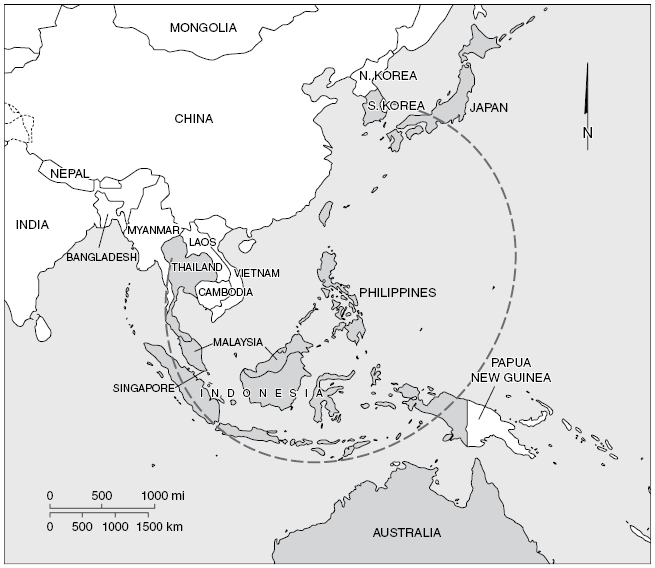

A consideration of the four-year period that began with Richard Nixon’s ascension to the presidency of the United States in January 1969 and ended with signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973 raises several important questions about the Vietnam War. Could an agreement comparable to the 1973 deal have been secured earlier? If so, who bears responsibility for the delay? What was the impact of the antiwar movement on Nixon’s Vietnam policy? Was the war’s expansion into Laos and Cambodia necessary or criminal? Were the constraints on Nixon’s prosecution of the war evidence of the functioning of democracy or of the weakness of the American system, which jeopardized and discredited US foreign policy? Did international opposition to the war hinder Nixon’s efforts to achieve “peace with honor” and make full use of the US military to support his diplomatic initiatives? Or, on the contrary, did it prevent escalation and even greater bloodshed by denouncing the “immorality” of the conflict? In short, under what circumstances did the January 1973 peace agreement come about?

Three major milestones marked Nixon’s relationship with Vietnam, the rest of Indochina, and Southeast Asia generally between 1969 and 1973. Although Nixon did not have a “secret plan” to end the war in Vietnam when he took office, he gradually put a strategy in place. In this respect, 1969 was a year of trial and error, of failure and deadlock. Certainly, important processes were underway, such as Vietnamization and secret negotiations, though the latter were, at the time, largely unproductive. Subsequently, Vietnamese communist policymakers would claim that in initiating the phased withdrawal of their forces in 1969, the Americans in fact weakened their bargaining position. Thus, by the turn of the new decade, the United States remained unable to achieve “peace with honor.” To overcome these aporias, Nixon, assisted by National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, tried to move from the local to the global, transposing and adapting his strategy in the broader context of the opening up of China and détente with the Soviet Union, two initiatives that, in Kissinger’s words, restored Southeast Asia to its true scale: that of a “small peninsula at the end of a huge continent.” But this so-called triangular diplomacy still failed to end the war. Therefore, Nixon redoubled the military pressure on Hanoi in 1972 until reaching a peace agreement that failed to deliver the peace it promised. To what extent was all this a cowardly “decent interval” snatched by the United States before the inevitable collapse of Saigon, Phnom Penh, and Vientiane? Or was it proof of a real and credible will to maintain the political status quo in the region?

Historians Go to War

“History will treat me fairly. Historians probably won’t, because most historians are on the left,” stated Richard Nixon on Meet the Press in 1988.Footnote 1 Nixon, as well as Kissinger, did not rely on leftist historians to write the history of the end of the Vietnam War. Their own memoirs, books, interviews, and articles abundantly presented their versions of the end of the war. In No More Vietnams, to illustrate, Nixon argued that the United States lost the war in Southeast Asia on the political front only, not the military one. He attributed the political defeat to the media and especially to the peace movement, which he described as variously “misguided, well-meaning, and malicious.”Footnote 2 For Nixon, the peace movement was the deciding factor in prolonging the war.Footnote 3 Kissinger, for his part, emphasized the importance of public opinion on the course of military operations, as well as on the war’s political dynamics. He drew a comparison with French President Charles de Gaulle’s management of the Algerian War. The United States was faced with the same problem de Gaulle confronted: withdrawing by political choice, not by defeat. However, the nature of the opposition to the leaders was quite different in France and in the United States. In the first case, de Gaulle was faced with hardliners who demanded victory. This gave him some leeway with the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), since any alternative to Charles de Gaulle would have been worse for the rebels. In the United States, on the other hand, the opposition Nixon and Kissinger faced came from those who wanted a quicker, even immediate, withdrawal. This major distinction ruined, for Kissinger, any prospects for successful bargaining with Hanoi. For this reason, Kissinger considered it “a real political tour de force” to have been able to persevere with disengagement over four years and “to have achieved a solution of compromise and balance of power, however precarious, in Vietnam.”Footnote 4

Such theses were defended by not only Nixon and Kissinger. Several members of their administration, who at the time did not always agree with the two men, endorsed their stance. Alexander Haig, for example, said in retrospect that he was “absolutely, categorically convinced that if we had done in 1969 what we did in 1972, the war would have ended, we would have got our prisoners back, and our objectives would have been achieved.”Footnote 5 Former Secretary of Defense and architect of Vietnamization Melvin Laird attacked in Foreign Affairs “the revisionist historians” for quite conveniently forgetting that the United States had not lost the war when it pulled out of Vietnam in 1973. “In fact, we grabbed defeat from the jaws of victory two years later when Congress cut off the funding for South Vietnam that had allowed it to continue to fight on its own.”Footnote 6

This version of events has been challenged by several historians, including Marilyn B. Young, Tom Wells, George C. Herring, and Jeffrey Kimball.Footnote 7 In Nixon’s Vietnam War, Kimball accused Nixon of having distorted the debate regarding the causes for, meaning of, and end of the war.Footnote 8 He suggested in veiled terms that Nixon was on the edge of actual madness at the time the war ended.Footnote 9 He concluded, first, that the tragedy of the Vietnam War was that it was “a wrong war, in the wrong place, and against the wrong enemy” and, second, that Nixon and Kissinger’s version of the end of the war was deeply ideological and aimed at exonerating them.Footnote 10 Historian Pierre Asselin has disputed some of Kimball’s claims. “Ironically,” he writes, “Kimball’s characterization of Nixon as an angry and impulsive man who may have had some sort of personality disorder runs contrary to what documentary evidence suggests, namely, that Nixon and Kissinger’s Vietnam policies were products of lengthy deliberations, careful calculations, and realistic considerations.”Footnote 11 Lien-Hang T. Nguyen and Larry Berman offer a radically different angle of criticism.Footnote 12

In Search of a Strategy

When Nixon took office, ending the Vietnam War was his priority.Footnote 13 He had campaigned on the theme of “peace with honor,” implying that he had a secret plan to end the war, a plan he could not yet reveal unless he made it invalid. He promised to end the war within six months. The electoral promises and objectives were very optimistic, given the then-current catastrophic situation of the war. In January 1969, 540,000 American troops were in Vietnam; more than 30,000 of them had already died, including 14,500 in 1968 alone. The cost of the war reached $30 billion in fiscal year 1969. Prospects for the future were bleak. It soon became clear that the Nixon administration was caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, Nixon and his transition team quickly rejected the option of immediate military escalation, whether it was a massive resumption of bombing, a threatened invasion of the North, or, most importantly, the two decisive strikes that could have led to a military victory: the destruction of the North’s levee system, which Nixon said would have led to flooding “causing the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people,” or the use of tactical nuclear weapons. Both options, he wrote later, “would have caused such an uproar at home and abroad that they would have given my term in office the worst possible start.”Footnote 14

Withdrawal from Vietnam at once, which would have appeased the war’s opponents, offered hope for the return of prisoners of war (POWs), and shifted the blame for the war on the Democrats, was also rejected by Nixon. It would have resulted in the abandonment of 17 million Vietnamese in the South and ruined the credibility of the United States vis-à-vis its other allies.Footnote 15 Early on, in fact from the transition period, the Nixon administration embarked on a course not unlike that of the previous administration: there would be no additional troops sent to Vietnam; President Lyndon Johnson’s cessation of bombing of the North would be respected; and the Paris negotiations would continue. According to Robert Schulzinger, Nixon’s policy toward Vietnam in 1969 contrasted sharply with the rest of his foreign policy, generally innovative and dynamic, which brought him the support of Congress.Footnote 16

Did that mean Nixon did not have an original policy to implement in Vietnam, and no “secret plan” to apply? Not really. Nixon had a strategy, which was gradually put in place throughout 1969. First, there was the element of coercion, illustrated by the bombing of Cambodia, which began on March 18, 1969 under the code name MENU and continued until April 1970. Although revealed on May 9, 1969 by a New York Times journalist, William Beecher, the secrecy of the operations was as much a result of Nixon and Kissinger’s taste for clandestine operations as of the need not to stir up reactions on American soil.Footnote 17 Second, no doubt overestimating Soviet influence in Hanoi, Nixon initially intended to put pressure on Moscow by connecting any further progress in bilateral relations between the two superpowers to Moscow’s assistance in solving the Vietnamese conflict. He felt Sino-Soviet tensions could serve as another incentive for Moscow to indulge him. After Hanoi responded favorably to President Johnson’s proposal to open peace negotiations in Paris in April 1968, Beijing was livid. Its stance was that the United States could only suffer a military defeat in Vietnam, coupled with humiliation. There could be no negotiations. The Soviet Union, on the other hand, supported Hanoi’s decision to diplomatically engage the Americans. This disagreement fueled the Sino-Soviet dispute. After Moscow crushed the Prague Spring in 1968, the Chinese felt that they could be the next victims of the “Brezhnev Doctrine” and accused Moscow of “socialist imperialism.” One of the major fears of China, then in the throes of the Cultural Revolution, was American–Soviet collusion directed against it. The Paris negotiations and the apparent Soviet–Vietnamese rapprochement, in short, aggravated China’s isolation. It was only in November 1968 that, not without reluctance, Mao resolved, when receiving Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) Premier Phạm Vӑn Đồng, to recognize the negotiations as part of Hanoi’s strategy of “negotiating while fighting.” The Americans were aware of all this. During a meeting with Soviet Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Dobrynin on June 11, 1969, Kissinger pointed out that 85 percent of Hanoi’s military resources came from the USSR.Footnote 18 However, even if they had wished for it, the Soviets were not really in a position to impose an ultimatum on Hanoi.

In March 1969, Nixon’s strategy expanded to incorporate the idea of “de-Americanizing” or rather “Vietnamizing” the conflict.Footnote 19 Nixon intended to find a way that would allow him to both “de-Americanize” the conflict and push Hanoi to negotiate faster. As a matter of fact, as the negotiations with the DRVN would amply demonstrate, these two proposals were antithetical. Unless the South Vietnamese Army could undergo proper training, be well-equipped, and be ready to take the place of the United States, the “de-Americanization” process would surely weaken the US position, an intrinsic flaw of the strategy that Kissinger denounced from the start.Footnote 20 Nixon spoke of the need to “de-Americanize” the war while Melvin Laird instead suggested the term “Vietnamization,” which got the president’s approval.Footnote 21 An inexorable process had been set in motion: that of the unilateral withdrawal of the United States from Vietnam.

Next, Nixon counted on the secret talks with Hanoi brokered with the help of the former French delegate general there, Jean Sainteny, whose wife was a former student of Kissinger.Footnote 22 In July, Nixon had secretly written to Hồ Chí Minh to reaffirm “in all solemnity his desire to work for a just peace.”Footnote 23 On August 4, 1969, the first secret meeting took place between Kissinger and DRVN envoy Xuân Thủy in a Paris suburb.Footnote 24 On August 25, Hồ Chí Minh’s reply to Nixon’s letter arrived. It made clear there would be no great breakthrough. While Nixon had begun his letter with “Dear Mr. President,” Hồ Chí Minh did not return the courtesy and began with “Mr. President.” In substance, Hồ Chí Minh merely denounced the “American aggression against his people, violating their national rights” and repeated the demands of Hanoi’s emissary in Paris, namely a unilateral withdrawal by the United States.Footnote 25

In his memoirs, Nixon writes that as soon as he received Hồ Chí Minh’s letter, he knew that he “had to prepare myself for the tremendous criticism and pressure that comes with stepping up the war.” While pursuing Laird’s Vietnamization policy, Nixon simultaneously hoped to launch the “mad bomber strategy” to force the North Vietnamese into submission. According to White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman, Nixon had considered such a strategy during a walk on a beach in 1968:

I call it the Madman Theory, Bob. I want the North Vietnamese to believe I’ve reached the point where I might do anything to stop the war. We’ll just slip the word to them that, “for God’s sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about communism. We can’t restrain him when he’s angry – and he has his hand on the nuclear button” and Hồ Chí Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace.Footnote 26

Kissinger intended to give weight to Nixon’s “mad bomber strategy” and, in any event, use it as a military tool to help the negotiations with the North. For these purposes, he created the “September Group” mandated to study the possibility of military action to have a “maximum impact on the enemy” in order to bring the war to a “rapid conclusion.” It was before this group that Kissinger is said to have stated that “I refuse to believe that a small fourth-rate country like Vietnam does not have a breaking point. … It will be the mission of this group to study the option of a savage and decisive strike against North Vietnam. You will begin your work without preconceived ideas.”Footnote 27 The group did not work in uncharted waters. Since the spring, General Earl Wheeler, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), and his staff had been working on one such plan called Duck Hook. On September 9, Kissinger met with Wheeler before discussing the plan with the president. Kissinger had asked Wheeler to keep this plan a secret, that is, strictly limited to a few military personnel and excluding the secretary of defense.Footnote 28 The plan was officially presented to Nixon on October 2. Duck Hook consisted of an intensive attack on North Vietnam concentrated over four days, a period that could be extended, depending on weather conditions. Several similar series of attacks would then follow, after a pause to assess the results of the first attack and give the North Vietnamese an opportunity to reformulate their peace proposals. The DRVN’s deep-water ports would be mined to suffocate the country. Rail links to China would be rendered impassable. Twenty-nine targets were identified: five complexes in the Hanoi metropolitan area; six power plants; four airports; three factories; five storage areas for high value-added materials and transport equipment; three bridges; two railroads; and, last but certainly not least, the dike system in the Red River Delta.Footnote 29 The draft plan came with a draft speech that the president would have given to the American nation on November 3 to reveal the existence of secret negotiations with Hanoi, their failure, and announcing the beginning of Duck Hook operations.Footnote 30 Nixon wavered between wanting to take a hard line on Hanoi and Moscow, and considering domestic parameters that made it difficult to implement Duck Hook.

Ultimately, Nixon gave up on Duck Hook, probably at the end of October. He never even attempted to introduce it to his National Security Council (NSC). Instead of delivering the speech prepared by the “September Group” in which he was to announce the start of the “decisive” strikes against the North,Footnote 31 he addressed the American people, asking for their support, on November 3, 1969, in the famous “Silent Majority” speech.Footnote 32 In reality, Nixon had acted under political duress, caught in a vice between two important demonstrations against the Vietnam War: on October 15, Moratorium Day, and November 13–15, when new mass demonstrations were announced. Nixon had arguably won a victory over his domestic opponents with the November 3 speech, but it was a Pyrrhic victory. In the aftermath of the “November days” (Mobilization against the War), his own advisor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, acknowledged that “white middle-class youth” had appeared calm and level-headed in their opposition to the war, and, as a result, the Administration’s case against them as unpatriotic would be short-lived.Footnote 33 Beyond that, Nixon had appeared like a paper tiger to the Soviets and the North Vietnamese. The nuclear alert he had decided to launch to panic them had left them unmoved.Footnote 34 So, the war would continue. In this sense, the fall of 1969 was a critical turning point in Nixon’s conduct of the war. All hopes for peace in the short term were dashed. The president’s strategy from then on would be to take a long-term view.

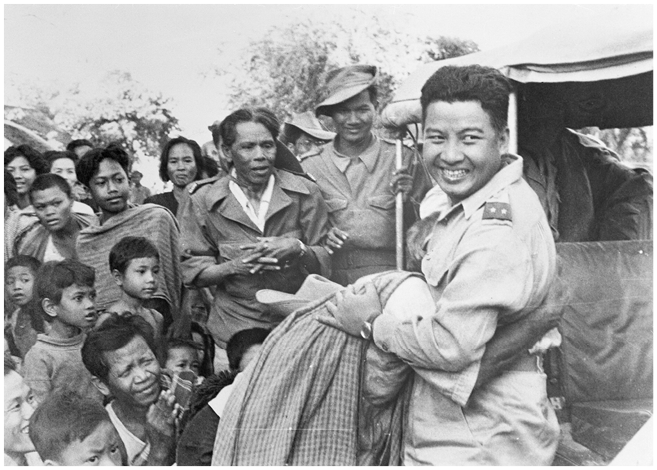

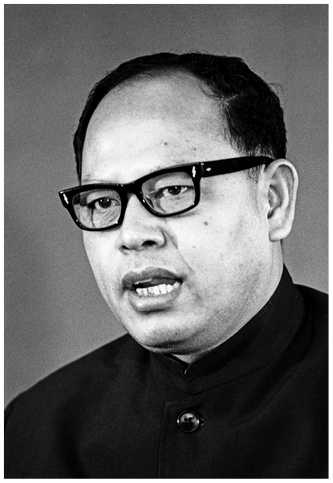

Figure 1.1 Richard Nixon speaking with soldiers at Dĩ An Base Camp during his only visit to South Vietnam (July 30, 1969).

Negotiating while Widening the War

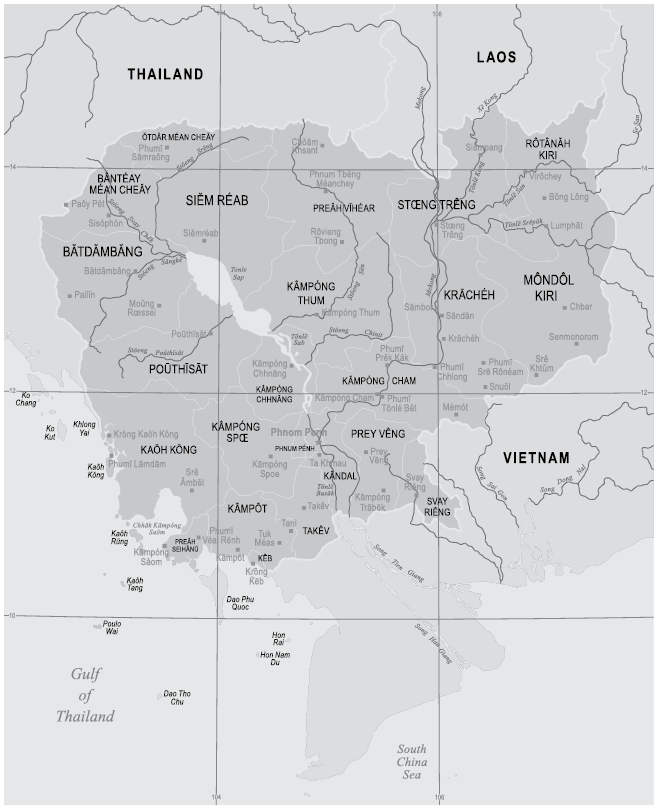

In early 1970, Nixon ordered B-52 strikes on communist supply lines in northern Laos. These particularly violent bombings were supposed to prevent a massive offensive in the spring while demonstrating Nixon’s resoluteness to achieve “peace with honor.” Nixon and Kissinger simultaneously stepped up the war in Cambodia. The ruler there, Norodom Sihanouk, had practiced a delicate balancing act, seeking to alienate neither the South Vietnamese and their American allies nor the National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) and their North Vietnamese and Chinese allies. Thus, the NLF was supplied from the Cambodian port of Kampong Som (Sihanoukville) and, thanks to Chinese aid, bought part of the Cambodian rice crop. Sihanouk knew that North Vietnamese units were stationed on his territory, since Cambodia was crossed by the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. The situation started to deteriorate when local Cambodian communists – the Khmer Rouge – launched an insurgency against the Cambodian regime in 1968. Sihanouk responded with airstrikes on communist bases belonging to both the Khmer Rouge and the North Vietnamese. By early 1970, Sihanouk’s position had become untenable. On March 18, while Sihanouk was in Moscow, General Lon Nol and royal family member Sirik Matak, with the consent of parliament, issued a decree that announced Sihanouk’s removal. The new government ordered the closure of the port of Sihanoukville to ships supplying the NLF and attempted to hinder traffic on the Cambodian portion of the Hồ Chí Minh Trail.

Lon Nol’s coup took the Americans by surprise. There is no evidence that Washington had a hand in it. However, it did not take long before Nixon ordered increased support for the new regime. The arrival in power of Lon Nol and his firm attitude toward the North Vietnamese (tainted, it is true, by a notorious reputation for corruption, if not incompetence) offered the possibility of loosening the stranglehold on South Vietnam. By the time of the coup, Nixon felt that B-52 bombings from Guam were no longer enough: an incursion into Cambodia was necessary to disrupt Vietnamese communist sanctuaries. The president announced his decision on April 30 from the Oval Office. For Nixon, Cambodia had become a top priority, the place where US foreign policy could succeed or fall apart. As a sign of his immense interest in the region, he even ordered that he not be bothered with other issues, including the political situation in Chile.

Operation Lam Sơn 719, in Laos, was conducted by Vietnamese troops beginning February 8, 1971. It turned into a debacle as fighters of the South’s army, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), were evacuated in a hurry by US Army helicopters. Kissinger admitted in his memoirs that “the operation, conceived in doubt and faced with scepticism, continued in confusion.”Footnote 35 There was no confusion, however, as to the consequences of the offensive on the course of the war. On May 14, 1971, the Hanoi Politburo made the decision to launch an offensive in the spring of the following year. Not only were the North Vietnamese convinced of their superiority over the army of the South, but public opinion in the United States seemed to be convinced of the impossibility of a military victory in Indochina. In these conditions, the North Vietnamese Politburo confirmed in July its intention, still secret, to take advantage of the prospects offered by 1972, an election year in the United States.

Reversal of Alliances?

At the very moment, in 1971, when Hanoi prepared to deliver what it hoped would be the final blow to its enemies, profound changes were taking place within the international system. A twofold process was at work, which de facto stood to undermine the DRVN’s position and strengthen that of the United States: Sino-American rapprochement, on the one hand, and a growing divide between Beijing and Hanoi, on the other. Sino-American rapprochement was delayed for a while by the American intervention in Cambodia in 1970, but it became a reality in the spring of 1971. On April 21 of that year, Zhou Enlai sent an official letter of invitation to the American president, which Nixon answered favorably, via Pakistan. Upon receiving Zhou’s letter, Kissinger told Nixon: “If we make this deal, we will end the Vietnam War this year. The mere existence of these contacts, in and of itself, guarantees it.”Footnote 36 He was not wrong. In July 1971, Beijing announced that Nixon would visit China the following year.

The “week that changed the world,” as Nixon himself called his February 1972 visit to China, changed the landscape of the Vietnam conflict considerably. Although Beijing had a nuanced, even ambivalent policy regarding its involvement in the Vietnam War, Hanoi harbored deep apprehensions about Nixon’s historic trip. Certainly, since the beginning of the struggle against the Americans, North Vietnam had benefited from the competition between China and the Soviet Union, each communist giant refusing to allow the other to have a monopoly on assisting in an anti-imperialist struggle. Zhou Enlai told his American interlocutors that China’s military aid to Vietnam would continue and that it was in any case the minimum necessary to avoid a deterioration of relations with Hanoi. Zhou expressed his dissatisfaction with the intensity of military cooperation between Hanoi and Moscow. (Yet China had authorized the transfer of Soviet weapons to the DRVN through its territory.) All in all, the Americans left Beijing convinced that China would place its rapprochement with the United States above its support for Hanoi. The Shanghai Communiqué, containing a clause opposing the efforts of any country or group of countries to dominate the Asia–Pacific sphere, constituted an implicit condemnation of Soviet intentions, as well as of Moscow’s alliance with the DRVN. Nixon’s China visit removed one of the key reasons for US intervention in the Vietnam War: to isolate China and stem the spread of Maoism.Footnote 37

From this point on, China granted more latitude to US actions in Vietnam, although its support for Hanoi did not waver. In 1968, when Hanoi had entered into negotiations with the United States, China had reduced its military assistance to show its disapproval. Four years later, Beijing increased its military assistance as an incentive to negotiate. Appearances were deceptive, however. The increase in Chinese military aid was only a consolation prize offered by Beijing to Hanoi, a sort of meager compensation for Beijing’s rapprochement with the United States, which constituted a clear diplomatic defeat for the North Vietnamese. Still, for the Americans, the effort paid tangible dividends. Thanks to triangular diplomacy, a Kissinger aide later wrote, the United States was “at last free to use all our forces to end the war.” With a touch of exaggeration, the phrase was accurate.Footnote 38 Since President Johnson had suspended sustained bombings in November 1968, North Vietnam had remained virtually free of airstrikes. During an NSC meeting on May 8, 1972, in which the president decided on the mining of Hải Phòng and bombing in the Hanoi area, his close advisor, Treasury Secretary John Connally, said in support of these actions: “It is inconceivable to me that we have fought this war without inflicting damage on the aggressor. The aggressor has a sanctuary.”Footnote 39

On March 30, 1972, Hanoi launched its so-called Spring or Easter Offensive, as three divisions, supported by three hundred tanks and Soviet-made 130mm recoilless guns, moved into South Vietnam from bases in North Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Of the DRVN’s thirteen divisions, twelve would eventually be involved in the operation. It was a trident attack, on almost every possible front. It was also a conventional, army-on-army attack that broke with the guerrilla warfare structure that had characterized the conflict until then. For these two reasons, it quickly became apparent that that offensive might determine the outcome of the war.

Nixon was now determined not to hold back any longer. “We must punish the enemy in ways that he will really hurt at this time,” he wrote to Kissinger. “I intend to stop at nothing to bring the enemy to his knees.”Footnote 40 Operation Linebacker, in at least two respects, was an opportunity to reuse old strategies and plans. First, as in the case of Rolling Thunder, the objective was to attack military targets to break the North’s military capabilities. The fundamental difference with Rolling Thunder was that the hesitations, restrictions, or pauses that had characterized the earlier campaign would be lifted. Nixon summarized his thinking in a memorandum to Kissinger on May 10:

We have the power to destroy the war-making capacity [of North Vietnam]. The only question is whether we have the will to use that power. What distinguishes me from Johnson is that I have the will in spades. If we now fail it will be because the bureaucrats and the bureaucracy and particularly those in the Defense Department, who will of course be vigorously assisted by their allies in State, will find ways to erode the strong decisive action I have indicated we are going to take. For once, I want the military and I want the NSC staff to come up with some ideas on their own which will recommend action which is very strong, threatening, and effective.Footnote 41

Launched on May 10, Operation Linebacker started under the name Rolling Thunder Alpha and lasted until October 22, 1972. It consisted of more than 9,000 sorties (air missions) during which 17,876 bombs were dropped, or approximately 150,000 tons of explosive. This represented a quarter of the tonnage that had been dropped in three years of Operation Rolling Thunder.Footnote 42 B-52 strategic bombers went into action on June 8 and carried out an average of thirty flights daily until October. An important technical innovation was the use of so-called smart bombs, guided by laser and dropped by F-4 and F-111 aircraft. In his memoirs, Kissinger described the decisions of May 1972 as “one of the finest hours of the Nixon presidency.”Footnote 43 Following the onset of the bombing, a surprised DRVN official noted that “Nixon managed to do in ten days what Johnson had taken two years to accomplish.”Footnote 44

The American president’s boldness paid off. Linebacker shattered the communist offensive, which for all intents and purposes ended in June. By then, the North Vietnamese troop presence below the 17th parallel had grown considerably, accentuating a “leopard-skin” situation in the South, but neither Huế nor An Lộc had fallen, and a counteroffensive was underway in Quảng Trị, which was retaken by ARVN forces in early September.Footnote 45 A ranking communist official felt that as the summer progressed it became apparent that the losses of the North and its NLF allies were prodigious and that territorial gains could not be held. Questioned by members of the French Communist Party in the aftermath of all this, Hanoi Politburo member Lê Đức Thọ explained that Hanoi had been caught completely off guard by the firmness of Washington’s military response: “We had considered this possibility, but we finally dismissed it as impossible during the year of trips to Beijing and Moscow and the presidential elections.”Footnote 46 Adding insult to injury for Hanoi, the Chinese and the Soviets themselves reacted only mildly to Nixon’s dramatic escalation of the air war. In Thọ’s view, underestimating Nixon had been “a mistake, but not a catastrophic one.” To repair it, Hanoi had to slow the pace of military operations and, to achieve a “political victory,” intensify diplomatic operations. The military stalemate, the impossibility of winning by arms, and the determination of the North Vietnamese to reunite the peninsula under their rule forced them to consider this prospect as possibly inevitable.

Kissinger met with Lê Đức Thọ in France on three separate occasions between July 19 and August 14, 1972. At each meeting, Kissinger found his interlocutor in a much better mood and far more open to a negotiated solution than previously. Thọ no longer insisted on a halt to American bombings of the North before the finalization of an agreement; he merely mentioned that such a gesture would facilitate the peace process.Footnote 47 Kissinger proposed a four-month ceasefire, to be overseen by an international commission. During this time, a final settlement would be negotiated between and among the parties. An American withdrawal would come as soon as the commission was formed. Northern forces were to remain in place in the South, indefinitely. On July 19, during the longest negotiating session ever held – lasting six and a half hours – Thọ gave up the demand to see Thiệu’s regime deposed. He also dropped the demand for a deadline for the withdrawal of American forces. However, he persisted in demanding a coalition government, not just a tripartite election commission.Footnote 48 This last demand frustrated Nixon, who suddenly questioned the usefulness of negotiations. Unlike Kissinger, the president came to believe that the United States would negotiate from a stronger position after the upcoming November 1972 presidential elections. Nevertheless, he allowed Kissinger to continue the negotiations until then.

Operation Linebacker continued despite the resumption of peace talks. Nixon refused to repeat the mistakes of his predecessor, who had repeatedly paused the strikes in hopes that that would encourage Hanoi to negotiate earnestly. Even as the meetings between Thọ and Kissinger were in full swing, the United States intensified Linebacker operations, including in Route Package 6B, that is, the Hanoi area. The deployment to Thailand of forty-eight F-111s capable of delivering laser-guided bombs added another extra weapon to the American arsenal in September 1972.Footnote 49

It was in this context that Kissinger and Thọ reached a first tentative agreement. On October 8, Thọ presented Kissinger with a complete draft agreement. Such a document had never been presented before by either side. Entitled “Agreement to End the War and Restore the Peace,” it contained significant concessions. Most importantly, Hanoi dropped its demand for the removal of South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu before a ceasefire took effect and, along with that, its demands for, first, a coalition government and, second, a veto over the composition of the transitional government in the South. In return, Thọ insisted on the establishment of an “administrative structure” called the National Council for National Reconciliation and Concord (NCNRC) to oversee the implementation of the agreement after the ceasefire. On October 13, in light of Hanoi’s flexibility in the peace talks, Nixon ordered the de-escalation of the bombing of the North and, a few days later, halted entirely strikes above the 20th parallel as a gesture of goodwill. A total halt to bombing of the North, Nixon insisted, would only take place after the two sides reached a final agreement.

After the North, the South

Kissinger subsequently described his October meeting with Lê Đức Thọ at Gif-sur-Yvette, at the former home of painter Fernand Léger bequeathed to the French Communist Party, as the most moving moment of his career:

Most of my colleagues and I understood at once the significance of what we had just heard. I immediately asked to adjourn the meeting, and [Winston] Lord and I shook hands and said, “We did it.” Haig, who had served in Vietnam, said with emotion that we had saved the honor of the men who had fought, suffered, and lost their lives there. To be sure, there were still many unacceptable elements in Lê Đức Thọ’s draft. And some of my colleagues, such as John Negroponte, were sure to point this out during the half hour that followed his presentation. However, I knew that this program was based on a cease-fire, the withdrawal of U.S. forces, the release of prisoners, and an end to infiltration – that was the basic program we were offering and that we have called essential since 1971.Footnote 50

Before returning to Washington from Paris, Kissinger jokingly but presciently told Thọ that the men were now bound to succeed, although it might take a little more time. At a minimum, they might succeed in uniting all the Vietnamese factions against the US national security advisor. To an extent, that is what happened. Unlike Nixon, Kissinger underestimated and miscalculated Thiệu’s reaction to news of the draft settlement. By then, Kissinger was much more eager to reach an agreement than Nixon, who still felt it was preferable to wait until after the upcoming elections. The president warned Kissinger that the agreement “could not be a forced marriage” for President Thiệu. As it turned out, the latter was revolted by news that an agreement had been reached behind his back. American emissaries in Saigon, including Kissinger himself, did their best to convince the South Vietnamese president that the deal was a good one, to no avail. At one point, Thiệu confided to an aide that he wished he could punch Kissinger “in the teeth.”Footnote 51 Seeking to reassure Thiệu, Kissinger claimed that Washington did not seek a face-saving “decent interval,” that is, a short period between the time US forces left and Saigon inevitably collapsed; this was a “decent agreement.”Footnote 52 Admittedly, the Americans had blundered. For example, Thiệu first found out about the October draft agreement not from the Americans, but through documents captured from the enemy. Thiệu especially opposed the idea of a reconciliation council and, above all, Hanoi’s right to keep its own troops in the South after a ceasefire.

Nevertheless, the mass of declassified materials attests to the very extensive efforts made by the Americans to win Thiệu’s consent. From this point of view, one can agree with Pierre Asselin’s analysis: if Nixon had wished to create nothing more than a decent interval between the withdrawal of US troops and the fall of the Saigon government, he would have ignored President Thiệu’s refusal and signed a bilateral agreement with Hanoi. Nor would he have ordered Kissinger to resume negotiations with Hanoi in November and submit to Thọ no fewer than sixty-nine modifications desired by Saigon (which Kissinger himself thought was “a major error”!). Thus, concluded Asselin: “Nixon and Kissinger did not seek an agreement that would provide them with a decent interval before the collapse of the South, but an agreement that gave them hope, at the very least, of maintaining the status quo.”Footnote 53

US–DRVN negotiations in November and early December ended in stalemate, leading an exasperated Kissinger to call the Vietnamese, in front of Nixon, “a bunch of disgusting shits” who made the Russians “look better, just as the Russians make the Chinese look better when it comes to responsible and honest negotiation.”Footnote 54 On December 14, 1972, concluding that the political price to be paid would be the same for high- or low-intensity airstrikes, a vexed Nixon ordered the resumption of US bombings of the DRVN north of the 20th parallel. He also sanctioned the use of B-52s over Hanoi and Hải Phòng. The proposed campaign of renewed bombings, code-named Linebacker II, had two main objectives: on the one hand, to destroy the will of the North Vietnamese to fight, and, on the other, to demonstrate to Saigon that, in accordance with what had been promised on many occasions, the United States was determined to strike the North very severely in the event of noncompliance with the clauses of the agreement. Between December 18 and 29, the “Christmas Bombing,” as the press dubbed Linebacker II, resulted in the dropping of approximately 15,000 tons of bombs on the North by B-52s, while fighter-bombers, including F-111s, dropped another 5,000 tons.Footnote 55 On December 26, while condemning the “extermination bombings,” Hanoi contacted Washington to resume the negotiations. The First Secretary of the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP), Lê Duẩn, later admitted that Linebacker II had succeeded in destroying the economic foundations of his country. On the American side, heavy losses, including several B-52s, made the continuation of hostilities similarly unsustainable. When negotiations reopened in January 1973, both sides were desperate for an agreement, any agreement.

The Paris Peace Accords

The Agreement to End the War and Restore the Peace in Vietnam was signed on January 27, 1973 in Paris. Fundamentally, it called for the withdrawal of all US forces from Vietnam, the release of all POWs, the continued presence of North Vietnamese troops below the 17th parallel, the preservation of the Saigon regime, and the resolution of all remaining political matters by the Vietnamese parties themselves after the ceasefire took effect. The keystone of this “Phony Peace” was the threat of US reintervention in the event of noncompliance by Hanoi and its armies. The bombing of Cambodia, which continued until it was banned by Congress in August 1973, was intended as much to fight the communist Khmer Rouge as to demonstrate to Hanoi the costs of violating the agreement. None of that mattered in the end, as the agreement was violated before the ink on it had even had time to dry.Footnote 56

In retrospect, it is necessary to underline the considerable weight of the internal determinants and parameters that Nixon had to consider to achieve his objective of “peace with honor.” Nixon’s policy was altered at crucial moments by various domestic constraints: in 1969, the peace movement, and in 1972–3, Congress. By making the choices he did in 1969, Nixon condemned himself to a long war. Under the conditions thus created, he then achieved a peace that was undoubtedly the least bad possible. However, by using the military tool to advance diplomacy, Nixon ended up falling, in a way, into the trap he had always wanted to avoid. Like Johnson, he ultimately proceeded to escalate gradually in Vietnam. In 1969, Duck Hook and another planned bombing campaign called Pruning Knife were cancelled, and Nixon then expanded the war into Cambodia and Laos. Linebacker was launched in 1972, not as an initiative, but as a reaction to the communist Spring Offensive. Prior to that, the Americans had chosen not to carry out preemptive strikes, in part so as not to alienate public opinion. It is true that, thanks to triangular diplomacy and Vietnamization, which in the end weakened the antiwar movement, Nixon and Kissinger succeeded in creating conditions that enabled them to use all the conventional air firepower at their disposal. Linebacker II, the “December blitz,” as the press liked to call it, was the culmination of a gradual escalation. From this perspective, it is hardly possible to say that Nixon and Kissinger struck first and then negotiated. Rather, the opposite occurred.

Therefore, one must go further than one of Pierre Asselin’s central theses. Asselin disputes the ironic and famous criticism of the American diplomat John Negroponte, for whom the United States bombed its Northern enemies until they were forced to accept their own concessions. This judgment, Asselin wrote, reflects an ethnocentric view of American diplomatic history and the idea, in this case, that the United States acts and other peoples and nations react. This was not the case during the Vietnam War, where the aspirations of both Thiệu and the South were taken into account. More generally, the United States, in many respects, including and especially in the conduct of military operations, reacted, and its policy was shaped by domestic determinants (the antiwar movement, growing opposition from Congress, etc.) or external ones such as Hanoi’s Spring Offensive and Thiệu’s demands for a ceasefire agreement. In launching Linebacker II, Nixon and Kissinger knew that they had to reach an agreement before the new legislature began, as the November elections had significantly strengthened the ranks of antiwar opponents in Congress. By then, ironically, the antiwar movement in the United States had all but disappeared. The spring 1971 mass demonstrations against the intervention in Laos were the last of their kind. But now Nixon’s foreign policy faced two other domestic determinants: the increasingly intractable opposition of Congress, on the one hand, and the Watergate scandal, on the other.

The return of the last American POW from Vietnam on March 27, 1973 deprived Congress of a core reason to keep supporting the war. That same month, the United States resumed bombings on the Hồ Chí Minh Trail in Laos and Cambodia. Even as Nixon proclaimed that he was ready to bomb the North again, in the spring his legal advisor, John Dean, began to work with prosecutors on the Watergate case. On June 29, 1973, the appropriations bill passed by Congress, and then signed by a weakened Nixon, prohibited the use of funds to “directly or indirectly support combat activities in or over Cambodia, Laos, North Vietnam and South Vietnam or off the coast of Cambodia, Laos, North Vietnam and South Vietnam.” The Appropriations Act also prohibited the use of funds released by any other enactment for these purposes after August 15, thereby removing any credibility from Nixon’s threats to use force to enforce the Paris Agreement.Footnote 57 Senator George McGovern later said that June 29 was “the happiest day of his life.”Footnote 58 Political scientists called that same day “the Bastille Day of the Congressional Revolution,” the day when “the President of the United States recognized the right of Congress to end US military involvement in Indochina.”Footnote 59 Finally, on November 7, 1973, Congress overrode Nixon’s veto of the War Powers Act, effectively ending the “imperial presidency.”Footnote 60

Conclusion

What can we learn from all of this? In The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy, Jussi Hanhimäki drew a harsh assessment of the war’s exit orchestrated by Nixon and Kissinger. Hanhimäki admitted that their policy deprived the Vietnam question of its status as a major element of American political life, especially after the return of the POWs in 1973 and in the context of détente and the opening-up of China. While the nation was on the verge of civil war, Nixon and Kissinger had brought back calm. But at what cost? Hanhimäki speaks not of a “peace with honor” but of a “peace with horror.” In his eyes, American policy resulted in a loss of credibility and a bitter taste of betrayal. Why? Because Nixon and Kissinger’s planetary vision of international relations led them to consider local conflicts only through the prism of triangular diplomacy and the superpowers, even if it meant trying to get rid of them by all means if they interfered with their global aims. With dramatic consequences:

The Americans left behind a situation ripe for further turmoil rather than even a tentative peace. After the American withdrawal, the entire subcontinent gradually descended into a new vortex of violence that would only temporarily be concluded two years later. With the American presence gone, the competing interests of the various warring parties in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, as well as the growing Sino-Soviet interest in safeguarding their respective influence in the region only added fuel to the subcontinent’s fire.Footnote 61

Did the Americans, however, create the conditions for this chaos? Maybe. Hanhimäki’s assessment seems to add credence to the domino theory. Indeed, with the “fall” of Saigon in April 1975, communism extended its bloody grip on the region. Can we affirm, as William Shawcross did, that by intervening in Cambodia in 1969 the United States paved the way for the Khmer Rouge genocide?Footnote 62 Kissinger himself has vehemently opposed this idea. In the last volume of his memoirs, for example, he wrote that the idea that the American bombings in Cambodia were responsible for all the evils of Cambodia can probably be explained by the fact that they were the only ones in Indochina that were not initiated by either Kennedy or Johnson, and that, in any case, it is as absurd as the one that would make the British bombing of Hamburg the cause of the Holocaust.Footnote 63

In Vietnam, Nixon and Kissinger undoubtedly arrived at the least bad possible solution, as some authors, including William Bundy, grant them. In A Tangled Web, Bundy writes of the Paris Agreement, not without wisdom, that despite its imperfection “almost certainly, no better terms could have been reached. Among the many writings on the war, very few have attempted to establish how well the task was accomplished.”Footnote 64 By January 1973, Southeast Asia had, very temporarily, regained its true scale for US policy: a small peninsula at the end of a huge continent. The “Phony Peace,” however, would soon turn into open warfare.

“In retrospect, it appeared like a large chess game of moves and counter moves.” So read a 101st Airborne Division “lessons learned” report from fighting near the A Shau Valley, a strategic corridor linking South Vietnam to the Laotian border and Hồ Chí Minh Trail beyond. It seems unlikely, however, that the American soldiers defending Firebase Ripcord in the summer of 1970 felt they were playing chess. Charged with protecting a small hilltop at valley’s edge, accessible only by helicopter, they endured People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) ambushes, mortar barrages, and artillery fire for nearly a month. When the siege of Ripcord ended, seventy-five Americans lay dead. Games normally do not come at so high a cost.Footnote 1

To senior US military commanders, the fighting near A Shau surely made operational sense. The valley had long been a conduit for Hanoi to send critical manpower replacements and supplies into South Vietnam. The 101st Airborne had seen heavy fighting there in 1969, most infamously at “Hamburger Hill” in May. One year later, troubled US commanders again were reading intelligence reports suggesting enemy forces were on the move. They feared the “Warehouse Area,” the valley’s nickname, might serve as a launching pad for strikes into South Vietnam’s coastal lowlands and population centers. With these concerns in mind, Operation Texas Star took shape. The 101st would conduct “protective reaction” missions in the A Shau region, with newly established firebases providing artillery cover to US and South Vietnamese infantry troops on the valley floor below. Ripcord was the pivotal base along this protective chain.Footnote 2

Almost immediately, though, the Americans met resistance while establishing their firebases. Commanders called in airstrikes in late March to “soften up the area,” and by early April, Ripcord was turning into a heavily bunkered stronghold. Yet neither airstrikes nor patrols drudging through the valley’s jungles made any headway in dislodging enemy forces from the mountaintops surrounding the firebase. By July, Ripcord was under siege. As North Vietnamese mortar and artillery shells descended on American GIs, US commanders ultimately decided to postpone a planned offensive into the valley and evacuate the area. For the second time in two years, American forces had fought hard in A Shau, only to cede bloodied ground back to the North Vietnamese. As B-52 bombers flew in to obliterate what was left of Ripcord after its abandonment, one US officer laconically stated that “we didn’t want to leave anything behind that the enemy could use.”Footnote 3

With the Nixon administration already withdrawing from a long and costly war, the fighting around Ripcord would rank among the last major ground combat operations conducted by the US armed forces in South Vietnam. Yet larger questions remained as the Americans departed the A Shau valley. Were operations there successful? Who had “won” given that so much American blood had been spilled for a plot of land almost immediately abandoned? Officers would argue then and later that the “occupation of Ripcord provided a barrier to possible [North Vietnamese Army, NVA] plans to attack the coastal lowlands” and “absorbed considerable NVA strength and military stores.” Others were far less charitable in their assessments. Writers in Newsweek described the Ripcord fighting as a “painful” operation and wondered aloud why “American soldiers had been asked to set up a fire base in the midst of an enemy stronghold to begin with.” Indeed, some soldiers felt they had been left “hanging” as “bait.” That the US command in Saigon discouraged reporters from visiting Ripcord did little to foster a sense of optimism about what lay ahead.Footnote 4

The A Shau valley fighting in 1970 serves well as a microcosm for evaluating the enduring problems Americans faced as they withdrew from their war in Vietnam. At all levels, from tactical to strategic to political, uncertainty persisted over how the conflict would end. Military commanders had to consider not only troop withdrawal rates, but the level of enemy activity and the prognosis of Vietnamization, the phrase used for gradually handing the war over to their South Vietnamese allies. Diplomats had to balance peace negotiations with the Nixon administration’s larger aims of rapprochement with China and the Soviet Union. All the while, the White House sought to end its war on terms that preserved US credibility around the globe.Footnote 5 In all these areas, the terms “victory” and “defeat” remained imprecise and constantly in flux. Indeed, a setback in one area might hold lasting consequences elsewhere. No wonder the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) worried that “adverse publicity” from Ripcord “might well have jeopardized the entire Vietnamization program.”Footnote 6

These uncertainties matter because they influenced the timing of and ways in which US forces withdrew from a conflict that would not be terminated once Americans departed South Vietnam. Near war’s end, evaluating the progress and effectiveness of US strategy proved as bewildering as it had been nearly a decade earlier. Every new initiative seemed only to produce a frustratingly new state of equilibrium. Any successes in pacification seemed only to increase the Saigon government’s dependence on American aid. Any accomplishments in Vietnamization seemed only to hasten calls for US troop withdrawals, leaving an exasperated Henry Kissinger in Paris to argue he was losing leverage over his North Vietnamese negotiating partners. And, ultimately, the flawed strategic process of exiting Vietnam’s war set the foundation for future debates over whether the American armed forces could claim victory, be forced to acknowledge defeat, or concede they had achieved, at most, a costly stalemate against a determined enemy.Footnote 7

“One War,” but a Winning One?

By mid-1968, American ground combat forces had been operating in South Vietnam for three full years. Despite massive efforts – US troop strength had reached 485,600 by the end of 1967 – the best that the Americans, the South Vietnamese, and their allies could achieve against their communist foes was a bloody stalemate. It was not for lack of trying. General William C. Westmoreland, MACV’s commander, had developed a comprehensive political–military strategy that sought to parry enemy military offensives, support Saigon’s pacification efforts, train South Vietnamese defense forces, and build a logistical infrastructure to sustain a major ground and air war. Still, neither side could break the deadly impasse. When Hanoi launched its Tet Offensive in early 1968, seeking a decisive military victory and popular uprising in the South, the result was only a continued stalemate. True, the Southern communist infrastructure had been nearly destroyed, but the devastation to the countryside and displacement of some 600,000 South Vietnamese civilians surely offset any credits to the allied ledger.Footnote 8

With the transition to a new MACV chief in the summer of 1968 came hopes of a fresh strategic approach yielding improved results. Westmoreland’s West Point classmate, Creighton Abrams, had amassed an impressive resumé, from his service with Patton in World War II to becoming MACV’s deputy commander in 1967. One year later, he took over a war that appeared to many Americans no longer worth fighting. Yet expectations rose, if only briefly. As one fellow officer recalled, “Abe” possessed that “rare quality, common sense, the knack of going straight to the heart of the problem, and insisting on a simple and workable solution.” But Abrams also bristled under the political restrictions placed upon him after the bloody Tet battles. Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford, for instance, correctly gauged the political winds and knew military commanders in Vietnam would have to keep casualties down if they were to maintain popular support back home. The loss of over 14,500 American lives in South Vietnam during 1968, though, suggested Abrams might not have the ability to singlehandedly manipulate events as his enthusiasts predicted.Footnote 9

The new MACV commander certainly spoke in terms that appeared pioneering. He espoused a “one war” approach, in which the allies would respond to an enemy working along numerous “levels” or “systems.” Abrams could not ignore the military aspect of the war. But he also had to bring the South Vietnamese armed forces to an “acceptable level of proficiency,” all while supporting pacification and countering communist “attempts to subvert people in remote areas.” As the general instructed his subordinate commanders, “All types of operations are to proceed simultaneously, aggressively, persistently, and intelligently … never letting the momentum subside.”Footnote 10 Such language fit Abe’s forceful personality. Yet just below the surface, the “one war” approach bore strong resemblance to Westmoreland’s own “balanced” or “two-fisted strategy.” Both commanders realized they were fighting a complex war, the outcome of which depended upon political matters as much as military ones. In truth, few truly innovative strategic concepts emerged during Abrams’ tenure as MACV commander.Footnote 11

Champions of the Massachusetts native, though, long have advocated that Abrams turned the war around in short order. With hagiographic grandeur, historian Lewis Sorley, for example, has argued the general changed tactics “within fifteen minutes” of taking command, fought a “better war,” and ultimately achieved victory in the spring of 1970. To Sorley, MACV abandoned the misguided “search-and-destroy” concept – and the grisly body-count metrics – to instead focus on “clear-and-hold” operations aimed at pacifying the countryside.Footnote 12 But adulation makes for bad history. In reality, Abrams, at best, altered US military strategy along the margins. Search-and-destroy operations remained a vital component of MACV’s approach, and new scholarship demonstrates clearly that Abrams’ attitude toward pacification was “just as reliant on heavy firepower and main-force operations as it was under Westmoreland.” In short, there was “no fundamental change in strategy.” The new MACV chief may have thought of the war as a single yet multifaceted conflict, but the “one war” term did not herald a major shift in the war’s prosecution.Footnote 13

Nor did MACV operations prove any more successful than those directed by Westmoreland. Abrams surely emphasized pacification efforts inside South Vietnam, taking advantage of casualties suffered by the National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) and its armed wing, the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF), in particular during the 1968 Tet battles. And Hanoi did acknowledge that, after Tet, the “political and military struggle in the rural areas declined and our liberated areas shrank.” Yet the allies came up decidedly short in achieving their 1969 Combined Campaign Plan goals. Thanks to increased communist infiltration rates along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail, MACV was unable to “inflict more losses on the enemy than he can replace,” for years a goal of the Americans and South Vietnamese.Footnote 14 (Abrams also had to contend with political fallout from costly military engagements, like the one suffered at Hamburger Hill in May 1969.) Senior US officers grumbled that combined operations between the two allies remained “superficial” at best. The US ambassador to South Vietnam, Ellsworth Bunker, additionally worried about the Saigon government’s post-Tet “crisis of confidence.” All the while, Abrams continually looked over his shoulder for the first announcement of American troop withdrawals he knew was coming soon.Footnote 15

The rising infiltration rates along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail – over 100,000 fresh troops entered South Vietnam in 1970 alone – intimated the war’s changing character to more conventional operations. Still, Abrams sensed an opportunity to strengthen a key pillar of his “one war” approach. With the NLF’s armed forces dispersed and demoralized after Tet, their credibility damaged, MACV initiated an “accelerated pacification campaign” in hopes of recovering lost ground. As in the past, though, such plans relied on brutal tactics which seemed only to further unravel South Vietnam’s social fabric. Those living in rural areas saw their homes destroyed and crops demolished, while refugee numbers surged and food shortages increased. In Abrams’ headquarters, senior military planners were coming to a grim realization. Temporary gains in violent pacification were one thing; long-lasting successes in genuine security and nation-building, quite another.Footnote 16

The inconclusive returns on pacification investments denoted unresolved issues in assessing the political aspects of this vital program. How could MACV nurture and evaluate the political loyalties of the rural population, not to mention those living in urban areas? Senior US officers never reached consensus. While one general argued that “by 1970 we had really begun to make pacification work,” others were far less sanguine. One corps commander thought that socioeconomic development was “the area of greatest failure” within pacification programs, while another three-star general believed the campaign against the insurgency’s political infrastructure was “somewhat disappointing.”Footnote 17 Moreover, diminishing popular support for the NLF did not necessarily translate into increased cooperation with South Vietnam’s government. Coercive pacification may have damaged the communist insurgency’s political network, the so-called Viet Cong infrastructure, but it did not help cultivate bases of support for the Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu regime in Saigon. All told, it is difficult to accept Nixon’s claims that pacification “worked wonders in South Vietnam.”Footnote 18

North of the demilitarized zone, Hanoi also faced uncertainty after its failure to achieve a decisive military victory in 1968. Lê Duẩn, the Politburo’s general secretary, grudgingly embraced a more restrained “talking while fighting” policy that accentuated the war’s diplomatic aspects. With the NLF/PLAF losing 80 percent of its fighting force during the Tet battles, he had little choice. Thus, in 1969, the communists reverted to guerrilla operations and terrorist attacks, forcing Abrams to adjust by increasing small-unit patrolling across much of South Vietnam. Moreover, communist party leaders now had a morale problem on their hands. A political cadre wrote of a situation that had “deteriorated alarmingly, just like soap bubbles exposed to the sunlight.”Footnote 19 Another admitted that “1969 was the worst year we faced. … There was no food, no future – nothing bright.” No wonder that summer communist cadres launched a “wave of political training” to help maintain the revolutionary spirit. If Hanoi was going to sustain the war effort, military actions needed to be more cautious while Politburo leaders reemphasized the struggle’s political dimensions.Footnote 20

A sense of renewed stalemate pervaded both sides as the long Tet Offensive played out through 1968 and began anew with a fresh, though much diminished, communist offensive in early 1969. As bad as the struggle in South Vietnam appeared from the NLF perspective, there were few bright spots within MACV assessments. US casualties throughout the post-Tet period remained high. Indeed, in February 1968 alone, there were 2,124 Americans killed in action, the highest monthly total to that point in the war. Worse, Department of Defense analysts concluded that after the 1968 offensives, the “communists held the basic military advantage in South Vietnam because they could change the level of American battle deaths by changing the frequency and intensity of their attacks.” If Abrams truly was fighting a better war, it seems worth asking why the communists continued to hold the tactical initiative despite major setbacks during and after the Tet Offensive.Footnote 21

By early 1969, Abrams also had to confront major political decisions leading to the first withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam that spring. While MACV focused on improving the capabilities of South Vietnam’s defense forces, White House officials pressed Abrams for plans to redeploy his soldiers back home. The ensuing debates over how best to “de-Americanize” the war ultimately would pit Abrams against the Nixon administration and bring to surface civil–military tensions that would bedevil American leaders for the war’s remainder. Perhaps the most vocal advocate for Vietnamization was Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird. A former Wisconsin congressman, Laird realized the limits of domestic public support sustaining the administration’s Vietnam policies. Both he and the president realized, in Nixon’s words, the “reality” of “working against a time clock.” Not surprisingly, Abrams campaigned for more time – for pacification efforts to take hold; for improvements in training South Vietnamese regional and popular forces; for more military operations against communist forces. The White House, however, only became increasingly frustrated with a senior general who appeared to be dragging his feet.Footnote 22

Care should be taken in judging Abrams too harshly here. Neither he nor his chief subordinates were able to evaluate accurately how well South Vietnamese forces would perform once their American allies departed. After Tet, as Abrams reported, all they understood was that there were “major changes in the relationship between supported and supporting.” One senior officer recalled that a “confusing ambiguity surrounded the concept of Vietnamization.”Footnote 23 All the while, and much to Abrams’ chagrin, the CIA and MACV staffs reached vastly different conclusions over how well their Vietnamese partners were progressing. It did not help matters that neither agency accurately could predict the pace of US withdrawals or changes to the enemy’s military strategy. To a concerned Abrams, it appeared as if the Americans were departing faster than their allies could improve. He was not alone. A 1974 survey of over 170 US Army generals found that a full 25 percent were “doubtful” that South Vietnam’s armed forces would survive a “firm push” by communist forces in the near future.Footnote 24

Such misgivings put into question how well MACV was accomplishing its Vietnamization mission. Laird most certainly wondered. In the summer of 1969, he encouraged revising Abrams’ mission statement to better reflect changes in Nixon’s policies and to better show “what our forces in Southeast Asia are actually doing.” In mid-August, the administration handed MACV new orders. Instead of defeating the enemy and forcing its withdrawal from South Vietnam, as had been the objective during the Johnson years, MACV now would provide “maximum assistance” to its Vietnamese allies. The goal no longer was military victory. Rather, Abrams would provide support – to Vietnamization, to pacification, and to reducing the flow of supplies to the enemy – so South Vietnam’s people could “determine their future without outside interference.” As one veteran recalled, Abrams was taking on an “unenviable job.” Far from MACV headquarters, US soldiers and marines still out on combat missions began speculating how their continued exposure was worth the risks if victory no longer remained the goal.Footnote 25

Abrams’ first year in command left fundamental problems unresolved and a crucial question unanswered – how durable was the Saigon regime? No one knew. As the New York Times reported in June 1969, the “South Vietnamese armed forces appear to be doing a better job in battle now than ever before, but the day when they will be able to stand alone does not seem to be in sight.” A chasm remained between rural and urban areas, holding vast social consequences for a Thiệu government searching for some sense of political stability. Indeed, photojournalist Larry Burrows found that an “extraordinary cynicism pervades South Vietnam.”Footnote 26 Nor could any senior US officials find consensus over the true level of security in the Vietnamese countryside. In one province alone, Quảng Trị, MACV identified at least nine communist infantry regiments in June 1969. Thus, either from a social, political, or military standpoint, these early years of what Abrams deemed a “rearguard action” left Americans no closer to determining whether or not they ultimately would achieve “victory” in Vietnam.Footnote 27

Nixon’s Turn: Expanding a War to Withdraw from It

Richard M. Nixon recalled that when he first entered office, he “knew a military victory alone would not solve our problem” in Vietnam. Intent on changing the United States’ relationship with China and the Soviet Union, the new president recognized he could not simply abandon the long-standing US goal of supporting an independent, noncommunist South Vietnam. Yet both Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, understood the stalemated Southeast Asian conflict was doing little more than exhausting American resources. (The war’s cost then was approaching $30 billion annually.) These inherent tensions, if not contradictions, would be a hallmark of Nixon’s Vietnam strategy. The president sought to combine diplomatic initiatives with “irresistible military pressure” to win the war, yet simultaneously disengage from a conflict no longer central to United States foreign policy.Footnote 28

Hoping to alleviate these policy tensions, Kissinger established a special studies group evaluating the war while Nixon issued National Security Study Memorandum 1 (NSSM 1) directing key agencies to report on their prognoses. The results were far from encouraging. None of the key respondents – the Department of State, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCF), the CIA, or MACV – agreed on much. Optimists believed the enemy had suffered crippling losses over the past two years, providing the United States an advantage in any forthcoming peace negotiations. Skeptics saw a stalemated conflict from which a compromise settlement was the likeliest outcome. Only on one major point did the agencies concur. The South Vietnamese armed forces would be unlikely to withstand a concerted enemy attack without continued American support. Kissinger admitted the NSSM 1 process shed light on the underlying “perplexities” of assessing the war in Vietnam and came to a grim conclusion: “There was no consensus as to facts, much less to policy.”Footnote 29

Nixon, however, did not wait for Kissinger’s results before laying out a comprehensive strategy. The president believed time favored the communists, who, despite losing the battlefield initiative, could continue the war and keep inflicting casualties on American forces. Worse, as US News & World Report surmised in June 1969, little evidence existed that Hanoi intended to abandon the fight. As Nixon told his National Security Council (NSC) staff that March, “We must move in a deliberate way, not to show panic.” Deliberate he was, at least in design. The president’s resultant five-point plan covered a wide range of initiatives – Vietnamization, pacification, diplomatic isolation of North Vietnam, the gradual withdrawal of US troops, and peace negotiations. As Nixon recalled, his strategy aimed to “end the war and win the peace.”Footnote 30 Yet the very comprehensiveness of such an approach generated its own set of problems. Foremost among them, how could Abrams successfully balance the competing demands of such an all-encompassing strategic construct?

Kissinger shared Abrams’ concerns over US troop withdrawals, fearing cuts in combat strength might weaken his negotiating position with Hanoi diplomats. (They treated negotiations only “as an instrument of political warfare,” Kissinger fumed.) Nixon squared this strategic circle by quietly expanding the war outside South Vietnam’s borders. In March, he authorized the “secret” bombing of North Vietnamese sanctuaries inside Cambodia. Congress was not consulted for fear of igniting protests at home. For the next fourteen months, B-52 bombers dropped more than 100,000 tons of munitions on the nominally neutral country. To keep Operation Menu covered, the administration falsified military records. On May 9, 1969, though, William Beecher of the New York Times broke the story. While Nixon was “pressing for peace in Paris,” the new president also was “willing to take some military risks avoided by the previous administration.” Beecher failed to mention that both Nixon and Kissinger worried how a lack of progress in Vietnam might damage US credibility abroad, a key component, they believed, in altering Cold War relationships with China and the Soviet Union.Footnote 31

If Abrams hoped the Cambodian bombing meant Nixon would allow him to settle the war on the battlefield, he soon would be disappointed. During a June trip to Midway Island, Nixon announced his decision to withdraw the first 25,000 American troops from Vietnam. The following month, now in Guam, the president declared his “Nixon Doctrine,” arguing that the United States must avoid “the kind of policy that will make countries in Asia so dependent upon us that we are dragged into conflicts such as the one that we have in Vietnam.” The announcement left little doubt over where the larger political currents were leading. If the United States was not disengaging from Asia, it certainly was expecting allies there to manage their own security problems. Later in the year, the president addressed the nation on his Vietnamization plans. During a November speech, Nixon was clear – the “primary mission of our troops is to enable the South Vietnamese forces to assume the full responsibility for the security of South Vietnam.” Though he proclaimed the United States would neither betray its allies nor let down its friends, Nixon’s address hardly inspired confidence within the Thiệu regime. Sooner, rather than later, the Americans were leaving South Vietnam behind.Footnote 32

Still, grave concerns over the long-term viability of South Vietnam’s government and armed forces convinced Nixon to go on the offensive. Cambodia proved an inviting target. The overthrow of Prince Norodom Sihanouk by Marshal Lon Nol in March 1970 served Nixon well, for the president could argue he was assisting Cambodia in aligning more closely with the United States. In truth, Nixon hoped to destroy North Vietnamese supply caches and troop sanctuaries along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail just outside of South Vietnam’s borders. Naturally, these goals were related to the president’s withdrawal plans. As the MACV command history relayed, the Cambodian operation was “a catalyst allowing the U.S. to meet more readily its 1970 goals … to continue to Vietnamize the war, lower the number of U.S. casualties, withdraw U.S. forces on schedule, and stimulate a negotiated settlement of the war.” This regionalization of the conflict came not just from Nixon’s fears that “North Vietnam was threatening to convert all of eastern Cambodia into one huge base area,” but from a consensus among Americans that a continuing military stalemate was undermining the entire Vietnamization effort.Footnote 33

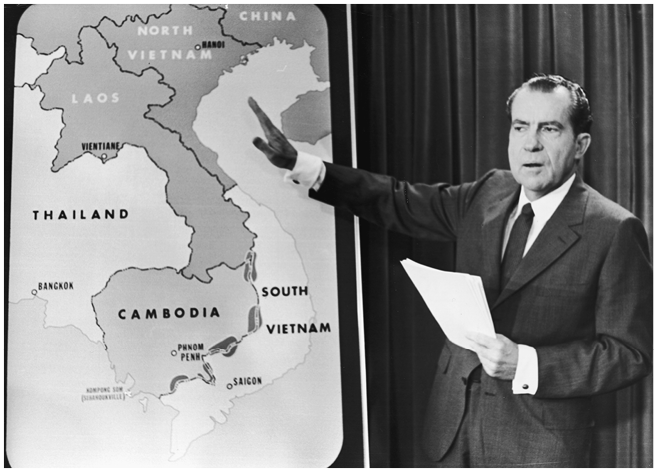

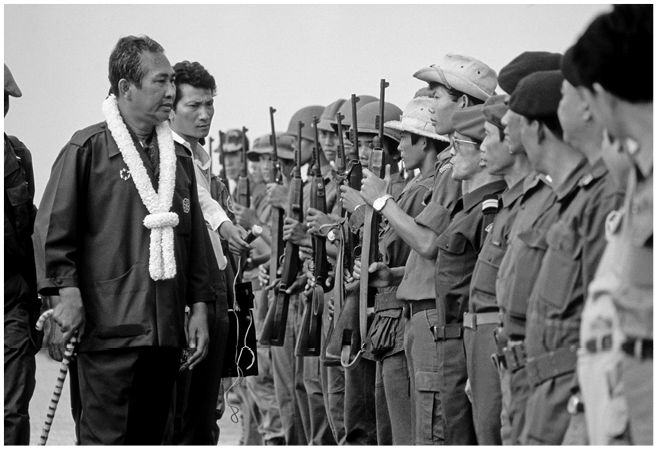

Figure 2.1 Richard Nixon points to a map of Southeast Asia during a nationwide broadcast on the Vietnam War (April 1970).

On April 30, 1970, American and South Vietnamese forces, part of a joint “spoiling attack,” assaulted into the bordering Parrot’s Beak and Fishhook regions of Cambodia. Though expecting the communists would stand and fight to defend their supply caches, the allies quickly found the evasive North Vietnamese retreating farther into Cambodia. Hopes of a decisive military victory quickly evaporated. Disappointed, the allies took comfort in the massive quantities of enemy supplies they had uncovered and destroyed. By MACV accounts, they had captured over 22,000 individual weapons and some 14 million pounds of rice. Nixon believed the operation “dealt a crushing blow to North Vietnam’s military campaign,” while senior military officers judged the incursion “extraordinarily successful.”Footnote 34

Other indicators suggested far more mixed results. Despite the operation’s successes, MACV admitted “problems in security persisted” and that “the enemy was not directly affected by the Cambodian incursion.” Lê Duẩn agreed, reporting in July that “our position on the whole battlefield has been maintained.”Footnote 35 Worse for Nixon, a political firestorm erupted back home when the president addressed the nation as the operation began. A reignited antiwar movement swept across college campuses, with Ohio National Guardsmen killing four students at Kent State and police killing two others at Jackson State University in Mississippi. Congress responded by prohibiting the use of US ground troops outside South Vietnam’s borders, repealing the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and forcing Nixon to set a June 30 deadline on operations inside Cambodia. In the Senate, Frank Church (D-Idaho) protested that “the Nixon administration has devised a policy with no chance of winning the war, little chance of ending it, and every chance of perpetuating it into the indefinite future.”Footnote 36

Unrest on the homefront, however, did not subvert worries inside the White House or MACV headquarters over the strategic balance within South Vietnam, leading to plans for yet another expansion of the war, this time into Laos. Abrams, in particular, hoped an attack on the Hồ Chí Minh Trail would disrupt communist designs for future offensive operations. Yet few policymakers asked how such an assault would solve more pressing problems. As Abrams’ own command historian noted, the challenges of 1971 – “the need to stabilize the economy, the need to continue progress in restoring security and tranquility to the countryside” – were “crucial” to Saigon’s existence. Would an attack into Laos resolve these internal, existential crises? Nor did contemporary military observers grant how rising enemy activity just outside South Vietnam’s borders revealed the temporary nature of allied achievements in Cambodia. Rather, senior commanders like Abrams seemed preoccupied with protesting Nixon’s decision to speed up troop withdrawal timetables to help quiet dissent at home. Once more, civil–military relations were wearing thin.Footnote 37

The subsequent incursion into Laos in early 1971, dubbed Operation Lam Sơn 719, only heightened questions about Vietnamization’s long-term prospects. Maneuvering alone – the 1970 Cooper–Church Amendment forbade US troops from fighting inside Cambodia or Laos – South Vietnam’s armed forces struggled against tenacious PAVN defenders. With rising casualties and over Abrams’ fierce opposition, President Thiệu prematurely halted the offensive, while American aircrews and artillery batteries did their best to cover what journalists soon were calling a “rout.” Nixon, then and later, railed against an unaccommodating media. But soldiers throughout the allied command structure knew they had been dealt a serious blow. One senior US officer reported to Abrams in April that enemy activity remained a “hindrance” to Saigon’s pacification efforts. A South Vietnamese general admitted Lam Sơn had created a “disquieting impact on the troops and population alike.” One young American GI offered a more prosaic critique. To him, the South Vietnamese “got their ass kicked and they are hightailing it back. It’s like us saying, ‘Pack up and run for your life. Everything is going according to plan.’”Footnote 38