A report from a Vietnam War commemoration committee states that over 500 Vietnam veterans are dying every day.Footnote 1 The high mortality rate is generational: if a soldier were 21 in 1968, he would be 75 at the time of writing. The prospect of the passing of this generation of veterans has motivated the commemoration committee to redouble its efforts to gather their oral histories while they remain alive. The passage of time also means that we have reached a transitional moment when knowledge of the war passes from the personal experience of those who fought to history and transgenerational memory.

There has never been an absolute distinction, though, between personal experience and received knowledge; they always interpenetrate. Those who went to war do not constitute a pure fount of unmediated recall: no individual observed every battle; the character of the war differed from region to region of South Vietnam, and from year to year. Unlike World War II, when the troops served for the duration of the conflict, in Vietnam most soldiers served for a one-year tour of duty. (The Marine Corps, projecting an image of toughness, required thirteen months.) A truism among veterans is that Vietnam was not a ten-year war but ten one-year wars fought back to back. Eyewitnesses and participants always relied on reports from others for much of what they knew about the war. For those who served and for the members of their generation who saw the war from the homefront, what they believed and knew about the conflict was always in large part the product of ideologically inflected interpretation, of mediated and mass-mediated knowledge and opinion. This chapter examines the way that our understandings and beliefs have coalesced into conventional forms in the decades since the end of the “American War” – how the “common sense” about the war formed and permeated American culture.

By the time the communist victory in 1975 had reunified the country, the interest of many Americans in Indochina was exhausted. The war had divided and disillusioned them. US President Gerald Ford spoke for many when he declared in late April 1975 that the evacuation of the last US personnel “closes a chapter in the American experience.” Days later, at a news conference, he rejected the concept of learning the lessons of the war, saying that they had already been learned. “The war in Vietnam is over. … And we should focus on the future. As far as I’m concerned, that is where we will concentrate.”Footnote 2

Ford planted a poisonous seed in the minds of the public, though, by asking Congress to send emergency aid to the embattled South Vietnamese. The aid would have done no more than to delay the communist victory, even if it had overcome the logistical obstacles to being delivered at all, but it fed into a “stab-in-the back” myth: the United States and South Vietnam had won the war, but Congress lost the peace.Footnote 3 Many veterans were perplexed by the withdrawal. What had all the effort been for, why had they risked their lives, and why had their buddies been wounded and killed, if the United States would allow its ally to sink? Thinking of the South Vietnamese who had been abandoned to their fate, a former POW said, “All of the people who did work for us over there got screwed. We left so many of them behind. American promises meant nothing any more.” “Now it’s all gone down the drain and it hurts. What did he die for?” a Pennsylvania father asked of his son.Footnote 4

The strong sense of betrayal and loss suffused all sides. While conservatives blamed a weak-willed Congress, the media, and antiwar protesters for undermining the nation’s will to fight, those who had opposed the war believed that the nation had discarded some of its most cherished values when it had tried to impose its will on the fate of the Vietnamese. Not only political activists but also leading journalists, intellectuals, and entertainers expressed a new kind of skepticism about the American government and the nation’s economic interests. Critiques of militarism and imperialism entered the mainstream of public discourse during the war years. Distinguished writers had come to see the war “as an expression of an imperial, racist, bureaucratic and technological Establishment” that brought ruin on the spiritual landscape of the United States as surely as it had devastated Vietnam.Footnote 5 What seemed to be under threat, perhaps lost, was an abiding sense of America’s mission in the world.

The public emerged from the Vietnam War with a profound sense that the nation had done wrong. Whereas in 1967 a substantial majority of the public had thought the United States’ part in the war was morally justified, by the end of the war that had changed. In June 1975, six weeks after the end of the war, two-thirds of a national poll sample said that the United States did the wrong thing in Vietnam. In 1978, almost three-quarters of a sample of the public agreed that “the Vietnam War was more than a mistake, it was fundamentally wrong and immoral.” Up until the mid-1980s, some two-thirds to three-quarters of the public gave similar responses to pollsters, agreeing that the war was wrong, immoral, or both.Footnote 6 No wonder: when American soldiers were found to have killed hundreds of unarmed, defenseless civilians at the village of Sơn Mỹ (an atrocity popularly known as the “Mỹ Lai massacre”), only one American soldier, Lieutenant William Calley, was convicted of a crime. Calley, though, led only one of four platoons that conducted simultaneous massacres in two of Sơn Mỹ’s hamlets. When Calley was convicted and sentenced, the public wrote to the White House and their elected representatives in huge numbers asking for leniency, but not primarily because they believed that Calley was innocent: large majorities believed that acts like the one of which he was found guilty were commonplace in Vietnam, and that higher officers were responsible for such crimes.Footnote 7

After the war, sensibilities were so raw, and the possibility of recriminations so close to the surface, that the nation collectively turned away from the war. Commentators refer to the late 1970s in the United States as a period of “amnesia” about the Vietnam War. But this willful forgetting added to the veterans’ sense of betrayal, leading many to feel they had been disowned. The United States had sent them to fight in a war supposedly vital to America’s national interests, but when it went wrong, the veterans were left to cope on their own with the legacy of defeat and disgrace. The journalist Myra MacPherson, who interviewed hundreds of Vietnam veterans for her book Long Time Passing, said that they felt “an indescribable rage that they, for so long, seemed to be the only Americans who remembered the war’s suffering and pain.”Footnote 8

Confronting the war-induced loss of ideological certainties, the first postwar president, Jimmy Carter, attempted to redefine the nation’s sense of mission and purpose. Grounding a new claim to global leadership on the high-minded concept of human rights, Carter turned away from Cold War orthodoxies and repudiated the support of repressive regimes simply because they were reliable allies in the Cold War. The policies based on this new definition of America’s role in the world unraveled because of international setbacks. While Carter said that the Vietnam War had brought about a crisis of confidence in America, by the end of his presidency, critics blamed Carter himself for the nation’s weakening. They complained about the “Vietnam syndrome”: excessive hesitancy at the prospect of military action, which prevented the United States from projecting its power abroad. Critics charged that the syndrome had made the nation too cautious in its conduct of foreign policy, and that Carter’s moral feebleness had encouraged the nation’s adversaries.Footnote 9

Carter’s successor as president, Ronald Reagan, took a frankly ideological route to overcoming drift and uncertainty. Reagan said that the nation had to rearm, both literally and morally, in order to overcome the failings that had emboldened America’s adversaries around the world. His administration embarked on an arms buildup, with massive increases in arms expenditures. It confronted its socialist adversaries in Central America. But Reagan expressed frustration that in foreign affairs, unlike his economic policies, his efforts to appeal to the public over the heads of their elected representatives were insufficient to overcome congressional resistance to his program. Casting a shadow over his efforts were congressional and public fears of fighting “another Vietnam” in Central America. Towards the end of his time in office, Reagan confided to his diary, “Our communications on Nicaragua have been a failure.” Most people, he said, don’t want to send the “contras” – anticommunist Nicaraguans the administration was supporting – money for weapons. Reagan’s explanation: “I have to believe it is the old Vietnam syndrome.”Footnote 10

Reagan had set out explicitly to overcome the Vietnam syndrome by redefining the Vietnam War as a “noble cause.” What was wrong with the war was not that it was immoral, he asserted, but that weak-willed leaders deprived America’s brave soldiers of the victory their efforts deserved. “For too long,” he said,

we have lived with the Vietnam syndrome. … There is a lesson for all of us in Vietnam. If we are forced to fight, we must have the means and the determination to prevail or we will not have what it takes to secure the peace. And while we are at it, let us tell those who fought in that war that we will never again ask young men to fight and possibly die in a war our government is afraid to let them win.Footnote 11

The defeat was not the fault of the troops: they had fought as bravely and as honorably as any generation of Americans. The implication of his promise for future policy was clear: the government should not restrain itself in its use of force in the way it had done in Vietnam. Reagan was applauded by veterans for vindicating them, but his wish to redefine the Vietnam War as a “noble cause” was divisive.Footnote 12 Far from uniting the public, his outspoken redefinition of the Vietnam War threatened to deepen the fault lines that still fissured the country.

The inability of a “great persuader” like Reagan to lead the country toward a new judgment about the war highlights a crisis of hegemony: most of those whose positions of authority or influence might have shaped public opinion were themselves implicated in the nation’s divisions. Politicians, the media, intellectuals, military officers, strategic thinkers: none of them stood above the ideological fray, and none possessed the rhetorical authority to overcome wartime divisions.

Veterans’ Narratives and the Moral Legacy of the War

The task of helping the nation to come to terms with its divided and troubled memories of the war fell, by default, on the nation’s veterans. The troubling memories they voiced coursed through multiple channels of expression and fed into the social rumination on the war. The principal means of addressing the moral legacy of the war would center on the experience of soldiers, the grit and horror of combat, and the burden of troubled emotion they carried with them from the war.

Literary authors and filmmakers struggled to place the American experience in Vietnam into generic and narrative streams consistent with the national myths through which Americans had long made sense of their place in the world. With some notable exceptions, when veterans wrote about their war, they tended to confine the scope of the narrative to the bounds of a single unit, often of company or platoon size. Their rendering of the war was bounded temporally as well as spatially: veterans’ stories were usually confined to a single individualized tour of duty. The veterans’ narratives rarely endow their time in Vietnam with a militarily decisive objective (such as the equivalent of a D-Day landing). The war was fought without “front lines”: the objective was not to capture and hold territory along a line of advance but to grind down the enemy through attrition and bombing. Uncertain of the strategic purpose of their own and their buddies’ sacrifices, the veterans’ narratives center on the fierce loyalties – and the conflicts – among the troops on the American side, the visceral and bloody realities of combat, the moral quandaries involved in fighting a guerrilla war in the midst of civilians, and encounters with primal, existential questions of life, death, and the formation of the self. In the veterans’ accounts, as the literary critic Philip Beidler put it, Vietnam was “the place where Americans would find out who they really were.”Footnote 13

Vietnam veterans were living embodiments of the nation’s actions in Vietnam. They had borne the risks of combat; they had lived through moments of terror; they faced life-and-death choices in the heat of battle, and they faced the prospect of a lifetime coming to terms with the decisions of a split second. As they confronted their personal memories of the war, their struggles became the moral ground through which their compatriots faced the nation’s experience. Every doubt and quandary that the veteran storytellers entertained put into play the larger-scale questions that their fellow citizens had once shied away from but could revisit on the terrain of the former soldiers’ memories.

Vietnam veterans’ writings were, in ideological terms, all over the map, but this serves to highlight their commonalities. Let’s take two works written by marine platoon commanders in Vietnam, Philip Caputo’s memoir, A Rumor of War, and James Webb’s novel, Fields of Fire. Philip Caputo goes into military service with John F. Kennedy’s admonition to “ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country” ringing in his ears. He was not the only one inspired by Kennedy’s call. The words had a special meaning for the troops who volunteered early in the war: in her interviews with hundreds of Vietnam veterans, MacPherson heard many repeat that passage from Kennedy’s inaugural address. “Always they say it with a sense of emotion, as if it were a message meant for each alone, like the lyrics of a love song. It is, they say, the single most memorable sentence of their lives.”Footnote 14

In Caputo’s rehearsal of the passage, it not only describes his younger self’s belief in Kennedy’s call to action, it also symbolizes a capacity for belief that he and his fellow veterans took to Vietnam but lost in its jungles and paddies. Other symbols at the heart of America’s identity and sense of mission also crumbled: when Caputo, Webb, and other veteran authors mention John Wayne, they not only recall the Westerns and war films that informed their younger selves’ sense of duty and patriotism, they also signal that their experiences in Vietnam rendered obsolete Wayne’s mode of heroism. His was a brand of martial masculinity whose fatal emptiness the war exposed. Wayne’s name becomes a verb: in one war narrative after another, to “John Wayne” is to commit a foolish and often doomed act of valor as though one were acting in a Hollywood film.Footnote 15 Those who survive are wiser. The master trope of the majority of Vietnam veterans’ narratives, which describes the trajectory of both A Rumor of War and Fields of Fire, is irony, as their central characters move from naïveté to disillusionment.

In 1965, when he landed in Vietnam along with the first contingent of marines, Caputo and his fellow marines believe in their own service myths: “we believed in our own publicity – Asian guerrillas did not stand a chance against US marines – as we believed in all the myths created by that most articulate and elegant mythmaker, John Kennedy.” During a tour of duty in which “everything corroded,” including not just equipment but morals, Caputo becomes disenchanted with the war effort as a whole and discovers the capacity for cruelty and undiscriminating violence of which both he and his men are capable. He concludes that Kennedy is a “political witch doctor” whose “charms and spells” led young men like himself to war.Footnote 16

The surviving central character in Fields of Fire also has the webs of illusion lifted from his eyes, but his moral trajectory runs in the opposite direction from Caputo’s. A recruiting sergeant conned Will Goodrich into joining up by the promise that he can play his horn in the Marine Corps band. Harvard-educated, he is suspected by his fellow platoon members of being a Criminal Investigation Division plant. He wins the nickname “Senator” and questions the way the war is being fought; he turns in some of his fellow marines for killing two Vietnamese civilians as retribution for the capture and murder of two Americans. By the end of the novel, though, he has seen better men than himself sacrifice themselves for a cause in which they hardly believe, in large part out of their sense of loyalty to the Marine Corps and to their fellow “grunts.” Experience changes him. Having lost a leg in Vietnam, he returns to the Harvard campus where antiwar students invite him to speak at a rally.

The novel’s author, Webb, reserves his greatest contempt for the children of the elite who declaim their opinions based on their own myths and fabrications. Goodrich denounces the crowd of students: “How many of you are going to get hurt in Vietnam? I didn’t see any of you in Vietnam. I saw dudes, man. Dudes. And truck drivers and coal miners and farmers. I didn’t see you. Where were you? Flunking your draft physicals? What do you care if it ends? You won’t get hurt.” What, he asks, do any of them know of the war? Webb was an unreconstructed supporter of America’s war effort in Vietnam who was appointed to high positions in the Reagan administration and, as a Defense Department official, helped organize Reagan’s Central America military exercises.Footnote 17 His mouthpiece, Goodrich, impugns the right of anyone who was not there to express any political view about the war.

The contrast in the ideological content of the two works highlights their commonalities: the Sisyphean absurdity of long patrols through the South Vietnamese countryside; the indifference or hostility of much of the South Vietnamese population; the insensitivity of higher officers and other rear-echelon personnel to the plight of the troops in the field; the resentment by the troops of their government; and the convergence of the storyline on the primal scenes that lie at the heart of many Vietnam War narratives – instances of “fragging,” when American soldiers turn on one another with murderous violence, and atrocious crimes against Vietnamese civilians.

Both narratives end by explaining away atrocities. Having turned in a comrade for murder, Goodrich has a change of heart. He says,

You drop someone in hell and give him a gun and tell him to kill for some goddamned amorphous reason he can’t even articulate. Then suddenly he feels an emotion that makes utter sense and he has a gun in his hand and he’s seen dead people for months and the reasons are irrelevant anyway, so pow. And it’s utterly logical, because the emotion was right. That isn’t murder. It isn’t even atrocious. It’s just a sad fact of life.Footnote 18

Facing a court-martial, accused of ordering his troops to kill two civilians suspected of being National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) guerrillas, Caputo says that the “explanatory or extenuating circumstance” that helps explain his actions “was the war. … The thing we had done was a result of what the war had done to us.”Footnote 19 The war is the subject of the verb and the driver of events, the veteran the malleable creature who suffered and was subject to its drives. The history of the war shifts from the active to the passive voice. The war changes from what we did to what was done to us.

Both Caputo’s and Webb’s works convey a common complaint about the lack of understanding and sympathy in the military and society for those who fought the war – as Webb puts it, the “culture gap” that separated the warriors from those who stayed safely home. The elite in particular became targets of veteran resentment, because their eligibility for draft deferments and knowledge of how to work the system allowed them to avoid conscription or be disqualified from service if they were swept up in a draft call. According to Caputo, the resentment ran in both directions: the elites who engaged in policy debates in the United States “shared a suspicion, sometimes a contemptuousness,” of those who fought, “the children of the slums, of farmers, mechanics, and construction workers.”Footnote 20 Caputo is wrong, however, to distinguish between the working classes and participants in debates about the war: as Penny Lewis has shown, the working class was fully engaged in, and sometimes at the forefront of, antiwar organizing.Footnote 21 Accurate or not, Caputo’s comment sums up the barrier of antipathy and incomprehension that divided veterans from their civilian compatriots. It instantiates the predominant feeling tone of postwar discourse by veterans: a voicing of grievance and complaint, demanding attention and understanding.

From the late 1970s to the present, Vietnam veterans never stopped expressing resentment at having been ignored and silenced; one of their principal themes has been the charge that their voices have remained unheard. Caputo echoes Michel Foucault when he says that in the mid-1970s, as he was writing and rewriting his memoir, Vietnam as a subject for literature “was almost as taboo as explicit sex had been to the Victorians.” In the period when his book was published, though, a vast output of talk about Vietnam veterans began to proliferate. The structure of Caputo’s complaint follows that of Foucault’s “repressive hypothesis”: as Foucault argues, the Victorians, supposedly squeamish about sex as a taboo subject, never ceased talking about it, and discourses on sex multiplied in the very space where its suppression was effected.Footnote 22 Likewise, a vast mechanism for understanding Vietnam veterans’ predicaments, for ameliorating their distress and alienation, and for coming to terms with the historical experience they personified was established at the very moment that veterans complained they were being silenced and ignored, sometimes in the same breath.

Post-Traumatic Stress and “Healing” from the War

The network of discourses surrounding veterans’ distress thickened in 1980 when the American Psychiatric Association (APA) validated a new psychiatric label, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The third edition of the APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychological Disorders (DSM-III) identified PTSD as a condition characterized by recurrent painful, intrusive recollections or recurrent dreams or nightmares of a stress-inducing event; in extreme cases, sufferers experience dissociative states, popularly known as “flashbacks.” Other symptoms include diminished responsiveness to the external world (or “psychic numbing”), hyperalertness, an exaggerated startle response, sleep disturbances, and avoidance of activities or situations that might arouse recollections of the traumatic event. Recognition by the APA allowed the Veterans Administration (VA), the government-mandated system of support and medical treatment for veterans, to begin to diagnose them for a war-related condition and to compensate those who received the diagnosis. Previously, Vietnam veterans presenting with psychiatric symptoms were often diagnosed with conditions such as depression and psychosis, taking no account of their military service. In the 1980s, the government established a system of storefront Vietnam Veterans Outreach Centers (or “vet centers”) to offer services to veterans put off from visiting VA hospitals because of their poor reputation.Footnote 23

PTSD affected every subpopulation of veterans, and therefore indirectly influenced how the public thought about veterans, about the war that had damaged them, and about the nation’s obligations to them. The effects of PTSD were particularly marked, however, among African American veterans. Overrepresented on the front lines – and the casualty rolls – in the early years of the war, when they returned from Vietnam they faced the same disadvantages that other African Americans did: higher rates of unemployment and poverty, discrimination, and racism. They also dealt with additional burdens. When in the armed forces, African Americans who committed infractions against military discipline of comparable seriousness received much harsher punishments than did whites. The result was that African Americans had vastly higher rates of less-than-honorable discharges than did their white counterparts. “Bad paper” discharges deprived them of veterans’ benefits and introduced additional barriers to employment. On top of all this, African Americans had higher rates of PTSD than whites did, and the intensity and duration of their symptoms were, on average, greater.Footnote 24 Simply having served in Vietnam was stressful for African Americans, who faced racism both inside and outside the armed forces, and who were sometimes accused of having fought a “white man’s war.” The situation was even worse for Hispanic veterans, who suffered higher rates of PTSD than did whites or African Americans.Footnote 25 Whether or not the public were aware of the differences in the harmful consequences of the war among an ethnically diverse veteran population, the sense that the poor and disadvantaged continued to carry the burden of the war into their civilian lives contributed to the public’s growing sympathy for them.Footnote 26

The recognition of PTSD also gave the public a new way of registering concern and attending to the veterans’ perceived needs. In the 1970s, Vietnam veterans had appeared in media representations as malcontents. Lazy script writers for that decade’s cop shows, such as The Streets of San Francisco, Mannix, Kojak, and Cannon, used the “hair trigger” veteran as an all-purpose villain, whose criminality needed no more explanation than service in Vietnam. PTSD cast veterans suffering emotional distress in a more sympathetic light and placed a degree of responsibility on the public. According to the emerging psychiatric and sociological knowledge about veterans’ PTSD, an important factor that might mitigate or exacerbate veterans’ symptoms was their homecoming and their relations with their neighbors and fellow citizens. If veterans felt accepted by their civilian compatriots, their conditions were likely to be less severe and long-lasting; to the extent that they felt neglected and vilified, their symptoms would be worse. Thus, their fellow citizens began to feel a moral imperative to recognize the veterans in their midst – and, through them, to come to terms with the nation’s vexed memories of the war.Footnote 27

The principal vehicle through which Vietnam veterans led their fellow Americans into a new encounter with the history and consequences of the Vietnam War was the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Led by a former corporal in the US ground forces, Jan Scruggs, in 1979 a handful of veterans incorporated and filled the crucial officer positions in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF).Footnote 28 Their ethos was that the nation had been divided for political reasons during the Vietnam War, and their civilian compatriots had been too long divided from the veterans. By coming together in the recognition of the service and sacrifices of those who served and those who died in Vietnam, Americans could set aside their political differences and reconcile with one another. By embracing the Vietnam veterans, Americans could provide those veterans with comfort and “healing,” simultaneously overcoming the division between veterans and their fellow citizens and helping American society to recover from its war-induced “wounds.”

The VVMF decided that it was crucial to create a memorial that made no political statement about the war. Its leaders said that they wanted the nation to recognize and honor those who fought without honoring the war itself. They were following one of the truisms that had emerged from therapists who treated Vietnam veterans. The psychologist Charles Figley hoped that the country could have “two cognitive notions,” so that even those who were ashamed of the war could be proud of the veterans: the country needed “to separate the warrior from the war.” Although Scruggs, the president of the VVMF, liked to present himself as an ordinary “grunt” (or foot soldier), he was thoroughly immersed in the therapeutic discourses surrounding Vietnam veterans, having trained in psychology and adopted the goal of creating a memorial as a result of this training. The VVMF adopted “separating the warrior from the war” as one of its watchwords and slogans.Footnote 29

The VVMF also adopted a passage from Caputo’s memoir as a kind of manifesto. Grieving for his friend Walter Levy, who died trying to save a fellow marine, Caputo says that Levy embodied “the best that was in us.” His sacrifice, though, had been forgotten. There were no memorials to a war that his fellow citizens would rather forget. Officers of the VVMF arranged for a passage about Americans’ preference for “amnesia” to be read out at organizational events, and President Carter read it when signing the authorizing legislation for the memorial.Footnote 30 The memorial’s goal was to lead the nation away from this amnesia.

A professional jury chose the design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial: a pair of black granite walls inscribed with the names of American military personnel who had died as a result of their service in Vietnam. The names appeared in chronological order, according to when they died. Reflecting the ethnic diversity of the American population, they combined to produce what the designer, Maya Ying Lin, called an “epic poem.” Not everyone liked her design. In particular, rightwing critics disliked the granite’s black color, the absence of a prominent, centrally located flag, and the fact that the ground sloped toward the center of the memorial so that it gradually sank into the earth, rather than rising above it. Critics said that the memorial would be hidden away and buried, suggesting that the country was ashamed of the war and those who fought it. Webb had been a member of the memorial’s National Sponsorship Committee, but he resigned that position and encouraged others to do the same. He wrote a fierce criticism of the memorial, saying it would become a “wailing wall for future anti-draft and anti-nuclear demonstrations.”Footnote 31 Webb wanted a monument that would vindicate the cause for which Americans fought and died, not one that he thought was redolent of defeat.

The complaints by Webb and fellow critics led to the addition of a bronze statue of three infantrymen; Webb was one of the members of a panel that approved the sculpture by Frederick Hart, who had a long-standing relationship with the VVMF from before they held a design competition. A decade later, the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, another multifigure bronze sculpture, was added to satisfy the demands of female veterans who justifiably complained that Hart’s sculpture sidelined the presence of women in the American forces in Vietnam.Footnote 32 Because most of the uniformed women who served in the US forces were nurses, the Vietnam Women’s Memorial and other such sculptures reinforce the theme of healing that lay at the heart of commemorative efforts in Washington and around the country. The depicted scenes of nurses’ care and nurturance – and similar sculptures in which male soldiers ministered to their wounded buddies – showed the ameliorative language of healing in action.

Many sculptural Vietnam veterans memorials are multifigure statues, demonstrating a felt need to represent the demographic range of the American armed forces, with respect to race, ethnicity, and, sometimes, gender. But whereas female veterans were effective in mobilizing support for the addition of a women’s memorial to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, by and large ethnic minority veterans had little influence on the decision-making processes in the selection of memorial designs. Typical of other memorial efforts around the country, Webb, a white veteran, took credit for ensuring that the Hart statue included an African American figure.Footnote 33 In such works, ethnicity stands not as a marker of difference but as an emblem of the transcendent brotherhood of those who served together under arms.

Throughout the 1980s and beyond, memorials around the United States took on the same tasks of reconciling the United States with its veterans, and bringing together politically divided camps in a common, veteran-centric program of commemoration. Most of them bring together the two principal components of the national memorial in Washington, DC: walls inscribed with the names of America’s fallen troops, and bronze statuary. Irrespective of whether the memorial designs consist of the wall-and-statue formula, architectural or landscape designs, virtually all the groups that organized the commemorations rallied supporters with catchphrases borrowed from the VVMF: separate the warrior from the war; honor those who fought while avoiding political statements; help the country to heal. Giving the veterans an overdue welcome home became the rallying point that brought together former supporters and opponents of the war.Footnote 34

Therapists working with veterans had advocated a renewed encounter between veterans and the public. Arthur Egendorf, one of the first who had set up Vietnam veteran “rap groups” that allowed veterans to confront their experiences of the war, said that they could help their fellow citizens by working through and finding meaning in their war experiences. “American society,” he said, “ultimately gains from their efforts to derive significance from the confusion and pain still associated with that conflict.” Harry Wilmer, another therapist, said that the nightmares of combat veterans afflicted with PTSD were “symbolic of our national nightmare.” For the veterans and the nation to recover, veterans had to overcome their reluctance to talk about the war so that Americans could “face the nightmare horror – hear it, see it, know it.”Footnote 35

Oral Histories and the Conventional Vietnam Veteran Image

Oral narratives by those who fought met the call for a veteran-voiced means through which the public could encounter the Vietnam War.Footnote 36 The oral history collections that achieved bestseller status in the 1980s offered, according to their promotional material, the “gut truth” of the war. Marketed as the unbiased accounts of ordinary veterans, they flew under the ideological radar, using personal experience as the warrant of their rhetorical authority. They allowed veterans’ voices to be heard, and they allowed the public vicariously to work through the most troubling moral quandaries left over from the war at the level of episodic personal stories, allowing a sympathetic reader to walk in the shoes of the narrators and see the war through their eyes.

The narratives deal with content familiar to readers of veteran authors’ novels and memoirs: the heat and discomfort of the field, the bile and gore of combat, the moral qualms with which the troops struggled, and the memories that haunted them years later. The oral narratives derive their meaning above all, though, from the frame in which the narrator and reader meet. Here are the stories of ordinary veterans, the grunts who, by definition, are not strategists, historians, politicians, or authors. Here is the story of the war as witnessed by those who were there, who did not plan the war but went where they were sent. And here the public will listen to the unvarnished truths that the witnesses and participants, above all, can provide. By their nature, the oral narratives did not require one to engage with political or strategic judgments in which decisions by the nation’s political leaders – and therefore, in a democracy, the nation itself – would have been implicated.Footnote 37

As Alessandro Portelli has argued, though, no informant in a culture permeated by written and electronic media is innocent of the ideological effects of these forms of communication. Vietnam War storytelling is a particularly salient example of this phenomenon, since veterans’ stories are thoroughly imbued with ideologically inflected understandings of the war. Decades ago, Michael Frisch criticized the reliance of the producers of the PBS series Vietnam: A Television History, broadcast in 1983, on the recorded remembrances of those who “were there,” a move that seemed to grant “experience” sole interpretive authority. Yet it turns out that, unbeknownst to the readers, the raw experience that the oral narrative collections offered could not always be taken at face value. Some of the stories were heavily edited by the authors of the volumes in which they appeared.Footnote 38 Some were highly rehearsed and refined, part of a repertoire of stories recycled by numerous narrators.Footnote 39

Among the most skillful purveyors of these pieces of folklore were fake Vietnam veterans, or “wannabes,” who exaggerated and falsified their experiences in Vietnam. Some individuals even claimed to be Vietnam veterans although they had not served in Vietnam at all. Such wannabes tended to explain the course of their lives as the result of their experiences in Vietnam, and their narratives often focused on “hot-button” subjects, including traumatogenic horrors and atrocity tales, which help to provide rationalizations for unfulfilled and unsuccessful postservice careers. For example, in Wallace Terry’s Bloods, the Vietnam veteran Harold Bryant, who falsified the basic facts about his tour of duty, delivers the standard litany of horror stories: burning villages, mutilating enemy corpses, throwing captives out of helicopters, raping women.Footnote 40 Bryant knew a good story when he heard one: he told a story of ingeniously tying a rope around the waist of a soldier who had the misfortune of stepping on the plunger of a “Bouncing Betty” antipersonnel mine. He and his friends yank the soldier away and the mine springs up and explodes harmlessly.

This story is part of the standard repertoire of lore surrounding Vietnam War service that numerous (genuine and fake) veterans have told and retold.Footnote 41 I myself once heard the same story from a homeless man who used to haunt the environs of the California Vietnam Veterans Memorial. He even showed me a scar on his leg supposedly made by a piece of shrapnel from the mine. Narrators highly attuned to the interests and attention of their listeners and not restricted by the mere happenstance of actual events could home in on tales that aroused their listeners’ pity and horror; and they could refine the stories through multiple retellings to maximize the stories’ capacity to rivet an audience.

Despite its oddness, the phenomenon of the fake veteran is not to be lightly dismissed. Wannabes’ stories are selected because they convey moral and psychological truths about the Vietnam War – what the author Tim O’Brien describes as the “story truth” as opposed to the “happening truth.” Because of the preexisting negative storyline about the Vietnam War, many of the stories involve grotesque and morally questionable acts. As the military sociologist Charles Moskos said, atrocity stories from Vietnam were the functional equivalent of stories of heroism out of World War II. They gave the stories a meaning that resonated with the people back home. But atrocity stories do not exhaust the morally meaningful parables in oral histories. For example, Bloods contains contrasting stories about race. They reveal the racism that the African American troops encountered on bases in Vietnam, but such events act as a foil for contrasting stories in which Black and white troops in combat forge bonds of brotherhood overcoming racial differences.Footnote 42 These stories are like biblical parables, condensing in them resonant meanings: the story of America’s struggles not just in foreign wars, but also the course of its struggles with the history of racial injustice. If you want to see a catalog of received knowledge and common sense about the war, and if you want to see the United States talk to itself about its past, present, and future, then find that life world in its purest form in the words of the practiced storytellers, including “veterans” who were never in Vietnam.

Understandably, those who really did risk their lives by serving in Vietnam resented the phonies for assuming the role of spokespeople. The wish to contest “wannabe” stories resulted in determined efforts to expose the fakes in oral history collections and elsewhere – which in turn led to the passage of a law prohibiting unjustified claims of having been awarded military decorations, the “Stolen Valor Act.”Footnote 43 The significance of the “wannabe” phenomenon may lie in its revelation that Vietnam veteran identity had assumed a stereotypic character that fake veterans could imitate; and that the Vietnam War story had taken on conventional forms, such that skilled, nonveteran practitioners could mimic it and spin it into elaborations and variations.

In the readiness of filmmakers, however, to treat veterans as founts of authentic knowledge and judgment, little has changed. Three decades after the broadcast of its first television series about the war, the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) screened another major documentary about the war, The Vietnam War, coproduced by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.Footnote 44 Once again, the picture is filled with veterans talking about what they saw and did in Vietnam. Deliberately eschewing on-screen historians for commentary, the filmmakers depend on veteran narrators to provide historical interpretations of US strategy.

The preference for the on-screen commentary of veterans, rather than nonveteran scholars and experts, leads to some incongruities. A professional historian offers his distinctive and controversial interpretation of the course of the war, his presence on screen justified because he is a Vietnam veteran; conversely, a nonhistorian veteran is licensed to pronounce his judgment of the inner workings of the Johnson administration. The historian Lewis Sorley, speaking not as a scholarly researcher but as a veteran, his on-screen credential the designation “Army” below his name, offers a questionable judgment about the superiority of US strategy after 1969 – ignoring the fact that his service in Vietnam considerably preceded the period about which he pronounces his views to the camera. Karl Marlantes, a marine lieutenant in Vietnam, is licensed to express a judgment about US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s actions in keeping his doubts about the nation’s war policy private, which McNamara revealed in a memoir years after the war.Footnote 45 The filmmakers authorize both to provide military–historical commentaries on the principle that only Vietnam veterans are entitled to offer such judgments, even though the particular topics cited lie outside the scope of their personal experience as eyewitnesses in Vietnam.

Like Caputo and Webb, Marlantes was a platoon commander in Vietnam. In his novel Matterhorn, his writing is powerfully vivid. As his predecessor authors do, he conveys the visceral intensity of combat; he captures the malaise, anxiety, and emptiness of the life of a leader, under pressure from ignorant and career-driven higher officers, and worried for the men whose lives depend on his decisions. Like other veteran writers, Marlantes measures the gap in comprehension between those who were there and those who stayed home. As one marine says to Mellas, the central character: “You think someone’s going to understand how you feel about being in the bush? I mean even if they’re like you in every way, you really think they’re going to understand what it’s like out here?”Footnote 46 In Marlantes’ writing, the physical degradation that the troops suffered descends to its nadir: he returns again and again to the oozing mixture of blood, pus, and jungle rot through which the foot soldiers squelch, their ulcerated flesh raw with blisters and sores. Yet the moral universe he pictures has not moved far from Caputo’s and Webb’s: the dramatic center of the narrative concerns the troops’ wish to frag the superiors who care nothing for the lives of those they command. The predominant feeling tone of veterans’ experience remains a plaintive mixture of rage and melancholy as Marlantes documents the fruitless and unrewarded sacrifices the troops make, despite their unworthy commanders and an uncaring nation.

Although the producers of the PBS documentary series rely on Marlantes to pronounce on the wisdom of US military policy, Marlantes never claimed to be a military theorist or strategic thinker – albeit he is an astute judge of the impact of the Vietnam War on American society. Limited as a guide to policymaking, Marlantes’ voice – and those of many of the other veterans selected for inclusion by Burns and Novick – is a fascinating index of the way that received truths about the Vietnam War have gathered conviction and authority. If one wants further to understand how a nation comes to terms with the past and settles on commonsense understandings of it, one might study the collective wisdom that the veteran narrators in The Vietnam War recite.

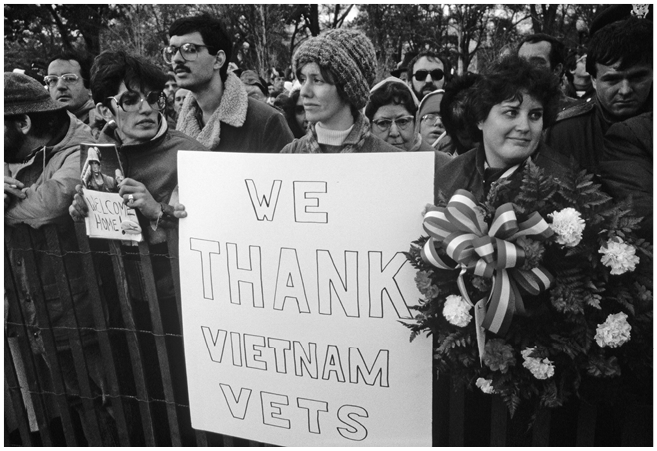

Figure 24.1 The crowd lining the route of the dedication parade for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, expressing the “welcome home” the memorial was intended to symbolize (November 1982).

The Burns/Novick documentary series begins with Marlantes repeating the familiar complaint about the silencing of Vietnam veterans. “For years nobody talked about Vietnam,” he says. He and another former marine were friends for years before either of them told the other that they had served in Vietnam. Marlantes repeats another piece of folklore, widely believed but convincingly discredited, that he and other veterans were spat on by antiwar protesters when they came back from Vietnam. Although it is impossible now to go back in time and verify whether such events occurred, the scholar Jerry Lembcke has shown that, with one exception, there were no contemporaneous accounts of such mistreatment of veterans when they returned from the war. The tales of having been spat on began to circulate years afterwards, reflecting the psychological truths about the strained relations between veterans and their compatriots, irrespective of how many spitting incidents actually occurred.Footnote 47

Reconciliation … and Unfinished Business

Reconciliation between those who fought the war and their compatriots who did not serve in Vietnam has been uneven and incomplete, and the nation’s coming to terms with the aftermath of the Vietnam War has likewise followed a twisting path. Examples of the unfinished business that remained from the war years include the relations between the United States and Vietnam and the health problems of those exposed to chemical defoliants used by the United States’ forces in Vietnam.

The moves to normalize relations between the United States and Vietnam began with a “road map” issued by the administration of President George H. W. Bush and accelerated during the administration of his successor, Bill Clinton. But a major obstacle to the restoration of diplomatic relations was the belief that American POWs, or those listed as missing in action (MIA), were still held captive in Southeast Asia. A conspiracy theory underlay this belief: according to one version, when Richard Nixon negotiated a peace agreement with North Vietnam in 1973, he agreed to pay a massive sum of money to America’s former communist enemy, which the Vietnamese government regarded as “reparations.” Mistrusting Nixon, the North Vietnamese supposedly kept a number of American military captives to guarantee that the payment would be made. Conspiracy theorists believe that when Nixon resigned from the presidency, the deal fell through and the North Vietnamese, unwilling to admit that they still held American prisoners, secretly held on to them. President Reagan had played into and exploited this belief when his administration seemed to give it credence. He himself undertook to write “no final chapter” until any Americans being held against their will came home.Footnote 48

H. Bruce Franklin reports that in a poll taken in 1991, over two-thirds of the respondents believed that there were still live POWs in Southeast Asia. It is understandable that family members harbored this irrational belief, because they did not wish to accept that those listed as MIA had died. They formed the core of a group who asserted that the war was not over “until the last man comes home.”Footnote 49 This belief served as the basis for the plot situations of “revenge movies” such as Uncommon Valor, Rambo: First Blood, Part II, and Missing in Action in which Americans returned to Southeast Asia on missions to rescue their brothers-in-arms who remain in communist hands.Footnote 50 In Rambo, the eponymous hero (Sylvester Stallone) asks, “Do we get to win this time?” Rambo succeeds in finding American captives, but it turns out that the US government operatives planning his mission intended it to fail in order to discredit the idea that there were live prisoners left in Indochina and thereby to put the issue to bed. An unscrupulous American intelligence operative tries to sabotage the mission, but Rambo succeeds in returning the captives to friendly territory. The story has multiple attractions for those who wish to take refuge from historical reality: Rambo vindicates the martial prowess of the American fighting man, refights the war in microcosm, and proves that victory was thwarted the last time only because of a lack of will to win.

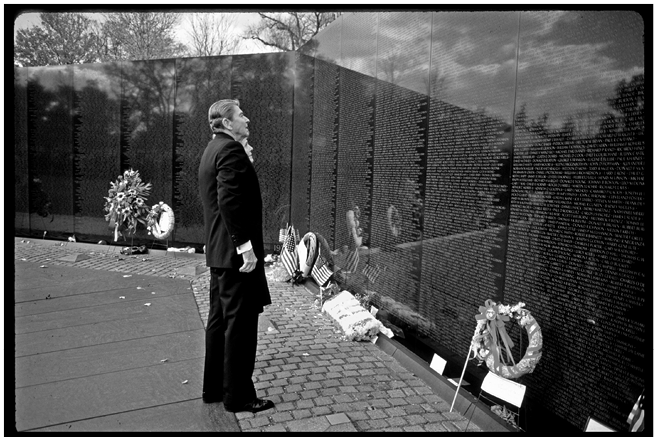

Figure 24.2 President Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan walk along the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Veterans Day, 1988. Observing a popular custom, they leave a note there – addressed to their “young friends” whose names are inscribed on the wall.

The POW/MIA issue was nurtured by rightwing politicians and unscrupulous opportunists as a means of mobilizing resentment against America’s former enemy, as though by keeping the war alive the nation could indefinitely defer an admission of defeat. Disgruntled veterans’ grievances slowed the normalization of relations between the former belligerents, the United States and Vietnam. These old resentments were exploited for political purposes: the POW/MIA issue was the cornerstone of the third-party presidential candidacy of H. Ross Perot in 1992.

Clinton ended the trade embargo against Vietnam in February 1994 and began low-level diplomatic contacts. Diplomatic relations between the United States and Vietnam were normalized in 1995, with the opening of a US Embassy in Hanoi in August of that year. Senator John Kerry, a Vietnam veteran and former antiwar activist, said that normalizing diplomatic relations with Vietnam would “close the book on the pain and anguish of the war and heal the wounds of the nation and help us to put it behind us once and for all.” In 2001, the two countries agreed on a bilateral trade deal. By 2016, when US President Barack Obama visited Vietnam to celebrate the Comprehensive Partnership between the two countries, Vietnam had become the United States’ fastest-growing trading partner. In January 2018, an official visit to Vietnam by Secretary of Defense James Mattis showed how far the relationship between the former adversaries had developed. It occasioned an affirmation of the “enhance[d] defense cooperation” between the United States and Vietnam, with a focus on maritime security, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and peacekeeping operations. In 2019, US President Donald Trump held up Vietnam as an economic success story that communist North Korea would do well to emulate.Footnote 51

As relations between the countries warmed, the POW/MIA issue faded from view. However, a lasting legacy of this episode is the congressional mandate since 1990 to fly the POW/MIA flag at military installations, memorials, and government buildings. The hard fact, though, is that no live prisoners have returned from Southeast Asia, and the search for MIAs gave way to the recovery, with Vietnamese assistance, of the remains of US casualties. The leading organization representing Vietnam veterans, Vietnam Veterans of America, now demands the fullest possible accounting of those still listed as MIA and the repatriation of the remains of Americans, rather than campaigning for the return of live POW/MIAs.

As relations between the United States and Vietnam became closer, many veterans made return trips to the battlefields where they once fought. They often report that their former enemies show them no animosity. Indeed, many American and Vietnamese veterans of the war have expressed mutual respect through these encounters. American organizations, some led by Vietnam veterans, have undertaken humanitarian projects in Vietnam. The visits also perform important functions in coming to terms with the legacy of the war and bringing about reconciliation between the former enemies. The Fund for Reconciliation and Development undertook a trip to Sơn Mỹ (Mỹ Lai) in March 2018 to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the massacre.Footnote 52

There is still much unfinished business left over from the war. Veterans claimed that their health was damaged by exposure to deadly contaminants found in the herbicide Agent Orange that US aircraft had sprayed widely in Vietnam in order to deny the enemy ground cover. Because the veterans were prevented by law from suing the US government, they engaged in a major class-action lawsuit to make a claim for compensation against the chemical companies that had manufactured the defoliant; others renewed the lawsuit after a settlement was reached in the first case. In a parallel move, Vietnam veterans demanded treatment through the government-provided health-care system for conditions they believed resulted from their exposure to the chemical defoliant. Initially resistant to recognizing these health effects, the government ultimately recognized a number of conditions as presumptively arising from exposure to Agent Orange.Footnote 53

The ongoing ill-health resulting from Agent Orange exposure meant that, for some veterans, the war was not over on their return to the United States. Underlining this point, Agent Orange affected male fertility and inflicted genetic damage on the children of Vietnam veterans. Agent Orange was one of the issues that added to the sense of grievance and resentment many Vietnam veterans carried, a sense of felt injustice remaining the predominant theme of veteran–governmental and veteran–societal relations, running the gamut of complaints from the POW/MIA myth to the very real problems of PTSD and chemical poisoning. Because of the involvement of chemical companies in the lawsuit, the complaints in this case also carried an anticorporate shading. The issue also affected relations between Vietnam and the United States, given that much of Vietnam suffered contamination, and many inhabitants of Vietnam were exposed to it for life rather than for the relatively brief period of an American soldier’s tour of duty. While tens of thousands of American veterans are believed to have been exposed to Agent Orange, millions of Vietnamese have been so exposed.Footnote 54 This situation has spurred American organizations to demand redress for Vietnamese people whose land was poisoned and who continue to suffer the ill-effects of exposure to toxins decades after the war ended for others.

Conclusion

To contemplate the harm done to Vietnam by American forces reminds us of another unresolved matter: the suspicion on the part of a vast number of Americans that deliberate and indiscriminate violence by American troops against Vietnamese civilians was commonplace during the war. In the first decade of the new millennium, the work of investigative journalists uncovered long-suppressed knowledge about the incidence of American-perpetrated atrocities during the Vietnam War. One study concentrated on the actions of a small unit, the “Tiger Force,” whose crimes had been investigated during the war years, although the results of the investigation were buried until reporters from the Toledo Blade dug into the matter; another study looked at the broader findings of the war-era Vietnam War Crimes Working Group. The government’s years-long hiding of these findings tended to reinforce the view that unreported atrocities had taken place in Vietnam and been covered up, and thus seemed to bear out the wartime charge by Vietnam Veterans Against the War that the indiscriminate or deliberate killing of civilians was “standard operating procedure” in Vietnam. This claim remains highly contested by veterans who try to reject the stigma of wrongdoing arising from the war. The reports of war crimes can be dismissed as anecdotal and hence unrepresentative, but the same applies to the reports by blameless veterans that no crimes took place in their units. The fact that crimes took place in one unit does not prove that they took place in every unit; by the same token, one cannot generalize from the absence of crimes in any particular unit. The association between the Vietnam War and American-perpetrated atrocities will likely never be dissipated, understandably leading to a reflex of shame and aversion that Reagan was unable to exorcize, no matter how much he insisted that the war was a “noble cause.”Footnote 55

Or will these feelings one day become so amorphous, detached from factual knowledge, that atrocities will cease to sting the conscience, and the war itself will cease to horrify and to warn? The Gallup Organization has periodically asked national samples of the public whether they believe that the Vietnam War was a mistake. As we saw at the start of this chapter, over the decades a steady two-thirds to three-quarters of the public responded that they believed the war was a mistake. Although that finding was broadly borne out by the poll taken in 2013, there was one exception. While all the other age cohorts agreed that the Vietnam War was a mistake, one group – those aged 18 to 29 – disagreed, albeit by a small margin. The Gallup researchers reported, “Young adults are the only age group in which a majority says the Vietnam War was not a mistake (51 percent) – perhaps because they have no personal memory of the conflict.”Footnote 56 It may be, therefore, that we are beginning to witness a generational shift in the divided memories of the war. Although the nation may never have truly “healed” from the war, as the planners of Vietnam veterans’ memorials hoped, it may finally be forgetting. As the memory of the war descends down the generations, our shared culture has become the repository for the commonsense knowledge about the war. That common sense is not fixed in stone: it is as malleable as the minds of the population whose thoughts it occupies. We all become the custodians of that knowledge, and our thoughts and feelings will continue to mold the contours of the Vietnam War in American culture.