Protesting is a foundational democratic tool through which people express their preferences and pressure political actors to act (Gause Reference Gause2022; Gillion Reference Gillion2020). However, the degree to which protests achieve their goals is determined partly by how the media cover protests (Koopmans Reference Koopmans2004). Researchers and political strategists have noted how media narratives shape how the broader public perceives a protest and its motivations (e.g., Barakso and Schaffner Reference Barakso and Schaffner2006; Davenport Reference Davenport2009). However, much less is known about how the individuals involved in a protest shape the nature of news coverage. This paper builds on evidence of racial disparities in other forms of news media coverage to explore how the race of protesters affects how media depict protests.

Anecdotal evidence suggests media vary their language depicting protests with the race of protesters. Consider this Washington Post headline: “Street Finally Reopens Four Days after Ferguson Riots.” A similar headline appears in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: “Ferguson business districts slowly mend after riots.” The event descriptions, particularly the use of the term riot, negatively portray the mostly Black Ferguson protesters. These headlines contrast those offering a less antagonizing view of mostly White Occupy Wall Street protests. For example, this Washington Post headline, “Occupy Wall Street inspires new generation of protest songs.” Or this Huffington Post headline: “UC Davis Police Pepper-Spray Seated Students in Occupy Dispute.” Unlike the Ferguson protests headlines, the Occupy and UC Davis headlines focus on the inspiration and victimization of primarily White protesters. Are these differences in the framing of protests anecdotal or systematic?

A litany of social science research reveals considerable discrepancies in how the news media depicts people of color relative to White Americans on a wide range of issues (e.g., Dixon and Linz Reference Dixon and Linz2000; Entman Reference Entman1992; Gilliam and Iyengar 1998, Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Gilliam et al. Reference Gilliam, Iyengar, Simon and Wright1996; Romer et al. Reference Romer, Jamieson and de Coteau1998). These racial biases in media coverage are consequential for public opinion toward policies that disproportionately affect people of color. For example, the overrepresentation of non-White people as criminal perpetrators in crime-related news stories strengthens the cognitive association between people of color and criminality in the mind of White viewers, such that the connection (e.g., Black people and crime) becomes chronically accessible for use in race-related evaluations (Dixon and Azocar Reference Dixon and Azocar2007; Gilliam and Iyengar 1998, Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Gilliam et al. Reference Gilliam, Iyengar, Simon and Wright1996; Oliver and Fonash Reference Oliver and Fonash2002). Similarly, racial biases in news media have conservatized public opinion toward affirmative action, punitive crime policies, presumptions of culpability, and determinations of punishment (Gilliam and Iyengar Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Peffley et al. Reference Peffley, Shields and Williams1996). Just one exposure to these unfavorable characterizations might trigger strong adverse reactions to protesters’ issues.

Despite evidence of disparities in news media depictions of White and non-White individuals across various contexts, we argue that there are two significant gaps in existing literature on the topic. First, there is limited research systematically exploring how depictions of protest activity vary by the race of the protesters (c.f., Baylor Reference Baylor1996; Davenport Reference Davenport2009; Watkins Reference Watkins2001; Weaver and Scacco Reference Weaver and Scacco2013). While past research has looked at how ideology and even racialized topics may affect media coverage (Di Cicco Reference Di Cicco2010; Leopold and Bell Reference Leopold and Bell2017; Gitlin Reference Gitlin2003; Ophir et al. Reference Ophir, Forde, Neurohr, Walter and Massignan2023), we are not aware of any research that explores how the race of protesters affects how they are characterized in news media. Equally important, greater attention to the impact of protesters’ race on news media coverage of protest activity may help clarify conflicting findings in the literature on how anti-racist aims shape news media coverage patterns (Leopold and Bell Reference Leopold and Bell2017; Ophir et al. Reference Ophir, Forde, Neurohr, Walter and Massignan2023). Understanding how the media portrays protest activities is uniquely important because the normative valence of protest event characterizations can affect levels of support for protesters’ goals, police actions, and punitive crime policies that aim to suppress protest activity (Nelson and Oxley Reference Nelson and Oxley1999; Weaver Reference Weaver2007).

Second, while there is ample research demonstrating biases in how news media depict people of color relative to White people, the emotive components of these frames are not well-understood (e.g., Dixon and Linz Reference Dixon and Linz2000; Entman Reference Entman1992; Gilliam and Iyengar Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Gilliam et al. Reference Gilliam, Iyengar, Simon and Wright1996; Romer et al. Reference Romer, Jamieson and de Coteau1998). Specifically, it is unclear if these biases are driven by the systematic use of language evoking negative emotions like fear, anxiety, or anger. Attention to the emotions evoked during commentary on protests is important as each of these emotions has distinct consequences for the attitudes and behavior of audiences (Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2005; Redlawsk Reference Redlawsk2002). For example, anger and fear are critical emotions due to their grounding in a sense of threat and their association with prejudice toward outgroups’ anti-social behaviors (Lerner and Keltner 2000, Reference Lerner and Keltner2001 ; Smith and Ellsworth Reference Smith and Ellsworth1985). Equally important, anger and fear have well-documented effects on political behavior. They often depress political engagement, particularly among people of color (Brader Reference Brader2005; Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011). Consequently, media depictions of protests that evoke a sense of anger or fear may heighten the public’s distrust of people of color and negatively influence observers’ willingness to support the protest or engage in related political activity (Barreto and Garcia-Rios Reference Barreto and Garcia-Rios2016; Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019; Ramírez Reference Ramírez2013).

Of course, media coverage that evokes anger or fear is not necessarily the same as media coverage that frames a group in an explicitly negative light. For example, media coverage of protests may employ anger in a way intended to be sympathetic toward the protesters, such as by conveying the fear felt by participants or even indignation at the treatment of protesters. Still, the perception that the anger or fear conveyed and evoked in news coverage is sympathetic toward protesters does not negate how anger and fear can increase biases in information-seeking, depress political engagement, and heighten racial disparities in political engagement (Brader Reference Brader2005; Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011). In turn, evoking a sense of anger or fear in news media coverage of protests of mostly people of color, regardless of the target of the anger, can aggravate differences in racial attitudes and racial disparities in political participation.

To this end, we explore whether news media are more likely to discuss protests using words evoking anger and fear when protests consist primarily of people of color versus White people. We created a novel dataset of 638 transcripts of televised news stories on protest activity throughout the United States between 2008 and 2016. While television is certainly not the only source of news, about two-thirds of Americans get at least some news from televised broadcasts, and televised news still has a great deal of influence on the behavior of both citizens and elites (Clinton and Enamorado Reference Clinton and Enamorado2014; Forman-Katz and Matsa Reference Forman-Katz and Matsa2022; Hopkins and Ladd Reference Hopkins and Ladd2014). We focus exclusively on liberal protests to account for variations in protest media coverage based on the ideology of protesters’ grievances (Di Cicco Reference Di Cicco2010; Gitlin Reference Gitlin2003).

Consistent with our expectations, we find that broadcasts of mostly non-White protesters are more likely to use language associated with fear and anger than coverage of mostly White protests. Our findings also suggest that fear-laden words are especially prevalent in media coverage of non-White protesters when expressing a grievance concerning police misconduct. Equally notable and contrary to our expectations, the network’s ideology is not a consistent predictor of the likelihood of using fear- and anger-laden frames when covering liberal protests. For example, FOX News, the most popular, conservative-leaning cable network, is more likely to use anger-invoking words in its protest coverage than MSNBC, the most popular, liberal-leaning cable network. Yet, only liberal networks show differences in the use of fear- and anger-invoking language based on the race of protesters, perhaps because conservative networks would use similarly negative language, regardless of the protesters’ race, when reporting on liberal protests. Still, in illustrating these patterns, we highlight the divergent ways in which media depicts the political participation of White and non-White Americans and how this may have implications for political behavior.

This work makes several contributions to the literature. First, we provide extensive evidence of racial biases in news coverage of protest activities. In doing so, we build on a growing body of evidence demonstrating that media coverage of protest activity is not universally negative but shaped by specific attributes of the protest and protesters (Boyle et al. Reference Boyle, McLeod and Armstrong2012; Leopold and Bell Reference Leopold and Bell2017; Ophir et al. Reference Ophir, Forde, Neurohr, Walter and Massignan2023). Additionally, we consider news coverage of a diverse set of protests on both cable and nightly network news to give a broad sense of racialized media coverage patterns. Our data collection also allows us to control for confounding factors that may shape protest news coverage, including whether a protest issue explicitly concerns race or police misconduct. Further, by focusing on anger and fear, we identify a key mechanism through which this coverage can shape ensuing considerations: triggering emotions linked closely to racial threat.

The Media, Protest, and Public Opinion

Mass media is a primary force shaping beliefs and attitudes among the broader public (e.g., Scheufele and Tewksbury Reference Scheufele and Tewksbury2007). The angle and exemplars of a given story can each affect how viewers think about the issue depicted. Entman (Reference Entman1993) offers one explanation of the implications of media’s schematic choices for interpreting events: “to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” (p. 52). The framing and presentation of events in the mass media can thus systematically affect how viewers understand the events (Price, Tewksbury, and Powers Reference Price, Tewksbury and Powers1997). That is, the extent to which any consideration from these broadcasts is brought to bear on individual attitudes may be contingent on how mass media has framed the dialogue surrounding the issues (e.g., Zaller Reference Zaller1992).

At best, media can aid protesters seeking to shift public opinion or pressure policymakers (e.g., Koopmans Reference Koopmans2004; Nelson and Oxley Reference Nelson and Oxley1999). Yet, while media can positively increase the public’s awareness of grievances and generate support for the protesters’ goals, it can also depict movement goals in ways that challenge their legitimacy and even depress political engagement. There are numerous examples of media presenting negatively biased coverage or misrepresenting movement objectives or events (Barakso and Schaffner Reference Barakso and Schaffner2006; Davenport Reference Davenport2009; Di Cicco Reference Di Cicco2010; Gitlin Reference Gitlin2003). Of course, framing effects are not limitless and can vary in their effectiveness. Nevertheless, there is a broad consensus that frames depicting non-White Americans have encouraged the spread of harmful associations. For example, Black and Latino people, in particular, are frequently over-represented in news stories focusing on crime and poverty; White people are more likely to be depicted as either victims or guardians of law and order (Dixon and Linz Reference Dixon and Linz2000; Romer et al. Reference Romer, Jamieson and de Coteau1998). These narratives affect attitudes by strengthening the cognitive association between non-White people and negativity and activating existing racial stereotypes and narratives (Dixon and Azocar Reference Dixon and Azocar2007; Gilliam and Iyengar 1998, Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Gilliam et al. Reference Gilliam, Iyengar, Simon and Wright1996; Oliver and Fonash Reference Oliver and Fonash2002). Importantly, these negative group cues in the media can activate racial attitudes, boosting their impact on political attitudes (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Hutchings and White2002; Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013).

Despite this broad pattern, little work explores whether similar racial disparities in news media framing are evident in protest coverage. Media coverage of protests has historically taken on a somewhat critical role, often relying on a “protest paradigm”—or a pattern of media coverage that systematically disparages protesters and protest groups (Gitlin Reference Gitlin2003; McLeod and Hertog Reference McLeod and Hertog1992; Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker1984). However, we argue that it is not simply that news media are dismissive of all protests, or even left-wing protests, or protests against racism (c.f. Di Cicco Reference Di Cicco2010; Leopold and Bell Reference Leopold and Bell2017). Instead, we argue that, similar to news coverage of other issues, news media coverage of protest activity is shaped by the race of protesters. This is to say, perhaps the “protest paradigm” and the “public nuisance paradigm” that has long defined the media’s negative characterization of protest activity is not only shaped by the ideology, tactics, and/or objectives of the protesters, but who the protesters are (Boyle et al.Reference Boyle, McLeod and Armstrong2012; Di Cicco Reference Di Cicco2010; Leopold and Bell Reference Leopold and Bell2017). We believe that better understanding how the race of the protesters shapes media coverage of the protest may also clarify conflicting findings about whether media coverage of protests against institutional racism (such as Black Lives Matter protests which at times consisted of mostly White protesters and other times consisted of mostly non-White protesters) has been favorably or negatively biased (Leopold and Bell Reference Leopold and Bell2017; Ophir et al. Reference Ophir, Forde, Neurohr, Walter and Massignan2023).

Of course, like other profit-driven institutions, the media have incentives to prioritize stories that pique their audiences’ interests and reinforce audiences’ beliefs (Gentzkow and Shapiro Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2006). This propensity is particularly consequential for people of color as it often results in frames that emphasize conflict (Oliver and Myers Reference Oliver and Myers1999) while reinforcing the often-negative prior beliefs about the populations involved (c.f. Gilliam and Iyengar 1998, Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Gilliam et al. Reference Gilliam, Iyengar, Simon and Wright1996; Oliver and Fonash Reference Oliver and Fonash2002). As a result, mainstream media reporting is prone to exhibiting systematic bias against minority-oriented movements (Davenport Reference Davenport2009). This bias is likely a driving factor in the public being less supportive of protests if the people protesting are described as “Black Americans” relative to when they are described as “Americans” (Jones and Cox Reference Jones and Cox2015).

It is important to note that reporters need not be explicitly or overtly racist for subtle bias to infiltrate their depictions of minority protesters. Work on implicit racial attitudes has demonstrated the pervasive presence of negative implicit prejudices toward people of color, particularly Black people (Greenwald et al. Reference Greenwald, McGhee and Schwartz1998; Nosek et al. Reference Nosek, Smyth, Hansen, Devos, Lindner, Ranganath, Smith, Olson, Chugh, Greenwald and Banaji2007). These findings are robust, despite objections that prejudices toward Black people result from learned stereotypes, not personal animus (Arkes and Tetlock Reference Arkes and Tetlock2004; Rudman and Ashmore Reference Rudman and Ashmore2007).

Implicit and explicit prejudices toward Black people also broadly influence perceptions of Black protests and urban unrest (Jones and Cox Reference Jones and Cox2015). For example, during the 1960s Civil Right Movement, elite actors argued that protesters were lawless agitators, bringing crime and disorder to otherwise good-natured racial accord (Roberts and Klibanoff Reference Roberts and Klibanoff2006; Weaver Reference Weaver2007). The negative framing of Black protest was fortified in the mid to late 1960s when uprisings occurred in various cities in response to police brutality and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. (Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Weaver Reference Weaver2007). Importantly, this coverage fueled questions about Black people’s right to protest (Morgan Reference Morgan, Romano and Raiford2006). Simply reading a news story about a protest with mostly Black (relative to White) protesters or characterized as a Black Lives Matter protest (relative to an undefined protest) leads to more negative evaluations of protest, including perceptions that the protest was more violent and requires more policing (Manekin and Mitts Reference Manekin and Mitts2022; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Gaozhao, Dukes and Templeton2023). It is difficult to understate the effects of these patterns on American democracy. Native American organizers concerned that news media coverage of protests by indigenous peoples reinforced negative stereotypes and marginalized their concerns have even cautioned people against organizing protests to gain media attention for their political concerns and goals (Baylor Reference Baylor1996).

Taken together, we suspect newscasters are just as susceptible as the broader public to racial biases. These biases will be detectable in how newscasters discuss protesters with different racial backgrounds. In turn, we expect that there will be marked differences in protest event coverage based on the racial makeup of the protesters. We differentiate this work from past evidence that media are more likely to employ negative frames when covering protests about specific racial issues (e.g., discrimination against indigenous or Black people) and home in on whether media biases hinge on the race of the people protesting (Kilgo and Harlow Reference Kilgo and Harlow2019).

Fear and Anger in Media Portrayals of Protesters

While the work on racial bias in news media leads us to expect differences in the frames employed by media depending on the race of protesters, we do not know how this bias may present in protest coverage. Specifically, is there a difference in the emotional tone of these racial biases in news media coverage of protests of mostly non-White versus White participants? Given emotions’ decisive role in opinion formation, emotions likely shape how the broader public perceives media messages (Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2005; Redlawsk Reference Redlawsk2002). Indeed, the presence of emotional content is a crucial factor influencing the effectiveness of news frames (Lecheler et al. Reference Lecheler, Bos and Vliegenthart2015). Nevertheless, the particular influence can vary with the type of emotion triggered. For instance, the negative emotions of pity, guilt, empathy, embarrassment, and shame are inherently social. These emotions, while negative, are rooted in compassion and tend to be linked to prosocial behaviors (e.g., Lewis Reference Lewis, Lewis and Haviland1993).

On the other hand, anger and fear are associated with a sense of threat and much more anti-social outlooks (Lerner and Keltner Reference Lerner and Keltner2001; Smith and Ellsworth Reference Smith and Ellsworth1985). Anger is associated with a desire for aggression and contempt toward the outgroup (Fiske et al. Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002). Similarly, fear is associated with a sense of intolerance and ethnocentrism (Cottrell and Neuberg Reference Cottrell and Neuberg2005; Marcus et al. Reference Marcus, Sullivan, Theiss-Morse and Wood1995). Despite the similarities between fear and anger and their shared links to racial threat, they are empirically distinct emotions, suggesting differential impacts on the reception of media messages.

Fear is closely related to anxiety and is often associated with heightened perceptions of risk and, importantly for our research question, reduced support for the subject (Huddy, Feldman, and Cassese Reference Huddy, Feldman, Cassese, Neuman, Marcus, Crigler and MacKuen2007). The reduced certainty, in turn, generally makes individuals want to seek out new information and therefore be more hesitant to participate in politics (Brader Reference Brader2005; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011). Additionally, the search for new information undertaken by fearful individuals is likely to be biased in favor of information consistent with these individuals’ prior beliefs (Gadarian and Albertson Reference Gadarian and Albertson2014). People of color often engage in anti-status quo protests (e.g., Davenport Reference Davenport2009), and they are less likely than White protesters to be viewed as engaging in protests that will make the country better (e.g., Jones and Cox Reference Jones and Cox2015). Information-seeking may consequently reduce support for protests by people of color and open viewers to elite narratives justifying police actions meant to suppress protest activities and frame protesters’ grievances as illegitimate (e.g., Weaver Reference Weaver2007).

Anger stands in contrast to fear as an emotion strongly linked to arousal and action and increased levels of political participation (Banks Reference Banks2016; Barreto and Garcia-Rios Reference Barreto and Garcia-Rios2016; Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019; Ramírez Reference Ramírez2013; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011). Anger can also trigger risk-seeking behavior and reduce the quantity, and even the quality, of political information-seeking (Lerner and Keltner Reference Lerner and Keltner2001; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Hutchings, Banks and Davis2008). That said, anger is a political tool and resource that is not equally accessible to everyone. While White people’s anger is generally tolerated and even glorified, people of color, especially Black people, are often condemned and criticized for expressing anger (Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019). The relationship between anger and political participation and significant racial disparities in the ability to express and act on anger highlight the importance of the frames used in news media. This relationship means that if news media coverage of protests consisting primarily of people of color evokes more anger than coverage of mostly White people, then the coverage may not only amplify feelings of aggression and contempt toward the outgroup. It will also likely increase White political participation while decreasing the quality of their information-seeking, exacerbating the racial disparities in political participation between White Americans and people of color (Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019).

The history of threat narratives in media depictions of non-White people (Dixon and Linz Reference Dixon and Linz2000; Entman Reference Entman1992; Gilliam and Iyengar Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Gilliam et al. Reference Gilliam, Iyengar, Simon and Wright1996; Romer et al. Reference Romer, Jamieson and de Coteau1998) suggests that characterizations of non-White protesters will rely more heavily on frames that emphasize the threat-related emotions of fear and anger relative to characterizations of majority White protests. In addition, since protest movements are often anti-status quo, protests consisting of mostly non-White people may evoke concerns about threats to existing power structures (Blumer Reference Blumer1958; Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996). But, again, newscasters need not be aware of racial biases for racial biases to affect their media portrayals of protesters. Consequently, we expect the following:

H1: Media depictions of protests with mostly people of color are more likely to use language associated with fear and anger than those with mostly White protesters.

We expect differences in the depiction of protest to vary by protesters’ race and by the outlet covering the event. There is significant variation in how news media frame events, which extends to how news media frame the message the protesters are trying to disseminate (Barakso and Schaffner Reference Barakso and Schaffner2006; Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Davenport Reference Davenport2009). Media generally prioritize stories and frames that pique their consumers’ interests and align with consumers’ beliefs (Gentzkow and Shapiro Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2006). In turn, how an outlet covers a protest is often shaped by the audience of a specific outlet.

We expect differences in protest frames to be most pronounced in cable news coverage since cable news outlets, like MSNBC, CNN, and FOX News, appeal to more specific audiences than broadcast news outlets (Bae Reference Bae2010). For instance, MSNBC offers politically liberal content for its mostly liberal audience, while FOX News contains the most politically conservative content to appeal to conservative audiences (Groseclose and Milyo Reference Groseclose and Milyo2005; Martin and Yurukoglu Reference Martin and Yurukoglu2014). Indeed, Fox News was more likely to portray a 2015 uprising in Baltimore as a riot, while CNN and MSNBC used more legitimizing language in referring to the event as a protest (Waldman Reference Waldman2015).

Relative to cable news outlets, broadcast networks attempt to appeal to general audiences (Bae Reference Bae2010). Thus, broadcast networks are more balanced than cable news stations (Fico et al. Reference Fico, Zeldes, Carpenter and Diddi2008). Still, despite their broader appeal, broadcast news networks have ideological leanings that differentiate their content for viewers. For example, ABC tends to be more conservative and supportive of Republican presidential candidates than NBC and CBS (Diddi et al. Reference Diddi, Fico and Zeldes2014).

The ideological leanings and viewership of a media outlet have implications for how media cover protests, particularly when the racial composition of the protesters appears to be heavily skewed. For example, ideological conservatives tend to be more supportive of law and order and less open to non-institutional forms of political participation, like protests. Further, liberal and conservative political coalitions have become increasingly sorted by racialized attitudes (Mason Reference Mason2018; Tesler Reference Tesler2016). Media outlets may consequently face incentives to employ different frames based on the perceived racial composition of protesters, depending on their audience’s political leanings. Further, media with conservative slants are more likely to use outrage speech (e.g., name-calling, character assassination, mockery, belittling, and obscene language) than media with liberal slants (Sobieraj and Berry Reference Sobieraj and Berry2011). Footnote 1 This discussion leads us to our second hypothesis:

H2: The difference in the likelihood of using anger- and fear-laden language when describing White vs. non-White protesters will be greater in media outlets with conservative leanings than in those with liberal leanings.

White vs. Non-White Political Demonstrations—A Content Analysis

To evaluate our theoretical claims, we created an original dataset of television news transcripts of protest events between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2016. We hired three undergraduate research assistants to conduct a Boolean search to identify and code any transcript available on LexisNexis discussing a protest event. We confined the search to the highest-rated nightly news programs on the three major cable news networks (CNN’s AC360, MSNBC’s Maddow, and Fox News’s O’Reilly Factor) and the three major broadcast news networks (ABC’s World News Tonight,Footnote 2 NBC Nightly News, and CBS Evening News). This news coverage corpus provides an ideologically diverse data of news organizations so that we may account for any differences in news coverage of protesters due to the ideological leanings of the television network.

A typical news transcript covers multiple topics. So, our research assistants read each news transcript produced by the Boolean search to extract the segments explicitly regarding a protest event. Then, we combined all protest-related segments within a single transcript as one observation. Once collected, research assistants coded the transcript observations for several variables.

To analyze differences in fear- and anger-provoking words, we relied on the EmoLex Dictionary (Mohammad and Turney Reference Mohammad and Turney2013). Mohammad and Turney (Reference Mohammad and Turney2013) drew from various sources to select the English language’s most frequently occurring unigrams and bigrams to create this dictionary. They then employed Mechanical Turk workers to evaluate and indicate the intensity of the emotion provoked by a given word. To increase the quality of the affective evaluations, each Mechanical Turk coder verified their familiarity with each term. Further, five different coders evaluated each term for emotional content. This process produced a set of about 10,000 terms coded for the degree to which they evoke feelings of fear and anger. In our analyses, the dependent variables are the number of fear- or anger-inducing words, respectively, in each transcript.

The primary independent variable for the analyses is the perceived race of the protesters. If research assistants could not easily identify the racial makeup of protesters from the content of the transcripts, they used information about the protest (e.g., the date, location, and issue) to search the Internet for images or videos to discern the racial makeup of protesters.Footnote 3 If at least a plurality of the protesters appeared to be people of color, then the non-White variable was coded a 1.Footnote 4 Otherwise, the protest participants were coded as White or a 0 in the non-White variable.Footnote 5

We also coded for the ideological leanings of the policy goals of the protest event to account for differences in the sentiment of coverage due to the ideology of protesters’ demands. All but 3 of the 638 observations had a clear ideological slant: 106 were conservative, and the remaining 529 were liberal. We subset the analyses for liberal protest demands since there are no conservative, non-White protests in the data. To further control for the nature of protests, research assistants also coded whether the issue was explicitly about a racial issue. Additionally, research assistants recorded the name of the television news network and the date the news coverage aired.Footnote 6 Finally, we include Transcript Word Count to control for the length of the protest-related discussion on the news network.

The Relationship Between Race of Protesters and News Frames

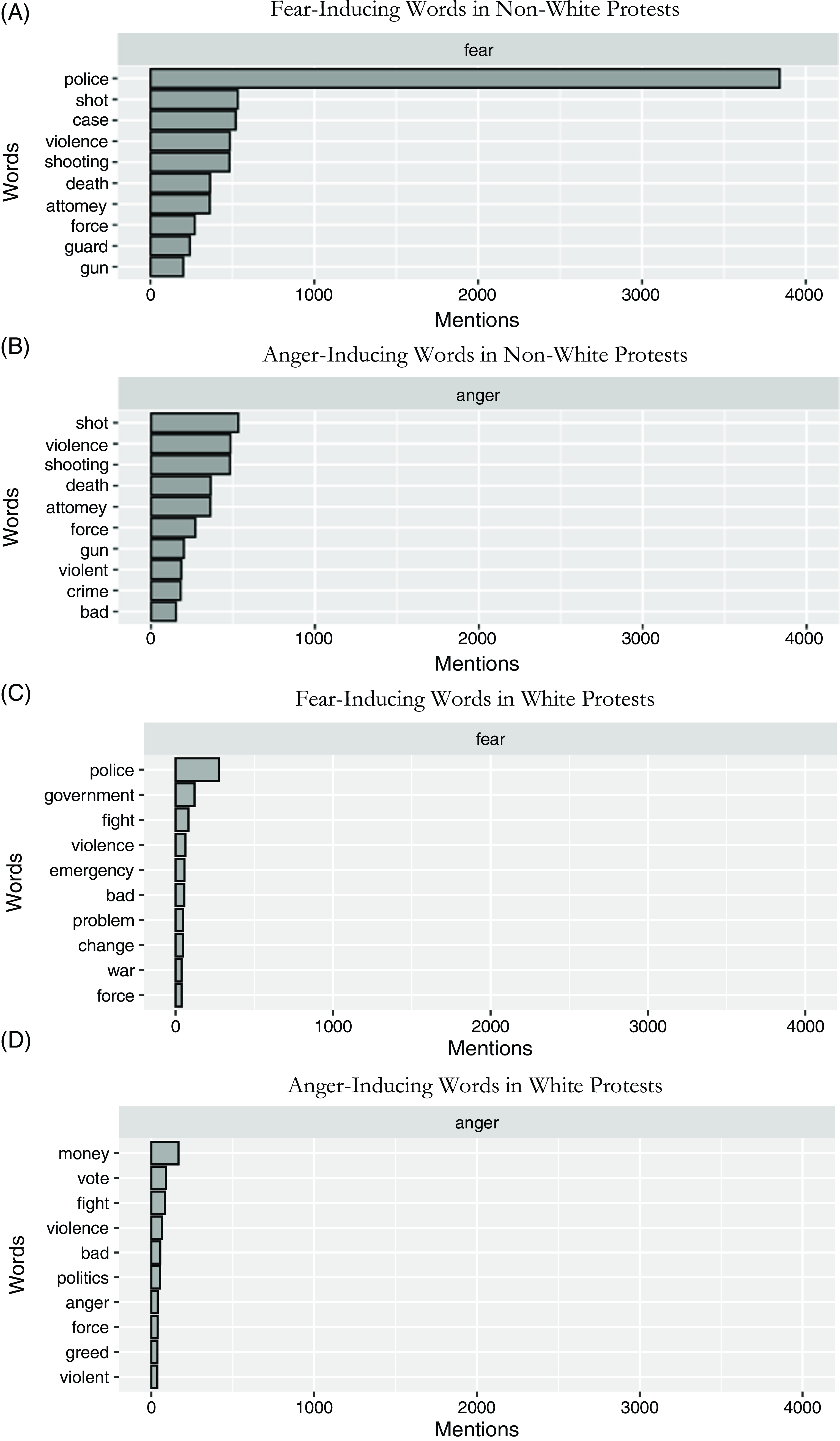

Does media coverage of protests vary depending on the race of the protesters? The descriptive findings in Fig. 1 suggest it might. Figure 1 displays the frequency of the most common words contributing to the anger and fear sentiments for non-White and White protests, respectively. Comparing the frequency of fear- and anger-inducing words in the top panels (A and B) to those in the bottom (C and D) suggests that news coverage of non-White protesters appears more likely to include words associated with fear and anger than coverage of White protesters.Footnote 7 By far, the most common word associated with inducing the sentiment of fear for transcripts covering non-White protesters is “police,” with almost 4,000 mentions across observations. The second most frequent word contributing to the fear sentiment for non-White protests is “shot,” with only around 500 mentions. Next, Fig. 1 suggests that “shot” is the most common word contributing to anger for non-White protesters. “Shot” does not appear as a common anger- or fear-inducing word for transcripts discussing White protests. “Police” is the most common fear-inducing word for White protests, though media use “police” far less often when describing White protests than they do in non-White protests. Since “police” and “shot” relate to police violence and “police” is mentioned disproportionately for non-White protests, we include Police Grievance in subsequent models to control for whether protests were about police violence.

Figure 1. Words contributing to the anger and fear sentiments in news media coverage of liberal protests

The multivariate regression analyses in Models 1 and 2 in Table 1 support the descriptive results. They demonstrate that media are more likely to use words that invoke fear and anger when covering mostly non-White protests than White protests, at least for protests with liberal demands. The average broadcast discussing protests with mostly non-White protesters uses almost two more fear-provoking words and nearly one more anger-provoking words than the average broadcast discussing mostly White protesters. These differences are statistically significant at the .01 level for fear and only at the .1 level for anger. While this is a small share of the words used in a typical story, people are typically exposed to many of these stories. In turn, while a single story may not have a noteworthy impact on peoples’ associations with non-White protesters, the consistent and repetitive nature of these exposures is cause for concern.

Table 1. Text analyses of media depictions of protesters (Liberal protests)

Standard errors in parentheses

*** p<.01,

** p<.05,

* p<.1.

To better account for media accounts of protesters based on protesters’ race, Models 3 and 4 in Table 1 include interactions between non-White and each news network. FOX is the omitted news network because it is the most ideologically conservative network. Consequently, the affect expressed in the language used by each network is in comparison to the affect evoked on FOX broadcasts. Figure 2 illustrates the average number of fear and anger words per story given the protesters’ race based on estimates from Models 3 and 4. Coverage of both White and non-White protesters employs words that provoke fear and anger. However, fear- and anger-laden words are more likely to occur in stories about protests with non-White protesters than White protesters.Footnote 8

The difference in the language that media use when covering White versus non-White protesters is larger for fear-laden words than anger-laden words. In fact, the difference in the likelihood of using words that evoke fear when covering protests consisting of mostly White protesters compared to those consisting of mostly non-White protesters is more than two times larger than the relative racial difference in the likelihood of using anger-emoting words. Perhaps, the smaller racial differences in anger are because evoking anger is not always viewed or experienced as a negative emotion. Again, whether consciously or unconsciously, people are more likely to respect and accept White people’s anger and mobilization while criticizing and condemning the anger and mobilization of other racial and ethnic groups (Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019). Thus, the media may generally use anger-laden words in support of White protesters and in opposition to non-White protesters’ protests. Meanwhile, media outlets appear more likely to use language that evokes fear when covering non-White protests, perhaps due to the perceived threat of non-White people’s protests.

Next, we consider whether variations in media coverage of protests exist based on the race and ideological leanings of the media outlet. Contrary to expectations, Fig. 3 suggests that only among liberal broadcast networks is the difference in fear- and anger-laden words of protesters larger for protesters of color than White protesters. While all networks are more likely to use anger- and fear-laden words more often for non-White protests than White protests, the differences are only statistically significant at the .05 level for the more liberal-leaning broadcast networks, CBS and NBC.Footnote 9 These findings may be due to the nature of our data. We focus on liberal protest demands to compare similar types of grievances. However, conservative media outlets likely employ negative sentiments for nearly all protesters, regardless of protesters’ race, with liberal grievances incompatible with their conservative audiences’ preferences.

Figure 3. Sentiment from text analysis of media depictions of protesters by media outlet liberal protests)

Note: Figure 3 displays the difference in the marginal effect of fear- (left panel) and anger-(right panel) provoking words given protesters’ race. Estimates are from Models 3 and 4 in Table 1.

The inclusion of control variables in our models helps assess how the subject of the protest may affect the tone of the news media coverage. In particular, is news media coverage of protests more likely to use fear- and anger-laden words whenever the protest is about a racialized issue, such as police brutality, immigration, or land rights? Moreover, does the relationship between policing-related grievances or racism-related protest grievances and the sentiment of news coverage overshadow the relationship between protesters’ race and the sentiment of news media coverage?

While protests concerning a racial issue are not more likely to use language associated with fear or anger than non-racial protests, grievances concerning police violence are statistically significant at the .01 level for all four models. Consistent with past work, the significant coefficient on Police Grievance in Table 1 suggests that the subject of the protest plays a significant role in the type of language used to cover the protest (Kilgo and Harlow Reference Kilgo and Harlow2019). Importantly, however, even when controlling for whether protests were about police violence, news coverage of non-White protesters was still significantly more likely to use language evoking fear and anger relative to coverage of White protesters. This demonstrates that even when we account for many of the reasons for protest that may have been likely to evoke fear and/or anger, we still find that protest coverage of mostly non-White protesters was more likely to involve language that evokes fear and anger than protests with mostly White protesters. To this point, terms like “violence” and “crime” were consistently more common in coverage of protest activity involving mostly non-White individuals relative to coverage of protest activity involving mostly White individuals.

These patterns could vary across the analysis period or weaken as protests became more common. The Year variable coefficient suggests that fear- and anger-inducing words may decrease slightly over time. Also, the sign of Transcript Word Count suggests that lengthier protest coverage uses marginally fewer anger- and fear-laden words than shorter coverage.

Robustness Checks

So far, the results confirm many of our theoretical expectations about the relationship between protesters’ race and media’s protest coverage. A series of robustness checks further validate these findings. First, focusing on the entire section of a transcript mentioning a protest might be too broad. Within a news segment, commentators may shift from speaking about the protesters to speaking about a related event or group and then back to the protesters. Thus, we focus on the language used directly preceding or following mentions of the protest event or its participants. Specifically, we searched the transcripts for specific mentions of “protester(s)” (Fig. 4A and B) or protest event type (i.e., “protest,” “rally,” or “riot”) (Fig. 4C and D) and limited our sample to the text only within 20-word windows surrounding these mentions.Footnote 10 We then re-analyzed the sentiment invoked during discussions about non-White and White protesters in the more narrowly selected text segments. These more confined analyses produce a conservative estimate of how protesters’ race may affect the affective language used in news coverage of these events.

Figure 4. Fear and anger in the 20 words around specific mentions (Liberal protests)

Note: Figure 4 displays the difference in the predicted probability of fear- (left panels) and anger-(right panels) provoking words given protesters’ race. Estimates are from Models 3 and 4 in Table A2 (A and B) and A3 (C and D).

Figure 4 demonstrates that news coverage employs more fear-laden language when referencing non-White protesters than White protesters. There are statistically significant differences in the usage of language evoking fear in coverage of non-White relative to White protesters, at least in the 20 words immediately surrounding specific mentions of “protester(s)” or “protestor(s)” (Fig. 4A). However, the differences are not statistically significant in the use of fear-invoking language based on protesters’ race in the words surrounding mentions of “protest,” “rally,” or “riot” (Fig. 4C). The differences in the use of anger-laden language based on protesters’ race also fail to reach statistical significance at the .05 level in analyses of the 20 words immediately surrounding specific mentions of words signifying a discussion of a protest event (Fig. 4B and D).

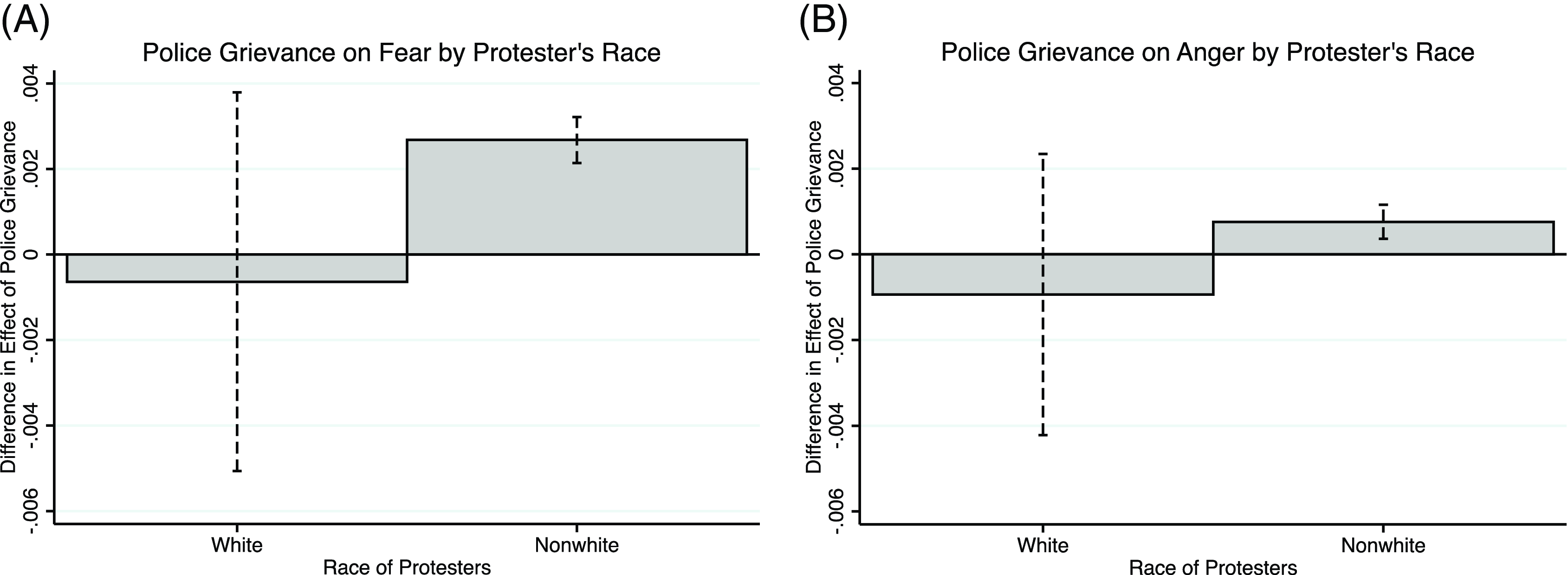

Next, given the prevalence of “police” as a fear-inducing word in non-White protests (see Fig. 1A) and the size and statistical significance of Police Grievance in subsequent analyses, we also employed an additional robustness check analyzing whether the relationship between the tone of media coverage of protest activity specifically about police-related violence, and the race of protesters. To do so, we ran another set of analyses with an interaction between protesters’ race and whether the protest grievance relates to police misconduct.Footnote 11 Figure 5 suggests that non-White protesters receive an additional penalty if the protest is about police violence. Media are more likely to use words that evoke fear and anger for non-White protests if the protest is about police misconduct than if it is not. These differences are statistically significant at the .05 level. In contrast, media appear less likely to use anger- or fear-inducing language when discussing White protests about police misconduct. However, given the few observations of White protests concerning misconduct, the confidence intervals are large, and estimates are not statistically significant at the .05 level.

Figure 5. Sentiment from text analysis of media depictions of protesters based on whether protest grievance is police violence

Note: Figure 5 displays the difference in the marginal effect of fear- (left panel) and anger-(right panel) provoking words given protesters’ race. Estimates are from Models 3 and 4 in Table A3.

Moreover, the marginal effects of protesters’ race on fear- and anger-inducing words based on whether a protest concerns police misconduct suggests that media are more likely to use fear-laden words for non-White protests than White protests when protests concern police misconduct (β = .001, p = .002) or not (β = .005, p = .043). However, there are no statistically significant differences in the use of anger-laden language between non-White and White protests for protests that do (β = .002, p = .174) or do not (β = .001, p = .056) concern police misconduct. The latter difference is only marginally statistically insignificant at the .05 level.

Discussion

Racial disparities pervade news media. Our findings illustrate that news coverage of protest activity is no exception. Coverage of protest activity undertaken by non-White people is considerably more likely to employ words that evoke fear and anger relative to media coverage of protest activity undertaken by White people. These biases hold even when accounting for whether the protests were about police misconduct or a racialized issue, the year, the length of the transcript, and the ideological leanings of the network.

Results depicted in Figs. 2–5 suggest that media’s use of negative sentiments for non-White compared to White protesters is more extreme in their fear-inducing language than anger-inducing language. These findings are intriguing but perhaps unsurprising given the racially biased condemnation of anger. When applied to White people, anger can often be a positive descriptor (Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019). Conversely, the anger and fear generated when viewing non-White protests are likely seen as threatening in a way that feels unfamiliar and uncontrollable (Smith and Ellsworth Reference Smith and Ellsworth1985). Put differently, the involvement of African Americans and other people of color in protest activities increases the likelihood that protests, one of the most democratic forms of political expression, would be characterized in a way that evokes a sense of threat and loss of control.

Perhaps more surprising is the differential use of fear- and anger-invoking sentiments based on the news outlet. There are few differences in media’s use of language evoking anger and fear based on protesters’ race. Moreover, liberal-leaning broadcast networks are more likely to use fear- and anger-invoking sentiments when covering non-White protesters relative to White protesters. These findings could suggest a ceiling effect, where conservatives have no differences in their coverage of liberal protesters. This is to say, perhaps they are inclined to frame any non-traditional political participation for issues opposed to their issue preferences in a negative light. Liberal broadcasters, on the other hand, may express racially biased characterizations of protesters of color, especially Black people (e.g., Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Sniderman and Carmines Reference Sniderman and Carmines1997).

Another possibility for the biased racial coverage among liberal networks involves the nature of news coverage. As our theory suggests, conservative networks rely heavily on outrage speech and language (Sobieraj and Berry Reference Sobieraj and Berry2011), while liberal networks are more likely to use legitimizing language when covering protests (Waldman Reference Waldman2015). For example, one of the most fear-laden news segments in our dataset from MSNBC, the most liberal-leaning network, is Rachel Maddow’s coverage of the Jamar Clark protests on November 25, 2015. An excerpt from the transcript reads:

MADDOW:

… In addition to candle lit vigils and rallies held outside the precinct house in the 4th precinct, last week, there was a confrontational demonstration when 51 people were arrested during a march down Interstate 94. On Wednesday, protesters who police say were throwing rocks were hit by police with high-volume pepper spray.

The timeline since the death of Jamar Clark has, I have to say, followed a similar pattern to the days following other recent police-involved deaths. There‘s enough of these now that there‘s a pattern in terms of community response—the protests, the demand for video evidence, the back and forth between police and protesters, the calls for multiple investigations.

Tensions have been high around the shooting in Minneapolis. Much like they were in Ferguson a year ago and in North Charleston and in Baltimore and in New York and on and on and on

…

In contrast, here is an excerpt from the most conservative network’s most fear-laden news segment. It is Bill O’Reilly of Fox News covering a Black Lives Matter (BLM) protest on August 15, 2016:

(PROTESTERS CHANTING “NO JUSTICE! NO PEACE!”)

O’REILLY: More racial strife this time in Milwaukee on Sunday morning. The “New York Times” ran a headline on his web page saying, quote, “Unrest in Milwaukee after police fatally shoot unarmed man.” That headline was false. The paper has now retracted it. Pointing out that the ensuing article did say the suspect was armed. The man in question, Sylville K. Smith 23 years-old killed by a Black police officer after fleeing a traffic stop on Saturday.

Police say Smith had a gun and they had video to prove it. Smith has a long record with gun involved crimes as well. Now, that incident led to violence in the street in Milwaukee. Businesses were torched. Thirty one arrested so far. Eleven police officers injured. And an 18-year-old shot in the neck by unknown assailant. All in all another awful display in America.

Both news transcripts use fear-invoking words to discuss a majority Black protest. They also emphasize the unrest that ensued. Nevertheless, the O’Reilly coverage relied more heavily on outrage language directed toward the protesters. While these are only two of several hundred transcripts in our data, they highlight broadcasters’ choice to emphasize violence, vandalism, and criminality in coverage of Black protesters. Future research must disentangle the mechanism behind liberal broadcast networks’ use of biased racial coverage to fully discern the role of media in shaping perceptions of non-White protesters and their grievances.

Our findings are robust when assessing how protesters’ grievances concerning police misconduct relate to media’s use of fear- and anger-laden language. Protest grievances concerning police violence increase media’s use of fear- and anger-laden language for non-White protesters but not for White protesters. However, our results are less robust when confining our analyses to the 20 words surrounding describing a protest event. Perhaps, this is because 20 words are arbitrary. The excerpts for the most fear-inducing transcripts from the most liberal and conservative networks are at least 100 words. Notwithstanding, the context-specific robustness check does suggest that fear-laden language is more likely for non-White protesters than White protesters.

While our findings speak to the relative rate at which terms that evoke fear and anger are used when discussing non-White and White protesters, our analyses could not capture the degree of fear and anger induced by the terms. Particularly notable, we could not assess whether the amount of fear and anger induced by the terms describing non-White protesters differed from the amount of fear and anger induced by the terms describing White protesters. For example, the three most common anger-inducing words for White protests were “money,” “politics,” and “vote.” We believe that these terms likely evoke considerably less anger than the three most frequent anger-inducing words in stories about non-White protests—“shot,” “violence,” and “shooting.” We hope future research will explore ways to assess the degree of anger and/or fear induced by the linguistic choices of journalists, as opposed to simply whether the terms are associated with anger or fear at all.

Altogether, our findings demonstrate that media portrayals of protesters vary with protesters’ race and ideological leanings of the media outlet. The findings are quite relevant as protest activity continues. For example, although our data do not include the massive racial justice protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in the summer of 2020, the results help explain some of the patterns that emerged in the wake of this protest activity. The Floyd protests seemed to lead to a meaningful shift in support for racial justice among White Americans (Reny and Newman Reference Reny and Newman2021). The diverse racial makeup of the Floyd protests, with scores of White Americans taking the streets,Footnote 12 likely played a significant role in shaping how media covered the protests, reducing the fear and anger employed in news coverage, at least in the short term.

While our findings present important insights for understanding how news media shape the public’s understanding of protests, they also raise several questions. How do news characterizations of protests and protesters affect trust in the mainstream news media, political efficacy, or the likelihood of engaging in future protest activity—especially when the protesters depicted share a salient identity with viewers? Kilgo and Mourão (Reference Kilgo and Mourão2021) find that negative media frames decrease support for Black civil rights movement protests, identification with protesters, and police criticism compared to media frames legitimating the protests. But, media framing effects may not be uniform across populations. Support for Black Lives Matters issues, like those affecting Black LGBT+ community members, varies with Black people’s sense of linked fate (Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019), gender identification (Bonilla and Tillery Reference Bonilla and Tillery2020), or strength of American identity (Spry and Nunnally Reference Spry and Nunnally2020). Among African Americans, do negative characterizations of protests of mostly African Americans reduce trust in the news media as a reliable source of information or the likelihood of participating in future political demonstrations? Do they contribute to a more general reduction in political efficacy among African Americans? Finally, how do racial disparities in protest coverage affect beliefs in the democratic value of protests among African Americans and White Americans alike? We hope future research will fill this gap for the most recent wave of protest activity.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2023.27

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NZC33J.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the research assistance provided by Avirath Kumar, Pooja Subramaniam, and Seamus Hughes through the University of Michigan’s Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program and by Marianna Garcia. We also appreciate the helpful feedback provided by discussants and participants at the 2019 Critical Observations on Race and Ethnicity (CORE) Conference at the University of California Irvine, the 2018 Midwest Political Science Association meeting, the 2018 Politics of Race, Immigration and Ethnicity Consortium (PRIEC) meeting at the University of California San Diego; the 2017 National Conference of Black Political Scientists meeting, and the University of Michigan Political Communications Working Group. Additionally, we thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable insights and suggestions.

Financial support

This work was generously supported by the Converse Miller Fellowship at the University of Michigan’s Center for Political Studies, and the Black Studies Project’s Faculty Research Grant at the University of California San Diego.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.