Collective violence, in which communities are mobilized to harm identifiable civilian populations based on categorical group membership (Straus Reference Straus2015, 17), remains a threat to peace and security worldwide. Regarding how communities come to engage in such violence, trial judgments in international criminal law have given an outsized role to the direct influence of hate propaganda (for a review, see Badar Reference Badar2016; Wilson Reference Wilson2017), an umbrella term for speech crimes ranging from persecutory speech to direct and public incitement to commit genocide (Fino Reference Fino2020, 37-39). Many scholars have likewise stressed that hate propaganda (propaganda, henceforth) can increase the chances that populations will participate in, or tacitly support, outgroup persecution (Smith Reference Smith2020; Thompson Reference Thompson2019; Wilshire Reference Wilshire2005). Others have found that collective violence results from ideologies of ingroup superiority (Goldhagen Reference Goldhagen2009), cultures of annihilationism (Hinton Reference Hinton2004; Mamdani Reference Mamdani2001), social pressures (Browning Reference Browning1998; Williams and Buckley-Zistel Reference Williams and Buckley-Zistel2018), obedience to authority figures (Milgram Reference Milgram1974), or sadistic psychological predispositions (Waller Reference Waller2002).

Although propaganda often precedes collective violence, the causal connection between the two remains opaque. Beyond experimental studies that demonstrate the negative effects of hate speech on intergroup perceptions (Kiper, Gwon, and Wilson Reference Kiper, Gwon and Wilson2020; Olteanu et al. Reference Olteanu, Castillo, Boy and Varshney2018; Soral, Bilewicz, and Winiewski Reference Soral, Bilewicz and Winiewski2017), there is surprisingly little empirical evidence that propaganda significantly contributes to collective violence. Recent speech crime trials have attempted to bridge this gap by establishing a causal-link between a propagandist’s intentions and the proximity of his message(s) relative to acts of community-wide perpetration (Wilson Reference Wilson2017). While these legal developments have resulted in convictions (for a review, see Timmermann Reference Timmermann and Dojčinović2020), they have been criticized for relying on outdated theories of social influence and neglecting the wider views of targeted communities (Clark Reference Clarke2015; Wilson Reference Wilson2017).

Genocide scholars have attempted to address these problems by examining how the histories of violence written by legal authorities, such as international criminal tribunals, compare to culturally local narratives (Fujii Reference Fujii2009; Straus Reference Straus2015). Although such investigations have been undertaken in post-conflict Cambodia and Rwanda, and several works have addressed propaganda and war in the former Yugoslavia (e.g., Halilovich Reference Halilovich2013; Ramet Reference Ramet2005; Sokolić Reference Sokolić2016), few have investigated the collective and individual accounts of both former combatants and survivors from different sides of the Yugoslav Wars. This is remarkable considering that the Yugoslav Wars – like the Rwandan genocide – are often used as historical case studies of propaganda causing collective violence (for a review, see Kiper Reference Kiper2015a).

Accordingly, this article is motivated by two empirical questions. How do memories of propaganda and other causes of collective violence vary across the former Yugoslavia today? And what can they tell us about theories of propaganda and collective violence? I address these by first discussing the problem of propaganda as it has come to light in recent speech crimes trials, and then focusing on findings that inform current debates on propaganda and collective violence. I then discuss my ethnographic fieldwork with former combatants and survivors of the Yugoslav Wars in post-conflict regions of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia, and thereafter detail various models of what is remembered as causing collective violence based on survey data (n = 780) and ethnographic interviews (n = 139). Results indicate that propaganda is remembered as playing an indirect and secondary role to the imposition of state-sponsored ethnicity and other regional wartime factors. While these findings do not adjudicate between competing accounts of events, they break from the prescribed narratives in international law and provide what I will argue is trustworthy data that contribute to current debates on ethnonationalism, criminal speech, and atrocity prevention.

The Causal-Link between Propaganda and Collective Violence

Central to international speech crime trials, where an accused is said to have incited, instigated, ordered, or persecuted a recognizable civilian population through publication(s), broadcast(s), or public speech(es), is the dual assumption that words are actions in a causal chain of events and thus increase the likelihood of an audience acting on a speaker’s intentions (Dojčinović Reference Dojčinović and Dojčinović2012; Wallenstein Reference Wallenstein2001). While evidence of consequential violence is unnecessary for prosecuting incitement to genocide, courts since the Rwandan genocide have adopted a consequentialist framework for connecting propaganda to collective violence (Fyfe Reference Fyfe2017; Wilson Reference Wilson2016). Combining speech acts theory and law, this framework can, respectively, be summarized as follows (Wilson Reference Wilson2017). If collective violence was intended (illocutionary force/mens rea), and the audience could carry it out (felicity conditions/causal-link), then subsequent violence is evidence of propaganda’s influence (perlocutionary effect/actus reus).

At the most recent speech crime trial, for instance, Vojislav Šešelj, a radical Serbian nationalist, was convicted of persecution, a crime against humanity, for his public speeches during the Yugoslav Wars. His intentions, first and foremost, were evident in repeated public threats such as statements that Bosnia would flow with “rivers of blood,” that Serbs had to defend themselves from “Ustasha and pan-Islamist hordes,” and that Serb fighters should “clean [expel non-Serbs from] the left bank of the river Drina” (MICT-16-99, Judgment Summary, 26-27). Based on heightened ethnic tensions at the time, judges reasoned that “such statements [were] undoubtedly capable of creating fear and emboldening perpetrators of crimes against the non-Serbian population” (MICT-16-99, Judgment Summary, 26). Effect was inferred from the consequences of Šešelj’s statements such as his notorious speech at Hrtkovci, Vojvodina, where he called on a crowd of far-right supporters to “drive out” Croats, which was followed by Croats and non-Serbs fleeing or being expelled from Hrtkovci (MICT-16-99, Judgment Summary, 31).

Critically, this decision, like others before it, was based on precedent-setting trial judgments and expert reports (see Dojčinović Reference Dojčinović and Dojčinović2012, Reference Dojčinović2020; cf. Des Forges Reference Des Forges1999; La Brosse Reference La Brosse2003; Oberschall Reference Oberschall2006) at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). In those trials, three theories were used to establish the felicity conditions or so-called causal-link between propaganda and collective violence. Felicity conditions here mean audience uptake such that a propagandist’s message was well-formed enough that the targeted audience understood the speaker’s intentions and could carry them out (Dojčinović Reference Dojčinović2020, 189-191). The three theories used to determine such felicity conditions were the ethnic fear thesis: that an audience whose identity centers on ethnicity is prone to fears about neighbors who are ethnic others; the ethnic hatred thesis: that if those neighbors and the audience share a history of strained social relations or conflict, then the audience is vulnerable to developing or renewing ethnic hatreds (Fujii, Reference Fujii2009, 4; Oberschall Reference Oberschall and Dojčinović2012, 188), and the hypodermic-needle thesis: that if a propagandist encouraged ethnic hatreds and called on the audience to harm their ethnic neighbors, his propaganda was like a hypodermic-needle, infecting the audience with shared persecutory intent and contributing to subsequent persecution (see Prosecutor v. Akayesu, 104, 349, 673, 675, 1017). Taken together, the presence of ethnic fear, ethnic hatred, and propaganda approximate to any collective persecution was sufficient to prove the felicity conditions and, thus, an apparent causal-link in speech crime trials.

Shortcomings of the Causal-Link

These developments, albeit leading to convictions of notorious warmongers, have been highly criticized by legal scholars and social scientist. Many argue that the causal-link, as it is currently understood, is an instance of post hoc ergo propter hoc reasoning, because it ultimately posits that in a particular context, if collective violence follows propaganda, then the latter caused the former, which is fallacious (Wilson Reference Wilson2017, 44-45). Critics similarly point out that the above background theories, which inform the causal-link, are outdated. The hypodermic-needle theory, for example, is based on the behaviorist view that propaganda metaphorically infects recipients against their will, which is at best a myth and at worst a strawman fallacy (Lubken Reference Lubken, Park and Pooley2008; although the metaphor is arguably apt for propaganda on social media). Furthermore, all three background theories advance claims that can be tested empirically in the form of testimony that audiences, in fact, categorically feared or hated the community of their would-be victims and that propaganda motivated their persecution (see Fujii Reference Fujii2009, 119). Yet, evidence in the form of testimony is perhaps the greatest shortcoming of speech crime trials. Most witnesses against propagandists at the ICTR and ICTY retracted their testimony due to intimidation or outright threats while others consequentially refused to testify (Wilson Reference Wilson2017, 120-123). For instance, dozens of witnesses retracted their testimony against Šešelj, including 14 whose identity was compromised by Šešelj himself (Džidić Reference Džidić2018).

One way to address this problem, as proposed by linguistic experts at The Hague, is to demonstrate uptake indirectly through semantic transmission from propagandist to perpetrator, where uptake is evident when an audience repeats the justificatory semantics of the propagandist. In the case of the former Yugoslavia, Dojčinović (Reference Dojčinović and Dojčinović2012) notes that such conceptual structures were slurs used by propagandists to foment ethnic hatreds such as “Ustasha,” “Turk,” and “Shqiptar” or emically justified violence such as the nationalistic “Karlobag-Ogulin-Karlovac-Virovitica” line or border for a Greater Serbia, free of non-Serbs. Because these concepts informed commitments to persecute civilians from perceived Serbian territories (Prosecutor v. Šešelj, Case No. IT-03-67-R77.2), a person repeating them, especially when justifying or accounting for wartime behavior, would demonstrate a semantic feedback loop (Dojčinović Reference Dojčinović and Dojčinović2012, 95). This method of tracking semantic transmission would have been ideal for evaluating possible speech crimes in Serbia, the Republika Srpska, and Montenegro by national war crimes prosecutor’s offices. However, Kiper’s (Reference Kiper2015a) interviews with war crime prosecutors in Belgrade revealed that by 2010, prosecutors there had no intentions of interviewing former combatants or survivors, and instead would rely on the proximity of propaganda and collective violence to prove cause-and-effect.

Post-Conflict Investigations

These developments and criticisms compelled researchers to undertake post-conflict studies in Rwanda, where it was found that contrary to the ICTR, Hutu propaganda, such as the notorious “Hutu hate radio” (RTLM), functioned less as a motivator for genocidaires and more as a military-broadcasting system for fighters who were long prepared for violence against Tutsis (Li Reference Li2004; Danning Reference Danning2018). Many perpetrators also reported that they were rarely exposed to RTLM but instead were motivated by social pressures from peers, a finding corroborated by multiple post-conflict investigations in the region (Mironko Reference Mironko and Thompson2007; Straus Reference Straus2007). Despite these findings, it is still the case that regional broadcast coverage of RTLM correlated with a 9% increase in genocide (Yanagizawa-Drott Reference Yanagizawa-Drott2014). These results have entailed that post-conflict investigators should not only interview perpetrators but take community-wide narratives into account (Kiper Reference Kiper2015a).

Arguably the most influential study to do so was by Lee Ann Fujii (Reference Fujii2009), an anthropologist who interviewed 231 Hutus and Tutsis across Rwanda, finding that most people, on both sides, reported being influenced by state-sponsored ethnicity. This is when an ethnic identity, such as being Hutu or Tutsi, which appears salient to outsiders, such as criminal investigators, was rather negligible to insiders just prior to the collective violence in question. However, ethnicity became exaggerated and imposed on persons by local elites for political gain; and with the onset of a political crisis, it became the main source of community-wide perceptions of “us” and “them.” Still, when Fujii took a more granular approach to interview data, she found that secondary local-factors contributed more directly to violence. These included fears about Tutsi neighbors resulting from legacies of past violence and renewed conflicts; jealousies against individual neighbors and using the pretext of war as a justification for personal revenge; a logic of contamination by which violent individuals or groups influenced otherwise peaceful Hutus; perturbations in economic decline which motivated some to profit from violence; rumors about Tutsis which prompted preemptive killings or avoidance of neighbors; strategies for survival such as Hutus going along with violence so as not to become targets themselves; and coercion in the form of strong or moderate pressure from peers, local elites, or other genocidaires. These findings overlap with those found by Straus (Reference Straus2007, Reference Straus2015) who interviewed 200 perpetrators but also investigated the political actions of Hutu leaders, finding that the latter were motived by utopian regime narratives and desperation during degenerative warfare.

Although these post-conflict investigations have informed present-day genocide studies (Williams and Buckley-Zistel Reference Williams and Buckley-Zistel2018), they have nevertheless been criticized for relying on first-person reports that reveal more about participants’ dynamic social identities than historical events. Admittedly, while a degree of perspectivism is unavoidable in post-conflict studies, it is not equivalent across participants. Zaromb et al. (Reference Zaromb, Butler, Agarwal and Roediger2014), for instance, found that persons who experienced conflicts first-hand demonstrate significantly greater collective accuracy when recounting events compared with persons who learned about such events second-hand and thus share a consensus based on collective memory. Reversing the criticism, judicial truth-seeking often excludes cultural or insider narratives because they challenge the arbitrative accounts produced by courts (Rauschenbach Reference Rauschenbach2018). This exclusion, however, is often at the cost of a holistic picture of historical conflicts (Kaye Reference Kaye2014). Additionally, recent media studies suggest that propaganda may have distinct effects on different audiences, such as the ingroup, outgroup, and third parties (Olteanu et al. Reference Olteanu, Castillo, Boy and Varshney2018), which often get overlooked by the legal focus on perpetrators.

In sum, speech crime trials have advanced claims that reflect and continue to inform ideas about propaganda and collective violence. However, if those claims are true, there must be extant evidence for them. Following post-conflict scholars, I adopt the following thesis: if ethnic fears, ethnic hatreds, or propaganda drove participation or support for violence during the Yugoslav Wars, we should find evidence of these in former combatants and survivors’ statements about the period (Fujii Reference Fujii2009, 119; Dojčinović Reference Dojčinović2020, 180-184). Although post-conflict statements are retrospective explanations, they are taken by anthropologists to be revealing of the logics of violence when triangulated with other ethnographic data (e.g., Hinton Reference Hinton2004; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2003). Insofar as I investigate these matters in former conflict regions of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia, I now turn to a brief characterization of the overall ethnographic context.

Post-Conflict Regions of the Former Yugoslavia

From 1991 to 2001, the former Yugoslavia fell into a decade-long civil conflict in which irredentists clashed with Serbian nationalists over succession from Yugoslavia, resulting in insurgencies and sieges in Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia Herzegovina, and Albania. The outcome was a devastating series of wars characterized by collective violence, including over 140,000 persons killed, 50,000 women raped, and two million refugees (International Center for Transitional Justice 2020; Kiper and Sosis Reference Kiper and Sosis2020, 50). Soon after Yugoslav succession, the ICTY was established by Resolution 827 of the UN Security Council to prosecute genocide, crimes against humanity, and violations of the customs of war, including grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions. All together 161 persons were indicted by the ICTY, and of these 26 were indicted for speech crimes (Kiper Reference Kiper2018, 25). The ICTY gave propaganda such a large explanatory role in causing collective violence that media scholar Susan Caruthers (Reference Carruthers2000, 46) concluded that “Every person killed in this war was killed first in the newsroom” (as cited in Wilson Reference Wilson2017, 1).

Yet few post-conflict ethnographies have attempted to assess empirically the remembered effects of propaganda and other causes of collective violence during the Yugoslav Wars. The former Yugoslavia included seven present-day countries, but my focus here is solely on communities in Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Serbia, where numerous crimes against humanity occurred. Each country today recognizes its own official language, although Croatian, Serbian, and Bosnian are mutually intelligible (Okey Reference Okey2004). The political divisions over language are related to ethnonational divisions (Kamusella Reference Kamusella2008), rendering many words and phrases loaded with identity-centered undertones. To circumvent conflictual names over combatants (Kiper Reference Kiper2018), I use former combatant for any exfighter, and survivor for any non-combatant who survived the conflicts, endured discriminatory policies, or lived in combat regions during the wars. While this binary category often breaks down for individuals, it is routinely used as a convenience for making population inferences (Scandlyn and Hautzinger Reference Scandlyn and Hautzinger2015). I also use collective violence instead of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or mass-atrocity crimes because it connotes a more neutral and interregional recognition of wartime violence.

In prior qualitative interviews (Kiper Reference Kiper2015b, Reference Kiper2018), I found that former combatants and survivors talked about collective violence differently. Most former combatants centered their explanations on self-defense, social pressures, and frontline rumors, while survivors and the greater populations focused on the role of propaganda. From my first ethnographic fieldwork in the Balkans in 2005 to my present-day involvement in reconciliation between Yugoslav war veterans (Kiper Reference Kiper2019; see Supplement for images), I have observed that wartime experiences also influence people’s post-conflict views, including about propaganda. For instance, Croats and Bosniaks often reflect on their consternation at hearing inflammatory speeches by Serb nationalists, while Serbs tend to focus on misleading news reports that aired on Yugoslav television. These variations inclined me to expect that accounts would not only vary between former combatants and survivors but also across regional and country lines.

Despite speaking the language and having trusted informants, I undertook this research when war crimes investigations were still ongoing in the region. Thus, it was often necessary for me to do extensive, preliminary fieldwork at local war veterans’ organizations to build rapport with former combatants and to convey cultural intimacy (Subotic and Zarakol Reference Subotic and Zarakol2012). Recurrent observations in my fieldnotes describe the unfolding social and narrative contexts of this research which parallel observations made by others (for more regional information, see Supplement). For instance, most participants felt disquieted about the past and disgruntled or highly pessimistic about local politics. Many Croats and Bosniaks expressed neutrality or support for the United States or the European Union (EU), while most Serbs expressed distrust or dislike for the EU, United States, or NATO (Milačić Reference Milačić2019). Many older Serbs were Yugonostalgic while older Croats were generally skeptical about Tito’s reign (Bošković Reference Bošković2005). Several younger participants criticized traditional patriarchy or media effects in the region, while many former combatants expressed concerns over progressive politics and communicated masculine values (Greenberg Reference Greenberg2006). Nationalism, although varying strongly across localities, was also visibly stronger in rural areas compared with urban centers (Hayden Reference Hayden2014).

To the best of my knowledge, this article is the first multi-sited, post-conflict ethnography to examine the present-day collective and individual memories of both former combatants and survivors as they relate to ideas of propaganda and other causes of collective violence. Insofar as propaganda is considered a significant causal factor of collective violence, accounts ought to reflect this directly or indirectly. Determining this much requires various models of collective violence and measuring the degree to which propaganda is significant compared with other remembered influences. I, therefore, triangulate sources by using a combination of survey instruments and interviews to determine whether and how people from various regions remember propaganda as contributing to crimes against humanity in the Yugoslav Wars.

Study

Methods

A multi-sited ethnography was chosen because it offers one of the most reliable methods for identifying shared social determinants of distinct cultural outcomes such as health, disease, and war. For instance, ethnographers routinely use participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and surveying among participants after an outbreak to identity relevant social factors impacting the spread of the disease and regional health outcomes (Molloy, Walker, and Lakeman Reference Molloy, Walker and Lakeman2017). Post-conflict ethnographers have borrowed these methods to determine the most likely factors that contributed to collective violence across communities of regional warfare (e.g., Fujii Reference Fujii2009; Hinton Reference Hinton2004; Li Reference Li2004). As I articulate below, the strengths of this method are that it yields statistically robust data for analyzing regional and community-specific accounts that can be compared between emic (insider) and etic (outsider) perspectives within and between conflicts. The weaknesses include the problem of conflating memories with collective narratives and the risk of skewed inferences based on biased sampling. To address these, my analyses draw from a large sample of regional, community-specific, and former combatant and survivor accounts, but also surveys and interviews that comprise nearly one-thousand data points.

The survey (N = 780) consisted of several instruments, including demographic and religiosity questions, a self-assessment of memory, and a survey about collective violence during conflicts. For maximum clarity, the survey was translated into a variant of Serbo-Croatian in each country with the help of local assistants, and then back-translated into English. Demographic variables included age, yearly income, years of secondary and higher education (srednja škola i visoko obrazovanje), political orientation toward right-wing nationalism, a religiosity index (Koenig and Büssing Reference Koenig and Büssing2010), and a self-assessment of semantic and episodic memory. To assess collective violence, participants rated 11 statements on a five-point Likert scale about what influenced people during the Yugoslav Wars. Each statement was based on prior field-research from 2010 to 2012 and overlapped with causal-factors identified by previous post-conflict studies such as Lieberman’s (Reference Lieberman2006) factors for national hate and Oberschall’s (Reference Oberschall and Dojčinović2012) crisis-frame factors.

During prior field research, I found that participants generally understood crimes against humanity, war crimes, and widespread persecution or attacks on civilian targets as collective violence (kolektivno nasilje). Moreover, former combatants indicated that, while they were willing to speak generally about collective violence, they preferred to identify participatory causes thereof in an anonymous survey. Thus, surveying why persons engaged in collective violence was an appropriate measure and supported by preliminary fieldwork.

To explore how results clustered regionally, I first conducted a principal components analysis (PCA) of survey data with oblique rotation to reduce variables to single factors, using R. Factors with eigenvalues above 1.0 were used to create binary logistic regression equations to predict former combatants’ and the greater populations’ characteristics and views about collective violence. So as not to lose the granularity of results, I then conducted separate binary logistic regression equations for each country, using backward selection from the full model of focal variables. Using corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc; Mazerolle 2020) statistics, I determined which models had the best fit for former combatants and the greater population of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia.

In addition to survey data, I analyzed a separate set of semi-structured interviews (N = 139) conducted with former combatants and survivors from former combat regions in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia. Interviews centered on questions about what contributed to collective violence in the wars. To analyze results, I used grounded theory to identify shared accounts. For sake of brevity, I focus here on what participants remembered as influencing themselves or others to support or actively participate in campaigns, policies, or activities that resulted in collective violence (see Supplement for survey, interview guide, and analytical notes).

Participants

Local assistants and I distributed surveys and conducted interviews during intermittent fieldwork sessions from 2012 to 2016. Most of the research was done over an 18-month period from 2014 to 2016 in the Serbian cities of Belgrade and Kikinda; the Bosnian-Herzegovinian cities of Banja Luka, Sarajevo, and Mostar; and the Croatian cities of Zagreb, Karlovac, Sisak, and Vukovar.

For the survey, most former combatants were sampled from 11 veterans’ organizations, yet many unaffiliated with an organization were also sampled when surveying the greater population. Individuals from the greater population were sampled from the above cities in parks, shops, and other open spaces based on whether they could speak Serbo-Croatian and were willing to complete the 15-minute survey. The survey sample (N = 780; 388 former combatants) consisted of adults from Bosnia-Herzegovina (N = 252; 118 former combatants; 180 males), Croatia (N = 264; 136 former combatants; 183 males), and Serbia (N = 264; 134 former combatants; 198 males). Overall, former combatants had less secondary education (M = 4.53; SD = 2.19) than the greater population (M = 6.88; SD = 2.35), and were more oriented toward nationalism (M = 3.22; SD = .91) than otherwise (M = 2.62; SD = .96), while most participants overall affiliated with their nation’s traditional religion. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, 209 (82.9%) were Muslim, 205 (77.7%) of Croatians were Catholic, and 215 (81.5%) in Serbia were Orthodox Christian.

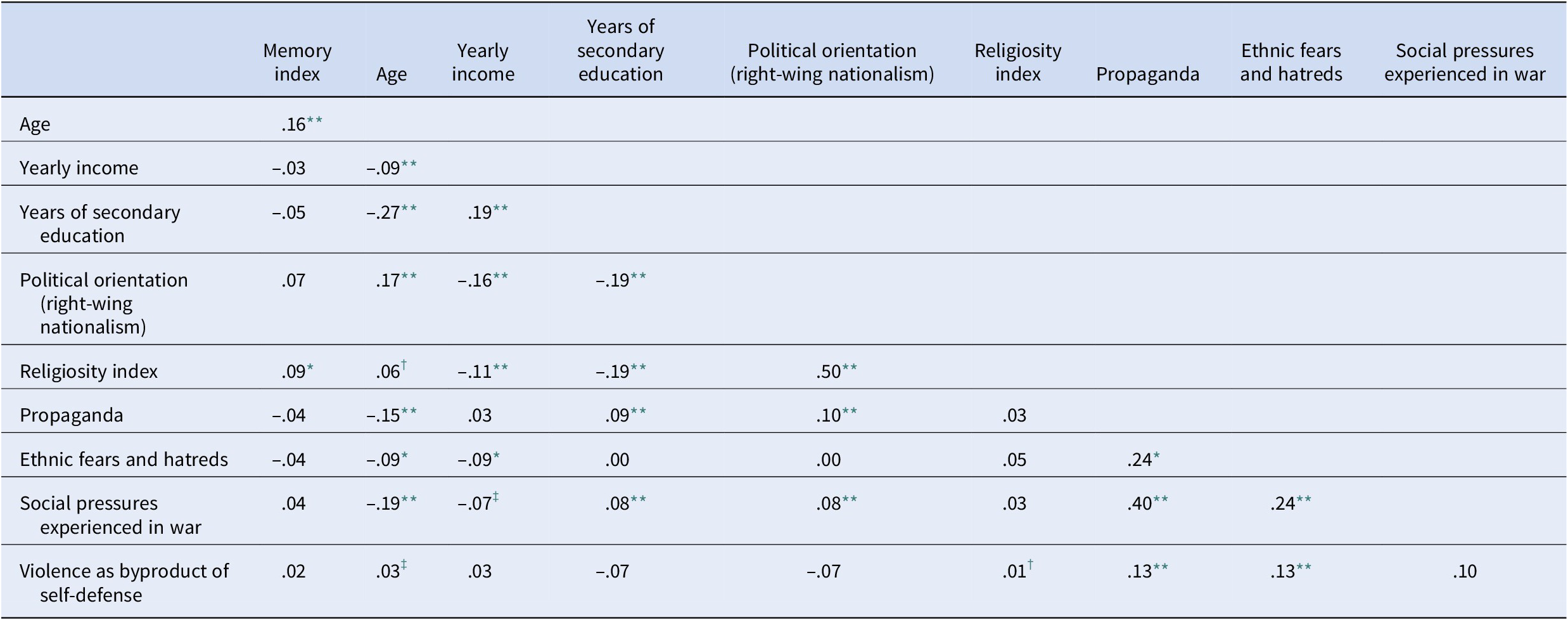

Table 1 provides a correlation matrix of the sample’s demographics and collective violence statistics. Note that propaganda and social pressures in war had a strong correlation (Pearson’s r = .40; P ≤ 0.001), as did religiosity and political orientation toward nationalism (Pearson’s r = .50; P ≤ 0.001). In the next section, I analyze these data by first considering general characteristics of the total sample, and then the causes of collective violence identified by participants in each country.

Table 1. Pearson’s correlation matrix of variables

‡ P ≤ .15.

† P ≤. 10.

* P ≤ .05.

** P ≤ .01.

To understand insider perspectives even further, I also analyzed open-structured and semi-structured interviews (N = 139) conducted from 2012 to 2016. Most interviews were done with the aid of a local assistant who helped with translations. The inclusion criteria for interviews were former combatants or survivors capable of giving informed consent. Participants were recruited using convenience and snowball sampling. At each location, persons were identified and approached in person, telephone, or by email to participate. Interested persons then selected a private location for the interview such as a veterans’ organization, café, or park. Interviews were audio-recorded only with permission and then transcribed or otherwise handwritten for analysis. Using grounded theory, I first open-coded interviews to generate concepts, and then used axial coding to produce a list of codes. Constant comparison was relied upon thereafter to review and revise codes in an iterative process, followed by selective coding in which a single framework was used for all interviews. Transcripts were then reanalyzed to ensure consistency.

Of the 139 participants, 112 were male (80.6%), while 91 were former combatants (65.5%) and had an average age of 48 (M = 48.86; SD = 8.16), ranging from 27 to 72. Twenty-seven (60%) participants in Bosnia-Herzegovina were former combatants (25 males) and 18 were survivors (8 males). In Croatia, 34 (73.8%) were former combatants (33 males) while 12 were survivors (7 males). Finally, 30 (62.5%) former combatants (30 males) and 18 survivors (11 males) were interviewed in Serbia.

Results

Accounting for Collective Violence

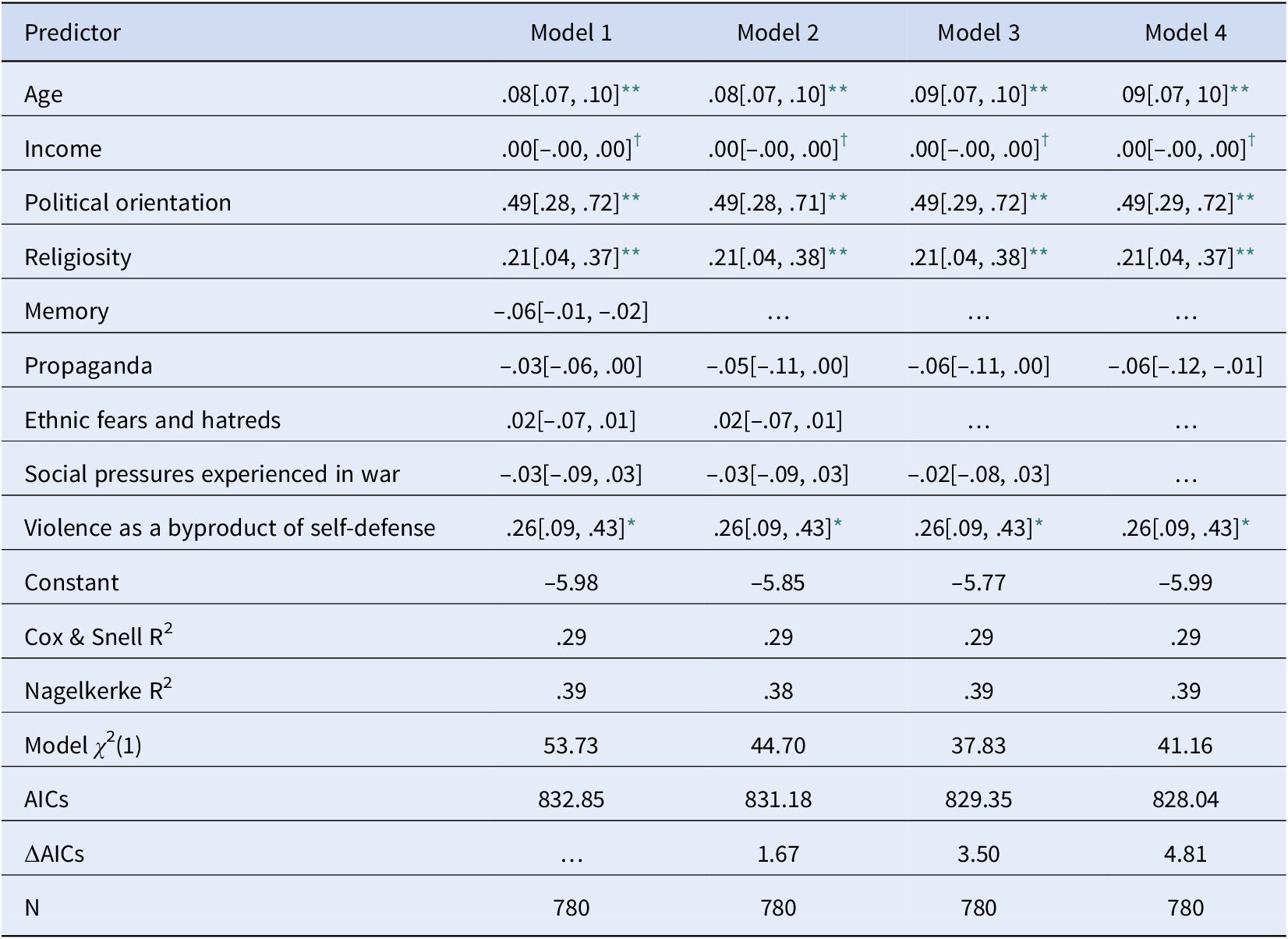

For an overall regional approximation of views, I first ran a PCA on the aggregated set of survey data from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia. Four factors were selected based on having eigenvalues greater than 1.0, and these accounted for 66% of the total regional variability in accounts of collective violence. These were propaganda, ethnic fears and hatreds, social pressures experienced in war, and violence as a byproduct of collective self-defense. To determine how these and demographics factors associated with participants, I ran binary logistic regression with participant identity (former combatant and greater population) as the dependent variable (Table 2). Multiple imputation (MICE) was used to replace missing data with mean values. Models were then backward-selected from the full model (model 1), resulting in model 4 with an evidence ratio of 11.92 and thus best accounting for participants’ views and total variance (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.39).

Table 2. Binary Logistic Regression Model Accounting for Regional Characteristics of Former Combatants

Note. All models in the form β [lower, upper]; 95% confidence intervals in brackets. All models’ mean variance inflation factors were ≤ 2.00.

‡ P ≤ .15.

† P ≤ .10.

* P ≤ .05.

** P ≤ .001.

Based on these findings, former combatants were significantly more oriented toward nationalism and religiosity than the greater populations. Overall, they also attributed collective violence to self-defense, while the greater populations attributed collective violence to propaganda. In sum, the belief that propaganda caused collective violence is predictive of non-combatants, but having engaged in combat corresponds with an increased likelihood of reporting that collective violence resulted from a perceived need for self-defense.

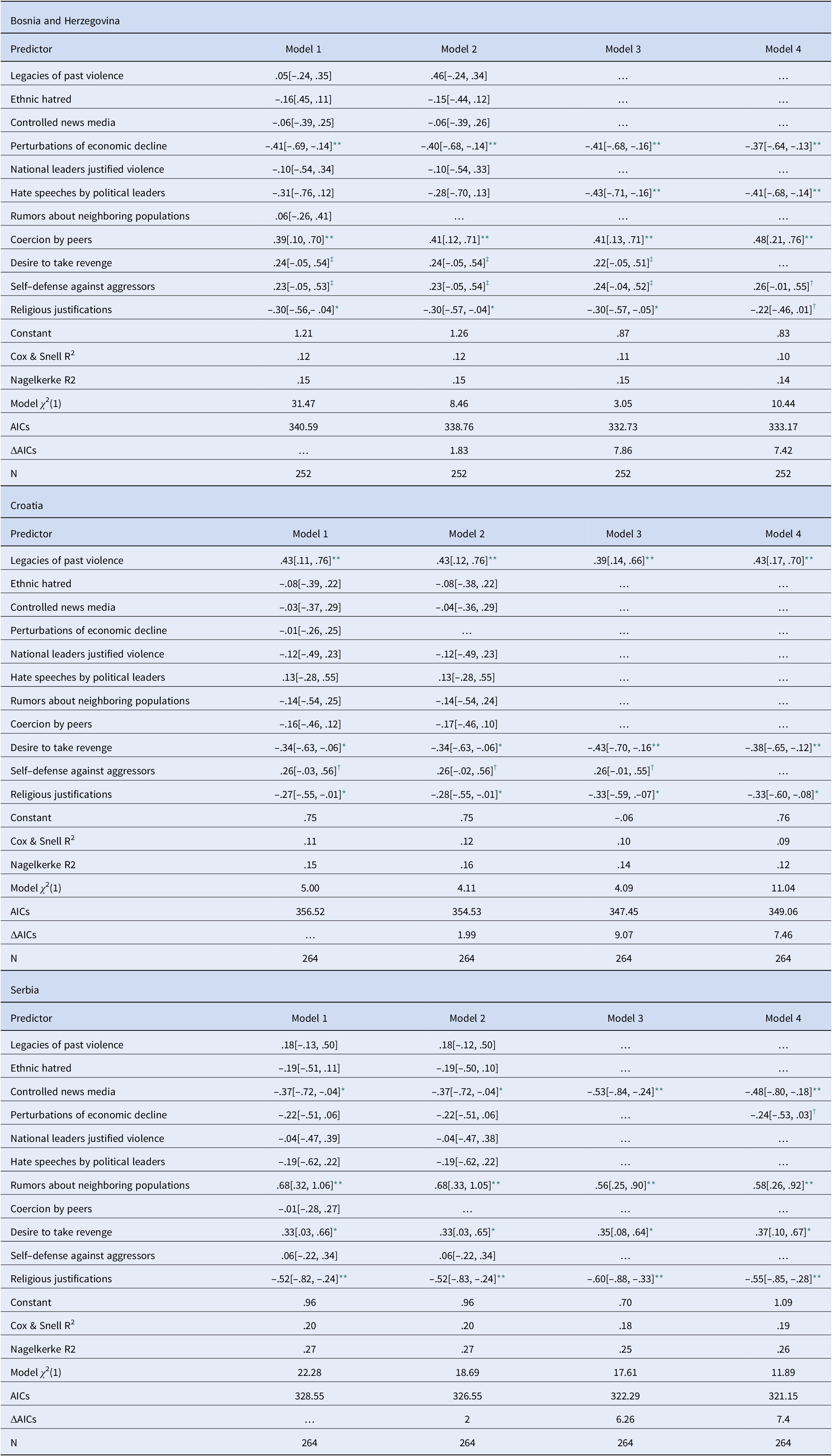

To examine the granular country-specific perspectives (Table 3), I then regressed participant identity with the focal variables comprising these principal factors. Focal variables included the legacies of past violence, ethnic hatred, Serbia’s control of Yugoslavian news media, perturbations of economic decline, national leaders who justified violence, hate speeches by political leaders, rumors about neighboring populations, coercion by peers, the desire to take revenge, self-defense against aggressors, and religious justifications of war. These focal variables were more informative at the country level than principal factors, insofar as they revealed critical differences between regional populations. As with the above analysis, country-specific models were backward-selected from the full model and used MICE for missing data. Additionally, the combination of ΔAICs, variance, and parsimony were used to identify the most predictive model for each country.

Table 3. Binary Logistic Regression Models Accounting for Former Combatants Views of Collective Violence

Note. All models in the form β [lower, upper]; 95% confidence intervals in brackets. All models’ mean variance inflation factors were ≤ 2.00.

‡ P ≤ .15.

† P ≤ .10.

* P ≤ .05.

** P ≤ .01.

For Bosnia-Herzegovina, (not including Republika Srpska), model 3 was 28.04 time stronger than model 2 and 23.84 times stronger than model 4 and thus explained the greatest amount of variance (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.15). Accordingly, the strongest predictor of collective violence for Bosniak former combatants was coercion, while the strongest predictors for the greater population were Yugoslavia’s perturbations of economic decline and hate speeches by political leaders.

Interview data provide readily interpretable sources for these findings. Several former combatants talked about communities coercing young men to join militias and forcing entire communities to participate in war efforts. One explained that “There were people who didn’t want to fight,” and that “We would arrest them and then take them to places to dig trenches” (12/7/15). Former combatants likewise had opportunities during and after the wars to speak with neighbors who fought on the Serbian or Croatian side, discovering that many were similarly forced to engage in violence. Many Bosniaks also talked about Yugoslavia’s economic crisis as a necessary condition for political conditions that contributed to collective violence. As one Bosniak explained, “If people had their jobs and solved their living problems, then they wouldn’t have thought about politics” (11/23/15). Finally, many talked about Serbian nationalistic speeches inspiring collective violence. When discussing why Serbs sieged Sarajevo, for instance, a Bosniak remarked, “Speeches made them believe that we were occupiers or terrorists in Europe, and that our lands were not our own, and that we were not even the people we really were” (12/30/15).

Turning to Croatia, models were again backward-selected with results indicating that model 3 was 51.63 times stronger than model 2 and 2.15 stronger than model 4. Thus, legacies of past violence in the region served as the strongest predictor of collective violence for Croatian former combatants, followed by violence as a byproduct of self-defense. For the greater population, collective violence was associated with the desire to take revenge for past crimes and religious justifications of war.

Interviews again shed light on these results. For most former combatants, collective violence would not have ensued if not for memories of Serb victimhood under the Ustasha during WWII. As one explained, Serb leaders would not have been able to convince Serbs to attack Croats categorically without associating present-day Croatians with the Ustasha. “By frightening them of the Ustasha,” he said, “they tried to achieve their goal of a Greater Serbia and raise up local Serbs to stand up to Croatians” (3/2/16). Serb authorities did so, many believed, by exploiting traumatic memories to convince Serbs that Croatian independence was a renewal of conflicts and Serb persecution. The result was a spiral of tit-for-tat violence which communities interpreted as necessary self-defense. After witnessing Serb sieges on Croat cities, one former combatant explained, “We started arming ourselves and preparing for aggression because we expected it” (3/7/16). The greater population of Croatia held similar views but were more likely to discuss revenge and religion on all sides of the conflicts. After explaining that Serbs and Croats were both motivated by revenge for historical crimes and religious justifications thereof, a Croat concluded that: “For there to be peace, you need to take away the history books from both sides” (2/5/16).

Finally, backward-selected models for Serb participants (Serbia and Republika Srpska) revealed that model 4 was 1.69 times stronger than model 3 and had the lowest AICc score and highest variance (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.19). Given these ratios, the strongest predictors of collective violence for former combatants were rumors about neighboring populations and the desire to take revenge. For the greater population, collective violence was attributed to Serbia’s controlled news media and Yugoslavia’s perturbations of economic decline.

Recall that hate speeches, legacies of past violence, revenge, and religion were predictive causes for Bosniaks and Croats, who perceived these as motivations for Serb forces. Here, we see some corroboration in both survey and interview data with Serb former combatants. Many talked about rumors on the warfront as motivating a desire to avenge Serb victims or to drive perceived threatening groups away from Serb communities. In an interview, a former combatant justified Serb attacks on non-Serbs by saying, “I didn’t see but I heard stories from people who got away from the kama [a knife used by Ustasha in WWII to kill Serbs]. People who were in danger were running away. Their houses burned down. What were they supposed to do?” (10/23/15). For the greater population, propaganda under the Milošević regime clearly contributed to support for collective violence. One Serb said, “Propaganda made it all happen—it was like shouting ‘fire’!” (6/4/12). The greater population also believed that perturbations of economic decline, such as Yugoslavia’s economic crisis, set in motion the emergence of nationalists who drew on legacies of past violence to instill fears about neighboring populations seeking independence. When reflecting on why Serbian leaders were able to stoke so much fear, one Serb explained, “No one could reconcile with bad economics” (10/9/15).

Emic Views of Collective Violence

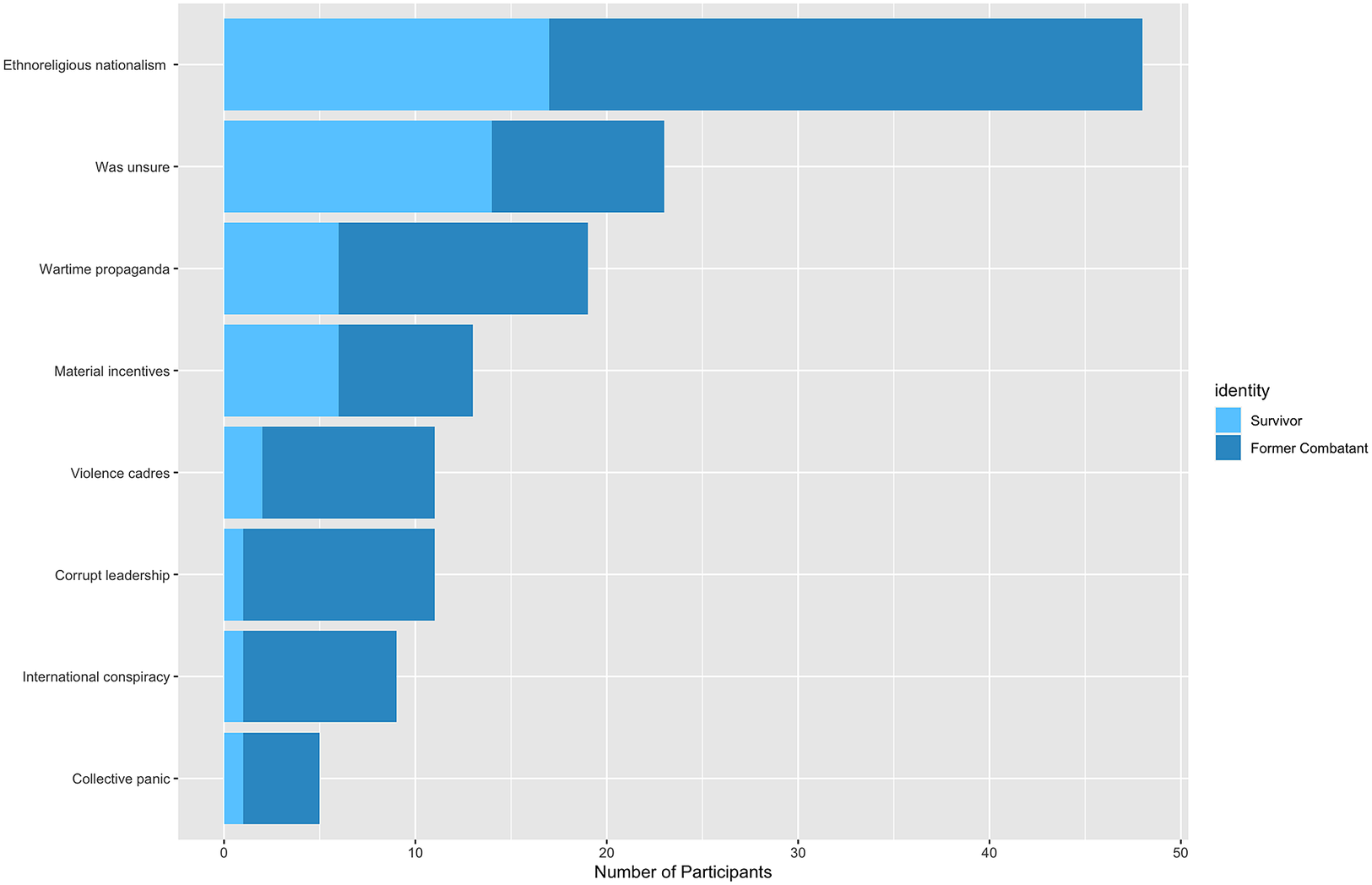

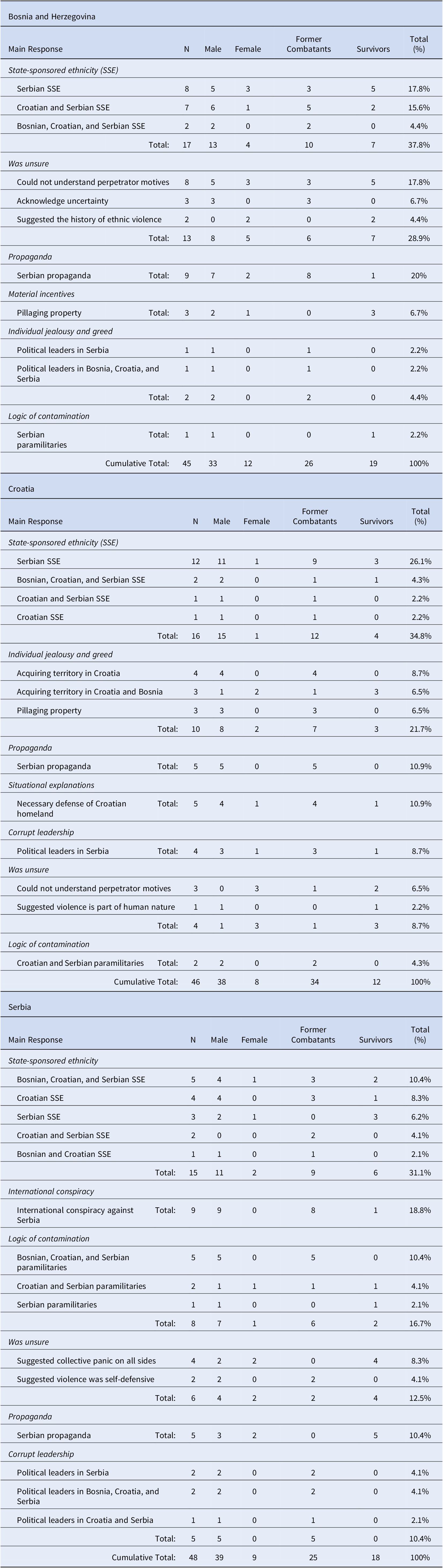

Turning now to interview results in more detail, Figure 1 depicts the eight most cited causes of collective violence, while Table 4 outlines the more granular, underlying meanings of each cause for participants. In Figure 1, the magnitude of each bar represents the numerical count of former combatants and survivors (by color) who reported the said cause. Table 4 delineates the underlying meaning of each cause according to country, participants’ identity (former combatant or survivor), and gender.

Figure 1. What caused collective violence in the Yugoslav Wars?

Table 4. What Caused Collective Violence in the Yugoslav Wars?

Taken together, the remembered causes of collective violence for former combatants and survivors were in descending order the following:

State-Sponsored Ethnicity

Thirty-one former combatants and 17 survivors reported that collective violence was set in motion and sustained in the wars by a form of populism and identity politics in which an ethnic, religious, and national identity was imposed on persons, who were then targeted for it. Participants offered a range of examples showing how the transition from a shared South Slav to a Serb, Croat, or Muslim identity was accompanied by growing interethnic and religious animosities (see also Golubović Reference Golubović2020; Mojzes Reference Mojzes2016; Povrzanović Reference Povrzanović2016). There was strong agreement that these animosities began during Yugoslavia’s economic crisis when nationalists started openly using slurs for ethnic others such as “Turks” for Muslims and “Ustaša” for Croatians. “When people began calling us Turks,” one Bosniak remembered, “It was then that I started to feel threatened” (11/17/15). Participants also felt that ethnoreligious discrimination before the wars signified a return to injustices of former regimes. Several participants added that as the dissolution of Yugoslavia became imminent, they were expected to conform to their community’s particular ethnoreligious-national commitments or face accusations of betrayal. A Croat former combatant explained, “suddenly you weren’t Croatian unless you had the right name, were Catholic, and supported the HDZ [Hrvatska Demokratska Zajednica; Croatian Democratic Union]” (1/28/16). State-sponsored ethnicity was also most cited as instilling a shared belief that one’s country—as an ethnoreligious nation—was destined to be saved if not re-forged in war. As a Serb former combatant described it, “there would be no more war in the Balkans when there were clear ethnic states” (10/9/15). This shared belief was said to have contributed to support for policies or activities that resulted in collective violence.

Critically, 23 (74.2%) of the 31 participants focused on state-sponsored ethnicity in Serbia, where an ideology developed that many believed functioned as a justification for collective violence. Specifically explained by one participant as a “Greater Serbia ideology—a country where all Serbs from the Balkans would live” (12/15/15). Participants believed that this ideology contributed to ethnic cleansing by Serb forces but also to violent ideologies in neighboring republics. Participants remembered Croatian nationalists using the threat of a Greater Serbia as a justification for “stirring [their own] nationalistic muck to agitate Croats” (2/3/16). Nationalists in Bosnia likewise used the Serb threat to bolster state-sponsored ethnicity, including a wartime narrative about “Serb aggressors,” which “created something like a feeling that, ‘We are right about them! And they are rats for what they do’” (11/18/15). Accordingly, participants remembered state-sponsored ethnicity in Serbia and reactionary movements in neighboring republics as creating an “identity trap” (Donohue Reference Donohue2012), and thus politicizing identities across regions and localities (Ashbrook Reference Ashbrook2011) and supporting other conditions for collective violence.

Was Unsure

Nine former combatants and 14 survivors reported that they were unsure what caused collective violence. Eleven participants said they could not understand the motivates of perpetrators, while 4 suggested that collective violence may have stemmed from situational factors or fears derived from the region’s legacies of past violence. Additionally, 3 participants said that they simply did not know, 2 suggested that community-wide self-defense devolved into collective violence, and 1 said that collective violence may be due to a dark side of human nature. Such uncertainty often stems from still coming to terms with the past (Obradović-Wochnik Reference Obradović-Wochnik2013).

Propaganda

Thirteen former combatants and 5 survivors reported that Milošević’s state-controlled media and speeches by Serb nationalists caused collective violence. Participants believed that false-news reports such as Bosniaks feeding Serbs to animals at the Sarajevan zoo or Croats killing Serbs to harvest their organs incited Serb combatants. As one Serb former combatant explained, such reports “made people believe that war was inevitable, and that Serbs had to be saved” (10/19/15). Remarkably, the same media convinced Bosniak and Croat former combatants to support their own wartime efforts. “When I heard what [Serb nationalists] were saying,” a Croat former combatant said, “I thought, ‘There is no way of avoiding this, we will have to fight’” (3/2/16). Equally as remarkable, 5 Serb former combatants did not identify news or speech as influential but admitted to once believing that Serb forces had to intervene in Croatia and Bosnia “to protect Serbs from being wiped out” (7/6/12). Survivors also recalled that combatants on their way to war seemed to have “felt like the Serbian heroes of old, like on the Field of Kosovo” (4/12/16). Thus, Serb propaganda likely increased support for wartime efforts, and may have combined with state-sponsored ethnicity to instill a warrior’s imaginary or vision for avenging historical injustices. An imaginary in anthropology is a cultural model built from values and symbols through which members of a social group or subculture envision their social whole.

Individual Jealousy and Greed

Seven former combatants and 6 survivors mentioned that collective violence was motivated by the material incentives of war, including pillaging and acquiring neighbors’ property. Three Bosniaks and 3 Croats said that perpetrators “went to war to loot” (3/7/16). Moreover, 7 participants in Croatia reported that Serb forces “wanted to dismember Croatia [and Bosnia] and realize the idea of a Greater Serbia” (2/25/16). Hence, over half of those who reported individual jealousy and greed linked their explanation to Serb state-sponsored ethnicity.

Logic of Contamination

Eight former combatants and three survivors emphasized that people were influenced by violence cadres such as paramilitaries or “weekend warriors.” Five said that collective violence was caused by paramilitaries on all sides, four focused on those of Croatia and Serbia, and two on Serbian. Yet nearly all participants who were interviewed expressed contempt for paramilitaries. “I hate the criminal war profiteers for what they did,” said a Serb former combatant, “They are the enemy of the people” (9/22/15).

Corrupt Leadership

Ten former combatants and 1 survivor claimed that corrupt leaders during Yugoslavian succession caused collective violence by making “false accusations and a politics of division [that] led to intolerance” (3/3/16) and turning war into “big business” (9/23/15). In short, leaders imposed a state-sponsored ethnicity and manipulated national causes, making violent succession inevitable. Yet, in the end, as participants explained, only elites and politicians profited. A Croat former combatant expressed a common sentiment when he said, “There is no one else to blame but our politicians and ourselves for allowing them to create that chasm of differences among us” (2/11/16)

International Conspiracy

Eight former combatants and one survivor in Serbia said that an international conspiracy that included NATO brought about succession and collective violence. These participants also believed that the international community conspired with Serbia’s neighboring republics to exaggerate or stage collective violence to portray Serbs as aggressors. “They [international community] wanted to crush us,” a Serb former combatant explained, “and to take Kosovo away from us” (7/4/12). Insofar as these views cohere with propaganda and a nationalist postwar narrative in Serbia (Di Lellio Reference Di Lellio2009), it is difficult to say when former combatants and survivors adopted them (e.g., Baele Reference Baele2019).

Situational Explanations

Four former combatants and one survivor in Croatia believed that ethnic cleansing resulted from situational factors such as collective panic among borderland populations. Specifically, violent border skirmishes between ethnic factions alongside the breakdown of Yugoslavia brought about paranoia that eventually spread through Croatia and Serbia, leading to collective violence. For instance, a Croat survivor explained, “people started seeing things, you know, like a reflection from the hills or from a rooftop, and they reported a sniper, and people fell into collective panic” (1/19/16). As a result, people became more open to wartime narratives about the necessity of fighting for their homeland such as removing neighboring ethnoreligious threats.

Discussion

According to these data, the primary cause of collective violence, as recalled by most participants across the former Yugoslavia, was a turn toward state-sponsored ethnicity: an ideological frame that nationalist leaders used during the Yugoslav crisis as a reference point for shaping how they, as political elites, could win support and define their political strategies (Fujii Reference Fujii2009, 187; Straus Reference Straus2015, 57). It drew on pre-crisis narratives about historical legacies of violence, myths of ethnic-national identity, and innovations on religious culture (see also Bringa Reference Bringa1995). As Sell (Reference Sell2003, 309-310) observed, most people did not choose this state-sponsored ethnic identity but discovered that it was imposed on them as succession ensued (see also Gagnon Reference Gagnon2004; Lučić Reference Lučić2015). As a political movement, state-sponsored ethnicity—centering on an imagined history but also traumatic collective-memories of WWII (Dragojević Reference Dragojević2013; Đurašković Reference Đurašković2016), innocence (Živković Reference Živković2011), and destiny for the people or nation as a unique ethnic, religious, and national community—emerged most memorably in Serbia during the final years of Yugoslavia. Serb nationalists are remembered as exploiting popular crisis-sentiments, ending the civil rhetoric of the Yugoslav era by openly insulting ethnoreligious outgroups, portraying Croatian and Bosnia independence as renewed persecutions of Serbs, and advocating for a land where Serbs could live free from persecution (Oberschall Reference Oberschall and Dojčinović2012). Serbia under Milošević, in turn, compelled nationalists in neighboring republics to engage in similar demagoguery and use the threat of Serb aggression to promote aggressive political agendas, thus escalating intergroup tensions. Most participants, therefore, remembered state-sponsored ethnicity, first in Serbia but then in Croatia and Bosnia, as engendering a dangerous identity-centered politics that provided the ideology for propaganda and collective violence.

Study results also offer support for propaganda’s secondary influence. Yet, the recalled effects on populations differed in ways overlooked by prior studies. Remarkably, Serb propaganda contributed to outgroup cohesion among many Bosniaks and Croats, convincing former combatants that they had to volunteer for war and that violence against perceived Serb threats was justified. Moreover, Serb participants indicated that the controlled news media under Milošević convinced many that Serbia’s neighboring republics were committing atrocities that Serbs had to prevent if not avenge. Misinformation in Serbia during or after the wars also contributed to present-day denialism about the extent of collective violence among some Serb former combatants. Propaganda also had an indirect influence during the wars by coordinating combatants. The association between propaganda and social pressures to volunteer for combat offer a partial explanation of this effect. While Bosniaks and Croats often experienced social pressures to volunteer for war after their community was exposed to Serb propaganda, many Serb former combatants reported feeling compelled to go to war because of misinformation on Serb-controlled media (Boljević et al. Reference Boljević, Odavić, Patrović, Rabrenović, Stanković, Janković, Vučo and Vukotić2011). Alongside state-sponsored ethnicity as a cultural frame, propaganda may have functioned less to instill both hatreds and fears but to coordinate coalitions of would-be fighters (Moncrieff and Lienard Reference Moncrieff and Lienard2019). Thus, state-sponsored ethnicity may have provided the necessary cultural ideology and justifications that rendered propaganda as a meaningful signal, around which audiences collected and conveyed their acceptance of violence as a perceived necessity during Yugoslav succession.

Accordingly, these results corroborate several findings from other post-conflict ethnographies. First, granular data challenge the ethnic hatreds and ethnic fears theses and instead support the social interaction thesis: that communities do not support or engage in collective violence because they hated or feared the targeted outgroup but rather because of more immediate, less abstract reasons (Fujii Reference Fujii2009, 185). Here, the most critical factors were similar to other post-conflict ethnographies and included perturbations to economic decline, coercion by peers, legacies of past violence, rumors about neighboring populations, and propaganda. These likely overlapped with other social factors explored by ethnographers in post-conflict Balkan regions such as traditional norms of patriarchy and masculinity (Dumančić and Krolo Reference Dumančić and Krolo2017; Milićević Reference Milićević2006). Second, this study offers evidence that propaganda, as a contributing factor to collective violence, may have both directional and motivational influence that theorists following speech crime trials overlook—for example, Serb former combatants reported feeling compelled to volunteer for war due to propaganda but remember fears and hatreds stemming less from wartime media and more from rumors on the frontline. Third, the triangulation of various data suggest that data reported here are trustworthy. For instance, interview participants did not always adhere to prescribed narratives, give self-serving or self-aggrandizing statements, or take the opportunity to point the finger. Following other post-conflict ethnographers (Fujii Reference Fujii2009; Hinton Reference Hinton2004; Mironko Reference Mironko and Thompson2007), I take these as reasons for trusting the data despite the constraints of collective and individual memories. Fourth, the research presented in this article points to propaganda as a secondary influence on collective violence; thus, it remains difficult to definitively speak to any degree of causation. If propaganda is entangled in the historical imaginary, cultural knowledge, and emotionally resonant symbols of a community, as this and other post-conflicts studies indicate, then measuring the perlocutionary effect of any propagandist may remain opaque.

Nevertheless, my interviews with former combatants and survivors revealed consistent conditions that insiders identified as significant for propaganda, which cohere with factors identified by recent theorists (e.g., Leader Maynard and Benesch, Reference Leader Maynard and Benesch2016). These included the widely remembered political-shift that came with state-sponsored ethnicity or political movements associated with ethnoreligious nationalism. Such an identity-imposed politics was remembered as setting the stage for later discursive injustices and criminal speech, which did not instill hatreds or fears but convinced many that conflict and perceived self-defense for themselves, as a targeted categorical group, was unavoidable. As I report elsewhere (Kiper Reference Kiper2018), propaganda in the case of the Yugoslav Wars often prompted would-be fighters to the frontlines, but it was the conditions on the warfront itself and among distinct violence cadres, such as paramilitaries or weekend warriors, that contributed most strongly to atrocities.

These case studies, comparatively speaking, help us understand the divergent and overlapping cultural logics of collective violence in the Yugoslav Wars. As with post-conflict ethnographies in Cambodia and Rwanda, former combatants and survivors remembered causes that differed from legal narratives. A key takeaway from this study is that results neither supported the hypodermic-needle thesis nor the claim that propaganda directly caused combatants to engage in collective violence. Instead, propaganda played a significant role in getting combatants to the frontline and convincing people on the homefront that violence was necessary. Yet, it was an array of sociopolitical conditions brought about by ethnoreligious nationalism and state-sponsored ethnicity – which varied across republics and regions – that most participants remembered as bringing about collective violence.

These findings suggest that, while courts and legal scholars push to identify a causal-link, a helpful approach for social scientists may be to focus on the felicity conditions such as sociopolitical crises and emergence of state-sponsored ethnicity during paroxysms of ethnic and religious nationalism. These social conditions allow propaganda to coordinate people who, unlike years before, now see themselves and others, or are treated as if they were, belonging to categorical groups. If post-conflict ethnographies and other case studies continue to reveal a similar set of social conditions, tracking these may predict when any speech act is likely to correlate with collective violence, and thus such knowledge would, as many post-conflict ethnographers hope, contribute to atrocity prevention.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2022.53.

Financial Support

University of Connecticut Department of Anthropology Summer Fellowship, Human Rights Fellowship Research Excellence in Law

Disclosure

I have no known conflict of interest to disclose.