Introduction

Continental shelves are increasingly recognised as important archives of the human past (Benjamin et al. Reference Benjamin, Bonsall, Pickard and Fischer2011; Evans et al. Reference Evans, Flatman and Flemming2013; Flemming et al. Reference Flemming, Çağatay, Chiocci, Galanidou, Jöns, Lericolais, Missiaen, Moore, Rosentau, Sakellariou, Skar, Stevenson and Weerts2014). The sea floor is not just a treasure chest for the history of seafaring; it also preserves a record of the vast periods of time when the continental shelves were dry land. Sea levels during the past million years have rarely been as high as they are today; and for hundreds of thousands of years, the continents were substantially larger (Flemming et al. Reference Flemming, Çağatay, Chiocci, Galanidou, Jöns, Lericolais, Missiaen, Moore, Rosentau, Sakellariou, Skar, Stevenson and Weerts2014). Recent finds of hominin fossils as far apart as the North Sea and Taiwan testify to the potential of the shelf record (Hublin et al. Reference Hublin, Weston, Gunz, Richards, Roebroeks, Glimmerveen and Anthonis2009; Chang et al. Reference Chang, Kaifu, Takai, Kono, Grün, Matsu'ura, Kinsley and Lin2014).

The North Sea is probably one of the best-known submerged landscapes in the world (Peeters & Cohen Reference Peeters and Cohen2014; Bicket & Tizzard Reference Bickett and Tizzard2015), covering some 750000km2. The rich faunal record, mainly brought to the surface by sea-floor fishing, documents the diverse Pleistocene and Early Holocene ecosystems (van Kolfschoten & Laban Reference van Kolfschoten and Laban1995; Mol et al. Reference Mol, Post, Reumer, van der Plicht, de Vos, van Geel, van Reenen, Pals and Glimmerveen2006, Reference Mol, de Vos, Bakker, van Geel, Glimmerveen, van der Plicht and Post2008; Bynoe et al. Reference Bynoe, Dix and Sturt2016). These were exploited by early hominins from perhaps one million years ago (Parfitt et al. Reference Parfitt, Barendregt, Breda, Candy, Collins, Coope, Durbidge, Field, Lee, Lister, Mutch, Penkman, Preece, Rose, Stringer, Symmons, Whittaker, Wymer and Stuart2005, Reference Parfitt, Ashton, Lewis, Abel, Coope, Field, Gale, Hoare, Larkin, Lewis, Karloukovski, Maher, Peglar, Preece, Whittaker and Stringer2010). Neanderthal presence is evidenced by the discovery of a frontal bone and Middle Palaeolithic artefacts, such as bifaces and Levallois cores and flakes (Hublin et al. Reference Hublin, Weston, Gunz, Richards, Roebroeks, Glimmerveen and Anthonis2009; Peeters et al. Reference Peeters, Flemming and Murphy2009; Tizzard et al. Reference Tizzard, Bicket, Benjamin and De Loecker2014). Most evidence dates to the Early Holocene, including human bones, antler adzes and axes, bone and antler points, and other tools (Louwe Kooijmans Reference Louwe Kooijmans1970; van der Plicht et al. Reference van der Plicht, Amkreutz, Niekus, Peeters and Smit2016).

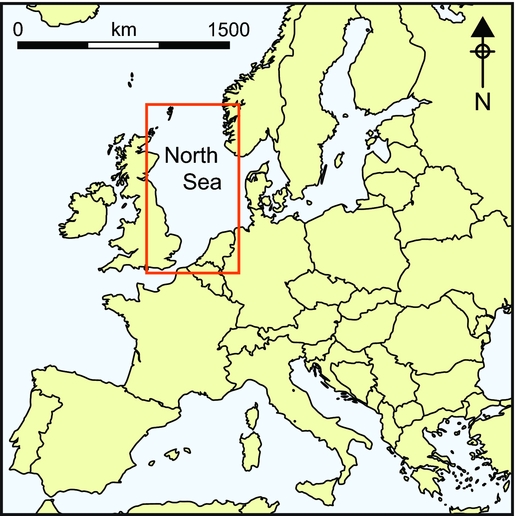

Archaeological evidence from the end of the last Ice Age, a key period in the repopulation of Northern Europe after the Last Glacial Maximum, has remained thus far almost invisible in the North Sea (Peeters & Momber Reference Peeters and Momber2014). The only artefact published is the well-known, uniserially barbed antler point, dredged up from the Leman and Ower Bank in 1931 and dated to 11740±150 BP (OxA-1950, in Housley Reference Housley, Barton, Roberts and Roe1991). A Gulo gulo (wolverine) mandible, found to the south-west of the Brown Bank and dated to 10730±60 BP (GrA-34644), represents one of the few Late Glacial sea-floor faunal remains (Mol et al. Reference Mol, de Vos, Bakker, van Geel, Glimmerveen, van der Plicht and Post2008). Here we report two finds from the Late Glacial Allerød phase of the Pleistocene–Holocene transition (Figure 1), which represent fragments of submerged biological and cultural heritage from our hunter-gatherer past: a human skull fragment and a decorated bovid bone.

Figure 1. North Sea with the location of the finds; coastline during Greenland Interstadial 1c–a (map compiled by Grimm (Reference Grimm2016), after Björck Reference Björck and Fischer1995; Boulton et al. Reference Boulton, Dongelmans, Punkari and Broadgate2001; Lundqvist & Wohlfarth Reference Lundqvist and Wohlfarth2001; Weaver et al. Reference Weaver, Saenko, Clark and Mitrovica2003; Clark et al. Reference Clark, Evans, Khatwa, Bradwell, Jordan, Marsh, Mitchell and Bateman2004; and Ivy-Ochs et al. Reference Ivy-Ochs, Kerschner, Kubik and Schlüchter2006). Find locations: 1) Eurogeul; 2) Brown Bank; 3) Leman and Ower Banks; 4) Bonn-Oberkassel and Irlich; 5) Waulsort; 6) Conty; 7) Kendrick's Cave; 8) Rusinowo.

Environmental and archaeological setting

The end of the last Ice Age is characterised by dramatic climatic fluctuations (Hoek Reference Hoek2008). After an initial rapid rise in temperature at the beginning of Greenland Interstadial 1e (Bølling, 14600–13900 cal BP), temperatures gradually dropped during Greenland Interstadial 1c–a (Allerød, 13900–12800 cal BP). The cooling trend culminated in the cold spike of Greenland Stadial 1 (Younger Dryas, 12800–11700 cal BP), after which temperatures rose quickly during the Early Holocene. The open grass steppe of Northern Europe was gradually replaced by an open birch and pine forest. Steppe fauna was replaced by species adapted to warmer temperatures and more forested environments with lakes and marshes. Global sea levels rose at an average rate of 12m per thousand years during the Late Glacial (Lambeck et al. Reference Lambeck, Rouby, Purcell, Sun and Sambridge2014).

During the Allerød, sea levels were 60–80m below the modern level (Lambeck et al. Reference Lambeck, Yokoyama and Purcell2002). Most of the North Sea was still dry land, with only the northern part of the North Sea being submerged, due to meltwater from the Scandinavian ice sheet draining through the Norwegian Channel into the northern North Sea (Boulton et al. Reference Boulton, Dongelmans, Punkari and Broadgate2001). A birch and pine forest probably dominated the higher elevations. Open herbaceous vegetation characterised the valley floors (Hoek Reference Hoek2000). Red deer (Cervus elaphus) and European elk (Alces alces) were typical herbivore species (Baales et al. Reference Baales, Jöris, Street, Bittmann, Weninger and Wiethold2002; Aaris-Sørensen Reference Aaris-Sørensen2009). During the cold spike of the Younger Dryas, the vegetation opened up again and aeolian activity increased (Hoek Reference Hoek1997).

At the end of the last Ice Age, human populations recolonised the northern regions of Europe, reaching as far north as southern Scandinavia (Housley et al. Reference Housley, Gamble, Street and Pettitt1997; Wygal & Heidenreich Reference Wygal and Heidenreich2014). Ancient mitochondrial DNA indicates that a major population turnover took place in Europe during the Late Glacial (Posth et al. Reference Posth, Renaud, Mittnik, Drucker, Rougier, Cupillard, Valentin, Thevenet, Furtwängler, Wißing, Francken, Malina, Bolus, Lari, Gigli, Capecchi, Crevecoeur, Beauval, Flas, Germonpré, van der Plicht, Cottiaux, Gély, Ronchitelli, Wehrberger, Grigorescu, Svoboda, Semal, Caramelli, Bocherens, Harvati, Conard, Haak, Powell and Krause2017). Important changes in, for example, mobility patterns, settlement structure, subsistence economy, technology and social organisation took place in this period. These were signalled by the transition from the Late Magdalenian tradition (sensu lato including Creswellian and Hamburgian) to the Federmesser-Gruppen or Arch-Backed Point groups, followed by traditions such as Ahrensburgian, Brommian, Laborian and Swiderian during the Younger Dryas. One of the most striking phenomena is the disappearance of naturalistic art (exemplified by Palaeolithic cave art) and the elaboration of geometric art that is more characteristic of the Mesolithic. The two finds described below contribute to our understanding of subsistence and art during the Late Glacial of the southern North Sea.

The finds from the Late Glacial Allerød phase

Both finds will be discussed in more detail in the following sections. Additional information on the finds as well as figures can be found in the online supplementary material (OSM).

The human parietal bone

In June 2013, the fishing vessel Scheveningen 18 retrieved a human parietal bone (Figure 2) from the sea floor just south of the Eurogeul, a channel dug in the North Sea, situated to the west of the Port of Rotterdam. It was probably eroded from local Late Glacial sediments, or from the Holocene lag deposit that contains reworked Late Glacial sediments (Hijma et al. Reference Hijma, Cohen, Roebroeks, Westerhoff and Busschers2012). The bone is dated to 11050±50 BP (GrA-58271) (Table 1).

Figure 2. The human parietal bone. Left, top to bottom: outer surface; inner surface; lateral view (scale block is 50mm). Right, top to bottom (15× magnification): bryozoan colonies (white mesh-like areas); fine pitting mid-sagittal near the parietal foramen; detail of lambdoidal suture inter-digitated with pieces of occipital bone (photographs: National Museum of Antiquities/Faculty of Archaeology).

Table 1. Radiocarbon and stable isotope data for Late Glacial remains from the North Sea (date calibration modelled in OxCal v.4.2, using IntCal13 calibration curve (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013)).

The human left parietal is well preserved (approximately 70 per cent complete), displaying weathering stage ‘1’ to ‘2’, with some cracking and only slight cortical flaking evident (Buikstra & Ubelaker Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994). Traces of small bryozoan colonies (caused by immersion in seawater) are visible. Parietal eminence thickness and cranial suture closure stage suggest that the individual was probably a young- to middle-aged adult (22– 45 years old). Slight parietal bossing is present and the superior and inferior temporal lines are not visible. These features are more consistent with a female morphology, although insufficiently diagnostic for sex estimation.

The bone displays no osseous anatomical anomalies or pathological lesions. There are, however, very fine ‘pin-head’ or shallow pits visible near the sagittal suture. A CT scan reveals no marked expansion of the diploic space or change in the organisation of the trabeculae in the area with pitting. The pitting could be indicative of a porotic hyperostotic episode experienced during subadulthood (<18 years), caused by anaemia (see full discussion in the OSM). Other possible causes of cranial vault pitting such as scurvy, rickets and scalp inflammation as a result of trauma or infection cannot, however, be excluded (Stuart-Macadam Reference Stuart-Macadam1992; Ortner Reference Ortner2003; McIlvaine Reference McIlvaine2013). The lesion is quite well healed, suggesting that, whatever the cause, the individual survived the pathological insult.

The decorated bone

The decorated bovid bone (Figure 3) was discovered by sea-floor fishing in January 2005 south-west of the Brown Bank in the southern North Sea Basin. The complex sedimentary sequence from the wider area consists of marine, brackish-marine, deltaic and fluviatile Pleistocene sediments, overlain by Holocene marine deposits and the Basal Peat Bed (van Kolfschoten & Laban Reference van Kolfschoten and Laban1995). The stratigraphic provenance of the bone is unknown, but it dates to 11560±50 BP (GrA-28364) (Table 1).

Figure 3. The decorated bovid metatarsal (photographs: National Museum of Antiquities).

The bone is a large, anterior proximal part of the right metatarsus of a bovid. The presence of a medial tubercle on the facet of the second to third tarsal is more consistent with Bison sp., but is not diagnostic (Gee Reference Gee1993: 85–86). Approximately 50 per cent of the length and less than half of the circumference have been preserved. The bone surface is relatively well preserved with several long cracks along the length of the bone as well as cortical flaking along the cracks and on the ridges of the proximal part (weathering stage 2, following Behrensmeyer Reference Behrensmeyer1978). Breakage (most probably post-depositional) occurred on several occasions following decoration of the bone. It is not clear if this represents a fragment of a bone tool (e.g. adze).

The decoration of the bone consists of five longitudinal rows of zigzags positioned on flat facets prepared by scraping the bone surface with a flint implement. The central anterior surface of the metatarsus is not decorated, but the surface is covered with shorter and longer straight to curved scratches (probably intentionally made). The pattern of decoration consists of five rows preserving 20/21, 14, 13, 12 and 7 complete or partial zigzags. The zigzags consist mostly of sequences of three parallel straight strokes, probably the result of multiple incisions with a flint implement.

Detailed analysis of one row indicates that the first few zigzags are very regular, and formed by straight, parallel, accurate strokes with similar microtraces. After the ninth series of three strokes, the cuts become more variable. The zigzags become less regular and the strokes are more variable and curved, and frequently do not overlap or connect. Despite irregularities in the incisions, great care was taken to stay within the limits of the facet. The similarity of microtraces within individual strokes suggests that this was not due to a change of incising tool, but more probably a change of gesture combined with positioning of the bone during incision.

Stable isotope analysis

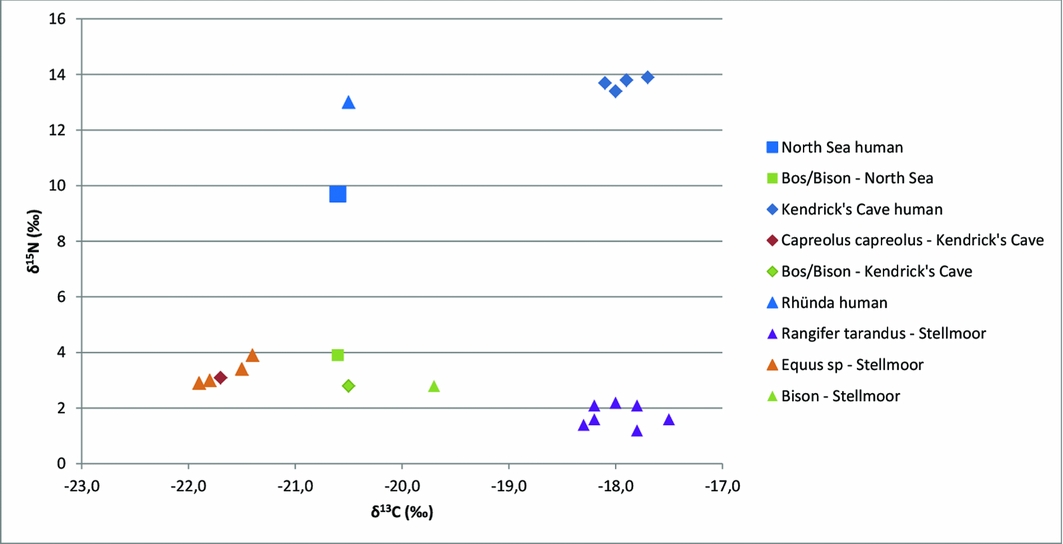

The two bones were sampled for carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) stable isotope analysis (Table 1). The stable isotope ratios can be used to reconstruct past diets and food webs (Layman et al. Reference Layman, Araujo, Boucek, Hammerschlag-Peyer, Harrison, Jud, Matich, Rosenblatt, Vaudo, Yeager, Post and Bearhop2012). In temperate environments dominated by C3-vegetation, the δ13C values vary among primary producers and primarily differentiate between the terrestrial and marine source of dietary carbon (DeNiro & Epstein Reference DeNiro and Epstein1978). The δ15N values indicate the trophic level in the food web with a stepwise enrichment of 3–5‰ from prey to predator (DeNiro & Epstein Reference DeNiro and Epstein1981; Peterson & Fry Reference Peterson and Fry1987). The stable isotope values of the bovid bone are within the expected range for herbivores during the Allerød (Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, O'Connell, Hedges and Street2009). The δ13C value of the human parietal bone is almost identical to the value of the bovid. The δ15N value is 5.9‰ higher than that of the bovid, which is relatively high for the spacing between herbivore and human.

Discussion

Late Palaeolithic human remains and art objects are rare in Northern Europe. Skeletal remains of only twelve individuals (including the parietal from Eurogeul) are known from a time period spanning two millennia. Other human remains are known from Bonn-Oberkassel and Neuwied-Irlich (Germany), Kendrick's Cave (Wales) and Waulsort Cave X (Belgium) (Baales Reference Baales2002; Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk-Ramsey, Higham, Owen, Pike and Hedges2002; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jacobi, Cook, Pettitt and Stringer2005; Pettitt Reference Pettitt2012; Holzkämper et al. Reference Holzkämper, Kretschmer, Maier, Baales, von Berg, Bos, Bradtmöller, Edinborough, Flohr, Giemsch, Grimm, Hilpert, Kalis, Kerig, Langley, Leesch, Meurers-Balke, Mevel, Orschiedt, Otte, Pastoors, Pettitt, Rensink, Richter, Riede, Schmidt, Schmitz, Shennan, Street, Tafelmaier, Weber, Wendt, Weniger and Zimmermann2014: 170–71). Bonn-Oberkassel, Irlich and Kendrick's Cave are dated to the early part of the Allerød, whereas Waulsort Cave X is dated to the boundary of the Allerød and the Younger Dryas. Given this small sample, it is perhaps noteworthy that two individuals (Eurogeul and Irlich) display pitting on the cranial vault. The Late Glacial skeleton of Villabruna 1 (Italy) provides a clear example of healed porotic hyperostosis, probably caused by a parasitic infection leading to anaemia (Vercellotti et al. Reference Vercellotti, Caramella, Formicola, Fornaciari and Larsen2010). In the Eurogeul case, the near complete healing of the lesion precludes a differential diagnosis. Nonetheless, these individuals serve as a reminder that hunter-gatherers suffered from pathological conditions, as did later agriculturalist populations.

Stable isotope values for the parietal indicate a predominantly terrestrial source of dietary protein. The δ15N value is, however, 5.9‰ higher than that for the bovid. This calls into question whether the slightly earlier bovid is representative of the herbivore fauna at the time of the human parietal. Another possibility is the human consumption of a small quantity of freshwater resources. Other evidence suggests an increase in the exploitation of aquatic, marine and freshwater resources in Late Glacial Northern Europe (Drucker et al. Reference Drucker, Rosendahl, van Neer, Weber, Görner and Bocherens2015). For example, stable isotope values for human remains from Kendrick's Cave indicate a major contribution of marine and freshwater resources, while the values of the Younger Dryas Rhünda specimen suggest systematic exploitation of freshwater resources (Richards et al. Reference Richards, Jacobi, Cook, Pettitt and Stringer2005; Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Jacobi and Higham2010; Drucker et al. Reference Drucker, Rosendahl, van Neer, Weber, Görner and Bocherens2015) (Figure 4). In addition, Federmesser sites in the Netherlands and Germany contain archaeological evidence for freshwater resources, including pike and salmon (Baales Reference Baales2002; Lauwerier & Deeben Reference Lauwerier and Deeben2011). The stable isotope values for the parietal are not, however, consistent with a large contribution of aquatic resources to the diet of this specific Late Glacial individual. That a small aquatic contribution cannot be excluded raises the problem of a possible reservoir effect on the 14C date of the parietal. Reliable information on the reservoir effect of North Sea samples is currently lacking (van der Plicht et al. Reference van der Plicht, Amkreutz, Niekus, Peeters and Smit2016), but could make the 14C date of the parietal too old by several hundred years. Overall, the data suggest that subsistence strategies in the Late Glacial were a diverse mix of marine, freshwater and terrestrial resources depending on regional conditions. The North Sea region was probably dominated by foragers with mainly terrestrial diets.

Figure 4. Stable carbon and nitrogen data for humans and herbivores from the North Sea, Kendrick's Cave and Rhünda. Data provided in OSM.

The cultural realm of these Late Glacial foragers is not well known. Compared to that of the Late Magdalenian, Late Palaeolithic art is rare and even more enigmatic. Geometric engravings on stone, on the cortex of flint and flint tools, for example, form the most widespread category of Late Palaeolithic art in Northern Europe (e.g. Arts Reference Arts and Otte1988; Baales Reference Baales2002). In addition, there are a few examples of figurative art: an amber elk figurine from Weitsche (Germany) and a bone contour découpé, possibly depicting the outline of a cervid, from Bonn-Oberkassel (Germany) (Veil et al. Reference Veil, Breest, Grootes, Nadeau and Hüls2012). Another amber figurine from Dobiegniew (Poland), depicting a horse, is similar to the Weitsche elk, but was found out of context and is undated (Veil et al. Reference Veil, Breest, Grootes, Nadeau and Hüls2012). Another surface find is a pebble retoucher engraved with two elks from Windeck (Heuschen et al. Reference Heuschen, Gelhausen, Grimm and Street2006). A sandstone shaft smoother from Niederbieber (area II) is incised with a series of lines interpreted as schematic female figures (Baales & Street Reference Baales and Street1996).

To our knowledge, there are three close parallels for the decorated bone from the North Sea (Figure 5). The best known is probably the decorated horse mandible from Kendrick's Cave (Wales), recently dated to 11050±90 BP (OxA-X-2185-26) (Sieveking Reference Sieveking1971; Bjelkhagen & Cook Reference Bjelkhagen and Cook2010). The decoration consists of four blocks of herringbone motifs and one row of ten single chevrons. The front pair of the blocks consists of seven rows of zigzags, and the rear pair has nine rows. The blocks on the left are highly regular with connecting lines, whereas the two blocks on the right contain an irregular number of strokes, several overshoots and open apexes. Another parallel was excavated from the lower level of Conty (France) and consists of a partially preserved design on deer antler (Fritz Reference Fritz2012). The radiocarbon dates for the site range between 11900 and 11400 BP (Coudret & Fagnart Reference Coudret and Fagnart1997). It is decorated with a herringbone motif with more than 34 very fine zigzag lines perpendicular to the beam. The lines are preserved on different sides of the antler. One block of five zigzags is executed vertically near the base of the antler. The third parallel is a decorated elk antler from Rusinowo (Poland) directly dated to 10700±60 BP (Poz-14541, Płonka et al. Reference Płonka, Kowalski, Malkiewicz, Kuryszko, Socha and Stefaniak2011). The ornamentation consists of six herringbone motifs and one zigzag line on one side, and eight herringbone motifs and one anthropomorphic figure on the other. The individual zigzag lines display different levels of skill, suggesting that several people created the decoration.

Figure 5. Overview of Late Palaeolithic geometric art in Northern Europe (approximate calibrated dates indicated; chronostratigraphy, climate record and archaeological periods follow Veil et al. Reference Veil, Breest, Grootes, Nadeau and Hüls2012; artefact drawings: Rusinowo after Płonka et al. Reference Płonka, Kowalski, Malkiewicz, Kuryszko, Socha and Stefaniak2011; Kendrick's Cave after Sieveking Reference Sieveking1971; Conty after Fritz Reference Fritz2012).

The decorated objects from Late Palaeolithic Northern Europe are similar in terms of the techniques used and designs executed. The design and motion patterns derived from the geometric motifs share several aspects of similarly aged Azilian engraved art from Southern Europe (Couraud Reference Couraud1985; D'Errico Reference d'Errico1994), such as repetitive gestures, a quest for symmetry, the repetition of motifs on several surfaces and preparation of the surface before engraving. It is consistent with a ‘transcultural element’ in the art of the Late Palaeolithic (d'Errico Reference d'Errico1994). The geometric motifs are linked on the one hand to a Magdalenian tradition of geometric motifs decorating bone and antler objects, such as contours découpés, semi-circular rods, spatulae, pendants and sagaies (e.g. Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1971; Fritz Reference Fritz1999). On the other hand, the medium, technique of incision, and design of chevrons and zigzags is evidence of continuity with the rich and varied geometric designs that characterise Mesolithic art of Northern Europe (e.g. Clarke Reference Clarke1936; Milner et al. Reference Milner, Bamforth, Beale, Carty, Chatzipanagis, Croft, Conneller, Elliott, Fitton, Knight, Kröger, Little, Needham, Robson, Rowley and Taylor2016). It suggests that the symbolic shift from naturalistic figurative art to abstract geometric expression took place during the Allerød period, possibly linked to profound changes in mobility and social organisation (Naudinot et al. Reference Naudinot, Bourdier, Laforge, Paris, Bellot-Gurlet, Beyries, Théry-Parisot and Le Goffic2017).

Conclusion

At the end of the last Ice Age, Northern Europe was repopulated by hunter-gatherer populations from refugia in the south. The continental shelf that is now beneath the North Sea formed a large and resource-rich land mass that was exploited by colonising forager groups with a predominantly terrestrial diet, who were connected to other populations from Wales to Poland by a shared symbolic vocabulary. The two finds presented here are significant because they date to an important transitional period when substantial climatic and environmental changes co-occurred along with a major technological and sociocultural transformation affecting hunter-gatherer societies. The terrestrial diet of the Late Palaeolithic foragers, inferred from the isotopic values of the human parietal bone, forms the baseline for a gradual increase in aquatic foods seen subsequently during the Mesolithic in the region (van der Plicht et al. Reference van der Plicht, Amkreutz, Niekus, Peeters and Smit2016). The geometric design of the decorated bovid bone is further evidence of a shift in symbolic expression from naturalistic figuration to geometric abstraction (Naudinot et al. Reference Naudinot, Bourdier, Laforge, Paris, Bellot-Gurlet, Beyries, Théry-Parisot and Le Goffic2017). As organic remains documenting this transformation are rarely preserved, the North Sea proves to be an important source for organic material culture, such as art objects and human and faunal remains. The two finds help to fill an important gap in our knowledge of the submerged biocultural heritage of the North Sea.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Radiology of the Academic Medical Centre (AMC), Amsterdam, for granting access to perform the CT scan; J. Hagoort from the Department of Anatomy, Embryology and Physiology of the AMC for creating the 3D reconstructions of the element; I. Joosten (National Heritage Agency, Amsterdam) for access and support with use of the Hirox microscope; E. Mulder (Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden) for access and use of the Nikon stereomicroscope; J. van der Deijl (Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden) for help with the initial description of the parietal bone; W. Prummel (Zwolle) and A. Ramcharan (Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden) for assistance with the initial description and determination of the decorated bone; J. Porck for Figures 1 and 4; A. Hoekman and K. Post (North Sea Fossils, Urk) for the donation of the parietal bone to the National Museum of Antiquities (Leiden); and finally, thanks to the reviewers for the helpful, critical and constructive comments.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.195