Dementia, or major neurocognitive disorder, is a progressive disorder with cognitive decline from a prior level of functioning in one or more cognitive domains that interferes with independence in everyday activities, including occupational, domestic or social functioning. Reference Moga, Roberts and Jicha1,Reference Gale, Acar and Daffner2 There may be accompanying psychiatric or behavioural features such as paranoia, delusions, visual hallucinations, apathy, wandering and/or hoarding in some neurocognitive disorders. Reference Moga, Roberts and Jicha1–Reference Sorbi, Hort, Erkinjuntti, Fladby, Gainotti and Gurvit3 On the other hand, individuals suffering from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may have cognitive decline from a prior level of functioning in one or more cognitive domains, but the decline does not interfere with independence in activities of daily living. Reference Petersen, Lopez, Armstrong, Getchius, Ganguli and Gloss4,Reference Tangalos and Petersen5 The reported global prevalence is about 1–2% of patients at age 65 and 30% at age 85. Reference Moga, Roberts and Jicha1,Reference Gale, Acar and Daffner2 With the increasing geriatric population, age (particularly age >65 years) is the strongest risk factor for dementia. Reference Moga, Roberts and Jicha1,Reference Gale, Acar and Daffner2 The number of patients with dementia is expected to reach 152 million worldwide in 2050. Reference Livingston, Huntley, Sommerlad, Ames, Ballard and Banerjee6 Other risk factors include family history, chronic conditions (such as hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease) and unhealthy lifestyles (such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption and sedentary behaviour). Reference Moga, Roberts and Jicha1,Reference Gale, Acar and Daffner2 Although some treatment options could improve cognition status, there is still no cure for progressing cognitive disorders (such as Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia); therefore, early identification is vital for preventing and treating dementia. Reference Sorbi, Hort, Erkinjuntti, Fladby, Gainotti and Gurvit3,Reference Petersen, Lopez, Armstrong, Getchius, Ganguli and Gloss4

Behavioural and psychological symptoms (BPSs) are a common syndrome in patients with dementia, characterised by disturbances in perception, thoughts, emotions or behaviour, although they sometimes may manifest as impairments in non-cognitive domains. Reference Sorbi, Hort, Erkinjuntti, Fladby, Gainotti and Gurvit3,Reference Petersen, Lopez, Armstrong, Getchius, Ganguli and Gloss4,Reference Mega, Cummings, Fiorello and Gornbein7 BPSs are closely associated with adverse outcomes such as caregiver burden, Reference Gilley, Bienias, Wilson, Bennett, Beck and Evans8,Reference Gaugler, Edwards, Femia, Zarit, Stephens and Townsend9 admittance to hospital Reference Feast, Orrell, Charlesworth, Melunsky, Poland and Moniz-Cook10,Reference Terum, Andersen, Rongve, Aarsland, Svendsboe and Testad11 and increased mortality. Reference Wilson, Tang, Aggarwal, Gilley, McCann and Bienias12 The available literature suggests that the incidence rate of BPSs may vary in different cognitive functioning states. Mortby et al Reference Mortby, Lyketsos, Geda and Ismail13 found the morbidity rate of at least one BPS to be 80% in the dementia population, 53.4% in MCI and 30.8% in the cognitively unimpaired population. Geda et al Reference Geda, Roberts, Knopman, Petersen, Christianson and Pankratz14 found that approximately 51% of patients with MCI had at least one neuropsychiatric symptom, while the rate was 27% among those with normal cognition. Nevertheless, studies regarding BPSs in the Chinese population are scarce in number. Also, for patients who actively seek treatment with BPS complaints, if their cognitive impairment is not severe to a self-evident level, their cognitive impairment may be underestimated.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the BPSs at different cognitive functions and compare the characteristics of BPSs in patients with different degrees of cognitive impairment.

Method

Study design and patients

This cross-sectional study enrolled consecutive patients at the cognitive assessment out-patient clinic of our hospital between January 2018 and October 2022. The inclusion criteria were (a) conscious, capable of reading and had no barriers to communication with the investigators, and (b) willing to participate in this study after informed consent. The exclusion criteria were (a) patients with severe lalopathy, hearing disorder or a visual impairment, or (b) patients with severe diseases such as the acute phase of cerebral infarction, cerebral haemorrhage, acute coronary syndrome, acute heart failure, etc., or acute phase of chronic diseases such as acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The ethics committee of Tongji Hospital of Tongji University approved this project (2021-LCYJ-002-1). The enrolled patients were informed of the study’s purpose and signed the informed consent form. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, as well as relevant local guidelines.

Data collection

The study collected general demographic and clinical data, including age, gender, education years, height, body weight, body mass index (BMI), smoking, alcohol consumption, past medical history of hyperlipidaemia, anaemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction, brain trauma, carbon monoxide poisoning, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, general surgical anaesthesia and family history of dementia.

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) Reference Cummings15,Reference Kaufer, Cummings, Ketchel, Smith, MacMillan and Shelley16 was used to assess the patients’ BPSs of dementia; in the present study, participants could choose to complete the questionnaire by themself or with the help of caregivers. The questionnaire was self-administered or provided by the caregiver for the manifestation of 12 psychiatric and behavioural symptoms, namely delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, psychomotor alterations, sleep change and appetite change. The evaluation indicators included frequency (0–4 points) and severity (0–3 points) of each BPS, and the total Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) score was the sum of the product of frequency and severity in each item. BPSs were positive when the score was >0 in relevant NPI items. The higher the NPI score, the more pronounced the BPSs were. Reference Nunes, Schwarzer, Leite, Ferretti-Rebustini, Pasqualucci and Nitrini17

The revised version of the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale proposed by Lawton and Brody Reference Lawton and Brody18 was used to assess patients’ ability to perform both basic activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. This scale of the Physical Self-Maintenance Scale (PSMS, including going to the toilet, eating, dressing, grooming, walking and bathing) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL, including talking on the phone, shopping, preparing meals, doing housework, laundry, using transportation, taking medication and managing finances), and covered a total of 14 categories. Reference Lawton and Brody18 Each aspect is scored according to what the patients (a) can independently accomplish, (b) can accomplish with some difficulty, (c) require assistance to accomplish and (d) are incapable of accomplishing, with a total score of 14–56. A total score of ≥22 is considered significant ADL dysfunction, and the higher the total score, the worse the dysfunction.

The Chinese version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic (MoCA-B) Reference Chen, Xu, Chu, Ding, Liang and Nasreddine19 was used to assess cognitive function. The MoCA-B assesses cognitive function through indicators in the following cognitive domains: executive function, language, orientation, computation, abstract thinking, memory, visual perception (but not visual structure skills), attention and concentration. A dividing points for the MCI are at 19/20, 22/23 and 24/25 for receiving less than 6, between 6 and 12, and more than 12 years of education.

Based on the ADL and MoCA-B scores, the participants were classified into the cognitively unimpaired group, MCI group or dementia group. Participants were classified as cognitively unimpaired when MoCA-B performance was above the MCI standard. The diagnostic criteria for the MCI referred to the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia and Cognitive Impairment 2018: (a) patients complained of significant memory deterioration or memory impairment; (b) objective evidence of cognitive impairment was found by the MoCA-B score; (c) unimpaired or slight impairment in activities of daily living but maintaining independent activities of daily living (<22); (d) does not meet the diagnosis criteria of dementia. The diagnostic criteria for dementia referred to DSM-5 20 for the diagnosis of dementia, with the MoCA-B scores indicating a decline in cognitive function and the ADL scale indicating significant dysfunction in activities of daily living.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows 10 was used to analyse the data. The continuous data with a normal distribution were expressed as means ± standard deviations. The continuous data with a non-normal distribution were expressed as a median (P25, P75). The categorical data were expressed as n (%). If continuous variables met the normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed; otherwise, a rank sum test was performed. The grouped data were compared using the χ2 test, and Bonferroni adjustment was used for multiple comparisons among groups for those with P < 0.05 for the ANOVA. Stepwise unordered logistic regression was used to analyse the relationship between BPSs and cognitive impairment. The cognitively unimpaired group was the reference for the unordered logistics regression analysis. Model 1: adjustment for age, education years, BMI, alcohol consumption, past medical history of hypertension, general surgical anaesthesia, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction and coronary heart disease. Model 2: all BPSs were included based on Model 1 with mutual adjustment. Two-sided P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

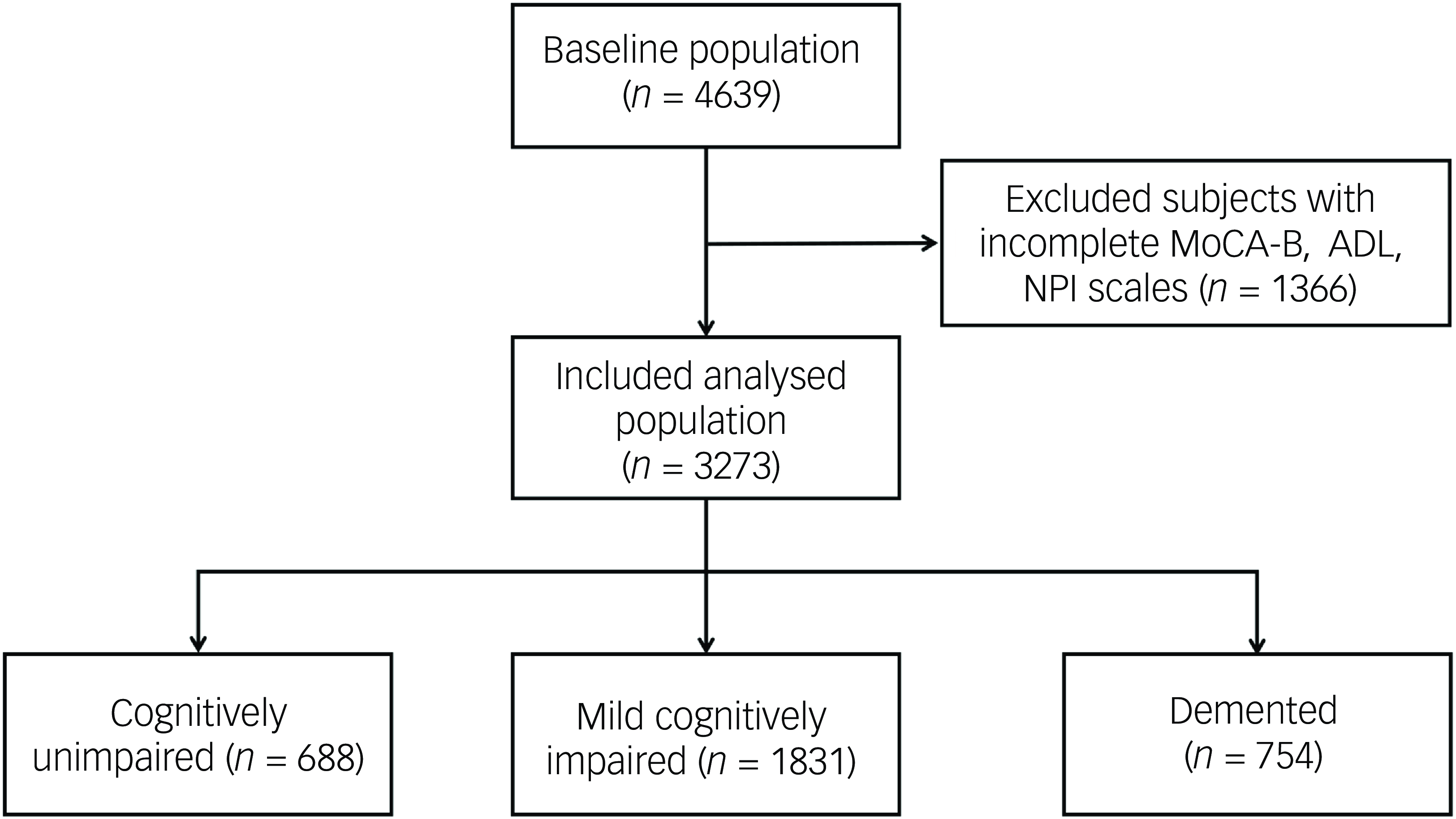

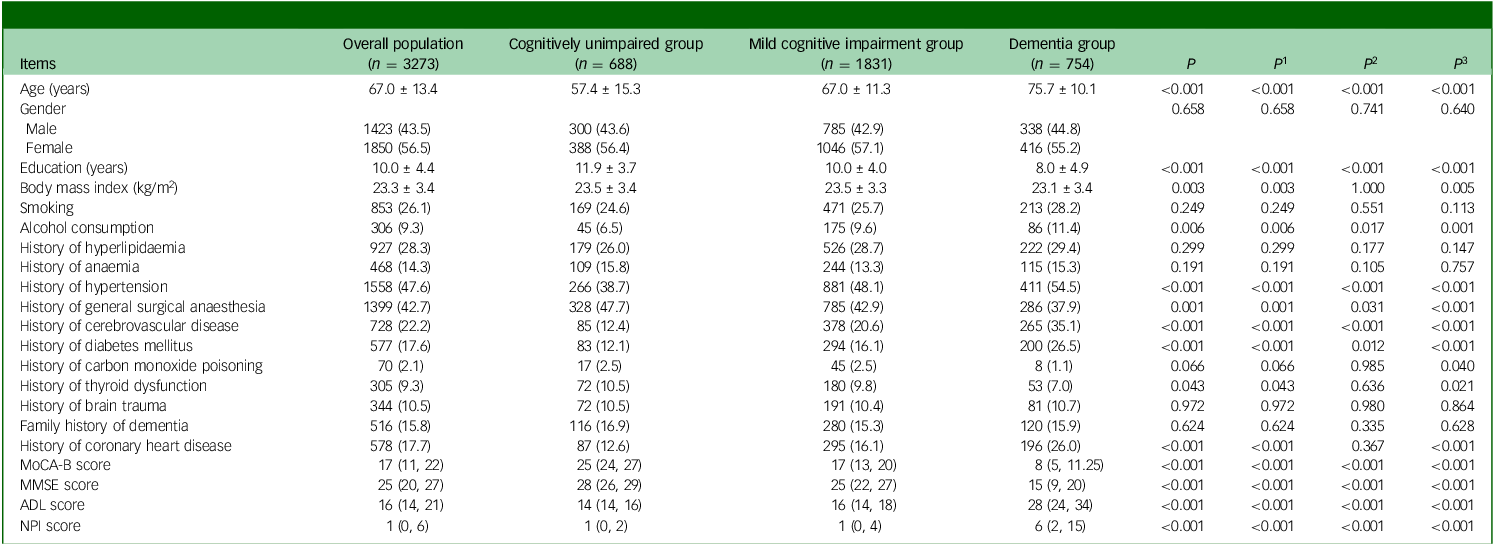

This study recruited 4639 consecutive out-patients who attended the cognitive assessment out-patient clinic, of which 1366 patients were excluded because of incomplete information on the MoCA-B, ADL or NPI scales. Finally, 3273 patients were included. Among them, 688 (21%) were identified as cognitively unimpaired, 1831 (56%) were identified as suffering from MCI and 754 (23%) had dementia (Fig. 1). The mean age of the patients was 67.0 ± 13.4 years, the mean education was 10.0 ± 4.4 years and 1423 (43.5%) were males. Age, education received, BMI, alcohol consumption, past medical history of hypertension, general anaesthesia, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction, coronary heart disease, MoCA-B score, Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE) score, ADL score and NPI score were significantly different among the three groups (all P < 0.05). Results showed that patients with lower cognitive function exhibited higher age and higher rates of hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease, while education decreased (all P < 0.017) (Table 1). The NPI score [1 (0, 2) v. 1 (0, 4) v. 6 (2, 15), P < 0.001], the percentage of the patients with BPSs [53.5% v. 59.6% v. 86.1%, P < 0.001] and the number of BPSs [1 (0, 2) v. 1 (0, 2) v. 3 (1, 5), P < 0.001] were also higher in patients with decreased cognitive level.

Fig. 1 Flowchart. MoCA-B, Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics

MoCA-B, Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic; MMSE: Mini-mental State Examination scale; ADL: Activities of Daily Living scale; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; P, comparison between the rates of the three groups: cognitively unimpaired group, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) group and dementia group; P 1–3, comparisons between any two means, P 1, value corresponding to MCI group versus cognitively unimpaired group; P 2, P-value corresponding to dementia group versus cognitively unimpaired group; P 3, P-value corresponding to dementia group versus MCI group.

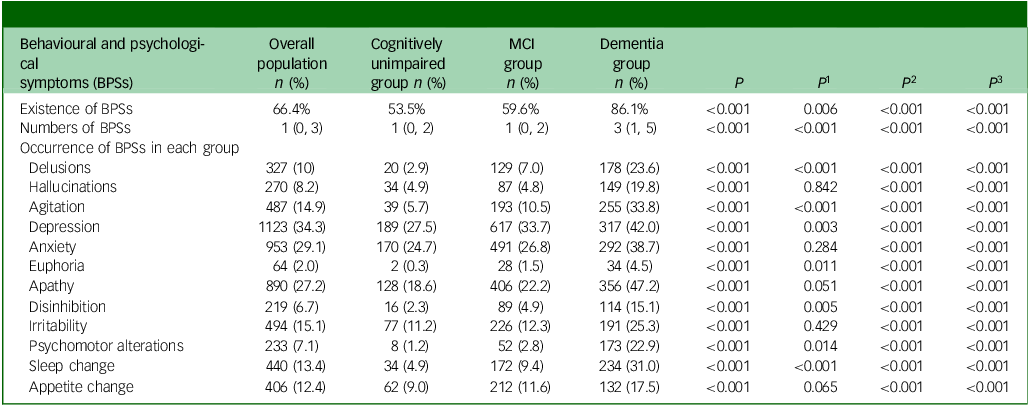

The dominant BPSs were depression (34.3%), anxiety (29.1%) and apathy (27.2%). Compared with the cognitively unimpaired, the MCI group presented with higher incidence of delusions (2.9% v. 7.0%), agitation (5.7% v. 10.5%), depression (27.5% v. 33.7%), euphoria (0.3% v. 1.5%), disinhibition (2.3% v. 4.9%), psychomotor alterations (1.2% v. 2.8%) and sleep change (4.9% v. 9.4%) (all P < 0.05). All BPSs in patients with dementia were significantly more frequent than in the cognitively unimpaired and MCI groups (all P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of the occurrence of behavioural and psychological symptoms

MCI, mild cognitive impairment; P, comparison between the rates of the three groups: cognitively unimpaired group, MCI group and dementia group; P 1–3, comparisons between any two means; P 1, value corresponding to MCI group versus cognitively unimpaired group; P 2, P-value corresponding to dementia group versus cognitively unimpaired group; P 3, P-value corresponding to dementia group versus MCI group.

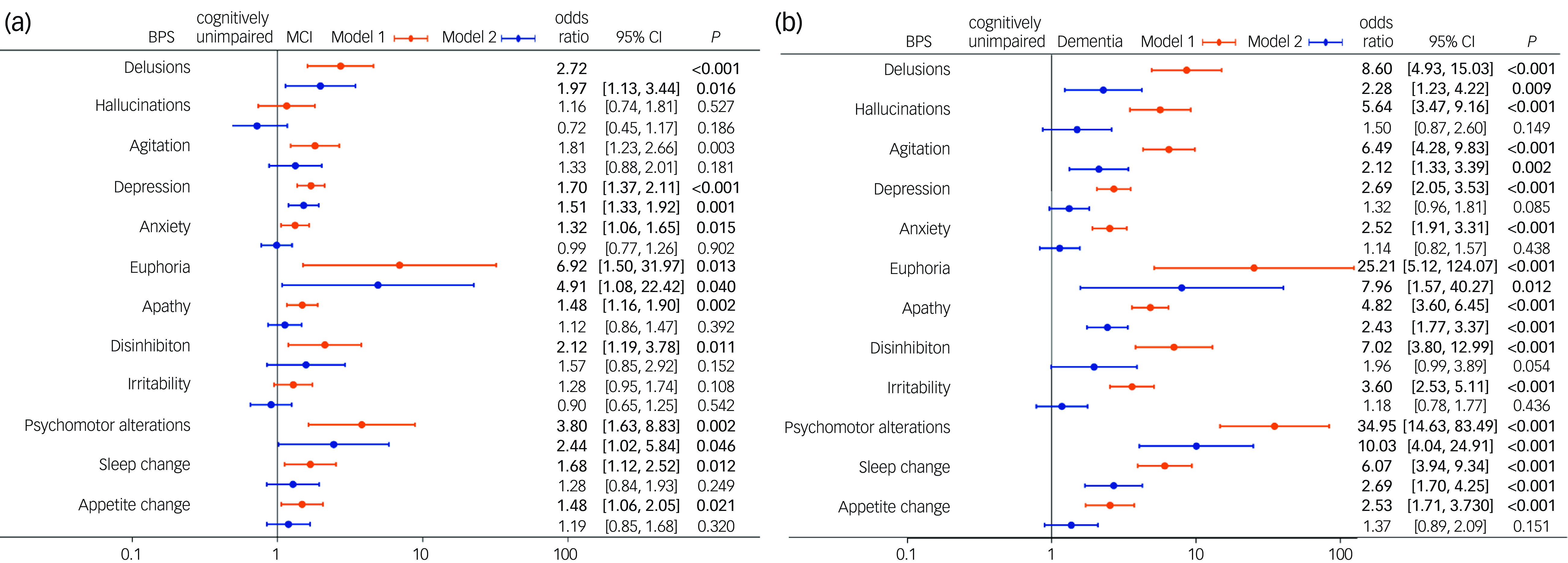

Unordered logistic regression analysis showed that, after adjustment for age, education years, BMI, alcohol consumption, past medical history of hypertension, general surgical anaesthesia, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction and coronary heart disease, delusions (odds ratio = 2.72, 95%CI: 1.61, 4.59, P < 0.001), agitation (odds ratio = 1.81, 95%CI: 1.23, 2.66, = 0.003), depression (odds ratio = 1.70, 95%CI: 1.37, 2.11, P < 0.001), anxiety (odds ratio = 1.32, 95%CI: 1.06, 1.65, P = 0.015), euphoria (odds ratio = 6.92, 95%CI: 1.50, 31.97, P = 0.013), apathy (odds ratio = 1.48, 95%CI: 1.16, 1.89, P = 0.002), disinhibition (odds ratio = 2.12, 95%CI: 1.19, 3.78, P = 0.011), psychomotor alterations (odds ratio = 3.80, 95%CI: 1.63, 8.83, P = 0.002), sleep change (odds ratio = 1.68, 95%CI: 1.12, 2.52, P = 0.012) and appetite change (odds ratio = 1.48, 95%CI: 1.06. 2.05, P = 0.021) were associated with MCI (based on Model 1) (Fig. 2(a)). All 12 BPSs were associated with dementia based on Model 1 (all P < 0.001) (Fig. 2(b)).

Fig. 2 Forest plot of factors associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia. (a) Forest plot of factors associated with MCI. (b) Forest plot of factors associated with dementia. BPS, behavioural and psychological symptoms. Model 1: adjustment for age, education years, body mass index, alcohol consumption, past medical history of hypertension, general surgical anaesthesia, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction and coronary heart disease. Model 2: all BPSs were included based on Model 1 with mutual adjustment.

After adjustment for the interaction effect of BPSs, delusions (odds ratio = 1.97, 95%CI: 1.13, 3.44, P = 0.016), depression (odds ratio = 1.51, 95%CI: 1.2, 1.92, P = 0.001), euphoria (odds ratio = 4.91, 95%CI: 1.08, 22.42, P = 0.04) and psychomotor alterations (odds ratio = 2.44, 95%CI: 1.02, 5.84, P = 0.046) were independently associated with MCI (Model 2) (Fig. 2(a)). Delusions (odds ratio = 2.28, 95%CI: 1.23, 4.21, P = 0.009), agitation (odds ratio = 2.12, 95%CI: 1.33, 3.39, P = 0.002), euphoria (odds ratio = 7.96, 95%CI: 1.57, 40.27, P = 0.012), apathy (odds ratio = 2.43, 95%CI: 1.76, 3.37, P < 0.001), psychomotor alterations (odds ratio = 34.95, 95%CI: 14.63, 83.49, P < 0.001) and sleep change (odds ratio = 2.69, 95%CI: 1.70, 4.25, P < 0.001) were independently associated with dementia (Model 2) (Fig. 2(b)).

Discussion

The results suggest that NPI scores, percentage of patients with BPSs and the number of BPSs increased significantly with declining cognitive function. Delusions, depression, euphoria and psychomotor alterations were independently associated with MCI. Delusions, agitation, euphoria, apathy, psychomotor alterations and sleep change were independently associated with dementia.

The prevalence rate of cognitive impairment in this study was 79.1%, higher than the previous prevalence rate found in the domestic community or elderly in-patient population Reference Bickel, Heßler, Junge, Leonhardt-Achilles, Weber and Schäufele21,Reference Chen, Cai, Bai, Su, Tang and Ungvari22 ; however, because of the large sample size in our cohort, there were still 600 patients who exhibited cognitively unimpaired behaviour for further analysis. The high prevalence of cognitive impairment in our patients may be related to the fact that many patients who actively seek assessment in the cognitive out-patient clinic had already developed related symptoms severe enough for consideration of dementia and were referred for evaluation, resulting in a higher frequency of cognitive impairment in our data-sets. Among the different cognitive functions, there were differences between groups in socioeconomic and clinical status; the more risk factors, the more severe the impairment of cerebral function, and the higher the risk of cognitive impairment, as suggested by previous studies. Reference Luo, Murray, Guo, Tian, Ye and Li23–Reference Martinez-Horta, Bejr-Kasem, Horta-Barba, Pascual-Sedano, Santos-Garcia and de Deus-Fonticoba25 Education level is another important factor in association with cognitive function. Bell et al Reference Bell, John and Gaysina26 highlighted that higher cognitive ability and educational level were associated with better affective function, while Lövdén Reference Lövdén, Fratiglioni, Glymour, Lindenberger and Tucker-Drob27 showed educational attainment has positive effects on cognitive function and, in our study, patients who were cognitively unimpaired received significantly longer education.

With ageing and gradual cognitive decline, various types of BPSs are likely to occur, and the change in the number of BPSs showed a similar tendency to the change with age. In the present study, the percentages of patients with at least one BPS manifestation were 59.6% and 86.1% in the MCI and dementia groups, respectively. Mortby et al Reference Mortby, Burns, Eramudugolla, Ismail and Anstey28 conducted a study on the cognitive function of 1417 community older adults and found that the percentages of patients with MCI and dementia with at least one type of BPS were 53.4% and 80%, respectively, both of which were lower than in this study, which may be related to the different diagnostic procedure and study population.

In previous studies, an estimated 12.8–66.0% of individuals with MCI exhibit some type of BPS, with depression (median prevalence of 29.8%), sleep disturbances (median prevalence of 18.3%) and apathy (median prevalence of 15.2%) being the most prevalent, Reference Köhler, Magalhaes, Oliveira, Alves, Knochel and Oertel-Knöchel29 while in the present study, the most frequent three BPSs were depression (34.3%), anxiety (29.1%) and apathy (27.2%), each of which may become more pronounced as emotion regulation capacity worsens when dementia worsens. Reference Kim, Noh and Kim30 According to the sub-syndromes defined by European Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium, Reference Xu, Ang, Hilal, Chan, Wong and Venketasubramanian31 depression and anxiety are classified into affective symptoms, and therefore the results in our study indicated the importance of affective symptoms worsening, which showed the highest prevalence in our cohort. Reference Jang, Ho, Blanken, Dutt and Nation32 As for apathy, which belonged to the apathy sub-syndrome, Malpetti et al Reference Malpetti, Jones, Tsvetanov, Rittman, van Swieten and Borroni33 found it was an early marker of frontotemporal dementia and could be used to predict cognitive function deterioration, even before dementia onset, which also suggested that a close monitor of the patients in our cohort is necessitated. For another two sub-syndromes (hyperactivity: agitation, euphoria, disinhibition, irritability and aberrant motor behaviours; psychosis: delusions, hallucinations and sleep change), although these symptoms did not have as high prevalence as depression, anxiety and apathy, there were still significant differences in prevalence for all these symptoms among the cognitively unimpaired, MCI and dementia groups. In addition, a certain percentage of patients in the cognitively unimpaired group had more severe BPSs, such as hallucinations, delusions, disinhibition, etc., which may be associated with the fact that all of the participants in this study were attending a neurologist/psychiatric out-patient clinic.

The adjusted regression analysis in this study showed that depression (P = 0.003) and euphoria (P = 0.011) were independently associated with MCI compared with the cognitively unimpaired group. In addition, delusions, agitation, depression, apathy, disinhibition, psychomotor alterations and sleep change were independently associated with dementia. This result is in alignment with the study performed by Onofrj et al Reference Onofrj, Espay, Bonanni, Delli Pizzi and Sensi34 , who found that delusion frequency could increase with the dementia disease progression, while Sano et al Reference Sano, Zhu, Neugroschl, Grossman, Schimming and Aloysi35 proved that agitation is associated with the degree of functional disability and poorer cognitive scores. These findings were also consistent with the fact that cognitive impairment severity is associated with higher numbers and more severe BPSs; from the sub-symptoms perspective, the effect of declined cognitive function on BPSs was widespread and, although not all BPSs exhibited a significant association, all NPI sub-syndromes (hyperactivity, psychosis, apathy and affective symptoms) were affected. Xu et al Reference Xu, Ang, Hilal, Chan, Wong and Venketasubramanian31 found similar results in 613 Chinese people aged >60 years living in Singapore; the incidence rate of two or more BPSs in different cognitive states was lower than in the present study, where the majority of patients were community-dwelling older adults, that is, a relatively healthy group compared with patients with multiple visits to the out-patient clinic, which may be associated with a lower rate of BPSs.

This study had some limitations. First, this study used a cross-sectional design, which prevents causality determination. Second, the study enrolled only out-patients in the neurology department, which might introduce some bias because these patients were referred for a cognitive evaluation. Third, the patients were from a single hospital, limiting the sample size and generalisability. Finally, the results of this study could be affected by different criteria of diagnosis. In the future, there is a need to expand the sample size and conduct relevant longitudinal studies to analyse the contribution of psychiatric and behavioural symptoms in the risk development of cognitive decline and dementia.

In conclusion, BPSs have a high incidence rate in out-patients with cognitive impairment. The NPI scores, BPS incidence and the numbers of BPSs increased significantly with declining cognitive function. All BPSs were significantly different among the three cognitive level groups. Partial BPSs increase the risk of cognitive impairment and should be taken seriously.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the help of Professor Yunxia Li and Professor Lingjing Jin’s project team for providing database support.

Author contributions

Y.L. and J.H. carried out the studies, participated in collecting data and drafted the manuscript. Y.Z., R.L. and Y.L performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. W.M., S.W. and X.L. participated in the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82271586, 82200970), the National Key R & D Program of China (2023YFC3604501), the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission of Science Foundation (20234Y0156, 202440024), the Database Project of Tongji Hospital of Tongji University (TJ(DB)2102) and the Clinical Research Project of Tongji Hospital of Tongji University (ITJ(ZD)2002-1, ITJ(QN)2213).

Declaration of interest

None.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human participants/patients were approved by the ethics committee of Tongji Hospital of Tongji University approved this project (2021-LCYJ-002-1). The enrolled patients were informed of the study’s purpose and signed the informed consent form.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.