Introduction

In the recent global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2017: 2) describes dementia as ‘an umbrella term for several diseases that are mostly progressive, affecting memory, other cognitive abilities and behavior, and that interfere significantly with a person's ability to maintain the activities of daily living’, configuring it as a public health priority. For many years, dementia care has been dominated by the standard medical approach (Katzman et al., Reference Katzman, Terry and Bick1978), in which dementia is treated mainly with drugs, such as anti-anxiety, antidepressant and anti-psychotic medications (Bond, Reference Bond1999; Sabat, Reference Sabat, Downs and Bowers2008). The pervasive use of medications has often been accompanied by so-called malignant social psychology, a phrase coined by Kitwood (Reference Kitwood1990) for a style of interaction enacted by care-givers, which had the effect of depersonalising the treatment administered to persons with dementia. According to this approach, the loss of cognitive skills causes the loss of personhood (e.g. personal background, preferences, desires, interests, willpower); consequently, people with dementia have to be forced to execute daily self-care activities at prescheduled timesFootnote 1 (Doyle and Rubinstein, Reference Doyle and Rubinstein2013).

With the aim of seeking effective treatments for patients with dementia, over the last decades, a wide-ranging debate has emerged across different disciplines, such as psycho-gerontology, clinical gerontology, health economics and sociology of medicine. Within this framework, several authors have criticised the pervasive use of drugs for the management of behavioural and physiological symptoms related to dementia, showing how this kind of over-treatment can be both negative for the individual (Edge, Reference Edge2009) and expansive for the collectivity (Glasziou et al., Reference Glasziou, Moynihan, Richards and Godlee2013; Guzzon et al., Reference Guzzon, Rebba, Boniolo and Paccagnellaforthcoming). At the same time, other studies have shown that the behavioural symptoms of dementia (e.g. depression, anxiety, agitation, wandering) are partially due to brain damage and partially caused by the ways in which the person is treated by healthy people (Killick and Allan, Reference Killick and Allan2001; Sabat, Reference Sabat2001; Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2002).

As an alternative to the standard medical approach, the concept of person-centred care has been proposed and developed by various authors (Kitwood and Bredin, Reference Kitwood and Bredin1992; Sabat and Harré, Reference Sabat and Harré1992; Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997, Reference Kitwood1998; Sabat and Collins, Reference Sabat and Collins1999), in which good dementia care has to be built around the individual's needs and is contingent on knowing the person through an interpersonal relationship. The person-centred approach is rooted in the work of Tom Kitwood, who – along with Kathleen Bredin – suggests that dementia does not universally progress in a linear fashion, and most importantly, it varies from person to person (Kitwood and Bredin, Reference Kitwood and Bredin1992). At the same time, other works show that patients with significant cognitive impairments have manifestations of their identities, values and beliefs (Sabat and Harré, Reference Sabat and Harré1992; Jaworska, Reference Jaworska1999; Sabat and Collins, Reference Sabat and Collins1999). More recently, starting from the principles of person-centred care, Hughes et al. (Reference Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2009: 301) have used the concept of supportive care, intended as ‘a full mixture of biomedical dementia care, with good quality, person-centred, psychosocial, and spiritual care under the umbrella of holistic palliative care throughout the course of the person's experience of dementia, from diagnosis until death’. With the concept of supportive care, the authors emphasise that person-centred care has to be extended throughout the course of the illness, guaranteeing the overall wellbeing of people with dementia and their relatives.

We conducted an integrative review addressing this research question:

• What are the organisational implications of supportive care interventions (SCIs) in long-term care facilities for people with dementia?

To answer this question, we focused on three interventions – person-centred, palliative and multi-disciplinary care – that play a key role in supporting people with dementia, according to Hughes and colleagues (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2009; Hughes, Reference Hughes2013). Although the clinical effects of SCIs on the health status of people with dementia have been shown by various works, the organisational implications related to the implementation of these interventions are still under-investigated.

This paper is structured as follows. In the next two sections, we respectively introduce the notion of supportive care in dementia and show the methodology used in our literature review. We then focus on the results of our review, specifically the organisational implications of SCIs in long-term care organisations, regarding quality of care, care-givers’ quality of life and cultural backgrounds. Finally, based on the presented results, we draw our conclusions.

Supportive care in dementia

Following the definition by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2005), long-term care for older people can be described as support and care activities undertaken to ensure that people with loss of function and capacity are able to maintain their wellbeing. This can encompass care provided in the individual's own home or in an institutional setting (Milte et al., Reference Milte, Ratcliffe, Bradley, Shulver and Crotty2019). In our work, we focus on the latter case, using the concept of long-term care facilities intended as ‘nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, and assisted living facilities … [that] provide a variety of services, both medical and personal care, to people who are unable to manage independently in the community’.Footnote 2

As Neil Henderson explains, in western societies, the placement of elderly people in long-term care organisations has been represented as a form of a double burial for a long time:

when a person is extracted from home because of dependencies that interrupt his or her ability, or his or her family's ability, to cope with the exigencies of life, the nursing home placement process becomes step one of a double burial ritual … At this point, the sometimes lengthy step two of the double burial ritual begins. Rather than lie supine on the burial scaffold, as in some cultures, the patient languishes in long-term care parenthood until biological functions cease, at which time the second, and final, burial occurs. (Henderson, Reference Henderson2003: 154–155)

SCIs seem to challenge this representation of long-term care facilities for elderly people with dementia, strongly connected with the dominance of the standard medical approach, transforming these organisations in contexts where people with dementia are actively cared for and stimulated by competent professionals. The approach of supportive care has been previously experimented with in cancer care to address the patients’ clinical and psycho-social needs in order to provide an optimal quality of life (Klastersky et al., Reference Klastersky, Libert, Michel, Obiols and Lossignol2016). In cancer care, supportive care includes control of acute complications of the illness and/or its therapy, the management of pain and chronic complications, psycho-social and ethical-existential support once oncological therapy is no longer curative and, finally, the approach to the end of life (Carrieri et al., Reference Carrieri, Peccatori and Boniolo2018). Only in recent times have some works begun to apply this concept in dementia care (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2009; Hughes, Reference Hughes2013). As Hughes argues,

the point about supportive care is that, not only does it extend across the complete time course of the condition, not only is it intended to be broad in the sense of biopsychosocial and spiritual, but – a practical level – nothing is ruled out and everything should be ruled in. (Hughes, Reference Hughes2013: 9)

Therefore, supportive care seems characterised by continuous support of patients and relatives from diagnosis until death, through a holistic approach to care and, finally, high flexibility in choosing the right care practices for each case. Starting from these considerations, it has been possible to individuate three key SCIs, which are at the core of our review.

First, ‘supportive care in dementia must be person-centred and, as such, it must be individual’ (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2009: 99). As suggested by Brooker (Reference Brooker2003), the person-centred approach can be summarised by the acronym VIPS: valuing people with dementia and their care-givers, treating them as individuals, adopting the perspective of the person with dementia and maintaining the person's social environment because of the fundamental importance of relationships in sustaining personhood. From this perspective,

individuals need comfort or warmth to ‘remain in one piece’ when they may feel as though they are falling apart … Individuals need to be socially included and involved both in care and in life [Pinkert et al., Reference Pinkert, Köhler, von Kutzleben, Hochgräber, Cavazzini, Völz, Palm and Holle2021], and more than simply being occupied; they need to be involved in past and current interests and sources of fulfilment and satisfaction. (Fazio et al., Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018: 11)

Various reviews have underlined the following effects of the person-centred approach on resident outcomes: controlling the behavioural symptoms of residents, slowing their decline in the cognitive sphere and in activities of daily living, reducing the use of medication and defending their quality of life (Moos and Björn, Reference Moos and Björn2006; Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Jakobsson Ung, Swedberg and Ekman2013; Li and Porock, Reference Li and Porock2014).

Second, as the dementia progresses, the goals of care shift to include palliative care and remove much aggressive treatment from the care plan for patients (Brauner et al., Reference Brauner, Muir and Sachs2000). The diffusion of the person-centred care approach has affirmed the idea that people with dementia may be cared for and that care practices can improve their quality of life, also in the final stage of the illness. Palliative care in dementia is characterised by three key aspects: affirmation of life, encouraging people to live and, at the same time, to accept the inevitability of death; alleviating the distressing symptoms of whatever form and maintaining the quality of life; and a holistic approach during the end stages of dementia, assuring the biological, psychological, social and spiritual wellbeing of patients and their relatives (Hughes, Reference Hughes2013: 9). Various studies have shown how palliative care interventions have positive effects on patients with dementia, e.g. decreasing any observed discomfort (Volicer et al., Reference Volicer, Hurley, Lathi and Kowall1994), increasing the prescription of analgesia (Lloyd-Williams and Payne, Reference Lloyd-Williams and Payne2002) and relieving delirium symptoms (Agar et al., Reference Agar, Lawlor, Quinn, Draper, Caplan, Rowett, Sanderson, Hardy, Le, Eckermann, McCaffrey, Devilee, Fazekas, Hill and McCaffrey2017).

Third, to meet patients’ and relatives’ needs, dementia care has to be provided by multi-disciplinary teams. Multi-disciplinary teams are crucial for paying attention to various dimensions, such as biological, psychological, social and spiritual aspects of care. As observed by Grand et al. (Reference Grand, Caspar and MacDonald2011), team members often include professionals such as neurologists, geriatricians, neuropsychologists, nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists and nutritionists. To assure continuity of care throughout the course of the illness, professionals have to be co-ordinated by a key worker, appointed at the time of the diagnosis, who follows people with dementia and their relatives from the onset to the bereavement. In this case as well, the added value of a multi-disciplinary approach has been underlined by some reviews and studies on dimensions such as diagnostic accuracy (Wolfs et al., Reference Wolfs, Dirksen, Severens and Verhey2006), cognitive impairments, functional deficits, and behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (Grand et al., Reference Grand, Caspar and MacDonald2011).

As observed in cancer care, the implementation of SCIs seems to have several positive and critical organisational implications that practitioners have to take into account (Carrieri et al., Reference Carrieri, Peccatori and Boniolo2018). On one hand, these practices enrich care processes; on the other hand, they are often obstructed by infrastructural, professional and cultural barriers.

Method: an integrative review

To explore the organisational implications of supportive care in long-term care facilities for people with dementia, we conducted a review (1999–2019) focused on person-centred, palliative and multi-disciplinary care. We followed the integrative review method, which is specific and summarises past empirical or theoretical literature to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular phenomenon or health-care problem (Broome, Reference Broome, Rodgers and Knafl2000). This methodological approach includes five stages that guide the review design: (a) problem and purpose of the review identification; (b) literature search strategy description; (c) data and methodological quality evaluation; (d) data analysis, which includes data reduction, display, comparison and conclusions; and (e) presentation, which synthesises findings in a model that comprehensively portrays the integration process and describes the implications for practice, policy and research, as well as the limitations of the review (Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005; Hopia et al., Reference Hopia, Latvala and Liimatainen2016).

After identifying the problem (the organisational implications of supportive care in long-term care facilities for people with dementia), we began the study with an exploration of the literature addressing the implementation of supportive care in the residential setting. However, we soon realised that only a few studies have explicitly used the concept of supportive care in dementia. Consequently, we decided to redefine the scope of our review, individuating the key supportive care interventions and re-addressing the research around them. Our new aim was to analyse the organisational implications of supportive care interventions (i.e. person-centred, palliative and multi-disciplinary care) in long-term care facilities for people with dementia.

Search strategy and criteria for inclusion

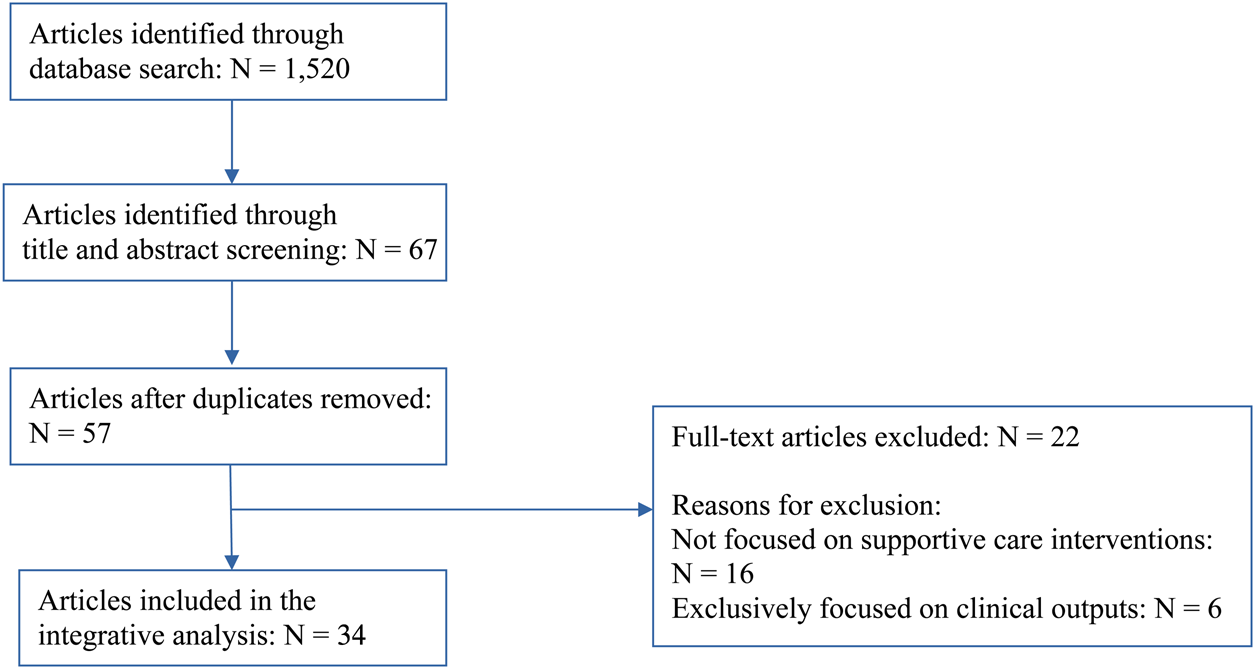

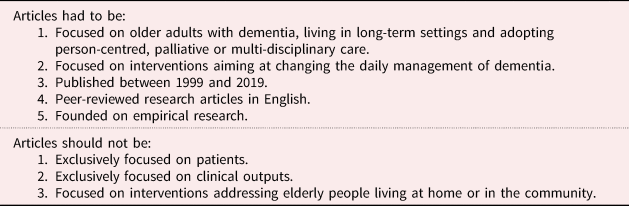

Next, we defined our search strategy, identifying the inclusion and the exclusion criteria (Table 1). We searched published studies through the following databases: Google Scholar, PubMed and SAGE Journals. Electronic databases were searched using all combinations of the following keywords: dementia, long-term facilities, residential settings, person-centred care, palliative care, multi-disciplinary teams, evaluation, implementation and impact. With the aim of assuring the quality of selected papers, we restricted our search to empirical peer-reviewed research articles in English. We focused on articles published in academic journals because in journal articles, the knowledge about a specific topic is more consolidated compared with conference papers or book chapters. Afterwards, we screened selected papers – first, by abstract and second, by full text. A final sample of 34 articles was listed (see × Figure 1).

Figure 1. Procedure for the selection of studies.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Quality appraisal of included studies

Before beginning the in-depth analysis of the selected contributions, the quality appraisal was undertaken using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2017), based on items relating to study design, data collection, data analysis and reporting of outcomes. Each article was awarded a quality rating of high, moderate or low, depending on the percentage of the answers that were coded as having met the criteria. The principal reviewer (FM) assessed the quality of all the articles, and the other three members of the research team (FN, GB and OP) checked for accuracy within their subsets. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation. The quality appraisal was undertaken to aid in interpreting the findings and in determining the strength of the conclusions drawn; no study was excluded based on the results of the quality assessment.

Data collection and analysis

A content analysis (Schreier, Reference Schreier2012) of the articles that met the inclusion criteria was performed. A spreadsheet was used to summarise the main empirical findings of the articles. A subsequent comparison of the thematic segments led to the identification of interpretive categories through which the final analysis was conducted. The three conceptual categories included implications for care processes, implications for the quality of life of (formal and informal) care-givers and implications for cultural backgrounds.

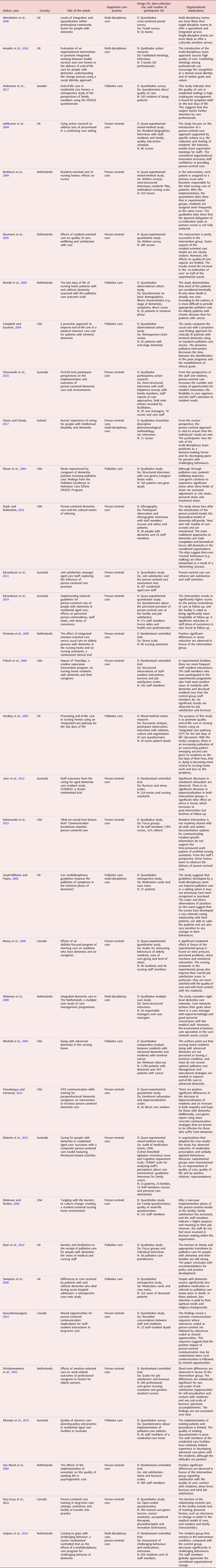

Exploring supportive care interventions in dementia: person-centred, palliative and multi-disciplinary care

The review included 21 studies focused on the implementation of person-centred care, ten on palliative care and six on multi-disciplinary care (see Table 2). Three studies (Lloyd-Williams and Payne, Reference Lloyd-Williams and Payne2002; Cleary and Doody, Reference Cleary and Doody2017; Zwijsen et al., Reference Zwijsen, Smalbrugge, Eefsting, Twisk, Gerritsen, Pot and Hertogh2014) provided findings in more than one area and were therefore listed in more than one SCI. We considered 21 quantitative, eight qualitative and five mixed-method studies. As for their geographical spread and settings, the studies were conducted primarily in the United States of America (USA) (N = 8), the Netherlands (N = 8), the United Kingdom (UK) (N = 7) and Australia (N = 6), with the remainder undertaken in Canada (N = 3), Sweden (N = 1) and Ireland (N = 1). Regarding the sample, 23 studies gathered data only about staff members, six only about patients, three about staff and patients and two about staff, patients and relatives.

Table 2. Details of the studies included in the review

Notes: UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

Person-centred care

The first strand of the contributions pays attention to the effects of person-centred care (and of associated training programmes) on various organisational dimensions in long-term care facilities, such as the quality of provided care, the quality of work of formal care-givers, the professional skills of managers and workers, and the organisational cultures.

First, a significant number of the considered studies also focus on the consequences of person-centred models on care processes. Person-centred care improves the number of interactions and the attitude of the personnel towards elderly people and increases the flexibility in care regimes (Fritsch et al., Reference Fritsch, Kwak, Grant, Lang, Montgomery and Basting2009; Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Jeon, Stein-Parbury, Forbes, Fleming, Cook and Tinslay2015), as well as the communication skills of professionals (Ashburner et al., Reference Ashburner, Meyer, Johnson and Smith2004; Passalacqua and Harwood, Reference Passalacqua and Harwood2012) and continuity of care (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Boumans, Van Breukelen, Abu-Saad and Nijhuis2004; Boumans et al., Reference Boumans, Berkhout and Landeweerd2005). From the staff's perspective, these changes are vital to ensure that the individuals’ needs are met (Cleary and Doody, Reference Cleary and Doody2017). Moreover, except for the study conducted by Boumans et al. (Reference Boumans, Berkhout and Landeweerd2005), there is consensus that person-centred care increases the quality of care, with particular reference to the following dimensions: staff's and families’ satisfaction with the quality of care (Van Weert et al., Reference Van Weert, Van Dulmen, Spreeuwenberg, Bensing and Ribbe2005; Robinson and Rosher, Reference Robinson Sherry and Rosher2006; Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Sandman and Borell2014; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Morley, Walters, Malta and Doyle2015) and the ability to involve relatives in decisions concerning their relatives (Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Jeon, Stein-Parbury, Forbes, Fleming, Cook and Tinslay2015). However, during the implementation of person-centred care models, some critical issues arise. Kolanowski et al. (Reference Kolanowski, Van Haitsma, Penrod, Hill and Yevchak2015) point out that time constraints, as well as lack of sufficient staff and of information systems to support information exchange, obstruct person-centred care. In particular, in this study conducted in the USA, the staff members identify the unmet need for access to the residents’ psycho-social/medical histories and the knowledge of the strategies that the families used for managing behavioural symptoms in the past. In research carried out in Canada, Savundranayagam (Reference Savundranayagam2014) shows that during the interactions between the staff and the residents, utterances coded as person-centred (e.g. calling the resident by name, asking about his or her desires and preferences) are followed by utterances coded as missed opportunities (i.e. instances where person-centred communication strategies could have been used to preserve and/or enhance a resident's sense of self). The author suggests that the positive impact of person-centred communication may be undermined when followed by missed opportunities.

Second, much research pays attention to the effects of person-centred care on the quality of work. The implementation of person-centred care models seems to have positive effects on job satisfaction (Schrijnemaekers et al., Reference Schrijnemaekers, Van Rossum, Candel, Frederiks, Derix, Sielhorst and Van Den Brandt2003; Van Weert et al., Reference Van Weert, Van Dulmen, Spreeuwenberg, Bensing and Ribbe2005; Robinson and Rosher, Reference Robinson Sherry and Rosher2006; Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh, McAuliffe, Nay and Chenco2011). Taking into consideration staff in Australian residential aged-care facilities, Edvardsson et al. (Reference Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh, McAuliffe, Nay and Chenco2011) show that staff perception of the provision of person-centred care is associated with increased personal satisfaction, as well as the awareness of having a more balanced workload and receiving more professional support. According to the authors, this happens because with person-centred care, there is an increment of self-perceived personal and professional growth, feelings of worthwhile accomplishments and perceived quality of work. Two studies (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Boumans, Van Breukelen, Abu-Saad and Nijhuis2004; Fritsch et al., Reference Fritsch, Kwak, Grant, Lang, Montgomery and Basting2009) find no difference in the job satisfaction between experimental groups (i.e. staff members who work in facilities that adopt person-centred care) and control groups. Other works show how person-centred care reduces staff stress and, in particular, time pressure, perceived problems, stress reactions and emotional exhaustion (Mezey et al., Reference Mezey, Fulmer, Wells, Dawson, Sidani, Craig and Pringle2000; Finnema et al., Reference Finnema, Dröes, Ettema, Ooms, Adèr, Ribbe and Tilburg2005; Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Sandman and Borell2014). In this respect, Jeon et al. (Reference Jeon, Luscombe, Chenoweth, Stein-Parbury, Brodaty, King and Haas2012) point out that significant effects of stress decline at follow-up. The overall improvement of the quality of work seems to have positive effects in terms of decreasing sick leave (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Boumans, Van Breukelen, Abu-Saad and Nijhuis2004) and increasing staff retention (Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh, McAuliffe, Nay and Chenco2011).

Finally, as well known, organisational change is often accompanied by conflicts. As underlined by some studies (Viau-Guay et al., Reference Viau-Guay, Bellemare, Feillou, Trudel, Desrosiers and Robitaille2013; Doyle and Rubinstein, Reference Doyle and Rubinstein2013), person-centred care promotes a culture of care that can radically differ from the pre-existing cultural assumptions and beliefs about dementia, often related to the so-called medical standard care. In their ethnographic study of an American long-term care organisation, Doyle and Rubinstein (Reference Doyle and Rubinstein2013) investigate the ways in which pre-existing organisational practices and cultural backgrounds can obstruct organisational change. The authors show how, during the transition period, practices inspired by person-centred care become interwoven with ‘standard’ practices characterised by depersonalising patients with dementia. Changing beliefs and assumptions about dementia – and, consequently, patient care practices – seems a huge challenge that can be overcome only by enacting specific strategies (e.g. increasing the social engagement between the residents and the staff members).

Palliative care

Although the symptoms experienced in the last year of life by people with dementia and by cancer patients are comparable (see McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Addington-Hall and Altmann1997), e.g. in terms of experienced pain and loss of appetite, patients with dementia are at particular risk of receiving poor end-of-life care.

Most of the studies focused on the application of palliative care in dementia assess the care processes and their quality, often in comparison to the palliative care provided to patients with other diseases. Various studies note how patients with dementia may be receiving different end-of-life care from that received by patients who are cognitively intact (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Kiely and Hamel2004; Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Deliens, Steen, Ooms, Ribbe and Wal2005; Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Gould, Lee and Blanchard2006). Older people receive significantly less palliative medication prior to death; most patients are not recognised as dying, hospice referrals are infrequent (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Kiely and Hamel2004) and symptom relief is inadequately managed (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Lindqvist, Fürst and Brännström2017). In patients where dementia is noted, less attention is paid to their psycho-social and spiritual needs and religious backgrounds (Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Deliens, Steen, Ooms, Ribbe and Wal2005; Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Gould, Lee and Blanchard2006). According to the two last cited groups of authors, patients with dementia can be assisted in non-physical aspects empowering non-verbal communication. As reported by some of the reviewed literature (Lloyd-Williams and Payne, Reference Lloyd-Williams and Payne2002; Campbell and Guzman, Reference Campbell and Guzman2004; Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Deliens, Steen, Ooms, Ribbe and Wal2005; Hockley et al., Reference Hockley, Dewar and Watson2005), improving the quality of palliative care requires implementing dedicated programmes in residential facilities. If not supported by organisational change processes, national guidelines risk being insufficient (Silvester et al., Reference Silvester, Fullam, Parslow, Lewis, Sjanta, Jackson, White and Gilchrist2013).

Other works consider the effects of palliative care aimed at improving the quality of life of people with dementia and their relatives (e.g. Lloyd-Williams and Payne, Reference Lloyd-Williams and Payne2002). They show how such interventions improve various aspects of the quality of care (e.g. pain control and more appropriate attention to patients’ previously stated wishes). In a qualitative study carried out in the USA, Diwan et al. (Reference Diwan, Hougham and Sachs2004) note that although patients’ wellbeing improves, care-givers continue to experience significant stress when three kinds of strain are assessed: adjustment or role strain (i.e. work adjustment, family adjustments, change in personal plans and other demands on time), personal strain (i.e. physical strain, financial strain, sleep disturbance, feeling confined and feeling overwhelmed) and emotional strain (i.e. being upset because the patient has changed, the patient's behaviours are upsetting and emotional adjustment). Patient problem behaviours and functional limitations, perceived lack of support from the health-care team and higher socio-economic status are predictors of care-giver strain. The authors suggest that it is necessary to develop effective programmes that offer meaningful end-of-life support and care for both patients with dementia and their families.

If it is well known that the needs of patients with dementia and their relatives are often underestimated by health-care professionals, less attention has been paid to the reasons behind this attitude. Through a qualitative study conducted in the UK, Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, Gardiner, Bellamy, Gott and Ingleton2012) explore the role played by professionals in either facilitating or obstructing the transition to palliative care for people with dementia. The research suggests that considerable difficulties remain in the achievement of good-quality end-of-life care in the form of palliative services for people with dementia. First of all, health-care practitioners often do not perceive people with dementia as candidates for palliative care for many reasons. For some study participants, the idea that dementia constitutes a condition that can be a cause of death is questionable. Dementia is sometimes interpreted as a normal pathological aspect of ageing rather than a specific illness; other ‘conditions’ are considered worthy of specialist palliative care, in contrast to dementia. Moreover, health-care professionals recognise that current skills and competencies within health-care teams are insufficient to assess the needs of people with dementia. In particular, for the participants, it is problematic to work with a group of people who find it difficult to communicate their needs. Consequently, in an uncertain context, professionals often have recourse to pharmaceutical, rather than behavioural, interventions. Finally, the team members suggest that to enhance the quality of provided care, it is necessary to co-operate with other specialists in the field of dementia care.

Multi-disciplinary care

The third strand of the contributions focuses on the consequences of multi-disciplinary care in long-term care facilities on organisational dimensions, such as the quality of provided care, the integration of the skills of different professionals and the interaction among the involved professional backgrounds.

First, all considered contributions highlight how a multi-disciplinary approach improves the quality of care from various perspectives, focusing mostly on emerging representations in professionals and in relatives. In their survey of professional teams in North-West England (UK), Abendstern et al. (Reference Abendstern, Reilly, Hughes, Venables and Challis2006) underline how multi-disciplinary teams are more suitable than single disciplinary teams for providing person-centred care, reaching a high integration with other services (e.g. general practitioner (GP) services, primary health services and other local dementia agencies) and assessing and tailoring in depth the needs of patients with dementia. The authors do not find particular differences in the capability of continuously involving care-givers in the development of care processes. Similarly, Cleary and Doody (Reference Cleary and Doody2017) explore Irish nurses’ experience in caring for patients with dementia and emphasise how collaboration among professionals with different areas of expertise can be vital for making the ‘right decision’, carefully assessing and supporting the behaviours of people with dementia and, finally, providing person-centred care. Minkman et al. (Reference Minkman, Ligthart and Huijsman2009) report positive reactions by elderly people and their familial care-givers to the quality of received services, particularly in terms of service delays and stress among care-givers. Moreover, in the Netherlands, Zwijsen et al. (Reference Zwijsen, Smalbrugge, Eefsting, Twisk, Gerritsen, Pot and Hertogh2014) show how a multi-disciplinary care programme leads to a decrease in challenging behaviour and in the prescription of psychoactive drugs without an increase in the use of restraints. Thanks to this programme, the focus on care-giving for people with dementia has gradually evolved from a pure disease-oriented view to a more person-centred and tailored approach, reaching a high consensus among professionals. The authors note as a critical point that to achieve the desired effects, the programme has to be adjusted to the daily routine of each nursing home involved in the study, increasing the risk of implementation problems.

Multi-disciplinary teams are generally created to integrate the knowledge and the backgrounds of various professionals. However, multi-disciplinary teams can be characterised by numerous conflicts among different professional cultures. Nonetheless, Amador et al. (Reference Amador, Goodman, Mathie and Nicholson2016) show that when supported by dedicated intervention, in English care homes, professionals with different backgrounds (i.e. staff and visiting health-care practitioners, such as GPs and district nurses) have developed a shared social identity rooted in common values and goals in the field of dementia care. For example, end-of-life management is particularly crucial for all involved professionals who (through continuous meetings) construct a common strategy for caring for residents and interacting with family members. Moreover, this study shows that by sharing common goals and values, health-care professionals with different backgrounds can find innovative solutions for improving care processes. The fragmentation of dementia care services can also be overcome with the support of specific co-ordinators. In a qualitative study conducted in the Netherlands, Minkman et al. (Reference Minkman, Ligthart and Huijsman2009) show that case managers can play a crucial role in connecting different health-care organisations, such as nursing homes, mental health services, Alzheimer associations and patient associations. The authors report that in the face of the increasing numbers of elderly people with dementia, case managers carry out the following activities that are vital for providing client-tailored services: care assessment, care planning, co-ordination of tasks, implementation and evaluation of programmes, and emotional and practical support for patients and their relatives. In this framework, case managers are professionals who should assure continuity among different spheres of care (i.e. primary, specialty, mental and long-term health care).

Discussion

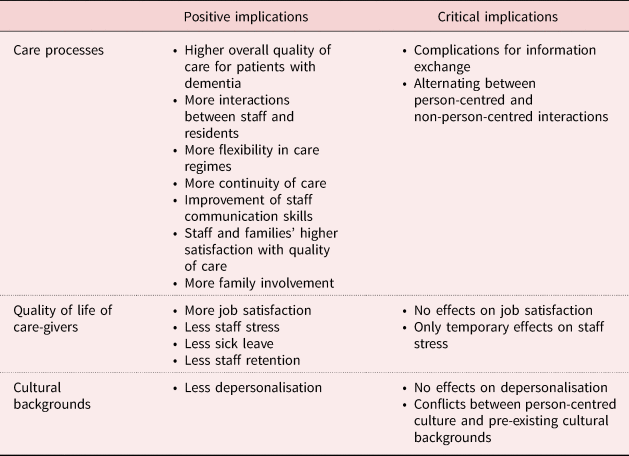

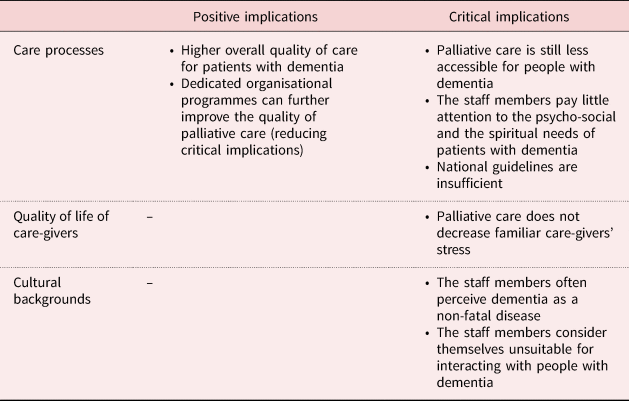

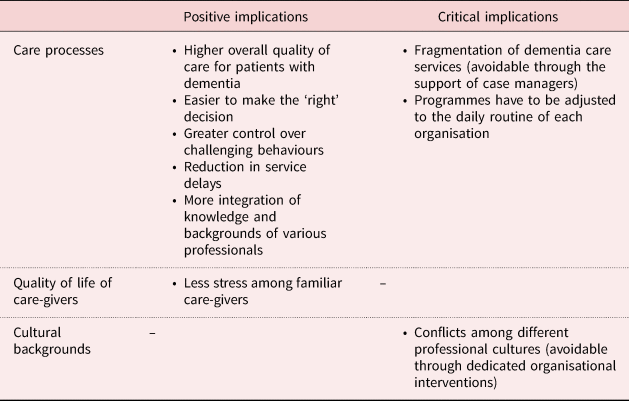

Over the last decades, an inter-disciplinary debate has emerged around dementia care, providing theoretical and practical tools that are useful for overcoming the standard medical approach and the so-called malignant social psychology. In our work, we have focused on three SCIs (i.e. person-centred, palliative and multi-disciplinary care) that play a key role in assisting people with dementia and their relatives during the illness trajectory (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Lloyd-Williams and Sachs2009). In particular, we have conducted a literature review with the aim of exploring the positive and critical implications of the implementation of SCIs for long-term care organisations. Our analysis points out that each SCI has consequences for care processes, the quality of life of care-givers and cultural backgrounds. This detailed analysis (summarised in Tables 3–5) leads to three main considerations concerning the implications of SCIs for long-term care organisations.

Table 3. Person-centred care and organisational implications

Table 4. Palliative care and organisational implications

Table 5. Multi-disciplinary care and organisational implications

First, a still limited number of contributions explore the conflict dynamics between SCIs and pre-existing cultural backgrounds, intended as values and beliefs that provide norms of expected behaviours that people might follow (Schein, Reference Schein1991). The beliefs concerning dementia (e.g. as an illness that causes the loss of personhood and/or that is less painful than other degenerative diseases) underpin the behaviours that can obstruct the introduction of a new practice (e.g. not providing palliative care to residents with dementia) or change the course of its implementation (e.g. producing a care process in which person-centred care is interwoven with standard medical care). In the case of multi-disciplinary teamwork, the implementation of the new interventions is obstructed by the existing discrepancies among the involved professional cultures; each profession is characterised by a well-defined identity and values that can prevent inter-disciplinary co-operation (Hall, Reference Hall2005). Therefore, pre-existing cultural backgrounds seem to affect the implementation of SCIs, leading to unexpected and unwanted results. If the ‘betrayal’ of an innovative idea is well known in organisation studies (Czarniawska-Joerges and Sevón, Reference Czarniawska-Joerges and Sevón2005), in this case, it prevents, at least partially, the improvement of the wellbeing of the members of the considered organisations.

Second, for supporting the changes in care processes and cultural backgrounds, several works underline the importance of advanced training programmes. Most of the person-centred care literature focuses on person-centred models that have been flanked by training programmes addressed to personnel, with particular reference to nursing home staff. The growing attention paid by international and national institutions to the dementia-related knowledge gaps (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bagley, Reilly, Burns and Challis2008) seems to be followed by specific organisational programmes directed to the workforce. Probably also for this reason, the implementation of person-centred care practices seems to have several positive implications in long-term care facilities. Although some studies (Doyle and Rubinstein, Reference Doyle and Rubinstein2013; Viau-Guay et al., Reference Viau-Guay, Bellemare, Feillou, Trudel, Desrosiers and Robitaille2013) emphasise that the cultural backgrounds underpinning the actions of professionals seem to incorporate new and old beliefs about dementia, this mixture does not appear to prevent a substantial shift in care processes and care-givers’ quality of life. In the other considered SCIs, the educational programmes remain rare. In particular, the lack of education for staff in palliative care, previously revealed by various works (e.g. Chang et al., Reference Chang, Hancock, Harrison, Daly, Johnson, Easterbrook, Noel, Luhr-Taylor and Davidson2005), seems to have serious negative consequences on the quality of care that is often low due to the lack of attention to both physical and non-physical needs of people with dementia.

Finally, a methodological consideration is needed. The dominance of quantitative studies has influenced the results of our review, at least in two ways. On one hand, more attention is paid to the outputs of the implementation of SCIs than to the ways in which the new care models are implemented. Consequently, the reasons that underpin the success or the failure of the implementation processes are often under-investigated. For example, although the key role of cultural backgrounds in either facilitating or obstructing health-care innovations is well known (Carrieri et al., Reference Carrieri, Peccatori and Boniolo2018), in the considered literature, the attention paid to this aspect is still limited. On the other hand, the emerging results of the selected studies are often strictly connected to the expectations of the authors and of the designers of the considered innovations. Tools such as validated scales are chosen with the aim of measuring the degree to which the expected effects have been achieved, and other kinds of outcomes are rarely considered (e.g. in the literature concerning palliative care, the consequences on formal care-givers’ stress have not been taken into consideration). A greater usage of qualitative techniques (and in particular, of ethnography and unstructured interviews) could increase the focus on the unexpected effects of new care interventions.

Implications for practice and science

The current review leads to a better understanding of the organisational implications derived from the implementation of person-centred, palliative and multi-disciplinary care. As explained above, we have chosen these interventions because they have been previously indicated as care approaches that play a key role in guaranteeing the holistic wellbeing of people with dementia and their relatives. In particular, our work underlines the positive effects of SCIs on organisations and care-givers, at the same time focusing on the critical implications related to the introduction of the considered care interventions. In our opinion, this study provides an actual overview that can be useful for managers and health-care professionals employed in organisations that are considering whether or not to implement these interventions. Moreover, the knowledge established in this review can be used by long-term care facility managers for planning the implementation of SCIs in their organisations and for facing the possible emerging challenges (e.g. defining training courses for the staff to change the pre-existing cultural assumptions about dementia and palliative care).

Our work also highlights the knowledge gaps in current research about SCIs and organisational implications. First, our work points out that the literature about person-centred care in long-term care organisations is much more developed than the studies on other care approaches. There are multiple reasons for these differences. On one hand, the advancement of research concerning the organisational implications of palliative care has often been limited by complex ethical issues (Sampson, Reference Sampson2010) and by the high degree of attention paid to clinical outcomes (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Ritchie, Lai, Raven and Blanchard2005; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Dickinson, Rousseau, Beyer, Clark, Hughes, Howel and Exley2012). On the other hand, in the case of multi-disciplinary care, the literature has paid more attention to community care programmes than to interventions carried out in long-term organisations (Thomas, Reference Thomas2010; Bieber et al., Reference Bieber, Stephan, Verbeek, Verhey, Kerpershoek, Wolfs, de Vugt, Woods, Røsvik, Selbaek, Sjölund, Wimo, Hopper, Irving, Marques, Gonçalves-Pereira, Portolani, Zanetti and Sjölund2018). Second, in the debates about palliative care and multi-disciplinary care, more attention is needed regarding the quality of life of formal care-givers. For example, in cancer care, staff stress in a multi-disciplinary team (Ekedahl and Wengström, Reference Ekedahl and Wengström2008) and in palliative care (Vachon, Reference Vachon1999; Dougherty et al., Reference Dougherty, Pierce, Ma, Panzarella, Rodin and Zimmermann2009; Pfaff and Markaki, Reference Pfaff and Markaki2017) has been analysed in depth. Third, as already highlighted, it is necessary to focus on the interaction between organisational and professional cultural backgrounds and new interventions.