INTRODUCTION

The emergence of Germany as a major economic and military power transformed world politics. German unification in 1871 and the country’s subsequent industrialization not only altered the balance of power in Europe but also reordered global patterns of comparative advantage. This article studies the effects of rising German imports on British politics. We use this case to examine how voters, parties, and governments respond to changes in the global economic order. Over the three decades before the First World War, Britain’s once-dominant manufacturing industries lost out to rapidly growing German competitors. Understanding the consequences of these developments for Britain’s domestic politics is crucial given the concern that the rise of China since the 1980s has led to polarization and extremism in the United States and Europe (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Dorn, Hanson and Majlesi2020; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018c).

We argue that Germany’s economic development and integration into the world economy increased support for the neo-welfare state, a bundle of modern spending and regulatory programs that replaced traditional forms of poverty relief and protected citizens from an array of negative market outcomes. In 1906, British voters elected a Liberal government that introduced sweeping reforms, including the introduction of public pensions and health insurance, which would form the basis of the postwar welfare state. We find that localized German import penetration increased support for the Liberal and Labour parties when they advocated welfare reforms. Import penetration also led Liberal candidates to draw more attention to these reforms when campaigning. We argue that German imports increased support for the early welfare state through two channels. First, labor market disruption from German imports led voters to demand government programs that would compensate them for the economic harms and risk wrought by globalization. Second, import competition, which pushed previously productive workers out of employment, changed perceptions of the moral status of the poor.

In arguing that exposure to the world economy contributed to the establishment of the early welfare state in Britain, this study relates to seminal contributions by Cameron (Reference Cameron1978) and Rodrik (Reference Rodrik1998). Cameron emphasized how specialization in trade led to industrial concentration, which in turn strengthened the role of unions in policy making. Rodrik argued that trade increased economic volatility and that state spending could help limit the negative consequences of these disruptions. This compensation theory became central to understanding variation in the size of government and the growth of the postwar welfare state (see also Adserà and Boix Reference Adserà and Boix2002; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Mares Reference Mares2005) and foundational to Ruggie’s (Reference Ruggie1982) argument that open markets were politically possible because states limited their distributional consequences in part through the welfare state and other forms of government spending (Hays Reference Hays2009; Hays, Ehrlich, and Peinhardt Reference Hays, Ehrlich and Peinhardt2005; Kurtz and Brooks Reference Kurtz and Brooks2008; Mansfield and Rudra Reference Mansfield and Rudra2021). Scholars have pointed out that openness might also create a race to the bottom that constrains the ability of states to meet the new demands of their citizens (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Rodrik Reference Rodrik1997; Rudra Reference Rudra2002). Nonetheless, this critique does not conflict with the idea that openness increases the demand for government.

This study extends compensation theory to the origins of the welfare state. Leading explanations of welfare state formation emphasize franchise extension (Lindert Reference Lindert2004), unions and class politics (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Korpi Reference Korpi2006), and the role of employers (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Swensen Reference Swensen2002). Scholars emphasize the importance of industrialization, both in creating the socialists, industrialists, and unionists who pushed for the welfare state, and in generating new social risks and thus demands for state support (Moses Reference Moses2018). We do not argue that these factors were not important; the emergence of the welfare state was not monocausal. However, our evidence of trade leading to support for the early welfare state cannot be attributed to these mechanisms but is complementary to the existing literature. Exposure to the global economy, through the mechanisms we outline, led both ordinary voters and elites to support welfare programs. Its effects on the rise of the early welfare state are thus consistent with explanations of welfare state formation that emphasize the importance of different groups of actors. The compensation mechanism is also relevant to understanding support for the particular type of centralized welfare state created by the Liberals in place of Britain’s existing decentralized system of poverty relief (López-Santana Reference López-Santana2015).Footnote 1 A centralized system could pool risk across regions, making it more desirable in the presence of regionally concentrated import shocks.

We estimate the effects of the German trade shock on economic and political outcomes in England and Wales from 1880 to 1910, using parliamentary constituencies as the unit of analysis. We measure the change in import penetration at the local level using the empirical strategy developed by Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2013). We construct a shift-share change in import penetration per worker measure of local exposure to German imports based on 94 industries. We do so using national-level trade data by product and local measures of occupations allocated to each constituency. We examine the effects of this variable on labor-market disruption, using census microdata at the constituency level, and on the vote shares of different parties. To further understand the political response to the German trade shock, we use data from the British Newspaper Archive on the text of 480 newspapers, which we geocode and link to parliamentary constituencies. We use this source to measure local concerns about trade and immigration as well as local beliefs about the deservingness of the poor. Finally, we also measure local demand for policy—especially social reform—from references in candidate campaign manifestos collected by Laura Bronner and Daniel Ziblatt.

Our estimation strategy examines the effects of within-constituency changes in imports per worker on our measures of labor market outcomes, voting for particular parties, and the prevalence of different issues in newspapers and campaign manifestos. We estimate first-difference and fixed effects regressions and control for nonlinear trends related to preshock manufacturing activity. Estimates from these regressions can be interpreted causally within the difference-in-differences framework. The main identifying assumption is that apart from the effects of changes in imports, constituencies with greater employment in affected industries would have followed trajectories similar to those of constituencies with less employment in those industries.

We present evidence that rising imports caused worse labor market outcomes, as measured by vagrancy and the share of workers in unskilled jobs during the period 1880–1910. We also find that rising imports led to a decrease in support for the Conservative Party in national elections after 1900, by which time the Liberal Party had signaled its support for the neo-welfare state. The main findings are that the German trade shock had a negative effect on local labor markets in Britain and that the political response was a shift away from the Conservative Party toward left-of-center parties, mostly toward the Liberals. This result is inconsistent with voters demanding protectionism in response to the trade shock. After 1900, the Liberals still unambiguously favored free trade, whereas the Conservative Party was divided, with some party leaders advocating protective tariffs.

Given that the timing of when the trade shock favored the Liberals coincided with the Liberals’ embrace of social reform, this result is broadly consistent with compensation theory. We further present evidence that trade shocks are correlated with increased references to social reform in Liberal candidates’ campaign manifestos, which bolsters the interpretation that greater support for Liberal candidates reflected demand for the emerging neo-welfare state.

We suggest that there were two mechanisms at work in trade’s effect on the demand for more government. First, as argued by Rodrik (Reference Rodrik1998), the German trade shock increased assessments of how volatile employment is in a market economy and as a result increased the demand for government policies that would smooth these cycles. We show that rising imports increased local newspaper references to trade and imports as well as Liberal candidate references to social reform. Second, we find evidence suggesting that the trade shock changed elite beliefs about the deservingness of the poor, transforming “vagrants” into the “unemployed.” A range of social scientific work on support for the welfare state emphasizes that the more individuals believe that bad economic outcomes are due to a lack of effort or some other defect on the part of the worker, the less favorably they view the welfare state (see among others Alesina and Angeletos Reference Alesina and Angeletos2005; Fong Reference Fong2001; Piketty Reference Piketty1995). For much of the history of capitalism up to the twentieth century, moral failing was a dominant account of poverty. We show that trade shocks are positively associated with the use of neutral terms like “unemployment” relative to morally charged terms like “pauperism” and “vagrancy.” Our findings link to a growing historical literature on changing attitudes and welfare state development. Moses (Reference Moses2018) discusses how the realization that workplace accidents were an unavoidable feature of industrial capitalism, and not simply the result of negligence, contributed to support for workplace compensation and the early emergence of the welfare state. This study provides quantitative evidence that trade contributed to the rise of the welfare state in part through a similar process.

This article makes three main contributions. First, it provides evidence that globalization contributed to demands for welfare state development at the origin of the welfare state. This finding is in contrast with other theories of the origin of the welfare state, which emphasize a different set of factors. Our research design allows us to rule out the possibility that franchise extension, or lobbying for the welfare state by unions or employers—except as influenced by German trade—explains our results. In relation to these theories, studying the effects of import competition provides a new set of reasons why groups of actors came to support the early welfare state. This finding is also in contrast to previous work that links globalization to the postwar expansion of the welfare state. The article builds on Mares’s (Reference Mares2005) cross-country study of unemployment insurance during the interwar period and provides an out-of-sample test of compensation theory with a research design that supports a causal interpretation. This contribution is complementary to Barnes’s (Reference Barnes2020) recent work arguing that the shared interests in free trade of elites and labor led to more progressive tax policies prior to World War I in Europe generally and in the United Kingdom specifically.Footnote 2 Barnes’s argument is not about compensation in that she emphasizes shared interests in free trade driving some elites to compromise on progressive taxation that workers were already demanding. Nonetheless, both her study and ours argue that the international origins of the neo-welfare state have been neglected in prior research.

Second, the article introduces a new mechanism for the compensation effect of globalization: negative trade-induced labor market outcomes are less likely to be attributed to the failings of the unemployed, and government spending on the deserving poor is viewed more favorably by voters. This finding connects compensation theory to a large empirical literature on public support for redistributive policies.

Third, this article applies methods used to study the China trade shock to Germany’s integration into the world economy. China’s industrialization has accelerated the decline of manufacturing employment in many industrial economies. Although the political response to these developments has varied across countries, the majority of studies find that the China shock increased both skepticism about the role of the government in the economy and support for protectionist trade and restrictionist immigration policies, and precipitated a turn toward authoritarian and nationalist values (Baccini and Weymouth Reference Baccini and Weymouth2021; Ballard-Rosa et al. Reference Ballard-Rosa, Malik, Rickard and Scheve2021; Broz, Frieden, and Weymouth Reference Broz, Frieden and Weymouth2021; Che et al. Reference Che, Lu, Pierce, Schott and Tao2016; Colantone and Stani Reference Colantone and Stanig2018a; Reference Colantone and Stanig2018b; Reference Colantone and Stanig2018c; De Vries, Hobolt, and Walter Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Hays, Lim, and Spoon Reference Hays, Lim and Spoon2019; Margalit Reference Margalit2019; Milner Reference Milner2021). This study expands research on the political consequences of import competition beyond the China example. Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain is perhaps the first case of serious import competition in an industrialized democracy that had previously been the global industrial leader. This case is thus important for contextualizing the effects of the China shock, especially in the United States. This study finds that trade led to demand for the early welfare state. These findings warrant further research on why globalization leads to different political reactions in different contexts. Our conclusion highlights several features of early twentieth-century Britain that distinguish it from many of the countries most affected by China’s integration into the world economy and may account for the turn toward compensation and more government rather than protectionism and right-wing populism.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows: we first describe the economic and political environment in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain that witnessed dramatic increases in German imports, significant economic change, and the emergence of new cleavages in domestic politics over the regulation of capitalism and the formation of a neo-welfare state. We then describe the new constituency-level historical data that we have constructed to study the effects of rising German imports on labor market outcomes, election results, and local economic and political concerns expressed in newspapers and campaign manifestos. Next, we outline our empirical strategy and present our main results on the effects of the German trade shock on labor market outcomes and election results. We then present our analysis that explores the mechanisms underlying the relationship between rising imports and vote choice. We conclude by discussing the implications of the findings for the literatures on globalization, the size of government, and redistributive politics.

GERMAN TRADE AND BRITISH POLITICAL ECONOMY IN THE LATE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES

Before analyzing the within-constituency effects of German imports on economic change and demand for the neo-welfare state, it is natural to ask whether at the national level rising imports from Germany were accompanied by the expansion of social spending.

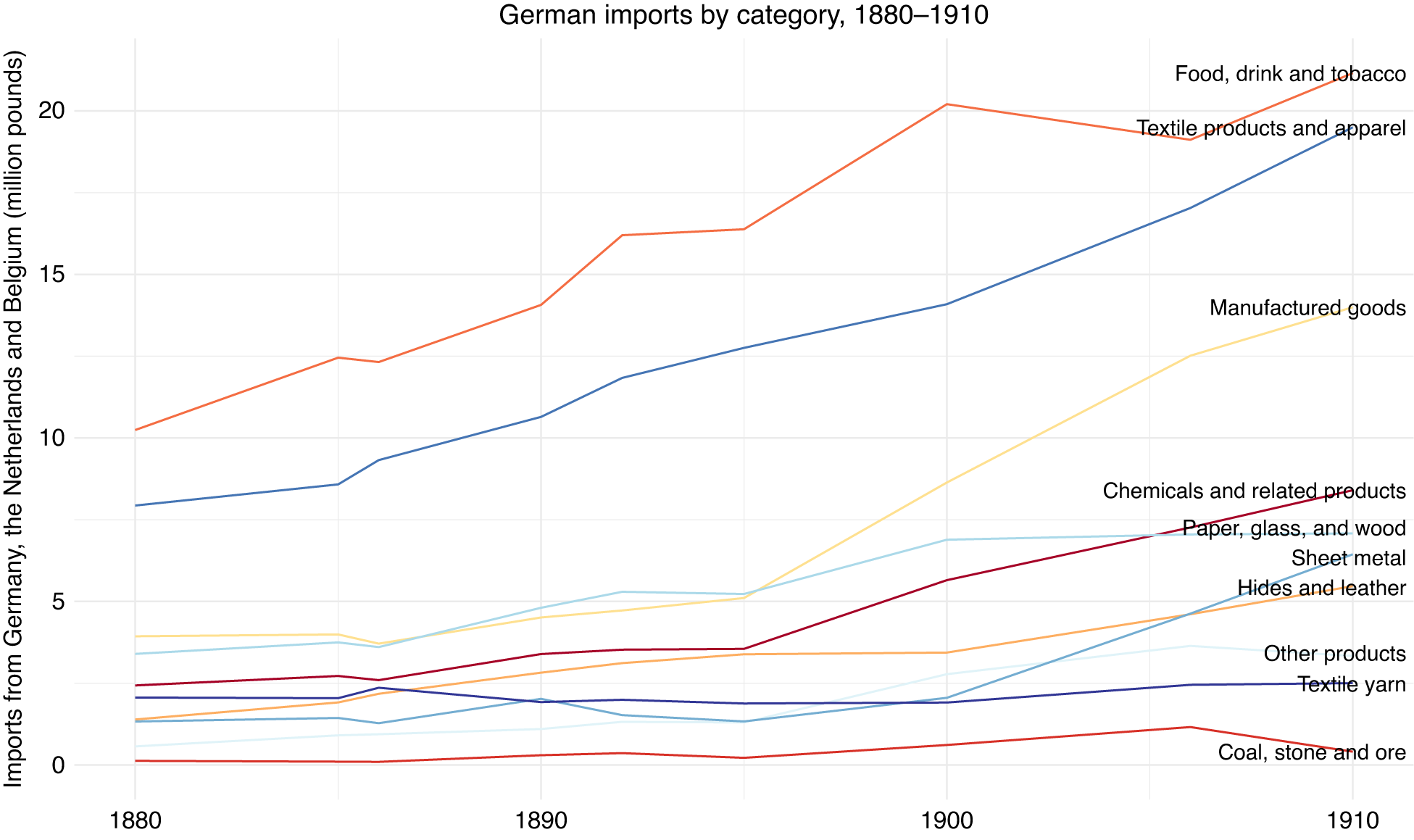

Figure 1 reports UK imports from Germany from 1880 to 1910. Our data come from the Annual Statement of the Trade of the United Kingdom. At this time, Germany shipped its products directly from German ports but also through Belgium and the Netherlands. Our data source assigns the country that the good is shipped from as the origin of the import whether or not the good was produced there. Consequently, we count imports from Belgium and the Netherlands as German imports as well as shipments directly from Germany. The figure indicates an almost doubling of German imports from 1880 to 1910. During this period, Germany was the UK’s second largest source of imports, after the US, from which it mainly imported raw materials like cotton (Figure A-2). Between 1880 and 1910, the UK’s trade to GDP ratio averaged 54% (Thomas and Dimsdale Reference Thomas and Dimsdale2017).

Figure 1. UK imports from Germany, 1880–1910

During most of this period, there were only modest changes in German and UK trade policies. Germany generally had high tariffs, whereas the UK maintained free trade. The increase in German imports reflected the country’s rapid industrialization (especially after 1890), comparative advantage, and declining transportation costs. Figure 2 breaks down the increases in imports by product categories.

Figure 2. UK imports from Germany in Decade and Election Years, by Category

Figures 1 and 2 suggest that the magnitude of the increase in German exports to the UK was economically significant. Below we provide a new analysis assessing the economic effects of the shock. But for context, it is important to note that British observers at the time thought German imports were important. They were one of a number of indicators that suggested relative economic decline in the Victorian era, and explaining this decline was an obsession of the businessmen and economists of the period (McCloskey and Sandberg Reference McCloskey and Sandberg1971). An 1896 book drawing attention to the prevalence of imports “Made in Germany,” which warned, “The industrial supremacy of Great Britain … is fast turning into a myth,” ran through six editions (Williams Reference Williams1896, 1). In a 1903 speech, Joseph Chamberlain, a leading advocate of protectionism, warned that in the face of foreign competition “Sugar has gone; silk has gone; iron is threatened; wool is threatened; cotton will go… . Do you think, if you belong at the present time to a prosperous industry, that your prosperity will be allowed to continue?” (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain1914, 177).

Were these rising imports accompanied by greater social spending? Figure 3 reports data from Boyer (Reference Boyer2019) combining spending on poor relief and pensions in the UK. It records a steady increase in social spending starting in the 1890s through the mid-1900s followed by a dramatic increase for the remainder of that decade and leading up to World War I. This increase reflected the Liberal Party running and winning in 1906 on a platform committed to social reform and free trade, overturning a Conservative majority elected in 1900 on a platform of imperialism. The Liberal Party then won two elections in 1910 on an explicit platform of redistribution. The data capture only a fraction of the legislation enacted during this period that could be viewed as, in part, serving a compensatory purpose. The Liberals passed the Workmen’s Compensation Act of 1906, the Old-Age Pensions Act of 1908, the Labour Exchanges Act of 1909, and the National Insurance Act of 1911, as well as other legislation that would address directly and indirectly some of the costs associated with increased import competition. It is, of course, impossible to tell from these aggregated data whether greater social spending was at least partially a response to increased trade. The remainder of the article seeks to determine the nature of this relationship.

DATA

Trade and Labor Market Outcome Data

We estimate the effects of the German trade shock on economic and political outcomes in England and Wales, using parliamentary constituencies as the unit of analysis.Footnote 3 We measure the change in import penetration at the local level using the empirical strategy developed by Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2013)—that is, we compute

$$ \Delta {\mathrm{IPW}}_{it}=\sum \limits_j^n\frac{L_{ij}}{L_i}\frac{\Delta {M}_{jt}}{L_j}, $$

$$ \Delta {\mathrm{IPW}}_{it}=\sum \limits_j^n\frac{L_{ij}}{L_i}\frac{\Delta {M}_{jt}}{L_j}, $$

where

![]() $ {L}_{ij}/{L}_i $

is the share of employment in industry j in constituency i in the base year, 1881, and

$ {L}_{ij}/{L}_i $

is the share of employment in industry j in constituency i in the base year, 1881, and

![]() $ \Delta {M}_{jt}/{L}_j $

is the change in imports for industry j in year t, relative to total employment in that industry in 1881. We index the change in imports relative to different years in different specifications: In long first-difference specifications,

$ \Delta {M}_{jt}/{L}_j $

is the change in imports for industry j in year t, relative to total employment in that industry in 1881. We index the change in imports relative to different years in different specifications: In long first-difference specifications,

![]() $ \Delta {M}_{jt} $

is the change in imports relative to the previous period. In other models that use constituency fixed effects, we index relative to the first year used in the analysis. We Winsorize the industry-level change in imports per worker at plus or minus 500 pounds per worker, equivalent to the 97th percentile.

$ \Delta {M}_{jt} $

is the change in imports relative to the previous period. In other models that use constituency fixed effects, we index relative to the first year used in the analysis. We Winsorize the industry-level change in imports per worker at plus or minus 500 pounds per worker, equivalent to the 97th percentile.

We use the full-count 1881 census of England and Wales (Minnesota Population Center 2020; Schürer and Higgs Reference Schürer and Higgs2014) to compute the sizes and distributions of different industries and combine this with product-level data on imports from the Annual Statement of the Trade of the United Kingdom. Occupational categories in the nineteenth-century census contain a high degree of specificity about industries, distinguishing, for instance, “Ironfounders” from “Iron clasp, buckle, and hinge makers” and “Brass founders.” We group occupational categories and product-level import data into 94 industries, with the goal of identifying the finest level of variation present in both the trade statistics over the total period and the occupational categories.

British parliamentary constituencies do not coincide with administrative units, which has prevented scholars from computing economic variables at the constituency level. We resolve this problem by allocating parishes—the finest level of aggregation in the census—to constituencies. For the 1881 census, we use crosswalk files constructed by Jusko (Reference Jusko2017), who manually assigned parishes to constituencies based on contemporary reports by the boundary commission and maps. For other years, we first link the census data to a consistent GIS based on parishes in the 1851 census (Satchell et al. Reference Satchell, Kitson, Newton, Shaw-Taylor and Wrigley2016), using crosswalk files constructed by Day (Reference Day2016). We then assign parishes to constituencies using shapefiles from the Great Britain Historical GIS Project (2004). Where parishes fall into multiple constituencies, we weight the fraction assigned to each constituency by the fraction of the parish falling into that constituency multiplied by the relative population density of the constituency.

We compute two measures of the economic effects of the trade shock—the percentage of vagrants and the percentage employed in unskilled occupations—at the constituency level, using full-count data from the 1881, 1891, 1901, and 1911 censuses. We classify vagrants as those whose occupation was listed as “No specified occupation—vagrants, unemployed.” This measure plausibly captures labor-market disruption in the form of increased unemployment and the unemployed migrating in search of work. Using the limited time-series data collected by Poor Law administrators, Boyer (Reference Boyer2019, 111–2) finds that rates of vagrancy and unemployment closely tracked one another.

We classify unskilled occupations using the Seventy-Fourth Annual Report of the Registrar General, 1913, which allocated census occupations to eight social classes. The percentage of people in occupations in class 5 (“occupations including mainly unskilled men” [xli]) has been used in the historical geography literature to measure poverty at the local level (Gregory, Dorling, and Southall Reference Gregory, Dorling and Southall2001). These occupations are primarily various forms of unskilled laborers such as “shipyard labourers,” “navvies,” “bill posters,” and workers in “scavenging and disposal of refuse.” The fraction employed in unskilled jobs would plausibly increase in response to import competition if there was a reduction in higher-skilled employment, leading unemployed skilled workers to take on casual labor.

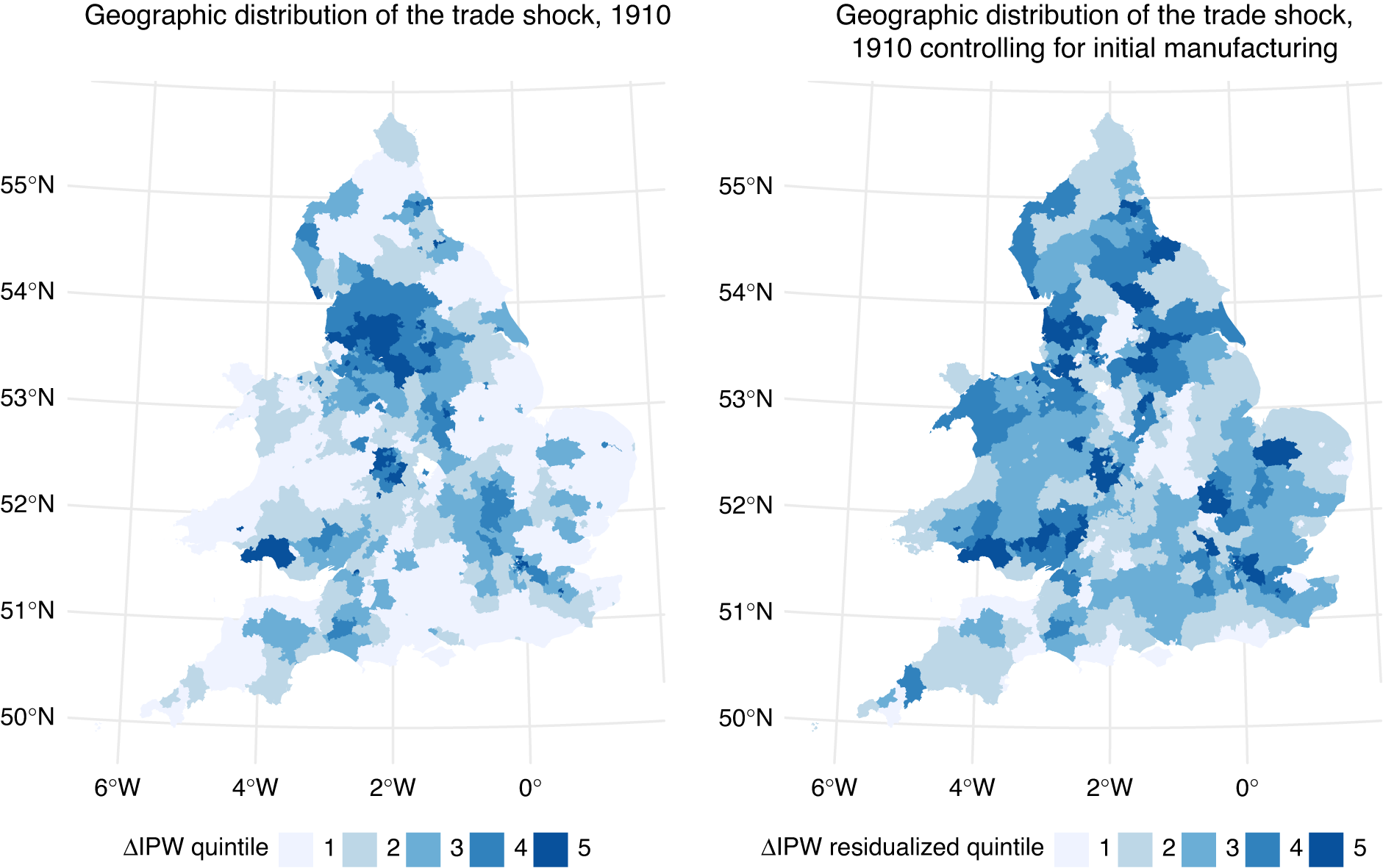

In many of our regression specifications, we control for 1881 manufacturing employment interacted with year dummies in order to separate the effects of the German trade shock from time-variant effects related to manufacturing. We compute this measure using the fraction of people employed in secondary occupations—those in which raw materials were converted into finished products—according to the classification system developed by Wrigley (Reference Wrigley2010) and Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Smith, van Lieshout and Newton2017). Figure 4 shows the geographic distribution of import competition in 1910, with and without this control.

Figure 4. Geographic Distribution of Change in German Imports per Worker, 1885–1910

Election Data

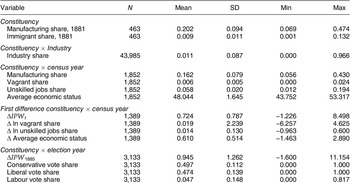

Our primary measure of the political effects of import competition is the share of the vote won by Conservative and Unionist parliamentary candidates. This variable captures the main left–right division in British politics over this period. The Labour Party only contested elections after 1900 and did so in an electoral pact with the Liberal Party. We use data from Eggers and Spirling (Reference Eggers and Spirling2014) and compute the share of the vote won by different parties in the eight general elections from 1885 to 1910. Constituency boundaries and the electoral franchise were consistent over this period. The franchise was also relatively broad: around two-thirds of adult men could vote. Exclusion was somewhat arbitrary, based primarily on residency criteria, leading one historian to conclude that “the overall occupational structure [of the franchise] does not differ vastly from what one would have expected from a fully inclusive franchise” (Brodie Reference Brodie2004, 52). Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the economic and political variables.

Table 1. Summary Statistics

Newspaper Measures of Local Concerns

We use data from the British Newspaper Archive to estimate the prevalence of different local concerns. The British Newspaper Archive is a project that seeks to digitize the British Library’s extensive historical newspaper collections. Over the 1885–1910 period, it contains text for 480 newspapers, which we geocode and link to parliamentary constituencies.Footnote 4 We compute the number of references to specific terms made in a given year by a given newspaper, divide by the number of issues of the newspaper in the British Newspaper Archive in that year, and then subtract the mean and divide by the standard deviation of that variable to aid interpretation. We use newspaper fixed effects in all specifications to control for time-invariant linguistic or topical features of specific newspapers.

Our intuition in using these measures is that if an issue became more prevalent in a given constituency in a given year, one would expect newspapers to devote greater attention to it. Although newspapers might reflect the opinions of their owners and editors rather than those of their readers, theoretical and empirical studies of media bias suggest that newspapers tend to cater to their readers’ views and concerns (Gentzkow and Shapiro Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2010). Incentives for newspapers to provide more representative opinion are stronger when demand for media and potential advertising revenues are high, so the returns to providing popular news that will appeal to readers is large (Petrova Reference Petrova2011). These theoretical predictions should apply during the period we study: by the 1880s the removal of newspaper taxes and developments in printing technology had made possible a business model for newspapers based on large circulations and advertising revenues (Lee Reference Lee1976).Footnote 5

Other Data

We additionally use an unpublished dataset of parliamentary candidates’ manifestos compiled by Laura Bronner and Daniel Ziblatt. From the late-nineteenth century onward, candidates could distribute one leaflet for free via Royal Mail to inform voters of their views. Bronner and Ziblatt collected and digitized manifestos for all parliamentary candidates in general elections from 1892 to 1910. We use these data in a way similar to that for the newspaper data. We divide the number of references to a given term by the number of words in the manifesto and then standardize that measure.Footnote 6

EMPIRICAL FRAMEWORK

Model Specification

Our estimation strategy examines the effects of within-constituency changes in imports per worker on a set of outcome variables: labor market distress, voting for particular parties, and the prevalence of different issues in newspapers and campaign manifestos. We use two main model specifications. For the economic outcome variables, using decadal data from the census, we estimate regressions of the form

where

![]() $ \Delta {Y}_{it} $

is the change in a given outcome variable in constituency i relative to the previous census,

$ \Delta {Y}_{it} $

is the change in a given outcome variable in constituency i relative to the previous census,

![]() $ \Delta {IPW}_{it} $

is the change in the trade shock measure relative to the previous census,

$ \Delta {IPW}_{it} $

is the change in the trade shock measure relative to the previous census,

![]() $ {\gamma}_t $

is a year fixed effect, and

$ {\gamma}_t $

is a year fixed effect, and

![]() $ {\mathbf{X}}_{it}^{\prime } $

is a vector of controls. We estimate these models in stacked first differences, consistent with other economic studies of the effects of trade shocks (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2013).

$ {\mathbf{X}}_{it}^{\prime } $

is a vector of controls. We estimate these models in stacked first differences, consistent with other economic studies of the effects of trade shocks (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2013).

We estimate the majority of regressions with political dependent variables in levels. This practice is consistent with empirical studies of the effects of trade shocks on voting (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018b; Reference Colantone and Stanig2018c; Feigenbaum and Hall Reference Feigenbaum and Hall2015). We are interested in the effects of long-term changes in import penetration, not the effects of year-to-year variation. This focus makes 10-year census-to-census first-differences appropriate, but election-to-election first-differences inappropriate, given the short gap between some elections in our sample.Footnote 7 We estimate regressions of the form

where

![]() $ {Y}_{it} $

is some political outcome variable,

$ {Y}_{it} $

is some political outcome variable,

![]() $ \Delta {\mathrm{IPW}}_{it} $

is the change in imports per worker for constituency i in year t relative to the start year,

$ \Delta {\mathrm{IPW}}_{it} $

is the change in imports per worker for constituency i in year t relative to the start year,

![]() $ {\mathbf{X}}_{it}^{\prime } $

is a vector of controls,

$ {\mathbf{X}}_{it}^{\prime } $

is a vector of controls,

![]() $ {\gamma}_t $

is a year fixed effect, and

$ {\gamma}_t $

is a year fixed effect, and

![]() $ {\delta}_i $

a constituency fixed effect. Note that the differenced dependent variables and constituency fixed effects account for time-invariant confounders.

$ {\delta}_i $

a constituency fixed effect. Note that the differenced dependent variables and constituency fixed effects account for time-invariant confounders.

Identification

Estimates from these regressions can be interpreted causally within the difference-in-differences framework. Although our measure of imports per worker is computed according to a shift-share formula, our identification strategy does not rely on the use of exogenous variation in the form of exports from Germany to a third party. Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift (Reference Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin and Swift2020) argue that shift-share designs rely on the assumption that the initial shares used to construct the shift-share variable are exogenous to the outcome variable. This assumption is more plausibly satisfied in research designs like ours, which control for unit fixed effects and for which the equivalent identifying assumption is that these shares are exogenous to changes in the outcome variables. Thus for our estimates to be interpreted causally, one must believe that, apart from the effects of changes in imports, constituencies with greater employment in affected industries would have followed trajectories similar to those of constituencies with less employment in those industries.

We address this assumption in three ways. First, we include controls for initial manufacturing interacted with year dummies across all our specifications. We thus allow more industrial constituencies to follow different nonlinear trajectories to less industrial constituencies and implicitly compare constituencies affected by German imports in a given year with less-affected industrial constituencies. Second, we follow the procedure outlined by Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift (Reference Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin and Swift2020) to identify the industry-year combinations for which our estimated coefficients are most sensitive to misspecification and show that our results are robust to controlling for these initial industry shares interacted with year dummies and to controlling for the first three principal components of the 1881 industry shares interacted with year dummies. These robustness checks suggest it is unlikely that differential trends relating to specific industries or clusters of industries are driving our results. Third, we employ traditional difference-in-differences robustness tests: controlling for constituency time trends and checking that leads of the trade shock variable do not affect outcomes.

The shift-share design is important to our empirical strategy as an accounting method and as a way to avoid bias from posttreatment economic changes. It is important to emphasize that our primary use of the Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2013) trade shock formula is simply to measure the incidence of import competition at the local level. Using the 1881 industry shares, as opposed to subsequent shares, has the additional benefit of separating our measure of exposure to German imports from changes in local economies that may themselves be affected by German imports.

Standard Errors

We cluster standard errors at the county level rather than at the more granular constituency level. This is a conservative choice to account for potential spatial autocorrelation in the error term due to local spillover effects. In the Extended Appendix, we reestimate all regressions in the article using the aggregation method recommended by Borusyak, Hull, and Jaravel (Reference Borusyak, Hull and Jaravel2022). Adão, Kolesár, and Morales (Reference Adão, Kolesár and Morales2019) note that in shift-share designs, conventional standard errors fail to account for correlation in the error structure between units with similar shares. Aggregating the relevant variables to the industry level gives “exposure robust” standard errors that account for errors correlated across units with similar shares in the same way that one can avoid problems with within-cluster correlations by aggregating to the level of the cluster.

ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF THE GERMAN TRADE SHOCK

We first examine the effects of German import competition on labor market disruption. Table 2 reports the results of stacked first-difference regressions in which the dependent variables are the log share of vagrants in a constituency and the log share of people employed in unskilled jobs. Import competition was associated with negative outcomes in local labor markets: the fraction of vagrants increased, as did the share of people employed in unskilled jobs. This evidence is consistent with a theoretical account in which German imports cause reductions in employment in import-affected industries, pushing workers either out of the labor force entirely—into the vagrants category—or into unskilled jobs. It also fits with arguments made by advocates for protectionism at the time. The Western Gazette complained that “the free importation of foreign manufactures … degrades skilled and highly-paid workers to the ranks of casual labour.”Footnote 8 Models (1) and (2) suggest that a 1-pound increase in imports per worker was associated with a 15% relative increase in vagrancy; models (5) and (6) suggest that such an increase was associated with a roughly 1.5% relative increase in the share of employment in unskilled jobs.Footnote 9 These results are robust to the inclusion of controls for 1881 manufacturing interacted with year dummies and to the addition of constituency-specific time trends, which make it more plausible that the parallel trends assumption holds. Additionally, in Appendix B we show that these results are robust to controlling for initial shares in primary industries interacted with year dummies and to controlling for the first three principal components of the matrix of 1881 industry shares, which account for 84% of the variance in those shares, interacted with year dummies.

Table 2. Effects of Import Competition on Local Economies

Note: Stacked first difference estimates, at the constituency level for 1880–1890, 1890–1900, and 1900–1910. All models include year fixed effects; models (2)–(4) and (6)–(8) add controls for lagged manufacturing employment, lagged fraction in unskilled jobs, lagged fraction of vagrants, and lagged average economic status; models (3) and (7) include 1881 manufacturing employment interacted with year dummy variables; and models (4) and (8) include constituency fixed effects, which adjust for constituency-specific time trends. Standard errors clustered by county in parentheses. Table F-1 of the Full Tables Appendix reports full output. *p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

POLITICAL RESPONSES TO THE GERMAN TRADE SHOCK

We now examine the effects of German import competition on political outcomes. We find that import competition reduced vote share for the Conservative Party and increased it for the Liberal and Labour parties, but only after 1900. Table 3 documents the main electoral effects, regressing the Conservative and Unionist share of the vote on

![]() $ \Delta \mathrm{IPW} $

over different periods. Although there was essentially no association between import competition and vote share for the Conservative Party over the entire 1885–1910 period (1 and 2), the association between these variables varied over the period. For 1885–1900, we find a positive correlation between imports per worker and Conservative vote share. Although the positive coefficient in model (3) could be taken as evidence that German imports increased vote share for the more protectionist party, we are wary of drawing strong conclusions from this result. Adding controls for initial manufacturing shares interacted with year dummies results in a smaller and statistically insignificant coefficient in model (4), suggesting that the effect in model (3) may be picking up changes in voting patterns in industrial areas unrelated to the trade shock. We find stronger evidence for a negative effect of the trade shock on Conservative vote share during the 1900–1910 period. In model (5), we find that a 1-pound increase in imports per worker was associated with a roughly 2-percentage-point decrease in Conservative vote share over this period. In 15% of constituency races from 1900–1910, the difference between the Conservative and Liberal or Labour vote share was smaller than this difference.

$ \Delta \mathrm{IPW} $

over different periods. Although there was essentially no association between import competition and vote share for the Conservative Party over the entire 1885–1910 period (1 and 2), the association between these variables varied over the period. For 1885–1900, we find a positive correlation between imports per worker and Conservative vote share. Although the positive coefficient in model (3) could be taken as evidence that German imports increased vote share for the more protectionist party, we are wary of drawing strong conclusions from this result. Adding controls for initial manufacturing shares interacted with year dummies results in a smaller and statistically insignificant coefficient in model (4), suggesting that the effect in model (3) may be picking up changes in voting patterns in industrial areas unrelated to the trade shock. We find stronger evidence for a negative effect of the trade shock on Conservative vote share during the 1900–1910 period. In model (5), we find that a 1-pound increase in imports per worker was associated with a roughly 2-percentage-point decrease in Conservative vote share over this period. In 15% of constituency races from 1900–1910, the difference between the Conservative and Liberal or Labour vote share was smaller than this difference.

Table 3. Effects of Import Competition on Voting

Note: Constituency-level fixed effects regression; dependent variable is share of the vote for the Conservative Party. All models include constituency and election fixed effects, and models (2), (4), (6), and (8) add manufacturing employment in 1881 interacted with election dummies. Models (7) and (8) use a panel matched on Conservative vote share in 1885, 1892, and 1900. Standard errors clustered by county in parentheses. Table F-2 of the Full Tables Appendix reports full output. *p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

We perform an extensive set of robustness checks. We find this effect is robust to the addition of manufacturing-by-year controls, and to the addition of time-varying controls for specific industries, and for the 1881 industry shares PCA (Table A-9). One might be concerned that the

![]() $ \Delta \mathrm{IPW} $

variable is correlated with demand or technology shocks common to both Britain and Germany. However, when we control for the change in exports per worker to Germany, our results are unaffected, suggesting that rising competition from Germany rather than shocks to both German and British supply and demand, which would affect both exports and imports, account for our results (Table A-13). Similarly, when we decompose the estimate by industry following Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift (Reference Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin and Swift2020) in Table A-8, we find that our results are not driven by new industries like chemicals and electricals, which saw rapid technological progress during this period. In these industries, German firms did have an advantage, but the initial base of employment was small, so the labor-market and political effects were muted. Another concern is that the German trade shock was correlated with a different import shock: US grain imports (Heblich, Redding, and Zylberberg Reference Heblich, Redding and Zylberberg2021; O’Rourke Reference O’Rourke1997). We compute a measure of US wheat imports per worker and reassuringly find that controlling for this variable does not affect our estimates (Table A-13). Our results are also robust to dropping individual elections from the 1900–1910 period (A-10), suggesting no single election accounts for our results. Estimating the models in long first differences gives very similar point estimates and levels of significance (A-7). Using the estimator proposed by de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille (Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2020), which is robust to the negative weights issue in two-way fixed effects estimation, gives results that are greater in magnitude and statistically significant (Table A-15). Table A-6 switches the dependent variable from Conservative vote share to combined Liberal and Labour vote share and confirms the pattern of results.

$ \Delta \mathrm{IPW} $

variable is correlated with demand or technology shocks common to both Britain and Germany. However, when we control for the change in exports per worker to Germany, our results are unaffected, suggesting that rising competition from Germany rather than shocks to both German and British supply and demand, which would affect both exports and imports, account for our results (Table A-13). Similarly, when we decompose the estimate by industry following Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift (Reference Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin and Swift2020) in Table A-8, we find that our results are not driven by new industries like chemicals and electricals, which saw rapid technological progress during this period. In these industries, German firms did have an advantage, but the initial base of employment was small, so the labor-market and political effects were muted. Another concern is that the German trade shock was correlated with a different import shock: US grain imports (Heblich, Redding, and Zylberberg Reference Heblich, Redding and Zylberberg2021; O’Rourke Reference O’Rourke1997). We compute a measure of US wheat imports per worker and reassuringly find that controlling for this variable does not affect our estimates (Table A-13). Our results are also robust to dropping individual elections from the 1900–1910 period (A-10), suggesting no single election accounts for our results. Estimating the models in long first differences gives very similar point estimates and levels of significance (A-7). Using the estimator proposed by de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille (Reference de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille2020), which is robust to the negative weights issue in two-way fixed effects estimation, gives results that are greater in magnitude and statistically significant (Table A-15). Table A-6 switches the dependent variable from Conservative vote share to combined Liberal and Labour vote share and confirms the pattern of results.

Our empirical strategy also reduces the possibility that other explanations for the rise of the early welfare state explain our results. Franchise extension shifting the median voter left, as argued by Lindert (Reference Lindert2004), is unlikely to explain why the constituencies affected by German imports shifted toward the Liberals. The franchise was restricted by property ownership and residency, so economic changes that pushed people out of work and into vagrancy would have served to restrict access to the vote. There was gradual franchise extension during this period due to inflation and economic growth pushing people over the property threshold, but this was a slow-moving and common phenomenon and should be accounted for by constituency and year fixed effects and manufacturing-by-year controls. It is unlikely that trade unions are driving our results. In Table A-11, we address this possibility using data on unionization by county. Controlling for unionization interacted with period dummy variables attenuates our coefficients somewhat, but does not change their substantive or statistical interpretation. Explanations centered on class politics do a poor job of explaining our results given that the Liberals—not an explicitly working-class party—were the prime beneficiaries and implemented the welfare reforms in government. It is similarly difficult to believe that our results are explained by employers mobilizing in support of the welfare state, for reasons unrelated to trade. One would have to believe that constituencies affected more by the trade shock were also following differential trends in employer mobilization that were distinct from initial levels of industrialization. Last, other theories of welfare state formation based on industrialization are unlikely to drive our results. Import competition harmed British manufacturing industries, so changes in our independent variable should be negatively correlated with increases in industrialization within Britain. We also control for nonlinear time trends related to initial industrialization, which should account for most of the variation in industrialization unrelated to the trade shock during the period.

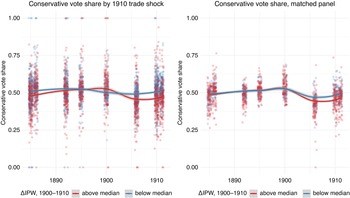

Our results suggest that the trade shock increased the share of the vote for left-of-center parties during the 1900–1910 period but was associated with a mild shift away from those parties during the preceding period. These differential trends may suggest that our estimates for the 1900–1910 period constitute a lower bound: if certain constituencies were trending toward the Conservatives from 1885 to 1900 and then reversed direction, the effect of the trade shock relative to a continued trend toward the Conservatives would be larger than the effect we estimate. However, a plausible concern is that our estimates for 1900–1910 reflect some form of mean reversion after an outsized shift to the Conservatives. As an additional robustness check, we use matching to create a panel of constituencies following a similar trend in Conservative voting from 1885 to 1900. We divide constituencies into two groups according to the incidence of the 1900–1910 trade shock and then match on 1885, 1892, and 1900 Conservative vote share. We discard pairs that differ by more than 0.1 standard deviation in 1900 Conservative vote share and apply a looser cutoff to the 1885 and 1892 vote shares. The idea is not to use matching to provide causal inferences within a selection-on-observables framework but rather to create a panel that more plausibly satisfies the parallel trends assumption. Replicating the 1900–1910 difference-in-differences regressions of Conservative vote share on import competition in Table 3, models (7) and (8), we find a slightly smaller but comparable and statistically significant effect of –1.8 percentage points. Figure 5 illustrates this strategy, comparing the average Conservative vote shares over time between constituencies more and less affected by the 1900–1910 trade shock: although the matched constituencies follow the same trajectory prior to 1900, they subsequently diverge, and Conservative support falls more sharply in constituencies badly affected by the trade shock.Footnote 10

Figure 5. Conservative Vote Share by 1910

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\Delta} \mathbf{IPW} $

, with Matched Panel

$ \boldsymbol{\Delta} \mathbf{IPW} $

, with Matched Panel

Although this matching process, analogous to a synthetic control design, is our preferred specification for adjusting for possibly nonparallel trends, we report additional difference-in-differences robustness checks in Table A-14. We directly control for constituency trends in Conservative voting and perform placebo tests in which we regress pre-1895 voting outcomes on subsequent import penetration.

INTERPRETATION

The German trade shock increased support for left-of-center parties through two mechanisms. First, the negative economic effects of import penetration directly led to demand for the early welfare state. Unemployed voters demanded compensation, and voters concerned about an increased risk of unemployment supported programs that would hedge against these risks. We find that the trade shock led Liberal candidates to place more emphasis on issues related to social reform. Second, the trade shock changed attitudes toward the unemployed, and this development affected support for welfare policies. The concept of unemployment as the result of macroeconomic fluctuations as opposed to personal moral deficiencies emerged in this period. Politicians and voters may have believed that people unemployed due to foreign import competition were worthy of compensation in a way that vagrants and paupers were not. We find that the trade shock was associated with a change in newspaper language relative to terms associated with this new concept of unemployment.

Voter Concern about German Trade

Before directly studying these mechanisms, we examine whether the trade shock increased attention to trade in newspapers. A theory in which the direct economic effects alone accounted for the political changes—unemployed voters supported the welfare state—would not require voters to necessarily pay more attention to trade. However, increased attention to trade is an important part of mechanisms in which trade affected beliefs about the risk of economic upheaval—perhaps by tapping into fears about national decline and global competition—and the moral desert of the unemployed, perhaps because foreign industrialization is unrelated to the effort of domestic workers. We regress a standardized measure of the per-issue references to different trade-related terms on

![]() $ \Delta \mathrm{IPW} $

, with newspaper and year fixed effects and time-varying manufacturing controls. Table 4 shows the results of these regressions. Over the whole period, import competition was associated with increased references in newspapers to trade and imports. The coefficient magnitudes suggest that a 1-pound increase in imports per worker was associated with a 0.1-standard-deviation increase in coverage. The effect is driven by the 1900–1910 period—models (3), (4), (7), and (8)—when we find trade had a political effect.

$ \Delta \mathrm{IPW} $

, with newspaper and year fixed effects and time-varying manufacturing controls. Table 4 shows the results of these regressions. Over the whole period, import competition was associated with increased references in newspapers to trade and imports. The coefficient magnitudes suggest that a 1-pound increase in imports per worker was associated with a 0.1-standard-deviation increase in coverage. The effect is driven by the 1900–1910 period—models (3), (4), (7), and (8)—when we find trade had a political effect.

Table 4. Effects of Import Competition on Newspaper References to Trade

Note: Newspaper-level regressions. Dependent variable is number of uses of specified term per newspaper issue, standardized. All models include newspaper and year fixed effects. For newspapers in cities, ΔIPW is calculated at the city-level, not the constituency-level. Standard errors clustered by county in parentheses. Table F-3 of the Full Tables Appendix reports full output. *p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Support for the Neo-Welfare State

At the constituency level, the contents of parliamentary candidates’ appeals provide evidence that import competition led to increased demand for the neo-welfare state. We expect that candidates could observe some signal of local demand for particular policies and would emphasize policies that were more popular with voters in their constituencies. If candidates emphasized a policy more in a given area, it was presumably in part because that policy was more popular there. We regress a normalized measure of references to specific policy-related terms in Liberal manifestos on

![]() $ \Delta \mathrm{IPW} $

. We focus on three terms, “social reform,” which was used to refer broadly to social policy, “poor law,” the punitive system of welfare that Liberal governments in the 1900s promised to reform, and “labour exchange,” a proposed policy to deal with unemployment due to economic fluctuations. These policies sought to address hardships endured by adult unemployed workers, those affected by import competition. Table 5 shows a consistent positive association between import competition and Liberal candidates mentioning these phrases.

$ \Delta \mathrm{IPW} $

. We focus on three terms, “social reform,” which was used to refer broadly to social policy, “poor law,” the punitive system of welfare that Liberal governments in the 1900s promised to reform, and “labour exchange,” a proposed policy to deal with unemployment due to economic fluctuations. These policies sought to address hardships endured by adult unemployed workers, those affected by import competition. Table 5 shows a consistent positive association between import competition and Liberal candidates mentioning these phrases.

Table 5. Effect of Local Trade Shocks on References to Social Reform in Liberal Campaign Manifestos

Note: Manifesto-level regressions. Dependent variable is number of uses of specified term relative to total length of manifesto, by Liberal candidates, standardized. All models include constituency and election fixed effects. Standard errors clustered by county in parentheses. Table F-4 of the Full Tables Appendix reports full output. *p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Qualitative newspaper evidence suggests in addition that voters understood that voting Liberal meant voting for the welfare state. Conservative campaigners in January 1910 argued that unemployment “was ‘the’ issue” in the election.Footnote 11 Responding to this Conservative challenge, the Liberal chancellor Lloyd George argued that the Liberals’ proposed budget “makes a larger provision for mitigating the evils of unemployment than any measure ever introduced,” drawing emphasis in particular to labor exchanges and unemployment insurance.Footnote 12

There is also evidence from historians and primary sources that import competition led Liberal politicians to prioritize welfare state reforms. Green (Reference Green1995, 230) notes that economic dislocation lent credence to Conservative promises of tariff reform, which promised to “deal with the causes as well as the symptoms of social distress.” Searle (Reference Searle1992) argues that the Liberal party adopted an expanded policy of social reform in response to this electoral threat. In 1910, the Labour MP Philip Snowden argued that supporters of Free Trade had to promote “social reforms which will so improve the conditions of the working classes that they will not be victims of the sophistries and plausibilities of Tariff ‘Reform.’”Footnote 13

Changing Attitudes toward the Unemployed

The results presented thus far—that German import competition induced a shift toward the Lib-Lab pact proposing the early welfare state—could be explained by a direct compensation effect (Rodrik Reference Rodrik1998). We also find evidence consistent with a different mechanism in which trade-induced economic turmoil, because it was unrelated to the behavior of those affected, changed beliefs about the moral desert of the unemployed. A new concept of unemployment emerged in this period, and we find evidence that its emergence was linked to the incidence of the trade shock. We also see this concept of unfair misfortune linked to economic fluctuations in Liberal campaign rhetoric.

There is qualitative evidence that a shift in attitudes toward unemployment occurred in early twentieth-century Britain. Beveridge (Reference Beveridge1910), later the architect of the welfare state, argued that unemployment, “the problem of the adjustment of the supply of labour and the demand for labour” (4), was the product of technical change, “fluctuations of industrial activity” (13), and the need for excess labor for industries to hire in boom periods. While acknowledging that the least productive workers may be more likely to be unemployed, Beveridge noted that “The best and most regular of workmen may in a changing world find himself exceptionally unemployed” (142). The prevalence of unemployment was thus distinct from the moral character of the unemployed. The concept of “unemployment” as distinct from vagrancy entered common usage at this time. This sharp break can be seen in Figure 6, which plots references to “unemployment,” “vagrancy,” and “pauperism” in the Times newspaper over the period.

Figure 6. References to Unemployment, Vagrancy, and Pauperism in the Times

This attitudinal shift was linked to the incidence of the trade shock. Table 6 examines the link between import competition and the use of terms related to this new concept of unemployment in newspapers. It shows the results of newspaper-level regressions in which the dependent variable is the number of references to “unemployment,” “employment,” and the “unemployed,” minus the number of references to “pauper(s),” “pauperism,” “vagrant(s),” and “vagrancy,” standardized. Positive coefficients across specifications suggest that coverage of the economic effects of the trade shock focused on the morally neutral phenomenon of unemployment, not morally charged notions of vagrancy and pauperism. In Appendix D, we employ a more principled approach and use natural language processing methods to identify terms more associated with the new concept of unemployment relative to older notions of pauperism. We find a similar effect of import competition on newspaper usage of terms connected to this new concept of unemployment in Table A-17.Footnote 14

Table 6. Effects of Import Competition on Newspaper References to Unemployment, Vagrancy, and Pauperism

Note: Newspaper-level regressions. Dependent variable is the number of references to “unemployed,” “unemployment,” and “employment,” minus the number of references to “vagrants,” “vagrancy,” “pauper,” and “pauperism,” standardized. All models include newspaper and year fixed effects. For newspapers in cities,

![]() $ \Delta $

IPW is calculated at the city-level, not the constituency level. Standard errors clustered by county in parentheses. Table F-5 of the Full Tables Appendix reports full output. *p < 0.10, **

p < 0.05, ***

p < 0.01.

$ \Delta $

IPW is calculated at the city-level, not the constituency level. Standard errors clustered by county in parentheses. Table F-5 of the Full Tables Appendix reports full output. *p < 0.10, **

p < 0.05, ***

p < 0.01.

The new concept of unemployment featured in Liberal arguments for the early welfare state. Campaigning in 1910, Lloyd George claimed, “Unemployment entails great suffering on the part of people who do not deserve it… They are not responsible for the fluctuations in trade. They are purely its victims, and I think that it is a duty of any country within the limits of its resources to see that that suffering is mitigated.”Footnote 15 The idea that economic volatility meant that people out of work were not responsible for their misfortune was thus part of the argument used to convince voters to support the neo-welfare state.

Alternative Theories of the Effects of Import Competition

Existing research highlights an alternative set of political effects of trade exposure. Scholarship on the China trade shock finds that voters who are negatively affected by increased trade want less trade and turn to protectionist candidates and parties (Che et al. Reference Che, Lu, Pierce, Schott and Tao2016), punish incumbent politicians (Jensen, Quinn, and Weymouth Reference Jensen, Quinn and Weymouth2017), and experience a shift in values toward authoritarianism and xenophobia (see for instance Ballard-Rosa et al. Reference Ballard-Rosa, Malik, Rickard and Scheve2021). A shift toward protectionism cannot explain our results, as the Liberals remained committed to free trade, whereas the Conservatives, who were perceived to be more supportive of tariffs, partially embraced protectionism in 1906 and doubled down on that policy in the 1910 elections. We similarly find no evidence that German imports prompted voters to punish incumbent politicians whether we define incumbency at the individual, party-constituency, or national level (Table A-16).

We do find evidence of increased attention to immigration in both newspapers and the election addresses of Conservative candidates. Anti-immigrant politics could be the manifestation of in-group favoritism and xenophobia caused by import competition, as suggested by scholarship on the China trade shock, or it could reflect voters’ changed economic priorities. Protectionism and immigration restriction can be substitutes: restricting the supply of foreign workers who would compete in the labor market offers politicians a different way of limiting the harm to workers affected by rising imports (Peters Reference Peters2017).

In the 1900s, the British government began to regulate immigration. The Conservative government in 1905 introduced the Aliens Act, which defined categories of undesirable immigrants and gave the state power to exclude them. The act mainly excluded Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. In Table A-20, we report a positive effect of import competition on Conservative candidates referring to immigrants, aliens, and Jews. Import competition may have created demand for xenophobic policies, which Conservative candidates sought to capitalize on. We also find a positive effect on coverage of immigration in newspapers (Table A-21).

The net effect of anti-immigrant politics on electoral outcomes during this period is of secondary importance relative to the rise of the welfare state. The Aliens Act was a policy that Conservative MPs campaigned for and a Conservative government implemented, so an increase in anti-immigrant politics cannot explain the shift toward the Liberals. We leave a study of when trade-induced xenophobia is electorally dominant, which would require more than one case study, for future research. A possible explanation for why the electoral effects of xenophobia in early twentieth-century Britain were relatively muted is that the scale of immigration, although historically unprecedented, was relatively small and immigrants were concentrated in a handful of parliamentary constituencies in east London (Pelling Reference Pelling1967).

CONCLUSION

We examine the economic and political effects of rising German imports in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain. We find that the German trade shock increased the prevalence of vagrancy and employment in low-skilled occupations during the full study period of 1880 to 1910 and decreased electoral support for the Conservative Party after 1900. We note that the timing of when exposure to increasing imports had a differential effect on voting patterns coincides with when the Liberal Party started to advocate social reforms and investment in Britain’s neo-welfare state. We provide evidence that trade shocks were correlated with Liberal candidate manifesto mentions of social reform, bolstering our interpretation that the left-of-center shift in trade-affected constituencies reflects increased demand for social welfare spending. Our results suggest this compensation mechanism was driven by two considerations: the German trade shock increased assessments of how volatile employment is in a market economy and therefore how much social insurance is optimal, and it changed beliefs about the deservingness of the poor, transforming vagrants into the unemployed, which in turn increased support for welfare state development.

These results suggest an important and underappreciated role for globalization in the creation of the welfare state. They also resonate with a large literature on compensation theory including Cameron (Reference Cameron1978) and Rodrik (Reference Rodrik1998). It is notable that some of the more recent research on the political consequences of China’s integration with the world economy also shows political responses that are left of center (Che et al. Reference Che, Lu, Pierce, Schott and Tao2016). But a great deal of this research records a response to trade that is more protectionist, skeptical of government’s role in the economy, xenophobic, and supportive of nationalist and populist parties and candidates (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018b; Reference Colantone and Stanig2018c; Hays, Lim, and Spoon Reference Hays, Lim and Spoon2019; Margalit Reference Margalit2019; Milner Reference Milner2021).

What makes Britain during this period different? What more generally accounts for variation across individuals, regions, countries, and periods in the political effects of openness? There are at least four important characteristics of British politics during the first decade of the twentieth century that contrast to the political economy setting of twenty-first-century advanced industrial democracies and may have contributed to the turn to the welfare state and social reform.

First, progressive reforms in the twentieth century promised to have a relatively significant marginal effect because they were added to a minimal state and promised to ameliorate some of the worst aspects of laissez-faire capitalism. Second, the twenty-first-century context was one in which the state was perceived to have failed to set policies that ensured that the gains from globalization were widely shared, whereas at the turn of the twentieth century the idea that the state was responsible for such outcomes was just beginning to take hold. It may be more compelling to consider a new role for the state than to invest further in a state that had failed. Third, differences in income levels during the two periods may have influenced the weight of labor market costs and consumer benefits associated with increased trade. Free trade in early twentieth-century Britain was first and foremost associated with cheaper food prices, which was central to Liberal Party arguments against protectionism and in favor of social reform to deal with labor market dislocation. Although consumer considerations are certainly relevant in the modern context and have been shown to be important in attitudes about trade in the developing world (Baker Reference Baker2003), it is not clear that they have the same political resonance in contemporary debates in developed democracies. Finally, it is possible that variation in ethnic and racial heterogeneity or the extent of immigration influences the likelihood that individuals blame out-groups for changes in their economic trajectories or embrace nationalist and populist solutions. For example, the foreign-born population as a percentage of the total in England and Wales is nearly an order of magnitude higher now than at the end of the nineteenth century. Future research is needed to construct a full account of differing political responses to openness. Our study provides a roadmap for such research.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000673.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8SIOKU.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers at the APSR, Andrew Blinkinsop, Manuel Bosancianu, Rafaela Dancygier, Ed Mansfield, Nita Rudra, Christina Toenshoff, and Rob Van Houweling. We are also grateful to the panelists at the 2021 APSA Annual Meeting, Bocconi University, GRIPE, IE School of Global and Public Affairs, King’s College London, University of California Berkeley, and the University of Pennsylvania for useful feedback on the manuscript. We would like to thank Laura Bronner and Daniel Ziblatt for generously sharing their manifesto data and Joseph Day and Karen Jusko for sharing crosswalk files.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.