Background

Problem drinking is a pervasive global mental health problem that accounts for 9.6% of disability-adjusted life years worldwide (Whiteford et al. Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari, Erskine, Charlson, Norman, Flaxman, Johns, Burstein, Murray and Vos2013). Problem drinking, an umbrella-term encompassing varying levels of harmful alcohol patterns including dependence/abuse, disproportionally impacts men (Grittner et al. Reference Grittner, Kuntsche, Graham and Bloomfield2012; Probst et al. Reference Probst, Roerecke, Behrendt and Rehm2015) and has negative psychological, social, behavioral, and physical consequences (Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Mathers, Popova, Thavorncharoensap, Teerawattananon and Patra2009, Reference Rehm, Baliunas, Borges, Graham, Irving, Kehoe, Parry, Patra, Popova, Poznyak, Roerecke, Room, Samokhvalov and Taylor2010; Steel et al. Reference Steel, Marnane, Iranpour, Chey, Jackson, Patel and Silove2014). Alcohol consumption above moderate levels and risky drinking patterns lead to a number of physical ailments, such as liver cirrhosis, heart failure, and certain cancers (Boffetta & Hashibe, Reference Boffetta and Hashibe2006; Laonigro et al. Reference Laonigro, Correale, Di Biase and Altomare2009; Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, Teo, Rangarajan, O'Donnell, Zhang, Rana, Leong, Dagenais, Seron, Rosengren, ESchutte, Lopez-Jaramillo, Oguz, Chifamba, Diaz, Lear, Avezum, Kumar, Mohan, Szuba, Wei, Yang, Jian, McKee and Yusuf2015). Psychologically, for men reporting problem drinking, co-morbid mental health issues, such as depression, anxiety, and externalizing problems, are common and often exacerbate alcohol-related consequences (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Ormel, Petukhova, Mclaughlin, Green, Russo, Stein, Zaslavsky, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, de Girolamo, de Graaf, Demyttenaere, Fayyad, Haro, yi Hu, Karam, Lee, Lepine, Matchsinger, Mihaescu-Pintia, Posada-Villa, Sagar and Bedirhan Üstün2011; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Waldron, Sartor, Scherrer, Duncan, Mccutcheon, Haber, Jacob, Heath and Bucholz2015).

Consequences of men's drinking often extend beyond the individual to impact their families (Solis et al. Reference Solis, Shadur, Burns and Hussong2012). The ecological-transactional model is a helpful framework for examining effects of male drinking across family systems while also accounting for powerful and dynamic societal influences (Sameroff, Reference Sameroff1975; Cicchetti & Lynch, Reference Cicchetti and Lynch1993; Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1994). This model may be especially helpful for examining and disentangling consequences of male alcohol use in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), given that it emphasizes the importance of cultural and contextual factors, specifically including economic factors, that impact the nature and manifestation of alcohol-related outcomes.

For men, drinking has a documented cascade of consequences on the family with clear links to negative child outcomes, partner relationship difficulties, and disrupted family systems (Leonard & Eiden, Reference Leonard and Eiden2007). At the child-level, direct relationships have been found between male caregiver problem drinking and youth substance abuse, internalizing and externalizing problems, and poor health (Keller et al. Reference Keller, El-Sheikh, Keiley and Liao2009; Atilola et al. Reference Atilola, Stevanovic, Balhara, Avicenna, Kandemir, Knez, Petrov, Franic and Vostanis2014). Within the caregiver-child subsystem, alcohol abuse influences the likelihood of child maltreatment, harsh parenting, lack of paternal sensitivity and warmth, and decreased cognitive stimulation in the home (Keller et al. Reference Keller, El-Sheikh, Keiley and Liao2009; Meinck et al. Reference Meinck, Cluver, Boyes and Mhlongo2015). Deficits in parenting strategies may be due in part to the impact of drinking on the father's mental health, including poor emotion regulation or blunted affect, psychosocial stressors associated with drinking, and preoccupation with drug-seeking behavior (Neger & Prinz, Reference Neger and Prinz2015). At the couple level, intimate partner violence (IPV), marital conflict, poor communication, and poor co-parenting are all associated with men's alcohol use as shown across both high-income countries (HICs) and LMICs (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Dunkle, Nduna, Jama and Puren2010; Garcia-Moreno & Watts, Reference Garcia-Moreno and Watts2011; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Nunes, Bean, Day, Falceto, Hollist and Fernandes2014). Across the family system, longitudinal pathways have been documented in HICs: paternal drinking to marital conflict to child maltreatment; and paternal drinking to IPV to children's witnessing of IPV to poor child adjustment (Leonard & Eiden, Reference Leonard and Eiden2007).

Importance of research in LMICs

The nature, severity, and extent of the negative effects of male alcohol use are related to the context in which they occur. Yet, since the majority of research is conducted in HICs, we know very little about the influence of broader ecological factors on alcohol use in lower resourced parts of the world. Across LMICs, the most obvious common factor is high-rates of poverty that are associated with worsened individual and family consequences of alcohol use (Grittner et al. Reference Grittner, Kuntsche, Graham and Bloomfield2012). Consistent with this, across LMICs complex relationships exist between alcohol use, disease burden, and economic development, such that rates of consumption across LMICs are lower when compared of HICs, but the unit of disability per liter consumed is higher in LMICs and highest among those with the fewest resources (Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Mathers, Popova, Thavorncharoensap, Teerawattananon and Patra2009; WHO, 2014).

Additionally, specific cultural norms related to gendered power dynamics and masculinity can wield strong influences on alcohol-related consequences within individuals and across relational systems. Patriarchal norms that place men in positions of power have been associated with higher levels of men's alcohol use and negative consequences for men, women, children, and family systems (Barker et al. Reference Barker, Ricardo and Nascimento2007). For men, these hegemonic norms are associated with increased violence, delinquency, poorer mental health, reduced help and health-seeking behavior, and increased mortality (Garfield et al. Reference Garfield, Isacco and Rogers2008; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ho, Wang and Miller2016). At the family level, associations between IPV and men's drinking are perpetuated in patriarchal climates, worsening as inequality and hegemonic norms increase (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Flood and Lang2015; Wachter et al. Reference Wachter, Horn, Friis, Falb, Ward, Apio, Wanjiku and Puffer2017). Gender inequities can further impact children directly and through IPV (Garrido et al. Reference Garrido, Culhane, Petrenko and Taussig2011), as they are associated with child maltreatment, poor/absent parent involvement, and intergenerational transmission of violence (Kato-Wallace et al. Reference Kato-Wallace, Barker, Eads and Levtov2014; Guedes et al. Reference Guedes, Bott, Garcia-Moreno and Colombini2016). In sum, considering, or even explicitly addressing cultural norms, may influence the effectiveness of interventions with particular people in particular places.

Existing evidence-based treatments

In both HIC and LMICs effective interventions for alcohol abuse exist, such as Motivational Interviewing and pharmacological treatments (Patel et al. Reference Patel, Araya, Chatterjee, Chisholm, Cohen, De Silva, Hosman, Mcguire, Rojas and van Ommeren2007). Likewise, interventions exist to address problems related to dysfunctional family systems at multiple levels. Interventions such as multi-systemic therapy, functional family therapy, brief solution-focused therapy, and emotion-focused therapy address the family system as a whole (Sexton & Datchi, Reference Sexton and Datchi2014). At the couple's level, behavioral, systemic, experiential, and emotion-focused approaches have gained strong evidence (Gurman et al. Reference Gurman, Lebow and Snyder2015). Targeting parent-child relationships are multiple evidence-based interventions focused primarily on parental skills training in relationship enhancement and behavioral management (Eyberg et al. Reference Eyberg, Nelson and Boggs2008; Webster-Stratton et al. Reference Webster-Stratton, Jamila Reid and Stoolmiller2008; Sanders, Reference Sanders2012; Barkley, Reference Barkley2013; Furlong et al Reference Furlong, McGilloway, Bywater, Hutchings, Smith and Donnelly2012); some of these also have a growing evidence base in LMICs (Mejia et al. Reference Mejia, Calam and Sanders2012; Knerr et al. Reference Knerr, Gardner and Cluver2013).

In HICs, there are also emerging treatments addressing both family-level relationship needs and drinking (Powers, et al. Reference Powers, Vedel and Emmelkamp2008; Neger & Prinz, Reference Neger and Prinz2015). Combined treatments include programs aimed at improving alcohol abuse outcomes through family or couples therapy (Fals-Stewart et al. Reference Fals-Stewart, O'Farrell and Birchler2004). Other programs include those that treat at the individual level but include content that also targets family-related outcomes, such as integrated IPV and alcohol use programs with individual men (Kraanen et al. Reference Kraanen, Vedel, Scholing and Emmelkamp2013). One particularly notable intervention is Alcoholic Behavioral Couples Therapy (ABCT), which targets the intersection of alcohol-use and couple-level conflict. ABCT posits that alcohol use contributes to relationship dysfunction, and that those problems, in turn, exacerbate alcohol use, creating a persistent negative cycle (Fals-Stewart et al. Reference Fals-Stewart, O'Farrell and Birchler2004). A meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials documented effects of ABCT on alcohol consumption frequency (d = 0.45) and marital satisfaction (d = 0.51) compared with control conditions and individual cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Powers et al. Reference Powers, Vedel and Emmelkamp2008). ABCT has also been associated with decreases in externalizing problems among children whose fathers reduced alcohol use (Andreas & O'Farrell, Reference Andreas and O'Farrell2009).

Further, some alcohol-focused interventions in HICs have begun to integrate strategies to mitigate harmful parenting practices often associated with parental alcohol-abuse (Messina et al. Reference Messina, Calhoun, Conner and Miller2015; Neger & Prinz, Reference Neger and Prinz2015). These treatments have shown both reductions in alcohol use and improved parenting (Harnett & Dawe, Reference Harnett and Dawe2008). As one example from the USA, ABCT combined with parenting skills was associated with improved individual alcohol misuse, systemic family relationships, and child adjustment (Lam et al. Reference Lam, Fals-Stewart and Kelley2009). Another intervention combining individual CBT, couples therapy, and restorative parenting sessions targeted men's alcohol-use, IPV, and parenting in a pilot trial with positive results (Stover, Reference Stover2015).

Although results are promising, research on combined alcohol use and family interventions is moving forward primarily in HICs, and the need to expand to LMICs is clear. It is important to identify intervention trials in LMIC settings in which alcohol and family outcomes have both been measured. Knowing the limited nature of that work, it is then important also to identify intervention trials in LMIC settings in which these have been assessed even as secondary outcomes. Examining that literature may uncover that some of the evidence-based behavior change intervention strategies already adapted for use in LMICs may improve alcohol and family outcomes even if alcohol and family behavior changes are not the primary behavioral targets. Given the overlap between behavioral intervention strategies for a wide array of behaviors, it is likely that multiple behaviors may change at once despite a focus on specific content.

One reason that this strategy for literature review is important before deciding whether to replicate programs from HICs is the need for cultural and contextual adaptations for LMICs that may already have been done successfully for interventions being implemented in these contexts. The process of cultural adaptation – modifying interventions to address issues in contextually-relevant and meaningful ways to increase treatment viability – can range from surface level modifications to deep adaptation with the ultimate goal of increasing treatment effectiveness (Bernal et al. Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009; Barrera et al. Reference Barrera, Castro, Strycker and Toobert2013). According to the framework proposed by Bernal et al. (Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995), adaptations can fall across the following domains: language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context. Though there is a debate in the field regarding the necessary level of adaptation, there seems to be a consensus that some level of adaptation beyond translation is associated with more positive outcomes (Barrera et al. Reference Barrera, Castro, Strycker and Toobert2013; Chowdhary et al. Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans, Rahman, Verdeli, Araya and Patel2014).

Aims

In this paper, we systematically review interventions conducted in LMICs that measured both men's alcohol use and at least one family outcome as either primary or secondary to identify intervention strategies implemented in LMICs associated with changes in these domains. We then explore common characteristics among interventions that improved male drinking and relationship-based family outcomes and describe the strategies and implementation methods. Lastly, we aim to identify limitations in the literature and opportunities for future clinical research.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

-

(1) Described any intervention evaluation examining at least one alcohol-use outcome for men and at least one family-related outcome; family-related was defined as any relationship-based family variable (e.g., parenting, IPV, communication, family functioning).

-

(2) Evaluated an intervention implemented in a LMIC, as defined by the World Bank (The World Bank Group, 2016),

-

(3) Included a pre- and post-quantitative assessment of outcomes.

Exclusion criteria

Studies with only women were excluded; studies with a sample that included male participants all younger than 18 or all older than 65 were also excluded. Additionally, unpublished studies, studies unavailable in English, qualitative studies, and those not published in a peer-reviewed journal were excluded.

Search and data abstraction

Studies were identified by searching electronic databases and scanning the references of key reviews (e.g., Patel et al. Reference Patel, Araya, Chatterjee, Chisholm, Cohen, De Silva, Hosman, Mcguire, Rojas and van Ommeren2007; Mejia et al. Reference Mejia, Calam and Sanders2012; Panter-Brick et al. Reference Panter-Brick, Burgess, Eggerman, Mcallister, Pruett and Leckman2014). PsycInfo, PubMed, and Web of Science were searched with no time period limits.

Standardized search terms were applied in a sequential, stepped approach. Syntax consisted of terms and key words related to the following constructs: (a) alcohol, (b) each LMIC and setting type (e.g., ‘developing country’, ‘Uganda’), (c) intervention, (d) male inclusion, and (e) family-related (e.g., ‘father’, ‘marriage’, ‘parenting’). English language filters were applied to PubMed and Web of Science searches. See appendix for full list of search terms.

All resulting titles and abstracts were compiled and considered. The lead author (AG) assessed eligibility based on the pre-determined criteria. For the remaining articles, the full texts were reviewed, assessed for inclusion, and recorded in a database developed based on the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group's data extraction template, PRISMA guidelines, and study aims (Moher et al. Reference Moher, Shamseer, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati, Petticrew, Shekelle and Stewart2015). In cases where the eligibility was unclear, the first and second author discussed and reached consensus. The following information was extracted: author, year, title, city/country, study details (e.g., aims, design), participant details (e.g., age, sample size), intervention details (e.g., targets, strategies, implementation methods, context-specific adaptations), and results.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was coded based on adapted Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group guidelines (Ryan, Reference Ryan2013). Articles were rated on 11 criteria for the following: randomization, allocation concealment, baseline characteristic reporting, blinding, attrition, selective reporting, missing data analysis, and adequate sample size. Criteria were coded 1/yes, 0/no, or unclear; each ‘point’ equated to a reduction in bias. Studies were demarcated as ‘high’ ‘low’ or ‘medium’ risk based on resulting scores (0–4 = high, 4–7 = medium, 8–11 = low). Any study lacking randomization was considered ‘high risk’ regardless of criteria score.

Results

In this section, we first present findings related to search results, followed by trial characteristics across studies, including study location, participants, trial design, intervention characteristics, strategies, and adaptations. We then present findings related to intervention effects on key outcomes of interest followed by effects on individual outcomes of interest with the goal of synthesizing results in a way that elucidates treatment patterns when they emerge.

Search results

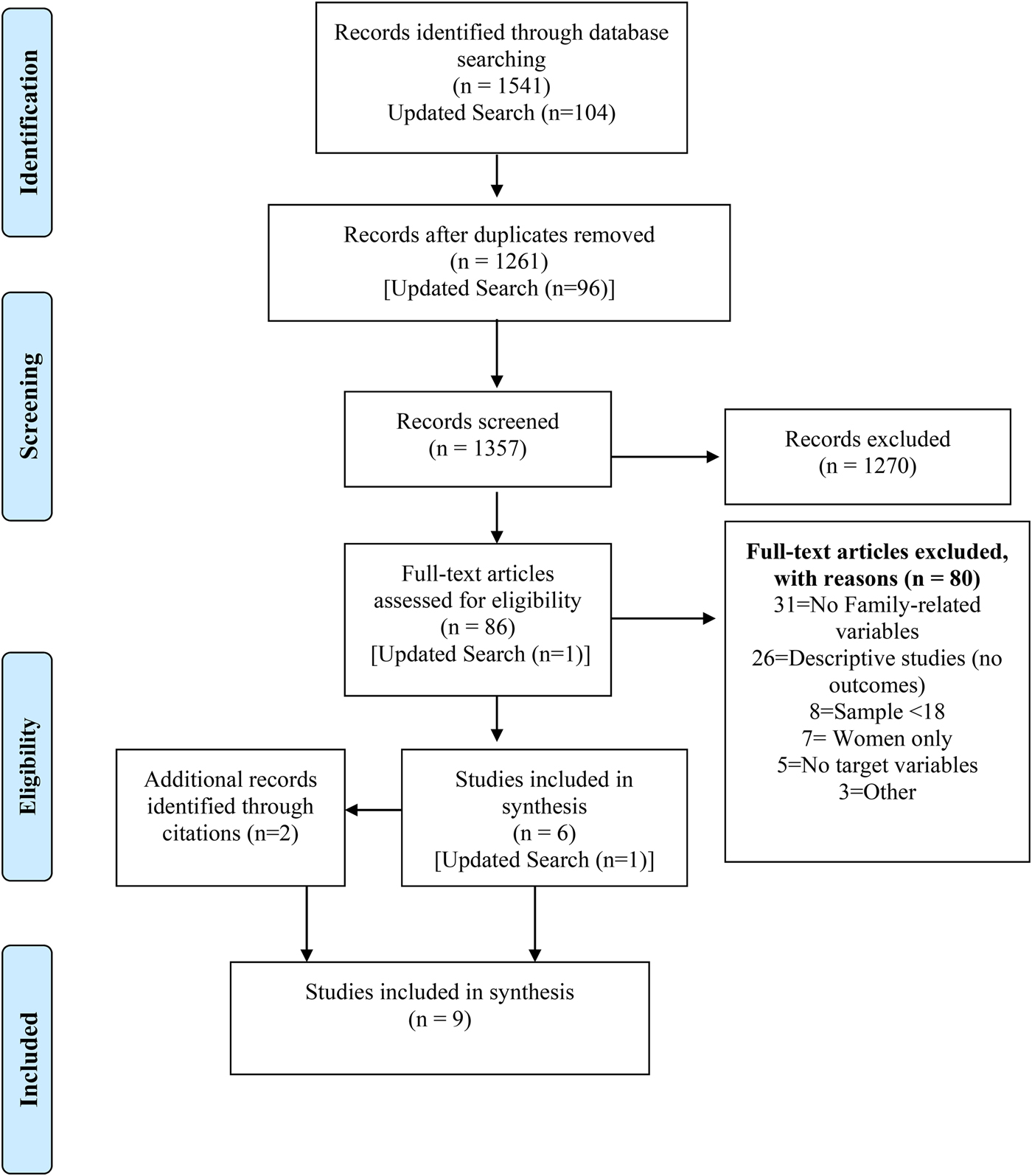

Initial searches (19 December 2015) yielded 1541 records, and 1261 remained after removing duplicates. After the screening of titles and abstracts, 86 were eligible for full review (See Fig. 1). Full texts were then reviewed, and 80 did not meet inclusion criteria. Examining the reference lists from the remaining six articles identified two additional studies (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013). On 23 December 2016, the search was updated, yielding 96 additional titles; these were reviewed following the same procedures and yielded one additional record (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016). Thus, nine studies were included in this review.

Fig. 1. Search flow diagram.

Trial characteristics

Location/setting

As presented in Table 1, studies were conducted in South Africa (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014; Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009), Zambia (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014), India (Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010; Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010; Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016), and Iran (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008). Trial settings included health clinics (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014), primary care facilities (Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013), residential or inpatient treatment centers (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008; Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016), rural communities (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008), an urban slum area (Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010), an informal settlement (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014), and an urban community (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

Note: italicized, primary intervention target; >, signifies the arm to the left of ‘>’ saw significant reductions in the associated variable when compared with the other treatment arm; M, male reported (on self); F, female reported (on partner); °, all finding reported refer to statistically significant change not trends for findings of interest-significance refers to statistical significance below a 0.05 alpha; RCT, randomized control trial; QE: Quasi-experimental; grp, group; NR, not reported; IPV, intimate partner violence; BL, baseline; mo, month; wk, week; yo, year old; MHC, biomedical primary health center providers; AYUSH, Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, Homeopathy providers; TAU, treatment as usual; ICD-10, international classification of diseases; NGO, non-governmental organization; CSC, cross sectional surveys; LP, longitudinal panel; CHC, community health center; GBV, gender-based violence; RES, research-led; SS, stepping stones; CF, creating futures; Y/N, yes or no; ‘gupt rog’, Indian term for sexually transmitted infections, fertility and sexual problems; AUDIT, alcohol use disorders identification test; IRP, individual relapse prevention; DRP, dyadic relapse prevention; TTC, tehran therapeutic community.

Participants

Participants were between the ages of 16 and 47 years with samples ranging from 43 participants (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008) to 2600 (Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010; See Table 2). Three studies included both men and women; of those, one included HIV seroconcordant and serodiscordant couples (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014), and two consisted of young men and women (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014). Of the six that only included men, two were conducted with married men seeking sexually transmitted infection (STI) treatment (Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010; Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013), one included married men in treatment for alcohol dependence with children (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016), one among men in the general population (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009), and two among men in treatment for alcohol dependence (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008; Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010).

Table 2. Description of interventions

Note: IPV, intimate partner violence; GBV, gender-based violence; SS, stepping stones; CF, creating futures; RES, research-led; CHC, community health center; DRP, dyadic relapse prevention; IRP, individual relapse prevention; TAU, treatment as usual; NR, not reported; FAQ, frequently asked questions; CSC, cross-sectional survey; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; Q&A, question and answer; AUD, alcohol use disorder; formative work, in-country work or adaptation completed prior to intervention implementation; NGO, non-governmental organization; MHC, biomedical primary health center providers; AYUSH, Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, Homeopathy providers; PPASA, Planned Parenthood Association of South Africa; hrs., hours; yrs., years; wk.=week.

Design

The majority of trials employed quasi-experimental designs with two randomized control trials (RCTs) (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016; See Table 1). Six of the nine studies compared the primary intervention to a comparison group (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008; Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010; Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013; Jones, et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016). Of these, comparison groups consisted of different provider type (Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014), treatment as usual (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016), a psychoeducation workshop (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008), a different delivery format – individual v. family (Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010), and an active treatment condition (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009). Of the remaining three studies, one employed a pre-post interrupted time-series design (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014), and two employed a pre-post design with no comparison groups (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008; Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010).

Intervention characteristics

Within the nine studies, ten interventions were evaluated because one study (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009) included a comparison intervention active enough and dissimilar enough from the tested intervention to be examined. Intervention aims were diverse. Only one intervention had the primary aim to target both alcohol use and IPV among men (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016); rather, the most common primary intervention targets were sexual risk and STIs (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008; Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013; Jones, et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014), followed by alcohol-use (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008; Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010; Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010). One trial targeted both gender-based violence (GBV) and sexual risk behavior as primary outcomes (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009), while another targeted both GBV and financial earnings (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014). Interventions were delivered by a range of professionals and non-specialists (Table 2).

Intervention strategies

Table 2 describes strategies implemented across interventions and theoretical underpinnings. Every intervention employed elements of structured discussion, goal-directed feedback (e.g., alternative suggestions), and psychoeducation targeting unique aims. Seven of ten programs stated use of participatory learning techniques such as group discussion, role-play (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016), and dramas (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014). Communication skills were taught in five programs that each included a focus on GBV/IPV (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008; Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014). Three used gender-transformative approaches for addressing GBV/IPV (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014; Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009). Cognitive-behavioral strategies were also described in six of ten programs (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008; Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016); of these, one was delivered as individual therapy (Saggurti, et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013).

Unique strategies also emerged with three programs specifically employing assertiveness techniques (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016) and one teaching alcohol refusal skills (Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010). One program helped strengthen job skills (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014), and another taught financial budgeting (Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010). Only one used motivational interviewing for alcohol use (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009); one used narrative techniques (Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013); and one explicitly targeted the link between alcohol use and IPV using CBT principles (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016). Lastly, a community-level program applied many strategies to increase community awareness and education (Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010).

Intervention adaptations

Intervention adaptations ranged from surface level modifications (i.e., basic translation) to deep adaptation (i.e., modified rationale and intervention strategies) to the development of a new intervention for the context (Table 3). Six studies applied deep adaptation to previous interventions based on formative community-based work, such as interviews and focus groups, piloting, and community partnerships (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010; Saggurti, et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016). Three interventions were considered to have surface-level adaptations, such as translations or changes to the structure of the intervention that did not significantly change the content or strategies (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014; Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010). Lastly, a residential program was not adapted per se, as it was implemented based on general therapeutic community principles (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008).

Table 3. Contextual and cultural considerations of reviewed interventions

Note: NI, not enough information to make a determination; #, for this intervention, there is an adapted version of the original manual for South Africa e , but the methods for adaptation are not published to our knowledge and as such information from published material is presented, but may miss important aspects of adaptation; CHC, community health clinic; PTT, previously tested treatment; DA, deep adaptation; SA, surface adaptation; CV, content validation; PF, participatory feedback; W, workshop; L, language; UC, unclear; RES, research-led; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa; SA, South Africa; DRP, dyadic relapse prevention; IRP, individual relapse prevention; RISHTA, research and intervention in sexual health: theory to action; NGO, non-governmental organization; STI, sexually transmitted infection; *, time and frequency not reported; NR, not reported; MHC, biomedical primary health center; AYUSH, Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, Homeopathy providers; GBV, gender based violence; ICBI, integrated cognitive behavioral therapy.

a Jones DL, Weiss SM, Chitalu N, Villar O, Kumar M, Bwalya V, Mumbi M (2007) Sexual risk intervention in multiethnic drug and alcohol users. American Journal of Infectious Diseases 3(4), 169.

b Jones D, Kashy D, Chitalu N, Kankasa C, Mumbi M, Cook R, Weiss S (2014) Risk reduction among HIV-seroconcordant and-discordant couples: the Zambia NOW2 intervention. AIDS patient care and STDs 28(8), 433–441.

c Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Strebel A, Henda N, Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Kalichman M, Crawford M, Cain D, Shefer T, Thabalala M (2008) HIV/AIDS risk reduction and domestic violence intervention for South African men: theoretical foundations, development, and test of concept. International Journal of Men's Health 7, 254–272.

d Satyanarayana VA, Hebbani S, Hegde S, Krishnan S, Srinivasan K (2015). Two sides of a coin: Perpetrators and survivors perspectives on the triad of alcohol, intimate partner violence and mental health in South India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 15, 38–43.

e Jewkes R, Nduna M, Jama PN (2002) Stepping Stones, South African Adaptation, 2nd edn. Medical Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa.

Outcome measures

One intervention targeted alcohol use and a family-related variable as the primary specified outcomes of change (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016; See Table 1). As described, sexual risk/STI reduction was the most common primary target. Measures of alcohol-use included frequency and quantity of use (Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010; Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014), drug and alcohol consumption (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008), any alcohol use (Yes/No; Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013), alcohol use before sex (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009), severity of alcohol dependence (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016), and problem drinking (Yes/No; Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014). Time frames ranged from 12 months (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014) to within the past week (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014). For family-related variables, IPV/GBV were most commonly measured (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014; Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Schensul et al. Reference Schensul, Saggurti, Burleson and Singh2010; Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Weiss, Arheart, Cook and Chitalu2014; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016); three of these identified IPV/GBV as a primary target (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016). Three studies included other family-level variables as secondary outcomes including days without family dysfunction (Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010); quality of family and social relationships (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008); and spousal stress, anxiety, depression, and child mental health (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016).

Interventions impacting alcohol use and family-related outcomes

Table 1 presents each trial's results for the outcomes of interest. Although only one intervention had the primary aim of targeting both alcohol-use and a family-related outcome, results indicated that five interventions were associated with improvements in both alcohol use and at least one family-related outcome (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008; Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008; Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010; Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016). One RCT comparing treatment as usual and a CBT intervention showed decreased severity of alcohol dependence across both conditions, while the CBT group showed greater improvements in IPV and secondary outcomes of spousal depression, stress, and anxiety; no improvements in child well-being were detected (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016). Next, the RCT of an HIV and STI risk intervention, ‘Stepping Stones’, showed improvements in secondary outcomes of problem drinking and sexual/physical violence; primary outcome results showed reduced herpes simplex virus (HSV-2) but no significant effects on HIV incidence (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008). The Dyadic Relapse Prevention (DRP) program showed pre-post reductions in the primary alcohol use outcome and secondary outcome of family functioning (Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010). A brief narrative intervention achieved primary outcomes of reducing ‘gupta rog’ symptoms, a catchall Indian term for STIs and sexual problems, and decreased secondary outcomes of reduced alcohol use, reduced extramarital affairs, improved spousal communication, and more equitable gender attitudes (Saggurti et al. Reference Saggurti, Schensul, Nastasi, Singh, Burleson and Verma2013). The Tehran residential therapeutic community (TCC) showed significant improvements in drug and alcohol use and secondary outcome improvements of social and family relationships (Abdollahnejad, Reference Abdollahnejad2008).

Interventions impacting alcohol use or family-related outcomes

Three interventions showed either drinking or family outcome improvements. The study by Kalichman et al. (Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009) comparing the effectiveness of two interventions – (1) an integrated GBV and HIV prevention program (GBV/HIV) and (2) a briefer alcohol and HIV prevention program (ALC/HIV) on sexual risk and GBV perpetration – found the interventions led to different improvements (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009). ALC/HIV was associated with improvements in secondary outcomes of alcohol use before sex but not GBV. Conversely, the GBV/HIV intervention did not reduce alcohol use but was associated with improvements in the primary outcome of GBV, loss of temper with a woman, sexual communication, and acceptance of violence (Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009). Next, ‘Stepping Stones’, the HIV prevention program, was combined with a financial strengthening intervention and showed improved secondary couple-level variables of men's gender attitudes and relationship control (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014). Unlike the previous RCT evaluation of ‘Stepping Stones’ alone (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008), problem drinking did not significantly decrease for men, but mental health improved and women reported decreased physical/sexual violence.

Risk of bias

Two studies were randomized and analyzed at the level of randomization with a low risk of bias (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008; Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016), while the remaining seven were considered high-risk given a lack of randomization. High-risk of bias invites caution when interpreting results across findings. However, for the non-randomized studies, it should be noted that the methodologies typically matched study purpose (e.g., interrupted time series for pilot/feasibility purposes).

Discussion

The intersections between men's problem drinking and family consequences present a unique opportunity for combined interventions targeting improvements on multiple outcomes from alcohol use to child mental health, family functioning, violence, and intergenerational cycles of risk. The purpose of this review was to examine the extant literature on interventions targeting both alcohol and family-related outcomes with men in LMICs. In total, nine studies and ten interventions met inclusion criteria. Of those, one had the primary goal of improving both drinking and related family-level outcomes (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016); the remainder included one (two studies) or both (seven studies) as secondary, with many focusing primarily on sexual risk. Most family outcomes related to couples well-being, and no studies targeted parent-child relationships.

Despite the lack of direct focus on alcohol and family outcomes, over half of the studies documented modest improvements in both outcomes. Additionally, despite heterogeneity across studies, results point to promising core intervention strategies. Here, we discuss these strategies and the ways that future interventions can build on them by combining results with broader evidence on family-based interventions. Given the lack of interventions targeting alcohol and parent-child outcomes, we include how lessons learned from this review may apply to possibilities for combining alcohol- and parenting-focused strategies.

Intervention strategies

Interventions that improved both drinking and family outcomes included cognitive and behavioral strategies, communication skills training, and narrative techniques often taught through participatory learning. What these approaches have in common is that they are grounded in previous evidence and have been applied to changing a wide range of behaviors. It follows that having such strategies at the core of future combined interventions would allow participants to learn skills that they can then apply to both drinking and relationship goals. For instance, problem-solving can be applied to identify consequences and find alternatives to both drinking and IPV. Further, aiming to target these outcomes directly is likely important for specifically improving them (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016). Incorporating family members or partners in treatment also emerged as a potentially important element for seeing multi-target improvements (Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010; Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014). This complements HIC literature showing couples/family treatments typically outperform individual approaches for addressing alcohol use, couple conflict, and mental health (Baucom et al. Reference Baucom, Whisman and Paprocki2012). Yet, family member inclusion may not always be necessary to see improvements in family-level outcomes (Satyanarayana et al. Reference Satyanarayana, Nattala, Selvam, Pradeep, Hebbani, Hegde and Srinivasan2016).

Effective strategies also emerged that were specific only to one outcome. For alcohol use, these included motivational interviewing (MI), behavioral management, and goal-setting (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008; Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009; Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010), which are consistent with the larger evidence-base (Benegal et al. Reference Benegal, Chand and Obot2009). For family outcomes, gender-transformative approaches were associated with reduced IPV (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014; Kalichman et al. Reference Kalichman, Simbayi, Cloete, Clayford, Arnolds, Mxoli, Smith, Cherry, Shefer, Crawford and Kalichman2009), the most commonly included relationship outcome. This supports growing evidence that shifting unequal gender norms and targeting hegemonic masculinity can reduce GBV (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Flood and Lang2015).

Integrating the broader evidence base on family interventions

Given the limited targets of the interventions identified through this review, results should be examined alongside existing dual-target intervention approaches described in the introduction and the larger family intervention evidence base. Taken together, we can better discern opportunities for a broader range of combined interventions to reduce alcohol use and improve couples’ and parent–child relationships across contexts.

Outside of the literature on alcohol use, parenting intervention studies in both HICs and LMICs points to strategies to consider for alcohol-family interventions. Most clearly, behavioral parenting interventions that strengthen skills for positive interactions and effective behavior management have a strong evidence base in HICs (Kaminski et al. Reference Kaminski, Valle, Filene and Boyle2008). They are also gaining evidence in LMICs (see reviews by Mejia et al. Reference Mejia, Calam and Sanders2012; Knerr et al. Reference Knerr, Gardner and Cluver2013). As examples, parenting and family programs have shown positive impacts among caregivers in Liberia (Puffer et al. Reference Puffer, Green, Chase, Sim, Zayzay, Friis, Garcia-Rolland and Boone2015), caregivers in South Africa (Cluver et al. Reference Cluver, Meinck, Yakubovich, Doubt, Redfern, Ward, Salah, De Stone, Petersen, Mpimpilashe, Romero, Ncobo, Lachman, Tsoanyane, Shenderovich, Loening, Byrne, Sherr, Kaplan and Gardner2016), and Burmese migrant families (Puffer et al. Reference Puffer, Annan, Sim, Salhi and Betancourtin press). They have also documented effects on mental health symptoms of children (Jordans et al. Reference Jordans, Tol, Ndayisaba and Komproe2013; Annan et al. Reference Annan, Sim, Puffer, Salhi and Betancourt2016). The evidence is therefore, converging to provide the foundation for combining effective parenting intervention strategies with interventions for other outcomes, such as alcohol use, that also affect the family system. One challenge to tackle when combining interventions to target male problem drinking is that fathers have often been under-represented in parenting programs. This is in part due to difficulties engaging men in treatment – a task made more challenging by alcohol use (Cowan et al. Reference Cowan, Cowan, Pruett, Pruett and Wong2009). As men hold responsibility and power influencing family outcomes, Panter-Brick and colleagues (2014) describe their inclusion as a potential ‘game-change’ in the field of child and family health.

Adapting existing dual-target interventions evaluated in HICs to LMICs represents another avenue for addressing alcohol use and family relationships in these settings. Given the growing evidence base for alcohol-family treatments in HICs and the successes of culturally adapted programs (Castro et al. Reference Castro, Barrera and Holleran Steiker2010), it follows that adaption of evidence-based programs would be a viable option. Nattala and colleagues (2010) – an included study – further demonstrated the promise of this approach when using ABCT as one of three manuals from which they developed the Dyadic Relapse Prevention program in India with positive outcomes on intended alcohol and relationship targets (Nattala et al. Reference Nattala, Leung, Nagarajaiah and Murthy2010)

Efforts to combine promising strategies would be well-timed, as emerging approaches to mental health treatment have the explicit goal of combining strategies in ways that can reach multiple outcomes in a cohesive, parsimonious, and effective manner (Chorpita et al. Reference Chorpita, Daleiden and Weisz2005; Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Bullis, Comer and Ametaj2013; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Dorsey, Haroz, Lee, Alsiary, Haydary, Weiss and Bolton2014). Transdiagnostic and modular strategies represent two such approaches. Transdiagnostic approaches identify and target common and core maladaptive features underlying categorized dysfunctions (e.g., depression) that are not disorder-specific (e.g., interpersonal difficulties maintaining substance use, depression, IPV); those overlapping features can then be targeted through a set of common treatment elements (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Dorsey, Haroz, Lee, Alsiary, Haydary, Weiss and Bolton2014). Modular approaches work to integrate complementary strategies into unique intervention packages; full interventions can be sub-divided into meaningful, stand-alone components to be flexibly implemented alone or in complement (Chorpita et al. Reference Chorpita, Daleiden and Weisz2005; Lyon et al. Reference Lyon, Lau, Mccauley, Vander Stoep and Chorpita2014).

Limitations

This review is limited by study heterogeneity and high-risk designs that precluded the ability to conduct a meta-analysis and point to the need for more rigorous evaluation designs. Variability in measurement also limited the conclusions drawn, with only two studies using the same assessment of alcohol use (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Nduna, Levin, Jama, Dunkle, Puren and Duvvury2008, Reference Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha and Skiweyiya2014). Additionally, the search approach, while systematic, cannot guarantee the identification of all interventions as it is subject to publication and language bias. Related, it is possible some interventions were not included in the review if a secondary outcome variable of interest, such as alcohol, was not noted in their methods, abstract, keyword, or title. The search and data extraction also were primarily conducted by the first author rather than having multiple independent raters. Lastly, including unpublished and qualitative results may have identified additional intervention approaches.

Conclusion

This systematic review identified nine peer-reviewed intervention studies conducted with men in LMICs that included measures of alcohol-use and a family-related outcome. Five interventions led to improvements in both alcohol and family outcomes. Those often used cognitive-behavioral strategies, communication skills, narrative techniques, and participatory learning approaches. Three interventions showed improvements in either an alcohol or a family related outcome using motivational interviewing and behavioral approaches, and gender-transformative strategies, respectively. Overall, results highlight the scarcity of interventions addressing men's drinking and its effects on families, particularly related to parent-child outcomes. However, results of those that do exist suggest the feasibility and likely benefits of combined approaches. Future interventions can target a broader range of family relationships that are affected by alcohol use by integrating promising strategies with other evidence-based couples and parenting interventions as well as exploring the adaptation of combined approaches effective in HICs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2017.32.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Hannah Rozear from the Duke University Library for advising the systematic review process, helping create search syntax, and advising review implementation, as well as Dr. Kathy Sikkema, Dr. Brandon Khort, and Dr. John Curry for advising manuscript development.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Interest

None.