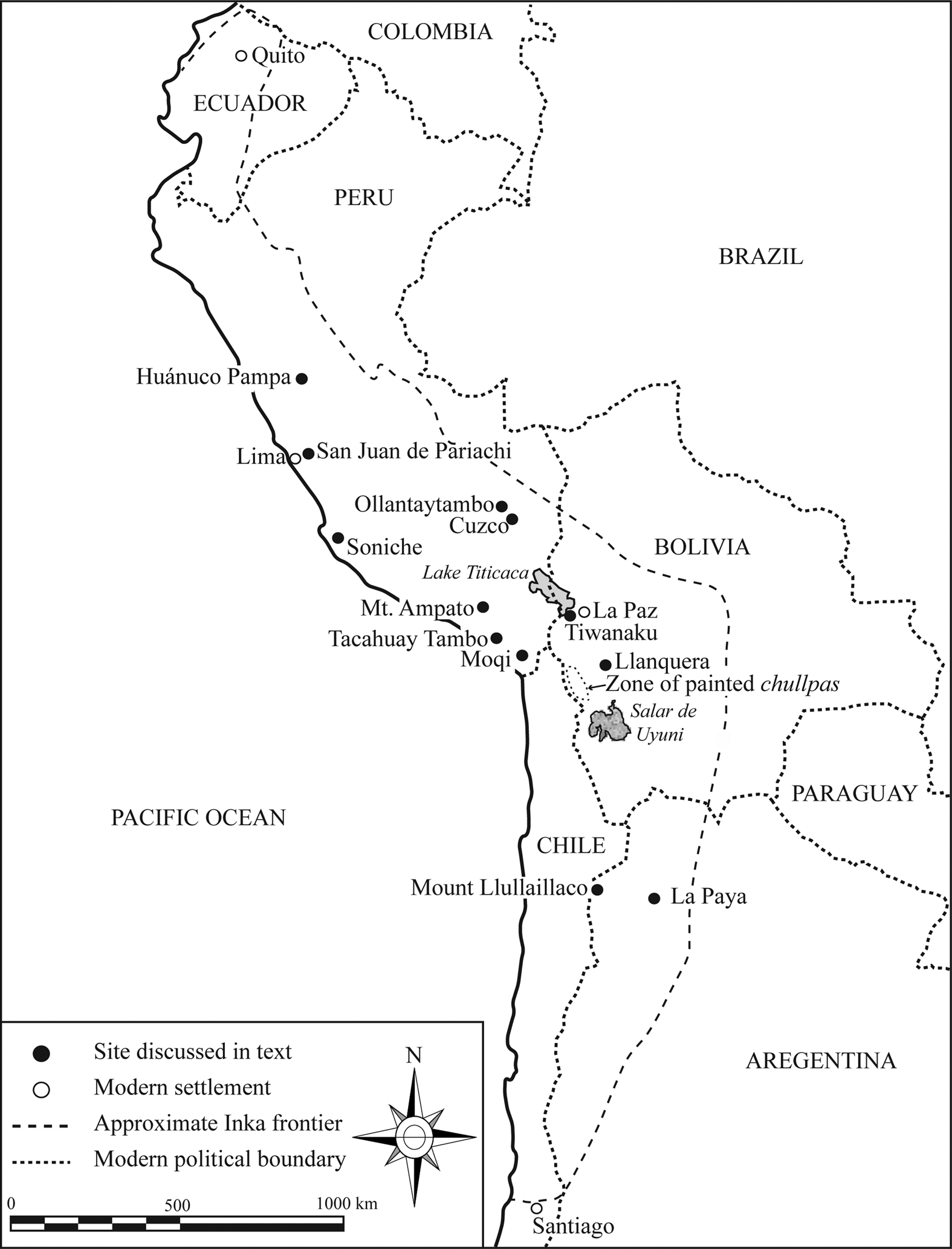

Pairs of wooden drinking vessels, known as queros,Footnote 1 were a physical manifestation of Inka diplomacy in the provinces of their Andean empire (Late Horizon, AD 1400–1532; Figure 1). Produced by imperial craftsmen, matched sets of geometrically incised queros played a fundamental role in reciprocal toasting between Inka representatives and the leaders of newly incorporated communities. This act sealed the amalgamation of local people into the empire and their acquiescence to the state's expectations of labor service. The pairs of wooden drinking cups were then left with the local community and brought out during subsequent state-sponsored hospitality events to reaffirm the relationships of obligation and reciprocity between empire and subjects.

Figure 1. The Inka Empire, with sites mentioned in the text.

These interpretations take as their starting point the imperial perspective, highlighting how the Inka used queros to co-opt traditional Andean norms of reciprocity and long-standing toasting rites to naturalize the new asymmetric labor relations between the empire and the peoples of the provinces. Yet there has been little consideration of how these pairs of wooden vessels—which remained with subject communities even when Inka representatives were absent—were valued and used by provincial peoples themselves.

In pursuing this perspective, I argue that Inka queros can be best understood as inalienable objects (Weiner Reference Weiner1985, Reference Weiner1992). Unlike tradable commodities or other forms of material wealth, the value of inalienable goods derives from the fact that they are indelibly imbued with the social and political identity of the giver. They are objects of memory, embodying in this case the history of the relationship between the imperial source and the recipient and, through them, the community as a whole. Use and display of these objects could promote the personal authority of an individual leader by linking him or her with a powerful empire. In other cases, such objects may have played a role in developing a shared identity for the broader community as they navigated the new political landscape of the Inka Empire. This view of Inka queros focuses on how the value of an object is constituted through social relationships. It furthermore sheds light on how incorporated communities were active recipients and manipulators of imperial material culture and, ultimately, co-creators of Inka rule.

I begin by discussing the concept of inalienability and how it can be recognized archaeologically. I go on to illustrate the inalienable nature of Inka queros using ethnohistorical and archaeological information on their uses and production, as well as where they have been found archaeologically. Given the special nature of these vessels, they most often enter the archaeological record as part of formalized ritual deposits. I draw a distinction between queros found in mortuary contexts, which served to highlight the connections between the empire and an individual leader or kinship group, and those recovered from non-mortuary ritual deposits that commemorated aspects of local–imperial relations relevant to the community as a whole. The contexts where queros have been found archaeologically thus provide critical insight into how provincial peoples used them—with their undeniably Inka style and the political entailments they bore—to materialize relationships both within the local settlement and between the community and the empire.

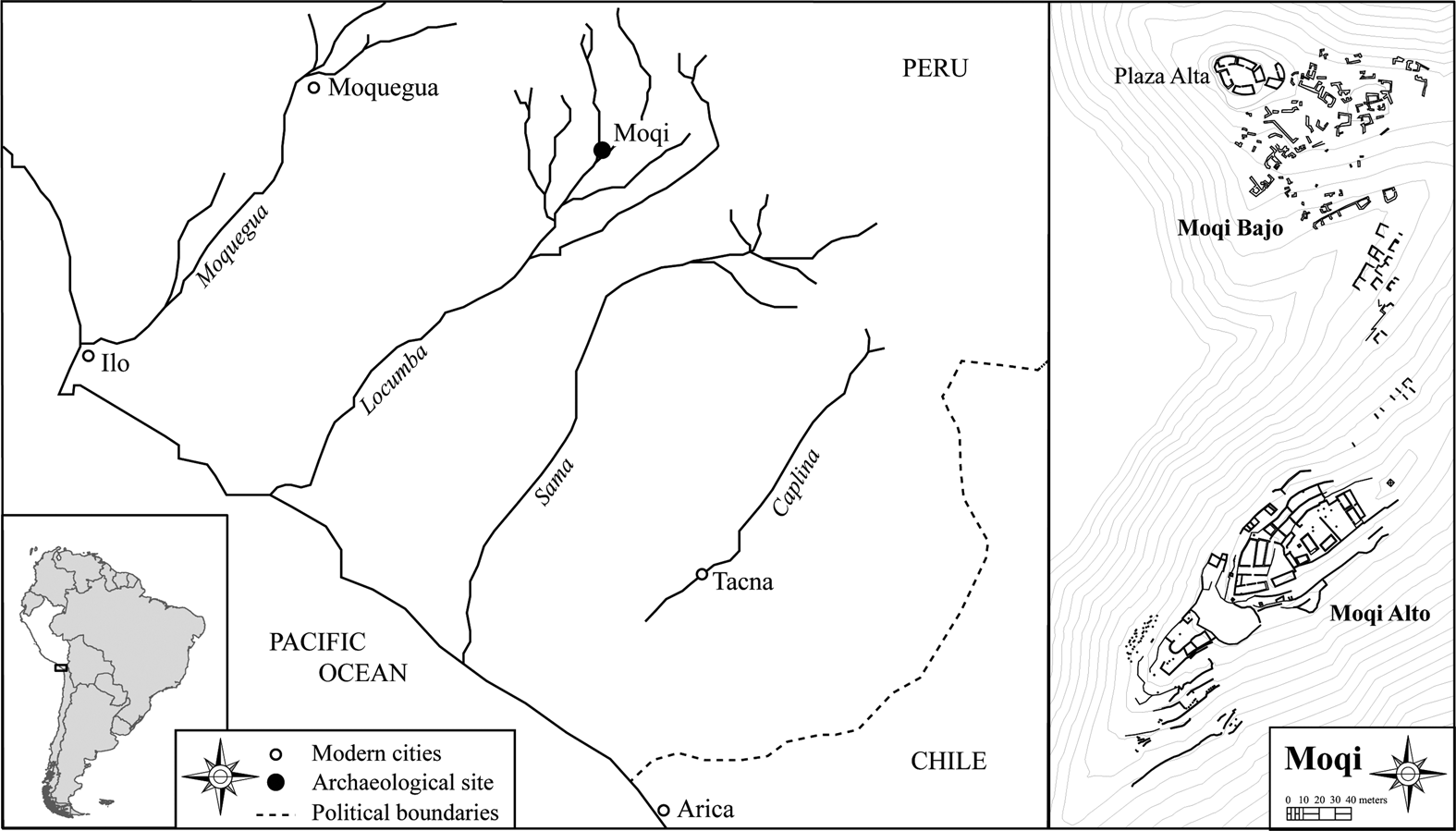

I then present a case study from the Inka administrative site of Moqi, located in the upper Locumba Valley of southern Peru (Figure 2). In addition to pairs of queros recovered from Late Horizon tombs, two queros were deposited singly in distinct stages of a closing ritual terminating the use of a building and of the site itself. In this community, brought together at the behest of the empire in a newly established settlement, Inka queros do not appear to have been a symbol of personal authority or prestige for local leaders. Instead, drawing on the concept of inalienability, I argue that inhabitants of Moqi may have looked to queros as symbols of a new and shared political identity within the Inka world order and as materializations of the relationship between the empire and the community as a whole.

Figure 2. Left: Moqi's location in the Locumba Valley. Right: the architectural layout showing the Inka sector of Moqi Alto and the local sector of Moqi Bajo (redrawn from map created by Hans Barnard).

Recognizing Inalienability in the Past

“Inalienability” is culturally constituted and highly dependent on context but can be attributed to objects sharing a range of features. These features were identified by Annette Weiner in her ethnographic work in Oceania (Reference Weiner1985, Reference Weiner1992). They have been operationalized in a variety of anthropological and archaeological case studies that attribute inalienability to specific objects, ceremonial paraphernalia, human bones, ritual knowledge, architecture both monumental and quotidian, improved land, and domesticated animals (Aswani and Sheppard Reference Aswani and Sheppard2003; Curasi et al. Reference Curasi, Price and Arnold2004; Flad and Hruby Reference Flad and Hruby2007; Hendon Reference Hendon2000; Kovacevich and Callaghan Reference Kovacevich and Callaghan2014; Lesure Reference Lesure and Robb1999; Mills Reference Mills2004; Orton Reference Orton2010; Rice Reference Rice2009a). The recovery context, coupled with insights from ethnographic comparisons and ethnohistorical sources, is key to recognizing inalienability in the archaeological record.

Whether and how an object moves through society are core features of inalienability. Inalienable goods do not circulate through typical exchange networks like commodities and are not subject to what Mills (Reference Mills2004:240) calls “mundane exchange transactions.” In contrast to commodities, which are desired for their use-value and can be easily passed between individuals, ownership of inalienable objects cannot be transferred: these objects may be possessed, but they cannot be owned. This is because they are perceived as remaining attached to—and even representative of—their original owners, even when they circulate among other people (see Strathern's concept of enchainment [Reference Strathern1988]). Inalienable objects thus serve as objects of memory, embodying the history of giving and receiving in which they have been involved.

How an object is produced can imbue attributes of inalienability. Such objects often require specialized knowledge in their production, or only certain individuals might have the right to produce them (Mills Reference Mills2004; Rice Reference Rice2009b; Weiner Reference Weiner1992). They might incorporate rare, nonlocal, or difficult-to-work materials, which also contribute to an object's value (Helms Reference Helms1993). Typically made in small numbers and then further distinguished by the specific histories that they accrue, these objects were what Weiner (Reference Weiner1992) called “singularities.” In some cases, however, larger numbers of like-objects or replicas may be produced (Callaghan Reference Callaghan2014; Kovacevich Reference Kovacevich2014:98–99). These objects reference the more precious inalienable versions but circulate more widely. As argued by Wattenmaker (Reference Wattenmaker and Brumfiel1994; cited in Kovacevich Reference Kovacevich2014), these like-objects create recognition of and demand for prestige goods on the part of non-elites, and ownership of such objects may be used to advance social standing (see Han et al. Reference Han, Nunes and Drèze2010).

Inalienable objects play a critical role in forging and displaying social identities. They link their possessors to the past and serve as vehicles to legitimize identities and authority in the present (Weiner Reference Weiner1992). Claims to relationships, resources, or knowledge authenticated by possession of a specific object can serve as a mechanism for individual aggrandizement. In her study of inalienable ritual paraphernalia in Zuni history and prehistory, Mills (Reference Mills2004) found that objects reflecting on a single person—such as clothing and wooden staffs of office—could be passed down through generations but were eventually placed into the tombs of individuals.

In other cases, inalienable objects can play a role in counteracting hierarchies. This can occur when inalienable objects are used to promote communal identities, rather than the individual persona and economic interests of a particular leader (Mills Reference Mills2004:240). For the Zuni, objects used by groups in collective ritual activities—such as altars and their associated furniture—were never found in individual burials. Instead, these symbols of shared community identity and practice were found only in cave deposits and ritual storage rooms.

Recognizing inalienability in the archaeological record relies on establishing that a specific object or class of objects has been made, used, or deposited into the archaeological record in ways distinct from more quotidian items. Such objects often enter the archaeological record in performed acts of ritual deposition, recognizable because they are framed or intentionally set apart from typical daily practice (see Verhoeven Reference Verhoeven2002:Table 1). The concept of ritual bundling has utility here because it “captures the condensation of particular assemblages of artifacts that were consciously emplaced in the archaeological record” (Swenson Reference Swenson2015:335). Pauketat (Reference Pauketat2013:27) uses the metaphor of a bundle to encompass combinations of things and places that “form nodes in a larger field or web of relationships where material and metaphorical relations and associations articulate with one another.” These attributes of inalienability might be inferred when the context and content of distinctive deposits are redundant and repeated, observed in multiple instances within or between sites (Mills Reference Mills2004, Reference Mills2014). Patterned deposition indicates an underlying cultural logic of valuation attributed to such items and suggests that retention or deposition may have been governed by a shared sense of what the object meant and how it functioned within society. As suggested by Mills's work on the Zuni (Reference Mills2004), inclusion within a tomb may signify that an inalienable object authenticated individual authority, whereas deposition in a ritualized space not specifically owned or associated with a single person may indicate that an inalienable object is perceived as representative of the broader community.

Table 1. Context and Formal Characteristics of Wooden Queros Recovered Archaeologically from Moqi.

Notes: All measurements are in centimeters. Indet. = Indeterminate.

Inka Queros as Inalienable Objects

The Inka made drinking vessels from wood, clay, and metals, such as gold and silver; these last were called aquilla. Here, I focus on those known as queros, defined in early Spanish-Quechua dictionaries as a “vaso de madera” (cup of wood; e.g., Santo Tomás Reference Santo Tomás1951 [1560]; Ziółkowski Reference Ziółkowski, Alconini and Alan Covey2018:271–72). Inka queros have two primary shapes: one is narrowest at the base with straight sides that angle outward, and a waisted one draws in at the middle, with somewhat wider bases and rims. There is no evidence that these styles reflect differences in origin or period of production (Cummins Reference Cummins2002:25). Albeit with some variation, Inka queros are similar in size: more than two-thirds are between 14 and 17 cm in height.

Although queros are beautifully crafted examples of Inka woodworking, I suggest that the social value of these vessels was predicated principally on their inalienable nature. Queros share many of the attributes of inalienable objects discussed in the previous section. I begin with a discussion of how they were produced. I then examine their significance and what they meant during Inka times and, finally, how they entered the archaeological record.

Inka Quero Production

Inka queros were produced by specialists and embellished with abstract geometric decorations that overtly manifested Inka artistic style and even may have encoded references to Inka history, ideology, and imperial practice. These features are consistent with the inalienability of these vessels and with their use in sealing and reproducing relationships between the empire and the peoples of the provinces.

The uniformity in form, materials, and decoration displayed by the corpus of Inka period queros attests to state oversight of their production. Colonial-era tax surveys (visitas) suggest that they were produced in the provinces by specialists living either in their own villages or in dedicated woodworking enclaves and supported by the Inka state (Cummins Reference Cummins2002:25; Levine Reference Levine1987). Woodworkers were drawn from regions with suitable trees and strong woodworking traditions. For instance, in the labor service assessed for the Chupachu, an ethnic group inhabiting the heavily wooded Huallaga Valley, 40 (of 4,000) individuals were required for woodworking and were recorded in 6 of the 15 artisan settlements visited by the inspector (Levine Reference Levine1987:30). By contrast, none of the labor assessed for the Wanka—who inhabited a less wooded region of the central Peruvian sierra—was devoted to woodworking (Levine Reference Levine1987:30).

Given their important role in enacting social relationships through mutual toasting and commensal consumption, it is unsurprising that queros were produced as pairs, each the same size and bearing the same decoration as its mate (Cummins Reference Cummins2002:25, Reference Cummins, Burger, Morris and Mendieta2007:273).Footnote 2 The pairs were even carved from the same block of wood (Kaplan et al. Reference Kaplan, Ellen Pearlstein and Levinson1999). They were produced from various kinds of wood, including Prosopis sp., Escallonia resinosa, and Polylepis sp. (Capriles and Flores Bedregal Reference Capriles and Bedregal2002; Kaplan et al. Reference Kaplan, Ellen Pearlstein and Levinson1999). Although these differences likely represent local wood availability, sometimes the wood used to produce queros was not from the immediate region. Analysis of two Argentinian queros found at the arid sierra site of La Paya indicates that they were produced from Erthrina sp. wood, found in tropical and subtropical regions of the eastern Andes (Sprovieri and Rivera Reference Sprovieri and Rivera2016).

Members of a pair of Inka queros were decorated with matching abstract and repetitive geometric designs created by incising thin lines into the wood of the vessel. Common design elements include concentric squares or rectangles, chevrons, diamonds, zigzag bands, crisscrossing diagonal lines forming Xs, and rows of vertical or horizontal lines. Some elements may have had parallels in Inka tocapus (Lizárraga Ibánez Reference Lizárraga Ibánez2009; Ziółkowski Reference Ziółkowski, Alconini and Alan Covey2018): square icons with abstract and standardized geometric designs found on cloth, pottery, and queros that appear to have referenced symbols or aspects of Inka imperial power. For instance, a motif consisting of a rhomboid with five dots arranged in a cross in the interior signified the cave at Pacaritambo from which the original Inka emerged (Cummins Reference Cummins2002:note 69). The “Inka key” design may have symbolized the layout of the empire into the four divisions of TawantinsuyuFootnote 3 (Frame Reference Frame2010); alternatively, it may reference disarticulated heads and arms associated with the Inkas’ suppression of rebellions (Cummins Reference Cummins, Burger, Morris and Mendieta2007:279). One of the most common designs found on queros is a series of concentric squares, rectangles, or diamonds. Concentricity is a common feature in Inka art (McEwan Reference McEwan, Meddens, Willis, McEwan and Branch2014) and references the hierarchical nesting that characterized the state's political structure (Frame Reference Frame2010). For provincial subjects, a more familiar referent for these concentric tocapus may have been the tiered platforms of Inka ushnus, tangible symbols of Inka authority found in the plazas of administrative centers.

According to Cummins, “The regularity of Inca queros is in keeping with the Inca creation of a unified visual and material culture to be experienced throughout the administrative and ritual centers of Tahuantinsuyu. Visual uniformity, intensified by abstraction, certainly can be understood as an exercise of Inka political power on culture” (Reference Cummins2002:26). The abstract geometric designs provided visual references to other types of Inka vessels commonly bestowed on local communities, such as the aribola used in carrying and serving chicha, or corn beer. Simple but visually impactful and laden with symbolic meanings, the geometric imagery of Inka wares used in feasting linked the vessels, communities, and imperial representatives into a greater political whole, enacted through toasting.

The Inka Use of Queros

In the Inka Empire, the quero “had no commodity value. It was made to be used to effect a sociopolitical discourse that was carried out through ritual actions” (Cummins Reference Cummins2002:37). This discourse was multifaceted and mutually reinforcing. Queros were symbols of cosmological legitimacy for the Inka. They served as a focal point in the process of imperial incorporation and in reaffirming ongoing political relationships once the initial conquest was over. As such, they were a linchpin of economic interactions between the empire and local communities.

Queros were deeply intertwined in the projection of Inka legitimacy and right to rule. Inka myths linked the origins of the cosmos and the peopling of the world by the primary creator deity Viracocha to the site of Tiwanaku, capital of the eponymous Tiwanaku culture (AD 550–1000; Figure 1). Although the site was already a ruin in Inka times, monumental statues of individuals bearing queros are found throughout it. As noted by Cummins, “The quero had a preeminent role in Tiahuanaco's material culture. A similar importance in Inca culture cannot be coincidental in light of the importance that the Inca accorded to Tiahuanaco” (Reference Cummins2002:62–63; see also Beaule Reference Beaule, Mander, Midgley and Beaule2020).

In addition to referencing cosmic origins, the cups served as a reminder of the emperor's divinity and authority. A set of cups was among the emblematic symbols of the imperial sovereign given to the progenitors of the Inka by Viracocha. These symbols, marking divine approbation of the Inka right to rule, included the red woolen fringe worn as a crown, a staff with a pickaxe-shaped metal headpiece, and a set of golden cups used for toasting (Cummins Reference Cummins2002:74–76). The first two symbols represented the military might and power of the empire, whereas the cups, along with the chicha served in them, symbolized the emperor's ability to bring peace and agricultural fertility.

Queros were integral to how the Inka initiated the incorporation of new lands (Betanzos Reference Betanzos1987 [1551]:72–73). Arriving with the army at his back, the Inka would begin not by attacking, but by negotiating with local leaders (curacas). If these leaders submitted without resistance, the Inka bestowed gifts—most often, pairs of cups and fine cloth from Cuzco. If the curacas did not accede to the Inka's demands, the army would unleash destruction on them. New diplomatic relationships were sealed by mutual toasting, a tradition with deep roots in the Andes. Accepting the queros and cloth “initiated a cycle of obligatory ‘reciprocity’ by which the new territory symbolically entered, on an unequal basis, into the redistributive economy of Tawantinsuyu” (Cummins Reference Cummins, Burger, Morris and Mendieta2007:277). The cups remained in the local community; ethnohistoric documents suggest that they were kept in a special building or temple built at the behest of the Inka and commemorating the treaty that had been sworn (Cummins Reference Cummins2002:86).

Once relations had been established, ritual toasting using queros was an important vehicle for reaffirming political affiliations with provincial leaders. During the festival of Inti Raymi, the celebration of the winter solstice, local leaders accompanied the state's portion of the harvest to Cuzco or other provincial centers and joined in multiple days of feasting and celebration with the Inka. Position in the imperial hierarchy was symbolized by the sequence in which one was toasted, as well as the material from which were made the cups used to serve the chicha (Cummins Reference Cummins2002:107–108). Ethnohistoric documents indicate that distinguished military captains were toasted first, followed by leaders from the heartland region considered “Inka-by-privilege,” and finally curacas from the provinces. Within the Inka system of decimal administration, golden queros were given to leaders of 10,000 households, silver to leaders of 1,000 households, and wooden ones to leaders in charge of 100 households. Relations between local leaders and the Inka were reinforced and upheld on an ongoing basis through commensal feasting events held in the provinces and then were renegotiated after transfers of power on the death of either party.

Queros were vital paraphernalia in feasting rituals that constituted the engine of the Inka imperial economy. In the non-monetized world of the prehistoric Andes, reciprocity was the primary mode of economic interaction. Conditional relationships between local leaders and their communities had long been symbolized in feasts, in which the exchange of food and toasts of chicha “signified that the curacas acknowledged the services they had received from the community. In return, the community recognized the curacas’ authority to oversee ritual ceremonies, coordinate communal tasks, and redistribute land and resources” (Cummins Reference Cummins2002:42; see also Jennings and Bowser Reference Jennings, Bowser, Jennings and Bowser2008; Murra Reference Murra1980). As they expanded outside of their Cuzco basin heartland, the Inka normalized the transfer of economic resources through appropriation of these long-standing feasting traditions. Local subjects performed their labor service for the state and were reciprocated through feasting and the provisioning of alcohol served in queros. These feasts maintained the semblance of customary reciprocity, even though they were conducted from a position of absolute, rather than conditional, authority. Feasts were an arena to establish social relationships between the Inka Empire and its provincial subjects, simultaneously uniting people under a single imperial identity and instituting hierarchical relationships between the participants.

Inka Queros in the Archaeological Record

Because they act as repositories of social memory and conduits for constituting and reaffirming interpersonal relationships, inalienable objects rarely enter the archaeological record. When they do, they are almost invariably found in what can be considered performatively bundled deposits. Many wooden queros from the Inka period reside in museum collections, and we unfortunately have little precise information regarding their provenience. What we do know, however, supports their designation as inalienable objects. The majority of Inka queros have been recovered from mortuary contexts associated with a single individual or sometimes a family or kinship group. A small number of single queros have been found in contexts indicative of ritual activities but that were not burials.

Queros in Mortuary Contexts

Tombs are a quintessential example of performative ritual bundling, and Inka queros have been recovered from a variety of mortuary contexts. We can draw a distinction between those included as offerings in the graves of individuals and those that were part of a broader funerary ritual for a family or kinship group but that were not associated with a specific person. Finally, there are additional examples in which queros were included in burial contexts that were the product of strong state involvement—specifically, in rituals of state-directed human sacrifice (capacocha or capac hucha)—in which the queros may have been less an inalienable object associated with the deceased individual but instead were included to symbolize important aspects of the state.

Political relationships in the Inka Empire entailed a highly personal connection between provincial community leaders and agents of the empire, if not the emperor himself. These relationships had to be renegotiated on the death of the Inka emperor or the local representative. In Late Horizon provincial cemeteries, queros are typically found in tombs that are comparatively rich in Inka-style goods, suggesting that these vessels were among objects representing the individual's social and political identification with the empire and the power derived therefrom. Indelibly emblematic of the relationship between a specific individual and the Inka, the queros and both the obligations and the power that they entailed could not be transferred automatically to a living representative. Bringing the relationship to a close and opening the door to renegotiation with a successor required that the queros be bundled with the deceased in the burial ritual.

Burial Tk at the Soniche cemetery in the Ica Valley is an excellent example of queros ritually bundled with other accoutrements of a single individual. This tomb contained a female individual of 25+ years who was buried with 26 Inka-style ceramic vessels, three knotted string devices (khipu) used for record keeping, and a pair of wooden queros (Menzel Reference Menzel1976:229–231; Rowe Reference Rowe and Lathrop1961:323). Significantly, this individual was not the highest-status person buried in the cemetery but was the only one interred with such a large quantity of imperial-style artifacts. A similar situation has been encountered in northwestern Argentina, where burials at the Calchaquí Valley site of La Paya yielded numerous queros (Ambrosetti Reference Ambrosetti1907). Several were found in a high-status interment beneath the floor of the Casa Morada, a building of Inka-style architecture where local elite resided (Acuto Reference Acuto, Malpass and Alconini2010). In both the Ica and Calchaquí Valley examples, the queros were integral to a bundle of objects materializing the individual's social and political identification with the Inka Empire. They embodied the relational networks with the empire that had been initiated and maintained through toasting. Because the relationships entailed in these matching queros could not be reassigned to another individual simply by transferring possession of them, the pair of vessels was interred with the person originally forging those bonds.

The association between tombs and queros was important in the Inka heartland, as well as the provinces. A tomb at the Sacred Valley site of Ollantaytambo contained three matched pairs of queros in different styles (Rowe Reference Rowe and Lathrop1961:319–323).Footnote 4 Most scholars agree that the Ollantaytambo tomb probably dates to 1537, when Manco Inka used the site as a refuge after failing to retake Cuzco from Spanish forces and before withdrawing to Vilcabamba (Cummins Reference Cummins2002; Rowe Reference Rowe and Lathrop1961). Even as the Inka Empire was in crisis, representation of ties between an individual and the state saw commemoration in the mortuary ritual.

Queros are frequently found in association with Late Horizon chullpas: aboveground burial towers made of stone or adobe and housing lineages or family groups.Footnote 5 For example, 15 queros were recovered from an intact chullpa at the site of Tacahuay Tambo on the southern Peruvian coast (Sofía Chacaltana, personal communication 2013). The chullpa contained the remains of at least 32 individuals, including infants, children, and males and females of various ages. Queros have also been found in chullpas throughout the Bolivian altiplano (D'Orbigny Reference D'Orbigny1944 [1839]:1421–1422; Nordenskiöld Reference Nordenskiöld1931:96; Posnansky Reference Posnansky1931:95). Because chullpas are typically used for multiple interments, it is difficult to determine whether they were offerings associated with a single individual (and if so, which tomb occupant) or were tied to the entire lineage.

In another case, the association between queros and a broader lineage or social group—rather than a single individual—appears more clear-cut: when they are found adorning the exteriors of these collective burial towers. This phenomenon has been observed primarily in the altiplano south of Lake Titicaca, although it takes various forms. Rows of niches located above the entrances to adobe chullpas south of La Paz, Bolivia, at sites such as Llanquera, contained fragments of wooden queros (Michel López Reference Michel López2000; Ponce Reference Ponce Sanginés1993). This implies that the queros saw prolonged use in toasting the dead and celebrating the ancestors, practices well represented in colonial images and documents (Gil García Reference Gil García2010; Ochoa et al Reference Ochoa, Kuon and Argumedo1998). In other examples, the queros were inlaid directly in the walls of the chullpas. Chullpas in western Bolivia, such as found at the sites of Sajama and Macaya, prominently display queros inlaid above the lintels of the doorways, where they generally occur in multiples of two (Gisbert et al. Reference Gisbert, Jemio and Montero1994:441). It is significant that these tombs are among a corpus of painted chullpas (see Figure 1) that replicate distinctive Inka geometric patterns often seen in textiles. These tombs may have been “identified with the Aymara lords (mallcus) who had accepted Inka rule and who were buried in the structures. The abstract design may have signified, among other things, the political alliance that had been historically forged between the Inka and the ancestors placed within” (Cummins Reference Cummins, Burger, Morris and Mendieta2007:285). Although they are a symbol of a single leader's alliance with the empire, queros embedded in the wall of the lineage tomb made a statement affirming the allegiance of the entire family group and authenticating the authority derived from those associations.

Not all queros included in mortuary contexts had the same meaning. This is exemplified by those recovered from interments shaped directly by the state, such as capacocha or capac hucha sacrifices at sacred sites, usually atop mountains. These sacrifices typically include one or more young girls and boys and often also a young woman in her mid-teens. Pairs of queros are usually associated with the female individuals (e.g., Mt. Llullaillaco in Argentina [Ceruti Reference Ceruti2004; Ceruti and Reinhard Reference Ceruti and Reinhard2005], although sometimes they are found with the male children (e.g., Mt. Ampato in Peru [Reinhard Reference Reinhard1996:42–43]). Ceruti (Reference Ceruti2004:118) notes that in Inka capacochas, “it is likely that the pairing of the plates and vessels was related to the Andean etiquette of ritually sharing food and drink. This is especially the case with ritual drinking.” Offerings of food and drink, including the vessels from which they were consumed, were an attempt to establish and perpetuate favorable relationships with the animate landscape, which was responsible for controlling weather, providing water, and ensuring agricultural fertility (Reinhard Reference Reinhard1985). Given the young age of the individuals chosen for the sacrifices, it is unlikely that the queros had the same meaning as those presented to leaders of local communities to seal imperial incorporation. Instead, they were part of a selected corpus of vessels tightly bound to Inka identity and the image the state meant to project into the numinous world of the ancestors and deities—one that emphasized Inka generosity, reciprocity, and hopes for fertility.

Single Queros Found in Ritual Contexts

There are fewer published examples of queros found outside of mortuary contexts. What is unique about the few known instances is that these queros are always found singly—rather than as a pair—and the context can often be described as highly ritualized in nature.

One example comes from the Inka site of San Juan de Pariachi, on Peru's central coast (see Figure 1). There, a single surface-incised Inka quero had been deposited into the floor of a room associated with a stepped platform, or ushnu (Luis Felipe Villacorta, personal communication 2014; Villacorta Reference Villacorta2004). The vessel was found standing upright and had been surrounded and sealed with mud before a new floor was put into place. Several other offerings had been cut through the floor in the same room, indicating that this structure was the locus of repeated ritual events focused on the interment of important ceremonial objects.

A second example comes from the Inka administrative center of Huánuco Pampa, located in Peru's central sierras (see Figure 1). An administrative palace, with plazas used for the commensal consumption of food and drink, was identified on the eastern side of the site's massive central plaza (Figure 3; Morris Reference Morris, Evans and Pillsbury2004; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Alan Covey and Stein2011). In one of the doorways to a rectangular structure on the northwest side of Plaza IIB-2a, excavators encountered a well-constructed, slate-lined subterranean box with an offering of three complete Inka vessels related to chicha production. The overall ceramic assemblage from the building, dominated by cooking vessels and jars, is consistent with chicha production and perhaps storage (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Alan Covey and Stein2011). Immediately adjacent to the subterranean offering was a concentration of decorated pottery, a deer antler, and a well-preserved wooden quero (Figure 3; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Alan Covey and Stein2011:130–131). As noted by Morris and colleagues, this collection of unusual artifacts “indicates ritual or festive activity, perhaps pertaining to brewing, given the vessels placed in the cache” (Reference Morris, Alan Covey and Stein2011:134). Participants in the feasting event elected to deposit this quero in “the space of the mediating groups that helped create ties between the rulers and the non-Inca” (Morris Reference Morris, Evans and Pillsbury2004:311).

Figure 3. Left: Wooden quero found in situ at Húanuco Pampa (image by Craig Morris and used courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History). Right: Administrative palace from Húanuco Pampa, with star indicating the quero find (redrawn from Morris et al. Reference Morris, Alan Covey and Stein2011:Figure 5.13). (Color online)

Queros and the End of Empire at Moqi

I now present two new examples of single queros found in ritual contexts at the Late Horizon site of Moqi, located in the Locumba Valley of southern Peru (Figures 1 and 2). Discussion of the archaeological contexts in which they were recovered and comparison with other queros found at the site—all of which were found as pairs—are consistent with interpretation of these single queros as inalienable objects that were repositories of memory, symbols of a new group identity within the Inka world order, and active participants in constituting relationships between the community and the empire.

Situated at 2,800 m asl, Moqi is a 25 ha administrative site constructed de novo by the Inka on their incorporation of the region during the Late Horizon. After a century or less of occupation, the site was abandoned at some point after the Inka fell to European conquest. Seven excavation units placed throughout the site demonstrate that the buildings were no longer in use and the roofs absent—sometimes collapsed or removed, in other cases burned—when volcanic ash from the Huaynaputina eruption fell in a thin layer over the site in AD 1600.Footnote 6 There were no subsequent efforts to remove the ash or reoccupy the buildings. Material evidence of contact with Spanish culture is correspondingly scarce at the site, consisting of just two sherds of colonial glazed pottery (of 9,609 sherds recovered in excavations and surface collections) and a handful of corroded iron fragments, totaling less than 50 g in weight. These data suggest that the site was occupied for only a short time after European contact and then was abandoned by its native inhabitants.

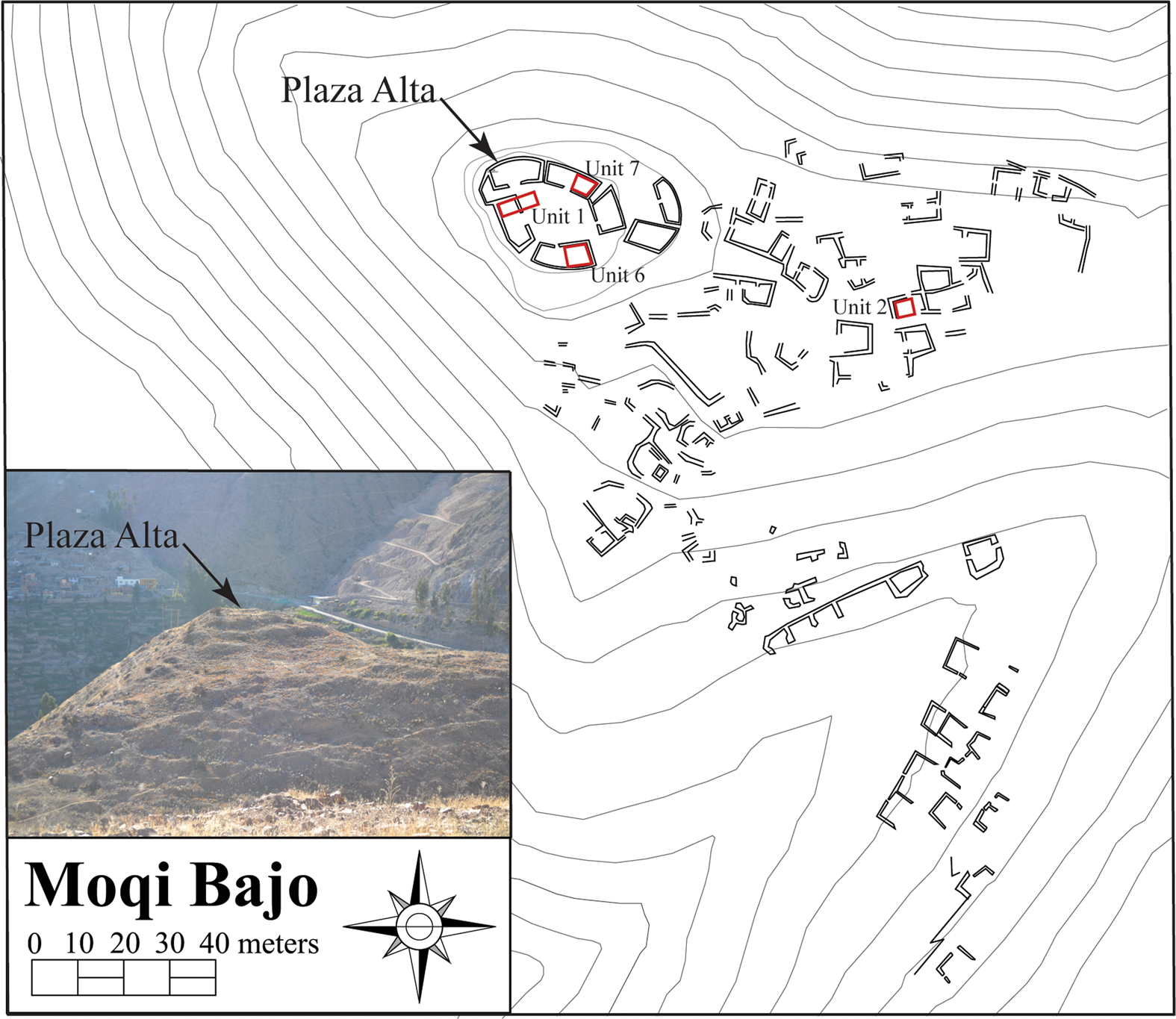

Moqi is divided into two sectors: Moqi Alto and Moqi Bajo (Figure 2). Moqi Alto comprises complexes of Inka-style rectilinear buildings and plazas where administrative and ceremonial activities took place. Moqi Bajo is a residential sector with relatively lower-quality architecture where site inhabitants lived (Figure 4). Its focal point is a small hill that was artificially leveled to form the Plaza Alta, which is surrounded by five well-constructed rectangular buildings. Although their circular arrangement suggests that they were built by local people, the buildings share construction characteristics with the Inka structures in Moqi Alto and thus reference the imperial connections underpinning the authority of the local curaca.

Figure 4. Moqi Bajo, showing locations of excavation units (redrawn from map created by Hans Barnard). Inset: View of Moqi Bajo highlighting the elevated location of the Plaza Alta (photo by Colleen Zori). (Color online)

Queros from the Site of Moqi

Eight queros have been archaeologically excavated from the site of Moqi, all from the Moqi Bajo sector. Six were undecorated and recovered as pairs interred with three adult individuals: two males and one female (Table 1). They all were found in Cemetery 2, a series of stone-lined cist tombs cut into the terraced slopes below the Plaza Alta. The cups in each pair are comparable in size and form, suggesting production as a matched set. As has been noted archaeologically and ethnographically, there often exists a parallel system of like-objects or replicas that draw on the prestige of original inalienable objects (Callaghan Reference Callaghan2014; Kovacevich Reference Kovacevich2014:98–99)—in this case, elaborately incised Inka queros. The high quality of the woodworking and the absence of decoration suggest that there may have been a prohibition against replication of imperial designs; this would be in keeping with other types of sumptuary laws imposed by the Inka (Moore Reference Moore1958). These pairs of undecorated queros likely represent vessels used by Moqi's inhabitants in community-level toasting conducted in parallel with toasting using the decorated queros bestowed by the empire.

Two additional queros were found in a 2 × 8 m trench encompassing the northwestern end of one of the structures surrounding the Plaza Alta (Unit 1 in Figure 4). Their presence suggests that this may have been the structure built at the behest of the Inka to memorialize the treaty with Moqi's inhabitants and store the vessels. Preparation of food, perhaps for state-sponsored feasts, was carried out on a hearth internal to the structure's eastern wall. Roughly outlined by slabs of rock, this hearth was 110 × 50 cm in size and contained ash deposits 32 cm deep.

The two queros found in Unit 1 differ from the others found at Moqi in that they were (1) decorated; (2) found singly, instead of in pairs; and (3) recovered from contexts that were ritual in nature but were not tombs. Both appear to have been deposited as part of an extended sequence of ritualized activity associated with the abandonment of the site.

Stratigraphically, the quero deposited first was found in a pit excavated through the primary floor layer of the structure. Emplacement of this ritual deposit occurred just before the incineration of the roof—the burn layer indicated in dark gray in Figure 5—followed by the deposition of the second quero and abandonment of the site. This pit contained the bundled refuse resulting from a single ritual food consumption event or feast. The ritual nature of the event is indicated by the fact that the deposit contains the implements used throughout the entire affair, including those that were still functional. These include equipment for preparing the feast—a grinding stone, copper or copper alloy crescent-shaped knife, and utilitarian cooking vessels—as well as the feasting debris and the vessels used for serving the food. The cut-marked bones of at least two juvenile camelids, marine shells, and extensive botanicals comprised the feasting remains, whereas serving wares included fragments of decorated Inka-style bowls. The quero, which was used during the ritual food consumption event indicated by these remains, had been similarly deposited into the pit.

Figure 5. Profile drawing of Unit 1 at Moqi, showing the AD 1600 Huaynaputina ash, burn layer from the burned roof, and the pit in which the quero and feasting remains were recovered (illustration by Colleen Zori).

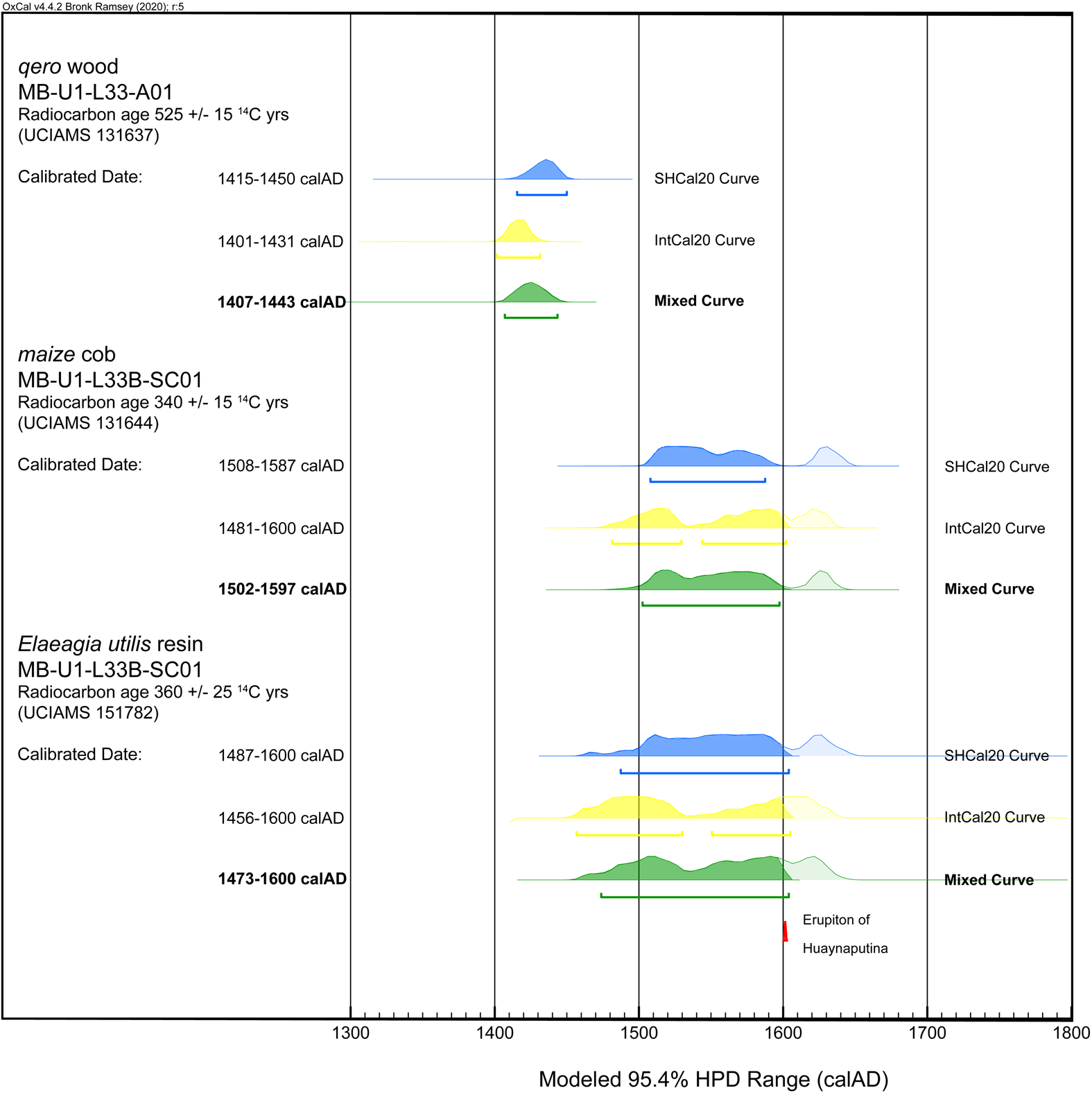

Surprisingly, this quero was decorated with resin-inlaid designs. Green, red, yellow, and black resin had been used to depict at least four parrots bordered by a yellow band above and beneath (Figure 6). It is widely thought that resin-inlaid queros date exclusively to the colonial period (Cummins Reference Cummins2002; Rowe Reference Rowe and Lathrop1961; but see Martínez Reference Martínez and de los Angeles Muñoz2018). Radiocarbon dating of the wood of the vessel, however, yielded an unexpectedly early date of 525 ± 15 BP (UCIAMS#131637; quero wood; δC = 22.2 ± 0.1‰), corresponding to cal AD 1407–1443 (p = 95.4%, mixed curve [SHCal20 and IntCal20], as per Marsh et al. Reference Marsh, Bruno, Fritz, Baker, Capriles and Hastorf2018; Figure 7). Decoration of the vessel and its eventual deposition yielded dates that unfortunately straddle the end of the Late Horizon and the arrival of the Spaniards in AD 1532. A sample of the resin used to decorate the quero, identified as deriving from the Elaeagia utilis plant (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Kaplan and Derrick2015), was dated 360 ± 25 BP (UCIAMS#151782; resin decoration; δC = n.a.), corresponding to cal AD 1473–1600 (p = 95.4%, mixed curve). A maize cob taken from the feast deposit yielded a date of 340 ± 15 BP (UCIAMS#131644; maize cob; δC = 11.1 ± 0.1‰), corresponding to cal AD 1502–1597 (p = 95.4%, mixed curve). Whether this resin-inlaid quero was produced during the Late Horizon or the early part of the colonial period, the important point is that it was found in a context very similar to the Inka quero recovered at Huánuco Pampa—among the bundled debris from a ritual feasting event.

Figure 6. Resin-inlaid quero found bundled with the feasting debris in Unit 1 at Moqi (photo by Colleen Zori). (Color online)

Figure 7. Radiocarbon dates for the quero wood, maize cob among the feasting debris, and the resin decoration (figure by Brian Damiata and used with permission). (Color online)

After the emplacement of the feasting bundle including the resin-inlaid quero, there was no intervening deposition prior to the incineration of the ichu grass of the structure's roof. Immediately atop this ash layer was found the second and final single quero deposited at Moqi Bajo. It displays a typical Inka chevron and diamond designs (Figure 8). I suggest that the Inka-style quero was placed atop this burn layer at the conclusion of the closing ritual that began with the feast represented by the resin-inlaid quero. This rite not only sealed the departure of the site's population and the abandonment of Moqi but also marked the termination of the community's relationship to the Inka Empire and all the benefits and obligations that it entailed.

Figure 8. Incised geometric quero found atop the burned roof in Unit 1 at Moqi (photo by Colleen Zori). (Color online)

Discussion and Conclusions

Ethnohistoric documents and archaeological data bear witness to the fact that queros, such as those found at Moqi, share many of the attributes of inalienable objects. They were produced by specialized Inka artisans using the empire's hegemonizing abstract geometric style and, later, resin-inlaid decorations. These vessels did not circulate through mundane exchange transactions but were instead gifted in one direction—from the emperor to representatives of this provincial community—where they would have remained in local possession and perhaps been stored in the high-status structure in the Plaza Alta of Moqi Bajo. After their initial bestowal, the queros continued to be used for toasting in later interactions between local and imperial representatives.

The queros at Moqi may have acted as symbolic capital for the community's leader, brought out during feasting occasions as both a commemoration and a manifestation of the authority endowed by a personal relationship with the empire. Ethnographic and ethnohistoric research indicates that, for traditional Andean peoples, “objects that have had a prior relationship with other places, things, or people are thought to remain in communication even after their physical separation” (Sillar Reference Sillar2009:367). Wooden queros, bestowed on local individuals by the Inka or by representatives acting in his name, would have been irrevocably tied to the Inka emperor—himself a deity whose rule was divinely sanctioned through myth and symbols including queros—who had drunk from it. Thus, a quero was an important emblem of an individual's relationship with the Inka and a source of local authority. As noted by Cummins, queros and other important objects “constitute participants in and therefore ‘witnesses’ to past events. Their existence potentially allows a speaker to recount the past as something known firsthand” (Reference Cummins2002:29). They were objects of memory that evoked past events of state-sponsored feasting and drew attention to the rights, roles, and privileges of the person charged with presiding over the vessels. Queros like those found at Moqi thus mediated relationships between provincial peoples, referencing relationships with the empire but instantiated in local actions that could be seen as aggrandizing a particular individual and authenticating his or her authority vis-à-vis connections with the empire.

At other sites throughout the Andes, pairs of Inka queros interred in tombs symbolized an individual's personal and political persona. This could extend to the family or kinship group, as indicated by the incorporation of Inka queros into chullpa burials. Because of the inalienable nature of these queros, relationships forged through them could not simply be transferred to a successor. Instead, the vessels were interred with the individual with whom the Inka had negotiated, projecting this relationship into the afterlife. In some cases, such relationships were maintained by the family group and continued to play a role in toasting the dead, keeping alive the identities and power drawn from connections to the Inka.

By contrast, I suggest that the single queros deposited in ritualized but non-mortuary contexts—such as those at San Juan de Pariachi, Huánuco Pampa, and Moqi—have a meaning distinct from those deposited in tombs with particular individuals. One implication of making offerings of a single quero is that the matched pair could no longer be used by any single person for identity display and self-promotion, whether in future toasting situations or on the death of the individual leader through performative bundling in the mortuary ritual. This suggests that these particular queros may have been viewed as collectively owned by the community and therefore both constitutive and emblematic of the group's identity and its relationship with the Inka. Their deposition in ritual contexts and in public (notwithstanding sometimes access-restricted) locales may represent a communal decision to make an offering of an object important to the community. In this way, single queros in ritualized deposits may represent tools used to “defeat” hierarchies: because they are “repositories and validations of group identity, they serve as a system of checks and balances to individual aggrandizement and personal gain” (Mills Reference Mills2004:248). At Moqi, deposition of the resin-inlaid quero marked a communal decision to ritually bundle this vessel with the remnants of a feast. Subsequently, the careful ritualization of placing the incised quero directly atop the burned roof just prior to abandonment of the site indexes efforts to mitigate the risk of abandoning a site where the people had been translocated by the Inka, at the same time as they were cutting off the economic ties symbolized by the queros themselves. In both cases, the performance of deposition contravened the queros’ potential power to elevate the status of the individual to whom the vessels had originally been given, instead making a statement best interpreted as on behalf of the entire community.

One characteristic that the sites of San Juan de Pariachi, Huánuco Pampa, and Moqi have in common is that they were all built at the behest of the Inka, with no preexisting local settlement prior to imperial incorporation. This means that they were also populated at the demand of the Inka, with inhabitants drawn from the surrounding area or brought in as colonists from distant lands. Whether such migrations were voluntary or coerced, life in these new Inka settlements required the formation of novel social relationships, both internally within the community and externally with the overarching political institution of the Inka Empire. Under such tumultuous social conditions, promotion of a shared community identity within the Inka world order—recalling the relationship that the community had entered into with the empire—may have been more important than individual self-advancement (Zori Reference Zori and Cann2018). In these communities, then, queros were important symbols around which such relationships were commemorated and strengthened. As with the quero deposited atop the burned roof at Moqi prior to abandonment of the site, they were also a means by which these associations could be brought to a close.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with authorization from the Peruvian Ministerio de Cultura (Resolución Directoral No. 527-2012/DGPC/VMPCIC/MC). My gratitude to my codirector, Jesus Gordillo Begazo, as well as the Institute for Field Research, many IFR field school students, La Universidad Privada de Tacna, and the communities of Cambaya and Borogueña, for making research at Moqi possible. Additional funding for radiocarbon dating was provided by the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA, with thanks to Charles Stanish. Davide Zori, along with three anonymous reviewers, provided helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Data Availability Statement

The archaeological materials recovered from Moqi are under the custody of the Peruvian Ministerio de Cultura—Tacna. Additional data can be obtained by contacting the author.