Introduction

Clinical perspective

What is guilt?

Feelings of guilt in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are often characterised by a belief that one should have thought, felt, or acted differently during a traumatic event. Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Scragg and Turner2001) describe guilt as a self-conscious emotion that relates to a sense of responsibility for being the cause of harm to self/others or failing to prevent harm to self/others. The person often thinks that some or all of what happened during the traumatic event was within their control. In cases where the person acted (or did not act) in a way that is at odds with their moral/ethical values, the feeling of guilt may be encapsulated in the concept of ‘moral injury’ (Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009; Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021). Guilt and shame significantly overlap in definition (Blum, Reference Blum2008) and frequently co-occur, with most researchers indicating that a more global judgement of oneself is the marker of shame. Feelings of guilt can be helpful, if for example an event was someone’s fault and it prompts them to apologise or to make amends for a mistake (Baumeister et al., Reference Baumeister, Stillwell and Heatherton1994; Tangney et al., Reference Tangney, Stuewig and Mashek2007). However, many people feel guilty for something that to others appears not to be their fault, which occurs frequently in trauma survivors (Pugh et al., Reference Pugh, Taylor and Berry2015). In this paper we focus on guilt in relation to a trauma survivor’s judgement of their behaviour during an event.

Why do people feel guilty?

It is common for people to blame themselves for what occurred during a traumatic event. In our clinical experience, after fear, guilt and shame are the most frequent peri-traumatic and post-traumatic emotional responses. There are a number of routes to feeling guilty/responsible for an event and each reason may require a slightly different intervention from the therapist. Kubany and Watson (Reference Kubany and Watson2003) propose that the magnitude of affective guilt someone will feel is linked to four underlying cognitions: (i) perceived responsibility for the negative outcome, (ii) perceived insufficient justification for actions taken, (iii) perceived violation of values, and (iv) beliefs about foreseeability and preventability of the negative outcome. This model of guilt has formed the basis of intervention for combat veterans (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Wilkins, Myers and Allard2014) and for women who have suffered physical and sexual violence (Kubany et al., Reference Kubany, Hill, Owens, Iannce-Spencer, McCaig, Tremayne and Williams2004). We have also found this conceptualisation of guilt informative in our work with asylum seekers and refugees who have survived a range of traumatic experiences.

We have summarised below the five routes to responsibility that we have observed in our clinical work, based in part on those proposed by Kubany and Watson (Reference Kubany and Watson2003):

-

(1) The trauma survivor is over-estimating their personal responsibility for the traumatic event and under-estimating the responsibility of others.

-

(2) ‘Hindsight bias’ (Fischhoff, Reference Fischhoff1975) – the trauma survivor thinks that they should have known something, or did know something, that might have led them to act differently had they paid more attention to it.

-

(3) The trauma survivor blames themself for ‘choosing’ an outcome with negative consequences, even though they faced impossible choices during the traumatic event.

-

(4) The trauma survivor minimises the impact of their own shock/terror symptoms on their behaviour during the event and so blames themselves for the outcome.

-

(5) The trauma survivor has gaps in their memory of the traumatic event, so assumes that they are responsible for what happened (or do not remember what they did that was helpful.)

We do not know why trauma survivors so often hold themselves responsible for events. There are several theories we are guided by most in our work, which may not be mutually exclusive. First, it may be that guilt arises in an often-subconscious effort from trauma survivors to understand what they have been through, and possibly what their experiences mean for their future. Trauma can shatter previously positive beliefs about the self, world, and others (or reinforce previously negative ones). This is a truly terrifying experience – leaving a survivor struggling with unfamiliar (or all too familiar) notions of uncertainty, unpredictability, and uncontrollable injustice in the world. Understandably, the trauma survivor may look for a meaning that makes the world feel more controllable, predictable and just – so that their previous view of their world is not breached. For example, they might believe that the negative outcome would not have occurred if they ‘had just’ acted differently, giving rise to self-blame and guilt. We do not suggest that people necessarily make this choice consciously, but that perhaps paradoxically, self-blame and guilt can be viewed as an attempt to be in control of what might otherwise feel like an unpredictable world (Herman, Reference Herman1992; Raz et al., Reference Raz, Shadach and Levy2018; Schmideberg, Reference Schmideberg1956). By holding themselves responsible for a bad event, survivors can hold onto the notion of a safe and just world and, hopefully, ensure that it does not happen again in the future, because they can stop its recurrence. Unfortunately, it is this very attempt to reduce distress via self-blame and a sense of control that is linked to increased PTSD symptoms and the associated sense of being unsafe (Raz et al., Reference Raz, Shadach and Levy2018). A similar process has been hypothesised to explain the common tendency of children who are being abused to blame themselves, thereby maintaining their attachment to an abusive caregiver (Ainscough and Toon, Reference Ainscough and Toon2018).

Similarly, Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Scragg and Turner2001) suggest in their model of guilt-based PTSD, that a survivor may experience chronic guilt and PTSD if they experience guilt cognitions peri-traumatically or post-traumatically that are congruent with a pre-existing global negative schema of themselves as ‘to blame’. In this instance, guilty trauma-based feelings may be attributed as something deserved, rather than something arising as a result of the circumstances of the traumatic event.

Finally, it could be argued that guilt is an evolutionarily adaptive prosocial emotion; if we feel guilty about wrongdoing, it will motivate us to make reparations. In so doing, we may repair some of the damage done and make for a more harmonious social group.

Why intervene to help with guilt?

Guilt does not always play a disruptive role and should be considered within its cultural and social context. In our clinical experience, feelings of guilt are often part of the process of grieving and do not necessarily merit a therapeutic intervention. Similarly, for some, feeling guilty may form part of a penance and lead to a resolution of internal conflict. Kubany and Watson (Reference Kubany and Watson2003) suggest that a natural process of guilt reduction occurs as a person thinks over the event and faulty assumptions are updated and opportunities for reparation are taken.

However, when the guilt causes such severe distress that it leads to avoidance of the memory, this process is interrupted, and it may become the role of a professional to support a trauma survivor in facing the memory and addressing the guilt. For example, therapeutic intervention may be necessary if feelings of guilt are exacerbating PTSD symptoms or other presenting difficulties, such as depression (Browne et al., Reference Browne, Trim, Myers and Norman2015), pain (Herbert et al., Reference Herbert, Malaktaris, Lyons and Norman2020), sleep disturbance (Dedert et al., Reference Dedert, Dennis, Cunningham, Ulmer, Calhoun and Kimbrel2019), poor functioning (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Haller, Kim, Allard, Porter, Stein and Rauch2018), or suicidality (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud2013). Left unattended to, guilt may generalise into a global negative self-evaluation, causing feelings of shame (Kubany and Watson, Reference Kubany and Watson2003).

We certainly know that peri-traumatic and post-traumatic guilt cognitions can make PTSD symptoms worse (Browne et al., Reference Browne, Trim, Myers and Norman2015) and that trauma-related guilt can be so distressing that it mediates the link between PTSD and suicidality (Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Farmer, LoSavio, Dennis, Clancy and Hertzberg2017; Tripp and McDevitt-Murphy, Reference Tripp and McDevitt-Murphy2017). Indeed, guilt has been associated with PTSD in a range of populations (Pugh et al., Reference Pugh, Taylor and Berry2015), including refugees (Stotz et al., Reference Stotz, Elbert, Müller and Schauer2015), veterans (Dedert et al., Reference Dedert, Dennis, Cunningham, Ulmer, Calhoun and Kimbrel2019; Henning and Frueh, Reference Henning and Frueh1997; Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009), and survivors of domestic violence (Beck et al., Reference Beck, McNiff, Clapp, Olsen, Avery and Hagewood2011; Street et al., Reference Street, Gibson and Holohan2005). In addition, Browne et al. (Reference Browne, Evangeli and Greenberg2012) found that guilt mediated the link between work-related trauma exposure and PTSD in a group of journalists. The current COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in many healthcare workers and carers having to make challenging and emotional decisions, which may later lead them to feel guilt and/or ‘moral injury’ (Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021; Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Murphy and Greenberg2020). It is known to cause distress following a range of traumatic events, such as childhood abuse, sexual assault, serious accidents, combat, and traumatic bereavement (Kubany and Watson, Reference Kubany and Watson2003).

If survivors experience strong feelings of guilt when they think about a traumatic event, because guilt is such an uncomfortable emotion, they may avoid thinking in detail about the traumatic event. Street et al. (Reference Street, Gibson and Holohan2005) found this in a group of survivors of interpersonal violence and Held et al. (Reference Held, Owens, Schumm, Chard and Hansel2011) in a group of combat veterans. In some instances of traumatic guilt, a survivor may ruminate about an event rather than avoid it (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Scragg and Turner2001). Nevertheless, in our clinical experience, this tends to be focused on self-questioning and judgement and not on the emotional engagement required to process the memory of an event. This can strengthen unhelpful appraisals, prevent the traumatic memory from being processed, and fuel negative affect (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Moulds et al., Reference Moulds, Bisby, Wild and Bryant2020). Avoidance of thinking thoroughly about a traumatic event can therefore precipitate or maintain PTSD.

Interventions to ameliorate guilt

In terms of how effective we are in reducing guilt, some outcome research indicates that guilt will reduce as a matter of course during a trauma-focused therapy (Resick et al., Reference Resick, Galovski, Uhlmansiek, Scher, Clum and Young-Xu2008; Stapleton et al., Reference Stapleton, Taylor and Asmundson2006). Other studies have found that if not targeted, guilt will not reduce sufficiently, and so guilt should be a treatment target in its own right (Foa and Meadows, Reference Foa and Meadows1997; Hendin and Haas, Reference Hendin and Haas1991; Kubany and Watson, Reference Kubany and Watson2003; Resick et al., Reference Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin and Feuer2002). In our clinical experience, particularly with more complex presentations, the guilt often needs to be targeted separately.

Fortunately, a range of ideas have been suggested to target trauma-related guilt: restructuring of any erroneous cognitions underlying the guilt (Kubany, Reference Kubany1994; Kubany, Reference Kubany1997; Kubany et al., Reference Kubany, Hill, Owens, Iannce-Spencer, McCaig, Tremayne and Williams2004; Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021), combining this cognitive work with a values focus (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Wilkins, Myers and Allard2014), imagery rescripting (Alliger-Horn et al., Reference Alliger-Horn, Zimmermann and Schmucker2016; Arntz et al., Reference Arntz, Tiesema and Kindt2007; Grunert et al., Reference Grunert, Weis, Smucker and Christianson2007), and the development of self-compassion (Held and Owens, Reference Held and Owens2015; Held et al., Reference Held, Owens, Thomas, White and Anderson2018). Kubany and Watson (Reference Kubany and Watson2003) also suggest that we may support survivors to tackle guilt by proactively making amends or via seeking forgiveness from self or other. Combat-specific treatments of ‘moral injury’, entitled ‘Adaptive Disclosure’ and ‘Impact of Killing’, have also been developed. These similarly target guilt via a more reparative approach and introduce the concept of self-forgiveness (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Schorr, Nash, Lebowitz, Amidon, Lansing and Litz2012; Litz et al, Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009; Steenkamp et al., Reference Steenkamp, Nash, Lebowitz and Litz2013).

All aforementioned studies have found a reduction in trauma-related guilt through these interventions. Unsurprisingly, given the role of guilt in maintaining psychopathology, including PTSD, these interventions have also been effective in reducing PTSD symptomatology (Allard et al., Reference Allard, Norman, Thorp, Browne and Stein2018; Arntz et al., Reference Arntz, Tiesema and Kindt2007; Kubany, Reference Kubany1997; Kubany et al., Reference Kubany, Hill, Owens, Iannce-Spencer, McCaig, Tremayne and Williams2004; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Wilkins, Myers and Allard2014; Winders et al., Reference Winders, Murphy, Looney and O’Reilly2020). Indeed, the role of intervening to reduce guilt has been found to be powerful. Allard et al. (Reference Allard, Norman, Thorp, Browne and Stein2018) found that mid-treatment reductions in guilt predicted reduction in PTSD symptoms post-treatment.

From theory to practice

In order to demonstrate the many facets that maintain guilt and how to intervene with each, we will use a fictional case example throughout the article. While the example discussed is of someone who has experienced sexual abuse as a child, the techniques mentioned will be equally applicable to others, such as healthcare workers and carers dealing with feelings of guilt resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. When ‘Isabella’ (now 52) was in her early teenage years, she was raped several times by a friend of her parents. She has never spoken to anyone about what happened, fearing that they would blame her. She experiences intrusive memories of the rapes several times a week and often has nightmares in which she is pinned down and attacked by a frightening man. She feels guilty about and responsible for what happened to her. Her experience of being raped has affected her later enjoyment of sexual relationships and she feels very wary of men.

In this article, we also provide links to some films demonstrating the techniques. These were made by the authors at home during lockdown, in one take. Thus, they are not flawless but represent a ‘good enough’ attempt to show the reader how to address guilt.

Assessment and formulation

The presence and severity of feelings of guilt can be assessed through standard clinical assessment. In the context of a PTSD diagnosis, the Trauma Related Guilt Inventory (TRGI) (Kubany et al., Reference Kubany, Haynes, Abueg, Manke, Brennan and Stahura1996) and the Post-Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI) (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin and Orsillo1999) can also be helpful. Additionally, the Moral Injury Symptom subscale can provide useful insights (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Ames, Youssef, Oliver, Volk, Teng and Pearce2018).

Furthermore, a person’s feelings of guilt can be affected by factors such as a pre-existing strong sense of responsibility, an unhelpful view of self, high standards for their own behaviour, and rigid beliefs about control over the environment. This is particularly the case if a negative global view of oneself is activated by guilt arising during or after a traumatic event (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Scragg and Turner2001). Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) Cognitive Model of PTSD addresses a client’s prior beliefs. These may affect their processing of a traumatic event and the level of guilt they feel both during and after it. For example, a client’s upbringing, religious beliefs, cultural context, and history of previous trauma may have a big influence on what is viewed as acceptable or unacceptable moral behaviour. These beliefs may even prevent a client from believing that they are not completely responsible for the event, despite the cognitive and imagery interventions discussed below. If this is the case it is important to spend time developing a shared understanding of what led to these beliefs and working on them directly before returning to consider the traumatic event (Stallworthy, Reference Stallworthy2009).

Therapeutic work with feelings of guilt

We have outlined below the steps that we suggest you take once you are ready to try and intervene with guilt. Please note, we have drawn ideas from many influential papers explaining how to intervene with trauma-related guilt and have used these in our clinical work with the population of traumatised refugees. We have particularly made use of the cognitive ideas outlined by Norman and colleagues (Reference Norman, Wilkins, Myers and Allard2014) in ‘Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy’, who in turn drew on the model of guilt outlined by Kubany and Watson (Reference Kubany and Watson2003). We have also drawn from the cognitive treatment approach outlined by Kubany and colleagues (Kubany, Reference Kubany1994; Kubany, Reference Kubany1997; Kubany et al., Reference Kubany, Hill, Owens, Iannce-Spencer, McCaig, Tremayne and Williams2004; Kubany and Ralston, Reference Kubany, Ralston, Follette and Ruzek2006).

In addition to the cognitive work already outlined extensively by others, we make recommendations on how to help move cognitive updates from the ‘head to the heart’ through the use of imagery updates. We also place these cognitive intervention strategies within the context of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (tf-CBT) and explain how to use cognitive updates to target peri-traumatic guilt.

The interventions we outline can occur at different points of the therapeutic process. For the purposes of this guide, we make the assumption that prior to these interventions, you will have already obtained informed consent to treatment from the client and developed a good enough therapeutic alliance to proceed. Most often these interventions will then follow some form of memory work (e.g. reliving) in which a detailed account of the trauma is developed. It may be that strong feelings of guilt are identified during this work. Alternatively, problematic guilt may be discovered and targeted later in the treatment process.

Step 1 – When did they first feel the guilt?

First, it is important to establish whether the guilt the client feels is (a) peri-traumatic or (b) post-traumatic. If the feelings of guilt developed after the traumatic event, the cognitive and imagery techniques discussed in this article may be enough to decrease the feelings of guilt. However, if the guilt was experienced during the traumatic event, then the information discussed during cognitive work may also later be used during reliving to ‘update’ the traumatic memory (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Grey et al., Reference Grey, Young and Holmes2002; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Scragg and Turner2001). It is often the case that until the new information has been integrated within the trauma memory, the client will continue to feel guilty, even if they rationally agree with the cognitive work (known as ‘head heart lag’ or ‘rational emotional dissociation’; Stott, Reference Stott2007). Prior to reliving and updating, the memory of a traumatic event remains ‘unprocessed’. This results in the client re-experiencing (through intrusive memories, nightmares and flashbacks) the moment that they initially felt guilty, with the full force of the guilt that they felt during the traumatic event. During the cognitive work, we aim only for the client to intellectually accept that they are less guilty/responsible than they thought they were (if that is the case). This intellectual argument can then be inserted into the traumatic memory at a later date; moving what they know now ‘from their head to their heart’. Nevertheless, the initial intervention for both peri-traumatic and post-traumatic guilt is the same, cognitive work. Occasionally the guilt is not truly peri-traumatic, but occurs soon after the event. Subsequent recollections of the event may then be infused with these post-traumatic thoughts and feelings. In these situations, the guilt will need targeting in the same way we outline for peri-traumatic guilt, and updated within the traumatic memory itself.

In order to establish whether guilt is peri-traumatic or post-traumatic, you simply need to ask, ‘When did you first start to feel like this, was it during the traumatic event or did it develop later, over time?’.

Step 2 – Permission for cognitive work

It is important to state that guilt is a very common feeling after a traumatic event. This can normalise and facilitate a discussion about guilt. Once a client feels able to discuss their feelings of guilt, it is then important to point out that trauma survivors tend to over-estimate how much responsibility they have for traumatic events. Further, that because of this, it might be worth them exploring their guilt with you.

For example, you could say, ‘It is very common following a traumatic event for people to feel guilty about and responsible for some or all of what happened. This could be guilt in relation to decisions they made, or how they acted, or what they did or did not do at the time of the traumatic event. While this is a very normal thing to feel after a traumatic event, in my experience people often tend to over-estimate their responsibility. I am not sure whether or not this is the case for you, but I think it is worth considering this possibility together, because feelings of guilt could be maintaining symptoms of PTSD and/or depression. Feelings of guilt may also lead you to avoid thinking about the traumatic event, which will contribute to PTSD symptoms being maintained. How would you feel about us exploring your feelings of guilt/responsibility together, to check that they are proportionate?’.

We think it is crucial to get the client’s permission to explore their feelings of guilt. If you do not, they might feel that you are invalidating their emotions. The client is very likely to have been feeling guilty since the traumatic event occurred and so it will be well established and be having a big impact on their lives currently. It is important to be genuinely inquisitive and curious during all discussions.

Step 3 – Statement of guilt/responsibility

Once the client has given permission to discuss their feelings of guilt, ensure that you have a very clear statement about what it is they feel guilty about and why. There is a big difference between statements Isabella might have made ‘I should not have decided to keep quiet, I should have told my parents after the first time he raped me’ and ‘I should not have decided to keep quiet, I should have told my parents after the first time he raped me, and because I did not say anything, I am responsible for him raping me again’. It is also useful to ask the client to rate how much they believe this statement to be true (0% = not at all true, 100% = completely true), allowing you to monitor any change. Once you have a very clear statement of what it is that the client is feeling guilty about/responsible for, then use one or more of the cognitive techniques in Step 4. In order to access and understand such a specific statement of perceived guilt/responsibility, this can often work better after someone has relived their trauma or shared a detailed narrative of their experience during therapy.

For a film demonstrating this stage of the process, see: https://bit.ly/CTPTSDGuilt1

These films were made unscripted by the authors at home during lockdown. Thus, they are not flawless but represent a ‘good enough’ attempt to show the reader how to address guilt. The tone is kept emotionally ‘light’ to demonstrate the techniques as clearly as possible.

Step 4 – Cognitive techniques

Responsibility pie charts and other similar techniques

Responsibility pie charts work best when a client blames themself for all (or at least a large percentage) of the traumatic event, e.g. Isabella might think, ‘It is all my fault that I was raped multiple times by my parents’ friend’. This technique can be helpful in distributing responsibility more fairly and helping the client to focus on all of the responsible people and factors, not just themselves. This can be done with a traditional drawn pie chart, but it often works better and is more memorable with things that can be moved around with someone’s hands. For example: a big bag of marbles, beads, modelling clay, counters, matches, dominoes, rice/lentils or anything else that would have the same effect.

Initially, have a brief open discussion with the client about what factors or people they think might be responsible for what happened during the traumatic event. Then, discuss for what percentage of the event they believe they are responsible. Next, ask the client to list every possible person they can think of who could share any responsibility at all for what happened (however small) and write these people/organisations down. Additionally, ask them to consider all of the circumstantial, cultural, developmental and societal factors that could have contributed. Ensure that you discuss with the client their developmental age at the time of the trauma and consider that younger children may be more likely to attribute the cause of any bad event to themselves. If the client says they cannot think of anyone other than themselves, then you can suggest people and factors.

Norman et al. (Reference Norman, Allard, Browne, Capone, Davis and Kubany2019) also encourage the therapist to give the client an example of how responsibility for one event is often distributed very widely. They suggest lining up a row of dominoes, which the therapist then knocks over by touching the first one. The therapist can then point to the last domino and ask the client what made the last domino fall over. They can have a discussion about the fact that, technically, the penultimate domino toppled the last domino. However, that domino was pushed over by the one before it and so on. Equally, the therapist lining up and then pushing over the first domino also had some role in the last domino falling. So too did the person who taught the therapist this demonstration technique, maybe even the person who trained the therapist in CBT, or even the teacher at school who encouraged them to study psychology. In our experience, using objects to demonstrate an idea makes the outcome of the discussion more memorable; our clients often remind themselves of the falling row of dominoes when they are feeling guilty.

For Isabella, others who share responsibility could be: ‘the man who raped me, my parents for not noticing I looked scared of him, his wife who may have known something was happening, government officials who did not educate children and adults about sexual abuse, teachers at school who did not ask why I was so distracted, my doctor who did not ask my questions about the urine infections I kept getting, cultural norms at the time that legitimised the sexualisation of teenage girls, cultural norms about consent at the time, me’. Consider as many people and factors as possible, including people who were responsible for decisions days, weeks and even years before the event and sociocultural/contextual factors that were present at any time before and during the event.

Once you have your list of responsible people and factors, place the objects that you have chosen (clay/matches/beads, etc.) in the centre of the table and explain that the objects represent all of the responsibility for the event occurring. Then ask the client to assign portions of the pile of objects (or a percentage if using a pie chart) to all the people and factors that might reasonably share some responsibility. It can be a powerful experience for the client to physically move the responsibility towards others and away from themselves. It is very important to make sure that the client assigns their own responsibility last. They will find that they have only part of the responsibility left by the end and this is likely to be a smaller amount than they had initially stated (see Fig. 1). Discuss the percentage they have assigned to themselves after the exercise and contrast this with the original percentage of responsibility they had assigned themselves.

Figure 1. Responsibility pie charts and other similar techniques.

Following this exercise, take a photo of each pile and label who/what each pile represents. Ask the client to look at the photos for homework and reflect further on what they have learnt. It is particularly helpful to look at the photos when the client starts to feel guilty and blame themself.

For a film demonstrating how to do a responsibility pie chart, see: https://bit.ly/CTPTSDGuilt2

Discussion regarding knowledge and blame

Kubany (Reference Kubany1994) outlined the importance of helping a person to realise when they are judging themselves unfairly, with the benefit of hindsight. Similarly, Norman et al. (Reference Norman, Allard, Browne, Capone, Davis and Kubany2019) suggest discussing with the client how we often claim to know that, for example, our football team was going to win, after they have won. This is a common tendency in humans to conflate the outcome with what we knew at the time. They point out that if we had really known for sure that our team would win, we would have bet our life savings on the game; we only think we knew for sure with the benefit of hindsight. In keeping with this, we recommend that when a client thinks that they should have known something at the time of the traumatic event, or should have paid more attention to something, a discussion regarding the relationship between knowledge and blame can be helpful.

First, ask the client what they think they should have known, or should have paid more attention to, at the time of the traumatic event (that could have prevented it from occurring). For example, Isabella might answer, ‘I should have known that if I had told my parents after the first time he raped me, they would have stopped it from happening again’. Then, ask the client to bring to mind the moment when they made the decision to act/respond in the way that they did during the traumatic event. In Isabella’s case, we might say, ‘Can you cast your mind back to the point where you decided to make the decision not to speak to your mum and dad about what had happened? Can you see it clearly in your mind’s eye? What can you see and hear? What do you feel in your body? Who else is there? What is happening? Now can you concentrate on this moment, as you decide what to do, what do you think will happen?’. Ensure that they are talking about what they thought at that exact moment, not what they know now. It is important that they are very clear about what they thought would happen when they made the decision and how much at that time they believed that acting differently might have changed/prevented the trauma.

Using Isabella’s example, she cast her mind back to just after the first time the man raped her. She was 13 years old, it was May, and she had been alone in her family home as her parents were at work. She could remember what the room looked like, how it smelled, what she was wearing, and how her body had felt. She remembers wanting him to leave so she could call her mother. Just as he turned to go, he said to her that if she told anyone, he would claim that she had ‘thrown’ herself at him and he had refused. He told her that no one would believe her story and that they would punish her for lying. She remembered thinking he was right because he sounded so sure and calm. She said that, at the time, she believed him completely, she was 100% sure that her parents would not believe her and would punish her if she told them about the rape.

Once you and your client have thought about what they knew during the trauma, make a statement to summarise this prediction. Ensure they are considering the knowledge they would have had at the age of the trauma, and not bringing in information they later understood as an adult. This statement needs to incorporate the fact that they did not know at that time that the (now regretted) consequence would occur. For Isabella you might say, ‘So, when you decided not to tell your parents, at age 13, this was because you thought 100% that they would not believe you, because he had told you this so clearly’. It can be helpful to ask the client to rate how much they believed this at the time out of 100% (0% = did not believe this at all, 100% = believed this completely).

Once you and your client have agreed a statement about their not knowing, ask them to consider a story: ‘Imagine that you have someone staying in your house who has never seen electrical equipment before, perhaps they have always lived very remotely or are an alien from another planet. They are an adult, of normal intelligence, and with normal memory capacity. They come down for breakfast on the first morning that they are staying with you and see you are ironing. They are intrigued by the shiny metal object with a red light on it and touch it with their hand. Would you blame them for the burn they get from touching the iron?

Imagine that the next morning the same person comes downstairs, with a bandage on their hand from the day before. Remember, they do not have a memory problem and are of normal intelligence, and they touch the iron again. Would you blame them for the second burn?’

In this scenario most people would say that they would not blame the person for the first burn, but that they would for the second. Then carry on with the discussion: ‘Why would you blame them for the second burn and not the first? It seems that you are making a judgement about the relationship between what you know and whether you are to blame. Can you tell me more, what do you think is the relationship between knowledge and blame?’.

Most people tend to say that you are to blame if you know that something is going to happen, but that you are not to blame if you do not know. Importantly, this then needs to be discussed in relation to the traumatic event the client has experienced.

Considering Isabella’s example, at the time she considered telling her parents, she was 100% certain that they would not believe her, or 0% certain that telling an adult would make the abuse stop. So, by her own logic, Isabella realised that she could not be to blame for not telling her parents because she did not know it would stop the abuse. The course of action she took at the time made sense given what she knew and believed at the time.

Discuss with the client that we can only make the best decisions we can, given what we knew and believed at the time. Similarly, we cannot be blamed for not knowing what would happen minutes, hours, days, or even years after we make a choice. It is often a good idea to invite the client to summarise this discussion and possibly write it down on a flashcard or postcard to remind themselves. Judging oneself with the benefit of hindsight is likely only to bring suffering. It often causes a cycle of rumination in which a trauma survivor re-plays the experience, searching for and focusing on any signals of impending disaster, engaging in ‘if only I had…’ thinking. In reality any ‘signals’ are unlikely to have been experienced in the same way at the time, because hindsight changes what you attend to. You can discuss with the client whether they are willing to let go of such hindsight judgements.

For a film demonstrating how to discuss knowledge and blame, see: https://bit.ly/CTPTSDGuilt3

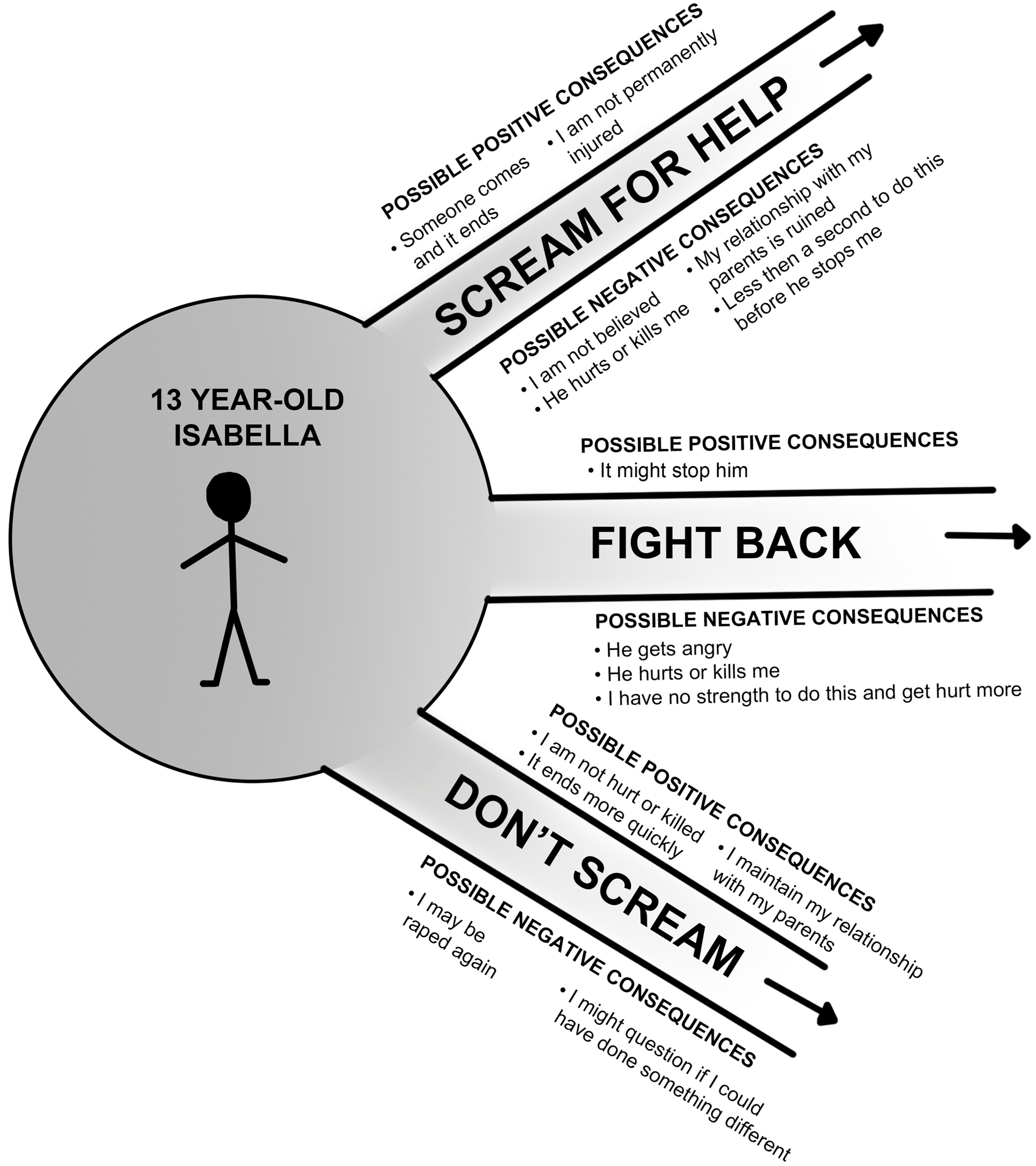

Impossible choices

Often when a client blames themself for a choice they made during a traumatic event, they think that there was a better way of acting, which they chose not to do. In our experience, once you explore the event with the client, you will often find that their choice was the best option. Kubany (Reference Kubany1994) and Norman et al. (Reference Norman, Allard, Browne, Capone, Davis and Kubany2019) refer to this as ‘Catch 22 guilt’; namely that the client was actually faced with only choices with a bad outcome and they will have chosen the least bad one at the time (given what they knew and how they were functioning at the time). An example might be a client who has to choose between leaving someone else to die or to die themselves.

Kubany and colleagues suggest a technique that involves asking the client to bring to mind the moment at which they made their decision. Then, ask them to consider what they thought would be the positives and negatives, in the short term and the long term, of all the possible decisions they could have made at that moment. It is important that they talk about the positives and negatives as they saw them then, during the traumatic event, not now with hindsight.

It might be helpful at this point to draw something like an ‘end of a tunnel’ diagram (see Fig. 2). Place the client at the end of the tunnel and draw all the possible routes out/choices they can think of that were available to them at that time. You could say, ‘To help me understand how things were for you then, can you bring to mind the moment when you decided what to do. Have you got it in your mind now? Tell me what is happening, at that moment, what possible routes out of the situation/choices did you have? For this first possible choice, at that time, what did you think might happen if you made that choice? What were the positive and negative consequences that you would have known at the time? Can you think of any more? Those were maybe the immediate consequences of choosing that route, did you think of any longer-term positives and negatives? Now please tell me about the consequences for the second choice in the short term and the long term etc.”.

Figure 2. Tunnel drawing regarding impossible choices.

Write on the diagram the positives and negatives, both in the short and long term, of all the possible options. Then ask the client to consider whether, on balance, there was a better choice to make, knowing what they knew then, at the time of the traumatic event. Make sure the client is not focusing on the negatives of the choice they made and the positives of the choice they did not make; they must consider both the pros and the cons of each ‘way out of the tunnel’. Do not feel afraid to ask this question, often the client will have made the best choice, given the information they had at that time, in that situation. However, if the client thinks that they actually made the wrong choice, it is worth considering their physical and emotional state at the time they made the decision – were they in a state of shock, dissociated, or inebriated (see psycho-education section below)?

It is likely that people find it hard to believe that they live in a world in which they could face only terrible and negative choices. They want to believe that there was an ideal choice that they could have made, that would have had no bad consequences, but which they somehow missed. The aim of this exercise is to help people to see that, despite feeling that they had free choice, there was actually no real choice; there were no alternatives to what they chose and/or they had no good options to choose from.

It may also be beneficial to discuss how the client was making decisions at the time; they were probably in a state of shock. During trauma, it is common for people to resort to their basic, most automatic need to keep themselves alive. Again, it is only in hindsight that people are able to engage their frontal cortex and weigh up pros and cons of alternative paths of action. This process of a trauma survivor telling themselves they ‘should’ have taken a different choice is likely to be torturous for them. This may be because there was probably no good choice available or because they were not physiologically able to ‘make a choice’ during the traumatic event.

Clinicians learning this technique (and the earlier technique about knowledge and blame) are often fearful of what they will discover when they ask the client to think back to what they knew during the trauma. Clinicians worry that the client will realise that they did know something bad would happen or that they did ignore better courses of action. This is an understandable fear, but we would like to reassure you that it happens very rarely in our experience. Moreover, even if the client does discover that they hold some responsibility, this opens up opportunities to discuss and work out how to help them feel better going forward.

For a film demonstrating how to discuss impossible choices, see: https://bit.ly/CTPTSDGuilt4

Psycho-education

A discussion regarding common physiological reactions to a traumatic event can be useful when people blame themselves and feel guilty for how they reacted during a trauma. They often forget or misunderstand the body’s automatic response to extreme fear.

It can be helpful therefore to spend time discussing the automatic process that occurs when all humans are faced with a threat (Schauer and Elbert, Reference Schauer and Elbert2010). You can explain how initially the brain tells the body to freeze and become still, allowing the person to look around and assess the danger. If the brain thinks the person can fight or run away from the danger, it prepares them to do so; this is the ‘fight or flight response’. In this stage, the sympathetic nervous system is activated and releases hormones into the body. This results in an increased heart rate, increased breathing rate, pale or flushed skin, trembling muscles, and sweating; preparing the person to fight or flee. All unnecessary bodily activity stops, to ensure all energy is directed to escaping the threat. This includes digestion stopping, which can cause nausea, and bladder and bowel muscles relaxing, which can cause incontinence. The world can feel unreal and the person may feel dizzy or lightheaded. This automatic response is likely to explain how someone acted during a traumatic event, for example if they froze briefly, became incontinent or ran away. It may also be important to consider the effects of shock and/or panic reactions when faced with a threat.

If a client describes freezing for a prolonged period of time and being unable to move and react, this could be due to an automatic protective dissociative response at the time of the traumatic event. It can be helpful therefore to discuss an evolutionary explanation of dissociation, highlighting that it is an adaptive response to the circumstances, and that it would have been automatic and outside of their conscious control (Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019; Kozlowska et al., Reference Kozlowska, Walker, McLean and Carrive2015; Schauer and Elbert, Reference Schauer and Elbert2010). Research has demonstrated that it is extremely common for a person to dissociate if the attacker is bigger than them, is restraining or raping them, if they are tied up or injured, or are losing blood (Schauer and Elbert, Reference Schauer and Elbert2010). It is important therefore to impart this information to clients, as they may believe that they should have been able to move and react, when in reality this was not within their control. See Chessell et al. (Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019) for more information about this and how to explain this to a client. Using Isabella’s example, it was important to discuss how freezing during the rapes was an automatic response that everyone would have experienced. Her feeling that she should have been able to fight back receded once she knew this.

Depending on the client’s individual formulation and the context of the traumatic event, it can be important to share other information that might be relevant to their feelings of guilt. For example, it may be beneficial to discuss how it is common for people to experience involuntary sensations of sexual arousal during sexual assault (Ainscough and Toon, Reference Ainscough and Toon2018) or that people often become incontinent when experiencing high levels of fear. For clients who have experienced imprisonment and torture, it can be helpful to share the function and aims of torture (e.g. Five Steps to Tyranny BBC documentary; McDonald, Reference McDonald2000; Young, Reference Young2009). For clients who have experienced childhood sexual abuse, it may be helpful to discuss the factors that lead to an abuser abusing a child (Finkelhor, Reference Finkelhor1984), to emphasise that it is not something that the client did that caused the abuse. Of course, depending on the client, there are many other therapeutic conversations that can be had and information that can be shared which may aid in decreasing their feelings of guilt.

Filling in gaps in memory

Occasionally clients have gaps in their memory for traumatic events. These can be due to brain injury, dissociation, drugs, alcohol, or an unknown cause. For some, this may not cause distress. For others, not remembering how and why they made certain decisions might lead them to assume responsibility for the outcome. Equally, they might not remember the things that they did to help themselves or others during the traumatic event. We will discuss some ideas for how to help guilt arising from memory gaps.

Often, when the client relives the event in chronological order, they may be able to see more clearly how events unfolded and blame themselves less. However, there are some situations in which the client will not remember. For example, amnesia due to brain injury is permanent and will not change, no matter how many times the trauma is relived; if the person is unconscious, they will not be able to recall what happened during that time. If the gaps are not filled by reliving, it may be helpful to support the client to consider the most likely sequence of events, what this would mean for them, and what interpretation would be most helpful for them going forwards. For certain clients, such as veterans, it may be possible to speak to other veterans who were present at the time of the traumatic event who may have helpful information to share. Equally a patient may be able to ask their medical team for information to help reconstruct a memory. If you are able to revisit the site of a traumatic event with a client, this can sometimes help with reconstructing events. Once they see the physical constraints of the site, people are often surprised at how hard it would have been to act in a certain way, e.g. escape/stop in time/scream for help.

Surveys

Surveys can be a helpful tool when a client is judging themself too harshly and it appears that they have not spoken to others regarding their opinion of their culpability. The aim of the survey is to demonstrate that there is more than one way to view the situation and that others would consider them less responsible.

First, it is important to invite the client to predict how they think people will respond to the survey, to enable a discussion between the expected and actual results. Then, agree what questions will be asked, the way of answering (e.g. percentage scale, multiple choice, free text box), and the type of people who will be asked (e.g. age range, gender, occupation). Either the client or the therapist can collect the information, but the client might prefer the therapist to do so anonymously. Surveys can be completed online, using a survey tool/website, or through asking questions and responses being recorded. If possible, it can be very helpful to sit and type the survey directly onto the survey site with the client.

The survey should involve a short introduction about the situation the client was in on the day of the traumatic event. For Isabella, this might be describing the first time that her parents’ friend raped her and she decided not to tell her parents. The following questions could then be used. Question 1: How much do you think this person is to blame for the subsequent rapes occurring? (0–100% scale). Question 2: Who or what else could be responsible? (multiple choice/free text box). Question 3: Please explain why you think this is the case (free text box). The results of the survey were then discussed in session with Isabella, and in particular, the difference between her prediction and what others said about her responsibility for the event occurring.

Considering motivation

A client may be reluctant to work on the issues that are maintaining their guilt. They may be spending a lot of time ruminating on what they could have done differently (Moulds et al., Reference Moulds, Bisby, Wild and Bryant2020). If this is the case, it is important to explore with them what their thoughts and feelings are about working to reduce the guilt or rumination about the event.

Begin by saying that it is common for people to feel unsure about working on reducing their feelings of guilt. They might, for example, consider that letting go of some guilt would make them a bad person or would be dishonourable to the memory of a deceased loved one. They might also worry that reducing guilt-inducing rumination would make them complacent about working to avoid potential future risks.

You can then use motivational strategies to explore your client’s particular ambivalence about reducing guilt. Taking a broad motivational interviewing stance (Miller and Rolnick, Reference Miller and Rollnick2012), have a conversation in which you first acknowledge and validate their feelings about guilt. Then, explore the pros and cons of holding onto the guilt and enhance the negative consequences as they are raised by the client. The decision about trying to reduce guilt must remain with the client. However, the therapist can express hope that they might feel differently in the future and that this might help reduce their PTSD symptoms. You can also work on developing a discrepancy between the life the person wants to live (or their loved one would want for them), and the impact of the guilt (and the PTSD maintained by guilt), in supporting or blocking them from reaching these goals. You can help a client to see that freeing themselves of the emotional drain of guilt and PTSD may in fact free them up to: think of any reparative action they want to take, or to honour their loved one’s memory in a meaningful way, or to weigh up potential future risks in a more concentrated and balanced way.

Sometimes, a client may logically accept that they should feel less guilty than they do, but they believe that they deserve to continue to feel this way. They might view the guilt as a form of punishment, particularly if their actions have caused harm to others. In this case ideas from compassion focused therapy are likely to be beneficial (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009; Lee and James, Reference Lee and James2012), or ideas of self-forgiveness as used in treatment of moral injury (Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009).

Step 5 – For peri-traumatic guilt – inserting updates about guilt/responsibility into the trauma narrative

If the guilt is peri-traumatic, then it is likely that the client may still ‘feel’ guilty, despite successful completion of cognitive work. This is because the traumatic memory remains unprocessed, which results in the client re-experiencing the moment they initially felt guilty, with the full force of the guilt that they felt at the time. The person may also re-experience guilt that occurred shortly after the trauma in the same way and in these instances it would still be beneficial to update the guilt within the trauma memory. To alleviate this, the cognitive work will need to be summarised into something memorable and used to update hotspot(s) in the traumatic memory (see Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Research suggests that updating the trauma memory in this way aids in processing the memory and decreasing the frequency with which it is re-experienced (Grey et al., Reference Grey, Young and Holmes2002; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Grey and Young2005; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Scragg and Turner2001; Nijdam et al., Reference Nijdam, Baas, Olff and Gersons2013).

For Isabella, one of the hotspots in the memory of the second time she was raped is her thinking that it was her fault because she had not told her parents. A verbal update for this hotspot might be, ‘At the time that I made the decision not to tell my parents, I did not know that I would be raped again. I also did not know that they would believe me, so I cannot be blamed for not telling them. Other people were responsible for this happening, especially the man that did this to me, it is not my fault’. It is important to check that the update generates the desired impact (of the guilt decreasing), when inserted into the trauma memory. This can be measured using subjective units of distress (SUDs) if necessary. If a decrease in guilt has not occurred while updating the hotspot, it is important to discuss why this is the case and, if appropriate, to add to or change the update. A good question to ask at this point is, ‘What else do you need to know/need to see to feel less guilty/responsible?’.

Step 6 – Using mental imagery to strengthen guilt re-structuring

In our clinical experience, peri-traumatic and post-traumatic guilt can often be felt both emotionally and also viscerally/within someone’s body. If this is the case, then verbal updates alone may not be enough; it may be necessary to help the client ‘feel’ less responsible in their body too. Transforming verbal information about responsibility into a mental image can sometimes help with this. This image can then be used as an addition to a verbal update of a hotspot in a traumatic memory (to make it ‘stronger’) or as a stand-alone image for post-traumatic guilt. We have found this technique particularly helpful when a client has killed someone or feels responsible for the death of another. In this regard, it may be of use to those working with those affected by COVID-19. An example of how we might use such imagery with Isabella is given below.

Therapist (Th): What I want us to do now is understand how the guilt that we have been talking about makes you feel in a bit more detail. Some people find it helpful to close their eyes and focus on the feeling of guilt. Can I get you to close your eyes and just concentrate on that feeling of guilt … just think about what you feel guilty about … can you feel it now?

Isabella (I): Yes.

Th: When you feel this guilt, do you feel it anywhere in particular in your body?

I: Umm … yes, here [gestures to abdominal area]… and in my throat.

Th: Can you tell me any more about how it feels? Heavy/light, warm/cold… does it feel like any other sensation you recognise?

I: It feels very heavy and oily… umm… like a feeling of dread.

Th: Ok so it feels very heavy and oily, it is there in your stomach area and your throat … does it have a smell or a taste?

I: Yes… a little … it smells like dirty socks.

Th: When you feel it there, can you also see it in your mind’s eye … what does it look like (if it looks like anything at all)?

I: Ha… I hadn’t realised that … it looks like a dark sort of stain or shadow on my stomach and wrapped around my throat.

Th: Do you know why it is there … what is its purpose/what does it want from you or want you to do?

I: It is there to remind me of what I have done … in case I forget.

Th: Ah, that makes sense, doesn’t it … so this dark stain/shadow is there to remind you.

As in this example, if the client has a clear, multi-sensory image of their guilt, then it may be necessary to create a multi-sensory image of the re-structuring information. In this way, the guilt ‘toxic’ image is transformed into an ‘antidote’ image, rather than by words (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Hales, Young and Di Simplicio2019). In our clinical experience, words are effective for re-structuring unhelpful verbal thoughts but ‘antidote’ images are necessary for re-structuring unhelpful images. An example of how to do this is given below.

Th: To remind you, we want to generate an ‘antidote’ image that makes you feel not guilty. We want an image that contains in it all of the information we have discussed about your responsibility for what happened. Perhaps if you close your eyes and say out loud all of the points we have agreed about your responsibility. Just notice as you say them what images spring to mind … one of the images will win over the others.

I: Ok … rapists are responsible for rape and for continuing to rape. When I made the decision not to tell my parents, I did not know that I would be raped again. I also did not know that they would believe me, so I cannot be blamed for not telling them. I was a little child then. Lots of other individual people, and societal attitudes to women and consent, were responsible for this happening, especially the man that did this to me, it is not my fault.

Th: Ok … keep saying this to yourself, over and over and just notice what images spring to mind [waits for a minute]… is any one image stronger than the others?

I: Yes, I can see you and me as I am now… we are standing in front of younger me and saying those words to the dark stain/shadow… oh and we are poking it with a stick… we each have a stick!

Th: Ok that sounds good, shall we try using that image then? We can have a go at generating an image of that scene and see if it produces the emotions we want, not feeling so guilty. If it does not, we will have a clearer idea of what we need by the end of it… so let’s just give it a go. [This curious and experimental stance is important in imagery work, it takes the pressure off both therapist and client and, crucially, allows the client to relax as much as possible, which means their mind is free to be as creative as possible.]

Th: Ok… can you close your eyes again and focus on that scene, me and you and the sticks … can you tell me what is happening?

I: We are in my old bedroom and you and I are in front of 13-year-old me. Each of us has a big stick and we are poking the stain/shadow with a look of disgust and irritation on our faces … we want it to listen. You are saying, ‘Rapists are responsible for rape and for continuing to rape. When Isabella made the decision not to tell her parents, it was best option given what she knew at the time…it is not her fault’.

Th: As you imagine that, can you hear me talking? How do you feel?

I: Yes, I can hear you … I feel better, less guilty … say 40% guilty.

Th: Is there anything else you need in that image to feel less guilty? You can imagine anything you like – it doesn’t have to be real or possible.

I: Hmm … I think I need the shadow/stain to go away… it is still there and I can smell it.

Th: Ok can you make that happen? Imagine it going away, tell me what happens?

I: Yes, adult me pulls it off 13-year-old me and walks over to the door with it … and I put it down the loo and flush it … then I wipe my hands clean on my trousers … it is gone!

Th: How do you feel now?

I: Better … it is not my fault.

Th: What percentage guilt do you feel now?

I: 0%

Th: Good, and how does your body feel now?

I: Wow … the feeling has gone … I feel light and free!

Th: And the smell?

I: Gone!

Th: Do you need anything else?

I: No.

Th: Ok, so that sounds like a good ‘antidote’ image to use to encapsulate the information that you know logically, that you are not responsible for what happened to you.

At this point, there are two ways you can use this ‘not responsible’ image. First, to update a guilt-inducing peri-traumatic hotspot. In this case, you need to bring to mind the hotspot and, when it is vivid, bring in the new image with any agreed verbal and sensory updates. As with other hotspot work, you must check that the new image has reduced the guilt in that moment (see Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Grey et al., Reference Grey, Young and Holmes2002). The second way to use such an image, is to address post-traumatic guilt that has not fully responded to cognitive therapy. In this case, we suggest teaching the client to swap in the new, ‘antidote’ image whenever they experience strong feelings of guilt (for more details, see Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Hales, Young and Di Simplicio2019) An example of how to do this is given below.

Th: So you can practise how to use this image at home, shall we try now bringing on the first image, the feeling of guilt with the shadow/stain on you, and then we can swap in this new image? Again, we can give it a go and see if it works … if it does not, it will become clearer what we need to do to make it work. Ok … close your eyes and imagine the feeling of guilt that you get, notice where it is in your body, what it looks like … tell me what you can see.

I: I can see it on my body, oily and dark … it makes me feel terrible.

Th: Ok now bring in the new image, of me and you with the sticks and the loo flushing [client describes the image of therapist and her adult self, talking to and removing the shadow]. How do you feel now?

I: Good, no guilt, relieved … all gone.

Th: Let’s try it one more time, first imagine yourself sitting with the feeling of guilt …

It is a good idea to repeat the exercise in the session (if you have time), bringing on the feeling of guilt and then swapping in the ‘antidote’ image. This will increase the client’s feeling of mastery over the old, unhelpful image. You can suggest to the client that they do the same substitution every time they feel the guilt in the future. However, in our clinical experience, the feeling of guilt will come back much less frequently once this image-swapping intervention has been done in session.

For films demonstrating how to use mental imagery to strengthen guilt re-structuring, please see:

-

Characterising a guilt image: http://bit.ly/CTPTSDGuilt5

-

Generating a guilt antidote image: http://bit.ly/CTPTSDGuilt6

-

Swapping in an antidote guilt image: http://bit.ly/CTPTSD7

Finally, a common reason for guilt becoming a chronic problem for trauma survivors is that it ordinarily motivates efforts at reparation. However, the consequences of traumatic events are frequently unable to be repaired (Tangney et al., Reference Tangney, Wagner and Gramzow1992). We have found that, in these instances, imagery has a powerful role to play, giving a trauma survivor a chance to imagine what they would like to do if it were possible. This has been particularly powerful in our work with traumatic bereavement, where a trauma survivor could imagine, for example, how they would have liked to say goodbye to their loved one.

Summary

This article outlines a CBT approach to treating feelings of guilt. The ideas we have presented can be used alongside other core strategies such as Socratic dialogue. While the therapeutic techniques were developed in the context of working with clients with a PTSD diagnosis, the ideas can also be used when working with clients who do not meet a diagnosis of PTSD, but who still experience strong feelings of guilt. We discussed the reasons why someone might feel guilty and briefly how to assess and formulate feelings of guilt. We then described in detail cognitive and imagery techniques which can be used to reduce feelings of guilt. Careful consideration and remediation of guilt in someone’s presentation can lead to rapid and transformative changes in wellbeing.

Key practice points

-

(1) Guilt is a self-conscious emotion that relates to a sense of responsibility for being the cause of harm to self or others or failing to prevent harm to self or others (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Scragg and Turner2001).

-

(2) Guilt should be assessed and formulated on an individual basis and often in the context of a broader PTSD formulation (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000).

-

(3) Treatment for feelings of guilt aims to identify the underlying reason for feeling guilty and design a cognitive and/or imagery intervention based on that reason.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to our clients who we have worked with on their feelings of guilt.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical statements

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BPS. Ethical approval was not needed as the article is based on clinical insight and experience.

Data availability statement

There are no data in this article.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.