the first play I examined represented one of the earliest experiments in the genre and Selby's piece showed the dramatic form at its apogee, the last burlesque I have selected was produced when the fashion for burlesques was fading. Indeed, as Schoch records, “No new Shakespeare burlesque was performed for almost the entire 1860s.”Footnote 63 The Rise and Fall of Richard III; or, A New Front to an Old Dicky was written by Francis Cowley Burnand, who, like Selby, was a prolific dramatist who composed more than seventy comic plays. He was also the editor of Punch from 1880 to 1906 and the author of the above-quoted defence of the burlesque form.Footnote 64 The play was staged at the New Royalty Theatre on 24 September 1868 and was “the last major Shakespeare burlesque of the professional theatre.”Footnote 65

From the 1850s onward, the relationship between the burlesques and their source texts progressively slackened. For example, the plot of The Rise and Fall of Richard III departs in significant ways from both Shakespeare's original and Cibber's adaptation. As the critic of The Observer stated, the author had “not told the old story in a new way, but had, to a great extent, made a story of his own.”Footnote 66 When the action starts, not only King Henry but also King Edward is dead, and the visit of the Lord Mayor and the Aldermen immediately follows the wooing of Lady Anne. Then, in the second scene, Richmond, the Duchess, Richard, and Elizabeth (or ’Lisbeth, to her Grandmamma) are shown together at Lord Stanley's house, and both Richard and Richmond propose to the girl. The group meets again at a ball at Westminster Palace in scene 3. Then, in scene 4, the Duchess, Elizabeth, and the Lord Mayor are all present in Richard's camp, and, outside the King's tent, the young woman tells Richmond the various, naive tricks she has played on Richard to sabotage him. The Duchess and the Lord Mayor are even involved in the battle, and the combat itself, with its abundance of visual slapstick humor, is pantomimic and chaotically ludicrous:

Enter, l. 2 e., man with mace, and Recorder with sword, fighting. Man with sword victorious. Enter Duchess of York, r. 2 e., with Lord Mayor, fighting. Duchess takes mace from man falling r., hits Recorder with sword, floors the Lord Mayor. Lord Mayor down, mace down, Recorder down. Enter Catesby; he is just about to hit the Duchess when she turns, he runs, she pursues. Exit Duchess r. Enter l. Buckingham and Tyrrel fighting; then to them Stanley; the three fight. Buckingham is in the middle. They lunge and run each other through, as Buckingham steps back and runs them through again with his two swords. Enter Elizabeth l. They all bow politely and fall down in different attitudes. Exit Elizabeth r. triumphantly. Drums. Trumpets.Footnote 67

Tellingly, several critics noted the similarity between this piece and a pantomime. In 1844, the reviewer of The Times had already commented on the suitability of the tragedy of King Richard III for this kind of entertainment when he had declared that “the subject, being full of action, allowed all the practical fun of a pantomime, which not a little enhanced the success of it.”Footnote 68 In 1868, the commentator for Lloyd's Weekly London Newspaper stated more generally that, at the time, it had become “difficult . . . to draw the line between burlesque and pantomime,” adding that, “with the exception of one or two scenes from the Shakespeare–Cibber tragedy,” The Rise and Fall of Richard III could “properly be described as an extravagant pantomime opening into which several of the clown's scenes ha[d] been introduced.”Footnote 69 Notwithstanding the perplexities expressed by reviewers, who mainly objected to the extreme freedom with which the author had treated his models (both Shakespeare and Cibber), Burnand's travesty continued to attract audiences for four months.

Burnand greatly reduced the number of dramatis personae but introduced new, extravagant characters, including “the Recorder,” “the Mace,” and “Pages of History.” As was to become common in burlesques produced in the last quarter of the century, several roles (Richmond, Buckingham, Catesby, and the Duchess) were played en travestie.Footnote 70 The setting was unusual and absurd, with only five scenes, including “Old Holborn Valley, near the Bishop of Ely's Strawberry Gardens,” and “Lord Stanley's Residence in the Romantic Village of Seven Dials.” In the description of Lord Stanley's “suburban residence” (205) as “romantic,” we see both localization and irony at work, since, as Schoch points out, Seven Dials was “an area of St Giles’ parish in central London then notorious for squalor and homicide.”Footnote 71

Burnand also drew on other plays by Shakespeare in composing his burlesque, and on one occasion the operation is explicit and associated with a sarcastic remark on Cibber: “Richard. Of all men else I'd have avoided thee. / Richmond. Richard, that's from Macbeth, and I won't suffer / Such mal-quotations on your great Mac-duffer” (240). In a footnote, the author justified himself by referring to the adapter's way of proceeding: “Cibber selected any passages from other plays of Shakespeare, and fitted them in as best he could. So here” (240). Such an ironic thrust can be seen, again, as a way of reinstating Shakespeare's authority in a theatrical panorama dominated by (often-unacknowledged) adaptation.

Allusions to contemporary theatrical culture are present in this burlesque as well. On the title page, the play is described as “A Richardsonian burlesque”—a reference to the fair-booth showman John Richardson, who had died thirty years earlier, but whose reputation as a producer of brief, sensational melodramas continued to be alive, as the following lines suggest:

Richard: Don't talk to me of quiet acting, cant,

Give back to Richard Richardsonian rant.

Storm! Thunder! Lightning! Hailstone chorus! Rain!

Comets avaunt!!! Richard's himself again.

(Strikes the attitude. . . .)Footnote 72 (236)

These are not the only metatheatrical allusions: the last quoted line parodies Cibber's Richard's defiant exclamation after the nightmare (“Conscience ava[u]nt; Richard's himself again”)Footnote 73 and the actorial pose that regularly accompanied it.

The play similarly satirizes other famous lines from the source play, which offered good “points” to actors and on which the Richards of the time fought their battles. Cibber's already mentioned interpolation is evoked twice, and in both instances the lines are spoken out of turn.

Richard: Guards! Ho! Soldiers! Waiter!

“Off with his head so much”—(Corrects himself.)—no that comes later. (217)

On the second occasion, Stanley's sudden entrance makes Richard cut his chin while shaving, which jibes well with the unexpected decapitation order:

Richard: (Furiously.)—Off with his head, so much for Buckingham.

Elizabeth: He's not the Duke—

Richard: He's not, but he came in So suddenly, he made me cut my chin. (236)

Richard's last desperate cry becomes: “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a courser! / Well, I do get a little hoarse, and hoarser. / That's an old joke” (239). The comment “that's an old joke” highlights how many Richard III jokes had by the mid-nineteenth century become stale and overused. Burnand nevertheless continued to recycle such jokes, as the following tour de force return to Gloucester cheese puns suggests:

Richard: I see that you a passion for me foster.

Anne: Passion for you! High, mighty, double Gloster.

Richard: Oh, call me double Gloster, if you please,

As long as I, in your eyes, am the cheese.

Anne: A cheese! Why then I cut you.

(Going to r., he stops her.)

Richard (l.): I've the daring

To ask you to consider this cheese paring.

Anne: You are hump-backed.

Richard: Oh, hump-bug!

Anne: And knock knee'd.

Richard: A friend in-knee'd, maam, is a friend in deed. (200)

The legibility of these word games—for example, the puns on “paring” and “pairing,” and on “knee'd” and “need”—offer one reason for their staying power. Equally comprehensible is the metaphor “to be the cheese” (i.e., “to be the best or first rate”) and the wordplay on “cut,” which stands for both “to slice” and the slang word “to run away, make off” (OED).

In addition to recycling old jokes to great effect, Burnand's burlesque parodied climactic moments in performance such as the final sword fight between Richard and Richmond, as evidenced by the stage direction: “They fight the regular old stereotyped ‘Richard’ combat. Richard falls” (240). Metadramatic allusions are discernible in the following punning exchange, which unexpectedly references two editors of Shakespeare:

Richmond: Here's Bosworth.

Buckingham: You've dropped your accent, Sir, is that intended?

Richmond: Yes, all my broken English I have mended.

Buckingham: (Making a slight mistake.)—Then where's Dr. Johnson?

Richmond: (Corrects him.)—Mule!

“Boswell,” said Dr. Johnson, “You're a fool,”

Buckingham: (Puzzled.)—Then what is Bosworth?

Richmond: What he is and was worth,

We know: now ask the Yankees what is Boz worth. (226–7)

As the above quotation implies, speech effects became a source of comedy in this play, not through the use of dialect, but through the “broken English” (205) spoken by Richmond, who “passed the best years of his life in Britanny [sic], and was more of a Frenchman than an Englishman” (194).

In keeping with the burlesque form, Burnand includes numerous topical references, as in the pun in which the Lord Mayor is assimilated to “a New Zealand Savage” because he is “a Maorie Chief” (202). Or, again, in the scene where the group formed by Richmond, Elizabeth, Richard, the Duchess, and Anne takes up the suggestion of Richmond, who sustains that the Cancan is “a little thing from France” that “belongs to France and England too” (221), and performs a “grand dance and chorus” (222) on the notes of L’Œil Crevé, an opéra bouffe by Hervé that had been produced the previous year: again, “Shakespeare” is made contemporary. The weird show appears as a veritable hymn to the Cancan:

The performance degenerates in a “wild dance, in which Richmond, Richard, Elizabeth, Anne and Duchess take prominent parts” (223). In this scene, the habitual reference to Bohemian culture is clearly perceivable, since at the time the Cancan was considered extremely inappropriate by respectable society.

Heavy drinking is another recurring topic, as the following passage in which Richard and his mother spend their time drinking shows:

Richard: You look untidy. (Examining Duchess's dress.)

Duchess: Don't repeat “untidy” when you see I've something neat.

(Producing flask.)

(Richard takes bottle, and drinks it off.)

Duchess: (Aside.)—I can call spirits from the vasty deep,

My pocket, where my provender I keep.

(Opens deep pocket, taking out an orange, apple, thimble, &c.,

&c., then a large case bottle and glass, which she fills.)

. . .

Richard: How easily it trickles down my throttle. (Drinks violently.)

Duchess: He, as a child, took early to the bottle,

As all our family were and my relations;

I can look back on several ginny-rations.

Yes, and my ancestors, they never fought

With greater spirit than at A-gin-court.

(During this Richard has been drinking; . . .) (231–2)

In the Duchess's “aside” we find a line taken from Henry IV, Part 1—another instance of the author parodying what Cibber (and other Shakespeare adapters) had done, namely, “select[ing] any passages from other plays of Shakespeare, and fitt[ing] them in as best [one] could” (240).

Yet in spite of some topicalities, Burnand's burlesque draws its humor from puns, word games, and comic routines. Two of the most amusing gags involve Tyrrel. The first one takes place when the character is presented:

Richard: . . . He speaks in monosyllables alone,

And always gives ’em in a deep bass tone.

Beyond a yes or no he'll seldom go.

How are you, Tyrrel?

Tyrrel: (Scowling.)—Yes.

Buckingham: (Crossing to shake hands with him.)—How are you?

Tyrrel: (Looks at his glove, then removes it, blows into glove.

Trombone.)—No. (Shakes hands.) (197)

Burnand introduced anachronisms and incongruities to render the situations funnier, and the play more entertaining: in the wooing scene, Anne threatens Richard with a parasol (201); Richmond smokes cigarettes (206); Stanley enters carrying coats and umbrellas (209); in scene 3, Elizabeth and Richmond go to the ball wearing Tyrolean dress (219) and, with the Duchess and Richard, sing to the tune of Offenbach's “[Valse] Tyrolienne” (220); later on, Elizabeth participates to the battle “dressed after the manner of Joan of Arc” (234). In this burlesque too, the songs were numerous and varied, and they were set either to contemporary airs or to operatic tunes. On some occasions, the publisher of the original song was noted (see 204, 212, 216, 225, and 229). Dancing was, again, prominent.

As customary, the dead came back to life in the finale. The Duchess delightedly announces: “here's Anne, who wasn't killed by my bad son,” and Anne continues the sentence with a pun: “But is as much alive as Annie one” (241). Immediately after, at Richmond's triumphant assertion “There Richard lays,” Richard instantly resuscitates and defiantly exclaims, using, again, a pun: “To order, sir, I rise. / Who says ‘he lays’ grammatically lies” (241). Then, in the final song (to the tune of “Naughty Mary Anne”)—in line with the concepts that Burnand would expound two decades later in his essay “The Spirit of Burlesque,” where he would declare that the office of burlesque is “to expose, ridicule and satirise dramatic pedantry and theatrical pretension,”Footnote 75—Elizabeth asserts that the play (aptly subtitled A New Front to an Old Dicky) has “amended” Richard's story:

To conclude this essay, it could be appropriate to recall the Bakhtinian idea of parody as a hybrid of multiple registers and languages. Hybridity characterized nineteenth-century theatrical culture at large, which witnessed an astonishing proliferation and cross-fertilization of dramatic genres, and an equally striking experimentation within traditional generic modes. The stage was dominated by a combination of high and low, legitimate and illegitimate, elite and popular, past and present. In hybridity lies the key to the popularity and success of the burlesque form and of Shakespeare travesties in particular. As David Francis Taylor has put it: “Burlesque operates in, and wilfully collapses, the disjunction between the registers of Shakespearean drama and of the modern everyday.”Footnote 76

However, nineteenth-century Shakespearean parodies were not intended as attacks on Shakespeare; rather, their targets were the follies of the pseudo-Shakespeareanism of the contemporary age, and the misrepresentations it entailed. Burnand's statement on the subject finds an echo in the exchange between the characters of “Burlesque” and “Tragedy” in James Robinson Planché's 1853 extravaganza The Camp at the Olympic:

With all their absurdity, nonsense, and eccentricities, nineteenth-century Shakespeare burlesques purported to be the defenders of good sense and good theatre. More important, they saw themselves as the restorers of the Bard's status, imperiled, at the time, by extravagant productions and what had increasingly come to be regarded as “mangled” dramatic adaptations.

Nicoletta Caputo teaches English Literature at the University of Pisa. She has published articles and a volume on Tudor drama; essays on Shakespeare, on nineteenth-century stage history, and on contemporary English theatre and fiction, as well as a monograph on Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus. Her most recent book is Richard III as a Romantic Icon: Textual, Cultural and Theatrical Appropriations (Peter Lang, 2018).