While some readers of Chaucer fretted over the archaic and potentially faulty words borne in manuscript books, others were worried by the missing leaves and textual gaps that plagued their copies. In the books considered here, the belated interpolation of missing words, lines, and whole leaves suggests a pursuit of bibliographical and narrative closure for Chaucer’s oeuvre. At the same time, this type of book use is always reliant on the creative engagement of those who continue, complete, and perfect these works, and on an understanding of the codex as open to such change and transformation. The desire for closure in the Chaucerian book begins, unsurprisingly, with its first makers, who had long sought the poet’s works in their most complete state, a scholarly quest energised by the seemingly unfinished nature of several of his works.Footnote 1 Working from an incomplete exemplar, the scribe of the earliest surviving copies of the Canterbury Tales anticipated an ending for the incomplete Cook’s Tale by leaving blank space on the page for its conclusion to be filled in.Footnote 2 In other manuscripts of the Tales, some scribes improvised to create an effect of completeness – by omitting the Cook’s Tale altogether, by supplying other spurious lines, and, most commonly, by compensating for the absence by adding the apocryphal Tale of Gamelyn immediately after the Cook’s fragment, where it is linked as ‘another tale of the same cooke’, according to one manuscript.Footnote 3 These decisions reveal the fixes devised by Chaucer’s earliest critics when they were confronted by the instability of his oeuvre, and capture the pursuit of completeness on the page.Footnote 4

The early printers, too, discovered inconvenient gaps in the material remains of Chaucer’s works. Famously, Caxton, who could ‘fynde nomore’ of the House of Fame when he came to publish his 1483 edition, composed and printed twelve lines to conclude the poem.Footnote 5 In de Worde’s 1498 edition of the Tales, the incomplete Squire’s Tale, which trails off abruptly near the beginning of a new section in the narrative, was followed by an earnest note from the printer: ‘There can be founde no more of this forsayd tale. whyche I have ryght dilygently serchyd in many dyuers scopyes’.Footnote 6 Later recycled in Thynne’s influential edition, de Worde’s note about the missing end to the Squire’s Tale would be disseminated in each successive print until the eighteenth century. Faced with the variability of a literary legacy in manuscript, Chaucer’s early printers were thus ‘led to systematize [the earlier] intermittent ad hoc strategies for dealing with the problem of completeness’.Footnote 7 In Thynne’s case, the appropriation of the earlier printer’s comment caused his son Francis to avow that his father had ‘made greate serche for copies to perfecte his woorkes, as apperethe in the end of the squiers tale’.Footnote 8 The Squire’s Tale would be acknowledged as incomplete for centuries to come, but the fiction of completeness remained fundamental to the commercial enterprise of editing and publishing Chaucer. Although they were prone to inheriting spurious lines or gaps from their manuscript exemplars, the printed editions could profess to present the text in an improved and expanded state – not ‘in leues all to-torne’, as printer Robert Copland imagined the Chaucerian manuscript book, but one sold in newly printed authoritative editions. As we have seen, the successive printed volumes of Chaucer’s collected Workes pursued an ideal of definitiveness. It is an aspiration conveyed as much in their claims of novelty and fidelity to what Chaucer wrote as in the material heft of the large folios produced by Thynne and the later editors.Footnote 9 Speght’s declaration in the 1602 dedication that he has ‘reformed the whole Worke’ using a combination of manuscript and print witnesses encapsulates this sense of his own edition’s reliability and thoroughness.Footnote 10 That desire for textual and bibliographical completeness is founded on a conception of the Chaucerian oeuvre as a known and recoverable entity, capable of being accessed, copied, contained, and preserved in books. Joseph A. Dane has pointed out that the semblance of stability in the entity he calls the Chaucer book is ultimately illusory given its ‘problematic multiplicity’ in thousands of surviving copies.Footnote 11 This might be so from the vantage point of the modern bibliographer, yet the fact that early modern readers hand-reproduced printed texts in order to repair and restore older copies shows that they invested the idea of the Chaucer book with some degree of textual stability. For all print’s susceptibility to variance, the impression of its reliability and near-completeness was one actively cultivated by the printers, stationers, and editors responsible for making new books of Chaucer’s works, and who announced that they had ‘repair’d / And added moe’ to his fragmented corpus.Footnote 12 The success of their venture is evident in the early modern use of printed books as a model for supplying the unsatisfying gaps, blanks, erasures, and lacunae found in old copies. The book’s ability to be reshaped and repaired in the ways surveyed by this chapter is predicated on its openness to change – to destruction as well as improvement. Although these repairers of manuscripts pursued an ideal of textual fixity inherited from print, their variability brings them back in line with Dane’s assertion of each copy’s singularity – it is only amplified in the perfected and completed volumes under consideration here, for every book’s individualised programme of completion and repair makes it all the more unique. This ability of the codex to tolerate seemingly endless additions and completions suggests that the form of the book might render it, for all the efforts of Chaucer’s perfecting early readers, ‘a constitutively incomplete and unfinishable object’.Footnote 13

The present chapter tracks the historical convergence of incomplete Chaucerian texts in manuscript with the seemingly authoritative printed copies that followed them. Its subjects of interest are the material and textual absences that early modern readers found in early Chaucerian books, the measures they took to fill them, and the attitudes to Chaucer and his books that lay behind such acts. This impulse to complete and perfect was roused not only by conspicuously unfinished or damaged works but also by more innocuous absences: the gaps left during copying, or blank spaces allotted for decoration. Blank space, as Laurie Maguire has argued, ‘activates the reader’s restorative critical instincts’, and such absence spurs the modes of perfecting considered in this chapter.Footnote 14 The means and methods of repair carried out by later book owners in their ‘torne’ and ruptured manuscripts exposes contemporary concerns with the integrity and preservation of Chaucer’s oeuvre, thereby positioning repair as one of the most revealing forms of perfecting undertaken by his early modern readers.

2.1 Mutilated Manuscripts

The volumes under discussion were carefully repaired in this later period but like many medieval books, they had all been previously despoiled or damaged through neglect.Footnote 15 Before they were valued as old and rare copies of Chaucer’s writing, some copies were prized for the attractive decorative art most prominently on display in their borders and which likely served as motivation for their removal.Footnote 16 Beyond their susceptibility to iconoclasm, old books were subject to destructive household and commercial uses and to the ravages of time.Footnote 17 In particular, the durability of parchment saw manuscripts repurposed for myriad material purposes. Christopher de Hamel has shown that the use of discarded vellum as a structural reinforcement for European bindings has been in practice for over a millennium, and long before the introduction of moveable type.Footnote 18 Parchment fragments from European medieval manuscripts have been found strengthening bindings, wrapping the goods sold by grocers, and repurposed as stiffening material for clothing in later periods.Footnote 19 Such habits of book-breaking gathered momentum during the Reformations of the sixteenth century, a period marked by iconoclastic fervour and suspicion of the material remains of the medieval past.Footnote 20 During the sixteenth century, images cut from manuscripts might be pasted in to serve as up-market adornment in devotional printed books, while discarded parchment sheets might elsewhere serve as cheap wrappers for newly printed books in bookbinders’ shops. Some enthusiasts, like Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), who was furnished with samples of ancient handwriting snipped from two early Gospel books at Durham Cathedral, collected manuscript fragments for their palaeographical interest.Footnote 21 The bookseller and collector John Bagford (d. 1716), motivated by an interest in the history of scripts and typography, compiled, sold, and gifted fragments of medieval and rare early printed books (sometimes whole albums of them) to his associates and clients, including Humfrey Wanley, Hans Sloane, and Pepys himself.Footnote 22 The majority of Bagford’s manuscript fragments seem to have been obtained from binding waste created from books that were cut up in the sixteenth century.Footnote 23

John Manly and Edith Rickert, together responsible for the eight-volume editorial feat titled The Text of the Canterbury Tales Studied on the Basis of All Known Manuscripts (1940), had a choice word for such books and their texts: ‘mutilated’.Footnote 24 It is a word uncomfortable to modern ears for its connotations of physical brutality, but one they used to describe the state of many of the manuscript books this chapter will discuss. Within the lexicon of the book world, where it has resided for hundreds of years, ‘mutilated’ takes on a more benign appearance. But the word and others like it reveal a deeper obsession with bibliographical completeness that has long been present in language which figures the book as a human body. If (as this book’s Introduction lays out) the Latin imperfectus denotes a body which is not in its complete and fully realised state, mutilus is its more terrible twin, used to describe those bodies that have been made imperfect through absence or excision of some part.Footnote 25 In the early modern period, to mutilate was ‘To make Vnperfect’, as a sixteenth-century English-Latin lexicon records. ‘Imperfectus’, meanwhile, was listed in that dictionary as a synonym for ‘Vnperfect, maimed, or wanting some thing’.Footnote 26

Religious, classical, and literary books, texts, and canons of work could all be appraised according to this vocabulary of bodily perfection and mutilation. Leah Whittington locates the genesis of this idea in the language of the Italian humanists who, surveying the incomplete volumes that transmitted an impoverished record of the totality of Greek and Roman learning, ‘turn[ed] to metaphors of mutilation to register their grief and indignation, and to announce their project of cultural reconstruction’.Footnote 27 Completing, like correcting, was a philological endeavour bound up with the humanists’ agenda of historical recovery. And as with the practices of emendation and castigatio, the project of textual repair was pitched in morally freighted terms: integrity, virtue, and dignity.Footnote 28 In English, it was a lexicon available to the recusant Catholic William Reynolds when he denounced the Calvinists for introducing into Luther’s works

the most filthy mutations and corruptions … In one place some wordes are taken away, in an other many mo, some where whole paragraphs are lopte of … Where Luther doth reproue the Sacramentaries, there especially those falsifiers tooke to them selues libertie to mutilate, to take away, to blotte out and change.Footnote 29

In Reynolds’s view, this textual violence mounted a challenge to both theological and historical verity. John Healey, in his translation of Augustine’s Of the citie of God (1610), describes Cicero’s De Fato as ‘wonderfully [i.e. exceedingly] mutilate, and defectiue as we haue it now’.Footnote 30 An inverted invocation of the same trope appears in Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623), whose plays are proclaimed in the prefatory epistle to be ‘cur’d, and perfect of their limbes … as he conceived them’.Footnote 31 These images hearken, too, to a longer tradition of likening the human body to the book and other material texts. Richard de Bury’s image of the fire at Alexandria’s library as ‘a hapless holocaust where ink is offered up instead of blood’ and the archetypal description of Christ’s crucified body as a charter are prominent late medieval appearances of the conceit.Footnote 32 Like bodies, old books in that period could be described as ‘aged and worn out’ (vetere et debili), as falling apart (caducus), headless (acephalus), or grey with age (‘for aege all hoore’).Footnote 33 In their tendency to deteriorate with time, books were similar to bodies according to this worldview – and like a person, a mutilated book was fundamentally imperfect.

When Manly and Rickert classified Chaucerian manuscripts as mutilated, or when historical readers described old books by analogous terms – mangled, lopped off, cut to pieces, dismembered, or imperfect – they were thinking about them in terms of the completeness that they lacked, and imagining them relative to other, ideal books.Footnote 34 Books could be messy and imperfect, but this is not a state that most readers desired for them. As Copland’s description of an ‘al to-torne’ Chaucerian book suggests, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries inherited manuscripts in varying states of deterioration and neglect. Even after manuscript books had outworn their welcome as reading material, their illuminations were prized as decoration, and often excised.Footnote 35 One such purloining of a painted Chaucer portrait from a fifteenth-century manuscript of Hoccleve’s Regement provoked the ire of a reader in the sixteenth century, who subsequently inscribed two stanzas of doggerel verse onto the same page:

With some wit, the verses memorialise the absent ‘pickture’ and ‘worthy Chaucer’ himself. Their real subject, however, is the ‘Furyous Foole’ who did the ‘deed’. The culprit is figured as a moral and intellectual antithesis to the benevolent Chaucer; while the poet ‘much did wryght’, the despoiler of this book wrought only destruction.Footnote 37 Righteous outrage at the dismemberment of medieval manuscripts, it turns out, is a great Chaucerian tradition. Describing the same lines in the last century, Derek Brewer could not help but concur: ‘All readers will echo the sentiments expressed by the infuriated sixteenth-century reader’.Footnote 38 Early in the eighteenth century, John Urry noted of another imperfect manuscript of the Canterbury Tales that ‘It has been a noble book, but by some wicked hand many of the leaves are cutt out in diverse places of the book’.Footnote 39 Of CUL, MS Gg.4.27 (later discussed), Urry wrote that it is ‘a very fine book’ but laments the loss of many leaves and its pilgrim-figures, ‘which I have not seen in any other MS of this author, & doubtless were once all there, but the childishness of some people has robbed us of them’. The perpetrators of this destruction are, in such accounts, ‘childish’, ‘wicked’, and ‘Foole[s]’. In truth, there are many reasons for historical readers to have cut up old books; not all of them are malicious and some were even aimed at preservation.Footnote 40 Such terms, however, reflect an often rash moral judgement of the people who cut images and leaves from old books, and one which was implicitly projected onto the imperfect books themselves.

While the language of mutilation implied the moral failure of those responsible for the act, the damaged volume itself was frequently allied not with the perpetrator but with the book’s creator. Thus, the book became a metonymic representation of the author’s physical body and of their body of work.Footnote 41 To mutilate any individual copy was also to rupture the integrity of the author’s whole corpus – a threat literalised in the clipping out of Chaucer’s painted portrait from the Regement manuscript. This figural association between the individual copy and the author’s entire body of writing undergirds the anxiety discernible in the comments on the mutilated works of Luther and Cicero and lent further urgency to the project of textual repair. For such authors, as for Chaucer, the worry about the fragmentation of their works is informed by an appreciation of their historicity and cultural significance. All the works Chaucer ‘did wryght’ make him ‘worthy’, but the earliest copies risked slipping into neglect and disrepair. Historians of the medieval and early modern book have already begun to reckon with, survey, and theorise the loss, destruction, and archival absences that occupy the penumbra of their area of study. Accounts of pre-modern mending, repair, and other programmes of preservation before the nineteenth century are fewer, but these acts – the subject of this chapter – constitute a prehistory of bibliographical conservation and a worthy complement to the expanding history of book loss.Footnote 42 Supplying missing text copied from readily available printed editions onto new (or newly furnished) leaves was one means of perfecting incomplete manuscript copies, but one whose motives and methods have not yet been fully accounted for or theorised.

If printed volumes did not explicitly purport to be an exhaustive repository of all that the poet wrote, they were nonetheless positioned as the authoritative record of the corpus of diverse Chaucerian works rescued from oblivion. No surviving medieval manuscript (not even Holland’s Gg) ever made the same claim. Enterprising early modern readers thus seized the opportunity to repair and complete texts contained in medieval manuscripts according to their newer printed counterparts. For Chaucer’s works, print culture became not only the mode of their dissemination in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but an unexpected contributor to their restoration and survival in earlier manuscript copies.

2.2 Supplying Lost Leaves

Perhaps the best-known case of the destruction and repair of a Chaucer manuscript is that of CUL, MS Gg.4.27, the Cambridge copy described by Urry as ‘very fine’. It is a justifiably famous collection which contains a greater number of Chaucer’s works than any other manuscript, and a copy unique for its combination of minor poems – the Legend of Good Women, the House of Fame, and the Parliament of Fowles – with the more substantial Troilus and the Canterbury Tales.Footnote 43 In addition to its role as a witness to early canon formation, the manuscript is distinguished by an elaborate programme of illustration and decoration, again unique amongst Chaucer manuscripts. In its original state, the book contained at least one, and possibly two, full-page illustrations.Footnote 44 It was decorated with borders to mark major textual breaks, including the beginning of every tale and prologue, and illustrated with pilgrim portraits and with depictions of Vices and Virtues from the Parson’s Tale. Many of the book’s illustrations were removed sometime before the end of the sixteenth century, taking with them significant sections of the text written on the corresponding leaves. Malcolm Parkes and Richard Beadle have suggested the possibility that the illuminations were removed for the sake of preservation (rather than on the ‘childish’ whims condemned by Urry) and that, having safeguarded its most precious parts, ‘The rest of the manuscript could be discarded since from 1532 onwards virtually all the texts in this volume would have been available in print’.Footnote 45

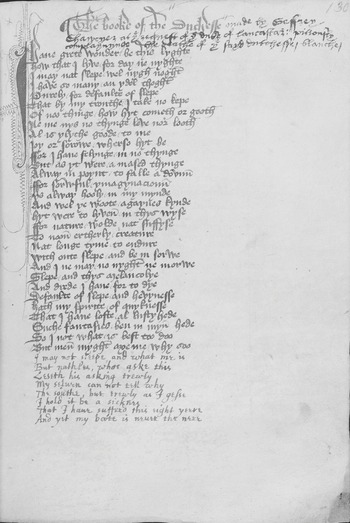

Joseph Holland, the antiquary who owned the manuscript around 1600, had other ideas.Footnote 46 Although nothing definitive is known of the book’s provenance before that date, the details of its repair and embellishment under Holland’s instruction have been thoroughly documented.Footnote 47 Far from confirming the obsolescence of the plundered manuscript book, the printed editions that Holland had at his disposal provided the means for its restoration. Holland’s project of perfecting the damaged manuscript included supplying the text lost during the removal of the book’s pilgrim portraits and illuminated borders. When he inherited it, the beginnings of a group of lyrics, the five books of Troilus, the General Prologue, and the introductions of many individual tales all lacked their medieval leaves.Footnote 48 Copying from Speght’s 1598 edition, Holland’s scribe supplied the opening section of Troilus and Criseyde (1.1–70) and multiple missing sections in the Canterbury Tales, which were inserted into the manuscript on a series of eighteen parchment supply leaves in a stylish and extremely neat italic hand (see Figure 2.1).Footnote 49 Holland’s perfecting of Gg went considerably beyond the repair of its ruptured text – extending to cleaning its annotated margins, and adding new literary and biographical material about Chaucer – but I am concerned here with the most glaring signs of the book’s incompleteness, and his intention to fill them in.Footnote 50 In this context, the choice of writing support is telling for, as Cook observes, the use of parchment ‘suggests a specific investment in the unity of the book itself’.Footnote 51 For Holland, who rightly identified Gg.4.27 as a historically important attempt to collect Chaucer’s works in a single codex, the decision to perfect it through consultation with the latest Speght edition was an astute one. Like Speght’s Workes, Holland’s manuscript aspired to a degree of completeness. Its integrity was threatened by the earlier excisions it had borne, and the repairs undertaken by Holland were an attempt at setting this right. For instance, the supply leaf which replaces the lost opening leaf to Troilus and Criseyde is headed ‘The fiue Bookes of Troilus and Creseide’, a title not matched by the printed edition (where the incipit heralds only ‘The Booke of Troilus and Creseide’),Footnote 52 as though the person who made these repairs wished to emphasise the contiguity of the first supplied leaf with what follows. The scribe also smoothed over the inevitably sharp transitions between the early modern and medieval hands by adding catchwords and incipits, drawing attention to the repairs and highlighting the book’s newly restored status. As Cook notes, the bright blue ink used for this purpose may have been a choice designed to echo the book’s surviving decoration.Footnote 53

Holland understood that textual integrity was essential to the project of historical preservation, and he expended considerable resources and effort to this end. A glance at some of the other books he had copied and completed illustrates the importance he attached to the idea of repair. A sixteenth-century manuscript now held at the British Library contains a collection of painted arms executed by Holland. This book is a copy of rolls of arms for Devonshire and Cornwall produced during the fifteenth century. On the inside back cover of his own transcript, Holland (who was himself from Devon) recorded the source of his copy and gave a reason for this work in a note dated 1584: ‘because manie of their names are almoste worne out [in the original], I haue sett them downe agayne / as neere as I can according to the auncient writinge’.Footnote 54 As Holland tells it, the primary motivation for collecting this historical material was not possession, but preservation. Another of his manuscripts, now in the College of Arms, is a fourteenth-century copy of The Seege of Troye and a purported translation of Historia regum Brittaniae.Footnote 55 But like his Chaucer, that manuscript was incomplete, so Holland supplied the wanting text on an additional paper leaf and dutifully recorded his intervention in a note dated 1588. Having noticed that ‘the end of this booke is imperfect’, he wrote, he subjected it to close examination against ‘an auncient originale written in lattine by Gefferay of Monmouth de gestis Britonum; (out of the which this semeth to be Translated)’, and ‘thought it good to make this addition out of the sayd Gefferay of Monmouth’.Footnote 56 Although these interventions date from more than a decade prior to Holland’s remodelling of Gg, they reveal him to be concerned with the same practices of transcription, collation, and repair seen in his Chaucer and reflect a concern with historical preservation that would be a lifelong preoccupation.Footnote 57 The leaves that he supplied to Gg achieve a similar end, by mending Chaucerian texts which were in danger of becoming fragmented.Footnote 58 In light of his commitment to repairing old books, it is significant that Holland used the Latin word procurare – meaning ‘To see to, or to take heede of a thyng: to chearishe: to keepe’ – to describe his relationship to the splendidly illuminated Lovell Lectionary, an early fifteenth-century book he owned and which he saw as a type of family heirloom.Footnote 59

Gg.4.27 is exceptional for the scope achieved by those who initially conceived it, and Holland’s additions show that he recognised its attempt at assembling Chaucer’s works. But damaged Chaucerian manuscripts of less ambitious sorts also inspired similar programmes of perfecting through the supplying of missing leaves bearing text copied from print. Another manuscript book, Bodl. MS Laud Misc. 600 (henceforth Ld1), is a copy of the Canterbury Tales from around the middle of the fifteenth century. According to Manly and Rickert, it was ‘[o]riginally a rather expensive MS’, but its condition had deteriorated by the early seventeenth century, when it came into the hands of John Barkham (1571/2–1642), an antiquary and clergyman who would eventually gift the book to Archbishop William Laud in 1635. Around this time, and most likely under Barkham’s direction, eighteen parchment leaves were supplied to repair some of those missing in the book, and an additional leaf for a table of contents was added.Footnote 60 Transcribing the lost text from a printed copy of Chaucer, probably the 1602 edition, the early modern scribe wrote in black ink and produced a tidy if laboured imitation of the secretary hand written by the original scribe (see Figure 2.2).Footnote 61

This seventeenth-century approximation of the book’s original aesthetic extends to the new decoration, where flourished initials, running heads, and paraf signs have been carefully executed by the scribe in a style generally compatible with the rest of the book. The same may not be said of the new colour scheme, which has been described as ‘a crude imitation … of the original decoration, but in red, yellow, and black’.Footnote 62 Despite these incongruities, it is clear that considerable effort was expended in the process of repairing the damaged medieval book that would become Ld1. For a volume that was ‘evidently in very bad condition’, the procurement of parchment, the thorough cleaning of the medieval leaves, the supplying of missing text and decoration, and its new leather binding show that the book was subjected to a scheme of perfecting by its early modern owner in preparation for its presentation to Laud.Footnote 63 Together with the three other manuscripts and a collection of coins which he presented to the Archbishop around the same time, Barkham’s gift of the newly repaired Canterbury Tales volume was designed to appeal to Laud’s historical interests as a collector, possibly in the hope of securing preferment.Footnote 64 As a Latin inscription to Laud signed by Barkham on fol. 1v indicates, the gift functioned as a type of presentation copy – not of a literary work written by Barkham himself, but one whose repair he commissioned as a token of the friendship and shared interests of the two antiquaries.Footnote 65

While Holland saw the repairing of Gg’s missing text as an opportunity to supplement it with material about Chaucer’s life and canon which he had seen published in the printed volume, Barkham’s means of improving the condition of Ld1 involved restoring the book to a state near its original. Although both men used the latest printed edition to perfect their respective manuscripts, the final products show two varying materialisations of what a complete Chaucerian book could be. For Holland, the book should be as capacious as possible, accommodating not only additional Chaucerian content, but also a medieval fragment which he saw as belonging to the same broad historical period and to the same vernacular literary tradition.Footnote 66 Meanwhile, Barkham’s cleaned-up and polished copy of the Canterbury Tales for Laud reveals an imitative quest for authenticity cultivated in the writing support, archaising script, decoration, and mise-en-page adopted by the manuscript’s new scribe. His additions show that he wished to preserve some visual elements particular to the medieval manuscript book, but used the printed copy as a means of improving its text. In each case, the use of supply leaves to effect repairs in damaged manuscripts exposes the bibliographical ideals of those who oversaw these efforts of completion.

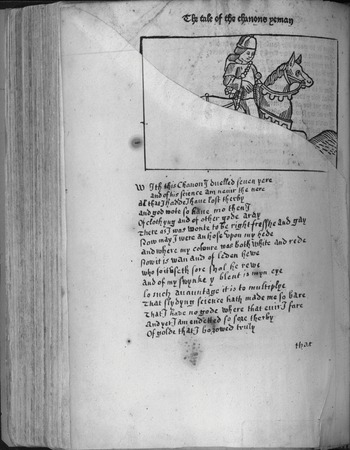

Although Barkham’s restored Canterbury Tales approximates the aesthetic of a fifteenth-century manuscript, that volume nonetheless preserves further evidence of print’s impact on the idea of the Chaucer canon. One of the leaves added to Ld1 in the seventeenth century (fol. iir) now bears two columns of text written in a contemporary hand, possibly that of Barkham himself (see Figure 2.3).Footnote 67 The first, left-hand column is headed ‘The order of this book MS’ and consists of a numbered list of the volume’s contents, beginning with ‘1. The Prologues of the Author’ and ending with ‘25. The Parson’. The second, right-hand column is titled ‘The order of the Printed’ and contains another numbered list of tales as they appear in Speght’s edition, which does not wholly correspond to that of Ld1. For the person who drew up this table, ‘the Printed’ volume provided a benchmark by which the older book could be measured. Notes surrounding the two columns on the same page witness a rare moment of reading early modern print and a medieval manuscript in parallel.

Ld1 also contains the spurious Tale of Gamelyn, introduced in the original scribe’s incipit as the Cook’s main contribution to the storytelling game: ‘Here begynneth the Cokes tale Gamelyn’.Footnote 68 To accommodate this interpolated tale in the frame narrative, the manuscript treats the fragment that is now called the Cook’s Tale (about an apprentice named Perkyn Revelour) merely as a ‘prolog’ to Gamelyn.Footnote 69 The seventeenth-century annotator observed the importance of Gamelyn in a marginal note beside the table of contents: ‘This Tale of the Cooke, is perfect in this MS. but the Publisher of the Printed, hath omitted it, supposing it has been lost. vide f.16 of the printed’.Footnote 70 Indeed, the early editions before Urry did not include Gamelyn, but those of Speght do comment on the unfinished status of the Cook’s Tale of Perkyn Revelour: ‘The most of this Tale is lost, or else neuer finished by the Authour’. In Speght’s 1602 edition, this note is printed on the verso of ‘Fol. 16’, the same page cited by the creator of the manuscript’s table of contents when he cross-referenced his book with ‘the Printed’.Footnote 71 It is clear that the annotator, following the scribal incipit that refers to ‘the Cokes tale Gamelyn’, assumed Gamelyn to be the missing bit of the Cook’s Tale which Speght had deemed ‘lost’. The marginal note conveys a certain pride that the tale ‘omitted’ from the printed edition was ‘perfect in this MS’, his own copy of Chaucer.

Beside the table of contents, another set of notes written in the same hand weighs up the manuscript’s completeness in relation to Speght. Here, after the listing for the Franklin’s Tale, the annotator has observed that ‘All the rest [of the tales] are in the same order in both Bookes’, with one exception:

Only the Plowman’s Tale, is not MS. & if it were Chaucers, it was ^left out of his Canterbury Tales, for the tartnes against the Popish clergie. It is very probable yt it was severally written by Chaucer, & not as one of the Tales, wch were supposed to be spoken & not written

The Plowman’s Tale, a satire against the clergy, had appeared in copies of Chaucer’s Workes since Thynne’s 1542 edition and was accepted during the early modern period as a genuine addition to the Canterbury Tales. But this reader of Ld1 concludes that the purported origins of the Plowman’s Tale in writing deviate from the orality fundamental to the premise of the Canterbury Tales. He observes of the Plowman’s Tale that ‘The same word of writeing is there vsed diuers times’, citing examples, and concludes that ‘it was not deliuered as a Tale told by mouth as all the rest were’. Barkham is known to have been a learned antiquary and it is likely that the hand is his; if so, he shows better judgement of Chaucer’s canon than Speght himself, who believed the Plowman’s Tale to be ‘made no doubt by Chaucer, with the rest of the Tales. For I haue seene it in written hand in Iohn Stowes Librarie in a booke of such antiquitie, as seemeth to haue been written neare to Chaucers time’.Footnote 72 The seventeenth-century annotator of Ld1 doubts this straightforward history, suggesting instead that the tale was written separately by Chaucer and excluded from the Canterbury Tales due to its anticlerical content. Speght had claimed that a copy of the Plowman’s Tale ‘in written hand’ was proof of its Chaucerian origin, but Barkham’s copy, in which it was ‘left out’, provides grounds for the clergyman to speculate that the text may have had a separate origin.

Each of these comments on the transmission of the Plowman’s Tale and Gamelyn captures this annotator’s efforts to delineate the borders of the Chaucerian canon and to assess the completeness of his manuscript – an endeavour enabled by the existence of multiple versions of the Tales in written and printed copies. Quite conveniently for Barkham, his book is determined to be superior on both counts, containing what was assumed to be a full copy of the Cook’s Tale, and excluding the incongruous Plowman’s Tale. This attentiveness to the transmission history of the Canterbury Tales and the implied orality of the pilgrimage frame show a critical appraisal of Speght’s printed edition in relation to its manuscript counterpart. Barkham’s desire to repair the book for presentation to the Archbishop, it would seem, was not guided by solely aesthetic concerns for the torn volume, but also by a concern for the textual integrity of a book which he already deemed to be ‘perfect’ in several respects.Footnote 73 So successful was this project of repairing Ld1 that the manuscript was later used as an exemplar to supplement the text of another manuscript.Footnote 74 For both Holland and Barkham, recently printed copies of Chaucer’s Workes allowed them to transform their damaged manuscript books into objects of aesthetic as well as historical value, suitable to be cherished by their owners or gifted to a worthy recipient.

Another manuscript of the Tales which benefitted from codicological repair in the early modern period was TCC, MS R.3.15 (hereafter Tc2), a late fifteenth-century paper copy likely associated with Archbishop Matthew Parker and once owned by Thomas Neville (1548–1615), former Master of Trinity College in Cambridge.Footnote 75 Noticing that the text began abruptly, halfway through the description of the Knight (1.56), someone furnished paper leaves and copied the missing lines (1.1–55) under the newly supplied headings of ‘The Prologues’ (1.1–42, fol. 3v) and ‘The Knight’ (1.43–55, fol. 4av). It may have been Nevile (who bequeathed the book to Trinity) or a Parker associate who carried out this work but whoever it was wrote in a fluent secretary hand with sixteenth-century features.Footnote 76 They began the Knight’s Tale halfway down a fresh page so it would join up more smoothly with the medieval text’s continuation of that tale on fol. 5r (1.56 ff.) (see Figure 2.4). There are other leaves missing from this copy (gaps which also result in loss of text) but only the first two were replaced by the early modern copyist, who also copied the additional items that were placed at the beginning and end of the book.Footnote 77 Here, the principal concern for the integrity of the Tales was limited to its opening, where the lost text was plainly visible at the head of the volume.

Bodl. MS Laud Misc. 739 (Ld2) is a late and plainer manuscript of the Canterbury Tales, but one in which an early modern codicological repair also survives. This book contains more than 450 individual corrections to the Middle English text, generally concentrated in a few tales.Footnote 78 At the end of the Wife of Bath’s Prologue, however, appears a tipped-in leaf (fol. 140ar) on which a set of twenty-eight lines which were omitted by the original scribe – and known as the ‘words between the Summoner and the Friar’ – have been supplied (see Figure 2.5).Footnote 79 They appear to have been transcribed from Caxton’s first edition.Footnote 80 The writing support chosen for the job was vellum; on the verso of the supplied leaf is the text of a thirteenth-century treatise on canon law. The physical dimensions of this fragment enlisted to serve as a replacement leaf are noticeably smaller than the manuscript’s other leaves, but its comparative flimsiness might signal not parsimoniousness but the substantial difficulty of obtaining medieval vellum for copying. Despite such evident effort, the work of perfecting this book is itself incomplete. The version of the Summoner’s Tale in this copy is a truncated form also found in a handful of other manuscripts, in which the text ends at l. 2158 and an additional four spurious lines provide a narrative transition to the Clerk’s Prologue. Observing this discrepancy between Ld2 and the printed copy that was evidently at hand, the early modern annotator crossed out the four spurious lines, drew an arrow towards this cancelled text, and noted instead the absence of two leaves (‘Hic desunt 2 folia’).Footnote 81 Unlike the lines missing in the Wife of Bath’s Prologue, they did not (or could not) supply these missing leaves.

The work of perfecting a book by supplying missing text, as such examples illustrate, could itself be left unfinished in some copies. But the fact that the completing of medieval manuscripts was sometimes attempted piecemeal is a reminder of the exceptional and purposeful nature of these efforts. The process of sourcing exemplars, materials, and copyists for the making of manuscript supply leaves (especially those written on parchment) was neither easy nor inexpensive. Even those cases where only some missing parts of the text were repaired – for example, the Wife of Bath’s Prologue at the expense of the Summoner’s Tale, or the beginning of the Canterbury Tales rather than leaves in the middle of the book – reveal something about early modern taste and judgement. In Ld2, not only do the newly supplied lines offer a smooth transition to the Wife’s Tale, which immediately follows, but they also sow the narrative seeds for the bitter animus between the Friar and the Summoner which will later be developed in their own respective tales.Footnote 82 While the replacement leaves surveyed here represent varying degrees of planning, improvisation, and execution, they all show the attempts of early modern readers to compensate for material absences in a range of manuscript books, normally by completing them with text copied from printed editions. If manuscripts are considered in the context of their textual lacunae, it is not surprising that early modern readers of Chaucer should have relied on print for access to complete and authoritative versions of the text. This evidence of the use of print to repair and complete such books revises the assumption (pace Parkes and Beadle) that a damaged and incomplete Chaucer manuscript ‘could be discarded … from 1532 onwards’. Instead, it shows that the existence and accessibility of printed copies of Chaucer did not hasten the obsolescence of manuscripts, but enabled their repair, preservation, and continued use at the hands of new readers.

It is worth noting that the spirit of renovation and repair which such supply leaves expose was not unique to readers who consulted manuscripts alongside print. Lichfield Cathedral Library, MS 29, a Canterbury Tales manuscript copied around 1430, contains four parchment replacement leaves that were added in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. This book was part of a bequest of 1,000 volumes made to the Cathedral by Frances Seymour, Duchess of Somerset in 1673.Footnote 83 Leaves are missing from the beginning of the General Prologue (fol. 1), and from other moments of transition in the frame narrative; two were the outer leaves of their respective quires, while three were internal. The book’s tight binding makes it difficult to determine whether these losses were accidental or deliberate (or some combination of the two), but it is a virtual certainty that all of the lost leaves were accompanied by the vivid decoration seen in the illuminated initials and borders elsewhere in the manuscript.Footnote 84 The additional lost leaves marked changes of action from the Squire’s Tale to Merchant’s Prologue (fol. 93), from the Friar’s Prologue to the Friar’s Tale (fol. 125), from the Prologue of Sir Thopas to the Tale that follows it (fol. 206), and from the Host’s interruption of the Tale of Sir Thopas and the opening to Chaucer’s Tale of Melibee (fol. 209). All but the lattermost of these five leaves have been replaced by early modern supply leaves.Footnote 85

These four leaves have been tipped in, ‘usually on to the small remnants of the lost leaves’.Footnote 86 And intriguingly, the person who copied these leaves for the Lichfield manuscript in the early modern period may have used another manuscript, not a printed edition, as a source.Footnote 87 With characteristic candour, Manly and Rickert determined that ‘The supplied leaves … show a feeble and unsuccessful attempt to imitate the original writing, with crude ornament in crimson ink’.Footnote 88 While the early modern leaves in Gg and in Ld1 seem to have been professionally and meticulously copied and decorated (in italic and an archaising style respectively), the mixed, sometimes hasty, hand of Lichfield’s supply leaves does not make such concessions to the book’s original anglicana script (see Figure 2.6). But if the copying and decoration lack finesse in their execution, the whole project was nonetheless motivated by great care, evident in the procurement, pricking, and ruling of the new parchment leaves, and in the rendering of running heads and initial words in red ink. As in Holland’s Gg, an interest in restoring the book’s visual as well as textual integrity is evident in other details which create an effect of continuity across the fifteenth-century leaves and the early modern additions. The carefully portioned margins, number of lines per page, rubricated running heads, incipits, and explicits all deliberately mirror the mise-en-page of the book’s original leaves. It is in this sense that such old books might be considered perfected – not because their later repairs blend in seamlessly with the original leaves (for they do not), but because the books were subject to effortful, sometimes intensive programmes of repair in order to supply their missing parts. The early modern supply leaves in a book like the Lichfield Canterbury Tales thus underline a desire for bibliographic completeness which was common to many readers of medieval manuscripts, whether or not they completed their books using printed exemplars.

As might be expected, the early modern intention to mend old books with newly supplied leaves was not particular to manuscripts either. Like the fifteenth-century manuscripts which are the focus of this book, the oldest printed books were sometimes subject to the same fate of destruction and repair. There is evidence of this practice in the Pepys collection, which in the late seventeenth century held incunabula containing missing leaves. Clerks were duly tasked with copying new transcriptions to replace lost parts of these texts.Footnote 89 Thus Pepys, who was accustomed to taking clippings of medieval manuscripts owned by others as samples, proves to have been less tolerant of incompleteness in his own books. We may locate a Chaucerian example of the same phenomenon in a c. 1483 Caxton Canterbury Tales, now in Geneva, which lacks thirty-one leaves, and which already had several leaves damaged and torn in its pre-modern history.Footnote 90 An early owner repaired these leaves by patching holes and tears, furnishing partially torn leaves with new paper, and recopying missing passages on the freshly mended pages (see Figure 2.7). A watermark on one of the newly added leaves suggests a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century date for the repairs, while similarities between the supplied text and Richard Pynson’s c. 1492 edition single it out as the repairer’s most likely source text.Footnote 91 The material and textual mending of this copy by an early modern user illuminate certain bibliographic expectations about the early printed book which parallel those gleaned from the previously discussed manuscripts. In this case, the copyist supplied the missing text in an archaising script that approximates the black letter in which Chaucer was printed until the eighteenth century. Significantly, they also reproduced extraneous technical and visual details from the printed edition which were no longer strictly necessary in a manuscript copy: the indented spaces left blank for decorated initials at the beginning of tales and prologues, page signatures, and a catchword.Footnote 92 This programme of repair may have been necessitated by the desire to supply the missing text, but efforts were made to match the aesthetic of the original page and to ensure visual continuity with the rest of the book. Medieval manuscripts and the earliest printed copies of Chaucer therefore have certain aspects of their reception in common – notably their status as objects of value for later collectors like Pepys, who dealt in both.Footnote 93 But medieval manuscripts, as David McKitterick observes in his recent history of print and bibliographical rarity, also ‘have their own trajectories’, and it is these that the present work seeks to trace.Footnote 94

Figure 2.7 Early modern repairs imitating the printed page in a copy of Caxton’s second edition of the Canterbury Tales.

In identifying the pattern of print-to-manuscript transmission in the history of reading Chaucer, this study highlights a phenomenon which confounds expectations about the linear progression of objects through historical time and the value of newness in relation to the old. Manuscripts perfected in these ways show that readers appreciated their age and material properties even as they sought to improve their texts. The creation of supply leaves for damaged or unfinished Chaucerian manuscripts may thus be taken as a proxy for their value in the early modern period. It is a value that could be construed in economic, cultural, social, antiquarian, textual, or other terms – meanings which are seldom expressed but which are hinted at in their owners’ expenditure on parchment and scribal labour, in the careful collation of one text with another, in the use of a book to pledge friendship and loyalty, or in the efforts of imitation and decoration taken during repair. In turn, the omitted, torn, and lost leaves returned to manuscripts by their readers and owners affirm the utility of print in enabling the appraisal and renewal of older books.

2.3 Textual Lacunae: Reading the Gaps

Unlike the transcription and intercalation of leaves replacing lost text, the filling in of textual gaps is a type of preservation which happens on a smaller scale, typically on the level of the word or the line. Compared to the loss of whole leaves or quires, scribal lacunae might seem a relatively minor imperfection, but early modern readers often noticed and filled in these gaps. This attention to the minutiae of the page provides a valuable record of early modern resistance to incompleteness in the corpus of medieval Chaucer manuscripts. The lacunae exist because scribes sometimes interrupted the flow of their copying when they noticed something either missing or puzzlingly amiss in their exemplars.Footnote 95 As Wakelin explains, the resulting gaps may be interpreted as thoughtful scribal pauses, and suggest ‘a plausible aspiration to perfect the book in stages’.Footnote 96 This gradatim perfecting of books in scribal workshops is also discernible on the manuscript page at points when one hand suddenly intervenes to correct or supplement what another has copied. In the earliest manuscript of the Canterbury Tales, for instance, a scribe contemporary with the main copyist found two missing lines as well as two half-lines and, lacking a reliable exemplar, ‘was forced to rely on his own invention to fill these gaps’.Footnote 97 In print, too, textual gaps could invite completion. Peter Stallybrass, who has studied the proliferation of printed forms designed to be filled in by hand, has remarked that ‘the history of printing is crucially a history of the “blank”’. Early modern readers were accustomed to gaps, and to filling them in.Footnote 98 They operated in a do-it-yourself textual culture which invited people to take the book’s completeness, accuracy, appearance, and configuration into their own hands – for instance, to correct and amend printed texts by hand, to locate suitable maxims for recopying or material extraction, or to unite choice titles in a desired binding.Footnote 99

For some readers, the habit of supplying missing words or whole lines was a natural response to a type of incompleteness which was relatively commonplace.Footnote 100 The production of medieval manuscripts often included the processes of locating exemplars; preparing and ruling the leaves; copying, rubricating, correcting, and decorating the text; and binding the resulting book. But this process did not necessarily unroll in a sequential manner, and many manuscript books contain some evidence of things having been done out of order, of having been started and then aborted, or of having been planned but never begun at all. Such is the case in a Parkerian copy of Troilus and Criseyde, a fifteenth-century manuscript in which space was apportioned for a de luxe programme of over ninety images, but which lacks all but its frontispiece illustration.Footnote 101 In another copy of the Canterbury Tales, the mid-fifteenth-century scribe, who named himself ‘Cornhyll’, left an abundance of gaps – not only for unavailable bits of text such as the ending of the Squire’s Tale, but also for images.Footnote 102 Throughout the manuscript, lacunae ranging in length from seven lines to twenty-three (and probably intended for portrait miniatures of the pilgrims) have been left between the rubricated explicits and incipits, thereby punctuating the conclusion of one speaker’s tale and the start of another’s prologue. In one such case, a blank space which stretches across an opening from fol. 126v to 127r and which separates the end of the Clerk’s Tale from the beginning of the Franklin’s Prologue has been populated not with pictures of the pilgrims but with birth records for the children of Jane Otley and Edward Foxe, who owned the manuscript in the sixteenth century.Footnote 103 For the most part, though, these yawning gaps in Cornhyll’s manuscript remain vacant, and remind us that filling in either a book’s missing text or pictures, even when exemplars might have been at hand, was not an unthinking reflex but a deliberate act intended to finish a text left incomplete.

In the Fairfax manuscript, a mid-fifteenth-century miscellany containing short courtly works of Chaucer, Lydgate, and others, two quires were also left blank at the beginning as well as at the end of the manuscript to await further text.Footnote 104 The Fairfax scribe was a scrupulous copyist. Where words and lines were missing in his exemplar, he left blank spaces on the page and observed the absence with a note (‘hic caret versum’) in several places, perhaps signalling that he or a colleague should revisit and fill these gaps, although neither ever did.Footnote 105 The meticulous John Stow was one reader who noticed these gaps. In Fairfax, he seems to have paid closest attention to the texts of Lydgate’s Temple of Glass, Chaucer’s Book of the Duchess, and the anonymous Middle English poem Chance of the Dice, which Stow also believed to have been written by Chaucer.Footnote 106 In this manuscript, Stow not only supplied glosses and contextual and historical tidbits, but he also restored missing snippets of text.Footnote 107 In Temple of Glass and Book of the Duchess, Stow supplied one and two missing lines respectively, showing an instinct for textual completeness rooted in his philological and antiquarian preoccupations.Footnote 108 In the case of Chaucer’s dream poem – which was missing two lines, for each of which the Fairfax scribe left a one-line space – Stow’s source text appears to have been that of his predecessor, Thynne, or a later print based on it.Footnote 109 It has been recognised by Edwards that Chaucer’s early printers had to undertake a certain degree of ‘textual housekeeping’ in order to prepare their texts for the press, since ‘printed texts had to meet audience expectations that were different from those for manuscripts’.Footnote 110 Stow’s minute additions to Fairfax show him undertaking a different but recognisable type of textual housekeeping – not necessarily adapting manuscript texts for print, but using printed books as a means of textual repair.

Another early modern reader of Fairfax was confronted by a longer gap at the foot of fol. 130r, where the Book of the Duchess stops abruptly after its first thirty lines. The verso of the same leaf (fol. 130v) is also blank, and the copying resumes at the head of fol. 131r, but at a different point in the story. The lacuna created by this interruption is a visual as well as narrative disruption, appearing during a description of the dreamer’s lovesickness only to pick up in the midst of the tale of Seys and Alcyone. A seventeenth-century reader with a hand that seems later than Stow’s supplied the missing sixty-six lines (ll. 31–96), either from Thynne or from a later edition based on his text (see Figure 2.8).Footnote 111 The linguistic particularities of this transcription are worth noting. In copying Chaucer’s text from print to manuscript, this later anonymous reader took the opportunity to modernise certain words from Thynne – for instance, ‘her’ becomes ‘ther’ and ‘nyl neuer’ becomes ‘will neuer’. And after copying line 96, the last line on fol. 130v and the final line that had been missing, the annotator also added catchwords (‘Had such’), in imitation of the original scribe’s hand and in anticipation of the line to follow. Such welding is an attempt to establish visual unity between the pair of previously disjointed leaves and to restore the manuscript book to a state even better than its original. While the single lines filled in by Stow operate on a different scale from the sixty-six lines later supplied by the seventeenth-century hand, both annotators register a striking response not to the book’s matter but to its unfinishedness.Footnote 112 Each shows an instinct to improve the Book of the Duchess by completing the lacunae found in its text, and each turned to readily available printed books for what they believed were reliable copies of Chaucer’s dream vision.Footnote 113

Another significant textual gap in Fairfax appears at the end of the House of Fame. These lines have a complex history which is bound up with the seemingly unfinished nature of the House of Fame itself. The final line of Chaucer’s poem in the authoritative witnesses (including Fairfax) occurs at the precise point where the dreamer Geoffrey espies ‘A man of gret auctorite’ (l. 2158) whose appearance promises to restore order to the poem’s cacophony.Footnote 114 In other manuscripts, however, the copying appears to have stopped even before this – at the point where the embodiments of a lie and a truth jostle for passage (‘And neyther of hym myght out goo’, l. 2094). The copy on which Caxton based his 1483 edition contained this earlier ending but he was evidently displeased with the lack of narrative resolution, and so composed a tidy twelve-line ending for the poem himself, which sees the dreamer awakening and writing down his dream. Caxton conscientiously printed his own name beside the new verses and added a further prose note surmising that since he could not locate its ending, Chaucer had probably ‘fynysshyd’ the poem prematurely at the ‘conclusion of the metyng of lesyng and sothsawe’.Footnote 115 When it came time for Thynne to prepare the House of Fame for his 1532 edition, he relied on a text which, like Fairfax, ended with the ‘man of gret auctorite’. Thynne would have recognised the discrepancy between the ending in his copytext (l. 2158) and that of Caxton (l. 2094), but liked the earlier printer’s neat ‘conclusion’ for the poem enough to retain it. His solution was to rewrite the first two-and-a-half lines of Caxton’s continuation, removing mention of the jostling ‘lesyng and sothsawe’ in order to fuse them seamlessly with the last line in his own exemplar, l. 2158. From 1532, this became the form in which the end of the House of Fame was printed and read until the nineteenth century: with both Caxton’s continuation and Thynne’s rewritten lines, but without any indication of their spurious status, or of Caxton’s initial concern that Chaucer may have left the poem incomplete. All of this reveals an accretive process by which Chaucer’s poem was ‘fynysshyd’ by two early and influential editors who reconciled the manuscript evidence before them with a new ending which offered the satisfaction of a neat ‘conclusion’.

Encountering the printed conclusion alongside the substantial gap left for it in Fairfax, the same seventeenth-century reader (who filled in the gap in the Book of the Duchess) supplied the twelve lines:

The lines have been copied from Thynne or a later edition based on it.Footnote 117 But the annotator also diverges from Thynne’s text in the decision to supply an explicit – ‘Here endeth the booke of Fame’ – which appears almost redundant in its position following Caxton’s final couplet, ‘Thus in dreaming and in game / Ended this litel booke of Fame’. By filling this textual gap, the new annotator responded not only to the unsatisfying lack of an ending in Chaucer’s poem, but also to an invitation to supply the missing text cued by the blankness of the page left by the original scribe. This reader’s heavy-handed explicit heralds the appearance of this new ending and supplies a closure with whose absence the original scribe, Caxton, and Thynne had all previously grappled. Consistent across these successive layers of editorial and readerly finishing is a preference for completeness motivated by a concern with the text’s integrity and preservation. The confected endings in the scribal and editorial history of Chaucer’s works, John Burrow has observed, ‘betray a desire for immediate closure, as if the texts could not, without discomfort, be left gaping open’.Footnote 118 The latterly filled-in gaps, blanks, and lacunae in medieval manuscripts confirm the susceptibility of early modern readers to the same desire.

In a Glasgow copy of the Canterbury Tales, another seventeenth-century reader took to their manuscript of Chaucer with the same intention to perfect its incomplete text. Glasgow, MS Hunter 197 (U.1.1), which also contains St Patrick’s Treatise on Purgatory, was copied by the father-son pair of scriveners named Geoffrey and Thomas Spirleng, who were working in Norfolk in the late fifteenth century. The Spirlengs left the manuscript with forty gaps for words, phrases, and lines they could not or did not copy, and which often show them ‘choosing not to copy things they thought they could not correctly render’, such as illegible or unusual text in the exemplar.Footnote 119 A later reader, probably working in the late seventeenth century, noticed these gaps and decided to fill them. The furnishing of textual lacunae was part of a larger programme of perfecting undertaken by the same person, who dutifully reports at the head of fol. 1r that the manuscript has now been ‘Compared with ye printed Coppy’.

On the basis of textual variants which the annotator transcribed from the print, the comparison text is likely to have been Stow’s edition.Footnote 120 This reader was diligent, often recording the source of his interventions with a discreet abbreviation – ‘pr.’ – after the words themselves, to signify the printed origins of these additions.Footnote 121 Like Spirleng, this later copyist from print to manuscript was committed to supplying the best readings. Some of Spirleng’s largest gaps occur on fol. 65r, where parts of five individual lines in the Tale of Sir Thopas have been left incomplete (see Figure 2.9). The early modern copyist finished the first line by directly filling in the blank space – ‘His Jaumbes <were of cure buly>’ – following the printed exemplar. But the transcription of the other line endings is more tentative, and they have been written not in the obvious gaps that had been left for that purpose by the first scribe, but in the column’s right-hand margin. Such annotations witness the early modern reader’s response both to cues left by the book’s first copyist and to the text in a seemingly authoritative ‘printed Coppy’. The annotator guessed, correctly, that these were textual cruces which the original scribe had been unable to resolve, and which resulted in a series of gaps. Some of the supplied words in this passage would have been curious to an early modern ear and eye – such as ‘cure buly’ for quyrboilly or boiled leather; ‘wanger’ for wonger or pillow; ‘destrer’ for dextrer or war-horse – while others like yvorie and finde & good would have been familiar, so the annotator’s hesitation to fill the gaps in the latter two cases is curious.Footnote 122 Perhaps it is the earlier scribe’s silence on these points, marked by five ominous blank spaces in the text block, which likewise led the later reader to be cautious about the readings in the printed copy and to relegate the supplied line endings – ‘of yvorie’, ‘wanger’, ‘fedde his distrer’, and ‘herbes finde & good’ – to the margins.

The Glasgow copy of Chaucer is unusual for the number of gaps left in the text by the Spirlengs, but not for its evidence of later annotators who were eager to fill them. Another fifteenth-century manuscript, a copy of Troilus and Criseyde at the British Library, contains five instances of gap-filling by a later hand with sixteenth-century features. Some of these additions are written over erasures and in this case, too, the supplied text is likely to have originated in a print.Footnote 123 Similarly, it is possible that the careful annotator of Ld2, whose hand appears over rubbed-out words more than two dozen times in that copy of the Canterbury Tales, was populating gaps of someone else’s making.Footnote 124 For such book owners, the seemingly trivial act of completing the text by filling in blank spaces was part of a sustained intellectual engagement with the puzzles presented by the medieval manuscript, and another way that they could perfect scribal copies of Chaucer’s works which were visibly wanting. The afterlives of manuscript books up to two centuries after Caxton show that it was not only the early printers or editors like Stow who engaged in textual housekeeping of the sort described by Edwards. It emerges from the copies considered here that early modern readers – the consumers for whom Middle English texts were tidied up by the makers of printed books – were liable to do their own upkeep, repair, and perfecting of incomplete manuscripts. By keeping the old books functional and intact, those readers assured their continued use and longevity.

As with replacement leaves, the dislike of blank space or the opportunistic filling in of gaps is not in itself a consequence of print culture. Some campaigns of decoration in medieval manuscripts, for instance, were carried out decades after space was allocated for them initially.Footnote 125 What print offered to early modern readers of Chaucer was an accessible and seemingly authoritative model for repairing and completing older copies. For these readers, the interrupted narrative and the blank page were unwelcome absences in the Chaucerian manuscript book, and printed copies provided a template for finishing them. In the care and attention they show to filling gaps in Chaucer’s oeuvre, these forms of perfecting echo the interest previously observed in relation to his words. Like correcting, glossing, and emending, the repairing and completing of his manuscripts demonstrate Chaucer’s elevation as an object of philological study and a site of cultural value in the early modern period.

2.4 Mutilated Bodies and Books

The early modern instinct to supply lost leaves or missing words on the pages of a Chaucer manuscript reveals a predisposition for textual and bibliographical completeness conditioned and enabled by print. This chapter has cited the fact that the philological project of textual recovery employed a trope of corporeal destruction and reconstitution and has alluded to the moralised tenor of this discourse. Mutilation, it has been shown, was used as a master metaphor for damaged and fragmented books since the Italian Renaissance, and one which provides vital context for the early modern acts of repair with which this chapter is concerned. I wish now to revisit the concept through a more critical lens and to consider some of the latent anxieties signalled in this language of bookish perfection and mutilation.

The scholarly language of perfecting or ‘making good’ a faulty book is as fraught as the descriptors ‘perfect’ and ‘good’ suggest in their everyday usage. The suggestion that historical texts have moral properties has been entrenched in modern bibliography at least since A. W. Pollard’s proposal that some of Shakespeare’s early play texts were ‘bad quartos’ with no textual authority. As Random Cloud suggested over four decades ago in a denouncement of this idea and the editorial traditions behind it, ‘The real problem with good and bad quartos is not what the words denote, but why we use terminology that has such overt and prejudicial connotations’.Footnote 126 This implicit moral orientation of textual criticism is discernible across the entire constellation of the humanist intellectual endeavour. According to Tim Machan, the study of Middle English texts inherited the ‘moral overtones that characterised as degeneration the developments a text underwent through transmission’. Carolyn Dinshaw has likewise exposed the ‘pervasively moralised, gendered diction’ inherent to modern textual criticism.Footnote 127

For example, Sidney Lee’s 1902 census of surviving copies of the First Folio categorised entries according to his own hierarchy of perfection: Class 1 represented ‘Perfect Copies’, Class 11, ‘Imperfect’, and Class 111 ‘Defective’ ones.Footnote 128 For collectors in the nineteenth century, the best copies were those that were ‘tall’, or in ‘handsome’ bindings.Footnote 129 Emma Smith has pointed out that the use of such terms is problematic; due to the ‘anthropomorphic drift of the use of a term for assessing human not bibliographic proportions’, Lee’s classifications ‘slipped uneasily into a judgement on the owners themselves’.Footnote 130 The same range of descriptors was used in modern philological scholarship on medieval manuscript books. As Tom White has demonstrated, for late nineteenth-century medievalists, the concept of ‘defectiveness’ was available in that period ‘as a powerfully generic metaphor that conjoins editorial theory’s moralism and positivism with contemporary discussions around disability, class, and race’.Footnote 131 ‘Perfect’ books were complete; ‘imperfect’, ‘defective’, or ‘mutilated’ ones were not. These bookish words still have currency in scholarship today but their histories are not neutral, as scholarship in the field of disability studies has shown.Footnote 132 Rather, they enfold historical attitudes to human bodies of the past which, like the books to which they would be compared, were seen as unfinished, incomplete, or fragmented. An excavation of the past usage and historical register of these now ubiquitous terms is appropriate to the widening and self-critical purview of the history of the book.Footnote 133 A knowledge of their origins also deepens our understanding of the latent historical anxieties around textual loss encoded in these terms.

Printed and handwritten artefacts alike have long been described as though they were bodies, and consequently idealised in a language of perfection (and its lack) that is steeped in prejudiced views about their reliability and authority. For Aristotle, whose influence on the matter would persist until the Enlightenment, the human female body existed in a perpetual state of ‘mutilation’ or ‘deformation’, terms which he also applied to the physical conditions of castration, disability, and dismemberment.Footnote 134 In the Aristotelian tradition adopted by Galen, the less-than-perfect female body was viewed as an incomplete expression of the male form, and all bodies which deviated from the normative male standard were comparatively deficient.Footnote 135 Early modern medicine and theology inherited these ideas about imperfect bodies, and used the language of mutilation to characterise them. In the same period that the collected plays of Shakespeare were advertised (as was noted) as ‘cur’d, and perfect of their limbes … as he conceived them’, children born with physical disabilities could be described as ‘mutilate of some member’.Footnote 136 The pairing ‘imperfect and mutilate’, used to refer to people who were missing limbs, encapsulates the historical antithesis between the ideas of incompleteness and perfection.Footnote 137

This troubling resonance within the nomenclature adopted by scholars and historians of the book is important to confront in itself, and it is essential to an understanding of the intellectual scaffolding upon which modern conceptions of the book have been built. Such concerns are not as distant from Chaucer as they might initially appear. Although it does not explicitly invoke the rhetoric of mutilation and perfection, one of Chaucer’s tales exposes the imbrication of the concept of completeness in gendered, ableist, and even bookish ideals. The Wife of Bath, whose first named characteristic in the General Prologue is the fact that she is ‘somdel deef’, goes on in her Prologue to explain that her condition results from a single biblioclastic act:

She later clarifies that what she finally ‘rente out of’ her husband Jankyn’s misogynist book was more than a single ‘leef’: ‘Al sodeynly thre leves have I plyght / Out of his book, right as he radde’.Footnote 139 In her telling, the bodily violence she suffers is a direct requital of her own violation of the book’s textual integrity.Footnote 140 It is an equivalence embedded in the poetic form of her Prologue itself, where ‘leef’ is twice used as the rhyme word for ‘deef’.Footnote 141 Alisoun’s enduring punishment – to be ‘al deef’ for the rest of her life – points once again to the twinned historical anxiety about faulty books and imperfect bodies encoded in the very language used to describe and study those books.

The language of the book world is still replete with corporeal imagery: books have spines and joints, and pages possess a head and a foot. Those that show signs of damage are still labelled ‘defaced’, ‘dismembered’, ‘defective’, or ‘mutilated’ by modern scholars. Less apparent, and teeming beneath this language, is its mass of pejorative associations. This analogy made by early modern people between the imperfect book and the body matters because it helps to account for the sometimes radical efforts taken to restore, complete, preserve, and perfect old books that were wanting some part. In this context, for an early modern book to be imperfect meant not simply that it fell short of an abstract ideal, but that it was fundamentally, unsettlingly, and undesirably incomplete.Footnote 142 If books were not already in a complete state, however, then they could be made perfect by the scholars who styled themselves as the healers and restorers of a fragmented literary culture. The somewhat solipsistic position of the early modern scholars and collectors who felt compelled to preserve old and endangered books is also expressed in their chosen language – in Poggio’s use of the Latin integer to describe the ‘bodily integrity and moral blamelessness’ of the restored text,Footnote 143 and in Joseph Holland’s choice of procurare, a word related to modern English cure, from the Latin curare (meaning to take care of, to care for, or to heal or cure) to describe his relationship to a medieval manuscript book.Footnote 144

* * *

The history of the book is peppered with arresting stories of bibliophilia and destruction, and of volumes at turns cherished and plundered. Sometimes, these whirlwind trajectories can be tracked through the history and provenance of a single copy.Footnote 145 Following Chaucer’s books from their fifteenth-century origins and into the early modern period brings to light a comparatively neglected history of book repair and conservation avant la lettre. In an era better known for its destruction and disassembly of manuscripts, this surviving evidence of book repair is worthy of note. It has been suggested by Burrow that unfinished works written by ‘named vernacular masters’ such as Chaucer were more likely to be published posthumously during the Middle Ages.Footnote 146 Then, as now, even a fragmented text by a venerable Middle English auctor was invested with a high cultural value. But a complete text was superior to a fragmentary one and in the course of their scribal and later print publication, attempts were made to conclude or at least superficially wrap up Chaucer’s incomplete works in these new tellings: the Cook is assigned the Tale of Gamelyn, the dreamer in the House of Fame wakes up to write his poem, and the Squire’s Tale is capped off by a series of apologetic explicits. These efforts to paper over the textual cracks in Chaucer’s oeuvre speak to a pre-modern desire for closure. Burrow argues that this preference for completeness dissipated in the twentieth century, a period when ‘[w]hat we like is openness’.Footnote 147 Many readers in the late medieval and early modern periods, however, tried to recover, complete, and multiply what was in danger of being lost. In isolation, the filling in of physical tears in a book’s parchment, of lost leaves, and of lacunae in the written text by later readers may appear idiosyncratic; assessed cumulatively, they articulate an ideal of wholeness pursued by the people who made these repairs.