The volume of drugs prescribed in high-income countries continues to rise. In 2008 in England, 842 million prescription items were written in the community alone, representing an increase of 64.1% over the previous 10 years (NHS Information Centre, Prescribing Support Unit 2009). Although professionals may be writing increasing numbers of prescriptions, patients are not necessarily taking the medicine. The World Health Organization report on adherence to long-term therapies called non-adherence ‘a worldwide problem of striking magnitude’ (World Health Organization 2003). In common with those working in other branches of medicine, mental health professionals often focus on improving patients' adherence to prescribed medication. There is an uncritical assumption that improved adherence is always desirable and that the clinical task is to overcome any barriers to this. Thus for example, Reference Mitchell and SelmesMitchell & Selmes (2007) provide in the pages of this journal a detailed discussion of the predictors of missed medication and simple strategies to improve adherence in psychiatry. These include the development of therapeutic alliances, although compulsion always remains an option. This has also been discussed in this journal (Reference ChaplinChaplin 2007).

Understanding non-adherence

A particular aspect of psychiatry is that non-adherence is sometimes viewed as another symptom of mental illness, despite the fact that it is a universal phenomenon. For some authors, patients with psychiatric problems are seen as more irrational than other patients. Thus for example, non-adherence may be attributed to the patient's lack of insight; such an attribution then renders problematic anything the patient says (Reference Olfson, Marcus and WilkOlfson 2006). This is consistent with the general research literature and clinical practice, which are both based on the assumption that the problem of non-adherence is primarily caused by patients' shortcomings such as forgetfulness or lack of comprehension about how to take a particular medication.

Studies of medicine-taking

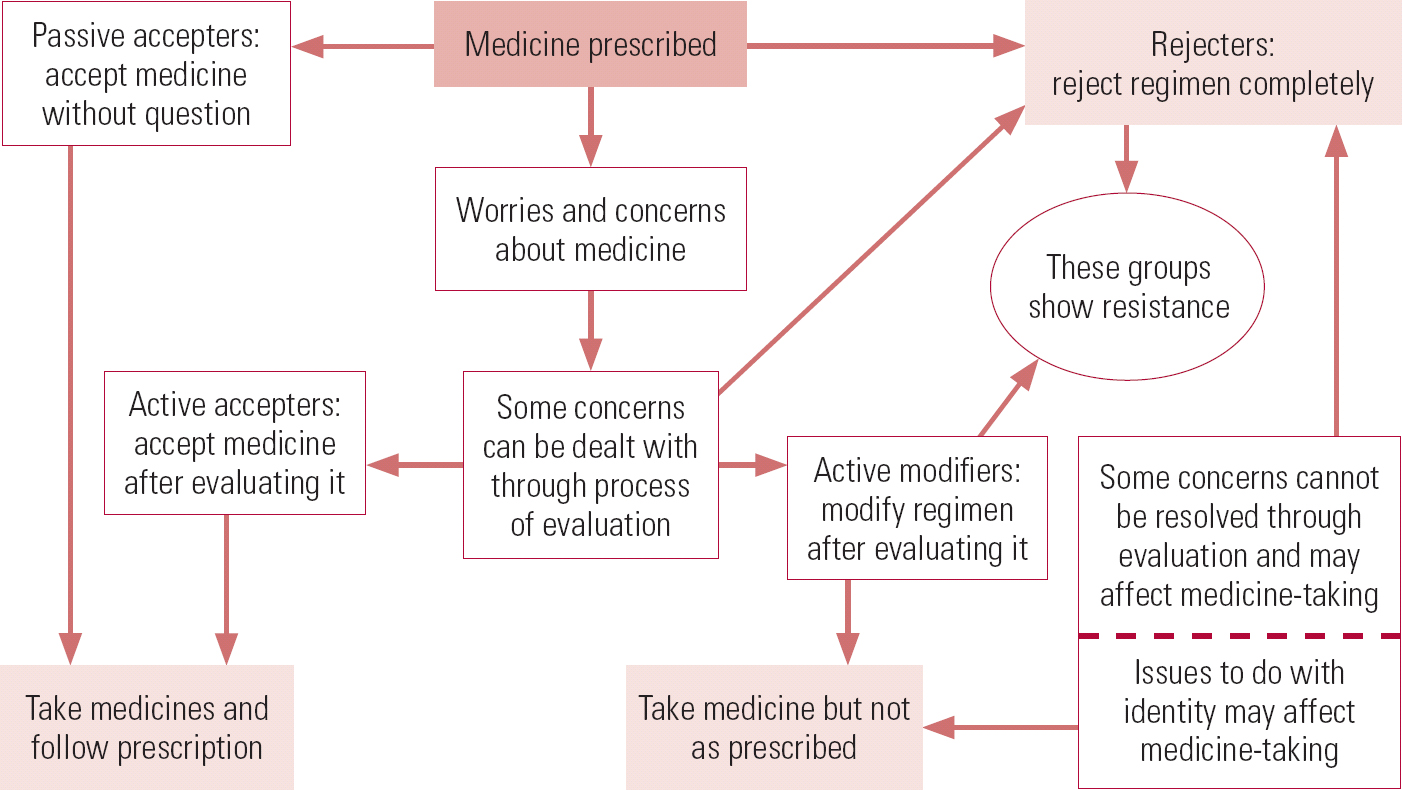

Social scientists have taken a different approach to the problem, criticising the paternalistic approach to medicine-taking embodied in the notion of ‘compliance’ (for which adherence is a less offensive synonym). The earliest and possibly most cogent critique was articulated by Reference StimsonStimson (1974), who pointed out that compliance studies used an ideal image of the patient as a passive, obedient and unquestioning recipient of medical instructions. In the same tradition, Reference DonovanDonovan (1995) identified a number of assumptions inherent in the concept of compliance: that doctors know what is best for their patients; that they can impart medical information clearly and neutrally; that they prescribe effective treatments rationally; and that they are the principal or only contributors to medication decisions. These sociological critiques have informed a stream of mostly qualitative research about patients' perspectives on prescribed and other treatments. This literature was synthesised by Pound and colleagues (Reference Pound, Britten and MorganPound 2005), who grouped studies into seven medication groups to develop a general model and new conceptualisation (Fig. 1). The model of medicine-taking they developed described a number of ways in which patients make decisions about taking medicines and included the notion of lay evaluation that emerged from the synthesis.

Resistance

The new concept that emerged from the synthesis was that of ‘resistance’, which refers to the ways in which people take medicines and attempt to minimise their intake. The term resistance also captures people's active engagement with their medicines, the ingenuity and energy required to do this and the fact that inherent power relationships result in the concealment of these activities from doctors.

Categories of medicine-taking

The model of medicine-taking identified four categories of medicine-taking:

-

• passive accepters take the medicine without resistance (often because patients trust the prescriber and are willing to do what the prescriber asks them to do)

-

• active accepters take medicine as prescribed but only after a period of lay evaluation

-

• active modifiers conduct lay evaluation, which leads them to take their medicines in their own way, which may involve changes in dose, frequency of dose or stopping the medicine altogether

-

• rejecters reject the medication completely and may not even obtain the prescription.

It is recognised that these are not fixed categories and that individuals' adoption of these different approaches to medicine use may change over time. Our emphasis was therefore on identifying the varying influences on patients' decisions about their use of psychotropic medicines.

Conducting the synthesis

Pound etal's synthesis (Reference Pound, Britten and MorganPound 2005) covered 1992–2001 and included six articles about psychotropic medication. It employed meta-ethnography to conduct an interpretive synthesis of the articles. This is a new approach to the systematic synthesis of qualitative papers that we and others have been developing (Reference Britten, Campbell and PopeBritten 2002; Reference Campbell, Pound and PopeCampbell 2003). As coauthors of the earlier synthesis, we were commissioned to write this article to show the relevance of the model presented by Pound et al for a psychiatry readership. We systematically searched seven databases (MEDLINE, PubMed, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO, Embase, ASSIA and Web of Science) between 2002 and 2008 and did not undertake any hand searching. We identified 43 potentially relevant articles. This search was completed before the paper by Malpass et al (Reference Malpass, Shaw and SharpMalpass 2008) was published.

Excluded articles

Twenty articles were excluded following initial appraisal because they did not use qualitative data collection and did not focus on psychotropic medications, and a further 16 papers were excluded following detailed appraisal because they did not use qualitative analysis, referred to various medications thus defying categorisation into discrete medication groups, were not focused on medication use, provided only limited data extracts, or the primary diagnosis was not a mental health problem. The excluded articles would have contributed little to the synthesis because of the paucity of relevant material or an inability to differentiate between medicine groups; their exclusion is therefore unlikely to have biased the results.

Included articles

Thus, we added 7 articles to 5 from the original review, giving a total of 12 articles contributing to the updated synthesis. We divided the articles into three drug groups: antidepressants, antipsychotics and benzodiazepines. The characteristics of the studies included in the syntheses are shown in Table 1. We devised coding categories derived from the model of resistance at the societal and individual levels. Habermas' concept of the ‘lifeworld’ refers to the everyday social world in which cultural meanings are shared and transmitted through socialisation (Reference FinlaysonFinlayson 2005). At the societal level, we coded lifeworld worries and concerns under two headings: social meanings of mental illness and social meanings of medicines. At the individual level, we coded resistance involving active engagement and lay evaluation under four headings: adverse effects; costs and benefits; difficulties in attribution; and stopping and seeing what happens. Outcomes of lay evaluation were coded under six headings: minimisation; resistance despite admonishments, coercion and sanctions; non-pharmaceutical options; concealment of medication practices; and doctor–patient relationships. Data from each paper was extracted by two authors.

The aims of this article are to present the results of the synthesis of 12 qualitative articles on patients' perspectives on psychotropic medications, to elaborate on the concept of resistance in relation to the three drug groups, and to consider the implications for clinical practice in mental health. The results of the synthesis are presented in Tables 2–4 and summarised below. We can only include those factors reported in the synthesised papers, with absence of a reference to particular findings not necessarily constituting evidence of absence.

Resistance at a societal level

Lifeworld concerns and worries (Table 2)

Difficulties concerning acceptance of or resistance to the illness label and treatment of mental health problems often reflected respondents' concerns about perceived stigma. This was particularly significant for people diagnosed with schizophrenia. In contrast, the use of benzodiazepines, especially as hypnotics for sleeping problems, was regarded as less stigmatised. Across the drug groups, there was a perception that dependence on drug treatment was associated with the need to accept a new illness identity and associated treatment unquestioningly, thus reducing their perceived autonomy and increasing the negative social meanings.

For respondents taking antidepressants, their resistance to diagnosis and treatment was also influenced by lay understandings of the causes of their mental health problems. For example, people who attributed depression to personal problems viewed medication as an inappropriate response.

For respondents taking antipsychotics, the experience of embarrassing and visible side-effects exacerbated pre-existing concerns about stigma. The use of antipsychotics as a means of social control was also widely referred to, with concerns expressed about the perceived and sometimes enacted use of social control to enforce adherence.

For those taking antidepressants and benzodiazepines, there were concerns about psychological dependency and not being able to cope without the use of medications.

Resistance at an individual level

Active engagement and lay evaluation (Table 3)

A key aspect of resistance was respondents' attempts to evaluate and balance the positive and negative aspects of medicine use, especially adverse effects.

Adverse effects

Many respondents across the drug groups experienced physical and psychological side-effects ranging in severity that prompted them to critically evaluate their treatment in terms of the associated risks and benefits. For people taking antipsychotics, their experience of recognisable and illness-defining side-effects (such as involuntary limb movement) added to the pre-existing stigma and contributed to social withdrawal and the relative lack of supportive and intimate relationships for people living in the community. These negative and stigmatising attributes of antipsychotic side-effects affected people's day-to-day lives and sometimes led to the decision to stop taking medication.

Costs and benefits/weighing and balancing

There were similarities in the way that respondents taking antipsychotics and benzodiazapines assessed the potential benefits against the possible risks of taking their medications. Individuals taking antipsychotics, for instance, continuously evaluated their medication by weighing and balancing perceived positive effects of a reduction in illness symptoms against perceived risks of side-effects to achieve ‘wellness’. Many of these respondents therefore made a trade-off when adjusting the dose to maximise benefit and minimise side-effects. However, whereas for most respondents this led to a reduced use of prescribed medicines, some respondents, notably the community-based respondents in North etal's study (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995), viewed the potential benefits of taking benzodiazepines (such as an improved quality of life) as outweighing the perceived negative aspects in terms of risks of side-effects, social alienation and physical dependency.

For respondents taking antidepressants, the process of assessing costs and benefits was frequently underpinned by concerns about the long-term use of medication. However, some individuals accepted the short-term use of antidepressants to provide temporary support and to ‘kick start’ the process of recovery. Initial concerns were also sometimes replaced by more positive beliefs about antidepressants as an effective and acceptable treatment, whereas other individuals had to cope with prolonged distress and doubt about the efficacy of the treatment.

Other respondents had additional worries about the role of antidepressants in their lives. Concerns about dependency and being reliant on a chemical played a key factor in people's assessment of their selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Although people felt normal with medicines, they also perceived that they would only be able to feel completely normal without them. The quest for normality and a desire to manage their emotional state without the need for medication led respondents to want to quit their treatment.

To manage such fears and concerns about dependency, respondents often developed physical and pragmatic arguments for justifying their continued medication that also enabled them to exert greater control over their treatment and illness. For instance, some respondents reasoned that their bodies needed a chemical substance to deal with the physical symptoms and therefore hoped that the deficient substance (serotonin) would build up in their bodies so that they could stop in the future. Others reasoned that their bodies could not produce this. Pragmatically, some respondents were afraid of being a nuisance to others (e.g., to children or colleagues) and therefore used medication to help lead a ‘normal’ life.

Difficulties in attribution

Difficulties in attribution associated with antidepressants occurred in response to uncertainty about the effectiveness of medications and whether they were solely responsible for any changes in symptoms. Some individuals, for instance, were perplexed by the lack of noticeable effects of antidepressants and found it hard to ascertain when they had begun to feel better; it was sometimes difficult to disentangle the effects of antidepressants from other factors, such as changes or improvements in personal circumstances or the ‘therapeutic passage of time’.

For people taking antipsychotics, attributional difficulties were mainly concerned with problems discerning whether symptoms were related to the illness or iatrogenic effects of the medication.

Difficulties in attribution also arose as a result of individual variability when people's experience of treatment varied at different times while on the same treatment. Many individuals were also unprepared for medication making them feel worse initially. It was only when people were given sufficient information about medication that they felt more able to comply with a prescribed course and therefore had more confidence in their treatment.

Stopping and seeing what happens

Many respondents taking psychotropic medication either intended to stop or actively discontinued their medication to see what would happen. This was evident across all drug groups. It occurred in response to an improvement in symptoms or particularly for individuals taking antipsychotic medication because of their perception of side-effects or because they did not accept the diagnosis. However, the lack of or conflicting information regarding withdrawal effects meant that the decision to stop taking their antidepressants and benzodiazepines was often fraught with worries about withdrawal effects or the possibility of returning symptoms and potential relapse.

For the few individuals who discontinued their antipsychotic medication, reasons were often related to unwanted side-effects or because individuals did not accept their diagnosis.

Outcomes of evaluation (Table 4)

Minimisation

For individuals taking both antidepressants and antipsychotics, minimisation or discontinuation were responses to concerns about, and the experience of, minor and severe side-effects of both drug types. Individuals taking antipsychotics purposefully adjusted their medication to maximise its benefits and minimise unwanted side-effects. Minimisation for these drug groups was also used as a strategy to enable individuals to exert more control over their medicines and to regain perceived lost autonomy.

Specifically for some individuals taking antipsychotics, minimisation resulted from a reluctance to accept their diagnosis or was undertaken situationally, such as when individuals knew they would be drinking alcohol.

For respondents taking antidepressants, minimisation was exemplified by those who discontinued or reduced their dose of antidepressants or by those who adopted non-pharmaceutical options. For these individuals, minimisation was in response to concerns about psychological dependency, to make individuals feel more comfortable about taking medication and in response to a lack of improvement in psychiatric symptoms.

Refutational findings were found in individuals who indicated that they would like to increase their dosage of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and benzodiazepines to aid recovery and in reports of those individuals who took antipsychotics as prescribed.

Resistance despite admonishments, sanctions and coercion

The threat of admonishments, social sanctions and coercion in response to non-adherence was predominantly a concern for individuals taking antipsychotics. Individuals perceived that the enactment of social sanctions would not only reduce their autonomy but would also jeopardise their access to future care. This perceived loss of autonomy was exacerbated by the feeling of being under constant surveillance or external control, or being monitored for signs of illness.

Respondents in Rogers et al's study (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998) felt unable to discontinue their medication because of coercion or the perceived power that others could exert over their lives. Whereas some individuals perceived ‘imposed compliance’ resulting from the pressure to comply from medical professionals, friends and family, others described the actual experience of professional power, social and legal sanctions.

Conversely, for respondents taking benzodiazepines, it was often the general practitioners who had challenged individuals to reduce or stop taking their medications and it was general practitioners who were resistant to prescribing them.

Non-pharmaceutical options

Respondents across the drug groups used a range of non-pharmaceutical options to manage their emotional distress or to cope with the withdrawal effects. These included counselling, psychological therapies, talking, using herbal remedies such as St John's Wort or over-the-counter herbal sleeping tablets, and various relaxation techniques.

To address unwanted side-effects of anti-depressant and antipsychotic medication, respondents often undertook lifestyle changes, drank more fluids to combat dry mouth or used nicotine or caffeine to fight tiredness. Some individuals taking antipsychotics reported self-medicating with street drugs (illegal recreational drugs) to cope with both psychotic symptoms and iatrogenic effects of prescribed antipsychotics. However, refutational findings showed that some individuals recognised that substances such as alcohol and street drugs should be avoided.

Although use of non-pharmaceutical options was widely reported, refutational findings were also found among members of the benzodiazepine self-help group who seemed to rely almost exclusively on their medication without developing other strategies to manage their symptoms.

Concealment of medication practices

Users of antipsychotics concealed medication changes in a context of perceived social sanctions, coercion and a perceived lack of credibility in beliefs held by someone with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Given the risk of perceived sanctions and expectations to adhere to their prescriptions, individuals often felt they had no choice but to hide their medication practices from doctors, friends and family. There was evidence of individuals altering their medications without the doctor's consent and individuals who felt they had to conceal practices such as dose reduction or use of alternatives by not disclosing or by managing the information given to the doctor.

Although it was uncommon for individuals to stop medication in collaboration with their prescriber, some respondents temporarily stopped their antidepressants because their doctor suggested it.

Doctor–patient relationships

Individuals across the studies reported having difficulty accessing appropriate support and information that affected the way they managed their medication and illness. For example, the advice given about treatment length of antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors influenced some individuals' later decision-making about whether or not to continue with their medication; disparity in such information also led to concerns and confusion about whether to stop or continue with their treatment.

Respondents' relationships with their doctors (feeling genuinely included in decision-making) seemed to vary from doctor to doctor and during the course of treatment. Some respondents reported feeling disempowered, whereas others felt more included in decision-making about their treatment, which had consequences for improved symptoms and reduced patients' concerns about adverse side-effects. There were additional reports of discordance between lifeworld and professional concerns about medications, whereby individuals perceived that doctors were more concerned with reducing symptoms and less with improving quality of life.

Community-based benzodiazepine users reported having more trusting relationships and were given a high degree of autonomy by their general practitioners. People's confidence in the efficacy of benzodiazepines was related to the trust they placed in their doctor.

Although shared decision-making was generally seen as preferable, there was contrary evidence in one respondent taking benzodiazepines who reported that taking more control in their medication management resulted in worsening insomnia. Similarly, having more control over decision-making was not always welcomed by some individuals taking antipsychotics who expressed a traditional deference to medical authority.

Conclusions

This synthesis of studies of psychotropic medicine users depicts people who were actively engaged with their medicines and, like patients prescribed treatments for physical disorders such as hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis and asthma, they generally wanted to minimise their medicine use. A major concern for patients treated for psychotic and depressive conditions, like those treated for HIV/AIDS and epilepsy, was the felt stigma surrounding their diagnosis, reflecting what are continuing negative social attitudes to mental illness despite public campaigns (Department of Health 2007). Medicine use thus both emphasised the seriousness of their condition and served as a daily reminder of its socially devalued status. Concerns about psychological dependence, although shared with other conditions, also assumed particular significance for patients prescribed antidepressants. This reflected the meaning of depression in terms of conveying patients' own inability to cope with life, and the effects of antidepressant drugs in achieving changes in their self-perceptions and self-image rather than merely influencing the immune system or other physiological processes. Other major concerns for patients prescribed psychotropic medicines and reasons for their ‘resistance’, arose from their experience of side-effects that were often uncomfortable, frightening, embarrassing and confusing. Patients prescribed psychotropic drugs also shared concerns with medicine users more generally about becoming physically or psychologically addicted; some raised concerns about the efficacy of the drugs or the dose prescribed. In addition, for patients with psychotic conditions a further concern related to possibilities of enforced treatment.

Purposeful non-adherence

The cumulative evidence from qualitative studies therefore indicates that patients' ‘non-adherence’ to antipsychotic and antidepressant medication is often a purposeful action, rather than reflecting traditional notions of ‘non-compliance’ and patient ‘default’. Moreover, their non-adherence in terms of minimising the dose, or occasionally stopping the drugs altogether, was not engaged in lightly. Conforming with Pound etal's notion of ‘resistance’ (Reference Pound, Britten and MorganPound 2005), this involved considerable efforts to evaluate and assess the effects of the drugs based on a complex balancing and assessment of possible outcomes and a desire to be cautious. However, patients' assessments and actions frequently involved incomplete knowledge. They therefore experienced difficulties in attributions of cause and effect, fears about the effects of stopping the drugs and possibilities of relapse, and concerns about the dosage prescribed.

Experiential knowledge

Evidence of patients' active engagement with their medicines and the difficulties they often experienced identifies their need for greater support, particularly as, like other patient groups, the changes they made to psychotropic drug regimes were usually concealed from doctors. This was of particular significance for patients prescribed antipsychotic drugs, many of whom perceived a greater risk of sanctions and expectations to adhere. One resource to assist and support patients in coping with medicine use is the increasing availability of specialist internet sites. Reference Pestello and Davis-BermanPestello & Davis-Berman's (2008) study of 227 postings identified the ways in which people shared their stories about depressive illness and ways of managing the medication. This showed that the postings were characterised by a strong commitment to taking the drugs and often drew on considerable experiential knowledge by people who had been on the drugs for several years to provide useful information and support. However, the internet and other patient-based self-help resources need to be complemented by more open discussion with doctors, as the doctor–patient relationship is known to be a key influence on how people manage their concerns about medicines (Reference Day, Bentall and RobertsDay 2005).

A few respondents in the studies synthesised spoke positively about sharing treatment decisions and being supported by their doctors. However, the more common experience was of a more traditional guidance–cooperation relationship, characterised by a lack of patient involvement and doctors' dismissive reactions to patients' reported adverse effects. Changing this traditional relationship requires a cultural shift that acknowledges the validity and relevance of patients' concerns and experiential knowledge. This extension of patient-centred medicine is supported by the increased emphasis given to users' involvement in their care and corresponds to the notion of ‘concordance’ between professionals and patients in terms of prescribing (Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain 1997).

Doctor–patient partnerships

Consultations based on concordance between doctor and patient require that patients' experiential knowledge is listened to and valued, and that emphasis is given to patients' own priorities for their care. This relationship therefore requires an interaction based on listening and sharing information, in which the professional elicits and works with patients' own experiences of psycho-tropic medicine use. The aim is to work with patients in reducing side-effects through guiding their attributions of cause and effect and facilitating assessment of the effects of different drugs or doses to achieve the optimal prescription for individual patients. Where the doctor disagrees with the patient's choice, a concordant approach would be to explain why another option is preferred. In addition, many patients desire to minimise medicine use through a more holistic approach, which requires that doctors give greater emphasis to the use of various talk therapies and other forms of support.

We recognise that adopting a concordant approach to prescribing can be difficult to achieve for a number of reasons. Research conducted in primary care has shown the potential for mutual misunderstanding and has also shown the complex relationships between patients' expectations, doctors' assumptions and perceptions, and clinical necessity (Reference Britten and UkoumunneBritten 1997, Reference Britten, Stevenson and Barry2000). In addition, the aim of national treatment guidelines is to provide standardised care, which may conflict with the more individualised approach of concordance. Within psychiatry, professionals' experiences of homicide and suicide by their patients will exert a powerful influence on their willingness to deviate from standardised treatments. The introduction of community treatment orders in the UK creates an even less favourable environment for establishing a ‘supportive and empathic relationship’ (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2009: p. 11).

Despite these caveats, there is much scope for achieving concordance and supporting patients who are not subject to community treatment orders and who are legally free to use their medicines as they wish to (Box 1). There are potential therapeutic gains from using the model of concordance if treatments are accepted rather than rejected. The need for individualised treatments is not only desired by patients but may often have therapeutic benefits. As Reference ChristakisChristakis (2008) has pointed out, doctors' failure to acknowledge that many drugs do not work for large numbers of people for whom they are prescribed means that the option of stopping or switching to other drugs is often not considered. A longer-term and more ambitious goal would therefore be to undertake the research required to underpin more closely individualised treatments (Reference De Smet, Kramers and BrittenDe Smet 2007). The ability to more precisely tailor prescribing to take account of between-individual differences in weight, organ functions, pharmacogenetic properties and so on would significantly improve the benefit-to-risk ratio for patients.

BOX 1 How can health professionals achieve concordance?

-

• Create a permissive environment in which patients can express their concerns

-

• Avoid judgemental responses to what patients say about their medicines

-

• Develop curiosity about patients' reasons for altering their medicines

-

• Learn to value patients' experiential knowledge

-

• Elicit patients' own priorities

-

• Give an honest opinion and explain the reasoning

-

• Be prepared to negotiate

-

• Discuss non-pharmacological treatments where appropriate

-

• Only involve patients to the degree that they want to be involved

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The following is not a category of medicine-taking patients:

-

a active accepters

-

b rejecters

-

c active modifiers

-

d passive accepters

-

e adherers.

-

-

2 The following is a form of resistance to medication at a societal level:

-

a minimisation

-

b social meanings of mental illness

-

c difficulties in attribution

-

d weighing and balancing costs and benefits

-

e poor doctor–patient communication.

-

-

3 Concordance is another word for:

-

a adherence

-

b compliance

-

c resistance

-

d partnership

-

e minimisation.

-

-

4 Similarities across the drug groups was evidenced by:

-

a the way people concealed their medication practices

-

b the desire for complete autonomy in decisions about medication

-

c the way people perceived the threat of social sanctions

-

d the rejection of a biomedical explanatory model

-

e the experience of unwanted and distressing side-effects.

-

-

5 Psychiatric patients are a special case because:

-

a they lack insight

-

b they are worried about dependence on their medicines

-

c they resist medicine-taking

-

d their medicines affect their mental functioning

-

e they are not cooperative.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | b | 2 | b | 3 | d | 4 | e | 5 | d |

TABLE 1 Studies included for synthesis

| Drug group | Paper | Country | Sample | Source of recruitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants | Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield et al (2004) | UK |

n = 51 (F = 29; M = 22); 19–61 years Range of social classes |

General practices |

| Reference Grime and PollockGrime & Pollock (2003) | UK |

n = 32 (F = 23; M = 9); 20–69 years Range of social classes; rural suburban and urban locations |

General practices | |

| Reference Grime and PollockGrime & Pollock (2004) | UK |

n = 30 (F = 23; M = 7); teens–70s Rural and urban locations |

Voluntary sector (Depression Alliance) | |

| Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam et al (2004) | UK |

n = 19 (F = 14; M = 5); 18–63 years Range of occupational backgrounds |

Workplace and anxiety-management group | |

| Reference Knudsen, Hansen and TraulsenKnudsen et al (2002) | Denmark |

n = 12 (F = 12); 21–34 years Range of socioeconomic backgrounds |

Pharmacies | |

| Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida & Mathot (2006) | The Netherlands |

n = 16 (F = 9; M = 7); 30–80 years Range of social and educational backgrounds |

Community pharmacies and general practices | |

| Antipsychotics | Reference Angermeyer, Löffler and MüllerAngermeyer et al (2001) | Germany |

n = 80 (F = 32; M = 48); 18–60 years Range of educational backgrounds, living arrangements and urban and rural locations |

In-/out-patients at university and state hospitals |

| Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick et al (2004) | UK | n = 25 (F = 12; M = 13); 24–70 years | Out -patient and day centres | |

| Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers et al (1998) | UK |

n = 34 (F = 12; M = 22); 18–56 years Range of social classes, backgrounds and living arrangements |

Voluntary sector (MIND) and in-/out-patient referrals | |

| Reference UsherUsher (2001) | Australia |

n = 10 No additional information supplied |

Consumer groups | |

| Benzodiazepines | Reference Barter and CormackBarter & Cormack (1996) | UK | n = 11 (F = 10; M = 1); elderly 60–89 years | General practice |

| Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth et al (1995) | New Zealand |

n = 22 (F= 11; M = 11); 30–89 years Range of social classes backgrounds and living arrangements |

General practice and TRANX (a tranquilliser self-help group) |

TABLE 2 Resistance at a societal level: lifeworld concerns and worries

| Resistance concepts | Similarities | Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Social meanings of mental illness (stigma, autonomy, identity, medicalisation) | Concerns about perceived and felt stigma associated with diagnosis had consequences for the way individuals accepted and managed their identity, autonomy, illness, and antidepressant and antipsychotic treatment (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Knudsen, Hansen and TraulsenKnudsen 2002; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2004; Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) |

Antipsychotics

Visible side-effects added to concerns about stigma, and desire for ‘normality’ was strongly linked to these concerns (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference UsherUsher 2001; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Antidepressants Being prescribed antidepressants was doubly stigmatising for some individuals: the illness label involved the pathologisation of an emotional state and having to come to terms with the ‘new you’ (Reference Knudsen, Hansen and TraulsenKnudsen 2002) Concerns about being perceived as being ‘hooked on’ drugs, although they did not think of themselves as drug addicts (Reference Knudsen, Hansen and TraulsenKnudsen 2002; Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) Other individuals regarded themselves as a nuisance to others and therefore viewed medication as a pragmatic response (Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) Resistance to diagnosis and treatment was also determined by lay understandings of mental illness, which varied from biomedical (Reference Knudsen, Hansen and TraulsenKnudsen 2002; Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) to psychosocial beliefs, e.g. some attributed depression to personal problems for which medication was viewed as an ‘intrinsically inappropriate solution’ (Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2004) Benzodiazepines Individuals attending the self-help group perceived benzodiazepines more negatively because the drugs had affected their relationships, mood and memory and had come to dominate their lives (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Refutational findings There was less stigma and more ambivalence for individuals taking benzodiazepines; for users of hypnotic benzodiazepines, sleeping problems were not regarded as socially problematic (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995; Reference Barter and CormackBarter 1996) |

| Social meanings of medicines (fears of dependence) | Being reliant on a chemical to effect a ‘new you’ led to widespread fears about psychological dependency and concerns about not being able to cope without the use of medications (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003, Reference Grime and Pollock2004; Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield 2004; Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004) For benzodiazepine users, dependency was contingent on the dose; the lower the dose, the less concern about dependency (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Some concerns were expressed about the risk of physical addiction to the antipsychotic clozapine (Reference Angermeyer, Löffler and MüllerAngermeyer 2001), fears about physical dependency in the benzodiazepine self-help group (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995), and worries about physical addiction linked to antidepressant withdrawal (Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield 2004; Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004) Becoming reliant on medication was perceived as a sign of weakness across the drug groups (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995; Reference UsherUsher 2001; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003, Reference Grime and Pollock2004; Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield 2004; Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004) The experience of side-effects was a key lifeworld concern for many individuals across the drug groups (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995; Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Angermeyer, Löffler and MüllerAngermeyer 2001; Reference UsherUsher 2001; Reference Knudsen, Hansen and TraulsenKnudsen 2002; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2004; Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004, Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) |

Antipsychotics

Side-effects often resulted in a perceived loss of control and autonomy and disconnectedness with oneself. Accepting one's medication meant having to embody a stigmatised illness and accept long-term medication use (Reference UsherUsher 2001) Among antipsychotic users the perceived and sometimes enacted use of social control to enforce adherence was a key concern (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998) Antidepressants Concerns about the effectiveness of medications arose in response to therapeutic delays and difficulties in attributing changes or benefits to the medication alone (Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003; Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) Concerns about the efficacy of antidepressants also emerged in response to doubts about correct dosage (Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield 2004) or confusion about length of use (Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) Refutational findings Some individuals indicated that they would like to increase their dosage of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to aid recovery (Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) |

TABLE 3 Resistance at an individual level: active engagement and lay evaluation

| Resistance concepts | Similarities | Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse effects | Respondents across the three drug groups reported distressing and unwanted side-effects: individuals taking antipsychotics, for example, experienced mild to severe side-effects, including drowsiness, restlessness, lack of motivation, dry mouth, weight gain, dizziness, fainting, blurred vision, shakes, nervousness, slurred speech, loss of concentration, spasms, and general descriptions such as feeling like a ‘zombie’ (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Angermeyer, Löffler and MüllerAngermeyer 2001; Reference UsherUsher 2001; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) individuals also had concerns about antidepressant and antipsychotic side-effects and the effect on their sense of identity (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003, Reference Grime and Pollock2004) physical and psychological side-effects were also unwanted and compromised people's well-being (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) using alternative therapies, free from side-effects, was seen as a distinct advantage (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004) individuals wanted to be better informed about side-effects to enable them to deal with the consequences (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004) concerns were expressed about possible withdrawal effects (Reference Barter and CormackBarter 1996; Reference Knudsen, Hansen and TraulsenKnudsen 2002; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2004; Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004; Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) |

Antipsychotics

Embarrassing antipsychotic side-effects such as involuntary limb movements affected an individual's sense of identity, marked people out as different and contributed to the exacerbation of social withdrawal or the relative lack of supportive and intimate relationships (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference UsherUsher 2001; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) One in ten respondents in Reference Angermeyer, Löffler and MüllerAngermeyer's (2001) study were unaware of some of the long-term risks associated with clozapine, such as the risk of damage to the haematopoietic system Impact of antipsychotic side-effects on people's day-to-day lives was also a factor affecting the decision to stop taking medication (Reference UsherUsher 2001) Antidepressants The experience of side-effects also led to difficulties in attribution (Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003, Reference Grime and Pollock2004) To manage the experience and impact of side-effects, some respondents minimised, discontinued (Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003, Reference Grime and Pollock2004) or changed their medication (Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) |

| Costs and benefits/weighing and balancing | Individuals continuously evaluated their antipsychotics by weighing and balancing potential benefits (reduction in illness symptoms) against potential risks (side-effects) to achieve ‘wellness’ or ‘sameness’ (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Angermeyer, Löffler and MüllerAngermeyer 2001; Reference UsherUsher 2001; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Those belonging to self-help groups such as MIND, the Hearing Voices Network and the benzodiazepine self-help group TRANX, were more likely to question their medication, particularly given the risk and experience of side-effects (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995; Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998) |

Individuals evaluate the pros of short-term use to provide temporary support and to ‘kick start’ recovery. Few readily accepted the prospect of remaining on tablets long term or indefinitely, but some individuals had to cope with prolonged distress and doubt about the efficacy of the treatment. This resulted in spiralling doubts about stopping and continuing (often equated to concerns about relapse and dependency) and led to widespread uncertainty about their medications (Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003) Concerns about chemical dependency played a key factor in people's assessment of their selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) To manage fears and concerns about psychological dependency, some individuals developed physical and pragmatic arguments for justifying continued medication use (Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) |

| Difficulties in attribution | Attributional difficulties related to not being able to discern symptoms from illness or iatrogenic effects of the medication (Reference UsherUsher 2001; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003, Reference Grime and Pollock2004; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Some individuals were also unsure how to interpret small changes in mental state and were uncertain whether such changes signified normal variation in mood or a recurrence of depression (Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2004) |

Antipsychotics

Concerns among some respondents that some side-effects would be perceived by others as being part of the illness; this contributed to the ways in which attributes are stigmatised (Reference UsherUsher 2001) Antidepressants Difficulties in attribution occurred in response to uncertainty about the effectiveness of medications and whether they were solely responsible for any changes in symptoms or due to psychosocial factors (Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003, Reference Grime and Pollock2004) Many individuals were also unprepared for medication making them feel worse initially. It was only when people were given sufficient information about medication that they felt more able to adhere to a prescribed course and therefore had more confidence in their treatment (Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004) |

| Stopping and seeing what happens | Actively stopping or intending to stop was evident in individuals who experimented with stopping to see what would happen (Reference UsherUsher 2001; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003) Some disparity in information from ‘experts’ about possible withdrawal effects or the general lack of advice and support about how to stop benzodiazepines and antidepressants appropriately (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995; Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) The decision to stop was often fraught with worries about withdrawal effects or the possibility of returning symptoms and potential relapse (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995; Reference Barter and CormackBarter 1996; Reference Knudsen, Hansen and TraulsenKnudsen 2002; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2004; Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004; Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) |

Antipsychotics

Some individuals believed that they would be better off without their medications in terms of the cognitive and social benefits (Reference Angermeyer, Löffler and MüllerAngermeyer 2001) Antidepressants There were those who ‘forgot’ or intentionally stopped (Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003) Some individuals stopped in response to an improvement in symptoms (Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004) Nine respondents temporarily stopped on their doctor's advice (Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) Benzodiazepines For many benzodiazepine users, attempts to withdraw or reduce their medication had been ineffective (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995; Reference Barter and CormackBarter 1996) Stopping was contingent upon knowing that they would be able to sleep and manage distress, and feeling that they could cope (Reference Barter and CormackBarter 1996) Those withdrawing from benzodiazepines were reassured by the knowledge that slow rather than rapid withdrawal was easier (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) |

TABLE 4 Resistance at an individual level: outcomes of evaluation

| Outcome | Similarities | Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Minimisation (dose reduction, drug holidays) | Some individuals purposefully adjusted their antipsychotics experimentally to maximise benefits and minimise unwanted side-effects and psychological distress (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Individuals used minimisation because of specific concerns about minor and severe side-effects of antipsychotics and antidepressants (Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003, Reference Grime and Pollock2004; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004; Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield 2004; Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004) |

Antipsychotics

Minimisation or adjustment to a dosage was a response to a reluctance to accept the diagnosis (Reference UsherUsher 2001) Minimisation was undertaken situationally, e.g. when individuals knew they would be drinking alcohol socially (Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Knowledge acquired about what level of medication was required to control illness and manage side-effects or to treat illness symptomatically (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998) Antidepressants Exerting more control over the medicines by reducing the dose gave individuals a greater stake in managing their illness and treatment (Reference Haslam, Brown and AtkinsonHaslam 2004; Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) Minimisation was used by individuals who discontinued or reduced their dose of antidepressants or who adopted non-pharmaceutical methods to reduce their dependency on medication and to make them feel more comfortable about taking medication (Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield 2004) Benzodiazepines Respondents in the self-help group TRANX were angry and resentful of general practitioners who continued to prescribe high doses (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Refutational findings Minimisation for benzodiazepine users in TRANX who tended to have high or escalating doses over time (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) or when the drugs were not perceived to be strong enough (Reference Barter and CormackBarter 1996) Two-thirds of respondents reported taking antipsychotics as prescribed. Among non-adherents, a small number took extra to maximise their well-being (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998) |

| Resistance despite admonishments, sanctions, coercion |

Antipsychotics

Individuals perceived that the enactment of legal and social sanctions would not only reduce their autonomy but would also jeopardise their access to future care (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Perceived loss of autonomy was exacerbated by the feeling of being under constant surveillance or external control, or being monitored for signs of illness (Reference UsherUsher 2001) Some individuals perceived ‘imposed compliance’ resulting from the pressure to adhere to medication regimens from both medical professionals (Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004), friends and family (Reference UsherUsher 2001) Refutational findings For respondents taking benzodiazepines, it was their general practitioners who had challenged them to reduce or stop taking their medications and it was general practitioners who were resistant to prescribing them (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) |

|

| Non-pharmaceutical options | Non-pharmaceutical options for antipsychotics included music, talking to other people, exercise, praying or religion, complementary and alternative medicine, massage, yoga or relaxation, walking, alcohol, cigarettes, reading and sleep (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Over-the-counter (non-prescription) herbal sleeping tablets were taken prior to course of benzodiazepines (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Alternative ways of coping were preferred because of their lack of side-effects or as a way of ameliorating the side-effects of psychotropics, e.g. using practical strategies such as drinking more to combat dry mouth or using nicotine or caffeine to combat tiredness (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2003; Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Younger, employed people taking anxiolytics increased their exercise, especially walking, to control their anxiety (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) |

Antipsychotics

Another coping strategy was for individuals to consider themselves as ‘experts’ (Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Resources that promoted autonomy (such as money, friends and independent living) were important (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998) Self-medication with street drugs was used to deal with both psychotic symptoms and iatrogenic effects of antipsychotics (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998) Benzodiazepines Two people said that the efficacy of benzodiazepines was increased by a hot milky drink or reading a book (Reference Barter and CormackBarter 1996) For individuals trying to come off benzodiazepines, some had undergone counselling and learnt new skills such as relaxation and stress management to cope with the withdrawal effects (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Refutational findings Some benzodiazepine self-help group members seemed to rely almost exclusively on their medication, without developing other strategies to manage their symptoms (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) |

| Concealment of medication practices | Evidence of individuals altering their antipsychotic and antidepressant doses and regimens without the doctor's consent (Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004; Reference Grime and PollockGrime 2004) |

Antipsychotics

Individuals felt they had to conceal practices such as dose reduction or use of alternatives by not disclosing or by managing the information given to the doctor (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998) |

| Doctor–patient relationships | Provision of information to patients was generally insufficient or confusing because of disparities between general practitioner and specialist advice on length of time for which selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors should be taken (Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004; Reference Verbeek-Heida and MathotVerbeek-Heida 2006) Having more control over decision-making was not necessarily welcomed, e.g. taking more control in their antidepressant medication management resulted in worsening insomnia (Reference Rogers, Day and WilliamsRogers 1998; Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield 2004) |

Antipsychotics

Discordance between patients' lifeworld concerns and professionals' concerns, which were less global and concerned more with reducing symptoms and less with improving life (Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Some doctors were described as good and helpful (Reference Carrick, Mitchell and PowellCarrick 2004) Antidepressants Some respondents reported that initial discussions regarding treatment length affected later decision-making regarding whether or not to continue with their medication (Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield 2004) One individual had specific concerns about being prescribed a dosage far below the minimum recommended dose (Reference Garfield, Francis and SmithGarfield 2004) Benzodiazepines Some doctors moved from a paternalistic to a more patient-centred model, which had consequences for improved symptoms and the experience of adverse side- effects (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Community-based benzodiazepine users had more trusting relationships and were given a high degree of autonomy by their general practitioners (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) People's confidence in the efficacy of benzodiazepines was related to the fact that they had been prescribed; people's trust in their doctor was closely associated with their trust in their medication (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Disharmony in the doctor–patient relationship generally stemmed from people's concerns about their medications (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Continuity of prescriber positively affected the doctor–patient relationship (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Members of the benzodiazepine self-help group tended to be more resentful and angry, and many had experienced difficulties when the original prescriber had retired, died or moved (Reference North, Davis and PowellNorth 1995) Owing to the ‘unseen’ repeat-prescribing system, individuals did not know what their doctor thought of their use of sleeping tablets (Reference Barter and CormackBarter 1996) |

FIG 1 Model of medicine-taking (Reference Pound, Britten and MorganPound 2005).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Richard Laugharne and Dr Andrew Whitaker for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article and for assistance with devising the MCQs.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.