In her 1917 memoir, A V.A.D. in France, English author Olive Dent recounted her work as a novice volunteer on the frontlines of war in northern France. The account positions Dent and her colleagues as particularly resourceful in their provision of comfort for injured and incapacitated English servicemen. At times, these comforts invoked the senses, including Dent's use of lavender sachets to soothe wounded and dying soldiers, especially those suffering from gas gangrene and other malodourous conditions. In one memorable passage, she recalls one of “her boys” calling out for a sachet in his final moments. The victim of gas gangrene “cried continually ‘Where's my lavender bag, sister? My wound does smell so.’” In response, Dent hung sachets around the soldier, masking the stench of his failing body. “There are dozens of other boys who appreciate the lavender bags,” she observed, “boys who are nauseated by the smell of their wound whilst it is being dressed.” According to Dent, English servicemen valued the smell of lavender and other scents they had enjoyed in prewar life, all as they inched toward death. This functioned, in her account, as a powerful mitigation of the unfamiliar stenches of the Great War.Footnote 1

When she arranged lavender bags around a dying soldier on the western front, Dent brought together disparate sensory experiences coexisting during the Great War: those of the home front and those of global theaters of conflict. These sachets came from English women, girls, and perfumers, who, as part of home front campaigns, made and transported what were called smellies—homemade and commercial objects and substances that invoked supposedly traditional British scents. For some women, this meant the collection and distribution of homemade lavender and verbena bags as an allegedly effective—and practical—means of aiding those injured at the front. For others, like commercial perfumers, it meant the production of perfumed commodities like lavender water and eau de Cologne for transport to troops, and especially officers, dispatched overseas. Ill and wounded soldiers reportedly appreciated these gifts as alleged fumigants and sources of comfort. Accounts vary, but one particularly active supporter claimed to have sent some sixteen thousand muslin bags to French hospitals in 1917 and another twenty-seven thousand in 1918.Footnote 2

Undergirding the creation, distribution, and reception of smellies were conceptions of nationalism, race, class, and gender that circulated in wartime England. More specifically, narrow and exclusionary forms of English national identity were central to definitions of what were classified by supporters as British scents.Footnote 3 White middle- and upper-class girls and women, in conjunction with perfumers, also envisioned very particular recipients of their olfactory gifts: white, English-born servicemen who yearned for the romanticized smells of a rural England—not those of the urban and colonial environs that so many actually called home. Conceptions of Englishness as whiteness further defined the gifts as means to transport troops back to modes of ordered domesticity in the form of an imagined white, English home. Such evocations of a national home via scent allowed white servicemen to transcend dominant expectations of martial masculinity, all while blurring divisions between the domestic and the public, peacetime and conflict, before and after. Attempts to establish national smellscapes thus had gendered implications, in the ways that supporters maintained their power to reorganize gendered disjunctures between home and away—despite criticisms of perfumed gifts as unnecessary and even potentially degenerate or effeminizing wartime luxuries. Imaginings of a white, English home life subsequently fueled the production of items that took on new national resonances in the wartime context: lavender bags, lavender bundles, verbena bags, eau de Cologne, and commercially produced lavender water.

In exploring volunteers’ attempts to define and to domesticate the disparate smellscapes that often demarcated wartime experiences, I draw on recent developments in the history of smell to offer new perspectives on constructions of gender, race, and national identity in responses to the Great War. Since the publication of Alain Corbin's germinal work, The Foul and the Fragrant, scholars have increasingly moved beyond the visual register to read sources in new ways by taking seriously the linkages between smell, power, and the social order. In doing so, Corbin argues, we upset the “logic of the systems of images from which . . . history has been generated” and expand the dynamic register of approaches available to historians.Footnote 4 In the past twenty years, for the Anglo world, historians of early modern Britain and the modern United States have increasingly taken up these imperatives to productive ends. Historians studying early modern Britain have interrogated the mobilization of smell as a means of refashioning and reinforcing the domestic realm during plagues or defining race and ethnicity in eighteenth-century intellectual discourses.Footnote 5 Historians of the United States have charted the deployment of scent to delineate and target poverty-stricken urban slums in the mid-nineteenth century or uphold racialized differences and enslaved labor in the nation's south.Footnote 6 In doing so, they advance sophisticated new strategies for conceptualizing historical experience, not to mention documenting historical relations of power and difference. In some instances, such studies include attention to smellscapes, the olfactory counterpoint to visual landscapes. These “olfactory geographies” are ephemeral in nature, often “spatially ordered or place-related,”Footnote 7 and “accommodating both episodic (foregrounded or time limited) and involuntary (background) odours.”Footnote 8 For those sending scents from England in wartime, smellscapes functioned in both imagined and material ways, as conditions that could be manipulated, revised, and transformed via dominant conceptions of gender, race, class, and Englishness. These perceptions stood in stark contrast to some accounts from actors at the front, who experienced war-related smellscapes as unrelenting, unrecognizable, and beyond their control.

Methodologies from sensory history, including the concept of smellscapes, allow a new type of engagement with scholarship on both the complex relationships linking gendered life at home and the front and the roles of voluntary campaigns in the construction of national and racial identities.Footnote 9 For the former, scholars have highlighted non-military voluntary initiatives—many spearheaded by women—to challenge the historical devaluation of feminized undertakings and assert that women's home front campaigns were important features of total war.Footnote 10 For the latter, Steve Marti has shown how volunteers in Britain's white settler colonies who had the power, time, and resources developed what Marti terms “monopolies in the economy of sacrifice.” Voluntary mobilization reified existing—and inequitable—systems of “class, gender, race, and indigeneity” and perpetuated “colonial structures in Dominion society.”Footnote 11 I build on this work via sensory history, asking how the construction of so-called British smells became a mode of mobilization for those at home, all while fomenting restrictive and exclusionary models of national identity. Volunteers and perfumers used the imaginative powers of smell as a prompter of collective memory and source of deeply localized modes of comfort, celebrating the power of traditional scents to challenge narratives of fragmentation and disillusionment. In doing so, home front efforts obscured the social, racial, and material realities of war, mobilizing the symbolic potential of perfumed items to muster a fictitious version of English life that could be resumed after the conflict.Footnote 12 What resulted was a profoundly limited definition of British smells and, by extension, their idealized British recipients: white, English-born troops from the rural working classes (in the case of scented sachets) and urbane upper-class officers (in the case of eau de Cologne). Imagined recipients of British scents did not include vast numbers of servicemen of color fighting for Britain, nor those whose memories of home unfolded in overcrowded courts and alleys rather than a sentimentalized (and disappearing) English countryside.Footnote 13

In this way, the scents were designed to offer comfort and relief to very select constituencies of frontline servicemen. Often this was in the face of devastating material conditions, and accounts of gifts’ production and reception reveal fractures—and failures—in the deployment of British smells to order the disordered smellscapes of war. Smell-based campaigns produced “tensions between representation and materiality,” something that has garnered considerable attention in literary studies of the Great War.Footnote 14 They also extended, in the case of smellies, to material culture and the senses. An extreme and visceral dichotomy separated the olfactory comforts of an unspoiled (and fictitious) English home from sensory experiences at the front, which were often framed, via disgust, as a type of bodily violation. These tensions play out in conflicting accounts of homebound voluntary efforts and frontline reports. I also replicate and vivify these tensions in the deliberately bifurcated organization of this essay, which opens with the imagined possibilities of scents at home as constructed by volunteers and commercial perfumers and then moves to the disordered smellscapes of overseas theaters of war.

Rallying for the Cause

From the outbreak of war in August 1914, Britons developed many strategies to support the war effort. These included the mobilization of private groups and individuals as the principal providers of what were called “soldier comforts”: supplying commercial and handcrafted goods, such as tobacco, soap, scarves, and socks, to supplement standard military-issue items.Footnote 15 By the summer of 1915, this avalanche of private contributions led to what Peter Grant has dubbed the “comforts crisis,” forcing the government to tackle concerns over duplications and imbalances in supply and demand.Footnote 16 Specifically, the office of Director General of Voluntary Organizations was created in October 1915 to oversee and coordinate benevolent initiatives. Declaring that he had no intention of interfering in the daily management of voluntary organizations, appointee Sir Edward Ward enacted broad measures that monitored the safe transport and equitable distribution of goods from the supply end.Footnote 17 Operating under this umbrella organization, groups continued a variety of campaigns—for knitwear, eggs, hot-water bottles, sphagnum moss—as part of the general mobilization of an estimated 2.4 million volunteers over the course of the war.Footnote 18 Such comforts, alongside personalized gifts and parcels, all “the stuff of home itself,” served personal and patriotic functions as symbols of domestic support and fortitude.Footnote 19

In keeping with the emphasis on home, voluntary campaigns were often deeply localized and designed to support very specific groups as a reflection of community interests and investments. This localization of efforts meant that robust voluntary schemes emerged across Britain, its settler colonies or dominions, and colonized regions. In Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, voluntary contributions proved crucial to the dominions’ buttressing of the war effort.Footnote 20 In India, high-ranking individuals, including the begum of Bhopal and the thakur of Bagli, provided soldiers with religious texts like the Qur'an, cigarettes, clothing, and chocolate.Footnote 21 But the rise of localized initiatives came at a cost, and voluntary mobilization could be, in the words of Marti, “selective, exclusive, and competitive.”Footnote 22 That exclusivity is evident in those campaigns purporting to support so-called British causes. While seemingly extending to all those fighting under the Union Jack, English campaigns reflected colonial and racialized hierarchies in their privileging of white servicemen born in the British Isles over millions of British and colonial troops of color, who were less often on the receiving end of English efforts. This comes to the fore in the experiences of some members of the Royal Engineers Coloured Section of the Mesopotamia Expeditionary Force. As Roy Costello has revealed, a division sent a letter of grievance to the Colonial Office in January 1918 that described, in part, how members “knows that lofts of goods gifts been always sent out but we are not receiving anything [sic].”Footnote 23

Race and its role in the distribution of comforts were rendered invisible and did not explicitly feature in most coverage of English voluntary efforts.Footnote 24 Instead, public debates over gifts’ private and political functions manifested in classed forms, in tensions over comforts as luxuries versus necessities. In the frenzied early months of voluntary mobilization, member of Parliament Harold Elverston requested that “the public supply our men at the front with what may really be termed luxuries, but do not let them depend upon private generosity for what are real necessities.”Footnote 25 At the heart of this distinction was determining state responsibility to provide certain items. For instance, scarves and balaclavas were initially classified as luxuries and left out of official issue, to the consternation of some.Footnote 26 But other goods, including those related to scent and perfumery, were unambiguous in status and definitively situated as a soldier luxury from the outbreak of war.

Scent's designation as a luxury rather than a necessity did not stop people from sending lavender bags to the front, and especially its field hospitals, as part of a range of benevolent campaigns taking place across Britain. In focusing on scented items, volunteers and commercial perfumers defied perfumery's elite associations. They also rejected preexisting beliefs around smell and class, which included the alleged malodorousness of the working classes.Footnote 27 Instead, they relied on familiar repertoires of smell made popular long before the outbreak of war, turning on nationalist associations of natural goods like lavender to offer soothing scents to all classes of servicemen. British claims to lavender as a national smell belied similar contentions among the French, the principal suppliers of raw materials to the global perfumery trades. Yet, despite French ascendency, strong cultural associations around English lavender endured through the modern period, so much so that it was reportedly “the envy” of Parisian perfumers and distillers.Footnote 28 English lavender was especially emblematic of an idealized rural life and its traditions, which allegedly imbued it with cross-class appeal since it could be procured naturally at no cost or bottled and sold for profit. From the mid-nineteenth century, a select group of urban perfumers emphasized this fact, publicizing their reliance on local stills to align with what they characterized as timeless English values.Footnote 29 Lavender producers at Mitcham in Surrey and Hitchin in Hertfordshire maintained an important economic but also symbolic presence, providing traditional scented items for British consumers, who included, from August 1914, a cross-class constituency of servicemen.Footnote 30

Lavender and other scented items transported overseas were not always commercially manufactured and took multiple forms, often reflecting the geographic situation and economic status of its senders. Some volunteers, including white women and girls, collected lavender in its raw form and used it to craft handmade sachets said to be “best made [with] white spotted muslin, about 5in. square, tied with a bit of coloured ribbon, so that they look fresh and dainty.”Footnote 31 Makers followed prewar conventions in fashioning square pillows or tying a bag around “the heads of the flowers” with “wide ribbons of soft lavender blue,” leaving the stalks as a handle.Footnote 32 Across Britain, girls like eleven-year-old Doris Bishop of Hull engaged in the patriotic undertaking alongside schoolmates, neighbors, and friends.Footnote 33 Adult women also took up the work, thereby transforming from targeted consumers of popular lavender-themed perfumery to producers of soldier luxuries, reviving older uses of raw lavender for a wartime context.Footnote 34 This included its provision to all classes of servicemen, who allegedly appreciated the natural smells of home regardless of their social standing. Press accounts supported this work, promoting lavender sales, fairs, and “Lavender Days” in wartime news.Footnote 35 Lavender-themed events took place across Britain, from the south to the north, in deeply localized campaigns. In August 1915, women in Salisbury sold more than eight hundred bags of “sweet-smelling lavender” for 2d. to 5s., with all proceeds—over £30—going to the Red Cross.Footnote 36 An August 1917 event in Brechin raised £43 14s. 7d. for “the comforts of local soldiers,”Footnote 37 while a Red Cross Day in London in October 1917 included the donation of an entire field of lavender—a small piece of England itself—and incited “a burst of activity in the fashioning of many small muslin bags to be filled and neatly bound with ribbon.”Footnote 38

The sale of sachets to bolster funds was not the only means to support the war effort through lavender, and volunteers also oversaw the item's transportation to the front. From mid-1915, elite and middle-class white women collected and distributed bags to local wartime depots and overseas field hospitals. Taking up revived narratives about the hygienic and health effects of soothing smells, proponents argued for providing comfort to white soldiers via scented items, something that the soldiers themselves allegedly desired.Footnote 39 Writing to the Daily Mail in July 1915, correspondent Daphne Bax reported, “Soldiers in hospital have told me how delighted they were when people bring them ‘smellies’—i.e., something to smell. It scarcely requires imagination to realize the nauseating effect of the necessary disinfectant odors in a surgical ward.” It was a simple initiative, she continued, and one that could occur regardless of class or geographic situation. “It is so small and yet so gracious, so sensitive a gift to our ‘men of blood and iron’ now lying with the bold blood drained from them and the nerves of steel shattered into splinters.”Footnote 40 Bax promoted the scheme by juxtaposing scented gifts with the physical and mental damage wrought by war, suggesting that smell's allegedly restorative qualities could be mobilized to counter loss and fragmentation. “Imagine,” exclaimed supporter Maud Dyer in a subsequent appeal, “the thoughts and visions a bag of lavender under the pillow may awaken!”Footnote 41

Print appeals from such female correspondents were seemingly effective. Given the private nature of many initiatives, it is impossible to determine precise numbers of scented items transported to overseas depots and field hospitals. Testimonies of correspondents to the London Times and Daily Mail suggest the count for sachets sent to the front were in the hundreds of thousands.Footnote 42 In 1917, for example, the Bournemouth branch of the Bible Flower Mission sent thirty-five thousand bags to hospitals in Rouen.Footnote 43 Shipments served not only the western front but were reportedly sent to white, British-born servicemen in Malta, Egypt, and Mesopotamia, and to those in “hospital ships” and “naval and military hospitals at home.”Footnote 44 By July 1918, elite lavender enthusiast Marion Lee claimed to have sent over twenty-thousand bags to Alexandria with hopes of sending another thirty thousand, “as the suffering men value them greatly.”Footnote 45 Bags solicited by Mrs. Godfrey Williams in London were sent to the British Red Cross on the Pall Mall and posted to a Mrs. Payne at the Alexandria depot.Footnote 46 Local philanthropic organizations and managers of wartime depots across Britain encouraged these donations, as evidenced in reports from the British Women's Patriotic League, the Victoria League, and various war hospital supply depots.Footnote 47 Voluntary networks crisscrossed Britain, as white women and girls sought to offer comfort by transforming smellscapes for a cross section of white troops defending national interests overseas.

Selling Scent in Wartime

Women volunteers producing homemade sachets were not the only ones attempting to marshal smell in service of the war effort. Commercial perfumers also engaged in the movement of scented commodities to overseas theaters of war, advancing schemes that bolstered the classed, gendered, raced, and patriotic meanings—and alleged desirability—of scent in a transformed consumer landscape. In the early months of the conflict, perfumery's irrefutable standing as a luxury, before but especially during the war, concerned Britain's commercial perfumers and distillers, who labored to secure the ongoing sales of their product at home and via the movement of scent across the Channel. Perfumers clearly understood that during wartime elite luxury goods would face scrutiny and renunciation from government trade boards and consumers alike. Compounding this threat were popular critiques targeting consumption and leisure as sources of corruption and emasculation, themes that Nicoletta Gullace argues ran “through the language of recruiting at the beginning of the war.”Footnote 48 Such challenges propelled the industry into action, as manufacturers joined white women and girls in renewing and revising understandings of the allegedly cross-class, cross-gender, but singularly raced values of “British” scents.

Trade journals reveal shifting anxieties over the course of the conflict, as British perfumers and distillers navigated the tides of a wartime economy that actively discouraged luxury consumption.Footnote 49 In the initial months of conflict, British perfumers and distillers were relieved to note an uptick in sales of essential oils and perfumed goods. This reflected, in part, the ongoing breadth of the market, buoyed by its unisex base. Historically, cologne had been produced and marketed for both male and female consumers via relatively gender-neutral advertising.Footnote 50 While certain beauty markets and goods were becoming increasingly feminized through the early twentieth century, eau de Cologne, lavender water, and other grooming items retained much of their cross-gender appeal. As early as October 1914, however, trade commentators observed classed shifts as “well-to-do users are fighting shy of the more expensive lives, [and] they are showing more favor towards the less costly articles, the demand for which has expanded notably.” Perfumers subsequently pivoted “greater attention to the preparation and marketing of attractively got-up moderately priced bouquets.”Footnote 51 While appeals to frugal consumers may have temporarily sustained the industry, by February 1917 it faced another blow via proposed import restrictions.Footnote 52 In early 1918, industry fears became even more pressing when government concerns crystallized in the form of a luxury tax, spearheaded by the chancellor of the Exchequer, Bonar Law. While the tax never materialized—the war wound down before its enactment—trade debates foregrounded the very real threat of perfumery's classification as a luxury.Footnote 53 Throughout the war, trade insiders insisted the opposite, claiming “there are very substantial grounds for maintaining [perfumery's] full production in the interests of health and the well-being of the people—not to mention the national revenue.”Footnote 54

Major firms reacted accordingly and attempted to transform perfumery from an elite luxury into a wartime necessity, for white women and men of all classes, via elaborate marketing schemes.Footnote 55 These moves proved especially important in the wake of ongoing challenges facing the commercial perfumery industry, including continental competition. British perfumers found that consumer preference for French and German wares continued despite hostilities. This demanded an “educational campaign” for British consumers, declared one anonymous perfumer, who complained to the Times, “the majority of shoppers do not know the origin of much that they buy.” In the case of goods like eau de Cologne, however, shoppers clearly understood the item's source, a fact that spoke not to consumer ignorance but preference. “I suppose that the British think that a good Cologne can only be made abroad—notably in Cologne,” conceded the perfumer. Outstanding consumer desires for foreign wares, combined with “the hardships experienced by British perfumery manufacturers owing to the high cost of raw materials and labour,” exacerbated challenges facing Britain's wartime perfumery industry.Footnote 56

Perfumery marketing campaigns subsequently promoted the patriotic act of buying British scent for both women and men, while emphasizing the enemy origins of some popular perfumery manufactures. The campaigns pushed back against commentary linking luxury consumption with elite decadence and lack of utility. Instead, they alleged that perfumed goods functioned as visceral means for white women and men to communicate alignment with the national wartime effort—by smelling of what was called “pure” British smells that derived from pure British sources. Select perfumery firms had mobilized nationalist themes in advertising campaigns from the late nineteenth century, but this emphasis dramatically expanded following the outbreak of war.Footnote 57 In autumn 1914, for example, London-based perfumer John Gosnell & Co. developed gender-neutral marketing campaigns that promoted a particular type of patriotic performance: the act of smelling British. The advertisements foregrounded those scents traditionally linked with specifically British olfactory trends. In particular, lavender and eau de Cologne, proudly labeled as “British Made,” dominated print ads that simultaneously solicited donations for the British Red Cross. In promoting the renewed patriotism of traditional scents, Gosnell played on the fervor of war to enhance sales, developing a type of gender-neutral citizen-consumer who both smelled and acted the part of a patriotic Brit.

Yet perfumers’ attempts to develop stable national smellscapes were contradicted by the realities of perfumery production, the industry, and the ideological underpinnings of their campaigns. The promotion of British scents, in fact, reflected imagined ideas of English whiteness, nationalism, and pastoralism. Such conceptions turned on scenes from the south of England and its bucolic lavender fields rather than the perfumery trade's actual concentration in dense urban thoroughfares in the heart of industrial London.Footnote 58 Moreover, the majority of British perfumery's raw materials—including lavender—derived from Europe, and specifically France, with additional ingredients transported from colonized regions.Footnote 59 This is evident in advertising for the Jersey-based firm Luce, whose “English eau-de-Cologne” included “no less than 40 different ingredients . . . some of them fearfully expensive—such as attar of roses, the pod of musk deer, and many other things.”Footnote 60 These materials originated in areas around the Ottoman Empire and across colonized areas of South Asia, where they would have been harvested by colonial laborers.Footnote 61 Commercial perfumers’ emphasis on “national” scents thus obfuscated the industry's deeply transnational and colonial debts.Footnote 62

It was not only the origin of ingredients that undermined the Englishness of British perfumery: the history of one of Britain's most popular fragrances also defied nationalist claims. From the late nineteenth century, leading British perfumery firms enthusiastically promoted their “British made” versions of eau de Cologne via claims that obscured the fragrance's international standing.Footnote 63 Eau de Cologne is most often attributed to a Cologne-based perfumer of Italian descent, Johann Maria Farina, who allegedly first produced the scent in 1709.Footnote 64 The Farina firm closely guarded its recipe, but imitations soon emerged, featuring blends of neroli, citrus, and bergamot. These counterfeits included a number of lines formulated by British firms, and throughout the nineteenth century, “British-made” eau de Cologne was sold in the nation's leading department stores and chemists’ shops.Footnote 65 Nationalism was a defining feature of many of these brands through the early twentieth century, a trend that gained even greater purchase with newfound enmity to Germany.Footnote 66 By December 1914, Yardley advertisements prominently claimed the scent's composition was not German in origin but French.Footnote 67 Meanwhile, Grossmith, Luce, Leicestershire-based Zenobia, and even Boots the chemists capitalized on consumers’ patriotism by bringing to their attention “The Truth about Eau de Cologne”—that a fine product could be crafted just as well with British ingredients in a British setting (see figure 1).Footnote 68 Noted an advertorial for Grossmith, “This has provided an exceptional opportunity for English perfumers to establish a reputation for British brands.”Footnote 69 But in order to harness “British” smells for a wartime market, perfumers had to conceal the internationalism of eau de Cologne's production and history.

Figure 1 Advertisement for Boots the Chemists’ “British Eau-de-Cologne for British People,” Times (London), 21 October 1914, 6. Courtesy British Library Board, Shelfmark NRMMLD1.

In addition to boosting the national symbolic import of perfumed goods, advertisers promoted the medicinal and emotional properties of traditional British scents as a means to comfort all classes of consumers, at home and away. One trade journal declared, “To glibly pronounce all perfumery as ‘luxuries’ is, it is averred, to shut one's eyes to the substantial utility of many of them as remedies, prophylactics, and health adjuvants.”Footnote 70 In their efforts to sustain the industry, perfumers and distillers amplified the alleged health properties that had been central to understandings of early modern and nineteenth-century scent, including relationships to miasmatic theories of disease. During the eighteenth century, notes William Tullett, “An odour could . . . be both an aromatic (or indeed a medicine) and a perfume depending on its context.”Footnote 71 These traditional uses were reanimated in the wartime context, and advertising copy declared perfumes as “confidently recommended for use in the sick-room,” claiming there was nothing like it “for charming away headache and bracing fatigued and relaxed nerves.” Here gender and race came to the fore, as these purported health properties extended to white male and female customers, as both recipients and providers of relief. Companies like London's Crown Perfumery advertised their lavender range as a “reviving and keenly stimulating remedy” for lightheadedness or “nervous headaches” experienced by white women in wartime Britain.Footnote 72 From December 1914, firms like Gosnell and Zenobia advertised their eau de Cologne and “Real Old English Lavender Water” as “very delightful British perfumes” that were “refreshing and welcome gifts to the wounded and other invalids” (see figure 2).Footnote 73 Meanwhile, the French firm Courvoisier argued in its English-language campaigns that perfume was appreciated “nowhere more so than in the fighting line, for perfume, besides being so refreshing, is also an active disinfectant.”Footnote 74

Figure 2 Advertisement for Zenobia Eau-de-Cologne, Bystander (London), 15 March 1916, 499. Courtesy British Library Board, Shelfmark ZC.9.d.560: 1916.

Not only the ill or infirm but also healthy white soldiers emerged as a new consumer group as intended recipients of gifts of scents from women at home. Trade publications avidly pursued the new market of combatant-consumer, advocating in the face of anti-luxury lobbying for the dissemination of perfumed goods to soldiers. While the cost of these items would have been prohibitive for many, advertising copy ignored classed realities and targeted white servicemen as an imagined collective. “[O]ur fighting men,” exclaimed one trade editorial, “would they be encouraged if deprived of what some people call ‘superfluous luxuries’ in the shape of a perfumed shaving soap or a brilliantine for the hair to give them at least some respite from the unaccustomed dirt in the trenches?”Footnote 75 Firms took up the call, and in the first holiday season, Gosnell launched its “special ‘Soldier's Toilet Box,’” a 5 x 3.5–inch tin case featuring a “shaving stick, toilet soap, tooth brush, tooth paste, and mirror.” Advertised primarily via a subscription campaign in The Queen, the box functioned as a means for “patriotic ladies” to support the war effort by providing homely comforts to those on the front lines.Footnote 76 Comforting (and purifying) grooming products purportedly strengthened connections between loved ones, and advertisements envisioned heroic, white soldier-figures enjoying these pleasures, with their attendant salutary effects. In April 1915, The Sketch's shopping columnist summed up just some of the ways that traditional scented items allegedly affected users at the front: “There are some typically English things which bring our much-loved home before our eyes even if our people are in the desert, on the mountain-top, in the trenches, or watching and waiting in the big boats. One of them is the scent of English violets, which reproduces in brain-waves the charm of English lanes in springtime; another is English lavender, which conjures up the autumn and late summer joys of our land.”Footnote 77 A whiff of violet or lavender goods, the columnist maintained, transported troops away from theaters of war to the bucolic fields and lanes of England. It then proceeded to hawk London's latest lines of soap, brilliantine, shaving cream, and perfume.

In invoking time-honored smells mobilized in the name of patriotism, commercial perfumers did not purport to offer new wartime configurations of gender, class, or race but instead promoted a bolstering of older, fictionalized usages and consumption patterns of traditional scents. Smell, a highly personal trait, was a means to invoke an allegedly simpler time characterized by a white, English domesticity that was accessible in spite of class or gender. Single-note commercial perfumes like lavender and violet were long established in the British olfactory repertoire, and their renewed purchase now symbolized an embrace of allegedly shared sensory traditions. Meanwhile, manufactures like eau de Cologne purportedly functioned to comfort white women at home and men at the front, linking them together via shared sensory experiences. Scent's associations with health, place, and memory enhanced its nostalgic qualities, allegedly connecting certain constituencies across time and space in a collective experience. By returning to the scents of their youth—the traditional scents of an idealized prewar nation—white English consumers could signal their adherence to a shared (and fictional) national identity. Such visions ignored the material realities of large numbers of British servicepeople, given the urban, industrial, and working-class backgrounds of many wartime participants, some of whom would not have been privy to the olfactory pleasures of rapidly disappearing agrarian settings, let alone costly scented goods. Neither did these schemes include racialized British soldiers nor millions of people of color from colonized regions, including some 1,440,437 troops and laborers from India alone.Footnote 78 Instead, in envisaging a pre- and postwar Britain, volunteers and commercial perfumers relied on English pastoral associations as an imaginative and sensorial means of connecting white servicemen—as recipients and consumers—to a mythologized time and place.Footnote 79

What linked all these messages aimed at wartime consumer groups was an emphasis on the so-called purity, efficacy, and Britishness of certain perfumed goods. In the wake of global conflict, Luce, Gosnell, Boots, and other firms reasserted ideas about patriotism, tradition, and duty to encourage purchase of their goods. Notions of company history and symbolic signifiers of nationalism came to the fore as central to wartime morale and trade. In this way, British perfumers circulated messages similar to those of the white women and girls who were cultivating lavender: that scents were traditionally healing, with medicinal and soothing properties that turned on deeply localized English affinities and customs. These aligned messages—shared by philanthropic groups and the perfume industry—attempted to inscribe new wartime value onto scent by reverting to old traditions, as both groups labored to establish these goods as cross-class necessities rather than decadent luxuries. Despite these efforts, the utility of scented items came under exacting scrutiny in the context of disorienting and unfamiliar new smellscapes at the front.

The Smells of War

In print appeals, philanthropic supporters and commercial providers mobilized nationalist tropes to revise perfumery's decadent luxury status and assert its usefulness at the front. Yet despite collection drives, marketing campaigns, and positive press coverage, questions circulated over scented goods’ utility. It remains unclear whether recipients themselves appreciated scent as desirable examples of so-called soldier luxuries or whether this was largely a message advanced by enthusiastic volunteers, commercial perfumers, and a circumscribed wartime press. The benefits of perfumery hinged on civilian envisioning of white English soldiers’ wartime experiences that conceivably tempered the horrors—and stench—of war. Philanthropic campaigns and wartime advertising aimed at white women advanced a mediated view of the front as a space that could be domesticated, if not lightly perfumed.Footnote 80 This imaginary failed to reflect the lived realities of those engaged at various theaters of war who were privy to a range of new and disorienting smells. In many accounts, these smells defied categorization via language or other frameworks of understanding such as gender or class, which is notably muted in descriptions of wartime odors. They nonetheless remained central frameworks through which historical actors experienced, ordered, and interpreted their frontline service, and the absence of gendered and classed associations in most accounts of smells at the front is thus telling of their inscrutable nature.

In recollections of war, descriptions of unfamiliar and distressing smells often function as discursive strategies for vivifying the horrors of combat experience; as one scholar of smell cynically observes, “No war novel is complete without reference to the sweet stench of bloated human remains.”Footnote 81 Others, like Santanu Das, have offered more sensitive, comprehensive analyses of sensory experiences of the Great War, detailing the relationship between the senses and industrial warfare's dissolution of corporeal and subjective selves, all while emphasizing the deep sensorial contrasts delineating home from trench life.Footnote 82 A number of sensory assaults characterized what Matthew Leonard terms “the subterranean sensorium.” This included smells that were destabilizing, unfamiliar, and thus frequent elements in descriptions of war typically dominated by white, British interlocutors.Footnote 83 Most distressing—and common—was the stench of death. What one officer termed “that old smell of slaughter” permeated the western front and the sun-drenched battlefields of Gallipoli and beyond.Footnote 84 Officers’ diaries cite the mysterious reek of iron-lined trenches, attributed in part to layers of detritus, including human remains, left by previous occupants.Footnote 85 Other notable smells came from historic graveyards disturbed by shelling (one particularly gruesome account describes the upturning of remains dating to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870). Rotting trenches, sick horses, latrines, garbage heaps, dead bodies, or even one's own body all contributed to what one soldier described as the “pungent sickly smell,” the “perfectly nauseating stench” of war.Footnote 86

Other smells had the added ominous quality of being harbingers of debility if not death. Soldiers were educated before deployment on gas's effects and ways to avoid it, yet this was insufficient to prepare all those at the front for gas attacks.Footnote 87 Interviewed in 1973, L. J. Hewitt, a private in the Leicestershire Regiment, described a progression of sensory experiences upon being gassed: “If you went in the—well, not if you went in— you went in the line, and your buttons, if you never had your gasmask on, your buttons were all green. That's when you come out. Well, matter of fact, soon as you got in it was green. So that's your gas. And that's your smell of gas. So what with the smell of gas, the smell of gunpowder, explosions, the . . . the cordite in there and so forth, and the corpses, well that was a smell not out of this world.”Footnote 88 Hewitt's account opens with a hedging of masculine heroism, via its conditional framing, before his subsequent correction: not if, but went. Following this revision, his first experience of danger was a visual cue—the discoloration of his uniform buttons—before he detected stenches emanating in rapid succession from various technologies of war and, eventually, death itself. For Hewitt and others, the confluence of technological, environmental, and bodily odors created something wholly new, apart from his lived sensorial experiences.

Indeed, a striking feature in descriptions of wartime smellscapes was their complete unfamiliarity. But other accounts from presumably white, English-born soldiers frame this newness in the context of racialized difference, mobilizing the language of foreign “otherness” to target local people and practices as sources of sensory difference.Footnote 89 Olfactory codes have long functioned as a means to reify alleged differences between dominant and marginalized groups, with the former mobilizing smell to assert power over the latter. In colonial contexts, this frequently meant the characterization of local actors as “malodorous,” as colonizers reconstituted unfamiliar smells as “different,” “other,” and “foreign.”Footnote 90 Thus one pseudonymous soldier, using the name Cassius, waylaid in Egypt in 1918 en route to Gallipoli, describes how, upon arrival, he was “assailed by that pronounced but indescribable smell of the East,” “including garlic and onions,” along with “the acrid smell of the smoke from our tiny brushwood fires and the stench of shallow-buried corpses.” In this moment, the author conflates local cooking smells with those of war, aligning smells of otherness with those of death and decay. He goes on to juxtapose the “distinctive” odors of camels and dead cavalry horses to the scents of his native Britain, concluding, “Each man's nose is eager for the incomparable smell of home.”Footnote 91 Although the author's referents to smell are not characterized as wholly unfamiliar, the novel smellscapes are interpreted within colonial frameworks and specifically via racist configurations of a fixed “Eastern smell”Footnote 92—all collapsed under a homogenizing umbrella of otherness.Footnote 93

Most often, accounts described stenches that could not be linked to any existing or imagined smellscape, otherworldly types of smells that transcended characterization as foreign. The diary of white English Captain Lawrence Gameson, for example, evocatively captures unsettling and entirely new sensory experiences. Moving through Buzancy in northern France in August 1918, Gameson passed through farmers’ fields littered with uncleared dead. His written account offers a vivid rendering capturing the horror of his experience via its attendant stench: “Corpses were ripening rapidly in their humidly hot resting place. On that close windless day the evil-sweet stink oozed, so to say, into one's central nervous system and brain. Similar sensory stimuli were by no means unfamiliar, yet the stench of corruption hovering above that cornfield cannot be classified by any standards known to me. Although certainly not put out in this way easily, it was several weeks before I could again eat cheese; cheese suggested the smell.” As Gameson describes a smell unlike any he had ever encountered, in the same breath, he links it to a common food, an association that reflects the disorienting nature of his experience. His attempts to connect the stench to something familiar as cheese failed to classify fully this particular “stench of corruption.” The smell, even as it permeated his “central nervous system” and became a part of him, was beyond definitive description.Footnote 94 Such inadequacies of language or familiar points of reference reflected more general trends in soldiers’ inabilities to aptly express experiences of the war, through gendered frameworks or otherwise.Footnote 95

The notion of smells becoming a part of a serviceman—and transforming his relationship to the self at both the front and at home—appears across postwar accounts, including those in the field of wartime psychology, as produced by a cohort of leading medical experts. Links between distressing smellscapes and psychological trauma figure in postwar casebooks of “soldiers’ neuroses,” describing the lingering effects of smells even after the return home. There was some medical debate, however, and French physicians like Gustave Roussy and Jean Jacques Lhermitte claimed that changes in smell or taste were “rare following shock or trauma in war.”Footnote 96 An examination of the senses was nonetheless central to diagnosis and treatment of the new condition dubbed shell shock, with physicians periodically noting instances of anosmia or worse among patients. This comes to the fore in physician H. C. Marr's comprehensive guide to “Mental Case-Taking” for instances of psychosis, which included tests with clove and camphor for increased (hyperosmia), absent (anosmia), and lessened (hyposmia) senses of smell.Footnote 97

While some patients experienced loss of smell, a few shell-shock sufferers experienced the opposite: a hyperacuity of scent, both real and remembered, that triggered episodes, in some cases to the point of incapacitation. This is evident in one postwar collection of some 589 instances of shell shock, which includes a case from Wiltshire in June 1916. Under the heading of “Olfactory Dreams: Hysterical Vomiting,” physician-authors described the case of an infantry lieutenant whose tasks included overseeing the burial of “many decomposing bodies.” In the aftermath of this, the lieutenant experienced “hysterical hallucinations” that made him vomit everything he ate, which he attributed to being “haunted ‘by that awful smell of the dead.’”Footnote 98 In another well-known case from February 1918, the famed neurologist and psychiatrist W. H. R. Rivers treated an officer who was “flung by shell explosion so that his face struck the ruptured and distended abdomen of a dead German. The officer did not immediately lose consciousness and got distinct impressions of taste and smell and an idea of their source.” For days following the incident, he was “haunted by taste and smell images,” which again induced frequent vomiting. When the officer consulted with Rivers, a leading expert in wartime “psycho-neuroses,” the physician deployed one of his standard psychoanalytical strategies: to “find a redeeming feature in the experience, upon which the patient might concentrate.” This failed, however, when Rivers admitted he could identify no reparative elements in this wartime trauma. The officer was subsequently discharged from the military and advised to “seek the conditions” that gave him “slight relief,” although such conditions were not specified.Footnote 99

In each of these cases, patients experienced the “loss of control” that typically characterized accounts of shell shock in wartime and postwar literature. As Jessica Meyer has argued, this framing meant that shell-shock victims diverged from conventional expectations of martial masculinity circulating in this period, particularly in relation to self-control as a sign of character and maturity.Footnote 100 In the case of olfactory patients, their “hysterical” vomiting suggested the loss of physical control—via a weak stomach, similar to that of a woman or child—that signaled the breakdown of bodily autonomy and self-governance typically associated with servicemen. And yet, despite these gendered implications, medical accounts read as relatively sympathetic to the patients and do not actively note their failure to meet gendered expectations of stoicism in the face of trauma.

Descriptions of olfactory-induced shell shock do reveal how wartime smells that defied easy explanation or classification “haunted” some victims, even when removed from the conditions of war that engendered these sensory traumas. Smell proved a powerful psychological factor in experiences of combat in the ways that it returned discharged soldiers to previous, traumatic experiences. Homebound supporters may have insisted that smells like lavender gave ease and comfort, but this process also worked the other way when unfamiliar smells gave rise to memories of trauma and dislocation. Descriptions of distressing sensory experiences of war arguably came to dominate postwar accounts, much in the same way that, as Gullace has shown, wounded and disabled veterans came to control narratives of war and commemoration as the conflict wore on.Footnote 101 In this regard, the incongruence between the smells of a fictitious home and those of the front was not only lived and experiential but also a question of representation; the otherworldly nature of wartime scents became tied to trauma, operated on a more solemn emotional register than did allegedly soothing scents of home, and subsequently figured in postwar accounts as the definitive smellscape of the Great War.

Reception of Smells

Visceral—and dominant—accounts from combatant interlocutors threw into question the efficacy of perfumery and scented goods as effective means to mask the everyday stench of life at the front. A handful of frontline accounts address this disjuncture, betraying a mixed response to the introduction of domesticated, so-called British scents to trenches and field hospitals, with some pointing out the frivolousness of the items. This comes to the fore in a 1916 piece in the Illustrated War News that questioned both lavender's utility and the efforts of white women who transported scented goods to the battlefield. In her column Women and the War, Claudine Cleve characterized this work as “not particularly useful,” disparaging the “conscientious maid or matron [who] may make herself thoroughly tired sending lavender to the soldiers in hospital; but then Tommy is not really very much given to lavender water, and transport might be unnecessarily blocked by the packages.” Instead, recommended the author, women should devote themselves to “real, soulless, unromantic work” rather than “amateurish busybodiness that satisfies conscience without doing anybody much good.”Footnote 102

Cleve's admonishments reflect deeply classed and gendered debates around the utility of certain forms of wartime work. But they also highlight the classed and gendered characterizations of scented items themselves, in this case raising doubts over the efficacy—the “good”—of scent to ameliorate the horrors of wartime smellscapes. Similar messages appeared in satirical form. An article in the trench magazine The Blunderbuss followed the trials of a novice cadet. During a crush of bodies in the trenches, Rufus, the fictional youth, “came very closely into contact with a box of chocolates and a lavender scented handkerchief”—two common soldier luxuries—before exclaiming “I hate them both!”Footnote 103 Another satirical account from Fall In magazine joked that lavender sachets were at least good for helping Bill the Bomber appear more manly when he stuffed “lavender bags up his tunic to stick his chest out.”Footnote 104 Both examples play with feminized associations of scented items to disrupt standard expectations of idealized white masculinity. In the case of Rufus, his disdain for ladies’ gifts in a moment of bodily danger subverted perceptions of the “ideal-typical British soldier” as “brave, cheerful, martial, and fair.”Footnote 105 Instead, Rufus betrays a childishness that counters dominant expectations of the maturing effects of wartime service.Footnote 106 Meanwhile, Bill the Bomber augmented his physique in a performative display of exaggerated masculinity, playing on ideals versus the realities of men's bodies in service to their country.

But a humorous approach to smellies did not necessarily preclude their having desirable effects, at least according to deeply mediated sources from frontline supporters. As Das notes, “The sense of smell, unlike vision, touch or taste . . . is a stimulus to the powers of both memory and fantasy.”Footnote 107 The potential for unlocking such effects figured in accounts from more sympathetic observers, who suggested that scents did exactly what their supporters hoped; they forged a sentimental connection to a traditional (and invented) English life. But this did not mean that scented gifts demanded the upholding of traditional gender conventions. In fact, they complicated prescribed gender roles by allowing for alternate modes of emotional and affective expression among white servicemen that subverted idealized forms of martial masculinity. In one letter of thanks quoted in the Times, for example, an anonymous chaplain admitted that he had expected that “some [soldiers] would appreciate [lavender bags], but had no idea that they would appeal as they do to nearly all.”Footnote 108 Another account noted that, at a hospital at Valetta, soldiers were “crazy about” verbena bags “and show[ed] their pyjama pockets stuffed full of the dried leaves.”Footnote 109 For one soldier, the bags “reminded [the sturdy Tommies] of their mother!”Footnote 110 Scent's transformative possibilities allegedly shifted soldiers from “sturdy” representatives of heroic masculinity into vulnerable figures pining for maternal comforts.Footnote 111 However, the accounts did not present these gendered transformations as disruptive; neither were convalescents’ appreciation for scented gifts deemed signs of luxurious degeneracy that threatened their martial masculinity. Instead, the items allegedly figured as a source of comfort for white servicemen who welcomed the domesticating, peaceable qualities of the gifts.

In keeping with narratives of sensory reordering of soldier experience, mediated accounts also emphasized scented gifts’ alleged effects in field hospitals, trenches, and ambulance trains as emblems of domesticated order.Footnote 112 These liminal spaces, characterized by what Mulk Raj Anand deemed “the smell of blood and drugs,” could allegedly be “civilized” via scented gifts and their invocations of white, English rural life.Footnote 113 Supporters argued for scent's civilizing properties—like soap, which had, through much of the nineteenth century, functioned as a potent symbol of state power in both domestic and colonized contexts. Anne McClintock and Timothy Burke have shown how hygiene initiatives targeted the cleanliness of the urban poor and colonized people, promoting soap as a means to civilize—and dominate—marginalized groups living under British rule.Footnote 114 As soap allegedly functioned to domesticate unruly bodies, so lavender was understood to order and civilize unruly smellscapes in the context of war.Footnote 115 Claims of the alleged civilizing properties of smell were especially notable because wartime spaces functioned as “contact zones,” characterized by cross-cultural, multiracial encounters among soldiers from Britain, the Indian subcontinent, the Caribbean, and beyond. As Anna Maguire shows, camps and other sites brought about “moments of intimate and human connection—in conversations, meals, and leisure time—that ran parallel to more antagonistic constructions of identity.”Footnote 116 Frontline accounts of gifts of scent did not directly acknowledge this, and instead celebrated white volunteers for cultivating a civilized British smellscape for imagined constituencies of white English servicemen, envisioned in exclusively white spaces.

Mischaracterized as they were, these spaces were nonetheless impermanent, and supposedly civilized smells were also alleged to mitigate the spatial dislocations wrought by war. Accounts highlighted the transportability of smellies as means to assert a sense of Englishness and order during transition and travel. The chaplain mentioned above insisted that lavender bags made his field hospital “quite fragrant” and full of “pleasure and comfort”: “Nearly every badly wounded and sick patient has a lavender bag pinned on his pillow this morning (they ask to have them pinned on).” But dressing stations and field hospitals were temporary sites, and “most of those who are evacuated to base hospitals are careful to take their little bags with them.”Footnote 117 The stabilizing properties of eau de Cologne in a moment of transition also featured in an anonymous account by a “Nursing Sister.” Recounting her time on an ambulance train near Boulogne in January 1915, she described a young officer “dressed in bandages all over.” Having been “put into clean pyjamas” and given “a clean hanky with eau-de-Cologne, he said, ‘By Jove, it's worth getting hit for this, after the smells of dead horses, dead men, and dead everything.’”Footnote 118 For this officer, the commercial scent represented a return to order, in the form of a recognizable smellscape that signaled private life before his deployment, in contrast to the death and liminality of his wartime experience.

Despite such laudatory reports, the power and potency of wartime smells defied attempts at containment. Alongside the praise of scented goods, then, other, ambivalent accounts foregrounded the labor behind them rather than their efficacy. A fictionalized interview in Punch in 1916 featured a hospitalized Cockney soldier, “Truthful James,” who recounted his experiences with trench surgeons, German spies, and a general shortage of anesthesia. For him, the services provided at field hospitals were “all part of the game,” the game being “Comforts for Tommy”: “Everyone has their own way of making us happy, not forgetting the dear lady what sent us three hundred little lavender bags, with pretty little bows on them, all sewn by herself, to keep our linen sweetly perfumed. It's nice to think that they all mean well.”Footnote 119 The author has foregrounded the care invested in crafting the bags, if not their practical use, envisioning the feminized labor undertaken by the “dear lady” as linking the fictional James to home, even though his comment “they all mean well” suggests limited material effects of such trench “comforts.” Nonetheless, the fictionalized account recognized the outpouring of voluntarist campaigns in England, materialized in this instance in the form of hundreds of small, hand-tied bags.

Cockney “James” was not the only representation of appreciation for the labor of white women and girls in supplying domesticated scents. In the memoir quoted at the start of this article, Olive Dent warmly praised women volunteers—some of them no doubt her readers—who contributed to the war effort, including by providing English smellies: “For [the boys’] sake it is good to see a new consignment, bunches of half a dozen sprigs of lavender, the stalks serving as handle, and the blooms shielded with a muslin cover caught with ribbon, an excellent time-saving, handy, convenient method of sending out the lavender.”Footnote 120 In Dent's account, infantilized and vulnerable soldier-patients are especially receptive to soothing, familiar smells of home.Footnote 121 She mobilizes lavender's properties as a soporific—and a reminder of an allegedly innocent English past—to calm soldiers in their final moments as they inch toward the “Great Sacrifice.”Footnote 122 However, as literary critic Nancy Martin has noted, Dent's writing had sanitizing tendencies, particularly in its “descriptions of the war's emotional and physical suffering.”Footnote 123 This observation suggests that Dent's account of lavender was not so much an accurate depiction of white British servicemen's appreciation as a calculated acknowledgment of the “excellent time-saving, handy, convenient” work of middle-class and elite female readers in England.Footnote 124 In this way, accounts that emphasized lavender's positive effects maintained the alleged symbolic power of national scents—and homebound labor—even among the realities at home and disordered smellscapes of war. Celebrations of perfumed items acknowledged the efforts of white civilians while resisting the destabilizing realities of war, asserting an ability to return, at war's end, to an imagined prewar life set in England's gardens and southern landscapes.

To be sure, the defining feature in the promotion of both philanthropic and commercial scents was an invocation of the pastoral designed to transport white soldiers back to the bucolic fields of home. One female fundraiser envisaged “[m]omentary relief . . . and visions of gardens and quiet things as the little lavender cushion is pinched and turned, and the fragrance creeps through the coils of a wearied brain.”Footnote 125 Another imagined that the bags brought a soldier “the memory of bygone days of peace and rest, and in some cases the scent of his beloved cottage garden.”Footnote 126 Such notions invoked a Britain characterized by idyllic countryside, relying on tropes of English pastoralism to incite responses in homebound readers as much as in servicemen themselves. They conjured values that Alun Howkins views as “closely identified with the rural south”—“[p]urity, decency, goodness, honesty, even ‘reality.’”Footnote 127 While scents like lavender could not provide physical warmth, protection, or nourishment, supporters argued for their alleged effects on white, English-born servicemen from across classes via their transformative, imagined possibilities.

Conclusions

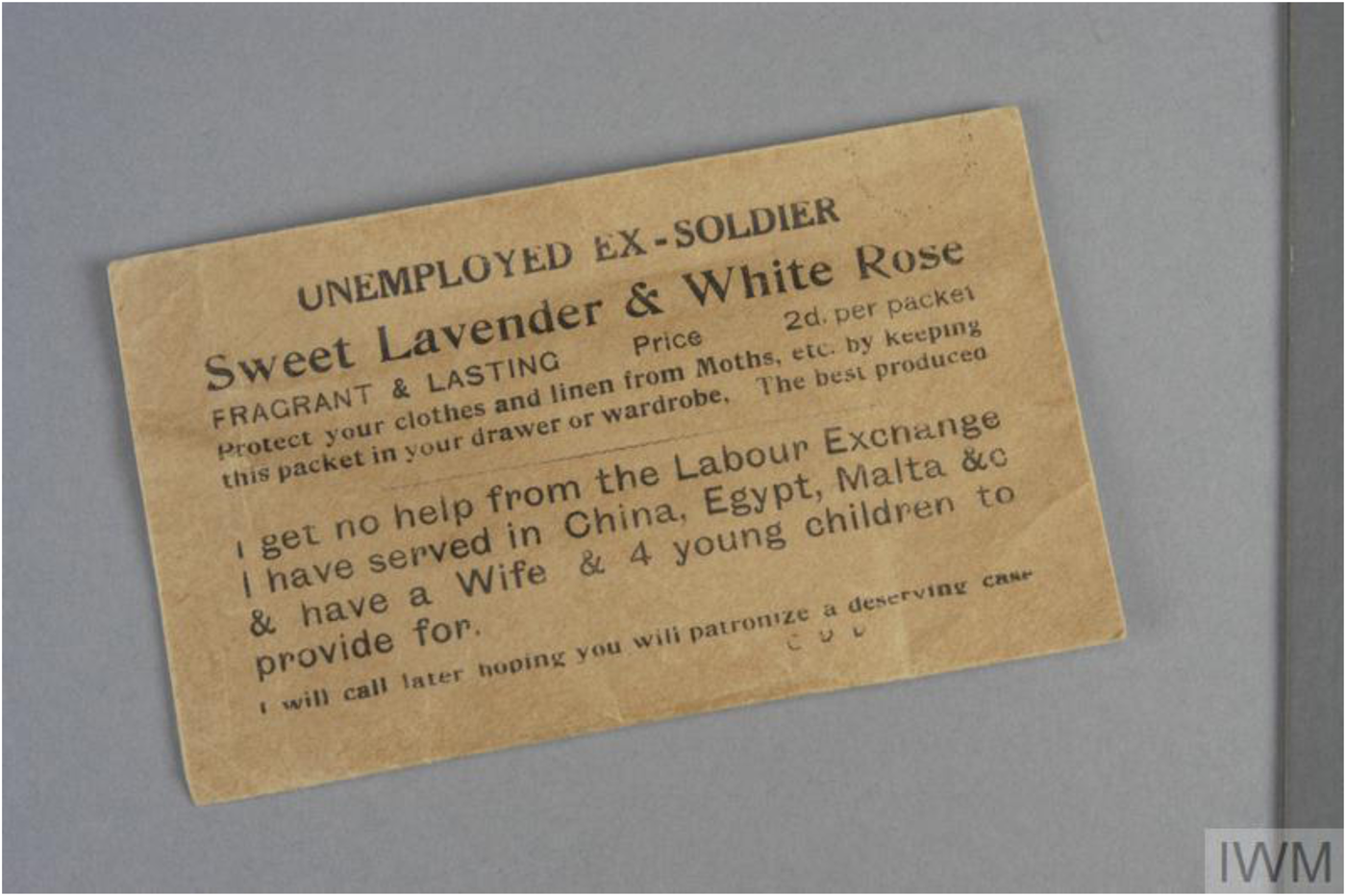

When they returned home from the war, some discharged English servicemen understood the emotional power of scent and subsequently mobilized it for more material purposes. Social, racial, and gendered transformations marked the postwar world, as returning veterans sought work, following, in hundreds of thousands of cases, life-altering injuries.Footnote 128 Some unemployed men adapted the nationalist schemes of civilian women and perfumers to their benefit, appealing to the sentimentality of British smells to inspire sympathy—and supplementary funds. The Imperial War Museum collections include three lavender sachets assembled and prepared by unknown veterans and probably sold door-to-door or on the streets. The professionally printed package of one example requests assistance for a “deserving case” who received “no help from the Labour Exchange.” Its text highlighted the efficacy of lavender against moths, a well-known practice that simultaneously invoked idealized forms of domestic privacy (figure 3). The other two items take a more rudimentary form, their pleas handwritten by the veteran or his loved one: “Best English Sweet Lavender / Twopence or 4 for 6 / Sold by an unemployed Clerk” (figure 4). It is unclear how successful this tactic was in soliciting donations—and affective responses—from fellow Britons.Footnote 129 Veterans’ efforts nonetheless suggest the remobilization of prewar and wartime olfactory mythologies rooted in an invented white English past, but in an attempt to transform the social and material conditions of their lives rather than wartime smellscapes. In the postwar context, traditional scents now supported a new constituency of those discharged, disabled, and socially displaced by war.

Figure 3 Scented sachet offered for sale by unemployed ex–First World War soldier. Imperial War Museum © IWM EPH 4505.

Figure 4 Scented sachet offered for sale by unemployed ex–First World War soldier. Imperial War Museum © IWM EPH 4506.

Even in the postwar moment, traditional scents’ renewed relationships to memory, Britishness, and nostalgia enhanced their emotional capital and valuation as productive goods. By recasting and reframing usages of what were deemed British scents, groups on the home front—volunteers and commercial perfumers alike—had signaled their adherence to prewar symbols of a collective identity: one undergirded, inaccurately, by white, rural Englishness. In a striking development, these scents would undergo a dramatic gender transformation in the interwar period when industry leaders, advertisers, and consumers remade certain grooming items, including perfume, as more definitively feminized. The promotion of scent's traditional and medicinal properties gave way to vibrant development in the beauty and cosmetics industry, as commercial providers, including perfumers, launched new goods to serve a transformed consumer market propelled by bold new fashions for women. Notably, these products were more definitively demarcated along gender lines, and prewar emphases on gender-neutral items gave way to a rise in explicitly feminized goods designed for the “flapper,” “modern girl,” or the allegedly “effeminate man” who, in his use of cosmetics and other wares, argues Matt Houlbrook, was now seen to “possess . . . illicit sexual desire.”Footnote 130 In a few short years, Britain's market in scents was increasingly delimited by sex, as the new items’ gendered delineations operated alongside traditionally unisex trends.

In this way, and many more, the war resulted in disjunctures between older sets of cultural signifiers and new lived experiences. At times, these marked a crossroads between “a traditional, idealized value system” and a “radical new order of experience”Footnote 131 at which conventional symbols of prewar life could exist. Disjunctures extended to traditional smells like lavender and eau de Cologne, which were shored up in the face of postwar social, gendered, racial, and economic changes. Conceivably, the symbolic associations of these items were for some consumers now linked to their wartime experience as servicemen, field-hospital patients, or the medical personnel who served them. For these individuals, perfumed items were now inextricably connected to sensory experiences of war and perhaps elicited their own less desirable olfactory memories. Yet, despite these new sensory entanglements among frontline actors, scented goods resoundingly retained symbolic connections to an imagined—and allegedly stable—home life. This domesticity aligned with a white, English conservatism that dramatically expanded, in new forms, through the interwar period, and, as Alison Light memorably argued, “would rather leave things as they are than suffer the pain of disturbance.”Footnote 132 This was even the case in the face of new, gender-specific scents, and lavender and eau de Cologne stood as stalwarts against trendy offerings in interwar perfumery. Rather than commemorating pain and loss, traditional British scents represented, for many, deeply coded values of whiteness, pastoralism, and a muted patriotism couched in domesticity, in response to the gendered, raced, and classed realities of war and its aftermaths.