Introduction

The number of diagnoses has increased substantially. In the 18th century, 2400 diseases were documented.Footnote 1 Today, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD 11) consists of approximately 55,000 unique codes for disease. Clearly, diagnoses are action-guiding for healthcare professionals, and they provide explanations and consolation to patients. Technological developments in a wide range of fields have vastly improved diagnostic capabilities. Evermore, conditions can be detected and predicted earlier than ever before.Footnote 2

At the same time diagnoses have been expanded to phenomena that are less closely connected to pain and suffering than before.Footnote 3 Examples include risk factors for disease (e.g., hypertension), indicators (e.g., prostate-specific antigen, PSA), precursors to disease (e.g., to cancers),Footnote 4 , Footnote 5 and behaviors (e.g., ADHD). Accordingly, medicine is accused of overdiagnosing, that is, diagnosing conditions that never would develop to experienced symptoms, disease, or death,Footnote 6 , Footnote 7 and for low-value diagnostics, that is, diagnoses that do not change the clinical pathway of patients or improve their health.Footnote 8 , Footnote 9 , Footnote 10 , Footnote 11 The phenomenon of “diagnostic inflation” has been identified and scrutinized.Footnote 12 , Footnote 13 , Footnote 14 , Footnote 15 There is also “diagnostic bending” analogous to “diagnostic creep”Footnote 16 and “fake diagnosis”Footnote 17 and unnecessary diagnoses due to excessive imaging.Footnote 18 Furthermore, it has been stated that there is a “compulsion for diagnosis.”Footnote 19 Moreover, reassessment, reevaluation, and re-diagnosis studies show that the criteria for diagnoses do not always hold.Footnote 20 , Footnote 21 , Footnote 22 , Footnote 23 Hence, there appears to be an increasing acknowledgement that too many persons are given or hold diagnoses they should not have (according to current diagnostic criteria).

There have been several strong reactions and campaigns against too many diagnoses and associated treatments. The Choosing Wisely Campaign, Too Much Medicine (British Medical Journal), Smarter Medicine movement, Prudent Health Care, Slow Medicine, and Do Not Do (NICE) are a few examples.Footnote 24 , Footnote 25 While most efforts are directed at reducing the number of diagnoses assigned to persons (i.e., withholding diagnoses), only a few efforts are directed towards removing diagnoses, (i.e., withdrawing diagnoses). Examples of initiatives to remove diagnoses are directed at: undiagnosing,Footnote 26 , Footnote 27 dediagnosing,Footnote 28 , Footnote 29 , Footnote 30 diagnosis review,Footnote 31 and replacing diagnoses with risk predictions.Footnote 32

However, it appears to be quite difficult both to withhold and withdraw diagnoses even if they are unwarranted. By unwarranted diagnoses, we mean diagnoses that do not satisfy professionally accepted diagnostic criteria such as they appear in textbooks, disease manuals, or guidelines. Accordingly, the main objective of this paper is to investigate the ethics of withholding and withdrawing unwarranted diagnoses. First, we investigate whether there are ethical aspects of diagnoses that make it difficult to withhold and to withdraw unwarranted diagnoses. Then we scrutinize whether there are psychological factors making it difficult to withdraw and to withhold such diagnoses. Lastly, we investigate if there are any differences between withholding and withdrawing treatment and withholding and withdrawing unwarranted diagnoses, using the withholding-versus-withdrawing treatment (WvWT) debate in medical ethics as a backdrop.

Does the Moral of Diagnoses Make it Difficult to Withhold or Withdraw Unwarranted Diagnoses?

Diagnoses have many functions with moral implications. For example, diagnoses have explanatory powers, as they can explain an unwanted situation to patients and their proxies.Footnote 33 This can give relief and decrease distress and anxiety, as diagnoses often reduce uncertainty. Additionally, diagnoses provide attention from healthcare professionals and give access to healthcare services. Morally, diagnoses direct actions in healthcare, for example, treatment, care, and palliation. Diagnoses can also assign social rights, such as sickness benefits, and freedom from social obligations such as work, attributed by sick leave.Footnote 34

On the personal level diagnoses influence a person’s identity constructions, as they influence their self-conceptionFootnote 35 and life prospects.Footnote 36 The diagnostic moment can mark a boundary and divide a person’s life into “before” and “after.”Footnote 37 Diagnoses can also induce worries, anxiety, stigma, suffering, poorer self-related health, and discrimination.Footnote 38 , Footnote 39 , Footnote 40 Relatedly, diagnoses imply status and prestige as some diagnosed are possessing higher prestige amongst healthcare professionals than others.Footnote 41

According to the functions of diagnoses, there are many reasons both to give and remove diagnoses. Table 1 provides an overview of the functions of diagnoses and possible consequences related to each function depending on whether the diagnosis is given or removed.

Table 1. Possible Consequences Related to the Various Functions of Diagnoses Depending on Whether the Diagnosis Is Given or Removed

As can be seen from Table 1, there are positive and negative sides of both giving and removing diagnoses. The balance may be determined quite differently for different conditions in different individuals in different contexts. However, the (many good) moral effects can explain why it can be difficult to withhold diagnoses and why they are maintained even if they are unwarranted, for example, because they provide attention and care, access to (appreciated) healthcare services, explanations and (positive) identity, and freedom from social obligations. Hence, the morals of diagnoses may make it difficult both to withhold them and to withdraw them, even in cases where they are not warranted (or no longer warranted).

Do Psychological Mechanisms Make it Difficult to Withhold or Withdraw Unwarranted Diagnoses?

Both patients and healthcare professionals can be affected by psychological mechanisms regarding the withholding and withdrawing of diagnoses. Patients may have strong expectations to healthcare professionals and to the healthcare services, to provide them with diagnoses (and treatment) for their conditions. These expectations may bias the withholding of diagnoses.

Due to several effects that are well described in behavioral economics and psychology, it appears more problematic to take something away from people than it is to give them something. These are mechanisms that may bias the withdrawal of diagnoses. The endowment effect makes people evaluate things they have more highly than they would evaluate the same things if they did not have them, that is one can experience an emotional attachment.Footnote 42 As diagnoses become identity and membership markers, it is not a simple matter to remove them. Moreover, loss aversion may also make people disvalue losing diagnoses.

Correspondingly, anchoring effects and status quo bias (SQB), which may result from aversion to change, also make it difficult to change conceptions and behaviors.Footnote 43 Extension bias, the perception that more is better than little, can also hamper the withdrawal of diagnoses.Footnote 44 These three mechanisms may influence both patients and healthcare professionals and can oppose the withdrawal of diagnoses.

Ample diagnostic tools make it easier to give rather than to withhold (or remove) diagnoses, for example, due to availability heuristics. Footnote 45 Some mechanisms in healthcare professionals may play a role both in opposing withholding and withdrawing of diagnoses: aversion asymmetry according to which it is “worse to overlook than to overdo” diagnoses, anticipated decision regret according to which the fear of doing too little is greater than the fear of doing too much, and aversion to risk and to ambiguity according to which not giving or upholding diagnoses may introduce uncertainty.Footnote 46

The imperative of action, that is action is better than inaction, may hinder a healthcare professional’s withholding of diagnoses.Footnote 47 This is also expressed in “better safe than sorry” attitudes in diagnostics and in proverbs in diagnostics, such as “scan because you can.”Footnote 48 Furthermore, the focusing illusion may play an important role, as healthcare professionals may focus too much on correct diagnosing and the corresponding treatment or procedure, rather than what matters for the patient.Footnote 49 , Footnote 50 Related is the prominence effect according to which correct diagnosing and treatment become more important than the consequences or outcomes for the patient.Footnote 51 Accordingly, there appears to be stronger drives towards setting than removing diagnoses.

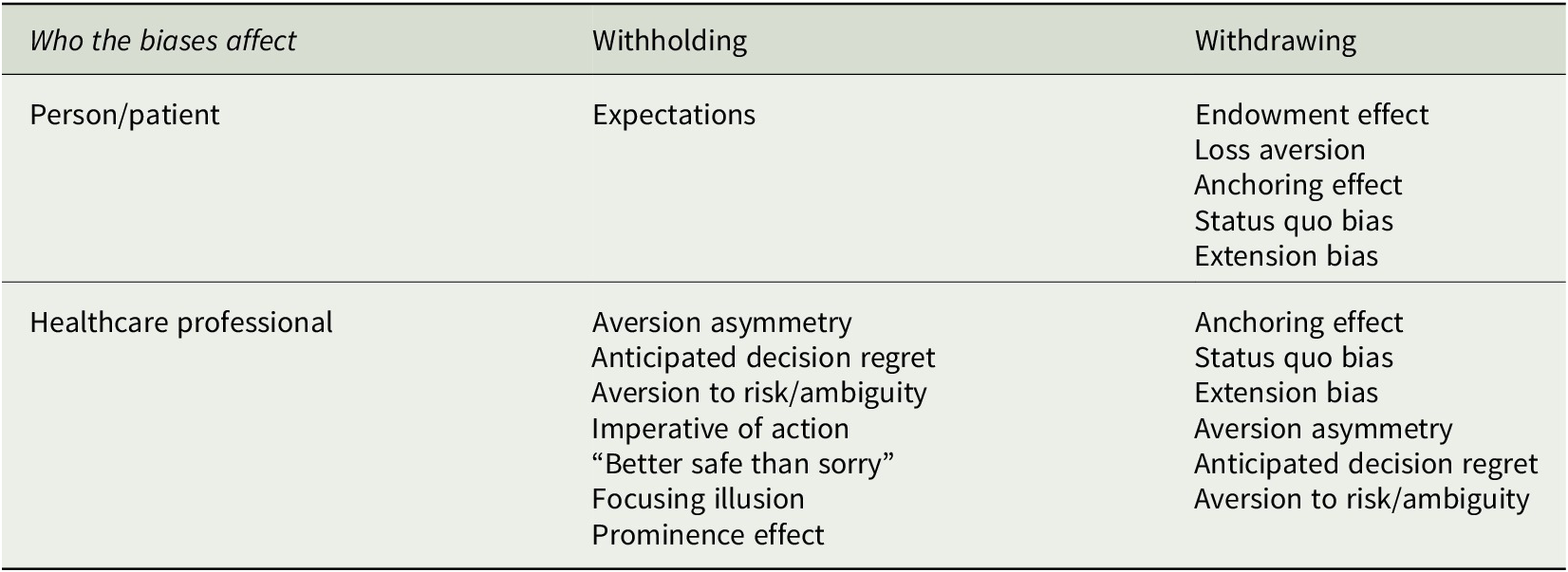

Table 2 summarizes how some biases can hinder the withholding and the withdrawing of unwarranted diagnoses. These and many other biases influence priority setting.Footnote 52 It is important to acknowledge that the biases can drive excessive diagnosing and make it difficult to disinvest, to de-implement procedures, and to remove unwarranted diagnostics.Footnote 53

Table 2. Summary of Some Biases that Can Oppose the Withholding and the Withdrawing of Unwarranted Diagnoses

In sum, there are psychological mechanisms both affecting healthcare professionals and patients that make it difficult both to withhold and to withdraw unwarranted diagnoses. This short review of biases may indicate that it is more difficult to withdraw than to withhold diagnoses. Let us therefore briefly investigate the WvWT debate in medical ethics. Are the ethical aspects that make healthcare professionals find it more difficult to withdraw than to withhold treatment relevant when withholding and withdrawing unwarranted diagnoses?

Withholding and Withdrawing Treatment versus Withholding and Withdrawing Unwarranted Diagnoses

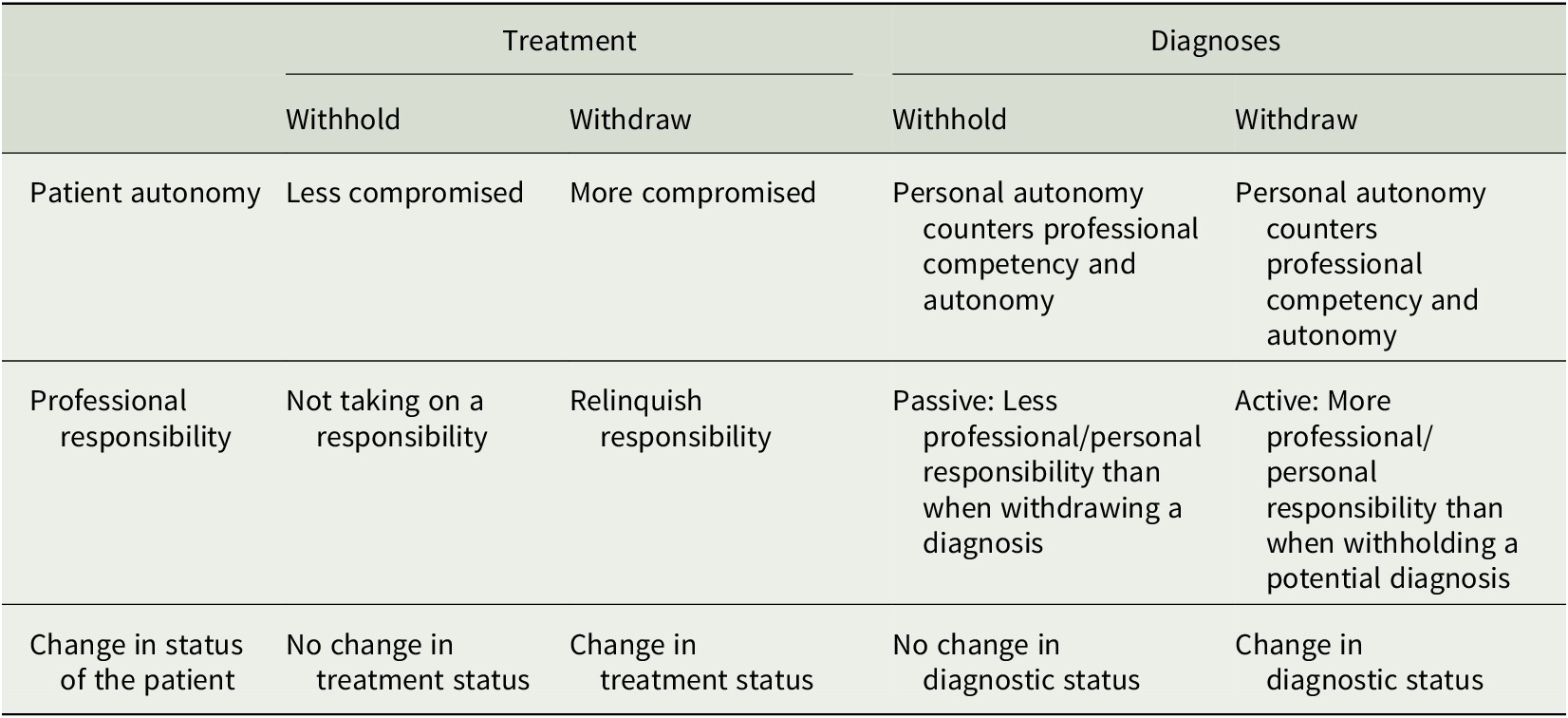

While the so-called equivalence thesis (ET) claims that to withdraw treatment is morally equivalent to withhold treatment,Footnote 54 others have argued that there seem to be three crucial differences between withholding and withdrawing: autonomy, responsibility, and the status of the treatment.Footnote 55 This is known as the WvWT debate in medical ethics.Footnote 56 Let us briefly investigate its relevance for the withholding versus the withdrawing of unwarranted diagnoses.

First, autonomy can be compromised differently in cases of withdrawal and withholding treatment. As argued: “the autonomy of a patient can be compromised more by physicians withdrawing than withholding treatment, since to stop existing treatment that the patient has attached further activities and life paths to can be more intrusive than not to start new treatment options.”Footnote 57 Accordingly, the removal of a diagnosis that is not warranted may change the life plans of the patient, but it may not change their health status. If the patient wants to retain the diagnosis, and the physician wants to withdraw it, the patient’s autonomy is violated. However, the person cannot claim a diagnosis that is not medically warranted. Here the patient’s autonomy meets the professional competency (and autonomy). When the person wants a specific diagnosis that is not warranted, but the professional withholds it, the same situation occurs. Personal autonomy counters professional competency (and autonomy). Hence, the difference in autonomy that is identified in treatment does not seem to be so pronounced in diagnostics.

Moreover, the way and degree diagnoses affect the individual’s identity construction, and/or become membership markers, affects how the patient’s autonomy is influenced. When the diagnosis affects the identity positively, for example, if a diagnosis brings with it membership in a network or organization that becomes crucial to the individual’s identity, withdrawing it can compromise patient autonomy more than withholding a hypothetical diagnosis. When the diagnosis involves an identity that has a negative connotation for the individual, both withholding and withdrawing the diagnosis will positively affect their autonomy.

According to the second argument for a difference between withholding and withdrawing treatment, professional responsibility is different in the two cases. To withdraw treatment is to relinquish responsibility that is established through a patient-physician relationship; the same is not paralleled in withholding treatment.Footnote 58 While the professional responsibility not to give a diagnosis that is not warranted basically is as strong as the responsibility to remove a diagnosis that is not warranted, healthcare professionals may feel themselves more obligated by an existing diagnostic status. Hence the professional responsibility may be perceived as greater when withdrawing than when withholding an unwarranted diagnosis.

Third, the status of the treatment is different in the two cases as “to continue ongoing treatment has another status for the patient than to embark on a new treatment.”Footnote 59 The same appears to be the case for withholding and withdrawing diagnoses. When withholding a diagnosis, the status does not change for the patient. When withdrawing a diagnosis, the status changes (from having a diagnosis to not having it). Table 3 sums up the differences in effects of withholding and withdrawing treatment and diagnoses, on patient autonomy, professional responsibility, and change in status of the patient.

Table 3. Differences in Effects of Withholding Versus Withdrawing Treatment and Diagnoses, on Patient Autonomy, Professional Responsibility, and Change in Status of the Patient as Described in Footnote Note 55, Ursin (2019)Footnote 60

Discussion

The number of diagnoses and the number of persons having diagnoses have increased substantially. Unfortunately, not all of these diagnoses are warranted according to professional standards and criteria. Hence, it is an ethical challenge to give and uphold diagnoses that are not warranted. In this article, the ethics of withholding and withdrawing unwarranted diagnoses have been investigated through three approaches.

There seem to be many moral aspects of diagnoses that make it difficult to withhold and to withdraw diagnoses even if they are unwarranted. Additionally, there are psychological mechanisms, biases, both in patients and healthcare professionals, that can hamper both the withdrawal and the withholding of unwarranted diagnoses. A wise oncologist once said, “The hardest thing in medicine is to do nothing,”Footnote 61 which may be an illustrative expression of this fact. However, our short analysis of the biases indicates that it is more difficult to withdraw than to withhold diagnoses.

There are certainly many challenges with the equivalence thesis and the WvWT debate.Footnote 62 Here we have only applied one approach, and other approaches are warranted and welcome. Nonetheless, it does not seem obvious that the ET holds in the field of diagnoses, as we have pointed to some differences between withholding and withdrawing diagnoses. While the differences between withholding and withdrawing appear to be less pronounced in diagnosis than in treatment, our brief analysis of the WvWT debate indicate that it is ethically more challenging to withdraw than to withhold an unwarranted diagnosis.

In referring to the WvWT debate, we have adopted one of its inherent assumptions, that is, that patient autonomy is compromised both in withholding and withdrawal of treatment.Footnote 63 This stems from the fact that the WvWT debate has its origins in intensive care medicine. However, this assumption does not necessary hold for other settings, such as compulsory treatment in psychiatry where withdrawal of treatment can increase autonomy.

We have referred to professional standards when defining unwarranted diagnoses. There are, of course, debates about such standards, which develop over time. New knowledge and technology make some diagnoses obsolete.Footnote 64 There is also a wide range of diagnoses that are not correct, for example, due to false-positive test results, erroneous application of diagnostic criteria, overdetection, overdefinition, and overdiagnosis. However, these are hard to detect and not (often) relevant to the situation of withholding or withdrawing unwarranted diagnoses. Accordingly, they are excluded by our clause referring to professional standards.

Conclusion

The objective of this study was to investigate the ethics of withholding and withdrawing unwarranted diagnoses. First, we found that the moral effects of diagnoses can explain why it can be difficult to withhold diagnoses and why they are kept even if they are unwarranted, for example, because they give attention and care, access to (appreciated) healthcare services, explanations and (positive) identity, and freedom from social obligations. Hence, the morals of diagnoses may make it difficult both to withhold them and to withdraw them, even in cases where they are not warranted. Second, we identified a range of biases both affecting healthcare professionals and patients that make it difficult both to withhold and to withdraw unwarranted diagnoses. Third, we used recent elements of the WvWT debate in medical ethics to identify some relevant differences between withholding and withdrawing treatment and withdrawing and withholding unwarranted diagnoses. Accordingly, we have identified a range of factors crucial to acknowledge and address in order to reduce and avoid unwarranted diagnoses.

Conflict of Interest

We certify that there is no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this manuscript, and there are no financial arrangements or arrangements with respect to the content of this viewpoint with any companies or organizations.

Funding Statement

No funding bodies had any role in study design, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

The first author had the idea of the article and made the first draft. Both authors have contributed substantially to the content of the article and to a number of revisions. The final version of the paper has been approved by both authors and both are guarantors of the article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the paper.