During the year 1930, D. G. Watson, the inspector-general of police for the minor stateFootnote 1 of Indore in South Asia, inaugurated a new system of police border patrols as a permanent feature of police work in the state. The patrols were part of the central government's efforts to tackle a perceived rise in ḍakaitī (anglicized as ‘dacoity’, i.e. banditry) and related ‘criminal’ activities, such as thefts, robberies, burglaries, and cattle-lifting, committed by ‘professional’ bands of ḍakait (‘dacoits’, or bandits) and ‘criminal tribes’, who were operating at Indore's peripheries and in the wider region of Malwa, central India. According to Watson,

These ‘fighting patrols’ can immediately engage any dacoit gang which may be found; and, at other times, produce a marked moral effect by showing themselves continually on the border, day and night, for continuous periods of about ten days in every fortnight. Criminals, instead of knowing that one Constable is to be found at a certain fixed Chowki [caukī, the post of a watchman/constable], do not know where or when an armed party of Police, never less than five strong, may appear.Footnote 2

Patrolling, as an instrument designed to circumscribe ḍakaitī and other ‘criminal’ activities, also served as a novel and tangible performance of Indore's territorial jurisdiction, as well as an opportunity to undermine existing patterns of ‘distributed’ or ‘fragmented’ sovereignty at Indore's peripheries.Footnote 3 Such patterns were particularly palpable in the long-established patronal connections that existed between local powerholders and irregular state representatives, on the one hand, and those groups labelled as ‘criminal’ gangs and ḍakait, who performed the twinned activities of plunder and protection within the local political economy, on the other. The first part of this article reveals how such connections illustrated the relative autonomous authority of the former within Malwa's political economy since the eighteenth century. The second section focuses on how the inauguration of patrolling, when coupled with other directives and wider policework undertaken by Indore state authorities, served as a manifestation of attempts to centralize sovereignty, whilst also aspiring to undermine the autonomous reach of local state actors.Footnote 4 Finally, the third section explores the continuing existence of such connections and autonomy during the 1930s, despite the best efforts of the central government. In doing so, this article reconsiders wider scholarly conceptualizations of colonial knowledge, state–society relations, and modern sovereignty by recentring marginalized communities such as ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’ within the historical record.

When ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’ have previously served as the subject of historical analysis, it has primarily been as part of a postcolonial critique of their representation and categorization as hereditary, intrinsic, and/or cultish lawbreakers within the legal and ethnographic frameworks of the colonial state.Footnote 5 Such scholars have suggested that this was part of a wider essentialization of caste and tribe in South Asia produced by colonial forms of knowledge.Footnote 6 However, over the last two decades, another set of academics have questioned the extent to which the categories of caste, ‘tribe’, and hereditary criminality were entirely ‘invented’ or ‘imagined’ by the colonial state, and have instead emphasized continuities back to the eighteenth century and before.Footnote 7 Such accounts simultaneously emphasize the historical and geographical situatedness of ḍakaitī, plundering, and marauding, embedding these practices as integral, institutionalized components of the moral and political economy of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century northern and central India, rather than as ‘crimes’ per se.Footnote 8 This article likewise illustrates how such activities were rooted in the specific socio-political circumstances of Indore's territorial peripheries. Significantly, it underscores how the institutionalization of plundering, marauding, and banditry was not confined to pre-colonial politics and the era of colonial pacification up until 1857. Instead, it demonstrates how they continued to be apparent at Indore's borders well into the twentieth century.Footnote 9 As this article goes on to elucidate, recognizing the continuing prevalence of these activities also has important implications for understanding the enduring fragmentation of sovereignty during an era still too often depicted as one of increasingly consolidated imperial and national authority.

This article simultaneously corresponds to a more recent body of academic work that looks to critique an older emphasis on colonial legal and ethnographic frameworks, principally through an analysis of interactions between ‘criminal tribes’ and local state structures and representatives. Sarah Gandee and William Gould have emphasized ‘the disjuncture between forms of “colonial” knowledge which structured legal categorization and the everyday negotiations and contestations of the same’.Footnote 10 In consequence, they have sought to move beyond older subaltern studies paradigms that searched for the ‘autonomous’ agency of marginalized communities almost entirely through histories of confrontation with, and resistance to, the state.Footnote 11 Of course, this is a common refrain not limited to late colonial South Asia. Those working on borders and/or bandits in other contexts have often emphasized how these spaces and activities were indicative of state evasion or subversion.Footnote 12 Yet such histories have frequently overlooked the extent to which local state actors and such marginalized and ‘criminal’ communities could also be intertwined. Alf Gunvald Nilsen has pointed out how the bhīl (bhil) community of western India, who were subjected to a British campaign of pacification in the early nineteenth century, increasingly came to consider ‘the state…in disaggregated terms, as an institution consisting of hierarchically ordered echelons’.Footnote 13 This article recognizes the significance of such a disaggregated perspective when focusing upon evidence of enduring affinities between ḍakait and local state actors at Indore's peripheries. It draws upon a now well-established literature to highlight the impact of the enmeshment of ḍakait within the ‘everyday’ state, rather than dwelling upon their abstract legal status as hereditary ‘criminals’.Footnote 14

In fact, ḍakaitī and its associated activities could be conducted with the encouragement and assistance of the state's ‘everyday’ or ‘profane’ echelons and representatives, rather than being organized solely in opposition to the idea of a ‘sublime’ Leviathan.Footnote 15 This is not to create a false contrast between corruption at the local state level and the aloof and impartial legality of those at its apex. Rather, the evidence from archival materials within this article also corresponds to more recent scholarship on the state in South Asia, which captures how it suits particular interests to imagine a ‘hierarchical vision of the state’ at certain opportune moments.Footnote 16 In this context, individuals such as Watson, whilst inscribing his police reports, could frame local state actors as immersed in criminality, in an effort to champion the further centralization of state power.

Understanding the state in a disaggregated fashion simultaneously demonstrates the continuing dynamism of both ḍakait and local powerholders within fragmented sovereign configurations. In exploring these long-standing patterns, particularly as they continue to appear during the 1930s, this article engages with recent scholarship that challenges traditional presumptions about the increasingly unitary and integrated nature of modern sovereignty based around the bounded territorial twentieth-century state.Footnote 17 It draws much of its intellectual sustenance from both Eric Beverley's and Thomas Blom Hansen's challenges to ‘the presumption of a rapid and thorough transition from complex, multiple and malleable forms of political power to effectively consolidated state sovereignty’ in imperial and global contexts, which is conventionally understood as developing under the monistic stimulus of colonial rule.Footnote 18 Their work, based upon South Asian examples, can be situated within a wider trend that recognizes the persistence of fragmented forms of sovereignty in other imperial, postcolonial, and global contexts.Footnote 19 Although South Asian scholarship has for some time recognized the durability of other spaces and dominions existing alongside, beyond, or despite the authority of the Raj, these peripheral spaces are too often treated as diminishing ‘anomalies’, outliers, or ‘irreducible fiction[s]’ in the face of the ‘ultimate sovereignty’ of British colonialism.Footnote 20 Rather, in much the same way as Beverley describes the minor state of Hyderabad to the south, Indore consistently acted ‘as an autonomous territorial state’ in a complex political geography of multiple minor sovereign jurisdictions in late colonial central India.Footnote 21

For this article, recognizing the enduring fragmentation of sovereignty is particularly significant when considering shifting conceptions as to who constituted the ‘criminal tribe’ and ḍakait across these boundaries. The sanorhiyā, for example, were a community notified as a ‘criminal tribe’ in the United Provinces of British India during this period. Yet, when referring to the sanorhiyā, the 1931 census for the Central India Agency could simultaneously narrate how

the Rani [rānī, i.e. queen or princess, or ruler, referring to Ladai Sarkar (r. 1848–74)] of Tikamgarh [i.e. the minor state of Orchha], was apparently much surprised that the British Government objected to her subjects ‘proceeding to distant districts to follow their occupation stealing, by day, for a livelihood for themselves and families both cash and any other property that they could lay hands on’.Footnote 22

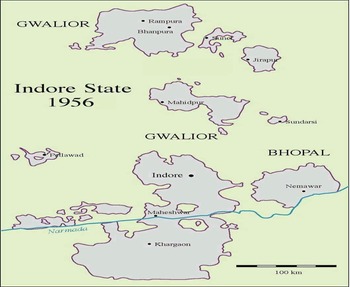

A uniform stigma of illegality across an inflexible category of ‘criminal tribes’ was thus in constant tension with the development of ‘myriad, layered and contextual identities’ amongst these communities during their interactions with late colonial India's fragmented sovereign jurisdictions.Footnote 23 This article focuses on the activities of ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’ within two zilā (districts) at the peripheries of Indore's territorial domain, as evidence of a further layer of autonomy that undermines the notion of consolidated sovereignty within such configurations. Indore itself was an equally uneven terrain, particularly at its borders: its disparate territories, disaggregated administration, and alienated landsFootnote 24 ensured that power continued to be dispersed and contested amongst a variety of autonomous entities within this minor state (Figure 1). In this context, patrolling and wider policework at the border functioned as a performance of ‘territorialization’, through which Indore's central authorities sought to materially demarcate its exclusive jurisdictional and inalienable proprietary remit.Footnote 25 Despite such efforts, the actions of ‘criminal tribes’ and ḍakait, in tandem with those of local and irregular state actors, illustrates the persistence of more intricate and flexible forms of political power. Evidence of these alternative manifestations of fragmented authority provide interruptions in the supposedly inexorable and teleological march of an increasingly consolidated sovereignty under colonial influence. Before embarking on any further explication of the ways in which the Indore government attempted to circumvent alternative allegiances, it is therefore necessary to conceptualize the longer history of this space, its inhabitants, and their relationships with one another.

Figure 1. Map of Indore State, 1956. Dr Andreas Birken, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE.

I

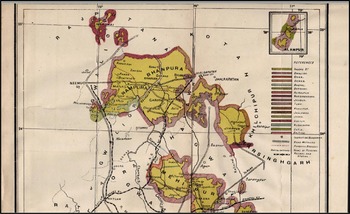

Throughout the annual Indore police administrative reports published during the 1930s, the activities of ‘criminal’ gangs were described as particularly prevalent in its isolated and fragmented Northern Range. This Range consisted of various tracts of territory that formed part of the Rampura-Bhanpura and Mehidpur zilā (or districts).Footnote 26 The 1930 report, for example, cited Rampura-Bhanpura as ‘the only district in which several dacoities have occurred within a well-defined area without detection or prevention during the last two years’. In part, this was blamed on the leadership of the district superintendent of police in the zilā, whose performance had ‘left much to be desired’.Footnote 27 But it also owed something to Rampura-Bhanpura's specific situational and historical backdrop, which captured in microcosm the complexities of late colonial Malwa's political geography. Located in the far north-west of the Malwa plateau, Rampura-Bhanpura was entirely cut off from the rest of Indore state territories, including the Central Range to the south, where Indore city and the state's administrative headquarters were located. The district itself was constituted by four discrete territorial blocks, described in what follows from east to west: the isolated Jirapur parganā (sub-district); another discrete parganā centred on the town of Sunel; a larger block comprised of the four sub-districts of Bhanpura, Garoth, Manasa, and Rampura; and a final separate parganā of Nandwai. In turn, some of these parganā – Manasa, Nandwai, and Sunel – also incorporated villages and/or groups of villages for administrative purposes that were otherwise geographically removed from the rest of the parganā, forming tiny enclaves in other territories. Rampura-Bhanpura zilā was therefore surrounded and intermixed with territory under the jurisdiction of other minor states, such as Gwalior, Jaora, Khilchipur, and Tonk in central India, and Jhalawar, Kotah, Pratapgarh, and Udaipur in Rajputana (Figure 2).Footnote 28

Figure 2. Map of Rampura-Bhanpura and Mehidpur zilā within Indore state, 1929. Source: ‘Sketch map of Indore state’, in R. Sarup, Final report on the land revenue settlement of Holkar state, Indore (central India) (Allahabad, 1929), p. 1.

Rampura-Bhanpura's complex territorial jigsaw also encapsulates the unstructured nature of Indore's derivation and development. Indore had first emerged in the early eighteenth century as a loose assortment of rights over the collection of village tributes in Malwa. These rights had been granted on a hereditary basis to the Maratha military general, Malhar Rao Holkar (1693–1776), who had achieved success in the service of the Peshwa, the high-caste ruler of the Maratha polity based in the western Indian city of Pune.Footnote 29 Significantly, the rights to revenue collection granted to Holkar and other Maratha military generals (such as Bhikaji Scindia of Gwalior) were not based in contiguous territories. Rather, the Peshwa divided them across different villages in Malwa, aiming to diminish opportunities for the generals to build up their own independent strongholds. Despite these efforts, the descendants of Holkar and Scindia were able to increasingly assert their autonomy from Pune, particularly from the late eighteenth century onwards. This entailed the ability to grant their own rights to collect revenue to tributary rulers and landowners, indicating a further patchwork stratum of entitlements across the region. Under these circumstances, power frequently radiated out from the centre of a tributary state like Indore in an open-ended, fragmentary, and unstable fashion, dissipating as it moved further away.Footnote 30 At Indore's relational peripheries, its rights, interests, and influence over tributary rulers and landowners could often overlap with those of other proximate polities, ensuring that Malwa's pre-colonial sovereignties frequently intersected.

On paper and the map, at least, Indore's previously fluid relational boundaries coagulated after the emergence of British paramountcy in Malwa, when a new process of political territorialization was inaugurated. After Indore's final defeat by the East India Company (EIC) in 1818, Malhar Rao Holkar III (r. 1811–33) was allowed to keep his throne, title, and certain lands in central India under the treaty of Mandsaur.Footnote 31 At the same time, the British recognized many of Indore's tributaries as independent rulers, who now entered direct relations with the EIC through sanadẽ (anglicized as ‘sanads’, i.e. certificates of protection or recognition). Coupled with mapping expeditions and settlement reports, these treaties and sanadẽ firmed up absolute rights to revenue extraction through firmly demarcated territorial frontiers, simultaneously depriving Holkar of tribute previously accrued from across large swathes of central India whilst strengthening his sovereign claims within a smaller territorial domain. However, British attempts to consolidate pre-colonial sovereignties on an exclusive territorial basis paradoxically created a hotchpotch of irrational and inflexible territorial domains on the map. The haphazard boundaries and enclaves that existed in and amongst the various minor states of central India were now frozen at a particular snapshot in time, reflecting a specific socio-political situation previously defined by amorphous and overlapping relational jurisdictions.Footnote 32 In fact, Indore's borders subsequently remained steady until the late colonial period.

In one sense, the existence of different jurisdictions and state-like entities as described in the foregoing discussion was not unique to Malwa but reflected a complex sovereign mosaic commonplace across late colonial South Asia and the British imperial world more broadly.Footnote 33 Indore constituted not only, alongside Gwalior, one of the two largest states in Malwa, but was one of the most prominent of several hundred minor states that existed within India more generally. It was roughly equivalent in area to the state of New Hampshire, and with a population of over 1.3 million in 1931.Footnote 34 At the same time, Malwa's political geography, and Indore state's situatedness within it, contained further labyrinthine dimensions. Both the multitude and small size of many of Indore's former tributaries, on the one hand, and the scattered and entangled nature of these minor states and their and Indore's territories, on the other, engendered further jurisdictional complexities in the region, in a way that was generally distinct from most other parts of the subcontinent.Footnote 35 The 1931 census commissioner for central India, for example, noted the difficulties in undertaking enumerative activities given that ‘the boundaries of many States cross and re-cross in endless ways’, with some ‘States…interlaced in such a way that they are comprehensible only by studying a map’.Footnote 36 This geographical complexity undoubtedly added to Indore's difficulties in enforcing its sovereignty at its territorial peripheries during the late colonial period, whilst providing great opportunity to local powerholders and ḍakait. When considered in the context of Indore's Northern Range, for example, Watson argued that Rampura-Bhanpura's ‘scattered and isolated nature’ left it ‘specially exposed to the incursions of foreign dacoit gangs’.Footnote 37

Rampura-Bhanpura's remoteness had also traditionally provided its local powerholders with a large degree of autonomy in their internal administration. This was particularly the case for the Candrăvat rājpūt lineageFootnote 38 residing in and around the town of Rampura. The Rampura Candrăvat had been granted separate hereditary rights to land in jāgīr (an estate) by the representative of the erstwhile Delhi sultanate in Malwa during the fourteenth century, in return for pacifying the area.Footnote 39 Such autonomy was reflected in the development of other alienated jāgīr more generally across the region. Under these arrangements, jāgīrdār (large estate holders) were able to grant land to their own servicemen (what Norbert Peabody refers to as ‘jāgīrdārs of jāgīrdārs’), who in turn would conduct revenue collection and military service within their own smaller, autonomous domains on the jāgīrdār's behalf.Footnote 40 As a consequence, various ‘spheres of dominance’ emerged, descending from those nominally holding overall dominion, via jāgīrdār and zamīndār (smaller landowners), all the way down to the village ṭhākur and paṭel (landed headmen or chiefs).Footnote 41 The relative independence of the Rampura Candrăvat, for example, was apparent in their ability to grant the parvānā (licence, written authority) of zamīndārī rights over the village of Bolia (in Garoth parganā) to the representatives of immigrant kunbī (a community of cultivators) from Gujarat.Footnote 42 The Candrăvat and other rājpūt therefore often became minor potentates (or what Nicholas Dirks has described as ‘little kings’) in their own right.Footnote 43 This remained the case once Indore came to exercise a degree of authority over the region after 1748, when Holkar became involved in a factional dispute over who should succeed to the gaddī (throne) in Rampura. In return, the throne's new incumbent, Madho Singh, ‘made over this district to Holkar’ and the Rampura Candrăvat now became Indore's jāgīrdār.Footnote 44

As this episode suggests, the allegiances of local landholders and minor potentates were frequently shaped by larger patterns of conquest and rivalry in the region. When forging such alliances, estate holders such as the Rampura Candrăvat had to ‘measur[e] or estimat[e] the chances of success of the conquering power against those of the established sovereign’, so as best to protect, consolidate, and/or expand upon their holdings and rights.Footnote 45 We can read subsequent challenges to Indore's authority by the Rampura Candrăvat in this context. During the late 1780s and early 1790s, for example, Indore experienced heightened rivalry with the neighbouring Maratha polity of Gwalior, which might explain the Indore Gazetteer's references to the Candrăvat's defiance of Indore in 1787. Equally, subsequent challenges in 1821 and 1829 occurred after the establishment of wider British suzerainty in the region, to the extent that the Gazetteer records the Candrăvat as giving ‘much trouble to Holkar's officials who were constantly in collision with them’.Footnote 46 Ultimately, it was the support of the jāgīrdār and other subsidiary landowners that was traditionally required to successfully conquer and maintain control over a region, as their ‘cooperation was needed to gain access to the agrarian resource-base without which no state could survive’.Footnote 47 In this pre-colonial context, sovereignty therefore not only overlapped between polities, but across stratums within polities, between those who claimed overall dominion and those who exercised power in a sliding scale of relational domains.

The authors of the Gazetteer located the consistent challenges to the central state in Rampura within the Candrăvat's ‘exalted idea of their position’.Footnote 48 But the Gazetteer also implicitly reveals the importance of the Candrăvat's relationships with supposedly marginal and ‘criminal’ communities to their local authority. This was signified, for example, in the ceremonies associated with the ascension of members of the Candrăvat rājpūt lineage to the gaddī in Rampura, which relied upon members of the local bhīl community. The Gazetteer notes how, having ‘acquired the surrounding country from the Bhils’ in the fourteenth century, ‘[t]o this day the head of the family [of Candrăvat] on his succession receives the tika [ṭīkā; an ornamental marking worn on the forehead signifying status] from the hand of a Bhil descendant of the founder of Rampura’.Footnote 49 This close relationship between bhīl and Candrăvat rājpūt reflects the longer, shared history of mobility, banditry, and martiality between such communities at a polity's frontiers.Footnote 50 On the one hand, the emergence of ‘sedentary political formations’ in the twelfth century coincided with attempts to delineate an ‘aristocratic Rajput “caste”’ constituted by hereditary jāgīrdār, zamīndār, ṭhākur, and paṭel families. These were consistently designed to ‘exclude several groups with similar claims’.Footnote 51 On the other hand, rājpūt could also remain a fluid and malleable category of occupational and social status well into the late colonial period, capable of encompassing a wide remit of new powerholders drawn from marauding bands in central India.Footnote 52 The sondhiyā community, for example, could be described in the Indore State Gazetteer as ‘a class of notorious free-booters who infested these parts [of central India]…and carried on a work of rapine and devastation’.Footnote 53 Yet the census for the Central India Agency of 1931 also noted how sondhiyā

invariably term themselves Rajput and like to be styled Thakurs…The story runs: they fought on the side of the emperor against Aurangzeb at Fatehabad near Ujjain in 1627. They were then Rajputs, forming part of the army led by Jaswant Singh of Jodhpur. Disgraced by this defeat they dared not return home and took up their abode in the tract now known as Sondhwara. Here they inter-married with the local people and thus produced the Sondhia Rajput group. They state that Semri in Udaipur State and Dhabla and Dokhada in the Narayangarh district of Indore State are their centres and the headmen ‘Thakurs’ as they style them, of these places are looked up to as leaders.Footnote 54

That sondhiyā emphasized their status as rājpūt and ṭhākur is demonstrative of their role not just as plunderers, but also as local powerbrokers in ‘Sondhwara’, an area that incorporated parts of Rampura-Bhanpura and Mehidpur zilā.Footnote 55 A similar set of circumstances was evident amongst the bhilālā, ‘a mixed caste sprung from the alliances of immigrant Rājpūts with the Bhils of the central India hills’. Within a single colonial ethnography, they could be depicted as both ‘hold[ing] estates in Nimār and Indore [zilā in Indore]’, through which they ‘now claim[ed] to be pure Rājpūts’, and, quoting John Malcolm's Memoir of central India, as simultaneously ‘the only robbers in Mālwa whom under no circumstances travellers could trust’. Russell and Lal's account went on to describe bhilālā as ‘usually [holding] the office of Mānkar, a superior kind of Kotwār [a corruption of kotvāl, literally ‘keep of the castle’] or village watchman’.Footnote 56 That bhilālā could be represented as equally engaged in landownership, plunder, and protection within the same text points to their complex, shifting roles in the region.

As these emerging gentrified classes were gradually granted landed rights in Malwa, they also became accountable for law and order within their new autonomous domains. As the extract from Russell and Lal suggests, it was in this context that jāgīrdār, zamīndār, ṭhākur, and paṭel came to employ groups of bhīl and other communities with a reputation for plundering and protection as caukīdār (watchmen). These communities continued to undertake what amounted to local policing responsibilities on behalf of their patrons across Indore into the late colonial period. Writing in the late nineteenth century, Edward Gunthorpe of the neighbouring Berar provincial police explained the employ of pārădhī as caukīdār as an attempt by paṭel ‘[t]o save their villages from the depredations of these…classes of robbers…that their villages might be spared on payment of blackmail’.Footnote 57 This reflected the nature of village policing as a ‘racketeering trade’, in which ‘its agents posed the threat from which they protected’.Footnote 58 Equally, caukīdār could swap allegiance, break with, and turn on their patrons if other, better opportunities emerged. Significantly, regional and local powerholders continued to employ watchmen-marauders for the purposes of plundering their neighbours. The 1939 Indore police administrative report contains an account of an incident in the Tarana parganā of Mehidpur zilā, when a night-time ḍakaitī targeted a tongā (a horse-drawn two-wheeled vehicle) carrying customers from the Tarana Road railway station at Sumrakheda back to Tarana town. The ḍakaitī was ‘believed to have been committed by a gang of Pardhis [pārădhī] instigated by a Jagirdar of Gwalior State, who wanted to implicate an enemy, in whose house he “planted” some of the stolen property’.Footnote 59 Rather than an activity that can be taken as indicative of hereditary caste-based criminality undertaken by marginal communities, plundering-protection was embedded as an integral occupation within the regional political economy: ‘as a way to extract revenue, rebel against superiors, intimidate rivals, conquer lands, and ultimately found new states’.Footnote 60 What distinguished the larger eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Maratha warbands under Holkar from local gangs of watchmen was the scale and ‘degree of success’ of their marauding activities, rather than any discernible variance in the kind of actions undertaken.Footnote 61

II

By the mid-nineteenth century, the British had ruthlessly crushed any remnants of large-scale raiding associated with revenue extraction and state formation across Malwa. However, local state representatives within Indore and other ‘minor’ states in central India continued to employ watchmen-marauders and commission their plundering activities well into the late colonial period. The problem for central state authorities in Indore was that those responsible for plunder and protection, as an established form of policework at its peripheries, owed their allegiance to local powerholders, who also acted as local representatives of the state, rather than the darbār (royal court). As a result, these localized loyalties were increasingly considered a threat to emerging manifestations of central state sovereignty. In these circumstances, the inauguration of patrolling can be read as a mechanism through which the central government sought to unpick the long-standing relationships between its local representatives, wider society, and those who came to be represented in the police administrative reports as ḍakait and/or ‘criminal tribes’. Although ostensibly aimed at preventing ḍakaitī and other ‘criminal’ activities, patrolling also marked: (a) the culmination of efforts to restrict the power of Indore's jāgīrdār; and (b) the regulation of the previously autonomous activities of village paṭel and caukīdār. This section outlines these attempts to inscribe central state sovereignty more firmly at Indore's peripheries, whilst demonstrating how efforts to effectively police ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’ were considered increasingly critical to such activities.

Beyond an interest in the revenue to generate an income, and the imposition of indirect levies on customs, salt, and stamp taxes, the governmental functions of many of the smallest ‘minor’ states often remained limited across much of late colonial central India. Indore was something of an exception in that it underwent periodic processes of augmenting the central bureaucracy before and during the 1930s, akin to that described in other relatively large and habitually ‘progressive’, ‘modern’, and ‘model’ states in South Asia, such as Baroda, Hyderabad, Mysore, and Travancore.Footnote 62 These processes were often underpinned by attempts to extend the sovereign reach of the central state at its territorial peripheries, and had a substantial impact on the diminution of jāgīrdārī power. Unlike the former jāgīrdār of Indore who had been guaranteed by the British as autonomous entities in 1818 (such as the rulers of Jaora and Jhabua), those jāgīrdār that found themselves within Holkar's newly circumscribed and territorialized sovereign realm (such as the Candrăvat rājpūt) saw their opportunities for autonomous action increasingly intruded upon under the centralizing initiatives of the darbār.Footnote 63 Such constraints were at their most palpable in the restriction and resumption of several jāgīr in the Northern Range by the central government during the nineteenth century, whereby previously alienated lands were restored as khālsā (i.e. crown lands).Footnote 64 One such example was the jāgīr held by the Phanse family in Tarana parganā, which was resumed by the Indore government in 1849. This jāgīr was originally granted by Ahilya Bai Holkar (r. 1767–95) to her daughter, Mukta Bai, on her marriage to Yaswant Rao Phanse, who had come to the attention of the darbār for his role in pacifying parts of central India. The Phanse family continued to have close connections to the darbār, either through marriage or service as dīvān (chief ministers) in the early nineteenth century. However, the jāgīr was ultimately resumed ‘when Raja Bhao Phanse, who administered the state during the minority of Tukoji Rao Holkar II [r. 1844–86], finding he was unable to deal as he liked with the State revenues, attempted to create an impasse by retiring to Tarāna, taking with him the great seal of the State’.Footnote 65 As this episode suggests, the efforts of landed elites to counter the authority of central government could often result in the termination of layered gradations of sovereignty that fostered jāgīrdārī autonomy, including their ability to act as patrons towards their erstwhile watchmen and retainers.

Despite the prevalence of resumption and restriction, jāgīrdārī rights and autonomy did not disappear entirely from Indore's peripheries: the aforementioned Candrăvat rājpūt, for example, continued to hold jāgīr and local status in the vicinity of Rampura.Footnote 66 By the early 1930s, the jāgīrdārī system continued to account for around 400, or approximately one tenth, of the villages in the state, in contrast to the khālsā system which prevailed elsewhere.Footnote 67 Equally, jāgīrdār still sought to wield a modicum of autonomous power. Whilst acting as a member of the drafting committee for the 1931 Indore Land-Revenue and Tenancy Act, C. U. Wills could still comment on how ‘some members of this [i.e. jāgīrdārī] privileged class aspire to a position of independence…[separate to]…the jurisdiction of the ordinary officials of the State’.Footnote 68 It was in this context that the 1931 Act sought to introduce a whole range of further restrictions aimed at curbing any remnants of jāgīrdārī autonomy, targeting jāgīrdār's patronal connections with those engaged in plunder and protection in particular. This included granting the central government ‘authority to appoint and control the village officials (Patels, Chaukidars and BalaisFootnote 69) both in khalsa and non-khalsa villages; while section 70 enables the State to confer protection…on all tenants who hold from an “assignee”’.Footnote 70 The inauguration of patrolling at Indore's borders, including in areas that remained in jāgīr, must be considered within this wider context. Increasing attempts by the darbār to centralize sovereignty at Indore's peripheries specifically targeted the jāgīrdār's benefactory relationships with local society, including with those employed as watchmen-marauders.

Alongside the darbār's efforts to restrict the powers of its jāgīrdār, the introduction of patrolling also reflected an endeavour to enhance central oversight of village officials at Indore's peripheries. Whilst many jāgīrdār had seen their autonomy circumscribed by the early twentieth century, by contrast E. Luard and R. P. Dube were still able to describe village-level state representatives as retaining ‘a considerable amount of autonomy, every village of any size being a self-contained community, having its own headmen [paṭel], who settle all petty disputes between the villagers’.Footnote 71 In part, this owed something to the khālsā system, in which ‘[t]he remoteness of the Ruler's proprietary interest…leaves room for a Village Officer or Patel,…who is responsible for the management of the village and the collection of the rents’.Footnote 72 During the nineteenth century, village paṭel at Indore's peripheries had seen their authority in part diminished by the emergence of a class of ijārādār (revenue-farmers), who functioned as commercial middlemen between the central state and village. Ijārādār generally held contracts with the darbār to gather and deliver the revenue from certain parganā or groupings of villages within Indore, thereby replacing the paṭel in the collection of village dues. However, unlike the jāgīrdār's alienated lands, these ijārādār were not granted related administrative responsibilities or proprietorship: theirs was a purely transactional financial arrangement. It was only as the central state in Indore sought to cultivate a closer sovereign relationship with borderland societies that these middlemen were abolished under a new land revenue settlement in 1908.Footnote 73 The abolition of the ijārādār created some limited opportunities to develop prestige and standing amongst village-level paṭel, who saw their revenue-collecting responsibilities reinstated in return for a small rebate on the collections made. Under the 1931 Land-Revenue and Tenancy Act, paṭel were also reinstated with ‘a substantial watan, a plot of revenue-free land, as part of his remuneration’. As we have seen, allocating rights over land was an established pre-colonial practice, evident amongst powerholders at different layers within autonomous ‘hierarchies of rule’. These rights effectively capture the gradated nature of sovereignty in the ‘minor’ states of central India. However, in late colonial Indore, the right to grant land now came to exist solely under the remit of the darbār and cut out the sovereign power of formerly autonomous landed middlemen. In doing so, the Indore authorities hoped to create ‘a personal tie’ between the paṭel and the central state, ‘which binds him to the Maharaja [mahārājā, i.e. ruler]’. Wills, for example, hopefully suggested that ‘vis-à-vis the Government, his [i.e. the paṭel's] office should acquire a stability which will make him a useful agent of the State’.Footnote 74 Significantly, however, the renewed importance accorded to paṭel through land grants in the early 1930s also boosted their prestige at Indore's peripheries, including during their informal patronage of existing or potential caukīdār drawn from ‘criminal’ communities. In fact, the next section of this article elucidates the significance of such social status in the context of persistent patronal relations between village powerholders and plunderer-protectors, in a manner that could also paradoxically impinge upon the consolidation of Indore state's sovereignty at the border.

Beyond the paṭel's role as a village revenue official, the gradual encroachment of central authority was also apparent in the expansion of oversight regarding the prevention, detection, and punishment of ḍakaitī and related ‘criminal’ activities at the village level. One manifestation of such oversight was the creation of a central professionalized police force during the reign of Tukoji Rao Holkar II. In turn, this force was reorganized by the regency council during Tukoji Rao Holkar III's minority (1903–11; r. 1903–26), whilst caukīdār in Indore now came to be paid monthly by the darbār, replacing the former village system in which they were paid ‘in kind by the cultivators’.Footnote 75 Control over justice and protection was thereby ostensibly removed from the paṭel's remit. A fresh Indore police manual was also approved in February 1929. In addition to recommending the initiation of patrolling, which was then taken up the following year, this new manual sought to outline the powers, duties, and procedures of different classes of police officers and constables. It now made it incumbent upon ‘village officers’ to aid the regular police in the performance of their duties. For example, local state actors were responsible for reporting

either to the nearest Magistrate or to the nearest Police Station…:

(1) The permanent or temporary residence of any notorious receiver or vendor of stolen property in any village of which he is the Patel, Patwari [paṭvārī, i.e. village accountant] or Chaukidar.

(2) The resort to any place within, or passage through, such village, of any person whom he knows or reasonably suspects to be a thug, robber, escaped convict or proclaimed offender…

…In addition, both the Patel and Chaukidar should report in similar fashion:-

(a) The advent in their village of any suspicious stranger together with any information which can be obtained from questioning regarding his antecedents and place of residence;

(b) The departure from his home of any convict or non-convict suspect under Police surveillance together with his destination (if known);

(c) The movements of wandering gangs through or in the vicinity of their villageFootnote 76

These duties were part of an attempt to establish cordial and reciprocal relations between village headmen and station house officers, albeit within a hierarchical administrative arrangement in which the former reported to the latter as their superiors. As regular government servants, station house officers and their constables came to function as the most obvious embodiment of central (rather than local) state authority at Indore's borders. Patrolling provided a palpable realization of central sovereignty on the ground, in which most policing responsibilities were now placed in the hands of regular central government employees. Meanwhile, the new duties of village paṭel and caukīdār, whilst designed to ensure that station house officers ‘can look to them confidently for assistance and co-operation…in dealing with crime’, were otherwise an attenuation of their former responsibilities.Footnote 77 The manual, patrolling, and wider police activities were designed to provide the central state with the wherewithal to wrestle responsibility for social control away from local state actors, whilst diminishing their opportunities to act as alternative sources of sovereign authority. By performing its own sovereignty in these spaces, the central state sought to undermine long-standing relationships between watchmen-marauders and village powerbrokers.

III

The police administration reports contain some evidence to suggest that the prescription of duties for village headmen and servants, when coupled with patrolling, did have some palpable effects. During 1936 in the Southern Range, the new inspector-general of police, B. C. Taylor, outlined ‘many cases where suspicious persons…were produced by villagers’. As a consequence, ‘[t]he number of rewards given by the Department to members of the public for good work has increased this year’.Footnote 78 Local officials were also commended for working to reinforce the border and prevent criminal incursions. For example, a paṭel and a caukīdār in the village of Palassia (in Mehidpur parganā of the Mehidpur zilā) both received a remission of one year's land revenue for attacking a group of ḍakait conducting a raid on the village in 1934. They had been ‘encouraged’ to do so by the head constable from the neighbouring Sipra outpost. Significantly, ‘[i]t so happened that the Head Constable…was present in the village that night’ because of the introduction of patrolling activities, which was taken as an illustration of their success.Footnote 79 These developments might be read as evidence of the active collusion of local state actors with representatives of the central state, in which the actions and intentions of the regular police coincided with the former's desire to protect property. In these instances, it seemed that the performance of central state sovereignty was strengthened, the active involvement of local state actors and wider society in ‘criminal’ activities was undermined, and a broader set of societal allegiances to the darbār were generated. When read in tandem with incidents relayed elsewhere in the reports, however, the successes of patrolling and wider policework often appear to be more localized, sporadic, or short-lived. In practice, policework simultaneously often continued to be the prerogative of local powerholders, well into the 1930s.

By either collaborating with or independently repelling ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’, the actions of jāgīrdār, zamīndār, paṭel, and caukīdār repeatedly demonstrated both the fragmented nature of sovereignty at Indore's peripheries and the intricate enmeshment of ḍakait within the ‘everyday’ state. The 1936 report, for example, recounts

the story of the Zemindar of Malegaon [in Rampura parganā] who on hearing that some Banjaras [baṅjāra Footnote 80] of his village had committed some cattle thefts in Kanjarda circle immediately collected retainers and raided their huts and in the face of retaliation retrieved the animals and arrested the Banjaras and then reported to the Police.Footnote 81

In this instance, rather than simply reporting the incident and relying upon the regular police force to bring the perpetrators of this crime to justice, the zamīndār still saw the task of enforcing the peace to fall within the local state's remit. In doing so, he relied upon his ‘retainers’ to undertake such policing responsibilities, in a way that echoed established practice at Indore's peripheries. Likewise, during March 1939 in the border village of Kangetti (situated near the town of Narayangarh in Manasa parganā), the caukīdār attacked ‘a gang of about 30 dacoits, probably Bhils from Pratabgarh [Pratapgarh] State…who were attacking with axes the stout teak doors of a Mahajan's [mahājan, i.e. moneylender, or merchant] house’. The caukīdār was aided by a ‘servant of the Jagirdar’ who ‘also fired from another point’ and they eventually succeeded in driving off the gang.Footnote 82 Given the thinly spread nature of the regular police and their patrols, these incidents suggest that watchmen, themselves drawn from supposedly ‘criminal’ communities, and in the employ of local powerbrokers (i.e. jāgīrdār, zamīndār), often continued to act as ‘the real executive police of the country’ well into the late 1930s.Footnote 83 More generally, the wider village under the authority of the paṭel took it upon themselves to retrieve property when it was stolen, or to repel those they suspected of engaging in ḍakaitī and other ‘criminal’ activities. In three years of successive reports accounting for the successful retrieval of lifted cattle, for example, it was only in one case that villagers drew upon the assistance of the regular state police to do so.Footnote 84 The continuing fragmentation of authority on Indore's peripheries also resulted in continuing opportunities for those practising plunder and protection to act with de facto impunity from prosecution, despite the central state's supposed jurisdictional remit over the region. In fact, Watson's 1930 report lamented ‘the selfishness of the villagers in seeking only the recovery of their own cattle, letting the thieves escape’.Footnote 85

On other occasions, representatives of the central state could behave in a manner that more closely resembled the actions and behaviour of ḍakait and cattle thieves, and frequently ended up as the recipients of comparable treatment from those they targeted in response. The 1938 report contains brief mention of an incident near the village of Machalpur (situated in Jirapur parganā), where ‘the Naib-Amin [deputy revenue collector] of Machalpur and his peons were assaulted by villagers whose cattle they had seized; and a case against 8 persons is pending in court’.Footnote 86 We can speculate that such a seizure was down to the late or non-payment of land revenue to central state authorities, in which the cattle were taken away as surety for the debt. But such behaviour replicated the ways in which local gangs of marauders and thieves ransomed cattle for tribute, thereby uniting the actions of the central state and such gangs in the villagers’ eyes. That the villagers were charged with the offence of ‘rioting and unlawful assembly’ for their response is also significant, given that their decision to violently oppose the seizure simply conformed to existing societal behaviours in the context of cattle-lifting. Such actions were regularly referenced and generally supported by the authors when they applied in the context of cattle-lifting conducted by ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’ elsewhere in the annual reports.

The police administrative reports remain replete with evidence of the existence of ties between ‘criminal gangs’ and ḍakait, on the one hand, and villagers and local state representatives, on the other. In his 1939 report, Watson, who had returned to the role of inspector-general, uncovered a ḍakaitī committed in Sunel parganā by a group of kañjar, a community often referred to as a ‘caste of thieves’.Footnote 87 He reported on how ‘two Thakurs [here referring to individuals performing the function of village paṭel, but who were also from an elite clan of Gahlot rājpūt who had historically claimed jāgīrdārī rights within this parganā Footnote 88] of Gadya [a village in Sunel] had called these Kanjars to commit the dacoity on their neighbour’.Footnote 89 Like the incident near Tarana recounted earlier in this article, such episodes seem to suggest that connections between the plundering activities of supposed ‘criminal tribes’, on the one hand, and the desire to intimidate and undermine rivals on the part of their patrons, on the other, continued to exist, despite the inauguration of patrolling in the late colonial period. That ṭhākur continued to commission these activities points to the continuing disaggregation of power at Indore's peripheries, in which marauders could continue to find gainful employment through alliances with local state representatives. Watchmen could also take the initiative in these activities. The 1935 report refers to a case in Manasa parganā, where several robberies had occurred. After some investigation, the local police inspector first ‘unearthed a small gang headed by a Chaokidar of Manasa’ in 1934, whereupon ‘it was hoped that this would cause that type of offence to cease. However, in the investigation into this case a mixed gang of 10 persons of Dagri and Manasa was unearthed with another Chaokidar of Manasa as chief informer.’Footnote 90 In this example, we can see how ‘criminal gangs’ could operate with the help of those very persons who were also performing the duties of watch and ward. For many caukīdār at Indore's peripheries, raiding some villages whilst protecting others continued to be conceived as two sides of the same coin. In this context, the interventions of the central authorities through patrolling and other policework upset the intricate interplay of local state–society interactions.

The established connections of communities involved in marauding and protection with wider society is also apparent in the administrative reports’ references to ‘the “meharkhai” system of ransoming stolen cattle, through chains of professional receivers’.Footnote 91 Watson's 1939 report notes the way in which such ‘criminal gangs’ of cattle-lifters ‘also maintain regular agents for returning the cattle to their owners on payment of ransom’.Footnote 92 Likewise, his report from 1931 refers to a specific ‘cattle-lifting case’ in Jirapur parganā, ‘in which some of the cattle were received by the complainant by paying ransom to two notorious receivers living across the border in Gwalior State’. Such receivers were often drawn from trading and merchant communities in the region, who benefited financially when it came to selling on the cattle and other goods. During the investigation into this case, ‘the complainant refused to divulge the name of the dacoits’ involved to the police.Footnote 93 In their willingness to pay the ransom and their refusal to reveal the ḍakait's identity, this individual's actions are indicative of the significance of intimidation and extortion as key tools in the ‘protection’ that robber-marauder gangs and their receivers continued to provide to local communities.Footnote 94 That the complainant was willing or felt compelled to pay the ransom also suggests that such activities were not unknown but rather were part of established practice.

As a final example, Watson's 1930 report refers to four cases of harbouring an offender that were brought against borderland villagers residing in the Nimar zilā of the Southern Range. The cases related to recently concluded efforts to capture a gang whose leaders had escaped from Bhikangaon jail in 1928, during which the police lamented both ‘the cowardice of the villagers on certain occasions’ and ‘the protection afforded to [the gang] by the villagers, including Patels and Chowkidars, and even by regular Government servants, while few gave any information against them’.Footnote 95 Between them, the various examples from the police administration reports reveal the entanglement of local state representatives with ‘criminal tribes’ and ḍakait, as well as the embeddedness of plundering and protection activities at Indore's borders in the late colonial period. In Watson's references to ‘cowardice’ and the withholding of information, the 1930 report also implicitly indicates the significance of the power wielded by the Bhikangaon gang. It is ultimately unclear whether the active collusion of villagers and local powerholders in protecting the gang was the result of a favourable agreement initiated between the concerned parties, a consequence of fear and intimidation, or an amalgamation of the two. However, these examples confirm that efforts to expand the central state's sovereign reach did not always materialize in practice at Indore's peripheries in the late colonial period. They also reveal that contestations over the authority of the central state did not emerge only, or even primarily, in opposition to a distant and homogeneous state, but often through negotiated interactions between ḍakait, wider society, and local state representatives. The state was ultimately a disaggregated institutional entity, capable of developing a variety of responses to so-called ‘criminal tribes’.

IV

This article has examined the enduring significance of connections between local powerbrokers and irregular state representatives, on the one hand, and ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’, on the other, at the peripheries of Indore's ostensible authority. In doing so, it has looked to challenge accounts that consider borderlands and other supposedly ‘anomalous zones’ to be either in possession of ‘illusory, insignificant sovereignty neatly “nested” within a colonized terrain, or [to be] stateless’.Footnote 96 Despite recognizing the unevenness of colonial domination, such accounts tend to ultimately reinforce the idea of the modern, territorially bounded state as coming to gradually monopolize twentieth-century forms of sovereignty, often by treating such spaces as diminishing anomalies or ‘parodic theaters’.Footnote 97 Rather than being hollow, trivial, or incongruous, this article has instead captured how sovereign configurations at Indore's peripheries illustrate the enduring fragmentation of sovereignty in late colonial contexts. Whilst the jurisdictional complexity of central India rendered Indore's boundaries particularly permeable, the examples outlined in this article might be read as an acute instance of an enduring and wider pattern across South Asia. During the 1930s, both powerbrokers and ‘criminal tribes’ continued to challenge efforts by the Indore state to centralize authority over policework at its peripheries, whether these related to the initiation of regular border patrolling or the prescription of powers amongst ‘village officers’. Jāgīrdār, ṭhākur, and paṭel continued to independently perform or commission activities amongst their erstwhile ‘retainers’ relating to both plunder and protection.

Equally, those otherwise described as ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’ could instigate both plunder and protection in their role as irregular state representatives, such as when employed as village caukīdār. In the incident reported from Manasa parganā in 1935, for example, one watchman commissioned robberies, and another offered security against that very same threat. As a result, the state continued to act in a disaggregated fashion, in a manner that was bemoaned by Watson and Taylor during their reports. An awareness of such disaggregation on the part of the state, and a recognition of the power of its local representatives, ultimately points to the fragmented nature of late colonial Indore (and India)'s sovereign configurations. It allows us to distinguish between what Hansen describes as ‘promise and reality’, between the ‘symbolic power’ of the central state and the ‘effective de facto governance’ practised amongst irregular state representatives and ḍakait on the ground.Footnote 98 The actions of the gang operating out of Nimar zilā in 1930, for example, reveals the dynamism of dakait and ‘criminal tribes’ within graded and overlapping geographies of power. We can surmise from Watson's report that this gang held at least some degree of authority within this zilā, even as it was represented as falling within Indore's wider sovereign domain.

At the same time, focusing upon the significance of the activities of ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’ within the local political economy goes some way towards nuancing the preoccupations of wider postcolonial and subaltern historiography, which often concentrate on either colonial legal frameworks or the subaltern's ‘autonomous’ resistance to and evasion of the state. In contrast, this article has demonstrated the way ḍakait and ‘criminal tribes’ interacted with local state structures and representatives in Indore's Northern Range. These interactions in turn engendered responses at the ‘everyday’ level that complicated their ethnographic classification as hereditary or intrinsic lawbreakers within wider institutional and legal frameworks. The first section traced these connections back to the late pre-colonial period, noting the shared history of mobility, banditry, and martiality that existed amongst minor potentates and ḍakait. It emphasized how the former could be drawn from sondhiyā, bhīl, and bhilālā communities, who came to use their status as local landholders and rulers at Indore's peripheries to assert their rājpūt identity. Elsewhere, this article concentrated upon references to such marginalized communities within the historical record, noting how this revealed their significance to the centralizing initiatives of the state in late colonial Indore. The emphasis placed upon preventing and punishing ḍakaitī and related ‘criminal’ activities both within the police administrative reports and the Indore police manual indirectly exposed their continuing importance as ‘the real executive police’ within Indore's borderlands well into the twentieth century.Footnote 99 It was the desire to break their connections with local and irregular state actors, such as paṭel, ṭhākur, zamīndār, and jāgīrdār, who played an important patronal role in such policework, that underpinned the initiation of regular patrolling and the prescription of the village officer's duties. The incidents cited in the penultimate section of this article are revealing of the close connections that could exist between the state's ‘everyday’ or ‘profane’ echelons and ḍakait and criminal tribes. By tracing how such connections could emerge both in the commission of ‘crime’ and protection from its effects, this article has also complicated the view that ḍakaitī was conducted only, or perhaps even principally, in opposition to the state.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers of The Historical Journal for their suggestions, which have greatly helped in adding further nuance and depth to the arguments underpinning this article. The author would also like to thank the organizers and participants in the ‘Re-centring the pariah’ workshop at the University of Leeds in June 2017, and the ‘Identity, culture and representation’ research seminar series at the University of Derby in January 2020, where some of the ideas within this article were first formulated and presented.

Funding Statement

The research undertaken for this article was generously supported through a postdoctoral fellowship on the Leverhulme Trust project ‘Rethinking civil society: history, theory, critique’ (RL-2016–044) at the University of York; and through an Economic History Society Carnevali Small Grant (EHS-AppSRG/1509478130613213).

Competing Interests

The author declares none.