A. The Rise of Human Rights in Climate Litigation

Over the past decades, climate litigation—broadly defined as cases that relate to climate change mitigation, adaptation, or climate scienceFootnote 1—has become a fixture in national and international courts.Footnote 2 Initially, litigation focused primarily on statutory interpretation,Footnote 3 with parties intent on ensuring, or undermining, the regulatory effect of statutes related to climate change mitigation measures, mostly via national courts.Footnote 4 Since these early cases, litigation has been initiated against states and private parties at national, regional, and international levels.Footnote 5 In addition to administrative claims, cases founded in civil law—primarily via the vehicle of tort law—and even criminal law, have been brought before the courts.Footnote 6 The narrative that emerged from these cases is one of progressive judicial action on climate change in the face of governmental inaction and regulatory failure at the national and international level.Footnote 7 This framing—though welcomed by many societal groups and scholarsFootnote 8—has led to debates on the constitutional position of courts vis-à-vis the legislature,Footnote 9 and questions as to the “appropriate” use of litigation within the legal system.Footnote 10

Since the 2010s, human rights claims have started to play an increasingly important role in climate litigation.Footnote 11 The use of human rights in environmental protection has taken place primarily through the “greening” of existing human rights law,Footnote 12 and there has been a noticeable convergence and cross-fertilization in related case law from the different human rights systems, including the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the American Convention on Human Rights (AmCHR), and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (AfCHPR).Footnote 13 The greening of human rights refers to the application, and interpretation, of rights such as the right to life, the right to private life, and the right to possessions and property in such a way so as to impose positive obligations on the government to regulate environmental risks, or disclose environmental information.Footnote 14 It has also led to the enforcement of environmental obligations against private actors, at times beyond existing statutory obligations.Footnote 15

The use of human rights in climate litigation is in many ways a logical extension of the use of human rights in environmental protection more generally.Footnote 16 This development has been problematized in specific ways; most significantly, through the objection that the protection of the environment based on human rights reflects a deeply anthropological approach to environmental degradation, which does not reflect the intrinsic importance of the environment apart from, and beyond, its relation to human welfare.Footnote 17 Pragmatically, human rights have proven to be one of the most promising avenues for environmental protection in the absence of regulation, or in the face of regulation that is considered inadequate.Footnote 18 Recent European casesFootnote 19—including the Urgenda jurisprudence, especially in the appeals,Footnote 20 the case of Milieudefensie v Royal Dutch Shell,Footnote 21 and the ruling against the German Federal Climate Change ActFootnote 22—plaintiffs have successfully invoked domestic and international human rights to ensure more ambitious public and private climate action.Footnote 23

Within the European Union, two human rights instruments have played a central role in the development of this jurisprudence: The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (the Charter).Footnote 24 The ECHR is one of the oldest and most influential human rights instruments in force today, having entered into force in 1953.Footnote 25 Its membership extends beyond the European Union Member States to countries such as Albania, Turkey, and Russia.Footnote 26 Compared to the ECHR, the Charter is a relatively young instrument. The Charter was introduced as part of the most recent EU Treaty reforms, which came into force in 2009.Footnote 27 There are several other fundamental differences between the scope, application, and ambitions of the ECHR and the Charter that will be discussed in detail below.

This article considers the respective roles of the ECHR and the Charter in climate litigation, specifically in light of recent climate litigation before the courts of EU Member States. The ECHR has been formative for the protection of fundamental rights in the EU and in many ways has shaped the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Many of the rights overlap and the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights may expressly be used to interpret Charter rights that overlap with those in the ECHR.Footnote 28 However, as is discussed in more detail below, the EU’s—and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)’s—ambitions for the Charter is for it to provide much stronger and more ambitious protection than the ECHR. This is possible due to the nature of EU law—specifically its primacy—and the remedies that the CJEU and national Courts are able to offer for violations of EU law. However, the Charter is, as the analysis in this article will show, far less frequently invoked in the context of climate litigation in the European Union. As these cases continue to proliferate and European policy on climate change becomes an ever-more central part of the EU’s raison d’être, examining these developments is particularly timely.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: It first provides an overview of relevant differences, and overlaps, between the Charter and the ECHR when it comes to their respective potential roles in climate litigation (Section B). The subsequent analysis of case law from the European Member States shows that, in practice, the emerging picture is one of the Charter playing a secondary role to the ECHR (Section C). In light of this reality, the article concludes by reflecting on the future role of the Charter in climate litigation, and in shaping environmental human rights (Section D).

B. European Human Rights Instruments in Climate Litigation: Potential

There are several ways for citizens of European Member States to challenge climate related action, or inaction, on a human rights basis:Footnote 29 First, they can challenge action, or inaction, by reliance on human rights protected by domestic law, for example in constitutional protections,Footnote 30 or protected by international human rights treaties, such as the ECHR or the Charter.Footnote 31 Second, human rights can play a role as interpretative tools in the application of other rights and/or legal provisions. For example, in determining the standard of care under national tort law.Footnote 32 In both situations, domestic courts would be the first port of call, after which cases may escalate to international bodies such as the ECtHR—in case of the ECHR—or the CJEU—in case of reliance on the Charter and/or involving other issues of EU law.

The ECtHR has played an important part in the initial jurisprudence on human rights-based environmental protection.Footnote 33 This prominence reflects the ECtHR’s fundamental role in human rights protection generally, and the timing of the initial cases involving human rights related to the environment, which predated the adoption of the Charter.Footnote 34 The importance of this jurisprudence cannot be overstated. At the same time, the Strasbourg court has also been careful to stress that national authorities are best placed to assess and act on environmental issues and that wide discretion will be awarded to them in doing so.Footnote 35 This position is in line with the more broader position of the ECHR as providing a minimum level of rights protection—a “floor”Footnote 36—and the margin of appreciation that it awards to domestic authorities and courts in its application.Footnote 37 The scope of the margin of appreciation remains notoriously vague but has played an important role in shaping the rights under the ECHR and the relationship between the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and domestic courts.Footnote 38 While generally considered a “strong” source of rights protection, reinforced by a “strong” international court, the margin of appreciation and the non-binding nature of the ECtHR’s judgments,Footnote 39 as well as the lengthy road to the ECtHR, are reminders of the challenges of enforcing international law, including the ECHR,Footnote 40 domestically and internationally.Footnote 41

Compared to the ECHR, the position of the Charter within the EU’s legal order is an entirely different one. Perhaps most importantly, the Charter differs from the ECHR insofar that it looks to set a “ceiling” for the level of human rights protection, not a floor. This is reflected in Article 52(3) and (4) of the Charter, which emphasize that Charter rights shall be interpreted in harmony with international and domestic traditions without preventing the EU from providing “more extensive protection.”Footnote 42

These provisions affect the relation between the Charter and fundamental rights protection in the Member States based on national constitutions, as well as the relationship between the Charter and the ECHR. The relationship between the Charter and national constitutional human rights was subject of a much-debated preliminary reference brought by the Spanish Constitutional Court. In Melloni, the protection provided by Spanish constitution was higher than that provided by the Charter.Footnote 43 The Court held that the principles of primacy, uniformity, and effectiveness of EU law meant that Member States could only uphold higher standards of human rights protection, if such a measure does not conflict with these principles.Footnote 44 Put differently, Member States can apply national standards of fundamental rights protection only in cases of minimum harmonization, and even then the principles of primacy, uniformity, and effectiveness need to be respected. This clearly limits the extent to which national courts and authorities may set higher standards than EU law based on their constitutional provisions. While this reasoning and holding is in line with established CJEU jurisprudence, it can create problems within a national legal order. Prior to the Melloni judgment, the Spanish Constitutional Court had held that the Charter was compatible with the Spanish Constitution given that it set a minimum level of protection.Footnote 45 The CJEU’s divergence from the Spanish court’s reading of Article 53 of the Charter presents a challenge to this, and other, national constitutions.

Vis-à-vis the ECHR and the ECtHR, the CJEU follows the jurisprudence of the ECtHR in case of overlapping provisions, but does not hesitate to set a higher standard of protection if it sees fit. The CJEU’s interpretation of Article 52 and its position on fundamental rights protection more generally has complicated the potential joining of the ECHR by the EU, which has been the express intention of the Member States and EU institutions.Footnote 46 The CJEU has advised negatively on the Draft Agreement that was to make this joining possible, stating that the agreement violated Article 6(2) of the Treaty on European Union by undermining the CJEU’s autonomy and the autonomy and primacy of EU law generally.Footnote 47 This means that the EU institutions remain, for the time being, outside of the jurisdiction of the ECtHR. This can be problematic in cases where compliance with an ECtHR judgment by a Member State can only be achieved through a change in EU legislation.Footnote 48

It is clear from its jurisprudence, including its negative opinion on the Draft Agreement on the accession of the EU to the ECHR, that the CJEU views the Charter as the touchstone for ambitious fundamental rights protection within the EU and its Member States.Footnote 49 This is reflected in its interpretation of Article 51 of the Charter which stipulates its scope of application. Article 51(1) provides that the Charter applies “only” to actions of EU institutions and Member States in the implementation of EU law.Footnote 50 On its face, this suggests that the scope of the Charter is more limited than that of the ECHR in terms of parties and areas of law.Footnote 51 However, the CJEU had read this provision as meaning that any connection to EU law brings actions within the application of the Charter.Footnote 52 Similarly, Article 51(1) suggests little to no horizontal effect of the Charter. However, the Court of Justice has applied the Charter in cases between private actors, specifically in cases where the right protected by the Charter was supported by other provisions of EU law or captured in general principles of EU law.Footnote 53 The Court has moreover explicitly held that Article 51(1) on the Charter’s scope does not preclude the possibility that individuals too may be required to comply with certain provisions of the Charter.Footnote 54

Looking more specifically at climate litigation, neither the ECHR nor the Charter incorporate any substantive or procedural environmental rights, specifically a right to a healthy environment.Footnote 55 That said, Article 37 of the Charter does establish a principle of environmental protection, which reads: “A high level of environmental protection and the improvement of the quality of the environment must be integrated into the policies of the Union and ensured in accordance with the principle of sustainable development”.Footnote 56 However, close analysis of Article 37, its relationship to the other Charter provisions, Article 11 TFEU and EU law more generally, and its appearance—or lack thereof—in CJEU jurisprudence, indicates that Article 37 currently does not provide any limits or obligations on actors with respect to environmental protection or integration.Footnote 57 Nevertheless, the potential of Article 37 for “greening” actions of EU actors via the Charter is considerable,Footnote 58 given the EU’s environmental, and climate, ambitions;Footnote 59 the fact that there is virtually no area of environmental policy that is not dominated by EU law;Footnote 60 and that the scope of Article 37 arguably extends far beyond environmental legislation.Footnote 61 Also in terms of remedies, reliance on the Charter by plaintiffs provides distinctive benefits, such as the ability to request the disapplication of the conflicting national measure in case of a violation, which may not be available when relying on the ECHR or national constitutions.Footnote 62

Another important provision with respect to climate litigation is Article 47 of the Charter, which establishes the right to an effective remedy and to a fair trial. This Article has played a central role in addressing some of the weaknesses of the EU’s approach to implementing the Aarhus Convention,Footnote 63 for example with respect to the standing of environmental associations.Footnote 64 The general principle of effective judicial protection has a long history in the European courts’ jurisprudence and is arguably a broader one than that articulated in Article 47 of the Charter.Footnote 65 Recent analysis of the CJEU’s case law on this topic, up to December 2019, shows that in general terms, the Court has increasingly used Article 47 to boost the effectiveness of the Aarhus Convention, even if there is no clear underlying right that would trigger the application of the Charter.Footnote 66

The above shows that both the ECHR and the Charter provide bases for human rights-based claims in the climate litigation context. However, as mentioned, the actual use of these instruments varies significantly in practice. Section C analyzes the actual use of both these instruments in European Union Member State courts thus far.

C. European Human Rights Instruments in Climate Litigation: Practice

Since the early 2010s, there has been a considerable increase in climate litigation cases that reference human rights instruments. Our focus here is on a subset of these cases, namely those that are brought before a national court of one of the European Member States, the CJEU, or the ECtHR.

The landscape of human rights-based climate litigation in the EU comprises various levels of national and international courts, as well as national and international human rights instruments. In order to provide an overview of the state of play so far, we draw on the Climate Change Litigation database hosted and maintained by Columbia Law School’s Sabin Centre for Climate Change.Footnote 67 This database represents the most complete overview of climate jurisprudence currently in place. It also provides the service of an English summary of cases brought in jurisdictions that would otherwise be beyond the linguistic capabilities of the author. The database comprises two databases: One focused exclusively on US climate litigation, and one that collects all non-US climate litigation. Our search was limited to the latter. Within this database, we used the parameters “suits against governments” and “suits against corporations and individuals” within the category of “Human Rights” and/or the principal law being the ECHR, in order to further filter our results. This means that the legal basis for the claims in these twenty judgments is the ECHR, the Charter, national constitutional rights, or a combination.

A search based on these parameters resulted in seventeen cases,Footnote 68 the earliest of which was lodged in 2014, the most recent in 2021.Footnote 69 The vast majority of cases—fifteen—were brought before national courts of EU Member States. Cases brought in the UK after January 1, 2020 were excluded. Two cases were brought before the European Court of Justice; one in reference to the EU’s greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and one related to the revised Renewable Energy Directive and its categorization of forest biomass.Footnote 70 The latter was dismissed as being manifestly unfounded, the former—which relied on a multitude of substantive Charter rights, including Articles 2, 3, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, and 24—was dismissed for lack of standing. With the exception of the case of Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell, all cases were brought against a national and/or regional government, or an EU institution.

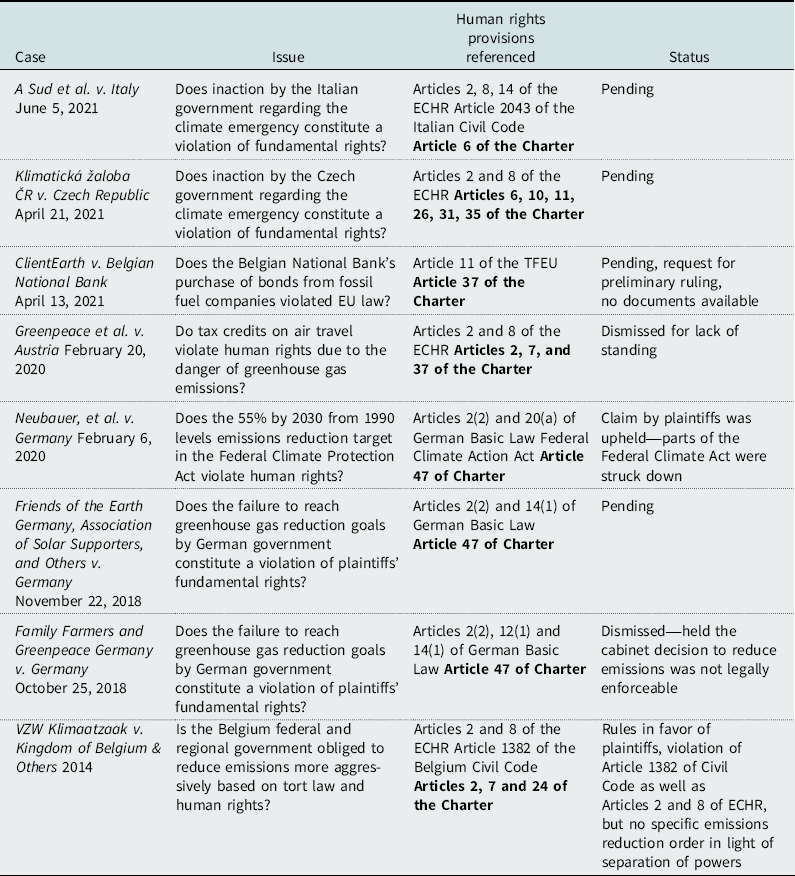

Eight of the fifteen cases before national courts reference the Charter.Footnote 71 Table 1 provides an overview of these eight cases and their causes of action, in reverse chronological order based on date of lodging of complaint.

In some ways, this remaining sample of cases is overinclusive; all cases that reference Charter provisions at any stage of the proceedings have been included. This means that if the Charter is referenced by one of the parties in their submissions, the case is included in this overview—even if the court later does not refer to, or base its decision on, these provisions. For example, in VZW Klimaatzaak v. Kingdom of Belgium & Others, the Flemish Region asked the Court to refer a question to the CJEU as to the compatibility of the EU ETS Directive and the Effort Sharing Regulation with Articles 2, 7, and 24 of the Charter.Footnote 72 The Court does not engage with this in its judgment and instead decides on the basis of Article 1382 of the Civil Code and Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR.

In three cases—noticeably all before a German court—Article 47 of the Charter is used to deal with problems of standing. Though it is unclear why the plaintiffs decided against strengthening their national fundamental human rights protection with Charter rights, this use of the Charter nevertheless constitutes an important development for a rights-based protection more generally by providing access to the courts and paving the way for human rights-based climate litigation. Of the four cases that rely on substantive Charter rights—A Sud et al. v. Italy, Klimatická žaloba ČR v. Czech Republic, ClientEarth v. Belgian National Bank, Greenpeace et al. v. Austria—one has been dismissed for lack of standing—Greenpeace et al v Austria—and three are pending. Interestingly, the two cases that refer to both the ECHR and the Charter—A Sud et al. v. Italy and Klimatická žaloba ČR v. Czech Republic—rely on different rights contained in both documents. Whereas some cases would cite, for example, the right to life under the respective Articles 2 of the ECHR and the Charter, in these cases, different human rights from each instrument are referenced.Footnote 73 The actual role that the Charter will play in this set of cases is yet to become clear.

Keeping in mind that the sample of cases is a very limited one, and that the field of human rights-based climate litigation itself is rapidly developing, a few observations may be made based on this overview. First, climate litigation in which a rights-based approach is adopted relies predominantly on national constitutional protections or rights expressed in the ECHR. Second, reference to the Charter is limited, with reference to procedural rights and/or rights also contained in the ECHR being most common, indicating that the effect of Article 47 has been a positive one with respect to climate litigation. Third, Article 37 of the Charter does not yet play a meaningful role in climate litigation.

D. The Future of the EU Charter in Climate Litigation

In 2012, Alan Boyle analyzed the first wave of litigation aimed at “greening” human rights.Footnote 74 In the context of this broader development, he argued that climate change cannot be easily addressed through existing human rights because:

[i]t affects many states and much of humanity. Its causes, and those responsible, are too numerous and too widely spread to respond usefully to individual human rights claims. [… ] The response of human rights law—if it is to have one—needs to be in global terms, treating the global environment and climate as the common concern of humanity.Footnote 75

Over the past decade, Boyle’s observation has remained valid; much of the successful human rights-based climate litigation thus far excludes the interests of populations outside the national jurisdiction of the court in question, limiting its ability to meaningfully address this global problem.Footnote 76 However, Boyle’s prediction that these cases could not lead to the derailment of economic policies driving greenhouse gas emissions has aged less well.Footnote 77 The decisions taken in Urgenda, Neubauer, and with respect to private parties, also Milieudefensie v. RDS, have led to real changes to climate policies.Footnote 78

The EU claims to be at the forefront of both environmental and human rights protection. The latter has been demonstrated by the adoption of the Charter and the subsequent jurisprudence of the CJEU regarding the ambitious standard of protection it is meant to provide.Footnote 79 The rise of rights-based approaches in climate litigation would suggest that these two aspects provide a mutually reinforcing opportunity for plaintiffs in the EU—before national and European courts—to use the Charter to push for more ambitious climate action by Member States and/or the EU institutions. The fact that most cases are currently brought against Member States, rather than against private parties, and concern an area of shared competence—climate policy—which place these cases firmly within the scope of application of the Charter,Footnote 80 are factors that reinforce this assumption. However, as the above analysis shows, the Charter actually plays a rather marginal role in the climate litigation landscape. When it is cited—in half the cases, reference to the Charter is missing entirely—its effect is very limited. Reference to Article 47 is most common, which may be in part explained by its links to the Aarhus Convention and its European implementation with which environmental plaintiffs, such as environmental NGOs, have relatively extensive, and positive, experience.

This situation speaks to important issues regarding the penetration of EU law into domestic legal orders, the perception of EU law by lawyers and judges, and the relationship between the European courts. These issues deserve a separate contribution with its own methodology, centered on in-depth interviews with parties involved in these cases, which the author looks forward to engage with in the future. Some small clues as to this relationship may already be glimpsed from the jurisprudence; in Neubauer, the Court expressly engages with the question whether a constitutional complaint may be raised against the Federal Climate Change Act, given that the Act implements the EU’s Effort Sharing Regulation.Footnote 81 Specifically, it admits that “[i]t is true that the Federal Climate Change Act might be regarded in some respects as implementing EU law within the meaning of Article 51(1) first sentence of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.”Footnote 82 However, it also finds that caselaw of the German Constitutional Court and the CJEU allow for constitutional review in this situation.Footnote 83

The Court’s observation is in line with the two scenarios identified by de Boer where Member States may still be able to apply national rights standards that are higher than that of the EU: Where the Member States have discretion in implementing EU law and do so in line with national rights provisions without affecting the primacy of EU law, and where a derogation from EU law strengthens rather than undermines EU law’s effectiveness.Footnote 84 Put differently, the German courts,’ and several others,’ reluctance to bring these cases into the scope of EU law or deciding them in reference to the Charter does not pose a legal problem.Footnote 85 It does however speak to an avoidance of judicial dialogue between the national and European courts on these issues. This avoidance limits the development of the Charter as a key instrument for human rights protection in general, and in climate litigation in particular.Footnote 86