This study provides an overview of the history of Ottoman craft guildsFootnote 1 from the seventeenth century to the early nineteenth century, focusing on three major developments that had a significant bearing upon the evolution of these organizations during that time. The first concerns demographic movements of the late sixteenth century and the Celali rebellions, which prompted the craft guilds in certain urban centres of the Ottoman Empire, including the capital, Istanbul, to adopt certain strategies of exclusion or inclusion in response to the flood of people from rural areas.

The second development relates to the changing attitude of the Ottoman state towards the pious foundations (ewqaf) that held the proprietorship of the commercial buildings where craftsmen practised their trades and sold their products. From the beginning of the eighteenth century, the growing burdens on state finances caused by long-lasting wars led governments to reassess and revise traditional policies towards pious foundations, turning to the habit of confiscating foundation properties and appropriating their tax-exempt revenues, which was against the principles of the Islamic law but conveniently justified by religious decrees (fetwas) issued by the highest religious authorities. Accordingly, in this part of the study an attempt is made to trace the effects of that development on the structure and operation of Ottoman craft guilds.

Lastly, we would like to draw attention to the importance of the gedik, an eighteenth-century institutional innovation which granted the masters of a particular craft the exclusive right to practise their craft as well as to the usufruct of the tools and implements in their workshops. From its inception, the new practice triggered a historical process whereby a great number of masters found it more advantageous to practise their crafts as independent operators rather than under the strict surveillance of guilds. Those master craftsmen viewed the rights attached to their gedik certificates as providing a legitimate ground for adapting to changing market conditions, which increasingly were becoming unsupported by the traditional dynamics of guild-based craft production, something particularly true of crafts engaged in export-oriented production such as silver-thread spinning.Footnote 2 Where the long-term structural effects of the new practice upon the evolution of Ottoman craft guilds (mainly those in the capital) are concerned, the emergent attitude on the part of the craftsmen during the second half of the eighteenth century merits particular attention.

During the period under discussion, it appears that many craftsmen began to hold their gedik certificates as collateral against credit from the merchants, and their failure to pay their debts on time resulted in the sale of their certificates, surely an unintended consequence of the gedik, and a development having multiple effects upon craft guilds. On the one hand, after having lost their certificates, master craftsmen sought to practice their crafts outside the area designated for their guilds, while on the other the selling of gedik certificates enabled people with no artisan background to enter the guilds. Thus the gedik implied not only the spatial disintegration of the guild system but also significantly hampered its hierarchical workings in the long run.

There are various reasons for choosing the early seventeenth century as our starting point in the era we intend to study here. First of all, only from around that time is systematic and more or less complete information available about craft guilds in any particular urban setting of the Ottoman Empire, in this case Istanbul, and there is detailed original information about similar organizations in some other major cities of the Ottoman Empire such as Cairo, Jerusalem, Bursa, Aleppo, and Damascus.Footnote 3 The voluminous travel account of Evliya Çelebi provides a full description of the craft guilds of Istanbul, and accordingly gives us some sense of the size of the population enrolled in them there.Footnote 4

Second, Ottoman social and economic history as a field of research is still embryonic and the emphasis of existing scholarship is largely on the well-documented periods and regions of the Ottoman Empire. Scholarly research on the social and economic history of the Ottoman Empire has concentrated primarily on the early modern period, which allows us by comparison and contrast to draw some tentative conclusions about the workings of the craft guilds throughout the Ottoman imperial lands.

As for the concluding date, it is important to note that the early nineteenth century marked the beginning of a series of revolutionary changes in the institutional framework of the Ottoman state, culminating in the comprehensive reform programme of 1839, known as the Tanzimat, which incorporated changes, including the abolition of the Janissary corps, an old and well-entrenched institution.

Once the Janissary corps was abolished, the Ottoman bureaucracy assumed full control of the state and tried to transform it to a more secular basis with less control over its social and economic institutions. Craft guilds, which had been the principal organizations of production throughout the Ottoman territories since the classical age, were exposed by the process to significant revisions and many of them, already dissolved into individual enterprises, lost not only most of their traditional privileges in receiving raw materials and enjoying various government subsidies, especially in the field of taxation, they were subjected too to the newly crafted economic reforms of the Tanzimat regime.

The abolition of monopoly (inhisar), which had become indivisible from guild-based craft production throughout the early modern era, was one of the major goals of the Tanzimat reforms, during a time too in which craft production suffered a major setback due the fatal effects of the commercial treaty signed with Great Britain in 1838, a subject well-covered by modern scholars.Footnote 5 That agreement with Britain radically revised existing customs rates on imports and exports in favour of foreign merchants, and considerably increased the advantage of foreign over domestic goods in the Ottoman market.

In the early 1860s, the Tanzimat government created the Industrial Reform Commission to reorganize the craft guilds of the Empire into several major “corporations”, an attempt to revitalize the traditional forms of production and labour but which was aborted by the Commission’s abolition.Footnote 6 Ottoman craft guilds, both in the capital and the provinces, experienced an all-out decline until their official abolition from 1910–1912.Footnote 7 “Craftsmen’s associations”, created around the same time by the Young Turks as a substitute for the traditional organization of craft guilds, proved to be a limited success for the nationalist project of the Young Turk government, and their subsequent demise marked the formal end of Ottoman guilds in the early Turkish republic during the 1920s.

The geographical range of the present study of the Empire’s provinces and cities is necessarily uneven. Apart from certain reflections on the Balkans, the focus of the present article is biased towards the regions contained within the borders of modern Turkey and Syria, and, as the capital city of the Empire, Istanbul receives disproportionate attention due to the richness of the available material. The reason for reserving more space for the Balkans among the Ottoman provinces is that a considerable amount of research concerning guild organizations for the area has emerged over the past few decades. This article offers some comparative insights into the historical development of different regions and societies of the Ottoman Empire.

The study of Ottoman guild history has traditionally been dominated by a state-centred perspective which reduces the importance of the human side of guilds in favour of their institutional structures. Students of Ottoman craft guilds have tended to emphasize their administrative and financial functions at the expense of their economic and social functions, so that little or no attention has been paid to the problems of craftsmen as producers and people. There is no doubt that denying the agency of the producing populations of the Ottoman Empire will continue to prolong the difficulties in reconstructing the normal course of Ottoman pre-industrial craft production in particular, and in writing the economic history of the Ottoman Empire in general.Footnote 8 In the absence of such attempts, there is no way of undoing the conventional Orientalist notion of Islamic society, with its assumption that the Ottoman social and economic system changed little, if at all, over the centuries except where European intervention disturbed its functioning. It is now widely believed that only after the complete undoing of this thesis will the Ottoman Empire be given its proper place in world history. It is to this undoing that the current study aims to contribute.

At the outset it is important to say a few words about the general characteristics and functions of Ottoman craft guilds. Like European craft guilds, the Ottoman variety were urban industrial organizations in which manual work or handicraft production were organized by people of the same occupation who provided each other with mutual support and agreed to follow a number of internal rules. As local organizations of industrial producers they were in full control of product quality, set prices for raw materials, helped government authorities with tax collection, and, when required, appear to have supplied goods and services to soldiers on campaign. Ottoman craft guilds had close relations with the government, from which they obtained licences to assert their monopolistic role in the production or sale of certain commodities – characteristics and functions they shared with their European counterparts.

Their origins, like those of the European guilds, remain something of an enigma. As far as a Byzantine institutional ancestry is concerned, not much is known about craft organizations in Constantinople during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when production by Byzantine artisans was at its lowest ebb and the guild system was in the process of disintegration.Footnote 9 What little is known about the Byzantine guild system dates from the tenth century thanks to the well-known Book of the Eparch, which contains some valuable information about the organizational, ceremonial, and fiscal aspects of Byzantine guilds.Footnote 10 But that information is inadequate for forging a plausible connection between the Byzantine and Ottoman systems of craft organization.

It is difficult to say to what degree elements of the Byzantine guild system were preserved and passed on to Ottoman guilds, but it is more or less agreed that craft guilds with similar characteristics and functions existed with greater or lesser differences in almost all principal towns and cities of the seventeenth-century Ottoman Empire. Whether or not they were encouraged or instituted by the hand of the state is a question that will have to be answered when more documentation becomes available.

Another important issue awaiting further investigation is the relationship of the Ottoman guilds to religion. Early students of the subject explored the links between the religious brotherhoods (akhis) of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Anatolia and the guild system of later periods,Footnote 11 arguing that the origins of Ottoman guilds should be sought in those urban groupings whose religious values and ceremonials seem to have been fully incorporated into the mental framework of Ottoman guildsmen.

There is a grain of truth in that generalization, since many Ottoman guilds seem to have designed their associations and commitments with reference to futuwwatnames, documents that enumerate a system of virtues, such as modesty, self-abnegation, and self-control, collectively known as futuwwa, and central to the constitution of the akhi brotherhoods. With their emphasis on morals and ceremonials as the principal constituents of the mindset of Ottoman craftsmen, those writings have prompted some historians of an Orientalist proclivity to make some sweeping statements regarding the economic behaviour of Ottoman craftsmen, claiming that they responded to the dramatic economic changes of the sixteenth century, such as the shift of trade routes away from the Mediterranean and the contraction of international markets, by upholding the futuwwa ethics, that is by emphasizing these values of modesty and with them a kind of egalitarianism.Footnote 12 In the view of such historians, this culture of poverty, drawing on the ideological precepts of the Ottoman economic approach, offers a piecemeal explanation of why Ottoman craft producers failed to make the transition to capitalism.

More recently, that view has been revised and some scholars have shown that the access of Ottoman craftsmen to international markets did not dwindle as significantly as assumed by Orientalists, nor did the craftsmen resort en masse to soul searching when faced with new challenges.Footnote 13 In the light of those new findings, the religion-bound conception of Ottoman guilds and guildsmen needs to be reconsidered.

In the early modern period, the Ottoman Empire stretched from Austria to the shores of the Caspian Sea, and throughout the Empire major commercial centres such as Belgrade, Bursa, Adrianople (Edirne), Cairo, and Aleppo grew at an impressive rate. With a population of approximately half a million, Istanbul was one of the largest cities in the world between 1560 and 1730,Footnote 14 while Cairo and Belgrade differed rather from each other, but still competed with Istanbul in terms of their growth rate. On the other hand, a city like Kayseri, the second largest city in Anatolia with a population of 33,000 (excluding tax-exempt individuals), was about the same size as Amsterdam, Utrecht, or Barcelona during the same period.Footnote 15 At the turn of the seventeenth century, many Ottoman cities were in the process of unprecedented urban growth, a trend that had been set during the first half of the sixteenth century.

It is now agreed by most students of Ottoman social and economic history that unprecedented developments occurred in the demographic structure of the Ottoman Empire from the Balkans to the Arab provinces during the period from the second half of the sixteenth century to the mid-seventeenth century, a transformation caused as much by the sheer rise in population numbers as by increasing migration to urban centres.

The rural and agrarian nature of Ottoman society faced the first major challenge posed by this secular trend of population growth, which went hand in hand with wholesale urbanization, a process underway simultaneously throughout the entire European continent. In the course of it, a whole set of “push” and “pull” factors combined to produce a huge influx to urban areas of the Ottoman Empire, factors including growing insecurity in rural areas and the ever-increasing pressure of the Ottoman government on taxpayers for further revenue. The increasing number of illegal fees (Bid’at) exacted from the peasants by provincial officials and local notables (ayan) further contributed to difficulties in the provinces, and Halil İnalcık estimates an average increase of 80 per cent in the size of the urban population in the Ottoman Empire during the period.Footnote 16

Against such a background, it is legitimate to ask how these secular trends of population growth and urbanization were reflected in the character of craft guilds throughout the urban centres of the Ottoman Empire. Did they prop up new trends of expansion and development in manufacturing in Ottoman urban areas? How did the urbanization process affect property relations in cities and, by extension, the presence of crafts and craftsmen there? These are rather general questions perhaps, but each deserves its own separate investigation, and what follows is a preliminary attempt to create an agenda for this purpose, which can be used to design micro projects for each of the themes under consideration.

In the first place, it is true that the vast majority in mid-seventeenth-century Ottoman cities were craftsmen of some sort, and carpenters, tailors, weavers, masons, spinners, shoemakers, tanners, blacksmiths, and bakers filled the towns and cities. However, that is not to say that Ottoman urbanization looked the same as in western Europe, where the concentration of the urban population in crafts, trades, and services appears to have been the principal feature. As Suraiya Faroqhi argues for Kayseri, “Quite a few of the townsmen were not craftsmen or merchants at all, but made their living by cultivating gardens, vineyards and even fields. Gardens and vineyards tended to be more profitable in the vicinity of a town”.Footnote 17

Since there are not many studies of Ottoman urban economies, it is difficult to hypothesize a general argument based on Suraiya Faroqhi’s observations on Kayseri for the entirety of the Ottoman Empire, but it is highly likely that the involvement of Ottoman urban populations with agriculture presented some major differences from the experience of their European counterparts. Market gardening was included among the daily activities of some urban populations in Europe, but, as a study of Ankara has documented, agriculture constituted the chief source of income for many people there during the classical age.Footnote 18

Thus, it may be argued tentatively that in the seventeenth-century Ottoman Empire agricultural pursuits of various sorts were always present in and around Ottoman cities to accommodate the migrant populations into the framework of the urban economy. Given the scanty nature of quantitative information, it is hard to postulate the size of migrant populations and the extent to which they were accommodated into industrial or agricultural sectors, but it may be argued on the basis of impressionistic evidence that the rate varied from place to place depending very much on the role of a particular urban economy in local and international trade. The available sources allow us to establish some tentative parameters to speculate on the nature of changes caused by the immigrant populations in various towns and cities of the Ottoman Empire.

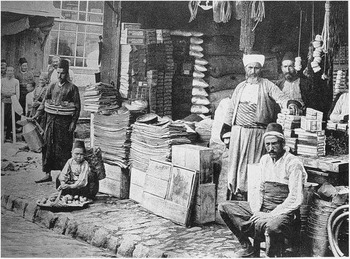

Figure 1 A local shop in Istanbul (nineteenth century). Source: Necdet Sakaoglu and Nuri Akbayar (eds), Osmanli’da Zenaatten Sanata, I (Istanbul, 2000).

Craft guilds in Ottoman urban centres were not as rigidly structured as is traditionally presumed,Footnote 19 and even if there was a degree of rigidity it certainly varied from one type of craft to another depending on the size and nature of the capital involved and the connections of a particular craft to its markets. In that respect, established crafts such as tanning, shoemaking, saddlery, or tailoring were probably stricter in their principles than their equivalents for plumbers or porters.Footnote 20

On the other hand, crafts such as gold- or silversmithing were traditionally confined to family circles, so the admission of unskilled people to their guilds was contingent primarily upon the specifics of each craft. In a city such as Istanbul, when newcomers were barred from entering crafts of their choice, they tended to take up jobs such as vending, which demanded no special prerequisites of capital or skill.Footnote 21

A cursory overview of the published documents points to the growing presence of vendors in the commercial life of Istanbul from the seventeenth and into the eighteenth centuries,Footnote 22 and while there were those who seem to have concentrated on selling silk clothes and other finished textile products, especially of British origin, others became food sellers on the streets of big cities. It should be noted that a large proportion of the labour force required for public works, especially during the “architectural campaign” of Sadrazam Damat İbrahim Pasha, was recruited from amele pazarları (labour markets), where the majority of unskilled, mostly immigrant labourers were readily available for employment.Footnote 23

As early as the end of the sixteenth century, the improvement in market conditions at both domestic and international levels brought about a noticeable expansion of craft production. For example, the number of brocade workshops in Istanbul, which had been officially fixed by the State at 100, increased to 318 in a short period of time.Footnote 24 Beginning in the early seventeenth century, certain other developments of a largely administrative nature further enhanced the role of the guilds in the market. The set of rules, ihtisab, that had customarily determined, among other things, the number of shops for each craft, began to lose their traditional leading role in the market. Mübahat Kütükoğlu’s research reveals that during the seventeenth century craft guilds began to play a more active role in the decision process for determining the number of shops.Footnote 25

Craft guilds usually authorized the opening or closing of new shops and workshops according to the vicissitudes of the market, and when the conditions were favourable migrants were probably seen by established craftsmen as less of a threat, so migrants might be admitted to craft guilds and allowed to open shops. But there were cases such as that of Istanbul’s tinsmiths, where the attempt to open more shops than the market required was curbed by the masters on the ground of bais-i ihtilal (attempt to rebel).Footnote 26

A series of documents published by Ahmet Refik presents a good number of similar cases where Ottoman governments collaborated with craft guilds to eliminate the threats posed to the existence of the guilds.Footnote 27 As will be discussed in the following pages, the emergence of the gedik practice in the capital around 1727 was originally intended to protect members of craft guilds against increasing outside involvement and, thanks to the effective manipulation of government support, the craft guilds of Istanbul maintained their primacy in craft production there for a relatively longer period than in other parts of the Ottoman Empire.

Figure 2 A provincial shop (nineteenth century). Photograph: Leipziger Presse-Büro. Source: Franz Karl Endres, Die Türkei Mit 215 Abbildungen Zusammengestellt und eingeleitet (Munich, 1916).

Nikolay Todorov, who studied the craft guilds in the Balkan provinces of the Ottoman Empire on the basis of judicial records, has documented the presence of a large group of non-guilded craftsmen in various Bulgarian cities.Footnote 28 He explains the situation by reference to the fact that the craftsmen concerned were “artisans who had come from surrounding villages and cities, or had arrived from outside settlements, and by the turn of the sixteenth century they had formed a considerable stratum in the major urban areas of the region”.Footnote 29

Members of craft guilds in Sofia and Ruse were quite reluctant to accept the presence of the practitioners of their crafts outside the organization of guilds, and there was an incident when the shoemakers of Ruse complained to the local state authorities that “several persons alien to the estate” who were not members of any craft guild were making boots and shoes.Footnote 30 In another case, the furriers of Sofia sent representatives to the capital, Istanbul, to report the non-guild activities of “alien” people.Footnote 31 The essence of their complaint was that these “alien” craftsmen were buying skins suitable for processing at a higher rate than the usual prices. The same complaint was echoed in the petition of cap-makers requesting that “all artisans […] observe the established order in both the supply of the raw materials and in the production of the goods”.Footnote 32

In his study of this region, Peter Sugar argues that in the eighteenth century members of craft guilds adapted to the changing vicissitudes of the market in a different way: “The majority of guild members tried to organize themselves both within and outside the guild structure, thereby weakening the guilds even further”.Footnote 33 The eventual outcome of these developments was that many crafts, organized formerly in guilds, came to be practised by artisans with no guild affiliation, and the only crafts which remained unaffected by these developments were those that produced solely for the demands of the Sublime Porte, such as the woollen-cloth-makers of Salonica, who remained the main suppliers of clothing to the Janissary corps.Footnote 34

Unlike the craft guilds in Istanbul, the guilds in various Balkan cities failed to manipulate the support of the Ottoman state to ward off various threats to their existence, including internal migration and price fluctuations. Although their appeals to Istanbul proved inconclusive most of the time, craft guilds in Balkan towns and cities continued for the rest of the eighteenth century to invite government officials to intervene in cases of difficulty, but often to no avail.Footnote 35

Seventeenth-century Bursa holds a special place in the history of Ottoman craft guilds not only because it is one of the best-documented areas of the Ottoman Empire as far as craft guilds are concerned, but also because the city provides us with a picture where craft guilds coexisted with other organizations of industrial production, principally the putting-out system.Footnote 36

The silk industry, traditionally the sector most dominated by craft guilds, provided the major arena in which non-guild individuals, including women and children, were accommodated into the production sphere in their homes with no direct affiliation to craft guilds. It is legitimate to ask whether or not craft guilds in some way participated in the nexus of putting-out production, but the available sources do not permit us to offer any explanation on this issue, although it is highly probable that a great degree of subcontracting was going on in many sectors.

That is best attested to by the fact that many merchants were involved with the organization of silk production and they too fulfilled the tasks of both hiring labour and investing capital. Thanks to growing domestic and international demand, the silk industry provided an environment where these two organizations of craft production were reconciled and so coexisted satisfactorily during the seventeenth century.Footnote 37 The economy of Bursa eventually experienced a significant rate of growth in that period.

The presence of artisans who were not affiliated to guilds is documented as yet another feature of silk manufacturing in Bursa.Footnote 38 Unlike in Sofia and Ruse, where non-guild individuals came from surrounding towns and villages, in Bursa they came largely from within the craft guilds of the city. There is no doubt that the relatively stronger position of merchants in the silk industry contributed a great deal to that situation since they were the most important link in the supply chain of raw material to manufacturers.

In most other cities of the Ottoman Empire, notwithstanding Bursa’s specialization in the production of a particular item, craft guilds were the only institutions that could purchase their required raw materials at fixed prices from commercial agents. Unlike the silk sector, leather production, which constituted the second great manufacturing sector in the city, was almost all organized into tanners’ guilds in the seventeenth century. The members of the tanners’ guild in Bursa received their raw materials under the supervision of guild administrators, and eventually marketed their finished products under the surveillance of their guilds.

A rather similar situation existed in eighteenth-century Aleppo, where the putting-out system in the silk industry thrived thanks to merchants and was later replaced by the “factory system”. Aleppo’s fortunes turned sour at the beginning of the eighteenth century when the collapse of rural and small-town production made it a place “crammed with refugees from an insecure countryside where chances of making a living were extraordinarily slender”.Footnote 39 But from the second quarter of the eighteenth century, the silk industry was revitalized thanks to the merchants who began to commission guild-free artisans. On the other hand, the masters who dominated the craft guilds in the textile industry of Aleppo were encouraged by large market demand to employ most of the incoming population as wage labourers. As Abraham Marcus shows, the majority of the artisans in the textile industry worked on demand, and craft guilds in that sector met the demands only of the internal market in the second half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 40 In Damascus too, craft guilds prevailed over the entire domain of industrial production and prevented outsiders from penetrating their realm. Since the city was the meeting place of pilgrims, economic activity was boosted mainly by those craft guilds which produced solely to meet the demands of pilgrims, who might number 30,000 a year.Footnote 41

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, craft guilds, especially ones involved in textile production, faced competition from various foreign goods, such as British textiles, but as Damascus, being on the way to Mecca, was closed to outsiders for religious reasons, the only threat to its stable economic life during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries came from the members of the local Janissary garrison.

The coming of British textiles, which challenged the predominant role of craft guilds in the late eighteenth century, was mediated largely by merchants and peddlers, who tagged along with Hajj caravans. As Abdul-Karim Rafeq argues, the local Christians who visited Europe also participated in the import of foreign goods, principally textiles.Footnote 42 The heavy flow of British textile imports in the Levant began about the middle of the eighteenth century, until when craft guilds, which were involved in production for long-distance commerce throughout the region, had dominated textile production in the area.

The second development that had a major bearing on the historical evolution of craft guilds was consequent on the changing attitude of the State towards pious foundations. Commercial buildings in Ottoman urban areas, such as bedestans and çarşıs, where the majority of the craftsmen practised their crafts and marketed their products, belonged traditionally to pious foundations (ewqaf), so even the slightest change in the policies of the Ottoman governments concerning them had the potential to affect craft guilds.

Pious foundations were created in the towns and cities of the Ottoman Empire in early times by the sultans, their mothers, and high-ranking state officials. Being financially as well as administratively autonomous, these foundations were responsible for the construction of the cultural and commercial complexes in conquered cities,Footnote 43 and among the types of commercial buildings were bedestans.

As was the case with Jerusalem, the construction or renovation of a bedestan was a salient feature of the Ottomanization of the conquered city.Footnote 44 Having built a bedestan with the forced labour recruited from local populations, Ottoman conquerors would build shops around the outside of the central bedestan, with each group of shops, branching out and lining both sides of a road, forming a single market to be occupied by the members of a single craft or by merchants selling the same type of goods.Footnote 45

In most Ottoman towns and cities in the Balkans, including Tatar Pazarcik, Plovdiv, Sarajevo, Sofia, Skopje, Manastir, Serres, and Salonica, trade centres grew around bedestans, so, as İnalcık puts it, “apart from political formative elements of the Ottoman Islamic city, the main urban zones including the bedestan-çarşı or central market place were brought into existence under the waqf-imaret system”.Footnote 46 The shops and other spaces occupied by the crafts and trades in the city would be attached to the ewqaf, which would demand in return a certain amount of rent from the tenants. These rents provided the basis of a foundation’s income, which would be spent, in addition to certain charitable goals, on maintaining the commercial buildings themselves.

Around the mid-seventeenth century, Ottoman state officials as well as local notables increasingly began to use the foundations to realize their own projects.Footnote 47 As the taxation policy of the Ottoman state was geared towards financing long-lasting wars, many irregular taxes were eventually turned into regular taxes, in the evasion of which officials and notables began to invest their fortunes in the establishment of commercial buildings (musaqqafat) such as bazaars, shops, baths, depots, workshops, bakeries, and mills in the name of some foundation, which secured for them and their heirs a steady source of income. They also launched a campaign to take over, by tax farming and other methods, the governance of existing buildings that were of a commercial nature and which had ceased to generate revenues for use in financing various social services.

Figure 3 Grand Bazaar in Istanbul. Photograph: Sebah & Joallier. Source: Necdet Sakaoglu and Nuri Akbayar (eds), Osmanli’da Zenaatten Sanata, I (Istanbul, 2000).

On the other hand, the same period saw a growing tendency on the part of state authorities to turn over the collection of state revenues to tax farmers (mültezim). Tax farming became more appealing when the Ottoman military machine proved ineffective because of the lengthy wars.Footnote 48 The urgent need of cash to finance these wars and to upgrade the Ottoman army resulted in the extension of tax farming to the remoter sources of the Ottoman budget, and in a new fiscal scheme it extended even to the administration of commercial buildings attached to the foundations of the Ottoman sultans, mother sultanas, and state officials, which were one by one rented out to the highest bidders at auctions. When further sources were needed, one of the harshest policies of the Ottoman state, namely confiscation (müsadere), was available to the government.

Yavuz Cezar has shown that confiscation became an established practice during the eighteenth century, especially in its last quarter, by means of which the inheritance of wealthy individuals, public and private equally, was seized by governments to be converted into revenue-generating units.Footnote 49 Cezar cautions us not to overstate the role of the practice, but it can be hypothesized that it contributed, even if only to a small extent, to bringing the revenues of many commercial buildings under the control of the tax-farming class. Thus, the rental regime, to which each craft guild located in a particular bedestan was traditionally subjected, was transformed onto a new basis whereby rents, which traditionally had been determined by current-market rates, became subject to the will of tax farmers.

The effects of these developments on the members of craft guilds who practised their crafts in these commercial buildings were wide and varied. Master craftsmen and other shopkeepers in previously foundation-owned buildings found that their contracts, namely muqata’a and icaret signed with the trustees of the foundation, were deemed null and void and they were subjected to new regulations. Craftsmen too were confronted with the ever-growing pressure from tax farmers for extra fees, and the combined effects of these developments resulted in craftsmen abandoning their shops. That in turn created a serious problem for the spatial unity of craft guilds, as implied by the idea of bedestan or çarşı. The resistance of craftsmen to the tax farmers took the form of appealing to custom and to shari’a, Islamic law.

In the face of ever-growing pressure from tax farmers, representatives of craft guilds in Istanbul jointly petitioned the Imperial Council in 1805,Footnote 50 one of the rare occasions on which all the guilds combined to voice their concerns over a particular matter. Master craftsmen showed their gedik documents as proof of their ownership of the tools and equipment located in their workshops, and argued that the new development would devastate not only their livelihoods but could disrupt the economic life of the whole Empire. A decree was then issued to prevent tax farmers from interfering in the affairs of craftsmen and other shopkeepers.Footnote 51

In addition to the developments recounted above, there was another source of problems for the craftsmen, and it had persisted since the late sixteenth century, being the ever-increasing number of unskilled individuals practising clandestinely in crafts traditionally confined to members of guilds. During the eighteenth century, complaints became louder still in Ottoman documents, in which craftsmen of all types from tailors to silk-thread spinners appealed to the Imperial Council for help in “eradicating the enemies of order”.Footnote 52

Figure 4 Shopkeepers in Istanbul (nineteenth century). Source: Necdet Sakaoglu and Nuri Akbayar (eds), Osmanli’da Zenaatten Sanata, I (Istanbul, 2000).

As a response to the increasing tendency on the part of non-guild individuals to penetrate their field, members of craft guilds, in cooperation with the government, developed the policy of gedik, whereby the master craftsmen registered their tools and equipment in their own names with the kethüda (warden) of their craft guild, who coordinated relations between the guild and the government.Footnote 53 The importance of that policy consists in its confirmation of the monopoly right of master craftsmen over the production of a particular item, or their role in the production process of a certain commodity. The ideal formula was intended to fix and stabilize the number of master craftsmen specialized in the production of a particular item,Footnote 54 and from its introduction to the economic life of Istanbul in 1727–1728, the gedik licence, given to master craftsmen with the endorsement of the local judge, was transferable from father to son.

The shops and workshops where tools and equipment were stored and where craftsmen practised their trade remained beyond the sphere of the individual rights covered by the gedik licence. In other words, the ewqaf, either run by private administrators (mütevelli) or tax farmers (mültezim), continued to be the sole agencies entitled to the rent revenues from commercial buildings. The master craftsmen authorized to receive gedik licences were given the usufruct of breaches in the traditionally designated area of their guilds only by implication in order to carry out their activities, but once a master claimed the actual ownership of the implements, he was automatically emancipated from the spatial restrictions of the guild system and could move his business wherever he thought was most convenient for him. That development, I believe, played the most crucial role in the dissolution of craft guilds in Istanbul, by breaking up the traditional spatial unity of craft production in the long run.

The gedikization of craft guilds was not a process unique to Istanbul during the eighteenth century. As we learn from Abraham Marcus, craft guilds in Aleppo had resorted to the same practice by 1750 to secure a monopoly over the production process.Footnote 55 And unlike in Istanbul, the term gedik was used only to imply “the right to practice a certain trade or craft in a particular shop or establishment”, whereas for “the right to use tools and equipment” people preferred to use the common term of taqwima. Footnote 56 In practice, when people were transferring their gedik licences both rights were transferred to the prospective craftsman.

The transfer issue emerges as a significant problem here. Although during the early period the conditions under which the transfer procedure could be carried out have not been sufficiently documented for either Istanbul or Aleppo, there is some evidence showing that in each city inheritance from father to son was initially the only way to transfer gediks. If the gedik holder did not have a son capable of succeeding him, the right to the gedik would be transferred with the consent of all craft masters to a senior journeyman. The same method would be devised if the deceased master had a son too young to succeed him, in which case the senior journeyman would be entitled only temporarily to the tenure implied by the gedik.

Within craft guilds, the restrictions on promotion, such as the requirement to work as a journeyman for a certain duration of time, hampered the advancement of skilled individuals, and was further complicated by the rigid implementation of the Islamic law of inheritance, in that when a vacancy occurred it was the immediate relatives of a master, particularly his sons, who were considered first for the position.Footnote 57 Nikolay Todorov, who points to the important role the gedik came to play in the economic life of the Balkan provinces, mentions that this method of transfer was the predominant practice in the region during the eighteenth century. He does not provide any other information than what we know for the cases discussed above.Footnote 58

Why is the issue of gedik so important? That document provided individual craftsman with more room for manoeuvre, including the right to practise his craft wherever he wanted, so it implicitly violated the traditional principle that the members of a craft guild had to exercise their craft in the same location, the same bedestan.

The opening of single shops and workshops outside the working area of a craft, or practising crafts at home for that matter, which had existed as a trend in cities like Bursa, became a widespread practice in Istanbul in the eighteenth century. To curb the tendency, craft guilds often appealed to the government to open workshop and shop blocs, and for example it was in response to such a petition by the shoemakers’ guild of Üsküdar that a new shopping area was designated, and the opening of shops outside that area was prohibited in 1759.Footnote 59

However, the dissolution process began when members of craft guilds began to use their gediks as collateral against loans they took from merchants. As Akarlı shows in his article, the failure of a master craftsman to repay his loans resulted in his implements being auctioned off,Footnote 60 and though we do not have precise information about the frequency of auctions at which gediks were sold off the growing number of complaints by guild members about the increasing number of “outsiders” with gedik certificates can be interpreted as a sign of a steady trend among masters of a failure to settle debts on time.Footnote 61 So it was that many individuals with no experience or training had the opportunity to enter guilds without the consent of other members, but another channel through which “outsiders” gained access to guilds was created by the members of a deceased master craftsman’s family inheriting his gedik and selling it to unrelated individuals.

Despite these problems, the gedik continued to exist as a major mechanism for designating the monopoly rights of a master to a certain craft until the mid-nineteenth century, but by then many master craftsmen had already used the rights attached to their documents to assume full independence, which was facilitated by the combined effects of the rent increases by foundation administrators and the ever-growing tendency of state authorities to confiscate foundation properties and convert them into tax farms. As a result many craft masters moved away to set up workshops in areas where they could pursue their craft with no obligation to anyone but themselves.

The history of Ottoman craft guilds remains something of an enigma. Given the limited scholarly interest in the topic and the absence of relevant archival material such as private records of craft guilds, it is difficult to overcome all uncertainties and to reconstruct this history in a way commensurate with its European counterparts. Here we have dwelt on a number of developments that affected the evolution of craft guilds from the seventeenth century to the early part of the nineteenth century, and have tried to show that the response of local guilds to various developments was in some ways determined by the nature of regional conditions as well as by the general economic conjuncture.

For example, the Bursa silk industry absorbed the incoming populations through the efforts of merchants who sought to expand or change industrial production to suit market requirements and to increase profits. They employed migrants as part of the putting-out system, which, although this constituted a challenge to the very existence of the craft guilds in the sector, seems not to have affected it too drastically, something no doubt helped by favourable market conditions.

On the other hand, craft guilds in Sofia encountered a rather more skilled group of immigrants who immediately opened shops and began practising crafts such as shoemaking. Complaints from guilds remained ineffectual and single-artisan workshops became the dominant form of production throughout most Bulgarian cities of the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth century. The patterns observed in craft guilds in Aleppo, Damascus, Salonica, and especially Istanbul, also differ significantly from each other, just as they do for other developments treated in the subsequent sections.

To conclude, in the age of European expansion, Ottoman society functioned along the lines of its own dynamics. At the same time, it was influenced by forces that had begun to make their effect felt on its markets. The institution of the craft guild is only one example of the kind of response to those forces. Because of the lack of historical documentation, our survey could not be extended to examine changes taking place in the structure of craft guilds, but a more detailed analysis, which will become possible after the completion of our ongoing documentary survey of Ottoman guilds, is likely to confirm our observation that the internal dynamics of those institutions, particularly their hierarchical order, had absorbed the effects of market forces and adjusted to them by the end of the eighteenth century. Hence, unlike most of their counterparts elsewhere in Eurasia, guilds in Ottoman territories were able to survive the immediate effects of the industrial revolution.