Sugar-sweetened sodas, also known as sugary soft drinks, are the most consumed types of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB)(Reference Bleich, Vercammen and Koma1,Reference Ng, Ni Mhurchu and Jebb2) . In Europe, one in six (16 %) adolescents consumes soda every day(Reference Inchley, Currie and Budisavljevic3). This is of concern because a high soda intake of soda at a young age contributes to excessive weight gain(Reference Luger, Lafontan and Bes-Rastrollo4,Reference Vos, Kaar and Welsh5) and cardiometabolic risk(Reference Vos, Kaar and Welsh5). To reduce soda consumption, the WHO recommends taxing these beverages(6,7) . Since 2010, an increasing number of countries and jurisdictions (over forty five in 2020) have introduced such a tax(8,9) . Studying the impact of soda taxes in adolescents is important because (1) they are among the largest consumers of SSB worldwide(Reference Singh, Micha and Khatibzadeh10,Reference Azais-Braesco, Sluik and Maillot11) ; (2) food price and healthiness have a lower priority to them(Reference Monalisa, Frongillo and Blake12,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry13) and (3) poor dietary habits established in adolescence are likely to track into adulthood(Reference Craigie, Lake and Kelly14).

Econometric studies in the US estimated the price elasticity of demand for SSB at −1·2, implying that a tax raising the price by 20 % would reduce the consumption of SSB by 24 %(Reference Powell, Chriqui and Khan15). A recent meta-analysis using real-world data from six countries confirmed the previous estimation (price elasticity: −1·0) and showed that the higher the tax rate was the more the SSB consumption reduced(Reference Teng, Jones and Mizdrak16). However, most studies relied on sales or purchase data, often aggregated at the household level. Although this is a robust evaluation, it does not assess the differential impact of taxes across household members, especially adolescents. To this end, individual-level studies investigating whether post-tax SSB consumption was reduced compared with pre-tax consumption are useful, but most(Reference Silver, Ng and Ryan-Ibarra17–Reference Bleich, Dunn and Soto26) recruited only adults(Reference Silver, Ng and Ryan-Ibarra17–Reference Sanchez-Romero, Canto-Osorio and Gonzalez-Morales21). In addition, most studies assessed changes in SSB consumption in the year following the tax introduction(Reference Silver, Ng and Ryan-Ibarra17–Reference Zhong, Auchincloss and Lee19,Reference Royo-Bordonada, Fernandez-Escobar and Simon22–Reference Cawley, Frisvold and Hill24) , which limits evidence on long-term tax effects. Therefore, real-world data estimating the longer term effects of taxes on adolescents are needed to better understand their potential benefits.

Given the range of interventions addressing diet, it is essential when examining the effects of a soda tax to (1) know the pre-tax consumption trend; (2) compare the post-tax consumption evolution in a similar population not exposed to the tax and (3) be aware of the established diet-related interventions. Hence, we examined 16-year trends in daily, weekly and occasional soda consumption in six European countries that implemented a soda tax between 2001–2002 and 2017–2018. We also assessed whether changes in consumption of sugar-sweetened soda were different from those observed in neighbouring countries without such a tax (comparison countries). Our hypothesis was that the tax would be followed by a decline in daily soda consumption along with a rise in occasional consumption, indicating a shift favourable to health at the population level.

Methods

Study design and data sets

We used repeated cross-sectional data of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study(Reference Inchley, Currie and Cosma27), spanning five survey years: 2001–2002, 2005–2006, 2009–2010, 2013–2014 and 2017–2018. HBSC is an ongoing international school-based survey on health behaviours and well-being of adolescents aged 11, 13 and 15 years. The HBSC survey involves an increasing number of countries (up to forty seven in 2017–2018) that follow the same international protocol every 4 years(Reference Inchley, Currie and Cosma27). The sample size in each country is recommended to be at least 1500 per age group (precision of ±3 % for a 50 % prevalence)(Reference Inchley, Currie and Cosma27). Country-level teams recruited nationally representative samples, stratified by geo-political regions and school categories. They randomly selected one or several classes for each targeted age group in each randomly selected school. Adolescents voluntarily filled out an anonymous, standardised questionnaire after receiving instructions in class. Response rates at the school level (and pupil level for 2017–2018) varied by country and survey year (Additional file 1): e.g. 2017–2018 school rates ≥69 % in 6/12 countries (no data for Latvia) and pupil rates ≥71 % in 8/10 countries (no data for Sweden, Portugal and Spain). More detailed information about the HBSC methodology can be found elsewhere(Reference Inchley, Currie and Cosma27).

Selection of countries with a soda tax

From the literature(8,9,Reference Jysmä, Kosonen and Savolainen28–Reference Popkin and Ng30) and personal contacts with local experts, we identified six European countries that introduced or updated a national tax on soda between the first (2001–2002) and last (2017–2018) survey years, providing at least one time point before and after the tax was implemented. Included countries, by chronological order of tax implementation, were Latvia, Finland, Hungary, France, Belgium and Portugal. Other European countries, including the United Kingdom and Norway, implemented a tax, but this was after the most recent HBSC data collection. This search also allowed us to identify other diet-related public health interventions.

Table 1 describes soda taxes and implementation date(s) for each country(8,9,Reference Jysmä, Kosonen and Savolainen28,Reference Bíró29) . Tax sizes were heterogeneous across countries (€0·02/l to €0·22/l). Because most taxes are excise duties applied to manufacturers/importers (not consumers), the relative price increase may vary according to soda brands as well as places and volumes of purchase(Reference Colchero, Salgado and Unar-Munguia31). In Finland, France and Hungary, where such data are available, average tax rates were estimated at 20 % (€0·22/l)(Reference Jysmä, Kosonen and Savolainen28), 7–10 % (€0·07/l)(Reference Teng, Jones and Mizdrak16) and 5 % (€0·02/l)(Reference Teng, Jones and Mizdrak16), respectively.

Table 1 European countries with a soda tax introduced/updated between 2001–2002 and 2017–2018 and tax description(8,9,Reference Teng, Jones and Mizdrak16,Reference Jysmä, Kosonen and Savolainen28–Reference Popkin and Ng30)

* Excise tax is a duty levied on a particular product at point of manufacture (i.e. soda producers/importers), whereas sales taxes applied to end consumers at the point of purchase.

† 1 Euro ≈ 1 US dollar.

‡ World Bank data: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.KD.

§ Updated on 1 July 2018 (after 2017–2018 HBSC data collection).

Selection of comparison countries

For comparison, we selected neighbouring countries with similar demographic, economic and nutritional characteristics that did not implement a soda tax before 2017–2018. Thus, Latvia was matched to Lithuania; Finland to Sweden; Hungary to Poland; France to Germany and Italy; Belgium to the Netherlands and Portugal to Spain. The Netherlands has implemented a ‘consumption tax’ on sugary and diet sodas, fruit juices and mineral water since 2002(Reference Teng, Jones and Mizdrak16). Given that the tax is old, small (0·04 to 0·08/l) and applied across all drinks, we still considered the Netherlands as a relevant comparison country for Belgium between 2013–2014 and 2017–2018. France was matched to two comparison countries because this is a large country with diverse dietary habits between the north and the south(Reference Gazan, Bechaux and Crepet32). Additional file 2 shows the similarity between pairs of countries, based on ten indicators.

Sugar-sweetened soda consumption

A short FFQ (sFFQ) assessed soda consumption on a usual week. The general question was: ‘How many times a week do you usually eat or drink … ?’ and the item was phrased as follows: ‘Coke® or other soft drinks that contain sugar’(Reference Inchley, Currie and Cosma27). Adolescents could tick one answer among seven options: (1) ‘every day, more than once’; (2) ‘once a day, every day’; (3) ‘5–6 d a week’; (4) ‘2–4 d a week’; (5) ‘once a week’; (6) ‘less than once a week’ or (7) ‘never’(Reference Inchley, Currie and Cosma27). The sFFQ has been validated against 7-d food records in a similar sample of adolescents as ours (within the HBSC network), and reliability and validity were moderate(Reference Vereecken and Maes33,Reference Vereecken, Rossi and Giacchi34) . To make our results comparable to previous literature(Reference Sanchez-Romero, Canto-Osorio and Gonzalez-Morales21), we grouped soda consumers into three categories: daily (≥1x/d), weekly (1–6x/week) or occasional (<1x/week) consumers. Non-consumers were rare and categorised into occasional consumers.

Covariates: sex, age group, temperature

Sex and age are major determinants of soda consumption(Reference Inchley, Currie and Budisavljevic3). HBSC international databases include participants with complete data on sex (boys or girls). For our analyses, we excluded 11-year-old children to get more homogeneous samples (only adolescents attending secondary schools) and fewer missing data (more frequent among younger adolescents). Analyses were thus carried out on 13- and 15-year-olds. Variations in months of data collection were observed across survey years (within a country) and between matched countries. We, therefore, accounted for the mean temperature of the month and year at which each participant completed the questionnaire because SSB are more likely to be consumed in warmer weather conditions(Reference Stelmach-Mardas, Kleiser and Uzhova35). We used world climatic data from U.S. National Centers for Environmental Information and recorded the mean monthly temperature at the nearest land-based station to the capital city (most often an international airport) and with available data from 2001 to 2018 (Additional file 3). Mean temperature at data collection time was relatively similar across matched countries, except between Hungary and Poland (colder temperature in Poland, the comparison country).

Statistical analyses

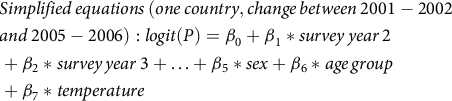

For all analyses, we used STATA® version 15, and statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0·05. We applied multilevel logistic models with random intercept. Level 1 was set for the pupil and level 2 for the class (mean cluster size: 18 pupils/class, no information on clustering in Germany for 2001–2002). All analyses were at the country level and adjusted for sex, age group and temperature at the time of data collection. Changes in proportions of daily, weekly and occasional soda consumers were investigated independently (each coded 0/1) to investigate how these three types of consumption evolved with and without the soda tax separately. In each country with a soda tax, we first tested whether there was a change in the prevalence of daily, weekly and occasional soda consumption between the last measure before and the first measure after the tax implementation, hence focusing on short-term changes. The pre-tax survey year (independent variable) was coded as the reference survey year in the models:

\begin{align}&

Simplified{\mkern 1mu} \, equations\,{\mkern 1mu} (one{\mkern 1mu} \,country,change\,{\mkern 1mu} between{\mkern 1mu} \,2001 - 2002\\

&{\rm{ }}and{\mkern 1mu} \,2005 - 2006):logit\left( P \right) = {\beta _0} + {\beta _1}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 2\\

&\, + {\beta _2}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 3 + \ldots + {\beta _5}*sex + {\beta _6}*age{\mkern 1mu} \, group{\rm{ }}\\

&\, + {\beta _7}*temperature\end{align}

\begin{align}&

Simplified{\mkern 1mu} \, equations\,{\mkern 1mu} (one{\mkern 1mu} \,country,change\,{\mkern 1mu} between{\mkern 1mu} \,2001 - 2002\\

&{\rm{ }}and{\mkern 1mu} \,2005 - 2006):logit\left( P \right) = {\beta _0} + {\beta _1}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 2\\

&\, + {\beta _2}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 3 + \ldots + {\beta _5}*sex + {\beta _6}*age{\mkern 1mu} \, group{\rm{ }}\\

&\, + {\beta _7}*temperature\end{align}

Second, we tested whether this change was larger, smaller or similar to that in the comparison country. Therefore, we analysed data of both matched countries, added the country as a new covariate and applied an interaction term between survey year and country(Reference Knol, van der Tweel and Grobbee36):

\begin{align}&

Simplified\,{\mkern 1mu} equations\,{\mkern 1mu} (larger,similar,or{\mkern 1mu} smaller{\mkern 1mu} \, change{\mkern 1mu} \, from\\

& 2001 - 2002 \,{\mkern 1mu} to{\mkern 1mu} \,2005 - 2006\,{\mkern 1mu} between\,{\mkern 1mu} two\,{\mkern 1mu} countries):logit\left( P \right)\\

&\, = {\beta _0} + {\beta _1}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 2 + {\beta _2}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 3\\

&\, + \ldots + {\beta _5}*country + {\beta _6}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 2*country\\

&\, + {\beta _7}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 3*country + \ldots + {\beta _{10}}*sex\\

&\, + {\beta _{11}}*age{\mkern 1mu} group + {\beta _{12}}*temperature\end{align}

\begin{align}&

Simplified\,{\mkern 1mu} equations\,{\mkern 1mu} (larger,similar,or{\mkern 1mu} smaller{\mkern 1mu} \, change{\mkern 1mu} \, from\\

& 2001 - 2002 \,{\mkern 1mu} to{\mkern 1mu} \,2005 - 2006\,{\mkern 1mu} between\,{\mkern 1mu} two\,{\mkern 1mu} countries):logit\left( P \right)\\

&\, = {\beta _0} + {\beta _1}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 2 + {\beta _2}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 3\\

&\, + \ldots + {\beta _5}*country + {\beta _6}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 2*country\\

&\, + {\beta _7}*survey{\mkern 1mu} \, year{\mkern 1mu} 3*country + \ldots + {\beta _{10}}*sex\\

&\, + {\beta _{11}}*age{\mkern 1mu} group + {\beta _{12}}*temperature\end{align}

We assessed the coefficient sign and P value of this interaction for the period of interest (last pre-tax v. first post-tax survey year). We then computed (-margins- STATA command) and plotted prevalence (95 % CI) of daily, weekly and occasional soda consumption by country and survey year for each pair of countries.

Complementary analyses

Because Finland, Hungary and France had two time points before and after the tax implementation, we modelled pre- and post-tax time trends (slopes) in daily, weekly and occasional soda consumption. Thus, we could estimate whether there was a change in consumption trend in the longer term after the tax. For that, we set the survey year (2001–2002 to 2017–2018) as a continuous time variable, scaled 1 to 5 (survey year 2001–2002 coded as 1, 2005–2006 as 2, etc.) and applied two-piecewise linear spline multilevel logistic models (-mkspline-). We used one knot at the year 2009–2010 (time = 3), composing thus two periods of analyses: the pre-tax (2001–2002 – 2009–2010) and the post-tax (2009–2010 – 2017–2018) periods. To assess whether the trend (slope) in both pre-tax and post-tax periods was larger, smaller or similar to the trend in the comparison country, we again added data from the comparison country (country becoming a covariate) and applied two interaction terms in the models: (1) between pre-tax time and country and (2) between post-tax time and country. We then assessed the sign and P value of the coefficient for interaction terms in both periods (pre- and post-tax).

Results

After excluding 11-year-olds and those with missing data on soda consumption (0·6 % of the remaining sample, Additional file 4), 236 623 HBSC participants (51·0 % of girls) were included in this study. Table 2 shows their characteristics by country. Age and sex distributions were relatively similar across matched countries. Additional file 5 presents similar characteristics for each of the five survey years by country.

Table 2 Description of survey participants, by country (T = with a soda tax, C = comparison, without such a tax)

Latvia (comparison country: Lithuania)

The Latvian tax was introduced in 2004 (€0·03/l) and updated in 2016 (€0·07/l, Table 1). A decline in the prevalence of daily soda consumption (≥1x/d) was observed between survey years 2001–2002 and 2005–2006 (−6·0 % points, −33·6 %, see Fig. 1; P = 0·006, see Table 3), but not between 2013–2014 and 2017–2018 (P = 0·42). The decline between 2001–2002 and 2005–2006 was larger than in Lithuania (P interaction < 0·001), where a rise in daily soda consumers was observed during this period. The prevalence of occasional soda consumption (<1x/week) did not change neither between 2001–2002 and 2005–2006 (P = 0·93) nor between 2013–2014 and 2017–2018 (P = 0·25, Table 3).

Fig. 1 Prevalence of daily, weekly and occasional consumption of soda. Prevalences (95 % CI) are presented by survey year in country that introduced/updated a tax (in orange, plain line) and in the comparison country (in blue or violet, dashed line). Grey bars represent the date of the tax introduction/update. The arrows above the grey bar indicate that the country with a tax had a significant reduction (↓, P < 0·05), a stagnation (→, P > 0·05) or a significant increase (↑, P < 0·05) in the prevalence of daily, weekly and occasional consumers between just before and after the tax introduction. The signs after the arrow indicate whether this short-term change was significantly larger (+, P < 0·05), similar (=, P > 0·05) or significantly smaller (−, P < 0·05) than in the comparison country. Green colour indicates favourable changes in terms of public health (e.g. post-tax decline in daily consumers that was larger than that in the comparison country) (more details in Table 3). G: Germany; I: Italy

Table 3 Changes*,‡ in the prevalence of daily, weekly and occasional soda consumption between the last measure before the tax implementation and the first measure after the tax implementation, compared with the comparison country (interaction between both countries†)

* β were modelled using multilevel logistic models (dependent variable: daily, weekly and occasional consumption: 0/1, independent variable: survey years), adjusted for sex, age group and temperature at the time of data collection). β < 0 (negative) = reduction in daily, weekly and occasional soda consumption between pre-tax and post-tax surveys; β > 0 (positive) = increase in daily, weekly and occasional soda consumption.

† β of the interactions (survey years*country) were modelled using multilevel logistic models (dependent variable: daily, weekly and occasional consumption: 0/1), adjusted for survey years, country, sex, age group, temperature at the time of data collection). β for the interaction < 0 (negative) = more reduction or less increase in the country with the tax compared with the comparison country, β for interactions > 0 (positive) = more increase or less reduction in the country with the tax compared with the comparison country.

‡ β are in bold when P < 0·05.

Finland (comparison country: Sweden)

Finland updated its tax in several stages between 2011 and 2014 (Table 1). After January 2014, soda was taxed at €0·22/l (>5 g of sugars/100 ml) and €0·11/l (<5 g/100 ml). A decline in daily soda consumption was observed between 2009–2010 and 2013–2014 (data collected in Spring 2014, −1·7 % points, −41·5 %, P = 0·001). Yet, this decline was similar to the one observed in Sweden at the same period (P interaction = 0·29). In Finland, no significant change in weekly (1–6x/week) and occasional soda consumption was observed between 2009–2010 and 2013–2014 (P = 0·84, P = 0·17, respectively, Table 3).

Hungary (comparison country: Poland)

The Hungarian tax was introduced in 2011, with an update in 2012 (€0·02/l). We documented no change in daily soda consumers (P = 0·47) and a decrease in occasional consumers between 2009–2010 and 2013–2014 (–3·6 % points, –12·8 %, P = 0·02, Fig. 1 and Table 3). By contrast, we observed, during this period, changes more favourable to health among Polish adolescents, who were not exposed to a soda tax (e.g. a decrease in daily soda consumption).

France (comparison countries: Germany and Italy)

In France, a tax of €0·07/l was introduced in 2012 (Table 1). Between 2009–2010 and 2013–2014, the prevalence of daily, weekly and occasional soda consumption of soda did not change neither in France (P ≥ 0·27, Table 3) nor in Germany (P interaction ≥ 0·25, Table 3), one of the two comparison countries. Compared with France, Italy experienced a decline in daily soda consumption between 2009–2010 and 2013–2014 (P interaction = 0·01).

Belgium (comparison country: Netherlands)

Belgium updated its tax in 2016 and 2018 (€0·12/l after 2018, Table 1). Figure 1 and Table 3 indicate that Belgium had a reduction in the prevalence of daily soda consumption between 2013–2014 and 2017–2018 (−7·3 % points, −20·8 %, P < 0·001), which was smaller than the one observed in the Netherlands during that period (P interaction = 0·03). The proportion of occasional soda consumers remains stable over the period of interest, although we observed a tendency to increase (P = 0·06). This trend was, however, of a smaller extent than the rise in occasional soda consumption observed in the Netherlands between 2013–2014 and 2017–2018 (P interaction < 0·001).

Portugal (comparison country: Spain)

In January 2017, a tax on SSB was introduced in Portugal: €0·16/l (>8 g of sugars/100 ml) and €0·08 (<8 g/100 ml) (Table 1). Similar pre-tax patterns in daily, weekly and occasional consumption were found in Portugal and Spain. After the tax introduction in Portugal, daily soda consumption decreased (−2·5 % points, −14·3 %, P = 0·02), but this decrease was smaller than in Spain at the same period (P interaction = 0·008). In Portugal, weekly soda consumption dropped in 2017–2018 (−7·5 % points, −14·0 %, Fig. 1; P < 0·001, Table 3), which was not the case in Spain (P interaction < 0·001). Finally, the prevalence of occasional soda consumers increased between 2013–2014 and 2017–2018 (+10·0 % points, +36·3 %, P < 0·001), similarly as in Spain (P interaction = 0·15).

Pre-tax and post-tax trends in Finland, Hungary and France

In Finland, we found no long-term reduction in daily soda consumers between 2009–2010 and 2017–2018 (tax implemented between 2011 and 2014, post-tax trend: β = –0·07, 95 % CI (–0·28, 0·14), Additional files 6 and 7). However, there was a declining trend before the tax was updated (2001–2002 to 2009–2010, P < 0·001). The tax was not associated with a long-term downward trend in daily soda consumers. The trend in occasional consumers did not change after the tax update in Finland (P = 0·19), whereas occasional consumers increased in Sweden during this period (P < 0·001). Hungary experienced a long-term decline in daily consumers after tax introduction (β = –0·20, 95 % CI (–0·38, –0·02)), but this decline was smaller than in Poland (P interaction = 0·001). France had a long-term reduction in daily consumers of soda in the post-tax period (β = –0·16, 95 % CI (–0·22, –0·10), Additional files 6 and 7), while no change was documented in the pre-tax period (β = 0·01, 95 % CI (–0·06, 0·07)). The French post-tax trend in daily soda consumption was, however, similar to the German one (P interaction = 0·44), and the reduction was less marked than that observed in Italy (P interaction < 0·001).

Discussion

Prevalence of adolescent daily consumption of sugar-sweetened soda reduced in 4/6 countries in the survey year following the tax introduction or update, corresponding to a few months to 2 years post-tax. Exceptions were Hungary and France, where declines in daily consumption were observed only in the longer term (6 years post-tax). Declines were, however, not larger than those documented in the comparison countries in 3/4 countries (Finland, Belgium and Portugal). In Latvia, the decline in daily consumption was larger than that observed in Lithuania only after the tax introduction. Prevalence of weekly consumption remained stable or increased, except in Portugal, which experienced a net decline. Finally, prevalence of occasional soda consumption did not rise in 5/6 countries, or the rise was similar to the comparison country (Portugal).

Changes in sugar-sweetened beverage sales/purchases in the studied countries

Worldwide, several studies have found that SSB taxation was associated with a decline in sales or purchases(Reference Teng, Jones and Mizdrak16), including in Finland(Reference Jysmä, Kosonen and Savolainen28,37) and Portugal(Reference Goiana-da-Silva, Cruz and Gregorio38). We also found that both countries experienced a decline in adolescent soda consumption in the survey year shortly after the tax implementation. In France, post-tax reduction in SSB sales/purchases was estimated to be limited(Reference Capacci, Allais and Bonnet39,Reference Kurz and Konig40) : about −0·5 l/year/capita 1 year post-tax, compared with Italian comparison regions(Reference Capacci, Allais and Bonnet39). Thus, although not directly comparable to ours, econometric results seem in line with our findings not showing a net short-term decline in daily or weekly soda consumption in French adolescents. Associating the longer term reduction in daily soda consumption and rise in occasional consumers to the tax is difficult. Indeed, other public health nutrition measures between 2009–2010 and 2017–2018 have been implemented in France, such as mandatory dietary standards for school meals, encouraging water provision, in 2011–2012 and the Nutri-score in 2016–2017, a voluntary front-of-pack nutrition label(8). In Hungary, other authors established that SSB sales declined in the years immediately after the tax came into effect(37,Reference Kurz and Konig40) but caught up 2 years later (in 2014)(Reference Kurz and Konig40). Similarly, our findings showed no change neither in daily nor weekly soda consumers between 2009–2010 and 2013–2014. However, in the absence of a tax, the prevalence of daily soda consumption might have increased. Regarding the last two studied countries (Latvia and Belgium), we did not find studies assessing changes in SSB sales or purchases, limiting comparison with our findings.

Changes in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in other countries

While self-reported data on individual-level soda consumption are more prone to declaration bias than sales/purchase data, they provide valuable information on behaviours within households and have the advantage of considering cross-border shopping. Studies using individual-level self-reported consumption data were conducted in Mexico(Reference Sanchez-Romero, Canto-Osorio and Gonzalez-Morales21), three U.S. cities (Berkeley(Reference Silver, Ng and Ryan-Ibarra17,Reference Falbe, Thompson and Becker18,Reference Lee, Falbe and Schillinger20) , Philadelphia(Reference Zhong, Auchincloss and Lee19,Reference Cawley, Frisvold and Hill24,Reference Bleich, Dunn and Soto26) and Oakland(Reference Cawley, Frisvold and Hill23)) and a Spanish city(Reference Royo-Bordonada, Fernandez-Escobar and Simon22). In these jurisdictions, reductions in the consumption of SSB, especially soda, were often observed in adults after tax introduction(Reference Silver, Ng and Ryan-Ibarra17–Reference Zhong, Auchincloss and Lee19,Reference Sanchez-Romero, Canto-Osorio and Gonzalez-Morales21,Reference Royo-Bordonada, Fernandez-Escobar and Simon22,Reference Cawley, Frisvold and Hill24,Reference Bleich, Dunn and Soto26) . The few studies including adolescents found less beneficial changes in SSB consumption. In Philadelphia and Oakland (tax rate > 20 %), children aged 2 to 17 years did not reduce their consumption of soda, or any SSB subcategory, 1 year post tax (small-scale longitudinal household survey data)(Reference Cawley, Frisvold and Hill23,Reference Cawley, Frisvold and Hill24) . Why children and adolescents might be less responsive to soda taxes than adults is unclear. Their food choices might be more influenced by food taste and peer pressure than price and healthiness(Reference Monalisa, Frongillo and Blake12,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry13) . Further studies are also needed to better understand if changes for cheaper soda brands or places of purchase occur(Reference Sturm, Powell and Chriqui41) and if soda companies adapt their sales and marketing practices in the context of tax implementation(Reference Claudy, Doyle and Marriott42).

Different taxes, different jurisdictions and different comparison countries

As noted earlier, tax size/rate plays a crucial role in the reduction of SSB purchase/consumption(Reference Powell, Chriqui and Khan15,Reference Teng, Jones and Mizdrak16) . In the US, tax rates lower than 5 % were considered unlikely to affect childhood SSB consumption at the population level(Reference Sturm, Powell and Chriqui41). Low taxes in Hungary (€0·02/l, rate: 5 %) and France (€0·07/l, rate: 7–10 %)(Reference Teng, Jones and Mizdrak16) could explain why they were not followed by a decline in adolescent soda consumption. In addition, tax effects might reduce over time as we found in Finland and as previously shown in Hungary(Reference Kurz and Konig40). In Berkeley too, reduction in mean consumption frequency seemed to have stagnated 2 years post tax(Reference Lee, Falbe and Schillinger20). Another important point is the pre-tax level of soda consumption. In Berkeley, pre-tax consumption was high (mean consumption frequency: 1·25x/d)(Reference Lee, Falbe and Schillinger20). By contrast, a large reduction in daily SSB consumers was seen among Mexican health workers, whose pre-tax prevalence was relatively low (13 %)(Reference Sanchez-Romero, Canto-Osorio and Gonzalez-Morales21). In our study, reductions in daily soda consumption were also seen in countries with low pre-tax levels (Finland: 4 %, Latvia: 18 %). Thus, taxing SSB may be worthwhile even when daily SSB consumption is low, but further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Public health implications

Larger taxes on SSB (>20 %) might be one solution to reduce adolescent SSB consumption(Reference Teng, Jones and Mizdrak16), which remains elevated in several European countries(Reference Inchley, Currie and Budisavljevic3). Introducing a tax based on sugar content (larger tax for SSB higher in sugar) might also help decrease sugar intake, especially by encouraging SSB manufacturers to reduce the sugar content of their products(Reference Pell, Mytton and Penney43). Tax introduction or updates are also an opportunity to effectively communicate the detrimental effects of SSB on health(9,Reference Alvarado, Penney and Unwin44) or raise revenues to fund public health or social programmes(Reference Allcott, Lockwood and Taubinsky45). Large taxes on SSB should also come with subsidies for healthy foods to limit tax financial regressivity on low-income households(Reference Backholer, Sarink and Beauchamp46).

Moreover, slight differences found in adolescent soda consumption patterns between countries, with and without a soda tax, illustrate that dietary behaviour changes are complex, and taxation is only one of a range of possible public health instruments. The WHO highlights the importance of implementing comprehensive policies and programmes(7). As young people spend a large part of the day at school, restricting physical access to SSB in school premises (e.g. ban on vending machines, standards for healthy school meals) is, for instance, an effective measure to reduce SSB intake(Reference Micha, Karageorgou and Bakogianni47). School food policies, nutrition education programmes and other population-based interventions, such as media campaigns and traffic-light-labelling, could have together partly contributed to the overall downward trend in SSB consumption observed in Europe since 2000–2010s(Reference Bleich, Vercammen and Koma1,Reference Singh, Micha and Khatibzadeh10,Reference Chatelan, Lebacq and Rouche48) .

Strengths and limitations

An important limitation of this study is the observational design and the uncontrolled environment. Indeed, public health interventions, as well as social and economic events (e.g. media campaigns, financial crises, inflation) possibly impacting diet and soda prices, have occurred during the periods under scrutiny. Their complex interplays prevented us from controlling for them. While selecting countries, we did our best to: (1) inventory major national public health interventions that might have impacted soda consumption in the thirteen studied countries(8,Reference Lloyd-Williams, Bromley and Orton49,50) and (2) select comparison countries without such interventions, especially during the period under scrutiny. Still, several national and local policies were implemented; for example, a tax on SSB was introduced in Catalonia, a province of Spain, in March 2017; yet the country of Spain served as a comparison for Portugal. In addition, the absence of fully parallel pre-tax soda consumption trend highlights how comparison results should be interpreted with caution. For instance, it is possible that comparison countries did not introduce a soda tax because they already experienced a favourable decreasing trend in soda consumption (e.g. Netherlands and Sweden) or focused on other policies, such as decentralised/targeted programmes we could not find in the international literature(8,Reference Lloyd-Williams, Bromley and Orton49,50) . Including several comparison countries would have been of interest but was impracticable due to the limited number of similar countries neighbouring the country with a soda tax within the HBSC network. Despite large sample sizes, our study was underpowered to detect small changes when prevalence was high. For instance, a sample size of 3000 in pre- and post-tax survey years could not detect a change of less than ±3 % when prevalence was 50 % (power 80 %; α at 0·05).

HBSC self-reported dietary data also lead to limitations in the interpretation of our findings. Our methodology based on consumption frequency was not precise enough to detect small changes. Additionally, no information was captured on: (1) soda brands; (2) consumed quantities (in ml/d); and (3) consumption of other SSB or other beverages. Thus, we could not estimate the potentially associated reduction in sugar intake expected with sugar content-based taxes, like in Finland and Portugal. We could not assess possible substitution effects either. Following taxation, soda substitution towards 100 % fruit juices (untaxed in 6/6 countries, Table 1) and artificially sweetened beverages (taxed in 5/6 countries, but at lower rate in 2/5 countries) was likely. While substitution towards water(Reference Falbe, Thompson and Becker18,Reference Zhong, Auchincloss and Lee19) would be beneficial in terms of obesity prevention, substituting sodas with other sugary drinks(Reference Bleich, Vercammen and Koma1,Reference Jysmä, Kosonen and Savolainen28,Reference Alvarado, Penney and Unwin44) would produce little health benefits.

Underreporting of unhealthy foods in FFQ is a well-known bias in nutritional epidemiology. The media attention around a tax might have created a ‘signalling effect’, which, in turn, could exacerbate the risk of underreporting soda consumption. This could have overestimated the favourable effect of taxation to health. Furthermore, school-level response rates declined over time (e.g. Portugal between 2013–2014 (97 %) and 2017–2018 (51 %)). Supposing that schools already involved in health promotion actions were more likely to accept participating in HBSC surveys, there was a risk of overrepresenting pupils from the most favoured schools in the more recent samples. This could have overestimated the reductions in daily soft drink consumers, for instance, in Portugal compared with Spain (Spanish response rates: 59 % in 2013–2014 v. 69 % in 2017–2018). A last limitation is the variations in the data collection month(s) across survey years and/or countries. We partly accounted for this issue in adjusting for the mean temperature at the month and year of data collection in the capital city. However, this does not allow fine granulation, especially in climatically diverse countries, such as France.

The present study has also several strengths. First, data came from nationally representative samples drawn from procedures optimised to the country background. Second, the protocol was standardised across survey years and countries, allowing the analysis of 16-year trends in soda consumption with five time points and with comparison countries. Third, the inclusion of six European countries contributes to better understand tax effects in various situations: e.g. small v. large tax size/rate; short v. long period after tax implementation; low v. high pre-tax level of soda consumption. Finally, we also modelled ordered logistic regressions (daily = 2, weekly = 1, occasional = 0, −meologit-) to test whether shifts from daily to weekly and from weekly to occasional occurred, and our findings were confirmed (analyses not shown).

Conclusions

Overall, no country experienced large beneficial changes in post-tax adolescent consumption frequency of soda, when compared with similar neighbouring countries. However, many factors other than taxes drive the changes in sugar-sweetened soda consumption, in comparison countries too. Continued monitoring of the intake of SSB and possible substitution beverages, especially by socio-economic status, is needed to better understand the effects of soda taxes among adolescents. Long-term trend analyses are also important to evaluate whether tax effects plateau after several years of introduction. In this context, information on the intake of SSB (by subcategory) and potential substitution beverages is needed in Europe. In the meantime, comprehensive nutrition policies and programmes, complementary to taxes on SSB, should be continuously implemented, or reinforced, to improve European adolescents’ diet.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: HBSC is an international study carried out in collaboration with World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. The International Coordinator was Jo Inchley (University of Glasgow, United Kingdom) for the 2017/18 survey and Candace Currie (Glasgow Caledonian University, United Kingdom) for the 2001/02 to 2013/14 surveys. The Data Bank Manager was Professor Oddrun Samdal (University of Bergen, Norway). The following principal investigators collected the survey data included in this study: Flemish Belgium (Maxim Dierckens, Bart De Clercq, Carine Vereecken, Anne Hublet and Lea Maes), French-speaking Belgium (Katia Castetbon, Isabelle Godin and Danielle Piette), Finland (Jorma Tynjälä), France (Emmanuelle Godeau), Germany (Matthias Richter, Petra Kolip, Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer and Klaus Hurrelmann), Hungary (Ágnes Németh and Anna Aszmann), Italy (Franco Cavallo and Alessio Vieno), Latvia (Iveta Pudule), Lithuania (Kastytis Šmigelskas and Apolinaras Zaborskis), the Netherlands (Gonneke Stevens, Saskia van Dorsselaer, Wilma Vollebergh and Tom de Bogt), Portugal (Margarida Gaspar de Matos), Spain (Carmen Moreno), Sweden (Petra Löfstedt, Lilly Augustine and Ulla Marklund), Poland (Joanna Mazur, Agnieszka Malkowska-Szkutnik and Barbara Woynarowska). For details, see http://www.hbsc.org. Financial support: HBSC is an international survey carried out in collaboration with the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Data collection is funded at the national level for each HBSC survey. The work related to this article was possible thanks to the academic support of the Université libre de Bruxelles, Belgium and the financial support of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland (UNIL/CHUV mobility fellowship). The funders had no role in the analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. Authorship: A.C. designed the study, processed and analysed the data and wrote and finalised the manuscript. M.R., A.D., A.S.F., C.K. and L.D. participated in the literature search. A.D., A.S.F., C.K. and K.C. collected data with other HBSC team members. K.C. designed the study, supervised the analysis and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no other persons meeting the requirements have been omitted. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical authorisations (respectively exemptions) from the institutional ethics committees or the relevant boards were obtained at the country level before data collection. Information regarding ethical issues is listed for the thirteen countries in Additional file 8. No direct identifiable information about study participants (e.g. names, addresses) was collected. The surveyed schools, adolescents and their caregivers received detailed information about the study and were assured of their anonymity and the possibility to refuse their participation. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.

Conflicts of interest:

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form and declare no conflicts of interests.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980022002361