Introduction

Humans have a long, complex relationship with wild animals, varying between appreciation, reverence, retaliation, utilization and acceptance (Treves & Naughton-Treves, Reference Treves and Naughton-Treves1999; Ingold, Reference Ingold and Ingold2000; Lescureux & Linnell, Reference Lescureux and Linnell2010; Ghosal & Kjosavik, Reference Ghosal and Kjosavik2015). Studies have tried to understand these relationships by characterizing their nature and by examining the challenges of living with wildlife, especially with species that are responsible for negative impacts such as damage to property, competition for resources, injury or loss of life (Bostedt & Grahn, Reference Bostedt and Grahn2008; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Shrestha, Karki, Pradhan and Liu2012). The management of negative impacts is an important conservation concern as retaliatory killing of wild animals can endanger their populations, and prohibiting retaliation can anger communities sharing space with them (Madden, Reference Madden2004; Woodroffe et al., Reference Woodroffe, Thirgood, Rabinowitz, Woodroffe, Thirgood and Rabinowitz2005). Negative interactions between people and wildlife are often framed as human–wildlife conflict. However, framing human–wildlife relationships predominantly through the lens of conflict can create a strong negative impact on peoples’ psyche and influence perceptions of risk from wild animals (Gore et al., Reference Gore, Kahler and Somers2012).

Peterson et al. (Reference Peterson, Birckhead, Leong, Peterson and Peterson2010) proposed that narratives using the human–wildlife conflict frame tend to represent animals as consciously combating people, dichotomizing humans and nature. The way human–wildlife relationships are framed also has repercussions on how these are interpreted and managed. A biased framing thus provides salience to certain aspects of the relationship, glossing over the nuances that are crucial for wildlife conservation and management (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Birckhead, Leong, Peterson and Peterson2010). Studies have also suggested that human–wildlife conflicts can be split into two components: (1) human–wildlife impacts, and (2) human–human or conservation conflicts that represent the ideological tensions between stakeholders that affect wildlife, for example, preservation of nature vs local livelihoods or human safety (Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Bhatia and Young2015; Young et al., Reference Young, Marzano, White, Mccracken, Redpath and Carss2010).

More recently, some researchers have suggested replacing the term human–wildlife conflict, which usually has a negative connotation, with non-negative ones such as human–wildlife coexistence, or human–wildlife interactions. By facilitating the recognition of the ambivalence in the attitudes and behaviours of people towards wildlife, these debates have infused some diversity into the narratives, and have highlighted the unfavourable consequences of a predominantly negative framing for conservation (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Birckhead, Leong, Peterson and Peterson2010; Bruskotter & Fulton, Reference Bruskotter and Fulton2012; Carter & Linnell, Reference Carter and Linnell2016; Kansky et al., Reference Kansky, Kidd and Knight2016; Mishra et al., Reference Mishra, Redpath, Suryawanshi, McCarthy and Mallon2016). Nevertheless, few studies have explored the spectrum of human responses to wildlife impacts. Frank (Reference Frank2016) suggested that understanding this spectrum can help practitioners assess the relative intensity and strength of negative, positive and ambivalent responses, enabling them to create specific conservation interventions and strategies. An improved conceptual understanding of the spectrum can also enable us to better assess the factors responsible for peoples’ responses.

Previous studies have enumerated several socio-economic, psychological and ecological factors that influence peoples’ attitudes towards, and intention to kill, wildlife (St. John et al., Reference St John, Edwards-Jones and Jones2010; Marchini & Macdonald, Reference Marchini and Macdonald2012; Kansky et al., Reference Kansky, Kidd and Knight2014). For example, socio-demographic factors such as age, gender, wealth, occupation and education are often correlated with attitudes and behaviours towards wildlife (Kellert, Reference Kellert1985; Peyton et al., Reference Peyton, Bull and Holsman2007; Dickman, Reference Dickman2012; Lindsey et al., Reference Lindsey, Havemann, Lines, Palazy, Price and Retief2013). Similarly, descriptive factors such as knowledge of animal behaviour, social norms and taboos about wild animals, and familiarity with the risk posed by wildlife, have also been associated with human responses (McComas, Reference McComas2006; Marchini & Macdonald, Reference Marchini and Macdonald2012). However, few studies have attempted to move from a correlational to a mechanistic understanding of factors.

Here, we examine the bias in framing of human–wildlife relationships in the scientific literature and propose a shift towards recognizing the spectrum of human responses to wildlife impacts. We also review and organize the available information on various factors that influence these responses. Our aims are to (1) understand the framing of literature around human–wildlife interactions, (2) develop a typology to assess peoples’ responses towards wildlife impacts, and (3) strengthen the understanding of factors that influence responses.

Methods

We used the ISI Web of Knowledge database to identify articles on human–wildlife interactions, with the keywords ‘human–wildlife conflict’, OR ‘human–wildlife coexistence’, OR ‘human–wildlife relationship’, OR ‘human–wildlife interaction’, AND ‘factors’, AND ‘drivers’, AND ‘causes’, under ‘Topic’. The search yielded a total of 844 results for 1991–2017 (Supplementary Material 1). Of these, the most recent 250 articles were shortlisted for further analysis (i.e. September 2015–July 2017) based on the rationale that these would better reflect the contemporary understanding of human–wildlife relationships. The articles were classified into their predominant frame using a predeveloped typology (Table 1). Two coders began by analysing a portion of the articles (n = 100) and established 80% inter-coder agreement. Disagreements, if any, were resolved by SB.

Table 1 Typology of frames used to categorize peer-reviewed scientific publications.

Based on the results, we characterized a range of human responses towards wildlife impacts. We built our understanding of responses based on prior models of persuasion (e.g. Value-Attitude-Behaviour, Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behaviour; Fishbein & Ajzen, Reference Fishbein and Ajzen1975; Ajzen, Reference Ajzen, Kuhl and Beckmann1985; Homer & Kahle, Reference Homer and Kahle1988). We inferred that in our context, attitude and behaviour together comprised a response, considering that previous definitions of tolerance and intolerance comprised both these components. For example, Carter & Linnell (Reference Carter and Linnell2016) defined coexistence as a behavioural state where humans and wild animals have learnt to co-adapt with minimal negative impacts on each other. Bruskotter & Fulton (Reference Bruskotter and Fulton2012, p. 99) defined tolerance as a ‘passive restraint or inaction’ on the part of humans up to a threshold of wildlife numbers. Although their concept centred largely around human behaviour, they suggested the approach could also be used to examine human intentions and attitudes.

Treves (Reference Treves2012) pointed out that tolerance and intolerance are states of mind, and therefore emphasis should be placed largely on intentions and attitudes. Similarly, Kansky et al. (Reference Kansky, Kidd and Knight2016, p. 138) defined tolerance as ‘the ability and willingness of an individual to absorb the extra potential or actual costs of living with wildlife’. The term ‘interactions’, on the other hand, has been applied more neutrally to illustrate both positive and negative attitudes and behaviours towards wildlife (Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Bhatia and Young2015). Attitudes represent mental constructs (e.g. thought, feeling) while behaviours represent actions and, together, they have the potential to provide a fuller understanding of human responses to wildlife impacts.

In the next step, we also identified factors influencing human attitudes and behaviours. We made efforts to complement the literature review with an unstructured review to strengthen our understanding of factors. This was done by exploring the key papers and concepts explained in the articles that comprised the review.

Results

Seventy-one per cent of the 250 articles made use of the human–wildlife conflict frame (Table 1). Within this frame, 89% pertained to human–wildlife impacts and 11% described conservation conflicts. Two per cent of the 250 articles discussed coexistence between humans and wildlife, 8% employed a neutral frame, 1% invoked both conflict and coexistence with wildlife, and 18% could not be classified.

Five types of human responses emerged from our review (Fig. 1): (1) manifested intolerance, in which negative attitudes translated into negative behaviours, (2) latent intolerance, in which negative attitudes did not translate into negative behaviours, (3) neutral or ambivalent attitudes, which did not translate into negative or positive behaviours, (4) appreciation, in which positive attitudes did not translate into positive behaviours, and (5) stewardship, in which positive attitudes translated into positive behaviours.

Fig. 1 Visual representation of human response to wildlife impacts. Manifested intolerance comprises responses where both attitude and behaviour are negative towards wildlife. Latent intolerance indicates responses where attitudes are negative, but behaviour is not. Neutral comprises responses where both attitude and behaviour are ambivalent. Appreciation comprises responses where attitudes are positive, but no corresponding positive behaviour can be found. Finally, stewardship indicates responses where both attitude and behaviour are positive.

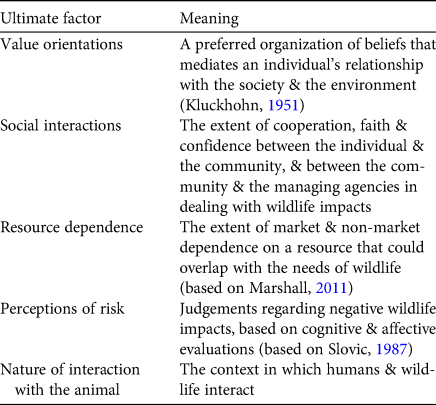

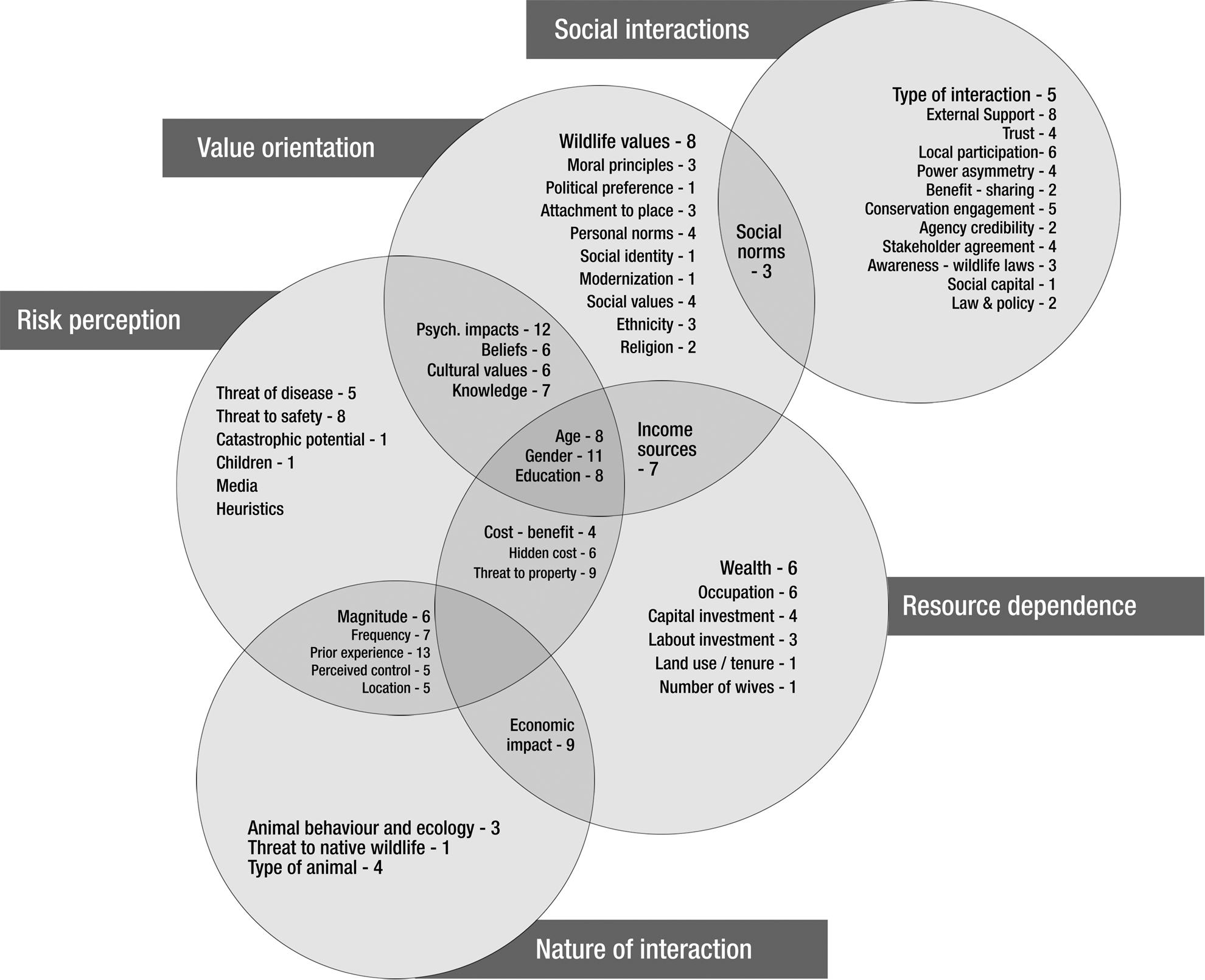

Upon further review, we found that 27% of the 250 articles elaborated on factors that influenced human attitudes or behaviours towards wildlife. The review resulted in a list of 55 factors, spanning socio-cultural, economic, psychological and ecological dimensions. We labelled these as proximate factors. Proximate factors could be viewed as variables with a connection to human responses that do not invoke a causal relationship (Alcock, Reference Alcock1975). The proximate factors were grouped into five ultimate factors that represented the potential underlying mechanisms or causes of human response: value orientations, social interactions, resource dependence, perceptions of risk, and the nature of interaction with the animal (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Table 2 Typology of the ultimate factors underlying human responses to wildlife impacts.

Fig. 2 Factors influencing human responses towards wildlife impacts. Proximate factors (correlates) are listed inside the circles, with the number of times they were mentioned in the articles. The ultimate factors (mechanisms) are in the boxes next to the circles. Except for ‘media’ and ‘heuristics’ (see risk perception circle), the remainder were identified in a systematic literature review. Some of the proximate factors influence more than one ultimate factor.

Discussion

Inordinate focus on human–wildlife conflict

Our findings reiterate that there is a disproportionate emphasis on human–wildlife conflict as a frame and few studies refer to human–human conflict. This may be counterproductive to conservation as it creates a bias in our understanding of peoples’ relationship with wildlife (Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Bhatia and Young2015). It also compounds the real conflict, which usually takes place between communities and the de facto representatives of conservation by assuming wildlife to be deliberately antagonistic towards people (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Birckhead, Leong, Peterson and Peterson2010). It may be more useful to examine people's responses not just in terms of conflict or coexistence but along a spectrum, ranging from negative to positive attitudes and behaviours.

Characterizing human responses to wildlife impacts

We identified a gradient of attitudinal and behavioural intensity in articles that described human–wildlife relationships, ranging from shades of positive to shades of negative. Most incidents of violent confrontation between people and wildlife, such as retaliatory killing, could be considered examples of manifested intolerance (e.g. Simms et al., Reference Simms, Salahudin, Ali, Ali and Wood2011; Swanepoel et al., Reference Swanepoel, Somers and Dalerum2015; Hazzah et al., Reference Hazzah, Bath, Dolrenry, Dickman and Frank2017). However, there could be instances where behaviours are negative even though attitudes are positive, such as in situations where an individual is forced to act against his/her preference or beliefs because of the prevailing social circumstances. Similarly, individuals may succumb to social pressure to relocate a damage-causing animal from their locality despite not feeling strongly about it (Ghosal & Kjosavik, Reference Ghosal and Kjosavik2015). Such instances could be classified as manifested intolerance, considering that the ultimate outcome is a negative action towards wildlife.

Latent intolerance can be identified in situations where people's attitudes are negative, but no corresponding negative behaviour can be found (Manfredo & Dayer, Reference Manfredo and Dayer2004). The intolerance could be a result of unfavourable conditions that have inhibited people from acting negatively, such as perceptions of human incapability or the lack of resources to engage in an intolerant response, or the legal/social implications of engaging in a negative response (e.g. Bhatia et al., Reference Bhatia, Redpath, Suryawanshi and Charudutt2016). A Buddhist, for example, may feel inclined towards injuring a damage-causing carnivore but may not execute this desire because of legal costs or religious philosophy (Bhatia et al., Reference Bhatia, Redpath, Suryawanshi and Charudutt2016). This also implies that when the unfavourable conditions are removed, people may, not necessarily, switch from latent to forms of manifested intolerance.

Neutral or ambivalent responses are those where individuals tend not to act either way or are undecided about how they feel towards the wild animal and its impact (Kansky et al., Reference Kansky, Kidd and Knight2014). Appreciation indicates that the individual or community values the existence of the wild animal and chooses to accept the negative impacts even though they may not positively engage with conservation (Dorresteijn et al., Reference Dorresteijn, Milcu, Leventon, Hanspach and Fischer2016). Finally, stewardship comprises situations where the individual or community protects the wild animal even in the face of wildlife damage, owing, perhaps, to the conservation or cultural significance of the species (Bruskotter & Fulton, Reference Bruskotter and Fulton2012; Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Yin, Zhaxi, Jiagong and Schaller2015).

What affects human responses to wildlife impact?

Similar to Anand & Radhakrishna (Reference Anand and Radhakrishna2017), we found that a modest subset of studies on human–wildlife interactions described factors. The 55 factors that we identified were considered proximate factors or correlates because they were pattern-oriented rather than cause-oriented. For example, gender, a proximate factor, may influence human responses to wildlife, but by itself it does not help us understand why a particular gender should have a negative or positive response towards wild animals. The differential engagement of genders with conservation organizations or their varied perceptions of risk could instead be the drivers of their response (Gillingham & Lee, Reference Gillingham and Lee1999; Prokop & Fančovičová, Reference Prokop and Fančovičová2010). The five ultimate factors identified in the study were value orientation, social interactions, resource dependence, perceptions of risk and nature of interaction with the animal.

Value orientation can be understood as a preferred organization of beliefs that mediates an individual's relationship with society and the environment (Kluckhohn, Reference Kluckhohn, Parsons and Shils1951). Values enable an individual to choose a conduct that is personally or socially preferable (Rohan, Reference Rohan2000; Vauclair, Reference Vauclair2009). Value orientations are affected by ethnicity, religious and cultural beliefs, personal and social norms about the animal in question, a sense of social identity (for example, whether one is a hunter or a farmer), and can be influenced by one's environment (e.g. rural vs urban; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Zinn, Wang, Burns and Robinson2006; Manfredo, Reference Manfredo2008; Marchini & Macdonald, Reference Marchini and Macdonald2012; Inskip et al., Reference Inskip, Carter, Riley, Roberts and MacMillan2016; Koziarski et al., Reference Koziarski, Kissui and Kiffner2016; Pooley, Reference Pooley2016; Amit & Jacobson, Reference Amit and Jacobson2017).

Studies have examined how value orientations influence attitudes and behaviour towards nature and wildlife (Rokeach, Reference Rokeach1973; Homer & Kahle, Reference Homer and Kahle1988; Ajzen, Reference Ajzen1991; Stern & Dietz, Reference Stern and Dietz1994; Natori & Chenoweth, Reference Natori and Chenoweth2008; Dietsch et al., Reference Dietsch, Teel and Manfredo2016). Hazzah et al. (Reference Hazzah, Mulder and Frank2009) pointed out that people's attitude is not defined purely by the economic impacts caused by wildlife but is also affected by the cultural significance of the loss. Cattle hold greater cultural value for the Maasai compared to small livestock (sheep and goats) and therefore lion depredation on cattle provokes greater resentment towards the carnivore (Hazzah et al., Reference Hazzah, Mulder and Frank2009).

Social interactions refer to the extent of cooperation, faith and confidence between the individual and the community, and between the community and conservation agencies, when dealing with wildlife impacts. These could have an overarching influence on the way people perceive wildlife in their landscape, who they attribute the ownership of wildlife to, and whether they consider themselves to be marginalized or empowered (Mutanga et al., Reference Mutanga, Muboko and Gandiwa2017; Pooley et al., Reference Pooley, Barua, Beinart, Dickman, Holmes and Lorimer2017).

The extent of cooperation or conflict over shared resources, a strong social network, and the presence of an environment in which economic and social burdens are shared can provide opportunities for people to respond collectively to wildlife impacts (Romañach et al., Reference Romañach, Lindsey and Woodroffe2007). Similarly, the nature and the extent of interaction that an individual has with conservation agencies and the extent of consonance between the expectations of the stakeholders involved will determine the level of faith that the community places in the agencies (Zajac et al., Reference Zajac, Bruskotter, Wilson and Prange2012; Dorresteijn et al., Reference Dorresteijn, Milcu, Leventon, Hanspach and Fischer2016; Nyhus, Reference Nyhus2016; Amit & Jacobson, Reference Amit and Jacobson2017; Mishra et al., Reference Mishra, Young, Fiechter, Rutherford and Redpath2017; Pooley et al., Reference Pooley, Barua, Beinart, Dickman, Holmes and Lorimer2017). These interactions are played out against a backdrop of wildlife laws and legal enforcement, political power and media involvement (Bhatia et al., Reference Bhatia, Athreya, Grenyer and Macdonald2013; Rust et al., Reference Rust, Tzanopoulos, Humle and MacMillan2016).

Resource dependence has a direct bearing on the economic and psychological costs of living with wildlife. If a significant proportion of time, labour and money has been invested in a resource that is perceived to be in competition with the needs of wildlife, then an individual is likely to have a more negative response towards wildlife (Gadd, Reference Gadd2005; Karlsson & Sjöstrom, Reference Karlsson and Sjöström2011; Humle & Hill, Reference Humle, Hill, Serge and Marshall2016). Furthermore, occupation and wealth are important considerations, and diversification of income sources provides a buffer against loss (Dickman, Reference Dickman2010; Pont et al., Reference Pont, Marchini, Engel, Machado, Ott and Crespo2016). Marshall (Reference Marshall2011) further suggested that resource dependence has social, economic and environmental dimensions.

It is also important to understand people's perception of risk from wildlife because this can influence their willingness to coexist with it (Webber & Hill, Reference Webber and Hill2014). Risk perceptions are the judgements people make when examining and evaluating personal and social threats (Slovic, Reference Slovic1987). Individuals may perceive certain wild animals to be a threat to property or life, or simply be afraid to encounter them (Dorresteijn et al., Reference Dorresteijn, Milcu, Leventon, Hanspach and Fischer2016; Koziarski et al., Reference Koziarski, Kissui and Kiffner2016; Nyhus, Reference Nyhus2016). On the other hand, they may feel awe and admiration for the animal despite the costs associated with the interaction (Goldman et al., Reference Goldman, Roque, Pinho and Perry2010). The outcome is often a trade-off between people's perceptions of the negative impacts of risk and the perceived/expected benefits from it (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Jhala, Chauhan and Dave2013; Kansky et al., Reference Kansky, Kidd and Knight2016). Risk perception has two important dimensions, the cognitive and the affective. The cognitive dimension involves people's assessment of the probability of occurrence of an event and the affective dimension involves the instinctive and spontaneous response of people when they experience it (Riley & Decker, Reference Riley and Decker2000; Gore et al., Reference Gore, Wilson, Siemer, Hudenko, Clarke and Hart2009). Wildlife damage can also be evaluated in terms of its catastrophic potential, defined as a rare devastating event that can strongly influence peoples’ responses (McComas, Reference McComas2006; Dickman, Reference Dickman2010).

Gore et al. (Reference Gore, Knuth, Curtis and Shanahan2007) suggested two predominant types of influences on people's perceptions of risk from wildlife: personal/individual capacity to control, and agency capacity. The former includes factors such as personal volition, perceived probability of exposure to risk, frequency and intensity of exposure, predictability and ability to control the risk, knowledge about the risk, and affect (Dorresteijn et al., Reference Dorresteijn, Milcu, Leventon, Hanspach and Fischer2016; Pont et al., Reference Pont, Marchini, Engel, Machado, Ott and Crespo2016). Agency capacity includes external variables such as trust in the intentions and capabilities of the agency/individuals responsible for mitigation (McComas, Reference McComas2006; Gore et al., Reference Gore, Knuth, Curtis and Shanahan2007; Earle, Reference Earle2010).

The nature of interaction with the animal is the setting in which people encounter wildlife. Some specific factors that define people's interactions include the action, target, context and time (Fishbein & Ajzen, Reference Fishbein and Ajzen1975). For instance, what was the impact (action), who caused it (target), where and when did the incident occur (context and time)? Thus, the location of the species, the type of animal, the magnitude of impact, and animal behaviour are important influences (Dorresteijn et al., Reference Dorresteijn, Milcu, Leventon, Hanspach and Fischer2016; Nyhus, Reference Nyhus2016). Every interaction need not be negative as there could be situations in which the animal has not caused harm (e.g. it is merely encountered in the landscape) or there could also be instances in which the animal has had a positive impact on the individual (e.g. nature lovers who search for encounters with animals in the wild). The nature of interaction can also affect knowledge and beliefs about the species and thereby influence other ultimate factors such as perceptions of risk, and even value orientation.

Proximate factors such as age, gender, education and the hidden costs of living with damage-causing species work through multiple pathways (Fig. 2). For example, people's perception of risk, their resource dependence and their value orientations may differ depending on their age, gender and level of education (Koziarski et al., Reference Koziarski, Kissui and Kiffner2016; Manfredo et al., Reference Manfredo, Teel and Dietsch2016). Similarly, the hidden costs of human–wildlife interactions will affect perceptions of risk and resource dependence of individuals (Humle & Hill, Reference Humle, Hill, Serge and Marshall2016).

The five ultimate factors may also interact with and iteratively influence each other. For example, value orientations may influence perceptions of risk and the type of social interactions within a community and between a conservation agency and the community. Similarly, the nature of interaction with the animal may influence resource dependence as well as perceptions of risk. Resource dependence may have a bearing on risk perceptions and vice-versa. Social interactions may influence perceptions of risk, and vice-versa, at the level of the individual and community.

Conclusion

Human–wildlife conflict, although a predominant narrative, is not the only form of interaction between people and wild animals. Moving beyond conflict to alternative conceptualizations can affect how we tackle the intellectual and practical challenges of living with wildlife. In this regard, intention and choice can be viewed as playing a key role in influencing people's responses towards wildlife. Based on our findings, we suggest that it may be useful to define tolerance as ‘the state of neutral or positive attitude manifested as a neutral to positive behaviour towards wildlife despite their real or potential negative impacts’. Manifested and latent intolerance thus comprise intolerant responses arising from negative attitude or behaviour.

Finally, a move towards exploring the causal linkages or mechanisms influencing human responses could enable practitioners to develop more predictive and proactive models of conservation and management. Our study also aligns with Bruskotter et al. (Reference Bruskotter, Vucetich, Manfredo, Karns, Wolf and Ard2017) who proposed that values and risk perceptions were two key mechanisms driving tolerance towards carnivores. Human responses to wildlife differ across individuals and communities, across species, across cultures and over time. Greater coverage of geographies and cultural contexts would help improve our understanding of this important subject.

Globally, interactions between humans and wildlife are expected to increase as suitable wildlife habitats shrink, climate changes and some wild populations recover (Nyhus, Reference Nyhus2016). A better knowledge of capacity to tolerate wildlife will, therefore, help in facilitating coexistence between humans and wild animals with minimal repercussions to each other.

Acknowledgements

We thank Juliette Young, Yash Veer Bhatnagar, Suri Venkatachalam, Munib Khanyari, and Phalguni Ranjan for their input and support.

Author contributions

Study design, fieldwork and data analysis: SB; writing: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research did not involve any animal or human subjects, and otherwise abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.