We will deal here with the embedded Wh- in situ clauses in French, an underestimated sociolinguistic and diatopic variable, yet not much studied by the generative approach (Shlonsky Reference Shlonsky2017). Embedded Wh- in situ clauses are usually considered as very strongly regionally marked (Shlonsky, p.c.), but they nevertheless belong to spoken French in surprisingly many areas throughout the realm of “Francophonie”, and can even be held straightforwardly as typical “français tout court” (Blanche-Benveniste Reference Blanche-Benveniste1983). There are plenty of occurrences as unmarked, ‘ordinary’ utterances in the French spoken in Quebec (Lefebvre & Maisonneuve Reference Lefebvre and Maisonneuve1982; Blondeau & Ledegen Reference Blondeau and Ledegen2021) or in Reunion Island (Ledegen Reference Ledegen2007a, Reference Ledegen2007b, Reference Ledegen2007c, Reference Ledegen2016; Ledegen & Martin Reference Ledegen and Martin2020). Indeed, this convergence may be seen as some kind of an archaism (according to Bartoli’s “lateral area/geolinguistic norm effect” (1945)), which would have remained in usage through the historical parallels between these two territories. A new type of corpus, ecologically conceived by the recording of people who know each other well (Koch & Oesterreicher Reference Koch and Oesterreicher2001; Guerin Reference Guerin2017), has provided evidence of a very high rate of usage of this structure in the suburbs of Paris (Gardner-Chloros & Secova Reference Gardner-Chloros and Secova2018) and of Strasbourg (Marchessou Reference Marchessou2018).

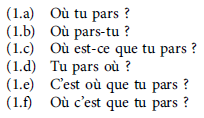

French Wh interrogation reveals different strategies. The direct structures use Wh in initial position, with (a) or without (b) inversion of the subject and the verb, initial Wh with est-ce que (c), the in situ option (d), the clefting option (e) and initial Wh with non-inverted est-ce que (f):

The embedded structures reveal initial Wh (g), with est-ce que (h) or c’est que (i), and the in situ option (j); this paper is concerned with this last optionFootnote 1 :

The new data concerning the embedded Wh- in situ clauses call for different analytical hypotheses: recent linguistic change, language contact, learner’s variant, long-established structure of ‘registre populaire’ (Guiraud Reference Guiraud1966). The focus here will be on the embedded Wh- in situ clause, with elements of comparison with the embedded qu’est-ce que interrogative clause. After examining previous studies in different French-speaking areas, and different media elements that give the impression of an increased use in France, we conduct further explorations on the embedded Wh- in situ clauses through the Fonds de données linguistiques du Québec (FDLQ): the contrast between the different corpora gathered in the FDLQ will allow us to analyse the current patterns of the embedded Wh- in situ clauses, according to modes of interaction, following the oral or written medium, as well as on the chronological axis (diachrony – synchrony). These latter explorations will highlight the status of the embedded Wh- in situ clauses in Quebec French, and reveal its presence through time.

The embedded Wh- in situ clauses being found in other French-speaking countries, with close sociolinguistic representations (colloquial French), the emergence of the structure will be analysed, while it feeds into our pan-French perspective (Chaudenson, Mougeon & Beniak Reference Chaudenson, Mougeon and Béniak1993; Boutin & Gadet Reference Boutin and Gadet2012: 19), which takes non-standard as its primary reference (Ploog Reference Ploog2002, Reference Ploog2019; Poplack & Dion Reference Poplack and Dion2009). Our analytical hypothesis is that the embedded Wh- in situ clause belongs to “français tout court” (Blanche-Benveniste Reference Blanche-Benveniste1983: 27), being part of the uses of language that form coherent systems of forms in the description. And by exploring the usages more fully, we could give a renewed place to this structure, as attested for the embedded interrogative with est-ce que (cf. infra).

Thus, this study uses different approaches, by studying multiple corpora (including normative opinions) and discussing syntactic theory, and enters by multiple angles: diachrony-synchrony, morpho-syntaxis and sociolinguistics. Our conviction is indeed that this combination can encompass the complexity of this non-standard structure.

1. IS THE IN SITU STRUCTURE GAINING GROUND, ALSO IN THE EMBEDDED CONTEXT, IF EVER…

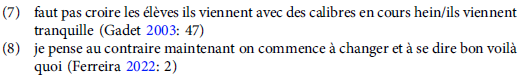

Several studies posit that the in situ form is nowadays gaining ground in the direct interrogative construction: this claim can be found, for example, in Dekhissi & Coveney (Reference Dekhissi and Coveney2018: 136 and 147), who draw on their own diachronic research on movies dealing with banlieue surroundings; Rossi-Gensane, Acosta Cordoba, Ursi & Lambert (Reference Rossi-Gensane, Acosta Cordoba, Ursi and Lambert2021) find increase of direct interrogatives in situ with où in dialogues of French novels during the twentieth century.Footnote 2 The present study will question the recent evolution of the embedded in situ structure, which may appear to be gaining ground too.

Another so-called non-standard structure has undergone a recent evolution towards greater acceptability: the embedded (qu’)est-ce que clause is analysed by Muller as colloquial:

Also for the colloquial usage, Riegel, Pellat & Rioul see it as an “[alignment of] the embedded structure on the model of the independent direct interrogative” (2021: 839). The same is true for Defrancq, who attests that “the ‘particle’ [est-ce que] is well installed at the very heart of the embedding“Footnote 3 (2000: 135). Finally, Blanche-Benveniste goes even further and classifies this embedded interrogative with est-ce que among:

les fautes qui n’en sont plus. […] [Cette tournure] est une faute qui agace beaucoup certains puristes. […] On la trouve [pourtant] partout, y compris chez les notables, les écrivains, les professeurs. (Blanche-Benveniste Reference Blanche-Benveniste1997a: 41)

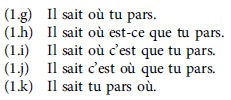

It is also interesting to note that “until the eighteenth century, est-ce que et c’est que in embedded interrogation belonged to good usage” (Grevisse Reference Grevisse1988: 683):

As for the embedded Wh- in situ clause, which does not have the word Wh- at the top,Footnote 5 it is considered at best as a “structure without a subordinating element” (Defrancq Reference Defrancq2000: 132), or even as “[not concerning] embedded interrogation as it is conceived [in his study (cf. note 3)]” (Defrancq Reference Defrancq2000: 137). Thus, Defrancq did not take into account the 16.9% of embedded interrogatives (12/71) which present the interrogative element in situ in Lefebvre and Maisonneuve’s study in Montréal (1982), arguing that “the classical conception of embedded interrogation as an embedded structure [is not to be questioned by these examples]” (Defrancq Reference Defrancq2000: 137).

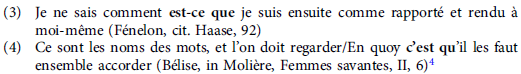

In fact, we should probably not question the conception of the indirect interrogative as an embedded structure,Footnote 6 but rather the conception of embedding as such, that should be made more flexible to match this kind of data. Indeed, there are other embedded structures that do not have a connector, such as the dropping of conjunction que attested in “ordinary” French in Reunion Island (Ledegen Reference Ledegen2007a, Reference Ledegen2007b):

as well as in spoken corpora in France:

or in Canada, where Martineau finds an omission rate of 28% in the Spoken French of Ottawa-Hull:

This absence of a connector doesn’t mean absence of embedding or of syntactic binding and dependency: Deulofeu indeed uses the term unasyndetic hypotaxis Footnote 8 beside syndetic hypotaxis (1989: 112).

2. INCREASED FREQUENCY OF ATTESTATION OF EMBEDDED WH- IN SITU CLAUSES

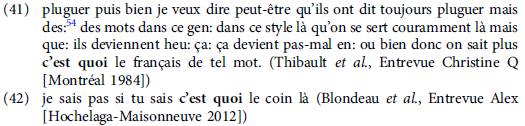

As it is the case for the direct interrogative, studies on more “ordinary” corpora are increasing, and the embedded in situ structure is mentioned more frequently: Lefebvre and Maisonneuve (Reference Lefebvre and Maisonneuve1982) was the first study to mention it, from a corpus of French spoken in the Centre-Sud district of Montreal. This study showed examples of embedded interrogations whose interrogative term happened to occur in situ (for example: Il y en a qui savent pas c’est quoi) (1982: 190), which constituted 16.90% (12/71) of all embedded interrogations in this data. Defrancq considered this percentage to be “spectacular when one considered that Coveney’s (1995) study of direct questioning attested only 13% of interrogative terms in situ” (2000: 136). In Quillard’s PhD thesis (2000), based on more “natural” and diverse corpora, the structure has been found to occur more frequently: the proportion of in situ structures in these direct interrogative constructions in “ordinary” spoken French made 15.57%.

In the French field of research, no occurrence appears e.g. in Defrancq’s study (Reference Defrancq2000), which is based on the CORPAIX corpus of the Groupe Aixois de Recherche en Syntaxe (GARS 1999), mainly based on interviews and life narratives, where few questions occur, especially by the interviewees. The very first mention appears in the study of the linguistic practices of young people in the Paris suburbs by Conein and Gadet (Reference Conein and Gadet1998). Footnote 9 These authors mention a single example of embedded Wh- in situ clause (“il regardait pas c’était qui”), and point out that “the absence of distinction between direct and indirect interrogation [has been recorded] for a long time” (1998: 110), and belongs to the “traits héréditaires populaires” (1998: 121). The structure is somehow attested in the research of Lefeuvre and Rossi-Gensane (Reference Lefeuvre and Rossi-Gensane2017) who find six forms: one in the Corpus de français parlé parisien (CFPP2000Footnote 10 ) (out of 144 embedded interrogatives) and five (out of 98) in the ESLO corpusFootnote 11 (Les repas, dating from 2012).

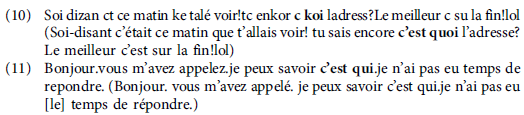

In Reunion Island, the structure is found to belong to everyday French (Ledegen Reference Ledegen2007a, Reference Ledegen2007b, Reference Ledegen2007c, Reference Ledegen2016; Ledegen & Martin Reference Ledegen and Martin2020), even more so than the embedded est-ce que. A careful analysis of six hours of recordings in the VALIRUN corpus that contain non-standard embedded interrogatives yields no less than 62 embedded interrogative forms, including 28 standard forms, 27 in situ and 7 with est-ce que (Ledegen Reference Ledegen2007a). It should be noted that the embedded Wh in situ structure is also attested in the written SMS-Reunion corpusFootnote 12 compiled in the framework of the SMS4science project, in familiar (ex. 10) but also more formal contexts (ex. 11):

Research carried out as part of the Phonology of Contemporary French project (Durand, Laks & Lyche Reference Durand, Laks and Lyche2009) also reveals multiple examples for Reunion Island and New Caledonia, where usage is quite widespread, and with highly variableFootnote 13 embedded verbs:

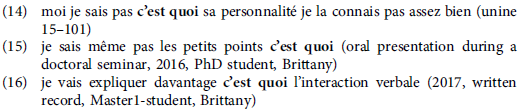

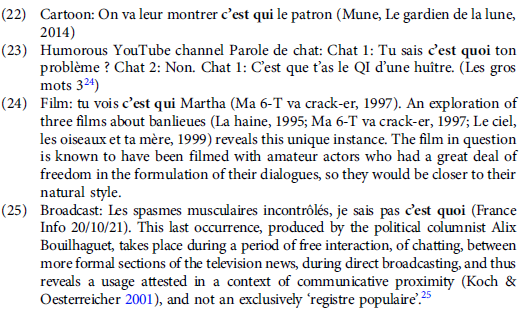

Moreover, this same database contains numerous examples from Canada (Blondeau & Ledegen Reference Blondeau and Ledegen2021), as will be discussed later in this study (cf. 4. Exploring the Fonds de Données Linguistiques du Québec). Other explorations show examples (4 in situ and 18 qu’est-ce que) of these structures in Switzerland (Ledegen & Martin Reference Ledegen and Martin2020) in the OFROM corpus (Corpus oral de français de Suisse Romande), and in Brittany (France):

In contrast, in 2018, the Multicultural Paris French study will reveal a very remarkable attestation rate in the Paris and Strasbourg suburbs: the Gardner-Chloros and Secova study (2018) on the Paris suburbs attests 61 embedded in situ interrogations out of 159 structures, i.e. 38% of the structures. And Marchessou’s study (2018) on the Strasbourg suburbs, a study made in the same MPF-project, shows 35 on 63 forms, i.e. 55%.

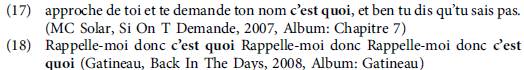

In a field similar to that of the suburbs, we analysed in 2020 the Rapcor corpusFootnote 14 (2009–…), made up of French and Quebec rap songs, by searching the repeated segments c’est qui and c’est quoi, the most frequent forms of the embedded in situ structures: this exploration yielded 18Footnote 15 embedded in situ structures (8 from the French corpus; 10 from the Quebec corpus). It is notable that only two statements could have been constructed for rhyming purposes:

These two statements also stand out from the rest of the corpus by not having the right dislocation, which is systematically present in the 16 other extracts:

The corpus of rap songs thus confirms the presence of the embedded Wh- in situ clause among these authors who are often considered innovative and counter-normative (Lesacher Reference Lesacher2015).

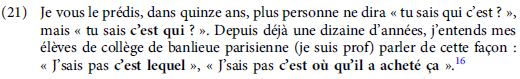

Moreover, the consultation of – non-scientific – language forums informs us that such a structure might have increased: for example, the forums mention the structure as early as March 2011:

After a long silence, the subject comes back, on two sites in 2020: on the Blabla 18–25 Forum on the one hand, and on the Question orthographe forum on the other. The latter is entitled, in a very normative way, “Tu sais c’est qui … tu vois c’est quoi … et autres immondices (règles ?))”Footnote 17 .

One can see that the explanation given by the Question orthographe website (cf. Table 1) shows a very strict standard for the direct interrogative, where the interrogative word should always be in the initial position (‘le pronom interrogatif […] se place devant elles comme d’ailleurs dans l’interrogative directe’).

Table 1. A mention of embedded Wh- in situ clause on the Question orthographe-forum

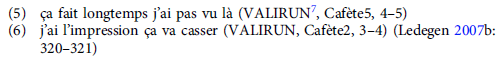

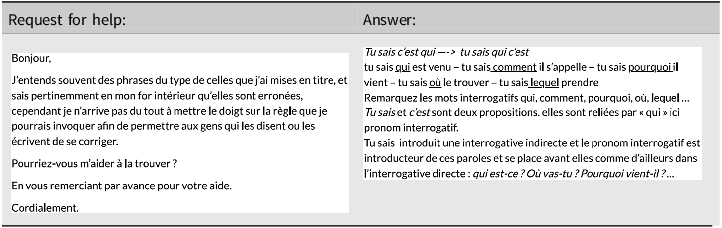

The structure is also mentioned in several Top 10 French mistakes: in 2016 in the fourth place (Les fautes de français qui nous horripilent Footnote 18 ), but in 2021 and 2022 in the first place (with the titles: Top 15 des fautes de français qui arrachent l’oreille Footnote 19 , and 13 fautes de français que tout le monde fait (et qui arrachent les oreilles) cf. Figure 1 Footnote 20 ):

1. “Je sais pas c’est qui”:

Petite sœur du fameux “je sais pas c’est où” et de “c’est qui qui dit ça”. On commence par du lourd avec une double faute.

On passe sur l’oubli de négation (“je NE sais pas”) car on est à l’oral.Footnote 21

Par contre, la construction par inversion du sujet (qui) et du verbe (est) n’a ici aucune raison d’être.

La bonne version: “Je ne sais pas qui c’est”Footnote 22

Figure 1. Illustration of the site ’13 fautes de français que tout le monde fait (et qui arrachent les oreilles)’.

It is interesting to observe the confusion in this comment about inversion. Footnote 23

Finally, the structure is attested also in very different media formats:

3. CONTRASTING HYPOTHESES

These different studies allow us to identify three major explanatory hypotheses that are attached to the rise of the embedded Wh- in situ structure:

-

(a) the structure would come from a situation of language contact (Gardner-Chloros & Secova Reference Gardner-Chloros and Secova2018),

-

(b) it would be a recent linguistic change (for example, given its total absence in the GARS corpora (Defrancq Reference Defrancq2005))

-

(c) the structure would be a turn of phrase of ‘registre populaire’ (in the sense of Guiraud Reference Guiraud1966) attested for a long time and characterised by the self-regulating tendencies of French.

The first hypothesis is combined with the second in the research by Gardner-Chloros and Secova (Reference Gardner-Chloros and Secova2018)Footnote 26 : the authors see the structure as ‘an instance of change from below (Labov, 2007), which seems to have emerged in the speech of young people of immigrant background’ (2018: 182). The language contact would have been generated by ‘bilingual speakersFootnote 27 who belong to major communities of immigrant origin’ (2018: 182), although no specific contact languages that would have spread the in situ structure can be identified (neither in the French suburbs or in Reunion Island) : neither English, Arabic, Berber, Reunionese CreoleFootnote 28 or German (for the suburbs of Strasbourg studied by Marchessou Reference Marchessou2018) present this structure.

Comparison with other vernacular corpora permits us to eliminate this contact hypothesis, which is frequently invoked in situations of language contact, even though the features belong to ordinary French, frequently attested for a long time. Poplack and St-Amand set out this frequent analysis for Canada:

L’étude du changement linguistique s’est butée depuis toujours à la rareté de données appropriées reflétant un stade antérieur de la langue. En effet, […] les textes écrits ont l’inconvénient de ne pas toujours refléter la langue parlée, lieu privilégié des changements. Le manque de données historiques fiables explique, du moins en partie, la notion courante voulant que de nombreux traits saillants des parlers vernaculaires contemporains soient des innovations récentes. Cette idée est particulièrement répandue dans le cas des variétés canadiennes du français, qui comportent plusieurs traits distinctifs, souvent même stigmatisés. On attribue d’ordinaire ces traits au changement, censément causé par le contact massif que ces variétés ont subi avec l’anglais depuis la Conquête britannique du Canada (1760) [ex. Laurier Reference Laurier1989], et par des siècles d’éloignement par rapport au français métropolitain et son influence se voulant normalisatrice. (2009: 511)Footnote 29

The same is true for Reunion Island, where the vast majority of ordinary French features are considered – especially by teachers – as an interference with Creole (Ledegen, Reference Ledegen2007b: 321); this explanation is not, however, the most plausible, as the in situ structure is the least used in the Creole embedded structures. Gadet and Jones attest this same phenomenon when it comes to non-standard or geographically distant structures:

grammarians of French may sometimes be overly quick to explain away as interference ‘unusual’ phenomena in non-standard and/or geographically peripheral varieties [to France]). (2008: 246)

Rather than considering this structure as ‘un changement intralinguistique lié aux contraintes universelles de la parole spontanée (rapidité, manque de temps de planification entraînant une simplification syntaxique et des énoncés paratactiques)’ (Secova Reference Secova2017: 13), we link these different characteristics rather to the fact that it is a survival of a vernacular, colloquial, form ‘de registre populaire’ (Ledegen Reference Ledegen2016), which is in line with the evolutionary trends of French (Guiraud Reference Guiraud1966: 46; Lefeuvre & Rossi-Gensane Reference Lefeuvre and Rossi-Gensane2017). The term populaire is used here in the ordinary sense of ‘un usage non standard stigmatisé’ (Gadet Reference Gadet1992: 27), with all the criticismsFootnote 30 that the term deserves. It is a social practice of epilinguistic judgement which is common in society on the part of speakers from the metropolis. But to this sense we add another, that is the one used by P. Guiraud in his analysis of the term populaire: in the “système de la relative en français populaire” (although it is not the prerogative of working-class speakers of course (Gadet Reference Gadet1989: 156)), where the term populaire refers to ‘le français héréditaire tel qu’on le parlait et l’écrivait au seuil de la période classique [qui] était en train de se décanter et de s’organiser selon les trois grandes tendances qui modèrent l’évolution du français: réduction des déclinaisons, décumul des formes synthétiques, syntaxe séquentielle’ (Guiraud Reference Guiraud1966: 46). So it is this link with ‘ordinary’ historical French, which is a common element in the fields examined here, that we wish to put in light.

4. EXPLORING THE FONDS DE DONNÉES LINGUISTIQUES DU QUÉBEC

We proceed here to a complementary analysis of the previous data through the Fonds de Données Linguistiques du Québec (FDLQ), recently put online by Centre de recherche interuniversitaire sur le français en usage au Québec (CRIFUQ) - University of Sherbrooke (2022). This exploration will allow us to highlight the structural regularities of the embedded Wh- in situ clause, but also contrast the different corpora gathered, according to the modes of interaction, following the oral or written medium, as well as on the chronological axis.

We have proceeded to a detailed examination of the 1498 c’est quoi and 3186 qu’est-ce que/qu’ in the corpora, which gives us 183 occurrences of embedded Wh- in situ clause and 104 of embedded qu’est-ce que clause. The study is focused on c’est quoi which is the most frequent structure in the analyses concerning the embedded Wh- in situ clauses; it is here compared with the embedded qu’est-ce que clauses. The FDLQ-collection providing no POS-annotation,Footnote 31 we couldn’t sort the 86.072 occurrences of the standard structure in ce que/qu’ in the corpus, in order to propose a complete and statistical analysis (our consultation of the site was in August 2022).

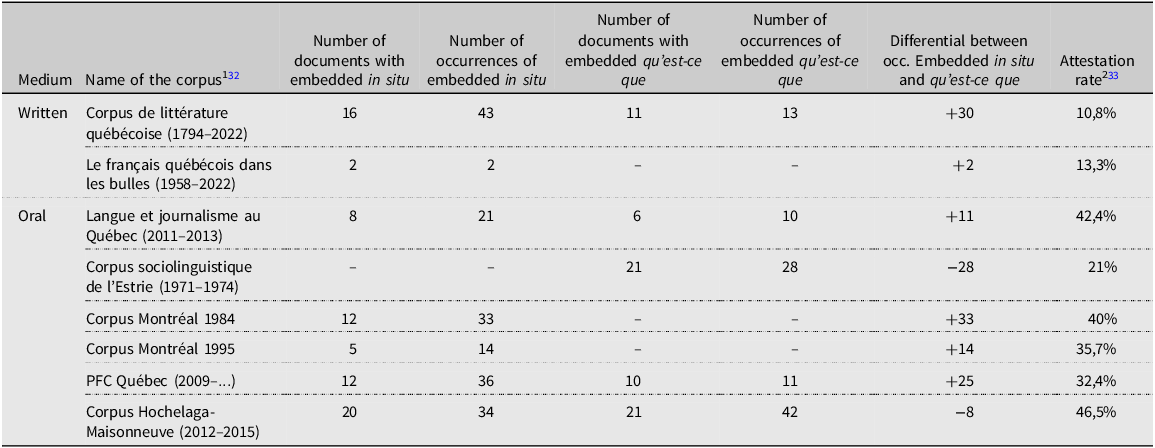

The Table 2 shows the six corpora concerned, described by general information (number of documents and single words), according to whether they are in the oral or written medium, and the number of occurrences of in situ and of the documents containing them. Finally, a value for the number of occurrences of in situ in relation to the number of words in the corpus shows the extent of attestation of the structure.

Table 2. Embedded Wh- in situ and qu’est-ce que clauses in the FDLQ by corpus and medium

The last column, revealing the attestation rate, shows very clearly that the in situ and qu’est-ce que structures are attested above all in the oral interviews: these are sociolinguistically oriented or focused on the journalistic environment (Language and Journalism in Quebec). The comparison of the two Montreal corpora (1984 and 1995) seems to show a decrease in attestation (respectively 33 et 14 occ.), but this impression is contradicted by the more recent PFC corpus (36 occ.) and the Hochelaga-Maisonneuve corpus (34 occ.), where the structures occur more frequently. It must be noted that in all these sociolinguistic corpora interviewers and interviewees produce both embedded structures, and for the PFC-corpus, they occur equally in the free as in the guided discussions (Ledegen 2021).

Another remarkable result is that the first oral corpus – Corpus sociolinguistique de l’Estrie (1971–1974) – doesn’t reveal any embedded Wh- in situ clause, but only qu’est-ce que structures; this corpus is joined by the most recent one – Hochelaga-Maisonneuve (2012–2015) – which presents more occurrences of the qu’est-ce que structure than the in situ one, as shown by the negative differential value (respectively -28 and -8). Is this a specificity of the localisations of these corpora (Estrie for example being a region at the intersection of the dialectal areas of Eastern and Western Quebec) or of their semi-guided methodology (the Hochelaga-Maisonneuve-corpus “were intended to mimic the flow of natural conversation and were loosely based on a script” (Blondeau, Tremblay, Bertrand & Michel Reference Blondeau and Ledegen2021: 7))?

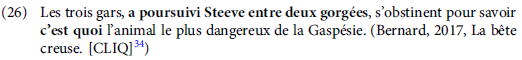

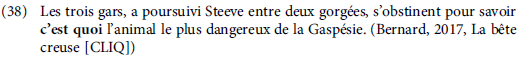

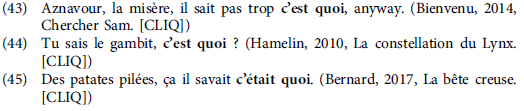

The occurrences in the literary and paraliterary corpora are also interesting: we find 42 embedded in situ in respectively 14 and two documents. The Corpus de littérature québécoise (CLIQ) includes several occurrences in quoted speech:

but also in narratives:

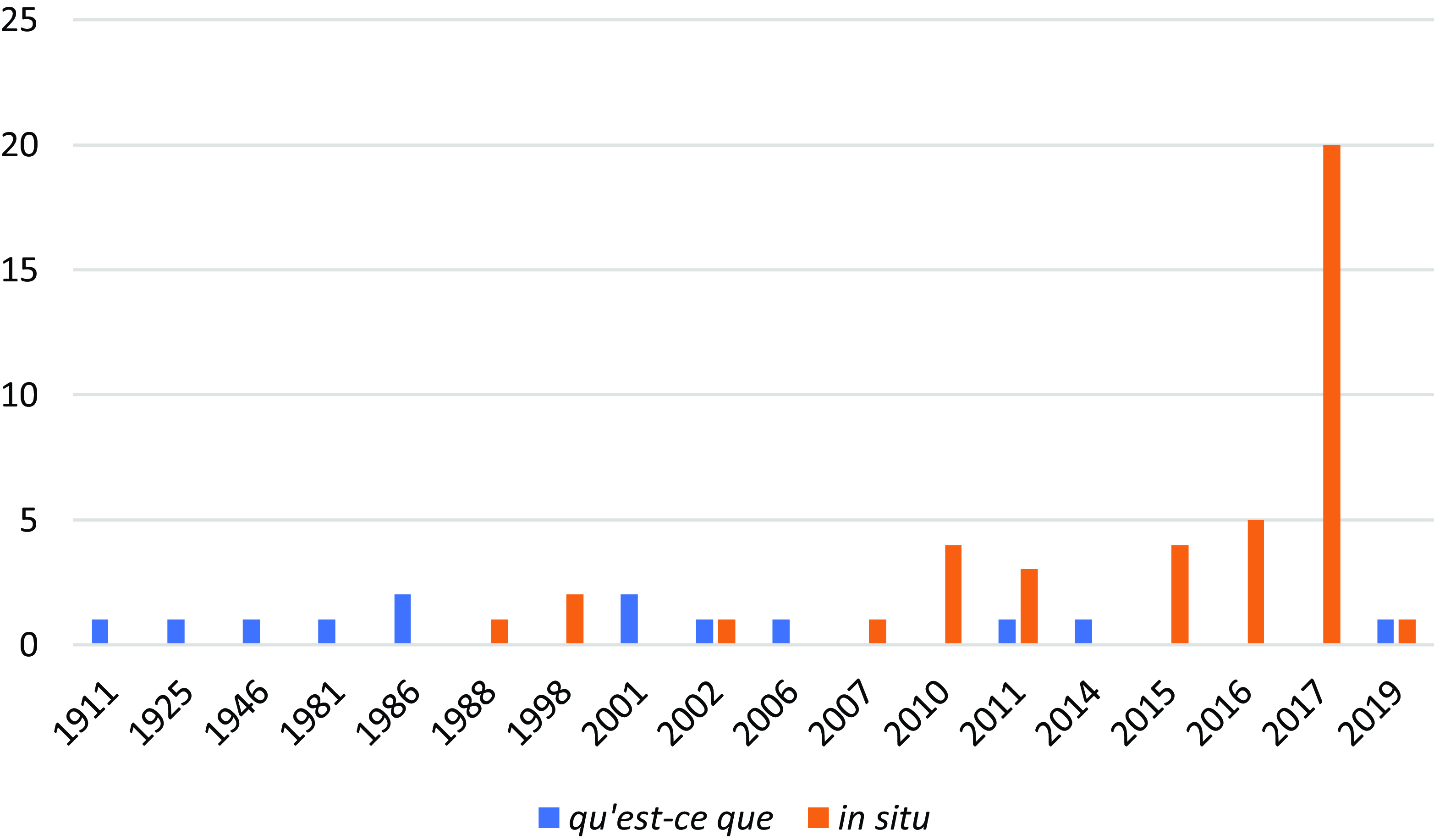

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of the number of occurrences of embedded in situ and qu’est-ce que clauses, and reveals that the attestations of qu’est-ce que are present since 2011, but appear to be taken over by the in situ structure from the 2010sFootnote 35 onwards:

Figure 2. Number of occurrences of embedded in situ and qu’est-ce que clauses in the CLIQ corpus of the FDLQ, per year.

We will see later that this literary corpus contains some formal particularities, which strongly differentiate it from the oral corpus and which reproduce, for some of them, stereotypes of the oral language, revealing a literary writing imitating the oral (Ledegen Reference Ledegen2019). Thus, these literary corpora, extending from 1794 until 2022, attest the ‘informalisation’ (Fairclough Reference Fairclough1996), and the ‘arrival of the oral’ in written practices previously closer to the prescriptive norm (Gadet Reference Gadet1999: 581; Meizoz Reference Meizoz2001 Footnote 36 ):

The engineering of informality, friendship, and even intimacy entails a crossing of borders between the public and the private, the commercial and the domestic, which is partly constituted by a simulation of the discursive practices of everyday life, conversational discourse (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough1996: 7). (emphasis added)

These attestations of both structures in the Quebec literary corpus, also and above all, reveal that they are widespread in society.

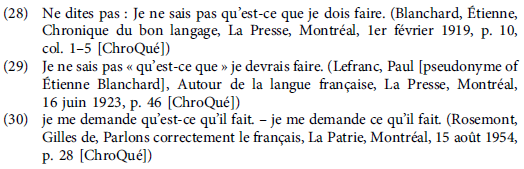

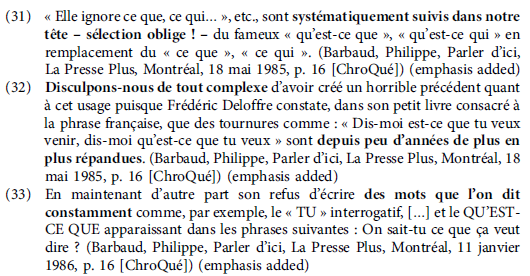

A complementary corpus of the FDLQ-fund sheds an interesting light on the two structures: the Chroniques québécoises du langage gathers language columns published in the Quebec press from 1865 to 1996. TwelveFootnote 37 of them mention the embedded qu’est-ce que clause between 1911 and 1986: in the first mentions, we find eight (five by the same author) which are corrective:

The more recent occurrences (all from the same author, a linguist) appear to be much more descriptive and even advocating for the structure (cf. ex. 26 & 27):

As for the embedded in situ clauses, they are not mentioned in these language chronicles at all. Moreover, neither of the two structures are mentioned on a website tracking in Quebec ‘la faute de français qui vous dérange le plus’Footnote 38 : it even shows an occurrence of the in situ structure in a critical comment about the word jour showing that the structure isn’t seen as ‘not correct’:

A normative publication figuring on the OQLFFootnote 39 -website about the sustained spoken French of future teachers mentions the embedded qu’est-ce que clause: ‘j’sais qu’est-ce que tu veux’ (Ostiguy, Champagne, Gervais & Lebrun Reference Ostiguy, Champagne, Gervais and Lebrun2005: 29, note 13) and the embedded in situ clause as colloquial variants, ‘caractérisée[s] par l’intrusion d’une interrogation directe en guise de complétive indirecte’:

These different publications reveal clearly the existence of both embedded structures and the evolution of the attitudes towards them.

As a whole, the embedded in situ and qu’est-ce que structures are clearly present in Quebec, as shown by the oral corpora, the literary sources, and more prescriptive writings. Several indications point out that the structures belong to the ‘ordinary’ everyday language.

The presence of the embedded in situ structures in particular among the speakers in Quebec and in Reunion Island, might Footnote 41 thus lead to a probable common source in the seventeenth centuryFootnote 42 :

Comparative reconstruction has equally yet to be fully exploited. The goal is to examine the French spoken overseas or creoles formed on the basis of spoken French taken abroad by colonizers in the seventeenth century. If common features can be identified in these varieties, especially if they occur in areas which are geographically disparate, it may be possible to hypothesize that these features are present in the common source, namely seventeenth-century spoken French (cf. Chaudenson Reference Chaudenson1973, Reference Chaudenson1994; Valdman Reference Valdman1979). The seventeenth century is a particularly fertile area for such investigation since French was taken to three principal areas which are geographically widely separated: North America, notably Acadia and Quebec; Central America, and especially Caribbean islands such as Guadeloupe, Martinique, Dominica, and Saint Lucia, and the Indian Ocean islands of Reunion and Madagascar. (Ayres-Bennett Reference Ayres-Bennett2004: 32)

What seems sure, is that the in situ structure doesn’t constitute a recent innovation of modern spoken French, but rather a case of ‘’long-standing differences in written and spoken usage’’ (Ayres-Bennett Reference Ayres-Bennett2004: 38).

We will now examine the embedded status of the structure we are analysing in this research, and then describe its characteristics in view of the FDLQ corpus, which allows us to contrast different situations of use of the structure.

5. STRUCTURAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE EMBEDDED IN SITU CLAUSE

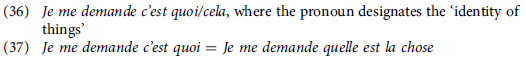

The embedded in situ clause, e.g. je me demande c’est quoi, combines the two characteristics given by Muller (Reference Muller1996) of indirect interrogative: equivalence with ‘cela’Footnote 43 ; paraphrasable by ‘quel est’)Footnote 44 :

Moreover, the subordination is “étanche” (‘impermeable’, i.e. true subordination), according to Blanche-Benveniste’s criteriaFootnote 45 (1982: 77–81). A final syntactic criterion concerns the “equivalence” between the different variants: as in the direct interrogative, where the variants qu’est-ce?, qu’est-ce que c’est? and c’est quoi? coexist, to mention only the main structures examined here, the indirect interrogative presents the variantsFootnote 46 il ne sait pas ce que c’est, il ne sait pas qu’est-ce que c’est, and il ne sait pas c’est quoi.

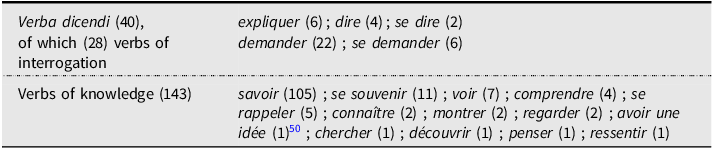

We can also note that the introduction verbs turn out to be classical introducers of subordination (Riegel, Pellat & Rioul Reference Riegel, Pellat and Rioul2018; Muller Reference Muller1996), “dont la valeur interrogative ne saute pas aux yeux” (Grevisse Reference Grevisse1988: 683, §411c, Remarques)Footnote 47 : they are naturally verbs of interrogation (28 occurrences) (demander, Footnote 48 se demander), a subcategory of verba dicendi (of whom 12 other occurrences are attested) (expliquer, dire…), and in great majority verbs of knowledge (143 occurrences) (savoir, montrer, comprendre, se souvenir, connaître, voir, regarder, ressentir, se rappeler, découvrir, penser, avoir une idée…); in sum, verbs that can signify “knowledge about the truth value of their complement” (Muller Reference Muller1996: 201–203). Table 3 lists the different verbs and one compound verbal according to these two categoriesFootnote 49 .

Table 3. Introduction verbs of the embedded in situ clause with quoi in FDLQ

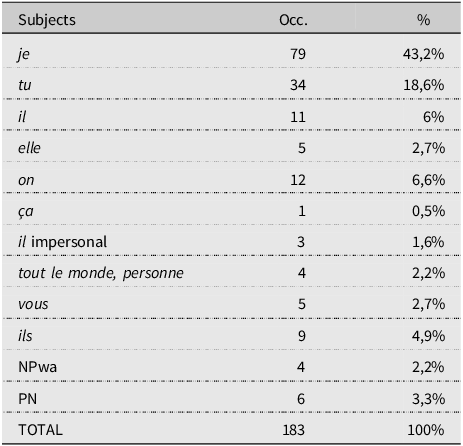

As for the subjects used by these introduction verbs, they are almost exclusively pronominal (93.8%), and concern essentially – and classically in interlocution (Halliday Reference Halliday1985) – the two persons of the interlocution je and tu, as Table 4 clearly shows:

Table 4. Subjects of the introduction verbs of the embedded in situ clause with quoi in FDLQ

Consistent with these major trends in oral language where mainly pronominal subjects appear, we note that subjects in the form of nominal phrase (NP) or proper nouns (PN) (6.2%) are quasi exclusively found in the literary corpus (6 occ.)Footnote 51 and in the metalinguistic interviews with the journalist (1 occ.):

These nominal subjects reveal a certain formality of discourse; the same is true for subject proper nouns, which in ordinary speech would be completed with a pronoun (40):

Thus, the literary corpus shows here informalisation, by stereotyping certain features of speech, without entirely corresponding to the orally attested uses.

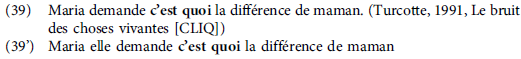

Then, as regards the form and modality of the introduction verbs, it should be noted that interrogation (by modality (for ex.: As-tu pensé c’est quoi ? (Vincent et al., Entrevue Paul G [Montréal 1995])) or verb type (for ex.: demander)) and negation together form three quarters of the examples, as show in Table 5 Footnote 52 .

Table 5. Modalities of the introduction verbs of the embedded in situ clause with quoi in FDLQ

Thus, the interpretation in terms of the truth value of the subordinate is above all indeterminate (Muller Reference Muller1996: 202), as noted in note 37 (‘il s’agit de quelque chose qu’on ignore et dont on s’enquiert ; la nuance interrogative est donc perceptible’ (Grevisse Reference Grevisse1988: 1693, §1102)): the truth value remains suspended as well because the speaker does not know which of the terms is the right one [negation], or because he knows and refuses to say [interrogation] (Muller Reference Muller1996: 208). But the affirmative form is still largely attested, revealing that the truth value can be fully assumed by the speaker:

Finally, as Table 6 shows, as far as the verb present in the embedding is concerned, the structure is very strongly fixed and used for the process of identification.

Table 6. Verbs in the embedded in situ clause with quoi in FDLQ

Almost all verbs turn out to be copulas, serving to identify: we find the form c’est mainly in the present indicative (136 occ.), and more rarely in the imperfect tense (43 occ.) or in the future tense, more specifically the periphrastic future (1 occ.). It should be noted that among the 43 forms in the imperfect tense, 22 (i.e. more than the half) come from the CLIQ literary corpus, which confirms that the embedded verbs show rather little formal variation. These results also confirm Secova’s findings, concerning the length of the embedded clause: « la forme in situ […] est favorisée dans des subordonnées courtes, comme c’est quoi, c’est qui ou c’est où » (Secova Reference Secova2017: 13).

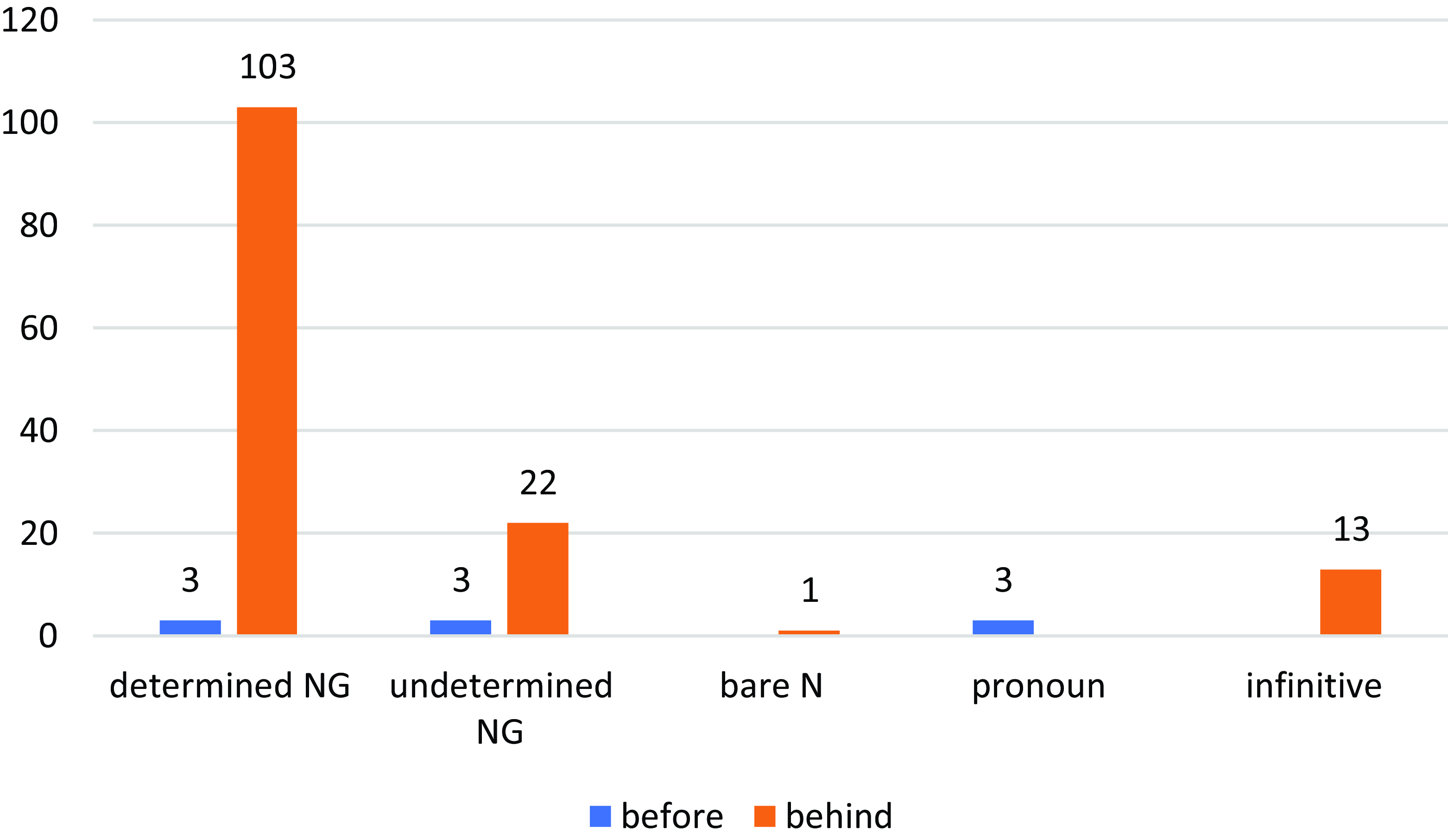

A final point worth examining concerns the detachment of a nominal or verbal phrase, also known as left (before) or right (after) dislocation: Blanche-Benveniste (Reference Blanche-Benveniste1997b) has proposed an analysis of direct interrogative on the inanimate subject that sheds light on the detached elements near the embedded in situ interrogatives. She proposes a grammatical and not a stylistic justification, as the detached turns of phrase (c’est quoi, le N ? or qu’est-ce que c’est, un N ?) are distributed according to the degree of referentiality of the subject: the turn of phrase qu’est-ce que c’est is used with noun phrases of generic value, often with an indefinite article, acting as requests for general definition (qu’est-ce que c’est, comme sorte de chose ?), while the turn c’est quoi has a clearly deictic value, aiming to elucidate a specific term present in the context (c’est quoi, cette chose?) (Blanche-Benveniste Reference Blanche-Benveniste1997b: 143–144).

In 2007, half of our data from Reunion Island (Ledegen, Reference Ledegen2007a) showed detachments, especially placed on the right (14 out of 25 occurrences of embedded in situ clause), including eight noun phrases introduced by a definite article and three with an indefinite article. The FDLQ data reveal the same organisation,Footnote 53 in an even more massive way, as shows Figure 3:

The majority of dislocations are placed on the right, and two thirds are with a determined noun phrase.

Figure 3. Dislocations in the embedded in situ clauses with quoi in FDLQFootnote 55 .

Once again, the literary corpus reveals overuse: among six left dislocations, three come from this particular corpus, with two remarkable examples cumulating two dislocations (as in ex. 43, subject of the main clause, and dislocation of the demonstrative pronoun c’, subject of the embedded clause) and 45 (twice dislocation of the demonstrative pronoun c’, subject of the embedded clause) and one example positioning the dislocation at the beginning of the embedded clause (as in ex. 44, dislocation of the demonstrative pronoun c’, subject of the embedded clause), a sequence that is not attested in the oral corpora:

The literary corpus again shows features that are stereotypical of the spoken language, but not actually attested structures.

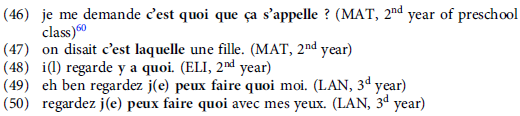

6. A NEW PIECE TO THE PUZZLE: ATTESTATION IN PRE-SCHOOl PRACTICES

The fact that the structure is practised by children before they go to school (cf. Palasis & Faure, in this volume) makes it possible to posit that the embedded in situ clause constitutes a feature of “primary knowledge of grammar”, i.e. the “initial knowledge mastered by children before the age of primary school” (Blanche-Benveniste Reference Blanche-Benveniste1990: 52), supplemented or replaced subsequently at school, where the “second knowledge of grammar” is learned (Blanche-Benveniste Reference Blanche-Benveniste1990: 52). Secova also finds more embedded in situ clauses used by the youngest speakers of the PMF-study (10–14 years old),Footnote 56 and supposes that “la forme standard est majoritairement acquise au fur et à mesure de l’instruction scolaire” (2017: 13). The structure seems to belong to those constructions that are “continually censored and, it seems, continually alive” (Blanche-Benveniste Reference Blanche-Benveniste1995: 128).

Palasis’ corpus (Reference Palasis2009),Footnote 57 recorded in France, attests the embedded in situ structureFootnote 58 with preschool children, more specifically three children in the second and third year of nursery school. It should be noted that they use various introduction verbs (se demander, dire, regarder Footnote 59 ) and embedded verbs (c’est, il y a, je + verb):

It should be noted that within this corpus, the form of the embedded clause with est-ce que is also attested:

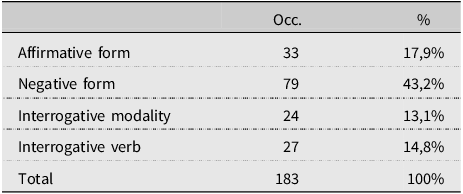

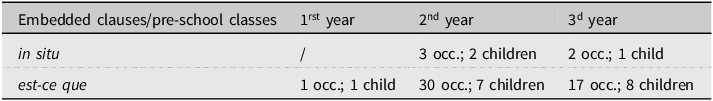

and much more extensively than the in situ form, as shown in Table 7 Footnote 61 .

Table 7. Non-standard embedded in situ and est-ce que clauses by pre-school children in Palasis’ corpus (2009)

These attestations with pre-school children reveal that the embedded in situ clause might be part of the self-regulation process (Chaudenson et al. Reference Chaudenson, Mougeon and Béniak1993: 38): they put into light this point of “weakness” or “fragility” of the interrogative in French (Chaudenson et al. Reference Chaudenson, Mougeon and Béniak1993: 6–7). The embedded in situ clause might belong to the panlectal variation of French studied by Chaudenson et al. who “[traquent] le français en liberté, à l’état de nature, indemne des contraintes que lui ont imposées les grammairiens du XVIIe siècle et que la tradition académique a sanctionnées”Footnote 62 (Manessy Reference Manessy, Chaudenson, Mougeon and Béniak1993: 3).

Moreover, Foulet’s historical analysis of interrogative forms reveals that the in situ order became widespread from the seventeenth century onwards: “De 1350 à 1650 l’effort de la langue a consisté principalement à faire triompher l’ordre sujet-verbe-complément, en d’autres termes à se débarrasser tant bien que mal des nombreuses inversions dont elle avait hérité et qui étaient désormais contraires à son génie”Footnote 63 (Foulet Reference Foulet1921: 262). The author considers that the turn of phrase “Votre père partira quand ?” constitutes “un développement très logique et au fond très naturel, dont la force peut un jour devenir irrésistible. Il entraînerait la langue encore plus loin de l’inversion : il en ferait disparaître jusqu’au souvenir même”Footnote 64 (Foulet Reference Foulet1921: 348). The in situ structure in direct interrogative then became widespread from the seventeenth century onwards, and could be, according to Ayres-Bennett, a case of “long-standing differences in written and spoken usage” (2004: 38). If the direct in situ structure remains rare in French texts between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, it is above all because it is non-standard: Ayres-Bennett (Reference Ayres-Bennett2004: 50–58) gives several examples in theatre texts and Mathieu (Reference Mathieu2009) attests an example in Diderot’s Le Rêve de d’Alembert (1784): “Mademoiselle de L’Espinasse: Et cette comparaison se fait où ? Bordeu.” (Mathieu Reference Mathieu2009: 59). The attestation of the embedded Wh- in situ structure on multiple terrains of the French-speaking world thus shows that “there is evidence for [its] usage in the French spoken in France at the time of the colonization” (Ayres-Bennett Reference Ayres-Bennett2004: 38).

A parallel could be drawn here with Anthony Kroch’s (1978) analysis of pronunciation, where he contrasts speakers of prestige dialects with speakers of vernaculars:

Our position […] is that prestige dialects resist phonetically motivated change and inherent variation because prestige speakers seek to mark themselves off as distinct from the common people. […] Thus, we are claiming that there is a particular ideological motivation at the origin of social dialect variation. This ideology causes the prestige dialect user to expend more energy in speaking than does the user of the popular vernacular. (1978: 30)

Also in syntax, the ordinary realisations constitute the common way of speaking, from which the dominant speakers try to differentiate themselves in certain contexts.

The embedded Wh- in situ clause seems to belong fully to these vernacular practices: it conforms to the evolutionary trends of French, where the reduction of declensions, the decumulation of synthetic forms, and the sequential syntax are attested (Guiraud Reference Guiraud1966; Lefeuvre & Rossi-Gensane Reference Lefeuvre and Rossi-Gensane2017). This fixity of word order thus has the joint advantage of maintaining the parallel between direct and indirect structures, and of allowing the interrogative status to be highlighted by the use of quoi rather than the form que, which can be taken for the relative structure.

7. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The embedded Wh- in situ clause turns out to be a long-lived and attested structure in view of its presence in many areas of the French-speaking world, a large part of which has in common being an ordinary French-speaking world dating from the seventeenth century. This vernacular turn of phrase corresponds to the evolutionary tendencies of French, and is structurally rather fixed: the embedded in situ clause is mainly constructed with c’est, and completed by dislocated elements; as for the introduction verbs, they are above all made up of verbs of knowledge, frequently in the negative or interrogative form (but also in an affirmative form (25%)), or of interrogative verbs.

The structure is attested in a very wide variety of French-speaking areas, without coming from the influence of other contact languages: its presence even in current Quebec literature and paraliterature reveals its real use; French and Quebec rap songs, which may be counter-standard, attest the structure too. Finally, the presence of the structure among preschool children confirms its existence in contexts of lesser normativity, also attested in certain ‘marginal’Footnote 65 francophone contexts (Acadia, Ontario, Newfoundland) where the structure is found as well (Ledegen Reference Ledegen2007c). These different elements not only make it possible to link the structure to “the ‘first’ knowledge of grammar” (Blanche-Benveniste Reference Blanche-Benveniste1990), but also to eliminate the categorisation of the turn of phrase as being exclusively of “register populaire”.

If the embedded in situ structure is more visible today, in sociolinguistic corpora, but also in the media, or in metalinguistic commentaries, it is, on the one hand, because of the informalisation of media and public practices,Footnote 66 and, on the other hand, because the corpora studied are more varied, and closer to the axis of communicative proximity (Koch & Oesterreicher Reference Koch and Oesterreicher2001): sociolinguistic interviews are more frequently organised in a free form than by following a strict questionnaireFootnote 67 that gave the respondent an exclusive responding role in a less ordinary way.

Our analysis of the previous data and the complementary analysis of the FDLQ corpora have allowed us to argument for the extended use of oral and written corpora, methodologically obtained in an ecological way, i.e. obtained within the framework of a strong inter-acquaintance and situated at the pole of communicative proximity (Koch & Oesterreicher Reference Koch and Oesterreicher2001), as used in the MPF project (Gadet Reference Gadet2017), rather than for corpora bringing back the ‘paradox of the observer’ (Labov). We therefore argument for the adoption of a communicative approach to variation (Guerin Reference Guerin2017) in the light of the “sociolinguistics of language” (Gadet & Guerin Reference Gadet and Guerin2021). These investigations might be built with different age groups, to compare youth to the other generations, in different places and departments, including Overseas Departments and the French-speaking world as a whole, and combine with epilinguistic discourses revealing the attitudes and representations of the speakers. We thus wish that a sociolinguistic inquiry combining the lessons from the MPF-Project with the investigations of the Francophone world by the project Phonologie du français contemporain (PFC) (Durand, Laks & Lyche Reference Durand, Laks and Lyche2009) may see the light soon.

In the future, in order to continue seeking for the embedded Wh- in situ clause, we will pursuit the exploration of oral and written corpora established in contexts of communicative proximity, and take a closer look at introductory verbs, particularly weak verbs (Blanche-Benveniste Reference Blanche-Benveniste1989; Blanche-Benveniste & Willems Reference Blanche-Benveniste and Willems2007, 2016), from a macro-syntactic perspective; moreover, the study of the extended contexts of each attestation observed here, in its complementarity with other embedded or non-embedded Wh- structures (standard, all the Wh- words…), will offer a promising perspective. Finally, an exploration in historical sociolinguistics of old judicial corpora containing ordinary reported speech (Dourdy & Spacagno Reference Dourdy and Spacagno2020; Dourdy Reference Dourdy2021) should allow us to date the rise of direct and embedded in situ interrogatives more precisely, and possibly attest the existence of the Wh- in situ in embedded form as early as the seventeenth century.

Competing interests declaration

None.

Corpora :

CHILDES French Palasis Corpus, 2006–…, sous la direction de Palasis Katerina, https://childes.talkbank.org/access/French/Palasis.html

CORPAIX, Groupe aixois de recherche en syntaxe (GARS), 1999, Corpus d’Aix-en-Provence. Non publié.

Fonds de données linguistiques du Québec, 2022, Centre de recherche interuniversitaire sur le français en usage au Québec (CRIFUQ), Université de Sherbrooke, https://fdlq.flsh.usherbrooke.ca (consulted on 8/2022) :

-

- Chroniques québécoises de langage (ChroQué), Claude Verreault, Louis Mercier & Wim Remysen (dirs) (1865 à 1996): Corpus of language columns published in the Quebec press from 1865 to 1996, dealing with language, more specifically with its good and bad uses. The corpus contains 7.936 entries by some forty columnists, 5.154.788 words.

Citations from the Corpus ChroQué (Chroniques québécoises), dir. by Wim Remysen and Hélène Cajolet-Laganière. Consulted on FDLQ-site in August 2022. [fdlq.usherbrooke.ca] :

-

- Blanchard, Étienne, Chronique du bon langage, La Presse, Montréal, 1er février 1919, p. 10, col. 1–5

-

- Lefranc, Paul [pseudonyme of Étienne Blanchard], Autour de la langue française, La Presse, Montréal, 16 juin 1923, p. 46

-

- Rosemont, Gilles de, Parlons correctement le français, La Patrie, Montréal, 15 août 1954, p. 28

-

- Barbaud, Philippe, Parler d’ici, La Presse Plus, Montréal, 18 mai 1985, p. 16

-

- Barbaud, Philippe, Parler d’ici, La Presse Plus, Montréal, 18 mai 1985, p. 16

-

- Barbaud, Philippe, Parler d’ici, La Presse Plus, Montréal, 11 janvier 1986, p. 16

-

- Corpus de littérature québécoise (CLIQ), Wim Remysen & Hélène Cajolet-Laganière (dirs): The corpus brings together the main Quebec literary works published between 1794 and 2022: literary texts written in French (not translated) by authors living in Quebec, including Quebecers of foreign origin. The genres are varied (narrative, theatrical, poetic and argumentative) as is the language (chastened, but also popular or spontaneous). The corpus contains 250 documents and 13.481.018 words.

Citations from Corpus CLIQ (Corpus de Littérature québécoise), dir. by Wim Remysen and Hélène Cajolet-Laganière. Consulted on FDLQ-site in August 2022. [fdlq.usherbrooke.ca] :

-

- Bernard, Christophe (2017), La bête creuse, Montréal, Le Quartanier.

-

- Turcotte, Élise (2016) [1991], Le bruit des choses vivantes, Montréal, Bibliothèque québécoise.

-

- Bienvenu, Sophie (2015) [2014], Chercher Sam, Montréal, Le Cheval d’août.

-

- Hamelin, Louis (2012) [2010], La constellation du Lynx, Montréal, Boréal.

-

- Cloutier, Joseph (1925), L’erreur de Pierre Giroir : roman, Québec, Imprimerie « Le Soleil ».

-

- Ébullition : le français québécois dans les bulles, Anna Giaufret, Philippe Rioux et Wim Remysen (dirs): This corpus is a representative selection of Quebecois comics from 1904 to 2022 (serials published in the print media, albums). The comic strip is “a genre that offers a stylised and contextualised representation of spoken language that allows us to study both the practice of the language and the representations that surround it” (presentation on fdlq.usherbrooke.ca). The corpus contains 15 documents and 72.992 words.

-

- JournaLangue2013 : langue et journalisme au Québec, Franz Meier (dir.) (2011–2013): This corpus consists of 33 semi-structured interviews conducted with 32 professionals working in the Quebec print media from 2011 to 2013, as part of a sociolinguistic study focusing on the conception of language and language norms that exist in this environment. The corpus contains 33 documents and 249.553 words.

-

- Corpus sociolinguistique de l’Estrie, Normand Beauchemin, Pierre Martel & Michel Théoret (dirs) (1971–1974): Sociolinguistic interviews conducted in twenty localities in the Eastern Townships (approximately 60 kilometres around the city of Sherbrooke), a region at the intersection of the dialectal areas of Eastern and Western Quebec. A selection of 100 interviews, 50 of which were conducted with women and 50 with men, aged between 18 and 70, whose mother tongue was French and who were born and raised in their village, just like their parents. The corpus contains 100 documents (for each respondent) and 471.581 words.

-

- Corpus variationniste Hochelaga-Maisonneuve 2012, Hélène Blondeau, France Martineau, Mireille Tremblay & Yves Frenette (dirs) (2012): This corpus contains semi-directed interviews with participants aged 18 to 89, educated in French and living for at least five years in the Hochelaga-Maisonneuve district of Montreal; this corpus, which is part of the FRAN (Français en Amérique du Nord) corpus, allows for more in-depth diachronic comparisons with the uses attested in the Montreal corpora (Montreal 1971, 1984, 1995). The corpus contains 43 documents (for each respondent) and 930.638 words.

-

- Montréal 1984, Pierrette Thibault & Diane Vincent (dirs) (1984): The corpus contains 30 semi-structured interviews with half of the witnesses in the Montreal 1971 corpus (Sankoff & Cedergren Reference Sankoff and Cedergren1976) (i.e. 60 people), plus 12 young people, to study language change in real time. The corpus contains 30 documents (for each respondent) and 647.501 words.

-

- Montréal 1995, Diane Vincent, Marty Laforest & Guylaine Martel (dirs) (1995): This is the third and final part of a series of sociolinguistic surveys conducted in Montreal from the 1970s onwards, this corpus brings together interviews conducted with informants already met in 1971 and 1984 (14 people). The corpus contains 14 documents (for each respondent) and 361.366 words.

-

- Phonologie du français contemporain: corpus Québec (PFC-Québec), Marie-Hélène Côté (dir.) (2009–): Carried out within the framework of the Phonology of Contemporary French (PFC) project (see Durand et al. 2002), the PFC-Quebec corpus comprises a series of linguistic surveys conducted across the different regions of Quebec between 2009 and 2017. The data collected are used to illustrate and analyse French as spoken in Quebec at the beginning of the twenty-first century, with a particular focus on the regional, generational and stylistic variation that affects it: each witness is invited to participate in two conversations, one formal and one informal, and to perform three reading tasks (reading a follow-up text and two word lists). The corpus contains 68 documents (for each respondent) and 364.119 words.

Citations from the sociolinguistic oral corpus, dir. by Wim Remysen and Hélène Cajolet-Laganière. Consulted on FDLQ-site in August 2022. [fdlq.usherbrooke.ca] :

-

- Vincent, Diane, Marty Laforest et Guylaine Martel (1995), « Entrevue Paul G., 2’95 ». Cité dans Corpus Montréal 1995. [Montréal1995]

-

- Thibault, Pierrette et Diane Vincent (1984), « Entrevue Christine Q, 4’84 ». Cité dans Corpus Montréal 1984. [Montréal1984]

-

- Thibault, Pierrette et Diane Vincent (1984), « Entrevue Marcel V., 46’84 ». Cité dans Corpus Montréal 1984. [Montréal1984]

-

- Blondeau, Hélène, France Martineau, Mireille Tremblay et Yves Frenette (2012), « Entrevue Christine, 003F24 ». Cité dans Corpus Hochelaga-Maisonneuve 2012. [HoMa2012]

-

- Blondeau, Hélène, France Martineau, Mireille Tremblay et Yves Frenette (2014), « Entrevue Alex, 015M18 ». Cité dans Corpus Hochelaga-Maisonneuve 2012. [HoMa2012]

-

- Côté, Marie-Hélène (2009–), « Entretien guidé cqcbc1g, Montréal ». Cité dans Phonologie du français contemporain : corpus Québec (PFC-Québec). [PFC-Québec]

OFROM, 2012–2019, Corpus oral de français de Suisse romande, Avanzi, Mathieu, Béguelin, Marie-José & Diémoz, Federica (dirs), (since 2019, Corminboeuf, Gilles & Johnsen, Laure Anne (Dirs)), http://www.unine.ch/ofrom.

Parole de chat, Les gros mots 3, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cuhmj_eYt3k

APCOR, 2009–…, Corpus français de chansons de rap, sous la direction de Policka, Alena, Université Marazyk, République Tchèque, https://www.sketchengine.eu/rapcor-french-rap-corpus/

VALIRUN, 2000–…, Variétés linguistiques de La Réunion, sous la direction de G. Ledegen, partly on Cocoon (https://cocoon.huma-num.fr/exist/crdo/).