INTRODUCTION

The increasing global movement of migrants due to changing sociopolitical and economic landscapes in recent years has urged for empirical investigation into the knowledge boundary-spanning strategies of global migrants (Hajro, Reference Hajro2017; Hajro, Zilinskaite, & Stahl, Reference Hajro, Zilinskaite and Stahl2017). Supported by developments in information and communication technologies and empowered by a progressively global economy, knowledge boundary spanning has increasingly become the driving force behind interfirm cooperation (Hinds, Liu, & Lyon, Reference Hinds, Liu and Lyon2011). Knowledge boundary spanning is characterized by the synergistic grouping of varied expertise and interests of individuals separated by cultural and institutional frontiers (Hardy, Lawrence, & Grant, Reference Hardy, Lawrence and Grant2005; Levina & Vaast, Reference Levina, Vaast, Langan-Fox and Cooper2013; Schotter & Beamish, Reference Schotter and Beamish2011; Tippmann, Scott, & Parker, Reference Tippmann, Scott and Parker2017).

Yet, knowledge boundary spanning remains a complex process as actors across boundaries may differ significantly in social identity (Cramton & Hinds, Reference Cramton and Hinds2014; Hinds, Neeley, & Cramton, Reference Hinds, Neeley and Cramton2014; Hong, Reference Hong2010; Levina & Vaast, Reference Levina and Vaast2008; Schotter & Beamish, Reference Schotter and Beamish2011). The ability to align social identity differences forms the basis of one's knowledge boundary-spanning competence (Schotter, Mudambi, Doz, & Gaur, Reference Schotter, Mudambi, Doz and Gaur2017). Competent boundary spanners have sound social identity consideration, which helps them to facilitate and coordinate knowledge sharing while diminishing the likelihood of conflicts (Kane & Levina, Reference Kane and Levina2017; Patriotta, Castellano, & Wright, Reference Patriotta, Castellano and Wright2013; Prashantham, Kumar, & Bhattacharyya, Reference Prashantham, Kumar and Bhattacharyya2019; Schotter et al., Reference Schotter, Mudambi, Doz and Gaur2017). Nascent literature suggests that knowledge boundary spanners have increased chances of achieving knowledge exchange because of the social identity work competencies they have (Brannen & Thomas, Reference Brannen and Thomas2010; Hong & Doz, Reference Hong and Doz2013). Nevertheless, the literature lacks an in-depth empirical account of how identity differences are overcome and how identity work competencies are unfolded for realizing knowledge boundary spanning. To date, little is known about the process of how complex knowledge boundary spanning is approached, especially from the perspective of agents of lower status, such as migrant entrepreneurs and their identity work tactics in the process. To shed more light on this issue, this article explores the ‘identity work’ that underlies the actors’ boundary-spanning competence. We look at identity work tactics that migrant entrepreneurs engage in to achieve knowledge boundary spanning.

What makes the spanning of knowledge boundaries particularly challenging is the enactment of identities. Hence, introducing ‘identity work’ to the knowledge boundary spanning literature can illuminate both the ‘inward’ cognitive process of identity creation and the ‘outward’ relational process of identity negotiation that leads to the exchange of knowledge (Watson, Reference Watson2008). The concept of identity work refers to how subjects, such as migrant entrepreneurs, form, maintain, reinforce, or change constructions of self in directions or efforts that support particular goals (Alvesson & Billing, Reference Alvesson and Billing2009; Essers, Doorewaard, & Benschops, Reference Essers, Doorewaard and Benschop2013). Identity work can serve as the bridge between knowledge boundaries as it denotes agentic activity arising from self-dynamics that, as Emirbayer and Mische (Reference Emirbayer and Mische1998: 974) state, is ‘the point of origin’ of human agency.

Identity work literature will help us illuminate the strategic relational process that occurs between prospective collaborators. By investigating the interplay between inward and outward aspects of hybrid identity work, this study seeks to advance our understanding of the agentic knowledge boundary-spanning activities of migrant entrepreneurs. In an attempt to advance existing knowledge, we explore the knowledge boundary-spanning behavior of Bulgarian migrant entrepreneurs, seeking knowledge exchange with British businesses on UK grounds. We demonstrate in detail how knowledge exchange is linked closely to identity work tactics through which boundary spanners narrow identity differences. Hence, this research study reveals how migrant entrepreneurs perform identity work by maneuvering strategically between identity dynamics through the use of behavioral tactics.

This study of migrant entrepreneurs illustrates particularly well the personal and social identity challenges of knowledge boundary spanning. We show how migrants reconcile identity tensions while negotiating their access across boundaries to overcome knowledge gaps. Interview data from 63 conducted interviews in total reveal that the exchange between migrant and local entrepreneurs is deeply rooted in cognitive frames and social construction. Thus, we could expose the vivid dynamic interplay between inward cognitive and outward relational aspects of identity work. We identified the tactics that migrant entrepreneurs pursue within their integrative identity work strategy to construct their hybrid identity positions, which in turn, grant them access to knowledge. In this study, we refer to the term tactics as the behavioral level strategies that migrant entrepreneurs adopt in the identity work process (Nutt, Reference Nutt1989). Thus, identity work tactics represent the strategic behavioral activities that studied migrant entrepreneurs undertake in the knowledge boundary-spanning process.

This study presents a process-oriented model that sheds light on migrants’ integrative identity work to illuminate the mutually constitutive relationship between ‘inward’ (as characterized by (a) self-identification tactics; (c) mobilization tactics; and (e) reconfiguration tactics) and ‘outward’ identity work (as characterized by (b) social tactics; (d) validation tactics; and (f) specialization tactics). The model illustrates how hybrid identity work is intertwined with knowledge boundary spanning. The findings advance our knowledge of migrant entrepreneurs’ identity work dynamics and identity work as an agentic activity. In addition to revealing the identity processes underlying boundary spanning, this study suggests that ‘identifying identity differences’, ‘adopting identity cues’, and ‘realizing hybrid identity’ all result from the interplay of ‘inward’ and ‘outward’ identity work.

By offering a more process-oriented model (see Figure 1) that depicts migrant entrepreneurs’ efforts to reconfigure their identity (i.e., develop hybrid identity) via identity tactics, our study contributes to recent calls for examining migrant entrepreneurs’ identity work in the processes such as acculturation and identification with their host and home cultures (Dheers, Reference Dheer2018). Specifically, we respond to this less-examined issue and call for further study in the migrant entrepreneurship literature by unveiling behavioral strategies and practices (tactics), which migrant entrepreneurs from transition economies use in the new cultural settings to span knowledge boundaries and initiate interfirm cooperation in new business contexts (e.g., Hajro, Zikis, Caprar, & Stahl, Reference Hajro, Caprar, Zikic and Stahl2021).

Figure 1. The process of hybrid identity development via identity work tactics

RELEVANT CONCEPTS AND FRAMEWORKS

How newcomers from culturally diverse backgrounds span knowledge boundaries is an important question, demanding careful examination of the actions for lowering the perceived risks of exchanging knowledge with a new actor (Dore, Reference Dore1983; Powell, Reference Powell1990). It is likely that if foreign actors manage to project reliability and identity fit, then knowledge exchange can be initiated. Identity and belonging are commonly seen as elements of the relational dimension of social capital (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998). Other dimensions of social capital are structural and cognitive ones. Researchers have built up this understanding from Granovetter's (Reference Granovetter1992) discussion of structural and relational embeddedness, which is another reason why identity and social capital go hand in hand, yet they highlight a different part of migrant entrepreneurs’ journey to embeddedness in the host-country social and business environments. In the case of migrant entrepreneurs, conducting identity work is what enables the social capital to be developed in the host-country environment. This is because a shared identity has a range of positive implications for relationship building (You, Zhou, Zhou, Jia, & Wang, Reference You, Zhou, Zhou, Jia and Wang2021).

Identity Work: The Interplay Between ‘Inward’ and ‘Outward’

Identity work involves new actors adjusting their sociocultural understanding and identity to establish a better organizational fit between their cultural and social background and that of desired collaborators (Kane & Levina, Reference Kane and Levina2017). The identity work notion highlights ‘the experience of agency’ (Gecas, Reference Gecas1986: 140) and allows studying how micro-processes can impact macro-outcomes (e.g., knowledge boundary spanning) (Brown, Reference Brown2017). Identity work is defined as ‘the range of activities individuals engage in to create, present, and sustain personal identities that are congruent with and supportive of the self-concept’ (Snow & Anderson, Reference Snow and Anderson1987: 1348). Identity work actors are ‘people […] engaged in forming, repairing, maintaining, strengthening or revising the constructions that are productive of a sense of coherence and distinctiveness’ (Sveningsson & Alvesson, Reference Sveningsson and Alvesson2003: 1165). Identity work literature suggests the existence of internal (i.e., ‘inward’) and external (i.e., ‘outward’) characteristics of identity work. This is most clearly seen in Watson's (Reference Watson2008: 129) argument that ‘identity work involves the mutually constitutive processes whereby people strive to shape a relatively coherent and distinctive notion of personal self-identity and struggle to come to terms with and, within limits, to influence the various social identities that pertain to them in the various milieus in which they live their lives’. As a result, ‘inward’ identity work refers to the cognitive processes related to identity preservation or justifying one's identity. ‘Outward’ identity work refers to relating or negotiating one's identity to others via communication or signaling practices. Thus, identity work is a concept that covers one's journey for social validation and holds explanatory power for shedding light on the dynamics of knowledge boundary spanning.

Identity work recognizes the identity-related complexities associated with spanning social domains – for instance, dealing with identity challenges and validating own identity (Ibarra & Barbulescu, Reference Ibarra and Barbulescu2010). Identity validation underlies legitimacy and embeddedness building, key enablers of knowledge boundary spanning. Ashforth and Schinoff (Reference Ashforth and Schinoff2016: 117) advise researchers ‘to be cognizant of the interplay – and potential conflicts – between internally and externally focused identity motives’. Thus, it can be argued that illuminating the process of knowledge boundary spanning requires an awareness of the interplay between inward and outward identity work. As recognized by Brown (Reference Brown2017), inward and outward identity work can be in conflict. This is easy to see in the example of boundary spanning. On the one hand, migrant entrepreneurs want to preserve their original social identity as it gives them access to assets related to their foreignness (Stoyanov, Woodward, & Stoyanova, Reference Stoyanov, Woodward and Stoyanova2018). On the other hand, they want to cooperate with local entrepreneurs, which may motivate them to copy the identity of prospective partners in order to facilitate collaboration. Yet, substituting identities may deprive migrant entrepreneurs of access to the very assets (e.g., gaining knowledge of the foreign migrants’ home market) that UK-native entrepreneurs may be interested in, and which may motivate collaborative partnership. Identity construction is a multifaceted process as one's identity is formed by exposure to multiple groups (Brannen & Thomas, Reference Brannen and Thomas2010) (e.g., ethnicity, gender, social class/socioeconomic status, religious beliefs, professional belonging, educational background, etc.). Hence, identity can never be reproduced in its entirety. Likewise, one cannot construct any identity in full.

For that reason, the interplay between inward and outward identity work needs to account for these dynamics. Currently, it remains unclear how these potentially conflicting dynamics can be balanced. The current study hopes to shed more light on how potentially conflicting dynamics can be balanced by paying attention to migrant entrepreneurs’ interpretive agency in sensemaking and their efforts to shape a dual social context (Emirbayer & Mische, Reference Emirbayer and Mische1998).

Boundary Spanning and Hybrid Identity

Identity work allows us to study migrant entrepreneurs’ identity adjustments within a new social environment. Yet, identity theory suggests that constructed identity is characterized by discursive boundaries between social groups (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska1997). Migrant entrepreneurs need to overcome these discursive boundaries to form cooperation. Thus, migrant entrepreneurs’ identity work can be informed by ‘boundary work’ literature (Gieryn, Reference Gieryn1983). Scholars have already regarded identity work as the ‘boundary work that people do to react to processes of inclusion and exclusion’ (Essers & Benschop, Reference Essers and Benschop2009). Boundary work can help the generation of relational resources, negotiation of identity, and dual legitimacy, which will facilitate development of mutual boundary practices (Gal, Yoo, & Boland, Reference Gal, Yoo and Boland2005: 3). Accordingly, this study utilizes the concept of ‘boundary spanning’ to characterize actors’ efforts to connect and dismantle boundaries.

Experienced disorientation in the host country motivates migrant entrepreneurs to adjust their identity according to host-country norms and expectations (i.e., hybrid identity) to increase chances of engaging in knowledge boundary spanning. Hybrid identity work is characterized by cross-fertilizing diverse identities so that elements of both are adopted in one social space (Marotta, Reference Marotta2008; Puffer, McCarthy, & Satinsky, Reference Puffer, McCarthy and Satinsky2018; Purchase, Ellis, Mallett, & Theingi, Reference Purchase, Ellis, Mallett and Theingi2018). Hybridization represents a recombination process that dilutes domain boundaries, while allowing migrant entrepreneurs to capitalize on their previous identities. Previous experiences and identities can be reconstructed in light of migrant entrepreneurs changing needs (Schultz & Hernes, Reference Schultz and Hernes2013). Reconstructing previous identities to align with the identity of desired groups allows for cognitive boundaries to be blurred and domains to be spanned. Exploring knowledge boundary spanning through hybrid identity work lens illuminates how migrants participate in classification and comparison of sociocultural codes and schemas for establishing their ability to associate themselves to the new business environment and initiate knowledge exchange.

Knowledge Boundaries and Migrant Identity

Knowledge boundaries are a category of social boundary that is deeply rooted in interpretive frames, practices, and status (Carlile, Reference Carlile2004). Knowledge is associated with identity as it provides actors with cognitive resources for sensemaking (Gecas, Reference Gecas1982). Knowledge is also an instrument for regulating relationships between individuals and groups (Wenger, Reference Wenger1998). For actors that work with knowledge resources (i.e., consultants), knowledge content and knowledge articulation are instruments for identity construction (Visscher, Heusinkveld, & O'Mahoney, Reference Visscher, Heusinkveld and O'Mahoney2018).

Spanning knowledge boundaries constitutes a significant challenge for the adjustment of identities (Carlile, Reference Carlile2004). Knowledge boundary spanning demands careful consideration of inward and outward identity processes. Recent studies shed light on the organizational practices for socializing migrant newcomers to the knowledge boundaries of their new workplace (Jokisaari & Nurmi, Reference Jokisaari and Nurmi2009). Yet, there is a scarcity of research insights into the migrant entrepreneurs’ identity work tactics when initiating knowledge exchange with members of alternative knowledge boundaries (Dheers, Reference Dheer2018). Scholars (e.g., Ravasi & Phillips, Reference Ravasi and Nelson2011; Schultz, Maguire, Langley, & Tsoukas, Reference Schultz, Maguire, Langley and Tsoukas2012) have pointed out the importance of understanding individual identity work as a driving force of interfirm partnerships. This article addresses this gap by examining the hybrid identity work tactics that Bulgarian migrant entrepreneurs use for obtaining knowledge-based assets from their local UK counterparts.

METHODS

We base our work on a qualitative, interpretive case-based research design (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989). We explored 12 company cases of Bulgarian entrepreneurial ventures located and operating in London. We selected London as the geographical context of investigation as it is home to 46% of all self-employed foreign-born workers in the country (2011 labor force report, UK Office for National Statistics). Moreover, Bulgarian entrepreneurs working in London number 4537, representing 51.5% of the total of 8798 in the UK (Centre for Entrepreneurs & DueDil, 2014).

The choice of data context is justified by an important sociopolitical, as well as economic, event: Bulgaria's accession to the European Union in 2007. This event has stimulated economic and migratory exchange between two countries of interest – the UK and Bulgaria – forming a new wave of new entrepreneurial collaborations. All of the studied cases and interviewed migrant entrepreneurs are examples of individuals who have developed strong partnerships in the UK.

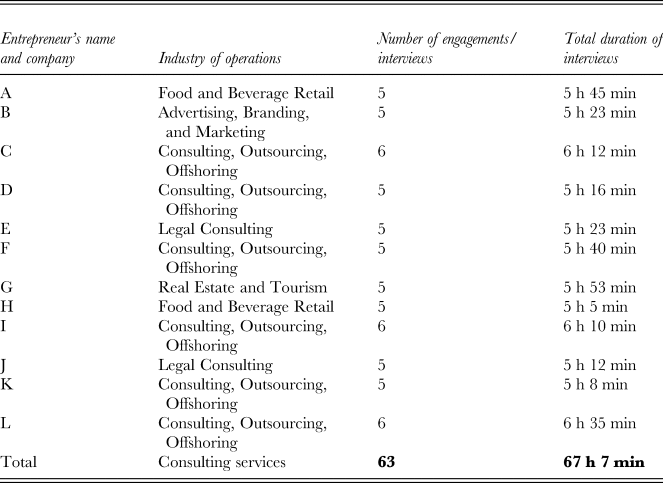

We used non-probability, purposeful sampling, drawing potential subjects for exploration from a list of more than 130 companies operating in the UK, obtained from the Embassy of the Republic of Bulgaria. We approached the entrepreneurial companies through a survey with specific selection criteria. The selection criteria were that companies are founded by migrant entrepreneurs, be considered SMEs, be in the Greater London area, and engage in consulting services. The reason for the decision to focus on consulting service providers was that we are interested in exploring the relational competencies and processes that lead to an exchange of knowledge resources. This allowed us to separate companies whose competitive advantage is based on tangible as opposed to intangible assets, as these would typically follow interfirm cooperation strategies based on their tangible assets (e.g., product innovation). The age of the selected businesses varied between 2 and 10 years, and the number of employees between 5 and 27 people. Of the selected companies, all but two are providers of high value-added services such as general business consulting, procurement, local search engine optimization, outsourcing, and business law consulting (see Table 1). This contrasts with previous research, which tends to explore mainly migrant entrepreneurial activities in low-intensity knowledge sectors. By focusing on high-intensity knowledge sectors, we contribute to the recent call for advancing knowledge on migrant entrepreneurial strategies in knowledge-based and consulting industries.

Table 1. A coded list of business cases

The remaining two are food and beverage retailers included in the research because, along with retailing, they engage in logistics consulting (e.g., securing suppliers or consulting on distribution for customer service improvement). Because of the activity profile of the studied companies, their knowledge intensity is high. To gather data, we used a combination of semi-structured interviews, participant observations and oral/life stories. We conducted 63 semi-structured interviews in total, which were transcribed, coded, and analyzed (see Table 2). The interview structure was designed for a series of 60–90 min semi-structured interviews with the owner/founder of the entrepreneurial entity. In addition, we conducted interviews with at least three employees (all suggested by the owner) in each company case. This provided us with greater insight into the company strategies and dynamics. The interviews were conducted in Bulgarian language where possible, and in English where interviewees were British employees of the company. Interview data is a preferred source of information and data collection methods in research studies exploring identity work dynamics. Most of the collected interview data were retrospective in nature, where interviewees recalled previous experience and behavioral tactics. Retrospective interviews are valuable as they provide an opportunity for in-depth reflection in contrast to relying solely on real-time data where one can miss events or occurrences which could be critical for the research findings (Flick, Reference Flick, Uwe, von Kardorff and Steinke2004; Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2007). In order to avoid retrospective bias associated with the collection of primary interview data and any additional research based on past experiences, collected data was triangulated by interviewing each of the entrepreneurs at least twice to ensure the accuracy in our interpretation (Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven2007).

Table 2. Summary of interviewees, number of interviews, duration, and interview mode

A semi-structured interview (60–90 min) was carried out with each owner (all males). Interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed. Moreover, interviews with at least three employees of each company were conducted (40 interviews in total). The employees (all suggested by the owners) shared insight into the adopted organizational strategies

Analytical Approach

Participant observation was carried out during individual actors’ business meetings, social events arranged by the British Bulgarian Chamber of Commerce, and the Embassy of the Republic of Bulgaria. These observations enabled the researcher to have a better grasp of the entrepreneurs’ social representation strategies. Participant observations achieve the desired balance between ‘doxa and opinion, between practical understandings that are never brought to the level of explicit discussion, and those that are explicitly verbalized and discussed’ (Rudie, Reference Rudie, Hastrup and Hervik2003: 29). For that reason, the method is believed to facilitate recognition of social actors’ consciousness and perceptions.

Participant observations provide an accurate account of entrepreneurs’ identity work phase by taking into consideration the actors’ direct involvement in the social environment, as well as their observable response behavior toward different business-related activities (Goulding, Reference Goulding1998). Moreover, participant observation is a natural complement for the interview data collection approach as it facilitates comprehensive exploration of native customs and the population's thinking patterns, while recording available beliefs of the observed subjects (Stewart, Reference Stewart1998). Specifically, attending social events led to impromptu interviews with independent informants such as professionals (e.g., consul of the Bulgarian Embassy in London), consultants, business owners, and other members of the Bulgarian City Club in London. These interviews were conducted for triangulation purposes.

Attending these events allowed the researcher to observe in real-time how entrepreneurs position themselves and initiate conversations – an important indicator of their collaboration-building strategies. These social events took place in August and September of 2011 and included two monthly meetings of the Bulgarian City Club. This club welcomes business professionals of Bulgarian descent and maintains strong relationships with the Bulgarian Embassy and the Chamber of Commerce.

The full immersion in participant observation is facilitated by the development of an observation framework that serves as a plan that clarifies the structure and nature of what needs to be observed. The employed framework (Appendix II: Observation Framework) includes elements of observational situations that have been identified on the basis of sociological theory and methodology of participant observation (Losada & Manolov, Reference Losada and Manolov2015; Peak, Reference Peak, Festinger and Katz1953). Outlined in the framework, units of observation facilitate the illustration of the actors’ behavioral categories. Interviews and field notes were transcribed and examined via narrative analysis. Word and phrase counts were taken into consideration for coding purposes, which allowed the emergence of constructs that illuminate the research phenomenon.

An in-depth analysis on available data was conducted through the identification of (1) first-order categories, (2) second-order themes, and (3) aggregate dimensions (as shown in Figure 2) – an analytical practice proposed by Corley and Gioia (Reference Corley and Gioia2004) that allows moving from the description of the accounts to theory (see Table 3). Open coding facilitated identifying general nodes of information with the data. It also assisted the classification of properties of information nodes of interest. This approach exposed first-order themes in the data, which were then specified via the axial coding stage to outline an explicit set of phenomena under investigation. The third stage, selective coding, has aided the selection of aggregate dimensions that emerged as fundamental for the present study (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilston, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012). In the final, selective coding, stage, the number of phenomena identified in prior stages is reduced and categories integrated where possible. Data reduction has been carried out by a general semantic analysis.[Footnote 1] This information was used for revealing the central phenomena that stem from the data.

Figure 2. Data structure and reduction Source: Data reduction modeled after Corley and Gioia (Reference Corley and Gioia2004).

Table 3. Representative quotes

RESULTS

Our findings suggest that the identity work through which newcomers manage to establish business partnerships with local UK entrepreneurs in the host country is a complex process realized through a number of tactics through time. In this study, we sought to explore the hybrid identity work that facilitates interfirm cooperation between migrant and British entrepreneurs. In order to shed light on how actors adjust identity differences, we took an identity work approach. We discovered interfirm cooperation to emerge upon the development of the following three phases: Phase 1: Identifying identity differences, Phase 2: Adopting identity cues, and Phase 3: Realizing hybrid identity. Each of these phases captures the boundary-spanning tactics (second-order themes) which the studied migrant entrepreneurs have developed through a range of practices (first-order categories) allowing organizational goals to be achieved and access to resources to be secured (see Figure 2).

First, our findings stress the importance of the organizational context in the identity work process between British and Bulgarian migrant entrepreneurs. In the case of our study, the first interactions between the Bulgarian entrepreneurs and their British counterparts happened during formalized events organized by the British Bulgarian Chamber of Commerce in London. This organizational context provides situational opportunities that can affect the development of partnerships and organizational goals (Johns, Reference Johns2006). Moreover, the organizational context provided a structure, informally legitimizing the intentionality of parties with different identities. Thus, in the case of this study, the organizational context perceived as a legitimate platform for business interaction and reduced the likelihood of homophile dynamics. Yet, the organizational context alone cannot guarantee the development of interfirm cooperation. Our findings showed the tactics that the Bulgarian entrepreneurs used during the identity work process to differ in terms of intensity. Broadly, they can be characterized as weak in the first stage of identifying identity differences, moderate in the second stage, and strong in the third stage of realizing hybrid identity.

Phase 1: Identifying Identity Differences

In this first phase, migrant entrepreneurs were more reluctant to communicate business ideas straightaway with potential foreign partners in order to avoid wrong judgment. Our findings suggest Bulgarian entrepreneurs benefitted from the use of self-identification and social tactics in this phase of identity work. These tactics were rather weak or informal in terms of intensity. Furthermore, our findings showed that migrant entrepreneurs invested considerable time as silent observers, identifying and understanding differences in norms and local behavior as well as sources of normative influences. Our findings also showed that in this phase, migrant entrepreneurs realized the importance of regulating personal behavior in accordance with the host-country business norms. However, most of the interviewees shared that during the first few months (Entrepreneur J) their knowledge about the host-country environment and the business opportunity it offers was relatively fragmented. They found it easier to recognize opportunities but difficult to seize them. In this regard, one of the respondents shared:

Recognizing opportunities was easy. From day one, I saw an opportunity to open a branch in London, but it took time to find out how to sail in foreign waters and how to make friends. In addition, you really need to make friends with the locals if you want to succeed. They know the tiny secrets of the market as they have been here longer. (Entrepreneur J)

The collected data suggest that migrant entrepreneurs acted more as anthropologists who observe and try to study silently local practices and norms by categorizing their self-identity and juxtaposing their cognitive understanding to that of the local entrepreneurs rather than acting as direct participants. Entrepreneur (A) sheds light on the practice of sensing differences in business and social norms. He stated:

What I have learnt from my other endeavors in this business is the danger of wrong suppositions and pre-judgement of others. I think I have become wiser with age and much more patient. It is all a matter of communicating it right. We may have the same ideas, but it is our cultural individuality and embedded behaviors, which can cause misunderstandings sometimes. (Entrepreneur A)

He continues:

What has been my strategy? I try to be reflective before being proactive. I think it is essential to identify my weaknesses in terms of knowledge, networks while finding more about the local approach to things, how they think, how they do business, even how they drink wine (laughing) (pause). Though for the latter, I am sure we have the same understanding but maybe a different taste, so it can be equally important to know (laughing).

Another practice, part of the self-identification tactic which migrant entrepreneurs use, is the identification of sources of normative influences in the host-country's business environment. One of the interviewees (Entrepreneur E) explained how he goes about finding the right sources of information.

Knowledge about the market environment, knowing your competitors, are all important factors contributing to business success. But they are built through time, and through experience, not overnight. In the beginning, if you want to be successful as a foreigner, you need to stay focused and make sure you are communicating with the right people at the right time, with whom possess the right information, with whom knows what the next big trend in the industry will be. (Entrepreneur E)

He shared further:

In the beginning, when I was searching for a business partner with relevant local knowledge, I would attend an event organized by the British Bulgarian Chamber of Commerce but first I would look at the attendees’ list, their names, if there is information about their company or the industry they work in … then first I will observe to whom most people want to talk to … (Entrepreneur E)

The second identified competence, which assisted the initiation stage of building collaboration between Bulgarian entrepreneurs and their British counterparts, is migrants’ social competence. We define this competence as the ability to form new social interactions by regulating personal behavior in accordance with specific cultural and normative expectations. Once we started probing the Bulgarian entrepreneurs on the next steps they take before approaching a relevant British partner, two main tactics became apparent. Both practices assisted in the development of their social competence.

The first refers to the process of communicating former experience and attributes with host-country entrepreneurs. Our respondents shared that they think carefully about the first impression they leave at the beginning of the socialization process. Entrepreneur B stated:

It is important whom you know but in my opinion, it is even more important who knows you and what their first impression of you is. Sometimes your interaction with a potential client or a partner can be as short as five minutes. You need to be vigilant about the main message you like to convey that sticks with them. This is your trademark and how people will remember you. I want to be known as ‘[Name], the reliable guy, who delivers superb, on-time logistics services at a lower price’, not only as the ‘guy with the moustache’. (Entrepreneur B)

Another entrepreneur shared his opinion on the importance of first-time communication with future international collaborators.

Different people have different strategies. For me … I would always make sure that I have my Bulgarian business cards translated into the language of my future foreign partners and competitors. I will make sure that I have the right design, the right color and the right level of clarity as to their business cards. Sometimes it may be the title of my position and how it translates in English. Direct translations may not necessarily make sense in the foreign language so you should be careful. Small cosmetic changes but they are essential for building common ground besides our cultural differences. (Entrepreneur C)

Furthermore, through our data analysis, we found that a contributing factor to the identity work of Bulgarian entrepreneurs is their approach to determining legitimacy barriers.

To gain customer loyalty in the new marketplace is difficult, to do it in a foreign marketplace is even harder especially if you are a small business with limited to no previous market visibility. People do not know your brand and more importantly, they have not experienced it, so why they should trust you? (Entrepreneur C)

He continued stressing the importance of social and business events organized by the BBCC for discovering normative or legal obstacles, which may slow down business success.

Even if you decide to invest to raise brand awareness for example, as a small business you need to be 100% sure you are making the right decisions otherwise you risk failure. To do so, you need adequate knowledge. Events like this one help me to reflect and find out weaknesses in my approach of doing business, legal or business matters which I may not know but also they give you a clue, metaphorically said, about the lands you should not try to conquer. (Entrepreneur C)

In contrast to the first initial stage of cross-boundary spanning when migrant entrepreneurs discovered the normative and social rules of the host-country business milieu, during the second phase, they started to mobilize their knowledge and tried to adopt actively the new normative behavior. We entitled this phase as the adoption of identity cues. Two main identity work tactics appeared to be critical during this phase.

Phase 2: Adopting Identity Cues

Two main boundary-spanning tactics appeared to be critical for identity work during this period. The first one is the mobilization tactic defined by practices gaining access to new information flow and processes of leveraging on previous information flows. Our results suggest that one of the main reasons for some of the Bulgarian entrepreneurs to start communicating and identifying more actively with their British counterparts was dissonance between their perception and that of their fellow nationals. One of the interviewees sheds light on these dynamics:

Once I arrived in the UK, through my interaction with other Bulgarians I found two groups of people among them. One group of people thought they were smarter than the British because as foreigners they have achieved maybe a similar social status if not even higher in the host country. They were lawyers, doctors, teachers … In some cases, these were people coming from a more aristocratic family in Bulgaria, having a higher level of education. The second group, they tended to underestimate themselves and their competences. Depending on which group you communicate to, you will get mixed advice. I soon realize that I did not share these logics. There were some exceptions, especially among the people I met through BBCC, but this was the dominant understanding among my fellow country mates. I thought it is better to find out for myself. So, I thought I need to start building and investing in new friendships. (Entrepreneur D)

Another migrant entrepreneur (L) shared a similar view. He explained the existence of selectivity among the British entrepreneurs who attend cross-cultural business events.

Many of the British business people who are invited to these events are also looking for new capabilities and knowledge through business partnerships. But you can imagine there is a selection process going on and most likely they are inclined to work with a person sharing their own understanding and business inspirations. So when I get the chance to talk to potential partners and clients, first I listen very carefully to what they have to say. In my head, I am trying to absorb new knowledge but also to chart commonalities. (Entrepreneur L)

According to our emergent findings, the second tactic is the validation tactic, characterized by the tendency of the Bulgarian entrepreneurs to prototype normative behaviors, learnt during earlier stages of identity work and later to mimic the organizational practices of their British counterparts.

I am the type of guy who always cross-checks his sources and his information before taking action. So, once I have observed or learnt some potentially viable information, I try to confirm it with other British entrepreneurs. For example, I needed to find a good accountant, someone to take care of the books and all the documentation, so I put myself in Sherlock Holmes’ shoes. (Entrepreneur F)

Entrepreneur (I) explained that he decided to adopt the practice of giving business cards as he noticed that this is a norm among British entrepreneurs. He stated:

Usually if I interact with a Bulgarian businessman, we would just exchange mobile phone numbers or you would write their phone down on the back of a paper, nothing fancy. I noticed there is a more formal procedure of offering your business card among the British, so I made it also my practice. (Entrepreneur I)

In terms of building marketing capability, another respondent (Entrepreneur B) stressed the fact that he found the marketing process through which British and Bulgarian business professionals promote their business to be different. In contrast to the Bulgarian practice to rely mainly on word of mouth communication, especially at the beginning of the venture when the company brand is still not well established, one of the interviewees explained, ‘[t]he British invest a good amount of financial resources in marketing from the very beginning’ (Entrepreneur H).

Phase 3: Realizing Hybrid Identity

If in the first two phases they were learning and mimicking British norms and behaviors, in the last phase of socialization, we noticed that they become much more selective in their approach of embedding themselves in the British entrepreneurial community. We entitled this phase as realizing hybrid identity as here the migrant entrepreneurs started to leverage selectively on the strengths of their Bulgarian identity but also on their identity adopted from interfirm collaborators. The main identity work tactics that define this phase are reconfiguration tactic and specialization tactic.

Enhanced independent thinking, imagination, and tactics of modifying and improving existing capability supported the first tactic. Our findings showed that in the third phase Bulgarian entrepreneurs used the projected impressions that they left in the British entrepreneurial community during the second stage as a competitive advantage for modifying their existing capability base in the third phase. The following quote from one of the interviewees explained these dynamics in the identity work process.

Through my initial communication with local entrepreneurs, I thought I can leverage well on both of our strengths rather than excluding one's previous best practices. Many of my countrymates decide solely to go for the British or the Bulgarian model. I think there is a certain value of knowing when, in what situations to use one or the other. (Entrepreneur B)

He continued stressing the importance of understanding the importance of signaling (i.e., outward identity work).

It is wrong to think that your future host country partners would like you to be the same. To have common ground in the values and modes of operations, yes, but not necessarily in your capability and resource base. In small talks, similarity social, cultural and business norms are crucial but not once you have passed this stage, then you need to differentiate and show how a potential partnership with you can accelerate your counterparty's success. You need to be flexible but also fast.

Another entrepreneur (Entrepreneur A) explained the importance of communicating examples and indirect stories about one's success to intrigue the other parties’ curiosity and to shift the focus of their attention in order to trigger interest for cooperation.

It is always difficult to convince people to adopt new practices especially if they have been doing something that has been working for years, so why they should adopt new approaches or practices to their work? If you tell people directly that they need to be let's say trying a different type of software to run their logistics, for example, chances are people won't be that interested to listen to you and to change their practices. You need to make sure that you help them to imagine and discover the ‘other’ way of operating. They often need to see a successful example. (Entrepreneur A)

DISCUSSION

In the present research, we sought to explore the identity work process of migrant entrepreneurs who want to engage in knowledge boundary spanning with UK entrepreneurs. Previous research has emphasized that participants from diverse knowledge boundaries and culturally different backgrounds tend to possess different social identities, which may influence knowledge boundary spanning (Rink & Ellemers, Reference Rink and Ellemers2007). Identity adjustments emerge during the interaction between individuals from the two knowledge boundaries (Batjargal, Reference Batjargal2007). This article scrutinizes the identity responses of actors who engage in knowledge boundary spanning.

Recent studies (e.g., Kane & Levina, Reference Kane and Levina2017) have suggested that knowledge boundary spanning may be characterized not simply by positively stereotyping in-groups and negatively stereotyping out-groups, but rather by a strategic approach for overcoming identity differences. We took an identity work approach to shed light on the process of negotiating social identity differences (i.e., developing a hybrid identity). Thus, we focused on the individual entrepreneurs’ relational tactics that reveal the ‘inward’ cognitive process of identity creation and ‘outward’ relational process of identity negotiation. By investigating the interplay between the inward and outward tactics of hybrid identity work, we scrutinized the relational journey that migrant entrepreneurs undergo to realize knowledge boundary spanning.

The identified ‘inward’ identity work tactics are (a) self-identification tactics; (c) mobilization tactics; and (e) reconfiguration tactics. The identified ‘outward’ identity work tactics are (b) social tactics; (d) validation tactics; and (f) specialization tactics. Inward and outward tactics coexist in pairs (e.g., (a) and (b); (c) and (d); (e) and (f)), which allows hybrid identity development to occur. Interplay between inward and outward identity work moderates the identity adjustment process – which prevents the over-positively stereotyping of own identity, as well as over-positively stereotyping the identity of members of the alternative knowledge boundary. In that way, no single identity can dominate the hybrid identity development process. This observation is significant for understanding the balancing forces that enable hybrid identity development to take place.

Figure 2 shows the interplay between ‘inward’ and ‘outward’ identity work tactics (see second-order themes), as well as the achieved strategy over the observed three phases (see aggregate dimensions). In addition, Figure 2 also shows the operations (see first-order categories) that allow the migrants to formulate tactics and achieve their overall strategy. The operations migrants carried out illustrate how they mobilize knowledge resources from diverse knowledge boundaries to construct their respective identity positions. While boundary-spanning facilitates access to resources from the two knowledge boundaries, it is ultimately individuals’ identity work that informs how these resources are mobilized in hybrid identity construction.

Zooming into the identity work process through which Bulgarian entrepreneurs engage in knowledge boundary spanning in the UK, we recognize three main phases of hybrid identity development – Phase 1: Identifying identity differences; Phase 2: Adopting identity cues; and Phase 3: Realizing hybrid identity.

Our findings show that the tactics used by Bulgarian entrepreneurs during the hybrid identity development process differ in intensity. Broadly, they can be characterized as weak in the first phase of identifying identity differences, moderate in the second stage, and strong in the third stage. In the first phase, migrant entrepreneurs are reluctant to directly communicate business ideas with potential foreign partners in order to avoid wrong judgment. Thus, their relational tactics are of lower intensity. Instead, migrant entrepreneurs invested considerable time as silent observers, identifying and understanding differences in norms and local behavior as well as sources of normative influences. Endogenous factors such as the personal drive for trusted collaborative partnerships with both local, as well as Bulgarian entrepreneurs, stimulate respondents to remain open-minded for potential opportunities at events and workshops sponsored by the chamber of commerce. Our findings showed also that in this phase migrant entrepreneurs realized the importance of regulating personal behavior in accordance with the host-country business norms. Furthermore, boundary-spanning tactics such as determining potential legitimacy barriers and communicating former experiences and attributes allowed migrant entrepreneurs to identify potential business partners. In contrast to earlier theoretical assumptions, which assume people from diverse cultural backgrounds to have a natural tendency to generalize from their home country experience, our results showed the contrary. Bulgarian entrepreneurs who were able to build trusted partnerships entered the identity work process neutrally. They neither positively stereotyped their in-group identity, nor negatively stereotyped out-group identities. They neither underestimated normative and cultural differences within the in-group nor overemphasized differences with the out-groups.

Our study also contributes to recent calls for research related to the behavioral strategies and practices, which migrant entrepreneurs use in the new cultural settings to span knowledge boundaries and initiate interfirm cooperation in new business contexts (e.g., Hajro et al., Reference Hajro, Caprar, Zikic and Stahl2021). This makes our findings potentially interesting for decision-makers and practitioners whose works relate to immigration work, policy development, or the development of public support systems, which aim to encourage the entrepreneurial activities of migrants.

Implications for Theory

This study contributes to identity work and migrant entrepreneurship literature in several ways. First, unlike previous studies that often take hybrid identity construction as a personal coping apparatus, here we examine how it can facilitate knowledge boundary spanning. We illustrate that identity work can have wider positive implications beyond reconciling conflicting identities. This study advances our understanding of the initiation of interfirm cooperation by showing how identity work tactics influence knowledge boundary spanning in the context of migrant entrepreneurship. Thus, it responds to recent research calls for exploring the identity work dynamics for migrant entrepreneurs in foreign business contexts (Dheers, Reference Dheer2018; Hajro et al., Reference Hajro, Caprar, Zikic and Stahl2021). The process of sensing business and social norms and identifying sources of normative influences enable migrant entrepreneurs to take a comparative position. That comparative position allows them to ultimately realize hybrid identity by sending the right cues to the targeted knowledge boundary.

As a result, this article contributes to an emerging body of work that focuses on the influence of identity work on different social processes and outcomes (Creed, DeJordy, & Lok, Reference Creed, DeJordy and Lok2010; Essers & Benschop, Reference Essers and Benschop2007; Heilbrunn, Gorodzeisky, & Glikman, Reference Heilbrunn, Gorodzeisky and Glikman2016; Lifshitz-Assaf, Reference Lifshitz-Assaf2018; Lok, Reference Lok2010; McGivern, Currie, Ferlie, Fitzgerald, & Waring, Reference McGivern, Currie, Ferlie, Fitzgerald and Waring2015).

Second, this study reveals the intricacies of hybrid identity work and shows that it is underpinned by the ‘inward’ cognitive process of identity creation and the ‘outward’ relational process of identity negotiation. The study shows the behavioral tactics that enable these processes to occur. In addition, we pay attention to the interplay between inward and outward tactics as an enabler of interfirm cooperation and knowledge boundary spanning. Besides, by focusing on the mutually constitutive nature of inward and outward processes of identity work, we enhance the understanding of identity work as an agentic act that involves interpretive, knowledge mobilization, and sequential dimensions.

By focusing on knowledge boundary spanning, this study exemplifies the agentic effort underlying identity work of migrant entrepreneurs in overcoming knowledge boundaries and initiating interfirm cooperation. The data demonstrates how sensemaking and self-reflectiveness (as part of inward identity work) and relational process of identity negotiation (as part of outward identity work) enable the actors to span knowledge boundaries. Although scholars have explored certain dynamics of identity work in the knowledge boundary-spanning process, the main context has been mainly global organization settings (Au & Fukuda, Reference Au and Fukuda2002; Brannem & Thomas, Reference Brannen and Thomas2010; Brown, Reference Brown2015; Kane & Lavina, Reference Kane and Levina2017; Thomas, Reference Thomas, Alvesson, Bridgman and Willmott2009; Yagi & Kleinberg, Reference Yagi and Kleinberg2011). Thus, our study provides a more focused exploration of the process of knowledge boundary spanning in the context of migrant entrepreneurship. It does this by offering fresh insights and theoretical perspective on migrant entrepreneurs’ identity work by conceptualizing hybrid identity work and showing how it emerges in the process of knowledge boundary spanning.

The analysis also highlights the sequential dimension of agency. This is best illustrated by the observed phases of hybrid identity work: (1) identifying identity differences; (2) adopting identity cues; and (3) realizing hybrid identity.

Third, in the periphery, this study also adds to the knowledge literature by illuminating the identity processes that facilitate knowledge boundary spanning. It is expected that building interconnectedness allows people to overcome knowledge boundaries by engaging in knowledge fertilization (Dokko, Kane, & Tortoriello, Reference Dokko, Kane and Tortoriello2014). Nevertheless, knowledge fertilization does not always ensue from structural opportunities: it requires motivated boundary spanners. As argued by Fischer et al. (Reference Fischer, Dopson, Fitzgerald, Bennett, Ferlie, Ledger and McGivern2016), deep personal engagement and identification with knowledge are pivotal. Following this line of thought, unlike organizational sociologists who have commonly regarded the cooperation between insiders and outsiders motivated by exogenous factors, ‘such as the distribution of technological resources or the social structure of resource dependence’ (Gulati & Gargiulo, Reference Gulati and Gargiulo1999: 1440), this study focuses on endogenous factors (e.g., shared norms and values) that influence actors’ identity adjustment and the initiation of interfirm cooperation. These factors emphasize the importance of social fit, over a purely strategic one (e.g., based on transaction cost economics). Although the ‘exogenous approach to tie formation provides a good explanation of the factors that influence the propensity of organizations to enter cooperation, […] it overlooks the difficulty they [social actors] may face in determining with whom to enter such ties’ (Gulati & Gargiulo, Reference Gulati and Gargiulo1999: 1440). This suggests that the exogenous approach could not fully illuminate the dynamics, occurring when developing the hybrid identity that enables interfirm cooperation. Recognizing the difficulty, which migrant entrepreneurs experience when attempting to cooperate with resourceful actors is of significant importance, as it allows us to better capture how migrant entrepreneurs maneuver in a challenging environment, defined not only by the peculiarities of the host-country market environment but also by those of the social one.

We adopt the epistemological stance that strategic fit is not enough for initiating a collaborative partnership (Gomes, Weber, Brown, & Tarba, Reference Gomes, Weber, Brown and Tarba2011). We reveal how migrants’ identity is transformed to establish a better fit between their identity background and that of desired partners. By doing so, this study directs attention to the identity work-driven knowledge boundary-spanning process that migrants undergo. It argues that the interplay of inward and outward identity work that they undertake allows them to reach a legitimate hybrid identity that facilitates interfirm cooperation. In this way, the identity work perspective introduced here highlights agentic issues that are often overlooked in the knowledge literature.

Fourth, this study also contributes to identity work research by illuminating the balancing forces (inward and outward) that occur within the hybrid identity development process. This study takes on identity work as a compelling construct that allows us to see how migrants get rooted within knowledge boundaries in the host environment. Identity work highlights individuals’ visceral connection to the knowledge boundaries they would like to relate to, which other constructs may underplay (Ashforth, Harrison, & Corley, Reference Ashforth, Harrison and Corley2008). However, although the pursuit of adopting identity zealously may enable knowledge boundary spanning, over-identification may diminish the benefits expected to stem from relating to a new knowledge boundary. For example, fully adopting host-country notions of doing business may prevent migrant entrepreneurs from cross-fertilizing the knowledge boundaries they bridge (Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, McCarthy and Satinsky2018). Thus, over-identification may lead to dysfunction. To tackle this issue, the current study offers a more process-oriented model that depicts migrant entrepreneurs’ efforts to reconfigure their identity (i.e., develop hybrid identity) via an interplay of inward and outward identity tactics. By doing so, this article provides insight on the balance between adjusting identity for enabling interfirm cooperation while maintaining a functional identification that does not transcend to over-identification and therefore potentially higher knowledge management opportunity costs.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This work is not without limitations. Besides the small sample size, which impedes the replicability of the study, the chosen sample at least partially impedes its validity as well. This is because the sample constitutes only entrepreneurs who have succeeded in building interfirm cooperation. It can be argued that successful migrant entrepreneurs have shown the ability to develop a hybrid identity by utilizing the interplay of the inward and outward identity work tactics that were introduced in this study. However, this observation can be triangulated by conducting a comparison with failed entrepreneurs and the identity work they went through. Such a comparison may allow a more nuanced understanding of the identified hybrid identity work stages. Furthermore, in our research, we focus on the individual level of analysis, thus we did not observe closely the significance of factors such as the company age in the host country and how this may influence specific firm outcomes. Future research studies may benefit from taking into consideration the moderating effect of the company age, number of employees, when exploring identity work processes, and tactics in migrant entrepreneurial ventures at the firm level. In addition, a subsequent comparison study with failed entrepreneurs can fully illuminate the dynamics and the challenges occurring when executing identity work.

Moreover, British society is multicultural, thus, it can be argued that it consists of nested and crosscutting identities, that is, individuals identifying with multiple loci. Due to data limitations, the local British entrepreneurial community is treated as a uniform entity. We encourage future research to utilize the identity-matching principle (IMP) developed by Ullrich, Wiseke, Christ, Schulze, and Van Dick (Reference Ullrich, Wiseke, Christ, Schulze and Van Dick2007) and scrutinize communication examples between native and migrant entrepreneurs. IMP will allow tracking the antecedents of nested identifications and illustrating their relation to socialization outcomes.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or its supplementary materials].

APPENDIX I Questionnaire with Potential Prompt Questions

1. Would you tell me about your background and your life before the opening of the company?

2. What/who influenced your decision to establish this particular kind of venture?

3. Do you think that the business environment in the home or the host country has changed since the establishment of your company?

– Prompt 1: In what way, if any, it has affected your company and your decision-making?

4. How many business entities do you currently own/manage, and are there any you have owned/managed in the past that you are no longer involved with, in that capacity?

– Prompt 1: How did the experience from the first one help you in the development of the other entities?

– Prompt 2: Did you/do you use the contacts that you have built for the first entity for any of the operations of the other entities?

– Prompt 3: How many firms have you founded/been involved in the founding of?

5. Why did you establish your business in the UK instead of in your home country?

6. Do you remain affiliated with your home country?

– Prompt 1: If yes, how? If no, why?

7. Do you participate in one or more organizations with links to your home country or another country in which you conduct business?

– Prompt 1: If you do, to what degree do you participate in organizations with links to your home country?

– Prompt 2: What is the purpose of your participation in such organizations?

8. Have you hired compatriots from the organizations/social circle you engage in?

– Prompt 1: What are the main reasons you have hired compatriots?

9. Who is your primary targeted market, the home country or the host country?

– Prompt 1: If it is the host country, is it your compatriots living in the host country or the native population of the host country?

10. Do you conduct business communications with the home country, and if you do, how frequently?

– Prompt 1: How do you conduct business communication?

– Prompt 2: Why do you conduct business communication in that manner? – any advantages and disadvantages

11. Have you achieved company growth? Do you aim at company growth or not?

– Prompt 1: What are the reasons for your company's growth?

12. What are the common types of business problems that you face?

13. What do you recognize as an area for improvement in your business?

– Prompt 1: How do you recognize an area for improvement in your business?

14. Who do you discuss your business issues with?

– Prompt 1: Do you discuss business issues with people from the host or the home country?

– Prompt 2: Do you discuss business issues with a particular organization or its members?

– Prompt 3: How does that help?

15. How do you realize business communication?

– Prompt 1: How do you relate to local entrepreneurs?

– Prompt 2: Is the way you relate to Brits different from the way you relate to others?

16. How do you generate ideas that support your business activities?

– Prompt 1: Example

17. How do you generate business solutions for particular problems that your business experiences?

– Prompt 1: Example

18. To what extent do/did you experience problems due to the newness of your company in the starting period?

– Prompt 1: What is the most common set of problems that your company's newness brought?

– Prompt 2: How do/did you overcome these newness problems, if any?

19. To what extent do/did you experience problems due to being a foreign entrepreneur in the host country?

– Prompt 1: What is the most common set of problems that your company's foreignness brought?

– Prompt 2: How do/did you overcome these problems resulting from foreignness?

20. How important is decision-support information (e.g., information about potential risks and opportunities) for your business success?

– Prompt 1: How important is the speed of distributing such information for your success?

– Prompt 2: How do you translate information into actions?

– Prompt 3: Do you relate higher access to information to higher competitiveness?

– Prompt 4: Are you trying to build links to information sources?

– Prompt 5: Are you trying to increase/strengthen already existing links to information sources? How?

– Prompt 6: In what aspects of your business does information play a significant role?

– Prompt 7: How do you embed yourself into local knowledge flows?

21. In what stage of your business development have you started thinking about access to relevant knowledge (experience or theoretical and practical understanding of the industry in which you operate and how you can manoeuvre in it)?

– Prompt 1: What are the major impediments to relevant knowledge?

– Prompt 2: How do you overcome these knowledge impediments?

22. Do you experience competition for such information?

– Prompt 1: Who are your major information competitors?

– Prompt 2: How do you compete/attempt to compete for information?

– Prompt 3: What are the tools or techniques that help you gather relevant information and evaluate business options?

23. Whose survival prospects do you think are higher – these of native entrepreneurial companies or these of entrepreneurs like you, coming from abroad?

– Prompt 1: Why do you think they go under less/more often?

– Prompt 2: How are you similar/different, given that you have survived?

– Prompt 3: From your perspective, what constitutes the main difference between native entrepreneurs and foreigners who come to conduct business in the UK?

24. Have you experienced the bankruptcy of similar-sized native entrepreneurial companies in your industry/city?

– Prompt 1: At what stage do they fail most often?

– Prompt 2: Why did they fail?

– Prompt 3: Were they competitors?

25. Have you experienced the bankruptcy of similar-sized migrant entrepreneurial companies in your industry/city?

– Prompt 1: At what stage do they fail most often?

– Prompt 2: Why did they fail?

– Prompt 3: Were they competitors?

26. What has increased the chances of survival of your business in the host country?

– Prompt 1: The lack of which factor would have resulted in the poorest business performance of your company?

27. The abundance in which of the following factors would have contributed most to the better business performance of your company?

– 1. Social contacts in the host country

– 2. Social contacts in the home country

– 3. Technology

– 4. Access to information

– 5. Ethnic market in the host country

– 6. Others

28. Who do you count on for improvements with regard to the above-selected factors you recognize as important for your business development?

29. How important is information technology for the current stage of development of your business?

– Prompt 1: How do you assess technology's function in your business processes?

– Prompt 2: What are the main aspects of your business activities that are facilitated by information technology?

– Prompt 3: To what extent, if at all, does information technology influence your business communication practices?

30. Do native or other migrant entrepreneurial companies constitute stronger direct competitors for your business?

– Prompt 1: Do you consider your business more competitive than those of your direct competitors?

– Prompt 2: In what aspects do you believe you are better positioned than your competitors?

– Prompt 3: What is your observation on your direct competitors – to what extent, if at all, does information technology influence their business communication practices?

31. What marketing tools, if any, do you use to promote your company?

– Prompt 1: Who is the targeted audience of your marketing activities? Is it the potential customers only or other parties as well?

– Prompt 2: How effective are the marketing tools that you use?

– Prompt 3: What internet marketing tools, if any, do you use to promote your company?

– Prompt 4: Who is the targeted audience of your internet marketing activities?

32. How would you rate the importance of personal networking for business development?

– Prompt 1: What are the benefits that your business has seen from your personal networking?

– Prompt 2: With whom do you normally network?

– Prompt 3: Where do you normally network?

33. To what extent do you use virtual professional networks (e.g., LinkedIn) for your business purposes?

– Prompt 1: What type of people/organizations do you get linked with?

– Prompt 2: What are the main purposes for which you use virtual professional networks?

34. Is there anything relevant to the subject of the conversation or to your professional success that we have not discussed?

APPENDIX II Observation Framework

I. Context:

(a) Previous situations

(b) Following situations

(c) Instigator of situations

(d) Frequency of the situation

(e) Attributes of the enterprise

(i) Duration

(ii) Material objects (furniture and interior design)

(iii) Location

II. Structure:

(a) Social actors

(i) Number of people

(ii) Composition

(iii) Responsibilities

(iv) Status

(b) Authority and role structures

(i) Official central regulations

(ii) Self-government

(iii) Hierarchy of authority and communication

(c) Leader's style

(i) General behavioral observations (presence, activities, and interactions)

(ii) Specific behavioral observations (according to particular situations)

(iii) Communication style

(iv) Effect of the communication style

(v) The leader's normative orientation (attempts and intentions of the actor toward particular situation)

(vi) Effect of the actor's normative orientation

III. Processes:

(a) Stimuli and reactions of the people involved

(b) Sanctions (reward and punishments)

(c) Goals – theme, object of orientation

(d) Media of communication (speech, gestures, mimic)

(e) Results of the interaction

(f) Participation in activities and social groups

(i) External activities, groups, and organizations

(ii) Internal activities, groups, and organizations

(iii) Benefits (personal and public)

Adapted from Friedrichs and Ludtke (Reference Friedrichs and Ludtke1975: 43)