1. Introduction

This paper focuses on the use of preverbal so in present-day English. While its use as an intensifier (meaning ‘so much’ or ‘very much’) has been attested already in Early Modern English (OED online, s.v. so, adv. and conj., sense 15), it has only recently acquired emphatic meaning (‘truly’ or ‘definitely’, see OED online, s.v. so, adv. and conj., 2005 Draft Additions). Compare:

(1) I do so love weddings. They're such joy. (SOAP YR Footnote 1 2005)

(2) I'm so ditching school to babysit. (SOAP AMC 2007)

In (1), so can be paraphrased with ‘very much’ or ‘so much’ (I do love weddings very/so much Footnote 2), because it modifies scalar love, indicating degree (viz. you can love weddings above anything else/ a lot/ a little/ not at all, etc.). This paraphrase does not work for (2), however: in this case, so modifies non-scalar ditch, meaning that a degree reading is not accessible (either you ditch school at a given time or notFootnote 3). So in Example (2) does not convey intensity but expresses the speaker's certainty that they are going to ditch school in order to babysit: I'm so ditching school to babysit – ‘I am definitely ditching school to babysit’.

The OED online 2005 Draft Additions mention this function (the modification of verbs, with so meaning ‘definitely’ or ‘decidedly’) alongside so ‘[m]odifying a noun, or an adjective or adverb which does not usually admit comparison: extremely, characteristically’ (3–5) and so not (emphatic not, 6):

(3) You are so caveman. (SOAP AMC 2004)

(4) She's writing a paper on why her family is so unique. (SOAP AMC 2012)

(5) Well, if it's a party, I am so there. (SOAP OLTL 2011)

(6) This is so not a good time. (SOAP GH 2006)

In the literature, these new uses of so are often referred to as GenX so because they seem to have first appeared in the speech of Generation Xers (viz. people born between 1965 and 1980; Zwicky Reference Zwicky2006). The OED online describes so in (2)–(6) as an informal intensifier (‘slang’) that forms ‘nonstandard grammatical constructions’ (s.v. so, adv. and conj., 2005 Draft Additions).

To date, a small number of studies have been concerned with the use of GenX so as a verb phrase modifier (Kuha, Reference Kuha2004; Irwin, Reference Irwin, Zanuttini and Horn2014; Amador–Moreno & Terrazas–Calero, Reference Amador–Moreno and Terrazas–Calero2017; Stange, Reference Stange2017, Reference Stange2021), and the main findings will be summarised in the previous studies section. The present study is based on a survey with native speakers of English, testing their familiarity with preverbal so in a variety of syntactic structures and the extent to which they are active users (RQ 1). It also addresses the question whether speakers distinguish between intensive and emphatic uses of preverbal so (RQ 2). In addition, the responses are used to detect potential speaker effects in relation to age and gender (RQ3).

This article is organised as follows: The next section provides the theoretical background for the survey, sketching the differences between preverbal so as intensifier and as emphasiser. This is followed by a summary of the existing studies concerned with preverbal so. Section 4 presents the focus of the study, the baseline data (SOAP) and the make-up of the survey. In the results section, all three research questions will be addressed in turn. A conclusion drawing parallels to adjective intensification completes the paper.

2. Theoretical background: Preverbal so as intensifier and emphasiser

Adverbs like very or really are known as intensifiers (see, for instance, Lorenz, Reference Lorenz, Wischer and Diewald2002; Stenström, Andersen & Hasund, Reference Stenström, Andersen and Hasund2002; Tagliamonte & Roberts, Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005). These are defined as ‘a word, especially an adverb or adjective, that has little meaning itself but is used to add force to another adjective, verb, or adverb’ (Cambridge Dictionary, s.v. intensifier). Intensifiers are ‘broadly concerned with the semantic category of DEGREE’ (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 589) and are also referred to as intensive adverbs (Stoffel, 1901), degree words (Bolinger, Reference Bolinger1972), adverbs of degree (Bäcklund, Reference Bäcklund1973) or amplifiers (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985).

A relevant distinction concerns splitting amplifiers into maximisers and boosters. The former ‘express an absolute degree [and] are typically used to modify nonscalar items, i.e. items that do not normally permit grading [e.g. completely ignore] or already contain a notion of extreme or absolute degree [e.g. entirely agree]’ (Altenberg, Reference Altenberg, Johansson and Stenstroem1991: 129). Boosters, on the other hand, are used to intensify scalar elements (e.g. love very much) (cf. Altenberg, Reference Altenberg, Johansson and Stenstroem1991: 129) and ‘denote a high degree, a high point on the scale’ (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 590). In old intensifier uses of preverbal so, its function is that of a booster (7), whereas new uses (subsumed under the term GenX so) include the modification of non-scalar verbs (so as maximiser or emphasiser; 8 and 9):

(7) Oh, I so hate it [‘hate it very much’] when my own words are thrown back in my face. (SOAP YR 2008)

(8) I do so [‘fully’] appreciate your sarcasm. (SOAP DAYS 2009)

(9) We are so [‘definitely’] going to make her pay. (SOAP DAYS 2001)

Intensifiers are defined as a ‘functional category’ for they serve as ‘a vehicle for impressing, praising, persuading, insulting and generally influencing the listener's reception of the message’ (Partington, Reference Partington, Baker, Francis and Tognini-Bonelli1993: 178) and are associated with emotional language (Tagliamonte & Roberts, Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005: 289). Emphasisers, on the other hand, ‘have a reinforcing effect on the truth value of the clause or part of the clause to which they apply’ (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 583) and are thus concerned with expressing modality. Emphasisers do not require that the phrase they modify be gradable, but generally assume intensifying meaning if the modified item is scalar (cf. Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 583). Having said this, there are ambiguous cases where it is impossible to determine whether the degree adverb in question serves as intensifier or emphasiser because the modified element can be interpreted either as a predicate or as a proposition (cf. Waksler, Reference Waksler, Baumgarten, Du Bois and House2012). Consider the following example:

(10) You so have a crush on this guy. (SOAP GL 2008)

One reading is with have a crush on this guy as the target predicate of so, indicating that Ashlee from Guiding Lights is very much in love with Cooper. The second interpretation places emphasis on the speaker's certainty concerning the proposition that Ashlee has a crush on Cooper. Unless more context is provided, ambiguous cases like these remain unresolved. However, either way it is clear that force is added to the utterance as such.

Waksler (Reference Waksler, Baumgarten, Du Bois and House2012) calls the new uses of so instances of over-the-top intensification and argues that ‘the speaker's surpassing the usual syntactic, semantic, or pragmatic limits (i.e., ‘going over the top’’) [serves] as a cue to subjectivity [in the sense of expressing the speaker's attitude towards the modified item in question] in discourse’ (Reference Waksler, Baumgarten, Du Bois and House2012: 8). Subjectification is a relevant concept in intensifier research, as the process involves a shift from content to function (which involves delexicalisation and grammaticalisationFootnote 4) as well as a shift from subjective to more subjective meaning (Athansiadou, 2007: 559; see also Nevalainen & Rissanen, Reference Nevalainen and Rissanen2002: 361). Athanasiadou (Reference Athanasiadou2007: 563) sketched a continuum for the subjectification process – i.e., how much stance (in the sense of speaker attitude towards the respective proposition) is conveyed, ranging from subjective (property, e.g. the total amount) to more subjective (quantification, e.g. a total disaster) to highly subjective (intensification, e.g. totally upset) to most subjective (emphasis, e.g. I totally called you last night). Thus, the expanding range of meanings of so can be accounted for by it undergoing a number of connected processes (delexicalisation, grammaticalisation, subjectification).

Last, the concepts of renewal and layering (Tagliamonte, Reference Tagliamonte2008; Bordet, Reference Bordet2017) are used to refer to established intensifiers additionally assuming new functions (layering implies that the different functions co-exist) – as is the case with the innovative uses of so, for instance. Also, intensifiers can experience fluctuation in popularity, fading into the background for a while and reappearing at a later stage with renewed expressive force (recycling; see Tagliamonte, Reference Tagliamonte2008: 391 on so; Bordet, Reference Bordet2017).

3. Previous studies on preverbal so

With studies typically focusing on adjective intensification, verb intensification has not yet received very much attention. Greenbaum (Reference Greenbaum1974) studied verb-intensifier bigrams, concentrating on the intensifiers to see which verbs they most frequently combined with (e.g. I badly . . . – want, need, etc.). Bolinger (Reference Bolinger1972) dedicated a whole chapter to intensifiers with verbs, mainly discussing so. Scalarity is a central aspect (see above), and interestingly, he provides examples with superscript question marks (to indicate their supposed lack of idiomaticity) that are acceptable in present-day English (e.g. ?I so regret my mistake that I'd be willing to do anything to set things right, Reference Bolinger1972: 173).

Due to the lack of adequate data, the diachronic development of GenX so is still a puzzle. Two scenarios have been proposed based on introspection: first, the new uses of so were derived from the ordinary intensifier so via expansion in its syntactic range (Zwicky, Reference Zwicky2010) and second, so actually modifies a ‘silent totally’ (silent in the sense that speakers have it in mind but do not realise it in speech) because so totally exhibits the same range in admissible modifiable phrases (see Irwin, Reference Irwin, Zanuttini and Horn2014 and Stange, Reference Stange2017 for a detailed discussion with sample sentences). While the origins of GenX so remain a matter of debate, it is undisputed that its use is commonly associated with young female speakers (Kenter, Lee & McDonald, Reference Kenter, Lee and McDonald2007; Zwicky, Reference Zwicky2011; Amador–Moreno & Terrazas–Calero, Reference Amador–Moreno and Terrazas–Calero2017; Stange, Reference Stange2020).

Furthermore, it serves to ‘indicate [ ] that the speaker is strongly committed to the propositional content’ (Potts, Reference Potts and Kawahara2004: 130). In fact, Quaglio and Biber (Reference Quaglio, Biber, Aarts and McMahon2006: 713) have observed that ‘the marked position of so enhances the emphatic content of the statement.’ It is thus a perfect means of expressing subjectivity (cf. Athanasiadou, Reference Athanasiadou2007) in that ‘I so love you, Marcus’ (SOAP BB 2008) expresses the intensity of the speaker's feelings. There is conflicting evidence, however, regarding the claim that GenX so often causes the sentence to have a negative connotation (Amador–Moreno & Terrazas–Calero, Reference Amador–Moreno and Terrazas–Calero2017). In SOAP at least, more than half of the utterances invited a positive reading, and the majority of the verbs found to frequently combine with GenX so were positive, too (e.g. enjoy, love, appreciate, look forward; Stange, Reference Stange2021).

Being associated with rather informal spoken language, GenX so is exceedingly rare in corpus data of natural speech and frequencies are difficult to investigate.Footnote 5 Still, the findings combined from introspection, qualitative and quantitative work (Kuha, Reference Kuha2004; Irwin, Reference Irwin, Zanuttini and Horn2014; Amador–Moreno & Terrazas–Calero, Reference Amador–Moreno and Terrazas–Calero2017; Stange, Reference Stange2021) suggest that so can occur in all types of declarative sentences (with ‘no restriction on tense or VP type’ [Irwin, Reference Irwin, Zanuttini and Horn2014: 56]), that it tends to modify the main verb in complex VPs (i.e., with auxiliaries and/or modals [Kuha, Reference Kuha2004; Stange, Reference Stange2021]), that it is more frequent with full verbs than with modals (but then full verbs are more frequent than modals in general), and that it favours first person subjects unless it occurs with the going to-future (second-person subjects preferred; Kuha, Reference Kuha2004; Stange, Reference Stange2017, Reference Stange2021).

As to its distribution across the various syntactic contexts, in a corpus-based study on preverbal so in scripted speech, it was most frequently attested with simple forms (11; 5.65 occ. pmw), progressives (12; 4 occ. pmw), and the going to-future (13; 1.46 occ. pmw), followed by modals (14; 1.31 occ. pmw) and perfects (15; 0.5 occ. pmw) (Stange, Reference Stange2021).

(11) I so hope they find him (SOAP GL 2009)

(12) We are so beating them up right now. (SOAP BB 2004)

(13) I'm so gonna be in that lake before you. (SOAP GL 2007)

(14) You know, I would so love to believe that. (SOAP AMC 2010)

(15) Well, you have so come to the right place, just not the right night. (SOAP AMC 2006)

Preverbal so also occurs in questions and imperatives with adhortative let, albeit extremely rarely (Stange, Reference Stange2021). Moreover, truly innovative (‘GenX’) uses include the co-occurrence with the going to-future and with progressives, and with non-scalar verbs in general (emphatic use of so; Stange, Reference Stange2021). So has thus seen two extensions in its features: first, from intensifier to emphasiser (function), and second, from modifying scalar verbs in simple or perfect forms to modifying verbs in progressive tenses and with the going to-future (form).

As regards potential changes in frequency, the SOAP data (2001–2012) showed a peak in the use of GenX so around 2008, and a steady decline in frequency from 2010–2012 (Stange, Reference Stange2017, Reference Stange2020). It was not entirely clear whether this drop was real because the data sets were quite small between 2010 and 2012, but it might be that it has in fact become less popular since the late 2000s.

As a large proportion of the findings presented here are based on scripted data and we do not know how reliable and representative they are, a reality check with speakers of English seemed in order: Can we detect the same tendencies with respect to the observed syntactic patterns and their frequencies relative to one another (e.g. constructions with BE so going to seem to be more common than utterances containing DO so V) in authentic spoken language? Are speakers aware of the different meanings of preverbal so as listed in the OED? Do speakers of a certain age and/or gender tend to use preverbal so more than speakers of a different age and/or gender?Footnote 6 Therefore, the three questions that the survey will address are:

(7) Which of the structures sound familiar and which ones are used actively?

(8) Do speakers distinguish between intensifying and emphatic uses of so?

(9) Do we find speaker effects for age and/or gender where the use of pre-verbal so is concerned?

Wherever appropriate, I will include relevant comments from the respondents on the use of preverbal so that they could leave on several occasions when completing the survey.

4. Research design

4.1 Focus of the study

This study focuses on the use of preverbal so in fully-fledged affirmative declaratives (thus: no negations, no elliptic utterances, no questions or imperatives). The aim was to test preverbal so in an environment with as little variation as possible (thus: fully fledged affirmative declaratives only), while at the same time exploring it in a wide range of syntactic constructions. The purpose of this survey is to find out which of the structures observed in SOAP sound familiar to native speakers of English, and which of the structures they claim to also use themselves. In addition, to determine if speakers discriminate between intensive vs. emphatic uses, they were asked whether they think that so always has the same meaning in the sentences presented to them.

4.2 The baseline data

The baseline data is drawn from the Corpus of American Soap Operas (100m words, 2001–2012; Davies, Reference Davies2011–). The transcripts contain scripted speech but they aim at reflecting natural speech, of course. Unfortunately, available corpora of natural spoken language are either not informal enough or too small to contain enough informal language, so they are of little to no help in investigating innovative and informal uses of preverbal so. Concerning the adequacy of soap operas to investigate features of informal spoken language, the interested reader is referred to Stange (Reference Stange2017, Reference Stange2020) where the suitability of such data for the investigation of GenX so is discussed extensively. Suffice it to say at this point that ‘media language actually does reflect what is going on in language, at least with respect to the form, frequency, and patterning of intensifiers’ (Tagliamonte & Roberts, Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005: 296; see also Quaglio, Reference Quaglio2009; Al–Surmi, Reference Al–Surmi2012; Queen, Reference Queen2015).

For now, soap operas are the best data we have to explore how GenX so is used in conversation. Once adequate data of natural language becomes available, the findings could be compared to see how authentic scripted dialogue is regarding this phenomenon, or whether it is a stylistic feature of soap operas or emotional discourse more generally.

In SOAP, the total number of occurrences of preverbal so in affirmative declaratives amounts to 1,136 tokens (11.27 occ. pmw). See Stange (Reference Stange2021) for details concerning extracting and identifying relevant data. Table 1 lists the structures attested in SOAP, providing the number of tokens (raw) and sample sentences.

Table 1: Frequency ranking of structures containing preverbal so in SOAP (affirmative declaratives only)

4.3 Survey data

The survey was conducted using the interface at www.umfrageonline.com and circulated via a variety of mailing lists (see the appendix for a template of the questionnaire). No money was paid for completing the questionnaire. The participants were asked to reveal their age and gender and to indicate whether they are native speakers of English or not. If they were native speakers, they could name the variety they speak. The non-native speaker data was set aside for a different study.

The questionnaire included all of the structures as listed in Table 1, except for so AUX (elliptic utterances in which a part of the sentence has been omitted but is recoverable from the context; see note on focus of the study above):

(2) What, what, do you think I was hitting on him or something? Because I so wasn't [hitting on him]. (SOAP OLTL 2005).

The survey contained three sample sentences for each syntactic structure (27 in total, most of which were drawn from SOAP) to ensure that they would rate the form, not the meaning of the respective utterance (viz. the aim was to find out whether the respondents were familiar with the structure as such, and not with the individual sample sentences as these are too specific). To allow testing for this large range in syntactic variation, the respondents were told that the main concern was the use of so in the sentences presented to them.Footnote 7 The participants were asked to indicate for each structure whether they would use it or not, or if they had heard other speakers use it or not. The answer options were:

1 I use sentences like the ones above.

2 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

3 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

4 a blank field for individual comments if none of the above answers seemed to fit

In a next step, the participants were shown preverbal so in five different sentences and asked to determine whether so always has the same meaning. The sentences were:

(1) I'm so looking forward to seeing you again.

(2) I so should have called my mother.

(3) I have so wanted to meet you.

(4) I'm so going to find out what happened.

(5) I do so love you.

The aim here was to see whether speakers distinguish between intensifying (‘very much’) and emphatic (‘definitely’) uses of preverbal so as listed in the corresponding entries in the OED (2005 Draft additions and sense 15 for s.v. so, adv. and conj.). The answer options were: ‘yes’/ ‘no’/ ‘not sure’. Participants providing the answer ‘no’ were directed to a separate page in the survey in order to elaborate on the perceived differences in the meaning of so. The survey concluded with a blank field for additional comments about the uses of so as listed in the survey.

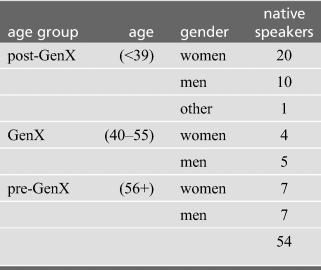

The analysis draws on the completed surveys of 54 native speakers of English, aged between 19 and 82 (see Table 2 for details). As the new uses of so are associated with Generation Xers (Zwicky Reference Zwicky2006), and as the birth date for Generation Xers is typically dated between 1965 and 1980, the respondents were grouped as belonging to Generation X, as preceding or following it, depending on the age provided in the survey (the ages given in Table 2 reflect the participants’ age in 2020). The ratio for female participants was 57 per cent (31/54). 33 respondents spoke US English, 14 British English, three Scottish English, two Irish English, and two Australian English.

Table 2: Respondent speaker groups

5. Results and discussion

5.1 Familiarity and active use (RQ1)

All of the structures presented to the participants were familiar across BrE, AmE, ScE, IrE, and AusE, in the sense of the subjects claiming to have just heard them or to use them actively. The levels of reported familiarity varied considerably, however. They were highest for BE so going to V, BE so Ving and HAVE so Ved (100%, 99%, 94%; see Figure 1). MODAL so V, so V and DO so V were also quite familiar in that roughly eight out of ten native speakers declared to know them. The responses suggest that preverbal so is indeed used in a variety of verbal constructions, or else the participants would not have claimed to recognise it.

Figure 1. Preverbal so – reported familiarity and active use (N=54 for each context)

Interestingly, the ranking for reported active use is not exactly the same as for reported familiarity (Figure 1): all of the native speakers claimed to have heard others use BE so going to V, but only (roughly) every other native speaker said they use it themselves (rank three). The most frequent structure in active use was preverbal so with progressives (99 per cent familiarity), which three out of four respondents labeled as part of their active language.Footnote 8 It is noteworthy that, both in terms of familiarity and active use, it is the new uses (so with the going to-future and with progressive forms) that feature among the top 3. What is more, the responses corroborate findings as indicated by earlier studies (Kuha Reference Kuha2004; Stange, Reference Stange2021), in that speakers prefer placing so before the main verb in a sentence (unless it contains semi-modal going to), given alternatives are available (e.g., MODAL so V is preferred to so MODAL V)Footnote 9, see also comment a.:

a. They nearly all sounded natural to me, but I wasn't sure how often I use them though. One set that was less natural was ‘so’ before the auxiliary verb (I so am going to . . .) – I really wanted to fix those to after (I am so going to . . .)

Incidentally, some of the participants had different judgments concerning the individual sample sentences for a given structure. This concerned, for instance, preverbal so with simple forms. The examples given were:

(16)

(1) I so love chocolate.

(2) He so annoys me.

(3) You so deserve this job.

As many as five native speakers stated that ‘(3) is OK, the others are not’. For the other two sentences, they would prefer so much placed after the object (I love chocolate so much, He annoys me so much). Apparently, some speakers still deem preverbal so unacceptable if it expresses the notion of degree. In this case, the respondents critical about the sentences presented were aged 30–41 and three of them were women speaking North American English, so they cannot be regarded as conservative speakers. With deserve, on the other hand, a purely emphatic reading of so is readily available (‘You definitely deserve this job’), which probably renders the sentence acceptable. A follow-up study testing acceptability with a wider variety of verbs (in terms of scalarity and semantic class) might prove helpful to understand speaker intuitions about this particular construction.

With MODAL so V (18), four native speakers (again, three of them aged around forty) agreed that (1) was fine, but that the other two sentences did not seem quite right: ‘My intuitions about (1) are different from (2) and (3). (1) is fine; (2)–(3) are odd.’

(17)

(1) I would so appreciate your help.

(2) He should so call a lawyer.

(3) You could so improve your Spanish if you went abroad.

This impression might have to do with so assuming emphatic meaning in (2) and (3) (‘he should definitely call a lawyer’; ‘you could definitely improve your Spanish if you went abroad’), as opposed to intensifying meaning in (1) (‘I would appreciate your help very much’). Consequently, despite the familiarity with new uses of preverbal so, they seem not to be generally acceptable yet. As a result, some of the respondents suggested that I should have presented the sentences individually, and not in chunks of three. In this respect, it is interesting to see that He so annoys me received comments that it was unacceptable, while I would so appreciate your help seemed to be fine, although both verbs are scalar. In the same vein, You so deserve this job was OK according to some speakers, but He should so call a lawyer was not, even though the meaning of so in both utterances can be interpreted as ‘definitely’. These discrepancies could provide valuable input for further studies on the use of preverbal so in present-day English.

5.2 Intensive vs. emphatic uses of preverbal so (RQ2)

This section addresses the question whether native speakers distinguish between intensifying and emphatic uses of preverbal so. Just under half of the respondents declared that there was a difference in meaning (45 per cent), while roughly a third claimed that there was no difference (38 per cent), and the rest was not sure (17 per cent). As a reminder, the sentences in question were:

(18)

(1) I'm so looking forward to seeing you again.

(2) I so should have called my mother.

(3) I have so wanted to meet you.

(4) I'm so going to find out what happened.

(5) I do so love you.

Following the OED, so has intensifying meaning (‘very much’) in (1), (3) and (5), while it has emphatic meaning (‘definitely’) in (2) and (4). Many respondents gave answers that match this distribution, e.g.:

b. (1) intensifier – I'm very much looking forward to seeing you again.; (2) clarifier – I definitely should have called my mother.; (3) intensifier – I have very much wanted to meet you.; (4) clarifier – I'm definitely going to find out what happened.; (5) intensifier – I do very much love you.

c. 1–3 so could be replaced with really; 4–5 so could be replaced with definitely

d. (1) so = really; (2) = definitely … there's some meaning here I can't capture fully … like an emphasis on calling her mother having been the right move, kind of like ‘I knew I should've…’ or ‘I really regret not calling’; (3) = really; (4) = definitely/totally; (5) = love you so much

Note that really is actually ambiguous because it, too, can function as an intensifier and an emphasiser, and it is interesting to read repeated comments on really as a suitable alternative to so:

e. I think so is used to accentuate the meaning of utterances so it could be swapped for words like ‘really’.

f. I would most likely use ‘really’ in place of ‘so’

Bearing in mind that roughly a third of the respondents declared that the meaning of so was identical in the five sentences listed, this finding could be attributed to the pragmatic function of intensifiers and emphasisers in general (which also explains why ambiguous really seems a good alternative): that of adding force to what is being said. As stated in section 2, there are ambiguous cases where it is not clear whether so assumes intensifying or emphasising meaning, and the distinction might even be irrelevant to some speakers after all; the presence of preverbal so signals additional force, expressing speaker attitude towards what is being said either way, and this might be what is salient to them.

To conclude this discussion, there were also answers that shed an interesting light on the new (viz. emphatic) uses of preverbal so:

g. Very much; So it makes no sense to use it; Very much; Make no sense to use it; Very much

h. 1, 3, and 5 have the same verb-intensifying meaning. 2 and 4 do not modify the main verb and are meaningless to me. If they mean ‘therefore’, they are in the wrong position, but I suspect they aren't meant to mean that.

These two comments, offered by elderly respondents (aged 65 and 80), show that preverbal so with non-scalar verbs is not (yet?) generally acceptable to speakers of English. With non-scalar verbs, it typically has emphatic meaning, reinforcing the truth value of the proposition in question (here: ‘I should have called my mother’; ‘I'm going to find out what happened’). As Stange (Reference Stange2020, submitted) has shown, emphatic uses of so follow intensifying uses historically speaking (see also Athanasiadou Reference Athanasiadou2007 on subjectification). The former have been in regular use for a approximately twenty to thirty years only and are still associated with rather informal spoken language (see also OED Online 2005 Draft Additions, s.v. so, adv. and conj.), while intensifying uses have been attested since Early Modern English times (OED Online, s.v. so, adv. and conj., sense 15).

5.3 Respondent age and gender (RQ3)

In this section, we zoom in on the question whether the speaker's age and/or gender affected the responses given in the survey. As regards gender, the number of speakers per group was too small to make valid claims about potential gender effects (see Table 2). Tentatively speaking, it did not seem to have an effect on the responses given for reported familiarity and active use (the reported ratios were nearly identical for both women and men within a given age group for exemplary BE so going to V, BE so Ving and HAVE so Ved).

Figure 2 shows the six structures most frequently reported as being used actively by the respondents in an apparent-time scenario (oldest speakers to the left of the graph, youngest to the right). Again, the number of speakers per respondent group is fairly small, so any conclusions drawn from the data are tentative at best and require corroboration in follow-up studies with more participants. As the use of GenX so is associated with American English (see the relevant entry in the OED), the reponses for this variety are displayed separately. The dotted line represents all reported active users across all English varieties. Looking at all native speakers, the data invariably show a decline in reported active use in the speakers following Generation X as well as a peak for all structures but one in Generation X. DO so V seems to be the only construction that shows a continuous decrease across the three age groups. Indeed, the sample sentences with emphatic DO (I do so wish you would come back) repeatedly received comments that they sound old-fashioned, extremely polite or very British, which is in line with earlier findings that this syntactic structure is going out of fashion and is mainly used by elderly speakers (Irwin, Reference Irwin, Zanuttini and Horn2014; Stange, Reference Stange2019).

Figure 2. Preverbal so – reported active use

The ratios for reported active uses are higher in American English for four out of the six constructions considered in this section, which could be interpreted as adding substance to the OED's claim that preverbal so is ‘chiefly U.S.’ (s.v. so, adv. and conj., 2005 Draft Additions). In addition, it is only in American English that we find a structure that seems to become more widespread, presenting an exception to the apparent general decline of GenX so: MODAL so V (as in I would so love to see you tonight).

Comment g. mentions the association of preverbal so with informal language, even slang. Considering that this is in line with the OED's classification of the new uses of so, it seems as if it might still carry this stigma (at least for some speakers).

i. I can't think of many uses of ‘so’ before copula + COMP clauses in English, but is used in a main clause for emphasis: ‘you so are’ . . . very common among young people's speech and I would consider slang.

What is more, the next quote shows that some speakers still associate the use of so with young female speakers, especially those speaking in an affected manner. This is something that has been commented on repeatedly in the literature (Kenter et al., Reference Kenter, Lee and McDonald2007; Zwicky, Reference Zwicky2011; Amador–Moreno & Terrazas–Calero, Reference Amador–Moreno and Terrazas–Calero2017; Stange, Reference Stange2020).

j. Big prosody differences between the different ‘so’ meanings, for me.Footnote 10 Also maybe some indexical association with Valley Girl stereotypes in US English?

These comments could offer some explanatory power as to why it has not spread throughout the speech community (reflected in the finding that older and younger speakers report lower ratios of active use than Generation Xers): if it is still associated with rather informal language and still indexes certain social characteristics, it is simply not fit for use across the board.

6. Conclusion and outlook

The comments on the use of preverbal so suggest that it will probably not become the preferred intensifier for verb phrases any time soon. A number of relevant factors contribute to this assumption: First, it seems not to have entirely lost its association with rather informal speech yet and for some respondents, it apparently still indexes the speaker as being naive, affected, female and American (like the blond teenage girl Cher in Clueless, 1995, who uses GenX so several times in the film), while other uses are perceived as sounding extremely old-fashioned (I do so love roses).

Second, the peaks in reported active use for Generation Xers are indicative of preverbal so being disfavoured by younger speakers, maybe because it has already grown stale, needing to be replaced (cf. Bolinger, Reference Bolinger1972: 18) – totally might be the variant preferred by them (I totally understand; see also Beltrama & Staum Casanto, Reference Beltrama and Staum Casanto2017). Future studies could follow up on this aspect and contrast the use of so and totally, also considering associations speakers have with those who use them in non-traditional contexts.

Last, the semantics of the verb apparently have an effect on the acceptability of the utterance in question if it contains preverbal so, which restricts the extent to which it can be used as a verb phrase modifier. Unfortunately, it is not clear what exactly the restrictions are. However, it is a well-known phenomenon in intensifier research that intensifiers gradually expand their collocational range (Partington, Reference Partington, Baker, Francis and Tognini-Bonelli1993), and preverbal so might gain acceptability across a wider variety of semantic contexts in the future.

To date, we do not know how frequent GenX so (still) is because we do not have the data that will tell us the answer. The responses in the survey suggest, however, that it is well and alive, albeit potentially slowly on its way out as post-GenX speakers report lower ratios of active use than Generation Xers.

To conclude, the findings for verb phrase intensification with so parallel the development of intensifiers previously observed for adjective intensification: new contexts of use arise through speakers’ creativity, usually meeting a specific communicative need (here: adding expressive force to the utterance). New contexts of use are often promoted by younger speakers (women in particular; see comments on preverbal so in section 5.3), and are less frequently attested in the speech of older speakers (see apparent-time scenario in Figure 2). New intensifiers steadily increase their collocational range (also shown for preverbal so by Stange, Reference Stange2017, Reference Stange2021) and can proceed from expressing intensity to conveying emphasis (via subjectification which in turn requires delexicalisation and grammaticalisation; see sections 2 and 5.2). After a while, new lexical items become selected as intensifiers or existing intensifiers are used in new contexts, e.g. the innovative uses of so as listed in the OED online 2005 Draft Additions, and the process begins anew. Given that verb intensification has not yet received much attention, it will be worthwhile to explore whether the parallels sketched here also apply to other verb intensifiers. We should so give it a go.

APPENDIX 1:

Questionnaire

Page 1:

Hi,

my name is Ulrike Stange, and I'm a linguist currently investigating the word ‘so’ in sentences like ‘You're so not going to believe this’. Both native and non-native speakers of any variety of English are welcome to participate in this survey. It will take about 5-8 minutes and your input is very much appreciated.

Enjoy!

Page 2:

All data will be collected anonymously. I'm (please select)

0 female

0 male

0 other

0 I'd rather not say

Please tell me how old you are. I'm_years old. Is English your native language?

0 yes

0 no (continue with Page 4)

Page 3:

What variety of English do you speak?

0 North American English

0 British English

0 Irish English

0 Scottish English

0 Welsh English

0 Australian English

0 New Zealand English

0 other:

(continuewith Page 5)

Page 4:

What level is your LISTENING comprehension in English?

B1: Can understand the main points of clear standard input on familiar matters regularly encountered in work, school, leisure, etc.

B2: Can understand the main ideas of complex text on both concrete and abstract topics, including technical discussions in their field of specialization.

C1: Can understand a wide range of demanding, longer clauses, and recognize implicit meaning.

C2: Can understand with ease virtually everything heard. What level is your READING comprehension in English?

B1: Can understand the main points of clear standard input on familiar matters regularly encountered in work, school, leisure, etc.

B2: Can understand the main ideas of complex text on both concrete and abstract topics, including technical discussions in their field of specialization.

C1: Can understand a wide range of demanding, longer clauses, and recognize implicit meaning.

C2: Can understand with ease virtually everything heard.

Page 5:

Please consider the following sentences and state whether you would use them yourself or not. The main concern is the use of ‘so’ in the individual sentences.

(1) You're so going to get fired for this.

(2) We're so going to win this game.

(3) He's so going to marry her.

0 I use sentences like the ones above.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

0 {gap}

(1) She does so love a fancy dinner.

(2) We do so want to see you again.

(3) I do so wish you would come back.

0 I use sentences like the ones above.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

0 {gap}

(1) We have so underestimated you.

(2) I have so enjoyed watching you.

(3) She had so hoped you'd call her.

0 I use sentences like the ones above.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

0 {gap}

(1) We're so looking forward to seeing you again.

(2) I was so hoping you'd be here.

(3) She is so getting into trouble for this.

0 I use sentences like the ones above.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

0 {gap}

(1) I would so appreciate your help.

(2) He should so call a lawyer.

(3) You could so improve your Spanish if you went abroad.

0 I use sentences like the ones above.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

0 {gap}

(1) I'm going to so enjoy my wedding.

(2) He's going to so fire you for this.

(3) You're going to so thank me for this.

0 I use sentences like the ones above.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

0 {gap}

(1) I so love chocolate.

(2) He so annoys me.

(3) You so deserve this job.

0 I use sentences like the ones above.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

0 {gap}

(1) I so would love to see you.

(2) He so should answer the call.

(3) You so could change your mind.

0 I use sentences like the ones above.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

0 {gap}

(1) I so am going to enjoy my wedding.

(2) He so is going to fire you for this.

(3) You so are going to thank me for this.

0 I use sentences like the ones above.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, but I've heard other speakers use them.

0 I don't use sentences like the ones above, and I don't think I have heard other speakers use them either.

0 {gap}

Page 6:

Please consider the following sentences. Does ‘so’ always have the same meaning?

(1) I'm so looking forward to seeing you again.

(2) I so should have called my mother.

(3) I have so wanted to meet you.

(4) I'm so going to find out what happened.

(5) I do so love you.

0 yes (continue with Page 8)

0 no

0 not sure (continue with Page 8)

Page 7:

***You're nearly done!*** Please comment on the different meanings of ‘so’ in the sentences below. What are they?

(1) I'm so looking forward to seeing you again.

(2) I so should have called my mother.

(3) I have so wanted to meet you.

(4) I'm so going to find out what happened.

(5) I do so love you.

Please refer to the individual sentences as (1), (2), etc.

Page 8:

Before you leave: Do you have any additional comments on the uses of ‘so’ as listed in this survey? Or other uses of ‘so’?

Page 9:

You have now completed the survey. Thank you very much for your participation! [ . . . ]

ULRIKE STANGE is a research assistant at the Johannes Gutenberg-Universität in Mainz, Germany, where she instructs prospective teachers of English as a foreign language in the intricacies of English. Her research currently focuses on the use of pseudo-passives in British English and on innovative uses of the intensifier so. She is the author of Emotive Interjections in British English (Benjamins, 2016) and holds a PhD in English linguistics from the Johannes Gutenberg-Universität. Email: [email protected]

ULRIKE STANGE is a research assistant at the Johannes Gutenberg-Universität in Mainz, Germany, where she instructs prospective teachers of English as a foreign language in the intricacies of English. Her research currently focuses on the use of pseudo-passives in British English and on innovative uses of the intensifier so. She is the author of Emotive Interjections in British English (Benjamins, 2016) and holds a PhD in English linguistics from the Johannes Gutenberg-Universität. Email: [email protected]