Introduction

Social policy developed as a research field and academic discipline to address the social risks arising from capitalist development and industrialization. Today’s welfare states were founded on the premises of economic growth, high levels of employment, and material welfare. However, climate change and related ecological crises challenge these premises by calling into question the ways in which welfare provisioning is organized. Global temperatures are already 1.2° C above preindustrial levels, with the last decade being the warmest decade on record (World Meteorological Organization, 2021). According to the Paris Climate Agreement, countries should take action to keep global warming below 2° C and as close as possible to 1.5° C by the end of this century. However, a recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows that without the strengthening of climate mitigation policies, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are projected to rise after 2025, leading to a median global warming of 3.2° C. Regarding the pathways that would help limit warming to 1.5° C, global net carbon emissions would need to be reduced by 48% in 2030 and by 80% in 2040 (IPCC, 2022b). The magnitudes and forms of climate change mitigation and adaptation constitute an enormous policy challenge in this situation where the atmospheric concentration of GHGs continues to increase, despite a temporary respite due to the COVID-19 pandemic (IEA, 2021; IPCC 2022b). To acknowledge the rapidly escalating climate change situation and to emphasize the urgency of climate policies, scholars (e.g. Gills and Morgan, Reference Gills and Morgan2020) are increasingly using the term ‘climate emergency’.

This climate emergency constitutes a new structural condition for all societies and it is beyond scientific doubt that it also poses significant challenges for the organization of welfare states and social policies. Whereas 20th century social policies were designed to meet the challenges of industrialization, urbanization and globalization, 21st century social policies need to counter the inequalities and conflicts emerging from climate and other environmental policies. Future social policies also need to create synergies between social and environmental goals and help build public support for new sets of ecosocial policies. Echoing the ideas of a ‘green social policy’ (e.g. Fitzpatrick and Cahill, Reference Fitzpatrick and Cahill2002) and the pursuit of ‘decarbonizing welfare states’ (Gough and Meadowcroft, Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011), scholars have begun to explore these issues with a new level of intensity. Discussions of an ‘ecosocial state’ (Koch, Reference Koch2020; Koch and Fritz, Reference Koch and Fritz2014; Laruffa et al., Reference Laruffa, McGann and Murphy2021), an ‘eco-welfare state’ (Gough, Reference Gough2016; Häikiö and the ORSI Consortium, Reference Häikiö2020), a ‘social-ecological state’ (Laurent, Reference Laurent, Laurent and Zwickl2021a), ‘sustainable welfare’ (Gough, Reference Gough2015; Hirvilammi and Koch, Reference Hirvilammi and Koch2020; Koch and Mont, Reference Koch, Mont, Koch and Mont2016) and ‘sustainable wellbeing’ (Gough, Reference Gough2017; Helne and Hirvilammi, Reference Helne and Hirvilammi2015) are key examples of how scholars are seeking to bridge the gap between social policy and sustainability research. There have also been attempts to revise the established corridors of social policy theorizing to align them with an ecosocial policy agenda (e.g. Dukelow and Murphy, Reference Dukelow and Murphy2022; Gough, Reference Gough2017; Hirvilammi and Helne, Reference Hirvilammi and Helne2014; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Gullberg, Schoyen and Hvinden2016). Generally, this literature highlights the need to effect change across everyday life settings in addition to political and social institutions.

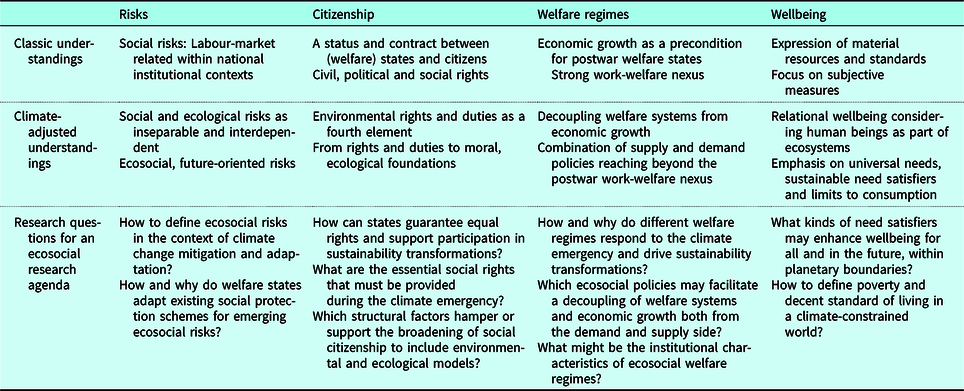

This article contributes to the research on the intersection between social policy and environmental issues by reviewing and discussing the status of social policy scholarship in relation to the climate emergency. Our argument evolves around four well-established research fields of social policy scholarship: risks, citizenship, welfare regimes and wellbeing for outlining future research pathways in the form of an ‘ecosocial research agenda’. We do not contend that these four fields are all encompassing, yet few would doubt that they have prominent positions in social policy research and welfare state practices (Greve, Reference Greve2012). Although the theories and research on risks, citizenship, welfare regimes and wellbeing have been beneficial for conceptualizing and understanding social policies during the age of industrialization, we argue that they require thorough review and substantial revision to capture the context and conditions that influence social policies in the climate emergency age. For these reasons, this article takes stock of the classic conceptualizations in these fields and considers particular climate-related adjustments in light of recent research. To encourage a shift in social policy research, we identify a series of knowledge gaps and research questions that ought to be addressed in the context of the climate emergency.Footnote 1

Risks

Social risks are central in social policy theorizing (Armingeon and Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2007; Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2005) based on the understanding of welfare states as one avenue alongside families and markets for ‘managing social risks’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1999, p. 33). Social risk pooling has informed conceptualizations of welfare regimes and driven explorations of different countries’ social risk management. Much theorizing refers to how external events, conditions or pressures caused social risks (Gough, Reference Gough2015), e.g. how they are linked to changes in labour markets, financial crises or demographies (Harsløf and Ulmestig, Reference Harsløf and Ulmestig2013). Social risks are thus often considered to reflect the exogenous shocks, societal transformation processes and structural changes that drive welfare state reforms.

The distinction between old and new social risks has been a useful heuristic device to capture such exogeneous challenges and the types of groups affected by them. Old risks refer to a ‘loss of earnings capacity due to old age, unemployment, sickness and invalidity’ (Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber, Stephens, Armingeon and Bonoli2007, p. 143), while new social risks constitute the product of postindustrial societies, which are shaped by a global service economy, flexible working conditions and changing family patterns (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2007). Temporary jobs and atypical forms of work have made new social risks more unpredictable, as even individuals with seemingly stable labour market positions can lose their employment and end up in poverty (Koch and Fritz, Reference Koch and Fritz2013). Standing (Reference Standing2018) argues that postindustrialization has given rise to ‘a precariat’ of groups permanently exposed to extensive social risks without access to public safety nets. Apart from temporary risks, persistent deprivation has become a condition experienced by the most vulnerable groups, even in the wealthiest welfare states (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Grotti, Whelan and Maître2021).

Less explored is how climate change is a form of an exogeneous shock. Scholars have only recently started to explore how the climate emergency will impact the nature and distribution of social risks across different parts of a population (see Gough et al., Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Khan, Hildingsson, Koch and Mont2016; Schaffrin, Reference Schaffrin and Fitzpatrick2014). Many countries have already experienced the effects of climate change as altered environments and imperilled or even lost livelihoods. Climate change has intensified wildfires, droughts, floods, and extreme heat worldwide (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Ehrlich, Beattie, Ceballos, Crist, Diamond, Dirzo, Ehrlich, Harte, Harte, Pyke, Raven, Ripple, Saltré, Turnbull, Wackernagel and Blumstein2021). According to the IPCC (2021, p. 11), ‘climate-related risks to health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security, and economic growth are projected to increase with global warming of 1.5° C and increase further with 2° C’. A newer IPCC report on climate adaptation identifies 127 risks due to climate change, many of which can be classified as social risks (IPCC, 2022a). This report points out that in many areas, climate change has already reduced water and food security, affected people’s physical and mental health, increased the occurrence of diseases, impacted settlements, livelihoods, and key infrastructure and increased migration and heat-related mortality (IPCC, 2022a).

It is apparent that the classic concepts do not capture such changes. Gough (Reference Gough2013a, p. 185) argues that climate change is a ‘new all-encompassing social risk’ that could be referred to as a third generation of social risks (Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Khan, Hildingsson, Koch and Mont2016). Climate-driven social risks are less connected to changes in labour markets and family structures and thus require a conceptualization beyond the established work-welfare nexus. While previous social risks (old and new) were visible because they affected an easily defined section of a population, the social risks associated with climate change are less observable, much more complex and have a much more ambiguous effect on a population.

Emerging ecosocial risks can therefore be defined by their ambiguities. One of the IPCC’s key conclusions is that the social risks associated with climate change are both certain and uncertain. We know that they will have effects on human wellbeing, but those outcomes are uncertain, since multiple ‘climate hazards will occur simultaneously, and multiple climatic and non-climatic risks will interact, resulting in compounding overall risk and risks cascading across sectors and regions’ (IPCC, 2022a, p. 18). Ecosocial risks will, moreover, have both direct and indirect effects; extreme weather situations, for instance, will have readily observable impacts, while there will be indirect changes in other regions or societal systems that may be caused by policy responses linked to climate change (Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Khan, Hildingsson, Koch and Mont2016). Climate-generated social risks also differ because they are not tied to changes in national systems and structures and hence nationally delimited; rather, they affect all countries simultaneously – although not necessarily identically – on a global scale (Gough, Reference Gough2013a). For instance, increasing involuntary migration from the countries and regions suffering the most from climatic hazards and slow-onset processes, such as sea level rise or droughts (e.g. Kaczan and Orgill-Meyer, Reference Kaczan and Orgill-Meyer2020; Sedova and Kalkuhl, Reference Sedova and Kalkuhl2020), will increase pressures on other countries’ welfare systems. Hence, climate-driven social risks affect global, national, regional and local levels at more or less the same time.

However, it would be a mistake in our view to suggest that ecosocial risks have replaced any previous risks. Instead, ecosocial risks will occur in addition to the existing social risks to form a complex multilayered structure of old, new, and ecosocial risks; the previous risks will not disappear. For social policy scholars, it will thus be important to further explore how the amplifying effects of climate change may alter existing risk structures and affected groups.

Much evidence already suggests that ecosocial risks lead to new inequalities, new types of distributional conflicts and new forms of injustice, such as those between the segments in a given population, between developing and developed countries and between present and future generations (e.g. Gough and Meadowcroft, Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011). While the previous definition of social risks assumed the existence of a group or collective to bear the burden of risk-sharing, the current understandings of climate change-generated social risks lack clarity due to a greater distance between the observed problems and their causal factors (at least in the Global North). The inequalities that emerge will be all the more intractable because of the indirect and complex nature of the problems at play and the new challenges caused by public mitigation policies. Empirical evidence shows that some green policies, such as pollution taxes, have regressive distributional effects (Büchs et al., Reference Büchs, Bardsley and Duwe2011; Gough, Reference Gough2017). Low-income households already spend a higher proportion of their income on energy-intensive needs, such as heating and cooling, and will thus be hardest hit by a general rise in energy prices (Büchs et al., Reference Büchs, Bardsley and Duwe2011). In this respect, ecosocial risks will most likely amplify existing inequalities. Although their precise effects will differ across countries, sectors and regions, the most vulnerable populations and systems will be disproportionately affected (IPCC, 2022a, 2022b).

This puts pressure on established social protection schemes, which need to cover old and new social risks while finding new ways to capture ecosocial risks and the potentially regressive side effects of decarbonization strategies (Gough, Reference Gough2013b; Büchs et al. Reference Büchs, Ivanova and Schnepf2021). Although social protection schemes have mainly functioned as national policy solutions, they will need to play an additional role in the climate change adaptation of local communities (Johnson and Krishnamurthy, Reference Johnson and Krishnamurthy2010) and in the management of problems across nation-states, such as those linked to climate migration (Schwan and Yu, Reference Schwan and Yu2018). This will be challenging, yet the recent discussion on European unemployment insurance represents a notable case of countries coming together to handle social risks across borders, potentially paving the way for common solutions to ecosocial challenges.

Citizenship

Citizenship studies offer a normative basis for welfare state and social policy measures and provide a general understanding of how the relevant responsibilities and rights are shared between individuals and states. Social citizenship and social rights thus constitute a cornerstone in welfare state theory and comparative social policy research (Lister, Reference Lister2001; Lister et al., Reference Lister, Williams, Anttonen, Gerhard, Bussemaker, Gerhard, Heinen, Johansson, Leira, Siim, Tobio and Gavanas2007; Turner, Reference Turner2001).

Much social policy thinking relies on T. H. Marshall’s ground-breaking essay (Marshall, 1950/1965), and his definition of citizenship ‘as a status bestowed upon those who are full members of a community (Hvinden and Johansson Reference Hvinden and Johansson2007). All those who possess that status are equal with respect to the rights and duties with which that status is endowed’ (1950/1965, p. 18). The distinction between status and practice also signals different approaches to social citizenship. In social policy discussions, citizenship consists of the historically evolved rights as well as the obligations and the possibilities for participation in relation to the state, other citizens, and global actors (Lister et al., Reference Lister, Williams, Anttonen, Gerhard, Bussemaker, Gerhard, Heinen, Johansson, Leira, Siim, Tobio and Gavanas2007). As a status, it indicates that an individual is able to enjoy all the civil, political and social rights that come with a full exercise of the benefits and duties of citizenship (Johansson and Hvinden, Reference Johansson, Hvinden, Evers and Guillemard2013). Citizenship as a practice is about behaving as a citizen and using one’s full potential as a member in society (Häikiö, Reference Häikiö2010).

Recently, the notion of active citizenship has shaped the social policy research on citizens’ relation to society, stressing its republican traits. Active citizenship celebrates citizens who participate in communities, fulfil their responsibilities and make choices in social and health services (Newman and Tonkens, Reference Newman and Tonkens2011). This type of thinking places personal responsibilities and choices before rights (Sointu et al., Reference Sointu, Lehtonen and Häikiö2021). It also places a greater emphasis on how labour market participation is a duty of citizens and the main form of social inclusion (e.g. Laruffa, Reference Laruffa2020).

The climate emergency challenges these models, as they lack an understanding of how citizenship as a status and a practice relates to nature. To consider this relation more fully and thoughtfully, the classical understandings have been challenged by different forms of ‘green citizenship’ such as environmental and ecological citizenship. (delete the rest of the sentence: have broadened the notion of citizenship). Environmental citizenship challenges the established Marshallian rights-based models by emphasizing environmental rights as a potential fourth dimension alongside civil, political, and social rights (Dean, Reference Dean2000). The right to a healthy environment, clean air and fresh water are therefore illustrations of a widened liberal citizenship that retains a focus on human rights. It calls for better regulation of nature as a human right and for a fair distribution of environmental risks, irrespective of class, gender, age, geography, or ethnicity. In contrast, the concept of ecological citizenship challenges the arguments about the moral and normative duties of contemporary citizenship. The responsibilities of individuals are connected to their ecological footprints, which turns citizens into moral actors with a duty to actively respect the needs of others, including nature and other species. Ecological citizenship thus profoundly challenges social citizenship’s nature as a legal status and principle for the provision of material welfare, stressing the moral duties that individuals have to one another and the planet (Dobson, Reference Dobson2003, p. 112).

Despite these important differences, both environmental and ecological citizenship allow blending environmental concerns with theories of social citizenship. They have profound implications (Curtin, Reference Curtin, Isin and Turner2002) because they introduce new normative understandings of citizens’ rights and duties, which are related to the environment, future generations and other species rather than labour markets or families. From a normative standpoint, discussions of these green forms of citizenship highlight how individuals act and participate for the common good (Gabrielson, Reference Gabrielson2008) and reduce their environmental impact (Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Brown and Conway2009). Van Steenbergen’s (Reference Van Steenbergen and van Steenbergen1994, p. 150) idea that individuals, as ‘Earth citizens’, are responsible to nature alongside their fellow citizens and Christoff’s (Reference Christoff, Doherty and de Geus1996) argument that humans are only one species among countless others in a community of ecological citizens follow the same path of reasoning.

This understanding implies a move beyond the state-centric and territorial modes of citizenship. As Wolf et al. (Reference Wolf, Brown and Conway2009) argue, a responsibility that transcends a single territory arises from the asymmetric relation between developed and developing countries and between current and future generations. It evokes issues of intergenerational and international justice. According to the Brundtland Commission’s 1987 definition, the key responsibility of the ecological citizen is ‘to ensure that the impact of an individual fulfilling his or her needs does not foreclose the ability of others, alive now and in the future, to pursue their needs’ (Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Brown and Conway2009, p. 506). What is at stake here is the relevant scale and authority for regulating citizenship rights (and duties) since climate change and its environmental impacts do not respect national borders (Jelin, Reference Jelin2000). This contrasts powerfully with welfare states, which are built on the notion of their national citizens being entitled to certain services and could thus have implications for planning how to consider, for example, the needs of noncitizens from the global South who will seek refuge in welfare states because of climate change. The climate emergency, as a daily reality, is already driving forced displacement on a global scale (e.g. Grandi Reference Grandi2021).

In the climate emergency context, the debate on how to define an accurate future balance between the rights and duties of citizens in relation to states and the rights of other species is still largely missing in social policy research. We expect that this debate will not only have a social policy or environmental orientation but also an integrated ecosocial policy orientation. In addition, new models of ‘eco-social citizenship’ will emerge. Laruffa et al. (Reference Laruffa, McGann and Murphy2021) have begun this discussion in relation to participation and labour. For them, an ‘eco-social policy orientation’ means a broader understanding of participation that ‘recognises the value of re-productive and ecological labour’; it should provide ‘opportunities for people to engage in activities that help to sustain people, the environment and the democratic polis rather than reducing reciprocity to only participating in employment, work experience or training’ (p. 8). In this vision, the ‘practice of taking care of the world’ is a crucial element in ecosocial policy and a key duty of the welfare state. While recognizing the importance of the relations that individual citizens have with their state, other citizens and nature, the emerging notion of ecosocial citizenship addresses a shift in the normative base of social policy.

Welfare regimes

Since Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990), social policy scholars have used a comparative approach to understand the national forms of welfare state regulation with respect to its interdependency with economic growth, referring to them as welfare regimes (Arts and Gelissen, Reference Arts and Gelissen2002; Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Kvist, Marx and Petersen2015). Such regimes vary according to the extent to which welfare systems provide for the institutional protection of workers from their total dependence for survival on employers and on the specific divisions of labour between private and public actors in welfare delivery (known as ‘decommodification’ in Esping-Andersen’s original terminology). What social-democratic, conservative and liberal welfare regimes have in common is a particular work-welfare nexus and a strong connection to economic growth. The postwar welfare-work nexus rested on the recognition of trade unionism and more or less centralized collective bargaining (Aglietta, Reference Aglietta1987). As a result, wages were indexed to productivity growth, while fiscal and credit policies were oriented towards creating and maintaining demand in national economies. Public infrastructure spending and permissive credit and monetary policies enabled economic growth and productivity. Welfare states could use growing tax revenues from the primary incomes of their labour market parties to create, sustain and expand their welfare systems to cover social risks.

The close link between economic growth and welfare state activity remained intact during the transition from Keynesian demand to Schumpeterian supply management models (Jessop, Reference Jessop1999). Welfare institutions were modified and received new functions within the overall structure of the ‘competition state’ (Cerny, Reference Cerny2010). Designed to support competing national and/or local actors in the global economy, social policy itself came to be regarded as ‘investment’ (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2018). ‘Marketization’, ‘refamilialization’ and ‘responsibilization’ are terms describing the diminishing role of state responsibility and the growing role of markets, families and other actors in welfare provision (e.g. Taylor-Gooby et al., Reference Taylor-Gooby, Heuer, Chung, Leruth, Mau and Zimmermann2020). These changes were accompanied by a rescaling process in which key regulatory functions that were formerly carried out at the national level were shifted upwards to transnational (i.e. European) and downwards to regional and local levels (Johansson and Panican, Reference Johansson, Panican, Johansson and Panican2016; Kazepov, Reference Kazepov2010).

The growing awareness of climate change and other environmental problems implied that the internal division of state labour would change. While the welfare state was reregulated and rescaled, the last three decades also witnessed the establishment of the ‘environmental state’. Duit et al. (Reference Duit, Feindt and Meadowcroft2016, p. 5) define the environmental state as containing a ‘set of institutions and practices dedicated to the management of the environment and societal-environmental interactions’, including environmental ministries and agencies, environmental legislation and associated bodies, dedicated budgets and environmental finance and tax provisions and scientific advisory councils and research organizations. Although there are certain parallels between the historical development of welfare states and environmental states, their institutional, political and economic contexts – as well as the compositions of supporting and opposing social groupings and associated ideational constellations – have differed significantly (Gough, Reference Gough2016; Meadowcroft, Reference Meadowcroft, Barry and Eckersley2005).

Esping-Andersen’s welfare regime approach inspired the initial debates on the environmental state and a potential institutional division of labour with the welfare state. Dryzek et al. (Reference Dryzek, Downes, Hunold, Scholsberg and Hernes2003) have argued that social-democratic welfare states are better suited to manage the intersection of social and environmental policies than more liberal market economies and welfare regimes. Rather than trusting the invisible hand of the market, social-democratic welfare regimes and ‘coordinated market economies’Footnote 2 would generally make a ‘conscious and coordinated effort’ and regard ‘economic and ecological values as mutually reinforcing’ (Gough et al., Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008, pp. 334–335). However, the claim that the social-democratic welfare regimes that are least unequal in socioeconomic terms would also perform best in ecological terms and thus gradually become ‘ecosocial’ states has not been verified in comparative empirical research (Duit, Reference Duit2016; Koch and Fritz, Reference Koch and Fritz2014; Jakobsson et al., Reference Jakobsson, Muttarak and Schoyen2018; García-García et al. Reference García-García, Buendía and Carpintero2022). In relation to their ecological and carbon footprints, Western material welfare standards have never been generalizable to the rest of the planet because their environmental impacts transgress the biophysical boundaries of a ‘safe and just operating space’ for humanity (O’Neill et al., Reference O’Neill, Fanning, Lamb and Steinberger2018).

What affects countries’ objective environmental performances the most is not welfare regime affiliation but GDP per capita: the richer a country is, the worse its performance on environmental indicators (Fanning et al., Reference Fanning, O’Neill, Hickel and Roux2022; Fritz and Koch, Reference Fritz and Koch2016). Despite this reality, mainstream policy responses to the climate crisis have been based on the ‘green growth’ idea, which assumes that continued GDP growth can be decoupled from carbon emissions at a sufficient rate to maintain current levels of prosperity and meet decarbonization goals (Hickel and Kallis, Reference Hickel and Kallis2020). However, there is little evidence that an economy-wide decoupling of GDP growth from carbon emissions can occur at a rate sufficient to prevent dangerous climate change (Haberl et al., Reference Haberl, Wiedenhofer, Virág, Kalt, Plank, Brockway, Fishman, Hausknost, Krausmann, Leon-Gruchalski, Mayer, Pichler, Schaffartzik, Sousa, Streeck and Creutzig2021) and even less regarding the possibility of decoupling growth from an unsustainable use of natural resources (Vadén et al., Reference Vadén, Lähde, Majava, Järvensivu, Toivanen and Eronen2020a, 2020b). These inconvenient truths have hitherto mostly been avoided in policy-making, with ambitious programs such as the European Green Deal being founded on an assumption of green growth (European Commission, 2019).

Given the lack of evidence for an absolute decoupling of GDP growth and environmental resource use in any welfare regime, the traditional reliance of welfare states on the provision of growth is being questioned (Corlet Walker et al., Reference Corlet Walker, Druckman and Jackson2021; Hirvilammi, Reference Hirvilammi2020; Koch, Reference Koch2022; Laurent, Reference Laurent2021b). In the existing welfare state arrangements, regardless of regime affiliation, economic growth is a necessary condition for the maintenance of high employment levels and thus the government’s fiscal base. Lower levels of growth would threaten to undermine this base precisely when a welfare state’s social functions to counteract any economic downturn that may accompany social and ecological transformations are required the most (Bailey, Reference Bailey2015).

In the climate emergency context, one of the most important challenges is to make welfare systems independent of economic growth (Corlet Walker et al., Reference Corlet Walker, Druckman and Jackson2021; Koch, Reference Koch2022). Accordingly, recent contributions have begun to reconsider both the supply and demand aspects of welfare provision. Reconsidering the supply aspects of welfare regimes might, on the one hand, require switching funding sources to those that are less affected by economic fluctuations, such as taxes on property, land, financial wealth and inheritance, or necessitate the imposition of taxes on consumption practices with high carbon emissions (Büchs, Reference Büchs2021; Gough, Reference Gough2017). Social policy scholars may also turn to more concrete economic proposals to suggest that maximum incomes are defined as a given multiple of minimum incomes (see Buch-Hansen and Koch, Reference Buch-Hansen and Koch2019). Such changes in the supply aspect of funding welfare systems have been theorized in philosophical ‘limitarianism’ in an ecologically constrained world (Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2019).

On the other hand, scholars have suggested that the demands for welfare could be reduced through an alternative and sustainable ‘political economy of the post-growth era’ (Koch and Buch-Hansen, Reference Koch and Buch-Hansen2021) that features a more even distribution of work, resources and opportunities, greater economic security and improved community and family capacity for social support, care and social participation (Chertkovskaya et al., Reference Chertkovskaya, Barca and Paulsson2019). For example, Büchs (Reference Büchs2021) imagines that while a more even distribution of work and income could facilitate critical participation in society (instead of maximizing human capital and productivity), an associated health policy could help prevent disease and maximize everyone’s chances to lead healthy and fulfilled lives instead of generating productivity and profits for the health care sector. Some scholars (e.g. Goodin, Reference Goodin2001; van der Veen and Groot, Reference Van der Veen and Groot2006) call for a more relaxed attitude towards work requirements in a ‘post-productivist’ welfare regime, while others propose the creation of a massive number of public sector ‘green jobs’ amid a job guarantee by the state (Dietz and O’Neill, Reference Dietz and O’Neill2013; Järvensivu et al., Reference Järvensivu, Toivanen, Vadén, Lähde, Majava and Eronen2018). In general, a shift towards a postgrowth and postproductivist economy requires a new ‘decommodified social policy’ that repurposes active labour measures and fosters the redistribution of work, cash and services (Dukelow and Murphy, Reference Dukelow and Murphy2022). To enable this shift, new kinds of sustainable welfare benefits, such as universal basic income, universal basic services and universal basic vouchers, have been suggested (Bohnenberger, Reference Bohnenberger2020; Coote and Percy, Reference Coote and Percy2020). Irrespective of the precise position taken, all the authors cited above suggest the necessity of revising the typical work-welfare nexus that characterizes established welfare regimes.

The fact that welfare regime affiliation has not yet had any empirically identifiable effect on countries’ objective environmental performances does not rule out the possibility that the institutional potential of social-democratic welfare states to initiate ecosocial policies and, eventually, build sustainable welfare states may simply have thus far been neglected. Attitude studies (Fritz and Koch, Reference Fritz and Koch2019; Otto and Gugushvili, Reference Otto and Gugushvili2020) indicate that since the electorates in Nordic countries are the most prepared to support ‘sustainable welfare’, their governments are, in principle, in the best position to initiate such a policy strategy and could in fact be bolder in that regard. This appears to confirm Taylor-Gooby et al.’s assumption that ‘different traditions, institutions and ideologies of different regimes will produce distinctive attitudinal patterns’ (2020, p. 64). Institutional path dependencies and welfare regime affiliation in particular may effectively characterize the patterns of welfare provision, even in emerging ecosocial regimes (Buch-Hansen, Reference Buch-Hansen2014), because such regimes feature different power constellations, capacities, cultures and influential institutional actors for advancing the sustainable transformation of society.

Wellbeing

According to Hartley Dean (Reference Dean2012, p. 1), social policy fundamentally concerns ‘the study of human wellbeing’. The questions of what constitutes a good life, how to promote wellbeing and which factors threaten wellbeing have been central concerns for social policy scholars since the beginning of the 20th century (Pierson, Reference Pierson2006). Wellbeing has been addressed in terms of subjective wellbeing or happiness and from the perspective of employment, income, and the other material aspects of a decent life. Indeed, one can describe the development of wellbeing research in social policy scholarship as a journey from a resource-based understanding to a more multidimensional perspective. While the emphasis mostly remained on objectively measured material standards of living in the 1970s, the significance of the notion of quality of life with a more subjective and multidimensional perspective has increased since the 1980s. Afterwards, quality of life and wellbeing were thus increasingly approached from the perspective of the capability approach, with a focus on capabilities instead of income levels or other resources (Nussbaum and Sen, Reference Nussbaum and Sen1993). Wellbeing research has also extended its focus from individuals towards a more relational view of wellbeing that emphasizes the significance of social relationships (Deneulin and McGregor, Reference Deneulin and McGregor2010; White, Reference White2017).

However, this focus on social and economic factors has disregarded ecosystems and the relationship between humans and nature. As mentioned in the previous section, none of the existing welfare states has managed to provide for wellbeing within planetary boundaries. This holds true when considering both ecological footprints and the human development index (United Nations Development Programme, 2020) and when examining biophysical boundaries and social achievements (Fanning et al., Reference Fanning, O’Neill, Hickel and Roux2022). Given that the resource use in the Global North benefits heavily from resources that have been appropriated from the Global South (Hickel et al., Reference Hickel, Dorninger, Wieland and Suwandi2022) and that direct resource extraction from ecosystems is one of the main drivers of the world’s biodiversity crisis (IPBES, 2019), it is reasonable to argue that the current state of wellbeing in welfare states has been achieved by deteriorating the wellbeing of impoverished populations, other species, and future generations worldwide. Thus, the policy goal of increasing wellbeing in current welfare states endangers the very foundation of wellbeing from a global justice perspective and over the longer term. This is the paradox that social policy scholars often overlook when celebrating or defending the outcomes of welfare states.

The climate emergency thus entails profound questions regarding the ways in which social policy scholars conceptualize wellbeing and the various welfare policies and practices that aim to produce and protect it (Büchs and Koch, Reference Büchs and Koch2017; Gough, Reference Gough2017). A relational conceptualization of human wellbeing is one step towards sustainability (Helne and Hirvilammi, Reference Helne and Hirvilammi2015). It acknowledges that people are profoundly dependent on ecosystems: they are not separate from nature and cannot survive without its processes, such as the biodiversity of flora and fauna (Kortetmäki et al., Reference Kortetmäki, Puurtinen, Salo, Aro, Baumeister, Duflot, Elo, Halme, Husu, Huttunen, Hyvönen, Karkulehto, Kataja-aho, Keskinen, Kulmunki, Mäkinen, Näyhä, Okkolin, Perälä, Purhonen, Raatikainen, Raippalinna, Salonen, Savolainen and Kotiaho2021; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Mooney, Cropper, Capistrano, Carpenter, Chopra, Dasgupta, Dietz, Duraiappah, Hassan, Kasperson, Leemans, May, McMichael, Pingali, Samper, Scholes, Watson, Zakri, Shidong, Ash, Bennett, Kumar, Lee, Raudsepp-Hearne, Simons, Thonell and Zurek2005). Biodiversity is an important factor in wellbeing because the loss of natural microbial diversity is associated with unhealthy human microbiota and causes a variety of health problems (see Ruokolainen et al., Reference Ruokolainen, Lehtimäki, Karkman, Haahtela, von Hertzen and Fyhrquist2017). A connection with nature also promotes mental health and psychological wellbeing (Martin et al., Reference Martin, White, Hunt, Richardson, Pahl and Burt2020). Since the necessary processes in ecosystems (such as pollination, soil formation and disease regulation) cannot be fully replaced with technological innovations, human life is subordinate to the laws of thermodynamics and ecological processes. In the end, this stark reality sets limits on wellbeing and social institutions, including the economy (Daly and Farley, Reference Daly and Farley2010). Human wellbeing is not only connected to individual life satisfaction and socioeconomic position but also profoundly relates to our need for healthy ecosystems.

Theories of needs have always been part of social policy discussions (Lister, Reference Lister2010). They have recently sparked new interest among scholars occupied by the key questions the climate emergency has produced: What do we all need for a good life? What is the necessary consumption level that ought to be preserved, despite reductions in emissions? Among many established needs theories, the theory of human need by Len Doyal and Ian Gough (Reference Doyal and Gough1991) and the human scale development approach of Manfred Max-Neef (Reference Max-Neef, Ekins and Max-Neef1992) in particular are being increasingly applied in sustainable wellbeing research. Based on these theoretical frameworks, a needs-based research agenda has been promoted (Brand-Correa and Steinberger, Reference Brand-Correa and Steinberger2017; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Buch-Hansen and Fritz2017), and novel research settings with statistical analyses of need satisfiers or participatory citizen forums on the sustainable limits of needs satisfaction have been developed (Koch et al., Reference Koch, Buch-Hansen and Fritz2017; Gough, Reference Gough2020; Guillen-Royo, Reference Guillen-Royo2020; Lindellee et al., Reference Lindellee, Alkan-Olsson and Koch2021). In addition, a need-based having, doing, loving, being (HDLB) framework can be used to conceptualize and empirically investigate multidimensional and relational wellbeing in the context of sustainability transformation (Helne and Hirvilammi, Reference Helne and Hirvilammi2022; Hirvilammi and Helne, Reference Hirvilammi and Helne2014)Footnote 3 .

As outlined by Ian Gough (Reference Gough2017, pp. 45–47), a theoretical understanding of universal human needs is compatible with the context of climate change because human needs are objective, plural, nonsubstitutable, satiable, and cross-generational. Thus, they can provide a solid foundation for social policy on a global scale and for future generations. Unlike preferences or wants, needs imply rights, ethical obligations and claims of justice in social policy institutions. Needs theories also make an important distinction between needs and need satisfiers. Needs are universal, but how we satisfy them is subject to cultural and temporal change. Need satisfiers are not equal to economic goods or artefacts but consist of social practices, subjective conditions, spaces and institutions. They can be more or less tangible and energy intensive and thus have different climate impacts. Classifying them as synergic, negative or inhibiting satisfiers (Max-Neef, Reference Max-Neef, Ekins and Max-Neef1992) may help determine that not all consumption promotes wellbeing and that social policy can have counterproductive effects on needs satisfaction (see Dean, Reference Dean2012). The term ‘satisfier’ therefore sheds new light on the potentially sustainable ways that needs can be met in practice, leading to the conclusion that sustainability transformation is not about impairing our needs as such but about changing our need satisfiers.

Wellbeing research in current welfare states is carried out in societies where most of the population is not suffering from a lack of necessities. The climate emergency, however, entails a reassessment of basic issues such as food, housing, energy and water security, even in prosperous welfare states. Poverty is not merely a shortage of financial resources or an absence of capabilities but is also felt as a shortage of energy or functioning ecosystem services. This calls into question the established ways of defining adequacy and poverty thresholds by depicting deprivation items, necessities or reference budgets (e.g. Deeming, Reference Deeming2017; Saunders and Naidoo, Reference Saunders and Naidoo2009) without paying attention to their environmental impacts. A social policy that ensures a standard of living that is both socially and ecologically sustainable needs to account for critical biophysical boundaries. This is the purpose of the studies on ‘decent living standards’ that identify the essential requirements for wellbeing (nutrition, health, shelter, etc.) and use them to assess necessary energy requirements (Kikstra et al., Reference Kikstra, Mastrucci, Min, Riahi and Rao2021; Rao and Min, Reference Rao and Min2018). In addition, the concept of a sustainable ‘consumption corridor’ – i.e. the space between the acceptable minimum and maximum standards of living – has been suggested (Di Giulio and Fuchs, Reference Di Giulio and Fuchs2014; Sahakian et al., Reference Sahakian, Fuchs, Lorek and Di Giulio2021). In welfare states where the consumption-based emissions of an average citizen are far from meeting the 1.5° C target (Akenji et al., Reference Akenji, Bengtsson, Toivio, Lettenmeier, Fawcett, Parag, Saheb, Spangenberg, Capstick, Gore, Coscieme, Wackernagel and Kenner2021), regulating consumption in a way that also considers the need for socially acceptable participation in a given society becomes a relevant focus for social policy research.

Towards an ecosocial research agenda

Our review of welfare state and social policy research in the climate emergency context has allowed us to identify and explore the classic and climate-adjusted understandings of the four selected fields. Table 1 summarizes both types of understanding and formulates research questions for an ecosocial research agenda (Table 1).

Table 1. Understandings and research questions for an ecosocial research agenda

The climate emergency entails the question of whether there will be a new and distinctive generation of risks for human wellbeing. The ongoing climate-related risks have been found to be less observable and more diffuse than the previous generations of social risks, with more ambiguous and often indirect effects on populations and impacts reaching beyond national borders and lasting for much longer periods of time. However, the nature of climate-generated risks and their interplay with the older risks has not yet been addressed in any depth by social policy scholars. We therefore propose approaching climate-generated risks as ecosocial risks whose social and ecological aspects are regarded as inseparable and interdependent. In a genuine contribution to social science-based climate change research, social policy scholarship could explore the ways to further conceptualize the entanglements of these risks and reveal new patterns of insecurity that correspond to these entanglements. More empirical research is needed to provide in-depth knowledge for policy-makers on the new inequalities emerging in the climate emergency context and as a consequence of green transition policies. We encourage studies of how existing welfare states cope with such ecosocial risks and the kind of policy solutions that these may require.

Citizenship has traditionally been conceptualized as a status and contract between state and citizen, with recent developments emphasizing the ‘active’ element of citizenship and corresponding duties, especially regarding labour market participation. Notions of environmental and ecological citizenship have introduced new normative understandings of citizens’ rights and duties related to the environment, future generations and other species. The climate crisis calls for a broadened, noncontractual and nonterritorial way of understanding citizenship. A key question, then, is how states may guarantee equal rights and support participation for all in their sustainability transformations. Additional research objects include how these may impact the balance of citizenship rights and duties and how this relates to the design of social policies. For instance, it is an open question regarding what happens to active labour market policies once the conditions of social protection reflect notions of ecosocial citizenship due to loosened labour-market related conditionality and a closer connection to societal participation – understood in more general ways, including the currently unpaid activities for the care and caretaking of the environment.

All postwar welfare regimes rely on economic growth as a fundamental condition for maintaining their welfare state. While GDP growth is an important precondition for maintaining the current forms of welfare provision, it is also strongly linked to GHG emissions. A first necessary question for a research agenda that reflects contemporary concerns is thus how the maintenance of welfare systems can be decoupled from growth on both the demand and supply sides. More generally, social policy scholars may explore how different welfare regimes respond to the climate emergency. The ecosocial research agenda could begin with the hypothesis that welfare regimes and institutional path dependency may not be simply explanatory factors for current environmental performance but points of departure for different countries to begin their trajectory towards an ecosocial welfare regime that manages to respect planetary boundaries in a postgrowth context. There is also a gap in research in regards to what constitutes ecosocial policies and their likely impacts and transformational capacities. For example, working time reduction, job guarantees, or green vouchers are often proposed as ecosocial policy solutions, yet scholars need to further clarify what criteria and methods can be used to distinguish ecosocial policies and to evaluate if they allow countries to provide welfare within planetary boundaries.

The wellbeing research has focused on social and economic factors, but the relationship between humans and nature and the role of ecosystems have typically been neglected. The paradox, often overlooked, is that the goal of increasing wellbeing in the short term and within current national welfare state settings tends to endanger the very foundation of wellbeing globally and over the longer term. We support recent calls for a more relational conceptualization of human wellbeing that includes the relationships between humans and nature and thus acknowledges the dependency of human wellbeing on ecosystems. This is also reflected in increasing interest in theories of human needs and the emphasis on needs satisfaction within planetary boundaries. Social policy scholarship should thus ask how human needs may be satisfied in a sustainable manner, what may constitute a ‘good life’ in the context of decreasing emissions, and how a socially and ecologically sustainable standard of living may be achieved for all human beings, today and in the future.

In general terms, this ecosocial research agenda builds on the notion of a double bond between the welfare state and environment. While the relationship between states and markets has been central in welfare and social policy research for decades, an ecosocial research agenda places the interplay between welfare states and the environment at the centre to inform future welfare and social policy research. This requires new theoretical frameworks and novel research methods that integrate environmental impacts with more traditional socioeconomic factors such as income, employment, housing, and life satisfaction. Methods for considering the environmental impacts of economic growth along with the impacts on employment and income distribution need to be developed to establish more sustainable indicators that measure the outcomes of welfare states. In addition, new kinds of macroeconomic modelling and simulation are needed to discern the potential pathways towards ecowelfare states and to assess what policies different welfare regimes could adopt to respond to the climate emergency (see D’Alessandro et al., Reference D’Alessandro, Cieplinski, Distefano and Dittmer2020).

We have discussed the four focal research fields separately because the aim of this article is not to provide a comprehensive understanding of the interconnections between risks, citizenship, welfare regimes and wellbeing. Nevertheless, future research should try to construct a holistic picture of how these fields are interlinked to understand their synergies and prevent potential trade-offs in policy recommendations. The ecosocial research agenda requires a systemic understanding of the interconnections between the emerging risks, changing responsibilities of citizens, reforms in welfare institutions and material limits of sustainable wellbeing. When ‘system transformations’ are called for (IPCC, 2022b), an ecowelfare state cannot be achieved without an integrated approach to policy-making.

Conclusion

In this study, our novel perspective is the assumption that increasing awareness of the climate emergency is likely to influence and transform the interpretations of key research fields in social policy scholarship. While the fields in social policy research other than the four selected here are certainly worth exploring in future studies, we have addressed both traditional and climate-adjusted understandings of risks, citizenship, welfare regimes, and wellbeing.

Our review of these concepts shows that shifting the focus in social policy research towards an emerging ecosocial agenda differs from mainstream research in – at least – the following four ways. First, it suggests that in a world shaped by the climate emergency, the focus in research should be on welfare state transformation rather than ‘conservatism’. Avoiding a repetition and reinforcement of the illusions of ‘green growth’, an ecosocial research agenda takes the limits on growth seriously, studies the complex ways in which the existing welfare institutions are connected to the growth dependency of current welfare states and develops policy pathways for decoupling wellbeing outcomes and economic growth. Second, the ecosocial research agenda puts forward broader notions of wellbeing by considering the relationship between humans and nature and the multiple dimensions of needs satisfaction. Third, its focus extends beyond the dominant nation-state bias in social policy research and emphasizes that the principles and issues of global justice and redistribution are the starting points for new policy solutions. Fourth, the ecosocial research agenda conceptualizes risks in both social and ecological ways and advances the corresponding notions of citizenship.

Our review thus indicates the multiple ways in which the climate emergency challenges many of the fundamental premises that social policy research has relied on since its origins. Given that economies and society, including welfare states, must decarbonize quickly, social policy researchers would be well advised to focus on both the ecologically problematic aspects of its core concepts and the potentially important roles that welfare systems could play in sustainability transformation. It is indeed difficult to imagine that climate mitigation and a broader kind of sustainability transformation will leave welfare states untouched or take place without the involvement of welfare institutions and policies. Moreover, increasing climate risks suggest that the significance of redistributive social security and public services might be greater than ever during such a transformation. One of the specialized fields in climate-adjusted social policy research should thus deal with the corresponding reforms of welfare institutions and policies to ensure that they are capable of supporting and promoting sustainable wellbeing globally and across generations.

Acknowledgements

Tuuli Hirvilammi, Liisa Häikiö and Johanna Perkiö are supported by The Strategic Research Council (SRC) at the Academy of Finland research project “Towards EcoWelfare State: Orchestrating for Systemic Impact (ORSI)” (grant no. 327161). Håkan Johansson’s participation has been funded by FORMAS under the project grant number of 2016-00340, and the project “The new urban challenge? Models of Sustainable Welfare in Swedish metropolitan cities”. Max Koch benefited from funding from the Swedish Energy Agency (Energimyndigheten) [grant no. 48510-1] and Lund University’s research programme for excellence, focusing on Agenda 2030 and sustainable development (project “Postgrowth Welfare Systems”). Sincere thanks to the participants of the ECPR Joint Session Climate Change and the Eco-Social Transformation of Society (2021) and the reviewers for useful comments on the earlier draft.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.