Introduction

The near-exponential growth of global fishing capacity, coupled with high rates of bycatch and relatively slow population recovery rates, has resulted in the large-scale depletion of shark populations worldwide (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Au and Show1998; Bonfil et al., Reference Bonfil, Meyer, Scholl, Johnson, O'Brien and Oosthuizen2005; Dulvy et al., Reference Dulvy, Baum, Clarke, Compagno, Cortés and Domingo2008). According to FAO fisheries statistics 720,000 t of sharks were landed in 2009; an independent estimate, based on the global shark fin trade alone, estimated c. 1.7 million t or c. 38 million sharks (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, McAllister, Milner-Gulland, Kirkwood, Michielsens and Agnew2006). Given that not all captured sharks are destined for shark fin markets, and the occurrence of illegal, unregulated and unreported shark catches (Pramod et al., Reference Pramod, Pitcher, Pearce and Agnew2008), these figures are underestimates. The discrepancy between official and unofficial figures highlights the overall poor regulation of shark fisheries, including the common practice of shark-finning in the open seas, where oversight is low to nil (Chen & Phipps, Reference Chen and Phipps2002), and the lack of knowledge on fishing statistics itself hinders management and conservation actions (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Myers, Kehler, Worm, Harley and Doherty2003).

With the exception of some charismatic species such as whale sharks Rhincodon typus, elasmobranchs (cartilaginous fish) as a group have historically been overlooked in conservation, largely because of a lack of scientific data (Vannuccini, Reference Vannuccini1999) and a generally negative public image (Topelko & Dearden, Reference Topelko and Dearden2005; Maniguet, Reference Maniguet2007). Nevertheless, thus far > 460 shark and ray stocks have been assessed for the IUCN Red List, most with recent reviews (IUCN, 2013), with parallel efforts to document and assess global shark fisheries and populations underway (Biery et al., Reference Biery, Palomares, Morisette, Cheung, Harper and Jacquet2011). Although this is only a starting point, it reflects an increasing awareness by the public, governments, conservation groups and academics of the need for shark conservation.

Amid uncertainty about the future of shark populations there is a growing interest in the economic benefits of sharks for ecotourism at both local and global scales (Topelko & Dearden Reference Topelko and Dearden2005; Clua et al., Reference Clua, Burray, Legendre, Mourier and Planes2011; Gallagher & Hammerschlag, Reference Gallagher and Hammerschlag2011). Some prominent shark watching sites are Ningaloo Reef, (Australia), Donsol (Philippines), Gansbaai (South Africa), Holbox Island (Mexico) and Gladden Spit (Belize; Irvine & Keesing, Reference Irvine and Keesing2007). As the diversity of these international locations suggests, the global distribution of sharks facilitates potential shark watching at many other sites. Economic benefits from shark watching are particularly evident at the local level (Gallagher & Hammerschlag, Reference Gallagher and Hammerschlag2011). For example, individual sharks in French Polynesia were estimated to have an ecotourism value of c. USD 1,200 per kg (based on data in Clua et al., Reference Clua, Burray, Legendre, Mourier and Planes2011, and species length–weight relationships), compared with a landed value to local fishers of USD 1.5 per kg for shark meat (Sumaila et al., Reference Sumaila, Marsden, Watson and Pauly2007).

Although we recognize the value and achievements of shark conservation efforts from an ethical perspective, here we analyse the issue from the viewpoint of management of an economic resource, using specific performance metrics. We provide the first global estimate of the current and potential contribution of shark ecotourism in terms of tourist participation, tourist expenditures and employment, and make comparisons with shark landed value from fisheries. We focus on these metrics as they are the benefits captured by tourism operators or fishers, who, unlike final consumers, have the most to gain or lose from practices that trade off ecological degradation for economic benefits (Ransom & Mangi, Reference Ransom and Mangi2010).

Methods

Shark watching is defined here as any form of observing sharks in their natural habitat without intention to harm them. Unless otherwise specified, we use the term shark to refer to sharks, rays and chimaeras. Shark watching includes observation from boats, or underwater with snorkel or scuba gear (with or without luring them with bait), during day trips or longer tours. The performance indicators that we focus on are (1) participation (the number of people who participate in shark watching at a given site), (2) employment (the number of full-time equivalent jobs directly supported by shark watching tourism at a given site), and (3) expenditures (tourism expenditures wholly or partially attributable to watching sharks in a given location). All values presented are in USD, at 2011 value. We frame our global analysis in terms of FAO regions and subregions (FAO, 2011), which makes it easier to visualize, compute and compare estimates over a wide range of ecosystems and socio-economic conditions.

Data collection

We conducted an extensive review of the literature available on shark watching and shark fishing worldwide. These sources included peer-reviewed publications, government, NGO and newspaper reports, internet websites, UN databases and personal enquiries.

Firstly, we identified sites where dedicated shark watching, as opposed to chance encounters, is known to occur. Two sources of information were invaluable. The Shark Watcher's Handbook (Cawardine & Watterson, Reference Cawardine and Watterson2002) provides in-depth documentation of > 260 sites around the world where it is possible to watch sharks in the wild, and, in a global review of shark ecotourism, Gallagher & Hammerschlag (Reference Gallagher and Hammerschlag2011) identify 83 shark watching sites of different types (e.g. general tourism, photography). We further screened sites to focus only on dedicated shark ecotourism and pooled some sites into more general locations (e.g. two individual dive spots at the same site are treated as one location) to facilitate data analysis.

This baseline information was complemented through extensive use of the search engines Google, Google Scholar, EBSCOHost, Academic Search Premier, Web of Science, and LexisNexis Academic, using the keywords shark, elasmobranch, fishing, fisheries, finning, conservation, tourism, ecotourism, watching, management, value, economic, tours, and diving. In addition, we contacted operators at several shark watching sites to obtain first-hand data on our selected indicators (participation, expenditures, employment) and asked them to suggest other operators they knew (i.e. snowball sampling). We continued our search until we were satisfied that all sites mentioned in our initial sources had been screened for potential data. In the case of live-aboard tours data were attributed to the site of departure rather than the destination site.

Data analysis

Given the paucity of site-specific data, a meta-analytical value-transfer method was used to estimate performance metrics in places where data were partially or wholly absent. Several authors have reviewed the methodology, uses and misuses of meta-analysis (e.g. Rosenthal & DiMatteo, Reference Rosenthal and DiMatteo2001; Shrestha & Loomis, Reference Shrestha and Loomis2001). Within the meta-analytical framework the premise of the value-transfer approach is that, in the absence of site-specific data, values from similar sites (in this case, within the same FAO-defined subregion) can be used as proxies for interpolation. This makes the value-transfer approach a useful tool to analyse large-scale issues that have substantial data gaps.

If data were not available for an identified site we employed a relatively simple value-transfer approach to estimate indicators, as follows. If data on expenditure at a given site were available, but not the number of participants or jobs supported, the mean expenditure per capita for shark watching for sites with available data in the corresponding FAO subregion or region (in that order, depending on availability) was used to estimate the number of participants at the site. Because there were limited data available on employment, employment to expenditure ratios were assumed to be comparable to those of recreational fishing and whale watching tourism operations, which are similar in nature to shark watching operations. If necessary we used country-specific values calculated for recreational fishing and whale watching by Cisneros-Montemayor & Sumaila (Reference Cisneros-Montemayor and Sumaila2010) to estimate employment.

In some instances no data on our indicators were available for identified shark watching sites. To estimate data for these sites we used a ranking system dependent on the scale of operations at each site compared to those with available data. Thus, sites were assigned a class; i.e. a number reflecting their size relative to others in the same subregion. For example, if the number of shark watchers was unknown for site X, it would be assigned the average number of shark watchers for sites in its subregion, multiplied by its class, for example 0.2, thereby assuming that the site had 20% as many shark watchers as others in the same subregion. Classes were initially assigned based on relative tourist arrivals to countries within each subregion (UN World Tourism Organization, 2011) and in some cases revised based on first-hand knowledge of relative participation at specific sites. In the case of large countries such as Australia, Canada and the USA we used state-, province- or territory-level tourism arrivals. Revisions to classes always tended to the conservative side, under the assumption that sites without available data tend to be smaller in scale but should nonetheless be represented. Following this system, values for participation, expenditures and employment in shark watching were estimated for all identified sites around the world.

Projected growth

The classic tourism growth model follows a logistic pattern with discrete stages of establishment, development, consolidation and maturity (Butler, Reference Butler1980) and has been extensively documented and tested against real data (Cole, Reference Cole2009). To provide an estimate of potential future industry growth, we fitted a logistic model to available trend data to obtain the maximum (asymptote) value relative to current visitor numbers. Although future growth is expected for tourism in general (UN World Tourism Organization, 2011) we did not factor in the addition of new shark watching sites and thus our projection is conservative.

Shark fisheries

To contextualize the contribution of shark watching tourism at a global scale, key data on global shark fisheries, including landings, trade, and landed value, were compiled using FAO statistics (FAO, 2011), and species and country-specific ex-vessel prices were compiled from Sumaila et al. (Reference Sumaila, Marsden, Watson and Pauly2007).

Results

Shark watching

We identified and focused data collection on 70 sites, within 45 countries, all five FAO regions, and 14 subregions (Fig. 1), which were identified as overwhelmingly dedicated to shark watching for at least part of the year. Data were found for 31 sites, which provided the basis for subsequent estimations (sources cited in Table 1). In addition to interviews, data were also gathered from the peer-reviewed literature (n = 6), reports and conference proceedings (n = 5), government and NGO reports (n = 7) and one personal communication.

Fig. 1 Shark watching sites included in this study; filled circles denote sites with available economic data, open circles are sites with no available data.

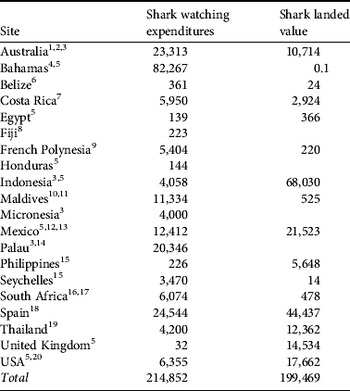

Table 1 Locations (by country, in alphabetical order) with available data on annual shark watching expenditure (for countries with > 1 site, only available data are included here; i.e. no estimates are included). Shark landed values are total for the country using taxon-specific landings and price (based on data from Sumaila et al., Reference Sumaila, Marsden, Watson and Pauly2007; data not available for Fiji, Honduras, Micronesia and Palau). All values are per year, in USD × 1,000 (at the 2011 rate).

Data sources: 1Stoeckl et al., Reference Stoeckl, Birtles, Farr, Mangott, Curnock and Valentine2010; 2Catlin et al., Reference Catlin, Jones, Norman and Wood2010; 3Heinrichs et al., Reference Heinrichs, O'Malley, Medd and Hilton2011; 4Cline, Reference Cline2008; 5This study; 6Carne, Reference Carne2008; 7E. Sala, pers. comm.; 8Brunnschweiler, Reference Brunnschweiler2010; 9Clua et al., Reference Clua, Burray, Legendre, Mourier and Planes2011; 10Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Shiham Adam, Kitchen-Wheeler and Stevens2010; 11Anderson & Waheed, Reference Anderson and Waheed2001; 12Iñiguez-Hernández, Reference Iñiguez-Hernández2008; 13De la Parra-Venegas, Reference De La Parra-Venegas2008; 14Vianna et al., Reference Vianna, Meekan, Pannell, Marsh and Meeuwig2010; 15Norman & Catlin, Reference Norman and Catlin2007; 16Dicken & Hosking, Reference Dicken and Hosking2009; 17Hara et al., Reference Hara, Maharaj and Pithers2003; 18De la Cruz et al., Reference De La Cruz-Modino, Esteban, Crilly and Pascual-Fernández2010; 19Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Dearden, Catlin and Norman2008; 20Manta Pacific Research Foundation, 2007 (in Heinrichs et al., Reference Heinrichs, O'Malley, Medd and Hilton2011)

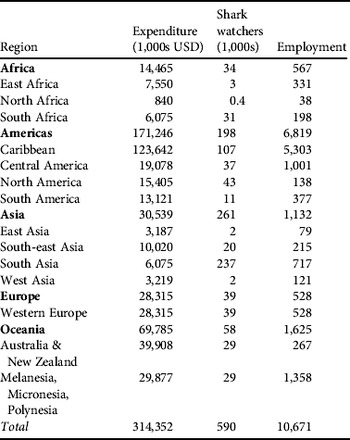

Our results suggest that every year > 590,000 shark watchers at dedicated sites generate > USD 314 million, supporting > 10,000 jobs around the world. Our initial available data and estimation results are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Overall, there were four main groups of sites with respect to expenditure: < USD 1 million per year (n = 25), USD 1–5 million (n = 30), USD 5–10 million (n = 9), and > USD 10 million (n = 6). Sites with available expenditure data had a mean expenditure of USD 6.5 million per year, whereas sites with estimated data averaged USD 2.3 million per year.

Table 2 Estimated annual economic benefits of shark watching by region (FAO, 2011). Expenditures are in USD (at the 2011 rate); employment is in full-time equivalents.

Dedicated shark watching concentrates on species that aggregate in specific temporal and spatial patterns and occur relatively close to the surface. The main species we identified were the whale shark, great white Carcharodon carcharias, tiger Galeocerco cuvier, angel Squatina spp., hammerhead Shpyrna spp., Galapagos Carcharhinus galapagensis, thresher Alopias spp., sandbar Carcharhinus plumbeus, basking Cetorhinus maximus and reef (Carcharhinus spp., Triaenodon spp.) sharks, and the manta (Manta birostris, Manta alfredi) and sting (Dasyatidae) rays.

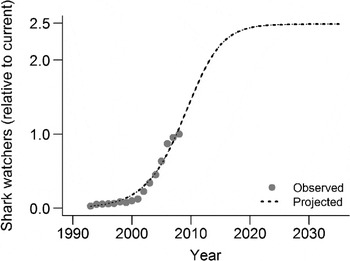

Shark watching sites with information available on tourist arrivals had a mean yearly increase of 27% over the last 2 decades. Assuming logistic tourism growth the trend in total numbers of shark watchers (sum of available time series) was fitted to a logistic model to project future numbers. This resulted in an asymptote at c. 2.5 times current levels (Fig. 2). Within a range between current observed values and the projected increase, and assuming expenditure per capita remains constant, global shark watching could generate expenditures of USD 314–785 million within 20 years.

Fig. 2 Observed and projected total numbers of shark watchers at sites with trend information (Donsol, Philippines; Gladden Spit, Belize; Ningaloo, Australia; Holbox Island, Mexico). Estimates are the result of a logistic model fitted to observed data and extrapolated to estimated asymptote. All values are relative to 2008. Data sources: Cohun (Reference Cohun2005), Remolina-Suárez et al. (Reference Remolina-Suárez, Pérez-Ramírez, González-Cano, de la Parra-Venegas, Betancourt-Sabatini, Trigo-Mendoza, Irvine and Keesing2007), Pine (Reference Pine2007), Catlin et al. (Reference Catlin, Jones, Norman and Wood2010).

Shark fisheries

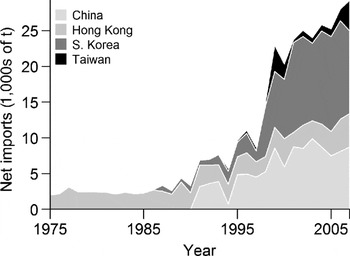

According to official statistics > 720,000 t of sharks were landed in 2009, a 20% decline from the historical maximum in 2003 and totalling c. USD 630 million in landed value (based on data from FAO, 2011, and Sumaila et al., Reference Sumaila, Marsden, Watson and Pauly2007). Over 50% of all shark catches were made by the 10 countries (Indonesia, India, Spain, Taiwan, Mexico, Pakistan, Argentina, USA, Japan and Malaysia) with the highest average shark catches during the decade (Lack & Sant, Reference Lack and Sant2009). Although catches and landed value are declining (Fig. 3), global commodity trading of shark products has increased, largely as a result of increased demand from emerging Asian economies that value shark products, particularly shark fin soup, as luxury goods (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 Global shark landings and landed value (based on data from FAO, 2011, and Sumaila et al., Reference Sumaila, Marsden, Watson and Pauly2007).

Fig. 4 Net imports of shark products in main Asian markets (based on data from FAO, 2011).

Discussion

Shark watching as an economic activity has expanded globally (Fig. 1). The sum of expenditures at sites with available information is c. USD 215 million per year, which is more than the total landed value of sharks in the corresponding countries (Table 1). Our estimates, including sites without available economic data, suggest that, globally, shark watching generates > USD 314 million, almost half the current value of global shark fisheries, and supports > 10,000 jobs (Table 2).

There is a mean annual increase in visitors at shark watching sites of almost 30% during the last 20 years and visitor numbers should increase further as new sites become established. Based on observed growth trends, shark watching may attract 2.5 times as many visitors as today within 2 decades (Fig. 2), which would generate USD 785 million in direct visitor expenditures. Although this assumes constant expenditure per capita, real (inflation-adjusted) ticket prices at some sites have increased by 25% in the last decade, signalling increased demand from tourists (Gallagher & Hammerschlag, Reference Gallagher and Hammerschlag2011). Meanwhile, global shark landings and landed value have been steadily declining, mainly as a consequence of overfishing (Fig. 3). It is important to keep in mind that global shark fishing effort has increased and expanded spatially (Myers & Worm, Reference Myers and Worm2003; Swartz et al., Reference Swartz, Sala, Tracey, Watson and Pauly2010), making catch declines during the past decade of great concern. Furthermore, nearly all value from shark products is created in the luxury goods sector, particularly in Asian markets (Fig. 4). One bowl of shark fin soup may sell for > USD 100 in Hong Kong but the average price paid to a fisher for a shark is c. USD 0.75 kg−1 (based on data in Sumaila et al., Reference Sumaila, Marsden, Watson and Pauly2007).

Although there is an increasing number of documented shark watching operations, their economic contribution is unknown at many sites (Fig. 1), making estimates necessary for a global analysis. Although the limited quantity and type of data did not allow for proper sensitivity analyses, we have attempted to provide conservative estimates, recognizing uncertainty. Aside from possible errors in source data, the main potential error in our results is in the selection of sites to include in the estimation. In a review of global shark watching, Gallagher & Hammerschlag (Reference Gallagher and Hammerschlag2011) identified 86 sites where shark watching occurs; under our criteria, only 70 sites were chosen. Our results are therefore conservative because at least some values would be estimated for any included site, although our method does avoid potential issues with sites where sharks are often seen but are not the central attraction for tourists. Sites with large shark watching operations tend to be over-represented in the literature, so our methods stressed conservative estimation. Using global subregions and relative tourist arrivals helped to mitigate potential upward bias in estimates for sites without data, with revisions to site class providing an additional check where necessary. Overall, sites with available data averaged c. USD 6.5 million in annual expenditures compared to c. USD 2.3 million for estimated sites.

The number of tourists (c. 590,000; Table 2) that currently participate in shark watching should be considered in the context of their impact. As a form of ecotourism, participation in shark watching is important because it can lead to increased awareness and support for conservation (Garrod & Wilson, Reference Garrod and Wilson2003; M. Barnes, unpubl. data), although this depends on how ecotourism operations are managed and implemented (Topelko & Dearden, Reference Topelko and Dearden2005). There are concerns regarding potential ecological impacts of ecotourism because of direct and indirect disturbance to organisms and habitat, including noise pollution (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Trites and Bain2002) and damage to coral reefs (Davis & Tisdell, Reference Davis and Tisdell1995). In the case of shark watching, the practice of feeding sharks or chumming the water to attract them has been questioned because of possible effects on shark behaviour (Maljković & Côté, Reference Maljković and Côté2010). Although well managed ecotourism sites have generally resulted in improved ecosystem health and structure, these potential negative effects must be considered to ensure that sites provide sustained benefits.

Sharks are widely distributed throughout the world's oceans and therefore shark watching can occur anywhere (Fig. 1). However, dedicated shark watching currently targets c. 10–20 species that are spatially and temporally accessible to humans (Gallagher & Hammerschlag, Reference Gallagher and Hammerschlag2011). The same traits that make some shark species amenable to tourism can also benefit conservation efforts because, charismatic appeal aside, species that aggregate in known temporal and spatial patterns, within sight of humans, may be easier to monitor and protect. This is especially true of species that aggregate near reefs or other fixed locations that can be designated as marine protected areas, providing a safe haven for shark populations at local and regional scales (Sala et al., Reference Sala, Aburto-Oropeza, Paredes, Parra, Barrera and Dayton2002; Knip et al., Reference Knip, Heupel and Simpfendorfer2012). Highly migratory shark species require other types of regulations, as even protected area networks may not be adequate (Lucifora et al., Reference Lucifora, García and Worm2011). Reducing fishing mortality for overexploited species is a priority for any management framework that aims to achieve sustainable shark fisheries and conservation but we must design strategies for mortality reduction that are both effective and feasible.

As the ecological and economic value of sharks is increasingly recognized, more areas primarily for conservation of sharks (commonly referred to as shark sanctuaries) are being established around the world, including almost 13 million km2 in the last 2 years alone, with some major players (i.e. Mexico, Taiwan) in global shark fisheries planning similar protection measures (Gronewold, Reference Gronewold2011; Ho, Reference Ho2011). Even relatively poor fishing communities, or those with important shark fisheries, may be amenable to conserving sharks given proper economic incentives, including the realization of sustainable income through shark watching ecotourism. The role of side payments, a form of benefit sharing in which tour operators pay a fee to adjacent fishing communities not to fish at specific reefs, has emerged as an interesting option in this context (e.g. Brunnschweiler, Reference Brunnschweiler2010). This type of strategy could be further explored in sites that have localized aggregations of sharks whose continued survival can benefit both fishers and tourism. Fishers can also enter the tourism industry themselves, as is occurring in several sites (e.g. Rossing, Reference Rossing2006; Irving & Keesing, Reference Irvine and Keesing2007). Although there are significant challenges to transitioning from fishing to tourism, the common theme in success stories is international attention and aid in the form of capacity building, including marketing strategies, customer service improvement and strong animal welfare guidelines, usually in the form of a code of conduct for tour operators.

Regarding the contribution of shark watching to the conservation of sharks, comparisons can be made with whale watching. The demise of the whaling industry, which has led to marked improvements in many whale populations, was sealed by prohibitions on catch but was also a result of decreased demand for whale products (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Gallman and Hutchins1988). However, the emergence of the global whale watching industry, currently generating > USD 2 billion a year (O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Campbell, Cortez and Knowles2009) and with potential for further growth (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Reference Cisneros-Montemayor, Sumaila, Kaschner and Pauly2010), has added a new dimension to arguments in support of conservation and responsible resource use. Working to promote consumer awareness and support for sustainability is therefore vital (Jacquet & Pauly, Reference Jacquet and Pauly2007), as increasing the number of environmentally aware tourists willing to pay to enjoy healthy ecosystems and shark populations will bring new economic options to coastal communities and both local and national governments.

Although not all shark species and/or sites lend themselves to tourism, those that do must be protected and invested in to secure sustainable economic benefits. Shark ecotourism cannot by itself provide conservation incentives to all fishers, particularly where sharks migrate or move seasonally. However, it is an increasingly important industry, with high potential for further growth. Together with more effective controls on global fisheries and an added focus on consumer awareness of unsustainable fishing practices, shark watching could prove crucial for the future status of shark populations. The potential and realized benefits of shark watching will thus depend on the actions and decisions of coastal communities and governments, with an increasingly real economic incentive for conservation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mary O'Malley of Shark Savers, Stefanie Brendl of WildAid and Hawaii Shark Encounters, Celia Faircloth at Hawaii Shark Encounters, Joe Pavsek of North Shore Shark Adventures, Richard Peirce of the Shark Conservation Society, Steve Fox at Deep Blue Utila, Jim Abernethy, Charles Hood, Mauricio Handler, Hannah Jones, Wilf Swartz (University of British Columbia), Mariana Walther (University of Queensland, Australia), Enric Sala (National Geographic Society) and others who contributed to this study with data, insights, suggestions and comments. We thank the Pew Charitable Trusts for their financial support.

Biographical sketches

Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor is a marine resource economist who specializes in ecosystem approaches to fisheries and ecotourism management. His work focuses on sustainable development at global and local scales. Michele Barnes-Mauthe is an interdisciplinary social scientist who specializes in marine resource socio-economics. Her work seeks to contribute to a more thorough integration of the social and economic components of marine resource systems to achieve long-term sustainability and conservation. Dalal Al-Abdulrazzak is a marine ecologist specializing in long-term changes in the ecology and fisheries of the Persian Gulf. Estrella Navarro-Holm is a marine biologist who specializes in shark biology and ecology. She is involved with media outreach work to foster marine conservation, including television and documentary collaborations with the BBC and the Travel Channel. Rashid Sumaila is interested in how economics, through integration with ecology and other disciplines, can be used to help ensure that environmental resources are sustainably managed.