Introduction

If department stores aim to heighten Korean colour in their stores, first of all, they need to display products unique to Korea. Once things like t’aegŭksŏn (t’aegŭk-designed fans) or hwamunsŏk (figured mats) are spread out, the stores taste Korean. However, with such expression of Korean mood, the spirit and flavour of a work of art cannot be Korean. The work would be Koreanistic art rather than Korean art.Footnote 1

There are too many people who consider so-called Korean feelings or sentiments to be souvenirs sold at department stores.Footnote 2

The above two quotations on the Korean colour of department stores’ displays and products are the words of Yi T’aejun (1904–?), one of the modernist writers who searched for the Korean aesthetic in 1930s colonial Korea. In discussions of how to embody Koreanness in art and film, Yi cited souvenirs sold at department stores and their showrooms as typical examples of the inauthentic representation of Korea, which artists and film-makers should avoid. Yi meant that Koreanness could not be represented by mere displays of Korean artefacts.

Regardless of Yi’s criticism, however, the department stores’ souvenirs were popular items for foreign, especially Japanese, tourists visiting Korea. In August 1934, two months before Yi’s first comment, Mitsukoshi department store’s Keijō (the name of Seoul during the colonial period) branch held an ‘Exhibition of Korean Souvenirs’ in its gallery.Footnote 3 Tourist guidebooks and pamphlets introduced Mitsukoshi’s Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl as one of the best indigenous local products that tourists should shop for in Korea (Figure 1 and Figure 2).Footnote 4 Japanese tourists purchased the artefacts as a token that proved their experience of authentic Korea.

Figure 1. Koryŏ-style celadon tea set with Mitsukoshi seal.

Figure 2. Lacquered dish set with mother-of-pearl inlay with Mitsukoshi label.

Indeed, the production and sale of Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl was expanded considerably in the wake of increasing demand for tourist souvenirs during the colonial period. These colonial-era crafts became a controversial issue in the history of Korean craft. Some scholars have a strong antipathy to the development of Korean traditional crafts as souvenirs catering to Japanese tourists.Footnote 5 They claim that such commoditization made Korean crafts lose the ‘ethnic colour’ of Korea, and ultimately distorted the tradition. On the other hand, there are arguments that Japanese enthusiasm for these colonial artefacts contributed to the preservation of Korean traditional crafts, which were in danger of extinction.Footnote 6

The purpose of this article is not to determine whether Mitsukoshi’s Korean products were genuine Korean crafts or not. Rather, it explores why authentic Korea was desired by Japanese tourists and how the authenticity was constructed for their consumption through Mitsukoshi’s Korean Product Showroom and its products. Authenticity is a key concept in tourism studies. Earlier studies had distinguished between a real local culture and a culture performed for tourists, and criticized the latter, ‘pseudo-events’ or ‘staged authenticity’, for being inauthentic.Footnote 7 On the other hand, later studies focused on how tourists perceive ‘staged authenticity’ as being authentic, and redefined authenticity as a set of socially constructed symbolic meanings communicated by toured objects.Footnote 8 While the earlier studies’ approach is referred to as an ‘objectivist conception of authenticity’, the later studies’ approach is referred to as a ‘constructivist conception of authenticity’. I adopt the constructivist perspective to examine the authenticity of Mitsukoshi’s Korean Product Showroom and its products.

The primary interest of this article lies in exploring the ways in which Keijō Mitsukoshi’s Korean Product Showroom and its Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl represented ‘pure Korea’ constructed for Japanese consumption. How did a famed Japanese department store in colonial Korea market the local culture of the colony by targeting tourists from the metropole? From its inception in nineteenth century Europe in the midst of imperial expansion, the department store had capitalized on customers’ fascination with exoticism. Famous department stores, such as Le Bon Marché in Paris and Liberty in London, offered Oriental artefacts for sale.Footnote 9 They created an exotic atmosphere through their catalogues, posters, and displays to promote Oriental goods. In particular, their showrooms for Oriental goods were carefully designed to enhance the exotic appeal of these items. Keijō Mitsukoshi’s Korean Product Showroom followed suit. An interesting difference is that Keijō Mitsukoshi’s showroom reproduced Korea within Korea, not in the distant metropole.

This article examines the inauthentic authenticity of ‘Korean style’ and ‘Korean products’ that the Japanese produced and consumed in colonial Korea. It also examines the role Japanese residents of Korea played as intermediaries who participated in the production and sale of Korean artefacts for Japanese tourists from the metropole.

Korean Product Showroom: Costumed in ‘Pure Korean Style’

In 1905 Korea became a protectorate of Japan and the Japanese Residency-General of Korea was established. The first Japanese Resident-General of Korea, Itō Hirobumi (1841–1909), advised Mitsukoshi to extend its business into Seoul and suggested that it supply all goods the Residency-General would need for its establishment. Itō expected Mitsukoshi to serve as a cultural agency introducing Japanese products and lifestyle to Korea.Footnote 10 With Itō’s support, Mitsukoshi opened a subbranch office in Seoul in 1906. After Japan annexed Korea in 1910, Keijō Mitsukoshi steadily developed its business and was finally elevated to the status of a proper branch in September 1929. The next year Mitsukoshi relocated its store to the very centre of the city where Keijō City Hall had been located until 1926.Footnote 11 In October 1930 Mitsukoshi’s new building was completed as a reinforced concrete structure with four stories above ground and one below (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mitsukoshi Department Store Keijō Branch.

The architecture magazine Chōsen to Kenchiku introduced Mitsukoshi’s new building in detail, assigning a considerable number of pages to photographs and descriptions of its interior and exterior.Footnote 12 The building was designed by Mitsukoshi’s own architecture firm in Neo-Renaissance style, following the example of Mitsukoshi’s flagship store in Tokyo Nihonbashi. Hayashi Kōhei (1880–1934), who had been in charge of interior design when Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi was built in 1914, participated as the provisional chief of the architecture department in the construction of Keijō Mitsukoshi in 1930. The highly visible and distinct architecture of Keijō Mitsukoshi had a significant impact on the urban landscape of colonial Seoul, signifying the modernity that Japan had brought to Korea.

The new location of Keijō Mitsukoshi was at the entrance of Honmachi. During the colonial period, Seoul was divided into the predominantly Korean-inhabited northern village (today’s Chongno) and the Japanese-populated southern village (today’s Ch’ungmuro and Namdaemun areas).Footnote 13 The central commercial area in the southern village, Honmachi was established and developed by Japanese merchants and blossomed into the most fashionable and bustling street in colonial Seoul. As it was called ‘Keijō’s Ginza’, Honmachi was a place that made Koreans imagine Japan (as modern) and reminded the Japanese of Japan (as home). In the September 1929 issue of the magazine Pyŏlgŏn’gon, a Korean journalist noted, ‘When I enter there [Honmachi], I feel as if I am leaving Korea and traveling to Japan’.Footnote 14

Even within Honmachi, Mitsukoshi was an iconic place filled with all the modern comforts from Japan. In 1930s Seoul there were a total of five department stores. Mitsukoshi, Jojiya, Minakai, and Hiarata were Japanese stores in the southern village, and Hwashin was a Korean one in the northern village.Footnote 15 Even among the four Japanese department stores, Mitsukoshi was the most luxurious store selling Japanese and Western products. Comparing the floor plan of Keijō Mitsukoshi with those of Mitsukoshi stores in Japan, we can see a faithful duplication. The interior space of Keijō Mitsukoshi was much like that of its Tokyo counterpart, having a central hall, a grand staircase, elevators, lounges, restaurants, a gallery, a theatre, a roof garden, a tea room, and even a small Shintō shrine (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Keijō Mitsukoshi in section.

At Keijō Mitsukoshi, Japanese settlers were able to purchase items they had used in Japan and to enjoy the lifestyle associated with those goods, and wealthy Koreans were able to taste modern life with imported goods from Japan. In this way, Keijō Mitsukoshi, with the very similar design and structure to its metropolitan counterparts, served as a venue for experiencing ‘modern Japan’ in colonial Seoul.

The Korean Product Showroom was the sole place where visitors could encounter Korea within Keijō Mitsukoshi. Before Keijō Mitsukoshi opened the Korean Product Showroom in its new store in 1930, it had dealt with indigenous products of Korea on its old store’s third floor.Footnote 16 As it enlarged the store with the new construction, Keijō Mitsukoshi expanded the sales of local Korean products and placed the showroom on the first floor near the western entrance of the building. The change of location from the third to the first floor suggests that the Korean Product Showroom was geared towards Japanese tourists, who were interested in shopping for indigenous products of Korea rather than browsing the whole store, which was full of goods imported from Japan. Since the late 1920s Japanese tourism to Korea had been invigorated and the number of leisure travellers had increased.Footnote 17 The Japan Tourist Bureau (JTB) opened its guide office on the first floor of Mitsukoshi’s new store and provided travel information and services to visitors.Footnote 18 Thus tourists who stopped by the JTB office for ticketing and reservations were readily able to shop for Korean products at the nearby showroom.

According to the description in Chōsen to Kenchiku, the Korean Product Showroom was designed in ‘pure Korean style’ (jun Chōsensiki).Footnote 19 It was the only space decorated in this manner within the Neo-Renaissance style building. What, then, did ‘pure Korean style’ mean in the design of architecture at the time?

Among the ‘pure Korean style’ structures built during the colonial period, probably the most famous example was the six main pavilions of the Korea Exposition held at the Kyŏngbok Palace in 1929 (Figure 5).Footnote 20

Figure 5. South Industrial Hall of the Korea Exposition, Chōsen to Kenchiku, vol. 8, no. 9, 1929.

The head of the architecture department of the Ministry of Home Affairs at the Government-General of Korea, Iwai Chōsaburō (1879–?), announced that the 1929 exposition’s architecture respected ‘Korean colour’ in terms of its materials, style, and building contractor.Footnote 21 The 1929 exposition’s main pavilions, simple box-shaped temporary structures, were in the form of tiled-roof buildings, and their facades were decorated with tanch’ŏng (the multi-coloured paintwork found on traditional Korean wooden buildings and artefacts) and wanjach’ang (windows with a swastika-shaped frame). Iwai explained the reason for designing the main pavilions in ‘pure Korean style’ as follows:

as for an exposition in Korea, there is another thing that should be considered. That is to make it [the exposition] taste Korean. In other words, we thought that we needed to make the buildings be felt intuitively as pavilions of the Korea exposition. We wanted to not only give the architecture of the Korea Exposition new taste, but also show it as one full of Korean mood with the flavour of Korea as much as possible. Then Korean people would certainly have a good feeling. Even visitors from naichi (lit. the inner land, referring to the imperial metropole in contrast to the colonies, gaichi, the outer land) surely expect that the exposition of Korea has what tastes Korean. Thus, after much consideration we concluded that we cannot acquire the true significance of the Korea exposition without making the architecture satisfy that expectation.Footnote 22

According to Iwai, the 1929 exposition’s construction of ‘pure Korean style’ pavilions and emphasis on ‘Korean colour’ was meant to please Koreans and match naichi Japanese expectations.

Yet ironically, the ‘pure Korean style’ pavilions of the 1929 exposition were constructed on the very site where the original buildings of the Kyŏngbok Palace had been demolished or displaced. Already in 1915 when the Korean Products’ Competitive Exposition was held in the Kyŏngbok Palace, the exposition grounds had transformed the architectural and spatial principles of the Korean palace complex.Footnote 23 After the 1915 exposition ended, the construction of a new Government-General building was started on the exposition grounds and the Neo-Baroque style building was completed in front of Kŭnjŏngjŏn, the throne hall of Kyŏngbok Palace, in October 1926. The main gate of the Kyŏngbok Palace, Kwanghwamun, was deconstructed to make the new Government-General building open to the street, and reconstructed on the east side of the palace. Not only were some palace buildings gone, but also the central axis of the palace was eliminated. In other words, the ‘pure Korean style’ architecture of the 1929 exposition came into being where Korean architecture was lost.Footnote 24 In his serial report on the 1929 exposition published in Chosŏn Ilbo, novelist Yŏm Sangsŏp (1897∼1963) criticized the ‘pure Korean style’ architecture of the exposition for being as meretricious as his wife’s sewing box covered with coloured paper.Footnote 25 Yŏm lamented that the exposition was nothing more than a microcosm of ‘Korea that lost Korea’.Footnote 26

As with the 1929 exposition pavilions, Mitsukoshi’s Korean Product Showroom employed tanch’ŏng and wanjach’ang to manifest ‘pure Korean style’ in its design (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Korean Product Showroom, Chōsen to Kenchiku, vol. 9, no. 11, 1930.

The brilliant colour contrast of tanch’ŏng (lit. cinnabar and blue-green) and the swastika pattern (卍) of wanjach’ang are indeed the most conspicuous features in Korean architecture. In a photograph of the Korean Product Showroom published in Chōsen to Kenchiku, we can find that the same wanjach’ang pattern as in the 1929 exposition decorated the upper part of the showroom. Below that, a simple wooden structure was built and its columns, crossbeam, and ceiling were vividly coloured with tanch’ŏng. In the black and white photograph in Chōsen to Kenchiku it is hard to tell the colours, but the caption described them as ‘polychromatic decoration’.Footnote 27 In fact, tanch’ŏng and wanjach’ang played not just an ornamental role but also a functional one in traditional Korean architecture. The paint of tanch’ŏng prevents wooden structures from being weathered by wind and rain and damaged by disease and insects. The muntins of wanjach’ang support the window paper. Inside Mitsukoshi’s modern reinforced concrete building there was no architectural space that required those practical functions, which was also true of the 1929 exposition pavilions. In both cases tanch’ŏng and wanjach’ang served a symbolic function as a signifier of Koreanness. Indeed, tanch’ŏng and wanjach’ang were adopted extensively for tourist buildings designed in ‘Korean style’ including restaurants, kisaeng houses, and souvenir shops. As Patricia A. Morton has pointed out in her book on the 1931 Colonial Exposition in Paris, the authenticity of the colonial pavilions was generated not by their accuracy or correspondence with an actual building in the colony, but by the typical details of the native architecture.Footnote 28 The 1929 Korea Exposition pavilions and Mitsukoshi’s Korean Product Showroom alike were costumed in ‘pure Korean style’ in order to stage Korea where Korea was lost or absent.

Tours to Korea: Nostalgia for a purer and simpler life

Japanese tourism to Korea grew in conjunction with a boom in the tourism industry in the metropole beginning in the mid 1920s. In 1924 the Japan Travel Culture Association was founded by linking together a growing national network of regional travel associations under the auspices of the Ministry of Railways.Footnote 29 As soon as it was established, the association began publication of Tabi, a monthly travel magazine. As one of the most influential media in tourism, Tabi ran travelogues and provided information about transportation, accommodations, and the geography and customs of popular tourist destinations until it suspended publication in 1943. In 1925 the JTB opened guide offices inside Tokyo Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi, Ginza Matsuya, Osaka Mitsukoshi, and Osaka Daimaru. Over the next few years the JTB opened offices in most of the major department stores, to such an extent that ‘Where there is a department store, the JTB’s guide office must exist’.Footnote 30 The stores also became a major venue for exhibitions that the Japan Travel Culture Association and the Ministry of Railways held to raise public consciousness about tourism.Footnote 31 In 1926 alone, Japanese tourists used the JTB’s services 158,000 times. By 1936, this number had increased almost 20-fold to over 2,858,000.Footnote 32

Through their publications and exhibitions, the JTB and transportation companies promoted not only the provinces within the Japanese archipelago but also the colonies as places to have a pleasurable diversion, escaping from one’s everyday surroundings and activities. The JTB’s itinerary compendium Ryotei to Hiyōgaisan introduced sample travel plans to Karafuto, Korea, Manchuria, and Taiwan as well as domestic regions.Footnote 33 In the first issue of Tabi, the Osaka Mercantile Shipping Company advertised routes to Korea, Manchuria, China, and Taiwan alongside ones to Setonaikai and Kishū. The South Manchurian Railway Company placed an advertisement promoting travel to Korea, Manchuria, and China in the same issue. In December 1924, Tabi published its first special issue, which was devoted to ‘Mansen’ (Manchuria and Korea). In 1930, the year Keijō Mitsukoshi opened the Korean Product Showroom in its new store, Tabi ran Korea-related articles in each issue from May to September.Footnote 34 The next year Tabi serialized its ‘Guide for Travel to Korea, Manchuria and China’ from January to March, giving detailed information regarding travel routes, ticket prices, accommodation, local words, local currency, customs, passports, souvenirs, and so on.Footnote 35 As Arayama Masahiko noted, Manchuria, Korea, and Taiwan were considered just as likely tourist destinations as Izu, Hakone, Hokkaidō, or Kyūshū.Footnote 36 The expense involved in travel was comparable as well, since colonial tourism did not cost much more than domestic tourism.Footnote 37

Meanwhile in Korea, in 1925 the Government-General of Korea started directly managing the railways on the Korean peninsula, which had been managed in trust by the South Manchuria Railway Company.Footnote 38 In order to increase the number of passengers, the Railway Bureau of the Government-General made an effort to attract Japanese tourists to visit Korea, developing tourist sites and infrastructure along the major railroads. In 1926 the Railway Bureau selected 42 sites including scenic spots, historic remains, old temples, hot springs, and beaches across the Korean peninsula, and promoted them as tourist destinations.Footnote 39 Large numbers of guidebooks, brochures, maps, and picture postcards of Korea were published and distributed through ticket offices at major ports, railway stations, and department stores throughout the Japanese empire. The Government-General even produced films showing scenic spots and places of historic interest on the Korean peninsula and screened them in Japan.Footnote 40 In 1933 the Keijō Tourism Association was founded by the united effort of the Keijō municipal government and businessmen engaged in tourism.Footnote 41 The association not only provided convenience for tourists, from arranging sightseeing buses and taxis to planning itineraries, but also held various events including kisaeng dance performances. Like in the metropole, Keijō Mitsukoshi provided the venue for tourism exhibitions held by the Keijō Tourism Association and the Railway Bureau of the Government-General.Footnote 42 In 1937, Chōsen Shinbunsha, one of the three major Japanese newspaper companies in colonial Korea, held a ‘Korea Tourism Exhibition’ in Osaka Mitsukoshi under the auspices of the Railway Bureau of the Government-General.Footnote 43

In The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class, the seminal work of tourism studies, Dean MacCannell asserted that modern tourism arose out of a search for authenticity.Footnote 44 The sense of inauthenticity and instability on which the progress of modernity depends generates anxiety about alienation and displacement. For people in modern society, authenticity is presumed to be located ‘in other historical periods and other cultures, in purer, simpler life-styles’.Footnote 45 Tourism offers an experience of purer, simpler life for moderns who seek authenticity elsewhere, distant from present time and space. MacCannell’s theory is useful in explaining the rise of tourism in 1920s and 1930s Japan, which was in the midst of modernization.

The rapid industrialization and urbanization of the Japanese metropole led to popular interest in ‘kyōdo’ (lit. native soil) during the 1920s and 1930s. The neologism kyōdo first emerged in the area of academic research by scholars of folklore studies (minzokugaku).Footnote 46 Yanagita Kunio (1875∼1962) organized a study group named ‘Kyōdo Kenkyūkai’ (Kyōdo Research Society) in 1907, established ‘Kyōdokai’ (Kyōdo Association) in 1910 with Nitobe Inazō (1862∼1933), and published a journal titled Kyōdo Kenkyū (Kyōdo Studies) in 1913. Yanagita and his colleagues directed their research toward rural Japan as a repository of authentic practices and customs that were rapidly vanishing in urban Japan. It was in the 1920s that the concept of kyōdo went beyond academic discourse and entered into the popular imagination. Various kyōdo themed movements including the kyōdo art movement and the kyōdo education movement started in the 1920s. The folk song movement active in the 1920s is one good example. Folk songs rediscovered or invented through the movement constructed a pastoral image of kyōdo and induced nostalgia among Japanese who had left home villages and migrated to the cities.Footnote 47 Kyōdo was represented as the landscape of the countryside, which, in contrast to the cities, seemed so untouched by modernization, and hence in which a purer and simpler life still seemed possible.

Kyōdo became an object of modern nostalgic longing rather than the basis for an actual lived life. A yearning for kyōdo contributed to the tourism boom beginning in the mid 1920s. The tourism industry encouraged the Japanese to travel to sites of a preurbanized, unspoiled nature, kyōdo, to search for what had been lost in modernization.Footnote 48 In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Tabi frequently published articles related to kyōdo, from kyōdo minyō (kyōdo folk songs) to kyōdo gangu (kyōdo toys). In 1928, a new magazine titled ‘Tabi to Densetsu’ (Tour and Folktale) was published with a subsidy from the Ministry of Railways. In 1933, JTB founded Nihon Kyōdo Gangu Kenkyūkai (Japan Kyōdo Toys Research Association) and promoted each region through its kyōdo toys.Footnote 49 Since toys are objects from childhood, kyōdo gangu might have stimulated further nostalgia for the lost past, overlapping the past time of individuals and the past time of society.

Kyōdo does not indicate one’s lived home but rather refers to an imagined home. Accordingly, for urban Japanese, kyōdo was not limited to rural areas within the Japanese archipelago. Colonial Korea was promoted as a nostalgic site where a primordial purity survived. Old Korean folk songs and folktales were introduced in the pages of Tabi.Footnote 50 In July 1935, Tabi produced a special issue on Korea and ran kyōdo geographer Odauchi Michitoshi (1875–1954)’s article on Korea in the opening pages of the volume (Figure 7).Footnote 51

Figure 7. Special issue on Korea, Tabi, July 1935.

The perspective and knowledge applied to kyōdo in the Japanese archipelago was projected onto colonial Korea. Korea was exotic enough in scenery and customs to remind Japanese tourists of ‘other historical periods and other cultures’, where authenticity is located. Ironically, Korea was thus able to be perceived as kyōdo (native land) by Japanese tourists from the modernized metropole. ‘Exotic’ and ‘native’, opposed to each other in definition, were intertwined in Japanese tourists’ imagination of Korea.Footnote 52

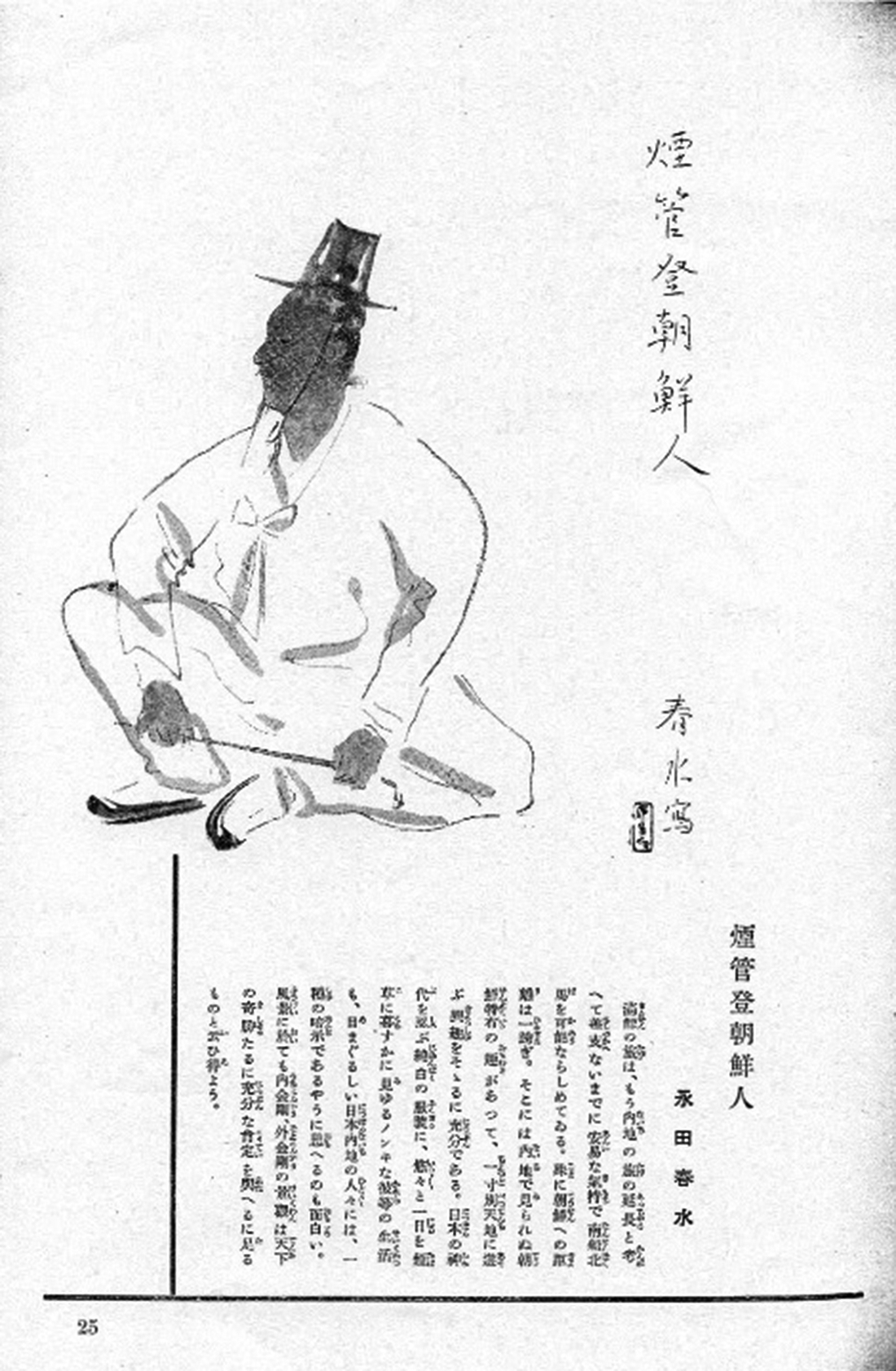

Japanese tourists’ experience of Korea, in which exoticism and nostalgia intersected, is well described in a short account that nihonga painter Nagata Shunsui (1889–1970) published in Tabi with an illustration of a white-robed Korean man holding a long tobacco pipe (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Nagata Shunsui, ‘Enkantō chōsenjin’, Tabi, May 1935.

Now tours to Manchuria and Korea have become so convenient as to make it possible to travel here and there easily, as if it were like an extension of naichi travel. The distance to Korea, in particular, is very short. There is a flavour unique to Korea that is impossible to taste in naichi, and thus you can feel excitement as if you were in another world. It is also interesting that the tranquil life of the Korean people, in white robes reminiscent of the Japanese mythical age, spending a day leisurely with tobacco, is thought of as a kind of suggestion by the Japanese from naichi, which changes at a dizzying speed. In terms of landscape, everybody agrees that the scenery of inner Diamond Mountain and outer Diamond Mountain is unparalleled in the world.Footnote 53

Despite its physical closeness, Korea was represented as a place that was remote from the rapidly changing metropole, as if remaining in Japan’s mythical past. There, in Korea, Japanese tourists got a sense of recuperating what they had lost in the rush to modernize in the metropole.

On the other hand, Japanese tourists’ disappointment about the modernized landscape of Korea is often found in their travelogues. In an essay titled ‘Going to Korea’ in Tabi, novelist Kitamura Susumu (1889–1958) said that there was nothing attractive to make him stop to see in the ‘colonial city’ Taegu, and he did not find the sort of mood he was seeking until he visited Kyŏngju, the ancient capital of the Shilla dynasty.Footnote 54 Arriving in Seoul as well, Kitamura was not fascinated by the city’s urban landscape and showed more interest in Kyŏngbok Palace and Piwŏn (the Secret Garden at Ch’angdŏk Palace). In contrast, the ancient city of P’yŏngyang allowed Kitamura to feel ‘pure Korean’ colour and flavour. Japanese tourists believed that their trip could be authentic only if they experienced ‘pure Korea’, which was distinguished from the industrialized and urbanized metropole. The frequent appearance of terms such as ‘pure Korean style’ and ‘Korea-like’ (Chōsen rashii) in the rhetoric of Japanese tourist literature reflects their anxious search for authentic Korea.

Kate McDonald argues that the emphasis on ‘local colour’ in Japanese tourism to Korea was relevant to the shift in the spatial politics of Japanese imperialism, from the ‘geography of civilization’ to the ‘geography of cultural pluralism’.Footnote 55 According to McDonald, in the late 1920s the major goal of Japanese tourism shifted from observing Korea’s modernization or Japanization to experiencing the regional difference of Korea. As Korea became defined as one of the ethnic and cultural regions which composed the growing multiethnic and multicultural empire of Japan, ‘Korean colour’ was not treated as an element to be eliminated but appreciated as a form of ‘local colour’.

Japanese tourists’ yearning for ‘pure Korea’ and their antipathy towards modernized or Japanized Korea were symptoms of ‘imperialist nostalgia’, which Renato Rosaldo defines as ‘a particular kind of nostalgia, often found under imperialism, where people mourn the passing of what they themselves have transformed’.Footnote 56 To retrieve lost authenticity, Japanese tourists from the metropole longed for Koreanness, but Koreanness had been transformed in the course of Japanese colonization under the guise of a ‘civilizing mission’ or ‘assimilation’. ‘Pure Korea’ was demanded by this ironic desire.

Korean products: Objects of Japanese desire

The image of an old Korean potter, dressed in white clothes and a hat called t’anggŏn and drawing a picture on the surface of celadon, was featured repeatedly in picture postcards and other visual materials that were produced to promote tourism to Korea (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Postcards of an old potter.

This image made potential tourists imagine and believe that the celadon they would buy was being produced by dedicated Korean artisans in the traditional manner preserved for centuries. The modernist fantasy of artist-as-lonely-creator was also projected onto the image of the old potter. However, the majority of Koryŏ-style celadon pieces that tourists purchased were actually mass-produced, with a factory-style division of labour, in workshops run by Japanese entrepreneurs in Korea.

Koryŏ celadon had virtually disappeared until the 1880s, when it began to be unearthed from ancient tombs near Kaesŏng, where members of the Koryŏ royal and aristocratic families were buried. Once Koryŏ celadon came out of the ground, it became the most sought-after item in the Korean art market, which was dominated by Japanese antique dealers.Footnote 57 Prior to the official annexation of Korea in 1910, Japanese antique dealers had already come to Korea and opened shops dealing with old Korean arts and artefacts.Footnote 58 From high-ranking officials to successful entrepreneurs, affluent Japanese settlers were eager to purchase Koryŏ celadon for their own collections and as gifts for their friends and families in Japan. For example, Itō Hirobumi was well known as a Koryŏ celadon aficionado who collected more than 1000 pieces of Koryŏ celadon while he resided in Korea. In Natsume Sōseki’s novel And Then as well, the protagonist was presented with a piece of Koryŏ celadon by a friend who worked at the Residency-General of Korea.Footnote 59 Japanese enthusiasm for Koryŏ celadon was more than just a matter of individual taste. Under the auspices of the Government-General of Korea, Japanese scholars conducted excavations and investigations of Koryŏ remains near Kaesŏng and the Yi Royal Household Museum (established as the Imperial Household Museum of the Korean Empire in 1908) and the Government-General Museum (established in 1915) vigorously collected Koryŏ celadon wares and exhibited them to the public. The institutional validation of Koryŏ celadon as the quintessential Korean art stimulated demand for it even more. Since almost all antique Koryŏ celadon wares were burial goods, their availability was limited. Even though illegal tomb raiding was rampant, the supply of Koryŏ celadon wares could not meet the rapidly increasing demand for them.Footnote 60 Antique Koryŏ celadon became scarcer on the art market and its price skyrocketed in the 1910s.

Inflation in the price of Koryŏ celadon led to the birth of the Koryŏ celadon revival business.Footnote 61 Seeing the sales potential in Koryŏ celadon reproductions, Japanese entrepreneurs established workshops to revive production from the 1910s. Koryŏ celadon reproduction was quite an expensive project and required a number of stages, from the excavation of kiln sites to the restoration of the manufacturing technique lost during the long hiatus. Accurate reconstruction of the idiosyncratic colour of Koryŏ celadon called ‘pisaek’ (jade colour) necessitated meticulous experiments with the composition of both the clay and the glaze, as well as the conditions of the firing process. There were few Koreans who could invest a large sum of money in this kind of experimentation, whose success was uncertain. It was not until the end of the 1920s that just one Korean-run Koryŏ celadon revival workshop was established.Footnote 62

Among the Koryŏ celadon revival workshops, Sanwa Kōraiyaki and Kanyō Kōraiyaki were outstanding in the quantity and quality of their products.Footnote 63 Both workshops were major suppliers of the Koryŏ-style celadon sold at Keijō Mitsukoshi’s Korean Product Showroom.Footnote 64 Also, both were closely related to a figure named Tomita Gisaku (1858–1930), one of the most prominent Japanese entrepreneurs in colonial Korea.Footnote 65 Through a close relationship with the first Governor-General of Korea, Terauchi Masatake (1852–1919), Tomita was able to launch a Koryŏ celadon revival business in Chinnamp’o, a port city in P’yŏngan province, where he had built up his enterprises.Footnote 66 The Government-General provided Sanwa Kōraiyaki with a subsidy of 1000 yen for start-up costs in 1912 and the province of P’yŏngan namdo provided a subsidy of 700 yen every year for operating expenses.Footnote 67 In 1911, after an introduction by Terauchi, Tomita invited Hamada Yoshinori (1882–1920), who had studied ceramic production at Saga Prefectural Arita Technical School, to his workshop.Footnote 68 In 1915, Yoshinori’s stepbrother Hamada Yoshikatsu (1895–1980), who graduated from the same school, joined the workshop as well. Tomita urged them to apply their modern knowledge of ceramic materials and techniques to the revival of Koryŏ celadon. Yoshinori had a thorough knowledge of the clay and glazes and Yoshikatsu had mastery of shaping and sculpting. By 1916, the Hamada brothers succeeded in producing items that closely resembled the celadon made during the Koryŏ period. In photographs of Sanwa Kōraiyaki products, we can find faithful reproductions of Koryŏ celadon masterpieces such as the Celadon Gourd-shaped Ewer and Stand with Inlaid Grape and Child Design and the Celadon Incense Burner with Openwork (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Koryŏ-style celadon wares produced by Sanwa Kōraiyaki, Tomita Gisaku den (1936).

The former was the first Koryŏ celadon piece that the Yi Royal Household Museum collected, having purchased it in 1908 from Japanese art dealer Kondō Sagorō for 950 yen, the price of a tile-roofed house at the time. The latter was also in the collection of the Yi Royal Household Museum and purchased from Shiraishi Masuhiko for 1200 yen in 1911.Footnote 69 Tomita’s workshop offered modern copies as an affordable alternative to the overpriced antique Koryŏ celadon wares, thereby attracting a broader consumer base.Footnote 70 In 1924 the value of Sanwa Kōraiyaki’s annual production reached 10,000 yen.Footnote 71

In 1924 Tomita took over Kanyō Kōraiyaki in Seoul.Footnote 72 Kanyō Kōraiyaki was initially founded as a celadon workshop associated with Umiichi Shōkai and run by Umii Benzō (1875–?). Umii opened Umiichi Shōkai at Honmachi in 1908 and dealt with a wide range of local products from all over Korea.Footnote 73 His shop was well received by Itō Hirobumi and the second Resident-General Sone Arasuke (1849–1910), and he took advantage of this approval to build his business. In 1912 Umii set up Kanyō Kōraiyaki at Higashishikenchō (today’s Jangchung-dong) and began to manufacture Koryŏ-style celadon for sale. By the mid 1910s, Kanyō Kōraiyaki was able to produce fine quality Koryŏ-style celadon and exhibited its products at expositions in Tokyo and Seoul.Footnote 74 Yu Kunhyung (1894–1993) and Hwang Inchoon (1894–1950), who are considered masters of modern Korean ceramics, acquired knowledge about and learned the techniques for Koryŏ celadon reproduction at the workshop, working as apprentices under Japanese artisans.Footnote 75 In 1913 Umii opened a branch at Tokyo Nihonbashi selling Koryŏ-style celadon produced in Kanyō Kōraiyaki. However, the Nihonbashi branch was severely damaged by the Great Kantō earthquake in 1923. The following year, to cover his losses, Umii sold Kanyō Kōraiyaki to Tomita.Footnote 76

Tomita Gisaku not only took over Kanyō Kōraiyaki, but also participated in the establishment of the Korean Art Workshop in August 1922.Footnote 77 The workshop was initially founded under the name Hansŏng Art Workshop in 1908 for the purpose of producing high-quality wares that the Korean Imperial Household would use for various rituals. With the annexation of Korea in 1910, Japan degraded the Korean sovereign’s title and demoted the Imperial Family of the Korean Empire to become the Yi Royal Family under the Japanese Emperor. In 1913 the workshop was renamed the Yi Royal Household Art Workshop and began selling its products to the general public. In 1922 the workshop was restructured into an incorporated company, the Korean Art Workshop, with Japanese investors as its main stockholders, and its management authority was officially transferred from the Yi Royal Household to the Japanese. Tomita was the second largest stockholder of the workshop after the Yi Royal Household.Footnote 78 When it was still the Yi Royal Household Art Workshop, a ceramics department was added to the workshop and it produced Koryŏ-style celadon called ‘Piwŏnjagi’ (celadon made in Piwŏn).Footnote 79 It is uncertain whether Keijō Mitsukoshi’s Korean Product Showroom dealt with the products of the Korean Art Workshop. When Tokyo Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi launched its Oriental section in 1921, it was provided with Korean artefacts from the Yi Royal Household Art Workshop.Footnote 80 Given that Mitsukoshi had already established a business relationship with the workshop, it is possible that its products were sold at Keijō Mitsukoshi’s Korean Product Showroom as well. In any case, all three of the workshops that produced the highest-quality Koryŏ-style celadon were under the ownership of Tomita in the mid 1920s. Tomita continued to develop his Koryŏ celadon revival business until the late 1920s with a subsidy from the Government-General.Footnote 81 With Tomita’s death in 1930, his son Tomita Seiichi succeeded him in this revival business.Footnote 82

Alongside Koryŏ-style celadon, lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl was the other best-selling item of the Korean Product Showroom.Footnote 83 It was the Japanese Government-General of Korea that discerned rather early the potential of Korean lacquerware as a profitable industry in colonial Korea and encouraged the production of these wares. Japan already had experience in developing its own traditional crafts into a modern export industry. The crafts constituted ten percent of all exports from Japan from the 1870s to the 1890s due to Japonisme, the Western craze for Japanese art and artefacts.Footnote 84 During the early years of the Meiji era when the infrastructure for modern industries had not yet been established, the Meiji government promoted the production of crafts as part of the shokusan kōgyō (increasing production and promoting industry) policy. Lacquerware formed a significant proportion of Japan’s export products. The same scenario was expected in colonial Korea, where high-quality raw lacquer could be acquired relatively inexpensively. The colonial government made an effort to secure a supply of raw lacquer, train skillful artisans, and promote the production of lacquerware for Japan’s domestic and export market.Footnote 85 The Central Research Laboratory, which the Government-General founded in 1912 for the study of various industries of Korea, conducted systematic research for the planting of lacquer trees and the improvement of the lacquer collection method.

In 1913, Governor-General Terauchi provided financial support for mother-of-pearl craftsmen in T’ongyŏng, a port city on the southern coast of the Korean peninsula.Footnote 86 During the Chosŏn period, T’ongyŏng, where government-managed workshops were located, had been a major producing area of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Among the decorative techniques applied to lacquerware, inlaying cut pieces of mother-of-pearl (najŏn) was deemed a recognizably Korean technique.Footnote 87 Until the Kamakura period, the mother-of-pearl inlay technique had also been widely used for the decoration of lacquerware in Japan. As time passed, however, the maki-e technique, in which gold or silver powder is sprinkled on the surface of wet lacquer, became the dominant decorative technique for Japanese lacquerware. On the other hand, in Korea, lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl had been continually produced throughout the country’s history. Beginning in the Three Kingdom period, Korea produced lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl and developed its glamorous and elaborate style during the Koryŏ period. Unlike Koryŏ celadon, lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl persisted into the Chosŏn period. By the turn of the twentieth century, however, the Korean craft industry in general experienced a decrease in production and a decline in quality, facing an influx of machine-manufactured goods. Even in the countryside of Korea, cheap industrial imports were widely used. Traditional small-scale handicraft productions could not survive the crisis. The production of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl was no exception. In 1895, the government-managed workshops in T’ongyŏng closed and the artisans were scattered.

Terauchi’s support for mother-of-pearl craftsmen in 1913 paved the way for reviving the production of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl in T’ongyŏng.Footnote 88 In 1915, a lacquerware department was founded within the T’ongyŏng Industrial Inheritance School. The department invited four lacquerware artisans from Japan and asked them to teach Korean mother-of-pearl craftsmen lacquerware techniques.Footnote 89 With interest from the Government-General, the scattered craftsmen came back to T’ongyŏng and the number of apprentices who were trained in the Industrial School increased. However, the artisans finishing the training were still struggling with a lack of capital to produce the product and market it. What was required for the revival of the mother-of-pearl inlay lacquerware industry was large-scale investment. Finally, in 1918, Tomita Gisaku established the T’ongyŏng Lacquerware Corporation with a capital investment of 50,000 yen.Footnote 90 Tomita, who had no connection with T’ongyŏng, set the business up as an incorporated company with himself as president and local notables, four Japanese and two Koreans, as the board of directors. Merging with the Inheritance School, the company continued the education of artisans in addition to the manufacture and sale of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl. The products of the T’ongyŏng Lacquerware Corporation were highly appreciated at domestic and international expositions and were popular as souvenirs and gifts among the Japanese. By 1928, annual production of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl manufactured in the T’ongyŏng area reached a value of 60,000 yen, and an attempt was even made to cultivate a market for T’ongyŏng lacquerware in the USA.Footnote 91 Large-scale lacquerware workshops, in common with Koryŏ celadon revival workshops, were run by the Japanese. According to a Tonga Ilbo article on 12 December 1933, a Japanese-owned workshop in T’ongyŏng produced 20,000 yen’s worth of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl per year (Figure 11).Footnote 92 By 1940, the workshop had grown to employ 50 workers and produce 70,000 yen’s worth of products.Footnote 93

Figure 11. T’ongyŏng Lacquerware Workshop.

Outside T’ongyŏng, Seoul was a major area where lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl workshops were located. Among the workshops in Seoul, the Yi Royal Household Art Workshop produced the best quality lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl. In 1915 the workshop produced these wares for submission to the Korean Products’ Competitive Exposition held in the same year.Footnote 94 From the time that the workshop was transformed into the Korean Art Workshop owned by Japanese stockholders in 1922, it further boosted the production of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Until 1936, when the workshop closed, Korean and Japanese artisans participated together in the production of its main items.Footnote 95

Figure 12. Lacquered inkstone box with mother-of-pearl inlay produced by Yi Royal Household Art Workshop.

Since the main consumers of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl were Japanese, the local workshops developed new-style products which catered to Japanese taste.Footnote 96 First, novel motifs were created to appeal to Japanese customers. For example, the Diamond Mountain, one of the most famous destinations in Korea for Japanese tourists, was used as a popular motif in various lacquered objects with mother-of-pearl inlay. The Diamond Mountain had been a favourite subject matter in Korean paintings, but it had rarely been used for the decoration of crafts in Korea. Secondly, the mother-of-pearl technique was often employed together with the maki-e technique. Maki-e was a representative technique used in Japanese lacquerware, but was seldom found in Korean lacquerware before the colonial period (Figure 12). Thirdly, new types of objects were made of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl, such as dishes and trays for chanoyu, a Japanese tea ceremony, or kaiseki-ryōri, a traditional multi-course Japanese meal. In other words, ‘Korean products’ that had not existed before in Korea were invented.

‘Pure Korea’: Constructive authenticity

Among two of the most desired Korean souvenirs by Japanese tourists, Koryŏ-style celadon was a modern ‘replica’ and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl adopted ‘Japanized’ style. In addition, Japanese capital and technology were inextricably involved in the production of both. How, then, did Japanese tourists, who were anxious to experience authentic Korea, perceive these ‘Korean products’ as metonyms for ‘pure Korea’ and claim the authenticity of their experience of Korea through the purchase of them?

Since MacCannell characterized tourism as a quest for authenticity, considerable debate and arguments have been generated on this contested concept in tourism studies. The discourse of authenticity became more complicated by distinguishing between object-related authenticity and activity-related authenticity in the tourist experience. Ning Wang divided object-related authenticity again into objective authenticity and constructive authenticity.Footnote 97 According to Wang’s division, Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl lacked objective authenticity but satisfied the criteria for constructive authenticity. While the former refers to authenticity as the original, the latter is constructed through the projection of tourists’ stereotyped images, expectations, and consciousness onto toured objects. For tourists, neither art collectors nor museum curators, the issue of whether objects are original is irrelevant, or less relevant. Japanese tourists consumed Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl as souvenirs, signs of the authenticity of their travel. Thus, it is more significant to know how they were formulated as signs of authenticity than to enquire whether they were original or not.

The fact that Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl won popularity as souvenir goods testifies to their satisfactory operation as signs of the authentic experience of ‘pure Korea’.Footnote 98 To properly serve as such signs, they had to be distinctive and representative of the place they referred to. The former quality was provided by their visual distinguishability and the latter by institutional confirmation.

Thanks to the fame of Yanagi Muneyoshi (1889–1961) and his love for Chosŏn white porcelain, we have the impression that Japanese taste concentrated on Chosŏn ceramics.Footnote 99 In reality, Japanese tourists mainly purchased as souvenirs from Korea not Chosŏn white porcelain but Koryŏ celadon, or strictly speaking, Koryŏ celadon reproductions. Chosŏn white porcelain appealed to Yanagi and his circle, who were seeking an aesthetic alternative to the canon of Japanese art ceramics.Footnote 100 Yanagi discovered new aesthetic value within the modest Chosŏn white porcelain used by commoners. Yet these humble everyday objects were too plain to arouse the interest of tourists who were looking for sign value as much as, or more than, aesthetic value in their souvenirs. Appreciating that rustic beauty required the considerable aesthetic discernment which art collectors and aesthetes such as Yanagi possessed. In contrast to the art market’s expansion to Chosŏn white porcelain in the 1930s, the souvenir market continued to be dominated by Koryŏ-style celadon.Footnote 101 The same is true of lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl. While Yanagi and his circle highly praised and enthusiastically collected simple Chosŏn woodworks, Japanese tourists preferred elaborately decorated lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Whereas Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl appeared as signature souvenirs of Korea in almost every tourist guidebook, brochures, and advertisement of souvenir shops, Chosŏn white porcelain and woodworks were rarely introduced in those tourist materials (Figure 13).Footnote 102

Figure 13. Souvenir shop advertisement, Yakushin Chōsen taikan (Teikokutaikansha, 1938).

Koryŏ celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl are two of the most visually distinct genres among Korean crafts and can be readily differentiated from Japanese and Chinese crafts by those who have no great sense of connoisseurship. Like tanch’ŏng and wanjach’ang of Korean architecture, pisaek and sanggam (inlaid decoration) of Korean celadon and najŏn of Korean lacquerware served as a signifier of Koreanness and signalled to Japanese tourists that ‘this is the Korean product’. No matter that new-style lacquerware employed Japanese-favoured motifs, techniques, and objects, these wares were surely seen as Korean in Japanese tourists’ eyes because of najŏn.

During the colonial period, Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl were repeatedly selected as representative of Korean indigenous products on various official occasions. In January 1918, when Korean crown prince Yi Eun (1897–1970) returned to Japan, a package of gifts was sent with him from the Yi royal family to the Japanese imperial family.Footnote 103 According to the Maeil Shinbo, a Koryŏ-style celadon vase produced at Piwŏn and lacquered boxes with mother-of-pearl inlay were included in the gifts presented to the emperor and the empress, respectively.Footnote 104 In January 1929, Governor-General Yamanashi Hanzō (1864–1944) presented Emperor Shōwa (1901–1989) with a Koryŏ-style celadon flower vase and a mother-of-pearl inlay lacquered table to place it on.Footnote 105 The former was produced at Sanwa Kōraiyaki and the latter at the Korean Art Workshop. Lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl was chosen not only as offerings to the Japanese imperial family but also as royal gifts bestowed by the Yi royal family on Japanese colonial government officials who returned to Japan after their tenure in Korea.Footnote 106

Expositions held within and beyond Japan were also a major venue where Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl were recognized as emblematic products of Korea. In 1922 the Peace Commemorative Tokyo Exposition was held in Ueno Park. During the exposition, a ‘Korea Day’ event was held to inform Japanese people about Korea and promote its products, and Korean specialties were given to prize-winners drawn from among visitors of the day. Koryŏ-style celadon vases and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl objects were included among the prizes along with tiger skins and Korean ginseng.Footnote 107 In 1925, the Government-General of Korea submitted Koryŏ-style celadon ware and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl to the ‘Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes’ held in Paris.Footnote 108 Although, like Taiwanese products, these items were displayed in the Japanese section and introduced as a part of the Japanese entries, it is still true that Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl were counted as representative products of colonial Korea. Through the institutional confirmations from imperial gifts to expositions, which were widely reported in the media, Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl occupied a dominant position in the Japanese imagination of Korea.

On the other hand, promotional tourism materials also had a strong influence on the Japanese imagination of Korea. For example, the postcards of an old potter, mentioned earlier, created and circulated the image of Koryŏ-style celadon as authentic Korean goods.Footnote 109 Japanese-run photo studios in Korea printed and sold souvenir photograph albums and picture postcards depicting famous places (meisho) and manners and customs (fūzoku) of Korea.Footnote 110 Once an original copy of a photograph was produced, identical images were reproduced in diverse formats and mediums. In the case of the old potter image, it was first printed as black-and-white photograph postcards, and then reprinted as coloured picture postcards and in envelopes for packaged sets of fūzoku postcards. As indicated on the back of the postcards, multiple publishers and sellers, including Oyoshi Teahouse in Pusan, Umiichi Shōkai in Seoul, and Taishō Shashin Kōgeisho in Wakayama, were engaged in their production and sale. The old Korean potter postcards were distributed via hundreds of retail outlets for decades. Most Japanese tourists encountered Korea first through the stereotyped images of ‘pure Korea’ such as the old potter in promotional tourist materials circulated within Japan. Consequently, Japanese tourists held images of Korea that preceded their experience of Korea and tried to experience in Korea what had been already made familiar to them by these images. The authenticity of their experience of Korea was determined by how close it was to their imagination.

It was Mitsukoshi that ultimately validated the authenticity of Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl sold at its Korean product showroom. Each product was put in a separate box with Mitsukoshi’s seal and label. This certification is derived from hakogaki, an autograph or note of authentication written on a box of unlacquered paulownia, a practice observed in Japanese tea culture. The sign and seal on a box by a tea master guaranteed the quality and provenance of the object within. Mitsukoshi’s own seal and label were crucial in the verification of authenticity of the Korean products inside. This practice provided Japanese tourists with a feeling of security and trust in their shopping for Koryŏ-style celadon and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl. In metropolitan Japan, Mitsukoshi had established a reputation for dealing in arts and artefacts, having done so for many years. Since Mitsukoshi launched its Art section in 1907, it displayed and sold the works of prominent contemporary Japanese artists. In 1921 Mitsukoshi opened its Oriental section and dealt in arts and artefacts from China, Korea, and Southeast Asia. In addition, famous writers’ and scholars’ travelogues of Taiwan, Korea, China, and Manchuria were often published in Mitsukoshi’s house magazines.Footnote 111 Mitsukoshi had supplied customers with not just Oriental arts and artefacts but also cultural and historical information about them. Thus, Japanese tourists considered Mitsukoshi not just a commercial institution but a cultural one as well, one that had the expert knowledge and good taste needed to provide them with authentic Korean arts and artefacts. Keijō Mitsukoshi used its cultural authority to prove the authenticity of ‘Korean products’.

Tomita Gisaku, Umii Benzō, postcard companies, and Mitsukoshi played the role of ‘substitute hosts’, which is a concept Gao Yuan suggested in her study on Japanese tourism to Manchuria in the 1930s.Footnote 112 According to Gao, under the asymmetrical power relations between Japan and Manchuria, the host community (Manchuria) virtually lost the ability to represent itself and Japanese residents of Manchuria curated Manchuria for the guests (Japanese tourists), substituting themselves for the hosts (native Manchurians). Japanese tourism to Korea also flourished amid a disparity of capital (economic, social, and cultural) between native Koreans and Japanese residents of Korea. Economic capital to invest in the revival of Korean traditional crafts, social capital to get support from the Government-General of Korea, and cultural capital to authorize the authenticity of Korean products, all were possessed more by Japanese residents of Korea than by native Koreans. The representation of ‘pure Korea’ was created, codified, and confirmed by ‘substitute hosts’ for guests from the metropole.

Conclusion

With the feeling that I would go to a country far away from civilization, I had not been relieved until I came here [Korea]. Now I am embarrassed for having felt uneasy. Keijō is indeed a modern city. Today I had a shampoo at Mitsukoshi’s beauty shop. In that regard as well, everything is quite the same as in Tokyo.Footnote 113

This passage is cited from an article titled ‘Going to the Korea of White Robes’ that was published in Tabi’s special issue on Korea in July 1935. Keijō, where the Japanese department store operated, is described as a place to be able to live the same modern life that one could expect back in Tokyo. In fact, Japanese tourists could enjoy modern comfort and safety while they were visiting Korea. From the moment they landed at Pusan, they moved by express trains and sightseeing buses or taxis, stayed at Japanese-style inns or modern hotels, and could even get a shampoo at a department store’s beauty shop if they wanted. Nevertheless, Japanese tourists refused to accept that all the evidence of modernity they encountered during their Korea trip belonged to Korea. Within the imagined geography of Japanese tourists, Korea was the land of a non-modern world. ‘Things Korean’ and ‘things modern’ were considered incompatible and mutually exclusive. For Japanese tourists, who did not or could not accept the landscape of Keijō with the Neo-Renaissance style Mitsukoshi building as ‘pure Korea’, Keijō Mitsukoshi constructed a kind of ‘enclave of Korea’ within its store. That was the Korean Product Showroom.

MacCannell argued that ‘the best indication of the final victory of modernity over other socio-cultural arrangements is not the disappearance of the non-modern world but its artificial preservation and reconstruction in modern society’.Footnote 114 Japanese tourists from the metropole desired to experience a pristine and immutable Korea, and Japanese residents of Korea produced and offered a vision of ‘pure Korea’ through a matrix of representations from picture postcards to souvenir shops. ‘Korean style’ and ‘Korean products’ were Koreanized within that matrix.

If the ‘Korean style’ and ‘Korean products’ were inauthentic, it was not because they were distorted and Japanized with the intention to destroy Korean indigenous culture, but because the desire for ‘pure Korea’ was paradoxical. Japanese longing for the non-modern world was the very sign of Japan’s modernity, which was sustained by its colonization of Korea. That is to say, the desire for ‘pure Korea’ arose only after Korea was lost. ‘Pure Korea’ did not exist prior to that desire, but was constructed by that paradoxical desire.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by 2015 SNUAC Research Grant for Asian Studies.