Highlights

-

• One in four older adults in Bengbu, China, has possible sarcopenia.

-

• High nutrition literacy (NL) levels are associated with a low incidence of possible sarcopenia.

-

• Socio-economic status and disease influence NL and possible sarcopenia rates.

Ageing is a critical public health challenge in China, where more than sarcopenia 290 million Chinese people (21·1 % of the overall Chinese population) were older than 60 years in 2023. This proportion is predicted to reach 38·8 % by 2050(1,2) As they age, older individuals face a variety of health challenges, including an increased incidence of sarcopenia. One meta-analysis of thirty-five studies from several countries reported that the estimated overall prevalence of sarcopenia in adults over the age of 60 was 10 %(Reference Shafiee, Keshtkar and Soltani3). By contrast, in older Chinese older individuals, this prevalence is 18 % for men and 16·4 % for women(Reference Chen, Li and Ho4). Sarcopenia is a progressive, systemic decrease of the muscle mass and strength of skeletal muscles that is associated with a wide range of consequences, such as functional decline, falls, broken bones, physical disability, poor oncological prognosis, metabolic disorders, depression, poor quality of life and death, substantially increasing the risk of hospitalisation(Reference Xia, Zhao and Wan5–Reference Yang, Liu and Zuo7). These physical burdens are also associated with substantial medical and economic burdens(Reference Beaudart, Zaaria and Pasleau8), rendering sarcopenia an urgent health challenge for older adults(Reference Cruz-Jentoft and Sayer9,Reference Dhillon and Hasni10) .

Although the occurrence and progression of sarcopenia depend on several factors, diet is highly crucial(Reference Anton, Hida and Mankowski11). The maintenance of skeletal muscular mass depends on the balance of protein synthesis and decomposition in the body. As the body’s metabolism declines with age and the body’s musculoskeletal systems become less efficient, older adults are prone to malnutrition or overnutrition, which may result in deficiencies of vitamins and micronutrients and cause a decline in skeletal musculature mass and power(Reference Papadopoulou12). Consuming milk, dairy products and protein supplements can increase bone mineral density and muscle strength, preventing or delaying sarcopenia(Reference Papadopoulou, Papadimitriou and Voulgaridou13). Despite the proven benefits of balanced diets, many studies have focused exclusively on single foods or nutrients.

Nutrition literacy (NL) refers to the ability to access, analyse and utilise basic nutritional messages or services and make informed nutritional decisions as a result(Reference Thornton, Jeffery and Crawford14). NL is a crucial health skill for older adults. Specifically, NL encourages individuals to select healthy foods, and a lack of NL contributes to the consumption of diets of low quality(Reference Taylor, Sullivan and Ellerbeck15,Reference Spronk, Kullen and Burdon16) . NL thus improves nutrition and health. However, to date, no study has reported the associations between NL and the incidence of sarcopenia. Therefore, this study examined the associations between NL and possible sarcopenia in people from China.

Methods

Participants and procedure

This cross-sectional study was conducted in May 2023 in Bengbu City, Anhui Province, China. The study participants were invited to participate through urban–rural stratified multistage random sampling. In the first stage, two urban areas and two rural counties and townships were selected as urban and rural sampling points using random sampling. In the second stage, two streets and two towns/villages were selected at random from each of the urban areas, counties or townships identified in stage 1. In the third stage, 110 households were selected at random from the streets or towns/villages identified in stage 2, and all members of the households who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate as the target population. The inclusion criteria were being ≥ 18 years old, being conscious, being able to communicate verbally without impediment and being able to complete the questionnaires either independently or under the guidance of the researchers. All participants participated voluntarily and signed an informed consent form. The authors designed and administered a structured questionnaire to obtain demographic information, lifestyle behaviours, NL and sarcopenia-related data in a face-to-face interview. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethics Committee of Bengbu Medical College (2021-099).

A total of 2400 individuals were invited to participate in the survey by community workers. Of these, 2287 engaged in the interview process, with 2279 ultimately completing the questionnaire, yielding a completion rate of 95·0 %. Given that sarcopenia is prevalent mainly in older adults, this study selected those aged 60 years and above as study population. Among 1355 older adults who are aged 60 years and above in the survey, 17 (1·3 %) were excluded due to incomplete data on NL and sarcopenia, and finally, the remaining 1338 were included in this study. There was no difference in characteristics between lost sample and final sample.

2·2 NL assessment

The twelve-item short-form NL scale(Reference Mo, Han and Gao17) was used to assess the NL of the participants along two domains (nutrition cognition and nutrition skills) and six dimensions (knowledge, understanding, obtaining skills, applying skills, interactive skills and critical skills). Each item on the twelve-item short-form NL scale is rated on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher NL. In this study, NL was divided into four quartiles. The instrument had acceptable reliability for Chinese adults(Reference Mo, Han and Gao17,Reference Zhang, Sun and Zhang18) . The twelve-item short-form NL scale generally showed good model-data fit (online Supplementary Table S1) and convergent validity (online Supplementary Table S2) and had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0·870 in this study.

2·3 Identification of possible sarcopenia

Possible sarcopenia was identified using the strength, assistance, rising, climbing and falling (SARC-F) instrument in conjunction with measurements of calf circumference (SARC-CALF). The SARC-CALF is recommended as a screening tool for sarcopenia by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia(Reference Chen, Woo and Assantachai19), with adequate sensitivity and specificity(Reference Chen, Tseng and Yang20). The SARC-CALF instrument enhances the sensitivity of the identification of sarcopenia, which is low when the SARC-F is used alone. The questionnaire portion comprise questions in five categories: strength (S), assistance with walking (A), rising from a chair ©, climbing stairs (C) and falls (F), with endpoints ranging from 0 ‘not at all’ to 2 ‘very much,’ with a total possible score of 10(Reference Malmstrom and Morley21). If the circumference of the calf was less than 34 cm for men or 33 cm for women(Reference Chen, Woo and Assantachai19), ten points were added to the SARC-F assessment; in all other cases, no additional points were added. The SARC-CALF is scored by summing the SARC-F points and the calf circumference points. A score of ≥ 11 on the SARC-CALF indicates possible sarcopenia(Reference Chen, Woo and Assantachai19).

2·4 Other variables

A range of potential confounders were controlled for, comprising socio-demographic factors, lifestyle factors and chronic disease status, to ensure the results were reliable. Data were collected on age, sex, area of residence (urban, rural), smoking status (never smoked, used to smoke and currently smoking), drinking status (never drank, used to drink and currently drinking), exercise (never exercised, used to exercise and regularly exercising), education (primary school and below, junior high school and senior high school and above), occupation (farmer, separated/retired staff and others), marital status (married and others (unmarried, divorced or widowed)), monthly income (< 3000 RMB and ≥ 3000 RMB), chronic disease status (yes (Suffering from any one or more of high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, stroke and cerebrovascular disease, bronchitis, digestive disease, osteoporosis, dyslipidaemia, arthritis, rheumatism, low back disease, cancer and so on.) or no), BMI (underweight (< 18·5 kg/m2), normal (18·5–23·9 kg/m2), overweight (24–27·9 kg/m2) or obese (≥ 28 kg/m2)) and average daily protein intake, which is based on FFQ.

2·5 Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means (sd) standard deviations (SD), and categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. An analysis of variance was performed to explore the association of age (continuous variable) with NL and sarcopenia, and a χ 2 test was employed to determine the associations between categorical variables. Binary logistic regression was used to calculate OR and 95 % CI for the associations between NL and possible sarcopenia. We also conducted subgroup analyses to assess whether variations in the associations of NL with possible sarcopenia were associated with different residence types, education levels, monthly incomes or having chronic diseases. Finally, interaction analyses were conducted to determine the associations between different residence types, education levels, monthly incomes or having chronic diseases and NL. Data were analysed using SPSS 25·0, with a P value < 0·05 considered statistically significant.

Results

3·1 Participant characteristics

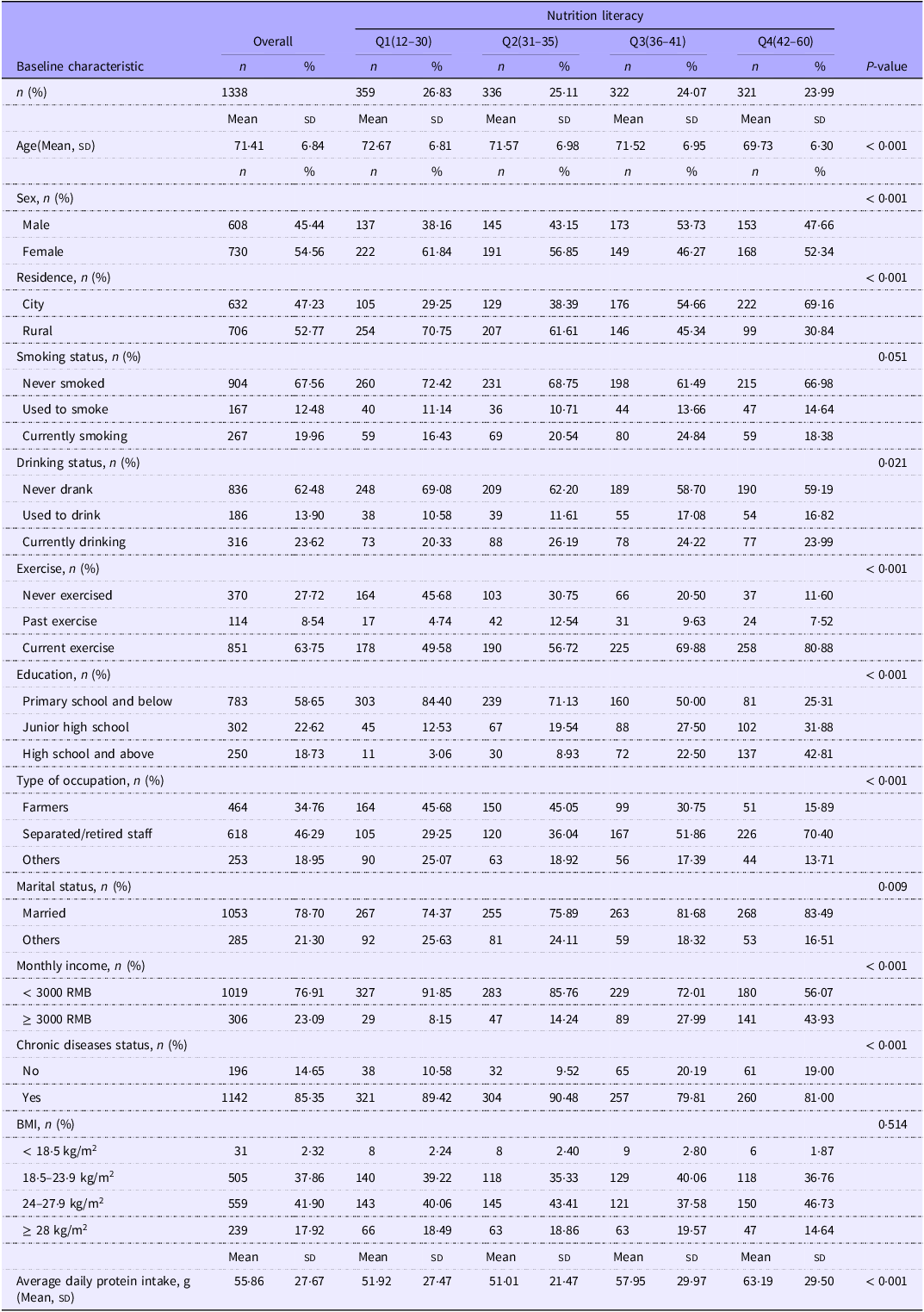

Of the 1338 participants in this study, the mean age of the participants (sd) was 71·41 (6·84) years; over half (54·56 %) were women, 47·23 % resided in urban areas, 78·70 % were married, over half (58·65 %) had a primary school education or less and most had monthly incomes < 3000 RMB (76·91 %), at least one chronic disease (85·35 %), and the average daily protein intake (sd) was 55·86 (27·67) g (Table 1).

Participants were likely to be in the upper quartile of NL if they were younger, women, lived in an urban area, had a history of drinking, regularly exercised, were educated to the senior high school level or above, were unemployed, were married, had high monthly incomes, did not have chronic diseases and have a higher average daily protein intake (Table 1).

3·2 Associations between NL levels and sarcopenia

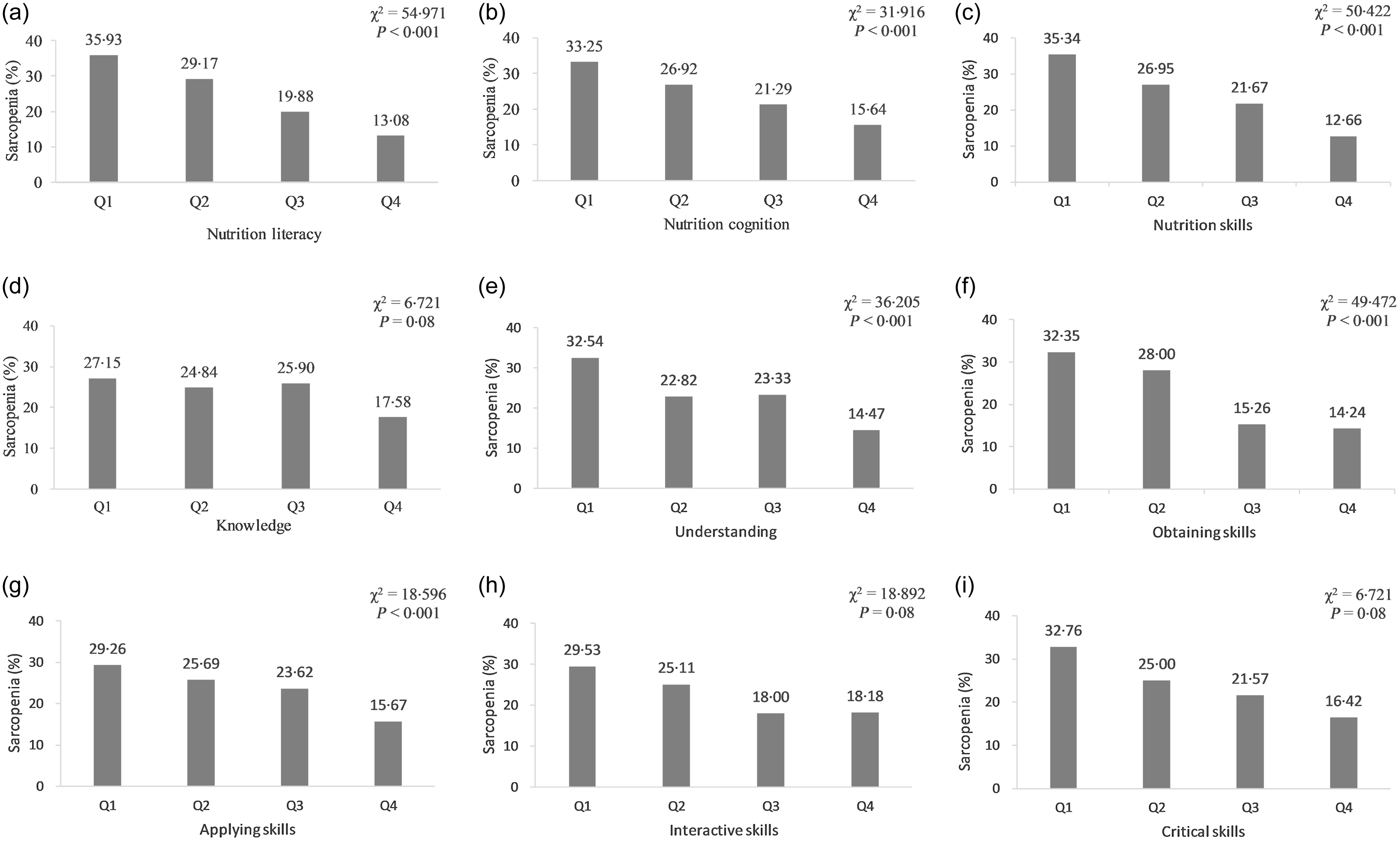

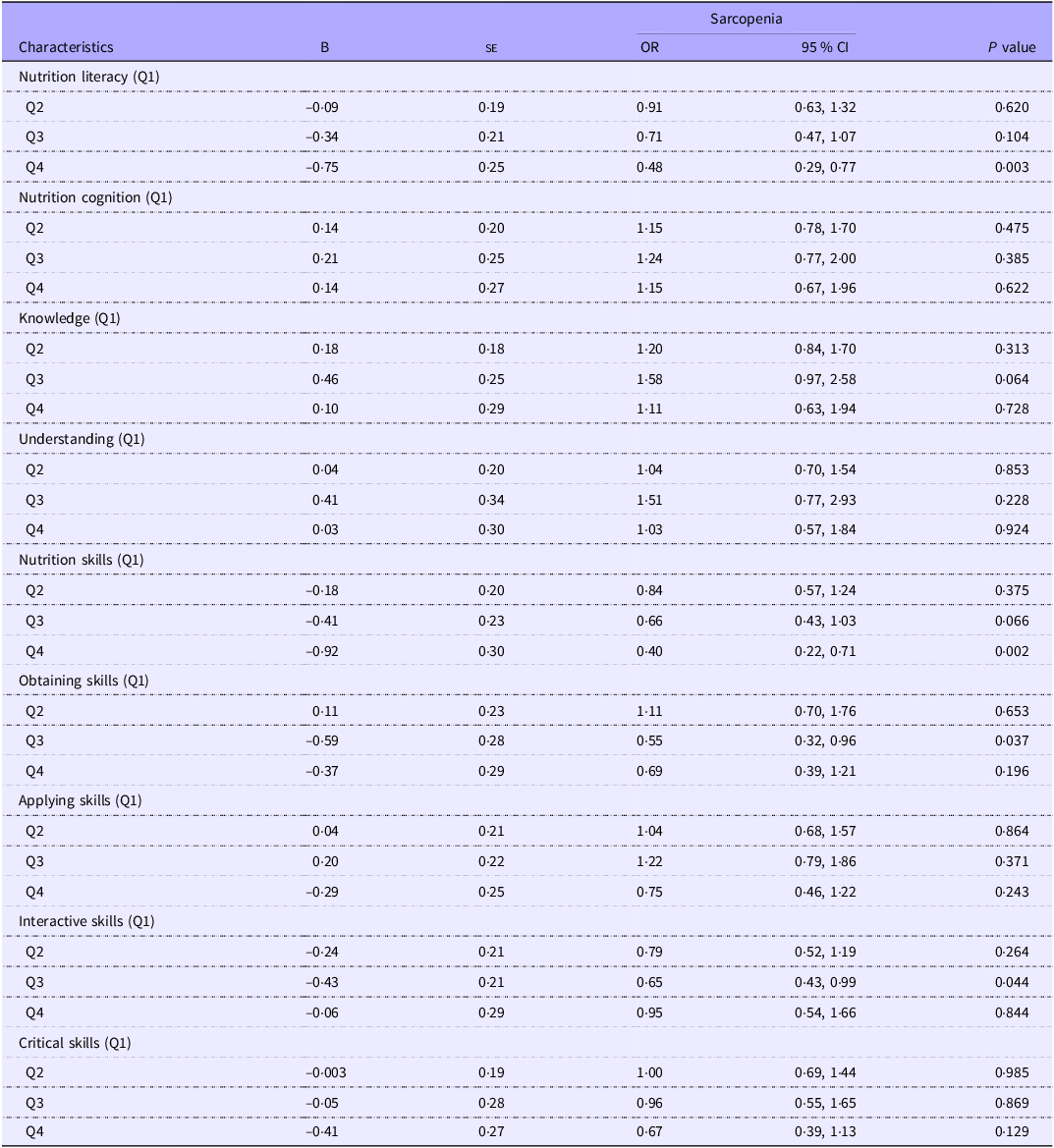

Figure 1 illustrates the incidence of possible sarcopenia by NL quartile. The higher the NL quartile, the lower the incidence of possible sarcopenia. This association was observed across two NL domains and six NL dimensions. Table 2 presents the OR for having possible sarcopenia for the NL quartiles. After adjusting for potential confounders, individuals in the upper quartile of NL were 52 % less likely to have possible sarcopenia than those in the lowest quartile of NL (OR: 0·48, 95 % CI: 0·29, 0·77). Individuals in the upper quartile of nutrition skills were 61 % less likely to have possible sarcopenia than those in the lower quartile of nutrition skills (OR: 0·40, 95 % CI: 0·22, 0·71); however, no differences were found for nutrition cognition. Across the six dimensions, older adults in the third quartile of obtaining skills were 44 % less likely to have possible sarcopenia (OR: 0·55, 95 % CI: 0·32, 0·96), and those in the third quartile of interactive skills were 34 % less likely to have possible sarcopenia (OR: 0·65, 95 % CI: 0·43, 0·99) than participants in the lowest quartile of the corresponding dimensions; however, no difference was found for the other four dimensions.

Figure 1. Prevalence of sarcopenia according to quartiles of nutrition literacy.

Table 1. Nutrition literacy in participants (Numbers and percentages; mean values and standard deviations)

Data are presented as mean (sd) or n (%).

Table 2. Logistic regression modelling for nutrition literacy and sarcopenia (Regression coefficient with their standard errors; odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

B: regression coefficient. The results are adjusted for age, sex, residential location type, smoking status, drinking status, exercise habits, education level, occupation, marital status, monthly income, chronic diseases, BMI and average daily protein intake.

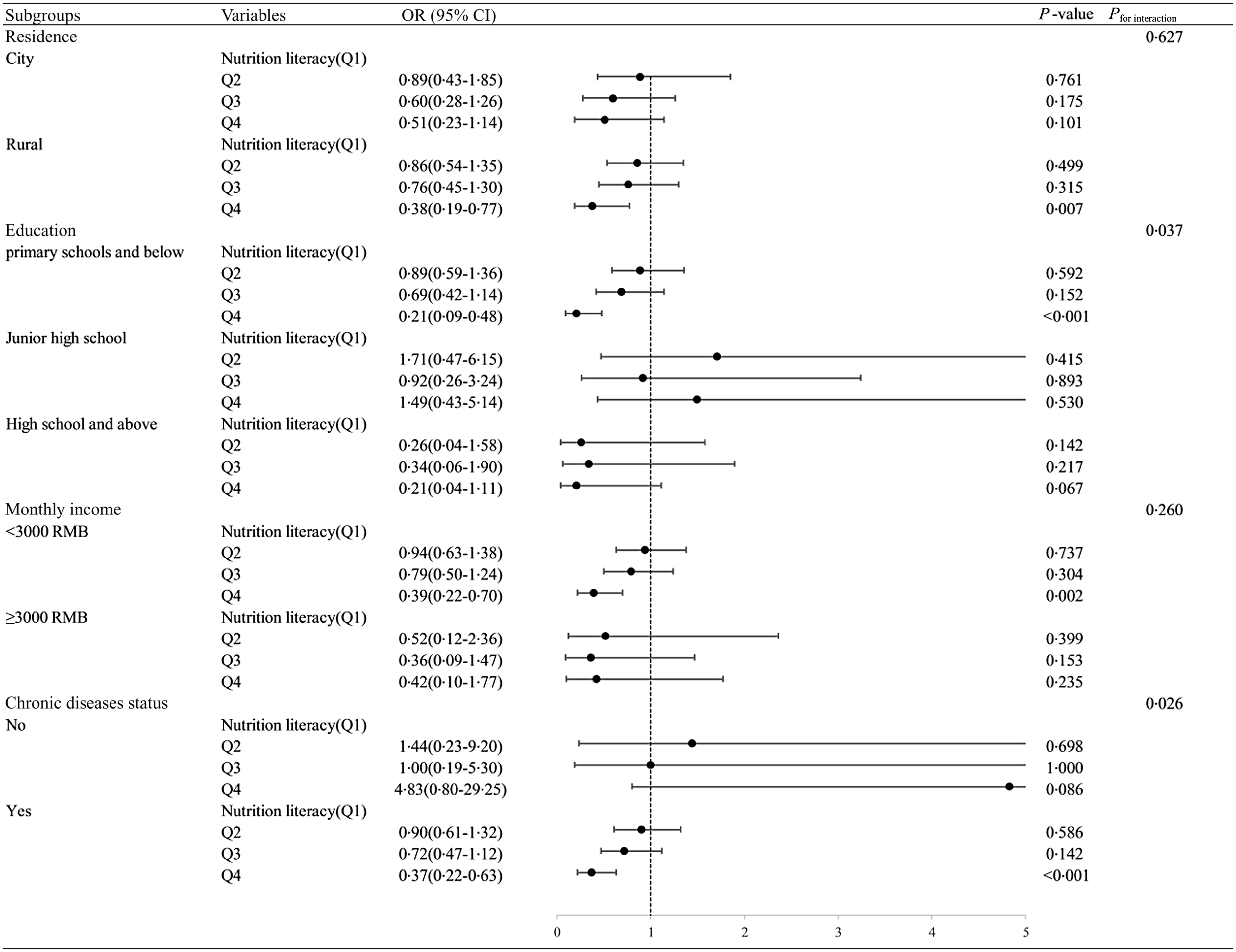

3·3 Subgroup analysis

Figure 2 illustrates the low rates of possible sarcopenia of the older adults in the upper quartile of NL following subgroup analyses. This association between high NL and low rates of possible sarcopenia was observed for older adults in rural areas (OR: 0·38, 95 % CI: 0·19, 0·77) with primary school education or less (OR: 0·21, 95 % CI: 0·09, 0·48) with a monthly income < 3000 RMB (OR: 0·39, 95 % CI: 0·22, 0·70) who had chronic diseases (OR: 0·37, 95 % CI: 0·22, 0·63), but not for older adults in urban areas with a senior high school education or higher with monthly incomes ≥ 3000 RMB who did not have chronic diseases.

Figure 2. Associations of nutrition literacy with sarcopenia stratified by residential area type, education level, monthly income and chronic diseases and their interaction with nutrition literacy for sarcopenia. The results are adjusted for age, sex, residence, smoking status, drinking status, exercise habits, education levels, occupation, marital status, monthly income, chronic diseases, BMI and average daily protein intake.

3·4 Interaction between NL and chronic diseases on sarcopenia

To investigate variations in the association between NL and possible sarcopenia depending on different residence types, education levels, monthly incomes or having chronic diseases, we derived the P for interaction for the interaction between NL and residence types, education levels, monthly incomes or having chronic diseases. Compared with older adults with less than primary education and scored in the lowest quartile of NL, those with junior high school education in the upper quartile of NL had a lower prevalence of possible sarcopenia; compared with older individuals who had no chronic diseases and scored in the lowest quartile of NL, those with chronic diseases in the upper quartile of NL had a lower prevalence of possible sarcopenia; no significant interaction was found between the other variables (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The present study is the first to investigate the associations between NL and possible sarcopenia in older adults in Bengbu, China. The results revealed a negative correlation between NL and possible sarcopenia, indicating that improving NL may be an effective method to reduce the incidence of possible sarcopenia. Because one in four older Chinese in Bengbu has possible sarcopenia, the condition is an urgent public health challenge.

This study revealed that higher levels of NL are associated with a lower likelihood of having possible sarcopenia. NL is a critical factor in shaping healthy eating behaviours(Reference Taylor, Sullivan and Ellerbeck15). Our study shows that older people with higher NL are more likely to consume more protein and that insufficient protein intake is likely to lead to sarcopenia(Reference Coelho-Junior, Calvani and Azzolino22). At least one study has demonstrated a positive correlation between higher levels of NL and healthier eating behaviours(Reference Liao, Lai and Chang23). Diet quality directly affects muscle mass and strength, and those with healthier diets experience a lower incidence of sarcopenia(Reference Bloom, Shand and Cooper24). Hence, improving NL may reduce the risk of sarcopenia by improving healthy eating behaviour. This study also observed that high levels of nutrition cognition were not associated with possible sarcopenia. However, the contribution of nutritional knowledge to diet quality depended on the interactions of several factors(Reference Wardle, Parmenter and Waller25). Moreover, increased nutrition knowledge does not necessarily lead to favourable attitudes towards goods containing information about health(Reference Wills, Storcksdieck genannt Bonsmann and Kolka26); understanding of health messages is typically based on subjective ideas that are prone to misinterpretation(Reference Dickson-Spillmann and Siegrist27) or on misinformation that leads individuals to feel confused, anxious or incapable of making wise decisions about the foods they consume. In this study, obtaining skills and interactive skills were negatively associated with possible sarcopenia. This may be because participation in food preparation(Reference Laska, Larson and Neumark-Sztainer28) or cooking meals directly(Reference Da Rocha Leal, De Oliveira and Pereira29) positively influences food choices, a process requiring nutritional obtaining and interactive skills. Additionally, reviewing information on nutrition labels has been demonstrated to be associated with making healthier food purchasing decisions(Reference Ni Mhurchu, Eyles and Jiang30). Furthermore, at least one study reported the benefits of applying skills and critical skills in improving eating behaviours(Reference Qi, Sun and Yang31), although the authors of that study did not examine the associations of these skills with sarcopenia. Nevertheless, the results of these studies suggest that improving NL is an effective method of controlling the incidence of sarcopenia.

In the present study, a notable discrepancy in the prevalence of possible sarcopenia was observed between older adults residing in rural (33·43 %) and urban (15·35 %) areas. These findings are consistent with those of earlier studies(Reference Gao, Jiang and Yang32). One explanation for these findings may be the higher rates of self-care and physical activity in older adults in urban areas than older adults in rural areas(Reference Paek and Kim33) because self-care and physical activity reduce the incidence of sarcopenia(Reference Iolascon, Di Pietro and Gimigliano34). Moreover, living conditions in rural areas are poor, and many older individuals are malnourished(Reference Zhang, Kang and Jing35) and face obstacles to engaging in physical activity, such as insufficient facilities and long travel distances(Reference Zheng and An36). Additionally, access to healthcare in the Chinese countryside is poor, exacerbating the difficulties of older individuals experiencing sarcopenia(Reference Li, Kou and Yu37). NL levels also vary widely between rural and urban areas. Older adults in urban areas generally have more resources, education and access to health care and health insurance than those in rural areas(Reference Su, Shen and Wei38). Furthermore, malnutrition rates in rural areas are nearly double those in urban areas(Reference Crichton, Craven and Mackay39). Rural older adults are not only at high risk for sarcopenia but also have relatively low levels of nutrition, so improving NL is likely to be effective in decreasing the prevalence of sarcopenia among rural older adults by improving nutritional status; however, the negative association between NL and possible sarcopenia is difficult to establish when it comes to older adults persons in urban regions with better overall health and socio-economic status. This shows that the prevalence of possible sarcopenia is more severe in rural regions, hat attention should be paid to improving the situation of sarcopenia in rural older persons and that the prevalence of sarcopenia in this area might be effectively reduced by improving NL.

Households with high levels of education and high monthly incomes typically have higher levels of nutritional knowledge(Reference Dallongeville, Marécaux and Cottel40). Education levels are thus positively associated with NL(Reference Aihemaitijiang, Ye and Halimulati41), and those with low monthly incomes typically have low levels of NL(Reference Camargo, Ramirez and Gajewski42). High levels of household income and education are also associated with a lower prevalence of sarcopenia(Reference Wan, Hu and Li43). The results of the interaction also showed that higher NL in older persons with relatively higher education could synergistically reduce the risk of possible sarcopenia in older persons. Thus, the educational and material advantages of adults in urban areas are also associated with a lower risk of sarcopenia. So, in the present study, NL was significantly and negatively associated with sarcopenia only in older adults with low educational attainment with monthly incomes of < 3000 RMB.

Having chronic diseases also affects the associations between NL and possible sarcopenia in older individuals. At least one study revealed a negative association between NL and multimorbidity, with low levels of NL associated with unhealthy dietary patterns and nutritional status and high levels of NL associated with a lower risk of multimorbidity(Reference Aihemaitijiang, Ye and Halimulati41). Additionally, muscle loss is a common manifestation of a variety of chronic diseases, such as chronic kidney disease(Reference Sabatino, Cuppari and Stenvinkel44), chronic liver disease(Reference Allen, Quinlan and Dhaliwal45), CVD(Reference Damluji, Alfaraidhy and AlHajri46) and cancer(Reference Peterson and Mozer47). Thus, older adults with chronic diseases are more susceptible to possible sarcopenia, a result generally consistent with our findings. Because older individuals without chronic diseases have greater muscle mass and strength(Reference Sinclair, Abdelhafiz and Rodríguez-Mañas48), a lower incidence of sarcopenia and superior overall health, the effects of improving NL on sarcopenia are noticeably less pronounced in such individuals. Our study suggests that NL is negatively associated with possible sarcopenia only in older adults with chronic diseases. Further analyses revealed the interaction between chronic disease and NL on possible sarcopenia: having high NL and having a chronic disease were synergistically associated with a lower incidence of sarcopenia. Moreover, some studies have revealed that the self-management of chronic diseases improves quality of life(Reference Allegrante, Wells and Peterson49). As the Chinese proverb says, ‘A long illness makes a good doctor (i.e., capable of handling their illness).’ Older adults with chronic diseases tend to pay more attention to their nutrition and diet, increasing the influence of NL on sarcopenia. Hence, enhancing NL may enable older individuals with chronic diseases to better manage the risks of sarcopenia.

Our study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design precluded indicating causality. Second, although we have conducted uniform survey and measurement training to control the quality of survey, there may still be some recall bias in self-reported data. Third, sarcopenia was screened and identified primarily by the SARC-F questionnaires, but not an objective measurement and clinical diagnosis. The urban–rural difference in the prevalence of sarcopenia could be due to the use of the questionnaire.

Conclusions

High NL is associated with a low risk for possible sarcopenia. Our results indicate that improving NL may be an effective method of controlling sarcopenia in older adults. However, the association between NL and the incidence of possible sarcopenia varied across residence location, education level, monthly income and chronic disease status. Our findings suggest that greater educational efforts should be targeted at rural, less-educated, lower-income and chronically ill older adults when developing intervention measures to prevent sarcopenia.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711452400268X

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the contributions and cooperation of all participants in this study.

This work was supported by the 512 Talent Training Project of Bengbu Medical College (BY51201203) and the Natural Science Foundation of the Anhui Provincial Educational Committee (KJ2019A0302, 2022AH040217)

J. D.: Conceptualisation, data curation and writing—original draft preparation. Y. C.: Methodology. L. Y.: Visualisation and investigation. Y. S.: Supervision. X. T.: Software and validation. X. H.: Software and validation. H. L.: Design and writing—review and editing.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.