On January 31, 2020, the United Kingdom (UK) left the European Union (EU). In the UK, one of the main arguments presented by Brexit advocates to justify the withdrawal from the EU was the chance to establish new political and economic relations with international partners, outside of the EU framework. Speaking in Greenwich four days after Brexit, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson touted not only the potential of free trade with the United States (US) but also the opportunity of reinvigorating relations with Commonwealth states. He especially singled out Canada, Australia and New Zealand—three “old friends and partners” on whom, as he put it, “we deliberately turned our backs in the early 1970s” when the UK decided to become a part of the European Common Market (Johnson, Reference Johnson2020).

The idea of leveraging Brexit to strengthen connections between Anglosphere partners is a popular notion in Brexit circles (Bell and Vucetic, Reference Bell and Vucetic2019). For Canadian foreign policy, it presents a conundrum. Canada had indeed been opposed to the UK's initial application for membership in the European Communities, the EU's predecessor institutions, because it put an end to Commonwealth trade preferences (Mahant, Reference Mahant1981). However, since the early 1970s, Canada has built strong economic and political relations with the European Communities and later the EU, solidified in part by the fact that the UK was a member state (Potter, Reference Potter1999; Bendiek et al., Reference Bendiek, Geogios, Nock, Schenuit and von Daniels2018). In 2016, Canada and the EU signed the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA), which cemented this privileged relationship. In the Brexit referendum that same year, the Canadian government, like all the UK's major international partners, expressed a preference for the “Remain” side.

While Brexit was not an aspiration of Canadian foreign policy, it forces Canada to reconfigure its transatlantic relationships. This reconfiguration has both a policy and an identity dimension. With respect to policy, the extent of adaptation required in specific policy fields depends on how comprehensively they were previously structured by EU frameworks. In the areas of trade and investment, where CETA lays down an authoritative rule book—which continues to be applied to the UK on a transitional basis—pressures for adaptation are the most immediate. The principal challenge here is the negotiation of a new Canada-UK trade agreement (Hurrelmann et al., Reference Hurrelmann, Atikcan, Chalmers and Viju-Miljusevic2019). Political and security relations, which are conducted through a greater variety of institutional structures, will adapt more gradually. For instance, Canada will need to decide how intensively it wishes to cooperate with the EU's Common Security and Defence Policy, which some authors expect to become more independent from NATO (Zyla, Reference Zyla2020).

The policy challenges of Brexit might prove to be less fundamental, however, than the questions that it raises about Canada's identity as a player in the transatlantic relationship and in international politics more broadly (Adler-Nissen et al., Reference Adler-Nissen, Galpin and Rosamond2017). This identity has, for the past half century, been shaped by the constructive tension between three competing, but not mutually exclusive, conceptions: Europeanism, internationalism and continentalism (Mérand and Vandemoortele, Reference Mérand and Vandemoortele2011). Canada's relationship with the EU could, as long as the UK was a member, be embraced by all three of them: for Europeanism, it represented an updated framework for conducting relations with traditional transatlantic allies, with the added benefit of not forcing a choice between Anglosphere (Vucetic, Reference Vucetic2011) and Francosphere loyalties (Massie, Reference Massie2013); for internationalism, European integration was an embodiment of what could be achieved through multilateral cooperation; and while extreme versions of continentalism saw little benefit in focusing on an international partner other than the United States (US), moderate interpretations did not object to complementing continental relations with connections to the EU, which, after all, was a reliable US ally. Notwithstanding occasional tensions in the relationship (Croci and Tossutti, Reference Croci and Tossutti2007; Dolata-Kreutzkamp, Reference Dolata-Kreutzkamp2010), the desirability of a close alignment with the EU was hence an area of consensus between different views of Canadian foreign policy, which guided successive Canadian governments regardless of partisan affiliations.

The UK's withdrawal from the EU threatens to upset this consensus. This potential disruption is evident in how representatives of Canada's largest political parties—Liberals and Conservatives—have responded to Brexit (Hurrelmann, Reference Hurrelmann, Chaban, Niemann and Speyer2020: 123–26). Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has cast Brexit in a negative light, labelling it “the most divisive, destructive debate to happen in the UK for an awfully long time” (House of Commons, 2019) and drawing explicit parallels to the election of Donald Trump in the US (Kelly and McGee, Reference Kelly and McGee2017). By contrast, he has consistently praised Canada's “historic partnership” with the EU, which he described as a multilateralist ally (Trudeau, Reference Trudeau2017). On the Conservative side of the political spectrum, Brexit has triggered the opposite sentiment. Former party leader Andrew Scheer was an early advocate of Brexit, which he claimed was necessary to protect “British political traditions” from “the dictates of EU bureaucrats” (Scheer, Reference Scheer2016). Since the referendum, leading Conservatives have called for aligning Canada more closely with the UK. The Conservative policy convention in August 2018 passed a motion embracing a so-called CANZUK (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, UK) agreement, encompassing free trade, visa-free mobility and security coordination (Bell and Vucetic, Reference Bell and Vucetic2019: 372–73). CANZUK was also a signature foreign policy proposal by Scheer's successor as party leader, Erin O'Toole, during the 2020 leadership race (Moss, Reference Moss2020). By contrast, both have been all but silent on Canada-EU relations.

These party discourses raise the possibility that, as an effect of Brexit, a new fault line emerges in debates about Canada's identity as an international actor, which pits alignment with what we can call the Eurosphere against conceptions of Canada as part of the Anglosphere. Whether this fault line will become politically consequential will depend, however, on whether the interpretations of Brexit advanced by the Liberal and Conservative leaders resonate in the population. This article examines Canadian public opinion on Brexit and its impact on the future of transatlantic relations. It is based on an original survey, conducted in September 2019. We present our argument in two steps. The first section develops a conceptual framework for analyzing perceptions of Brexit and the extent to which they are influenced by factors such as foreign policy values/affinities and partisan affiliations. The second section presents our empirical findings. Our study demonstrates a strong correspondence between positions expressed in party discourse and preferences in the population. These findings suggest that the conflict between Eurosphere and Anglosphere loyalties could indeed become increasingly salient in Canadian foreign policy debates post-Brexit.

Conceptual and Methodological Considerations

This study is interested both in mapping Canadian foreign policy attitudes about Brexit and in understanding the factors that influence them. It builds on the insights of previous public opinion research which has demonstrated that Canadians hold coherent and meaningful opinions about foreign policy priorities as well as about specific international issues (Berdahl and Raney, Reference Berdahl and Raney2010; Gravelle et al., Reference Gravelle, Scotto, Reifler and Clarke2014; Paris, Reference Paris2014). Contrary to the assumptions of the so-called Almond-Lippman consensus of the 1950s and 1960s, people's views on foreign affairs are, in other words, more than just volatile, incoherent and politically irrelevant “non-attitudes” (Holsti, Reference Holsti1992). Public opinion on foreign policy might not determine who governs and how they do so, but it does constrain governments in their foreign policy decision making and influences how governments “sell” foreign policy decisions (Aldrich et al., Reference Aldrich, Gelpi, Feaver, Reifler and Sharp2006; Soroka, Reference Soroka2003; Berdahl and Raney, Reference Berdahl and Raney2010; Paris, Reference Paris2014). At the same time, it is clear that we can only fully understand the policy significance of Canadian public opinion on Brexit if we also gain insights into the factors that shape it.

Determinants of foreign policy opinions

Three groups of factors have been highlighted in previous studies as determinants of foreign policy opinions. The first are the values and affinities with which people approach foreign policy. In a seminal American study, Hurwitz and Peffley (Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1987) have demonstrated the importance of citizens’ foreign policy “postures”—normative belief systems about international affairs, which are embedded in fundamental values. Hurwitz and Peffley (Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1990) also emphasize that perceptions of other countries influence how people view foreign relations. Their insights are reflected in a broad American and comparative literature that discusses foreign policy belief systems such as isolationism and militant or cooperative internationalism (Holsti and Rosenau, Reference Holsti and Rosenau1990; Wittkopf, Reference Wittkopf1990; Rathbun et al., Reference Rathbun, Kertzer, Reifler, Goren and Scotto2016; Gravelle et al., Reference Gravelle, Reifler and Scotto2017), as well as trust of other nations (Brewer, Reference Brewer2004), as determinants of foreign policy opinions.

There are strong reasons to expect that foreign policy values and affinities also shape Canadian public opinion on Brexit. One factor whose influence has been emphasized repeatedly in Canadian studies is internationalist values (Munton and Keating, Reference Munton and Keating2001; Berdahl and Raney, Reference Berdahl and Raney2010; Gravelle et al., Reference Gravelle, Scotto, Reifler and Clarke2014; Paris, Reference Paris2014; McLauchlin, Reference McLauchlin2017). In the context of Brexit, such values might make people skeptical of Brexit, as it entails leaving a multilateralist project. There is also evidence that affinities toward other countries shape how Canadians think about foreign policy. In a recent survey experiment, McLauchlin (Reference McLauchlin2017) points to the influence of a “partnership logic” that sees military operations led by European allies enjoying more support than those conducted with the US. It is plausible to expect that such affinities, especially attachments to Europe and/or the UK, influence people's response to Brexit—for instance, whether they evaluate it as democratic or chauvinistic, liberating or (self-)destructive.

A second important determinant of foreign policy opinions is partisanship. In the light of the post-Brexit discourses by Canadian party leaders, this factor is of particular interest to our study. In Canada, partisan differences in foreign policy opinions emerged most clearly in the late 1980s over the issue of free trade with the US, which dominated the 1988 federal election campaign (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Blais, Brady and Crête1992: 155). More recently, studies have found differences between Conservative partisans and supporters of other parties, especially on military and defence issues (Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Bastedo and Hove2009; Fitzsimmons et al., Reference Fitzsimmons, Craigie and Bodet2014; Gravelle et al., Reference Gravelle, Scotto, Reifler and Clarke2014). It is less obvious why these partisan differences exist. They may represent distinctive underlying political orientations and ideologies that lead citizens to support different political parties (Gravelle, Reference Gravelle2014; Fitzsimmons et al., Reference Fitzsimmons, Craigie and Bodet2014)—in the case of Brexit, for instance, convictions on the importance of British political traditions or the benefits of multilateral cooperation. It is also possible, however, that partisan differences emerge simply because of citizens’ lack of engagement with, and awareness of, international affairs. People relatively uninformed about global matters may simply take their cues from political parties, treating their positions as an information shortcut to the appropriate issue stance (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Shively, Reference Shively1979; Berinsky, Reference Berinsky2007).

Such partisan cue-taking can happen in different ways. The first involves taking direct policy cues from party elites. Partisans observe elite positions on Brexit and adopt them as their own. The second works through partisanship as “a perceptual screen through which the individual tends to see what is favorable to [their] party orientation” (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960: 133). Even in the absence of explicit elite cues about what position their supporters ought to take, partisans have stores of contextual information to draw upon in order to form opinions about novel political issues, and this information is shaped by their partisan predispositions (Bartels, Reference Bartels2002; Matthews, Reference Matthews, Bittner and Koop2013). There is good reason to think partisans could fall back on what they already know about their parties to form opinions about Brexit. For example, under the Conservative party's first leader, Stephen Harper, the party's rhetoric and behaviour toward a number of international and multilateral institutions, including the United Nations and the Commonwealth, demonstrated a clear and consistent aversion to those institutions (Paris, Reference Paris2014: 280). It is reasonable to suppose that Conservative partisans’ attitudes toward the EU are influenced by this kind of world view. Moreover, there is a growing partisan divide in Canada at both the mass (Kevins and Soroka, Reference Kevins and Soroka2018) and elite levels (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015: 143–74); elites from different parties and their supporters have taken distinctive positions on an increasing number of issues. At times, citizens might shift their party loyalties to suit their political positions, but at other times, they might change their opinions on some issues to more closely align with those of their co-partisans. Attitudes about Brexit and the future of Canada's transatlantic relationships might be influenced by the same partisan sorting that is characteristic of many other issues in Canadian politics. These explanations would imply that partisans’ views on Brexit and the post-Brexit future are likely to remain stable and also consistent with the positions taken by the parties they support. If, on the other hand, partisan differences are mainly due to heuristic elite cue-taking, the implications would be different: if partisans with very little knowledge about Brexit are exposed to more information and conflicting messages about the issue, they might be susceptible to changing their views (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992).

A third group of factors that has been shown to influence public opinion on international matters are issue-related attitudes that matter to the foreign policy question at hand. The influence of such factors has been demonstrated in research on the Brexit referendum in the UK. Hobolt (Reference Hobolt2016) and Clarke et al. (2017: 153–70) demonstrate that people's vote choice in the referendum not only depended on their values/affinities and partisan affiliations but also, unsurprisingly, reflected how they assessed specific effects of British EU membership—for instance, on trade and migration. In the Canadian context, issue-related attitudes of a comparable nature may be primed by Brexit. One example is views of referendums, an issue about which many Canadians have developed opinions in the context of contentious votes in Quebec and elsewhere (Anderson and Goodyear-Grant, Reference Anderson and Goodyear-Grant2005).

Variables and hypotheses

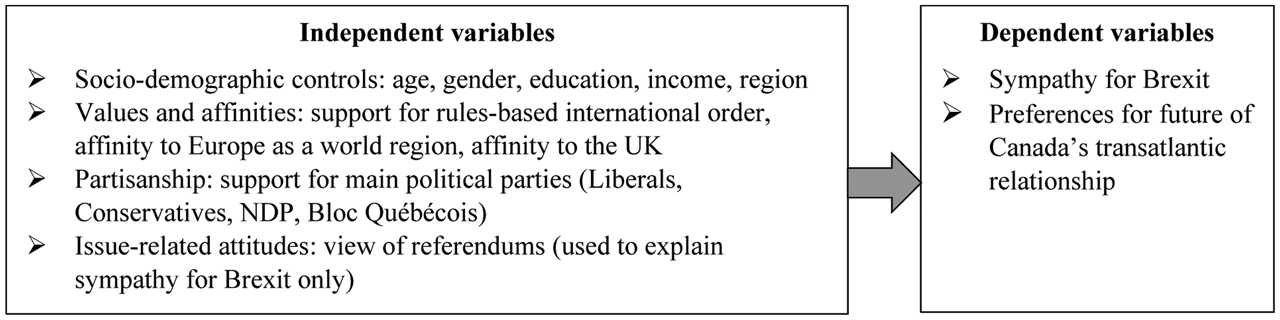

These considerations inform the analytical framework developed for this study (Figure 1). It focuses on two dependent variables, which are discussed in subsequent stages of our analysis. The first examines Canadians’ sympathy for Brexit. This measure tracks whether people have a negative or a positive perception of the UK's decision to leave the EU. The second dependent variable examines preferences for the future of how Canada governs its transatlantic relations. This measure is based on a series of questions in which respondents were asked whether, in a number of policy fields, Canada should prioritize relations with the EU or with the UK after Brexit. The two dependent variables represent two aspects of the Eurosphere and Anglosphere perspectives discussed above—one retrospective, the other prospective—and allow us to examine whether both are influenced by the same explanatory factors.

Figure 1 Analytical Framework

The dependent variables are regressedFootnote 1 on four sets of independent variables in a bloc-recursive model. This approach was developed by Miller and Shanks (Reference Miller and Merrill Shanks1996) building on the insights of Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960) and has been adapted to model vote choice in Canadian elections (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil, Nadeau and Nevitte2002; Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Blais, Everitt, Fournier and Nevitte2012). It assumes a causal sequence, in which variables at earlier stages in the sequence influence those at later stages (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Blais, Everitt, Fournier and Nevitte2012: 9). We estimate four models in a step-wise manner; at each step, we assess the impact of the newly added variables, controlling for more causally distant factors. This strategy recognizes that although the causal sequence will not be exactly the same for all individuals, by using this approach we can observe the average total effects of the independent variables (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Blais, Everitt, Fournier and Nevitte2012: 9; see also Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2016: 1266).

We begin with a base model that includes only socio-demographic factors (Model 1). In this context, we examine age, gender, education and income.Footnote 2 These factors have been highlighted in theories that explain support for populist political positions, including Brexit (Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019); empirically they have been shown to correlate with Brexit support in the UK (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2016; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley2017: 153–70). In addition, we include the Canadian region in which respondents reside: a factor that has been shown to matter, for instance, in differences between Quebec and the rest of Canada (Boucher and Massie, Reference Boucher and Massie2014). We include these variables primarily as controls, given that they tend to be associated with other proposed determinants in our model, especially partisanship: gender, income, age and education, for example, are consistently linked to party support (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Blais, Everitt, Fournier and Nevitte2012; Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Cutler, Soroka, Stolle and Bélanger2013).

Building on this base model, we then include a further, more proximate set of factors at each subsequent step of our analysis. Following the considerations above, the second step adds foreign policy values and affinities (Model 2). We are particularly interested, in this context, in internationalist values—commitment to what the Liberal government likes to call the “rules-based international order” (Freeland, Reference Freeland2017)—as a cornerstone of Canadian foreign policy. Based on the considerations above, we expect respondents with a commitment to internationalism to lean toward the Eurosphere model of transatlantic relations. We also examine people's affinity to Europe as a world region and to the UK. To measure affinities, we ask respondents to rank regions to which they feel the closest affinity/attachment (see Appendix A). This approach was chosen as an alternative to one that asks respondents to rate their affinities toward political objects. Although rankings are comparative assessments whereas ratings are absolute evaluations, recent research has found few practical differences between them (Moors et al. Reference Moors, Vriens, Gelissen and Vermunt2016, Reference Moors, Vriens and Gelissen2017). Krosnick (Reference Krosnick1999: 555–56) concludes that rankings tend to produce higher-quality responses than ratings; he argues that they are more reliable and have higher discriminant validity than ratings, as respondents are less likely to engage in satisficing. Our analysis of foreign policy values and affinities is guided by the following hypotheses:

H1a: Canadians who view the rules-based international order as an important foreign policy principle are comparatively more likely to hold negative views of Brexit and to put a priority on the development of Eurosphere relations.

H1b: Canadians with an affinity to Europe as a world region are comparatively more likely to hold negative views of Brexit and to put a priority on the development of Eurosphere relations.

H1c: Canadians with an affinity to the UK are comparatively more likely to hold positive views of Brexit and to put a priority on the development of Anglosphere relations.

In the third step of our analysis, we examine partisanship (Model 3). Our measure of partisanship focuses on its behavioural expression—specifically, which federal party respondents say they usually vote for. Vote choice has been used as a measure of partisanship in other studies of foreign policy attitudes (Berdahl and Raney, Reference Berdahl and Raney2010: 1009), and recent studies have argued that measures focused on the propensity to vote for a party can outperform other, traditional measures of party identification (Paparo et al., Reference Paparo, De Sio and Brady2020). Our measure of partisanship allows us to assess whether the divisions in statements by party leaders are shared among their supporters. If the Eurosphere/Anglosphere divide resonates beyond the party leadership, we would expect Liberal voters to lean toward the EU and expect Conservative voters to lean toward the UK. The leaders of the New Democratic party (NDP) and Bloc Québécois have not publicly formulated positions on Brexit. We assume based on previous studies (Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Bastedo and Hove2009; Fitzsimmons et al., Reference Fitzsimmons, Craigie and Bodet2014) that NDP voters align more closely with Liberals than with Conservatives, while Bloc Québécois voters face conflicting incentives—torn between sympathy for Brexit as a secessionist project and antipathy toward its supporters’ embrace of an Anglo identity (Hébert, Reference Hébert2019). This results in the following hypotheses:

H2a: Canadians who support the Liberal party or the NDP are comparatively more likely to hold negative views of Brexit and to put a priority on the development of Eurosphere relations.

H2b: Canadians who support the Conservative party are comparatively more likely to hold positive views of Brexit and to put a priority on the development of Anglosphere relations.

H2c: Canadians who support the Bloc Québécois are comparatively more likely to hold positive views of Brexit but to put a priority on the development of Eurosphere relations.

At the final stage of our analysis, we add issue-related preferences (Model 4). We include just one issue-related variable, which focuses on people's view of referendums as a device to settle contentious issues in a society. As discussed above, a positive view of referendums may make respondents more inclined to view Brexit with sympathy. We do not assume that this variable influences preferences on the future of transatlantic relations. Our hypothesis, therefore, is as follows:

H3: Canadians who support referendums as a mechanism to decide contentious issues are comparatively more likely to hold positive views of Brexit.

The data source for our analysis is a random digit dialing dual-frame (land- and cell-lines) hybrid telephone and online random survey of 1,013 Canadians, 18 years of age or older, conducted September 26–30, 2019. The survey was commissioned from Nanos Research and formed part of an omnibus survey. Participants were randomly recruited by telephone using live agents and administered a survey online. The response rate was 12 per cent. The results were statistically checked and weighted by age and gender using Census information. The sample is geographically stratified to be representative of Canada. The margin of error for the survey is ±3.1 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

Findings

The survey evidence shows a sizable majority of Canadians disapprove of Brexit. Respondents were asked: “The term ‘Brexit’ is used to describe the United Kingdom's decision to leave the European Union. How sympathetic are you towards the idea of Brexit?” Nearly two-thirds of respondents expressed a negative orientation, with 48 per cent choosing to describe their position as “unsympathetic” and 17 per cent as “somewhat unsympathetic.” Conversely, less than one- quarter expressed sympathy for Brexit, with only 11 per cent “very sympathetic” and 13 per cent “somewhat sympathetic.” Only 13 per cent indicated they were “not sure” how they felt.

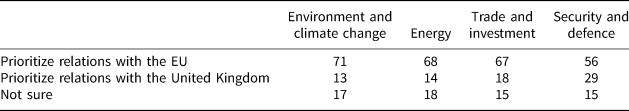

The results show respondents take an equally clear position on post-Brexit transatlantic relations, with considerably more respondents expressing a preference for relations with the EU over the UK (Table 1). Respondents were asked: “After Brexit, Canada may have to choose if it wants to prioritize relations with the United Kingdom or with the European Union. For each of the following policy fields, what do you think Canada's priorities should be?” In three areas—“environment and climate change,” “energy,” and “trade and investment”—more than two-thirds of respondents favoured giving precedence to relations with the EU, whereas between 13 and 18 per cent chose the UK. Views on “security and defence” were less uneven, with 56 per cent in favour of prioritizing EU relations and 29 per cent giving precedence to the UK.

Table 1 Views on Post-Brexit Relations by Policy Area, N = 1,013 (column percentages)a

a weighted data

Canadians, in the aggregate, clearly favour prioritizing relations with the EU across all four policy fields, but it is equally evident that at the individual level they do not distinguish between different policy fields when thinking about the future of Canada's relationship with the EU and the UK: an exploratory factor analysis reveals that all four items represent a single underlying attitudinal dimension.Footnote 3 Indeed, these four items form a reliable additive index of “post-Brexit priorities” (Cronbach's alpha = .83). Accordingly, we employ that index in subsequent analyses.

Sympathy for Brexit

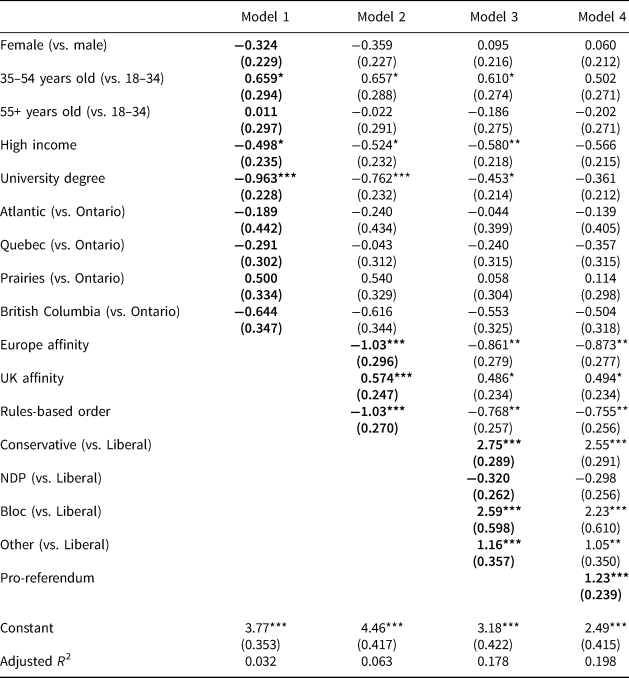

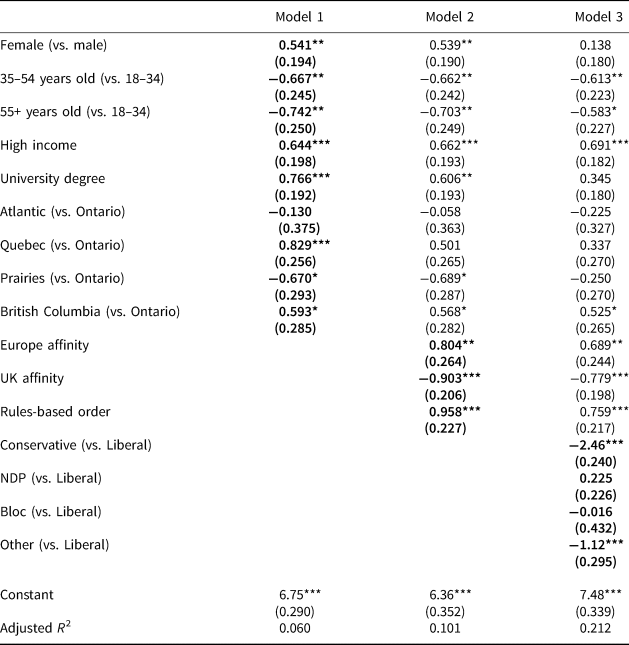

We begin with the multivariate models of attitudes toward Brexit (Table 2). All independent variables range from 0 to 1, and the dependent variable ranges from 0 to 10 (see Appendix A for variable coding and Appendix B for descriptive statistics). The parameter estimates for Model 1, which includes only socio-demographic factors, indicate that age and socio-economic status are both related to opinions about Brexit. Canadians between 35 and 54 years of age are more likely than their younger or older counterparts to support Brexit. Individuals in the 35–54 age group are an estimated 0.659 points more sympathetic toward Brexit on a 0 to 10 scale than those in the 18–34 age group (p < .05) and 0.648 points more sympathetic than those in the over 55 age group (p < .05). According to the estimates, Canadians with high incomes are 0.498 points less sympathetic than others toward Brexit (p < .05), and individuals with a university degree are nearly a full point (0.963) less sympathetic than others (p < .001). However, neither gender nor regional differences were statistically different from zero.

Table 2 Determinants of Views on Brexit, N = 1,013 (OLS regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses)a

a weighted data

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Three noteworthy results emerge when value and affinity factors—support for a rules-based international order, as well as affinities to Europe and the UK—are introduced in Model 2. First, support for a rules-based international order is associated with less sympathy for Brexit (b = −1.03, p < .001). Second, individuals who feel a close affinity to Europe also express less sympathy for Brexit: respondents with an affinity to Europe are an estimated 1.03 points less sympathetic, on average, than those with no affinity for Europe (p < .001). However, respondents with an affinity to the UK are an estimated 0.574 points more sympathetic than those with no affinity. H1a, H1b and H1c thus find support in our analysis.

Model 3 estimates show the impact of party loyalties on attitudes toward Brexit. In line with H2a–H2c, there is a clear divide: Conservative party supporters, Bloc Québécois supporters and supporters of “other” parties and independents view Brexit significantly more positively than Liberal or NDP supporters. Conservatives and Bloc supporters are an estimated 2.75 and 2.59 points higher, respectively, than Liberals on the 0-to-10 Brexit sympathy measure (p < .001). Independents and supporters of other parties are also more sympathetic toward Brexit than Liberals, by approximately 1.16 points (p < .001). NDP supporters express even less support for Brexit than Liberals; however, the difference between NDP and Liberal supporters (0.32 points) is not statistically different from zero. If partisan differences in views on Brexit were a consequence of different underlying orientations, we might expect diminished independent effects from those underlying orientations when partisanship is held constant. However, comparing Model 2 and Model 3 reveals that parameter estimates for affinities and values are only modestly weaker when partisan loyalties are taken into account.

Attitudes about referendums, introduced in Model 4, are also related to Canadians’ views on Brexit. H3 is confirmed: individuals who view referendums favourably are more than a point higher on the Brexit sympathy scale (1.23) than those with an unfavourable view (p < .001).

The post-Brexit future of Canada's transatlantic relationships

What about the future of Canada's transatlantic relationships? The results of multivariate analyses presented in Table 3 show that opinions about Canada's future transatlantic priorities are structured by socio-demographic factors and affinities, as well as partisanship. Again, all independent variables range from 0 to 1, and the dependent variable ranges from 0 to 10. The parameter estimates for Model 1 reveal significant differences according to gender, age, socio-economic status, and region. Women are more inclined than men to prioritize relations with the EU, by approximately 0.541 on a 0-to-10 scale (p < .01). Whereas 35-to-54-year-olds stood out from both younger and older age groups by expressing more positive attitudes toward Brexit, 18-to-34-year-olds have distinct views about Canada's future transatlantic priorities: they give higher priority to relations with the EU than either of the other two age groups. Higher income and a university degree are also associated with prioritizing the EU relationship. Finally, a regional pattern emerges, with residents of Quebec and British Columbia giving higher priority to relations with the EU than the rest of Canada and with residents of the Prairie provinces more inclined to prioritize relations with the UK.

Table 3 Determinants of Views on Post-Brexit Relations, N = 1,013 (OLS regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses)a

a weighted data

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

As the results in Model 2 show, values and affinities also influence views on post-Brexit relations. H1a–H1c are all confirmed: individuals who support a rules-based international order are not only more skeptical of Brexit, they also give precedence to Eurosphere relations. Individuals with a close affinity to the UK tend to prioritize Anglosphere relations, and those with a closer affinity to Europe are more inclined to favour relations with the EU.

Partisanship, introduced in Model 3, is an important determinant of Canadians’ views about future transatlantic priorities. Conservative supporters, as well as supporters of “other” parties and independents, give less priority than Liberal, NDP or Bloc supporters to EU relations. This is in line with H2a–H2c. It is noteworthy that although Bloc supporters are relatively sympathetic toward Brexit, those sympathies do not extend to giving precedence to UK relations. There is also little evidence to suggest underlying orientations shape these partisan views on future transatlantic priorities: as with views on Brexit, the independent effects of affinities and values are only modestly diminished when partisanship is taken into account in Model 3.

Partisanship: Elite cues or partisan world views?

What are we to make of the effects of partisanship on opinions about Brexit and the future of transatlantic relations? Are Canadians simply taking cues from political elites, or do these partisan differences represent something deeper? The results presented in Tables 2 and 3 have provided little evidence to suggest that these partisan differences are driven by affinities for the UK or Europe or by support for a rules-based international order: the effects of these affinities and values on opinions about Brexit and the future of transatlantic relations appear to be largely independent from partisanship. Perhaps, then, Canadians are taking their cues from partisan elites because they do not know enough about these issues. If that is the case, we ought to see a significant difference in the effects of partisanship between party supporters who are possibly cognizant of their own party's position on Brexit and those who unlikely to be aware of Brexit at all: in order to take partisan cues on an issue, even the least knowledgeable partisans need to be aware that the issue exists in the first place. Accordingly, if cue-taking matters, partisan differences in views on Brexit and post-Brexit relations will be smaller among those without minimal awareness of the Brexit issue compared to those who know something about Brexit.

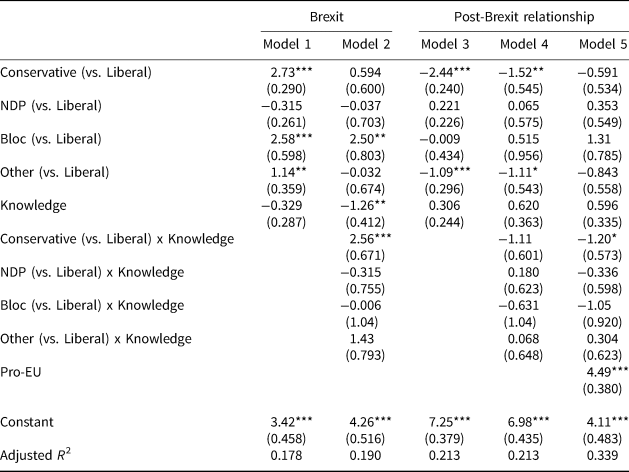

Our survey included a question that tested basic Brexit-related awareness, which asked respondents whether the UK in September 2019 was an EU member state (which it was). The effects of awareness are presented in Table 4, which shows the interaction between awareness and partisanship, with controls for socio-demographic factors and values/affinities. The Brexit results in Model 2 suggest cue-taking for Conservatives, Liberals and perhaps supporters of other parties and independents. The joint statistical significance of these interactions is high (F = 4.75; df = 4, 991; p = .0008). The differences between Liberals and Conservatives are significantly larger among those who are aware of the UK's status than among those who are not. The parameters for the constituent partisanship variables in the interactions indicate the effects of partisanship among those without basic awareness (that is, knowledge = 0). Notably, the difference between Conservatives and Liberals is relatively small and not statistically different from zero (b = 0.594; p < .323), and the difference between independents or “other” partisans and Liberals is effectively 0 (b = −0.032; p < .958). By contrast, the parameters for the interaction variables represent the change in the effects of partisanship when people have basic awareness (that is, knowledge = 1). These indicate much larger differences between Conservative and Liberal partisans who have at least some awareness of Brexit (the gap between the two partisan groups is 2.56 points larger), and the difference in the effect of partisanship between those with and without basic awareness is statistically different from zero (p < .0001). Similarly, the difference between “other” partisans and Liberals is much larger among those with at least some awareness of Brexit (b = 1.43), although this effect does not quite reach conventional levels of statistical significance (p < .073). However, there is no evidence of cue-taking for supporters of the Bloc Québécois.

Table 4 The Effects of Partisanship and Awareness (OLS regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses)a

a weighted data; controls for sociodemographics, values, and affinities are included in each model but not shown.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

While the evidence suggests some partisans take their cues from elites on the Brexit issue, the results with respect to post-Brexit relationships in Model 4 of Table 4 do not suggest cue-taking. Among those without even minimal awareness of Brexit, there are large and significant differences in opinion between Liberals and Conservatives (b = −1.52; p < .005) and between Liberals and independents or “other” partisans (b = −1.11; p < .04). However, none of the interactions between partisanship and awareness of Brexit are statistically significant individually or jointly (F = 1.19; df = 4, 991; p = .32). In this respect, partisans do not appear to simply echo elite opinion by taking cues from their parties; even partisans who are unaware of Brexit nevertheless take different positions on the future of Canada's transatlantic relationships.

Given that the Liberal and Conservative parties have taken distinctive and broadly stable postures on foreign policy for more than a decade (Paris, Reference Paris2014), it is perhaps unsurprising that even their relatively uninformed supporters share positions consistent with those stances. We observed that the Conservative party, for example, has shown a long-standing aversion to international and multilateral institutions. Perhaps Conservative partisans are more likely to favour post-Brexit relations with the UK because of an aversion to the EU? Three-quarters of all respondents to our survey described their overall view of the EU as “positive” or “very positive,” yet fewer than half of Conservative partisans expressed that sentiment. In Model 5, we control for these attitudes toward the EU. As we might expect, individuals with a very favourable opinion of the EU are more inclined to prioritize the EU relationship (b = 4.49; p < .0005). More importantly, however, when attitudes toward the EU are controlled, the difference between uninformed Liberals and Conservatives is not statistically different from zero (b = −0.591; p < .0269).

Discussion and Conclusion

Brexit has triggered a debate about Canada's foreign policy identity, in which the Eurosphere and the Anglosphere are presented as competing options for the country's international alignment. Our study has shown that this debate, conducted most prominently by the leaders of the Liberal and Conservative parties, is not just an artifact of overheated parliamentary competition. Rather, it resonates in the Canadian population. According to our survey, most Canadians have a negative view of Brexit and, when forced to choose, would prefer Canada to align more with the EU than with the UK. But there is much less domestic consensus than the Trudeau government's public declarations emphasizing its partnership with the EU and criticizing Brexit might suggest. Our analysis reveals that public opinion on Brexit and the future of Canada's transatlantic relationship is driven by foreign policy values and affinities, but it is also driven, in an even more pronounced way, by partisanship. Although Canadians are less evenly divided and polarized on Brexit than the British are, the partisan gap mirrors that of the UK, with a centre-right electorate that is significantly more likely to support Brexit and to prioritize Anglosphere relations than is the centre-left. Other research has suggested that partisan differences in opinions on some Canadian foreign policy issues might be explained by ideology (Fitzsimmons et al., Reference Fitzsimmons, Craigie and Bodet2014; Gravelle et al., Reference Gravelle, Scotto, Reifler and Clarke2014), but that does not seem to be the case with respect to Brexit opinions. At the same time, our research suggests that these differences cannot simply be reduced to people taking explicit cues from the party leadership on issues about which they know very little. On the issue of Brexit itself, there is some evidence in favour of cue-taking. However, views on the post-Brexit future seem to be shaped by other dynamics, including partisan differences in attitudes toward the EU. Perhaps Brexit has joined other salient foreign and non–foreign policy issues, such as position on Israel and abortion, in the dynamic of partisan sorting. Since foreign policy is usually not a high-level voting priority, Brexit may not determine election results, but it serves as a prominent expression of partisan identity.

How much do these public opinion patterns matter for foreign policy itself? In the Canadian context, it is often pointed out that partisan politics matter relatively little in foreign relations (Bow and Black, Reference Bow and Black2008/2009). Regarding Brexit specifically, it is noteworthy that the positions of the Liberal and Conservative parties differ little when it comes to short-term policy responses: both parties have expressed support for close ties with the UK, including a new trade agreement; neither has suggested that Canada should walk away from CETA and its strategic partnership with the EU. If a Conservative government came to power in Ottawa, Canada's foreign policy on Brexit would change, but not radically. A Conservative government would not denounce CETA, though it might prioritize its relations with London over Brussels, Paris and Berlin, as a way to galvanize the pro-Brexit segment of its electorate. By contrast, we can expect a Liberal government to continue to support strong relations with the EU, even if this means moving away from the “motherland.”

What may be more consequential for Canadian foreign policy, in the long term, is the clear divide in the population when it comes to visions of Canada's international identity. The resonance of the Eurosphere/Anglosphere distinction in public opinion, and the way in which it connects to partisanship, suggests that the traditional Canadian foreign policy conceptions—Europeanism, internationalism and continentalism—are realigning in the light of Brexit. The precise form that this realignment will take remains uncertain. Recent political debates suggest that Europeanism may shed its association with the Anglosphere while developing closer affinities with internationalism, which the EU—just like Canada—continues to defend. Attachments to British traditions may, in turn, become more aligned with models of US-focused foreign policy—in other words, traditional continentalism—as new alliances in the Anglosphere are being explored. The extent and shape of this realignment will, however, be strongly influenced by international factors, including the foreign policy priorities of the new US administration and the future relationship that develops between the UK and the EU. What we can say is that there is a potential, in Canadian party politics as well as public opinion, for the emergence of a new fault line in how Canada's role in the world, and the alliances that matter most to the country, are being perceived.

Data availability statement

Data and replication files for this article are available through the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/C8NNDF.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was supported by an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (“The Reconfiguration of Canada-Europe Relations after Brexit,” 435-2019-0770). For advice at various stages of the research process, the authors would like to thank Christopher Cochrane, Petra Dolata, Patrick Leblond, as well as Emilie Bossard and Nik Nanos. Three anonymous reviewers provided helpful suggestions.

Appendix A: Variable Coding

Brexit

Item wording: “The term ‘Brexit’ is used to describe the United Kingdom's decision to leave the European Union. How sympathetic are you towards the idea of Brexit?”

“very sympathetic” = 10, “somewhat sympathetic” = 7.5, “not sure” = 5, “somewhat unsympathetic” = 2.5, “unsympathetic” = 0

Post-Brexit relations

Item wording: “After Brexit, Canada may have to choose if it wants to prioritize relations with the United Kingdom or with the European Union. For each of the following policy fields, what do you think Canada's priorities should be?”

Each policy field (environment and climate change, energy, trade and investment, security and defence) was coded as follows:

“relations with the European Union” = 10, “unsure” = 5, “relations with the United Kingdom” = 0

The variable is the mean score across all four policy fields for each respondent.

Europe affinity

Item wording: “Please rank the two regions outside of North America you feel the closest affinity to where 1 is the closest affinity and 2 the second closest affinity?”

Regions (order randomized):

Europe

Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, Pacific islands)

Central America and the Caribbean

South America

East and South-East Asia

South Asia

Eurasia (Russia and Central Asia)

Middle East and North Africa

Africa South of the Sahara

Unsure

“Europe” selected as closest affinity = 1, “Europe” selected as second closest affinity = 0.5, all other responses = 0

UK affinity

Item wording: “Which European country, if any, do you feel the closest attachment to?” [Open-ended]

“Area of Great Britain/United Kingdom/British Isles (includes England, Scotland and Wales)” = 1, all other responses = 0

Support for a rules-based international order

Item wording: “When you think about Canada's relationship to Europe, please rank the following aspects of the relationship where 1 is the most important aspect and 2 is the second most important aspect of the relationship.”

“Canada and European countries are both committed to a rules-based international order” selected as most important aspect = 1, selected as second most important aspect = 0.5, all other responses = 0

Partisanship

Item wording: “Thinking about your view on Canadian federal politics, do you consider yourself someone who usually votes for the Liberals, the Conservatives, the New Democrats, the Bloc, the Greens, the People's Party or are you an independent?”

Dummy variables for the Liberals, the Conservatives, the New Democrats, the Bloc and “Other/independent” (the Greens, the People's Party, independent)

Support for the EU

Item wording: “How would you describe your overall view of the European Union?”

“very positive” = 1, “somewhat positive” = 0.75, “not sure” = 0.5, “somewhat negative” = 0.25, “very negative” = 0

Support for referendums

Item wording: “In Canada as well as in Europe, referendums are sometimes used to decide on contentious issues in a society. People have a variety of opinions about this. What is your opinion?”

“Referendums are a good way to decide contentious issues” = 1, “not sure” = 0.5, “Referendums are not a good way to decide contentious issues” = 0

Awareness

Item wording: “As far as you know, is the United Kingdom currently a member country or not currently a member of the European Union?”

“Currently a member of the European Union” = 1, “Not currently a member of the European Union” / “not sure” = 0

Gender

Female = 1, male = 0

Age

Dummy variables for three age groups: 18 to 34, 35 to 54, 55 and older

High income

$75,000 or more = 1, all other responses = 0

University degree

Completed university degree = 1, all other responses = 0

Region

Dummy variables for five regions: Atlantic Canada, Quebec, Ontario, Prairies, British Columbia

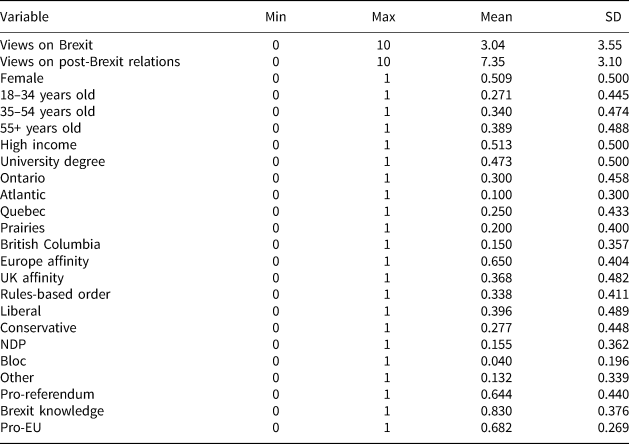

Appendix B: Descriptive Statistics