INTRODUCTION

This article offers an analysis of the historical evolution of labour relations in Portugal from the 1970s until the present, focusing on labour precarity and unemployment, and on the role of the state in dealing with it. We will argue that more often than not the phenomenon of unemployment is cyclical, implying that precarity and unemployment are two sides of the same coin in the current mode of production, and lead directly to a decrease in wage bills (direct income) and indirectly to a reduction in social costs (the welfare state). Among the multiple variables open to scrutiny (including education, training, taxation, direct creation of public sector jobs, and legislation), we will focus especially on how workers’ social security and welfare state funds were put to use in this period, to mitigate in political as well as social terms the social regression condoned when employment rights were curtailed and labour conditions worsened. The Ministry of Labour and Social Security and its Institute of Employment and Training were responsible, along with legislative changes approved by Portugal’s parliament and European Union (EU) regulations, for managing the workforce in that direction. There were legislative changes in 1976 that introduced short-term contracts, which had been illegal in 1974–1975; wholesale redundancies were facilitated in 1987 and early retirement in 1991. Further changes came in 2003, 2009, and 2012, which did not take into consideration piecework wages in calculating income and reduced the value of redundancy payments by more than half.

Portugal once had a policy of universal welfare with no obligation to prove poverty or unemployment to gain access to benefits – maintained by progressive taxation – for things such as health, education, and social provisions, including subsidized canteens for workers. However, since the 1990s, the policy has moved towards focused assistance, meaning it is now necessary to prove poverty to gain access to free healthcare, subsidized canteens or transport, and cheap electricity.Footnote 1 The new welfare policy might indeed have been intended to address social inequalities and promote reintegration into the labour market,Footnote 2 but our contention is that, first, the increase in compensatory and targeted social measures was actually conducive to increased job insecurity and was closely related to the deregulation of employment; second, the compensatory social programmes were created simultaneously with the abolition of free access to health and education in the 1990s. The new policy simply endorsed the principle of “the user pays”. Most remarkable among the legal measures dealing with labour flexibility since 1985–1987 were the facilitation of collective dismissal and the use of the social security fund to compensate for redundancy. Then, especially with further legislative changes in 2003 and 2009, it became easier to dismiss individuals. One of the social outcomes of the changes can be seen in the Gini index, which fell from 0.316 in 1974 to 0.174 in 1978, when it reached its lowest level due to the “employment for all” policy of the 1974–1975 revolution. However, with inequality growing thereafter, the index rose to 0.210 in 1983.Footnote 3 Since then it has risen to a figure of 0.338 today, one of the highest in the EU, but caused by the “competitiveness of low wages” according to an analysis by the Bank of Portugal.Footnote 4 Over the same period, exports increased exponentially from a total of twenty billion euros in 1995 to sixty billion in 2014. The report by the Governor of the Bank of Portugal declared that the transformation in growth was export-driven.Footnote 5

This article begins with a discussion of the notion of labour precarity, adducing several definitions of what is a controversial concept that, until recently, had remained outside the scope of formal studies. The concept of precarity has been subjected to different definitions within the framework of labour relations studies and projects. Inasmuch as it displays each country’s distinct reality, the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations is likely to make a decisive contribution to the debate on the concept and its history. We will also discuss the concept of real versus official unemployment, and relevant data will be compared with those from the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations.

Later, we will examine the historical background to the changes in labour relations that have taken place in the past five decades, highlighting the occasions when change was abrupt (1974–1975, 1986–1989, and 2012–2014), but also the gradual transformations that occurred throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the present century. Recognizing gradual change is equally important to understanding the historical development of the state’s role as far as precarity and unemployment are concerned. Furthermore, we will point out that, in this specific instance, the state acted upon the link between protected, precarious and retired workers, making use of social and welfare state funds (net social income) to do so. In defining those changes affecting the role of the state, reference will be made to the relevance of Portugal’s position, both regionally and in the context of globalization (as well as to that of the completion of a global labour market) – namely its joining the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1986.

Finally, we will compare developments with those in Sweden in order to highlight the similarities in both processes, albeit at different stages, both in terms of economic development and the social conditions and distinctive features of the workforce.

PRECARITY AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Throughout the past two decades, labour market researchers in southern Europe and Latin America have discussed the concept of labour precarity in the light of the exponential increase in the number of workers facing labour precarity since the end of the 1980s. Similarly, the concept of unemployment has aroused academic controversy, so we will underline the major debates related to agreeing definitions of the two social phenomena and examine the data available for both.

In recent decades, many authors, including Callaghan and Hartmann,Footnote 6 Farber,Footnote 7 Hodson,Footnote 8 and Van der Linden,Footnote 9 have worked with the idea of precarity. A feature recurring in most of their work is a tendency to conflate precarious labour relations, distinct national legal system features and workforce mobility.

As defined by Charles and Chris Tilly, “work” includes any human effort adding use value to goods and services.Footnote 10 Ricardo Antunes, the Brazilian sociologist who coined the concept of a new morphology of the working class as the class-that-works-for-a-living, points out that in Western countries the main dynamic of the labour market has seen decreased regulation of work and increased precarity, which are inextricably linked to subcontracting within a flexible business model.Footnote 11

At the height of the outbreak of the most recent global crisis, that model became broader and induced even greater erosion of contracted and regulated labour of the type that had been most common throughout the twentieth century, namely Taylorist/Fordist labour.Footnote 12 Such relatively more formalized work has been replaced by several different kinds of informality and precarization – outsourced work in all its wide diversity, including “cooperativism”, “entrepreneurship”, and “voluntary work”.

Antunes has emphasized that the class-that-works-for-a-living is irretrievably interconnected, regardless of type of employment: “[…] by then, the two most noticeable and relevant focal points of the Portuguese working class were surfacing: those who had been forced into precarization and the working class that had inherited the welfare state and Fordism”.Footnote 13

The close link between flexible modes of production and precarity, as well as its impact in terms of wrecking the whole workforce, has been pointed out by Castillo,Footnote 14 HuwsFootnote 15 – who applied it to the “cyber proletariat” – and Mészáros,Footnote 16 among others. According to Felstead and Jewson, in the USA more than half of net employment growth was related to precarious labour.Footnote 17

Graça Druck has devised a typology of precarization: (i) procedures aimed at commodifying the workforce, resulting in a heterogeneous and segmented labour market, characterized by structural vulnerability and precarious modes of integration, with contracts depriving workers of any social protection whatsoever; (ii) labour planning and management standards that have brought about extremely precarious conditions through increased workloads (setting impossible targets, extending working hours, flexibility, etc.); (iii) labour not legally protected, and unfavourable health and safety conditions – the outcome of management standards that despise vital training, information on hazards, collective preventive measures, etc.; (iv) unemployed status and the constant threat of losing one’s job; (v) weakened trade unions, methods of resistance, and workers’ representation, because of competition, heterogeneity, and splits, against a background of union obliteration caused chiefly by outsourcing practices.Footnote 18

Several researchers have argued that precarity, or casualization, is a new phenomenon – in Portugal it has been around for about thirty years – involving a historically circumscribed definition: absence of the right to work in the post-revolutionary period 1982–2014, in contrast to 1974–1975, when the right to have a job was legally protected by the Constitution. We argue in this paper that the absence of the right to work, here understood in three ways (no right to work, lack of protection from dismissal, and no compensation for dismissal) is not a new phenomenon in Portuguese capitalist development. Historically, since the mid-nineteenth century, it has been the rule rather than the exception.

In our work,Footnote 19 we suggest a definition of precarity that differentiates precarization from contingent employment. Contingency, or switching between unprotected work and unemployment, is not the sole qualitative variable distinguishing twenty-first-century from nineteenth-century casual work. The concept of precarity is different today from the forms of lack of employment rights prevailing in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Precarity in Portugal is a concept that encapsulates other features besides the lack of any right to work and became very widespread during the period of the social pact (1974–1986). It includes the prospect of social regression (and not only of social immobility), and its management as a social phenomenon is heavily dependent on the workers’ savings fund (social security) and the family wage. Today it assumes multiple forms, including false self-employment (“green invoices”, the popular term for the invoices sent by autonomous workers on piece rates), small businesses, cooperatives, outsourcing, and piecework.

Thus, the concept of precarity is defined based on its opposite, protected work, de facto or de jure. What is involved is an analysis of employment security, which may derive from legal protection or skills training rather than from the conditions under which the work is performed – for instance, working in a mine can be physically precarious, because it is dangerous – but is not necessarily contingent with regard to protection against redundancy. That being so, precarity does not depend on any lack of good hygienic conditions, physical safety, or mental health but is purely a matter of the mobility of a workforce perpetually facing either precarity or unemployment. There is a direct link between precarity and unemployment. However, structural precarization of employment and unemployment are two sides of the same coin, since the same worker is caught in a cycle of precarious employment for part of the year followed by unemployment the rest of the year. For unions and state policy it is essential to understand this point.

In Portugal after the 1974 Carnation Revolution, to work became an absolute right, so that whoever is deprived of that right becomes precarious. It was enshrined in Article 58 of the 1976 ConstitutionFootnote 20 (the social pact), but its actual implementation relied in fact upon employers’ concessions and workers’ resistance, as well as on how the social pact was operated under the democratic-representative system.Footnote 21 The right to work in Portugal was introduced legally and socially as a universal human right (the right to survival) unfolding around three concepts: everyone has the right to work, everyone is entitled to protection from dismissal and, finally, everyone is entitled to protection if they are involuntarily unemployed.Footnote 22

Precarious workers include therefore a wide range of labour relations, quite distinct in their legal outlook but sharing the ease by which workers can be dismissed. The category of precarious workers comprises 1) workers on fixed-term contracts; 2) most workers paid on a piecework basis (freelancer “green invoices”, self-employed); 3) those on student grants, interns, and first-job contracts (all funded by the state for a fixed term, assuming the workers are being trained, even though they are actually carrying out paid work); 4) public-sector workers whose contracts are protected, albeit legally subjected to special mobility status (they can be relocated from different cities or jobs within the public sector) or possible dismissal; and 5) workers with permanent contracts whose redundancy pay (compensation for dismissal) was reduced, exposing them to easier dismissal. We have extended the concept of precarity here to include a specific class of small-scale entrepreneurs: in our opinion, in Portugal some precarious workers are labelled self-employed entrepreneurs although they are in essence normally employed workers. Besides “green invoice” workers, those on student grants, and interns, there are more controversial instances such as small business owners who are, in fact, workers. They might technically own a “business”, usually founded after a larger company had been dismembered and begun employing its original workers as outsourced labour. The result is, of course, that workers actually remain employed by and are dependent on the same larger companies while themselves bearing all the costs their former employers are no longer obliged to meet: social security, production stoppages, etc. Capital flows through these small companies but does not accumulate in them, so that their income is “barely enough to make ends meet” – often meaning just barely enough to cover running costs. Some might indeed be true small business proprietors genuinely in competition with others, but a good number are ordinary workers who are really precarious despite being officially labelled as operators of small businesses. Ultimately, the models applied by the Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE, National Statistical Office) do not go beyond the scope of formal and legal frameworks to allow us to see who really is in labour relationships equivalent to employer and employee, as far as small businesses are concerned. Finally, some contracts, whether fixed-term or even for piecework, imply a workforce that could not easily be replaced – doctors, for instance – and therefore were not precarious because for them neither mobility, nor intensification would lead to unemployment. So it is true that not all mobility is precarious, although there are certain legally protected labour relations, including those of some business holders, that embody precarious work.

Discussing such concepts is paramount to assessing their reality throughout history, as well as their current prevalence, and we shall pinpoint below how deeply methodology affects the data on the general workforce.

If we look at the whole population of Portugal broken down by broad age groups for our period, we notice a substantial variation both in young people and the elderly. The proportion of young people fell steadily, from 29.2 per cent in 1960 to 14.9 per cent in 2011, while the proportion of elderly rose, also steadily, from eight per cent in 1960 to nineteen per cent in 2011. Nevertheless, the age group of people fit for work (aged twelve to sixty-four in 1991 and fifteen to sixty-five in 2001 and 2011) remained noticeably stable. The lowest figure was 61.9 per cent in 1970, with a peak of 67.7 per cent in 2001. Such figures are likely to trigger social repercussions. For instance, from the point of view of social security, spending on younger groups would be replaced by spending on the elderly, but the figures illustrate something else that is rather important. The population available for work has risen from 1960 until today, for the most part because of the number of women joining the labour market. Another change must be stressed, that in education: in 1970 there were about 30,000 university graduates, in 2012 there were 1.3 million.

By 1970, market wage earners represented 14.51 per cent of all labour relations, a figure that had risen to 14.70 per cent by 1981. Those employed outside the market (that is, working for the state, NGOs, the church, or the armed forces, bearing in mind that state and market are of course related spheres) made up only 12.87 per cent of the whole population in 1971. By 1981, however, they accounted for 15.26 per cent, with the nationalizations carried out throughout the revolutionary years of 1974 and 1975 as well as the expansion of state agencies as a result of urbanization being the primary factors behind that rise. In 1981, nationalized sector personnel represented thirteen per cent of those employed (salaried) in companies, and about ninety-six per cent in the electricity-, gas-, and water-supply industries, sixty-nine per cent in communications and transport and fifty-seven per cent in banking and insurance. By 1982, “state-owned enterprises” accounted for over twenty per cent of the whole national economy, the highest figure among all OECD members.Footnote 23

As far as economic activity is concerned, the INE divides the population into two large groups, the working and non-working populations. The “active population” comprises those both employed and unemployed who were older than twelve at the time of the 1991 census or older than fifteen in 2001 and 2011. Everyone else is classed as “inactive”, so those younger than twelve or fifteen, depending on the census, domestic workers, students, retired people and pensioners, those incapacitated for work, and others, including anyone available for work regardless of having been out of the workforce for a long time. Nonetheless, it must be stressed that when it comes to those unemployed the concept of active and inactive populations in the census is strictly linked to their status, or lack of it, as effective or potential market producers. The taxonomy of the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations includes both market and non-market producers as active populations, as long as they effectively produce or perform services. The rest are then labelled inactive. There are then two considerable differences in the methodologies employed by the census and the taxonomy in that the taxonomy regards the unemployed as inactive, whereas domestic workers are labelled active.

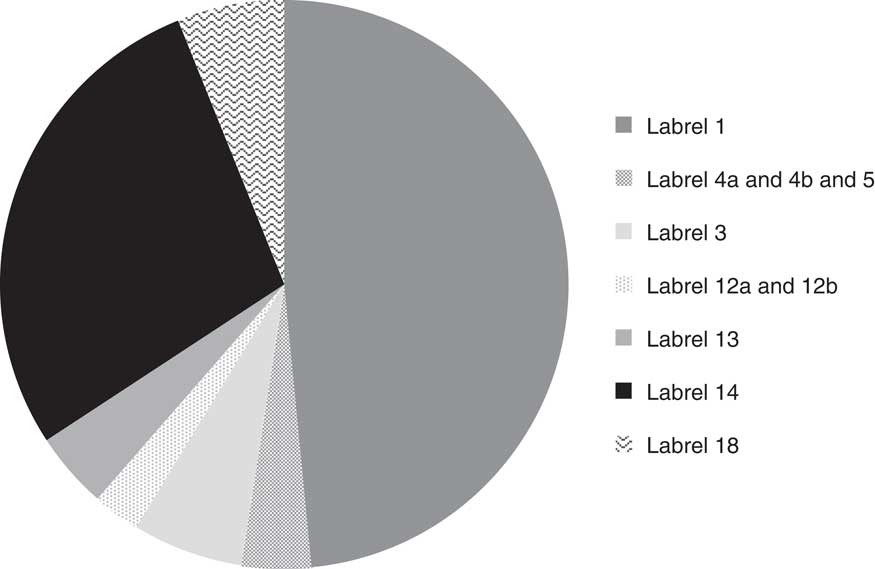

Both the INE and EU member states follow the International Labour Organization (ILO) in defining an unemployed person as anyone old but not undertaking paid (or unpaid) work of any kind despite being available and actively seeking employment. The notion of “actively seeking employment” consists of a set of procedures that, according to the INE’s employment survey, includes being registered at a job centre, applying to employers and attending job interviews. If a potential worker fails to fulfil such requirements, they will automatically be labelled available but inactive, or despondent. Economist Eugénio Rosa challenges the definition of “available but inactive” and includes it instead as part of the “unemployed” category, to which he adds those visibly under-employed; that is, “the number of individuals aged at least fifteen who, during the reference period, had a job comprising less working time than would be expected for their assigned operating position and declare themselves willing to work longer hours”.Footnote 24 The gap between inactive and unemployed people led to a clear discrepancy in 2014 between figures on official unemployment (thirteen per cent) and real unemployment (23.7 per cent). As we have explained, the Global Collaboratory uses a different definition of unemployment (labour relation 3), according to which unemployment was six per cent in 2011 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Labour relations, Portugal 2011, according to the taxonomy of the Collaboratory Source: Ana Rajado, Cátia Teixeira, and Joana Alcântara, “Taxonomia das Relações Laborais em Portugal, 1930–2011”, O Social em Questão, XVIII:4 (2015), pp. 41–58, 56–57, available at http://osocialemquestao.ser.puc-rio.br/media/OSQ_34_2_Rajado_Teixeira_Alcantara_Varela.pdf, last accessed 12 April 2016.

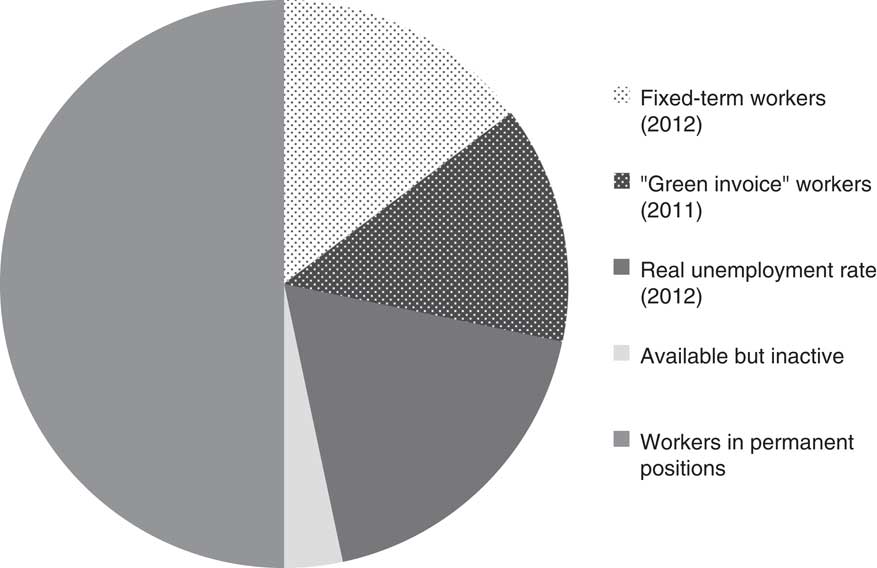

According to Eurostat, in the fourth quarter of 2012 the proportion of fixed-term workers among employed persons was higher in Portugal (20.3 per cent) than in almost any other country. In absolute terms, this amounted to 900,000 fixed-term workers. In order better to assess the amount of precarious work in Portugal, we should have to include the proportion of workers paid for piecework (“green invoices”). Although there are no such data available for the fourth quarter of 2012, we can estimate it from the 2011 census, which gives a figure of 827,000 precarious “green invoice” workers doing piecework. Those two types of fringe employment covered over 1.5 million precarious workers out of an “active population” of 5,658 million workers. That figure comprises an active population according to the INE of 5,455 million, employed and unemployed, plus 203,000 considered available but inactive, and contrasts with a real unemployment rate of 19.9 per cent (1,126,000) in the fourth quarter of 2012. Thus, in 2012 half the workforce faced either precarity or unemployment (see Figure 2) – precarity having threatened less than half the workforce in previous decades, when unemployment was never higher than seven per cent. In addition, on average, workers on permanent contracts earned sixteen per cent more than those on fixed-term contracts, while in a study published in 2008 Eugénio Rosa estimated that on average a precarious worker earned thirty-seven per cent less than one on an open-ended contract.Footnote 25 Furthermore, only twelve per cent of fixed-term contracts were subsequently converted into permanent contracts.Footnote 26

Figure 2 Precarious work in Portugal, 2011 and 2012.

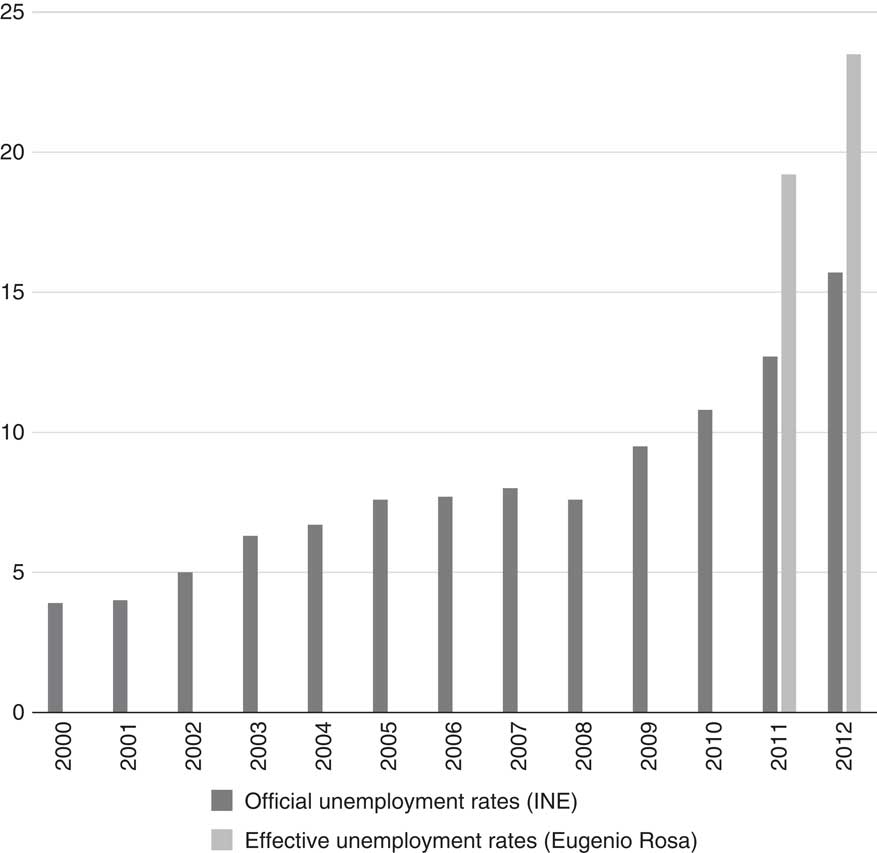

Figure 3 gives official unemployment figures, illustrating the impact in times of economic crisis, and how unemployment has been counter cyclical since the 1980s. The figure for 2012 was unprecedented. It is worth mentioning that this figure, as well as all the others, relates solely to the active population;Footnote 27 still, it depicts clearly the impact of the unemployment cycle on the unemployed population, as well as the upward trend on which that cycle is superimposed. Plainly, in the last cycle, triggered by the 2008 crisis, unemployment figures were unprecedentedly high: 16.2 per cent in 2012.

Figure 3 Unemployment rates in Portugal, 2000–2012.

THE ROLE OF THE STATE

Today, neither statistics, nor the legal framework convey the full complexity of the kinds of state intervention that shape labour relations or employment conditions, both directly and indirectly. The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations is an ambitious attempt to categorize labour relations, which are becoming increasingly complex due to urbanization, education and globalization. Here, we shall focus mainly on the relationship between the state and the workforce. Understandably, this topic does not exhaust the whole multiplicity of variables binding the state to labour relations – for instance, in terms of preserving the health of the workforce (healthcare) or training it (education and vocational training); fiscal policy; public debt and public-sector budgets; public areas and amenities; or transport management. Our research into the management of labour precarity and unemployment and its relationship to the welfare state, especially with respect to social security, is an important part of a wide and complex network of relationships between state and workforce.

Currently prevailing explanations critical of neoliberalism have emphasized the fact that the period since the 1970s has been characterized by increased deregulation of the labour market, along with a decreased role for the state in the economy. In this article, we claim that labour precarity and unemployment amount to direct state intervention, and that it is increasing rather than being reduced. Close attention must be paid to changes in state intervention, instead of taking for granted any explanations presuming a steady decrease in that role.Footnote 28 Such changes might be seen in social dialogue mechanisms, including state, union federations, and employers’ associations; targeted and non-universal social welfare policies to counterbalance the effects of rising unemployment and low wages; and changes in the legal framework regulating labour precarity. We should mention here our particular insistence that we see labour flexibility as being typified by a type of state regulation that promotes it. We look, too, at the close similarities between Portugal and Sweden, despite slight differences in the years of implementation, with Portugal joining the EU earlier (1986) than Sweden (1995), and the different figures for the cost of consumer goods and the different living standards enjoyed by workers in these two countries.

In the past four decades there has been no reduction in the state’s role as a direct employer – in fact, it has increased. In 1979, there were 383,000 civil servants in a total working population of nearly four million people. By 2014, there were 665,620 civil servants out of a total 4.5 million people employed.Footnote 29 It should be noted that the country’s active population has risen significantly since the 1970s. It was 3.91 million in 1974, peaking at 5,534 million in 2008; in 2015 it was 5,225 million. Concomitantly, unemployment has risen. With 23.7 per cent of the whole population unemployed, the figure for 2015 was the highest in the country’s history.Footnote 30

Unemployment is a historical thing, and is derived from choices related to a certain means of accumulation and global competition based on reducing unit labour costs. In Europe, the unemployment of the past four decades must be regarded as a complex phenomenon strictly linked to labour market restructuring and not to the “end of labour”.Footnote 31 Authors in Portugal from the whole spectrum of economic thinking all agree that unemployment is nowadays the main cause of pressure on wages. We argue that, despite a minority of the workforce who tend to leave the labour market never to return, in most cases the data reveal that unemployment is cyclical and that there is a direct connection between unemployment and labour precarity: they are two sides of the same coin.

SOCIAL ASSISTANCE AND PRECARITY

Organized mutual institutions or solidarity cooperatives have existed since the nineteenth century, but the Portuguese welfare state and the qualitative and quantitative generalization of social rights came late, thirty years after France and Britain in 1945 with the Beveridge Plan of 1942. But such institutions were born partly out of causes similar to those that gave rise to the welfare states in western and northern Europe, from the “concerns of the economic and political system with industrialization (including demographic explosion, social and political conflicts, economic crises)”, as pointed out by Luís Graça.Footnote 32 Ângelo RibeiroFootnote 33 noted that between 1926 and 1974 “human rights, taken as the civil liberties in their multiple aspects of civil, political, social, economic, and cultural rights that make a country a ‘state of law’, were practically non-existent in Portugal”. All researchers agree that the pension system during the Estado Novo (the forty-eight-year period of dictatorship under Salazar and Caetano) was both restricted and offered little.Footnote 34 All other indicators of well-being – life expectancy, health, infant mortality, literacy and education, leisure – were equivalent to those in underdeveloped and backward countries. Total state spending in Portugal on social issues in 1973 was 4.4 per cent of total GDP, while in Britain it was 13.9 per cent, in Italy 10.6 per cent, and 15.4 per cent in Denmark.Footnote 35 Portugal was to undergo fundamental changes after the 1974–1975 revolution, which brought to an end the oldest dictatorship in Europe, under which a system of forced labour had persisted in its colonies. Unable to reform itself, the Portuguese regime collapsed on its backboneFootnote 36 in a coup d’état led by middle-ranking army officers, but which was followed by social revolution. Then, one-third of the population (three million people) participated in workers’ and residents’ committees, with state expenditure at a correspondingly high level; today, expenditure on education, health and social security, the state’s social functions, is equivalent to 18.1 per cent of GDP.Footnote 37

In the aftermath of 25 April 1974, a huge demonstration forced the dissolution of the Ministry for Guilds and Social Welfare, which was renamed the Ministry for Labour and Social Security,Footnote 38 so that in 1974 welfare was replaced by security. Social security encompasses two main areas, namely pensions, funded by deductions from workers’ wages or, for non-contributory pensions, by transfers from the national budget, and so-called social welfare policies, aimed at tackling poverty and involuntary unemployment. The former would not be feasible without the historical rise in wages, while the latter were implemented on a large scale only in the 1980s. Two interdependent ideas form the foundation of the universal social security system created in 1974 and 1975. First was the transfer of income from capital to labour. It was the most thorough instance of this in contemporary Portugal, and according to official data the proportion of income accounted for by labour grew from forty-nine per cent before the revolution to sixty-seven per cent after, while the proportion of income from capital fell, from fifty-two to thirty-three per cent.Footnote 39 The second was a public commitment to universal social protection and solidarity, which put an end to discriminatory and discretionary schemes and widened the scope of social protection. Universal protection was established, by means of education, healthcare and pensions, to maintain and train the workforce, and support was given to such things as culture, sport and general leisure. The average annual state pension rose more than fifty per cent between 1973 and 1975.Footnote 40

A look at the figures reveals that due in part to inflation real direct wages actually fell in 1974 and 1975. Nonetheless, for social wages, i.e. the benefits provided by the welfare state and social security, the advantages were clear. It should be stressed that not only did wages rise, income disparities, too, were reduced, so that the gap between higher and lower incomes narrowed.Footnote 41 We must emphasize this point in particular, that the greatest impact of the rise in incomes in this period was not on direct wages, but on social wages; that is to say, on the welfare state. That being so, and social contributions aside, wages were therefore lower in 1983 than in 1973.Footnote 42 There was precarity in the earlier period, too, but as unemployment remained residual – although still cyclical – between 1970 and 1990 (regardless of a peak following the 1982–1984 crisis), state measures for the management and support of unemployment were similarly residual until 1986.

In the 1980s, the end of the social pact initiated a period of social dialogue. The Conselho Económico Social (Social Economic Committee) was established in 1986, in a tripartite configuration of employees, employers, and the state, similar to the Swedish model. It was therefore a neo-corporative structure, switching company- or factory-based conflicts between employers and employees to a situation in which they were negotiated and prevented, as pointed out by StoleroffFootnote 43 and Stråth.Footnote 44 In Sweden, a very similar mechanism of “pre-negotiating” before official negotiations took place was established. Over the past twenty years the new policy has been steadily expanded and extended to include unemployment; this expansion has been financed by funds comprising contributions to retirement pensions. Marques argues that within the EEC (later EU) and the single market framework various measures were taken, such as “unemployment benefits, early retirement due to unemployment, explicit support for restructuring, active labour market policies, and professional training”.Footnote 45 As mentioned by Hespanha et al., the setting up of the Fundo de Estabilização Financeira (Financial Stabilization Fund) and the amalgamation of the social security and the unemployment funds were measures simply heralding the relationship between “unemployment problems and the need to maximize collected contributions”.Footnote 46

In Portugal, such changes took place only because there was a specific historical juncture (the economic crises of 1981–1984) characterized by the following near simultaneous developments. First, there was widespread social conflict involving some minor trade unions, in steelworking and heavy industry, who were opposed to the social dialogue. Their defeat in the 1984–1986 strikes had a symbolic effect that spread to other sectors, and StråthFootnote 47 notes that a similar effect was felt in Britain, Germany, and Scandinavia. Second, trade unions committed themselves strongly to negotiations instead of to conflict. Unlike during the revolution, they no longer saw the state as an opponent, but – rather than companies – as an arbiter to whom proposals should be addressed.Footnote 48 Moreover, the working and middle classes gained wider access to consumer goods as Portuguese markets were opened up to Asian businesses and pressure was applied to wages on a worldwide scale. A fourth factor, and in our opinion pivotal, was the deployment of the social security fund to manage precarity and unemployment, providing a social cushion. This move complied with the World Bank research guidelines on assistance, inflation, and unemploymentFootnote 49 aimed at preventing extreme poverty, inequality, and social decline. The deployment was negotiated case by case by way of early retirement and was mostly accepted by the unions.Footnote 50 The process affected millions of workers throughout Europe, from Britain to Portugal, and Sweden to Spain. In return, “acquired rights” were left unaffected for those who already had them, while recently employed workers were suspended or made subject to precarity schemes. Finally, in southern Europe – and this was not a relevant element in Sweden nor in most developed European countries – young people began to join the labour market at a later stage. That naturally implied a decrease in most parents’ disposable income, because they had to support their children for longer. In Portugal nowadays, most unemployed people still rely first on their families for subsistence, with unemployment benefit coming second. All the same, in analysing the restructuring of the labour market since the 1980s we noted another important phenomenon, namely that although youth unemployment was high it was in the older segments of the working population that unemployment was more structural. There was a tendency for people over forty-five with fewer than six years of education to be permanently removed from the labour market, in an age/training selection process we call “workforce eugenics”.

One of the most relevant events in this interwoven relationship between the social security fund and the management of unemploymentFootnote 51 was the introduction of unemployment benefit (Decree-Law no. 20/85 of 17 January 1985). Most salaried workers had been entitled to unemployment benefit since 1975 (Decree-Law no. 169–D/75 of 31 March 1975) but in 1985 the EEC forced the establishment of a new benefit combining the social security and unemployment funds (leading to an integrated social security contribution, implemented in 1986) into a single fund for both pensions and unemployment benefits. Moreover, a legal framework for early retirement, also mandatory under EU law (Decree-Law no. 261/91 of 25 July 1991),Footnote 52 was implemented, and permission was granted to exempt or reduce interest on social security debts owed by companies “in difficult economic situations or subject to special company rescue or creditor protection schemes” (since 1989, these schemes have taken on a variety of forms).

One aspect of this state management was the setting up of pension funds. Further, under Decree-Law no. 415/91 of 17 October 1991, a minimum income was established by 1996, which was subsequently replaced in 2003 by the social integration income. In the spirit of Scandinavian “flexicurity” or the German Hartz IV welfare reforms, “targeted assistance programmes” are being implemented all over Europe aimed at creating a more politically stable workforce, to avoid political conflicts between capital and labour and to ensure social harmony. In his article on Sweden in the present Special Issue, Max Koch reports a decrease in amounts allocated to individuals not returning to the labour market. Despite forty-seven per cent being in poverty in Portugal in 2014 (according to the UN definition), the number of social integration income beneficiaries fell from 526,382 in 2010 to 320,554 in 2014. Part of that state policy involves the Employment and Social Protection Programme (Decree-Law 84/2003 of 24 April 2003), which allows the period for claiming unemployment benefits to be shortened and gives access to early retirement resulting from unemployment, and access to social unemployment benefits. Another very important aspect of this intervention are the active labour market policies.Footnote 53 Since the end of the 1980s, mechanisms have been established whereby businesses can be exempted from making contributions. Initially, companies could be granted exemptions that could be extended for a period of up to three years if a worker were employed permanently. Currently, the PAE (Active Labour Market Policies) programme allows a company to employ a worker for six months on a precarious contract, with wages paid by the social security system. Such an employee may be dismissed at the end of the sixth month.Footnote 54 This scheme, along with mini-jobs, is widespread in Austria and Germany. Companies may choose to pay a fraction of the salary, with the remainder paid by partial unemployment benefit. In Portugal there are currently 160,000 workers, including outsourced labour both in private and state employment, affected by policies under which the state, through the social security system, pays up to seventy per cent of their salaries.Footnote 55

Finally, if companies resort to laying-off employees, or in the event of total or partial production stoppages, workers receive social security for up to six months. In many cases they are required to attend official vocational training, which is partially paid for by social security. The number of companies declaring “fake” lay-offs, meaning they file for bankruptcy after six months, is unknown. It is also the responsibility of the social security body to guarantee outstanding remuneration, if certain conditions are met. In 2008, the figure involved was 26 million euros; by 2011 it had risen to nearly 75 million euros.Footnote 56 According to Guedes and Pereira’s study, by the end of 2011 vocational training and active labour market policies, combined, accounted for 1.4 per cent of Portuguese GDP.Footnote 57

Social security, the densest component of the welfare state, has become a tangle of complex legislation affecting many sectors.Footnote 58 In general terms it includes retirement pensions (for workers who have contributed), minimum pensions, and allowances for disability, old age and widowhood; assistance programmes to help the workforce in times of need, such as when they are sick; access to education; subsidized canteens; and a minimum income (later known as social integration income). Nevertheless, there has been a concurrent exponential rise in poverty, and today forty-seven per cent of the Portuguese are poor, before social transfers; despite these transfers, this figure is still as high as eighteen per cent.

To recapitulate, in Portugal there are three parts to the social security system. The first is a contributory pension system based on a repartition system and on social contributions. The system has a surplus – it is the only budget in the overall national budget that has never been in deficit. The second is a non-contributory system designed after 1974–1975 mainly for peasants and domestic workers who had no social security benefits during the dictatorship. That fund had its origins in general taxation. The third is social protection, in principle intended to pay social benefits to impoverished and involuntarily unemployed workers. That fund, too, is financed from general taxation. Unemployment benefits are a statutory contribution, mandatory only for those on a permanent or fixed-term contract. However, some of the workers previously mentioned, including those on student grants, “green invoice” workers, and others, are trapped in forms of precarity and have no access to regular unemployment benefit. In April 2016, the official number of unemployed was 622,000, but just 250,000 received unemployment benefit.Footnote 59

The restructuring of employment, with increased precariousness, unemployment, and labour turnover took place at the same time as universal policies were replaced by targeted policies. After 1974, and during the 1980s, the welfare state was universal. The “unified education system” was free, from primary school to university, and the Portuguese national health service was entirely free for the entire population. Housing rents were “frozen”; by law, rents could not be increased for those tenancies that originated in the 1970s or 1980s. Moreover, such fixed-rent tenancies could be transferred to the tenants’ children. However, since the beginning of the 1990s there has been a major shift, with universal policies being replaced by focused ones. Free health care was now means tested, as was university education; and rents were liberalized after 2012–2013, with state subsidies only for those able to provide evidence of inability to pay. During the late 1980s and 1990s a range of unemployment assistance programmes were set up to supplement unemployment benefits. These included a minimum wage and “social unemployment benefit”. In theory, all of that should be covered by the tax system, but the contributory system, too, is having to pay for these programmes because the other funding systems are in permanent deficit. Furthermore, with the increase in precarity and unemployment the number of people in the contributory system and the level of their salaries are in dramatic decline. In 1988, the percentage of revenue accounted for by social security contributions was eighty-eight per cent; in 2000 it was 69.8 per cent and in 2012 35.1 per cent.Footnote 60

Ana Elizabete Mota, a professor of social work, has ascertained that targeted assistance policies aimed at those affected by lower wages and unemployment tend to become more prevalent in the exact proportion to that by which the welfare state is curtailed; that is to say, they increase only where universal social solidarity is destroyed.Footnote 61 Throughout the 1980s and 1990s the universal solidarity policies that assured the maintenance and training of the workforce were replaced by targeted policies that, while they ensured (biological) social reproduction, resulted in a subsequent fall in wages for all workers, contrary to initial intentions. Poverty and social inequality were the inevitable result. In the words of Pedro Hespanha, in this period the principle of “universality” was jeopardized.Footnote 62 Figuratively speaking, it amounts to “using parents’ wages to pay for their children’s unemployment”. Van der Linden adds that “many of the social provisions adopted after the Second World War were not supported at the expense of capital. In 1950, the United Nations’ Economic Survey of Europe stated that ‘the whole of the social security system was funded by a huge redistribution of wealth within the working class’”.Footnote 63

CONCLUSION

Paradoxically, what had been a historical gain – universal social security won in the revolutionary biennium of 1974–1975 – became, from the end of the 1980s and for political reasons, a social cushion to fund unemployment and precarity. Beforehand, in order to shape these new labour relations, the family wage was legitimized and families took it upon themselves to support their children for longer periods. Then, social security resources, and pension funds in particular, were systematically put to use to follow up the regulation of labour market flexibility by providing support by means of unemployment benefits, subsidies to business, support for lay-offs, and assistance programmes.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, universal solidarity policies, which ensured the maintenance (health, social security, and housing) and training (education) of the workforce, were replaced by targeted policies in which only the working poor and unemployed had free access to the social welfare provided by the state.

The process might have left Portuguese society deeply wounded, inasmuch as it resulted in what we believe to be a case of “workforce eugenics”. Young people earning low wages see their social (and biological) reproduction being put in jeopardy while their experience of life as adult wage earners is delayed. Scenarios have been proposed centred on an increase in the average lifespan,Footnote 64 when, in fact, the pivotal question concerns labour relations. Portugal has an economically active population of roughly 5.5 million people, with 2.5 million pensioners, both contributory and non-contributory. However, because of the state of labour relations and employment conditions, that pyramid has been inverted and half the workforce – there are three million people unemployed or in precarious jobs – has become passive, making little or no material contribution to the economy. This labour market inversion has come about because the state has set up a social cushion, channelling social security funds in a multitude of ways, so that, on the one hand, business is supported while, on the other, unemployment and assistance-based programmes are enacted.